ABSTRACT

We report on a comparative situational analysis of comprehensive abortion care (CAC) in Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho and Namibia. We conducted systematic literature searches and country consultations and used a reparative health justice approach (with four dimensions) for the analysis. The following findings pertain to all four countries, except where indicated. Individual material dimension: pervasive gender-based violence (GBV); unmet need for contraception (15−17%); high HIV prevalence; poor abortion access for rape survivors; fees for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services (Eswatini). Collective material dimension: no clear national budgeting for SRH; over-reliance on donor funding (Eswatini; Lesotho); no national CAC guidelines or guidance on legal abortion access; poor data collection and management systems; shortage and inequitable distribution of staff; few facilities providing abortion care. Individual symbolic dimension: gender norms justify GBV; stigma attached to both abortion and unwed or early pregnancies. Collective symbolic dimension: policy commitments to reducing unsafe abortion and to post-abortion care, but not to increasing access to legal abortion; inadequate research; contradictions in abortion legislation (Botswana); inadequate staff training in CAC. Political will to ensure CAC within the country’s legislation is required. Reparative health justice comparisons provide a powerful tool for foregrounding necessary policy and practice change.

Introduction

In this paper, we provide a comparative situational analysis of comprehensive abortion care (CAC) across four southern African countries: Botswana; Eswatini; Lesotho; and Namibia. About one in five pregnancy-related deaths (across the three countries for which there are data) is owing to complications arising from abortion: 21% in Botswana (Statistics Botswana, Citation2019); 23% in Eswatini (Eswatini Ministry of Health, Citation2015); 20% in Lesotho (Lesotho Ministry of Health, Citation2015a). In Namibia, abortion-related complications make up 23% of MaternalFootnote1 Near Misses (women who nearly die but survive a complication that occurred during pregnancy, childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy) (Heemelaar et al., Citation2019).

Given the high proportion of pregnancy-related deaths (or maternal mortality ratio (MMR)) accounted for by abortion, as well as each country’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of reducing MMR, the reduction of unsafe abortions and an improvement in CAC in the region is needed. CAC is defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as provision of information, abortion management (including induced abortion and care related to pregnancy loss) and post-abortion care (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Access to CAC is marred by numerous barriers in southern Africa. These include restrictive legislation (Matshalaga & Mehlo, Citation2022), stigma, healthcare providers being ignorant of CAC protocols (Klingberg-Allvin et al., Citation2018), poor access to, and low quality of, post-abortion services (Ngalame et al., Citation2020), women living in rural areas having less access than their urban counterparts, and a neglect of adolescent-specific services (Aantjes et al., Citation2018). Klingberg-Allvin et al. (Citation2018) stress the importance of information provision and capacity building in overcoming these challenges in the region. They argue for the sharing of recent scientific evidence, guidelines and training programmes aimed at increasing women’s access to CAC at the lowest effective level in the healthcare system. This paper contributes to these efforts.

The comparative method we used enables lessons to be learnt across countries as well as highlighting commonalities. Through its use of a reparative health justice approach, this comparative methodology is in line with the gender-transformative approach called for in sub-Saharan Africa (and elsewhere) to address gender-based health inequities through minimising unsafe abortions (Shah et al., Citation2021).

The selection of the four countries is convenient as each (supported by WHO and United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA) engaged in the process of a Strategic Assessment (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2007) on unintended pregnancies, contraception, abortion, sexual- and gender-based violence and HIV. Nevertheless, the countries share the following commonalities: part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC); topographical features that make access to and the provision of healthcare a challenge (two – Botswana and Namibia – have large swathes of desert and a low population density, while the other two are largely mountainous, with higher population densities); signed the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (United Nations, Citationn.d.), which contains obligations to attend to reproductive rights, as well as the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development (Southern African Development Community, Citation2008).

Pertinent country background information

outlines some pertinent background information on each country. The Human Development Index (HDI) of the countries differs: Botswana has the highest and Lesotho the lowest. The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Eswatini and Lesotho is considerably higher than it is in Botswana and Namibia. All countries’ MMR are more than double the SDG aim of 70 per 100,000 live births. The total fertility rate of all four countries is higher than the global average of 2.5.

