ABSTRACT

Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) constitute almost 20% of the Israeli population. Despite having access to one of the most efficient healthcare systems in the world, PCI have shorter life expectancy and significantly worse health outcomes compared to the Jewish Israeli population. While several studies have analysed the social and policy determinants driving these health inequities, direct discussion of structural racism as their overarching etiology has been limited. This article situates the social determinants of health of PCI and their health outcomes as stemming from settler colonialism and resultant structural racism by exploring how Palestinians came to be a racialized minority in their homeland. In utilising critical race theory and a settler colonial analysis, we provide a structural and historically responsible reading of the health of PCI and suggest that dismantling legally codified racial discrimination is the first step to achieving health equity.

Introduction

With a growing body of medical and public health literature seeking to elucidate upstream drivers of population health, critical analyses of colonisation and racism are gaining increased attention (Jones, Citation2002; Krieger, Citation2012a; Whyte, Citation2016). When structural or political drivers of Palestinian health are discussed, particularly by those living outside of Palestine/Israel, the focus has primarily been on those living in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) (Lancet Palestine Health Alliance, Citation2019; Rosenthal, Citation2020). This obscures the lived experiences and distinct settler colonial fate of Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) (Rouhana & Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2015; Tatour, Citation2019), who have often been subjected to the analytical lens of minority health as ‘Israeli Arabs’ (Muhsen et al., Citation2017), siloed from structural analyses of health outcomes in the oPt and the Palestinian diaspora, and excluded from discussions of indigenous population health (Asi et al., Citation2022; Tanous, Citation2023). Despite inclusion of PCI within what is considered one of the most efficient health care systems in the world (Clarfield et al., Citation2017), structural determinants – the policies, systems, and institutions that shape health (Harvey et al., Citation2020) – remain the primary drivers of health inequities in Israel (Daoud, Citation2021; Morse & Wispelwey, Citation2018; Tanous, Citation2023), as they are elsewhere in the world. Structural racism is a well-described driver of health inequities within states (Bailey et al., Citation2017; Ramos et al., Citation2022; Thurber et al., Citation2022), but this framework has been insufficiently utilised in Israel, despite persistent and ongoing racial disparities in health, especially among PCI.

Health inequities among PCI have been described for decades, including in several publications by the Israeli Ministry of Health (Ministry of Health, Citationn.d.; MoH, Citation2018). Yet these publications do not address the root causes of inequities in the social determinants of health (SDOH), including structural racism as a driving force, and have instead focused on recommendations within the health system. Previous studies of PCI health inequities have focused on a range of social and structural issues including education inequalities (Daoud et al., Citation2009), poverty and associated poor living conditions (Daoud et al., Citation2012a; Daoud, Soskolne, et al., Citation2018c), patriarchy in Arab-Islamic society (Daoud, Citation2008), interpersonal discrimination (Daoud, Gao, et al., Citation2018b), including intersectional and gendered discrimination (Daoud et al., Citation2019), forced family separation (Daoud, Alfayumi-Zeadna, et al., Citation2018a), neighbourhood violence and segregation (Daoud et al., Citation2020), home demolitions (Daoud & Jabareen, Citation2014), internal displacement (Daoud et al., Citation2012b), and limited access to healthcare and the need for culturally appropriate interventions (Baron-Epel et al., Citation2007; Daoud, Citation2008). Even when these social and structural determinants have been utilised to examine inequitable outcomes, however, racism has not been explicitly invoked in the literature aside from a few recent examples (Daoud, Citation2021; Daoud et al., Citation2022).

This is a significant exclusion. Failing to name racism provides space for flawed interpretations assigning ethnicity, culture, behaviour, or an inappropriately biologized understanding of race – rather than racism – as the relevant risk factors (Boyd et al., Citation2022), a common practice within the extant literature on PCI health inequities in Israel as has been comprehensively noted by scholars like Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian and Hatim Kanaaneh (Kanaaneh, Citation2017; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2016a; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2019). Because the purpose of describing racial health inequities is to ultimately change them, utilising the most accurate framework is crucial for designing appropriate interventions. Naming racism as the root cause radically reconfigures potential solutions, which might otherwise tend to be superficial, race-blind, or victim-blaming rather than transformative. When utilising a critical analysis of the root causes of health inequity in Israel – settler colonialism and resultant structural racism – the inadequacy of many existing explanations for worse health outcomes becomes clear, and prior research highlighting social determinants of PCI health that lack explicit discussions of racism can and should be recast as evidence of its pervasiveness.

We follow Zinzi Bailey and colleagues (Bailey et al., Citation2017) in utilising Nancy Krieger’s definition of structural racism as ‘the totality of ways in which societies foster [racial] discrimination, via mutually reinforcing [inequitable] systems … (eg, in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, etc) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources’ (Krieger, Citation2014).

In order to reposition PCI health inequities within a structural racism framework, this article aims to critically examine: (a) Palestinian racialisation within a settler colonial context, (b) primary manifestations of structural racism in Israel, and (c) health consequences of structural racism for PCI. We conclude by arguing that challenging structural racism in Israel necessitates fostering broad-based social movements for change and dismantling legally enshrined racial oppression as prerequisites for achieving health equity. Following Bailey and colleagues (Bailey et al., Citation2017), we did not undertake an overarching search strategy but instead drew on our collective experience and tripartite purpose (a, b, c above) to determine specific searches in a review of the published literature.

Palestinian citizens of Israel

Political Zionism, a self-described colonial movement originating in late nineteenth century Europe, succeeded in establishing the State of Israel within historic Palestine in 1948 (Khalidi, Citation2020). While the idea that Europeans could and should settle anywhere was common sense at the time of political Zionism’s establishment (El-Haj, Citation2010), Israel’s colonial reality is now downplayed or denied by supporters in response to colonialism’s ever-worsening reputation and increasing calls for decolonial approaches in global health and beyond (Hirsch, Citation2021; Horton, Citation2021). In academic scholarship, the settler colonial framework has been extensively applied to the state of Israel over the last half-century (Mamdani, Citation2020; Pappé, Citation2006; Rodinson, Citation1973; Rouhana, Citation2021; Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2021; Sayegh, Citation2012; Veracini, Citation2020; Wolfe, Citation2006; Zreik, Citation2016) with limited academic challenge (Penslar, Citation2007). As with all settler colonial movements, Zionism sought to create a separate settler polity and to displace and replace the native inhabitants of the land. The vast majority of Palestinians were driven out of their homeland with Israel’s creation or fled violence and were barred reentry, while approximately 150,000 remained (Bishara, Citation2017; Khalidi, Citation2020; Pappé, Citation2006; Rouhana & Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2015; Tatour, Citation2019). They, along with their descendants, are known today as Palestinian citizens of Israel (PCI) and are a sizeable minority at nearly 20% of the population and more than 1.5 million peopleFootnote1 (Robinson, Citation2021). PCI were uniquely subjected to military rule between 1948 and 1966 with restrictions on movement (Rouhana & Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2015; Tatour, Citation2019) and confiscation of their lands (Falah, Citation2020; Saabneh, Citation2021) and continue to exist as a racialized minority.

The health impacts of settler colonialism – an ongoing structure of displacement and replacement of native populations rather than a singular past event (Wolfe, Citation2006) – among Palestinians are increasingly being described and taught in public health settings (Asi et al., Citation2022; Bouquet et al., Citation2022; Daoud, Citation2021; Physicians for Human Rights & Zochrot, Citation2021; Qato, Citation2020; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2016a; Tanous, Citation2023; Tanous & Eghbariah, Citation2022; Tanous, Wispelwey, et al., Citation2022; Yacobi & Milner, Citation2021). The impacts of settler colonialism on Palestinian health share clear parallels with those of indigenous populations in settings such as Australia and North America (Gracey & King, Citation2009; Paradies, Citation2016; The Lancet, Citation2021).

Palestinian racialization in Israel

1 . Does race exist in Israel?

