ABSTRACT

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals call for both the elimination of violence against women and girls and disability-disaggregated data. However, few population-based, multi-country studies have examined how disability impacts intimate partner violence (IPV) in fragile settings. Demographic and Health Survey data from five countries (Pakistan, Timor-Leste, Mali, Uganda, and Haiti) were pooled and analyzed to assess the relationship between disability and IPV (N = 22,984). Pooled analysis revealed an overall disability prevalence of 18.45%, with 42.35% lifetime IPV (physical, sexual and/or emotional), and 31.43% past-year IPV. Women with disabilities reported higher levels of past-year and lifetime IPV compared to those without disabilities (AOR 1.18; 95% CI 1.07, 1.30; AOR 1.31; 95% CI 1.19, 1.44, respectively). Women and girls with disabilities may be disproportionately impacted by IPV in fragile settings. More global attention is needed to address IPV and disability in these settings.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive public health concern and human rights violation. Global data indicate that nearly one in four women aged 15–49 years report experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2021). The public health impacts of IPV have been extensively documented and include poor mental health, negative maternal and child health outcomes, increased risk of sexually transmitted infections (including HIV/AIDS), injury, and death (WHO, Citation2013). A recently completed systematic review of IPV and disability found that disabled women are more likely to experience multiple forms of IPV (e.g. physical, sexual, financial) than non-disabled women (García-Cuéllar et al., Citation2022). Notably, of the 26 studies included in the systematic review, most were conducted in the United States and other Higher Income Countries.

As the research on IPV and disability continues to grow, it is critical for such research to also focus on populations from the Global South, including settings impacted by crisis (e.g. natural disaster, conflict, injustice, weak infrastructure). Research indicates that IPV is higher in such settings (Black et al., Citation2019; Kelly et al., Citation2018; Scolese et al., Citation2020). Drivers of such violence include women’s separation from family, destabilised gender norms and roles, rapid re-marriages and forced marriages, and men’s substance abuse (Wachter et al., Citation2018). Disabled women in such settings may face additional vulnerabilities to experiencing IPV, such as social stigma against disability, lack of social support and isolation, dependence upon partners/partners’ family members for finances and caretaking, and being seen as deviating from what male partners/partners’ family members expect from wives (Dunkle et al., Citation2018; Marshall & Barrett, Citation2018; Nosek et al., Citation2001) Women who are living with disabilities in such settings may also be particularly vulnerable to the negative health and social impacts of IPV due to increased social isolation and stigma against both IPV and disability (WHO, Citation2011). Moreover, very few IPV support services and preventive interventions exist in such settings that are tailored specifically for women living with disabilities (Marshall & Barrett, Citation2018).

A recent pooled analysis of baseline data from five countries (Afghanistan, Rwanda, Nepal, Ghana, South Africa) that are part of an IPV prevention trial consortium found that women with disabilities were 1.93 times more likely to report past-year disability in comparison to counterparts without disability (Chirwa et al., Citation2020). Country-specific household and/or community-based surveys conducted in Nepal (Gupta et al., Citation2018), Uganda (Valentine et al., Citation2019), the Democratic Republic of Congo (Scolese et al., Citation2020), and among Somali refugees in Kenya have yielded similar findings (Hossain et al., Citation2020). However, participants in these surveys had to meet specific trial inclusion criteria and/or are primarily focused on countries within Africa and South Asia. Thus underscoring the importance of additional research with broader samples.

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals call for both the elimination of violence against women and girls and disability-disaggregated data (Browne, Citation2017). Thus, there is a need for multi-country data on disability and IPV across multiple regions that are impacted by crisis and fragility. This is particularly critical as 15% of the population across the globe is living with a disability, and 80% are in low and middle-income countries (WHO, Citation2011). Countries impacted by crisis and fragility may be more likely to be characterised by high levels of disability (WHO, Citation2011). In 2016 the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) Program began implementing a standardised disability module, thus enabling cross-national comparisons using standardised definitions and measurements (The Demographic and Health Surveys Program [DHS], Citation2017). This current study is a secondary analysis of data from five countries to examine the association between IPV and disability in fragile countries.