Table 1. Pertinent background information.

All four countries follow the Primary Health Care (PHC) approach: referral systems between community outreach points, mobile units, health clinics, health centres, district or regional hospitals and primary or national referral hospitals.

Background: legislative frameworks

Abortion is legislated through various Acts in the four countries:

In Botswana, abortion is covered by Sections 160–162 of the Penal Code (Amendment) Act, Citation1991 within the category of ‘Offenses against Morality’.

In Eswatini, Section 15 of The Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland Act, Citation2005 criminalises abortion together with providing the conditions under which abortions may be provided.

In Lesotho, induced abortion is criminalised by Section 45 of the Penal Code Act, Citation2010 but is permitted under specific circumstances under a ‘defence to a charge’.

In Namibia, The Abortion and Sterilisation Act (Republic of Namibia, Citation1975) stipulates the conditions under which abortion may be performed.

The legislative conditions for providing or procuring an abortion in each of the countries is laid out in .

Table 2. Legislative conditions for providing or procuring abortions.

In all four countries, abortion performed outside of the legal frameworks is criminalised, carrying prison sentences or fines. With this as background, we now turn to the comparative analysis.

Method

Between 2019 and 2022, the Ministries of Health in Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and Eswatini, with the support of UNFPA and WHO, embarked on country-specific Strategic Assessments. The initial stage consisted of background papers on current data and research (written and developed by the authors). This article is based on these background papers.Footnote2

For each background paper, we obtained information through desk-based searches and documentation supplied by UNFPA and WHO Country Offices, and by members of relevant Ministries, NGOs, statutory bodies and educational institutions (the first author conducted country visits, except in the case of Namibia owing to COVID restrictions). We accessed peer reviewed research via searches of the following databases: Academic Search Premier; ERIC (Education Resource Information Centre); Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition; Medline; PsyArticles; PsyINFO; SocIndex; Sabinet; Web of Science and Google scholar. Grey literature was accessed through desk-based searches and references made by key informants and references within reports already obtained. The search was restricted to the last decade to ensure that the information is current. As the background papers were based on public documents, no ethics approval was necessary for this segment of the programme.

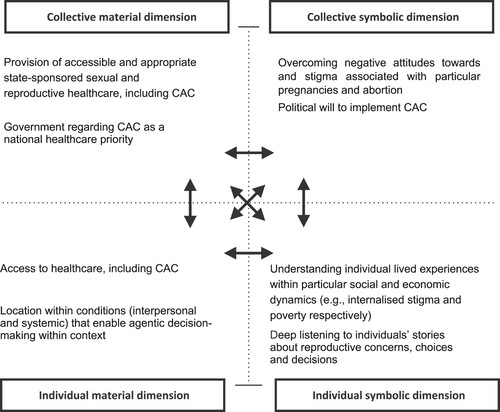

For this paper, we used the background papers to perform a comparative analysis. To do so, we used a reparative health justice approach, based on Verdeja’s (Citation2008) work and used in other analyses on abortion (Macleod & Reynolds, Citation2021) and early reproduction (Macleod & Feltham-King, Citation2020). The approach is broadly located within a reproductive justice stance in which the impact of multiple interweaving forms of oppression is recognised and rights and the ability to exercise rights are viewed in context (Morison, Citation2023; Ross & Solinger, Citation2017). To our knowledge, this is the first time that the reparative health justice approach is being used for comparative purposes.

In general, reparative justice implies recompense or restitution for an injustice in which a person’s rights (in this case health rights) have been harmed. Applied to reproductive health, the approach advocates interlinked multi-sectoral remedies or recompenses when pregnant people’s rights to reproductive healthcare are jeopardised. Drawing on the interweaving of the politics of (re)distribution (just and fair distribution of material resources, especially in cases of material inequities) and of recognition (the right to ethical self-definition or identity), the model involves analyses of two conditions: material/objective conditions and symbolic/subjective, identity-based conditions. These are analysed at two levels: individual and collective. The combination of conditions and levels allows for four ‘ideal-typical’ dimensions to be analysed: individual material; collective material; individual symbolic, and collective symbolic. These dimensions are described in relation to comprehensive abortion care in (adapted from Macleod Citation2019).