The issue of race in Israel is not commonly understood, and so before discussing the health impacts of structural racism on PCI, we must briefly engage with the emerging literature on Palestinian racialisation utilising tenets from critical race theory and settler colonial studies. Critical race theorist David Theo Goldberg details how racial construction in Israel has traditionally been eschewed as a means of understanding social difference, ‘[f]or where no race, no racial harm. So no racism’ (Goldberg, Citation2009). The inherently racial dimensions of Israel’s self-definition as a Jewish state have been obscured by the desire, following the historical intensity of European antisemitism and its ongoing global manifestations, to reject race in the Israeli context. Yet Palestinian racialisation remains undeniable given their treatment as ‘a despised and demonic racial group’ (Goldberg, Citation2009), a state of affairs reflected in a 2016 poll revealing that nearly half the Jewish Israeli population supports the expulsion of PCI from the country (Farzan, Citation2021).

One result of Israel’s ‘racist domination in the name of racial denial’ (El-Haj, Citation2010) is that race in this context has been undertheorized until very recently. While somewhat more heavily described within the state’s ethnically and culturally diverse Jewish populations (Abusneineh, Citation2021; Lavie, Citation2018; Shohat, Citation1988), fewer scholars have utilised the lens of race when considering Palestinians (Lentin, Citation2017). In the medical literature, scholarly work on race is almost absent in the descriptions of health inequities experienced by PCI, who are often flattened and reduced within discussions on ‘minority health’ (Asi et al., Citation2022; Tanous, Citation2023). Instead, this literature contains a preponderance of cultural and behaviourist theories regarding health disparities – what physician-anthropologist Paul Farmer terms ‘immodest claims of causality’ (Farmer, Citation2001) – that perpetuate rather than elucidate or challenge Israel’s structural racism (Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2016a).

A significant number of papers also elucidate the social and structural determinants of PCI health, but these predominantly focus on ethnicity or religion when describing structural, institutional, or interpersonal discrimination (Daoud et al., Citation2012b; Daoud et al., Citation2020; Daoud, Gao, et al., Citation2018b; Daoud, Soskolne, et al., Citation2018c; Osman et al., Citation2018). In utilising critical race theory, Ronit Lentin, who has undertaken the most extensive analysis of the Israeli racial regime, argues that the more common use of ethnicity to describe Jewish-Palestinian difference is misplaced, as both groups contain ethnic heterogeneity, and ethnicity fails to account for the racial aspects of Israeli settler colonialism (Lentin, Citation2017).

2. Let’s talk about race

It has become well established that race is socially, rather than biologically or genetically, constructed. However, this assertion on its own fails to clarify how and why groups are racialized. Groups are not initially targeted as races, but races are instead ‘made in the targeting’ of peoples for exploitative or colonial purposes (Wolfe, Citation2006), or, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues, ‘If race has no essence, racism does’ (Gilmore, Citation2010). Race can therefore be understood as a ‘trace of history,’ since racialisation acts to reflect, justify, and reproduce – into the present – the unequal relationships engendered by historical processes of colonisation and domination (Wolfe, Citation2016).

In their role in reifying colonial relations, racial hierarchies further certain state and societal objectives, whether it be the land dispossession and elimination of native populations that characterise settler colonial polities (Wolfe, Citation2006), or the subjugation of populations for economic gain as seen in chattel slavery and its aftermath (Mamdani, Citation2020). Such historical processes determine power relations between social groups and thus have far reaching consequences for the political (Giacaman, Citation2020; Ottersen et al., Citation2014) and social determinants of health (Magnan, Citation2017). Israel is no exception in this regard, and any meaningful inquiry into the health of PCI must engage with their racialisation.

3. Let’s talk about race … In Israel

Nadia Abu El Haj argues that Israel’s racial rule over Palestinians is structured by ‘the organization of the state around the distinction between Jew and non-Jew, military and civilian legal systems, enclosure and movement and, since the 1967 war, the additional distinction between citizen and subject’ (El-Haj, Citation2010). Decades earlier, Hannah Arendt wrote that ‘the division between Jews and all other peoples, who are to be classed as enemies, does not differ from other master race theories’ (Wiese & Christian, Citation2012).Footnote2

In her study of racialisation within the Israeli context, Ronit Lentin concludes that

‘[r]acialization is a technology of the state. It operates by producing a series of distinctions relating to origin, kinship, and lineage, as well as by linking physical characteristics to cognitive abilities, cultural norms, and modes of behavior. Its objective is to propel processes of differentiation and hierarchization in order to facilitate modes of governance and control’ (Lentin, Citation2017 quoted in Gordon, Citation2019).

Palestinian racialisation resulting from colonial policies can be traced back at least to the Balfour Declaration of 1917, when the British Government regarded Zionist settlers, a small minority in Palestine at the time, ‘people awaiting a national homeland.’ On the other hand, Palestinians, the vast majority and indigenous inhabitants of the land, were negatively defined by what they were not; i.e. as non-Jewish communities with civil and religious rights, but not political or territorial rights to the land (Tanous, Citation2023). The policies of the British Mandate, and later the state of Israel fall under Camara Jones’s definition of structural racism as a ‘system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on … ’race,’ that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities and undermines realization of the full potential of the whole society through the waste of human resources’ (Jones, Citation2002).

This system of structuring hierarchies of opportunity and value has dominated and shaped Palestinian life ever since, not only in the liberal sense of individual or collective rights of citizens in a state (i.e. ‘Who gets what?’), but in the basic organising logic of the state that aims to create and maintain a racial majority and minority (i.e. ‘Who can stay here and become a citizen? Which migrants are welcomed and may become citizens? Who cannot return?’). Goldberg has distinguished the specific nature of Palestinians’ racial construction as ‘racial palestinianization’ (Goldberg, Citation2009), and while the term is premised first and foremost on the settler colonial clearance of Palestinians from the land, its core determining factor for PCI is Israel’s unique and exclusionary citizenship regime. The rights of sovereignty and self-determination belong exclusively to one group, an already existing reality that was formalised with the so-called Jewish nation-state law in 2018 (Knesset, Citation2018). This racial definition and organising of the nation and the nation-state has driven the minoritization of Palestinians (Tanous, Citation2023) by ethnic cleansing, expulsion (Pappé, Citation2006) and prohibiting the return of Palestinian refugees (Robinson, Citation2013).Footnote3 For the subject of our paper, Palestinians who remained in their homeland and became citizens in the new state developed on it, it is this racializing logic that keeps them outside the borders of the ‘nation’ or from being included within ‘the people of Israel’ (Tanous, Wispelwey, et al., Citation2022). Thus, immediately after the declaration of statehood, the young Jewish state put its non-Jewish citizens under military rule for 18 years, confiscated most of their land and converted it to state land, and created an underclass of an impoverished, less educated, and otherwise marginalised minority (Sultany, Citation2012). These processes, in which racialisation is the ‘organizing grammar’ (Stoler, Citation1995) of colonial dispossession and exploitation, determine every aspect of the life of PCI and shape the political and social determinants of health, as we detail below. As in other settler colonial contexts, the Israeli legal system has been instrumental in concretising and maintaining Palestinian racialisation.

Legal status of Palestinian citizens of Israel

The linchpin connecting racialisation of PCI and their social health determinants is their subordinate legal and national status. Citizenship in Israel is bifurcated into citizenship and nationality, with the latter distinguishing between Jews and Arabs (Jabareen & Bishara, Citation2019). As Lana Tatour argues, citizenship itself became a tool for domination and race construction, differentiating between the settlers, regarded as natural and authentic citizens, and the indigenous, regarded as naturalised aliens and guests in their homeland (Tatour, Citation2019). This is reflected in the early laws of the state that defined who can and who cannot become a citizen. The ‘Law of Return’ of 1950, for example, allows every Jewish person to immigrate to Israel, while Palestinians that were born in the land that is now defined as Israel and were expelled during the Nakba do not have that right (Adalah, Citation2017c). The ‘Citizenship Law’ of 1952 states that every immigrant under the law of return can automatically become a citizen of Israel and deprives expelled Palestinians who were residents of Palestine prior to 1948 the right to citizenship (Adalah, Citation2017b; Jabareen & Bishara, Citation2019). The ‘Absentees’ Property Law’ of 1950 allowed the state to transfer the belonging of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) into state control, becoming a main tool for land dispossession (Adalah, Citation2017a). These laws were pivotal in defining the borders of citizenship and casting the minority status of PCI and their land ownership.