Methods

Study design

This cross-sectional, secondary data analysis is based on multi-country data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Funded by US Agency for International Development (USAID), DHS is a worldwide program that collects, analyzes, and disseminates nationally representative health data from over 90 low and middle-income countries (DHS, Citationn.d.-c). The DHS data sampling differs slightly between countries. Generally, data is sampled through a two-stage household-based sampling method. Clusters of households (the primary sampling unit, PSU) are first identified first based on a given sampling frame, usually the most recent census. The clusters are then stratified based on demographic variables as necessary (typically rural/urban and graphical region). Within each stratum, clusters are randomly selected with probability proportional to population size whenever possible; oversampling and under-sampling are conducted with weighting to maintain the validity of the sample. Afterward, a household listing is created for each chosen cluster including all households in the cluster. Between 20 and 30 households are randomly selected within each cluster in the central office to minimise selection biases. A survey team is then sent to the households to conduct face-to-face surveys. All households are administered a Household Questionnaire (typically answered by one respondent per household, for all individuals in the household) and are used to identify members eligible for individual surveys. Depending on the country, eligible women and men aged 15–49 are interviewed with the Women’s Questionnaire and Men’s Questionnaire, respectively (ICF International, Citation2012).

For the purpose of this study, we focus on the disability module in the Household Questionnaire and the domestic violence module included in the individual Women’s questionnaire. Both disability and domestic violence modules are optional, meaning not all countries include them in their DHS surveys. The questions in the modules can be customised and varied from the standard module depending on each country.

Countries were included in this study if they: (1) included the disability module, (2) included the domestic violence module, and (3) were classified as fragile or extremely fragile by the OECD in the corresponding year of available DHS (OECD, Citation2016, Citation2018). Out of the publicly available standard DHS datasets, 20 countries had at least one dataset including both the disability and domestic violence modules. The most recent DHS dataset including both modules was used for each country. Each country was cross-referenced with the OECD’s list of fragility for the corresponding survey year (OECD, Citation2016, Citation2018). Nine countries were excluded; only those classified as fragile or extremely fragile remained (11 countries). The OECD measures fragility across a spectrum of five dimensions including economic, environmental, political, security, and societal. Dimensions are assessed individually via indicators and mixed-method approaches are then used to aggregate data to produce an overall measure of fragility (OECD, Citation2020). Six countries were further excluded for custom modules that are not comparable to the standard modules. Data from 5 countries (Pakistan, Timor-Leste, Mali, Uganda, and Haiti) were included in the current study (). This protocol was declared exempt by George Mason University’s Human Subjects Committee, protocol #1768346-1.

Table 1. Fragile country context.

Sample

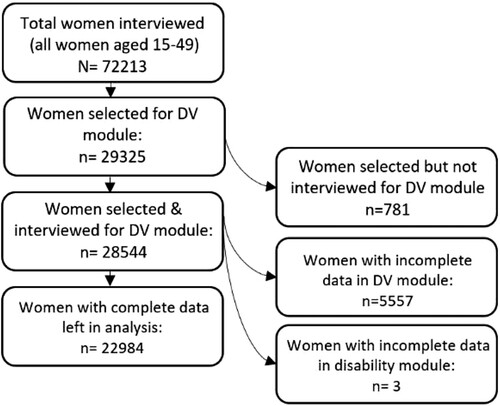

Across all countries included in the present analysis, a total of 72,213 ever-married and/or cohabiting women aged 15–49 were interviewed for the DHS. A total of 28,544 women were randomly selected and completed the domestic violence module. Listwise deletion was performed on women with missing values in either the domestic violence module or disability module. A total of 22,984 women with complete data were left in analysis (see ).

