ABSTRACT

Afghanistan has one of the highest rates of domestic violence in the world, with an estimated 46% women reporting lifetime violence. Survivors of domestic violence experience significant stigma from their families and communities, often in the form of blame, shame, gossip, and dismissal. While the manifestations of stigma are often the same across cultural settings, the drivers may be different. We conducted sixty semi-structured interviews with survivors of domestic violence in three provinces of Afghanistan. Data were analysed using thematic network analysis. Our analysis highlights stigma as a structural phenomenon in Afghanistan underpinned by mutually reinforcing structural elements (including community, government authorities, marital and natal families, other survivors and the self). In a country with a deeply patriarchal social structure, the main manifestation of stigma was the silencing of survivors of violence, as domestic violence was considered a private affair. Notions of honour were paramount in fuelling stigma against survivors of violence, as any action to report or leave violent relationships was considered dishonourable. Our findings have implications for the design of services to help survivors of violence seek help for the violence they experience, especially at a time when such services are increasingly constricted for women in Afghanistan.

Introduction

Goffman first described stigma as a ‘discrediting social attribute,’ launching decades of research into stigmatising attitudes, behaviours and experiences (Goffman, Citation1963). Since Goffman, others have argued for the role of power in stigmatising behaviours, and see stigma as a process of labelling, stereotyping, and discriminating, which results in a loss of status and marginalisation for those who experience it (Link & Phelan, Citation2001). Survivors of domestic violence often experience high levels of stigma, including from members of their community, health and law enforcement professionals, and their intimate partners (Crowe & Murray, Citation2015). In this article, we examine the different ways in which survivors of violence in Afghanistan encounter stigma in order to shape new understandings of how it impacts women’s lives in this and other similar contexts.

Although the concept of stigma, as applied to conditions such as HIV/AIDS and mental illness, has been thoroughly researched (Mahajan et al., Citation2008; Thornicroft et al., Citation2022), the same cannot be said for domestic violence stigma. In fact, the term ‘stigma’ is seldom used by survivors of violence, with personal accounts of domestic violence instead being filled with descriptions of blame, discrimination, isolation, and shame that survivors face from others, and how their stories of violence are often either dismissed or denied (Crowe & Murray, Citation2015; Tonsing & Barn, Citation2017). However, the conceptualisation of stigma and its measurement is growing with the recent development of new stigma models for intimate partner violence (IPV) (Overstreet & Quinn, Citation2013; Citation2018), and quantitative measurement tools such as the IPV Stigma Scale (Citation2021). This emerging body of research has established the gendered nature and the different dimensions of domestic violence stigma, including the ways in which individual experiences of stigma manifests at different levels of one’s self, their interpersonal interactions with others, and institutional responses to their help-seeking behaviours (Overstreet & Quinn, Citation2013; Citation2016). While an important first step, such understandings of domestic violence stigma have been mainly derived from Western settings and their suitability to non-Western contexts remains under-researched.

At a national level, Afghanistan has one of the highest rates of domestic violence in the world, with an estimated 46% of women aged 15–49 years experiencing lifetime intimate partner violence (Sardinha et al., Citation2022), with large variation between regions from 4% in the east to 12.6% in the southwest (Citation2022). The sources of domestic violence in this setting, however, are not restricted to intimate partners but often extend to in-laws, particularly the mother-in-law (Jewkes et al., Citation2019; Shively, Citation2011). This is because the patrilineal and patrilocal kinship structures in Afghanistan mean that most women live with their husbands’ extended families after marriage. Such structures not only increase risks of violence (Clark et al., Citation2010), but potentially allow women to be stigmatised further by in-laws. Although child marriage in Afghanistan was illegal until recently, nearly half of all women are married before the age of 18, which is significantly associated with an increased risk of domestic violence (Qamar et al., Citation2022) Studies of Afghan women who have migrated to high-income countries highlight how the stigma of getting a divorce deters many women from seeking help for domestic violence (Afrouz et al., Citation2021; Lipson & Miller, Citation1994). Moreover, in a setting where domestic violence is frequently condoned (Shinwari et al., Citation2022), and considered a family affair, women often experience the additional stigma of communities and authorities, both for experiencing violence and for speaking out about it (Abirafeh, Citation2007; Ahmad & Anctil Avoine, Citation2018).