In 2018, the Knesset passed the Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People. The law explicitly reinforces Jewish supremacy in stating that ‘The State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish people in which it realises its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination … the realisation of the right to national self – determination in the State of Israel is exclusive to the Jewish People.’ It further enshrines settler colonialism as a national goal, determining that ‘The state views the development of Jewish settlement as a national value, and shall act to encourage, and promote its establishment and consolidation’ (Knesset, Citation2018).

According to Adalah, the legal center for Arab minority rights in Israel, PCI continue to face over 65 racist laws that discriminate directly and indirectly against them and impact virtually every aspect of life (Adalah, Citation2017d). Adalah also notes that the new Israeli government, elected in 2022, intends to further entrench Jewish supremacy with planned discriminatory legislation (Adalah, Citation2023). Some laws directly and clearly target PCI, such as the ‘Nakba Law’ that allows the defunding of institutions that commemorate Nakba Day, limiting the freedom of expression and the preservation of history and the identity of Palestinians (Adalah, Citation2011b), and the ‘Ban on family unification law’ that prohibits family unification if one partner is a PCI and the other is a resident of the oPt (Adalah, Citation2003, Citation2022). Other racist laws are discriminatory in intent but ‘worded in a seemingly neutral manner’ (Adalah, Citation2017d). Examples of such laws include the ‘Admission Committee Law’ that legalises the operation of committees to accept or reject individuals from living in hundreds of towns built on state land in the Naqab and Galilee based on thinly veiled criteria like social and cultural suitability and having a ‘Zionist vision’. In practice, those committees filter out PCI applicants (Adalah, Citation2011a), negate any principle of equality and are the building blocks of racial segregation. Other laws that target PCI while using ‘neutral language’ without any mention of Zionism, the Jewish state, or PCI include the ‘NGO funding transparency law’ that requires NGOs that receive more than half of their funding from foreign governments to state that in every publication and discussionFootnote4, and the ‘Increased Governance and Raising the Qualifying Election Threshold Bill,’ enacted in 2014, which raises the threshold needed for parties to enter the Knesset from 2 to 3.25%.Footnote5

Lentin concurs that the legal system has been and continues to be Israel’s primary tool for racializing PCI, with discriminatory laws passed with increasing frequency over the last two decades (Lentin, Citation2017). Upon examination of the legally codified racial discrimination at the levels of state identity and basic law definition, the racism experienced by PCI is therefore distinct from the prevailing racism in countries that have moved in the direction of formal civil and political equality (El-Haj, Citation2010; Goldberg, Citation2015; Jabareen & Bishara, Citation2019; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2016b). Instead,the structural racism in Israel today aligns more closely with that of apartheid South Africa (Al Haq, Citation2022; Amnesty International, Citation2022; Badil, Citation2011; B’Tselem, Citation2021; Erakat, Citation2021; HRW, Citation2021), the Jim Crow era of the American South (Sultany, Citation2009), and the current status of the native nations in the U.S., who lack the full constitutional guarantees of other US citizens and remain subject to the plenary authority and whims of Congress (Mamdani, Citation2020).

Palestinian health inequities in Israel

Racial palestinianization, like anti-Black or anti-indigenous racism in the US, generates a social hierarchy that configures and naturalises structural racism in Israel. Because structural racism inevitably has health consequences, the health inequities of PCI follow a similar pattern to other indigenous populations in settler colonial states (Tanous, Citation2023; Wispelwey et al., Citation2023). PCI on average have a life expectancy 3–4 years shorter than the Jewish Israeli population, a gap that has been widening since the 1990s and is commensurate with the longevity gap between Black and White Americans (Himmelstein et al., Citation2022; Saabneh, Citation2016; Saabneh, Citation2021). More than 90% of Palestinians live in completely segregated towns, which has been linked to higher levels of anxiety (Daoud et al., Citation2020) and shorter life expectancy (Saabneh, Citation2021). Nine out of the ten towns with the highest overall mortality rate in Israel and all ten towns with the highest mortality rate from heart diseases are towns inhabited entirely by PCI (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2020; Tanous, Citation2023).

As seen in , the Palestinian death rate in Israel is 2.96 times higher from motor vehicle injuries, 2.69 times higher for respiratory diseases, 2.25 times higher for diabetes, and 1.85 times higher for hypertension compared to the Jewish population (Chernichovsky et al., Citation2017). The neonatal mortality rate is 2.56 times higher for PCI overall, but this inequity is as high as 3.6 times higher in the south where Palestinian Bedouin communities reside (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2020). PCI have significantly higher age and sex-adjusted diabetes prevalence rates: 18.4% compared to 10.3% among Israeli Jews (Jaffe et al., Citation2017). PCI suffer from heart attacks at a much younger age and survive for fewer years afterward (Karkabi et al., Citation2020). They also have a 5.5 times higher relative risk of death from homicide compared to Israeli Jews (Tanous et al., Citation2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PCI age-adjusted death rate was three times higher than that of the general population in Israel (Efrati, Citation2021).

Table 1 . Age adjusted death rate per 100,000 for Jewish Israeli and Palestinian Citizens of Israel, 2014 (Chernichovsky et al., Citation2017).

This evidence makes clear that the health inequities between PCI and the Israeli Jewish population are pronounced, and as Bailey et al (Bailey et al., Citation2017) have argued in the US context, such disparities require a critical interrogation of the broader structural health determinants and their intersections with racism. In the following section, we describe some of the major social determinants of health that shape the lives of PCI as a product of the discriminatory policies they face as a racialized community in Israel.

Structural racism and the social determinants of health

The public health literature has significantly expanded our understanding of the relationship between health inequities and racism in recent decades, and the focus has increasingly been on how the overarching causes of these inequities are built into systems (Daoud, Gao, et al., Citation2018b; Krieger, Citation2014). Researchers are identifying racism as a structural determinant of health that operates on multiple levels, including by shaping the socioeconomic conditions under which racialized populations live, through institutional discrimination and reproducing socioeconomic disadvantage, and via embodiment mechanisms that include increased stress, unhealthy habits or maladaptive coping (Bailey et al., Citation2017). Exposures can occur continuously over the life course and consequences can transcend an individual’s lifetime to have intergenerational impacts (Paradies, Citation2016). These pathways have negative implications both for health status and for access to and quality of healthcare. Furthermore, structural racism can manifest in various forms, including residential segregation, de jure discrimination, and discriminatory incarceration, among others (Krieger, Citation2012b). Below we discuss a few of the most salient features of structural racism impacting PCI’s health.

While the focus of this paper is not on access to healthcare, it is worth mentioning that, like other SDOH, such factors are not independent of each other, and all are affected by structural racism. Despite the existence of national health insurance and advanced healthcare in Israel, PCI have variable and limited access to these healthcare services due to barriers such as the location of services (primarily located in Jewish Israeli towns), lack of public transportation, limitations in time and resources due to poverty, language barriers, and different access to education on preventive medicine. As a result, Jewish Israelis utilise ambulatory and preventive health care services at more than double the rate as compared to PCI (Filc, Citation2010; PHR-I, Citation2020; Shibli et al., Citation2021).

Land dispossession, exclusion, and segregation

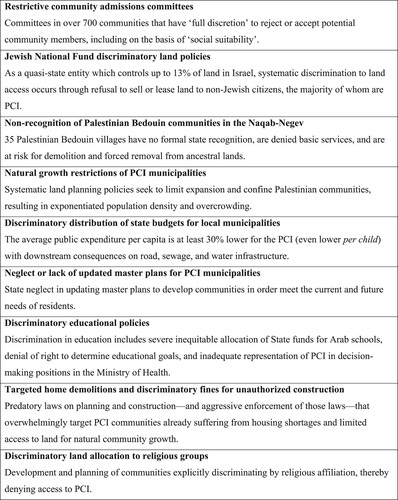

One of the most enduring consequences of structural racism in Israel is the systematic and institutionalised policies of land and housing that discriminate against PCI (Jabareen, Citation2017; Saabneh, Citation2021). Since the establishment of Israel, and over the past 70 years, state policies of land nationalisation have been codified in a series of laws that have effectively confiscated and transferred Palestinian land to the state, restricted expansion of Palestinian communities, and denied PCI access to land (Adalah, Citation2017d; Falah, Citation2003; Jiryis, Citation1973). Most of the land confiscations occurred in the first two decades of the state while PCI were under military rule and could not access their land (Forman & Kedar, Citation2016; Jiryis, Citation1973). Today, 93% of land in Israel is controlled by the state or quasi-state entities, with over 80% of land inaccessible for PCI to purchase or lease based on ‘national belonging’—i.e. their status as non-Jewish citizens in Israel (Hesketh et al., Citation2011). Despite the growth of the PCI population to nearly 20% of the overall population of Israel (CBS, Citation2021), less than 3% of state land falls under PCI local governmental jurisdiction, while the density of PCI communities has increased 11-fold, since 1948, due to population growth and shrinking municipal jurisdictions (The Association for Civil Rights in Israel et al., Citation2017). These long-standing policies have led to extreme spatial sequestration, where 90% of PCI live in completely segregated localities. These localities became defined by overcrowding, lack of master planning, impoverishment, higher crime rates (Tanous et al., Citation2020), and a lower life expectancy (Saabneh, Citation2021; Sultany, Citation2012). summarizes the major discriminatory state policies in land and housing.

