ABSTRACT

Leadership by health professionals is key in any health system, but health leadership training programmes are varied in their conceptualisation, learning objectives, and design. This paper describes an undergraduate leadership and management module for health students at the University of Sierra Leone and provides lessons from the design process. Our methods included an initial scoping review and qualitative study, followed by a co-design process of 10 workshops and 17 consultation meetings. The result was a curriculum with learning outcomes emphasising leadership identity, proactiveness, management of people and of change, and the formation of peer relationships. Learning methods included group teaching, team quality improvement projects, mentoring, and reflective practice. Lessons from the design process included the importance of support from university leadership and extensive consultation. Virtual workshops enabled broader participation but limited relationship building. Integrating doctoral research into the process facilitated inclusion of evidence and theory but risked reducing ownership by faculty. The importance of interprofessionalism and management skills in leadership training emerged during the process, illustrating the effectiveness of a co-design approach. Our programme is broadly aligned with other health leadership frameworks and is distinctive due to its undergraduate focus, offering insights for leadership training design in other settings.

Introduction

Leadership is a key building block for any health system (World Health Organization, Citation2007), and effective leadership is associated with a range of positive organisational outcomes in health settings, including staff turnover, performance, and work satisfaction (Ciccone et al., Citation2014; Gilmartin & D’Aunno, Citation2007). Leadership development has, however, been historically neglected in health worker training. A global commission on health professions education, for example, noted that ‘all is not well’ for health systems worldwide as they struggle to adapt to growing complexity and costs. Professional education, they argued, ‘has not kept pace with these challenges, largely because of fragmented, outdated, and static curricula that produce ill-equipped graduates … [including] weak leadership to improve health-system performance’ (Frenk et al., Citation2010, p. 1923).

Leadership competency frameworks for health professionals are increasingly common, although these are predominantly developed in the global North (Keijser et al., Citation2019; NHS Improvement, Citation2019). In recent years, a number of health leadership development programmes have also been introduced in Sub-Saharan Africa, but these range in quality and approach, with many not incorporating an explicit underlying theory (Downing et al., Citation2016; Footer et al., Citation2017) or evaluation frameworks (Abdulmalik et al., Citation2014; Muhimpundu et al., Citation2018).

In this study, we sought to address those gaps through the design of a novel leadership and management programme (LMP) with faculty at the University of Sierra Leone’s (USL) College of Medicine & Allied Health Sciences (COMAHS). The country provides an interesting context for this study given its small size (with a population of seven million) and range of health leadership challenges. These difficulties include limited financial and human resources, relatively underdeveloped governance and institutions, dependence on international donors, and frequent health emergencies (Government of Sierra Leone, Citation2016; Musoke et al., Citation2019; Walsh & Johnson, Citation2018).

The primary focus of the programme was on leadership, for which we use Heifetz’s (Citation1994) definition of ‘mobilizing people to tackle tough problems’. The programme also included elements of management – while this was not originally intended as a central component of the course, it emerged as a priority through the co-design process. Although the distinction between leadership and management has been described as ‘a conceptual knot that is difficult to untangle’ (Fernandez et al., Citation2010), for our purposes we define management as ‘coping with complexity, particularly by setting goals and plans, organizing and staffing, and solving problems and monitoring results’ (Kotter, Citation1982). We define the term curriculum simply as ‘a planned educational experience’ (Thomas et al., Citation2016, p. 1). The term doctor refers in this paper to a person with a medical degree.

Our specific research objectives were to:

document the design of the LMP, specifically the curriculum, the evaluation approach, and its underlying theory

describe and reflect on the design process, including how different stakeholders were engaged, how the process evolved, and the use of a virtual workshop and consultation model

identify the enabling and constraining factors to programme design and implementation, including lessons learned

The programme was initially targeted only at medical students, and this is reflected in the qualitative studies in this paper. The focus on one cadre was to reduce the initial complexity and scale of the programme, given the limited resources available. As the importance of interprofessionalism became clear during the co-design process, the range of intended participants was later broadened to include the other major undergraduate health programmes at the University (i.e. nursing, pharmacy, and medical laboratory sciences).

Methodology

Study design

Our study was prospective, multi-stage and multi-method. The study was based on a combination of established theory and stakeholder engagement. Data sources included a scoping review, qualitative interviews, workshops and focus groups, document review and an online survey. The research spanned 29 months, starting in October 2019 and concluding in February 2022, and the overlapping dates of certain stages reflect the intentionally iterative nature of the design process.

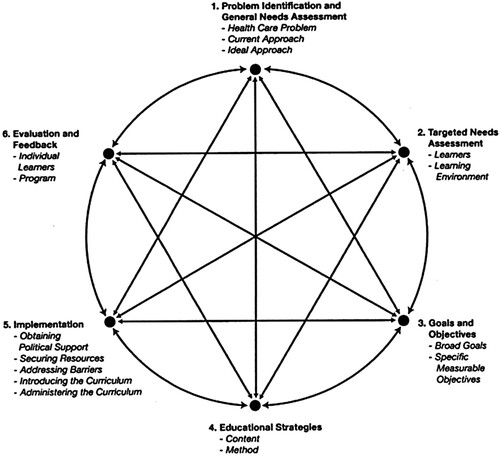

A form of co-design was used to develop this LMP, which is based on Ostrom’s (Citation1996) work on co-production, which argues that users (e.g. students) should be collaborators and contributors in the design of services. Students participated in the problem identification and needs assessment, through an initial qualitative study, and were consulted on the curriculum as part of the design process. The study design followed Kern’s six stage model for medical curriculum development, shown in (Thomas et al., Citation2016). This model was selected because it aligned closely with the principles of co-design and USL’s curriculum review process (University of Sierra Leone, Citation2019), and allowed for regular review and iterative refinement.

Figure 1. Kern’s six stage model for medical curriculum development (Thomas et al., Citation2016).

For each stage of the model, specific design and research methods were utilised, summarised in . At the time of writing, the design of the programme had been completed but the LMP had yet to be piloted or evaluated. The role of the four international co-authors (O.J., A.H.K., N.S., K.B.) was primarily to facilitate the co-design process as part of the lead author (O.J.)’s doctoral project, while the remaining Sierra Leonean co-authors contributed to the design and are also intending to oversee or implement the delivery of the LMP at USL.