Years of conflict in Afghanistan has had implications for the frequency and types of violence women experience, in part due to the expansion of the drug trade and increasing levels of severe poverty (Cottler et al., Citation2014; Mannell et al., Citation2021). Widespread poverty caused by the decades long conflict has restricted families’ choices in protecting women and girls from forced and abusive marriages and has translated into domestic violence as a means of exerting control over women (Mannell et al., Citation2021). Although, Afghanistan’s previous governments have made attempts to reform the legal and policy environment in an effort to reduce gender-based violence, it has often met with stiff resistance, both from Afghan society and policymakers. For example, in 2009 the law on the Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) was passed by Presidential Assent but not ratified by the Parliament because it contradicted Islamic laws and certain articles of the Constitution (Qazi Zada, Citation2021). However, discussions on EVAW did allow for the setting up of safe houses and family courts (instead of informal jigras) to resolve domestic violence cases (Sirat, Citation2022). Despite this step forward, implementation was weak and women continued to struggle with a socio-legal environment that continued to favour men over women. Reporting of violence remained low, due to a combination of the normalisation of violence and the persistent societal stigma for speaking up against it (Qazi Zada, Citation2021). Programmes set up by international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to address gender-based violence during this period did not fare much better (Citation2021). For example, a social and economic empowerment programme for women succeeded in improving gender inequitable attitudes and reducing food insecurity but failed to reduce domestic violence (Citation2020). Such NGO interventions with women have now been banned. In 2021, after withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, the Taliban took over from the previous Islamic republican government and reinstated many of the strict controls that had previously been in place on women’s lives and freedoms (Owen, Citation2022).

Countries with a high-prevalence of domestic violence and related stigma (Mannell et al., Citation2022) require a different approach to domestic violence stigma than has been developed in the literature. Many conceptualizations of domestic violence stigma derived from Western settings emphasise the stigma survivors experience because others perceive them to be complicit in their revictimization; survivors are perceived to choose to stay on or return to abusive partners, and therefore seen as undeserving of support (Crowe & Murray, Citation2015; Meyer, Citation2016). However, this conceptualisation of stigma is not applicable in other settings, including Afghanistan, where women are expected to bear violence quietly and leaving a violent relationship is heavily stigmatised (McCleary-Sills et al., Citation2016; Menon & Allen, Citation2018). This article, therefore, addresses the need to understand how domestic violence stigma manifests in women’s lives in such settings, through engaging with the lived experiences of women in Afghanistan. Such understandings of domestic violence stigma are particularly relevant now, given Afghanistan’s present socio-political climate, where women’s ability to speak out against domestic violence have been severely curtailed.

Conceptual framework

As a conceptual framework for understanding how stigma manifests, the IPV Stigmatisation Model by Overstreet and Quinn (Citation2013) synthesised experiences of domestic violence stigma as different categories of experience, including: internalised stigma (when survivors endorse the negative stereotypes placed upon them), anticipated stigma (fear of consequences when people know about the abuse), and cultural stigma (how negative stereotypes at the societal level influences stigma experiences at the individual and interpersonal level). Evidence mainly from the U.S. supports this framework, with each component of stigma deterring help seeking (Overstreet & Quinn, Citation2013) and centrality of the stigmatised identity moderating the effect of internalised stigma on disclosure (Overstreet et al., Citation2017). However, the model has not been used in other social contexts. We use this framework to broaden our definition of the stigma experienced by survivors of domestic violence in Afghanistan to include not only interpersonal instances of women being refused services when seeking help, but also the role that internalised, anticipated and cultural forms of stigma play. While this framework helps us in understanding how women’s experiences of stigma becomes a barrier in their ability to seek help, both from formal and informal sources, we will also interrogate the relevance of the framework for this specific context.

Methods

This article draws on data from a study on the mental health of women experiencing domestic violence in Afghanistan funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and carried out by Humanitarian Assistance for Women and Children of Afghanistan (HAWCA). From April – October 2019, HAWCA staff completed semi-structured interviews with sixty women. All women interviewed were survivors of domestic violence and had received or were receiving services for their experiences from local NGOs as well as other service providers operating in provinces outside of Kabul. Many of the women interviewed were living in shelters for survivors of domestic violence provided by these NGOs (known as safe houses), and all were receiving psychosocial support services to help them cope with the violence they had experienced.

Recruitment and sample

The sample was designed to capture a range of different perspectives and experiences about the mental health consequences of domestic violence across Afghanistan’s diverse regional and ethnic areas and interviews were carried out in three provinces: Kabul, Nangarhar and Bamyan. These specific provinces were chosen to ensure diversity and for safety concerns at the time of data collection in 2019. Travel required specialised vehicles and armed guards to ensure the safety of HAWCA staff.

Women were recruited through the NGO where they were currently receiving services and asked if they would like to participate in an interview. The aims of the study were explained to women in detail, including that their data would be used to design improved services for women in Afghanistan. They were engaged in an open conversation where they could ask any questions and discuss the pros and cons of participating in the interview. The interviewer explained that the interview could be stopped at any time and there would be no consequences or implications for the services they were receiving whether they participated or not. Each point of the consent form was covered as part of this conversation to ensure the inclusion of women with low-literacy. If women agreed to participate in the study after this conversation with the interviewer, they were asked to give recorded verbal consent and were given an information sheet to keep.