While the state has developed over 900 Jewish localities since 1948, the few that have been developed for PCI (The Association for Civil Rights in Israel et al., Citation2017) were part of a policy of displacement. These townships were developed with the intent to consolidate villages and force urbanisation on the Palestinian Bedouin, a subgroup of PCI, thereby removing them from ancestral lands into urban communities (Banna, Citation2011; Swirski & Hasson, Citation2006). While virtually all PCI are affected by racist land and housing policies, some are more affected than others. Almost 30% of PCI are ancestors of internally displaced persons (IDPs) who were expelled from their homes and towns in 1948 but remained within the new state’s borders. Those Palestinian IDPs were forced to rebuild their lives in new towns while their land was seized (Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2022). IDPs report significantly worse health outcomes than those who were not displaced (Daoud et al., Citation2012b).

The Naqab is perhaps the place where structural racism in land policies is most evident. In an attempt to Judaize the Naqab and concentrate Palestinian Bedouins in crowded and impoverished townships, the state operates alternately between organised violence and organised abandonment (Gilmore, Citation2015; Tanous & Eghbariah, Citation2022) through land confiscations, large scale home demolitions, and lack of planning and recognition. According to the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, until 2020, more than 52,000 houses were demolished in the Naqab (The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, Citation2017). Al Araqib village, for example, has been demolished more than 200 times, while the residents continue to rebuild their tents and houses (Middle East Monitor, Citation2022). The state also refuses to provide building permits and passes legislation that negates Palestinian Bedouin claims to land, denoting them as ‘trespassers on state land’ (Adalah, Citation2013; Hesketh et al., Citation2011; Nasasra, Citation2013). As a result, over 35 villages, populating almost 150,000 residents (Ziv, Citation2020), are ‘unrecognized’ by the state and thus denied state services including access to water, electricity, roads, sewage, infrastructure, and local health services (On the Map: The Arab Bedouin Villages in the Negev-Naqab, Citationn.d.). In the Naqab, as in other regions of Israel, these land policies have contributed to detrimental environmental consequences that inequitably affect Palestinian health due to air pollution (Yitshak-Sade et al., Citation2015) (Yitshak-Sade et al., Citation2017), sewage exposure (Kanaaneh et al., Citation1994), and limited or lack of green space (Omer & Or, Citation2005) (Robinson, Citation2019), among others (Berman & Barnett-Itzhaki, Citation2017). The centralised manner in which Israel has confiscated and managed land and water have led to an almost complete land alienation and de-peasantization of Palestinians where their living environment is no longer rural and spacious, nor urban with planned green spaces, thus producing crowded unplanned townships (Tanous, Citation2023). The formal neglect in planning (Falah, Citation2020) with land shortage also creates a reality where industrial workshops are located near residential areas adding to the load of noise and air pollution (Sofer et al., Citation2012).

The recurrent and violent demolitions of individual and community infrastructure leads to housing insecurity and cyclical forms of enduring psychological trauma and depression (Daoud & Jabareen, Citation2014; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Citation2016a; United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Citation2021). The state has continued to prioritise, sponsor, and encourage Jewish settlement in the Naqab, including connecting remote farms on large swaths of land to state utilities (Hamdan, Citation2005) while denying utilities and state recognition to Palestinian Bedouin ‘unrecognized’ villages. Health access is significantly curtailed for these PCI, often as a settler colonial means of coercing them from the land and leading to overrepresentation in acute care hospitals (Wispelwey et al., Citation2019). These settler colonial policies in land and urban planning produce and reproduce health disparities, in part by creating a cycle of racialized stigmatization that is used to justify and consolidate ongoing dispossession (Yacobi & Milner, Citation2021).

Poverty and education

In order to understand the racialized impoverishment of PCI, their positioning within the political economy of settler colonialism is crucial. The Nakba of 1948 destroyed the Palestinian urban centers as cities like Jaffa, Haifa, Lydd and Ramleh were emptied of the majority of their Palestinian residents. The urban elites and middle class were displaced and not allowed to return (Blatman & Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2022; Hasan, Citation2019; Hawari, Citation2019). As a result, most of the Palestinians that remained within the Green Line were peasants in scattered villages. The massive land confiscation during the years of the military rule has transformed those PCI into landless peasants on the geographic and economic margins of the economy.

Most Palestinians in Israel continue to live in segregated towns that are at the bottom of socioeconomic grading. These towns became areas of segregated and racialized poverty and unemployment (Saabneh, Citation2019, Citation2021). Inequitable employment and education opportunities, and differential state welfare policies that discriminate against Palestinians (Hesketh et al., Citation2011; Sultany, Citation2012) lead to the concentration of poverty in racially segregated neighborhoods or towns and result in communities with high crime rates, poor schools, and welfare-dependent residents (Massey & Denton, Citation1993). In 2018, over 53% of PCI were living in poverty as compared to 20% of Jewish-Israelis (The Arab Population in Israel: Facts & Figures, Citation2018, Citation2018). A 2017 report on the socioeconomic index of localities in Israel demonstrated that the vast majority of the Palestinian localities lie in the three lowest levels, out of ten, of socioeconomic stratification, while only three Palestinian localities lie in the upper five clusters (CBS, Citation2020). Furthermore, PCI have much higher rates of food insecurity compared with Jewish Israelis (42.4% in PCI compared with 11.1% among Israeli Jews) (Andelbad et al., Citation2020).

The education system is another area where racism is evident in both structure and content. Palestinian and Jewish schools are largely segregated (Agbaria, Citation2016). Schools serving PCI are significantly underfunded and understaffed (Coursen-Neff, Citation2004) leading to low matriculation and high dropout rates (Haddad Haj-Yehya & Rudnitzky, Citation2018). In addition to segregation and underfunding, public education in Israel is a key tool for building and maintaining ‘colonial educational hegemony’ (Abu-Saad, Citation2018) and has been recently conceptualized as a ‘colonized education’ (Awayed-Bishara et al., Citation2022). Awayed-Bishara and colleagues have shown how the educational apparatus limits what Palestinian youth can express about their identity and experiences, and that the politics of military rule still operates as a discursive regime deeply enshrined in the Palestinian consciousness. The conceptualization of ‘colonized education’ captures how Israel has designed the segregated Arabic-speaking schooling system to de-nationalize, and particularly to de-Palestinize Arab students. The curriculum promotes the Zionist narrative and emphasizes the Jewish national identity, while silencing the Palestinian narrative and denying an indigenous Palestinian Arab history not only in the study of geography and history (Peled-Elhanan, Citation2013), but also in language education (Awayed-Bishara, Citation2015, Citation2020). The Jewish Nation State Law further demoted the status of Arabic language and declared Hebrew as the sole official language (Awayed-Bishara et al., Citation2022). The curriculum assumes Jewish historical rights in Palestinian lands and the importance of maintaining a Jewish majority and the marginalization, control, and dehumanization of Palestinians. It prepares the Palestinian students to accept Jewish superiority and promotes their own social and economic marginalization (Abu-Saad, Citation2018). The Israeli education system thus is structured to be segregated and carry allegiance to nationalist ideologies that reproduce social hierarchies and repression based on race (Agbaria, Citation2016). The curriculum and textbooks often contain either a racist, orientalist, stereotypical representation of the Palestinians, portraying them and their culture in a negative manner (unproductive, backward, untrustworthy), or simply a lack of representation or a ‘blind spot’ of Palestinian representation, thus helping to disseminate racist stereotypes (Peled-Elhanan, Citation2013). Completing a vicious circle, poverty and lower quality primary education reproduces the limited access to higher education and high-earning jobs in segregated PCI communities (Hesketh et al., Citation2011).

