ABSTRACT

South Asia bears a substantial proportion of the global maternal mortality burden, with adolescents disproportionately affected. Bangladesh has one of the highest adolescent pregnancy rates in the world, with low utilisation of maternal newborn and child health (MNCH) services. This hampers the country’s efforts to achieve optimal health outcomes as envisioned by the Sustainable Development Goals. Male partner involvement is a recognised approach to optimise access to services and decision-making. In South Asia data on male involvement in MNCH service uptake is limited. Plan International’s Strengthening Health Outcomes for Women and Children was implemented across four districts in Bangladesh between 2016 and 2020 and aimed to address these issues. Study results (N = 1,724) found higher maternal education levels were associated with use of MNCH services. After controlling for maternal education, service uptake was associated with male partner support level and perceived joint decision-making. The positive association between male support level and MNCH scale was robust to stratification by maternal education level, and by age group (i.e. adolescent vs. adult mothers). These findings suggest that one path for achieving optimal MNCH outcomes might be through structural-level interventions centred on women, combined with components targeting male partners or male heads of households.

Introduction

Though significant progress has been made in maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) globally, maternal and neonatal mortality rates remain unacceptably high, particularly in low-resource settings (Akseer et al., Citation2017; World Health Organization, Citation2019). Globally, about 295,000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth in 2017 (World Health Organization, Citation2019), and 2.4 million children died within the first month of life in 2020 (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Most maternal and newborn deaths are preventable, reflecting inequalities in access to services (Chou et al., Citation2015), with poverty, malnutrition, and gender dynamics major drivers of inequalities (Akseer et al., Citation2017; Alio et al., Citation2011, Citation2010). Reductions in maternal mortality and infant mortality are captured by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3.1 and 3.2, respectively, and are recognised as key to ensuring more equitable and better health outcomes by 2030 (Sachs, Citation2012; United Nations, Citation2015).

Bangladesh context

South Asia bears a substantial proportion of the global maternal mortality burden; approximately 1 in 5 maternal deaths are reported from this region, which includes the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Akseer et al., Citation2017). Although Bangladesh, the eighth-most populous country in the world (United States Census Bureau, Citation2022), has experienced some of the largest declines in maternal, infant, and neonatal mortality rates in the global South, its rates remain high. As of 2017, maternal mortality was 173 per 100,000 live births, while infant mortality was 24 per 1,000 live births in 2020 (World Bank, Citation2022). Although both rates have declined by approximately 60% in less than two decades, this amounts to an estimated 5,100 women dying per year in Bangladesh (World Bank, Citation2022). Moreover, to achieve optimal health outcomes as envisaged by the SDGs, it is critical to reduce maternal mortality to 70 per 100,000 live births (World Health Organization & Bangladesh, Citation2015). Thus, although significant improvements in MNCH indicators have been observed in Bangladesh, there is still room for further decreases.

To this end, adolescent mothers are at particular risk of poor MNCH outcomes (Nguyen et al., Citation2017), and tend to have low utilisation of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services (Temmerman et al., Citation2015). In particular, a national survey estimated that 59% of adolescent girls years are married by the time they are 18 years of age in Bangladesh (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Citation2019). Unsurprisingly, Bangladesh has one of the highest adolescent pregnancy rates in the world, both in terms of relative proportion and absolute numbers, which contributes to the relatively high rates of maternal mortality in this age group (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Citation2019; Loaiza & Liang, Citation2013). Alongside efforts to redress societal-level inequities for girls and women (Haque et al., Citation2012; United Nations, Citation2021), one approach for optimising adolescent girls’ and women’s access to SRH services is through strengthened engagement of their male partners in pregnancy and MNCH decisions within their families (Alio et al., Citation2011, Citation2010; Gill et al., Citation2017; Jennings et al., Citation2014; Lusambili et al., Citation2021; Yargawa & Leonardi-Bee, Citation2015). Men often have power over decision-making and resources within households and, hence, influence women’s healthcare seeking behaviour, such as the utilisation of antenatal care (ANC), health facility-based delivery, and post-natal care (PNC) services. There is, however, limited data on the impact of male involvement on MNCH service uptake in South Asia, and little is known about how the experiences of adolescent girls and adult women differ.