Data collection

All women were interviewed in Dari (as this was the common language understood by all ethnic groups) by a female HAWCA staff member in a private area where their conversation could not be overheard. A topic guide was used, which generally covered three main topics: personal experiences of violence, mental health and coping, and mental health service-provision. The majority of interviews lasted between 20 min and 1 h. Although women were not asked about stigma directly, women’s accounts included a wide range of different stigmatised experiences, which were drawn on in our analysis.

As in any study of domestic violence, there were several ethical concerns that needed careful management, and we are committed to adhering to the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines on research with women experiencing violence (WHO, Citation2001). If a participant experienced distress during an interview or group discussion, HAWCA staff members were available to ensure appropriate support could be provided. HAWCA staff were highly trained in conducting interviews on sensitive topics and supporting women, with clear protocol in place for any signs of distress arising from the interview process. The broader project team debriefed at the end of each data collection trip and there was access to a psychologist available for all members of the project team. Ethical approval was obtained from UCL (ref# 2744/007) and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Ministry of Health (ref# IRB.A.1902.0007).

Participant characteristics

A third of women were from Kabul, Bamyan, and Nagarhar respectively. The majority of women interviewed were aged between 18–34 (87%) and had little or no formal education (57%). Their median age was 25 years, with women having between zero to eight children (median = 2). The majority (41%) had no formal education, 15% had completed primary or middle school, 28% up to high school or 12th grade, and 15% had some level of tertiary education.

Data analysis

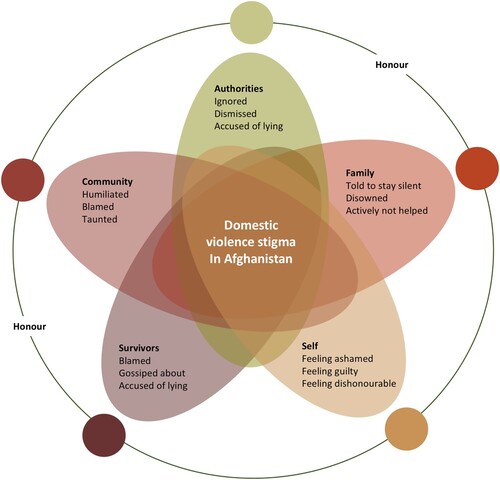

Interview transcripts were coded using a combination of inductive and deductive coding using a thematic analytical procedure described by Attride-Stirling (Attride-Stirling, Citation2001), using Nvivo qualitative software (version 12). An initial coding framework was developed based on theories of domestic violence stigma, however, it soon became apparent that existing conceptual models did not fully encompass women’s experiences of violence in Afghanistan. We therefore approached the data from a far more inductive approach, coding the data according to instances of overt discrimination against women experiencing domestic violence, and examining these basic codes to determine overarching patterns in these experiences. This process led to the development of a thematic map with a summative global theme of stigma as a barrier to help seeking to which the organising themes of different social structures (including extended and natal families, community, authorities, and self) contributed. The overarching themes presented below summarise the stigma related to domestic violence that women experience according to each of these social structures.

Results

The overarching theme that came out of the interviews was that stigma was a persistent barrier to help seeking for domestic violence. Seeking help for domestic violence entailed making the violence public, which disrupted social norms centreing on family ‘honour’. Honour was the driver of domestic violence stigma, with honour being used to justify both the violence inflicted upon women as well as stigmatisation of women who spoke up against the violence or tried to leave violent relationships. Women described being stigmatised by natal and marital families, friends and neighbours, from the authorities, and sometimes even by fellow survivors of violence due to the intersectional stigma of being women, experiencing domestic violence, and diminishing their families’ honour.

Stigma from natal family

Women described turning to members of their natal families for help and support when they experienced domestic violence. However, in women’s descriptions of their experiences, the natal family was often a principal source of stigma. Almost all the women interviewed spoke of how their parents or other family members, mainly brothers, were unsympathetic to the violence they had experienced. They explained how speaking about violence to others is perceived as compromising the family’s honour. As a result, many of the women were advised to tolerate the violence quietly and their pleas for help were ignored by family members.

I could not discuss my problems with anyone, not even my mother. She told me that I have to tolerate it because of my brother and that everything will get better. They reminded me all the time that once a girl is married her dead body must come out of her husband’s house. I went to my mother many times and asked for help but she sent me back without telling my brothers. She told me that I belong to my husband’s house and these things always happen between families and is normal. (Participant 27, Bamyan province, 23 years old, 4 children)

He [husband] always beat me with his belt because it hurt a lot. He used to slap me. He said he will beat me so much that I would forget my parents. I was completely helpless after he beat me a lot. I did not know what to do so I picked something and threw it at the window to break the glass so I could shout for help to his father. He took the shards of glass and cut my entire hands with it [showing scars]. I bled so much and till this day I cannot feel anything in my hands. Then his father came and took him out of the room. I was in very bad condition. Whenever I would tell my father, he would listen quietly. After a couple of times, he said that is your home and husband and life, you have to tolerate it. (Participant 1, Kabul city, 20 years old, no children)

Yes, I told my father. He would say that he couldn’t say anything to his uncle’s wife because he would be shamed by the entire family (Participant 20, Kabul city, 56 years old, 5 children).

