ABSTRACT

This paper evaluates global health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic through the ‘two regimes of global health’ framework. This framework juxtaposes global health security, which contains the threat of emerging diseases to wealthy states, with humanitarian biomedicine, which emphasises neglected diseases and equitable access to treatments. To what extent did the security/access divide characterise the response to COVID-19? Did global health frames evolve during the pandemic?

Analysis focused on public statements from the World Health Organization (WHO), the humanitarian nonprofit Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Following a content analysis of 486 documents released in the first two years of the pandemic, the research yielded three findings. First, the CDC and MSF affirmed the framework; they exemplified the security/access divide, with the CDC containing threats to Americans and MSF addressing the plight of vulnerable populations. Second, surprisingly, despite its reputation as a central actor in global health security, the WHO articulated both regime priorities and, third, after the initial outbreak, it began to favour humanitarianism. For the WHO, security remained, but was reconfigured: instead of traditional security, global human health security was emphasised – collective wellbeing was rooted in access and equity.

Pandemics are by definition cross-border phenomena, giving rise to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) power to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). However, the WHO’s aspiration for a ‘coordinated international response’ (WHO, Citation2008, p. 9) to health emergencies confronts the reality that health policy and provision remain stubbornly national and highly variable (Greer et al., Citation2021). The COVID-19 pandemic – declared a PHEIC on January 30, 2020 – led to genuinely global initiatives to coordinate policies and treatments, but these efforts arguably fell short in the face of widespread border closures (Kenwick & Simmons, Citation2020), great power tensions (Kahl & Wright, Citation2021), and vaccine nationalism (Bajaj et al., Citation2022).

Global health governance confronts a series of structural challenges because it conjoins, or seeks to conjoin, an array of actors – national, international, and transnational – with varying priorities and unequal resources. Layered onto this is the epidemiological reality that infectious diseases vary widely in their spread and their effects while, as Patrick (Citation2020, p. 46) observes, the fear raised by pandemics ‘reinforc[es] primal instincts to impose barriers and withdraw into smaller groups.’

This paper evaluates health policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic through the ‘two regimes of global health’ framework. Following Andrew Lakoff (Citation2010, Citation2017), a central divide in global health is understood to be between global health security (wealthy northern states and the international health organisations they fund) and humanitarian biomedicine (nonprofits alleviating suffering in the global south). These regimes contrast in ethics and priorities; whereas global health security prepares to shield wealthy states from emerging infectious diseases, humanitarian biomedicine provides vulnerable populations access to treatments for neglected diseases. The north/south, emerging/actual, security/access divides are much documented in the literature on global health (e.g. De Waal, Citation2021; Jackson & Stephenson, Citation2014; Rushton, Citation2011; Shiffman & Shawar, Citation2022), while the ‘two regimes’ framework itself has been applied to prior cases including H5N1 avian flu (Lakoff, Citation2010), HIV/AIDS (Brown, Citation2015), and Ebola (Harman & Wenham, Citation2018). This paper extends this research programme to COVID-19. It asks: To what extent did the security versus access divide characterise the response to COVID-19? Did global health frames evolve over the course of the pandemic?

Analysis focused on public statements from the World Health Organization (WHO), the humanitarian nongovernmental organisation (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In addition to representing three actor types – intergovernmental, nongovernmental, and governmental – all are widely studied by scholars of global health, with the CDC and WHO held as exemplars of global health security and MSF a classic case of humanitarian biomedicine (e.g. Jackson & Stephenson, Citation2014; Lakoff, Citation2010). The research entailed a systematic content analysis of 486 policy statements (i.e. press releases, statements, and commentaries) issued by these actors during the first two years of the pandemic.

The research yielded three main findings. First, as expected, the CDC and MSF largely conformed to the global health security/humanitarian biomedicine divide in their narration of COVID-19. That is, the CDC primarily focused on pandemic preparedness and containment to protect the American public from emerging infectious diseases, while MSF emphasised the health needs of marginalised populations and condemned state measures to limit global access to lifesaving treatments. Second, despite its position as a central actor in global health security – for Davies (Citation2008), the WHO derives its authority from filling the surveillance needs of wealthy states – the WHO actually articulated both regime priorities, balancing surveillance and preparation with equity and access. Indeed, and third, after the initial outbreak phase, the balance of WHO statements tilted strongly in favour of humanitarian biomedicine. Overall, in the WHO response, security remained, but was reconfigured; instead of national security, global human health security was emphasised – a collective security rooted in ‘solidarity, fairness, transparency, inclusiveness and equity’ (WHO, Citation2021b). As the WHO (Citation2021b) stated in a commentary calling for a pandemic treaty: ‘The COVID-19 pandemic has been a stark and painful reminder that nobody is safe until everyone is safe.’

Indeed, the importance of this research derives in the first instance from the global impact of COVID-19: the WHO (Citation2022) estimated that excess mortality in the first two years of the pandemic was 14.9 million – this timeframe roughly matches this paper’s study period. Organisational frameworks and institutional priorities dictated which policies were pursued and who received lifesaving care. As De Waal (Citation2021, p. 6) observes, ‘pandemics move faster than politics’ and leaders and officials crave reassurance; in moments of uncertainty, they rely on familiar health narratives and frameworks, especially those studied in this paper. Methodologically, the content analysis approach is well suited to a comparative analysis of the frames that shape global health priorities (Shiffman & Shawar, Citation2022). Substantively, this study provides new insights into the WHO’s global health priorities, which are shown here to diverge in important respects from the security priorities of powerful states. Moreover, the analysis demonstrates that policy articulations are not static, even during the same pandemic; they evolve over time.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, it surveys the actors and institutions of global health, focusing specifically on the contrast between global health security and humanitarian biomedicine. Next, it outlines its research approach, including case selection, content analysis, and the development and application of the coding frame. It then presents and discusses the three aforementioned findings. The conclusions reflect on the WHO’s authority and on human security in health governance and offer guidance for future research.

Global health governance

Global health governance

Global health governance is motivated by the belief that collective action is required to address cross-border health concerns. Youde (Citation2017, pp. 591–592) dates its genesis to an 1834 proposal for the first international sanitary conference, though only in 1892 did states agree on limited cholera regulations, the first of 12 international health conventions. The contemporary system is largely a post-World War II creation: the World Health Organization was created in 1948 and, in 1951, the International Sanitary Regulations (renamed IHR in 1969) consolidated the pre-war health conventions and entrenched the WHO as the lead international organisation on health matters (Youde, Citation2011, p. 815). In addition to states and the WHO, global health governance brings together other intergovernmental organisations (IGOs), nonprofit actors including NGOs and foundations, public-private partnerships, and multinational corporations (Fidler, Citation2010). Nongovernmental actors, broadly defined, have played an increasingly prominent role since the 1990s, especially in the area of global health aid, where they now account for 20% of total contributions (Youde, Citation2017, p. 594).