SHOW project

The Strengthening Health Outcomes for Women and Children (SHOW) project was a 4.5 year (January 2016 – September 2020) multi-country, gender-transformative project implemented in five project countries (Bangladesh, Ghana, Haiti, Nigeria, and Senegal) with funding from Global Affairs Canada (GAC). It aligned with the United Nations’ Every Woman Every Child global strategy to help drive progress towards reaching SDGs 3 and 5. The project targeted remote, underserved regions of Bangladesh, Ghana, Haiti, Nigeria, and Senegal. The SHOW project aimed to address prevailing gender inequality and related barriers at the household, community, and health system by working at three levels: the rights-holders (women and girls), moral duty-bearers (male partners, family, and community members including local traditional and religious influencers) and primary duty-bearers (health officials at different levels of government, and health facilities). Three intersecting gender-transformative strategies that addressed the condition and position of women and girls were employed. The first strategy focused on strengthening women and adolescent girls’ agency and decision-making (Vijayaraghavan et al., Citation2022); the second engaged men across spheres (from family members to socio-cultural gate-keepers) as active partners and beneficiaries of gender equality; and the third strategy addressed systemic gaps by focusing on enhancing accountability of health workers and improving quality of care that is gender responsive and adolescent friendly.

Of these strategies, SHOW implemented male-engagement interventions in all project countries from 2017 to 2019. These interventions promoted positive masculinities and engaged men in the continuum of MNCH/SRH through a range of contextual interventions including through men’s and adolescent boys’ groups, broad social and behavioural change communication, and targeted onboarding of traditional and religious leaders in communities to reinforce positive masculinity. As part of the evaluation of the project, baseline and endline surveys were administered to women and their male partners/heads of households. Focusing on Bangladesh, the main objective of this study was to examine the correlates of MNCH service uptake, including data on male partners/caregivers from baseline surveys. Analysis of programme data was undertaken by the University of Manitoba and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba (HS22622).

Materials and methods

Settings and data source

Baseline cross-sectional household surveys were conducted in 2016, as part of the monitoring and evaluation plan for the SHOW project in Bangladesh. Households were randomly selected from four districts in Bangladesh (Borguna, Nilphamari, Khagrachari, and Kurigram) using multi-stage cluster sampling methods, with inclusion criterion being households with a mother, 15–49 years of age, who had at least one child ('index child') alive under the age of 23 months. The mother of the index child was interviewed as the primary respondent, and a corresponding questionnaire was administered to partners/husbands, or male family members in the absence of a male partner. Both questionnaires included knowledge of MNCH/SRH services, as well as men’s level of support and attitudes towards women’s access and utilisation of such services. The questionnaires also explored attitudes towards, and patterns of household decision-making between men and women around health, marriage of children, education, and household resources. For both intervention and comparison areas, an equal number of adolescent (15–19 YO) and adult (20–49 YO) mothers were sampled. Including 10% oversampling to account for missing/incomplete data, a total sample size of 1680, or ∼420 per each intervention/age group strata was targeted. Study team members entered data from questionnaires into an electronic database, with extensive quality assurance processes implemented to ensure data quality and integrity.

Variable definitions

Outcome variables. The following MNCH service uptake indicators were used in the analyses: (1) four or more antenatal care (4+ ANC) visits; (2) delivery at a healthcare facility; and (3) receipt of post-natal care (PNC) within 2 days, post-delivery, for either the mother or the newborn. Covariates: In addition to the outcome variables, the following variables were a priori selected, and included in the analyses for women, and also used as covariates in multivariable regression models: district, type of settlement (urban, semi-urban, rural), age group, highest level of education, religion, age when married, birth order of index child (first born vs. other), ‘progress out of poverty’ index (PPI),(Desiere et al., Citation2015) and distance (in minutes) to the nearest health facility. The PPI divides individuals into 4 categories: ‘Very Poor’, ‘Poor’, ‘Vulnerable Non-Poor’, and ‘Rich’, based on the cumulative weighted score from 10 questions. Because of the small number of participants classified as ‘Rich’ (n = 63), for the purposes of these analyses, the ‘Vulnerable Non-Poor’ and ‘Rich’ categories were combined.

For men, the following variables from the male questionnaire were included: age group, highest level of education, and indices measuring male partner awareness, and male partner support. Awareness and support indices were the cumulative sum of questions related to awareness and support, respectively. The male partner awareness index was based on five questions, with the first being ‘Have you heard of modern family planning methods (yes or no)?’; men were scored a ‘1’ if they answered ‘yes’. For the rest of this index, men were asked to name at least two danger signs in each of the following domains: pregnancy, delivery, mom after delivery, and newborn after delivery. Men were scored a ‘1’ in each of the domains if they were able to identify at least two danger signs. The index was then based on the total cumulative sum from the 5 questions, for a maximum score of 5. The male partner support index was based on men answering that their level of support was ‘high’ for the following: accessing family planning services; going to the health facility during pregnancy; delivering at a health facility; and accessing PNC for mother and newborn. Men reporting a ‘high’ level of support for each of the above questions (other response options included ‘fair’, ‘poor’, and ‘very poor/completely against’) were scored a ‘1’. Additionally, men were asked if they accompanied their partners to facilities for ANC visits; men reporting ‘yes’ were scored a ‘1’. All scores were added to construct the support index, for a maximum score of 5. Both indices (i.e. awareness and support) were categorised as 1, 2–3, 4–5 in analyses. Lastly, a derived variable was created to capture joint decision-making. Women were scored a ‘1’ for reporting that decisions were made jointly for each of the following: use of family planning methods; visits to health facilities during pregnancy; and delivery at a health facility. Scores were summed, for a maximum of 3 (range 0–3), with this index categorised as 0, 1–2, and 3 for analyses.