Table 1. Summary of study and methods used charted against Kern’s six stage curriculum development model.

Stage 1: Problem identification and generalised needs assessment (October 2019 to July 2021)

The first stage of curriculum development includes problem identification and a general needs assessment. A scoping review on LMPs for health professionals in Sub-Saharan Africa was conducted to identify an ideal approach for the intended intervention. The databases searched were MedlinePlus, Embase, PsycINFO, Global Health, CINAHL, ProQuest, and Web of Science The review documented the leadership theories, curriculum, evaluation approaches, and lessons learned from the LMPs. The review was presented to the leadership of the University and the design team at the start of the process. Key findings are summarised in the Results section below, and the full study has been published separately (Johnson, Begg, et al., Citation2021).

Needs assessment was carried out qualitatively. Twenty-eight interviews were conducted with doctors in Sierra Leone, in two phases. The first phase (14 interviews) explored perceptions of effective leadership by doctors, contextual barriers to leadership, and ideas for strengthening health leadership. The second phase (14 interviews) involved consultation on the initial findings and further explored the retribution doctors in the country experienced when trying to lead. The interviews were semi-structured and based on topic guides. Participants were identified by the lead author (O.J.), who had previously worked in the country’s health system, and a co-author who is a senior Sierra Leonean doctor (F.S.). They used a combined snowballing and purposive sampling framework, to ensure diverse demographics, roles, and viewpoints were represented. This included a range of seniorities (junior, middle-grade, senior), specialties (clinical, public health, academic), sectors (public, private), genders, geographies (Freetown, rural, overseas), and relationships with the Government (aligned, critical) etc. Interviews were conducted in English by the lead author (O.J.), were between 23 and 125 min in length, and were recorded and transcribed. Sample size was calculated based on saturation using existing methods (Guest et al., Citation2006), which was achieved after 11 and 12 interviews respectively. Key findings are again summarised below and each phase published in detail separately (Johnson et al., Citation2022; Johnson, Sahr, et al., Citation2021).

Stages 2–4: Implementation (January to September 2021)

Stages 2–4 of the curriculum development were based on the findings of stage 1, and are described here together because they were conducted together using an integrated and iterative approach. These stages covered the initial programme design, including the formation of a targeted needs assessment (stage 2), goals and objectives (stage 3), and educational strategies for learning content and methods (stage 4). The lead author (O.J.) was invited by USL to facilitate the development of a LMP through a collaborative design approach. The University leadership then recruited five faculty members and one external expert to join the design team and participate in ten one-hour virtual design workshops conducted over a nine-month period. The external expert (K.B.) had previously designed and implemented interprofessional leadership training and was a Deputy Dean for Undergraduate Health Sciences Education in the region. The design team had expertise that included biomedical and clinical sciences, public health, and health professions education. The objective of the workshops was to design the curriculum of the LMP and undertake consultation across the University and wider health sector. This included the development of a theory of change, a visual diagram showing the LMP’s activities, outcomes and goal, while also identifying the risks and assumptions in this plan (Kahan et al., Citation2014; Maini et al., Citation2018). Workshops were structured by following the Kern model and were recorded.

Stage 5: Implementation (July to October 2021)

The fifth stage of design was implementation, which involved obtaining political support, identifying resource requirements and potential barriers, and introducing the curriculum. This phase remains ongoing at the time of writing. Seventeen consultation meetings were held, including five with University leadership to get input and ensure buy-in. These consisted of two with the Vice-Chancellor, one with the Deputy Vice-Chancellor and two with the four Faculty Deans. A further twelve were held virtually with external stakeholders, including student associations, professional associations, the Ministry of Health & Sanitation (which employs government health workers), and regulatory bodies. A draft of the programme design was presented for feedback in the form of digital slides, with contemporaneous notes taken.

Stage 6: Evaluation and feedback (November 2021 to February 2022)

The final design stage was evaluation and feedback, which was designed with the view to full implementation at a future timepoint. A methodology for evaluating the programme was discussed and agreed by the design team (see Results). As part of the final stage of development, a reflective exercise was carried out, which started with the design team completing an online survey to share individual perspectives on the process. The survey used Likert scales and open-ended questions to explore team members’ motivation for participation, ownership of the programme, experience of virtual meetings, views on the barriers and enablers to the design, and other related topics. The initial findings from the survey were discussed at a one-hour virtual focus group meeting with all team members. The online survey was anonymous and conducted using Google Forms.

Data analysis

For the qualitative interview data, verbatim transcripts were uploaded onto Nvivo 12 software (International QSR, Citation2018). The lead author (O.J.) reviewed each transcript in detail, assigning codes to relevant sections of data. A grounded theory approach was used, drawing on the work of Corbin and Strauss (Citation2012), where a systematic, inductive process is used in stages to generate insights that were based on the views of participants. Initial codes were checked with two authors (A.H.K. and N.S.) to ensure consensus and no significant changes were suggested. The same approach was used for analysis, which was conducted in stages using a systematic, inductive process to generate insights that were based on the views that were expressed by participants.

For the design workshops (stages 2–4), the outcomes of each discussion were summarised on a set of slides by the lead author (O.J.), which documented the evolution of the programme’s design and enabled the iterative development of a theory of change (Kahan et al., Citation2014). Details of attendance and contemporaneous notes from each consultation meeting (stage 5) were taken the lead author (O.J.). This information was all presented back at the next workshop, at which most team members were present, to check accuracy and use as inputs for each subsequent workshop.

Data from the online survey used for stage 6, were jointly analysed by two authors (O.J. and K.B.). The quantitative data was summarised descriptively, with thematic analysis used to summarise the results in slides. These slides were presented to survey participants in a focus group chaired by one author (K.B.), to enable facilitation that was independent of the lead author (O.J.), to confirm key findings and enable clarification.

Ethical approval

All members of the design team are authors of this paper and reviewed and approved the key findings that are described within. Ethical approval was granted by King’s College London and the Sierra Leone Ethical & Scientific Review Committee.

