ABSTRACT

This study aimed to explore the firsthand experiences of informal primary caregivers of women with female genital fistula in Uganda. Caregivers that accompanied women for surgery at Mulago National Teaching and Referral Hospital were recruited between January and September 2015. Caregivers participated in in-depth interviews and focus groups. Data were analysed thematically and informed adaptation of a conceptual framework. Of 43 caregivers, 84% were female, 95% family members, and most married and formally employed. Caregivers engaged in myriad personal care and household responsibilities, and described being on call for an average of 22.5 h per day. Four overlapping themes emerged highlighting social, economic, emotional, and physical experiences/consequences. The caregiving experience was informed by specific caregiver circumstances (e.g. personal characteristics, care needs of their patient) and dynamic stressors/supports within the caregiver’s social context. These results demonstrate that caregivers’ lived social, economic, emotional, and physical experiences and consequences are influenced by both social factors and individual characteristics of both the caregiver and their patient. This study may inform programmes and policies that increase caregiving supports while mitigating caregiving stressors to enhance the caregiving experience, and ultimately ensure its feasibility, particularly in settings with constrained resources.

Introduction

Female genital fistula, an abnormal opening between the urinary and genital tracts, is commonly due to prolonged obstructed labour, iatrogenic, or traumatic etiologies in lower-resource settings and primarily presents with incontinence (UNFPA, Citation2021; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2020). While incidence and prevalence measures vary considerably, global estimates suggest a minimum of 500,000 women are living with fistula worldwide, with 50,000–100,000 new cases annually, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Adler et al., Citation2013; de Bernis, Citation2007; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2020). According to population-based estimates in Uganda, our study location, 1.4% of women (0.5%−4.3% regionally) report experiencing genital fistula symptoms (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Kampala, Citation2018).

While most fistulae can be surgically repaired, only ∼60% of women seek treatment and ∼30% receive surgery in Sub-Saharan Africa, while others face barriers related to lack of knowledge, poverty, and stigma (Gebremedhin & Asefa, Citation2019; Keya et al., Citation2018; Ruder et al., Citation2018; United Nations General Assembly, Citation2020). In Uganda, these barriers are compounded by challenges to health care access, reported by urban (40%) and rural residents (60%) (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Kampala, Citation2018). Women living with fistula experience physical consequences including urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic and urinary infections, ulcerations, inflammation, nerve damage, and infertility (UNFPA, Citation2016; Wall, Citation2006). Social and economic consequences such as stigma and reduced opportunities for community participation and income generation further diminish wellbeing (Keya et al., Citation2018). Many women with fistula rely on informal caregivers for additional support managing these complex consequences.

Informal caregivers are usually unpaid individuals who assist friends or family members experiencing health circumstances that prevent them from fully caring for themselves (Mitchell & Knowlton, Citation2009). Caregiving is a common, culturally-rooted practice throughout sub-Saharan Africa, and remains important in both community and facility settings (Adedeji et al., Citation2022). In the community, women with fistula may require support with personal hygiene and daily household tasks dependent on condition and symptom severity (Jarvis et al., Citation2017). In fistula repair settings, staffing and funding challenges result in companions regularly accompanying patients to provide basic nursing care (Sadigh et al., Citation2016). In both settings, informal caregivers, most of whom are women, are necessary extensions of formal health care workers, (Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015) providing approximately half of patient care needs (Gertrude et al., Citation2019; Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015). Female caregivers frequently care for their patient across both settings (Lafferty et al., Citation2022).

Informal caregivers are essential to supporting women with fistula, particularly where the health workforce is overburdened. With only 168 doctors and 1,470 nurses or midwives per 1,000,000 people in Uganda, informal caregivers play a key role in mitigating the impact of this severe health worker shortage on fistula management (World Bank Group, Citation2016). Like other stigmatised conditions, fistula caregiving often occurs among strained relationships due to the particular complexities and challenges of fistula care (Jarvis et al., Citation2017). Understanding the support caregivers need to effectively care for women with fistula could improve the experience for both caregiver and recipient.

Prior studies have primarily examined patients’ experiences, with few centreing support persons or informal caregivers for managing female genital fistula (Tatangelo et al., Citation2018). However, the limited relevant literature documents a substantial burden associated with caring for this patient population (Jarvis et al., Citation2017). Informal caregivers of women with fistula describe secondary stigma related to their close association with a devalued condition and face other physical, emotional, social, and economic consequences including depression, sleep deficit, missed social engagement, and lost wages (Gertrude et al., Citation2019; Jarvis et al., Citation2017; Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015). Assessing the unique needs, perspectives, and experiences of caregivers is crucial to develop health- and wellness-promoting strategies for both caregiver and recipient. The objective of this study was to explore the firsthand experiences of informal caregivers of women with female genital fistula accompanying patients for care at Mulago National Teaching and Referral Hospital in Kampala, Uganda.

Methods

Study site

Mulago Hospital is Uganda’s largest hospital, with ∼30,000 births and ∼100 fistula surgeries annually (Sadigh, 2016). Mulago provides patients with a bed and basic meals, but patients provide bedding and laundry services (Sadigh, 2016). Informal caregivers commonly compensate for the under-resourced hospital, and those caring for women accessing fistula repair provide facility-based support for approximately two weeks (14 days) in addition to community-based care. Tangible provisions by caregivers vary related to their own capacity and resources as well as the availability of facility resources at any given time.

Theoretical orientation

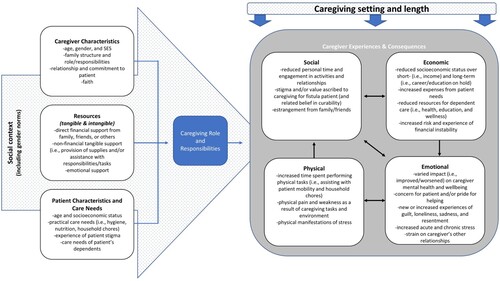

This study was informed by Conde-Sala et al.’s Stress Process Model which depicts caregiver symptoms (i.e. physical and emotional health) as influenced by contextual stressors (e.g. caregiver-care recipient relationship and relationship history, gender, and time), patient condition severity (e.g. behavioural, functional, and cognitive deficits, and time since onset), and secondary stressors external to the caregiver-recipient relationship (e.g. other family factors, employment, and financial stressors), buffered by multi-level social support (e.g. individual, household, community and institutional) and medical care (Conde-Sala et al., Citation2010; Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015). This approach acknowledges the broad and multi-dimensional nature of factors influencing each caregiver’s experience. During analysis, our team further adapted this model to the unique realities of caregiving for female genital fistula ().

