ABSTRACT

The Chinese government has been prioritising the strengthening of its primary care system over the past two decades. This study reviews China’s national policies in this domain from 2003 to 2018, incorporating academic literature and interviews with health officials and primary care providers. The aim is to assess these policies in alignment with the government’s reform agenda and the ideal primary care system advocated in the public health literature. Initially focusing on network and infrastructure development, the Chinese government has progressively shifted its focus towards enhancing human resources and improving the service attributes of primary care facilities. Supported by detailed guidelines and increased funding, substantial progress has been made. Despite these advancements, significant gaps persist when comparing the current state of China’s primary care system to the envisioned ideal. To gain a comprehensive understanding of these gaps, it is crucial to consider the Chinese government’s agenda and the country’s unique development trajectory, which has been influenced by its history of planned economy.

Introduction

The Chinese government has significantly increased its efforts to strengthen the primary care system since the early 2000s. In particular, since the launch of healthcare reforms in 2009, strengthening primary care facilities has been one of the few top priorities and one of the three key principles guiding healthcare reforms. These efforts, involving a comprehensive set of measures combined with a substantial injection of government funds, are aimed at strengthening the primary care facilities as the cornerstone of the Chinese health delivery system, which is, in turn, expected to enhance access, quality and efficiency of care for the entire population.

In light of these developments, a rapidly increasing literature has been accumulating to evaluate the progress in China’s strengthening of primary care (e.g. Bhattacharyya et al., Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). These studies noted remarkable progress in China’s primary care system but also complex challenges, such as the insufficient competence of its workforce, weak regulation and incentives that fail to promote quality care and cost saving, and poor performance in managing chronic diseases.

These important studies, mostly contributed by public health scholars, tend to share the primary goal of identifying the weaknesses of China’s primary care system and areas for improvement. As a result, public health frameworks are prioritised over the Chinese government’s own agenda and intention. However, given its very dominant role in delivering health care, the Chinese government’s own intention and policies provide critical explanations for the development of China’s primary care in the past two decades. In directing the focus to the Chinese government’s own policy goals and outcomes, this paper highlights the role of the Chinese government in interpreting the ideal primary care system and setting priorities for policy implementation. These interpretations and priorities, many of which are contextualised in China’s rather unique transition from a planned to a market economy, shed important light on the root causes of many problems within China’s primary care system and why its development has not fully embraced and reflected the standard ideals advocated in the public health literature.

Materials and methods

This study reviews China’s national policies to strengthen primary care between 2003 and 2018. Specifically, it asks: (1) What was the Chinese government’s intention? (2) What have been the major reforms? (3) To what extent has the Chinese government achieved its goals in various aspects of strengthening primary care? To address these questions, relevant policies and documents were compiled from:Footnote1

Health Care Five-Year Plans: Every five years, the Chinese government issues a five-year health work plan to map out strategies to develop the healthcare system.

Health Care Reform Guiding and Supporting Documents: Since the early 2000s, the government has issued several major documents to guide reforms. These documents are accompanied by policy documents on different aspects to specify how reforms should be carried out.

Health Yearbooks: These yearbooks have been published every year since 1983 and document the government’s health work in relation to key aspects.

Health Statistical Yearbooks: These statistical yearbooks have been published every year since 2003 and provide national data on health facilities, personnel, equipment, healthcare expenditures, outpatient and inpatient activities and other health-related statistics.

National Health Services Surveys (3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th): This survey has been conducted by the National Health Commission every five years since 1993 and provides valuable information on the population’s use of medical services.

Collectively, these documents complement each other in providing a relatively comprehensive account of why and how the Chinese government has carried out the strengthening of primary care as well as some key indicators for the outcomes of government efforts. To supplement this data, interviews were conducted with government officials and primary care providers in China between October 2016 and March 2017.Footnote2 These interviews aimed to identify the implemented government efforts and their impacts, providing valuable insights and corroborating information from the government documents. Furthermore, academic literature is incorporated to provide independent evaluations and evidence-based perspectives on government policies, contributing to a well-rounded analysis of the topic.

Data were analysed following a qualitative content analysis approach, guided by the research questions focusing on (1) the government’s intention, (2) the government’s role/interventions and (3) intervention outcomes. Following the tradition in the relevant public health literature (Li et al., Citation2017; Starfield, Citation1998), ‘inputs’ (alternatively, ‘structural characteristics’) and ‘service delivery attributes’ (alternatively, ‘process characteristics’) were used as the two predetermined categories in understanding interventions’ outcome – the strength of the Chinese primary care system. These two categories were further divided into subcategories. ‘Inputs’ was further divided into ‘network completeness’, ‘physical resources’ and ‘human resources’ while ‘service delivery attributes’ was further divided into ‘first contact’, ‘comprehensiveness’, ‘continuity’ and ‘coordination’. During the coding process, the emphasis was to ensure that all the data relevant to each category were identified and examined. Data coded under the same categories and subcategories were collated, compared and then summarised.

Results

The history and rationale

In China, the imperative to strengthen primary care is rooted in the country’s history and development. Established and developed during the planned economy period (1950s–1970s), the Chinese healthcare system was first modelled after the Soviet healthcare system (i.e. the Semashko model) and was characterised by a hierarchical healthcare delivery embedded in the planned economy and the dominant role of the state. Unlike under other dominant healthcare models (e.g. the UK/Beveridge or German/Bismarck models), the equivalent of general practitioners (GPs) who provided comprehensive and continuing care to an individual did not exist; instead, the difference between primary care facilities and hospitals was in capacity – measured mostly by inputs such as the space and number of beds of healthcare facilities, the number of healthcare professionals and the types of medical services provided. At the lowest level of the hierarchical system were the facilities with the least space and beds, fewer specialties and healthcare professionals and a narrower range of services. During the 1970s, when over 80% of the Chinese population resided in the countryside, the primary care system was also predominantly rural, consisting of commune (township) health centres and brigade (village) health stations, which were organised and financed by communes and production brigades. In the small urban sector at the time, primary care was predominantly organised and financed through work units, which were dominated by state ownership (doc-HSY-05). Thus, the provision and financing of primary care used to be an integral part of China’s planned economy.