The first two authors went through the background papers, using the dimensions as templates in which to categorise the information contained in the background papers, as these papers were not written using the reparative justice dimensions. The categorisation was checked by the other authors for accuracy. There were no disagreements regarding the categorisation.

The limitations of this comparative study are as follows. The documents accessed for the background papers do not necessarily refer to the same indicators in each country. Where the same indicators are referred to, they may vary across the countries in terms of the years in which they were gathered. The concentration on contraceptive prevalence as an indicator of public health success has been questioned. Senderowicz (Citation2019, Citation2020), for example, highlights contraceptive coercion and argues, instead, for the measurement of contraceptive autonomy. Finally, the recompenses or remedies suggested are ideal; some may require the allocation of fiscal and human resources beyond the countries’ current governance capacities. We, nevertheless, outline these ideal remedies, with an indication at the end of the initial processes that could be taken on the road to these ideal remedies.

Findings

In the tables that follow, we outline the indicators, data and information available for each country within the various dimensions. Injustices are highlighted in grey. These injustices are identified on the basis of the reparative health justice principles outlined above. The column on the right suggests the remedy to be put in place to overcome the highlighted injustices.

Individual material dimension

The individual material dimension is outlined in .

Table 3. Individual material dimension.

There are clear material gender injustices across all four countries. Employment is lower for women than men in all countries bar Namibia and performance on the SDG gender indicators are low in all four. Unmet need for contraception affects just below 1 in 5 women, with many marginalised women being worse affected. Unintended or mistimed pregnancies hover around 50% in the two countries where data are available (Lesotho and Namibia). Legal abortion appears to be difficult to obtain, especially for rape survivors. Gender-based violence and HIV prevalence are high. Where data are available, post-abortion care has been found to be suboptimal.

Collective material dimension

The collective material dimension is outlined in .

Table 4. Collective material dimension.

In two countries (Botswana and Eswatini) health expenditure is lower than the world average, and there is no clear SRH health budget. Over-reliance on donor funding creates a challenge for sustainability in Eswatini and Lesotho. Health data collection and management is poor across all countries, with data on abortion being difficult to obtain in Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia. In all countries, health staffing is a problem (shortages and inequitable distribution across rural and urban areas). Legal abortion and post-abortion care services are suboptimal, as are youth friendly services. Emergency contraception is available, but there is little information on its distribution. Although some progress has been made in relation to GBV services in all four countries, significant challenges remain.

Individual symbolic dimension

The individual symbolic dimension is outlined in .

Table 5. Individual symbolic dimension.

Significant injustices are highlighted in . These include, across all four countries, discriminatory gender norms, and stigma attached to abortion and/or non-marital or early pregnancies. These norms and stigma potentially form barriers to healthcare seeking as women fear judgemental attitudes from staff and others. Where data are available, women’s knowledge of the respective countries abortion laws appears to be poor (Botswana and Namibia). Information on women’s knowledge of emergency contraception is lacking, except for in Botswana where it appears to be poor.

Collective symbolic dimension

The collective symbolic dimension is outlined in .

Table 6. Collective symbolic dimension.

The only country with any abortion guidelines is Botswana, although these are focussed on post-abortion care. No research specifically focussing on legal abortion services or post-abortion care could be located in any of the countries. Where information is available, training of health service providers in CAC is suboptimal. The procedures whereby legal abortions may be obtained are not addressed in policy or protocols in any of the countries.

In the tables below (), we outline how national and health sector policies in the four countries address abortion. All countries acknowledge that unsafe abortion is an issue that needs to be addressed in reducing pregnancy-related mortality. Notably, for all countries, except Botswana, policies do not provide specific details and guidelines for providing safe abortions within the ambit of their respective legislative frameworks. Policies across all four countries speak to managing unsafe abortions by preventing abortion, clinical management of incomplete abortion, and providing post-abortion care and counselling.

Table 7. Botswana government policies and guidelines.

Table 8. Eswatini government policies and guidelines.

Table 9. Lesotho government policies and guidelines.

Table 10. Namibian government policies and guidelines.