Data collection

Primary caregivers of women with fistula were recruited from the urogynecology ward at Mulago Hospital between January-September 2015. Individuals who had accompanied a patient undergoing fistula surgery who identified as a primary caregiver within the community setting were approached by a trained qualitative researcher during their patient’s hospital stay and invited to participate in an in-depth interview or a focus group discussion based on convenience for the participant and study team.

We employed a qualitative approach combining in-depth interviews (n = 21) and focus groups (5 groups, n = 22) with a sociodemographic and caregiving characteristics questionnaire. Qualitative data collection employed semi-structured guides to understand how participants became caregivers, critical caregiving tasks, influence of caregiving role on their personal and social lives, challenges of caregiving, and overall perspectives on the caregiving experience. The sociodemographic and caregiving characteristics questionnaire included questions about household assets, marital status, employment, educational attainment, relationship to care recipient, and amount and type of care provided. After informed consent, the questionnaire was administered to study participants followed by an in-depth interview or focus group. We have no missing data to report from the questionnaire. Interviews and focus groups were conducted either in English or in Luganda (local language) by an experienced Ugandan qualitative interviewer (HN) assisted by a fistula care nurse; all were audio-recorded with participant permission and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Luganda audio recordings were concurrently translated and transcribed into English by transcribers who were proficient in both languages.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively. Qualitative data were analysed thematically, prioritising the identification, analysis, and interpretation of meaningful patterns (Emerson et al., Citation2011). Transcripts were coded by the Ugandan qualitative interviewer (HN) and an American mixed-methods researcher (AE). Codebook development followed deductive and inductive approaches, building on theory-informed guides with topics arising from within our data. Theoretical memos summarising analytic themes were written capturing the primary findings of the iterative coding and analysis process. Coded qualitative data, memos, and quantitative sociodemographic questionnaire data were analysed by the Ugandan qualitative interviewer (HN), the American mixed-methods researcher (AE), and an American graduate student researcher (AM). Interpretation of findings was reviewed iteratively by the full binational research team. Analysis employed Atlas.ti and Stata 17.0 softwares.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (Ref# 2014-052) and the University of California, San Francisco Human Research Protection Program, Committee on Human Research (IRB# 12-09573) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (REF#:1541212101). All individuals eligible for the research underwent an informed consent process; those individuals unable to provide signature for informed consent provided thumbprint confirmation.

Results

Conceptual model development

Findings informed the adaptation of a conceptual model depicting the intersecting factors shaping caregiving roles/responsibilities, experiences, and consequences (). Thematic findings across caregivers showed the influence of the caregiver’s social context and caregiving circumstances, and the multifaceted experiences and consequences of caregiving across social, emotional, physical and economic domains. Gender norms were found to be particularly influential. ‘Caregiving Role and Responsibilities’ is centred in the model, determined by sociodemographic factors, resources, and patient sociodemographic factors and unique needs. Caregiver experiences and consequences are simultaneously influenced by the caregiving setting and length. The model also depicts unidirectional and bidirectional relationships within the four experience/consequence domains.

Caregiver characteristics and resources

Our sample included 43 caregivers aged 15–55 years old. Most were female (84%) and family members (95%) of the woman they were supporting (). Female caregivers primarily reported caring for their sisters (n = 10), sisters- or daughters-in-law (n = 9), mothers (n = 7), and daughters (n = 5). Male caregivers provided care for their wives (n = 6) or mothers (n = 1). More than half were married and/or living with a partner (51%) and formally employed (65%). Most caregivers had completed some or all primary school, and the majority reported being Catholic or Protestant. Participant assets included a mobile phone (72%), radio (67%), and electricity (42%); fewer reported household amenities such as piped water (12%), refrigerator (9%), and flush toilet (7%). Meaningful patterns related to sociodemographic characteristics and caregiving practices outside of gender, economic status, and caregiving length were not prominent among caregivers in this study population.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics and caregiving practices among lay caregivers for women undergoing fistula surgery, Uganda (N = 43).

Participants’ reasons or motivations for caregiving varied. Some women reported experiencing fistula themselves in the past and saw caregiving as a way to return the kindness they had received. Other caregivers suggested that they had supported their patient through pregnancy and felt responsible to continue after a fistula occurred, or were selected by the family or community because of their general temperament; one caregiver described, ‘It is because of all the people in our family, I for one, I am down to earth … ’ (Sister, age 42). Caregiving husbands were the most likely to report taking on the role as a last resort or because other viable options were too far away. One husband explained ‘I started caretaking for her because I failed to get a caretaker’ (Husband, age 33). There were no significant differences in caregiving length; however, no male caregivers reported caregiving for three or more years whereas six female caregivers did. This may suggest that caregivers who entered the role more intentionally were more likely to stay in it for a long period of time.

PatientFootnote1 characteristics and care, and needs caregiving setting and length

Most participants (70%) reported having provided care for less than 3 months although 14% had provided care for 3 years or more. Caregivers who reported not working outside of the home were slightly more likely to have provided care for 3 months or more (n = 6) compared to those working (n = 7). In the questionnaire, caregivers were asked ‘On an average day, how many hours do you spend providing care for this woman?’ (open-ended) and ‘What type of assistance do you provide for this woman?’ (all that apply: personal care, household tasks, financial assistance, other/specify). Regardless of length, caregivers reported providing an average of 22.5 h of care per day and described taking on myriad responsibilities including attending to patient’s personal care needs such as bathing and feeding (98%), managing household responsibilities (67%), and providing financial assistance to their patient (47%). Caregivers described being constantly on call, even if they were working elsewhere, and often slept in the same room or house as their patient to provide care throughout the night. Unsurprisingly, those who reported not working outside of the home were less likely to have provided financial assistance (n = 3) compared to those working (n = 15).

