ABSTRACT

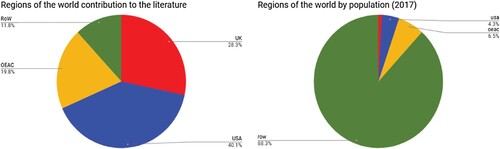

Despite many initiatives taken by funding bodies and health care organisations, the 10/90 gap in health care and health system research between low and middle-income countries (LIMC) and high income countries is still widely recognised. We aimed to quantify the contribution of LMIC in high impact medical journals and compare the results with the previous survey conducted in 2000. Research articles were anaylsed to determine the origin of data and authorship affiliated countries in a calendar year (2017) for five journals: British Medical Journal, The Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Annals of Internal Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association. Contributing countries were categorised into four regions; USA, UK, Other Euro-American countries (OEAC) and rest of the world (RoW). A total of 6491 articles were categorised where USA, UK and OEAC contributed 39.7%, 28.5% and 19.9% respectively. RoW countries contributed 11.9% of articles surveyed. The Lancet and NJEM had the highest numbers from RoW with 22.1% and 17.3% respectively. After 17 years, the trend remained comparable with the original survey carried out in 2000. RoW contributions increased from 6.5% to only 11.9% of the published articles from countries accounting for 88.3% of the world's population.

Introduction

Global health is ‘a field of study, research and practice that places a priority on achieving equity in health for all people’ (Koplan et al., Citation2009). There should be ‘collaborative transnational research and action for promoting health for all’ (Beaglehole & Bonita, Citation2010). The majority of the world's population resides in Low and Middle-Income countries (LMIC). Although research initiatives from LMIC have increased (Report of a High Level Task Force. Geneva: World Health Organization, Citation2009), discrepancies in the quality of healthcare available to individuals in different countries and within the same country persist (Luchetti, Citation2014). Research is a crucial requirement for improving health care services for populations in need (Reprt from the Ministerial Summit on Health Research: World Health Orgonisation, Citation2004). Mainly due to a lack of economic viability and research capability has specific historical and political reasons for inequalities persisted, hence LMIC nations are under-represented in research (Røttingen et al., Citation2012).

The field of global health is concerned with the health of populations worldwide, focusing on issues that typically have global, political and economic significance. These health issues usually transcend national boundaries and are best solved through international collaboration (Brown et al., Citation2006). This highlights the importance of the dissemination of research in such a way that it reaches every population in the world who could potentially benefit from it. Articles such as the current one aim to highlight which parts of the world are research active and publish the most research. This is a follow-up study to allow for direct comparison to previous work. There was an extensive research gap between High-Income Countries (HIC) and the rest of the world (RoW), as evidenced by prior research and this study. Therefore the implication is that the RoW relies on the research studies of HIC.

COVID-19 has exposed the gap in knowledge needed to face a global pandemic. HIC which had enhanced research capacity managed to develop vaccines within 2 years of the recent COVID pandemic.

‘The SARS-CoV-2 vaccines’ social promise was to lessen the underlying racial, ethnic and geographic inequities that COVID-19 has both made apparent and intensified. However, vaccine nationalism was evident throughout the COVID-19 crisis. Many HIC directly negotiated large advance orders for the vaccines, leaving resource-limited countries scrambling for access. This occurred despite international initiatives to structure the development and equitable distribution of vaccines, channelled through a vaccine pillar: COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX). The serious supply shortages and national procurement methods of some countries that bypassed the vaccine pillar hindered the optimal function of COVAX in delivering timely and adequate doses to participating countries (Md Khairi et al., Citation2022).

High-income countries representing just 13% of the global population have reserved 51% of the doses from several top candidates (Small Group of Rich Nations Have Bought up More than Half the Future Supply of Leading COVID-Citation19 Vaccine Contenders | Oxfam International, n.d.). Therefore, COVID-19 has reiterated the need for a stronger research capacity globally and warns governments in LMICs to increase research potential.

In this backdrop we have repeated the survey carried out in 2004 (Sumathipala et al., Citation2004).

We aimed to quantify the contribution of LMIC in high impact medical journals published in the calendar year 2017 and compare the results with the previous survey published in 2004.

Medical research or biomedical research, which is also known as experimental medicine, encompasses a wide array of research, extending from ‘basic research’ (also called bench science or bench research) (Basic Science | AAMC, Citationn.d.), to clinical research, which involves quantitative and qualitative studies including clinical trials. Within this spectrum is applied research, or translational research, conducted to expand knowledge in the field of medicine.

