ABSTRACT

Cancer is becoming a public health issue in the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This systematic review aims to synthesise psychosocial interventions and their effects on the health outcomes of adult cancer patients and their family caregivers in SSA. We identified eligible publications in English language from PubMed, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature Plus with Full Text, Embase, APA PsycInfo, Scopus, and African Index Medicus databases. We included psychosocial interventions targeted adult cancer patients/survivors or their family caregivers in SSA. This review identified five psychosocial interventions from six studies that support adult cancer patients and their family caregivers in SSA. The interventions focused on providing informational, psycho-cognitive, and social support. Three interventions significantly improved quality of life outcomes for cancer patients and their caregivers. Significant gaps exist between the rapidly increasing cancer burdens and the limited psychosocial educational interventions supporting adult cancer patients and their families in SSA. The reviewed studies provide preliminary evidence on development and testing interventions that aim to improve patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life.

Introduction

Although communicable diseases continue to dominate Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), cancer is becoming a public health issue in this region as a result of aging and lifestyle changes (Gouda et al., Citation2019; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Citation2018). About 801, 392 new cancer cases were diagnosed in 2020, and the number of new cases per year is projected to increase 70% by 2030 (Bray et al., Citation2022; International Agency for Research on Cancer, Citation2018). The cancer mortality rates in this region have also increased and about 520,158 deaths were estimated to have occurred in SSA in 2020 (Bray et al., Citation2022; Larkin, Citation2022). This reported cancer burden may have been underestimated due to poor access to health services and low quality of cancer data systems (Morhason-Bello et al., Citation2013). Because of the cost of oncological care, limitations in infrastructure, and insufficient numbers of healthcare providers, many countries in SSA face multiple challenges to meet the increasing demand for cancer services (Kingham et al., Citation2013).

Our recent systematic review suggested that cancer has a significant impact on all aspects of quality of life (QOL) for cancer patients and their family caregivers in SSA (Qanir et al., Citation2022). Similarly, other researchers have found that cancer patients in SSA often suffer from pain, lack of energy, sleeping difficulties, depression, and reduced social activities (Kugbey et al., Citation2019; Ndiok & Ncama, Citation2018). Additionally, families are intensely involved in the care of patients and take on enormous caregiving responsibilities due to limited cancer care resources (Kizza & Muliira, Citation2020). In addition to caregiving, family caregivers must continue to perform their other duties such as income earning and caring for other family members (Githaiga, Citation2015). These stressors lead to a wide range of negative effects on physical and mental health, including poor eating, lack of sleep, loss of hope, distress, and isolation (Muliira et al., Citation2019; Onyeneho & Ilesanmi, Citation2021). Although clinical practice guidelines have included recommendations for providing psychosocial supportive care for people with cancer (Jacobsen & Lee, Citation2015), the psychosocial needs of cancer patients and family caregivers are often undetected, and healthcare systems have failed to provide care and services to improve their QOL.

To meet the supportive care needs of cancer patients and family caregivers, research on psychosocial interventions has been conducted worldwide (Song et al., Citation2021). Psychosocial interventions, generally defined as nonpharmacological interventions including a variety of psychological and education components (National Cancer Institute, Citation2022), offered to cancer patients and family caregivers have been effective in increasing self-efficacy and ability to cope, enhancing meaning and purpose, and improving QOL (Gabriel et al., Citation2020; Northouse et al., Citation2010; Park et al., Citation2019). However, most psychosocial interventions have been conducted in developed countries, research in this area in SSA is limited (Gabriel et al., Citation2020; Onyeka et al., Citation2022). Additionally, how to adapt supportive care guidelines from resource-rich countries to countries with limited resources, fewer healthcare professionals and specialists, and different sociocultural context remains questionable. Therefore, this systematic review aims to synthesise the psychosocial interventions for adult cancer patients and/or their family caregivers in SSA and examine the effects of these interventions on the health outcomes of adult cancer patients and their family caregivers.