The early development of the health system in China, as with the Soviet/Semashko model and its variants, was characterised by deliberate planning by the government, where health needs were calculated and translated into estimates of necessary inputs/resources and standards that served as central guidelines for healthcare development (Roemer, Citation1991, pp. 234–236). Constrained by the level of social and economic development, China’s comprehensive primary care system faced significant challenges, notably the severe shortages of key resources such as medicines and capable health professionals. The employment of a large number of paramedical workers, particularly the renowned ‘barefoot doctors’ who received basic medical training while still working as farmers, partially addressed this issue and was recognised as a model by the World Health Organization (WHO) at the time. However, it also resulted in limited competence among health workers and compromised the overall quality of care (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2015).

While retaining some key features from the past planned economy, the Chinese healthcare system was severely disrupted during China’s first two decades of economic reforms (i.e. the 1980s and 1990s), which incrementally and partially introduced market mechanisms. In rural areas, the collapse of the commune system meant that rural primary care facilities lost their major sources of income. At a slower pace, workplaces in urban areas also gradually separated social functions (including small hospitals and clinics) from business activities to prioritise profitmaking. The government maintained price controls, keeping those services involving intensive labour work (such as consultations) at below-cost levels. To compensate for deficits, two mechanisms were retained: a mark-up policy for medicines and high-end technical services, allowing healthcare facilities to sell them above the wholesale price, and the government’s partial financial responsibility for infrastructure development, staff training and salaries. However, constrained budgets and difficulties in fulfilling financial obligations in social services posed challenges for local governments, leading to insufficient government funding for township health centres and village health stations. The situation was exacerbated by increased population mobility and the abolishment of rigid referral systems, after which patients were allowed to freely visit hospitals without any referral from primary care facilities. Many found hospitals to be more attractive given their higher qualified health professionals, advanced diagnostic and treatment equipment and wider range of specialities and services (Bhattacharyya et al., Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2018). The increased demand was welcomed by hospitals, which also faced budgetary cuts from governments while being encouraged to pursue profits from the market. As a result of these developments, primary care facilities experienced a significant decline relative to hospitals (doc-NHSS-01).

In the early 2000s, although the rural network of primary care facilities remained relatively intact (i.e. approximately one township health centre per township and one village health station per village; ), many of these facilities were in a state of disrepair due to insufficient maintenance and repairs, particularly in less developed and economically disadvantaged areas (doc-HYB-01, p. 85; doc-HYB-05, p. 3). In urban areas, the primary care sector was still in its nascent stage of development and appeared insignificant in comparison to rapid urbanisation and the subsequent surge in the urban population. The weaknesses of the primary care system, particularly its diminished public health functions, were starkly exposed during the 2002 SARS outbreak. This health crisis, set against the backdrop of the Chinese government’s shift towards achieving a more people-oriented and balanced approach to economic and social development after two decades of rapid growth, became a turning point that propelled healthcare reform and system strengthening to the top of the government’s agenda (doc-HYB-02, p. 5; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Citation2015).

Table 1. Average resources/capacity of primary care facilities (2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018).

The rationale and priorities for the Chinese government’s primary care strengthening emerged from the historical context outlined above. The primary objectives were twofold. First, to revitalise the rural primary care system and establish a new system to meet the needs of the expanding urban population. These primary care providers were envisioned as the cornerstone for delivering essential public health services (EPHS) and basic medical care to the entire population (doc-HREF-02). Second, strengthening primary care was expected to enhance the overall Chinese healthcare system (doc-HREF-02). The underlying logic was as follows: since similar services tend to be more expensive when provided in hospitals compared to primary care settings, the over-reliance on hospitals leads to increased healthcare expenditure. At the same time, the underuse of primary care facilities results in resource wastage. Therefore, strengthening primary care by making primary care facilities more appealing and redirecting patients away from hospitals was considered a means to improve healthcare accessibility and affordability and overall system efficiency (doc-HREF-02; doc-HREF-08).

The overarching approach

The government has maintained direct control over the primary care network, with almost all township health centres and over 90% of community health centres being publicly owned, while around two-thirds of village and community health stations are also publicly owned (). The funding structure for primary care facilities has remained largely unchanged, with income derived from both government subsidies and user charges. Government subsidies have been used to cover some of the personnel costs of public facilities, allowing for the implementation of various government pricing policies (doc-FIN-01; doc-HREF-10), including below-cost prices for services that require extensive time from health professionals, such as consultations. Meanwhile, the government’s subsidisation of personnel costs is still justified by the fact that the majority of primary care staff are employed in bianzhi positions (a legacy of the planned economy that treats employees in the public sector as state employees and requires public expenditure on their salaries and benefits), making them state employees.

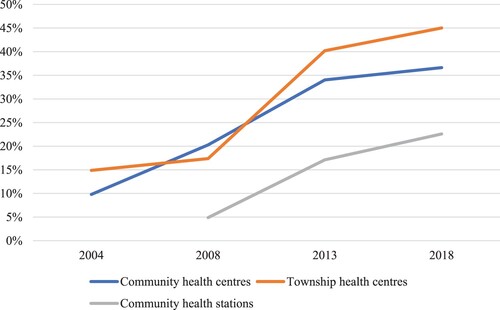

Figure 1. Publicly owned health centres and stations (% of total) (2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018). Source: author’s calculation based on doc-HSY-01; doc-HSY-03; doc-HSY-04; doc-HSY-05.