The IPV questions included in a domestic violence module were only used to survey ever-married (including ever-cohabitated) women aged 15–49. The domestic violence module is administered in accordance to the World Health Organization’s guidelines for conducting research on violence against women (DHS, Citationn.d.-b.; WHO, Citation2001). In a household that is selected for the module, only one eligible woman is randomly selected for the domestic violence module (DHS, Citationn.d.-b). Informed consent is acquired from all participants and interviews are conducted in a private space (DHS, Citationn.d.-b). Selected participants are informed that no one else in the household will be completing the same domestic violence module (DHS, Citationn.d.-b). Female interviewers were trained to skip or stop the module immediately if privacy was interrupted or not available (DHS, Citationn.d.-b). Questionnaires were administered in several languages per country as follows: more than 8 languages in Pakistan (e.g. English, Urdu, Sindhi, Punjabi); more than 10 languages in Uganda (e.g. English, Luganda, Lusoga); more than 11 languages in Mali (e.g. French, Bambara/Malinke, Sonrai/Djerma); two languages in Haiti (e.g. French, Creole); and more than 5 languages in Timor-Leste (e.g. English, Tetum, Bahasa).

Measures

Disability

The disability module includes the Washington Group on Disability Statistics’ Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) questions (The Washington Group on Disability Statistics, Citation2020b). The WG-SS are robust disability measures that have been validated in all regions of the world (Groce & Mont, Citation2017). Disability is assessed by eight items measuring difficulties an individual may experience while engaging in activities due to functional limitations related to seeing; hearing; communicating; remembering/concentrating; walking or climbing steps; and washing or dressing. Level of difficulty was captured through a Likert-type scale. For each item, participants can select from ‘No difficulty’, ‘Some difficulty’, ‘A lot of difficulty’, ‘Cannot at all’, and ‘Don’t know’. A dichotomous disability measure was adapted from the WG on Disability Statistics analytical guidelines (The Washington Group on Disability Statistics, Citation2020a). Responses were dichotomised as follows: women who reported ‘Some difficulty’, ‘A lot of difficulty’, and ‘Cannot at all’ to any of the items were categorised as having a disability, while those who reported ‘No difficulty’ to all items are categorised as not having a disability. Women who reported ‘Don’t know’ to any items were recoded as missing and the participant was excluded from further analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha of the disability questions as a scale ranged from 0.34 to 0.58 in our sample.

Any lifetime and any past-year IPV

The domestic violence module includes questions based on a modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scales (Straus et al., Citation1996). A female participant is asked if her male partner ever perpetrated specific acts of different forms of IPV (e.g. physical, sexual, emotional). A total of 13 items were used to assess experiences of IPV. Physical IPV was captured through 7 items (e.g. if the partner ever pushed, shook or threw something at her, slapped her, punched her with his fist or something that could hurt her, kicked, dragged, or beat her, tried to choke or burn her, threatened or attacked her with a knife, gun, or other weapon, twisted her arm or pulled her hair). Sexual (e.g. if the partner ever physically forced her to have sexual intercourse with him when she did not want to, physically force her to perform any other sexual acts she did not want to, force her with threats or in any other way to perform sexual acts she did not want to) and emotional IPV via 3 items (e.g. if the partner ever said or did something in front of others to humiliate her, threatened to hurt or harm someone she cares about, insulted or made her feel bad about herself), respectively. Participants who reported experiencing at least one act of any form of IPV were categorised as having experienced any IPV, while those who reported none of these acts are categorised as not experienced IPV. For each item they were asked to report a frequency. Response options include ‘no-never’, ‘yes-often’, ‘yes-sometimes’, ‘yes-but frequency in last 12 months missing’, and ‘yes-but not in last 12 months’ and were categorised into two dichotomous IPV variables. Those who reported experiencing any act of IPV ‘yes-often’, ‘yes-sometimes’, and ‘yes-but frequency in last 12 months missing’ are categorised as having experienced any IPV in the last 12 months, others are categorised as not experienced any IPV in the last 12 months. Similarly, participants who reported any frequency of experiencing any act IPV act other than ‘no-never’ were categorised as experienced any lifetime IPV, and participants who reported only ‘never’ are categorised as never experienced any IPV. Country-specific Cronbach’s alphas for the IPV measures ranged from 0.40-0.68 in our sample.