Methods

We developed a comprehensive systematic review protocol based on the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., Citation2021). The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020152838).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were detailed according to the Population, Interventions, Comparator, Outcomes and Study design(s) (PICOS) framework (Liberati et al., Citation2009). To meet the inclusion criteria, publications must have: (1) targeted adult (> = 18 years old) cancer patients and/or their family caregivers in SSA; (2) included psychosocial interventions (i.e. nonpharmacological interventions including a variety of psychological and education components); (3) used randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental designs; and (4) published as full-text articles in English. Studies were excluded if they focused on participants with diseases other than cancer.

Search methods

We developed the search terms in consultation with a university health sciences librarian. The key concepts that guided the search included ‘psychosocial or supportive care’, ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’, ‘cancer’, ‘family caregiver’, and ‘patient’. We searched the publications from the dates of inception through the final search date of October 21, 2021, in the following six databases: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus with Full Text), Embase, APA PsycInfo, Scopus, and African Index Medicus. The full electronic search strategy for all databases was the same as the team recent systematic review of studies on the prevalence and severity of overall and subdomains of QOL and their influencing factors (Qanir et al., Citation2022). We also searched the African Journals Online (AJO) database, but this search returned no new relevant articles.

The search results were exported to Endnote X8 software and duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were uploaded into Covidence™ – a web-based tool that supports systematic reviews (Cochrane community, Citation2018). Two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts and then the full text of all identified articles. We resolved any disagreements about an article’s eligibility through ongoing discussion between the two researchers. A third researcher was available to help resolve the disagreement when needed.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies

We used version 2018 of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to assess the methodological quality of the studies that used qualitative, quantitative randomised controlled trials, quantitative non-randomised, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods (Hong et al., Citation2018). We have used MMAT in a series of three systematic reviews that the team recently conducted to understand the state-of-art in cancer survivorship research and related care in SSA (Qanir et al., Citation2022). Five methodological quality criteria were used to assess each category of study design. Rating of each criterion includes responses of yes, no, or could not determine. The MMAT was not developed to create an overall score, we, thus, followed the developers’ advice to provide a detailed report of the ratings of each criterion to better inform the quality of the included studies. Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias in each of the included studies. We resolved any assessment discrepancies through team discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Four researchers independently extracted the data from the studies that met the inclusion criteria using Excel. We extracted study characteristics (e.g. study aim, theoretical basis, design), participants characteristics (e.g. sample size, cancer type and stage, age, gender), intervention characteristic (e.g. component, mode, format, duration, dosage, interventionist) and intervention outcomes. We compared the extracted data, resolved discrepancies through ongoing team discussion, and merged the data. We conducted narrative analysis to synthesise the findings instead of a meta-analysis of the outcomes because of incomplete and heterogeneous information reported in these studies.

Results

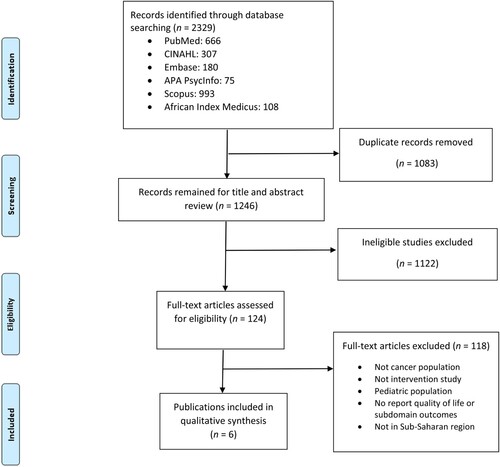

The initial search of the electronic databases yielded a total number of 2,329 records (). After removing duplicates and performing title and abstract review, we retained 124 papers for a full-text review, which yielded six articles that met the inclusion criteria for this review. Two articles reported the feasibility and effectiveness testing outcomes from the same intervention (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021).

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow chart of study identification and selection.

Study characteristics

The interventions were conducted in Nigeria (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyechi et al., Citation2016; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021), Tanzania (Morse et al., Citation2021), and Kenya (Weru et al., Citation2020). The studies reported the intervention effectiveness in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 3) (Onyechi et al., Citation2016; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021; Weru et al., Citation2020) and the intervention effects and feasibility in quasi-experimental studies (n = 3) (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021) (). All studies used control groups including ‘usual care’, ‘usual care with conventional counseling’, or ‘usual care with phone-contact’, or ‘usual care with psychoeducational material’. Two studies reported the theoretical bases that included Lazarus and Folkman's transactional model of stress and coping (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019) and WHO palliative care pillars (e.g. policy, drug availability, and implementation) (Morse et al., Citation2021). Of six studies, three studies focused on patients only (Ngoma et al., Citation2021; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021; Weru et al., Citation2020); one study focused on family caregivers only (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019); and two studies focused on both patients with cancer and family caregivers (Morse et al., Citation2021; Onyechi et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Characteristics of study and participants (n = 6).