They did nothing for me. They are very traditional and told me that I would dishonour them if I get divorced. They said they won’t be able to face people and people will make fun of a divorced daughter. (Participant 36, Bamyan province, 27 years old, 4 children)

My father refused to help me during my divorce case. He said I have dishonoured them and disowned me. My uncles and brothers did the same. They said I have brought shame upon them. (Participant 13, Kabul city, 33 years old, 5 children)

On my wedding night, these were my father’s words: ‘listen to me carefully, I don’t want to hear complaints about you from your in-laws. If they eat your meat you still have [your] bones to live [on], you don’t have [a] stomach that gets hungry if they don’t give you food, you don’t have ears if they talk rude [to you], you don’t have eyes if you see anything bad from them.’ We women have learned to ask God for honour and save us from shame, and seek forgiveness for sins we never committed. When we are divorced, people just assume that we were lazy and useless which is why our husbands left us for other women. This is our pitiful life. (Participant 37, Bamyan province, 30 years old, 2 children)

Stigma from husband and in-laws

Husbands and in-laws stigmatised women for making domestic violence public by forcefully silencing their calls for help, often through the perpetration of further violence. Women often spoke about how husbands and their families would not allow them to speak to anyone outside of the household, which itself is a form of psychological violence against women. Apart from this, if husbands and in-laws found out that women were speaking to others about the violence it would spur further violence against her:

Mostly, if women in Afghanistan share their problems, the husband will become violent towards her because she is sharing private home issues with people. (Participant 32, Bamyan province, 21 years old, no children)

There are risks involved. For example, if my cousin tells her family, it may become a bigger problem. I think her family and her husband’s family should openly share it and find a solution for it. But here if her family gets involved, it makes matters worse and the violence only increases and the only option is to get her divorced. (Participant 28, Bamyan province, 26 years old, no children)

My father-in-law also came and said, ‘I have seven sons and even if each of them was beheaded I will not [let you] divorce [my son]. There is no way you can get a divorce. There is no divorce in our traditions and family. Come back and we will give you the life you want. The boy [my son] will get better.’ The boy wouldn’t say anything. He would just stare at me. He spoke once and said, ‘Come back and I will behead you.’ He said this in front of everyone, my lawyer and the Ministry officials. (Participant 1, Kabul city, 20 years old, no children)

Stigma from friends and community

The stigma of domestic violence was also evident in women’s accounts of people gossiping and blaming women for the violence they experienced. Domestic violence was considered a private affair so women said, ‘I can’t tell anyone outside our family because it is shameful’ (Participant 63). Women believed that they would not get support if they told others about the violence because of how violence is normalised within Afghan society:

For example, if a woman talks about her problems to a friend or relative, that woman may gossip or reveal her secrets to her husband so she has trust issues and is usually scared. But even if she trusts someone, the other women say that everyone faces these problems and [you must] be patient and bear it. (Participant 28, Bamyan province, 26 years old, no children)

I didn’t trust anyone. How can you trust your eyes? Even your best friend doesn’t care about you. When you tell them your pain and suffering they will easily tell others. I have always kept my sadness and pain to myself. People outside used to think I have an incredible life. They didn’t know the truth (Participant 15, Kabul city, 19 years old, 1 child).

They easily accuse her of speaking up and blame her for complaining about her life to others. They taunt her for not adapting to her new home. (Participant 31, Bamyan province, 28 years old, 2 children)

There is a lot of violence there. Nobody hears their voice. Women have burned themselves or killed themselves to escape the violence. I knew those women. There was one who was beaten and hurt so much that she finally doused herself in petrol and burned completely. Even then people didn’t understand her or care about her and still accused her of being immoral. (Participant 2, Kabul city, 25 years old, 2 children)

They treat their women like slaves and constantly abuse and rape them. They make women do the hardest chores. The poor women tolerate it to save themselves from a bad name. (Participant 46, Nangarhar province, 28 years old, 7 children)

Stigma from authorities

All of the women interviewed for this study sought help from authorities for the violence they experienced. Women described how encounters with the health system (to be treated for injuries or attempted suicide) often led to stigmatising experiences whereby healthcare providers either refused to take women’s stories seriously or maintained a silence around the violence. A woman who tried committing suicide by ingesting poison spoke of how healthcare staff sent her home without asking why she had done this:

I tried to commit suicide twice. Once I took poison and my mother-in-law and sister-in-law took me to [name of hospital]. The hospital didn’t investigate at all. I want to request hospitals to involve the police and investigate when a woman tries to poison herself. Both times I was taken to the hospital and both times woke up at home without anyone asking me why I did it. (Participant 11, Kabul city, 27 years old, no children)

… once in our village a lady cooked three eggs for her husband because he asked [her to]. Her mother-in-law was not at home. The husband went for work and mother-in-law came she and asked that what she cooked. The daughter-in-law said that my husband asked for eggs for lunch so I cooked for him. But the mother-in-law got angry and hit her with a knife and told her that ‘you are lying, you ate the eggs.’ After her death, the village people called her husband and told him that your wife was killed by your mother. He came and said the truth. The family of that woman complained to the police station and local authority but nothing happened. (Participant 38, Bamyan province, 25 years old, 2 children)

There was a police officer who did body searches. She sat me down and lectured me to return home. I said I couldn’t go back because my in-laws were mountain men and would kill me. They would have definitely killed me if I returned. I was also sad there. They weren’t allowing me inside. I sat there and refused to return home. I said, ‘Do whatever you want. You can kill me or send me to prison, but I will not budge.’ Then a lawyer came and they introduced me to her and she brought me to HAWCA … At first, the Ministry officials blamed me and told me to give my marriage time (Participant 1, Kabul city, 20 years old, no children).

I saw a good policeman and asked for help. I told him that I was a widow with two kids. He then advised me to come to a safe house. I was scared of my husband finding me. I had nowhere to go so I spent one night in a hospital. I started begging people for money. God damn my husband who even forced me to stoop to beggary … I was in rags. I went to the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and they treated me very rudely. They sent me to the attorney’s office and they brought me here. (Participant 5, Kabul city, 24 years old, 2 children)

Women are really oppressed in this country. The government doesn’t listen to them either. They all say women have rights, this and that, but I know that we don’t. When I make legal claims, they accuse me of lying. Now I only believe in God and nothing else … When I went to the court that day, they asked me to bring my husband before court to get a divorce. I told them that he will never come. They ask for the impossible. (Participant 2, Kabul city, 25 years old, 2 children)

Self-stigma

Women themselves felt ashamed for experiencing violence and did not want to talk to others about it. They too felt it was a private affair, and felt that if they tolerated the violence it would get better over time. Women described how they decided to ask for help only when things became unbearable. They also expressed shame at having experienced the violence and felt demeaned because of it:

If the woman has domestic problems and discloses them, there is a chance that she faces violence because of sharing it with outsiders. Women are ashamed of having these issues. They think they are inferior in the eyes of everyone. (Participant 29, Bamyan province, 38 years old, 5 children)

I was alone and I had no one to help me, even my own family was poor and helpless. I could not fight for myself despite working hard to keep them happy. Though it was never my fault, I felt guilty. (Participant 30, Bamyan province, 33 years old, 3 children)

My whole family knew. They all came several times to get my divorce but I didn’t agree. I have my honour and pride. I don’t want to dishonour my family and tribe. (Participant 58, Nangarhar province, 30 years old, no children)

Stigma among women at the safe houses

Women who had escaped violence and were staying in safe houses for survivors of violence were often there because of the stigma they had experienced from society and their natal families. Rather than supporting others in a similar situation also living in the shelter, they often used stigmatising language to describe others’ situations, and refused to share their stories with those around them. Some women said they did not believe the stories of other women:

They usually lie about their cases so I don’t know how I feel. (Participant 52, Nangarhar province, 26 years old, 1 child)

Sometimes women are bad women. They have several husbands, one legitimate and the others illegitimate. A lot of what happens at home is in the hands of the woman. (Participant 47, Nangarhar province, 50 years old, 7 children)

… I don’t tell anyone else [other than the psychologist]. Once I told another girl here and she accused me of doing bad things. She taunted me for being given to other men by my brothers [crying]. (Participant 12, Kabul city, 18 years old, no children)

No, people have a habit of revealing secrets so I don’t trust anyone. Once I shared it and they shared it with others so I don’t do it anymore. (Participant 36, Bamyan province, 26 years old, 1 child)

Discussion

Women’s accounts suggested that domestic violence stigma was common in this setting and that this stigma came from different social structures, including their natal family, husband and in-laws, friends and community, from the authorities, and even from other survivors of violence. Stigma manifested as further violence, gossip, blame, disbelieving or being dismissed by others. This stigma was present from the beginning until the end of women’s experiences: it was part of the violence experience, part of women’s experiences of help seeking, and also a part of the community or safe house settings once women had escaped the violent situation. Likely as a result of the persistence of their stigmatisation, women internalised the stigma they received from others, often endorsing negative societal beliefs about domestic violence and feeling guilty about their experiences. However, the most significant manifestation of stigma in this setting was the forced silencing of women and the lack of support when trying to leave violent relationships. In other words, while the experience of violence was stigmatised, the reporting or speaking out about the violence was stigmatised even more.

