ABSTRACT

This article ethnographically traces the performance of data collection and analysis for a cancer cost-of-illness study in an East Indian Cancer hospital. By reflecting on my experience in this project, I show how the hospital’s obligations for philanthropic and business self-sustainability spatially and temporally structured data in a way that produced the conditions of possibility for what was able to be made knowable of patients’ experiences in cancer health economics. While collecting and analysing data within the spatial and temporal structuring of this self-sustainable hospital, I argue that our research team attempted to craft an ethical epistemology by incorporating the unique realities of Indian cancer patients based upon assumptions made from our tacit knowledge. Specifically, we called upon this knowledge to exercise a form of tacit epistemological ethics for patients existing in an in-between space of classification within Euro-North America cancer health economics frameworks. Finally, I suggest that in light of an attempt to produce a more ethical economic logic, the results of the cost-of-illness analysis are ultimately returned to larger conditions of possibility within austere health systems and Euro-North America health economics frameworks.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In this article, I reflect on my experience working in a team of cancer health professionals in a philanthropic East Indian cancer hospital in the summer of 2018. Specifically, I ethnographically trace how our team retrieved and analysed the necessary data to conduct a cost-of-illness study: a health economics methodology that calculates the total cost of a specific illness based upon variables of expenditure during that illness (Jo, Citation2014). In our cost-of-illness study, the hospital’s spatial and temporal organisation of data produced constrained conditions of possibility for which experiences of cancer patients our team was able to analyse. Amidst this context, use this line as this article offers a reply to Adams (Citation2016) prompt which asks us: ‘what can be made of the stories – the empirical events, experiences, and myriad occurrences and facts – that do not lend themselves to being counted’ (p. 12)? This article shows how our team employed a tacit knowledge that made assumptions of the experiences of Indian cancer patients which did not lend themselves to being counted in order to guide how we analysed what was quantifiable. These assumptions took the form of a tacit epistemological ethics that attempted to make what was otherwise illegible within Euro-North American health economic methodologies legible.

The hospital discussed in this article was founded with a 75 million USD one-off-grant. This money was meant to fund the hospital’s founding costs and its first 2 years of operational costs, at which point the hospital was expected to become financially ‘self-sustainable’ while remaining partially philanthropic. This means that the hospital is responsible for both producing its own revenue and for providing care to those who cannot afford cancer treatment. Compared to models of health philanthropy that rely upon (often private sector) donor support, this hospital is required to fulfil both the philanthropic and business obligations of running a hospital. On the one hand, the hospital’s dual philanthropic and business obligations mean that the hospital is able to provide care to patients which may otherwise not receive care; on the other hand, these dual obligations have resulted in a spatial and temporal segregation of philanthropic and financial data that produces the conditions of possibility for which experiences of cancer patients were possible for our team to analyse.

The philanthropic and financial data sources in this hospital are spatially separated across unique departments and articulate different temporal logics in their record keeping. The spatial separation of data places a strain on the capacity required for health economists to conduct research because it requires both retrieving data from multiple departments and then modifying that data so it is comparable. The different temporal logics of these data sources creates an analytical limit for health economists because it does not allow for a calculation of the cost-of-illness to patients at specific stages of the cancer treatment pathway. Specifically, philanthropic data shows how much the patient has been subsidised throughout their entire treatment, but does not disaggregate this data to show when; comparatively, financial data provides itemised invoices for each unique inpatient and outpatient admission. This means that our team’s results could only calculate the total cost-of-illness to the patient for their entire treatment, and limited the ability of our results to inform at what stages of the treatment pathway patients may become increasingly financially vulnerable. Therefore, the spatial and temporal structure of these data sources makes it challenging to impossible to produce insights that can specifically target moments when a patient may face catastrophic health expenditure, but it meets the minimum administrative needs of philanthropic and business self-sustainability so that benevolence can be demonstrated while capital can be accumulated (Bharadwaj, Citation2009). This analysis provides the context to understand what lends itself to being counted when calculating the cost of cancer to patients at this self-sustainable hospital.

To make sense of what did not lend itself to being counted, our research team attempted to negotiate an ethical economic logic when conducting our data analysis. To do this, we attempted to mediate between the unique costs-of-illness to Indian cancer patients and Euro-North American health economics methodologies by employing our tacit knowledge about these costs. In some cases, we assigned patients to different cost categories that we felt more accurately represented their experience of paying for the costs of cancer; however, in other cases, despite our team’s attempt to analyse different costing categories that may better capture the cost of cancer to patients, our results could only calculate the cost-of-illness to the hospital but not the cost-of-illness to the patient. Therefore, our tacit knowledge constructed our methodology in a way that attempted to enact an ethical health economics epistemology by pushing back against Euro-North American frameworks which often do not make space for the unique experiences of Indian cancer patients. Yet, this still pushed up against its limits when it confronted the different contours of a spatialised and temporalised data infrastructure made to support the pastoral philanthropic form of capital accumulation that had been rendered imaginable. This shows that what happens to the stories which do not lend themselves to being counted is that forms of mediation such as tacit epistemological ethics can work to bring them into the gaze of metrics, yet experience’s infinite excess will always remain in part a haunting, spectral possibility to the finiteness contained within and constrained through metrics.