These actors and institutions are oriented around public health, but this shared commitment conceals substantial variation in the what and the how of health. Lakoff (Citation2017) writes that there are two main ways of addressing public health concerns. They can either be understood as regularly occurring and predictable events amenable to prevention and routine management, or they can be imagined as unprecedented, potentially catastrophic events requiring preparedness. Historically – at least, since the mid-nineteenth century – public health measures relied on statistical analyses of patterns of disease incidence and pursued both immunisation and infrastructure (Lakoff, Citation2017, p. 40). This framework prevailed in the immediate aftermath of World War II, a euphoric period Snowden (Citation2019, p. 385) labels the ‘age of eradicationism.’ The development of post-colonial states was linked to the delivery of health care and the WHO’s activities focused on disease eradication (e.g. of smallpox and polio) and on primary health (Lakoff, Citation2010, p. 65).

Faith in eradication, underpinned by a belief in the stability of the microbial world, began to give way in the 1980s with the emergence of HIV/AIDS; the position became ‘untenable’ by the early 1990s (Snowden, Citation2019, p. 453). It was at this point that the category ‘emerging infectious diseases’ (EID) was coined to capture the threat of drug-resistant pathogens to the West following decades of overconfidence – and resulting disinvestment in surveillance, health infrastructure, and treatments (Snowden, Citation2019, pp. 457–458). In the mid-1990s, then especially after September 11, 2001, biodefense advocates raised concerns about bioweapons, which similarly were said to require surveillance and containment (Davies, Citation2008, p. 298; Fidler, Citation2010, pp. 5–6; Lakoff, Citation2017). While national health agencies were grappling with insufficient investment, internationally the WHO was not fit for purpose. Its main legal mechanism, the IHR, relied on passive surveillance and, worse, required notification only for a slim list of diseases – cholera, yellow fever, and plague – none of which fit the parameters of an EID (Youde, Citation2011, p. 817). The revised 2005 IHR, approved after the 2003 SARS outbreak, were emblematic of changing international health priorities. They empowered the WHO as the repository for disease surveillance information, expanded the obligations and scope of reporting required of state agencies, and included the flexible category of emerging infectious diseases (Davies, Citation2008; Youde, Citation2011).

Regimes of global health

The history of global health governance demonstrates that understandings of ‘health’ and ‘governance’ have not been consistent or static. They remain contested concepts. Fidler (Citation2010, p. 1) observes that global health is a ‘complicated governance landscape, composed of overlapping and sometimes competing regime clusters that involve multiple players addressing different health problems through diverse processes and principles.’ Lakoff (Citation2010, p. 59) starts from much the same place. Following Lakoff (Citation2010, Citation2017), this paper focuses on two contrasting regimes: global health security (GHS) and humanitarian biomedicine (HB).

Global health security consists of national health agencies like the American CDC and intergovernmental health organisations like the WHO and its regional counterparts. Its priorities echo post-Cold War developments: it emphasises the catastrophic threat of emerging infectious diseases, which are seen to originate in the global south and spread through mechanisms of globalisation. It responds to these potential threats though surveillance, outbreak investigation, and containment. Nationally, the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Approach serves as a model, while the WHO’s reformed IHR (2005) direct global responses.

Humanitarian biomedicine includes humanitarian NGOs like Médecins Sans Frontières and foundations like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation which provide tangible assistance to populations in need in the global south. For these nonprofits, the primary health focus is on actual, treatable maladies – the diseases of poverty – linked to underdevelopment, which has undermined health infrastructure and hence diminished access to treatments. Its principled approach is rooted in the value of human life regardless of borders.

The ‘two regimes’ framework has been applied to prior health emergencies, not including the cases Lakoff himself unpacks (e.g. avian flu, Zika, Ebola). For Brown (Citation2015, p. 344), the framework elucidates the biopolitics of security that inform US financial contributions to fighting HIV/AIDS. Jackson and Stephenson (Citation2014) draw on the ‘two regimes’ to contextualise the ‘neglected tropical disease’ turn in global health, which they connect to humanitarian biomedicine, in response to limitations in the prevailing focus on EIDs. Their work supports the conclusion that the two regimes have different rationales, morals, and loci of power. Similarly, O'Laughlin (Citation2016) uses the framework to diagnose the structural causes of global health inequalities and investigate corporate involvement in health. Finally, Harman and Wenham (Citation2018) directly – though not uncritically, as discussed below – apply GHS and HB to explain the different approaches undertaken by humanitarian NGOs and the WHO in response to the 2014 West African Ebola outbreak.

Beyond scholarship explicitly applying the ‘two regimes,’ the underlying concepts have wide support in the global health literature. The global health security concept is explored by Rushton (Citation2011), who describes it in ways compatible with Lakoff: it focuses on containing threatening pathogens spread by globalisation, it reflects north/south divides, and it neglects long term, preventable diseases of poverty. For Rushton, Davies (Citation2008), and Youde (Citation2011) alike, the WHO, generally, and the IHR, specifically, centralise infectious disease surveillance. Indeed, Davies (Citation2008, p. 296) argues that ‘the WHO has been a primary actor in constructing the emerging discourse of infectious disease securitization, and western states in particular have been quick to engage with this discourse.’ As for humanitarian biomedicine, research emphasises its moral underpinnings and its work across borders to treat existing maladies. As Calain (Citation2012, p. 62) writes of MSF’s support for distributive justice: ‘This finds expressions in its systematic enterprise to facilitate universal access to essential drugs and diagnostic tools, in efforts to prioritise the worst off or ‘the most vulnerable’, and in a sense of collective responsibility or ‘common humanity.’’ Similarly, Redfield (Citation2013, p. 20) emphasises MSF’s focus on ‘life in crisis’ and the NGO’s self-definition through ethics, in opposition to the politics of exclusion and resulting threats to human dignity.

presents the literature grouped according to the ‘two regimes’ framework and it showcases the support these concepts have in the literature. Harman and Wenham (Citation2018) are included, but with a caveat: while they adopt and apply Lakoff’s framework in investigating the 2014 Ebola outbreak, they also problematise aspects of it. They agree with the premise that global health security and humanitarian biomedicine are in tension, but they prefer a different division between domains: in their view, the key fault-line is between global health (including the WHO) and medical humanitarianism (MSF is a key case). For Harman and Wenham (Citation2018), the sectors are co-dependent (Lakoff (Citation2010) concedes this in his conclusions) and the main actors are active across domains. Ultimately, they maintain, both regimes occur within the broader framework of global health security – a perspective that requires moving beyond Lakoff’s narrow self-protection framework to embrace alternative framings, such as the human security approach discussed by Rushton (Citation2011) which shifts the referent of security from states to individuals and populations. This discussion continues in Section III.3.

Table 1. Two regimes of global health code list.