Statistical analyses

For descriptive analyses, chi-square tests of association were used to test for statistically significant associations between included variables and the outcomes of interest. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models; thus, three separate logistic regression models were estimated, one for each outcome. Multicollinearity was assessed with VIF and tolerance statistics. In addition to the main analyses, sub-analyses included stratification of models by education level of mothers (less than secondary vs. secondary or more), and age group of mothers at time of the baseline survey [adolescent (<20 years) vs. adult (> = 20 years) mothers]. Finally, plots were created to show the distribution of the MNCH indicators (none, 1, 2, or 3) across key variables; all analyses were conducted with Stata v17 (College Station, TX).

Results

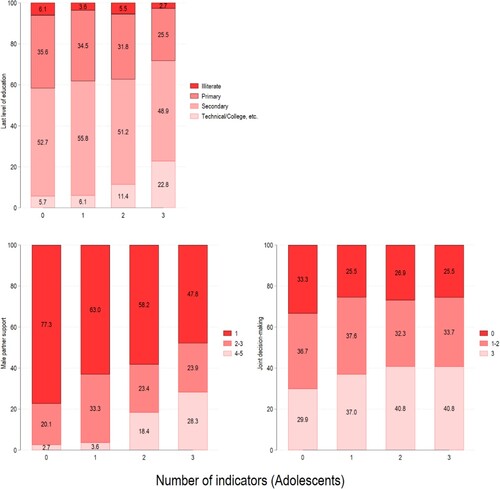

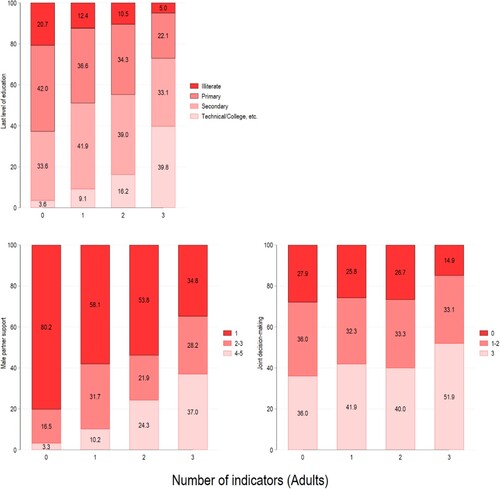

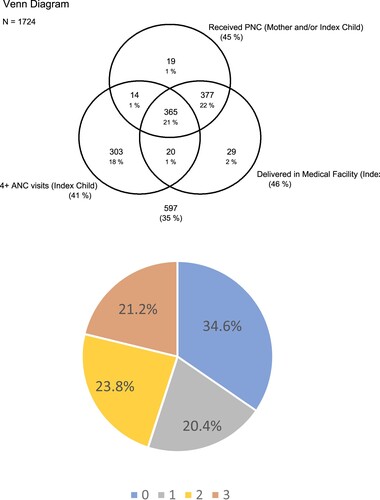

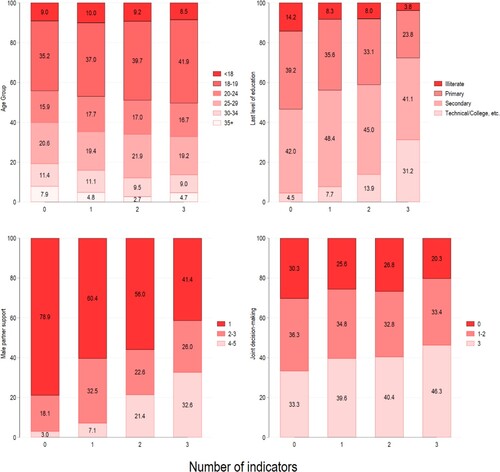

A total of 1,724 participants were included in the final analyses. Of these, 34.6% (n = 597) did not report any MNCH services, 20.4% (n = 351) reported one indicator, 23.8% (n = 411) reported two, and 21.2% (n = 365) reported all three (). also shows the breakdown of MNCH specific services; 41% (n = 702) of women received 4+ ANC visits with their index child, 46% (n = 791) delivered in a medical facility, while 45% (n = 775) received PNC. shows the results from bivariate analyses; those reporting 4+ ANC visits were more likely to be from Kurigram district (48% vs. 31%), compared to those who did not report 4+ ANC visits. Compared to those not reporting 4+ ANC visits, women reporting 4+ ANC visits were also more likely to report having post-secondary education (21% vs. 7%), having only one child who was alive (92% vs. 88%), belong in the ‘vulnerable non-poor/rich’ category (47% vs. 32%), living ≤10 min from a health facility (28% vs. 20%), have more highly educated male partners (50% having at least secondary education vs. 37%), and to report high levels of male partner awareness, support, and joint decision-making.