This is unlike the domestic violence stigma that women experience in Western settings, where women are encouraged to leave abusive relationships and their failure to do so attracts negative stereotypes, blame, and shame from others (Meyer, Citation2016). In Afghanistan, domestic violence is largely considered a private family matter, with strong patriarchal social norms dictating women bear violence quietly and maintain the family’s honour (Afrouz et al., Citation2021; Luccaro & Gaston, Citation2014). This may be related to differences between how stigma operates in collectivist versus individualistic societies (Ho & Mak, Citation2013; Citation2021), where in the former women are stigmatised when they do not protect themselves against domestic violence, whereas in the latter they are stigmatised for not protecting the honour of their family and accused of placing their own needs before those of their family or clan. While the implications of stigma may be similar, the drivers of stigma between these different contexts are fundamentally different.

The socio-political context of Afghanistan has magnified notions of family honour in ways that may be further compounding the stigma of domestic violence seen in our study. Decades of conflict has dismantled familial and communitarian systems of support (Mannell et al., Citation2021), potentially contributing to rigorous attempts to hold onto honour as a social structure that provides stability and a sense of identity. The imposition of foreign aid in the name of ‘liberation’ or ‘empowerment’ of Afghan women has been interpreted as making men feel like they have lost their honour (Abirafeh, Citation2007) and fuelling stigma towards women who bring on such ‘dishonour’ through their actions. The takeover of the Afghanistan government by the Taliban in 2021 has further institutionalised domestic violence stigma in ways that now make it nearly impossible for women to report violence or seek help for violence (The New York Times, Citation2022; UN Women, Citation2022). The safe houses are no longer operational, and schools and universities have been closed to women. At the time of writing, a ban was in place for women working for NGOs, further limiting possibilities for women to obtain help for domestic violence given strict protocols about women not talking to men, even in service-provision roles. Journalists have reported a rise in suicides among women (with public hospitals instructed to hide any proof as families keep their secrets) (BBC News, Citation2022).

While considerably different to the western context, the role of persistent conflict and instability in perpetuating domestic violence stigma in Afghanistan shares similarities with other countries experiencing a high-prevalence of violence against women. A systematic review of 23 high-prevalence countries points to exposure to other forms of violence, including armed conflict, witnessing parental violence and child abuse, as an important risk factor for a country’s higher-than-average prevalence of intimate partner violence (Mannell et al., Citation2022). Stigma may play a role in normalising domestic violence in contexts where exposure to other forms of violence are common, in effect downplaying the severity of exposure to other potentially traumatising events. In other words, stigmatising those who complain or seek help for domestic violence, as damaging as this is for survivors, may also be a coping mechanism for a society traumatised by violence more broadly.

The IPV Stigmatisation Model is an important framework that has been used to conceptualise domestic violence stigma and its impact on help seeking. The model has primarily been used in North American settings to show how the different dimensions of stigma deter help seeking for domestic violence (Overstreet & Quinn, Citation2013). The model has been built on the premise that IPV stigma is primarily driven by women’s failure to leave violent relationships despite being encouraged to do so (Overstreet et al., Citation2017). Our study shows that the driver of domestic violence stigma is quite the opposite in some settings, with women being encouraged to stay in abusive relationships, and any attempt to leave being highly stigmatised by society. As stigma is a cultural process, its drivers and manifestations may differ in different settings, depending on the history, culture, political and socioeconomic context, which may be captured by an intersectional framework (Turan et al., Citation2019). Our findings point to the importance of adapting the IPV Stigmatisation Model for different cultural contexts.

We therefore conceptualise our findings about women’s experience of domestic violence stigma in Afghanistan as intersecting experiences from different social structures (). This framework provides scope for recognising how overlapping social structures at different socioecological levels manifest as stigmatising experiences in women’s lives and are shaped by collective notions of honour. The social structures that define women’s lives – including families, communities, self and other survivors – come together to determine and magnify the overall stigma experience for survivors of domestic violence in Afghanistan.

While we have taken a focus on women’s lived experiences to emphasise the realities of violence and its impacts for women in Afghanistan, our findings point to the need for intersectional approaches to domestic violence stigma. This approach recognises that people’s experiences of stigma are often the result of interlocking structures of oppression which strengthens and reproduces existing social inequalities (Bowleg, Citation2008; Turan et al., Citation2019), and as Bowleg states, such an approach is not complete without understanding the ‘sociohistorical realities of historically oppressed groups’ (Bowleg, Citation2008). Applying an intersectional lens to domestic violence stigma in Afghanistan, therefore, allows us to see how systemic gender discrimination shape women’s experiences of domestic violence stigma.