Sociodemographic variables

Based on previous studies among women with disabilities and in fragile settings (Gupta et al., Citation2014; Scolese et al., Citation2020; Valentine et al., Citation2019), individual and household characteristics are selected as covariates, including women’s age (<25 years, 25–35 years, 35+ years), education (no formal, primary, secondary, higher than secondary), employment status (employed, unemployed), number of children (none, 1–3, 4+), union status (married/cohabiting, divorced/separated/widowed), household location (rural, urban), and household wealth index (richest, richer, middle, poorer, poorest).

Analysis

The distribution of covariates was reported by disability and IPV variables. Multiple logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between disability and IPV variables (experienced IPV in the last 12 months and lifetime IPV). For both any lifetime IPV and past year IPV, crude and adjusted odds ratios are presented for the overall pooled analysis. The adjusted model accounted for age, women’s education, employment status, number of children, union status, location, and household wealth. To preserve power, age and number of children were used as continuous variables, and household wealth index and marital status were dichotomised. All analyses were completed using RStudio software (RStudio Team, Citation2021). The survey package was used to account for the survey design and weight (Lumley, Citation2021). This study used the weight specifically applied to the domestic violence module (d005), which included questions regarding IPV. This weight accounted for the over-sampling, under-sampling, and non-response rate during the data collection period so that the weighted data would be representative of the country. Listwise deletion was applied to participants with missing data on the IPV or disability items. The weights in each country were then rescaled by dividing each weight by the sum of the weights in the country so that the sum of new weights in each country equals one. All five countries were pooled into one analysis dataset, with the same representation in the weighted analysis for each country (Pullum, Citation2013).

Results

Overall, the prevalence of disability across the five countries included in this current study was 18.45%. The prevalence of lifetime IPV across the five countries was 42.35%, and the overall prevalence of past-year IPV was 31.43%. The distributions of disability, lifetime IPV, and past-year IPV and sociodemographic covariates of interest are detailed in .

Table 2. Weighted bivariate associations between socio-demographic covariates and disability, and intimate partner violence (IPV) (N = 5000).

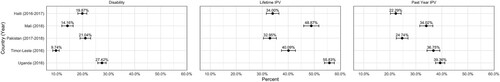

In , we present the weighted prevalence of disability, lifetime IPV, and past-year IPV in each of the five countries included in the study. We found that the prevalence of disability ranged from 9.75% in Timor-Leste to 27.42% in Uganda. For lifetime IPV, the prevalence ranged from 32.95% in Pakistan to 55.83% in Uganda. Regarding past-year IPV, prevalence ranged from 22.29% in Haiti to 39.36% in Uganda.

Figure 2. Weighted distribution of disability, lifetime and, past-year IPV by country (N = 5000). Note: All countries were rescaled so that the sum of new weights in each country equals one. Each country had the same weighted representation (n’s = 1000).

shows the outcome of the pooled Logistic regression analyses. In the unadjusted model for lifetime IPV, women who reported disability had a 1.4 higher likelihood of reporting lifetime IPV in comparison to counterparts who did not report disability (OR 1.4; 95% CI 1.28, 1.54). In the adjusted model, the association remained significant (AOR 1.31; 95% CI 1.19, 1.44). In the unadjusted model for past-year IPV, women who reported disability had a 1.13 higher likelihood of reporting past-year IPV in comparison to counterparts who did not report disability (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02, 1.24). In the adjusted model, the association remained significant (AOR 1.18; 95% CI 1.07,1.30).

Table 3. Weighted unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression for disability and lifetime and past-year intimate partner violence (IPV) (N = 5000).

Unweighted pooled and country-specific estimates are detailed in Supplemental Tables 1–4.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis of multi-country nationally representative data from five fragile states, we found that overall, women who reported a disability were 1.31 times more likely to report physical, sexual and/or emotional IPV in their lifetime, and 1.18 times more likely to report past-year IPV. Current study findings underscore the importance of considering disability as a driver of IPV in settings in the Global South impacted by crises, including conflict, natural disasters, injustice, or weak economic infrastructure.