Role of previous research in this study

As described in detail above, this paper intentionally builds on previously published work, including a scoping review (Johnson, Begg, et al., Citation2021) and two qualitative studies (Johnson et al., Citation2022; Johnson, Sahr, et al., Citation2021). This extensive groundwork is central to the robustness of the methodology used in this study, as recommended by Kern’s model for curriculum development, and provided the basis for Stage 1 (Problem Identification & Generalised Needs Assessment) of the co-design process. A brief summary of the relevant key findings from those papers is provided below, to ensure a full account of the design process and curriculum is provided here. The vast majority of the findings of this study are entirely new, however, and have not been published elsewhere. This includes reporting on previously unpublished data from the qualitative interviews related to Stage 1 (on factors that influenced the leadership practice of current doctors, and views on how to strengthen health leadership), as well as all the findings for Stages 2–6 of the Kern model (see ). The findings from the ten co-design workshops, the 17 consultation meetings, the online survey, and the focus group are all reported here for the first time.

Results

The results are primarily organised by stage as per the diagram in , with an additional section exploring the lessons learned from the co-design process.

Problem identification and general needs assessment (Stage 1)

Review of leadership development programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa

The scoping review identified 28 studies on leadership development between 2002 and 2019, covering 23 of 46 countries in the region. They were commonly interprofessional, with 10–25 participants per cohort, and ranging between 6 and 24 months in duration. The main learning content topics were leadership, project management, and quality improvement (QI). Common learning methods were lectures or workshops, projects, mentoring, and groupwork. Only one programme targeted undergraduates (Najjuma et al., Citation2016), with the rest positioned as on-job fellowships or postgraduate qualifications. Key lessons learned were that programmes should be accredited, adapted to local contexts, supported by organisational leadership, embedded within national institutions, and financially sustainable with local resources.

Effective leadership, leadership theories, and contextual barriers

Twenty-seven Sierra Leonean doctors were interviewed representing a range of seniorities and specialties, with two based abroad and eight being women (for full details see Johnson et al., Citation2022). The qualitative studies found that participants generally viewed leadership by doctors as important for a strong health system but a weakness in Sierra Leone. A range of skills and behaviours for effective leadership were proposed, which were analysed to generate the underlying theory of leadership on which the LMP was designed. Servant or humble leadership (Mintzberg, Citation1998) described qualities such as being hard-working, persistent, and willing to make personal sacrifices. Relational leadership (Cleary et al., Citation2018) related to listening, and supporting junior colleagues. Managerial leadership (Fernandez et al., Citation2010) emphasised being punctual, organised and navigating bureaucracy. Finally, transformational leadership (Currie & Lockett, Citation2007) included setting a vision, being proactive, and not being afraid to challenge the system.

Participants identified leadership challenges in Sierra Leone that needed be navigated, such as administrative systems not functioning, politicisation of the health sector, and a culture of donor dependency. Examples were given of doctors facing retribution from their efforts to lead, such as reposting to rural areas, since, by definition, leadership involved a change to this status quo. People in power would often perceive change as a threat to their own interests, and would use their influence to punish those doctors trying to lead change in order to pressure the to abandon their efforts, as well as to deter other doctors from trying to make similar changes in the future. These reprisals were drivers for doctors who had attempted to lead change in the health system to either exit the government health sector (often by moving abroad) or become intimidated into silence or collusion.

All participants of this qualitative research component were medical doctors, since this was the initial target group of the LMP.

Factors that influenced the leadership practice of current doctors

Participants described a range of factors that they believed had shaped their own leadership and that of their peers. Representative quotes are listed in .

Table 2. Representative quotes on factors that shaped the leadership practice of doctors in Sierra Leone.

The main influence was family, with parents frequently cited as role models that shaped their ‘moral compass’. A second common factor was extra-curricular experiences at school and university. This is where people often had their first leadership experiences and some individuals became recognised as ‘future leaders’ amongst their peers. The final prominent factor was the role of religion, both in shaping an individual’s personal values but also in providing leadership role models.

Few participants had received leadership training, so this was rarely mentioned as an important influence. Military training had an impact on leadership by doctors serving in the armed forces. International training, such as a Master in Public Health or postgraduate medical training, was also influential in some cases.

Views on approaches to strengthen leadership capabilities of health professionals

Participants shared a range of views on how to strengthen leadership by health professionals in Sierra Leone, with quotes summarised in . There was consensus that all doctors need leadership and management training at an early stage, such as in medical school or during their internship. After this stage, many doctors are posted to district hospitals and are given leadership responsibilities.

Table 3. Representative quotes on factors that inform how leadership by health professionals in Sierra Leone can be strengthened.

While the research was initially focused around strengthening the leadership of doctors, several participants emphasised the importance of similar training for nurses and allied health professionals.

Participants recommended that training include workplace-based experience and be accredited. However, they noted the likely difficulty of finding faculty to teach leadership, since so few health professionals had previously received training in it. Participants described a need to change the mindset of senior colleagues towards mentoring and investing in the development of junior colleagues, which was considered difficult due to time constraints.

Initial programme design (Stages 2–4)

Learners and learning environment

The design team built on the qualitative findings, which had recommended that the training start at the undergraduate level and include several professional cadres, by locating it within COMAHS in Freetown. The programme will be a compulsory module on the four main undergraduate programmes at COMAHS: medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and medical laboratory sciences. Since the nursing faculty trains large numbers of students (280 per year), including registered nurses and a bachelors in nursing programme, the latter was selected for inclusion. The total student cohort would be expected to be approximately 165 students per year (50 clinical medical, 70 BSc nursing, 25 pharmacy, and 20 medical laboratory sciences students). The module would be added to the penultimate year of study for each course (year 5 medicine, year 3 nursing, year 4 pharmacy, year 3 medical laboratory sciences) to ensure that students had adequate maturity and clinical experience but were not simultaneously facing the workload of preparing for final exams.

There was consensus that the programme should be interprofessional, to reflect how leadership was practiced in the health system. Promoting interprofessional working was seen as a critical objective of the LMP and had not previously been prominent in undergraduate education at COMAHS.

Goals and objectives

In the needs assessment stage, participants had recommended that the LMP include an emphasis on teamwork, altruism and integrity, confidence, discipline, and taking the initiative for health system improvements.