Figure 1. MNCH service uptake by indicators, and by number of MNCH indicators reported, Bangladesh baseline survey (N = 1,724).

Table 1. Selected characteristics and MNCH service uptake indicators of index child (N = 1,724)Table Footnotea.

Women living in urban or semi-urban areas were more likely to report delivery in healthcare facilities with their index child, compared to women who did not report delivery in a healthcare facility (30% vs. 21%), while those reporting not delivering in a healthcare facility were more likely to be 30 years or older (18% vs. 13%). Similar to the 4+ ANC indicator, and compared to those not reporting delivery in a healthcare facility with their index child, those who reported delivery in a healthcare facility were more likely to have post-secondary education (22% vs. 6%), have only one living child (93% vs. 67%), belong to the vulnerable non-poor/rich category (48% vs. 29%), have a male partner with post-secondary education (18% vs. 6%), report higher levels of male partner support and decision-making. Of note, and in contrast to those report 4+ ANC visits, women reporting delivery in a healthcare facility were more likely to live 31+ minutes away from a healthcare facility (23% vs. 18%). Similar associations were observed for the final MNCH indicator (PNC visit), with women living in urban or semi-urban areas, those with post-secondary education, older age at marriage, belonging to the vulnerable non-poor/rich category, having a male partner with post-secondary education, and high levels male partner awareness, support, and joint decision-making all associated with reporting a PNC visit after delivery of their index child.

In multivariable logistic regression models examining the correlates of 4+ ANC visits (), women from rural areas (aOR: 1.3, 95% CI: 1.0–1.8), those with post-secondary education (aOR: 3.5, 95% CI: 2.0–6.1), and those reporting higher levels of male partner support were more likely to report 4+ ANC visits with their index child. Compared to women whose male partner scored a ‘1’ on the male partner support scale, women whose male partner scored 2–3 were at 1.7 times the odds (95% CI: 1.3–2.2), while those whose male partner scored 4–5 were at 2.4 times the odds (95% CI: 1.7–3.2) of reporting 4+ ANC visits. Of some interest, women living more than 10 min away from the nearest healthcare facility were less likely to report 4+ ANC visits. Compared to those <18 years at the time of interview, women who were 30 years or older were less likely to report delivery in a healthcare facility or PNC after delivery (). For example, women 30–34 years of age were at 0.5 times the odds of reporting delivery in a healthcare facility (95% CI: 0.3–0.8), while a similar effect size was observed in the same age group for PNC after delivery (95% CI: 0.3–0.9). Post-secondary education, being 21 years or older at marriage, having only one living child, being 31 min or more from the closest healthcare facility, and having high levels of joint-decision-making were all associated with both delivery in a healthcare facility and PNC after delivery. Notably, women with male partners scoring 4-5 on the male partner support scale were 9.6 (95% CI: 6.5–14.2) and 11.5 (95% CI: 7.7–17.1) times the odds of reporting delivery in a healthcare setting and PNC after delivery, respectively, compared to women whose male partners scored a 1 on the scale.

Table 2. Adjusted Odd Ratios (aORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI), multivariable logistic regression models for determinant of MNCH service uptake indicators (index child), Bangladesh baseline survey (N = 1,724)Table Footnotea.

shows the results from fully-adjusted models stratified by education level of women to examine the robustness of the association between male partner support and joint decision-making on each MNCH service uptake indicator. Regardless of maternal level of education, higher levels of male partner support were associated with higher scores on index, with the highest levels of male partner support especially associated with delivery in healthcare facility and PNC after delivery. For example, and compared to women whose partner score a 1 on the male support scale, those whose partner scored 4–5 on the scale were at 3.3 times (95% CI: 1.9–5.6) more likely to report 4+ ANC visits. In comparison, women whose partner scored 4–5 on the scale were at 14 times the odds (95% CI: 7.0–26.1) of reporting a PNC visit after delivery.