The 2009 healthcare reforms brought about three major changes in the financing of township and community health centres. The first change was the introduction of the national essential medicines policy (NEMP), which required primary care facilities to sell essential medicines without any profit, ensuring that the retail prices of these medicines were equal to the wholesale prices (doc-NEMP-01). To compensate for the loss of medicine sales profits, the central government set up a specific earmarked fund in 2012, allocating around seven billion yuan each year for township health centres and community health facilities (doc-HYB-11, p. 285; doc-HYB-13, p. 71; doc-FIN-09; doc-NEMP-05). In addition, the government proposed that the price of medical services should be increased to better reflect their costs and reduce the deficits from the sale of medical services. However, price increases have also been limited, given that part of the loss has already been recovered through the earmarked subsidy (doc-FIN-05). Second, the government standardised and substantially increased its funding support for EPHS. Although the government had always assumed the responsibility of financing public health services (doc-FIN-01; doc-FIN-02), the 2009 reforms clarified the specific items to be provided and the amount the government should pay. Third, the government reclarified its financing responsibilities for government-run primary care facilities. In addition to covering staff salaries (including retirees’ pensions), personnel training and recruitment costs, the government also claimed responsibility for paying for deficits when primary care facilities have revenue shortfalls (doc-FIN-03; doc-FIN-05; doc-FIN-08).

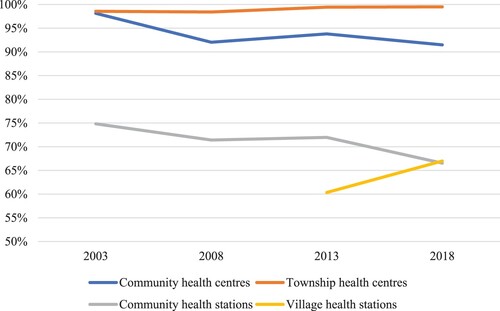

All three changes have been backed by increased government funding. As illustrated in , fiscal subsidies as a percentage of total health centre revenues have increased substantially. In 2004, fiscal subsidies accounted for 15% of township health centre revenues, while by 2018, this had risen to 45%. For community health centres and stations, fiscal subsidies increased from 10% and 5% to 37% and 23%, respectively. Moreover, the government has strengthened its control over primary care facilities through funding-linked performance evaluation. Local governments are obligated to conduct inspections to ensure that primary care facilities have provided medical and EPHS appropriately (doc-FIN-06a; doc-FIN-07a1; doc-FIN-07a2). The results of these inspections are then used to determine the exact funding that primary care facilities receive.

Enhancements in inputs

Network completeness

Much emphasis has been given to the full coverage of the primary care network, which is viewed as the foundation for delivering essential public health and medical services to the entire population. The completeness of the network has been ensured through local health planning, with the central government providing guidelines for the establishment of health facilities (doc-RSRC-01; doc-RSRC-03; doc-RSRC-04; doc-RSRC-08; doc-RSRC-12; doc-RSRC-25; doc-RSRC-26) and local governments making plans to determine the desired number and type of health facilities for their areas (doc-HREF-01). Over time, the government has specified its standards for completeness, which include one government-run township health centre in each township (doc-HREF-07; doc-HREF-09), one community health centre in each neighbourhood (administratively called ‘street’) or area of 30,000–100,000 people (doc-HREF-08; doc-HREF-12) and at least one village health station in every village (doc-HREF-08; doc-HREF-10; doc-HREF-12).

In rural areas where the network had already been relatively complete since the 1970s, meeting the principles meant merging redundant township health centres resulting from the merger of townships or converting them into community health centres as urbanisation continued (doc-RSRC-06). In addition, the coverage of villages by village health stations was maintained, and gaps were filled where necessary. These objectives have been achieved, with the number of township health centres in line with the number of townships and the percentage of villages with their own health station having significantly increased in the 2000s and remained consistently above 92% in the 2010s (doc-HSY-05; ). In cities, the strategy was to fully utilise existing resources such as small hospitals, clinics and township health centres in newly urbanised areas (doc-HREF-02; doc-HREF-08). The network experienced rapid expansion throughout the 2000s, reaching the targets set by the government, and has since continued to grow in alignment with ongoing urbanisation ().

Physical resources

Significantly improving the physical resources for the primary care network was a key priority, particularly during the 2000s and early 2010s when many primary care facilities were viewed as lagging behind the country’s development and faced barriers to providing care (Liang et al., Citation2005). The government made significant efforts to achieve this improvement through substantial investments and the introduction of new standards and targets. At the central level, three major rounds of investments were made to (re)build, expand and purchase equipment for primary care facilities. This included 12.8 billion yuan invested in 2004–2008, 11 billion yuan in 2009–2011 and 21.8 billion yuan in 2012–2015 (doc-RSRC-06; doc-RSRC-10; doc-RSRC-13; doc-RSRC-16; doc-RSRC-23). These subsidies were primarily directed at township health centres, but a minority of village health stations and community health facilities also received funding (doc-HYB-07, pp. 268, 276; doc-HYB-11, pp. 239, 249; doc-HYB-12, p. 342; doc-HYB-14, p. 132). Accompanying the funding was a range of standards specifying the space, functions and equipment that funding beneficiaries should achieve.

Besides direct funding schemes, the central government has relied on nationwide standards to guide the construction and expansion of primary care facilities (doc-RSRC-02; doc-RSRC-07; doc-RSRC-11; doc-RSRC-24). It was mandated that all township health centres meet these standards by 2020 (doc-RSRC-25). It is worth noting that these national standards serve as a minimum requirement, and localities with greater resources are expected to implement higher standards for entry and construction. Many local governments have indeed adopted higher standards and allocated their own funding, resulting in substantial investments in the infrastructure development of primary care facilities across the country (Tan & Yu, Citation2022).