Discussion

Despite the fact that abortion is legal under specific circumstances in all four countries, health data collection and management is sub-optimal. This indicates a need for health information systems to keep accurate data to assist with CAC planning and implementation. The implementation and monitoring of quality of care abortion service indicators as developed by Darney et al. (Citation2019) for low- and middle-income countries as well as recommendations from the WHO Abortion care guideline (World Health Organization, Citation2022) could assist in overcoming some of the challenges noted.

There is little research on post-abortion care in all four countries. Where studies have been conducted, the quality of post-abortion care appears to be substandard, including delayed care and prolonged hospital stays (Botswana and Namibia), inadequate standard operating procedures (Eswatini), few facilities offering post-abortion care (Lesotho), and signal functions of quality post-abortion care not being instituted (Namibia). Ongoing research should be funded, and poor areas of CAC functioning addressed in country-specific CAC Guidelines.

Access to legal abortion is minimal (e.g. few rape survivors are able to or do claim their legal right to abortion). Botswana is the only country with guidelines on post-abortion care. While the reduction of unsafe abortion and the provision of post-abortion care appear in a number of policies in all countries, information on the legal procedures for procuring an abortion is limited within policies and protocols and for the general population. Such information should be inserted into relevant policies and protocols and a range of health communication channels; and Comprehensive Abortion Care Guidelines should be developed.

Insufficient mention is made in policies regarding accessing, referring for, and conducting legal and safe abortion. Where research is available (Botswana and Lesotho), healthcare provider training in CAC has been shown to be suboptimal. To rectify this, CAC guidelines should be developed to ensure that providers are trained in CAC.

It is important that the needs of particular pregnant people are noted in the CAC Guidelines. For example, given the high prevalence of HIV in the region, the needs of pregnant people living with HIV for information and options concerning both safe pregnancies (e.g. prevention of mother to child transmission) and safe abortions (Orner et al., Citation2011) should be considered in devising policy and implementing CAC services. The needs of young people in relation to abortion, including privacy, non-coerced decision-making (in particular in relation to parents) and non-judgmental service provision (Macleod, Citation2017) should also be considered.

It is clear that gender inequities continue to plague all four countries, including gender-based violence, inequitable material conditions, and negative gender norms. Given that higher gender equality is linked with reduced rates of induced abortion (Dema Moreno et al., Citation2020; Uzoigwe, Citation2017), careful programming to reduce gender inequities is indicated. This is a cross-cutting issue for all Ministries and should not be delegated solely to Ministries dedicated to gender issues. An example of where such an interdisciplinary approach has been successful is the Botswana government’s implementation of a multi-sectoral mechanism to enhance prevention of GBV, which appears to have led to a decrease in GBV.

Health expenditure in Botswana and Eswatini is below the global average. In three of the countries (Botswana, Eswatini and Namibia), SRH services do not have a clear budget allocation. This should be rectified. There is an over reliance on donor funding in Eswatini and Lesotho, which threatens the sustainability of programmes. Where donor funding sets up programmes, these should be sustained through internal funding.

The health workforce is understaffed, and inequitably distributed. Given the topographical challenges of the four countries, the staffing of rural health facilities is essential for proper service delivery, including CAC, in these areas.

Although the contraceptive use prevalence is higher than the global average and emergency contraception is stocked in all four countries, unmet need for contraception persists – especially amongst poorer, rurally-based, younger and older women. Careful supply chain management is needed to avoid stock-outs, and contraceptive support through public health clinics and community services strengthened.

Conclusion

Abortion (unspecified) accounts for about one in five pregnancy-related deaths in the four countries in which we conducted this situational analysis. Using a reparative health justice approach, we showed that there are several injustices – across individual material, individual symbolic, collective material, and collective symbolic dimensions – associated with women’s agentic decision-making regarding whether and under what circumstances to have children. The conditions needed to prevent unwanted pregnancies, both economic and health-related, require further work. This applies particularly to gender inequities, and requires cooperation across a range of Ministries tasked with governing education, economic development, labour, health and gender.

Access to safe, legal abortion appears to be minimal, and post-abortion care suboptimal. Policy guidance from relevant ministries and programme managers as well as service implementation to reach CAC are much needed.