Research approach

To what extent did the two regimes framework play out in the COVID-19 pandemic? Following the ‘diverse’ approach to case selection, three major organisations were studied in response to this question: the World Health Organization, the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Médecins Sans Frontières. The diverse approach seeks to represent the full variation of the population of cases – here, both regimes of global health (GHS and HB) and the diversity of the organisations active in global health governance (intergovernmental, governmental, and nongovernmental). According to Seawright and Gerring (Citation2008, p. 300), diverse case selection works well when the variable is categorical (e.g. GHS vs HB); the approach also lends itself to confirmatory research (e.g. evaluating the two regimes framework).

Because the focus is on the two regimes, the three cases are not necessarily ‘typical’ (or representative) of each actor category – for instance, of all national health agencies (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008, p. 299). That said, the relevance of the research extends beyond the cases. First, the CDC, MSF, and the WHO are the most frequently studied cases in the two regimes literature (e.g. Harman & Wenham, Citation2018; Jackson & Stephenson, Citation2014; Lakoff, Citation2010, Citation2017). This maintains consistency with prior research. Second, all three organisations are central global health actors. As aforementioned, the WHO is the primary global health organisation and considered an enthusiastic (Rushton, Citation2011, p. 787) and ‘prominent’ (Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015, p. 154) proponent of global health security. The CDC is a second key actor in this regime, being one of the first to take up the issue of emerging infectious diseases in 1994, sponsoring rounds of international conferences on the topic, and even founding a new journal focused on the issue (Snowden, Citation2019, p. 469). The CDC serves as a model for other national health agencies and works directly with dozens of states internationally to promulgate its ideas: to improve surveillance, outbreak investigation, and response capacities (Kennedy et al., Citation2018). Though the CDC is better resourced than its peers, it nonetheless provides a window into wealthy state priorities, as scholarship has documented states’ shared health security frames (Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015, p. 438; Lakoff, Citation2010; Newman, Citation2022, p. 165). Finally, MSF is a paradigmatic case of humanitarian biomedicine. Recognised for its humanitarian work with the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, MSF used this award to start the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines; it emphasises human dignity and alleviation of suffering wherever it occurs, regardless of state borders (Calain, Citation2012; Redfield, Citation2013).

The research focused on what Lakoff (Citation2017, p. 8) calls ‘serious speech acts’ – the statements made by authorities in published reports and public forums – through which regimes of knowledge come into being. Categories like ‘emerging infectious diseases’ are constitutive in that they both discover and create a new phenomenon; they also privilege particular action orientations. Thus, global health frames assign meaning and significance to issues, make causal claims, articulate policy solutions, and assign importance (Shiffman & Shawar, Citation2022, p. 1978). For instance, during the West African Ebola outbreak in 2014, the dominant health frame empowered national health agencies and the WHO to the detriment of humanitarian actors like MSF and their humanitarian response activities (Harman & Wenham, Citation2018). Similarly, following Lakoff (Citation2017, p. 87)’s reasoning, when the WHO classified COVID-19 as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, this speech act elevated the outbreak, guided policy responses, and shaped the terms of debate. More generally, language matters in positioning global health actors as experts and authorities, especially in the absence of strong enforcement mechanisms (Johnson, Citation2020, p. E157).

The three organisations – specifically their public statements about COVID-19 – were subjected to content analysis. According to Krippendorff (Citation2004, p. 18), content analysis is ‘a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use.’ Content analysis was well suited to this study for its systematic approach to examining large amounts of data, its strengths in comparative analysis, and its ability to identify relative emphases and display trends over time (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2016, pp. 25–27). This research technique is widely used to analyse international and transnational organisations given that, per Krippendorff (Citation2004, p. 77): ‘Content analysis of what is said and written within an organization provides the key to understanding that organization’s reality … ’ Moreover, ‘repetitive, routine, public, and institutionalized phenomena’ – such as the ‘serious speech acts’ examined here – readily lend themselves to inferences. While the ‘words vs actions’ caveat may apply, it should be noted that the majority of the publications in this study announced or outlined policies undertaken.

The code list was derived deductively from the literature on the ‘two regimes of global health,’ as discussed in Section I and presented in . A deductive approach is considered appropriate for theory testing – namely the applicability of the two regimes to COVID-19 – and for the determination of group differences – among the CDC, WHO, and MSF (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2016, pp. 21–22; Krippendorff, Citation2004, pp. 176–178). The dyadic framing of global health security and humanitarian biomedicine, seen in contrasts like emerging/neglected and wealthy/poor, facilitated comparison. Initially, 143 codes were generated in 20 categories. These codes were refined following the test run, described below, yielding a final code list () with 122 codes in 20 categories: 60 codes for GHS and 62 for HB.

When drawn from an established literature, deductive coding is considered more reliable than inductive approaches, which place a significant interpretive burden on researchers (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2016, p. 43). The trade-off is that a priori determinations may miss terms not present in the existing literature; they also overlook latent content. Steps were taken to address these weaknesses. First, in a test run, a selection of documents was manually coded to verify the comprehensiveness of the code list. Second, word counts were included as additional data points in the analysis (Section III.1). While most key words were linked to codes, others contributed COVID-19-specific content (e.g. COVAX, a vaccine sharing initiative central to the WHO’s response). Third, a code co-occurrence analysis was conducted for specific security and protection codes (Section III.3), thereby introducing latent and contextual content (e.g. food insecurity, referents of security).

The primary source material was drawn from publicly available materials from the three focus organisations, specifically publications (press releases, statements, and commentaries) available on their ‘media’ or ‘news’ pages. The time period covered the first two years and two months of the pandemic: from the first statement by the WHO on January 13, 2020, announcing the international spread of a ‘novel coronavirus,’ through March 11, 2022, the two-year anniversary of the WHO’s pandemic declaration. The document categories were those held in common and labelled as such by the three organisations: press/news releases, statements, and commentaries. The principal investigator (PI) and two research assistants (RAs) independently evaluated sample documents to confirm that the categories were comparable across organisations. Press releases (n = 280) announced policies and provided updates on interventions. Statements (n = 155) blended policy, behavioural recommendations, and advocacy; some were associated with specific individuals (e.g. the CDC Director). Commentaries (n = 51) were lengthier and generally used to convey scientific (expert) knowledge of COVID-19. A ‘census sample’ was analysed which included all relevant texts (n = 486) in the study period (Krippendorff, Citation2004, p. 120); duplicates (e.g. a press release repeating a statement) were excluded. Because the goal was to facilitate comparison, documents falling outside of the three aforementioned categories (as labelled by the organisations) were excluded, since they lacked equivalents at other organisations.Footnote1 While this meant leaving out some organisation-specific articulations, this approach maintained consistency across organisations. The WHO (n = 238) was more prolific than MSF (n = 130) or the CDC (n = 118); in the analysis, data was ‘normalised’ to account for the different numbers of documents.Footnote2

Coding proceeded in three stages and was facilitated by ATLAS.ti, a popular Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software programme. In the first stage, a purposive (nonprobability) sample of 9 documents, 3 from each organisation, was manually coded by the principal investigator and the two research assistants. The documents included clear articulations of global health security (e.g. the WHO’s PHEIC declaration, the CDC’s initial travel restrictions) and humanitarian biomedicine (e.g. MSF’s proposal for an intellectual property waiver). Methodologically, the goal was to include content known to be representative, maximally different, or unique (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2016, p. 39). The sample spanned the roughly two-year period of study. The first stage verified that the code list was capturing everything related to the study, confirmed the mutual exclusivity of codes, and provided space to discuss and resolve differences. Several ambiguous codes were subsequently removed from the preliminary code list (e.g. ‘aid’). While this means that not every security or humanitarian articulation was included, consistent interpretations were key to the comparative analysis.