Aim and objective

We aimed to quantify the contribution of LMIC in five high impact medical journals; to determine the origin of data and authorship affiliated countries in a calendar year (2017) and compare the results with the previous survey published in 2004.

Materials and methods

The five journals surveyed were: British Medical Journal (BMJ), The Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM) and the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). These were the same journals included in the previous survey carried out in 2000. These Journals were selected based on having consistently high impact factors in the general medical field. The methodology used in the current study is the same as that used in the previous survey; by Sumathipala et al. (Citation2004).

The survey was carried out in 2019. A complete list of articles published in these journals during 2017 was accessed from the website of each journal.

For each article, the country of each author’s institutional affiliation as well as where the data was originating was noted. For original research articles, the method section and supplementary material were scrutinised to identify the country or countries in which the data was collected. Articles such as systematic reviews and editorials were categorised based on the institutional affiliations of their authors. In the rare event that an author had institutional affiliations in more than one country, a discussion between the investigators decided which country was recorded but no effort was made to identify the author's nationality.

This information was used to categorise articles into one of four regions of the world; United Kingdom (UK), United States of America (USA), Other Euro-American Countries (OEAC) or RoW (Rest of World). OEAC included Australia, New Zealand, Canada and European countries but excluding the UK and eastern European countries. RoW comprised of all other countries in the world including eastern European countries (Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungary, Poland, Republic of Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Slovakia, Russian Federation, Serbia and Ukraine).

Articles with any RoW authors were categorised as RoW. Original research articles were categorised as RoW if any of the data was collected in a RoW country, irrespective of whether any RoW authors were listed. Similarly, original research was categorised as OEAC if any of the data was collected in an OEAC and no RoW data was used. Where an original article had used data from more than one country, it was recorded as multinational. If a multinational investigation used data from a RoW country, it was also categorised as RoW. This process ensured allocating due credit to any contribution from LMIC to the publication.

The method of categorisation allocate publications with data or authors from LMIC to RoW, helped to minimise the bias of allocating publications to USA and UK or OEAC. For collaborative articles between the UK, USA and OEAC, categorisation was done based on the country in which the first author was affiliated.

Some categories of the article were excluded to keep the focus on research. This exclusion was done to keep in line with the previous survey protocol. The categories that were excluded from each journal were: From BMJ, ‘Obituaries’, ‘Multimedia’, ‘Personal views’, ‘Minerva’, ‘Soundings”, ‘News and filler’. From the Lancet, ‘Dissecting room’, ‘News’, ‘Department of error’, ‘Obituary’ and ‘Perspectives’ were excluded. From NEJM, ‘Book reviews’, ‘This week in the journal’ and ‘Abstracts’ were excluded. From AIM, ‘On being a doctor’, ‘Web exclusives’, ‘Current clinical issues’, ‘Medial writing’, ‘Book Notes’, ‘Summary for patients’ and ‘On being a patient’ were excluded. From JAMA, ‘A piece of mind’, ‘News from the food and drug administration’, ‘Poetry and medicine’, ‘The arts and medicine’, ‘Jama revisited’, ‘Masthead’, ‘News from the centre of disease control’, ‘Medical news’, ‘Perspective’ and ‘Highlights’ were also excluded.

Certain categories of articles from some of the journals were grouped due to the resemblance in content. For example, in the BMJ, editorials and editor’s choice were grouped as editorials. In the Lancet, editorials and comment were grouped as editorials. Also in the Lancet, reviews, series and seminars were grouped as reviews and articles and global health metrics were both considered original research. In JAMA, editorials, viewpoint and JAMA insight were grouped as editorials and research letters were grouped with comment and response as correspondence. Also, in JAMA, review and JAMA review were grouped as reviews.

Results

A total of 6491 articles were categorised into one of four regions of the world (). Articles in the USA category made up 39.7% of all articles, with the UK contributing 28.5% and OEAC at 19.9%. RoW articles accounted for 11.9% of publications across the five journals. However, this figure hides the level of inter-journal variation. RoW articles accounted for 5.7%, 6.1% and 6.3% of publications in AIM, JAMA and BMJ, respectively. The Lancet and NJEM published considerably more RoW articles as a proportion of their total publications at 22.1% and 17.3%, respectively. Regional variations were noted between journals. Most articles published in the British journals were from the UK and most published in the American journals were from the USA.

Table 1. Breakdown of contribution of different regions of the world to the medical literature.

