ABSTRACT

Growth mindset, persistence, and self-efficacy are important protective factors in understanding adolescent psychopathology, including depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours. Previous studies have shown that dimensions of self-efficacy (academic, social, and emotional) have differential protective effects with mental health outcomes and these differences vary by sex. This study examines the dimensional mediation of self-efficacy from motivational mindsets on anxiety, depression, and externalising behaviours in a sample of early adolescents ages 10-11. Surveys were administered to participants to measure growth mindset and persistence on internalising and externalising symptoms. The Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) was used to measure domains of self-efficacy for mediation analysis. Multi-group structural equation modelling by sex indicated that structural paths were not invariant by sex. Significant direct effects were identified from persistence to externalising behaviours in boys, and significant direct effects were identified from growth mindset to depression in girls. In a sample of Tanzanian early adolescents, self-efficacy mediates the protective association between motivational mindsets on psychopathology. Higher academic self-efficacy was associated with reduced externalising problems in both boys and girls. Implications for adolescent programmes and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Self-efficacy has been defined as the perceived ability to complete a desired action, novel task, or to cope with a broad range of stressors (Bandura et al., Citation1999; Luszczynska et al., Citation2005). Self-efficacy is a protective factor that is integral to the process of cognitive appraisal of stressors or challenges and is related to mental health and psychological disorders (Bandura et al., Citation1999; Sandin et al., Citation2015; Schönfeld et al., Citation2016). The development of self-efficacy during adolescence is a function of reciprocal relationships between intrapersonal factors (affective, behavioural, and cognitive capacities) and environmental factors, such that self-efficacy influences individual patterns of behaviour with the environment and is influenced by the conditions of the environment.

Self-efficacy is important to understanding adolescent psychopathology, including depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours (Bernstein et al., Citation1996; Birmaher et al., Citation1996). Self-efficacy can affect decision making, effort, persistence, and ability to achieve goals. Self-appraisal of self-efficacy is tied to four primary sources: actual performance, vicarious experiences, persuasion, and physiological reactions. During adolescence, social comparisons and knowledge of performance by peers may be particularly influential in shaping self-appraisal of self-efficacy (Schunk & Meece, Citation2006). Understanding the relationships between self-efficacy and psychopathology within the context of social norms, influenced by factors like age, gender, and culture, can provide opportunities to effectively promote mental wellbeing in adolescents.

Previous studies have reported that higher self-efficacy is associated with lower depressive symptoms, and low self-efficacy is related to higher anxiety, distress, and depression symptoms (Bandura et al., Citation1999; Comunian, Citation1989; Ehrenberg et al., Citation1991; Kashdan & Roberts, Citation2004; Kwasky & Groh, Citation2014; Luszczynska et al., Citation2005). Self-efficacy is also associated with positive mental wellbeing, optimism, and life-satisfaction (Azizli et al., Citation2015; Luszczynska et al., Citation2005). While the mediating role of general self-efficacy has been studied most in terms of mediating stressful life events on mental wellbeing, research is needed to understand how self-efficacy may mediate protective factors. Identifying modifiable protective factors is important for early adolescent prevention programmes that seek to reduce risk for mental health problems that emerge in mid- to late-adolescence.

While previous research has indicated the mediating role of general self-efficacy in a broad range of areas, a domain specific analysis of self-efficacy is needed to better differentiate self-efficacy domains and relationships with mental wellbeing (Andretta & McKay, Citation2020). Self-efficacy can be broken down into three domains: academic, social, and emotional. Academic self-efficacy refers to the individual’s perceived ability to control their learning behaviours, master subjects, and meet scholastic expectancies; social self-efficacy refers to the individual’s perceived ability to be authentic and assertive in peer relationships; and emotional self-efficacy refers to the individual’s perceived ability to cope with negative emotions (Muris, Citation2001).

Research indicates that self-efficacy acts as a mediator between stress and psychopathology (Maciejewski et al., Citation2000). More recently, research has explored how domains of self-efficacy are related to mental health. One study found that academic and emotional self-efficacy were significantly negatively correlated with depressive symptoms (Muris, Citation2001). Other studies have shown that academic self-efficacy was the best predictor of depression symptoms in comparison to social and emotional self-efficacy (Tahmassian & Anari, Citation2009). Higher emotional self-efficacy has been associated with higher levels of wellbeing and lower psychological symptoms (Andretta & McKay, Citation2020; Wigelsworth et al., Citation2017). Higher social self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with reduced symptoms of depression, and lower social and emotional self-efficacy has been shown to be associated with greater anxiety symptoms and social phobias (Ahmad et al., Citation2014; Muris, Citation2002). Analysis of domains of self-efficacy and relationships with mental health can increase the precision of intervention approaches that target protective factors for mental health (Kannangara et al., Citation2018).