Second, the RAs independently coded 12 terms (divided between GHS and HB) for all 486 documents to establish inter-rater reliability. While the focus was largely on manifest content, Krippendorff (Citation2004, p. 88) explains that context still matters. As such, the strategy was to auto-code, but manually confirm each identified segment – akin to a ‘keyword in context’ approach – to verify that code usage matched interpretations derived from the literature. For instance, MSF critiquing wealthy states for blocking access to treatments would be coded for ‘lack of access’ but not for ‘wealthy states’ as MSF’s intention was not to prioritise wealthy state interests. Similarly, RAs were instructed to skip names of unrelated organisations or job titles (e.g. Defense Minister) and legislation or programming that did not originate from the organisation in question (e.g. the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act). Inter-rater reliability was very high.Footnote3

Finally, all 486 documents were coded. The principal investigator tested each term in ATLAS.ti to determine the appropriate search parameters (e.g. word or regular expression) and provided code interpretations. One RA coded each document for GHS and the second coded for HB to ensure consistent interpretations within both regimes. These results were regularly checked by the PI. The coding strategy was that described in stage two. The recording unit was the sentence, which allowed the researchers to capture interactions and relationships among codes, such as through co-occurrence analysis. In all, 6,306 quotes were recorded.

Findings and discussion

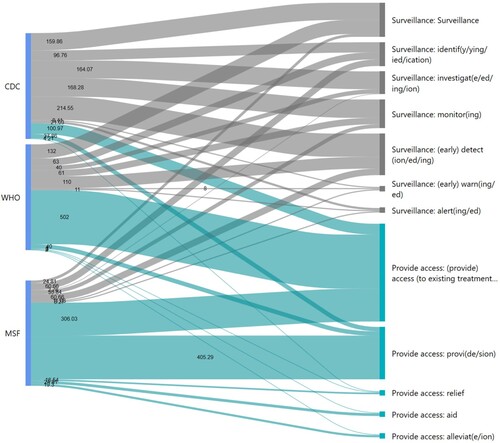

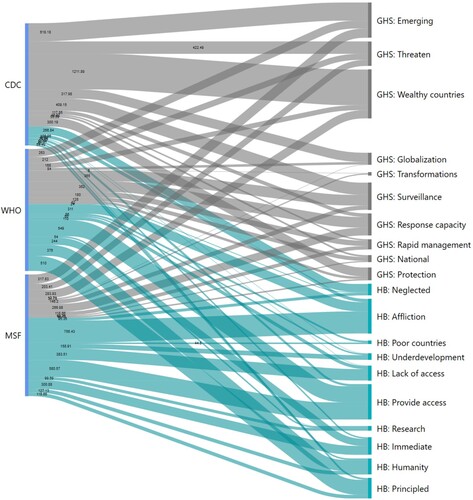

The content analysis affirmed the validity of the two regimes framework for analysing global health responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The coding exercise revealed the widespread and recurrent use of language associated with both global health security and humanitarian biomedicine by all organisations, albeit in different measure, and it found contrasting approaches to a shared global health issue. The Sankey diagram in presents all three organisations and all 20 categories in the two regimes of global health framework. This figure shows the flow rate for each organisation, specifically the relative emphasis they put on GHS (grey) and HB (turquoise) and the coding categories most frequently referenced in the first two years and two months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1. Organisational articulations of global health security (GHS) and humanitarian biomedicine (HB).

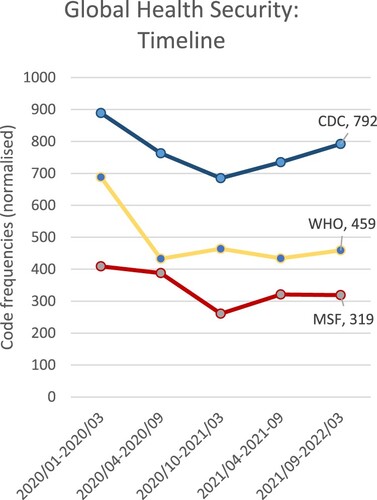

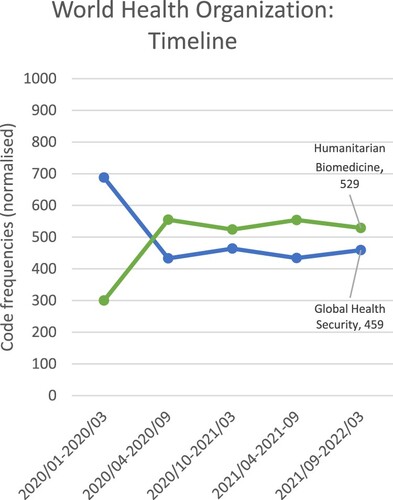

Three main findings are discussed in this section. First, the CDC and MSF largely aligned with the expectations of the two regimes framework, with the CDC consistently articulating priorities consistent with global health security and MSF humanitarian biomedicine. Second, and surprisingly, despite its reputation as a securitising actor, WHO public output actually balanced security with humanitarianism, with humanitarian concerns like equity and access among its most frequent codes. Third, and stemming from this, after the first two months of the pandemic, which featured the security-oriented PHEIC and pandemic declarations, the WHO’s language evolved: for the next two years, it favoured humanitarian priorities, which it linked to global health security – a formulation understood here as ‘global human health security.’

1. CDC and MSF: exemplars of the ‘two regimes’

The first finding is that the CDC and MSF largely conformed with the expectations of the two regimes framework, in the aggregate () and over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. The CDC primarily emphasised emerging disease threats to wealthy countries (especially, unsurprisingly, to Americans) and surveillance response strategies, while MSF – with exceptions discussed below – focused on neglected maladies afflicting the vulnerable, with access to treatments pinpointed both as a cause (lack of access) and appropriate response (provide access). The CDC’s ethic was self-protection while MSF’s was rooted in principles like equity, responsibility, and rights. Even as global circumstances evolved, with the spread of new variants and the development and distribution of vaccines, the overall framing remained remarkably consistent for both organisations.

The American CDC occupied one end of the GHS-HB spectrum; its public materials clearly and consistently prioritised global (and especially American) health security. Out of 122 possible codes, 8 of the CDC’s top 10 most frequent codes were for global health security – indeed, 18 of its top 20 codes were GHS. These codes included: ‘America,’ ‘Protect(ing/ed/ion),’ ‘United States/US/USA,’ ‘Travel,’ ‘Spread(ing),’ and ‘Threat(en/ened/ening).’ Beyond the formal coding exercise, basic word counts of CDC publications corroborate the impression of the CDC as a global health securitiser: in addition to ‘America’ and ‘United States,’ the CDC was the only organisation to have ‘risk’ and ‘safety’ among its most used words.

