ABSTRACT

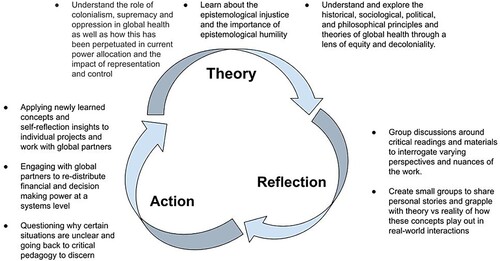

Colonial history has deeply influenced the structures that govern global health. Though many curricula promote equity, few focus on developing competency in understanding and dismantling colonialism, and the structural barriers to global health equity. To dismantle colonial structures and create equitable collaborations, learners must be able to recognise how colonialism permeates global health practice. We propose a praxis cycle in education that asks learners to actively engage with these concepts. The praxis cycle includes: Theory: Learners explore the principles of decoloniality to understand how attitudes and practices are shaped by biased social structures influenced by colonialism. Reflection: Learners reflect on their work in LMIC settings through a lens of decoloniality and positionality. Action: Learners work in LMIC settings where they apply and actively engage with these concepts and insights. During implementation of this curriculum, we encountered several challenges including the cognitive dissonance of the learner to changing mental models of global health practice, existing systemic barriers to changing one’s practice and the development of accountability mechanisms for learners in this type of curriculum. Intentionally incorporating a praxis cycle helps learners recognise their role in disrupting the structural forces that promote inequities, and actively dismantle the forces upholding systemic oppression.

Introduction

Though global health has a well-known colonial history, it has simultaneously been revered as being an evolved field that ‘transcends national boundaries’ (Beaglehole & Bonita, Citation2010). This view fails to recognise the inequities perpetuated by present-day power dynamics due to its foundations within colonial structures. Indeed, the current structures and practice of global health are deeply influenced by the history of colonialism, defined as ‘the practice of extending and maintaining a nation's political and economic control over another people or area’ (Kohn, Citation2017). This has been a significant factor in the development of the profession of global health, which as a field frequently centres on the education of learners in the Global North (Daffé et al., Citation2021) rather than the needs identified by the Global South. In the absence of education to identify and recognise the influence of colonialism, oppression and supremacy in global health, well-intentioned current and future global health practitioners may unknowingly perpetuate inequities and unbalanced power structures in global systems.

Interest in global health has risen dramatically among health care professionals in high-income countries. In the United States, up to 30% of medical students engaged in global health experiences and about 60% of those students expressed interest in a career in global health (Cox et al., Citation2017). In response, global health fellowships in medical and nursing specialties have risen – resulting in a new focus on professional standards for practitioners of global health (Ahn et al., Citation2015). Competencies have been developed to guide global health practitioner education (Astle et al., Citation2018; Sawleshwarkar & Negin, Citation2017; Schleiff et al., Citation2020). Though many existing curricula include concepts such as social justice, equity and human rights, there has been minimal pedagogy (equalhealth.org, Citation2022; University of California-San Francisco (UCSF), Citation2022) designed to incorporate an interrogation of the colonial structures on which global health is based, and even less around the tangible skills required to dismantle systemic colonial practices and promote equity. Most global health education remains firmly rooted in colonial structures and conceptualisation.

Similar to other learned skills, promoting global health equity cannot be done through theoretical teaching alone, but must be scrutinised, practiced and reflected on by the learner in order to achieve competency. This concept is at the core of the praxis cycle (Freire, Citation1970). Indeed, in order to achieve true transformation, individuals must not only engage in dialogue, but act on their environments while critically reflecting on their actions and the impacts of such actions (Freire, Citation1970).

A critical step in dismantling the oppressive, colonial and racist structures which govern and fund global health is to educate current trainees who will participate in the future practice of global health. We created a curriculum for global health fellows titled Decoloniality and Global Health Equity (DGHE). The curriculum is intended to create an educational foundation that provides learners with the tools necessary to continue moving through a praxis cycle of theory, reflection, and action (Tinker Sachs, Citation2014) throughout their career. Through this cycle, learners contemplate their role in global health and colonial frameworks, and embark on a lifelong pursuit of equitable global health practices. In our review of the current literature, we found no global health curricula that incorporate an active lens on decoloniality and global health equity, and we know of only a handful in development but not yet published (American Academy of Pediatrics, Citation2022).

Our objective in this article is to discuss our experiences and challenges of incorporating a praxis cycle of decolonial global health practice into a global health curriculum.