Self-efficacy is closely related to motivational proclivities, including motivational mindsets or mental frameworks for assigning meanings to events and can enhance motivation (Burnette et al., Citation2020; Luszczynska et al., Citation2005). Two motivational mindsets that have received greater attention by researchers are growth mindset and persistence. Persistence is defined as intentional and continued action towards a particular goal and is similar to the concept of grit which combines persistence with passion for goal attainment (Duckworth & Quinn, Citation2009; Lufi & Cohen, Citation1987). Growth mindset represents a set of beliefs that intelligence or personality are human attributes that can change across the lifespan through effort, practice, and education (Dweck, Citation2016). In contrast, a fixed mindset is a set of beliefs that human attributes are fixed qualities that cannot be changed (Burnette et al., Citation2020). Growth mindset has been associated with well-being outcomes whereas a fixed mindset has been associated with helplessness and resistance to confronting challenges (Dweck, Citation2016; Dweck & Yeager, Citation2019).

Motivational mindsets are correlated with self-efficacy and can together can be important protective factors for internalising and externalising symptoms (Schleider et al., Citation2015). These mindsets vary across a range of attributes and abilities and may be situationally dependent (type of stressors encountered) and context dependent (environmental factors shaping perceptions of stress). Mindsets are believed to buffer against the negative impact of adverse life experiences and perceptions of self-efficacy can empower individuals to be able to cope with stressors (De Castella et al., Citation2014). Self-efficacy is associated with individual task choices, effort, self-regulation, and achievement (Bandura et al., Citation1999; Luszczynska et al., Citation2005; Schunk & Meece, Citation2006). Both self-efficacy and mindset are important factors to understanding how individuals perceive themselves, express emotions, and make behavioural choices.

The protective effects of motivational mindsets and self-efficacy on mental health are tied to individual self-appraisal of these measures and may be shaped by social norms and expectations. Previous research has found significant gender differences in self-efficacy, with girls reporting lower levels of emotional self-efficacy than boys (Muris, Citation2001). Previous systematic reviews have shown that girls often face more restrictions in voice and personal agency than boys, with feelings of restriction increasing with the onset of puberty (Kågesten et al., Citation2016). Changes in gender roles often shift during the pubertal transition, highlighting the importance of targeting protective factors during early adolescence to reduce gender disparities that amplify in mid- to late-adolescence.

While research has examined the mediating role of self-efficacy in response to risk factors, additional research is needed to study the mediating role of self-efficacy from protective factors. Representation of evidence from low-resource populations in the global south are important because in low-resource populations, risk factors may be more difficult to modify than protective factors. This study hypothesises that self-efficacy will mediate the protective effect of growth mindset and persistence on anxiety, depression, and externalising behaviours and these effects will vary by gender during early adolescence. Specifically, we hypothesise that mediation effects will reduce internalising symptoms in girls (depression and anxiety) and externalising symptoms in boys.

Methods

Study procedures and sample selection

This study utilised data collected from Discover Learning, a three-arm comparative effectiveness trial of an intervention to support early adolescents’ social emotional skills and mindsets. Participants were recruited from the peri-urban Temeke Municipality in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Approximately 14.9 million people in Tanzania live below the international poverty line of USD $1.90 per day (World Bank, Citation2019). Dar es Salaam is Tanzania’s largest city and rapidly growing with a population of about 7.4 million people as of 2022 (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2022). Urban areas like Dar es Salaam have experienced the greatest decline in poverty in conjunction with improvements in living conditions and electricity between 2012 and 2018 (World Bank, Citation2019). However, human capital remained low in these areas with a Human Capital Index of 0.4 in 2018 (World Bank, Citation2019).

A detailed study protocol of the Discover parent study can be found in a separate publication, which includes additional information regarding the successive three-arm trial, participant recruitment, and eligibility conditions (Cherewick et al., Citation2020). Results indicate that 66.6% of participants lived with both parents, 33.4% lived with one parent and the mean household size was 5.7 (SD = 2.6) (Cherewick et al., Citation2021). The Tanzanian poverty scorecard was used to estimate socioeconomic status with higher scores indicating higher wealth (Schreiner, Citation2012). In this sample, the mean score on the Tanzanian poverty scorecard was 61.4 (SD = 11.6), with a possible range of 0–71 (Cherewick et al., Citation2021). Analyses were performed using a sample of 579 young adolescents (309 girls and 270 boys) ages 9–12 years (mean age = 10.48; SD = 0.55). Written consent from parents/caregivers and verbal assent from all adolescent participants were provided before the survey was administered, which took approximately 45-60 min to complete. Participants were compensated appropriately with a gift of a notebook and pencil (valued at less than USD $2) based on consultations with the research team, teachers, caregivers, and community members. The data used in this study was collected at baseline prior to the Discover intervention in June-July 2019. This study presents a cross-sectional view of associations between measures of self-efficacy, persistence, growth mindset, and internalising/externalising symptoms.

Survey measures

All participants completed a survey at baseline, prior to implementing the Discover Learning intervention. Survey questions included demographic measures (e.g. age, gender), social emotional mindsets and skills (e.g. self-efficacy, persistence, growth mindset), and psychological assessment (i.e. anxiety, depression, externalising behaviours). Measurement scales were selected based on their use in previous studies of adolescent populations in low- and middle-income countries and were adapted for the age range of the participants.