The CDC’s priorities were consistent throughout the pandemic and the tone was set in its earliest publications, including in this February 29, 2020 media statement announcing the first documented COVID-19 death in the US:

CDC is sending a team of experts to support the investigation in Washington. Dr. Messonnier said, ‘We recognize that this is a difficult time; we are facing a historic public health challenge. We will continue to respond to COVID-19 in an aggressive way to contain and blunt the threat of this virus. While we still hope for the best, we continue to prepare for this virus to become widespread in the United States.’ (CDC, Citation2020)

MSF was in many respects the mirror image of the CDC in its approach to COVID-19. 7 of its top 10 codes corresponded with humanitarian biomedicine, namely ‘Vulnerable,’ ‘Provi(de/sion),’ ‘(Lack of) access,’ ‘(Provide) access,’ ‘A need/needs,’ ‘Urgen(cy/t/tly),’ and ‘Suffer(ing).’ Here, too, word counts corroborate MSF’s priorities: its top 15 words included ‘people,’ ‘patients,’ ‘care,’ ‘staff,’ ‘support,’ and ‘access.’ Interestingly, MSF’s top code, ‘Protect(ing/ed/ion),’ was an apparent outlier – apparent because while protection language was coded for GHS, analysis of these quotes reveals striking differences in how MSF and the CDC used the word. Whereas the CDC sought to protect America and Americans, MSF directed its attention at vulnerable populations. As such, MSF’s referent object of security was more in line with human security, and thus with humanitarian ideals of emphasising the plight of the marginalised, than with traditional security (e.g. Newman, Citation2022). This discussion continues in Section III.3 in the context of the WHO’s similar human security orientation. In addition, MSF’s other two GHS codes can be read in ways consistent with humanitarianism: ‘Europe(an)/EU’ appeared frequently, but often as an observation or even a critique of EU border closures or lockdowns, and ‘Spread(ing)’ was an intensifier intended to galvanise action, much as humanitarianism by mandate responds to emergencies. Indeed, the ‘urgency’ HB code reflects humanitarianism’s roots in crisis response (e.g. Redfield, Citation2013, p. 13), compared to the GHS emphasis on preparedness (Lakoff, Citation2017, p. 71)

Nearly every MSF publication addressed the health needs of affected populations and advocated equity and access to alleviate pandemic-related suffering. For example, this project update appeared on March 23, 2020, the same month as the WHO’s pandemic declaration and as national border closures reached their peak (Kenwick & Simmons, Citation2020):

Healthcare systems, particularly those in low-resource settings, will be put under considerable pressure by the COVID-19 coronavirus. We know from previous epidemics that reduced access to care, medicines and diagnostics for people with life-threatening conditions, such as TB, can lead to an increase of deaths from these underlying conditions. (MSF, Citation2020)

In juxtaposing the CDC and MSF COVID-19 responses, the contrasts between global health regimes are evident. The CDC followed a health security model premised on surveillance and containment to protect wealthy states – here the United States – from emerging disease threats largely emanating from the global south (Lakoff, Citation2010, p. 59). MSF, as a humanitarian biomedical organisation, approached COVID-19 as an affliction affecting humanity across borders, with unequal suffering rooted in preexisting disease and development conditions (e.g. Redfield, Citation2013, p. 17). As seen in , whereas the CDC’s favoured intervention was surveillance, MSF emphasised access to medicines and treatments. These two cases support the two regimes framework, namely, as Lakoff (Citation2010, p. 59) observes, that: ‘different projects of global health imply starkly different understandings of the most salient threats facing global populations, of the relevant groups whose health should be protected, and of the appropriate justification for health interventions that transgress national sovereignty.’

2. The WHO balances security and humanitarianism

While the CDC and MSF COVID-19 responses closely matched theoretical expectations, with the two organisations positioned at opposite ends of the security-humanitarian spectrum, the WHO did not uniformly align with either regime. This was surprising. Typically, the WHO is understood to be a central player, even a leader, in global health security; its framing of COVID-19 would be expected to approximate that of the CDC in prioritising the containment of emerging disease threats. In fact, the WHO did regularly use codes associated with GHS and was the only organisation to use the term ‘global health security’ (albeit a mere 8 times in 238 documents). However, contrary to expectations and unlike the CDC, the WHO’s public statements balanced health security with humanitarian rhetoric – with a slight disposition towards humanitarian biomedicine.

As discussed in Section I, the WHO is the primary multilateral organisation involved in both global health, generally, and global health security, specifically. Lakoff (Citation2010, pp. 67–69) describes how the WHO’s 2007 report, ‘A Safer Future: Global Public Health Security in the twenty-first Century,’ proposed a strategic framework for global health security underpinned by surveillance, investigation, and containment, which was the realisation of two decades of work on emerging infectious diseases. As Kamradt-Scott (Citation2015, p. 3) notes, this threat-based framework has since become a ‘core theme of the WHO’s agenda’ and has been used to dramatically expand its responsibilities. These conclusions are amply supported by other research (e.g. Rushton, Citation2011; Youde, Citation2011), in particular by Davies (Citation2008, p. 308), who links the WHO’s very authority to its ability ‘to present itself as best placed to respond to the infectious disease threat’ – a move that, according to this perspective, has compromised its ability to fulfil its ‘health of all’ mandate. Legally, the WHO’s ability to decide on matters of global health security is provided by the revised 2005 IHR, which incorporate EIDs, authorise nongovernmental surveillance, and provide the basis for a declaration of a PHEIC (Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015, p. Ch. 4; Lakoff, Citation2010; Youde, Citation2011).

Before delving into the WHO’s surprisingly humanitarian orientation, it is important to acknowledge that the WHO did promote surveillance and containment of COVID-19, especially early on. This can be seen in , in which the WHO occupies the middle ground between the CDC and MSF on the surveillance/access spectrum. Across all WHO documents, 5 of the top 10 codes were GHS: ‘Protect(ing/ed/ion), ‘Preparedness,’ ‘Risk(y),’ ‘Surveillance,’ and ‘Nation(al).’ The WHO’s declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 20, 2020 exemplified a health security focus:

It is expected that further international exportation of cases may appear in any country. Thus, all countries should be prepared for containment, including active surveillance, early detection, isolation and case management, contact tracing and prevention of onward spread of 2019-nCoVinfection, and to share full data with WHO. (WHO, Citation2020c)

However, the WHO was not a pure or even primary voice for global health security. It consistently raised, and balanced security with, humanitarian concerns. Even the PHEIC, while largely supportive of health security and surveillance, also addressed the need for aiding vulnerable countries and ensuring access to diagnostics and treatments. The coding exercise provided ample evidence of this regime balancing act, aspects of which are also seen in . While 5 of the top 10 codes were GHS, the remainder were humanitarian biomedicine, including 4 of the top 5 codes: ‘(Provide) access,’ ‘Equit(y/able),’ ‘Solidarity,’ and ‘Urgen(cy/t/tly),’ with ‘Vulnerable’ completing the list. Furthermore, as discussed in the next subsection, while ‘Protect(ing/ed/ion) was coded for GHS, a code co-occurrence analysis demonstrates that wealthy state protection was not necessarily the WHO’s top priority. Overall, the picture is of a Janus-faced response to COVID-19, with seemingly contrasting ideas and approaches receiving significant attention from the WHO.