Participant characteristics

The study sample sizes ranged from 17 to 144. Most studies included patients with different types of cancer but primarily breast cancer. Three studies reported cancer stage: two focused on patients with advanced cancer (Morse et al., Citation2021; Weru et al., Citation2020); one focused on patients from stage I to III (Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021). The ages of samples were inconsistently reported using range, mean, and percentages. Most participants were female patients and caregivers younger than 55 years of age.

Psychosocial intervention characteristics

The interventions included rational-emotive hospice care therapy (Onyechi et al., Citation2016), dignity therapy (Weru et al., Citation2020), psychoeducation (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021), and symptom management and communication (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021). The intervention components can be categorised as providing informational, psycho-cognitive, and social support. Information support included information about cancer and treatment, psychosocial factors in cancer, self-care, nutrition, and practical tips and information (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021). Psycho-cognitive components involved psychological wellbeing, cognitive functioning, motivation to change dysfunctional emotions and thoughts, decision-making process, cognitive restructuring, confrontation, acceptance and coping strategies (Onyechi et al., Citation2016). Social support included communication strategies, therapeutic alliance, and multigenerational family therapy (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021; Onyechi et al., Citation2016). These interventions were delivered by nurses (n = 2) (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyechi et al., Citation2016), a trained counsellor (n = 1) (Weru et al., Citation2020), clinical psychologists and a doctor (n = 1) (Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021), and a multidisciplinary team of palliative care specialists, health services researchers, engineers, and designers (n = 2) (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021). The modes of delivery included in-person (n = 4) (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyechi et al., Citation2016; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021; Weru et al., Citation2020) and mobile/ computer app (n = 2) (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021). The intervention duration and session varied significantly across studies, ranging from 1 d/1 session (Weru et al., Citation2020), 6 weeks/6 sessions (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019), 8 weeks/8 sessions (Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021), 14 weeks/14 sessions (Onyechi et al., Citation2016), to four months by app (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021). The length of each session ranged from 30 (Weru et al., Citation2020) to 90 min (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019; Onyedibe & Ifeagwazi, Citation2021) .

Table 2. Interventions characteristics and effect (n = 6).

Effects of psychosocial interventions

Five studies reported the intervention effects on the QOL outcomes of patients and their caregivers. In a RCT that targeted both cancer patients and their caregivers, Onyechi et al. (Citation2016) reported significant improvement in psychological status (i.e. less problematic assumptions, low anxiety, and low psychological distress) among participants in the intervention group compared to those in the control group over time. In their RCT that focused on patients, Weru et al. (Citation2020) reported no significant group difference in QOL. In their quasi-experimental study focused on family caregivers, Gabriel and Mayers (Citation2019) reported a greater improvement in the overall QOL in the intervention group as compared to the control group. Onyedibe and Ifeagwazi (Citation2021) reported in their RCT that patients in the intervention group reported significant decrease in maladaptive cognitive regulation (i.e. self-blame, rumination and catastrophizing) over time. In the two studies that used quasi-experimental design to examine the usability and effectiveness of an eHealth intervention, the respondents reported that the app was easy to use and the acceptability would improve with increased experience using the app (Morse et al., Citation2021); however, no significant differences in symptom severity between groups in the follow-up pilot study testing the intervention effectiveness (Ngoma et al., Citation2021).

Risk of bias assessment

summarises the quality assessment of the publications. The three RCTs fulfilled the criteria of baseline balance and completed outcome data, but only two RCTs performed randomisation appropriately. Two RCTs failed to report how research blinding was conducted. Of the three quasi-experimental studies, one didn’t use appropriate measurements or provide complete outcomes data, the other two studies didn’t account for the effects of confounders in the design and analysis. None of these six studies reported whether the intervention was administered as intended.