Self-efficacy questionnaire for children

Self-efficacy was measured using the Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for Children (SEQ-C) scale (Muris, Citation2001). Participants responded to 24 items measuring three different dimensions of self-efficacy: academic, social, and emotional. Participants rated how well each statement describes them using a 5-point scale (1 = ‘Not at all’, 2 = ‘A little bit’, 3 = ‘About average’, 4 = ‘Well’, 5 = ‘Very well’). Average scores were generated, with higher scores indicating greater levels of self-efficacy. provides the adapted statements of the SEQ-C used in this study’s questionnaire. Internal consistency was acceptable in this study for academic (α = 0.69), social (α = 0.65), and emotional self-efficacy (α = 0.77).

Table 1. Self-efficacy questionnaire for children (SEQ-C).

Growth mindset

Growth mindset was assessed using a combination of items from Dweck’s Theories of Intelligence Scale (Dweck, Citation2013, Citation2016; Ingebrigtsen, Citation2018) and adapted growth mindset oriented items from the California Healthy Kids Survey. Items were adapted for understanding and selected based on the age and context of the study participants. Participants responded to nine items, ranking their agreement with each statement on a 4-point Likert scale of ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’. Items included statements such as: ‘I have a certain amount of intelligence and I really can’t do much to change it’, ‘I can learn new things’, and ‘the harder I work at something, the better I will be at it’. Average scores were generated, with higher scores indicating greater levels of growth mindset. Cronbach’s alpha was α = 0.70 in this sample (Constantine & Benard, Citation2001).

Persistence

Persistence was measured with the Persistence Scale for Children (Lufi & Cohen, Citation1987). Participants responded to 10 items, ranking their agreement with each statement on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = ‘Strongly Disagree’, 2 = ‘Disagree’, 3 = ‘Agree’, 4 = ‘Strongly Agree’). Items included statements such as ‘even if I fail to solve a problem, I try again and again and hope that I will find the solution’, ‘when I read a book, I do not skip any pages’, and ‘I like to finish all my homework on time, even though sometimes it is hard and I’d rather go play’. Average scores across items were generated, with higher scores indicating greater levels of persistence. Cronbach’s alpha indicates good internal reliability (α = 0.66) (Lufi & Cohen, Citation1987).

African youth psychological assessment

The African Youth Psychological Assessment (AYPA) was used to assess how participants internalise (i.e. anxiety, depression) and externalise problems, and is used to measure psychosocial health in African youth (Betancourt et al., Citation2014). The adapted version of this scale used in this study is described in . For each statement, participants were asked to describe how frequently they would display certain behaviours on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = ‘Never’, 2 = ‘Somewhat’, 3 = ‘Often’, 4 = ‘All the time’). Average scores were generated with higher scores indicating greater levels of psychosocial symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha indicates good internal reliability (α = 0.72–0.88) (Betancourt et al., Citation2014).

Table 2. African youth psychological assessment (AYPA).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software Version 17 (StataCorp, Citation2021). Sample characteristics are presented using frequencies and means by sex. Additional variables were examined as potential confounders and assessed for relationships with independent and outcome variables. Descriptive statistics compared each variable included in the structural equation models by gender to test for significant differences. Pearson’s correlations were calculated between all measured variables and tested for significance. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to estimate associations between growth mindset, persistence, and dimensions of self-efficacy on depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours. Model invariance by sex was tested using multi-group structural equation modelling. Examination of SEM model fit indices were used to drive refinement of SEMs and improve model fit. Goodness of fit was evaluated using Chi-square, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the standardised root mean residual (SRMR) (Bentler, Citation1990; Steiger, Citation1980; Tucker & Lewis, Citation1973). The following statistical criteria was used to evaluate model fit: RMSEA < 0.06; CFI > 0.90; TLI > 0.90; and SRMR < 0.08 (Kline & Santor, Citation1999). The maximum likelihood method of estimation was used to estimate the SEM. Modification indices were examined to revise and improve the fit of the model (Kline & Santor, Citation1999).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of California Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB) - (CPHS Protocol Number: 2018-01-10628); in June 2018. The primary local partner in Tanzania, Health for a Prosperous Nation, obtained ethical clearance for these research activities from the National Institute of Medical Research – the local IRB in Tanzania (Ref. NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/2851) in August 2018.

Results

Sample characteristics

Five hundred and seventy-nine (579) adolescents ages 9–12 years were included in the analytic sample of this study (). The sample included 270 boys (46.6%) and 309 girls (53.4%). The mean age of study participants was 10.48 years (SD = 0.55). 172 (29.7%) of participants were in 3rd grade, 261 (45.1%) in 4th grade, and 146 (25.2%) in 5th grade.

Table 3. Sample characteristics (N = 579).