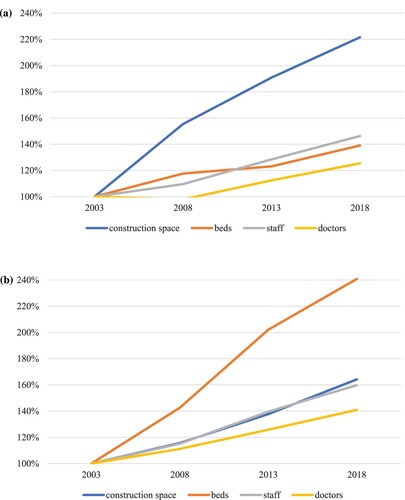

The government’s efforts have led to impressive improvements in the physical condition of primary care facilities. The average amount of physical resources at primary care facilities has expanded rapidly throughout the 2000s and 2010s (; a,b). For example, the average size of a township health centre increased from 1,853 m2 with 15 beds in 2003 to 2,552 m2 with 31 beds in 2013 and, further, to 3,043 m2 with 37 beds in 2018. At the aggregate level, key indicators for physical condition, such as space and the number of beds, had surpassed national standards across all four types of primary care facilities by 2018. Equipment has also been substantially upgraded, with the vast majority of community health centres equipped with ECG machines, B-scan ultrasonography and biomedical analysers (Zhang et al., Citation2016).

Figure 3 (a) Increases in the average physical and human resources in community health centres (2003 value as 100%) (2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018). Source: author’s calculation based on doc-HSY-01; doc-HSY-03; doc-HSY-04; doc-HSY-05. (b) Increases in the average physical and human resources in township health centres (2003 value as 100%) (2003, 2008, 2013 and 2018). Source: author’s calculation based on doc-HSY-01; doc-HSY-03; doc-HSY-04; doc-HSY-05.

Human resources (township and community health centres)

As the physical resources of primary care facilities improved, the weak human resources capacity has increasingly been viewed as a key bottleneck for the development of primary care facilities (doc-RSRC-18). In general, health professionals at primary care facilities have lower levels of education and professional qualifications compared to hospital-based health professionals, making it difficult for them to gain the trust of residents (doc-RSRC-18). Brain drains to hospitals have been common, as many primary care professionals move to hospitals for higher pay and better career prospects once they have gained experience (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Citation2015).

At the central level, the government has proposed a range of measures to enhance the training, professional qualifications and recruitment of health professionals for primary care facilities. The policy emphasis has mainly been on providing preferential salaries and professional qualifications for those working in primary care settings (doc-RSRC-05; doc-RSRC-09; doc-RSRC-15; doc-RSRC-18; doc-RSRC-21) to attract and retain talent. Similar to infrastructure development, the central subsidy programmes for human resources have specifically targeted those facilities in poor areas; for example, one programme was paying around 10,000 hospital doctors yearly to work in approximately 3,500 township health centres (about one-tenth of all township health centres) (doc-HYB-07; doc-HYB-08; doc-HYB-09; doc-HYB-10; doc-HYB-11; doc-HYB-12). These centrally funded programmes were aimed at filling the gaps in meeting goals, such as having at least one doctor or GP in each township health centre (doc-HYB-09; doc-HYB-14). The scope and number of beneficiaries were thus limited.

Nationwide, the bianzhi system has continued to play a critical role. The system covers most employees in township and community health centres (a minority of staff are on contracts), providing them with privileges including tenured employment and a range of entitlements such as government-set salaries, pensions, medical insurance and other benefits. The salaries for those in bianzhi posts are covered by a mix of employer revenues (i.e. patients’ out-of-pocket and/or insurance payments) and government subsidies (doc-FIN-05; doc-FIN-08). In practice, increasing the number of bianzhi posts, which means more government funding for staff salaries, has been the most important government measure to increase staff numbers for township and community health centres. To guide this process, the central government issued guidelines for establishing bianzhi posts for community health facilities in 2006 and for township health centres in 2011 (doc-RSRC-08; doc-RSRC-22; doc-HYB-10, p. 295). For example, it is suggested that each community health centre have two to three bianzhi posts for GPs, one bianzhi post for a public health doctor and two to three bianzhi posts for nurses for every 10,000 people. After the issuance of these central guidelines, local governments reassessed their number of bianzhi posts, resulting in a moderate increase (doc-HYB-10, p. 295). Many local governments have also increased their financial commitment to cover the salaries of those employed in bianzhi posts.

Again, government measures have been effective in attracting new staff to township and community health centres, as shown by the rapid expansion in the number of staff and their educational qualifications (). For instance, in 2003, an average community health centre employed 34 staff members, with 14 of them being doctors. By 2018, the average community health centre had 49 staff, including 17 doctors. While the increases in human resources may seem relatively modest compared to physical resources (a,b), it is important to note a significant rise in the percentage of doctors holding a bachelor’s degree, which increased from only 14% to 48%. This increase partially reflects the rapid expansion of higher education in China during the same period.

Human resources (general practice)

While introduced to China in the late 1980s, the development of general practice was slow in the early phase. It was in 2001 that the government initially proposed that community health facilities should be staffed by a health workforce that is centred around GPs (doc-HREF-05). After the 2009 health reforms, the idea of developing a GP workforce to staff township health centres and village health stations appeared in national policy documents (doc-RSRC-18). Given the weak foundation of general practice in China, the goal was to significantly boost the number of GPs to achieve a target of two to three GPs for every 10,000 people (doc-HREF-11; doc-RSRC-25). This required increasing the number of GPs from around 60,000 in 2010 to 180,000 by 2015 and 300,000 by 2020 (doc-RSRC-18; doc-RSRC-21).