Table 3. Quality of articles summary utilising the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018.

Discussion

As the number of cancer patients is drastically increasing in SSA, cancer burden has become a major public health problem. This review revealed the scarcity of psychosocial interventions to meet the rapidly increasing needs of cancer patients and family caregivers in SSA. From six major databases, we only identified five psychosocial interventions from six studies to support adult cancer patients and their family caregivers in SSA. This review identified multiple potentially effective psychosocial intervention components including informational, psycho-cognitive, and social support. Three studies reported significant positive intervention effects on QOL outcomes among patients and their caregivers.

The low number of psychosocial interventions may suggest that psychosocial supportive care continues to be of low priority in SSA despite the accelerating cancer burden in SSA (Bray et al., Citation2022). This may be due to the competing priorities of infectious diseases (e.g. HIV/AIDS), and a lack of investment in the oncologic care infrastructures by governments, including funding for system support and healthcare providers. The discrepancy between the rapid increasing cancer burden and the lack of survivorship support programmes may suggest that there is an urgent need to develop culturally appropriate psychosocial interventions and conduct appropriately designed clinical trials to generate evidence for supportive care for cancer patients and their family caregivers in SSA.

This review has identified multiple psychosocial intervention components that focused on providing informational, psycho-cognitive, and social support. There are considerable variations in the combinations of different intervention components in these studies, which may reflect researchers’ efforts to meet various supportive care needs for cancer patients and caregivers in SSA. Different from varied intervention components, the modes of intervention delivery have been in-person except one intervention that used a mobile app format to provide end-of-life support for cancer patients (Morse et al., Citation2021; Ngoma et al., Citation2021). Even though no significant differences in symptom severity were found between the patients in the intervention group and those in the control group in the mobile app pilot study using a quasi-experimental design (Ngoma et al., Citation2021), it is noteworthy that patients reported high satisfaction with the care that the intervention provided (e.g. availability of treatment, access to health providers and emotional support). The demonstrated acceptability and usability of the mobile app intervention among patients and caregivers may suggest the potential to improve health outcomes for cancer patients and their caregivers in the resource-limited SSA region through remote access to psychosocial supportive care as the adoption of mobile technology increases (Morse et al., Citation2021). Future studies with sufficient powers are needed to investigate the effectiveness of mHealth psychosocial interventions on improving the health outcomes of cancer patients in the SSA region.

Out of the five interventions, three demonstrated statistically significant effects on the health outcomes of cancer patients and their family members. Outcome measures varied between these studies as did their results in several areas including improvement in overall QOL, improvement in psychological status (i.e. less problematic assumptions, low anxiety, and low psychological distress), and increased adaptive cognitive regulation (i.e. self-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing). However, some studies used measurement tools that have not been validated in the SSA population to evaluate the intervention effects (Weru et al., Citation2020), suggesting that additional research is needed to culturally validate the instruments in the SSA population to improve research rigour.

This review also revealed the challenges in conducting psychosocial intervention research in SSA. For example, recruitment of participants can be challenging because some cancer patients declined participation due to stigma and inadequate knowledge about the interventions (Weru et al., Citation2020). Additionally, culture, personality, and some sociodemographic factors (e.g. income) may also not have been fully explored and incorporated into these intervention programmes (Gabriel & Mayers, Citation2019). Moreover, Gabriel and Mayers (Citation2019) noted that the lack of significant improvement in caregiver’s financial concerns between the groups might be due to the limited basic financial resources because most participants were already unemployed and remained so throughout the intervention. These findings suggest that future research needs to better understand the cultural context and to evaluate the cultural adaptations of interventions. Mounting evidence has supported the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions on improving the health outcomes of cancer survivors and their family caregivers in the non-SSA countries. To better meet the supportive care needs of Sub-Saharan Africans with cancer and their families, future research may culturally adapt existing interventions using the WHO Step-by Step approach (language, culture, content, and context) in such a way that the intervention is compatible with an individual’s cultural beliefs, meaning, and values; the adapted intervention should be rigorously evaluated for their cultural relevancy and effects in the context of limited resources and the SSA cultural environment (Carswell et al., Citation2018; Marsiglia & Booth, Citation2015).