Correlations between key variables are described in . Several variables were statistically significantly correlated, although effect sizes were relatively small. Emotional self-efficacy was negatively correlated with female gender (r = −0.10; p < 0.05). Growth mindset was positively correlated with age (r = 0.09; p < 0.05), academic self-efficacy (r = 0.27; p < 0.001), social self-efficacy (r = 0.31; p < 0.001), and emotional self-efficacy (r = 0.23; p < 0.001). Persistence was positively correlated with female gender (r = 0.10; p < 0.05), academic self-efficacy (r = 0.42; p < 0.001), social self-efficacy (r = 0.34; p < 0.001), emotional self-efficacy (r = 0.34; p < 0.001), and growth mindset (r = 0.38; p < 0.001). Depression was significantly negatively correlated with social self-efficacy (r = −0.11; p < 0.01) and growth mindset (r = −0.17; p < 0.001). Anxiety was significantly negatively correlated with growth mindset (r = −0.12; p < 0.01). Externalising symptoms were significantly negatively correlated with academic self-efficacy (r = −0.34; p < 0.001), social self-efficacy (r = −0.19; p < 0.001), emotional self-efficacy (r = −0.12; p < 0.01), growth mindset (r = −0.16; p < 0.001), and persistence (r = −0.22; p < 0.001).

Table 4. Pearson’s correlations between key variables.

Structural equation models

The structural equation models fitted included variables based on previous research indicating significant relationships with mental health and wellbeing outcomes. Additional variables were tested but were non-significant (number of friends, days missed from school, village violence), and were excluded to achieve a parsimonious model. displays descriptive statistics of included variables by gender. Girls had significantly lower emotional self-efficacy in comparison to boys (β = 1.22; p = 0.013) and higher scores on the persistence measure than boys (β = 0.73; p = 0.021).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics for measured variables.

Initial testing of the SEM examined used the method of maximum likelihood estimation. To obtain the best model, six alternative models were fitted (). First, the hypothesised mediation model was fitted with growth mindset and persistence mediated by academic, social, and emotional self-efficacy on depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours (Model 1). Results of Model 1 indicated model fit was marginally acceptable (χ2 = 1498; df = 27; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.987; TLI = 0.943; RMSEA = 0.073 [90% CI: 0.045, 0.104]; SRMR = 0.033). Next, Model 2 examined invariance by sex using multi-group structural equation modelling that constrained path coefficients to be equal between boys and girls. Model fit indices indicated the SEM was not invariant by sex (χ 2 = 1559; df = 54; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.958; TLI = 0.949; RMSEA = 0.070 [90% CI: 0.053, 0.087]; SRMR = 0.107). For this reason, subsequent SEM models were fitted separately for girls and boys (Models 3-6). The SEM model fitted for boys (Model 3) was inadequate for the TLI and RMSEA (χ2 = 671; df = 27; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.981; TLI = 0.914; RMSEA = 0.087 [90% CI: 0.044, 0.134]; SRMR = 0.039). Examination of modification indices indicated that model fit would be improved by including a direct path from persistence to externalising behaviours. The revised SEM for boys with this direct path (Model 4) resulted in excellent model fit (χ2 = 671; df = 27; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.986; RMSEA = 0.035 [90% CI: < 0.001, 0.097]; SRMR = 0.028). The SEM fitted for girls (Model 5) was acceptable (χ2 = 888; df = 27; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.993; TLI = 0.971; RMSEA = 0.055 [90% CI: < 0.001, 0.102]; SRMR = 0.031). However, examination of modification indices indicated that model fit would be improved with the inclusion of a direct path from growth mindset to depression. The revised model including this direct path (Model 6) improved model fit and resulted in excellent fit as reflected by model fit indices (χ2 = 888; df = 27; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.988; RMSEA = 0.036 [90% CI: < 0.001, 0.093]; SRMR = 0.024).

Table 6. Multigroup SEM model invariance and SEM models by sex.

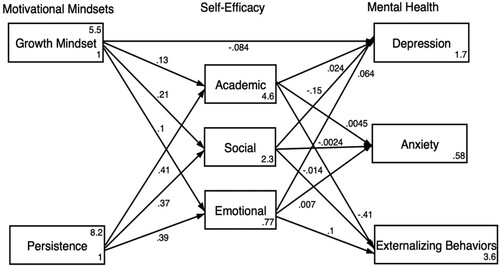

presents the SEM results for girls. presents the standardised path coefficients, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals for the structural paths between latent variables of persistence and growth mindset; dimensions of self-efficacy; and depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours. Academic self-efficacy was positively associated with both growth mindset (β = 0.13; p = 0.021) and persistence (β = 0.41; p < 0.001). Social self-efficacy was associated with growth mindset (β = 0.21; p < 0.001) and persistence (β = 0.37; p < 0.001). Emotional self-efficacy was not associated with growth mindset; however, emotional self-efficacy was positively associated with persistence (β = 0.39; p < 0.001). Academic self-efficacy was found to be associated with lower externalising symptoms among girls (β = −0.41; p < 0.001). Although not statistically significant, modification indices supported inclusion of a negative path of association between growth mindset and depression among girls (β = −0.08; p = 0.079).