This article is based upon my reflections of working with this team of cancer health professionals. While I claim to ethnographically trace how our team retrieved and analysed data, I was not recording field notes during this experience. Therefore, I use the word ethnographic insofar as I have ‘embodied’ this experience as a member of the team (Holmes, Citation2013). In lieu of fieldnotes, many of my reflections have been made by returning to the working documents that our team used to conduct this analysis, which has triggered a process of recollection of the experiences that our team went through as I have furthered my graduate training in medical anthropology. A proposal to write this article was submitted to the hospital detailed in this paper. Because it did not disclose information about patient identities it was deemed unnecessary to subject the proposal to any type of ethical review.

The role of social science in understanding the cost of cancer

On metrics:

Social scientists remind us that throughout history the objectivity of metrics remains malleable to the mutually contingent ideological and technocratic hegemonies of the time. Adams (Citation2016) traces the origin of global health metrics to ‘colonial health programs that gave birth to statistics practices’ to manage populations (p. 3). What were seen as ‘useful’ and ‘methodologically rigorous’ metrics were influenced through ‘administrative and worldly aspirations’ (Adams, Citation2016, p. 5). Contemporary analyses of global health metrics have focused on disability and or quality adjusted life years, often in relation to vertically oriented communicable disease programs. Scholars have traced how these metrics work to ‘abstract quality of life and turn it into a fiscally meaningful form’ (p. 29). Doing so ‘subordinates life to its role in intervention/investment opportunities’ rather than delivering health equity (Adams, Citation2016, p. 43). Therefore, today’s metrics are frequently being moulded into tools that orchestrate ‘new conduits for a biopolitical economy, becoming key to the forms of sovereignty that arise with global health and its dreams of health for all;’ Adams concludes that ‘metrics indirectly become the micro practices of neoliberalism’ (Citation2016, pp. 37, 39).

In other words, while metrics are often framed as apolitical, the political-ideological infrastructures producing the conditions of possibility for what metrics can make known makes them ‘a form of politics in their own right’ (Adams, Citation2016, p. 9). Tichenor’s (Citation2020) work demonstrates that the tension with metrics exists in the process of their production; they ‘translate assumed realities into numbers’ (p. 1). Metrics constantly work to stabilise ‘some of the background noise’, reducing the ‘randomness and chaos’ of everyday life (Adams, Citation2016, p. 35, 20). When experiences are reduced to create metrics a ‘wide range of phenomena are pushed inside and outside of visibility … these acts of recognition, exclusion, and inclusion’ (re)stabilise the political-ideological infrastructures validating metrics, while further destabilise the realities of the poor when left beyond the scope of metrics (Adams, Citation2016, p. 8). What is at stake in the process of translation necessary to produce metrics are the emergent transnational forms of the ‘governmentalisation of living, in the course of which the social and personal consequences of living with disease come to be an object of political concern’ able to be addressed or disregarded based upon the perceived biological worthiness of the citizen (Wahlberg & Rose, Citation2015, p. 60).

Anthropological attunement to the practices of data collection and dissemination both cohere with yet depart from these frameworks in nuanced ways. For example, Tichenor’s analysis of a malaria program in Senegal shows how, on the one hand, data remains ‘conditioned by and reifies preconceived notions’ of political-ideological infrastructures; yet, on the other hand, the process of producing metrics requires specific performances and it is within these that power can be contested (Tichenor, Citation2017). Tichenor shows that, as a performance, data dissemination is more likely to reproduce than open possibilities for data, yet these locations of performance are also where data can become malleable. In this case, this article focuses on the preceding performance of research production, including data collection and analysis. This case will show that the affective evidence within ‘stories’ – previously characterised as a paradoxical form of data that is at once ‘victoriously’ avoided while maintaining a ‘haunting’ presence as a needed ‘spectral possibility, perpetuating a fantasy of intimacy and social responsibility’ – can also be used to negotiate with the cracks and the fault lines in the reigning political-ideological frameworks that both reproduce but also expand what ‘ought’ to be counted (Adams, Citation2016, p. 48). To comprehend how this was made possible in our case, it is important to first review the unique aspects involved in quantifying the economics of cancer.

Quantifying cancer:

Public expenditure on cancer in India and globally remains disproportionately low compared to the burden of morbidity and economic expenditure. Globally, social scientists have attributed cancer’s lack of funding to a ‘charismatic gap’ (Herrick, Citation2017). Despite cancer’s ‘quantitative measures of severity’, it ‘fails to ignite a commensurate response in affective, political, or financial terms’ (Herrick, Citation2017, p. 6). Herrick explains how the inability to generate charisma to prioritise funding for cancer is due to temporality, risk, and lexicon: historically, ‘charismatic advocacy work [was] founded on “a sense of moral urgency, a fear of contagion, the risk of an exponential rise in cases, and a mounting … transnational security threat that could destabilise societies” ’ (p. 12). Elsewhere, Herrick (Citation2020) states candidly that ‘the optics of the ‘NCD crisis’ are wrong’ (p. 1). Subsequently, cancer has become ‘the leading cause of catastrophic health spending, distress financing, and increasing expenditure before death in India’ (Smith & Mallath, Citation2019, p. 1).