The review has the following limitations. First, the heterogeneity in the research designs and measurements of the small number of reviewed studies has made it impossible to determine which intervention component works the best to improve outcomes. Second, this review only included only six studies that were published in peer-reviewed literature in English. Due to personnel constraints, non-English, grey literature, and unpublished literature were excluded, which might have resulted in potential publication bias. Articles published in other languages could have provided additional relevant information. Finally, SSA is a large, culturally diverse region, and the results of the reviewed studies may have limited generalizability.

Recommendations for future action on psychosocial interventions for cancer patients and family caregivers in the SSA:

Recognise the importance of and integrate psychosocial care into mainstream oncologic services.

Reduce cancer-related stigma through public education.

Consider the social and culture context of patients and caregivers when design and evaluate psychosocial behavioural interventions.

Support SSA researchers and clinicians to develop psychosocial interventions through international collaborative research, education, and training.

Promote evidence-based cancer service policy making to meet the needs of cancer survivors and their families in SSA.

As the cancer burden continues to grow in SSA, the need for a rapid increase in psychosocial interventions becomes more urgent. The six studies in this review have provided preliminary evidence and lessons learned for researchers and clinicians to design and develop psychosocial interventions that aim to improve patients’ and caregivers’ QOL in SSA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bray, F., Parkin, D. M., Gnangnon, F., Tshisimogo, G., Peko, J. F., Adoubi, I., Assefa, M., Bojang, L., Awuah, B., Koulibaly, M., Buziba, N., Korir, A., Dzamalala, C., Kamate, B., Manraj, S., Ferro, J., Lorenzoni, C., Hansen, R., Nouhou, H., … Chingonzoh, T. (2022). Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2020: A review of current estimates of the national burden, data gaps, and future needs. The Lancet Oncology, 23(6), 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00270-4

- Carswell, K., Harper-Shehadeh, M., Watts, S., van’t Hof, E., Abi Ramia, J., Heim, E., Wenger, A., & van Ommeren, M. (2018). Step-by-Step: A new WHO digital mental health intervention for depression. Mhealth, 4, 34. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2018.08.01

- Cochrane community. (2018). About covidence. https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/covidence/about-covidence.

- Gabriel, I., Creedy, D., & Coyne, E. (2020). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life of people with cancer and their family caregivers. Nursing Open, 7(5), 1299–1312. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.543

- Gabriel, I. O., & Mayers, P. M. (2019). Effects of a psychosocial intervention on the quality of life of primary caregivers of women with breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 38, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.12.003

- Githaiga, J. N. (2015). Family cancer caregiving in urban Africa: Interrogating the Kenyan model. South African Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246315579323

- Gouda, H. N., Charlson, F., Sorsdahl, K., Ahmadzada, S., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H., Leung, J., Santamauro, D., Lund, C., Aminde, L. N., Mayosi, B. M., Kengne, A. P., Harris, M., Achoki, T., Wiysonge, C. S., Stein, D. J., & Whiteford, H. (2019). Burden of non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2017: Results from the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet Global Health, 7(10), e1375–e1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30374-2

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., … Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2018). Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Scientific-Publications/Cancer-In-Sub-Saharan-Africa-2018.

- Jacobsen, P. B., & Lee, M. (2015). Integrating psychosocial care into routine cancer care. Cancer Control, 22(4), 442–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327481502200410

- Kingham, T. P., Alatise, O. I., Vanderpuye, V., Casper, C., Abantanga, F. A., Kamara, T. B., Olopade, O. I., Habeebu, M., Abdulkareem, F. B., & Denny, L. (2013). Treatment of cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet Oncology, 14(4), e158–e167. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70472-2

- Kizza, I. B., & Muliira, J. K. (2020). Determinants of quality of life among family caregivers of adult cancer patients in a resource-limited setting. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(3), 1295–1304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04947-2

- Kugbey, N., Asante, K. O., & Meyer-Weitz, A. (2019). Depression, anxiety and quality of life among women living with breast cancer in Ghana: Mediating roles of social support and religiosity. Supportive Care in Cancer, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05027-1

- Larkin, H. D. (2022). Cancer deaths may double by 2030 in Sub-Saharan Africa. JAMA, 327, 2280–2280. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.10019

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Marsiglia, F. F., & Booth, J. M. (2015). Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514535989