Educational approach

Theories and terms in decolonial literature

Our notion of the praxis cycle builds on the shoulders of many who have come before us in this work (Howard, Citation2003; Luitel & Dahal, Citation2020; Wilson, Citation2022). The concept of a praxis cycle was described first by Paulo Freire noting that dialogue is not enough for change, but rather that action and critical reflection are necessary for true social change (Freire Institute, Citation2022). Our approach is focused on decoloniality as defined by Anibel Quijano which is a perspective, stance and analysis that is ‘actional’. Decoloniality emphasises the active dismantling of the remnants of colonial power which still exist in global health. It is this spirit of translating theory into practice that we aim to instill in learners (Trembath, Citationn.d.). It is important that the focus on equity in global health not fall into the all-too-common trap of giving lip service to equity while remaining ‘fundamentally racist’ and maintaining the status quo (Mishra, Citation2021).

The evidence of colonialism in global health persists today. This is demonstrated in global aid provision which is often donor driven rather than locally driven, many major journals and institutes of training are in high-income countries (HICs) and many major health campaigns and funding streams for HIV, TB and malaria are developed by HICs (Kwete et al., Citation2022). To engage in structural competency in the global health sphere, learners must be able to name the structures and power imbalances that influence the way global health is practiced, the questions generated, the research conducted, the methods valued, and the programmes funded. We must imbue learners with the knowledge, vision, and skills to effect and advocate for structural change in all aspects of global health from individual interactions to underlying structures. The first step in this process is for learners to understand their positionality in various contexts. M. Duarte defined positionality in research as identifying one’s ‘own degrees of privilege through factors of race, class, educational attainment, income, ability, gender, and citizenship, among others for the purpose of analysing and acting from one’s social position ‘in an unjust world’ (CTLT Indigenous Initiatives, Citationn.d.). This definition can be applied to educational endeavours as well.

Understanding one’s own positionality helps to underscore more thoughtful and effective relationship building and social connection with colleagues in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), a step that is critical to developing a foundation for long-term structural change. It is well known that connection on an individual level creates the foundation for authentic and collegial relationships between institutions and organisations, thereby laying the groundwork for collective impact (Milligan et al., Citation2022). While the individual relationship is not sufficient for structural change, it is a necessary component as modelled by the biopsychosocial framework of health (Kusnanto et al., Citation2018). Structural change begins with the incorporation of the interpersonal, with progression to institutional and organisational change, progressing further to community change and ultimately to a structural and policy level (Milligan et al., Citation2022). If the ultimate aim is structural change through decoloniality, this can feel daunting to new learners. Thus, it is important for learners to begin with intentional development of individual relationships and build towards structural change as their training progresses.

Simply naming one’s position of privilege is not enough for structural change and decoloniality in global health. As has been noted, ‘identity is not solidarity’ (Conatz, Citation2012). Once learners identify their individual role and their institution’s role in a system, they must move beyond mere identification and make active changes in their practices to dismantle the colonial structures and systems they have identified. Harvey, et. al. describes the concept of structural competency within global health education as critical to a pedagogy focused on decoloniality within existing educational frameworks. This idea extends beyond the cultural sensitivity so often taught in global health, and challenges the learner to consider the structural barriers that inhibit equity in global health delivery including the political economy, financial systems and operational systems that drive inequities (Harvey et al., Citation2022). Five main categories of competency have been described to address structural education in practice. These categories include: (1) the ways structural inequalities are naturalised within the field of global health, (2) the impact of these structures on global health practice, (3) the role of social structures in producing and maintaining health inequities, (4) recognition of structural interventions to address these inequities and (5) the application of structural humility (Harvey et al., Citation2022; Metzl & Hansen, Citation2014).

The decoloniality for global health equity (DHGE) curriculum

Building on the structural competency categories defined by Harvey, et al, and Freire’s concept of praxis, we developed a curriculum for learners to understand and actively dismantle structural barriers to global health equity. Within our curriculum, there are 5 domains of global health where these principles are taught: (1) Principles of Health Equity (2) Global Health Education (3) Global Health Research (4) Advocacy and (5) Programme implementation. While the details and impact of this curriculum will be published separately, a brief description is necessary to understand our use of praxis in decoloniality.

Sessions include a didactic portion followed by a focused discussion intended to allow space for learners to grapple with the material in each domain in the context of their real-world experiences. All of our learners spend time doing global or rural health work during the course of the year. During this time, fellows are expected to apply knowledge from the curriculum to their daily work and interactions.

The curriculum is intended for fellow-level learners who have identified global health as a career. The curriculum spans 24 months and consists of monthly 3-hour sessions held in hybrid zoom/in-person sessions to allow participants on away rotations to still participate. Curriculum participants have come came from a variety of specialties and training programmes including: Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Pediatric Infectious Disease, Child Neurology, Neonatal Intensive Care, Pediatric Intensive Care, and Global Health General Paediatrics Fellowship, and Global Health Nursing Fellowship, and Internal Medicine Rural Health Fellowship.

Through multiple iterations of our curriculum, we have found that a commitment to attending at least 50% of sessions is critical to protecting safe group dynamics during conversations and to ensuring that topics and conversations can build on themselves, allowing for learner growth.