Table 3. Adjusted Odd Ratios (aORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI), multivariable logistic regression models examining the association between male partner support and joint decision-making on MNCH service uptake indicators (Index Child), stratified by maternal education level, Bangladesh baseline surveya,b.

and show the results of multivariable models examining the correlates of each of the MNCH service uptake indicators, stratified by maternal age at time of the baseline survey [i.e. adolescents (<20 years of age) and adults (20+ years)], respectively. For adolescent mothers () post-secondary education was statistically significant only for delivery in a healthcare facility (aOR: 2.9, 95% CI: 1.1–7.4), while the male partner support was associated with all three indicators, and joint-decision-making associated delivery in a healthcare setting and PNC visit after delivery. For adult women (), post-secondary education and male partner support were associated with all three MNCH indicators.

Table 4. Adjusted Odd Ratios (aORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI), multivariable logistic regression models, determinants of MNCH service uptake indicators (Index Child) among adolescent mothers, Bangladesh baseline survey (N = 814)a,b.

Table 5. Adjusted Odd Ratios (aORs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI), multivariable logistic regression models, determinants of MNCH service uptake indicators (Index Child) among adult mothers, Bangladesh baseline survey (N = 910)a,b.

contains plots showing the distribution of selected characteristics, by how many indicators women reported. There was a disproportionate proportion of women 35 years and over who did not report any of the MNCH indicators; women in this age group composed approximately 8% of those who reported no MNCH service uptake, compared to 5%, 3%, and 5% of women reporting at least one, two, or all three indicators, respectively. Similarly, shows that 14.2% of women reporting no MNCH service uptake were illiterate, compared to less than 4% of women reporting all three indicators. Conversely, 5% of women reporting no MNCH service uptake reported post-secondary education, compared to 31% of women reporting all three indicators. The proportion of men scoring 4-5 on the male support scale increased as a function of the number of reported MNCH indicators, from 3% in women reporting no uptake on any of the MNCH service indicators, to 33% of those reporting all three indicators. A similar pattern was observed with the joint decision-making scale, with the highest level of joint decision-making associated with increased uptake of MNCH service indicators. and show the same analysis, but stratified by adult and adolescent women, with similar patterns observed even in stratified analyses.

Figure 2. Selected characteristics by the number of MNCH service uptake indicators reported, Bangladesh Baseline Survey (N = 1,724).

Discussion

The baseline survey results are in line with recent national estimates from Bangladesh. The 2017–18 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey reported 47% of women receiving 4+ ANC visits, 49% delivering in healthcare facilities, and 52% of mothers and their children receiving PNC within 2 days of delivery (National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF, Citation2020). In comparison, the proportions were 41%, 46%, and 45%, respectively, in the baseline. It should be noted that the SHOW Project targeted remote and underserved regions in Bangladesh, which likely contributed to the slightly lower proportions reporting MNCH service uptake in the baseline sample. While these latest figures show tremendous increases in MNCH service uptake – as recently as 2011 only approximately 1 in 4 women reported receiving 4+ ANC visits (National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF, Citation2020) – only about half of mothers in the baseline study received the recommended MNCH prenatal care. Importantly, our results show that over a third of women in the baseline survey did not receive the recommended level of MNCH care with their index child.

Our findings also highlight the importance of social determinants of health, which MNCH programmes must consider when developing and providing programmes and services. While we found that higher maternal education levels were associated with use of MNCH services, our results also demonstrate that after controlling for maternal education, service uptake was associated with support level of male partners, and to a lesser extent, perceived joint decision-making. In sub-analyses, we found the positive association between male level of support and MNCH service indicators was robust to stratification by maternal education level, and by age group (i.e. adolescent vs. adult mothers). These findings suggest that one path for achieving optimal MNCH outcomes might be through structural-level interventions centred on women, combined with components targeting male partners or male heads of households.