It is within the context of this funding gap that health economists have begun to attempt to produce metrics that can contribute to making fiscal arguments about the value of funding cancer care. However, in the process of producing metrics about cancer health economics in India, these researchers must address the ‘heterogeneous and dynamic environments’ patients navigate to receive care (Sirohi et al., Citation2018, p. 1). This includes patients commonly travelling hundreds of kilometres to receive treatment, attending multiple treatment facilities, frequently abandoning and restarting treatment, and or altogether foregoing treatment following diagnosis. These factors not only increase the cost of cancer care in India but create an array of variables needing to be considered when calculating a patient’s cost-of-illness. As a result many health economics studies do not measure both the direct and indirect costs of treatment, respectively including the therapeutic costs and the travelling, lodging, opportunity costs of missing work, and other costs. At best, India has a fragmented picture of the cost of cancer across a number of individual research studies often inconsistently measuring direct or indirect expenditures (for example, see: Ganapule et al., Citation2017; Jain & Mukherjee, Citation2016; Ramireddy et al., Citation2017).

The importance to measure both direct and indirect expenditures in health economics studies is not only to provide information for health systems planning but also to identify the social groups most vulnerable. Most commonly, those with the highest indirect expenditures are those with increased chances of mortality, lack of treatment follow up, and potential future delays in diagnosis (Mallath et al., Citation2014; Mohanti et al., Citation2011). Particularly when indirect expenditures are not measured, this misses how cancer can ‘be communicable in specific environments’ of socio-economic precarity (Seeberg & Meinert, Citation2015, p. 1). Indirect expenditures provide information on the ways in which cancer is ‘para-communicable – chronic conditions that may be materially transmitted … with unequal and compounding effects for historically situated groups of people’ (Moran-Thomas, Citation2019, p. 489). To account for these groups, measuring indirect costs also requires going beyond a survey methodology – often at the least subject to recall bias. Caduff et al. (Citation2019) explain how uncovering indirect expenditures is usually most comprehensive by conducting interviews, because financial costs often manifest themselves in ‘oblique’ ways in patient histories.

Due to the large research capacity and funding required, this type of research is rarely performed. The structural barriers to comprehensively measuring the direct and indirect costs-of-illness for Indian cancer patients reflects how Euro-North American research methods ‘often exist in an epistemological incommensurability with the unique needs produced through the life words of cancer patients’ (Smith, Citation2022, p. 3). Health economics methodologies for calculating costs-of-illness were not designed to accurately calculate the unique care pathways seen in India. As such, the discipline of health economics must navigate an epistemological gap when attempting to measure the realities of cancer patients in India.

Health economists are not unaware of these concerns. Experts have remarked how current data availability is ‘inadequate to feed into sound policymaking’ and have called for the ‘development of a robust data infrastructure that is currently absent … particularly for public health programs whose costs and benefits would have to be followed over longer periods’ for diseases like cancer (Prinja et al., Citation2015, p. 1; Rao et al., Citation2018, p. 6). As this article will show, these admissions of metrical incompleteness open spaces to tinker with health economics methodologies. To understand how our research team negotiated with health economics methodology, finally, it is important to understand how the cancer hospital’s self-sustainable spatial and temporal data logics produced conditions of possibility for what our team was able to analyse.

Self-sustainable cancer spaces:

Under colonial rule in India, the British government did not invest in public health services beyond a focus ‘on keeping epidemics at bay;’ instead, philanthropic trusts of Indian businesses played a large role in providing access to health services (Amrith, Citation2009, p. 8; Vevaina, Citation2018). Following independence, the post-colonial state’s claimed focus on health led to a decline in the role of philanthropic health care (Palsetia, Citation2005). However, since the late twentieth century, neoliberal trade policies have led to a decrease in the role of the public sector, and an increase in the role of private and philanthropic sectors (Baru, Citation1998). It is within this context that the self-sustainable cancer hospital at stake in this article was founded.

In documenting the founding of philanthropic cancer hospitals in India, social scientists have shown how acquiring government permissions and funding requires various strategic approaches. Sivaramakrishnan (Citation2019) explained how founding The Cancer Institute, Chennai required ‘irritating the state;’ that is, receiving funding was not because of the concern of cancer, but because of activists’ ability to draw together the interests of ‘middle-class women, urban philanthropy, and … male political leaders and health officials’ (p. 1). In Mumbai, the philanthropically established Tata Memorial Hospital was funded through ‘the Tatas’ and Government of India’s mutual interests in nuclear research’ drawing upon business incentives of philanthro-capitalism and state interests of post-colonial scientific nationalism (Smith, Citation2022, p. 5).