Decolonial praxis cycle

A global health curriculum focused on decoloniality should aim to teach learners to recognise and critique the structures at play that are functionally invisible or viewed as justifiable, and then implement the skills they learn to prevent the perpetuation of these structures in their ongoing work. As they progress, learners should develop skills to re-design institutions and systems based in decolonial practice.

To achieve this goal, we propose a decoloniality praxis cycle (as outlined in ) which asks learners to actively engage with these concepts by: understanding the theory of decoloniality in global health and the historical impacts of colonialism on current practice, reflecting on the structures in place and their position within these structures, and acting through implementation in their work and individual exploration of how their new knowledge and insights influence their work. Once they have spent time actively engaging in their work, learners reflect on their experience, reassess their actions and experiences, and go back to theoretical constructs to understand gaps in their knowledge to continue as a cycle in perpetuity.

Theory:

The focus of this phase is to expose learners to the history of colonialism and examples of how coloniality persists in global health. The curriculum postulates the idea that the attitudes and knowledge on which global health is based are shaped by biased social structures, such as language, economic, judicial, and educational systems that ‘produce and maintain inequalities and health disparities’ (Stonington et al., Citation2018). Learners explore interdisciplinary concepts, including sociological, historical, political and philosophical principles of equity and decoloniality and how they relate to the systems in which they work(Lucero, Citation2011). Topics are defined by the curriculum objectives and range from broad concepts such as the concept of decoloniality which include readings from modern decoloniality scholars such as Madhukar Pai and Seye Abimbola and nuanced topics such as liberation theology and spiritual healing, through the works of Dorothe Kienhues and colleagues (Khan et al., Citation2022; Kienhues & Bromme, Citation2012). Other readings explore specific topics such as the documented inequity in authorship in research collaborations between colleagues from the Global North and the Global South, the ethics of learners from HICs going to LMICs for clinical rotations, and project development and implementation through bi-directional collaboration (Crane, Citation2010; Fisher, Citation2022; Qato, Citation2022). Learners engage with various texts including Decolonizing Methodology by Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Citation2021) and academic journal articles outlining the implementation of decolonising research as written by Keikelame and Swartz (Citation2019). In addition to texts, learners engage with videos and materials that provide diverse types of knowledge, purposefully not limited to the traditional Western- knowledge base around global health teachings (Pine, Citation2013). The material centres context-derived solutions devoted to understanding clinical care, policy development and capacity building in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).

One key aspect in understanding the continued impacts of coloniality in global health is an exploration of epistemological injustice, or the inequity between knowledge conceived from Western traditions versus those from non-Western traditions; the ‘ways of knowing’ (Naidu, Citation2021). That is, students must be able to understand that the current teachings in global health, written and developed in the Global North, often result in favouring the perspectives from high-income countries (HICs) while devaluing local or Indigenous frameworks (Naidu, Citation2021). As a result, many of those in the Global South may feel obliged to adhere to a particular model of health to receive funding and acceptance into global institutions by the Global North (Naidu, Citation2021). This concept is central to understanding the root causes that prevent the realisation of decoloniality, as defined by Quijano above, at a structural level.

2. Reflection

In this phase, learners consider the proposed theories through iterative self-reflection and consideration of different perspectives and experiences. Learners are asked to reflect on their personal and professional positionality working in LMIC settings through this lens.

We employ small group discussions at each session to foster this reflection. Through a policy of consistent attendance and active engagement from all participants and facilitators, we create an environment of inclusion and shared discovery around the nuanced elements of implementation in each person’s global health work. Discussion is based on each learner’s reflection on how the specific topic relates to their work and areas for individual growth and improvement. Early in the course, we ask learners to identify their own areas of privilege and how this may differ depending on the context. This provides a foundation for learners to begin considering power dynamics, starting at an individual level and extending later into more systems-based programming. Drawing from several of Freire’s pedagogical works, we ask learners to reflect on these concepts and experiences in group dialogues to create new knowledge and challenge the boundaries of previous blind spots (Freire Institute, Citation2022). These discussions allow learners to hear other perspectives on academic theories and concepts, consider how they might apply them in their own work, and reflect on where they may have made mistakes previously.

The focus of this phase is to share personal experiences and grapple with challenging paradigms. To do this we build further on the biopsychosocial framework and utilise the social-ecological model to frame these experiences (Centers for Disease Control, Citation2022). In each session, they are asked to consider indicators they might use to measure decoloniality in their work, how to incorporate a colleague or community’s experience into their work and how to ensure impact at all levels of the socio-ecological model (i.e. Individual, Community, Systems, Structures, Policies). For instance, students may consider a community-based malnutrition programme. They learn about how historical and current oppressive economic practices affect the political and economic ecology of that country’s health, agriculture and other systems, leading to populations with inadequate access to food and healthcare. Poor nutrition can have compounding effects on a family and community at all levels with generational impacts. Students then discuss the challenges around developing an adequate nutrition programme to address malnutrition in a community. They discuss specific ways they are able to act in order to overcome these barriers to programming at a structural level.