Interviews revealed caregiving circumstances were positively and negatively influenced by supports and stressors surrounding their role. These occurred within intersecting social, economic, emotional, and physical experience domains. Participants reported spending most of their time with their patient, sacrificing their own desires and plans, often alluding to the fact that they could see no other options. Alongside commonalities, notable differences emerged by caregiver social context, such as the receipt of encouraging words, and by available resources, such as financial assistance from others, as well as by personal characteristics such as gender. Experiences were also strongly associated with caregiving length, patient care needs, and the challenges fistula patients themselves faced including stigma and relationship strain, inadequate health care access, and income interruptions. Finally, caregiving experiences differed between community and facility settings. Community-based provision of care included all activities outside of the hospital and was characterised by unique stressors, including feeling ill-equipped to manage their patient’s physical and emotional symptoms, and supports, including social and financial help. Facility-based care entailed support given during the pre- and post-operative period surrounding fistula repair in the hospital and provision often included physical stressors but also involved emotional reinforcement.

Social experiences and consequences

The intensity of caregiving and prioritisation of patient needs had broad social impact, affecting nearly all other relationships in caregivers’ lives. Caregivers reduced engagement with other family and community members and paused their educational or career progression. Caregivers also reported stigma, strained marital relationships, and estrangement from extended family and friends. These social experiences were inextricably linked with emotional experiences as well as their economic experiences as their capacity for relationships and for work were reduced.

Caregivers described reducing their community involvement to prioritise their care recipient’s needs. Their decreased ability to attend events and meet social obligations, visit friends or distant family, or share meals with others weakened their social relationships and had social implications. One person explained, ‘I can’t attend a party and leave the patient. If anyone invites me, I have to explain to them that I won’t be able to attend because I have a patient’ (Sister-in-law, age 38). Some described strained relationships because of increased tangible support needs while caregiving, ‘There are those who have started rejecting us because they know that whenever we call them, we will be asking for money, so they no longer pick our calls’ (Female Friend, age 30).

Similarly, caregivers’ immediate and extended familial relationships shifted. Caregivers struggled to connect with extended family in-person and reported feeling absent from their immediate family, including their children. One caregiver shared, ‘I have a daughter who helps me out but in terms of parental love, I just find myself not giving them as much time as I used to’ (Female Friend, age 30). Several respondents reported redirecting time and resources intended for their children due to caregiving, sometimes leaving children alone, assigning them household or agricultural tasks, and/or lacking sufficient funds for schooling. In some cases, husbands of female caregivers adopted new parenting responsibilities in their absence. One husband (age 33) felt overwhelmed juggling parenting alongside full-time employment and expressed guilt for neglecting his children.

Nearly half (47%) of caregivers were under 30 years and the time- and energy-consuming responsibilities of caregiving coincided with time that would otherwise be spent in education and/or building careers. Caregivers’ aspirations were put on hold and such sacrifices are likely to have a long-term impact on caregivers’ lives.

[…] I cannot continue my responsibility as [a community security officer]; with that role, you cannot sleep. Secondly, I can’t do my farming right now. In fact, I am like a prisoner [… .] it is being in a state where all the work is on a standstill. I cannot do any job before she heals. If I insist and go to work, I may be out there and her condition worsens … what would you do then?. (Husband, age 36)

I would like to study further. However, I [need to pay] for my own tuition fees because there is nowhere mummy will get that money. (Sister-in-law, age 21)

Economic experiences and consequences

Economic concerns were repeatedly shared as capacity for income-generating work was significantly reduced, resulting in financial instability. Lost income was among the most universally reported consequences of caregiving. Simultaneously, caregivers reported increased expenses driven by patient care costs. Family caregivers further described the synergistic economic consequences of the patient’s inability to perform household chores and income generating work. These economic experiences were described to have shaped caregivers’ social and emotional experiences as well as the exacerbated need for income and reduced time to generate it added stress.

For most, supporting their patient was a full-time role which reduced their ability to generate their usual income. One caregiver explained,

Looking for money takes me a lot of time because I leave for work a little late, yet I have to leave from work early [due to caregiving]. That means that I don’t work much. The way you work without any problem is not the same way you work while you have a problem! (Husband, age 35)

It depends on what she wants because I have to provide for her; after all she is the reason why I work. Apart from the fact that I have a job; I do not want her to feel stressed or depressed about anything. I have to give her what she wants. In fact, I always ask her what she wants, and I provide it. (Husband, age 35)

While male caregivers more frequently discussed this problematic reduction in work, it was also reported by females including one that shared, ‘We lost all our work and I don’t have any money to contribute to the social group; this keeps me thinking all day . . . but I have nothing to do, I have to take care of the patient’ (Sister, age 35). Other caregivers described missing opportunities to partake in savings groups, further emphasising financial impacts.

Several caregivers described added expenses including transportation, fistula management supplies (e.g. soap, pads or diapers), and other costs. Prioritising their patient resulted in insufficient resources for other expenses and several caregivers described the broader impact:

The kids need school fees but we have to first take care of the patient. Whichever money we get, she would be the first priority in everything. In other words, we would choose to first cater for [the patient] since it is the most important need. (Sister-in-law, age 24)

Collectively, lost parental income disrupted schooling in addition to increasing household responsibilities among children. One caregiver explained:

I can't lie to you that there is anyone I left responsible for taking care of the home! Maybe that son of mine, but he too cannot stay at home. There are two kids yet they are young … One is 8 years and the other is 10 years. […] They have to take care of themselves. One of them can go out to look for food and the other peels it. […] The husband is always in the mines. He gave up on taking care of the home and he now resides in the mines. He also has many women now. (Mother-in-law, age 55)

Some caregivers and patients received tangible support from the community which reduced individual pressure and improved wellbeing. One caregiver reflected,

Her friends with whom she studied have also helped her much; they have been so caring that they would mobilize and collect money to buy pampers, soap and other necessities for the baby or the mother. They would also send some hard cash and also come to check on her when they are free which too has been a big encouragement to her. (Husband, age 33)

Conversely, those lacking financial support described money as a significant stressor that reduced overall health and wellbeing, underscoring the positive impact of financial support. One explained:

There is too much poverty; I would wish to keep her standards high but we don’t have the money. She would want to use pampers while we are in the village but we don’t have the money to buy pampers worn by mature people. So it is poverty which has been the biggest challenge for us. (Mother, age 43)

Emotional experiences and consequences

Specific emotional stressors and supports arose as from persistent societal perceptions that caretaking is undesirable and a futile endeavour. Caregivers associated this with community misconceptions that fistula is incurable which influenced whether they felt respected and valued and impacted their mental health. On one hand, perceived social neglect or misunderstanding of the condition motivated caregivers and emphasised their sense of significance which provided positive reinforcement and emotional benefit. Some caregivers described feeling appreciated and found some of the caregiving tasks to be fulfilling. In general, caregivers’ emotional experiences were also described to have shaped their social and physical experiences as their mood and wellbeing affected their relationships and overall health.