While beyond the scope of this article, an intersectional framework can also help identify additional marginalised identities, such as women in poverty, women with mental ill health or women who are partners of addicts: identities that can contribute to additional stigmatisation of domestic violence. An intersectional lens may therefore help identify the most vulnerable women who are in need of services and help design culturally-appropriate solutions that draw on the positive aspects of Afghan culture (including the rich history of Persian art and storytelling) instead of its negatives. In the current context, this may include finding points of resistance within the Taliban’s interpretation of Sharia law and working to improve the support services that do exist for women such as mental health and psychosocial services offered by NGOs and UN organisations who still continue to operate in the region.

Despite the important contributions made by this study, it had some limitations. Since interviews were conducted as part of a broader study on domestic violence and mental health, specific questions on stigma were not asked. The fact that there was such clear evidence of stigma from women’s accounts despite this limitation shows just how strong domestic violence stigma is in this setting. All of the women interviewed were already accessing services for domestic violence and therefore the experiences of women who were not able to access such services were not captured. That is probably a large majority of women in Afghanistan, considering the limited availability of services and the difficulty of access due to many barriers, including social stigma against women who tell others about their experience of violence (Mannell et al., Citation2018). As such, our study may underplaying the full extent of the problem.

Conclusions

Stigma of domestic violence is common in Afghanistan, but the main driver of this stigma is making the violence public or leaving a violent relationship. Traditional gender norms dictate that women bear violence silently. Services based on western ideas of helping women escape violent relationships violate these norms and incite stigma and further perpetuate violence at the hands of families, communities, and authorities. A culturally sensitive, trauma-informed solution is needed, one that works with the existing system to break down stigmatising responses to survivors at multiple levels.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank our project partner in Afghanistan – the Humanitarian Assistance for Women and Children of Afghanistan (HAWCA) – without which this study would not have been possible. The current environment is not easy for organisations committed to assisting women in Afghanistan, and we have profound respect for the ongoing efforts of HAWCA at this challenging time. RM and JM conceptualised the paper. RM completed the qualitative analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LS collected the data. DD is the PI on the project and responsible for the funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed on the final submitted version.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abirafeh, L. (2007). Freedom is only won from the inside: Domestic violence in post-conflict Afghanistan. Retrieved 12th October, from http://wunrn.com/wp-content/uploads/112106_afghnaistan_domestic.pdf.

- Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R., & Taket, A. (2021). Afghan women’s barriers to seeking help for domestic violence in Australia. Australian Social Work, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.2004179

- Ahmad, L., & Anctil Avoine, P. (2018). Misogyny in ‘post-war’ Afghanistan: the changing frames of sexual and gender-based violence. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1210002

- Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- BBC News. (2022). The secrets shared by Afghan women. Retrieved 5th February 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-63638876.

- Bowleg, L. (2008). When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59(5), 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z

- Clark, C. J., Silverman, J. G., Shahrouri, M., Everson-Rose, S., & Groce, N. (2010). The role of the extended family in women's risk of intimate partner violence in Jordan. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.024

- Cottler, L. B., Ajinkya, S., Goldberger, B. A., Ghani, M. A., Martin, D. M., Hu, H., & Gold, M. S. (2014). Prevalence of drug and alcohol use in urban Afghanistan: epidemiological data from the Afghanistan National Urban Drug Use Study (ANUDUS). The Lancet Global Health, 2(10), e592–e600. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70290-6

- Crowe, A., & Murray, C. E. (2015). Stigma from professional helpers toward survivors of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 6(2), 157–179. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.6.2.157

- Crowe, A., Overstreet, N. M., & Murray, C. E. (2021). The intimate partner violence stigma scale: Initial development and validation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), 7456–7479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519834095

- Gibbs, A., Corboz, J., Chirwa, E., Mann, C., Karim, F., Shafiq, M., Mecagni, A., Maxwell-Jones, C., Noble, E., & Jewkes, R. (2020). The impacts of combined social and economic empowerment training on intimate partner violence, depression, gender norms and livelihoods among women: an individually randomised controlled trial and qualitative study in Afghanistan. BMJ Global Health, 5(3), e001946. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001946

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall.

- Ho, C. Y., & Mak, W. W. (2013). HIV-related stigma across cultures: Adding family into the equation. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Stigma, discrimination and living with HIV/AIDS (pp. 53–69). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Jewkes, R., Corboz, J., & Gibbs, A. (2019). Violence against Afghan women by husbands, mothers-in-law and siblings-in-law/siblings: Risk markers and health consequences in an analysis of the baseline of a randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0211361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211361

- Li, Y., Slopen, N., Sweet, T., Nguyen, Q., Beck, K., & Liu, H. (2021). Stigma in a collectivistic culture: Social network of female sex workers in China. AIDS and Behavior, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03383-w

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Lipson, J. G., & Miller, S. (1994). Changing roles of Afghan refugee women in the United States. Health Care for Women International, 15(3), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339409516110

- Luccaro, T., & Gaston, E. (2014). Women's access to justice in Afghanistan: Individual versus community barriers to justice. United States Institute of Peace.