Students may reflect on differences in power based on their own intersectional identities and grapple with which identities may provide privilege and which may be marginalising in different contexts. They then consider how specific individual actions may affect institutions or organisations. For example, to effect true structural change in a programme or institution, which voices are missing or marginalised? This aspect of the praxis cycle, where individual actions are interrogated, is necessary to progress to understanding structural decoloniality. We utilise the social-ecological model described above as part of our framework to develop structural competency within learners. For instance, if a learner is part of a specific collaboration and notes that a colleague’s voice is being marginalised and is able to bring that colleague’s voice into the work, this voice can open up a whole new set of ideas and participants to a work and project.

3. Action:

In this phase, learners apply the concepts and insights with which they have engaged to their collaborations with global partners in clinical care, projects or research in LMICs as well as advocacy around structural changes to promote decoloniality. Learners with less exposure to these concepts will likely begin applying learned concepts at the individual level to their own practices, projects and interactions with global partners. Over time, learners will begin to expand their application of decoloniality and equity to structural advocacy (active engagement and activism for structural change) by engaging with global partners to re-distribute financial and decision-making power and to dismantle structures in place that perpetuate inequities. Similar to a ‘Plan-Do-Study-Act’ cycle in the field of Quality Improvement (Taylor et al., Citation2014), learners then cycle back to the critical pedagogy to continue to discover how their own actions may be perpetuating inequities, and how to address these power imbalances both individually and structurally.

Learners use the knowledge they have gained studying and reflecting on theories around these concepts and directly implement them in their work. For instance, a learner may discuss the budget for a project on which they are collaborating. Western salaries are often higher than those in LMICs and thus there may be some inherent conflict in designing this budget if two colleagues from different contexts are contributing the same time and work as co-principal investigators. We hope that our learners would recognise this, and aim for pay equity, while recognising that working within existing structures may make that challenging. They are then able to come back to the group and have further discussions for feedback. These pragmatic experiences in conjunction with the didactics provided by our curriculum, drive the learner to consider how their work specifically relates to the historical context and pedagogical theory that perpetuates these behaviours and structural barriers to global health equity. As in the example above, through our curriculum, learners have begun to question current grant mechanisms and funding structures and consider how they may advocate for and create funding opportunities that promote locally driven innovation, knowledge and control.

This cycle is a continuous, life-long process of learning in which the learner engages with partners throughout their career, encounters new individuals and systems, and their theoretical concepts of decoloniality are challenged by existing realities. Learner progression in such a model can be difficult to measure as the traditional learner levels and progression are based on Western, often colonial models and there are no existing tools which measure the level and progress of learners. We ask participants to describe and reflect on conversations, challenges and encounters with local colleagues and structures they encounter in their work and explicitly seek feedback on their engagement throughout their fellowship. We recognise that continued decoloniality praxis in global health is a challenging process requiring intentionality. It is easy to fall back into colonial practices in systems designed to benefit those who embrace the status quo. However, it is our hope that through our curriculum, learners will build the skills needed to continue engaging in this praxis of decoloniality throughout their careers.

Challenges in the implementation of praxis-based curriculum

Until the implementation of this curriculum, the education of our global health fellows had been largely focused on ‘traditional’ concepts of global health including care provision and educating health workers in LMICs (Daffé et al., Citation2021), programme management, and global burdens of disease (Sawleshwarkar & Negin, Citation2017). While these skills are critical to professional development, these concepts must be considered through the lens of decoloniality and those aspects of knowledge which may be oppressed through epistemologies of the Global North (Naidu, Citation2021).

While this curriculum provides both the theory and space for reflection needed in the context of active engagement in global health work, there were many challenges we encountered in the implementation of a curriculum centred on the praxis of decoloniality. We aim to further explore each pragmatic challenge with solutions and examples guided by Frierian pedagogy.

Cognitive disequilibrium

‘Cognitive disequilibrium’, as described by Piaget, is a phenomenon in which new information does not fit into one’s existing mental frameworks (Lodge et al., Citation2018). A decoloniality curriculum is specifically intended to disrupt existing understandings of structures and how knowledge is conceptualised (Naidu, Citation2021). For many learners, they may be able to hear the lessons, and even recognise the concepts, but implementation of these concepts may create a challenge. The intent of a praxis cycle within a curriculum focused on decoloniality is to intentionally create discomfort through cognitive disequilibrium and then provide a supportive discussion forum for learners (i.e. the previously described small group discussion forum) to address and overcome this disequilibrium. This forum then promotes a new and more comprehensive understanding of the material.