The emotional wellbeing of many was entwined with the emotional wellbeing of their patient. Accordingly, while misconceptions about condition permanency or a sense that the patient was the only one suffering from fistula led to discouragement and hopelessness for both the patient and caregiver, a belief in likely treatment and the sense of shared experience, on the other hand, positively impacted both. Some caregivers were negatively influenced by the stigma that their patient experienced, had difficulty navigating consequences including abuse and/or abandonment, or were influenced by doubts and misconceptions regarding repair:

They discourage us by saying, ‘you are caretaking for someone who never heals, and it seems you have no idea about what you are treating. Now you deserted your job just because you are taking care of a patient! Leave her at once; she will heal if she wants to and if she doesn’t, that’s up to her.’ In that case I would feel so discouraged. (Sister, age 25)

My moods changed. Even when I was hanging out with other people, it would cross my mind and think, ‘will my wife really heal?’ Even when I am doing my work, I would still think, ‘will my wife heal? Will she live in that condition up to death?’ and since she had even slimmed [lost weight], I thought that she would never heal. (Husband, age 44)

That has affected me. If I refuse to go and fetch water, no one will. If I refuse to cook, we both don’t eat! If I do not wash for her no one will or when I would go to maybe see someone, I come back only to find her annoyed. She would complain, ‘Why did you go and leave me here yet you know that the clothes need to be soaked all the time?’ So, I realize that that is likely to affect me. (Husband, age 23)

I think I have already started to lose [touch with reality] if I may say. It is because I can stay [in my thoughts] and I start to think about so many things to the extent that I feel out of place (socially withdrawn)[…]. It is because of the things that I do on daily basis (caregiving tasks) whereby all time you are [emotionally] up and down. Sometimes I feel drowsy and even develop headache. (Sister, age 23)

What has changed is that there is a time you get lost in thoughts and when you realize that you are thinking too much you ask God, ‘Please stop this.’ […] You have to think, ‘How the future will be?’, ‘How will I earn?’, ‘I haven’t planted anything!’ such thoughts are always there in my heart. ‘How is my home?’ ‘How are my kids?’ ‘Are they suffering from jiggers (fleas) now or not?’ ‘Are they still alive or not?’ ‘Are they sick?’ all that is always on my mind. However, you have to replace those worrying thoughts with happiness in your heart. (Mother-in-law, age 55)

I think it has made me more mature. You see she may need something, like bathing her! Imagine bathing a mature adult, change her clothes and dress her in her knickers and things like that! So, I would sometimes ponder, ‘If there are people that are that sick, who am I then?’ (Daughter, age 22)

They see me as their hero because I have been there for her. The patient too shows her appreciation because sometimes we may be in a middle of a conversation and she abruptly says, ‘thank you for taking care of me.’ She then asks me about my future plans such that in case she heals, she as well finds a way of helping me. Family members are thankful, in other words they give me a special respect which is different from the one they used to give me before. (Daughter, age 22)

Physical experiences and consequences

Wide-ranging physical consequences emerged related to caregiving responsibilities including both acute and chronic pain. Many caregivers reported physical pain resulting from unusual sleeping conditions and several described pain from repetitive caretaking tasks including carrying, dressing, and feeding their patient. They also reported secondary physical consequences related to physical household labour that they could no longer afford to hire out. These physical experiences were described to impact caregivers’ social and emotional experiences as their energy to care for themselves and their relationships narrowed.

Common caregiving tasks included physical jobs such as cooking, cleaning, and fetching water in addition to attending directly to their patient’s eating, bathing, and other needs requiring them to be on their feet. One caregiver described the physical toll of caregiving as the most significant consequence; pointing to her lower body, she shared, ‘I feel a lot of pain. Whenever I walk, the pain slopes down the legs. Now these feet you see here look like they are dead!’ (Mother-in-law, age 55). Several also described the physical toll of household chores and other labour because of reduced income associated with caregiving. One husband reported: Since I am considerate to her, we don’t dig the same way we used to before she got sick. We now dig a small area. I would have hired a worker to assist but I don’t have the money to pay him. So, it is me that who has to strain harder and dig because that money I would pay that worker would instead support us. I am working so hard […] it is getting hard for me. (Husband, age 44)

Others described physical manifestations of psychological stress. One caregiver reported developing high blood pressure which she perceived as associated with the added stress of supporting her patient.

Self-neglect was a prominent theme as caregivers routinely ignored their own needs to continue providing support. Not unlike their emotional experiences, caregivers’ physical experiences were structured by the physical needs of their patient. Many caregivers reported new sleeping arrangements, often resting on a hard floor or cot near their patient’s bed to provide around-the-clock care, which compounded physical symptoms due to interrupted sleep and discomfort. One daughter described:

The activity which has been a burden to me is carrying her since she became so weak. I would have to lift her, make her sit and then give her what to drink and then change her clothes. Now since her sickness was so serious, I would at times not sleep at all since she would cry and shout for help. (Daughter, age 34)

While physical consequences were not always strongly emphasised, they may have been underreported as many caregivers prioritised their patients’ physical circumstances and needs over their own and the physical burden of caregiving was commonly reported as an afterthought. Although many caregivers moved quickly past reports of physical symptoms, some described more severe consequences. In both instances, it was common for caregivers to convey a perceived need to ignore or deny their own pain to support their patient. One detailed:

Personally, my leg got a problem in that it somehow became disabled. Now I have been moving a lot and if I add on carrying her, this leg gets injured, and yet I sleep down on the floor. By the time I get up, [my leg] would feel paralyzed yet I would have to take care of the patient. […] This leg has been painful but I don’t have any option but to take care of the patient; I would endure walking with it all the way to the pharmacies and clinics to buy the drugs the doctors have prescribed, and even if I feel so weak, I would have to drag [my leg] and walk [to] I help her. (Daughter, age 34)

The self-neglect of physical pain has the potential for prolonged and chronic physical harms among caregivers.