What is important about the existence of philanthropy is not only the role it plays in providing access to care, but also its contingency on a continuous performance to ‘irritate’ or demonstrate ‘relevance’ to funders. As Banerjee shows through an ethnography of a philanthropic cancer palliation organisation in Delhi, the requirements of funding confine these organisations to ‘a single mandate’ in order to reproduce their relevance for philanthropic funds (Banerjee, Citation2019). However, in this case the self-sustainable hospital is confined to two mandates: philanthropy and business. This form of self-sustainable philanthropy creates further conditions of possibility for what type of care is possible to provide, and how data about that care is produced. The hospital operates on a financial model that provides ‘state-of-the-art’ facilities in order to both attract high-income patients, but also use high-income patient payments to be able to subsidise care for the middle-class and poor to receive an equal quality of treatment. The hospital allows patients to select ‘private’ or ‘general’ care; the former providing a secluded suite and the latter a hospital ward. Private patients are charged at a higher margin, and the surplus is channelled back to subsidise qualified general category patients. The hospital also hosts a team of social workers that work with qualified patients to acquire documents and apply to other private and public philanthropies dedicated to cancer.

It is through the needs of philanthropic and business self-sustainability that this hospital’s accounting system becomes spatially and temporally structured in a way that comes to articulate a logic of ‘what counts as health’ (Adams, Citation2016). This article specifically focuses on the space that this data inhabits in the hospital to understand how ‘spaces [of data] constitute as well as represent social and cultural existence;’ in other words, to understand how spaces of data can be influenced by social life, yet also produce its possibilities and limitations (Prior, Citation1988, p. 90). In the hospital at stake in this article, it is the dual obligations of philanthropy and business that influence the spatial separation of data that made possible and limited our research team’s analysis. I do not claim that the spatial separation of data in this hospital is necessarily unique; many research teams across the world have to consult multiple departments in hospitals for multiple sources of data while conducting studies. However, following Street (Citation2012), focusing on ‘heterotopic spaces’ reveals ‘the temporal multiplicities that reside in hospitals’ which further work to make possible and limit what can be analysed from data (p. 45). Therefore, by working through the hospital’s spaces of data it helps me to be attuned to the specific temporal spectrums of philanthropy, capital, and patient data that take shape in these spaces. This approach unveils the logic of the data’s structure that resulted in certain experiences of patients not being commensurable in our research team’s health economics analysis.

The cost of cancer: an exploration of the representation of patients’ lives within bills

Now, I turn to our team’s process of collecting and analysing data in this cost-of-illness study. First, I detail how our team retrieved the required data for the study. Specifically, I detail how the hospital’s logic of self-sustainability had spatially structured the data. For our research team, identifying and locating the data required to conduct the study required translating data into comparable forms and strained our team’s capacity. For the hospital, the data was spatially organised in a way that made the necessary data available within different departments to fulfil the hospital’s philanthropic and business obligations. Second, I detail how the organisation of the data according to the hospital’s philanthropic and business obligations limited the ability of our analysis to calculate the cost-of-illness to patients due to the limited comparability of the data across departments. It was these limitations that prompted our research team to exercise an ethical epistemology based upon our tacit knowledge by reclassifying patients at the borders of costing categories.

Collecting data in self-sustainable spaces:

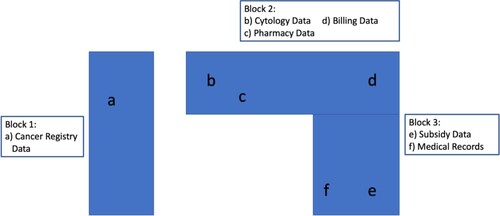

Performing a cost of illness study requires knowing which patients were treated for the particular cancer type being studied, knowing the cost of each patient’s treatment, and knowing each patient’s treatment pathway to be able to disaggregate costs to specific stages of the treatment pathway. However, each of these pieces of information were located in separate locations of the hospital (). Ultimately, our team consulted six departments across the hospital to locate the data. The spatial structure of data reflected financial and philanthropic obligations; financial data was located mainly within bills, data on philanthropic patient subsidies was located within the social works department, and other data beyond financial and philanthropic obligations was organised by medical departments. While securing access to data is a challenge for most rigorous data-driven studies, the conditions of access for our study were produced through the hospital’s need for financial and philanthropic self-sustainable engineering.

Sample selection:

The first step of the study was to identify which patients had been treated for the cancer type being studied. Our team was informed that all patients would have had cytology laboratory tests done at the hospital for the purpose of diagnosis. Upon retrieving the list of patients from cytology, the number of patients was remarkably low. Although correct that patients would need cytology to be done in order to be treated, not all patients had their cytology done in this hospital. The ‘heterogenous and dynamic care environments’ of cancer in India meant that many patients had their cytology previously done elsewhere.

Once realising the limitations of the cytology data, our team turned to the hospital’s administrative department which coordinates with India’s National Cancer Registry. For a patient to receive an initial consultation at the hospital, they must first register. Each patient registered is then recorded in the Cancer Registry. This department was able to provide a full list of patients of interest to the study.