The WHO’s humanitarian face was clearly seen in its support of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A), a multistakeholder framework promoting access to and collaboration on vaccines (the COVAX initiative), diagnostics, therapeutics, and health systems. In announcing the initiative on April 24, 2020, the WHO (Citation2020b) stated:

‘Our shared commitment is to ensure all people have access to all the tools to prevent, detect, treat and defeat COVID-19,’ said [Director-General] Dr Tedros. ‘No country and no organization can do this alone. The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator brings together the combined power of several organizations to work with speed and scale.’

How are we to understand the WHO’s approach to COVID-19? The conclusions ask whether prior scholarship has understated the WHO’s humanitarian aspirations or whether COVID-19 signals changes in the organisation’s approach. Regardless, the recent pandemic should prompt a reconsideration of the organisation’s position in the two regimes framework, given the different ways the WHO framed COVID-19 compared to wealthy state agencies like the CDC. Indeed, the intergovernmental vs state dimension is likely a key explanatory factor. In their analysis of the West African Ebola outbreak, Harman and Wenham (Citation2018) emphasise the WHO’s security orientation, but they also observe that IGOs like the WHO are involved in humanitarian activities. Similarly, the WHO is part of a larger UN system that has voiced support for human security and whose United Nations Development Program even originated the concept (Newman, Citation2022). The WHO’s global role compared to the CDC’s national focus was seen in its keywords: its top 15 words included ‘countries’ (in the plural), ‘global,’ ‘world,’ and ‘international.’

3. The WHO evolves: global human health security

Following from the second finding, not only did the WHO balance security and humanitarianism, after the first two months – which saw COVID-19 go from outbreak to pandemic – it significantly increased its humanitarian language relative to global health security. Thus, for the vast majority of the two-year, two-month study period, the WHO’s priorities were humanitarian: concerns about unequal health impacts on the global south, differential access to PPE globally, and, later, vaccine nationalism. MSF voiced similar concerns. While traditional security language did not disappear, its frequency was reduced and it was generally linked to humanitarian concerns: inequities were framed as the primary cause of health insecurity. Rather than narrow-minded state self-protection exemplified by vaccine nationalism, the WHO articulated a vision of human health security rooted in global cooperation and equitable access. This subsection presents evidence to support these findings.

As has been demonstrated, the CDC consistently securitised COVID-19 and MSF humanised it. shows that the WHO initially gravitated towards the CDC’s pole in emphasising surveillance and containment strategies to address the emerging threat. After the first two months, however, the WHO’s security-oriented output sharply declined, leading to convergence with MSF. Moreover, as indicates, the WHO’s priorities flipped: the decline in GHS rhetoric corresponded with an increased humanitarian orientation.

In WHO publications, humanitarianism and health security co-existed and co-mingled; instead of two distinct regimes with opposing visions of health, the WHO approach causally linked humanitarian priorities, namely equity and access, to health security for all. Consider the strongly worded speech Director-General Tedros gave to the EU Political and Security Committee on October 1, 2021. Labelling vaccine nationalism ‘ethically abhorrent’ and ‘epidemiologically and economically self-defeating,’ he observed: ‘The longer vaccine inequity persists, the longer the social and economic turmoil will continue, and the more opportunity the virus has to circulate and change into more dangerous variants.’ He concluded by emphasising that ‘no country can vaccinate its way out of this pandemic in isolation from the rest of the world’ (WHO, Citation2021c). This was one of at least 8 separate speeches given by Tedros from March through November 2021 in which the ‘no country can vaccinate … ’ line was used.Footnote4 A similar tone was taken in Tedros’ WHO commentary promoting ‘health for all in 2022.’ He began by highlighting new treatments and potential increases in access and declines in mortality, then cautioned that ‘narrow nationalism and vaccine hoarding by some countries’ had fostered the emergence of the Omicron variant. Whereas inequity creates ‘higher risks’ of the virus evolving in unpredictable ways: ‘If we end inequity, we end the pandemic’ (WHO, Citation2021a).

In linking security to equity and access, and especially in critiquing ‘narrow nationalism,’ the WHO was articulating an alternate vision of health security, at least in comparison to the state- and border-centric COVID-19 responses undertaken by its chief state sponsors. Security, generally, and global health security, specifically, are contested concepts. As Rushton (Citation2011) asks: ‘Security for whom? Security from what?’ We might add: ‘Security how?’ According to Rushton (Citation2011, pp. 782–784), while the northern consensus has aligned on states (whom), infectious diseases (what), and containment (how) – a formulation mirroring the ‘global health security’ regime – the security concept is quite malleable. He highlights ‘human security’ as an alternative: its referent object is the individual or community (whom), it recognises a broader range of chronic health threats (what), and it promotes actions to address root conditions like poverty and inequality (how).

An examination of key GHS codes revealed important differences in how the WHO approached security compared to the CDC’s traditional security approach. Specifically, a code co-occurrence analysis allowed researchers to determine which codes frequently appeared in the same recording segments. These were some of the findings:

‘Threat’: While CDC quotes highlighted COVID-19’s threat to the US, the WHO emphasised solidarity against a common threat and the insufficiency of single government responses. MSF foregrounded the threat to people (e.g. in crowded refugee camps).

‘Borders’: The CDC promoted its border controls, a clear contrast with both the WHO and MSF, which were more likely to criticise the impact of restrictions on human survival and wellbeing. In addition, despite the IHR being understood as a tool for GHS (e.g. Lakoff, Citation2010; Rushton, Citation2011), the WHO’s frequent IHR references were intended to constrain state border security practices by reminding states to report activities to the WHO and by highlighting economic harm, e.g. to workers.

‘Security’: Security was coded narrowly, in ways consistent with GHS, but the research also noted numerous occasions when the word diverged from statist notions of security; most of these came from the WHO. For instance, the WHO referenced ‘food (in)security’ 15 times (compared to 2x each for the CDC and MSF), to foreground the consequences both of the pandemic and of stringent lockdown responses.