All four countries are committed to the SDGs. Women’s access to sexual and reproductive health and rights and services, including CAC, are directly linked to reductions in pregnancy-related mortality (SDG 3). However, the benefits do not end there. Women’s and girls’ lack of autonomy over their health can limit their outcomes on education (SDG 4), sanitation and hygiene (SDG 6), employment (SDG 8) and political participation (SDG 10). Where inequities have been addressed through reparative justice, empowered women and girls contribute to promoting peaceful and inclusive societies (SDG 16), creating opportunities for decent work and employment (SDG 8), therefore also to poverty reduction (SDG 1) (Leone et al., Citation2017).

While this paper focusses on four countries in southern Africa, this type of analysis, and the lessons learnt from this analysis may be of use to other regional or international policy-makers. The reparative health justice framework is a relatively new addition to the analytical possibilities in reproductive health, in particular a gender transformative approach. The analysis conducted above illustrates its usefulness in highlighting cross-cutting, as well as specific policy and practice implications, across multiple countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ministeries of Health, and the UNFPA and WHO country offices in each of the four countries, as well as colleagues in the UNFPA/WHO 2gether4srhr initiative for the information shared and for comments on the background papers that formed the basis of this paper.

Disclosure statement

The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) or the World Health Organization (WHO).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The terms maternal mortality and maternal near misses assume that pregnant people are cisgender women and that they are or will be mothers. We opt for the ‘pregnancy-related deaths’ where feasible but use maternal mortality where that term is used in various documents (e.g. SDGs). We are aware that the use of the word ‘women’ creates a gender binary that does not acknowledge the existence of queer and non-binary people. We use the word in line with current data.

2 Lesotho did not go beyond the background paper.

References

- Aantjes, C. J., Gilmoor, A., Syurina, E. V., & Crankshaw, T. L. (2018). The status of provision of post abortion care services for women and girls in eastern and Southern Africa: A systematic review ⋆. Contraception, 98(2), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2018.03.014

- Billings, D., & Mallett, J. G. (2009). Talking about abortion in Namibia. Sister Namibia, 12–13.

- Botswana Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. (2017). National Development Plan 11.

- Botswana Ministry of Health. (2013). Bostwana comprehensive post abortion care reference manual. Ministry of Health, Government of Botswana.

- Botswana Ministry of Health. (2016). Comprehensive post abortion care trainer’s manual.

- Botswana Ministry of Health. (2018a). Botswana integrated sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health & nutrition (RMNCAH&N) strategy (Issue January).

- Botswana Ministry of Health. (2018b). Botswana integrated sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health & nutrition (RMNCAH&N) strategy.

- Botswana Ministry of Health. (2019). Third national multi-sectoral HIV and AIDS response strategic framework 2018-2023.

- Botswana Ministry of Nationality Immigration and Gender Affairs. (2018). Botswana national relationship study.

- Centers for Disease Contol and Prevention (CDC). (2018). Research Brief: One in three girls in Swaziland experience sexual violence in childhood. Violence Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/vacs/1in3girls-swaziland.html.

- Darney, B. G., Kapp, N., Andersen, K., Baum, S. E., Blanchard, K., Gerdts, C., Montagu, D., Chakraborty, N. M., & Powell, B. (2019). Definitions, measurement and indicator selection for quality of care in abortion. Contraception, 100(5), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.07.006

- Dema Moreno, S., Llorente-Marrón, M., Díaz-Fernández, M., & Méndez-Rodríguez, P. (2020). Induced abortion and gender (in)equality in Europe: A panel analysis. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 27(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506819893728

- Department of Women’s Affairs and GenderLinks. (2012). Gender Based Violence Indicators Study Botswana: Key findings of the Gender Based Violence Indicators Study by the Women’s Affairs Department and Gender Links.

- Doherty, K., Arena, K., Wynn, A., Offorjebe, O. A., Moshashane, N., Sickboy, O., Ramogola-Masire, D., Klausner, J. D., & Morroni, C. (2018). Unintended pregnancy in Gaborone. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 22(2), 77–82. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2018/v22i2.8

- Eswatini Central Statistical Office. (2017). The 2017 population and housing census preliminary results. Eswatini Central Statistical Office.

- Eswatini Central Statistical Office and UNICEF. (2016). Swaziland multiple indicator cluster survey 2014: Final Report.