Collecting costing data:

Next, we retrieved the bills of these patients from the hospital’s accounting system. To do this, we sent the billing department a list of patient IDs of interest to the study. Using this list, the accounting department provided our team with a full list of patient bills organised by in patient (IP) bills and outpatient (OP) bills. Each unique IP and OP visit produced a single bill. The act of generating unique bills for each IP and OP visit rather than a comprehensive patient bill is important for the hospital’s financial sustainability in cases where patients are likely to not follow up, abandon treatment, or come for one-off consultations. However, this also meant that our team had to aggregate billing information from each patient across IP and OP bills.

Further, to calculate the accurate cost of illness to the patient, we also retrieved data on patient subsidies received from philanthropic sources from the social works department. To ensure the philanthropic aims of the hospital, this data was held in a separate department than the billing data to monitor philanthropic activity. However, the data which was received from the social works department neither specified which bills the philanthropic funds had subsidised nor the date the subsidy had been issued to the patient. This meant that our team could include subsidies to calculate the total cost-of-illness to the patient, but could not use subsidy data to calculate which stages of the treatment pathway and or which treatments were most expensive to the patient.

Collecting data on patient treatment pathways:

To understand costs associated with different stages of the treatment pathway – for example, chemotherapy cycles 1, 2, etcetera – our team retrieved physician notes within the hospital’s electronic medical records. By comparing the date of each bill with the date of a physician note we then categorised each IP and OP bill to the treatment stage represented in physicians’ notes.

We also needed to categorise the types of services which were charged within each IP bill (i.e. chemotherapies, antibiotics, surgery, etcetera). To do this, we had to correlate which drugs were used for which services in order to disaggregate the total costs of IP bills. While the hospital’s IP bills would list drugs under one name, the privately-owned pharmacy within the grounds of the hospital often listed these drugs under their own brand name. This required consulting the pharmacy to clarify which drugs in the hospital’s bills correlated to the pharmacy’s drugs in order to determine the exact unit price.

Analysing data with self-sustainable sustainable origins:

Because of the unique experiences of cancer patients in India, it was often not possible to translate and analyse the data in a way that was commensurable with Euro-North American health economics methodologies. To demonstrate this, the following section details two desired outputs from our research team’s analysis, including calculating separate costs for private and general patients and calculating separate costs for each stage of patients’ treatment pathways.

Separate costs of private and general patients:

The first desired output of our analysis was to calculate separate average costs of treatment for private and general patients. As discussed above, the different treatment options of private and general are one of the mechanisms the hospital uses to sustain its financial and business obligations. However, due to the high costs of cancer treatment, it is common for patients to begin treatment in private care, and further down the line start to run out of funds and transition to general care (see: Pramesh et al., Citation2014). Because of this, many patients often switch from private to general categories during the course of their treatment. When calculating the total average costs of private and general treatments, this made our team have to decide which category the patient was better suited to by considering their individual case.

Some of these decisions were straightforward. For example, a patient with 10 IP admissions which was billed as private for the first admission and general for the next 9 would be categorised as a general patient. In other instances, decisions were not as straightforward. For example, a patient with two admissions as private and four admissions as general would require further analysis of the data. If the purpose of the private admissions were diagnostic, then the patient would be categorised as general because the majority of curative treatment – and therefore cost – would come from the following four general admissions. On the other hand, if the purpose of the private admissions were an extremely costly curative treatment, and the following general admissions were also curative but not as costly, our team assessed to what extent the entirety of the cost to the patient during treatment was completed within the private admissions as compared to the latter general admissions. However, in these cases, to understand the entirety of the cost to the patient during treatment our research team did not only consider the costs of private and general admissions, but also attempted to consider the patient’s travelling, lodging, and other opportunity costs, as well as likely other members of the family. To do this, we used patient bills and patient registrations to respectively inform the amount of time between each treatment and the patient’s place of residence, which allowed us to make assumptions about patients’ likelihood to return home and therefore the costs they would face during that time.

In the case of one private admission and nine general ward hospitalisations, we felt the best representation of the patient would be in the general category because an overwhelming majority of this patient’s bills were categorised as general. However, in other cases, we often did not feel it was an accurate representation of the patient’s experience of paying for care by classifying them based upon the proportion of the costs of bills that were private and general. In these instances, we operationalised a definition of ‘extent of treatment’ to mean the extent of the total cost of treatment to the patient. Therefore, even with only two private bills totalling slightly below 50% of a patient’s total expenditure they could still be categorised as a private patient. For example, to paraphrase a conversation I had with a colleague, when I asked them about the possibility of a patient travelling to and from to the hospital they replied ‘that part of India? I am surprised they came here. The transport would be terrible and I doubt they are returning home often’. In this case, although the patient’s private expenditures were below 50% of the total direct costs of treatment, we classified them as private. Assuming that the patient did not return home during their time as a private patient, we concluded that the patient would have incurred significantly more lodging, food, and opportunity costs during the period of time spent as a private patient than during the shorter periods of time between general admissions.