Overall, there were 727 original research articles. 240 (33.0%) of these were from the RoW. The Lancet published the highest percentage of RoW original research articles. Of the 173 original papers published in the Lancet, 92 (53.2%) were RoW. AIM published the lowest percentage of RoW original research where out of 72 papers, only five (6.9%) were from RoW. Across all five journals, 189 (78.8%) original research articles from the RoW had at least one author from the RoW. Of these, 55 (29.1%) publications had a first author; 56 (29.6%) had the last author; 50 (26.5%) had their corresponding author from the RoW countries. 39 (20.6%) publications had all three first, last and corresponding authors from the RoW illustrating that even when data was from the RoW, this was often not reflected in authorship.

Out of the 240 RoW original articles, 179 (74.6%) were classed as ‘multinational’ because they included data from more than one country, including at least one RoW country. The remaining 61 articles had data from just one of the 22 RoW countries ().

Table 2. Original research articles from different regions of the world and subregions of the RoW.

Thirty-seven original research articles had data collected in the RoW but had no authors from RoW countries. Sumathipala labelled such research as ‘safari research’ in their original survey (Sumathipala et al., Citation2004). Of these 37 articles, 20 were published in NJEM, 11 in The Lancet, 4 in the BMJ and 2 in JAMA. These papers made up 21.5%, 12%, 22.2% and 6.3% of the RoW original papers published in these journals, respectively. All of these papers were classed as multinational as the data was not collected in just one country.

As shown in , there was a rise in the number of publications from RoW countries in the surveyed journals after 17 years. All the journals published a proportionally higher number of research articles in the current survey when compared against the previous survey conducted in 2000. The highest rise was observed in NEJM from 6% to 17.3% in publications coming from RoW.

Table 3. Comparison of current and previous literature from RoW.

However, an important finding is that even after 17 years, the overall trend remained similar and that only 11.9% of published studies in these peer-reviewed journals came from authors in countries with 88.3% of the world's population ().

Discussion

This paper highlights the findings from a survey of articles published during 2017, a full calendar year, in five high impact general medical journals. The aim was to describe the research contribution by the RoW. The findings reveals that the percentage of published literature of RoW has only increased from 6.5% to 11.9% during 2000–2017.

According to recent studies, LMIC remains underrepresented (Servadei et al., Citation2019).

To some extent, the causes for under-representation of research literature from the RoW countries remain the same as explained in the previous review (Sumathipala et al., Citation2004). The research outputs from medical institutions based on data collected from the year 2012–2017 in South Asian countries highlighted the low quality of publication as well lower quantity of publications (Ray et al., Citation2019). This is due to the numerous obstacles present in LMIC to conduct high-quality research including a lack of research environment, financial and human capability, ethical and regulatory system constraints, operational barriers, and conflicting demands (Alemayehu et al., Citation2018).

Challenges and barriers to conducting research in LMIC

There are many reasons, for why LMIC research gets published less frequently than HIC research. One is the capacity; strong writing and critical thinking skills are needed to design and publish high-quality research (and most influential journals are in English which puts non-native English speakers at further disadvantage). Capacity building efforts for research in LMIC tends to neglect the significance of these skills which are not formally taught in many LMICs at any level of education (Macpherson, Citation2019). If researchers have such limitations (as many do even in wealthy countries) then the research doesn’t get conducted, or doesn’t get conducted in a way that contributes useful information and/or doesn’t get published.

In line with some recent research findings, the lack of information resources remains one of the main barriers to research activities followed by the publication of research (Dadipoor et al., Citation2019; Ibrahim Abushouk et al., Citation2016; Safajou et al., Citation2017).

Access to journals could be useful for RoW authors in selecting a suitable journal in which to publish their work. Currently, open access (OA) journals are a useful platform to do so. However, even with the increase in OA literature (Iyandemye & Thomas, Citation2019), half of the publications under this category are not legally accessible to be read by all in the LMIC without an institutional license or publishers’ fees (Piwowar et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, steps taken by Journals interested in Global international Health, which waives article publication charges from authors in low-income countries, is a supportive step to welcome research from such countries. This can be further encouraged by adding a condition to funding recipients on the dissemination of research in some form at least in low-income countries. Creation of a virtuous cycle including dissemination of research with the RoW world followed by the policies and plans based on empirical research and if executed appropriately could be useful in improving global health and eventually useful in reducing the 10/90 gap.

Some of the crucial global health research challenges are linked to current approaches to research funding. The role of funders and donors in achieving greater equity in global health research needs to be clearly defined. Imbalances of power and resources between HIC and LMIC is such that many funding approaches do not centre the role of LMIC researchers in shaping global health research priorities and agenda. Relative to need, there is also disparity in financial investment by LMIC governments in health research (Charaniid et al., Citation2022).