Informed by the qualitative studies, three high-level goals for the LMP were identified: to directly improve patient care; to strengthen the wider health system; and to develop new services and innovations.

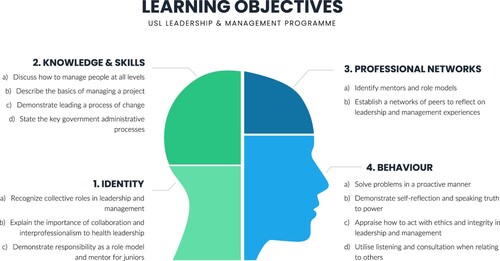

These goals were further developed into four major ‘themes’ of learning outcomes (identity, knowledge and skills, professional networks, and behaviour), each of which had between two and five intended learning outcomes (see ). The underlying theories of leadership on which the learning objectives were based were drawn from the models of leadership identified in the qualitative study (e.g. relational, transformational).

The first theme explores the need to shape the identity of students, with leadership and management seen as a core responsibility of all health professionals, not just of those in administrative roles. Health professionals should therefore approach leadership development as a career-long process. The LMP frames leadership as inherently interprofessional, with mentoring juniors and being a role model considered key components of professionalism.

Secondly, the learning objectives outline important knowledge and skills that centre around management. These include how to manage people and projects, as well as how to lead change, with a particular emphasis on quality improvement methods. Participants would also receive a foundation in how to work through the country’s government administrative processes.

Thirdly, the programme also seeks to strengthen participants’ horizontal peer networks and vertical relationships with mentors, to ensure that conversations and learning around leadership continue beyond the conclusion of the programme. Promoting solidarity between professionals was intended to protect future leaders from the retribution identified in the qualitative study (Johnson et al., Citation2022). Solidarity would achieve this by creating a critical mass of change agents and by encouraging seniors to protect juniors from unjustified victimisation.

Finally, the programme was designed to promote a range of behaviours aligned to our findings on effective leadership. This starts with being proactive at solving problems, which is intended to counteract feelings of helplessness, disempowerment, or donor dependency. The programme draws on key components of relational and humble leadership, including practicing self-reflection, speaking truth to power, acting with integrity, and listening to others. The final key behaviour emphasised in the qualitative research was actively supporting junior colleagues, for example by providing them with constructive feedback.

Teaching and learning methods

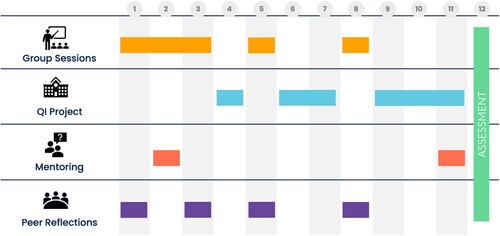

The qualitative study and scoping review both recommended a similar set of learning methods, and the LMP’s four learning components are summarised in .

A programme length of 12-weeks, consisting of one half-day per week, was selected to provide enough time to complete a QI project, embed learning, and trial new behaviours while also fitting within a semester and not displacing other modules.

Group sessions were designed to be held in interprofessional groups of 55 students, covering topics such as leadership theory, people management, communication, and professionalism (Ahmed & Oyeyemi, Citation2020). A full list of learning sessions with topics and learning objectives, as well as proposed assessment methods.

The QI projects would enable students to put into practice the knowledge, skills, and behaviours discussed in the group sessions (such as listening, managing and project and team, and being proactive), while strengthening their peer networks and solidifying their identities around leadership and interprofessionalism. QI projects would be conducted at hospitals or primary care facilities in Freetown over eight weeks in interprofessional teams of six to seven students. The team would work with a facility supervisor to identify a QI opportunity, collect baseline data, design and pilot a small intervention, evaluate the first improvement cycle, and then identify learnings and next steps.

Students would also be assigned a mentor in week one to explore their strengths, weaknesses, questions, and future opportunities around leadership (Goldstone & Ntuli, Citation2016). Mentors would ideally be middle-grade or senior grade health workers from the same professional cadre with experience and interest in leadership, based on availability. Mentors would receive training, written guidance, and a debriefing session.

Peer-reflective discussions would be held in private spaces by interprofessional groups of students (Colvin & Ashman, Citation2010; Sibiya et al., Citation2018). Participants would receive briefing and ground rules, along with semi-structured probing questions that would be aligned with the learning objectives (Gathu, Citation2022).

Assessment methods would include continuous assessment (attendance register and a mentor’s report), a written exam, and a structured oral exam where the QI projects would be presented and discussed. The oral exam would provide a key opportunity for shared reflection between students and with faculty, not only enabling individual student feedback but also providing a mechanism for iterative learning and improvement for the programme as a whole. Students would have to pass the programme to progress to their next academic year (Norcini et al., Citation2018; Torre et al., Citation2021).

Implementation (Stage 5)

Implementation steps included obtaining political support, consulting widely across the health sector, assessing necessary resources, and identifying barriers.

The team regularly presented to the University leadership, who fully endorsed the proposal and provided feedback around the programme structure and the length of the LMP. Consultation meetings demonstrated significant enthusiasm for an undergraduate LMP. Feedback included requests to make a similar programme available to current health workers through continuing professional development. Doing so would expand access to leadership training while also preparing faculty for teaching or mentoring on the undergraduate module.

The resource requirements for the programme were, by design, relatively minimal. This decision was guided by the scoping review, which found that utilising existing institutions and domestic funding to be an important lesson learned from other LMPs. By situating the programme within a university, the teaching venues, resources, and administration could be sourced from existing resources. Teaching, supervision, and mentoring would be provided by existing faculty and volunteers from the wider health sector. Many qualitative study and consultation participants offered during the co-design process to contribute to programme delivery. Learning materials would be digital, to reduce the cost of printing, which is feasible as students already rely on e-books for their studies. The QI projects would be required to use minimal resources, both to reduce the cost of implementation but also to encourage a mindset that change is possible without external funding. Health facility placements were restricted to the Freetown area so that student and faculty could organise transport for themselves, as is standard practice at COMAHS.