As an example, a decoloniality curriculum can induce cognitive disequilibrium in a Western-based learner by challenging the assumption that Western medical practices are superior and transportable to global partner sites. Though there may be Western-driven scientific evidence that learners draw on in assuming superiority of their practices, when they arrive at their partner institution, they start to grapple with local realities such as epidemiology, resources, local protocols, contexts, cultures, and goals and realise that their ‘knowledge’ of best practices may not apply in this setting. This can create cognitive disequilibrium because there may be truth in both the ‘Gold Standard’ diagnostics based on Western science, and the alternative ways to practice medicine taught in other contexts (Chowdhury et al., Citation2019).

A key aspect of addressing cognitive disequilibrium is recognising this discrepancy between structures and expectations, and beginning to identify colonial practices which have been unintentionally perpetuated. Learners overcome this disequilibrium through active partner engagement and the constant return to theory and reflection. For instance, one learner sought to teach about developmental milestones in children, but learned that due to cultural differences in socialisation with parents and families, paediatrics development was different in the local context than in the United States. Clinical education may require a different understanding of the material and therefore requires local collaboration to develop effective curricula (Keller, Citation2017). Though time intensive, learners must be able to continue to reassess their interactions through the praxis cycle in order to intentionally process this cognitive disequilibrium.

In order to grow, learners must actively practice and implement the ideas they learn. They will undoubtedly err, but they must be allowed to reflect on such mistakes, and be supported to rectify, and learn from these occurrences. The learner above, was able to engage with their local partner and develop a deeper understanding of the context, learning from their experience. Realising that although they were hired for a role of teacher, they had their own areas of needed growth. Without this space, learners lose a key component of Freirean pedagogy – the idea that action is the process of changing and uncovering real needs. If this space does not exist, it is easy to be paralysed by the imperfection inherent in global health work and the promotion of true equity and decoloniality will become merely a theory.

Structural barriers

Success of decoloniality education for fellows can collide with existing structures in place that dictate how global health is practiced within academic medicine. One example which we encountered was in the execution of scholarly work for our global health fellows. In our curriculum fellows must come to an understanding that, to be effective, global health projects should be collaborative and centre the needs and priorities of the community and stakeholders most impacted by the work. However, even as a learner engages in reconstructing a new cognitive framework for carrying out projects as a true partnership, they often face institutional requirements or funding deadlines that require development of a project long before the learner has had the opportunity to meet local partners, understand local contexts, and collaboratively develop project ideas. In our programme we have tried to move away from requiring project development a priori, and allowing fellows to spend time with local colleagues and in their new context before collaborating on projects or initiatives. However, this remains a challenge for our learners and even educators when applying for the initial travel funding. Global health educators must help learners navigate the often-competing priorities of their Western institutions and local partners, understanding that these challenges will continue long past fellowship.

While this may be contrary to one’s own academic achievement, it is critical that we continue to engage in this curriculum. Colleagues we have spoken with have had success in independent discussions with mentors and supervisors to create pathways specific to those conducting research in LMICs. For instance, academic promotions committees may consider mentorship or a second author, or co-first authors on manuscripts more strongly if the co-author is equally engaged, but from a low-resource setting. While there is an inherent tension in one’s individual career advancement and true global equity, providing learners with this understanding and knowledge provides a foundation to work creatively and diligently to address this tension. We intend for our learners to recognise this tension and work to change the systems they work within.

As Friere has said, ‘those who authentically commit themselves to the people must re-examine themselves constantly’ (Freire Institute, Citation2022). A key component of changing these structures is the development of partnerships at all levels – individual, institutional and country level. Only about a quarter of board members in global health organisations are from LMICs, while 44% come from the United States alone (Lu, Citation2022). This is one demonstration of how HICs continue to set priorities for local projects (Kwete et al., Citation2022). Addressing this structural barrier to equity requires people in positions of power to reflect on how to shift power and seek out diverse voices as an intentional process (Lu, Citation2022). For many, to recognise the value in local knowledge, expertise and leadership, rather than attempt to change it entirely (through historically colonial perspectives) is counter to traditional teaching around global health leadership, and Western criteria for academic advancement.

Additionally, projects run by Global North partners often add to the workload of an already overstretched local partner. For instance, an initiative to improve identification of neonatal sepsis for early detection will require operational set up, training for nursing, etc. For training to occur, nurses will also need to take time away from work and do the training on their own time without pay. Operational setup and administrative work may fall on a local physician who is already running a ward of fifty patients alone. Even on projects that are priorities for the local partner, this additional work may be a significant burden affecting not only their workload but also their income earning potential as it may limit their time for private clinic work and other more lucrative endeavours. In contrast, Global North practitioners may have funded time that allows them the freedom to work on the project without overburdening them. A primary challenge in partnership development is the balance of not overburdening local colleagues, recognising asymmetry in resources and time, but also ensuring that local priorities and voices are directing global health work. Our learners grapple with this tension in their work with local colleagues. They consider how they are able to use their positionality to advocate for their local colleagues, while still building capacity and not promoting their own agendas.