Connecting the SDOH and health outcomes

Over the past several decades there has been significant investment in research seeking to understand the complex and multifactorial causal pathways that link the SDOH to health outcomes. The literature has described the relationships between poverty and health outcomes (Wagstaff, Citation2002), cognitive function and substandard housing (Lidsky & Schneider, Citation2003), educational status and mortality (Jemal et al., Citation2008), among others, while also attempting to understand the biological pathways that underlie these relationships (Braveman et al., Citation2011). For Palestinians, the SDOH directly affect health outcomes in ways known and unknown. Examples include educational inequality and impoverishment that have been significantly linked to reports of worse health among PCI (Daoud et al., Citation2009; Daoud, Soskolne, et al., Citation2018c). PCI have been pushed to the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder (Sultany, Citation2012), thus relying on low-paying sectors of the economy such as construction and industries (The Israel Democracy Institute, Citation2011) that carry high occupational health hazards such as falls, injuries, and death (Ben Zeev, Citation2022; Zvi Cohen & Feldman-Gubbay, Citation2020).

Land policies that lead to dispossession, fragmentation, and marginalization disrupt food sovereignty and are related to both communicable (Tanous & Eghbariah, Citation2022) and non-communicable diseases such as obesity and diabetes (Tanous, Citation2023). The ghettoization of PCI in crowded and impoverished towns, combined with state neglect, has been associated with a higher homicide rate and lack of trust in the police to fight crime (Khatib et al., Citation2022; Tanous, Khatib, et al., Citation2022). Those policies also impact the ability to access health facilities, leading to an overrepresentation in acute health care facilities (Wispelwey et al., Citation2019). Self-perceived racism has also been associated with increased psychological distress among young PCI (Tanous, Badarnee, et al., Citation2022) While there may be a relative paucity in the SDOH literature in Palestine (Tanous, Citation2023), there is no reason to believe that these factors do not influence health in similar causal ways, as has been extensively described in many contexts around the world.

Conclusion: achieving health equity for PCI requires dismantling legalized structural racism

In connecting PCI racialization to social determinants of health in Israel, our approach is consistent with the evidence-based premise that racism produces and exacerbates health inequities between racialized populations, and that worse health outcomes for minoritized indigenous populations is not ‘prewritten in genetics ascribed to race or other categorization such as ethnicity and indignity’, but are rather a product of the complex ways structural discrimination shapes our physiology, epigenetics and health (Krieger, Citation2012a; Selvarajah et al., Citation2022).

If health inequities are caused by structures that potentiate racial discrimination, then addressing downstream health inequities without challenging the structures that facilitate them can both limit efficacy and obfuscate their root causes. For example, typical recommendations to eliminate gaps in health outcomes include narrowing the socioeconomic divide between Jewish Israelis and PCI, likening the outcomes of PCI to marginalized Jewish populations within Israel (Chernichovsky et al., Citation2017). Yet the racialized structural barriers that perpetuate these inequities also limit the ability of PCI to engage in efforts to improve their situation to the same degree as their Jewish counterparts. PCI communities are often portrayed as merely underdeveloped and thus in need of a development plan (Khoury et al., Citation2021), rather than historically and politically racialized in a settler colonial context (Sultany, Citation2012) and thus in need of reparations, decolonization, and de-racialization of the entire political structure.

Because the health inequities of PCI are best understood as the consequences of racism that is built into Israel’s settler colonial legal and political systems, the first step in achieving health equity in Israel is dismantling these laws (Agénor et al., Citation2021) and policies: ending legalized supremacy and the associated racial hierarchies. Decolonization and reparations entail the more considerable steps of abolishing racial supremacy via a restorative and reconciliatory process that involves identifying historical responsibilities, attaining justice and truth, and restructuring society and political relationships accordingly (Rouhana, Citation2017; Sabbagh-Khoury, Citation2021; Zreik, Citation2016). Guided by Palestinian civil society, international pressure to ensure Israel conforms with international law and ends its practice and structures of apartheid (Amnesty International, Citation2022; Badil, Citation2011; B’Tselem, Citation2021; HRW, Citation2021; Yesh Din, Citation2020) is an essential starting point, and squarely within the scope of citizens of power-wielding Global North democracies that share close relationships and political leverage with the state of Israel.

Acknowledging and redressing the racist policies and practices impacting PCI is a prerequisite for achieving complete health equity in Israel, but progress can still be achieved in the meantime by supporting the local resistance to the various forms of discrimination discussed above: education, housing, land, family unification, healthcare, employment, research, etc. Regarding the latter, following Nihaya Daoud and colleagues in utilizing CRT and its public health approach (Public Health Critical Race Praxis), as in their recent study of racial segregation in Israeli hospital maternity wards (Daoud et al., Citation2022), will ensure that health equity research is geared toward appropriate knowledge production, action, and accountability (Daoud, Citation2021).

In contrast to Israel, which is increasingly acknowledged to be committing the crime of apartheid (Al Haq, Citation2022; Amnesty International, Citation2022; Badil, Citation2011; B’Tselem, Citation2021; Erakat, Citation2021; HRW, Citation2021), racial inequities in the United States and many other countries with racialized minorities are largely perpetuated by implicit structures, attitudes, and behaviours and the race-blind policies, laws, and institutions that preserve the structural power of white supremacy (Bailey et al., Citation2017). Yet we must understand, recognise and contextualise structural racism and its impacts on health especially as we see a worldwide rise in nationalism, xenophobia, islamophobia and antisemitism (Van Daalen et al., Citation2022). Recent examples include anti-Muslim racism in India (Ahuja & Banerjee, Citation2021; Roy, Citation2022) among other places, racism against the Roma people in Europe (Matache & Bhabha, Citation2020), as well as environmental laws and policies that target Indigenous populations around the globe (Herculano & Pacheco, Citation2008; King et al., Citation2009). Since it is unusual for racially explicit discriminatory policies to still be codified into state law as in Israel, where the definition of the state cements the supremacy of one racial group over another (Lentin, Citation2017), the likelihood of achieving equity through reform or incremental progress within the current system is remote. While the United States must still contend with the consequences of structural racism born from histories of settler colonialism and slavery, it serves as a relevant example that legally enshrined racism can be defeated as a first step toward equity, including health equity, even while decolonial and reparative efforts are still nascent. The ongoing Black and Indigenous freedom struggles are instructive in providing a path forward.

As the world’s first settler colonial state (Mamdani, Citation2015), the United States has witnessed centuries of indigenous resistance to settler colonialism (Estes, Citation2019) and a Black radical tradition of intersectional resistance against enslavement, segregation, mass incarceration, and racial capitalism (Davis, Citation2015; Gilmore, Citation2011; Kelley, Citation2003; Pulido & De Lara, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation1983). Mirroring organizations like the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement – both of which had explicit health-focused programs (Bassett, Citation2016; Lurie, Citation2019) while adopting anti-colonial frameworks (Malloy, Citation2017; Steinman, Citation2015) – the Movement for Black Lives, the indigenous struggle against US settler colonialism and treaty violation at Standing Rock and elsewhere, and broad-based grassroots organizing continue to challenge racial inequities in the US (Calhoun, Citation2021; Cerdeña et al., Citation2020; Churchwell et al., Citation2020; The Lancet, Citation2021; Yancy, Citation2020). This same dynamic, inspired by vibrant social movements, is an essential launching pad for societal understanding and eradication of PCI health inequity.

This paper represents a modest first step in describing the settler colonial racialization of the indigenous Palestinian population as it relates to ongoing health inequities within the state of Israel. By illustrating how these racialized inequities are codified into Israeli law, we argue that the barriers to PCI health equity are more historically and structurally entrenched than has yet been explored in the health equity literature focused on Israel. While the fields of public health and medicine have increasingly described the role of structural racism in perpetuating and creating health inequities, the racialization of Palestinians, and especially those living within the state of Israel, has been insufficiently considered in describing the clear health inequities between this population and the Jewish Israeli majority. This is already changing, however, and it heralds a promising opportunity to generate more robust antiracism and decolonial efforts aiming not only at the possibility for health equity, but for the freedom and equality of all people living between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

Declarations

Availability of data: Not applicable.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Ethics committee approval: Not applicable.

Consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

As part of a collective authorship model, all authors have contributed equally to this manuscript as co-directors of The Palestine Program for Health and Human Rights at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University and the Institute of Community and Public Health at Birzeit University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 While this paper focuses on PCI and not Palestinian residents of occupied East Jerusalem, Palestinians in the rest of the oPt or Palestinian refugees in neighboring countries, it is important to emphasize that these different populations are all Palestinians that Zionist settler colonialism has fragmented to several dismembered geographies and different lived realities(Asi et al., Citation2022). The occupation of the oPt adversely affects the health of PCI. Many PCI are denied family unification (when one of the spouses does not hold an Israeli ID), leading to several health concerns, including a lack of access to Israeli healthcare services for their spouses (Daoud, Alfayumi-Zeadna, et al., Citation2018a; Tanous, Wispelwey, et al., Citation2022). Another less studied field is the effect of the occupation and military aggressions against Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip on the health of PCI due to constant stress, fear and worrying for their people and extended families.

2 This division between Jews and all other people is clearly manifested in the issuing of ID cards for the populations that live under Israeli control. Up until 2005, every Israeli ID card had an ethnicity category stating if the person was Jewish, Arab, Druze, or Bedouin. Palestinians in Jerusalem hold a resident, not citizen, ID card and Palestinians in the oPt carry a green Palestinian ID. Every Jewish person, whether living in Tel Aviv or in a settlement in the West Bank holds a blue Israeli ID card. Reminiscent of the settler colonial pass system developed for US plantations and reservations (Mamdani, Citation2015), this color-coded stratification of ID cards determines much of one’s ability to move, study, work, and live in different places. (Tawil-Souri, Citation2012).

3 Per Hannah Arendt, any state founded on a homogeneous idea of the nation is bound to expel those who do not belong to the nation and so to reproduce the structural relation between the nation state and the production of stateless persons (Butler, Citation2012).

4 This law, while using neutral language, aims to shrink the space of civil society through the targeting of NGOs that are critical of the government, especially organizations focusing on issues related to discrimination, racism, and occupation, most of whom receive grant funding from foreign governments and funds. Right wing and settler organizations that are heavily funded by private foreign donors are not held to the standard of this law (Adalah, Citation2016).

5 The amendment targets and harms PCI, making it specifically challenging for the Palestinian parties, representing the different political ideologies, to successfully contend for seats in the election (Adalah, Citation2014).

Bibliography

- Abu-Saad, I. (2018). Palestinian education in the Israeli settler state: Divide, rule and control. Settler Colonial Studies, 9(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2018.1487125

- Abusneineh, B. (2021). (Re)producing the Israeli (European) body: Zionism, anti-black racism and the depo-provera affair. Feminist Review, 128(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/01417789211016331

- Adalah. (2003). “Ban on family unification” - citizenship and entry into Israel law. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/511.

- Adalah. (2011a). “Admissions committees law” - cooperative societies ordinance - Amendment No. 8 - Adalah. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/494.

- Adalah. (2011b). “Nakba law” - amendment no. 40 to the budgets foundations law - Adalah. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/496.

- Adalah. (2013). The prawer-begin bill and the forced displacement of the Bedouin. http://www.adalah.org/eng/Articles/1080/As-Requested-by-.

- Adalah. (2014). Increased governance and raising the qualifying election threshold – Bill to amend basic law: - adalah. Adalah Racist Laws Database. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/571.

- Adalah. (2016). NGO “Funding transparency” law - Adalah. Adalah Discriminatory Laws Database. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/600.

- Adalah. (2017a). Absentees’ property law. Discriminatory Laws Database. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/538.

- Adalah. (2017b). Citizenship law. Discriminatory Laws Database. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/536.

- Adalah. (2017c). Law of return - adalah. Discriminatory Laws Database. https://www.adalah.org/en/law/view/537.

- Adalah. (2017d, September 25). The discriminatory laws database. https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/7771.

- Adalah. (2022, March 10). Israel reinstates ban on palestinian family unification - adalah. Adalah Website. https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/10576.

- Adalah. (2023). Adalah’s analysis of the new israeli government’s guiding principles and coalition agreements and their implications on Palestinians’ rights. https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/9569/.

- Agbaria, A. K. (2016). The ‘right’ education in Israel: Segregation, religious ethnonationalism, and depoliticized professionalism. Critical Studies in Education, 59(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1185642

- Agénor, M., Perkins, C., Stamoulis, C., Hall, R. D., Samnaliev, M., Berland, S., & Bryn Austin, S. (2021). Developing a database of structural racism–related state laws for health equity research and practice in the United States. Public Health Reports, 136(4), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920984168

- Ahuja, K. K., & Banerjee, D. (2021). The “Labeled” side of COVID-19 in India: Psychosocial perspectives on islamophobia during the pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 604949. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.604949

- Al Haq. (2022). Israeli apartheid, tool of Zionist settler colonialism. www.alhaq.org.

- Amnesty International. (2022). Israel’s apartheid against Palestinians: A cruel system of domination and a crime against humanity. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/02/israels-apartheid-against-palestinians-a-cruel-system-of-domination-and-a-crime-against-humanity/.

- Andelbad, M., Karadi, L., Pins, R., & Ksir, N. (2020). Measurements of poverty and income inequalities. https://www.btl.gov.il/Publications/oni_report/Documents/oni2020.pdf.

- Asi, Y. M., Hammoudeh, W., Mills, D., Tanous, O., & Wispelwey, B. (2022). Reassembling the pieces: Settler colonialism and the reconception of Palestinian health. Health and Human Rights, 24(2), 229–235. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36579318/

- Awayed-Bishara, M. (2015). Analyzing the cultural content of materials used for teaching English to high school speakers of arabic in Israel. Discourse & Society, 26(5), 517–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926515581154

- Awayed-Bishara, M. (2020). EFL pedagogy as cultural discourse : textbooks, practice, and policy for Arabs and Jews in Israel (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/EFL-Pedagogy-as-Cultural-Discourse-Textbooks-Practice-and-Policy-for/Awayed-Bishara/p/book/9781138308817.

- Awayed-Bishara, M., Netz, H., & Milani, T. (2022). Translanguaging in a context of colonized education: The case of EFL classrooms for arabic speakers in Israel. Applied Linguistics, 43(6), 1051–1072. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amac020

- Badil. (2011). Towards a comprehensive analysis of Israeli Apartheid. http://www.badil.org/en/publication/periodicals/al-majdal/item/1689-editorial.html.

- Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

- Banna, A. (2011). The housing crisis among the arab society in Israel. https://law.acri.org.il/he/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/housing-arabcitizens0811.pdf.

- Baron-Epel, O., Garty, N., & Green, M. S. (2007). Inequalities in use of health services among Jews and Arabs in Israel. Health Services Research, 42(3p1), 1008–1019. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00645.x

- Bassett, M. T. (2016). Beyond berets: The black panthers as health activists. American Journal of Public Health, 106(10), 1741–1743. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303412.

- Ben Zeev, N. (2022). Toward a history of dangerous work and racialized inequalities in twentieth-century Palestine/Israel. Journal of Palestine Studies, 51(4), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0377919X.2022.2123212

- Berman, T., & Barnett-Itzhaki, Z. (2017). Vulnerable populations. In R. Ostrin, & S. Rosen (Eds.), Environmental health in Israel 2017 (pp. 115–125). Ministry of Health. www.ehf.org.il/en.

- Bishara, A. (2017). Zionism and equal citizenship: Essential and incidental citizenship in the Jewish state. In N. Rouhana (Ed.), Israel and its Palestinian citizens: Ethnic privileges in the Jewish state (pp. 137–156). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107045316.006

- Blatman, N., & Sabbagh-Khoury, A. (2022).The presence of the absence: Indigenous Palestinian Urbanism in Israel. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 47(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13130.