The design team held workshops to identify potential barriers or assumptions using a theory of change methodology. The main potential barriers identified were: whether faculty would allocate sufficient time for the programme without additional remuneration; a lack of study time from students due to pressures from the existing curriculum; the viability of QI projects without external funding; contradictory feedback given by mentors to students on leadership and management; and potential conflict if graduates of the programme found a mismatch between their learning and their experiences in the workplace. While the team attempted to mitigate some barriers by adjusting the programme design, many of them can only be addressed during the next phase of implementation.

Evaluation and feedback (Stage 6)

The final stage of curriculum development addressed how the programme should be evaluated to assess its impact and to enable continuous improvement. Evaluation design was informed by the scoping review. This evaluation should be understood separately to individual student assessment, although data from student assessment would be used to inform the programme evaluation.

A mixed-methods approach to programme evaluation was development based on the Kirkpatrick framework (Citation2006) for appraising training programmes, which is summarised in . The team intends to publish the findings of this evaluation after the pilot phase is completed.

Table 4. Evaluation design of the Leadership & Management Programme based on the Kirkpatrick framework (Citation2006).

Lessons from the design process

Through a reflective process including an anonymous survey, a focus group, and contemporaneous notes, the design team generated a range of insights into the experience of developing the LMP. These covered the motivations and membership of the design team, ownership of the LMP by the University, the use of virtual workshops, the impact of linking programme design to a research project, and enabling factors for the design process.

The primary motivation for team members to participate in the design was the impact the LMP would have on strengthening leadership in the health system. Several people also referenced their pre-existing relationships with the lead author (O.J.). There were no mentions of financial, research, or career opportunities. Team members felt that the makeup of the team was suitable to ensure robust design, contextual relevance, and faculty ownership, with suggested additions of a student representative and the head of the department where the LMP would sit. Team members described high levels of ownership of the programme and felt free to speak openly about sensitive issues. This safety was aided by how workshops were chaired to encourage input from every participant, along with individual follow up with participants by the facilitator between meetings. Emphasis was put on the value of regular engagement with the University leadership. The consultation was viewed as extensive and positive, but should have included engagement from all COMAHS staff and not only the faculty deans.

A distinctive aspect of the design process was that all workshops were held virtually, due to travel restrictions and safety concerns during the COVID pandemic. All team members felt the virtual approach was positive as it allowed more people to participate and enabled regular meetings over an extended period. The online format also eliminated the travel time to a workshop venue, was safe during the pandemic, and reduced costs. There were challenges however, with participants often multitasking or in transit during meetings, experiencing difficulty seeing slides from a phone screen, and missing non-verbal cues when video was switched off. The group recommended a virtual design process for future projects but suggested holding the first meeting in person to facilitate relationship building, and setting ground rules of attending via a laptop with video in a quiet room.

Participants were generally ambivalent about the impact of integrating the design process with doctoral research (led by O.J.), although the research was recognised as the main catalyst for the LMP. The research project also ensured commitment from the facilitator, adherence to clear timeframes, and provided a resource for organisation and note keeping. However, concerns raised that facilitation by a student from a different University might have undermined institutional ownership and sustainability at USL. The academic component of the project was seen to add rigour to the design process, ensuring greater engagement with theory, learning from the scoping review, and providing context-specific data from the qualitative studies. Downsides were also identified, namely that the academic components might have reduced the agency of the design team and their ownership of the LMP.

Enabling factors for the co-design process included early and strong support from University leadership, careful selection of a committed design team, connecting the team using a WhatsApp group, wide consultation across the health sector, and the organisational support from the lead author (O.J.). Opportunities for improvement included more face-to-face meetings, greater student involvement, and conducting small real-time pilots of the LMP during the design process to generate immediate feedback.

Discussion

We report the entire process of curriculum development for an interprofessional undergraduate LMP, including its underlying theory and a model for its evaluation. We documented the process of development, which included theory, literature review, qualitative interviews, design workshops, and stakeholder consultation. In doing so, the study addresses significant gaps in the literature about how LMPs can be designed in ways that are underpinned by leadership theory, pedagogically robust, and contextually relevant. Our analysis extends beyond describing the programme to exploring reflections from the design process, including lessons for the future. Five key topics emerged from the co-design process for further discussion: the importance of interprofessionalism; the close link between leadership and management; the strength of the co-design approach; comparison with other leadership competency framework; and the relevance of this LMP to other settings.

Interprofessionalism in health leadership training

In the initial planning for the LMP, we decided to select only medical professionals as study participants, largely based on feasibility. Reaching saturation in the qualitative studies across multiple diverse professional cadres was considered too difficult with limited time and resources. Similarly, there were concerns about designing the LMP to be interprofessional from the start, specifically that integrating a new topic of undergraduate training into multiple curricula and timetables simultaneously, and resourcing delivery to large numbers of students, might be overwhelming. The challenges of interprofessional learning are well documented (Aldriwesh et al., Citation2022).

Throughout the qualitative study and co-design process, however, the central importance of interprofessionalism to leadership development was repeatedly raised. All health professionals require leadership capabilities, and power in health systems is commonly shared between professional cadres, which must collaborate to reach consensus on decisions and reform (NHS Improvement, Citation2019). Our research did not encounter the hostility between professional cadres that has previously been reported (Frenk et al., Citation2010; Sexton & Orchard, Citation2016). The opposite was in fact observed, with several medical participants in the qualitative study expressed the need for more nurses in senior leadership roles. Interprofessional learning would not only enable the development of skills in teamwork, communication, and group dynamics, but also broader skills in affective domains, such as resilience, confidence and change agency, all important in leadership within health systems (Stephens & Ormandy, Citation2018).

The link between leadership and management

Expanding the focus of the LMP from leadership to include management was a second important evolution in its scope. The original emphasis on leadership stemmed from the programme’s goal of strengthening health systems, on the premise that this could only be achieve through the successful implementation of change, which requires effective leadership (Heifetz, Citation1994). While Martin and Learmouth (Citation2012) argue that leadership can be considered ‘substantively different’ from management, a more common view is that the two are intimately intertwined (Fernandez et al., Citation2010).