Figure 1. Structural equation model for girls. *CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.988; SRMR = 0.024; RMSEA = 0.036.

Table 7. Standardised path coefficients between mindsets, self-efficacy and mental health in girls.

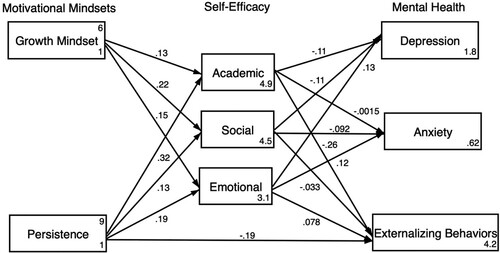

presents the SEM results for boys. presents the standardised path coefficients, p-values, and 95% confidence intervals for the structural paths between latent variables of protective factors; dimensions of self-efficacy; and depression, anxiety, and externalising behaviours among boys. Academic self-efficacy was associated with both growth mindset (β = 0.13; p = 0.028) and persistence (β = 0.32; p < 0.001). Social self-efficacy was associated with both growth mindset (β = 0.22; p < 0.001) and persistence (β = 0.13; p = 0.030). Unlike in the SEM model with girls, for boys, emotional self-efficacy was positively associated with growth mindset (β = 0.15; p = 0.016) and persistence (β = 0.19; p = 0.003). Academic self-efficacy was found to be associated with lower externalising symptoms among boys (β = −0.26; p < 0.001). The direct path between persistence and externalising symptoms was also significant (β = −0.26; p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Structural equation model for boys. *CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.986; SRMR = 0.028; RMSEA = 0.035.

Table 8. Standardised path coefficients between mindsets, self-efficacy and mental health in boys.

Further analysis sought to identify the proportion of the total effect of growth mindset and persistence mediated by self-efficacy on each outcome (depression, anxiety and externalising behaviours) by sex ().

Table 9. Proportion of indirect effect to total effect mediated by self-efficacy on outcomes by sex.

Results indicated that for boys, growth mindset was fully mediated by self-efficacy for all outcomes. Results comparing the indirect to total effect of persistence on outcomes indicated 14% of the total effect of persistence on depression, 100% of the total effect on anxiety and 29% of the total effect on externalising behaviours was mediated by self-efficacy. For girls, self-efficacy fully mediated the effect of persistence on all outcomes. For growth mindset, self-efficacy mediated 20% of the effect on depression and 100% of the effect on anxiety and externalising behaviours.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to explore relationships between motivational mindsets and mental health outcomes and to evaluate the mediating effects of self-efficacy. While previous studies in the United States, Russia, China, and Germany have evaluated the mediating effect of self-efficacy on psychopathology, these studies focus on the mediating effect of self-efficacy resulting from experience of risk factors (e.g. stress and adverse life experiences), finding that higher levels of self-efficacy reduced symptoms of psychopathology (Maciejewski et al., Citation2000; Schönfeld et al., Citation2016). In contrast, the focus of the present study was to evaluate the mediating effect of self-efficacy resulting from protective factors, specifically motivational mindsets. Correlation between persistence and growth mindset in this study (r = 0.38) were similar to correlations found between measurement of grit and growth mindset in previous research (r = 0.27), reinforcing the association between these motivational mindsets (Sigmundsson et al., Citation2020). Evidence evaluating the protective impact of positive characteristics is important because these factors may be more easily modified than risk factors that may be difficult to change (e.g. structural poverty) or impossible to modify if they have already been experienced.

Cultural context, and gender role expectations, have been shown to be key factors to consider when understanding psychological risk and protective factors for anxiety, depression, and externalising symptoms. While evidence suggests the positive effect of self-efficacy on reduced psychopathology in several contexts, additional evidence is needed from diverse contexts to understand how perceived self-efficacy functions as a mechanistic pathway for mental health in different cultures. Researchers posit that differences in perceived self-efficacy may be different in more collectivistic versus individualistic cultures (Bond, Citation1991). Evidence from China suggest that individuals report lower self-efficacy in comparison to more individualistic cultures (Schönfeld et al., Citation2016; Schwarzer et al., Citation1997).

Results from this study indicated differential associations by gender between growth mindset and persistence, mediated by dimensions of self-efficacy on mental health outcomes. In this sample, girls reported lower emotional self-efficacy than boys, and there were no significant differences by sex in academic self-efficacy or social self-efficacy. These finding align with previous research indicating that girls report lower emotional self-efficacy than boys, but have similar academic self-efficacy as boys (Bacchini & Magliulo, Citation2003; Muris, Citation2001). In Tanzania, early adolescent girls have reported greater household responsibilities in comparison to boys and less freedom outside the home which may limit coping strategies such as use of social support systems for emotional self-regulation (Cherewick et al., Citation2021). Gender differences in coping strategies have been explored in other east African cultures that indicate that girls have less freedom to engage with friends and community members outside the home in comparison to boys (Cherewick et al., Citation2015).