Calculating infections within treatment pathway stages:

A second desired output of our analysis was to calculate the average costs of specific stages of the treatment pathway; for example, unique costs for induction chemotherapy, chemotherapy cycle 1, etcetera. While each IP stay would usually represent a stage of the curative treatment pathway, its corresponding IP bill often revealed treatment beyond what was considered a part of ‘curative treatment’ for cancer. Specifically, costs of infection were often patients’ highest expenditure, and accounted for over 50% of total patient expenditure in the study (see: Mallath et al., Citation2014). Some infection costs occurred during unique admissions specifically for infections and were able to be measured independently; however, a significant amount of infection costs occurred during curative admissions which led them to be categorised as a stage of the curative treatment pathway rather than as a unique admission from infection.

Therefore, at times our results included the costs of infection within other ‘curative’ treatments. In response to this, we chose to disaggregate the cost of each IP bill by the type of service administered; for example, costs of chemotherapy, infection, and more. While doing this further strained the capacity of our team, it allowed for us to identify patients with the highest infection costs and at what locations of the treatment pathway these costs were incurred. Nonetheless, while performing this analytically may have helped to illuminate at what stages of the treatment pathway infection costs were the highest, these results remained far embedded into our analytical work. For example, when our team presented this work at a hospital round table this information formed 1 of roughly 40 slides. When this preliminary study was presented at a global health conference, the disaggregated results for each stage of the treatment pathway were not included at all (Smith et al., Citation2019). Further, despite disaggregating this data we were still not able to calculate the cost to the patient because the subsidy did not specify when it was issued. Therefore this also meant that it was not possible to conclude that if when subsidies were issued to patients it may have had an effect on avoiding situations of catastrophic healthcare expenditure.

The possibilities and limitations of making stories legible through tacit epistemological ethics in a self-sustainable cancer hospital

The self-sustainable cancer hospital had created unique departments, somewhat unwittingly, for each source of information to accomplish the goals of philanthropic and business self-sustainability. The organisation of data reflected a spatial and temporal engineering for self-sustainability, spatially separating the obligations of financial self-sustainability (bills), from philanthropic self-sustainability (subsidies) and patient care (physician notes) in three separate departments, and temporally issuing bills based upon respective philanthropic and business logics. By segregating the obligations of philanthropic and business self-sustainability within the structure of the data, it enables a management of the hospital in a way which ensures that both of these unique obligations are fulfilled. To analyse data in this study, our analytical strategies constantly negotiated between our tacit knowledge of the unique costs of experiences of Indian cancer patients and what the spatial and temporal structuring of the self-sustainable hospital’s data made possible.

In the first example of our team’s data analysis, the spatial segregation of data increased the capacity required for our team to aggregate and then translate the data to be comparable. However, in this case what was further limiting was making commensurable patients’ realities of moving between private and general payment categories with the imagination of Euro-North American health economics methodologies that holds the individuals within categories as homogenous. For patients that encapsulated this tension where their bills showed them existing in an in-between space of classification as a private or a general patient, our team called upon our tacit knowledge of the indirect costs of patients to inform their categorisation. This tacit knowledge allowed our team to make assumptions about patients’ likelihood to traverse space for a given period of time and therefore the amount of their indirect costs during their private and general admissions. Therefore, our tacit knowledge generated a health economics methodology that we saw as more epistemologically ethical.

Making assumptions did not overtly contravene health economics methodology, but opportunised the cracks and fault lines in the epistemological gaps of doing cancer health economics in India. Specifically, rather than categorising patients as private or general based upon the majority of their in-patient expenditure, our team employed a tacit epistemological ethics that attempted to reconcile patients’ stories of indirect expenditure with health economics methodologies’ demands to produce metrics which may otherwise obscure these stories. In this way, our work did not ‘victoriously’ avoid the realities of patients, but attempted to employ a tacit epistemological ethics that embedded these stories into its methodological construction. In the process of this data analysis, the surplus of patient realities were not merely relegated to a ‘spectral possibility’ but instead informed our method of analysis (Adams, Citation2016, p. 48). This provided a moment where our team negotiated the ‘transnational flow of … [health economics] knowledge’ by ‘improvising selected forms of’ categorisation in an effort to produce an ethical economic logic which more fully represented patients’ experiences of paying for care (Moran-Thomas, Citation2019, p. 483).

The above example of our team’s data analysis focused on ‘what counts as health’ in the process of data collection and analysis, and how boundaries become blurred, the second example of our team’s data analysis shows the limitations of this form of tacit epistemological ethics. The second case shows how the different data spaces of philanthropy and business articulate different temporal logics; respectively providing subsidy data for the whole course of treatment but not specifying when it was issued during the treatment pathway, and providing billing data for each patient admission. These different temporal logics of philanthropic and business data spaces limited our research team’s ability to calculate the costs to patients at specific stages of the treatment pathway. Despite attempting to provide more information about infection costs by disaggregating the cost of each IP bill by the type of service administered, we still could only calculate the costs to the hospital. Because philanthropic subsidies did not show when the subsidy was issued to the patient, it was not possible to calculate the costs to the patient. In this case, while our team again tried to employ a tacit epistemological ethics by disaggregating costs in the hope that it may make more legible patients’ stories of catastrophic health expenditure from infection costs, our efforts were limited by the different temporal logics of the data.