The ‘Protect(ing/ed/ion)’ code was also analysed for code co-occurrences to determine the referent of protection – ‘security for whom,’ in the formulation above. Protection was frequently referenced (772 times) and the usage varied by organisation. For the CDC, the referent was overwhelmingly ‘America(ns)’ (52%), followed by ‘people’ in general (16%) and ‘vulnerable groups’Footnote5 (10%). For the WHO, the referent of protection was ‘vulnerable groups’ (28%), followed by ‘people’ (22%) and ‘the world/everyone’ (21%). The WHO also frequently referenced ‘health systems’ and ‘health workers’ (9% each). Like the WHO, MSF prioritised the vulnerable, then health workers and patients – as befits a medical organisation. The WHO approach is captured by one of its COVAX-related news releases: ‘The power of our humanity and the success of COVAX will be measured by how we collectively protect the most vulnerable among us’ (WHO, Citation2020a). In this human security formulation, our very humanity hinges on the collective protection of the vulnerable through equitable vaccine access.

The WHO case demonstrates that, at least in certain instances or for certain actors, the divide between global health security and humanitarian biomedicine is not necessarily insurmountable. Indeed, much as Harman and Wenham (Citation2018) found in their analysis of the West African Ebola outbreak, there is considerable co-dependence among actors with different approaches to the ‘who’ and ‘what’ of global health. In the West Africa case, the primary division was between the WHO (secure states against infectious disease) and MSF (treat individuals for current suffering). With COVID-19, these different approaches played out in the WHO itself, ultimately resolving in a formulation of global human health security that prescribed equity and access as the pathways to global disease protection.

Conclusions

This research analysed the values and priorities of global health actors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing on Lakoff (Citation2010, Citation2017)’s two regimes of global health framework, it investigated whether the security versus access divide characterised the recent response and how global health frames evolved over the course of the pandemic. Evidence consisted of a content analysis of a census sample of 486 publications from three focus organisations, with the US CDC and the WHO as exemplars of the global health security regime and MSF typifying humanitarian biomedicine. 122 codes in 20 categories were applied to these organisations.

Three main findings were presented. First, the content analysis strongly supported the two regimes premise – key global health actors vary in their principles and approaches – with the CDC and MSF occupying opposite ends of the security-access spectrum. Second, despite a wealth of prior research establishing the WHO as an influential global health securitiser, the WHO framed its COVID-19 priorities in ways that defied easy or automatic categorisation. While containment and surveillance played a role in the WHO’s public output, the content analysis demonstrated that the IGO balanced health security and humanitarian biomedicine, with a slight tilt in favour of humanitarianism. Third, the WHO’s framing of COVID-19 evolved after the initial phase of the pandemic, when the PHEIC threat containment model gave way to concerns about equity and access. While security did not disappear, this language was linked to the plight of the vulnerable and to a critique of statist security orientations manifesting in border controls and vaccine nationalism.

The statist security critique and the WHO’s own security vision are the first of three implications raised in these conclusions. According to Newman (Citation2022), while the traditional security paradigm guided most government responses, the pandemic exposed the inability of these approaches to guarantee resilience or protection. Newman (Citation2022, p. 431) favours a human security framework for its attention to the structural inequalities and contradictions in statist approaches, noting that for those in disadvantaged circumstances, COVID-19 was a reminder that ‘challenges such as preventable disease, pollution, malnutrition and extreme poverty are the primary existential threats, and far more so than threats associated with the traditional security paradigm.’ As discussed in Section III.3, the WHO embraced many of the priorities outlined by Newman (Citation2022, p. 437), including attention to existing diseases (e.g. malaria), structural inequalities, the vulnerability of frontline workers, and economic security and survival. It emerged as a vocal critic of traditional security approaches. As stated by Dr. Tedros in a WHO news release:

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the many flaws in the global system to protect people from pandemics: the most vulnerable people going without vaccines; health workers without needed equipment to perform their life-saving work; and ‘me-first’ approaches that stymie the global solidarity needed to deal with a global threat. (WHO, Citation2021d)

Second, how new is this WHO equity and access orientation? Though the WHO’s COVID-19 response ran counter to theoretical expectations, prior research has not systematically analysed the public statements of key health organisations – the content analysis approach pursued here makes this contribution to the literature.Footnote6 Nonetheless, some previous scholarship does support the hypothesis that the WHO’s recent activities amplify existing trends: for instance, Davies (Citation2008) notes the WHO’s use of the word ‘solidarity’ linked to common threats, while Jackson and Stephenson (Citation2014) connect the ‘neglected tropical diseases’ movement to concerns about underdevelopment and instability. Kamradt-Scott (Citation2015, pp. 159–164) explains that while the ‘health as security’ frame was driven by wealthy WHO member states, southern state pushback since 2011 has contributed to shifts in WHO discourse and priorities. While security remains a concern (and the IHR are untouched), greater emphasis has been placed on health systems, chronic diseases, and maternal and child health. Comparative analysis of prior health responses is needed to determine the extent to which humanitarian frames have previously featured in WHO public statements, for instance during its responses to Zika, Ebola, or SARS, and whether they increased in priority over time, as characterised the WHO’s COVID-19 response.

Finally, how enduring are these rhetorical shifts? The current WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros, arrived in Geneva with a background promoting equitable access in Ethiopia and connecting health to development. Even prior to COVID-19, he sought to align the WHO with the Sustainable Development Goals and coined a new WHO mission statement: ‘Promote health, keep the world safe and serve the vulnerable’ (WHO, Citation2023). This framing aligns with the WHO’s COVID-19 response in linking the health of all to the security of all. But the WHO is not a unitary actor; the secretariat serves the often divergent needs of almost 200 ‘masters,’ to borrow Kamradt-Scott (Citation2015, p. 186)’s phrasing, and it does so with a budget largely consisting of voluntary contributions. It derives authority from its expertise and its commitment to shared values and scholarship suggests that it has made strategic efforts to reframe its mandate (e.g. Davies, Citation2008; Johnson, Citation2020; Kahl & Wright, Citation2021; Kamradt-Scott, Citation2015). However, as Johnson (Citation2020) explains, ‘out of touch’ experts are readily blamed by states, which themselves consistently prioritise narrow interests.

During COVID-19, we saw this play out with COVAX (Section III), an ambitious WHO-sponsored vaccine sharing initiative that struggled to secure doses and funding as wealthy states prioritised boosters for their citizens over vaccines for non-citizens (Bajaj et al., Citation2022). Even with an uptick in COVAX shipments by the end of 2021, Bajaj et al. (Citation2022, p. 1452) suggest that ‘[a]ddressing the root causes of vaccine inequity will require more systemic changes’ than philanthropy – changes like intellectual property waivers that support enduring solutions. Unfortunately, according to advocates, the 2022 passage of a World Trade Organization temporary IP waiver on COVID-19 vaccines privileges the interests of powerful states; it likely does not provide the platform for long-term, structural change (Green, Citation2022). The human tragedy of COVID-19 continues to play out in a statist security world, even if the rhetoric of global health officials has started to evolve.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from the research assistance of Eliza Caldwell and Kevin Hamilton and from the financial support of the Holy Cross J.D. Power Center Research Associates Program and a Committee on Faculty Scholarship Publication Grant. This paper was presented at the 2022 British International Studies Association conference in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK and at the 2022 International Studies Association-Northeast conference in Baltimore, MD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Namely, MSF’s ‘voices from the field’ and ‘reports’ categories (20 documents, total) and the larger WHO ‘speeches’ category, discussed in fn4.