- Bouquet, B., Muhareb, R., & Smith, R. (2022). “It’s not whatever, because this is where the problem starts”: Racialized strategies of elimination as determinants of health in palestine. Health and Human Rights Journal, 24(2), 237–254. https://www.hhrjournal.org/2022/12/its-not-whatever-because-this-is-where-the-problem-starts-racialized-strategies-of-elimination-as-determinants-of-health-in-palestine/

- Boyd, R., Lindo, E., Weeks, L., & McLemore, M. (2022). On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities|Health affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377forefront.20200630.939347/.

- Braveman, P., Egerter, S., & Williams, D. R. (2011). The social determinants of health: Coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health, 32, 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV-PUBLHEALTH-031210-101218

- B’Tselem. (2021). A regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea: This is apartheid | B’Tselem. https://www.btselem.org/publications/fulltext/202101_this_is_apartheid.

- Butler, J. (2012). Parting ways: Jewishness and the critique of Zionism. Columbia University Press.

- Calhoun, A. (2021). The pathophysiology of racial disparities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(20), e78. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMpv2105339

- CBS. (2020). Local authorities in ascending order of the socio economic index 2017. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/doclib/2020/403/24_20_403t1.pdf.

- CBS. (2021). Population by population group. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2021/2.shnatonpopulation/st02_01.pdf.

- Cerdeña, J. P., Plaisime, M. V., & Tsai, J. (2020). From race-based to race-conscious medicine: How anti-racist uprisings call us to act. The Lancet, 396(10257), 1125–1128. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32076-6

- Chernichovsky, D., Bisharat, B., Bowers, L., Brill, A., & Sharony, A. (2017). Health of the arab population in Israel. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel, 1–50. https://www.taubcenter.org.il/

- Churchwell, K., Elkind, M. S. V., Benjamin, R. M., Carson, A. P., Chang, E. K., Lawrence, W., Mills, A., Odom, T. M., Rodriguez, C. J., Rodriguez, F., Sanchez, E., Sharrief, A. Z., Sims, M., & Williams, O. (2020). Call to action: Structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities: A presidential advisory from the American heart association. Circulation, 142(24), E454–E468. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000936

- Clarfield, A. M., Manor, O., Nun, G. B., Shvarts, S., Azzam, Z. S., Afek, A., Basis, F., & Israeli, A. (2017). Health and health care in Israel: an introduction. The Lancet, 389(10088), 2503–2513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30636-0.

- Coursen-Neff, Z. (2004). Discrimination against Palestinian Arab children in the Israeli educational system. New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, 36(4), 749–816.

- Daoud, N. (2008). Challenges facing minority women in achieving good health: Voices of arab women in Israel. Women & Health, 48(2), 145–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630240802313530

- Daoud, N. (2021). Health policies towards the Palestinian society in Israel before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Where are we from health justice ? Madar Israeli Affairs, 82, 19–35. https://www.madarcenter.org/مجلة-قضايا-اسرائيلية/قضايا-اسرئيلية-عدد−82.

- Daoud, N., Abu-Hamad, S., Berger-Polsky, A., Davidovitch, N., & Orshalimy, S. (2022). Mechanisms for racial separation and inequitable maternal care in hospital maternity wards. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114551–114551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114551.

- Daoud, N., Alfayumi-Zeadna, S., & Jabareen, Y. T. (2018a). Barriers to health care services among Palestinian women denied family unification in Israel. International Journal of Health Services, 48(4), 776–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020731418783912

- Daoud, N., Alfayumi-Zeadna, S., Tur-Sinai, A., Geraisy, N., & Talmud, I. (2020). Residential segregation, neighborhood violence and disorder, and inequalities in anxiety among Jewish and Palestinian-Arab perinatal women in Israel. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 218–218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01339-5.

- Daoud, N., Ali Saleh-Darawshy, N., Gao, M., Sergienko, R., Sestito, S. R., & Geraisy, N. (2019). Multiple forms of discrimination and postpartum depression among indigenous Palestinian-Arab, Jewish immigrants and non-immigrant Jewish mothers. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1741–1741. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8053-x.

- Daoud, N., Gao, M., Osman, A., & Muntaner, C. (2018b). Interpersonal and institutional ethnic discrimination, and mental health in a random sample of Palestinian minority men smokers in Israel. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(10), 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1531-0

- Daoud, N., & Jabareen, Y. (2014). Depressive symptoms among Arab Bedouin women whose houses are under threat of demolition in Southern Israel: A right to housing issue. Health and Human Rights Journal, 16(1), 179–191. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/harhrj16&id=183&div=&collection

- Daoud, N., O’Campo, P., Anderson, K., Agbaria, A. K., & Shoham-Vardi, I. (2012a). The social ecology of maternal infant care in socially and economically marginalized community in southern Israel. Health Education Research, 27(6), 1018–1030. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cys052

- Daoud, N., Shankardass, K., O’Campo, P., Anderson, K., & Agbaria, A. K. (2012b). Internal displacement and health among the Palestinian minority in Israel. Social Science & Medicine, 74(8), 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.041

- Daoud, N., Soskolne, V., & Manor, O. (2009). Educational inequalities in self-rated health within the arab minority in Israel: Explanatory factors. The European Journal of Public Health, 19(5), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp080

- Daoud, N., Soskolne, V., Mindell, J. S., Roth, M. A., & Manor, O. (2018c). Ethnic inequalities in health between Arabs and Jews in Israel: The relative contribution of individual-level factors and the living environment. International Journal of Public Health, 63(3), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1065-3

- Davis, A. (2015). Reflections on the Black Woman’s role in the community of slaves. The Black Scholar, 12(6), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.1981.11414214

- Efrati, I. (2021, June 24). Israeli Arab death rate from COVID-19 was three times higher than general population, study finds. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/study-israeli-arab-death-rate-from-covid-three-times-higher-than-general-population-1.9937934.

- El-Haj, N. A. (2010). Racial palestinianization and the Janus-faced nature of the Israeli state. Patterns of Prejudice, 44(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220903507610

- Erakat, N. (2021, July 5). Beyond discrimination: Apartheid is a colonial project and zionism is a form of racism. EJIL: Talk - Blog of the European Journal of International Law. https://www.ejiltalk.org/beyond-discrimination-apartheid-is-a-colonial-project-and-zionism-is-a-form-of-racism

- Estes, N. (2019). Our history is the future standing rock versus the dakota access pipeline, and the long tradition of indigenous resistance. Verso Books. https://www.versobooks.com/books/2953-our-history-is-the-future.

- Falah, G. (2020). Israeli "judaization" policy in galilee. Journal of Palestine Studies, 20(4), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2537436

- Falah, G. W. (2003). Dynamics and patterns of the shrinking of Arab lands in Palestine. Political Geography, 22(2), 179–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(02)00088-4

- Farmer, P. (2001). Infections and inequalities. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520927087/HTML.

- Farzan, A. N. (2021, May 13). Arab Israelis are rising up to protest. Here’s what you need to know about their status in the country. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/05/13/arab-israeli-faq/.

- Filc, D. (2010). Circles of exclusion: Obstacles in access to health care services in Israel. International Journal of Health Services, 40(4), 699–717. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.40.4.h

- Forman, G., & Kedar, A. (2016). From arab land to ‘Israel Lands’: The legal dispossession of the Palestinians displaced by Israel in the wake of 1948. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 22(6), 809–830. https://doi.org/10.1068/d402

- Giacaman, R. (2020). Reframing public health in wartime: From the biomedical model to the “wounds inside”. Journal of Palestine Studies, 47(2), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2018.47.2.9

- Gilmore, R. W. (2010). Fatal couplings of power and difference: Notes on racism and geography. The Professional Geographer, 54(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00310

- Gilmore, R. W. (2011). What is to be done? American Quarterly, 63(2), 245–265. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41237545#metadata_info_tab_contents https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2011.0020

- Gilmore, R. W. (2015). organized abandonment organized violence : Devolution and the police. In UC Santa Cruz (Vol. 9, Issue 9). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?start=10&q=organized+abandonment+organized+violence&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5.

- Gilmore, R. W. (2022). R. W. Gilmore (Ed.), Abolition geography, essays towards liberation. Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/books/3785-abolition-geography

- Goldberg, D. T. (2009). The threat of race : reflections on racial neoliberalism. Wiley-Blackwell. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/The+Threat+of+Race%3A+Reflections+on+Racial+Neoliberalism-p-9780631219675.