Maternal education has consistently been shown to be associated with positive MNCH outcomes (Chowdhury et al., Citation2018; Rahman et al., Citation2019; World Health Organization, Citation2019); indeed, structural-level interventions that seek to address the social determinants of health, such as education level of women, and which in turn are thought to raise the social-positioning of women, have been indispensable mainstays of programmes aimed at reducing MNCH disparities (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Other researchers have also suggested investments should be made in addressing the mental health of women in order to optimise maternal health outcomes (Rahman et al., Citation2013). At the same time, our findings align with emerging research illustrating the impact of male-side characteristics on use of MNCH services (Ahmed et al., Citation2001; Jeong et al., Citation2023; Kato-Wallace et al., Citation2014; Nguyen et al., Citation2017; Nguyen et al., Citation2018; Nu et al., Citation2020; Raghavan et al., Citation2022; Sarker et al., Citation2021). For example, paternal education was associated with a two-fold increase in health-seeking behaviour for sick neonates (Nu et al., Citation2020), while a cluster-randomized study conducted in Bangladesh demonstrated the positive impacts of engaging husbands in maternal nutrition programmes (Nguyen et al., Citation2018), demonstrating the potential for ‘gender-transformative’ strategies to improve MNCH outcomes (Jeong et al., Citation2023). A recent systematic review of ‘father-inclusive’ interventions on MNCH outcomes in low – and middle-income countries found mostly positive impacts on maternal and couples’ relationship outcomes, with higher variability in early childhood outcomes (Jeong et al., Citation2023). The authors of the systematic review conclude that although potential exists for ‘father-inclusive’ interventions to impact MNCH outcomes, more rigorous evaluations need to be conducted to understand the most effective types of interventions, in addition to unanswered questions related to timing, scaling-up, and targeting of intervention programming (Jeong et al., Citation2023). Ultimately, greater involvement of men requires a supportive and encouraging environment; thus, policy-level and structural interventions are needed to address complex, intergenerational, and localised social norms regarding masculinities (including the normalisation of domestic tasks), and the role and involvement of men in caregiving (Dworkin et al., Citation2015; Kato-Wallace et al., Citation2014; Lansford, Citation2022; Rothenberg et al., Citation2023). It should be noted that although the COVID-19 pandemic has likely caused setbacks, the intended targets of Bangladesh’s National Strategy for Maternal Health are for women to have 70% of their deliveries in healthcare facilities, 80% receiving 4+ ANC, and 80% receiving PNC within 2 days of delivery by 2025, with targets increasing to 85%, 100%, and 100% by 2030 (Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh, Citation2019). Our results suggest that integration of male partner interventions alongside efforts to decrease barriers for maternal education may facilitate achievement of these goals, as some of the 2025 targets have already been achieved within some strata in our study, as seen in Supplemental Figure S1. For example, delivery in healthcare facilities and PNC within 2 days were both at, or greater than, 80% amongst women with the highest levels of male support.

The inequality in MNCH uptake amongst the most vulnerable adults is of some interest; compared to adolescents in similar circumstances (such as illiteracy, and low partner support/awareness), adult women were less likely to report uptake of the MNCH indicators used in this study. This suggests a gap in provision, access, or acceptability of services for women in these situations. Our finding aligns with research showing a substantial gap in MNCH care by socio-economic status in Bangladesh, of which measures such as education level and partner support act as likely proxies (Parvin et al., Citation2022). It is important to keep in mind that generally speaking, outcomes for adolescent mothers and their newborns are unfavourable (Finlay et al., Citation2011), with research showing that adolescents who have given birth and their newborns have poorer nutritional status (including malnourishment), as well as their newborns more likely to have longer-term issues like lower rates of immunisation (Abdullah et al., Citation2007; Nguyen et al., Citation2017). However, others have shown a U-shaped curve in prevalence of adverse outcomes in newborns (like pre-term birth and newborn mortality), with the worst outcomes in the youngest (i.e. 10–14 years) and oldest (i.e. 40+ years) females giving birth (Akseer et al., Citation2022). Research from Zimbabwe has shown that the motivations for ANC visits differ by age, with younger women expressing more fears around fetal health (and thus, preferring more frequent ANC visits), while older women relied more on their previous childbirth experiences, as reasoning to forego ANC visits (Mathole et al., Citation2004) This suggests there likely is a subpopulation of adult mothers who may benefit from more nuanced interventions that incorporate the perspectives of women at different points in their lives.

Limitations

This study had a number of strengths, including having results from both men and women, and the targeting of remote and underserved populations in Bangladesh. Limitations include data being self-reported (and thus prone to social desirability biases) and cross-sectional. For the latter, associations observed could be due to that women who have higher levels of education are given more agency to find men who are more educated on MNCH principles, and/or are more likely to cede some decision-making power to their female partners. The survey also did not address quality in the indicators measured, such as services delivered, or the skill of healthcare workers in health facilities.

Conclusions

The government of Bangladesh has invested heavily in MNCH outcomes, with the national strategy’s intended goal being set for a maternal mortality rate of 70 per 100,000 live births, and neonatal mortality rate of 12 per 1,000 live births. Our results suggest there is a role for incorporating male-side interventions into national programmes, but these should not come at the cost of interventions centred on the empowerment of women, especially those that promote higher levels of education for women. Research should further define the balance needed between male – and female-sided interventions, and the specific types of male-side interventions needed to achieve the most optimal outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the national and regional government stakeholders in the Ministry of Health in Bangladesh, Plan International Bangladesh, and Plan International Canada staff, and the financial support of Global Affairs Canada in support of the Strengthening Health Outcomes for Women (SHOW) Project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullah, K., Malek, M. A., Faruque, A. S., Salam, M. A., & Ahmed, T. (2007). Health and nutritional status of children of adolescent mothers: Experience from a diarrhoeal disease hospital in Bangladesh. Acta Paediatrica, 96(3), 396–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00117.x