- Mahajan, A. P., Sayles, J. N., Patel, V. A., Remien, R. H., Ortiz, D., Szekeres, G., & Coates, T. J. (2008). Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS, 22(Suppl 2), S67–S79. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62

- Mannell, J., Ahmad, L., & Ahmad, A. (2018). Narrative storytelling as mental health support for women experiencing gender-based violence in Afghanistan. Social Science & Medicine, 214, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.011

- Mannell, J., Grewal, G., Ahmad, L., & Ahmad, A. (2021). A qualitative study of women’s lived experiences of conflict and domestic violence in Afghanistan. Violence Against Women, 27(11), 1862–1878. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220935191

- Mannell, J., Lowe, H., Brown, L., Mukerji, R., Devakumar, D., Gram, L., Jansen, H. A., Minckas, N., Osrin, D., & Prost, A. (2022). Risk factors for violence against women in high-prevalence settings: a mixed-methods systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 7(3), e007704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007704

- McCleary-Sills, J., Namy, S., Nyoni, J., Rweyemamu, D., Salvatory, A., & Steven, E. (2016). Stigma, shame and women's limited agency in help-seeking for intimate partner violence. Global Public Health, 11(1-2), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1047391

- Menon, S. V., & Allen, N. E. (2018). The formal systems response to violence against women in India: A cultural lens. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1-2), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12249

- Meyer, S. (2016). Still blaming the victim of intimate partner violence? Women’s narratives of victim desistance and redemption when seeking support. Theoretical Criminology, 20(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480615585399

- Murray, C. E., Crowe, A., & Overstreet, N. M. (2018). Sources and components of stigma experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(3), 515–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515609565

- Overstreet, N. M., Gaskins, J. L., Quinn, D. M., & Williams, M. K. (2017). The moderating role of centrality on the association between internalized intimate partner violence-related stigma and concealment of physical IPV. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12218

- Overstreet, N. M., & Quinn, D. M. (2013). The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746599

- Owen, L. (2022). Afghanistan face veil decree: ‘It feels like being a woman is a crime’. Retrieved 12th October, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-61402309.

- Qamar, M., Harris, M. A., & Tustin, J. L. (2022). The association between child marriage and domestic violence in Afghanistan. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5-6), 2948–2961. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520951310

- Qazi Zada, S. (2021). Legislative, institutional and policy reforms to combat violence against women in Afghanistan. Indian Journal of International Law, 59(1-4), 257–283. doi:10.1007/s40901-020-00116-x

- Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., & García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399(10327), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02664-7

- Shinwari, R., Wilson, M. L., Abiodun, O., & Shaikh, M. A. (2022). Intimate partner violence among ever-married Afghan women: patterns, associations and attitudinal acceptance. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 25(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-021-01143-2

- Shively, K. (2011). When domestic violence is not “intimate partner violence”: Cases from Turkey and elsewhere. Practicing Anthropology, 33(3), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.17730/praa.33.3.0730mh7235601700

- Sirat, F. (2022). Violence against women: Before and after the Taliban: Oxford Human Rights Hub. Retrieved 12th October, from: https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/violence-against-women-before-and-after-the-taliban/.

- Spangaro, J., Toole-Anstey, C., MacPhail, C. L., Rambaldini-Gooding, D. C., Keevers, L., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2021). The impact of interventions to reduce risk and incidence of intimate partner violence and sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict states and other humanitarian crises in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Conflict and Health, 15(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00417-x

- The New York Times. (2022). Taliban Takeover in Afghanistan. Retrieved 12th October from https://www.nytimes.com/news-event/taliban-afghanistan.

- Thornicroft, G., Sunkel, C., Alikhon Aliev, A., Baker, S., Brohan, E., el Chammay, R., Davies, K., Demissie, M., Duncan, J., Fekadu, W., Gronholm, P. C., Guerrero, Z., Gurung, D., Habtamu, K., Hanlon, C., Heim, E., Henderson, C., Hijazi, Z., Hoffman, C., … Winkler, P. (2022). The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health. The Lancet, 400(10361), 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2

- Tonsing, J., & Barn, R. (2017). Intimate partner violence in South Asian communities: Exploring the notion of ‘shame’to promote understandings of migrant women’s experiences. International Social Work, 60(3), 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816655868

- Turan, J. M., Elafros, M. A., Logie, C. H., Banik, S., Turan, B., Crockett, K. B., Pescosolido, B., & Murray, S. M. (2019). Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Medicine, 17(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9

- UN Women. (2022). In focus: Women in Afghanistan one year after the Taliban takeover. Retrieved 12th October, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/in-focus/2022/08/in-focus-women-in-afghanistan-one-year-after-the-taliban-takeover.

- WHO. (2001). Global programme on evidence for health. Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women.