The findings of this research support the view that it can be detrimental to separate leadership development from management skill training. The qualitative studies found that management attributes, such as being organised and coordinating teams, were viewed as essential to effective leadership (Johnson, Sahr, et al., Citation2021). The scoping review found project management to be among the top three topics taught on leadership programmes in the region (Johnson, Begg, et al., Citation2021). During the development of this LMP, the co-design team put an early emphasis on key management competencies and suggested the course be labelled a leadership and management programme. As Kruk et al. (Citation2018, p. e1232) have pointed out, achieving reforms requires not only the leadership ability to set a vision but also the management skills ‘to effectively use available resources to realise the vision’. This requires us to develop what Bolden (Citation2011) calls a ‘leader manager’. The integration of leadership and management has implication not only for training but also competency frameworks, role descriptions, and the shaping of professional identities.

Strength of the co-design approach

The study used co-design methods, which are intended to enable service providers and users to achieve more together than they can apart, and ultimately to positively transform the service that is being designed (Heaton et al., Citation2016). Ward et al. (Citation2018) found that in health care settings, co-design methodologies can help to ensure that interventions are designed around everyday realities, maintain focus on their intended purpose, and have a stronger drive for implementation.

This study adopted the principles of co-design by actively including students, recent graduates, faculty, and frontline health workers. They took roles that variously included participants in the qualitative studies, on the design team, and through the consultation exercise. As anticipated by Ward, we found that co-design strengthened the LMP in several ways. The expansion of the programme remit to be interprofessional and to include management was a direct consequence of a co-design approach. We were also able to shape the learning content and methods around feedback from a wide range of stakeholders. We believe the co-design approach will also pay dividends during the implementation phase, since faculty and students now have greater ownership of the LMP and should therefore be more enthusiastic to engage in it. Even greater user involvement, such as student representation on the design team, would have been optimal.

Kern’s model for curriculum development (Thomas et al., Citation2016) was well aligned to the principles of co-design as it includes frequent consultation with students and other stakeholders. We found the emphasis on an initial needs analysis helped to maintain a focus on the local context, while the iterative nature of the model encouraged meaningful consultation. This enabled feedback to be continuously incorporated into the design while keeping all aspects of the programme aligned.

Comparison to existing leadership development frameworks

Several leadership competency frameworks for health professionals have been developed in international settings, primarily in the global North and aimed for specific cadres (Albetkova et al., Citation2019; Bender et al., Citation2019; Keijser et al., Citation2019). An example is the CanMEDS framework from the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada (Citation2015), that lists being a leader as one of seven key domains of physician competency, under which there are key concepts such as priority setting and negotiation. There are few frameworks that are interprofessional (NHS Improvement, Citation2019), and only one LMP in the scoping review clearly referenced a competency framework from the region (Foster & Moore, Citation2017).

We chose to develop our learning objectives inductively for this LMP to ensure relevance to the context. Our learning objectives ultimately share many common features with other leadership frameworks, such as managing people and projects, delivering change, and role modelling. The emphasis of our LMP’s learning objectives on being proactive, supporting juniors, and building networks reflects the contextual challenges we identified.

Relevance to other settings

This LMP joins an assemblage of new leadership development initiatives for health professionals in Sub-Saharan Africa and is broadly in line with their approaches (Doherty et al., Citation2018; Kebede et al., Citation2010; Kwamie et al., Citation2014). One distinctive feature is that it is aimed at undergraduates, which was the target group for only one of the 26 LMPs in the scoping review (Najjuma et al., Citation2016). The drive for stronger health professional leadership is not unique to Sub-Saharan Africa. As the global commission on health professions education noted, ‘In almost all countries, the education of health professionals has failed to overcome dysfunctional and inequitable health systems’ (Frenk et al., Citation2010, p. 1926). Stronger health systems leadership is critical in all settings to direct, navigate, and implement change.

While our LMP was intentionally designed for specific contextual factors in Sierra Leone, many aspects will be relevant in other settings, particularly other low- and middle-income countries. Our model helps to address barriers identified by other LMPs in the region, such a lack of sustainability due to high cost (Nakanjako et al., Citation2015) and the need to embed programmes within national institutions (Mutale et al., Citation2017). The LMP’s particular emphasis on building networks to protect from retribution is novel, but may be less important in settings where there are stronger regulations and whistle-blower protections. Similarly, the focus on being proactive may be most relevant in health systems with high levels of donor dependency, and the discussions on ethics most important in settings with significant corruption. Shaping leadership and interprofessionalism as core health professional identities are universal priorities (Frenk et al., Citation2010), as well as strengthening capabilities to lead change, manage others, and mentor juniors (Matsas et al., Citation2022; NHS Improvement, Citation2019).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study and curriculum include the use of underlying educational and leadership theory. Design was also informed by a scoping review and qualitative research, ensuring it was evidence-based and contextually adapted. Stakeholder engagement and ownership of the LMP were strong, further facilitated by a design process that extended over a significant period. Many of the lessons from previous LMPs were adopted, including avoiding reliance on external funds and integrating it into existing national institutions. Overall, the LMP has potential relevance to other settings and to other types of training.

The work is limited by being focused on one specific context. The qualitative study was also only of doctors and not other health professional cadres, giving the design a medical bias. The identification of qualitative study participants by two authors (O.J. and F.S.) using a purposive sampling and snowballing approach may also have introduced bias to the sample of doctors interviewed. During the consultation stage, some organisations were approached but a consultation meeting could not be arranged, for example the Nursing & Midwifery Association, leaving those groups unrepresented. The design process was reliant on a grant-funded researcher to facilitate it, raising questions of sustainability and replicability without external resources. Finally, the programme has not yet been implemented or evaluated in full, as at the time of publication it was in the process of being submitted to academic committees for approval, with follow up research planned.

The lead author (O.J.)’s position is both a strength and a potential limitation to the research. His three years of prior experience working in the health system in Sierra Leone gave him a deeper understanding of the context. This experience also generated prior relationships with interview participants and design team members that they said facilitated their recruitment and open engagement. Being from Europe and having qualifications as a medical doctor may also, however, have introduced bias into how participants presented their views or into how the lead author (O.J.) interpreted the qualitative data.