Research ethics dilemmas

There were 40 original research publications for which no information could be found about the country or countries of origin of the data. These articles were excluded from the analysis. Most of these articles were large multicentre and multicounty trials lead by a team based in the USA. Overall, this was more prolific in the US journals (NEJM, Annals of internal medicine, JAMA) with the majority of these articles being published in the NEJM. Editors should consider mandatory inclusion for the country of origin’s data. No firm conclusions could be made about these but one may speculate as to whether these studies, particularly Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), were done without proper ethical approval from the countries where these studies were carried out. Data could well be from LMICs where people are vulnerable. On the other hand, there could be the issue of therapeutic misconception; when a research subject fails to appreciate the distinction between the imperatives of clinical research and of ordinary treatment, and therefore inaccurately attributes therapeutic intent to research procedures (Henderson et al., Citation2007).

A further ethical issue is evident in this study, 37 original investigations published data from a RoW country but had no authors from a RoW country. This is clearly an ethical issue that should be revisited by journal editors (Abimbola & Pai, Citation2020). Data ownership and ethical data sharing are crucial in international collaborative research (Bull & Bhagwandin, Citation2020).

China’s medical literature output has increased from 2000 due to increased support for research by the government of China (Xie & Freeman, Citation2019). Oppositely, the proportion of contribution by Sub-Saharan countries has remained low over the last 20 years as studied by Kebede (Ray et al., Citation2019). Such countries, although active in medical research, may have different objectives for dissemination where peer-reviewed publications are minimal compared to books, conferences or broadcasts. Finally, this study showed a massive increase in multi-national studies which is well documented (Weigmann, Citation2015). This may represent exploitation of LMIC who participate as a way of accessing medical treatments (Sumathipala & Siribaddana, Citation2004).

The global benefits of research in LMIC

The benefits of research in LMIC have been recognised for nearly three decades, first by the 1990 Commission on Health Research for Development. It was strongly recommended that enhancements in research from LMIC could lead to advancements in health globally, hence, research and its dissemination in high impact journals is crucial. Such recognitions help increase research collaborations and partnerships that address the health needs of LMICs (Maleka et al., Citation2019).

There is evidence that the limited research carried out in the Global South has had significant impact on the global North. Eclampsia, clinical trial (1687 patients) conducted in South America, Africa and India (De Jesus Mari et al., Citation1997) is one classic example, how collaborations provide answers to developing and developed countries. Another classic example is the research carried out by Patel V et al. (Citation2006); why do women complain of vaginal discharge? (Patel et al., Citation2006). Prior to this study, the World Health Organization had recommended syndromic management, in which women complaining of vaginal discharge are treated for some or all of the five common reproductive tract infections (RTIs) (Mabey & Vos, Citation1997). That approach had a significant social costs through divorce due to mistrust among partners. The third example is the RCT on ‘CBT by community health workers for maternal depression and child development in Pakistan (Rahman et al., Citation2008).

The way forwards

Cross-national or intercountry collaborations can further be useful in tackling some of the barriers (Ray et al., Citation2019; Servadei et al., Citation2019). However, these platforms or partnership events would need to be accessible by LMIC participants to give them the opportunities to find out more. Furthermore, custom-made funding opportunities followed by incentives on publishing research could also be useful in the addition of more research literature from the LMIC.

The process of peer reviewing is very important in ensuring reliability and maintenance of standards in the medical field where the research interventions/findings are used in health improvements. However, peer review can sometimes cause delay and occasionally when the process is too lengthy between submissions and receiving feedback it can put someone off from resubmitting too. The peer-review process is also affected due to the differences in cultures and perceptions among different regions of the world (Epstein, Citation2007). The peer-review process should be followed by keeping these differences among LMICs and HICs in mind and inviting reviewers from diverse regions. Structures to follow ethical research in LMICs are sometimes under question for safety and ethical safeguarding to any harm to the patients. Such perceptions lead to strict guidelines for countries and eventually lead to hindrance of good quality research or its publication (Chetwood et al., Citation2015). The global South cannot do it by themselves and the moral obligation of North–South partnerships and collaboration in to ensure mutually respectful and beneficial partnership for new knowledge generation and dissemination.