To reach these targets, the government initiated and organised large-scale short-term retraining programmes across the country and recruited doctors mainly from township and community health centres (doc-HYB-11, p. 237). Since the majority of health centres are public () and staff state employees, it was rather straightforward for the government to require doctors to attend and health centres to support the training by providing both training leave and financial support (doc-RSRC-19). The government successfully achieved its target, with 308,740 GPs in place by 2018, accounting for around one-third of the doctors working in township health centres and community health services (doc-HSY-05).

Human resources (village health stations)

Unlike township and community health centres, where most employees are in bianzhi posts, village health stations are predominantly staffed by self-employed ‘village doctors’, many of whom were previously known as barefoot doctors during the planned economy period. Despite being called doctors, these village doctors are actually paramedical workers who perform a limited range of healthcare functions in rural village settings. As the workforce is aging, ensuring village doctors’ presence in villages is critical for the accessibility of health care in rural areas and has attracted special government attention (doc-RSRC-17; doc-RSRC-20). Specifically, the central government aims to have at least one ‘doctor’ (the great majority of whom are village doctors) in each village health station, and one village health station ‘doctor’ for every 1,000 rural residents (doc-RSRC-20). Given the relatively complete network of village doctors in the early 2000s (), the goal of the policy was largely to retain the existing village doctor workforce.

To achieve this, one key measure has been township health centres directly running village health stations (doc-ADM-03), as it extends bianzhi privileges (i.e. government funding) to some of those working in village health stations. In 2018, around 31% of those working in village health stations were employed by township health centres (doc-HSY-05). Other key measures include standardising and increasing government subsidies to purchase EPHS from village health stations and introducing a general treatment fee for village doctors to charge their services and new government subsidies specifically for village health stations (doc-RSRC-20). Together, these measures are intended to provide more stable income streams for those working in village health stations. At the aggregate level, these government measures have been effective in retaining the village doctor workforce (), with an average of two doctors staffing each health station and each village health station doctor responsible for approximately 460 permanent rural residents in 2018 (doc-HSY-05).

Issues with human resources

Despite the expansion of human resources being in line with the government’s target, it is important to note that human resources are still recognised as the bottleneck for China’s development of primary care. First, the competence of primary care workers has consistently raised concerns about the quality of services. Ad hoc evidence reveals serious problems, which seem to be particularly alarming in villages. For example, a study of 198 village doctors in Shaanxi province indicated that only 25% of village doctors fully grasp the diagnosis criteria for hypertension (Zhao et al., Citation2016). Second, over the last two decades, hospitals have consistently offered higher salaries and better career prospects, resulting in a stronger expansion of human resources (doc-HSY-05). The issue of brain drain to hospitals remains unresolved, with primary care facilities often having relatively less qualified and experienced doctors. This unbalanced pattern perpetuates the perception that primary care settings are less attractive than hospitals. Third, the government has resorted to short training programmes to improve the competence of primary care workers. However, concerns have been raised regarding the sufficiency and quality of such programmes (Li et al., Citation2017). Studies indicate a mismatch between the training content and the needs of trainees, such as courses being too theoretical and trainers being specialists themselves and not familiar with general practice (Dai et al., Citation2013). As a result, the so-called GPs may not be sufficiently equipped to practice preventive and primary care, which in turn limits the quality of care provided.

Enhancements in service delivery attributes

First contact

As previously discussed, the lack of gatekeeping has been problematic primarily for urban areas. In the early 2000s, as the urban primary care sector entered a new development phase, the central government proposed piloting gatekeeping mechanisms for community health services in cities (doc-HREF-08). It is important to note that the government’s ambitions in this area have been relatively conservative. During the first two phases of healthcare reforms (2009–2015), the requirement remained a ‘pilot’ (doc-HREF-09; doc-HREF-10; doc-HREF-12). It was not until 2015, with the central government’s decision to promote the hierarchical diagnosis and treatment model (doc-HREF-13), that strengthening the first contact of primary care facilities became an important task. In 2017, the central government proposed developing medical health alliances to assist with hierarchical diagnosis (doc-HREF-15). These efforts have been exploratory, focusing on piloting and identifying potential models.

In essence, the government has heavily relied on expanding the urban primary care network to increase the utilisation of primary care facilities as the first point of contact for patients. When many small hospitals and township health centres were converted into community health centres in the 2000s and early 2010s, their patients became counted as users of urban primary care facilities. This was a significant factor in the increase in the proportion of patients using primary care facilities as their first contact in urban areas (). In addition to capacity building, the government has also attempted to incentivise the use of primary care facilities through financial means, such as offering price differentials and preferential reimbursement policies through public insurance programmes (doc-HREF-02; doc-HREF-03; doc-HREF-06; doc-HREF-09; doc-HREF-10; doc-HREF-12; doc-HREF-13). The assumption was that primary care facilities would offer lower prices and higher reimbursement rates, which would motivate patients to increase their use of primary care facilities.

Table 2. Distribution of first doctor–patient encounters (% of total) (2008, 2013 and 2018).

The progress in moving towards primary care gatekeeping has been disappointing thus far. According to the national health services surveys, the percentage of patients using primary care facilities as their first point of contact has decreased over time, from 73.7% in 2008 to 67.5% in 2018 (). This rate falls short of the government’s goal of maintaining it above 70% from 2017 (doc-HREF-13). Additionally, independent surveys conducted in large cities indicate that the majority of patients still prefer hospital-based services for first-contact care (Wu et al., Citation2017). This preference can be attributed to various factors, including the generally low level of trust patients have in primary care doctors, insufficient development of general practice to differentiate primary care from hospital services, and inadequate insurance reimbursement policies for outpatient services.