- Ahmed, S., Sobhan, F., Islam, A., & Barkat e, K. (2001). Neonatal morbidity and care-seeking behaviour in rural Bangladesh. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 47(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/tropej/47.2.98

- Akseer, N., Kamali, M., Arifeen, S. E., Malik, A., Bhatti, Z., Thacker, N., Maksey, M., D'Silva, H., da Silva, I. C., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2017). Progress in maternal and child health: How has south Asia fared? BMJ, 357, j1608. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1608

- Akseer, N., Keats, E. C., Thurairajah, P., Cousens, S., Betran, A. P., Oaks, B. M., Osrin, D., Piwoz, E., Gomo, E., Ahmed, F., Friis, H., Belizan, J., Dewey, K., West, K., Huybregts, L., Zeng, L., Dibley, M. J., Zagre, N., Christian, P., Kolsteren, P. W., Kaestel, P., Black, R. E., El Arifeen, S., Ashorn, U., Fawzi, W., Bhutta, Z. A., & Global Young Women's Nutrition Investigators, G. (2022). Characteristics and birth outcomes of pregnant adolescents compared to older women: An analysis of individual level data from 140,000 mothers from 20 RCTs. EClinicalMedicine, 45, 101309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101309

- Alio, A. P., Mbah, A. K., Kornosky, J. L., Wathington, D., Marty, P. J., & Salihu, H. M. (2011). Assessing the impact of paternal involvement on racial/ethnic disparities in infant mortality rates. Journal of Community Health, 36(1), 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-010-9280-3

- Alio, A. P., Salihu, H. M., Kornosky, J. L., Richman, A. M., & Marty, P. J. (2010). Feto-infant health and survival: Does paternal involvement matter? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(6), 931–937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0531-9

- Chou, D., Daelmans, B., Jolivet, R. R., Kinney, M., Say, L., Every Newborn Action, P., & Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality working, g. (2015). Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths. BMJ, 351, h4255. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4255

- Chowdhury, S. K., Billah, S. M., Arifeen, S. E., & Hoque, D. M. E. (2018). Care-seeking practices for sick neonates: Findings from cross-sectional survey in 14 rural sub-districts of Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 13(9), e0204902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204902

- Desiere, S., Vellema, W., & D'Haese, M. (2015). A validity assessment of the progress out of poverty index (PPI)™. Evaluation and Program Planning, 49, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.11.002

- Dworkin, S. L., Fleming, P. J., & Colvin, C. J. (2015). The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(sup2), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2015.1035751

- Finlay, J. E., Ozaltin, E., & Canning, D. (2011). The association of maternal age with infant mortality, child anthropometric failure, diarrhoea and anaemia for first births: Evidence from 55 low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Open, 1(2), e000226. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000226

- Gill, M. M., Ditekemena, J., Loando, A., Ilunga, V., Temmerman, M., & Fwamba, F. (2017). “The co-authors of pregnancy”: leveraging men’s sense of responsibility and other factors for male involvement in antenatal services in Kinshasa, DRC. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 409. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1587-y

- Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. (2019). Bangladesh national strategy for maternal health: 2019-2030 (http://dgnm.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dgnm.portal.gov.bd/page/18c15f9c_9267_44a7_ad2b_65affc9d43b3/2021-06-24-11-27-702ae9eea176d87572b7dbbf566e9262.pdf.

- Haque, S. E., Rahman, M., Mostofa, M. G., & Zahan, M. S. (2012). Reproductive health care utilization among young mothers in Bangladesh: Does autonomy matter? Women's Health Issues, 22(2), e171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2011.08.004

- Jennings, L., Na, M., Cherewick, M., Hindin, M., Mullany, B., & Ahmed, S. (2014). Women's empowerment and male involvement in antenatal care: Analyses of demographic and health surveys (DHS) in selected African countries. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 297. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-297

- Jeong, J., Sullivan, E. F., & McCann, J. K. (2023). Effectiveness of father-inclusive interventions on maternal, paternal, couples, and early child outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 328, 115971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115971

- Kato-Wallace, J., Barker, G., Eads, M., & Levtov, R. (2014). Global pathways to men's caregiving: Mixed methods findings from the international Men and gender equality survey and the men who care study. Global Public Health, 9(6), 706–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.921829

- Lansford, J. E. (2022). Annual research review: Cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13539

- Loaiza, E., & Liang, M. (2013). Adolescent pregnancy: A review of the evidence. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/ADOLESCENT%20PREGNANCY_UNFPA.pdf.

- Lusambili, A. M., Wisofschi, S., Shumba, C., Muriuki, P., Obure, J., Mantel, M., Mossman, L., Pell, R., Nyaga, L., Ngugi, A., Orwa, J., Luchters, S., Mulama, K., Wade, T. J., & Temmerman, M. (2021). A qualitative endline evaluation study of male engagement in promoting reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health services in rural Kenya. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 670239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.670239

- Mathole, T., Lindmark, G., Majoko, F., & Ahlberg, B. M. (2004). A qualitative study of women's perspectives of antenatal care in a rural area of Zimbabwe. Midwifery, 20(2), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2003.10.003

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) and ICF. (2020). Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2017-18. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR344/FR344.pdf.