- Eswatini Deputy Prime Minister’s Office and Department of Gender and Family Affairs. (2017). The National strategy to end violence in Swaziland 2017-2022. Eswatini Deputy Prime Minister’s Office.

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2010). Essential health care package for Swaziland. Eswatini Ministry of Health.

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2012). Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list of common medical conditions in the Kingdom of Swaziland.

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2015). The Second National health sector strategic plan 2014-2018 (Final Draft) (Issue March 2015).

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2018). Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) Annual Program Report 2018.

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2019a). Second quarter performance report for 2019-20 (Issue October).

- Eswatini Ministry of Health. (2019b). Sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, adolescent health and nutrition (SRMNCAH and N) strategic plan 2019 to 2023.

- Eswatini Ministry of Health & UNFPA. (2016). Socio-cultural factors influencing ASRH Service Utilization among Youth in Swaziland.

- Gawaya, R. (2016). Mid-term Review: The multi-sectoral implementation of the National Gender-based Violence Plan of Action, 2012-2016 (Issue May 2014).

- Government of Botswana. (2019). 2019/2020 Estimates of expenditure from the consolidated & development funds.

- Government of Lesotho. (2018). National HIV & AIDS Strategic Plan 2018/19-2022/23. Government of Lesotho.

- HEARD. (2016). Namibia unsafe abortion: Country factsheet. https://www.heard.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/namibia-country-factsheet-abortion-2016.pdf.

- Heemelaar, S., Kabongo, L., Ithindi, T., Luboya, C., Munetsi, F., Bauer, A. K., Dammann, A., Drewes, A., Stekelenburg, J., van den Akker, T., & Mackenzie, S. (2019). Measuring maternal near-miss in a middle-income country: Assessing the use of WHO and sub-Saharan Africa maternal near-miss criteria in Namibia. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1646036

- Kgosiemang, B., & Blitz, J. (2018). Emergency contraceptive knowledge, attitudes and practices among female students at the university of Botswana: A descriptive survey. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1674

- Khau, M. (2007). ‘But he is my husband ! How can that be rape ?’: Exploring silences around date and marital rape in Lesotho. Agenda (Durban, South Africa), 21(74), 1295–1306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2007.9674876

- Kingdom of Eswatini. (2015). National guidelines for maternal, perinatal and neonatal death surveillance and response (Issue March, pp. 1–65). Kingdom of Eswatini.

- Kingdom of Lesotho. (2019). Budget estimates book for financial year 2019/2020.

- Klingberg-Allvin, M., Atuhairwe, S., Cleeve, A., Byamugisha, J. K., Larsson, E. C., Makenzius, M., Oguttu, M., & Gemzell-Danielsson, K. (2018). Co-creation to scale up provision of simplified high-quality comprehensive abortion care in east central and Southern Africa. Global Health Action, 11(1), 1490106. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1490106

- Leone, F., Wahlén, C., & Paul, D. (2017). Achieve gender equality to deliver the SDGs. IISD: SDG Knowledge HUB. http://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/achieve-gender-equality-to-deliver-the-sdgs/.

- Lesotho Bureau of Statistics. (2018). 2016 Lesotho population and housing census analytical report, volume IIIA population dynamics. Ministry of Development and Planning, Government of Lesotho.

- Lesotho Ministry of Development Planning. (2012). National strategic development plan 2012/13-2016/17 (Issue June 2012). Ministry of Development and Planning, Government of Lesotho.

- Lesotho Ministry of Development Planning. (2018). National Addis Ababa declaration on population and development (AADPD) Plus Five Review Report: Final Report. Government of Lesotho.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2012). National quality standards for young people friendly health services in Lesotho. Ministry of Health, Government of Lesotho.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2014). Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: A guide for essential practice.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2015a). Emergency obstetric and neonatal care: needs assessment. Ministry of Health.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2015b). Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care: Needs Assessment. Ministry of Health.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2016). Lesotho demographic and health survey 2014. www.DHSprogram.com.

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2018). Health sector annual joint review 2017-2018 (Issue December).

- Lesotho Ministry of Health. (2019). National sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and nutrition strategic plan 2018-2022.