Comprehensiveness/provision of basic services (essential public health services)

As previously discussed, there is a strong emphasis on delivering basic services through primary care facilities, focusing on EPHS and basic medical services (doc-HREF-02). In 2009, the central government introduced a national list of EPHS (doc-EPHS-01) along with a comprehensive manual that provided detailed instructions for each item on the list (doc-EPHS-02). The government has adopted an incremental approach to expand the programme, with a focus on increasing the coverage of individual items (doc-EPHS-05; doc-EPHS-07; doc-EPHS-08; doc-EPHS-10; doc-EPHS-11; doc-EPHS-12; doc-EPHS-14) and allocating funds (doc-EPHS-06; doc-EPHS-13) each year. The programme was implemented at an impressive pace, and by 2015, coverage of EPHS was high across key items. All government targets, except for the management of patients with diabetes, were either reached or exceeded ().

Table 3. Targets and results for the delivery of essential public health services (2015).

However, the programme has faced complaints and criticisms. Among the primary care workforce, there was discontent regarding the inadequate level of government funding, resulting in poor incentives and a significant workload. In some cases, selective provision of services or the use of fake records has been observed to meet government requirements. Consequently, the reliability of the recorded health activities has been questioned, an issue that even the government acknowledges (HYB-09, pp. 40–46). While the extent of this problem at the national level is unclear, independent surveys conducted in certain localities provide some insight into this issue. For instance, in a survey conducted at a community health centre in Wenzhou, 500 health records of patients with hypertension and/or diabetes were randomly selected. Out of the sample, only 45.2% (226 out of 500) of the patients confirmed the accuracy of the information in their health records (Pan et al., Citation2016).

Relatedly and more critically, the quality of services has also raised concerns. In one nationally representative project that enrolled adults aged 35–75 years, it was found that only 44.7% of hypertensive patients were aware of their condition (Lu et al., Citation2017). Despite the increasing involvement of primary care facilities in managing the health of chronic patients, the results are still suboptimal. One national survey found that only 70% of hypertensive patients who sought care from primary care facilities were diagnosed, and only 6% had their blood pressure under control. Similarly, only 46% of diabetic patients knew about their condition, and only 3% had their blood glucose under control (Li et al., Citation2017). These data underscore significant gaps that still exist in the EPHS provision by primary care facilities.

Comprehensiveness/provision of basic services (basic medical services)

Similar to EPHS, the requirements for basic medical services used to be broad, only outlining general categories of services to be provided and suggesting that the exact range of services should align with the country’s social and economic development stage (doc-ADM-01; doc-ADM-02; doc-ADM-03; doc-HREF-05a). As the EPHS programme became more widely implemented, the government began to introduce more specific requirements for basic medical services. To encourage improvements, the delivery and quality of medical care have been incorporated into the performance evaluation of primary care facilities (doc-FIN-06a; doc-FIN-07a), affecting their funding (doc-FIN-06; doc-FIN-07). Moreover, additional performance evaluation tools have been developed to identify exemplary community and township health centres, which also consider the delivery and quality of medical services (doc-IMP-01a; doc-IMP-02a; doc-IMP-03a; doc-IMP-04a). Drawing from these experiences, the government introduced service capacity manuals for all health centres in 2018 (IMP-05a1; IMP-05a2) to guide and standardise the provision of basic medical services.

Despite the implementation of these government measures, there remains a limited understanding of their impacts on the provision of basic medical care and the extent to which primary care facilities meet government requirements according to the complex performance evaluations and manuals. Some evidence reveals that, in practice, quantity was prioritised over quality in the performance evaluations, thereby providing poor incentives for offering high-quality care (Li et al., Citation2017). A closely linked body of research suggested that the provision of medical care has been adversely impacted by the EPHS programme, resulting in a heavy workload for primary care workers and compromising their availability for medical care. Further, the implementation of the NEMP has unintentionally led to a decrease in the availability of medicines, further constraining the care provided.

Again, the academic literature reveals critical gaps in service quality, particularly concerning the overuse of antibiotics and injections in Chinese primary care settings. These practices not only exceed the levels recommended by the WHO but also pose health risks to patients (Li et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Other aspects of primary care quality have been more poorly characterised, but available evidence also points to deficiencies in diagnoses and other prescriptions (Li et al., Citation2020).

Coordination

Regarding the coordination role of primary care facilities, the Chinese government has emphasised the establishment of mutual referral mechanisms between community health services and hospitals (doc-HREF-01; doc-HREF-02; doc-HREF-03; doc-HREF-06). This effort aims to divert patients from overcrowded hospitals to primary care facilities. However, despite policy goals (doc-HREF-08) and the incorporation of coordination into various clinical protocols, the government’s policies lack specific and unified standards, processes, incentives, referral supervision and information on how medical insurance programmes reimburse referrals (Shen et al., Citation2018). Additionally, there is little incentive for service providers to refer patients to other facilities. The coordinating role is either absent (doc-FIN-07a1; doc-FIN-07a2) or accounts for only a small part (doc-FIN-06) of the government’s performance evaluation frameworks.

Despite some increases in referral volume, referrals remain rare due to insufficient referral standards and accompanying insurance policies, lack of incentives and regulatory mechanisms and the limited competence of professionals in primary care settings (Li et al., Citation2020; Shen et al., Citation2018).