Notable differences by caregiving length

Despite most (70%) caregivers in this study reporting having provided care for less than 3 months, unique experiences arose from further analysis of the 8 caregivers providing longer-term care (i.e. 1 year or more), revealing semi-permanent changes to caregiver family structure and work to provide unpaid care. Longer-term caregivers were largely women (7/8) and not working outside the home (5/8). They found resourceful ways to generate just enough income to sustain themselves and their patient: ‘My earning is minimal. What I earn is what I spend to take care of her’ (Mother, age 34). While expenditures increased and income decreased for all caregivers, longer-term caregivers changed work routines and opportunities more permanently and spoke more frequently about recurring fistula management supply costs (e.g. pads and soap). Additionally, their responsibilities extended to caretaking for their patient’s dependents. Long-term caregivers narrated their experience as accepting a new way of life, shifting everything to be present with their patient. The stability of their caregiving routine ultimately meant that the hospital stay was acutely disruptive, and several longer-term caregivers expressed concern for gardens, children, or other commitments at home: ‘I have been undergoing vocational training but since we came here in the hospital, I am unable to continue with that training until we leave this place’ (Daughter, age 19). This underscores how the circumstances of their patient’s specific needs dictate the caregiver’s experience.

Notable differences by gender

Few caregivers interviewed were male (16%, six husbands, one son). Meaningful differences across the intersecting domains described above were noted by caregiver gender, some likely driven by the caregiver-patient relationship and prevalent gender norms. Males more consistently benefitted from social support and shared less in patient stigma. Males more frequently described feeling respected and receiving sympathy from their community. Some males received informative care-seeking advice, and some were granted protected leave from employment to fully immerse in caregiving tasks.

Married caregivers reported negative impacts to their marriages, yet gendered differences in societal pressures were noticeable. Female caregivers were doubly burdened by managing their own households while taking on similar tasks for their patient, and they shared the sentiment that they had no choice but to put their marriage second and accept the consequences. Male caregivers navigated negative community pressure to end their marriages, reporting others’ assumptions or encouragement to divorce their wife whom they were caring for. Misconceptions that fistula is untreatable appeared to increase relationship strain, contributing to community misunderstanding about caregiving motivations. Several husbands suggested community education could address this.

Female caregivers acknowledged a heavy marital strain, sometimes perceived as unavoidable. Several felt unsupported in their decision to provide care. When asked about her marriage, one female who had been caregiving for three or more years responded:

I do not know what to do about that; we just have to persevere. Otherwise, we just gave up, because you can’t imagine I have been caretaking for the patient all this entire time but he has never thought of at least giving me a phone call or coming to check on us! It literally means, I do not mind if you don’t come back; I will just get another one. But we just have to leave all that to God. (Sister, age 38)

[my husband] just quarrels with me telling me that; ‘it seems; you have failed in this marriage.’ He tells me that I no longer care for him. He said that I chose to help my sick sister instead of him. Actually, [in the beginning] he would give us some financial assistance to use in the hospital until a time came when he wouldn’t give it to us anymore. (Sister, age 23)

This caregiver also felt disrespected by her patient, relating abuse from both husband and patient. The financial, physical, and emotional burden of caregiving resulted in food insecurity, lost weight, and abandonment by the caregiver’s spouse and family, all of which impacted her mental wellbeing.

Married males reported comments driven by the social desirability of fertility suggesting that potential fistula-related infertility warranted concern; in this way, males shared in their patient’s stigma. This also underscores prevalence of infertility stigma, or the persistent relationship between a woman’s worth and her ability to bear children.

They say that I should marry someone else since on her first delivery the baby died, the second delivery the baby died too and for the third she had an operation. They said that we may find ourselves not getting another child because when one gets a fistula operation, some do not get any more children. I also told them, ‘how come I hear that people that had bladder/fistula operations conceive and deliver babies!’ ‘No, it is not true,’ they responded and I just ignored that. They were saying that I should marry someone else and leave this one alone. (Husband, age 23)

Male caregivers commonly described their decision to support their patient as a last resort and a consequence of their inability to identify an alternate, presumably female, caregiver. Male caregivers more frequently juggled their role as the primary household income-earner as 6/7males reported formal work outside the home while 18/36 of females reported this. One said, ‘I had no one to help me out. So, I decided to take care of her myself’ (Husband, age 23).

Less commonly, males described being motivated by sympathy and a sense of spousal responsibility, as demonstrated by one husband:

When my wife was giving birth, I was absent so she went through one-and-half weeks alone, and the caretakers when she was giving birth were from her church; my relatives where abandoning her which wasn’t good. So as someone who has feelings, I had to do this. I had to be with her at the hospital. I just went and took leave from work and I started being by her side. (Husband, age 42)

These realities likely contributed to the disproportionate number of female caregivers and meant that the few male caregivers had the added burden of navigating demotivating gender norms in choosing to take on a caregiving role. Females’ abilities to be empathetic, having experienced pregnancy or expecting to experience pregnancy someday, also shaped their emotional experience. One caregiver explained:

It has made me sad at heart personally because I realize that [women with fistula] go through a very hard time. I would keep quiet and tell myself, ‘For all the kids I have delivered, I thank God that I haven’t acquired it (fistula.)’ It is not an easy condition. I feel so sorry for her; she has no baby but still got [fistula]; maybe you would rather have it but at least with the baby alive. So, it hurts me personally to the extent that I feel like it is on me. (Sister-in-law, age 38)

Females were more likely to report neutral or negative community responses instead of support. When asked whether she felt respected as a caregiver, one replied, ‘They abandoned her to me. From the time she got that problem, no one has ever come to check on us here in the hospital’ (Sister, age 23). This caregiver also described feeling discouraged and judged for supporting her patient, ‘[…] someone even tells you ‘where will you take her and what will she ever do for you in life’ and that kind of thing’ (Sister, age 23). Loneliness related to limited communication and understanding from their community was shared by several female caregivers.