Limitations

The authors understand that the classification of the world into different regions (UK, USA, OEAC and RoW) could have been done in different ways. However, the classification was replicated from the previous similar study to maintain consistency and allow observation of trends. This survey did not include perspectives as medical research. However there is a different school of thoughts especially in bioethics, developing an argument or providing recommendations are often considered to be ‘research’ even though these may not collect empirical data. Both the Lancet and BMJ for instance have established in recent years their global health counterparts. The Lancet Global Health was started in 2013. Therefore, some research conducted in the RoW may have been published in The Lancet Global Health.

However BMJ Global Health started only in 2016 may not have affected this results significantly.

Conclusions

Although publication from RoW in these five journals increased from 6.5% to 11.9% it cannot be considered a significant increase considering it has happened over 17 years. The current publication highlights the significant gap of research in medical journals from LMICs. Research conducted in LMICs needs disseminating globally and collaborations among HICs and LMICs are crucial especially to overcome situations like a pandemic. Finally, as suggested by Luchetti (Citation2014) it is vital to determine where to invest in research and without any preconceptions while finding a possible way to address global health issues beyond the market-based economic paradigm (Abimbola & Pai, Citation2020). Similarly HIC researchers should fulfil ethical obligations by deciding what makes research ethical (Emanuel et al., Citation2004). The requirements for ethical research include: social value, scientific validity, fair selection of participants, favourable risk/benefit ratio, independent review, adequate informed consent, ongoing respect for dignity, publish the findings and community participation. Therefore, HIC researchers should be exploring the ethics of global health research priority-setting (Pratt et al., Citation2018).

If the future of global health is more of the same with some cosmetic changes to disguise supremacy, it would have failed. But if the future is a radical transformation, then global health would be unrecognisable. We may even have to give it a new name. The goal of global health should not be to survive its decolonisation, but to rise up and live up to the pressing demands of its mission (Abimbola & Pai, Citation2020; Zarowsky, Citation2011). To collectively shape a new approach to global health research funding, it is essential that funders and donors are part of the conversation. This article provides a way to bring funders and donors into the conversation on equity in global health research (Charaniid et al., Citation2022).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abimbola, S., & Pai, M. (2020). Will global health survive its decolonisation? Lancet, 396(10263), 1627–1628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32417-X

- Alemayehu, C., Mitchell, G., & Nikles, J. (2018). Barriers for conducting clinical trials in developing countries – A systematic review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0748-6

- Basic Science | AAMC. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-research/basic-science.

- Beaglehole, R., & Bonita, R. (2010). What is global health? Global Health Action, 3(1), 5142. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

- Brown, T. M., Cueto, M., & Fee, E. (2006). The world health organization and the transition from “international” to “global” public health. American Journal of Public Health, 96(1), 62–72. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831

- Bull, S., & Bhagwandin, N. (2020). The ethics of data sharing and biobanking in health research. Wellcome Open Research, 5, 270. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16351.1

- Charaniid, E., Abimbolaid, S., Paiid, M., Adeyi, O., Mendelsonid, M., Laxminarayan, R., & Rasheedid, M. A. (2022). Funders: The missing link in equitable global health research? PLOS Global Public Health, 2(6), e0000583. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PGPH.0000583

- Chetwood, J. D., Ladep, N. G., & Taylor-Robinson, S. D. (2015). Research partnerships between high and low-income countries: Are international partnerships always a good thing? BMC Medical Ethics, 16(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0030-z

- Dadipoor, S., Ramezankhani, A., Aghamolaei, T., & Safari-Moradabadi, A. (2019). Barriers to research activities as perceived by medical university students: A cross-sectional study. Avicenna Journal of Medicine, 9(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/AJM.AJM_121_18

- De Jesus Mari, J., Lozano, J. M., & Duley, L. (1997). Erasing the global divide in health research. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 314(7078), 390. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.314.7078.390

- Emanuel, E. J., Wendler, D., Killen, J., & Grady, C. (2004). What makes clinical research in developing countries ethical? The benchmarks of ethical research. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189(5), 930–937. https://doi.org/10.1086/381709

- Epstein, M. (2007). Clinical trials in the developing world. The Lancet, 369(9576), 1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60846-0

- Henderson, G. E., Churchill, L. R., Davis, A. M., Easter, M. M., Grady, C., Joffe, S., Kass, N., King, N. M. P., Lidz, C. W., Miller, F. G., Nelson, D. K., Peppercorn, J., Rothschild, B. B., Sankar, P., Wilfond, B. S., & Zimmer, C. R. (2007). Clinical trials and medical care: Defining the therapeutic misconception. PLOS Medicine, 4(11), e324. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324