- Morhason-Bello, I. O., Odedina, F., Rebbeck, T. R., Harford, J., Dangou, J.-M., Denny, L., & Adewole, I. F. (2013). Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: A perspective from the African organisation for research and training in cancer. The Lancet Oncology, 14(4), e142–e151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5

- Morse, R. S., Lambden, K., Quinn, E., Ngoma, T., Mushi, B., Ho, Y. X., Ngoma, M., Mahuna, H., Sagan, S. B., Mmari, J., & Miesfeldt, S. (2021). A mobile app to improve symptom control and information exchange among specialists and local health workers treating Tanzanian cancer patients: Human-centered design approach. JMIR Cancer, 7(1), e24062. https://doi.org/10.2196/24062

- Muliira, J. K., Kizza, I. B., & Nakitende, G. (2019). Roles of family caregivers and perceived burden when caring for hospitalized adult cancer patients: Perspective from a low-income country. Cancer Nursing, 42(3), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000591

- National Cancer Institue. (2022). Adjustment to cancer: Anxiety and distress (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/coping/feelings/anxiety-distress-hp-pdq#section/all.

- Ndiok, A., & Ncama, B. (2018). Assessment of palliative care needs of patients/families living with cancer in a developing country. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(3), 1215–1226. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12568

- Ngoma, M., Mushi, B., Morse, R. S., Ngoma, T., Mahuna, H., Lambden, K., Quinn, E., Sagan, S. B., Ho, Y. X., Lucas, F. L., Mmari, J., & Miesfeldt, S. (2021). Mpalliative care link: Examination of a mobile solution to palliative care coordination among Tanzanian patients with cancer. JCO Global Oncology, 7(7), 1306–1315. https://doi.org/10.1200/GO.21.00122

- Northouse, L. L., Katapodi, M. C., Song, L., Zhang, L., & Mood, D. W. (2010). Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60, 317–339. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20081

- Onyechi, K., Onuigbo, L., Eseadi, C., Ikechukwu-Ilomuanya, A., Nwaubani, O., Umoke, P., Agu, F., Otu, M., & Utoh-Ofong, A. (2016). Effects of rational-emotive hospice care therapy on problematic assumptions, death anxiety, and psychological distress in a sample of cancer patients and their family caregivers in Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(9), 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13090929

- Onyedibe, M. C. C., & Ifeagwazi, M. C. (2021). Group psychoeducation to improve cognitive emotion regulation in Nigerian women with breast cancer. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2021.1932513

- Onyeka, T. C., Onu, J. U., & Agom, D. A. (2022). Psychosocial aspects of adult cancer patients: A scoping review of sub-saharan Africa. Psycho-Oncology, 32(1), 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6052

- Onyeneho, C. A., & Ilesanmi, R. E. (2021). Burden of care and perceived psycho-social outcomes among family caregivers of patients living with cancer. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8(3), 330–336. https://doi.org/10.4103/2347-5625.308678

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

- Park, C. L., Pustejovsky, J. E., Trevino, K., Sherman, A. C., Esposito, C., Berendsen, M., & Salsman, J. M. (2019). Effects of psychosocial interventions on meaning and purpose in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer, 125(14), 2383–2393. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32078

- Qanir, Y., Guan, T., Idiagbonya, E., Dobias, C., Conklin, J. L., Zimba, C. C., Bula, A., Jumbo, W., Wella, K., Mapulanga, P., Bingo, S., Chilemba, E., Haley, J., Montano, N. P., Bryant, A. L., & Song, L. (2022). Quality of life among patients with cancer and their family caregivers in the Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of quantitative studies. PLOS Global Public Health, 2, e0000098. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000098

- Song, L., Qan'ir, Y., Guan, T., Guo, P., Xu, S., Jung, A., Idiagbonya, E., Song, F., & Kent, E. E. (2021). The challenges of enrollment and retention: A systematic review of psychosocial behavioral interventions for patients with cancer and their family caregivers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(3), e279–e304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.04.019

- Weru, J., Gatehi, M., & Musibi, A. (2020). Randomized control trial of advanced cancer patients at a private hospital in Kenya and the impact of dignity therapy on quality of life. BMC Palliative Care, 19(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00614-0