Study findings reported herein are consistent with the small but growing number of studies examining associations between disability and IPV in the Global South (Gupta et al., Citation2018; Hossain et al., Citation2020; Scolese et al., Citation2020; Valentine et al., Citation2019). There has been only one other multi-country study examining disability and IPV focusing on populations in the Global South which focused on data from a cohort of randomised controlled intervention trials to reduce IPV (Chirwa et al., Citation2020). The current findings are consistent with this work and extend the findings to include analyses drawn from nationally representative data. Moreover, our multi-country analysis of disability and IPV addresses an important component of the 2030 Agenda for Change which calls for the disaggregation of data by disability as part of a broader goal to ensure that ‘no one is left behind’ (Browne, Citation2017). Current study findings also provide further evidence of the need to develop more inclusive IPV prevention and response programming to address the needs of disabled women.

As accumulating data underscore the need for more IPV prevention and response programming and policies that explicitly address the needs of disabled women, more research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms that place disabled women at greater vulnerability for experiencing IPV. Disability-related stigma and discrimination, in addition to a lack of socially inclusive services, may contribute to the social exclusion and isolation experienced by disabled women (Dunkle et al., Citation2018; Marshall & Barrett, Citation2018). This social exclusion and isolation, in the absence of broader support systems, can further increase disabled women’s dependence on their partner/spouse for caretaking and finances and can increase their vulnerability to IPV (Dunkle et al., Citation2018; Nosek et al., Citation2001). All these factors may be exacerbated in fragile settings. Additionally, women and girls with disabilities may be perceived to not or may not be able to fulfill expectations of gendered household/wifely roles, further increasing vulnerability to IPV (Dunkle et al., Citation2018). There may be additional context-specific factors in fragile settings, underscoring the importance of researching the underlying mechanisms which place women and girls with disabilities at greater vulnerability to IPV. Future research should also include development of measures for disability-associated social norms to inform interventions and policy. This may include measures to assess ableism and disability indexes. Such measures are needed to move both the disability and IPV fields forward.

There are study limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of these data, causality cannot be ascertained. It may be that IPV preceded becoming disabled. Additionally, disability may be under-reported. The DHS includes the disability module within the household questionnaire, which is often administered to one household member (DHS, Citationn.d.-a). It may be possible that the respondent for the household survey is not fully aware of others’ disabilities and associated impacts. Therefore, the DHS posits that respondents may only disclose a household member’s disability if the disability is severe as evidenced by the higher percentages of severe disabilities reported compared to other severity categories (DHS, Citationn.d.-a). Severe disability may still be underreported, as accessibility may impact those with severe disabilities from engaging in the study should they be the only eligible household member. While the WG-SS have been widely tested and validated, it has been noted to not capture mental impairments, thus potentially limiting the assessment of a fuller spectrum of disability (Groce & Mont, Citation2017). Regarding IPV, despite efforts from the DHS surveyors to establish rapport and ensure confidentiality (DHS, Citationn.d.-b), under-reporting may still occur (DHS, Citationn.d.-a). We also did not examine the types of disability or forms of IPV separately due to limited statistical power. Future research is needed to examine whether vulnerability to IPV varies by disability type and severity. Our dataset was also restricted to five countries due to our inclusion criteria; thus more research with additional countries is needed. Lastly, there may be other important covariates of interest to examine within the context of fragile settings that are not contained within the DHS. It would be important for future research to examine a fuller set of factors that may influence these associations, including social context and norms surrounding disability and ableism, and how that may be associated with male-perpetrated IPV against women and girls.