Though this tension remains a key challenge in decoloniality education, engaging with global partners as early and often as they are willing provides depth and broadens the experience for learners. Through constant reflection, we note that those in longer-term partnerships are better able to address these challenges. While there are structural barriers to a true bi-directional partnership, individual relationships are often critical in navigating these barriers. We expect learners to intentionally prioritise the ideas and work of local colleagues and seek out diverse voices as described above. This is a first step to changing the status quo. By building true personal and professional relationships between Western and non-Western colleagues, the institutions that these individuals represent can become examples within their own spheres of influence and continue to progress along the social-ecological framework to create structural change over time.

Accountability

The transition from reflection to the true action of decoloniality is a constant challenge, and is difficult for global health educators to assess in a learner. Learners may be able to reflect in a group about the inequities they see, they may even be willing to name their own privilege and positionality, as defined by M. Duarte (CTLT Indigenous Initiatives, Citationn.d.). However, for a competency-based curriculum in decoloniality, there are no established mechanisms in place to ‘measure’ a successful bi-directional partnership, or a mutually respectful interaction by both parties. Furthermore, HIC learners may say the ‘right’ thing, but in the moment may still rely on their privilege to promote their own advantage or priorities, often unknowingly causing harm. In our educational model, we have developed learner milestones specific to a decoloniality-based approach and we have built in accountability by encouraging learners to dialogue, seek feedback from global partners, and through peer mentorship in small group discussions focused on specific encounters and experiences (Ratner et al., Citation2022).

Obtaining feedback from local partners on learners or practitioners from HICs is ideal but requires deep relationships and trust on both sides - both for partners to be able to provide feedback, and for learners to be able to hear it. Additionally, Western conceptions of feedback often differ from those in other contexts. Existing hierarchies and cultural norms may preclude frank feedback as it is used in the United States. Learners, such as fellows, who are past the traditional student or resident stage, are often not observed or ‘graded’ in their work. While more formal feedback can be challenging to obtain, informal conversations with longstanding partners are often very effective in gaining insight into learner performance and interactions. We have also asked learners to further examine the colonial dynamics at play in receiving feedback from partners as it may occur in the form of unearned flattery. Learners are encouraged to ask for feedback from local colleagues with whom they have safe relationships with and will most likely feel comfortable speaking openly, paying careful attention to continued nuanced elements of positionality when doing so.

Shared reflection with peers can also provide an internal feedback mechanism. However, in order to do this successfully, there must be a culture of psychological safety whereby one feels comfortable moving beyond their comfort zone. Community engagements are focused on respect for ideas, regular active participation and an understanding of good intention. It requires a culture that promotes shared respect and support for learners to grow from mistakes. In this environment, learners are able to consider their role and impact in promoting or dismantling colonialism.

Addressing challenges through critical pedagogy to dismantle structural forces

Ultimately, it is our hope that the implementation of this curriculum goes beyond theoretical conceptualizations of structural inequity, and pushes learners to engage with the material in an ‘action oriented’ way, providing them with the insight and skills to become advocates for change. Our work seeks to implement the work of many scholars from around the world who have developed these concepts. While this curriculum will not singularly eliminate inequities and unbalanced power dynamics in global health practice, this is a critical step for practitioners to unlearn colonial practices and to consider new concepts of collaboration, partnership and leadership in their work. While many of the existing global health curricula focus on a theoretical understanding of global health and structural determinants of health, through our curriculum, learners develop the ability to understand and question where these traditional sources of knowledge are derived. Learners then implement this new insight, practice their skills, and reflect on challenges through their global collaborations. Global health practitioners must consider how to restructure these systems by continuingly asking who is not at the table, centreing local colleagues, and advocating for the inclusion of marginalised voices.

We recognise that global health education, through a lens of decoloniality and true praxis is a lifelong process. Decoloniality and the introduction of structural competency in global health practice continues to take place in a system that promotes leaders who may also have a more traditionally western outlook and those who have benefitted ancestrally from colonial civil service (Mogaka et al., Citation2021). Grappling with these realities and the historical context of global health practice is fundamental to the dismantling of colonial systems. Teaching and practicing decoloniality requires each practitioner, educator and learner from the Global North to push against existing structures that may be resistant to this change as well as one’s own biases and instincts which may be unsettling. Global health practitioners and learners alike are often bound by financial commitments to funders, academic ambitions, desire for promotion, and deliverable deadlines. All of these factors, in addition to the colonial roots of global health education, are barriers to true equity. However, these are the systems within which praxis must occur.

Limitations

We recognise that we are also products of the systems in which we have lived, learned and worked.