Continuity

In early policy documents (e.g. doc-HREF-02), primary care facilities were described as providing continuous care to their patients, but this was mainly used to define primary care rather than as an important dimension for the government to enhance. It was only in 2016 that the government initiated the family practice contract programme (FPCS-01), which aims to encourage individuals to sign a service contract with a primary care doctor to enhance ongoing care in primary care facilities. Prior to 2016, perhaps the most significant measure adopted by the government that had the potential to enhance ongoing care was the standardisation of health records at primary care facilities (doc-EPHS-03). Primary care facilities are required to establish and maintain the health records of patients within their catchment area as an essential public health service. In theory, health records can help primary care facilities provide ongoing care by better tracking patients’ medical history and health situation. However, due to issues such as the fragmentation of the healthcare information system and the problem of fake records discussed previously, health records have not been effective in facilitating the delivery of ongoing care.

Limited evidence exists regarding the provision of ongoing care by primary care facilities in China. The family practice contract programme is still in its early stages, meaning there is a lack of contractual relationships between patients and primary care facilities. The implementation of the programme also faces challenges, such as inadequate informational continuity (Li et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the current state falls short of the ideal scenario of continuous care.

Discussion and conclusion

Throughout this review, one key aspect of Chinese policy and practice stands out as a persistent theme – the prevalence of the command economy logic. The Chinese primary care system has retained many features from the command economy period, and the government has further strengthened its administrative power in the primary care system since the early 2000s, mainly by introducing higher and more detailed requirements and instructions, combined with a substantial injection of government funds and enhanced control through complex performance evaluations. The implementation of various policies has been supported by a comprehensive public network staffed by a mostly state-employed workforce.

Overall, Chinese policy and practice have been highly effective in enhancing the inputs of primary care and achieving the government’s quantitative targets. Primary care facilities have become more spacious, better equipped and better staffed, and they have delivered a large number of EPHS free of charge to users, offered essential medicines at wholesale prices and provided many medical services at below-cost prices. However, these achievements have not yet been translated into a strong primary care system. The health delivery system in China has remained hospital centric, which contradicts the goal of making primary care facilities the cornerstone. In fact, hospitals have increasingly been used as the first point of contact and have outgrown primary care facilities in providing outpatient consultations. According to the criteria and standards used in the public health literature, which emphasise service delivery attributes and how the core functions of primary care have been fulfilled (Kringos et al., Citation2010; Veillard et al., Citation2017), the Chinese primary care facilities are still far from the ideal.

This study indicates that the performance gap in the Chinese primary care system needs to be contextualised in the Chinese government’s own agenda and development path. During the early 2000s, the primary care system in China was plagued by a lack of funding, low utilisation, inadequate staff qualifications and low patient satisfaction (Bhattacharyya et al., Citation2011). Consequently, the government focused on network building and restructured the rural healthcare system while establishing a new urban community health system. Once the network was complete and physical resources had significantly improved, the government began efforts to standardise basic services and make them available throughout the country. In the more recent phase, the government has shifted its focus to enhancing the service attributes of primary care facilities, particularly their roles in gatekeeping and offering ongoing care and referrals to hospital specialist services.

Moving forward, it is crucial for the Chinese government to make significant advancements in strengthening the service delivery attributes of primary care, particularly focusing on improving their quality, which should ultimately translate into improved health outcomes. This objective aligns with the World Bank and WHO’s (Citation2016) recommendations, which emphasise the importance of building high-quality and value-based service delivery as guidance for China’s ongoing healthcare reforms. Based on the review of national policies, this study reveals that the Chinese government has already made progress in this direction. However, it is important to acknowledge that these reforms face challenges stemming from deep-rooted legacies of the planned economy era. Systematic reforms are necessary to address the governance of healthcare institutions, bianzhi/personnel management and salary systems, and public financing and insurance systems. Given that these systems are fundamental institutional structures that span across multiple sectors alongside the health sector, the reforms required are inherently complex and challenging. In this regard, the spirit of intersectoral collaboration and coordinated efforts called for in the WHO’s (Citation2008) report on primary health care remains relevant and critical for achieving effective reforms in the Chinese primary care system.

Practically, valuable lessons can be drawn from international experience, including both strong performers among developed countries and other transition countries facing legacies from planned economy eras. Countries such as the UK, Denmark and the Netherlands have consistently demonstrated strong performances in international comparisons of primary care systems (Kringos et al., Citation2010). These countries offer valuable lessons on empowering and supporting GPs to play a pivotal role in coordinating care and delivering high-quality services. Additionally, among developed countries, the quality of care is safeguarded through robust professional standards and mandatory registration, necessitating ongoing retraining for continued registration. Stringent regulations also govern the reimbursement of diagnostics, treatments and medicines. By adopting and adapting these successful aspects, China’s primary care system has the potential to benefit significantly.

Other transition countries with similar goals to China have undertaken substantial efforts to reorient their hospital- and specialist-centric healthcare systems. These efforts have included introducing general practice as a distinct discipline, training existing health professionals to assume the role of GPs and transitioning from input-based budgeting to contract-based payments (Rechel & McKee, Citation2009). Actively learning from the experiences of these countries can provide valuable insights for China into effectively addressing the legacies of the planned economy era and further enhancing its primary care system.

This study has several limitations. First, while primary care systems are complex and encompass various aspects (Veillard et al., Citation2017), this study focused on the key aspects that have received significant attention from the Chinese government and public health literature to maintain clarity and focus. However, certain aspects, such as detailed medicine policies and health information technologies, were omitted from this analysis, and additional dimensions may warrant consideration. Second, the primary care system is intricately interconnected with other systems within the broader, complex healthcare landscape. In the Chinese context, hospitals play a notably important role as they directly compete with primary care facilities for general outpatient care. Due to the scope of this study, the discussion of these important interactions was limited, resulting in a less comprehensive understanding of their key dynamics and consequences for primary care development.