These limitations notwithstanding, our study has critical implications for future research on IPV prevention and programming in fragile states. IPV intervention research in fragile settings has rapidly grown in recent years, with promising models for prevention (Ellsberg et al., Citation2015). Less intervention research has focused on preventing IPV against disabled women. The current study underscores the importance of conducting such research. Recent findings from a post-hoc analysis examining intervention impacts from three randomised controlled trials of IPV interventions in Afghanistan, Rwanda, and South Africa suggest that disabled and non-disabled women had similar outcomes regarding IPV reductions and/or no reductions (Dunkle et al., Citation2020). Future IPV intervention studies would benefit from such disaggregated analysis based on disability, as well as adequate power to examine potential treatment heterogeneity of IPV interventions targeting individuals, couples, communities, and/or policy.

Research in partnership with disability communities is also needed to inform the development of inclusive IPV interventions, both in community settings as well as health care facilities. Such partnerships are particularly needed to ensure that disabled women are able to access such interventions, regardless of form and/or severity of disability. Qualitative findings from the aforementioned trials highlight barriers to intervention participation, including physical barriers, overt stigma and discrimination, and internalised stigma (Stern et al., Citation2020). Such work is critically important, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate burden in the Global South and the risk of long covid (Chen et al., Citation2022). Long Covid can be disabling and disproportionately impacts women, and thus may also increase vulnerability to IPV (Chen et al., Citation2022). Future research is needed in this area.

Conclusion

Global IPV is an egregious public health problem, and women with disabilities may be disproportionately impacted. More global attention is needed to address IPV and disability to allow women and their communities to live free of violence.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Most DHS datasets are publicly available and can be downloaded with approval from the DHS. Per the DHS, we are unable to share datasets without permission from DHS.

References

- Black, E., Worth, H., Clarke, S., Obol, J. H., Akera, P., Awor, A., Shabiti, M. S., Fry, H., & Richmond, R. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence against women in conflict affected northern Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Conflict and Health, 13(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0219-8

- Browne, S. (2017). Making SDGs count for women and girls with disabilities. UN Women. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf.

- Chen, C., Haupert, S. R., Zimmermann, L., Shi, X., Fritsche, L. G., & Mukherjee, B. (2022). Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 226(9), 1593–1607. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiac136

- Chirwa, E., Jewkes, R., Van Der Heijden, I., & Dunkle, K. (2020). Intimate partner violence among women with and without disabilities: A pooled analysis of baseline data from seven violence-prevention programmes. BMJ Global Health, 5(11), e002156. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002156

- Dunkle, K., Gibbs, A., Chirwa, E., Stern, E., Van Der Heijden, I., & Washington, L. (2020). How do programmes to prevent intimate partner violence among the general population impact women with disabilities? Post-hoc analysis of three randomised controlled trials. BMJ Global Health, 5(12), e002216. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002216

- Dunkle, K., van der Heijden, I., Stern, E., & Chirwa, E. (2018). Disability and violence against women and girls. UKaid. https://www.whatworks.co.za/documents/publications/195-disability-brief-whatworks-23072018-web/file.

- Ellsberg, M., Arango, D. J., Morton, M., Gennari, F., Kiplesund, S., Contreras, M., & Watts, C. (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: What does the evidence say? The Lancet, 385(9977), 1555–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7

- García-Cuéllar, M. M., Pastor-Moreno, G., Ruiz-Pérez, I., & Henares-Montiel, J. (2022). The prevalence of intimate partner violence against women with disabilities: A systematic review of the literature. Disability and Rehabilitation, 0(0), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2025927

- Groce, N. E., & Mont, D. (2017). Counting disability: Emerging consensus on the Washington Group questionnaire. The Lancet Global Health, 5(7), e649–e650. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30207-3

- Gupta, J., Cardoso, L. F., Ferguson, G., Shrestha, B., Shrestha, P. N., Harris, C., Groce, N., & Clark, C. J. (2018). Disability status, intimate partner violence and perceived social support among married women in three districts of the Terai region of Nepal. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e000934. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000934

- Gupta, J., Falb, K. L., Carliner, H., Hossain, M., Kpebo, D., & Annan, J. (2014). Associations between exposure to intimate partner violence, armed conflict, and probable PTSD among women in rural côte d’Ivoire. PLoS One, 9(5), e96300. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096300

- Hossain, M., Pearson, R., McAlpine, A., Bacchus, L., Muuo, S. W., Muthuri, S. K., Spangaro, J., Kuper, H., Franchi, G., Pla Cordero, R., Cornish-Spencer, S., Hess, T., Bangha, M., & Izugbara, C. (2020). Disability, violence, and mental health among Somali refugee women in a humanitarian setting. Global Mental Health, 7, e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.23

- ICF International. (2012). Demographic and health survey sampling and household listing manual. MEASURE DHS. ICF International.