- Lesotho Penal Code Act. (2010). Lesotho Penal Code Act, 2010, 57 (2012).

- Macleod, C. (2017). ‘Adolescent’ sexual and reproductive health: Controversies, rights, and justice. In A. L. Cherry, V. Baltag, & M. E. Dillon (Eds.), International handbook on adolescent health and development: The public health response (pp. 169–181). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40743-2_9

- Macleod, C. (2019). Expanding reproductive justice through a supportability reparative justice framework: The case of abortion in South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1447687

- Macleod, C. I., & Feltham-King, T. (2020). Young pregnant women and public health: Introducing a critical reparative justice/care approach using South African case studies. Critical Public Health, 30(3), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1573313

- Macleod, C. I., & Reynolds, J. H. (2021). Reproductive health systems analyses and the reparative reproductive justice approach : a case study of unsafe abortion in Lesotho. Global Public Health, 0(0), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1887317

- Matshalaga, N., & Mehlo, M. (2022). Safe abortion policy provisions in the SADC region: Country responses, key barriers, main recommendations. Strengthening Health Systems (Southern African Journal of Public Health), 5(3), 68–76. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=159947226&lang=es&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Mavundla, S., & Ngwena, C. (2014). Access to legal abortion for rape as a reproductive health right: A commentary on the abortion regimes of Swaziland and Ethiopia. In C. Ngwena, & E. Durojaye (Eds.), Strengthening the protection of sexual and reproductive health through human rights in the African region (pp. 181–210). Pretoria University Law Press. http://www.academia.edu/download/38808804/Sexual_and_Reproductive_Rights_Africa.pdf#page=11

- Mayondi, G. K., Wirth, K., Morroni, C., Moyo, S., Ajibola, G., Diseko, M., Sakoi, M., Dipuo Magetse, J., Moabi, K., Leidner, J., Makhema, J., Kammerer, B., & Lockman, S. (2015). Unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, and childbearing desires among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Botswana: Across-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2498-3

- Melese, T., Habte, D., Tsima, B. M., Mogobe, K. D., Chabaesele, K., Rankgoane, G., Keakabetse, T. R., Masweu, M., Mokotedi, M., Motana, M., & Moreri-Ntshabele, B. (2017). High levels of post-abortion complication in a setting where abortion service Is Not legalized. Plos One, 12(1), e0166287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166287

- Ministry of Nationality Immigration and Gender Affairs. (2018). Botswana National relationship study. Ministry of Nationality Immigration and Gender Affairs.

- Morison, T. (2023). Using reproductive justice as a theoretical frame up in qualitative research in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 20(1), 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2022.2121236

- Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. (2014). Namibia demographic and health survey 2013. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR298/FR298.pdf.

- Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. (2016). Report on emergency obstetric and newborn care needs assessment.

- Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. (2018). Namibia national strategy for women, children, adolescents - health and nutrition (2018-2022).

- Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. (2019). National guidelines on family planning (Issue August). http//www.healthnet.org.na.

- Namibia Statistics Agency. (2017). Namibia inter-censal demographic survey 2016 Report. https://cms.my.na/assets/documents/NIDS_2016.pdf.

- National Emergency Response Council on HIV and AIDS (NERCHA). (2018). National multisectoral HIV and AIDS strategic framework 2018-2023. Kingdom of Eswatini.

- Ngalame, A. N., Tchounzou, R., Neng, H. T., Mangala, F. G. N., Inna, R. I., Kamden, D. M., Bilkissou, M., Dohbit, J. S., Justine, K. E., Noa, C. N., Lenka, B., Halle, G. E., Wekam, M. D., Delvaux, T., & Mboudou, E. T. (2020). Improving post abortion care (PAC) delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.4236/ojog.2020.1090119

- Niemeyer Hultstrand, J., Tydén, T., Jonsson, M., & Målqvist, M. (2019). Contraception use and unplanned pregnancies in a peri-urban area of eSwatini (Swaziland). Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, 20(August 2018), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2019.01.004

- Orner, P. J., de Bruyn, M., Barbosa, R. M., Boonstra, H., Gatsi-Mallet, J., & Cooper, D. D. (2011). Access to safe abortion: Building choices for women living with HIV and AIDS. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-14-54

- Owolabi, O. O., Biddlecom, A., & Whitehead, H. S. (2019). Health systems’ capacity to provide post-abortion care: A multicountry analysis using signal functions. The Lancet Global Health, 7(1), e110–e118. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30404-2

- Penal Code (Amendment) Act. (1991). Penal Code (Amendment) Act of 11 October 1991.