As we developed our curriculum and identified key concepts and ideas to be included, our literature search, articles, podcasts, and learning materials were often drawn from Western knowledge bases despite attempts to include diverse voices and perspectives as much as possible. The curriculum objectives were distributed to multiple experts within the field of decoloniality and equity across disciplines including medicine, public health, policy, and anthropology from both the Global North and Global South and Indigenous contexts and refined based on their input. However, we are lacking view points from community organisations, and many other key demographics. Despite this broad input, ultimately the curriculum itself was designed by US-based academic physicians who have been raised and educated in a colonial framework, still learning how to more actively lean-out and work towards decoloniality and equity. Though we solicited input from a variety of disciplines and colleagues in global and Indigenous contexts, the original creation was intentionally of Western origin because much of this work to decolonise feels inherently our responsibility as practitioners from colonising countries.

It is also important to consider that our discussion of decoloniality education based in praxis is focused on global health practitioners who have identified global health as a career and are actively pursuing this work. It has not been attempted or considered with learners who will primarily engage in shorter term global health work. We recognise that some accomplished and well-intentioned global health practitioners may have a different perspective or outlook on the evolution of global health as a field and the emphasis on decoloniality. However, we believe critique of the true impact of global health efforts will continue to grow and will affect all aspects of global health work, including funding. Such colleagues can be encouraged to dialogue with their own local colleagues about how they perceive programmes and projects. These conversations may serve as a first step in their own praxis journey and a practice in decoloniality. As we noted at the start of the article, global health is revered as an ‘evolved field’. However true evolution requires constant change and an openness to progress.

Next steps

Educating learners on decoloniality and global health equity through praxis is critical to changing existing structures in a complex, historically embedded framework of colonialism. As we have seen, the theory of decoloniality is often at odds with how global health is practiced and it is through slow, continued praxis that we can start to see change. The challenges which we have encountered in implementing a decoloniality curriculum based in praxis demonstrate the need for structural advocacy not only on the global stage, but within our own institutions. It is our hope that education through a lens of decoloniality will ultimately create a generation of global health practitioners who are able to dismantle the current colonial practices which lead to continued oppression and recreate the field of global health into one based on equity and respectful partnerships.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Michelle Niescierenko, the Director of the Global Health Program and Boston Children’s Hospital and her support of this curriculum, to all of our colleagues who provided feedback on the earliest iterations of our curriculum objectives and to our local colleagues who engage with and support our learners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahn, R., Tester, K., Altawil, Z., & Burke, T. (2015). The need for professional standards in global health. AMA Journal of Ethics, 17(5), 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2015.17.5.pfor2-1505

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2022). A decolonized lens through a novel anti-racism curriculum for global health. Consortium of Universities of Global Health.

- Astle, B., Faerron Guzman, C., Landry, A., Romocki, L., & Evert, J. (2018). Global health education competencies toolkit (2nd ed.). Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH) Education Committee.

- Beaglehole, R., & Bonita, R. (2010). What is global health? Global Health Action, 3(1), 5142. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

- Centers for Disease Control. (2022, May 17). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

- Chowdhury, S., Laux, T., Morse, M., Jenks, A., Stonington, S., & Jain, Y. (2019). Democratizing evidence production – A 51-year-old man with sudden onset of dense hemiparesis. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(16), 1501–1505. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1907988

- Conatz, J. (2012, May 9). The limits of contemporary anti-oppression theory and practice. Libcom.Org. https://libcom.org/article/limits-contemporary-anti-oppression-theory-and-practice.

- Cox, J. T., Kironji, A. G., Edwardson, J., Moran, D., Aluri, J., Carroll, B., Warren, N., & Grace Chen, C. C. (2017). Global health career interest among medical and nursing students: Survey and analysis. Annals of Global Health, 83(3–4), 588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2017.07.002

- Crane, J. T. (2010). Unequal ‘partners’. AIDS, academia, and the rise of global health. Behemoth, 3(3), 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1524/behe.2010.0021

- CTLT Indigenous Initiatives. (n.d.). Positionality & intersectionality. University of British Columbia. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://indigenousinitiatives.ctlt.ubc.ca/classroom-climate/positionality-and-intersectionality/#:~:text=Positionality%20refers%20to%20the%20how,%2C%20Misawa%20(2010%2C%20p.

- Daffé, Z. N., Guillaume, Y., & Ivers, L. C. (2021). Anti-racism and anti-colonialism praxis in global health—reflection and action for practitioners in US academic medical centers. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 105(3), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0187

- equalhealth.org. (2022, November 25). Social medicine course: Global health in local contexts: A transnational experiential course on the social determinants, health equity, and leading change. http://www.equalhealth.org/socialmedicine-2022.

- Fisher, K. E. (2022). People first, data second: A humanitarian research framework for fieldwork with refugees by war zones. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 31(2), 237–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-022-09425-8

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc.

- Freire Institute. (2022). Concepts used by Paulo Freire. https://www.freire.org/concepts-used-by-paulo-freire.