Male caregivers, on the other hand, largely reported praise even though their caregiving role deviated from norms. Narratives of male caregivers described support from varied sources:

Some of them, especially the ladies, care so much to thank me. ‘Thank you for caring for her,’ they say. In fact, I hear that mostly here at the hospital; most of the ladies thank me and say, ‘It is hard to find a man like you who cares that much for his wife, who has to stick around every day to help his wife in one way or the other’. In that case I feel motivated. (Husband, age 33)

Community member surprise at the male caregiver didn’t trouble or discourage males. One articulated, ‘People are asking me, ‘you, doesn’t your wife have a family, where’s her mother or sister? Why you? There’s this phobia that men shouldn’t take care of women but me I am comfortable with it’ (Husband, age 42).

Finally, caregiving differentially impacted male vs. female caregiver employment experiences. Despite reduced work capacity and resulting income loss, males largely maintained their jobs. One caregiver shared, ‘My job is safe; they are fully aware that I had to attend to my sick wife. Three of my workmates have visited me; my boss has also rung to know how we are doing’ (Husband, age 42). Females nearly unanimously reported leaving or losing their jobs because of caregiving.

Caregiver experiences at the hospital

While the caregivers in this study provided care both within and beyond the hospital stay surrounding their patient’s surgical repair, unique caregiving experience in the hospital setting were emphasised, both negative and positive. Caregivers were challenged by physical and emotional discomfort staying at the hospital and grappled with inadequate resources. Simultaneously, some reported supportive comradery with the other caregivers and patients.

Caregivers repeatedly described costs during their patient’s hospital stay as fiscally and emotionally burdensome. Transportation was a significant cost, particularly among those unable or unwilling to sleep at the hospital. One caregiver outlined, ‘[…] now you have to take a taxi because you’re rushing to meet your patient. This requires you to use more money for transport compared to what you were used to’ (Friend, age 30). Some caregivers were charged extra for patient transport, describing ‘they used to charge us 8,000Ush [about $2.19 USD] but when she got sick, the cyclist started charging us 26,000Ush [about $7.13 USD]. He said, "I will take you safely because your wife is sick. I do not ride recklessly such that I do not cause more injury"’ (Husband, age 23). One caregiver named money as the biggest challenge during the hospital stay, lamenting ‘[…] the expenditure has been so high that I cannot even calculate how much I have been spending daily! You see I have to leave them with money to buy food at the hospital, money to buy water and money to buy pampers’ (Husband, age 33).

For most, staying in the hospital with their patient required sacrificing a variety of personal amenities and dignity due to limited resources and privacy. Many expressed physical consequences from sleeping at the hospital without access to a mattress, describing aches and pains as a result. One caregiver explained, ‘What is challenging me is that I am at the hospital and I don’t sleep like how I was sleeping at my home. I sleep on the floor and I wake up with an aching body’ (Sister-in-law, age 38). Despite harsh personal consequences, caregivers largely reiterated that their time at the hospital was about their patient and they minimised negative experiences. One shared:

I volunteered to do that but before I came here, I was one month pregnant but because I was sleeping on the floor, I had a miscarriage. However, I ignored that as I felt it was more important for the patient to be better. That is the only inconvenience I saw there. I got some sickness, yet I have to do the patient’s activities, so I would do them with lesser energy, but I endured because I knew there was no one else available to do it. (Sister-in-law, age 26).

Privacy ceases if you are here in hospital. You have to keep the shyness away and just do anything whether people are watching you or not. For instance, urinating or washing your inner clothes in public! Besides, you could also see that every lady around goes through the same and that makes you too to feel free to do it openly without hiding. Privacy is not much here. (Daughter, age 22).

Once in a while if there’s no person on the bed, you can remove the mattress and sleep but in most cases you sleep on the floor. And some floor parts are wet because we have leaking mothers, so you wake up when you’re soaked. It is that bad (Husband, age 42)

Caregivers’ experiences interacting with medical staff were mixed. Several caregivers expressed a mix of gratitude, relief, and solidarity for the providers caring for their patient, exemplified by narratives such as:

I haven’t felt so bad taking care of her and it has made me joyful towards the doctors treating that illness because they haven’t given up on those patients. […] I felt happy because I found here many people yet before I thought that it was only happening to my patient, and I thought maybe she was not going to heal. I have now witnessed people that have been healed and even those that haven’t been healed yet, they are going to be treated. […] I feel valuable because I have taken care of her and even among other patients available, there are some that don’t have caretakers and I would assist them with what they need. (Aunt, age 43)

Caregivers described similar sentiments toward other caregivers and shared advice with one another. Still, at times, some caregivers reported being dismissed or bossed around by hospital staff. One shared:

So many things are happening. Some of us think that us caretakers we’re not well treated by the medical personnel. There are times when the doctor tells you to ask the nurse to dress the patient’s wound and when you tell the nurse she in turn commands you the caretaker to do it so … they’re changing roles and that’s why you see many women there are rotting. (Husband, age 42).

The hospital experience was emotionally challenging as caregivers observed human suffering compounded by a strained health workforce. The empathy common among caregivers often resulted in added emotional burden and one caregiver explained, ‘You get to see many patients; you see one crying while the other’s foot is whatever […] It discourages me’ (Sister-in-law, age 21). Some caregivers described stressful interactions with overworked hospital staff, particularly at night, and shared, ‘I wish they could have 3 shifts because [those on night duty] really get fed up with us’ (Friend, age 30). Caregivers expressed varying degrees of helplessness; one reported: ‘My patient says that the catheter which was inserted during her operation caused all the problems she’s going through. She was complaining of the pain, but the nurse was just asking her to keep quiet’ (Sister, age 35).

Finally, caregivers’ time in the hospital entailed time away from their community. Several reported no visitors during their patient’s hospital stay, which was most vividly described by married caregivers and caregivers with children.

The unique toll on the children of caregivers was a critical theme in need of additional exploration. One caregiver described the impact her patient’s hospitalisation had on her children, due to household responsibilities:

I didn’t call their school to tell them that they should allow them to attend class and I send their school fees later, but I had already bought the scholastic materials – that is where I found problems. The other thing was the animals at home – like the goats, hens, etc. The children have to first take them to graze before they go to school. If they do it, they would go to school late and they would find challenges with the school authorities for going late to school. I am not there to help them. (Sister, age 42)

Discussion

Our results highlight individual and systemic factors impacting the experiences and consequences of informal caregivers for female genital fistula patients. Caregivers’ day-to-day physical, social, economic, and emotional experiences were influenced by the broader social context which encompassed their sociodemographic characteristics, their ability to access sufficient support and resources, and their patient’s characteristics and needs that shaped caregiving responsibilities and environment. Similar to recent literature, this study found that informal caregivers make personal sacrifices, regardless of the stressors or supports they are afforded, in order to meet the multifaceted needs of their patients (Adejoh et al. Citation2021).