Finally, it is important to recognise that it is still early to evaluate the effectiveness of the Chinese government’s efforts to strengthen primary care. Significant changes in healthcare systems take time to materialise. The relatively low level of qualifications and skills among primary care facility employees cannot be improved quickly. As discussed in this article, many government initiatives aimed at strengthening primary care facilities were introduced not long ago. Considering the ongoing nature of these efforts, future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of these endeavours and track their progress. Longitudinal research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of government initiatives and shed light on the extent to which primary care in China evolves and improves over time. Such studies will help inform policy decisions and facilitate evidence-based interventions to strengthen primary care in China.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A complete list of the policy documents is provided in Appendix S1. The policy documents that appear in Appendix S1 are cited throughout as (doc-[code]).

2 Ethics clearance was approved by the Faculty of Arts Human Ethics Advisory Group at the University of Melbourne (Ethics ID: 1647404).

References

- Bhattacharyya, O., Yin, D., Wong, S. T., & Chen, B. (2011). Evolution of primary care in China 1997–2009. Health Policy, 100(2–3), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.11.005

- Dai, H., Fang, L., Malouin, R. A., Huang, L., Yokosawa, K. E., & Liu, G. (2013). Family medicine training in China. Family Medicine, 45(5), 341–344.

- Kringos, D. S., Boerma, W., Bourgueil, Y., Cartier, T., Hasvold, T., Hutchinson, A., Lember, M., Oleszczyk, M., Pavlic, D. R., Svab, I., Tedeschi, P., Wilson, A., Windak, A., Dedeu, T., & Wilm, S. (2010). The European primary care monitor: Structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Family Practice, 11(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-81

- Li, X., Krumholz, H. M., Yip, W., Cheng, K. K., de Maeseneer, J., Meng, Q., Mossialos, E., Li, C., Lu, J., Su, M., Zhang, Q., Xu, D. R., Li, L., Normand, S. T., Peto, R., Li, J., Wang, Z., Yan, H., Gao, R., … Hu, S. (2020). Quality of primary health care in China: Challenges and recommendations. The Lancet, 395(10239), 1802–1812. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30122-7

- Li, X., Lu, J., Hu, S., Cheng, K. K., de Maeseneer, J., Meng, Q., Mossialos, E., Xu, D. R., Yip, W., Zhang, H., Krumholz, H. M., Jiang, L., & Hu, S. (2017). The primary health-care system in China. The Lancet, 390(10112), 2584–2594. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4

- Liang, W., Wang, Y., Yang, X., Yan, Y., Yang, J., Guo, A., Chen, Q., Li, H., Guan, J., Li, J., Li, C., Gao, H., Li, C., Zhang, C., Jin, S., Liu, L., Yao, J., & Zhou, X. (2005). A survey on the status quo of Chinese community health service. Chinese General Practice, 8(9), 705–708.

- Liu, Y., Kong, Q., Yuan, S., & van de Klundert, J. (2018). Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13(8), e0201877.

- Lu, J., Lu, Y., Wang, X., Li, X., Linderman, G. C., Wu, C., Cheng, X., Mu, L., Zhang, H., Liu, J., Su, M., Zhao, H., Spatz, E. S., Spertus, J. A., Masoudi, F. A., Krumholz, H. M., & Jiang, L. (2017). Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: Data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study. Lancet, 390, 2549–2558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32478-9

- Pan, X., Liu, M., Ye, Y., Wang, M., & Chen, D. (2016). Authenticity of electronic health records of community chronic disease patients. Chinese General Practice, 19(4), 382–385.

- Rechel, B., & McKee, M. (2009). Health reform in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Lancet, 374(9696), 1186–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61334-9

- Roemer, M. I. (1991). National health systems of the world: Volume I. Oxford University Press.

- Shen, Y., Huang, W., Ji, S., Yu, J., & Li, M. (2018). Efficacy, problems and current status of two-way referral from 1997 to 2017 in China: A systematic review. Chinese General Practice, 21(29), 3604–3610.

- Starfield, B. (1998). Primary care: Balancing health needs, services, and technology. Oxford University Press.

- Tan, X., & Yu, L. (2022). Has recentralisation improved equality? Primary care infrastructure development in China. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 9(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.346

- Veillard, J., Cowling, K., Bitton, A., Ratcliffe, H., Kimball, M., Barkley, S., Mercereau, L., Wong, E., Taylor, C., Hirschhorn, L. R., & Wang, H. (2017). Better measurement for performance improvement in low- and middle-income countries: The primary health care performance initiative (PHCPI) experience of conceptual framework development and indicator selection. The Milbank Quarterly, 95(4), 836–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12301

- World Bank, & World Health Organization. (2016). Deepening health reform in China: Building high-quality and value-based service delivery. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/800911469159433307/Deepening-health-reform-in-China-building-high-quality-and-value-based-service-delivery-policy-summary.

- World Health Organization. (2008). The world health report 2008: Primary health care now more than ever. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43949.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. (2015). People’s Republic of China health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 5(7), 1–217.

- Wu, D., Lam, T. P., Lam, K. F., Zhou, X. D., & Sun, K. S. (2017). Health reforms in China: The public’s choices for first-contact care in urban areas. Family Practice, 34(2), 194–200.

- Zhang, M., Ding, X., & Gao, Y. (2016). An investigation of medical and public health services of community health centers. Chinese Health Service Management, 2016(9), 654–656.

- Zhao, Y., Li, Q., Dang, S., Chen, Y., Cao, L., Yang, R., & Yan, H. (2016). Team structure and hypertension treatment and prevention ability of village doctors in rural areas of Hanzhong, Shaanxi province. Chinese General Practice, 19(16), 1955–1959.