- Goldberg, D. T. (2015). Are we all postracial yet? John Wiley & Sons. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Are+We+All+Postracial+Yet%3F-p-9780745689715.

- Gordon, N. (2019). Ronit Lentin, Traces of racial exception: Racializing Israeli settler colonialism. Irish Journal of Sociology, 27(1), 88–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0791603519828666.

- Gracey, M., & King, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet, 374(9683), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4.

- Haddad Haj-Yehya, N., & Rudnitzky, A. (2018). A master plan for informal education in Arab society - The Israel democracy institute. https://en.idi.org.il/publications/36186.

- Hamdan, H. (2005). Individual settlement in the Naqab: The exclusion of the Arab minority. https://www.adalah.org/uploads/oldfiles/newsletter/eng/feb05/fet.pdf.

- Harvey, M., Neff, J., Knight, K. R., Mukherjee, J. S., Shamasunder, S., Le, P. V., Tittle, R., Jain, Y., Carrasco, H., Bernal-Serrano, D., Goronga, T., & Holmes, S. M. (2020). Structural competency and global health education. Global Public Health, 17(3), 341–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1864751.

- Hasan, M. (2019). Palestine’s absent cities: Gender, memoricide and the silencing of urban Palestinian memory. Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies, 18(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3366/hlps.2019.0200

- Hawari, Y. (2019). Erasing Memories of Palestine in Settler-Colonial Urban Space : The case of Haifa. In Routledge Handbook on Middle East Cities (1st ed., pp. 104–120). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315625164-8.

- Herculano, S., & Pacheco, T. (2008). Building environmental justice in Brazil: A preliminary discussion of Environmental Racism. In J. M. Fritz (Ed.), International Clinical Sociology (pp. 244–265). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73827-7_16.

- Hesketh, K., Bishara, S., Rosenberg, R., & Zaher, S. (2011). The inequality report the Palestinian arab minority in Israel. https://www.adalah.org/uploads/oldfiles/upfiles/2011/Adalah_The_Inequality_Report_March_2011.pdf.

- Himmelstein, K. E. W., Lawrence, J. A., Jahn, J. L., Ceasar, J. N., Morse, M., Bassett, M. T., Wispelwey, B. P., Darity, W. A., & Venkataramani, A. S. (2022). Association between racial wealth inequities and racial disparities in longevity among US adults and role of reparations payments, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Network Open, 5(11), e2240519–e2240519. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.40519

- Hirsch, L. A. (2021). Is it possible to decolonise global health institutions? The Lancet, 397(10270), 189–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32763-X

- Horton, R. (2021). Offline: The myth of “decolonising global health”. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1673–1673. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02428-4.

- HRW. (2021). Israeli authorities and the crimes of apartheid and persecution | HRW. https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/04/27/threshold-crossed/israeli-authorities-and-crimes-apartheid-and-persecution.

- Israeli Ministry of Health. (2020). Inequality in health and ways to deal with it. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/inequality-2019.pdf.

- Jabareen, H., & Bishara, S. (2019). The Jewish nation-state law: Antecedents and constitutional implications. Journal of Palestine Studies, 48(190), 46–55. https://www.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/attachments/jps-articles/THE_JEWISH_NATION-STATE_LAW_ANTECEDENTS_AND_CONSTITUTIONAL_IMPLICATIONS.pdf

- Jabareen, Y. (2017). Controlling land and demography in Israel: The obsession with territorial and gerographic dominance. In N. Rouhana (Ed.), Israel and the Palestinian citizens: Ethnic privileges in the Jewish state (pp. 238–255). Cambridge University Press.

- Jaffe, A., Giveon, S., Wulffhart, L., Oberman, B., Baidousi, M., Ziv, A., & Kalter-Leibovici, O. (2017). Adult Arabs have higher risk for diabetes mellitus than Jews in Israel. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0176661–e0176661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176661.

- Jemal, A., Thun, M. J., Ward, E. E., Henley, S. J., Cokkinides, V. E., & Murray, T. E. (2008). Mortality from leading causes by education and race in the United States, 2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(1), 1–8.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.017

- Jiryis, S. (1973). The legal structure for the expropriation and absorption of arab lands in Israel. Journal of Palestine Studies, 2(4), 82–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/2535632

- Jones, C. P. (2002). Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon (1960-), 50(1/2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/4149999.

- Kanaaneh, H. (2017). Health and politics: War by other means on the Palestinian minority in Israel, 33(3), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623699.2017.1374081

- Kanaaneh, H., McKay, F., & Sims, E. (1994). A human rights approach for access to clean drinking water: A case study. Health and Human Rights, 1(2), 191–204. https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/harhrj1&id=198&div=&collection.

- Karkabi, B., Zafrir, B., Jaffe, R., Shiran, A., Jubran, A., Adawi, S., Ben-Dov, N., Iakobishvili, Z., Beigel, R., Cohen, M., Goldenberg, I., Klempfner, R., Flugelman, M. Y., & Rubinshtein, R. (2020). Ethnic differences among acute coronary syndrome patients in Israel. Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine, 21(11), 1431–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2020.04.023

- Kelley, R. D. G. (2003). Freedom dreams : The black radical imagination. Penguin Random House.

- Khalidi, R. (2020). The hundred years’ War on palestine: A history of settler colonialism and resistance, 1917–2017 (1st ed.). Metropolitan Books.

- Khatib, M., Sheikh-Muhammad, A., Omar, F., Marjieh, S. R., & Tanous, O. (2022). Perceptions of violence and mistrust in authorities among Palestinians in Israel, an unrecognised public health crisis: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 399, S37–S37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01172-2.

- Khoury, J., Peleg, B., Efrati, I., & Kadari-Ovadia, S. (2021, October 28). Five-year plan for Israel’s arab community: $9 billion won’t bridge a gap decades in the making. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2021-10-28/ty-article/.premium/five-year-plan-for-israels-arab-community-9-billion-wont-bridge-the-gap/0000017f-e224-df7c-a5ff-e27e91760000.

- King, M., Smith, A., & Gracey, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 2: The underlying causes of the health gap. The Lancet, 374(9683), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8.

- Knesset. (2018). Basic law: Israel - the nation state of the Jewish people. The Knesset. https://knesset.gov.il/laws/special/eng/BasicLawNationState.pdf

- Krieger, N. (2012a). Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 936–944. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544

- Krieger, N. (2012b). Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 936–944. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544

- Krieger, N. (2014). Discrimination and health inequities. International Journal of Health Services, 44(4), 643–710. https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.44.4.b

- Lancet Palestine Health Alliance. (2019, March). Research in the occupied Palestinian territory. The Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/issue/vol393nonull/PIIS0140-6736(19)X0012-4#closeFullCover.

- Lavie, S. (2018). Wrapped in the flag of Israel: Mizrahi single mothers and bureaucratic torture. University of Nebraska Press.

- Lentin, R. (2017). Traces of racial exception: Racializing Israeli settler colonialism. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350032088.

- Lidsky, T. I., & Schneider, J. S. (2003). Lead neurotoxicity in children: Basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Brain, 126(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg014

- Lurie, J. (2019, August 19). The Minneapolis-founded american indian movement responded to the needs of urban American Indians. MINNPOST. https://www.minnpost.com/mnopedia/2019/08/the-minneapolis-founded-american-indian-movement-responded-to-the-needs-of-urban-american-indians/.

- Magnan, S. (2017). Social determinants of health 101 for health care: Five plus five. NAM Perspectives, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.31478/201710c

- Malloy, S. L. (2017). We’re relating right now to the third world”: Creating an anticolonial vernacular, 1967–1968. In Out of Oakland (pp. 70–106). Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501712715.

- Mamdani, M. (2015). Settler colonialism: Then and now. Critical Inquiry, 41(3), 596–614. https://doi.org/10.1086/680088

- Mamdani, M. (2020). Neither settler nor native. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674249998/HTML

- Massey, D., & Denton, N. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard university press.

- Matache, M., & Bhabha, J. (2020). Anti-roma racism is spiraling during COVID-19 pandemic. Health and Human Rights, 22(1), 379–382. PMID: 32669824.