What is at stake in calculating the costs to patients during inpatient admissions with high infection costs that otherwise appear as curative is the possibility of identifying the para-communicable risk of cancer. Cancer infections occur for a range of reasons most notably including antimicrobial resistance, yet the most frequent and afflicted infectious victims are often at the lower end of the socio-economic gradient. Measuring infection costs is then important to identify socio-economic groups that may be more likely to incur infections and as such have higher costs of treatments. By providing this information, it can help stakeholders to target these groups for infection prevention and provide guidance to philanthropic subsidies on how and when subsidies can be used not only for care, but also for indirect costs that may be determinants in catastrophic expenditure while patients undergo treatment. However, without information on when subsidies have been given to patients our team’s data analysis could not contribute to these discussions because we could not conclude whether subsidies were given before, after, or during treatments that had significant costs, and therefore if subsidies had an effect on preventing further infections. Therefore, even when the capacity is allocated to make tacit epistemological ethics possible, it too can reach its analytical limits.

The potential for this form of tacit epistemological ethics also reaches its limits in the process of data dissemination. The possibility of including these otherwise ‘surplus’ patient realities was still fleeting, and often exists deep within the results of the larger study. This places limitations on our methodology when the results of these studies travel beyond the original research team and into wider institutional structures. If the capacity is allocated to produce these types of results it may be possible, however, it requires a similar analytical lens in the process of data dissemination to make these results relevant. When and how these results are used will likely be dependent on future funding and policy infrastructures, returning the realities of patients to eclectically funded health systems. Further, the methodology our team constructed is limited because it would be challenging to impossible to reproduce for similar calculations in other settings as well as within the same hospital for other cancer types and patient groups. Therefore, this form of tacit epistemological ethics disrupts the possibility of metrics’ reproducibility and poses challenges for data comparability in health policy planning.

Conclusion

This article has argued that this hospital’s obligations of philanthropic and business self-sustainability produced the conditions of possibility for what was able to be made knowable from patient data. Amidst the epistemological gap of cancer health economics in India, tacit knowledge is able to guide methodological constructions in ways that aim to more realistically incorporate the experiences of patients, and as such produce a more ethical epistemological logic. Therefore, in this case, patients’ stories were not a ‘spectral possibility’ but instructive instruments in producing an ethical methodology. Nonetheless, I conclude by cautioning that following the performance of data collection and analysis when forms of tacit epistemological ethics may be exercised, data is returned to larger structures of conditions of possibility within austere health systems and Euro-North American health economics frameworks.

This article suggests that a closer attunement is needed to the ethical strategies of knowledge production, specifically within health economics. For cancer health economists operating in similar contexts, explicit methodological admission of these strategies may also aid the discipline by working to incorporate more nuanced patient realities. For these methodological strategies to hold policy implications, it would be helpful to begin to more consistently and systematically calculate the indirect costs of cancer patients in India. Further, aligning the temporal logics of data sources would make more analytical work possible, specifically that which would help to calculate costs to patients. Working towards these goals would help to more accurately represent the experiences of cancer patients across these scales.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Vivek S. Radhakrishnan, Mohini Samani, Payal Mandal, and Arnab Ghosh, as well as the other supervisors involved in this study. I thank Aditya Bharadwaj, Carlo Caduff, and Martha Lincoln for help in the conceptualisation of this article and guidance on how to bring forth this argument in the most clear way. None of the individuals listed here are responsible for the arguments made in this article and all faults are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adams, V. (2016). Metrics. Duke University Press. https://www.dukeupress.edu/metrics/.

- Amrith, S. (2009). Health in India since independence. BWPI working paper 79. Brooks World Poverty Institute.

- Banerjee, D. (2019). Cancer and conjugality in contemporary Delhi: Mediating life between violence and care. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 33(4), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12541

- Baru, R. V. (1998). Private health care in India: Social characteristics and trends. Sage Publ.

- Bharadwaj, A. (2009). Assisted life: The neoliberal moral economy of embryonic stem cells in India. Berghahn Books.

- Caduff, C., Sharma, P., & Pramesh, C. (2019). On the use of surveys and interviews in social studies of cancer: Understanding incoherence. Ecancermedicalscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2019.918

- Ganapule, A., Nemani, S., Korula, A., Lakshmi, K. M., Abraham, A., Srivastava, A., Balasubramanian, P., George, B., & Mathews, V. (2017). Allogeneic stem cell transplant for acute myeloid leukemia: Evolution of an effective strategy in India. Journal of Global Oncology, 3(6), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2016.006650

- Herrick, C. (2017). The (non)charisma of noncommunicable diseases. Social Theory & Health, 15(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-016-0021-2

- Herrick, C. (2020). The optics of noncommunicable diseases: From lifestyle to environmental toxicity. Sociology of Health & Illness, 1041–1059, Article 13078. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13078

- Holmes, S. (2013). Fresh fruit, broken bodies: Migrant farmworkers in the United States. University of California Press.