2 Normalisation creates consistency across records, here across document groups. For example, because the WHO had twice as many documents as the CDC, absolute numbers would be misleading. To facilitate comparison, ATLAS.ti increases the relative weight of the CDC’s documents.

3 The RAs were 91.3% in agreement – per Drisko and Maschi (Citation2016, p. 47), 80%+ is a high level of agreement – and the Krippendorff’s alpha was .955.

4 Speeches were ultimately dropped from the content analysis for lack of parity. Specifically, the WHO published 465 speeches during the study period compared to 2 for MSF and 0 for the CDC. Commentaries were included.

5 ‘Vulnerable groups’ included those identified as such and specific named groups, e.g. ‘children,’ ‘refugees,’ and ‘the elderly.’

6 A partial exception is Kirk (Citation2020), who analysed the Obama administration’s Ebola discourse.

References

- Bajaj, S. S., Maki, L., & Stanford, F. C. (2022). Vaccine apartheid: Global cooperation and equity. The Lancet, 399(10334), 1452–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00328-2

- Brown, H. (2015). Global health partnerships, governance, and sovereign responsibility in western Kenya. American Ethnologist, 42(2), 340–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12134

- Calain, P. (2012). In search of the ‘new informal legitimacy’of Médecins Sans Frontières. Public Health Ethics, 5(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phr036

- CDC. (2020, February 29). CDC, Washington State Report First COVID-19 Death. Retrieved February 20 from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/s0229-COVID-19-first-death.html.

- Davies, S. E. (2008). Securitizing infectious disease. International Affairs, 84(2), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00704.x

- De Waal, A. (2021). New pandemics, Old politics: Two hundred years of war on disease and its alternatives. John Wiley & Sons.

- Drisko, J. W., & Maschi, T. (2016). Content analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Fidler, D. P. (2010). The challenges of global health governance (Working Paper). Council on Foreign Relations.

- Green, A. (2022, June 17). WTO finally agrees on a TRIPS deal. But not everyone is happy. Devex. https://www.devex.com/news/wto-finally-agrees-on-a-trips-deal-but-not-everyone-is-happy-103476.

- Greer, S. L., King, E., Massard da Fonseca, E., & Peralta-Santos, A. (2021). Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press.

- Harman, S., & Wenham, C. (2018). Governing Ebola: Between global health and medical humanitarianism. Globalizations, 15(3), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2017.1414410

- Jackson, Y., & Stephenson, N. (2014). Neglected tropical disease and emerging infectious disease: An analysis of the history, promise and constraints of two worldviews. Global Public Health, 9(9), 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.941297

- Johnson, T. (2020). Ordinary patterns in an extraordinary crisis: How international relations makes sense of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Organization, 74(S1), E148–E168. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000430

- Kahl, C., & Wright, T. (2021). Aftershocks: Pandemic politics and the end of the old international order. St. Martin's Press.

- Kamradt-Scott, A. (2015). Managing global health security: The world health organization and disease outbreak control. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kennedy, E. D., Morgan, J., & Knight, N. W. (2018). Global health security implementation: Expanding the evidence base. Health Security, 16(S1), S1–S4. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2018.0120

- Kenwick, M. R., & Simmons, B. A. (2020). Pandemic response as border politics. International Organization, 74(S1), E36–E58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000363

- Kirk, J. (2020). From threat to risk? Exceptionalism and logics of health security. International Studies Quarterly, 64(2), 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqaa021

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). SAGE Publishing.

- Lakoff, A. (2010). Two regimes of global health. Humanity: An international journal of human rights. Humanitarianism, and Development, 1(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1353/hum.2010.0001

- Lakoff, A. (2017). Unprepared: Global health in a time of emergency. University of California Press.

- MSF. (2020, March 23). COVID-19: Avoiding a ‘second tragedy’ for those with TB. Médecins Sans Frontières. https://www.msf.org/covid-19-how-avoid-second-tragedy-those-tuberculosis.

- Newman, E. (2022). COVID-19: A human security analysis. Global Society, 36(4), 431–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2021.2010034

- O'Laughlin, B. (2016). Pragmatism, structural reform and the politics of inequality in global public health. Development and Change, 47(4), 686–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12251

- Patrick, S. (2020). When the system fails. Foreign Affairs, 99(4), 40–50.

- Redfield, P. (2013). Life in crisis: The ethical journey of doctors without borders. University of California Press.

- Rushton, S. (2011). Global health security: Security for whom? Security from what? Political Studies, 59(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00919.x

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Shiffman, J., & Shawar, Y. R. (2022). Framing and the formation of global health priorities. The Lancet, 399(10339), 1977–1990. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00584-0

- Snowden, F. M. (2019). Epidemics and society: From the black death to the present. Yale University Press.

- WHO. (2008). International health regulations (2005) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization.

- WHO. (2020a, September 21). Boost for global response to COVID-19 as economies worldwide formally sign up to COVAX facility. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/21-09-2020-boost-for-global-response-to-covid-19-as-economies-worldwide-formally-sign-up-to-covax-facility.

- WHO. (2020b, April 24). Global leaders unite to ensure everyone everywhere can access new vaccines, tests and treatments for COVID-19. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/24-04-2020-global-leaders-unite-to-ensure-everyone-everywhere-can-access-new-vaccines-tests-and-treatments-for-covid-19.

- WHO. (2020c, January 30). Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- WHO. (2021a, December 30). 2021 has been tumultuous but we know how to end the pandemic and promote health for all in 2022. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/2021-has-been-tumultuous-but-we-know-how-to-end-the-pandemic-and-promote-health-for-all-in-2022.

- WHO. (2021b, March 30). COVID-19 shows why united action is needed for more robust international health architecture. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/op-ed—covid-19-shows-why-united-action-is-needed-for-more-robust-international-health-architecture.

- WHO. (2021c, October 21). Speech for closed session - Meeting with the Ambassadors and Representatives to the EU Political and Security Committee. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/speech-for-closed-session—meeting-with-the-ambassadors-and-representatives-to-the-eu-political-and-security-committee.

- WHO. (2021d, December 1). World Health Assembly agrees to launch process to develop historic global accord on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-12-2021-world-health-assembly-agrees-to-launch-process-to-develop-historic-global-accord-on-pandemic-prevention-preparedness-and-response.

- WHO. (2022, May 5). 14.9 million excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2022-14.9-million-excess-deaths-were-associated-with-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-2020-and-2021.

- WHO. (2023, January 3). Biography: Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. World Health Organization. Retrieved January 3, 2023, from https://www.who.int/director-general/biography.

- Youde, J. (2011). Mediating risk through the international health regulations and bio-political surveillance. Political Studies, 59(4), 813–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00918.x

- Youde, J. (2017). Global health governance in international society. Global Governance, 23(4), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02304005