- Nguyen, P. H., Frongillo, E. A., Sanghvi, T., Wable, G., Mahmud, Z., Tran, L. M., Aktar, B., Afsana, K., Alayon, S., Ruel, M. T., & Menon, P. (2018). Engagement of husbands in a maternal nutrition program substantially contributed to greater intake of micronutrient supplements and dietary diversity during pregnancy: Results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. The Journal of Nutrition, 148(8), 1352–1363. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxy090

- Nguyen, P. H., Sanghvi, T., Kim, S. S., Tran, L. M., Afsana, K., Mahmud, Z., Aktar, B., & Menon, P. (2017a). Factors influencing maternal nutrition practices in a large scale maternal, newborn and child health program in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0179873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179873

- Nguyen, P. H., Sanghvi, T., Tran, L. M., Afsana, K., Mahmud, Z., Aktar, B., Haque, R., & Menon, P. (2017b). The nutrition and health risks faced by pregnant adolescents: Insights from a cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0178878. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178878

- Nu, U. T., Pervin, J., Rahman, A. M. Q., Rahman, M., & Rahman, A. (2020). Determinants of care-seeking practice for neonatal illnesses in rural Bangladesh: A community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0240316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240316

- Parvin, N., Rahman, M., Islam, M. J., Haque, S. E., Sarkar, P., & Mondal, M. N. I. (2022). Socioeconomic inequalities in the continuum of care across women's reproductive life cycle in Bangladesh. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 15618. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19888-w

- Raghavan, A., Satyanarayana, V. A., Fisher, J., Ganjekar, S., Shrivastav, M., Anand, S., Sethi, V., & Chandra, P. S. (2022). Gender transformative interventions for perinatal mental health in Low and middle income countries—A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912357

- Rahman, A., Rahman, M., Pervin, J., Razzaque, A., Aktar, S., Ahmed, J. U., Selling, K. E., Svefors, P., El Arifeen, S., & Persson, L. A. (2019). Time trends and sociodemographic determinants of preterm births in pregnancy cohorts in matlab, Bangladesh, 1990-2014. BMJ Global Health, 4(4), e001462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001462

- Rahman, A., Surkan, P. J., Cayetano, C. E., Rwagatare, P., & Dickson, K. E. (2013). Grand challenges: Integrating maternal mental health into maternal and child health programmes. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001442

- Rothenberg, W. A., Lansford, J. E., Tirado, L. M. U., Yotanyamaneewong, S., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K. A., Gurdal, S., Liu, Q., Long, Q., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Tapanya, S., … Bornstein, M. H. (2023). The intergenerational transmission of maladaptive parenting and its impact on child mental health: Examining cross-cultural mediating pathways and moderating protective factors. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(3), 870–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01311-6

- Sachs, J. D. (2012). From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet, 379(9832), 2206–2211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60685-0

- Sarker, B. K., Rahman, T., Rahman, T., & Rahman, M. (2021). Factors associated with the timely initiation of antenatal care: Findings from a cross-sectional study in northern Bangladesh. BMJ Open, 11(12), e052886. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052886

- Temmerman, M., Khosla, R., Bhutta, Z. A., & Bustreo, F. (2015). Towards a new global strategy for women's, children's and adolescents’ health. BMJ, 351, h4414. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4414

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981.

- United Nations. (2021). United Nations entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women (UN-women): Strategic plan 2022-2025.

- United States Census Bureau. (2022). U.S. census bureau current population https://www.census.gov/popclock/print.php?component = counter.

- Vijayaraghavan, J., Vidyarthi, A., Livesey, A., Gittings, L., Levy, M., Timilsina, A., Mullings, D., Armstrong, C., Agency, U. H. A., & Resilience Writing, G. (2022). Strengthening adolescent agency for optimal health outcomes. BMJ, 379, e069484. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-069484

- World Bank. (2022). World Bank open data. Retrieved June 21, 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/.

- World Health Organization. (2019). Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division (https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Maternal_mortality_report.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2022). World health statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals (https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/world-health-statistic-reports/worldhealthstatistics_2022.pdf?sfvrsn = 6fbb4d17_3.

- World Health Organization & Bangladesh. (2015). Success factors for women’s and children’s health: Bangladesh. W. H. Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/178623/9789241509091_eng.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y.

- Yargawa, J., & Leonardi-Bee, J. (2015). Male involvement and maternal health outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(6), 604–612. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204784