Results indicated that there were no gender differences in internalising or externalising symptoms. While much research has indicated that males typically exhibit more externalising symptoms than girls, gender differences in internalising and externalising symptoms emerge in mid- to late-adolescence (Bongers et al., Citation2004; Daughters et al., Citation2009; Hankin et al., Citation2007; Leadbeater et al., Citation1999; Rudolph, Citation2002; Scaramella et al., Citation1999; Telzer & Fuligni, Citation2013). In contrast, during early adolescence, differences in psychopathological symptoms by gender have been shown to be insignificant, highlighting early adolescence as a window of opportunity to target modifiable protective factors such as self-efficacy that are precursors to internalising and externalising problems (Rocchino et al., Citation2017).

In alignment with previous studies, academic self-efficacy was significantly associated with reduced externalising symptoms in both boys and girls. Academic self-efficacy during adolescence has been shown to predict externalising behaviours (Caprara et al., Citation2008) and is related to risk for hyperactivity, impulsivity, and distractibility (Demaray & Jenkins, Citation2011; Rocchino et al., Citation2017; Valle et al., Citation2006). A meta-analysis of self-efficacy by gender has shown males held slightly more academic self-efficacy than females; however, this difference was largest in late adolescence, which again highlights the importance of targeting self-efficacy as a modifiable protective factor during early adolescence (Huang, Citation2013). Academic self-efficacy increases educational attainment but has also been shown to lower depression and increase hope for the future (Bandura & Locke, Citation2003; Roeser et al., Citation2002). Early adolescent interventions should consider schools as a context to promote academic self-efficacy through increased student engagement, afterschool activities, and career exploration (Alt, Citation2015; Forrest-Bank & Jenson, Citation2015; McCoy & Bowen, Citation2015).

Examination of modification indices indicated that model fit was improved with the addition of a direct effect from growth mindset to depression in girls. In boys, examination of modification indices indicated a direct effect from persistence to externalising behaviours. These direct paths indicate that while self-efficacy mediates a portion of the effect from motivational mindsets on psychological symptoms, these mindsets directly affect depression in girls and externalising behaviours in boys. It is plausible that other psychosocial factors such as self-esteem, autonomy, and social support may also mediate the effect of motivational mindsets on mental health.

Given well-established evidence that girls are especially at risk for internalising disorders (depression and anxiety) than boys and that these differences peak during mid- to late-adolescence (ages 13-18), early adolescence (ages 10-12) is an opportunity to reduce gender disparities in mental health that can persist across the life course (Angold et al., Citation1998; Beesdo et al., Citation2009; Beesdo-Baum & Knappe, Citation2012; Caouette & Guyer, Citation2014; Salk et al., Citation2017; Steinberg, Citation2005). Interventions that aim to increase motivational mindsets should consider integrating components that target academic, social, and emotional self-efficacy. Previous evidence suggest the close association between motivational factors and self-efficacy in predicting academic attainment, internalising and externalising symptoms (Caprara et al., Citation2008; Huang, Citation2013). Social emotional learning during adolescence is best supported by opportunities to practice mindsets and skills in different contexts, such as use of social support networks as a coping strategy that could support emotional self-efficacy (Cherewick et al., Citation2020; Shikai et al., Citation2007). Interventions targeting self-efficacy should consider implementation methods designed for use in the home, at school, in peer settings and in the community.

Limitations

This study was limited to cross-sectional data in a sample of early adolescents in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The results of this study may only generalise to similar populations of early adolescents in low-resource collectivistic contexts. Measures of self-efficacy are self-reported and therefore, require self-appraisal that could bias results if study subject’s current mental health limits capacity for self-appraisal or if subjects are motivated to respond to questions in ways that conform to gender norms and expectations. This study measured persistence; however, future studies should explore other similar constructs such as grit which combines persistence with measures of passion and goal setting. Future studies should examine other potential mediators between growth mindset and persistence on psychopathology such as social capital, social identity and autonomy that have been identified in other studies (Bovier et al., Citation2004; Häusser et al., Citation2012; Lai, Citation2009). Finally, the results presented are correlational and the direction of causality between measured constructs requires longitudinal data. Longitudinal data would also allow for identification of sensitive developmental windows to target modifiable protective factors such as self-efficacy and to explore gender differences in trajectories of mental health.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that self-efficacy is an important mediating factor between motivational mindsets and mental health outcomes for both boys and girls. Consistent with previous research, academic self-efficacy is an important target, particularly for universal prevention programmes seeking to modify protective factors that reduce gender disparities in mental health that amplify during mid- to late-adolescence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Health for a Prosperous Nation (HPON) for their work recruiting participants, obtaining consent and assent, and survey administration. Thank you to the Discover National Advisory Board members, Ministry of Education, and Ministry of Health for their support. The authors thank the National Institute of Medical Research in Tanzania (NIMRI) and the University of California Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subjects Institutional Review Board for their guidance, approval, and support. Most of all, the authors thank the adolescents and their parents/caregivers for their participation and support in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the CU Anschutz Digital Collections repository at https://digitalcollections.cuanschutz.edu/work/ns/d9f4ed30-c1cb-4495-8508-6c35d65b6a2a.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, Z. R., Yasien, S., & Ahmad, R. (2014). Relationship between perceived social self-efficacy and depression in adolescents. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 8(3), 65. PMID: 25780377; PMCID: PMC4359727.