Caregivers of fistula patients in our study, like others, experienced social and economic strain exacerbated by poverty (Adejoh et al. Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2017). These and other factors resulted in stress, and mental and physical health consequences. Our findings align with a global literature review which identified universally elevated depression, sleep problems, and perceived stress among caregivers.(Koyanagi et al., Citation2018) Another study analysing the experiences of informal caregivers of advanced cancer patients in Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria, summarised that accepting the unpaid work and added expenses such as transportation and caregiving supplies is likely to have sustained financial impact (Adejoh et al. Citation2021) participants in our study similarly outlined these costs as burdensome. Finally, informal fistula caregivers in Ghana reported income loss, weakened personal relationships, and disrupted sleep and nutrition, similar to our study participants (Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015). Our findings and recent literature portray the all-encompassing nature of caregiving as inevitably restricting social involvement by reducing time spent with social supports and increasing risk of adverse mental health and other outcomes for the caregiver.

This study also affirmed caregivers’ management of their patient’s physical and emotional health support needs (Adejoh et al., Citation2021). This entailed navigating societal perceptions and misconceptions of female genital fistula as well as witnessing the emotional lows of their patient. At the other end of the spectrum, these results demonstrated how the caregiving role provoked existential reflection and, for some, an added sense of purpose (Sun et al., Citation2016) Further, patient’s practical needs such as assistance with personal hygiene tasks and getting to and from bed unfortunately resulted in physical consequences for some caregivers (Sanuade & Boatemaa, Citation2015). Caregivers described acute and chronic pain because of their caregiving tasks and some reported physical manifestations of added psychological stress.

The majority of caregivers in our study, similar to past findings, were female relatives such as mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts, etc. (World Health Organization, Citation2017). Overrepresentation as caregivers limits the education and workforce participation of females in their communities. The female caregivers in our study were already less likely to report paid work while caregiving, aligning with country-wide gender gaps suggesting that nearly half of working women remain unpaid (Kasirye, Citation2011). Interestingly, our limited sample of male caregivers were almost all patient’s husbands whereas female caregivers relationship with their patient varied widely. While research in this area is lacking, the absence of patient’s brothers, fathers, or other male figures may be driven by norms of masculinity in Uganda (Barageine et al., Citation2016).

Our results suggest several areas for future research including nuances of caregiving experiences by caregiving length, caregiver gender, employment status, and the inadvertent neglect of the caregivers’ children. There is a growing consensus that complete reliance on family members and close friends to fill the caregiving role for long-term care is not sustainable, particularly where familial relationships are already strained throughout treatment and reintegration, without the added burden of caregiving (Jarvis et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Our study also identified unique benefits to caregiving including feeling valuable and relationship improvement with their patient, particularly for spouse or child caregivers. Identifying effective strategies to mitigate caregiving burdens while protecting or enhancing the benefits should be further explored. Finally, our study identified a variety of interrelated aspects of caregiver setting and length suggesting that holistic strategies would be most effective. The social and emotional experiences of caregivers had particularly bidirectional relationships with the other domains and are worth targeting investment. Additionally, while we found several unidirectional relationships, between physical and social or between economic and emotional for example, the tangling of experiences likely varies by context and population, requiring further study.

Caregivers in our study uniquely faced a mix of praise and judgement due to the stigma of their patient’s condition. Experiences appeared to be similar for caregivers for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV), despite the fact that fistula is often curable while HIV/AIDS is chronic. Research has found that caregivers for PLHIV endure a mix of physical, emotional, and financial consequences that can adversely impact their overall quality of life, consistent with our findings (Chandran et al., Citation2016). Additionally, our findings underscore caregiving’s duality across facility and community settings, identifying the unique burdens and benefits within each. In facility settings, caregivers reported challenging conditions but a sense of comradery with other caregivers. In community settings, caregivers described added household responsibilities although they were often encouraged by recognition from family members or friends. The Ghanaian study on community-based caregiving similarly highlighted a mix of unexpected challenges and joy described by the caregivers (Jarvis et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, we recommend further exploration of context-specific caregiver experiences to inform long-term solutions for each setting. Solutions should account for diverse lengths of time spent caregiving which depend on the length of time a patient lives with an unrepaired fistula. Additionally, caregivers’ presence in both settings may provide a unique opportunity for capacity building. During caregivers’ extended stays in the hospital with their patient, additional efforts could be made to equip them to support holistic reintegration following discharge. Programmes and policies may be informed by recommendations to support caregivers for PLHIV and other chronic diseases including training caregivers in problem-focused stress management strategies and relaxation techniques, bolstering formal social support, and educating about realistic goal setting to encourage healthy caregiving (O’Neill & McKinney, Citation2017).

Centreing the caregiver perspective is a strength of this study as it expands the limited understanding of care in this context (World Health Organization, Citation2017). The inclusion of caregivers that provided facility- and community-based support at various stages illustrated the spectrum of experiences among caregivers for fistula patients. This study is limited by all study participants originating from one hospital whose caregiver demographics may not be representative, and the lack of dyadic caregiver-fistula patient data. Additionally, the facility-based data collection setting may have influenced responses given the unique acuity and psychosocial experiences within hospitals. For example, caregivers interviewed in a hospital setting with which they associated trauma or care gaps may have emphasised their acute stressors or highlighted burdens more than if they were interviewed at home after their patient’s repair surgery.

Conclusion

Informal caregivers are likely to remain essential to the recovery and reintegration of individuals with female genital fistula before, during, and after treatment for the foreseeable future. In the short-term, understanding caregiver experiences and their social contexts may inform efforts to meaningfully increase support and ensure the feasibility of the caregiving role, particularly in limited resource settings. Additionally, long-term investments are needed to further strengthen the health care system including training and support for a more robust health workforce along with capacity building and resource mobilisation to increase facilities with fistula-related knowledge is needed to address the preventable and largely curable condition of genital fistula. Systems strengthening should include improving timely access to high quality emergency obstetric care as well as training to recognise and appropriately refer patients with signs of fistula. Findings from this study have the potential to inform programmes and policies that simultaneously increase needed caregiving supports while eliminating or mitigating stressors. Improving the caregiving experience is likely to improve the patient experience in addition to other positive outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank our study participants for sharing their time and experiences with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The research team has purposefully maintained the caregiver’s use of the word ‘patient’ to describe care recipients having endured female genital fistula.