- Ibrahim Abushouk, A., Nazmy Hatata, A., Mahmoud Omran, I., Mahmoud Youniss, M., Fayez Elmansy, K., & Gad Meawad, A. (2016). Attitudes and perceived barriers among medical students towards clinical research: A cross-sectional study in an Egyptian medical school. Journal of Biomedical Education, 2016, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5490575

- Iyandemye, J., & Thomas, M. P. (2019). Low income countries have the highest percentages of open access publication: A systematic computational analysis of the biomedical literature. PloS One, 14(7), e0220229. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0220229

- Koplan, J. P., Bond, T. C., Merson, M. H., Reddy, K. S., Rodriguez, M. H., Sewankambo, N. K., & Wasserheit, J. N. (2009). Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet (London, England), 373(9679), 1993–1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

- Luchetti, M. (2014). Global Health and the 10/90 gap. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 7(4), 731. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

- Mabey, D., & Vos, T. (1997). Syndromic approaches to disease management. Lancet, 349(SUPPL.3), S26–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)90085-4

- Macpherson, C. C. (2019). Research ethics guidelines and moral obligations to developing countries: Capacity-building and benefits. Bioethics, 33(3), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12577

- Maleka, E. N., Currie, P., & Schneider, H. (2019). Research collaboration on community health worker programmes in low-income countries: An analysis of authorship teams and networks. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1606570. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1606570

- Md Khairi, L. N. H., Fahrni, M. L., & Lazzarino, A. I. (2022). The race for global equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines, 10(8), 1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081306

- Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Kirkwood, B. R., Pednekar, S., Nevrekar, P., Gupte, S., & Mabey, D. (2006). Common genital complaints in women: The contribution of psychosocial and infectious factors in a population-based cohort study in Goa, India. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(6), 1478–1485. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl219

- Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J. P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., & Haustein, S. (2018). The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of open access articles. PeerJ, 6(2), e4375. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4375

- Pratt, B., Sheehan, M., Barsdorf, N., & Hyder, A. A. (2018). Exploring the ethics of global health research priority-setting. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0333-y

- Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 372(9642), 902–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

- Ray, S., Al Mamun Choudhury, A., Biswas, S., Bhutta, Z. A., & Nundy, S. (2019). The research output from medical institutions in South Asia between 2012 and 2017: An analysis of their quantity and quality. Current Medicine Research and Practice, 9(4), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmrp.2019.07.005

- Report of a High Level Task Force. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2009). Scaling up research and learning for health systems: Now is the time. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/alliancehpsr_task_force_report_research.pdf.

- Røttingen, J. A., Chamas, C., Goyal, L. C., Harb, H., Lagradae, L., & Mayosi, B. M. (2012). Securing the public good of health research and development for developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(5), 398–400. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.105460

- Safajou, F., Soltani, N., & Amouzeshi, Z. (2017). Barriers to breast cancer screening in nursing and midwifery personnel of hospitals of Birjand, Iran. Modern Care Journal, 14(1), 11720. https://doi.org/10.5812/modernc.11720

- Servadei, F., Tropeano, M. P., Spaggiari, R., Cannizzaro, D., Al Fauzi, A., Bajamal, A. H., Khan, T., Kolias, A. G., & Hutchinson, P. J. (2019). Footprint of reports from Low- and Low- to middle-income countries in the neurosurgical data: A study from 2015 to 2017. World Neurosurgery, 130(1), e822–e830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.230

- Small group of rich nations have bought up more than half the future supply of leading COVID-19 vaccine contenders | Oxfam International. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/small-group-rich-nations-have-bought-more-half-future-supply-leading-covid-19.

- Sumathipala, A., & Siribaddana, S. (2004). Revisiting “freely given informed consent” in relation to the developing world: Role of an ombudsman. The American Journal of Bioethics : AJOB, 4(3), W1–W7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265160490505498

- Sumathipala, A., Siribaddana, S., & Patel, V. (2004). Under-representation of developing countries in the research literature: Ethical issues arising from a survey of five leading medical journals. BMC Medical Ethics, 5(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-5-5

- Weigmann, K. (2015). The ethics of global clinical trials. EMBO Reports, 16(5), 566–570. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201540398

- Xie, Q., & Freeman, R. B. (2019). Bigger than you thought: China’s contribution to scientific publications and Its impact on the global economy. China & World Economy, 27(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12265

- Zarowsky, C. (2011). Global health research, partnership, and equity: No more business-as-usual. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(SUPPL. 2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-11-S2-S1/METRICS