- Jain, M., & Mukherjee, K. (2016). Economic burden of breast cancer to the households in Punjab, India. International Journal of Medicine and Public Health, 6(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8598.179754

- Jo, C. (2014). Cost-of-illness studies: Concepts, scopes, and methods. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology, 20(4), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2014.20.4.327

- Mallath, M. K., Taylor, D. G., Badwe, R. A., Rath, G. K., Shanta, V., Pramesh, C. S., Digumarti, R., Sebastian, P., Borthakur, B. B., Kalwar, A., Kapoor, S., Kumar, S., Gill, J. L., Kuriakose, M. A., Malhotra, H., Sharma, S. C., Shukla, S., Viswanath, L., Chacko, R. T., … Sullivan, R. (2014). The growing burden of cancer in India: Epidemiology and social context. The Lancet Oncology, 15(6), e205–e212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70115-9

- Mohanti, B. K., Mukhopadhyay, A., Das, S., Sharma, K., & Das, S. (2011). Estimating the economic burden of cancer at a tertiary public hospital: A study at the All Indian institute of medical sciences. Discussion papers in economics, Indian statistical institute, Delhi.

- Moran-Thomas, A. (2019). What is communicable? Unaccounted injuries and “catching” diabetes in an illegible epidemic. Cultural Anthropology, 34. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca34.4.01

- Palsetia, J. S. (2005). Merchant charity and public identity formation in colonial India: The case of jamsetjee jejeebhoy. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 40(3), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909605055071

- Pramesh, C. S., Badwe, R. A., Borthakur, B. B., Chandra, M., Raj, E. H., Kannan, T., Kalwar, A., Kapoor, S., Malhotra, H., Nayak, S., Rath, G. K., Sagar, T. G., Sebastian, P., Sarin, R., Shanta, V., Sharma, S. C., Shukla, S., Vijayakumar, M., Vijaykumar, D. K., … Sullivan, R. (2014). Delivery of affordable and equitable cancer care in India. The Lancet Oncology, 15(6), e223–e233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70117-2

- Prinja, S., Chauhan, A. S., Angell, B., Gupta, I., & Jan, S. (2015). A systematic review of the state of economic evaluation for health care in India. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 13(6), 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-015-0201-6

- Prior, L. (1988). The architecture of the hospital: A study of spatial organization and medical knowledge. The British Journal of Sociology, 39(1), 86–113. https://doi.org/10.2307/590995

- Ramireddy, J. K., Sundaram, D. S., & Chacko, R. K. (2017). Cost analysis of oral cancer treatment in a tertiary care referral center in India. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Biology, 2(1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.31557/apjcb.2017.2.1.17-21

- Rao, N. V., Downey, L., Jain, N., Baru, R., & Cluzeau, F. (2018). Priority-setting, the Indian way. Journal of Global Health, 8(2), Article 020311. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.020311

- Seeberg, J., & Meinert, L. (2015). Can epidemics be noncommunicable? Medicine Anthropology Theory, 2(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.2.2.171

- Sirohi, B., Chalkidou, K., Pramesh, C. S., Anderson, B. O., Loeher, P., El Dewachi, O., Shamieh, O., Shrikhande, S. V., Venkataramanan, R., Parham, G., Mwanahamuntu, M., Eden, T., Tsunoda, A., Purushotham, A., Stanway, S., Rath, G. K., & Sullivan, R. (2018). Developing institutions for cancer care in low-income and middle-income countries: From cancer units to comprehensive cancer centres. The Lancet Oncology, 19(8), e395–e406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30342-5

- Sivaramakrishnan, K. (2019). An irritable state: The contingent politics of science and suffering in anti-cancer campaigns in south India (1940–1960). BioSocieties, 14(4), 529–552. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-019-00162-8

- Smith, R. D. (2022). Emerging infrastructures: The politics of radium and the validation of radiotherapy in India’s first tertiary cancer hospital. BioSocieties. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-020-00223-3

- Smith, R. D., & Mallath, M. K. (2019). History of the Growing Burden of Cancer in India: From Antiquity to the 21st Century. Journal of Global Oncology, 5, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.19.00048

- Smith, R. D., Samani, M., Mandal, P., Ghosh, A., Roy, D., Bharti, N., Ghose, S., Datta, S., Chandy, M., & Radhakrishnan, V. (2019). Preliminary results of a cost analysis of acute myeloid leukemia treatment at tata medical center, Kolkata, India; 2011-2016. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, p. S221.

- Street, A. (2012). Affective infrastructure. Space and Culture, 15(1), 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331211426061

- Tichenor, M. (2017). Data performativity, performing health work: Malaria and labor in Senegal. Medical Anthropology, 36(5), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2017.1316722

- Tichenor, M. (2020). Metrics. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.29164/20metrics.

- Vevaina, L. (2018). Good deeds: Parsi trusts from ‘the womb to the tomb.’. Modern Asian Studies, 52(1), 238–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X17000336

- Wahlberg, A., & Rose, N. (2015). The governmentalization of living: Calculating global health. Economy and Society, 44(1), 60–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2014.983830