- Republic of Namibia. (1975). Abortion and Sterilization Act (Act 2 of 1975).

- Ross, L. J., & Solinger, R. (2017). Reproductive justice: An introduction. California University Press.

- Senderowicz, L. (2019). “I was obligated to accept”: A qualitative exploration of contraceptive coercion. Social Science & MedicineMedicine, 239(August), 112531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112531

- Senderowicz, L. (2020). Contraceptive autonomy: Conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator. Studies in Family Planning, 51(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12114

- Shah, P. K., Afulukwe, O., & Millbank, J. (2021). Towards a gender-transformative approach to abortion: Legislative perspectives from South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. In R. Vijeyarasa (Ed.), International Women’s Rights Law and Gender Equality (pp. 54–71). Routledge.

- Smith, S. (2012). Perceptions of abortion in contemporary urban Botswana [University of York]. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/2634/1/Perceptions_of_Abortion_in_Contemporary_Urban_Botswana.pdf.

- Smith, S. S. (2013). The challenges procuring of safe abortion care in Botswana. African Journal of Reproductive Health December, 17(4), 43–55. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajrh/article/viewFile/98373/87659

- Southern African Development Community. (2008). SADC protocol on gender and development.

- Statistics Botswana. (2018). 2017 Botswana Demographic Survey Report. www.statsbots.org.bw.

- Statistics Botswana. (2019). Botswana - Maternal Mortality Ratio 2017.

- The Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland Act. (2005). The Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland Act, 1 (2005).

- The World Bank. (2019). Namibia Public Expenditure Review. In The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12289-8_7

- Titus, M., Hendricks, R., Ndemueda, J., McQuide, P., Ohadi, E., Kolehmainen-Aitken, R. L., & Katjivena, B. (2015). Namibia National WISN Report 2015: A Study of Workforce Estimates for Public Health Facilities in Nambia.

- UNAIDS. (2021). Global HIV and AIDS statistics - fact sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet#:~:text = GLOBAL HIV STATISTICS&text = 37.7 million %5B30.2 million–45.1,AIDS-related illnesses in 2020.

- United Nations. (2020). World Fertility and Family Planning 2020. In Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/family/World_Fertility_and_Family_Planning_2020_Highlights.pdf.

- United Nations. (n.d.). Beijing Declaration and Platform of Action, adopted at the Fourth World Conference on Women, 27 October 1995. https://www.refworld.org/docid/3dde04324.html.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2020). The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene. In Human Development Report 2020. United Nations Development Progamme. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2020-report.

- UN Women. (2022). SDG Indicator Dashboard. https://data.unwomen.org/data-portal/sdg.

- Uzoigwe, C. (2017). Reduce inequality to reduce abortion. Nature, 544(7648), 35. https://www.nature.com/articles/544035d.pdf https://doi.org/10.1038/544035d

- Verdeja, E. (2008). A critical theory of reparative justice. Constellations (Oxford, England), 15(2), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.2008.00485.x

- Warren, C. E., Abuya, T., & Askew, I. (2013). Family planning practices and pregnancy intentions among HIV-positive and HIV-negative postpartum women in Swaziland: A cross sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 150. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/13/150%5Cnhttp://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed11&NEWS=N&AN=2013472730 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-150

- World Bank. (2022a). Current health expenditure (% of GDP). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS.

- World Bank. (2022b). Employment to population ratio. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.TOTL.SP.MA.NE.ZS.

- World Bank. (2022c). Fertility rate, total (births per woman). Data.Worldbank.Org.

- World Health Organization. (2012). Making health services adolescent friendly: Developing national quality standards for adolescent friendly health services. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75217/9789241503594_eng.pdf?sequence = 1.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2007). The WHO strategic approach to strengthening sexual and reproductive health policies and programmes. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/69883.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Abortion care guideline. World Health Organization.