- Alt, D. (2015). Assessing the contribution of a constructivist learning environment to academic self-efficacy in higher education. Learning Environments Research, 18(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-015-9174-5

- Andretta, J. R., & McKay, M. T. (2020). Self-efficacy and well-being in adolescents: A comparative study using variable and person-centered analyses. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105374

- Angold, A., Costello, E. J., & Worthman, C. M. (1998). Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine, 28(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329179700593X

- Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., & Giammarco, E. A. (2015). Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 58–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.006

- Bacchini, D., & Magliulo, F. (2003). Self-image and perceived self-efficacy during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(5), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024969914672

- Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Springer.

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.87

- Beesdo, K., Knappe, S., & Pine, D. S. (2009). Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clinics, 32(3), 483–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002

- Beesdo-Baum, K., & Knappe, S. (2012). Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 21(3), 457–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2012.05.001

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bernstein, D. P., Cohen, P., Skodol, A., Bezirganian, S., & Brook, J. S. (1996). Childhood antecedents of adolescent personality disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.7.907

- Betancourt, T. S., Yang, F., Bolton, P., & Normand, S. L. (2014). Developing an African youth psychosocial assessment: An application of item response theory. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(2), 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1420

- Birmaher, B., Ryan, N. D., Williamson, D. E., Brent, D. A., Kaufman, J., Dahl, R. E., Perel, J., & Nelson, B. (1996). Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(11), 1427–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011

- Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Bongers, I. L., Koot, H. M., Van Der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004). Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 75(5), 1523–1537. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x

- Bovier, P. A., Chamot, E., & Perneger, T. V. (2004). Perceived stress, internal resources, and social support as determinants of mental health among young adults. Quality of Life Research, 13(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000015288.43768.e4

- Burnette, J. L., Knouse, L. E., Vavra, D. T., O'Boyle, E., & Brooks, M. A. (2020). Growth mindsets and psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101816

- Caouette, J. D., & Guyer, A. E. (2014). Gaining insight into adolescent vulnerability for social anxiety from developmental cognitive neuroscience. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2013.10.003

- Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 227. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.20.3.227

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2022). Tanzania. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/tanzania/.

- Cherewick, M., Kohli, A., Remy, M. M., Murhula, C. M., Kurhorhwa, A. K. B., Mirindi, A. B., Bufole, N. M., Banywesize, J. H., Ntakwinja, G. M., & Kindja, G. M. (2015). Coping among trauma-affected youth: A qualitative study. Conflict and Health, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-015-0062-5

- Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., & Dahl, R. E. (2020). An intervention to enhance social, emotional, and identity learning for very young adolescents and support gender equity: Protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 9(12), e23071. https://doi.org/10.2196/23071

- Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., Richards, L., Njau, P. F., & Dahl, R. E. (2021). Promoting gender equity in very young adolescents: Targeting a window of opportunity for social emotional learning and identity development. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12278-3

- Comunian, A. L. (1989). Some characteristics of relations among depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69(3-1), 755–764. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1989.69.3.755

- Constantine, N. A., & Benard, B. (2001). California healthy kids survey resilience assessment module: Technical report. Journal of Adolescent Health, 28(2), 122–140.

- Daughters, S. B., Reynolds, E. K., MacPherson, L., Kahler, C. W., Danielson, C. K., Zvolensky, M., & Lejuez, C. (2009). Distress tolerance and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The moderating role of gender and ethnicity. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.001

- De Castella, K., Goldin, P., Jazaieri, H., Ziv, M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion beliefs in social anxiety disorder: Associations with stress, anxiety, and well-being. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12053

- Demaray, M. K., & Jenkins, L. N. (2011). Relations among academic enablers and academic achievement in children with and without high levels of parent-rated symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. Psychology in the Schools, 48(6), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20578

- Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

- Dweck, C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review, 13(2), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315783048

- Dweck, C. S. (2013). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315783048

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

- Ehrenberg, M. F., Cox, D. N., & Koopman, R. F. (1991). The relationship between self-efficacy and depression in adolescents. Adolescence, 26(102), 361.

- Forrest-Bank, S. S., & Jenson, J. M. (2015). The relationship among childhood risk and protective factors, racial microaggression and ethnic identity, and academic self-efficacy and antisocial behavior in young adulthood. Children and Youth Services Review, 50, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.01.005

- Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development, 78(1), 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x

- Häusser, J. A., Kattenstroth, M., van Dick, R., & Mojzisch, A. (2012). “We” are not stressed: Social identity in groups buffers neuroendocrine stress reactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.020

- Huang, C. (2013). Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0097-y

- Ingebrigtsen, M. (2018). How to measure a growth mindset. A validation study of the implicit theories of intelligence scale and a novel Norwegian measure. UiT Norges arktiske universitet.