- Kelly, J. T. D., Colantuoni, E., Robinson, C., & Decker, M. R. (2018). From the battlefield to the bedroom: A multilevel analysis of the links between political conflict and intimate partner violence in Liberia. BMJ Global Health, 3(2), e000668. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000668

- Lumley, T. (2021). Survey: analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 4.0. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survey/survey.pdf.

- Marshall, J., & Barrett, H. (2018). Human rights of refugee-survivors of sexual and gender-based violence with communication disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2017.1392608

- Nosek, M. A., Foley, C. C., Hughes, R. B., & Howland, C. A. (2001). Vulnerabilities for abuse among women with disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 19(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013152530758

- OECD. (2016). States of fragility 2016: Understanding violence. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267213-en

- OECD. (2018). States of fragility 2018. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302075-en

- OECD. (2020). States of fragility 2020. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/ba7c22e7-en

- Pullum, T. (2013, February). The DHS program user forum: Weighting data. Pooling data & DV weights (Domestic Violence weighting Pooled data Or Country as Covariate?) https://userforum.dhsprogram.com/index.php?t=msg&goto=17861&&srch=domestic+violence+weight#msg_17861.

- RStudio Team. (2021). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/.

- Scolese, A., Asghar, K., Cordero, R. P., Roth, D., Gupta, J., & Falb, K. L. (2020). Disability status and violence against women in the home in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo. Global Public Health, 15(7), 985–998. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1741661

- Stern, E., van der Heijden, I., & Dunkle, K. (2020). How people with disabilities experience programs to prevent intimate partner violence across four countries. Evaluation and Program Planning, 79, 101770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101770

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017003001

- The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. (2017). Collaboration yields new disability questionnaire module. https://dhsprogram.com/Who-We-Are/News-Room/Collaboration-yields-new-disability-questionnaire-module.cfm.

- The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. (n.d.-a). DHS survey design: Frequently asked questions. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSM17/DHSM17.pdf.

- The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. (n.d.-b). Domestice violence module: Recommendations for implementation and questions. DHS. https://dhsprogram.com/topics/gender-Corner/upload/DHS_Domestic_Violence_Module_Ethical_Guidelines.pdf.

- The Demographic and Health Surveys Program. (n.d.-c). Team and Partners. https://dhsprogram.com/Who-We-Are/About-Us.cfm.

- The Washington Group on Disability Statistics. (2020a). Analytic guidelines: Creating disability identifiers using the Washington Group Short Set on functioning (WG-SS) stata syntax. https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/WG_Document__5C_-_Analytic_Guidelines_for_the_WG-SS__Stata_.pdf.

- The Washington Group on Disability Statistics. (2020b). The Washington group short set on functioning (WG-SS). https://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/fileadmin/uploads/wg/Documents/Questions/Washington_Group_Questionnaire__1_-_WG_Short_Set_on_Functioning.pdf.

- Valentine, A., Akobirshoev, I., & Mitra, M. (2019). Intimate partner violence among women with disabilities in Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16060947

- Wachter, K., Horn, R., Friis, E., Falb, K., Ward, L., Apio, C., Wanjiku, S., & Puffer, E. (2018). Drivers of intimate partner violence against women in three refugee camps. Violence Against Women, 24(3), 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801216689163

- World Health Organization. (2001). Putting women first: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/65893/WHO_FCH_GWH_01.1.pdf;jsessionid=C5FA1A585350E2550F9DBEBE31DCB081?sequence=1.

- World Health Organization. (2011). World report on disability. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Addressing violence against women in health and multisectoral policies: A global status report. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/350245.