Conclusion

There has been growing emphasis in recent years placed on the importance of effective leadership to strong and resilient health systems in all settings. However, studies on health leadership training programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa have shown many to lack an explicit foundation in leadership theory or adequate adaptation to ensure sustainability and local relevance. This study documented a comprehensive design process for an undergraduate health LMP that was based on theory and on both context-specific and international evidence, and built with faculty ownership and sustainability as explicit objectives. In so doing, it provides a model for how the leadership capabilities of health professionals can be strengthened. It also provides specific lessons learned that can be used for similar design processes, including the use of virtual meetings and integration with academic research. The LMP design can be useful not only in the Sub-Saharan Africa region but also in other settings where relevant health system challenges are also being experienced.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (11.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: NS is the director of the London Safety and Training Solutions Ltd, which offers training in patient safety, implementation solutions and human factors to healthcare organizations and the pharmaceutical industry. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulmalik, J., Fadahunsi, W., Kola, L., Nwefoh, E., Minas, H., Eaton, J., & Gureje, O. (2014). The mental health leadership and advocacy program (mhLAP): A pioneering response to the neglect of mental health in anglophone West Africa. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-5

- Ahmed, S. A., & Oyeyemi, T. (2020). Interprofessional education/practice and team based care: Policy action paper. Social Innovations Journal, 3. https://socialinnovationsjournal.com/index.php/sij/article/view/497

- Albetkova, A., Chaignat, E., Gasquet, P., Heilmann, M., Isadore, J., Jasir, A., Martin, B., & Wilcke, B. (2019). A competency framework for developing global laboratory leaders. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(AUG), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00199

- Aldriwesh, M. G., Alyousif, S. M., & Alharbi, N. S. (2022). Undergraduate-level teaching and learning approaches for interprofessional education in the health professions: a systematic review. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03073-0

- Bender, M., L’Ecuyer, K., & Williams, M. (2019). A clinical nurse leader competency framework: Concept mapping competencies across policy documents. Journal of Professional Nursing, 35(6), 431–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2019.05.002

- Bolden, R., Hawkins, B., Gosling, J., & Taylor, S. (2011). Exploring leadership: Individual, organizational and societal perspectives. Oxford University Press.

- Ciccone, D. K., Vian, T., Maurer, L., & Bradley, E. H. (2014). Linking governance mechanisms to health outcomes: A review of the literature in low- and middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 117, 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.010

- Cleary, S., Du Toit, A., Scott, V., & Gilson, L. (2018). Enabling relational leadership in primary healthcare settings: Lessons from the DIALHS collaboration. Health Policy and Planning, 33(suppl_2), ii65–ii74. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx135

- Colvin, J. W., & Ashman, M. (2010). Roles, risks, and benefits of peer mentoring relationships in higher education. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 18(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611261003678879

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2012). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230153

- Currie, G., & Lockett, A. (2007). A critique of transformational leadership: Moral, professional and contingent dimensions of leadership within public services organizations. Human Relations, 60(2), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707075884

- Doherty, J., Gilson, L., & Shung-King, M. (2018). Achievements and challenges in developing health leadership in South Africa: The experience of the Oliver Tambo Fellowship Programme 2008-2014. Health Policy and Planning, 33(suppl_2), ii50–ii64. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx155

- Downing, J., Leng, M., & Grant, L. (2016). Implementing a palliative care nurse leadership fellowship program in Uganda. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43(3), 395–398. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.395-398

- Fernandez, S., Cho, Y. J., & Perry, J. L. (2010). Exploring the link between integrated leadership and public sector performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2), 308–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.01.009

- Footer, C. B., Tsegaye, H. S., Yitnagashaw, T. A., Mekonnen, W., Shiferaw, T. D., Abera, E., & Davis, A. (2017). Empowering the physiotherapy profession in Ethiopia through leadership development within the doctoring process. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(March), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00051

- Foster, A. A., & Moore, C. (2017). A formative assessment of nurses’ leadership role in Zambia’s community health system. World Health & Population, 17(3), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.12927/whp.2017.25305

- Frenk, J., Chen, L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cohen, J., Crisp, N., Evans, T., Fineberg, H., Garcia, P., Ke, Y., Kelley, P., Kistnasamy, B., Meleis, A., Naylor, D., Pablos-Mendez, A., Reddy, S., Scrimshaw, S., Sepulveda, J., Serwadda, D., & Zurayk, H. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lancet, 376(9756), 1923–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

- Gathu, C. (2022). Facilitators and barriers of reflective learning in postgraduate medical education: A narrative review. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 9, 238212052210961. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205221096106

- Gilmartin, M. J., & D’Aunno, T. A. (2007). Leadership research in healthcare. Academy of Management Annals, 1(1), 387–438. https://doi.org/10.5465/078559813

- Goldstone, C., & Ntuli, A. (2016). Albertina Sisulu Executive Leadership Program in Health (ASELPH) Final Evaluation Report. September. www.aselph.co.za

- Government of Sierra Leone. (2016). Human resources for health country profile: Sierra Leone. Directorate of Human Resources for Health, Sierra Leone, December, 1–71.

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are Enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Heaton, J., Day, J., & Britten, N. (2016). Collaborative research and the co-production of knowledge for practice: An illustrative case study. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0383-9

- Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers (1st ed.). Harvard University Press.

- International QSR. (2018). Nvivo (No. 12).

- Johnson, O., Begg, K., Kelly, A. H., & Sevdalis, N. (2021). Interventions to strengthen the leadership capabilities of health professionals in Sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. Health Policy and Planning, 36(1), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa078

- Johnson, O., Sahr, F., Begg, K., Sevdalis, N., & Kelly, A. H. (2021). To bend without breaking: A qualitative study on leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone, 1–15.

- Johnson, O., Sahr, F., Sevdalis, N., & Kelly, A. H. (2022). Exit, voice or neglect: Understanding the choices faced by doctors experiencing barriers to leading health system change through the case of Sierra Leone. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 2(July), 100123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100123

- Kahan, B. C., Cro, S., Doré, C. J., Bratton, D. J., Rehal, S., Maskell, N. A., & Rahman, N. (2014). Theory of Change: A theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials, 15(267), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

- Kebede, S., Abebe, Y., Wolde, M., Bekele, B., Mantopoulos, J., & Bradley, E. H. (2010). Educating leaders in hospital management: A new model in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22(1), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzp051

- Keijser, W. A., Handgraaf, H. J. M., Isfordink, L. M., Janmaat, V. T., Vergroesen, P. P. A., Verkade, J. M. J. S., Wieringa, S., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2019). Development of a national medical leadership competency framework: The Dutch approach. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1800-y

- Kirkpatrick, D. J., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Kotter, J. (1982). The general managers. Free Press.