- Kågesten, A., Gibbs, S., Blum, R. W., Moreau, C., Chandra-Mouli, V., Herbert, A., & Amin, A. (2016). Understanding factors that shape gender attitudes in early adolescence globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PloS one, 11(6), e0157805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157805

- Kannangara, C. S., Allen, R. E., Waugh, G., Nahar, N., Khan, S. Z. N., Rogerson, S., & Carson, J. (2018). All that glitters is not grit: Three studies of grit in university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01539

- Kashdan, T. B., & Roberts, J. E. (2004). Social anxiety's impact on affect, curiosity, and social self-efficacy during a high self-focus social threat situation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(1), 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000016934.20981.68

- Kline, R. B., & Santor, D. A. (1999). Principles & practice of structural equation modelling. Canadian Psychology, 40(4), 381. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092500

- Kwasky, A. N., & Groh, C. J. (2014). Vitamin D, depression and coping self-efficacy in young women: Longitudinal study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(6), 362–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.010

- Lai, J. C. (2009). Dispositional optimism buffers the impact of daily hassles on mental health in Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(4), 247–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.03.007

- Leadbeater, B. J., Kuperminc, G. P., Blatt, S. J., & Hertzog, C. (1999). A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology, 35(5), 1268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268

- Lufi, D., & Cohen, A. (1987). A scale for measuring persistence in children. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(2), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5102_2

- Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590444000041

- Maciejewski, P. K., Prigerson, H. G., & Mazure, C. M. (2000). Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms: Differences based on history of prior depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.4.373

- McCoy, H., & Bowen, E. A. (2015). Hope in the social environment: Factors affecting future aspirations and school self-efficacy for youth in urban environments. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0343-7

- Muris, P. (2001). A brief questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy in youths. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(3), 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010961119608

- Muris, P. (2002). Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 32(2), 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00027-7

- Rocchino, G. H., Dever, B. V., Telesford, A., & Fletcher, K. (2017). Internalizing and externalizing in adolescence: The roles of academic self-efficacy and gender. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 905–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22045

- Roeser, R. W., Strobel, K. R., & Quihuis, G. (2002). Studying early adolescents’ academic motivation, social-emotional functioning, and engagement in learning: Variable-and person-centered approaches. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 15(4), 345–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061580021000056519

- Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4

- Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000102

- Sandin, B., Sánchez-Arribas, C., Chorot, P., & Valiente, R. M. (2015). Anxiety sensitivity, catastrophic misinterpretations and panic self-efficacy in the prediction of panic disorder severity: Towards a tripartite cognitive model of panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 67, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.005

- Scaramella, L. V., Conger, R. D., & Simons, R. L. (1999). Parental protective influences and gender-specific increases in adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 9(2), 111–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0902_1

- Schleider, J. L., Abel, M. R., & Weisz, J. R. (2015). Implicit theories and youth mental health problems: A random-effects meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 35, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.11.001

- Schönfeld, P., Brailovskaia, J., Bieda, A., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. (2016). The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: Mediation through self-efficacy. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.08.005

- Schreiner, M. (2012). A simple poverty scorecard for Tanzania: Poverty-assessment tool Tanzania. simplepovertyscorecard.com/TZA_2007.

- Schunk, D. H., & Meece, J. L. (2006). Self-efficacy development in adolescence. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents, 5(1), 71–96.

- Schwarzer, R., Bäßler, J., Kwiatek, P., Schröder, K., & Zhang, J. X. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01096.x

- Shikai, N., Uji, M., Chen, Z., Hiramura, H., Tanaka, N., Shono, M., & Kitamura, T. (2007). The role of coping styles and self-efficacy in the development of dysphoric mood among nursing students. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(4), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-007-9043-3

- Sigmundsson, H., Haga, M., & Hermundsdottir, F. (2020). The passion scale: Aspects of reliability and validity of a new 8-item scale assessing passion. New Ideas in Psychology, 56, 100745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2019.06.001

- StataCorp. (2021). Stata statistical software: Release 17. In StataCorp, LLC.

- Steiger, J. H. (1980). Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. The annual meeting of the Psychometric Society. Iowa City, IA.

- Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005

- Tahmassian, K., & Anari, A. (2009). The relation between domains of self-efficacy and depression in adolescence.

- Telzer, E. H., & Fuligni, A. J. (2013). Positive daily family interactions eliminate gender differences in internalizing symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(10), 1498–1511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9964-y

- Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291170

- Valle, M. F., Huebner, E. S., & Suldo, S. M. (2006). An analysis of hope as a psychological strength. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.03.005

- Wigelsworth, M., Qualter, P., & Humphrey, N. (2017). Emotional self-efficacy, conduct problems, and academic attainment: Developmental cascade effects in early adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1180971

- World Bank. (2019). Tanzania mainland poverty assessment. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33031.