References

- Adedeji, I. A., Ogunniyi, A., Henderson, D. C., & Sam-Agudu, N. A. (2022). Experiences and practices of caregiving for older persons living with dementia in African countries: A qualitative scoping review. Dementia (basel, Switzerland), 21(3), 995–1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211065398

- Adejoh, S. O., Boele, F., Akeju, D., Dandadzi, A., Nabirye, E., Namisango, E., Namukwaya, E., Ebenso, B., Nkhoma, K., & Allsop, M. J. (2021). The role, impact, and support of informal caregivers in the delivery of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A multi-country qualitative study. Palliative Medicine, 35(3), 552–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320974925

- Adler, A. J., Ronsmans, C., Calvert, C., & Filippi, V. (2013). Estimating the prevalence of obstetric fistula: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-246

- Barageine, J. K., Faxelid, E., Byamugisha, J. K., & Rubenson, B. (2016). ‘As a man I felt small’: A qualitative study of Ugandan men’s experiences of living with a wife suffering from obstetric fistula. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 18(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1089325

- Chandran, V., Madi, D., Chowta, N., Ramapuram, J., Unnikrishnan Bhaskaran, U., Achappa, B., & Jose, H. (2016). Caregiver burden among adults caring for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in southern India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 10, OC41–OC43. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/20076.7865

- Conde-Sala, J. L., Garre-Olmo, J., Turró-Garriga, O., Vilalta-Franch, J., & López-Pousa, S. (2010). Differential features of burden between spouse and adult-child caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: An exploratory comparative design. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(10), 1262–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.001

- de Bernis, L. (2007). Obstetric fistula: Guiding principles for clinical management and programme development, a new WHO guideline. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 99, S117–S121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.06.032

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (2011). Processing fieldnotes: Coding and memoing. In Writing ethnographic fieldnotes (pp. 171–197). The University of Chicago Press.

- Gebremedhin, S., & Asefa, A. (2019). Treatment-seeking for vaginal fistula in sub-saharan Africa. PLoS ONE, 14, e0216763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216763

- Gertrude, N., Kawuma, R., Nalukenge, W., Kamacooko, O., Yperzeele, L., Cras, P., Ddumba, E., Newton, R., & Seeley, J. (2019). Caring for a stroke patient: The burden and experiences of primary caregivers in Uganda – A qualitative study. Nursing Open, 6(4), 1551–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.356

- Jarvis, K., Richter, S., Vallianatos, H., & Thornton, L. (2017). Migration, health, and gender and Its effects on housing security of Ghanaian women. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4, Article 233339361769028. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617690288

- Kasirye, I. (2011). Addressing Gender Gaps in the Ugandan Labour Market. 4.

- Keya, K. T., Sripad, P., Nwala, E., & Warren, C. E. (2018). “Poverty is the big thing”: exploring financial, transportation, and opportunity costs associated with fistula management and repair in Nigeria and Uganda. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-018-0777-1.

- Koyanagi, A., Vancampfort, D., Carvalho, A. F., DeVylder, J. E., Haro, J. M., Pizzol, D., Veronese, N., & Stubbs, B. (2018). Depression, sleep problems, and perceived stress among informal caregivers in 58 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: A cross-sectional analysis of community-based surveys. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 96, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.001

- Lafferty, A., Phillips, D., Fealy, G., Paul, G., Duffy, C., Dowling-Hetherington, L., Fahy, M., Moloney, B., & Kroll, T. (2022). Making it work: A qualitative study of the work-care reconciliation strategies adopted by family carers in Ireland to sustain their caring role. Community, Work & Family, 0, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2022.2043826

- Mitchell, M. M., & Knowlton, A. (2009). Stigma, disclosure, and depressive symptoms among informal caregivers of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23, 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2008.0279

- O’Neill, J. F., M.D., McKinney, M. P. H. M. M., Resources, P. D. U. S. H. & Administration. (2017). S. A Clinical Guide to Supportive and Palliative Care for HIV/AIDS. https://www.thebodypro.com/article/clinical-guide-supportive-palliative-care-hiv-aids-chapter-20-car.

- Ruder, B., Cheyney, M., & Emasu, A. A. (2018). Too long to wait: Obstetric fistula and the sociopolitical dynamics of the fourth delay in soroti, Uganda. Qualitative Health Research, 28(5), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317754084

- Sadigh, M., Nawagi, F., & Sadigh, M. (2016). The economic and social impact of informal caregivers at mulago national referral hospital, Kampala, Uganda. Annals of Global Health, 82, 866–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2016.06.005

- Sanuade, O. A., & Boatemaa, S. (2015). Caregiver profiles and determinants of caregiving burden in Ghana. Public Health, 129(7), 941–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.05.016

- Sun, V., Kim, J. Y., Irish, T. L., Borneman, T., Sidhu, R. K., Klein, L., & Ferrell, B. (2016). Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers. Psycho-oncology, 25(12), 1448–1455. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3987

- Tatangelo, G., McCabe, M., Macleod, A., & You, E. (2018). “I just don’t focus on my needs.” The unmet health needs of partner and offspring caregivers of people with dementia: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 77, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.011

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics Kampala, Uganda and The DHS Program ICF. (2018). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016.

- UNFPA. (2021). Obstetric Fistula & Other Forms Of Female Genital Fistula: Guiding principles for clinical management and programme development. https://www.unfpa.org/publications/obstetric-fistula-other-forms-female-genital-fistula.

- UNFPA. (2016). Some Problems Don’t have an answer- this one does. End Fistula. https://endfistula.org/what-is-fistula.

- United Nations General Assembly. (2020). Intensifying efforts to end obstetric fistula within a decade. Report of the Secretary-General. A/75/264.

- Wall, L. L. (2006). Obstetric vesicovaginal fistula as an international public-health problem. The Lancet, 368(9542), 1201–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69476-2

- World Bank Group. (2016). World health organization’s global health workforce statistics; Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Uganda.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Towards long-term care systems in sub-Saharan Africa. (World Health Organization, 2017).