- Harvey, M., Neff, J., Knight, K. R., Mukherjee, J. S., Shamasunder, S., Le, P. v., Tittle, R., Jain, Y., Carrasco, H., Bernal-Serrano, D., Goronga, T., & Holmes, S. M. (2022). Structural competency and global health education. Global Public Health, 17(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1864751

- Howard, T. C. (2003). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Ingredients for critical teacher reflection. Theory Into Practice, 42(3), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4203_5

- Keikelame, M. J., & Swartz, L. (2019). Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Global Health Action, 12(1). Article 1561175. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175

- Keller, H. (2017). Culture and development: A systematic relationship. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 833–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617704097

- Khan, T., Abimbola, S., Kyobutungi, C., & Pai, M. (2022). How we classify countries and people—And why it matters. BMJ Global Health, 7(6), e009704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009704

- Kienhues, D., & Bromme, R. (2012). Exploring laypeople’s epistemic beliefs about medicine – A factor-analytic survey study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 759. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-759

- Kohn, M., & Reddy, K. (2017). Colonialism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://mla2020.voices.wooster.edu/2020/01/19/colonialism/

- Kusnanto, H., Agustian, D., & Hilmanto, D. (2018). Biopsychosocial model of illnesses in primary care: A hermeneutic literature review. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 7(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_145_17

- Kwete, X., Tang, K., Chen, L., Ren, R., Chen, Q., Wu, Z., Cai, Y., & Li, H. (2022). Decolonizing global health: What should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Global Health Research and Policy, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-022-00237-3

- Lodge, J. M., Kennedy, G., Lockyer, L., Arguel, A., & Pachman, M. (2018). Understanding difficulties and resulting confusion in learning: An integrative review. Frontiers in Education, 3, Article 49. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00049

- Lu, J. (2022, April 8). Men – Especially from rich countries – Still fill the boards of global health groups. Goats and Soda-National Public Radio.

- Lucero, E. (2011). From tradition to evidence: Decolonization of the evidence-based practice system. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.628925

- Luitel, B. C., & Dahal, N. (2020). Conceptualising transformative praxis. Journal of Transformative Praxis, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3126/jrtp.v1i1.31756

- Metzl, J. M., & Hansen, H. (2014). Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032

- Milligan, K., Zerda, J., & Kania, J. (2022). The relational work of systems change. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://doi.org/10.48558/MDBH-DA38. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_relational_work_of_systems_change#

- Mishra, P. (2021, November 29). Frantz Fanon’s enduring legacy. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/12/06/frantz-fanons-enduring-legacy.

- Mogaka, O. F., Stewart, J., & Bukusi, E. (2021). Why and for whom are we decolonising global health? The Lancet Global Health, 9(10), e1359–e1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00317-X

- Naidu, T. (2021). Modern medicine is a colonial artifact: Introducing decoloniality to medical education research. Academic Medicine, 96(11S), S9–S12. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004339

- Pine, A. (2013). Revolution as a care plan: Ethnography, nursing and somatic solidarity in Honduras. Social Science & Medicine, 99, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.028

- Qato, D. M. (2022). Reflections on ‘decolonizing’ big data in global health. Annals of Global Health, 88(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3709

- Ratner, L., Sridhar, S., Rosman, S. L., Junior, J., Gyan-Kesse, L., Edwards, J., & Russ, C. M. (2022). Learner milestones to guide decolonial global health education. Annals of Global Health, 88(1), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3866

- Sawleshwarkar, S., & Negin, J. (2017). A review of global health competencies for postgraduate public health education. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00046

- Schleiff, M., Hansoti, B., Akridge, A., Dolive, C., Hausner, D., Kalbarczyk, A., Pariyo, G., Quinn, T. C., Rudy, S., & Bennett, S. (2020). Implementation of global health competencies: A scoping review on target audiences, levels, and pedagogy and assessment strategies. PLOS ONE, 15(10), e0239917. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239917

- Stonington, S. D., Holmes, S. M., Hansen, H., Greene, J. A., Wailoo, K. A., Malina, D., Morrissey, S., Farmer, P. E., & Marmot, M. G. (2018). Case studies in social medicine – Attending to structural forces in clinical practice. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(20), 1958–1961. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms1814262

- Taylor, M. J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., Darzi, A., Bell, D., & Reed, J. E. (2014). Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(4), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

- Tinker Sachs, G. (2014). Reclaiming praxis – A tribute to Paulo Freire!. Ubiquity – Praxis, Inaugural Edition.

- Trembath, S. (n.d.). Decoloniality. American University Subject Guide. Retrieved August 20, 2022, from https://subjectguides.library.american.edu/c.php?g=1025915%26p=7715527.

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples.

- University of California-San Francisco (UCSF). (2022, November 25). Health equity curriculum. https://globalsurgery.org/health-equity-curriculum/.

- Wilson, C. (2022). Engaging decolonization: Lessons toward a theory of change for transforming practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 2(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2053672