- Kruk, M. E., Gage, A. D., Arsenault, C., Jordan, K., Leslie, H. H., Roder-DeWan, S., Adeyi, O., Barker, P., Daelmans, B., Doubova, S. V., English, M., Elorrio, E. G., Guanais, F., Gureje, O., Hirschhorn, L. R., Jiang, L., Kelley, E., Lemango, E. T., Liljestrand, J., … Pate, M. (2018). High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. The Lancet Global Health, 6(11), e1196–e1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

- Kwamie, A., van Dijk, H., & Agyepong, I. A. (2014). Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: Realist evaluation of the Leadership Development Programme for district manager decision-making in Ghana. Health Research Policy and Systems, 12(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-12-29

- Maini, R., Mounier-Jack, S., & Borghi, J. (2018). How to and how not to develop a theory of change to evaluate a complex intervention: Reflections on an experience in the Democratic Republic of Congo. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000617. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000617

- Martin, G. P., & Learmonth, M. (2012). A critical account of the rise and spread of ‘leadership’: The case of UK healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 74(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.002

- Matsas, B., Goralnick, E., Bass, M., Barnett, E., Nagle, B., & Sullivan, E. E. (2022). Leadership development in U.S. Undergraduate medical education: A scoping review of curricular content and competency frameworks. Academic Medicine, 97(6), 899–908. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004632

- Mintzberg, H. (1998). Covert leadership. Notes on Managing Professionals Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business Review.

- Muhimpundu, M. A., Joseph, K. T., Husain, M. J., Uwinkindi, F., Ntaganda, E., Rwunganira, S., Habiyaremye, F., Niyonsenga, S. P., Bagahirwa, I., Robie, B., Bal, D. G., & Billick, L. B. (2018). Road map for leadership and management in public health: A case study on noncommunicable diseases program managers’ training in Rwanda. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 57(2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2018.1552178

- Musoke, R., Chimbaru, A., Jambai, A., Njuguna, C., Kayita, J., Bunn, J., Latt, A., Yao, M., Yoti, Z., Yahaya, A., Githuku, J., Nabukenya, I., Maina, J., Ifeanyi, S., & Fall, I. S. (2019). A public health response to a mudslide in Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2017: Lessons learnt. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 14(2), 256–264. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2019.53

- Mutale, W., Vardoy-Mutale, A. T., Kachemba, A., Mukendi, R., Clarke, K., & Mulenga, D. (2017). Leadership and management training as a catalyst to health system strengthening in low-income settings: Evidence from implementation of the Zambia Management and Leadership course for district health managers in Zambia. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0174536. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174536

- Najjuma, J. N., Science, B., Ruzaaza, G., Phc, M., Groves, S., Maling, S., Chb, M. B., Psychiatry, M., Mugyenyi, G., Chb, M. B., & Mmed, O. (2016). Multidisciplinary leadership training for undergraduate health science students may improve Ugandan healthcare. African Journal of Health Professions Education, 8(2), 184–188. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.2016.v8i2.587

- Nakanjako, D., Namagala, E., Semeere, A., Kigozi, J., Sempa, J., Ddamulira, J. B., Katamba, A., Biraro, S., Naikoba, S., Mashalla, Y., Farquhar, C., & Sewankambo, N. (2015). Global health leadership training in resource-limited settings: A collaborative approach by academic institutions and local health care programs in Uganda. Human Resources for Health, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-015-0087-2

- NHS Improvement. (2019). Clinical leadership – A framework for action A guide for senior leaders on developing.

- Norcini, J., Anderson, M. B., Bollela, V., Burch, V., Costa, M. J., Duvivier, R., Hays, R., Palacios Mackay, M. F., Roberts, T., & Swanson, D. (2018). 2018 Consensus framework for good assessment. Medical Teacher, 40(11), 1102–1109. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016

- Ostrom, E. (1996). Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development, 24(6), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

- Sexton, M., & Orchard, C. (2016). Understanding healthcare professionals’ self-efficacy to resolve interprofessional conflict. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(3), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2016.1147021

- Sibiya, M. N., Ngxongo, T. S. P., & Beepat, S. Y. (2018). The influence of peer mentoring on critical care nursing students’ learning outcomes. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 11(3), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-01-2018-0003

- Stephens, M., & Ormandy, P. (2018). Extending conceptual understanding: How interprofessional education influences affective domain development. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(3), 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1425291

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. (2015). CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Evolving the CanMEDS Framework. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/canmeds/canmeds2015/overview

- Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., & Chen, B. Y. (2016). Curriculum development: A Six-step approach for medical education (3rd ed., Issue February). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Torre, D., Rice, N. E., Ryan, A., Bok, H., Dawson, L. J., Bierer, B., Wilkinson, T. J., Tait, G. R., Laughlin, T., Veerapen, K., Heeneman, S., Freeman, A., & van der Vleuten, C. (2021). Ottawa 2020 consensus statements for programmatic assessment – 2. Implementation and practice. Medical Teacher, 43(10), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2021.1956681

- University of Sierra Leone. (2019). Overview of curriculum review process and curriculum review templates (Vol 1).

- Walsh, S., & Johnson, O. (2018). Getting to zero: A doctor and a diplomat on the Ebola frontline. Zed Books.

- Ward, M. E., de Brún, A., Beirne, D., Conway, C., Cunningham, U., English, A., Fitzsimons, J., Furlong, E., Kane, Y., Kelly, A., McDonnell, S., McGinley, S., Monaghan, B., Myler, A., Nolan, E., O’Donovan, R., O’Shea, M., Shuhaiber, A., & McAuliffe, E. (2018). Using co-design to develop a collective leadership intervention for healthcare teams to improve safety culture. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1182–1117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061182

- World Health Organization. (2007). Towards better leadership and management in health: Report of an international consultation on strengthening leadership and management in low-income countries. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70023