ABSTRACT

Climate change is an important driver of migration, but little research exists on whether migrant communities in the U.S. identify climate change-related factors as reasons for migrating. In 2021, we conducted a multidisciplinary, collaborative project to better understand the nexus of climate change and immigrant health in the Atlanta area. This paper presents one arm of this collaboration that explored both the role of climate change in decisions to immigrate to Georgia and the ways that climate change intersects with other possible drivers of migration. First generation migrants from Latin America were recruited primarily through CPACS Cosmo Health Center and were invited to participate in an intake survey and an in-depth interview. Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics and thematic analysis. Findings suggest that while participants may not have explicitly identified climate change as a primary reason for migration, in both surveys and in-depth interviews, participants reported multiple and intersecting social, economic, political, and environmental factors that are directly or indirectly influenced by climate change and that are involved in their decisions to migrate. The narratives that emerged from in-depth interviews further contextualised survey data and elucidated the complex nexus of climate change, migration, and health.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, the number of people migrating from Latin America to the United States has been increasing for a variety of reasons, including conflict, economic stress and climate change (Raleigh, Citation2011; Ridde, Citation2018; Semenza & Ebi, Citation2019; Wenden, Citation2016). While political and socioeconomic factors have long been considered the biggest drivers for migration, climate change is increasingly recognised as a significant contributing factor (Semenza & Ebi, Citation2019; Wenden, Citation2016). The climate crisis is expected to have an enormous impact on migration this century, and migration can be understood as an adaptive response to climate change (Twinomuhangi et al., Citation2023; Welch-Devine et al., Citation2020). Estimates of the number of people who will be displaced by climate change vary. In 2020, the United Nations estimated that there were 281 million international migrants and 763 million internal migrants (UN-DESA, Citation2020), with at least 1.2 billion people at risk for displacement by 2050 (IEP, Citation2020). The International Organisation of Migration suggests the number of ‘environmental migrants’ by 2050 will range from 25 million to 1 billion ‘moving either within their countries or across borders, on a permanent or temporary basis, with 200 million being the most widely cited estimate’ (IOM, Citation2023, online). The Institute for Economics and Peace projected that that the number of people living in countries facing ‘catastrophic ecological threats’ by 2050 will be 3.4 billion (Citation2022, p. 4). In the pilot study discussed in this paper, a multidisciplinary team of researchers explores the nexus of climate change, health, and migration for first generation migrants from Latin America to the metropolitan Atlanta area with the aim to learn more about the ways in which climate change interacted with migration decisions, particularly as they relate to health and well-being.

To date, little research exists on the extent to which people migrating from Latin America to the U.S. identify climate change-related factors that impact health as either primary or underlying motivations for migrating (Ridde, Citation2018; Sellers et al., Citation2019). There are several studies of perceptions of climate change in Latin America, but they do not focus on international migration. For example, Fierros-González and López-Feldman (Citation2021) published a review of 21 studies (published between 2000 and 2020) on farmers’ perception of climate change from Latin America; they noted many factors that seem to impact understanding and perception of climate change (including the severity of impact of drought in different regions, age, gender, access to information about weather changes, and education). Forero et al. (Citation2014) did a systematic review of the literature (published between 1997 and 2012) on perceptions of climate change in Latin America. Whilemigration was not a focus of their review, two studies identified climate change as an underlying driver of increased poverty leading to family instability, which in turn, prompted rural to urban migration (de los Ríos & Almeida, Citation2010; Treulen, Citation2008).

Integrating in-depth interviews with quantitative survey data, as we have done in this study, can reveal nuances of how daily life, health, and well-being in communities of origin contribute to decision-making related to migration. Whitmarsh and Capstick (Citation2018) noted the importance of ethnography and qualitative data collection in understanding perceptions of climate change. Parsons and Nielsen (Citation2021, p. 972) similarly called for researchers to decentre ‘the question of fit between physical data and human perceptions of climate change’, as perceptions of climate change, which are ‘subjectively attuned to social and livelihoods factors’; this decentring can help us understand the nuances of migration decision-making.

There are several models that are useful for understanding the complex influence of climate change on migration. McMichael (Citation2015) and Rigaud et al. (Citation2018) distinguish between ‘rapid-onset’ and ‘slow-onset’ migration. Rapid-onset migration, as the name suggests, is due to sudden climate shocks, like extreme weather events, e.g. wildfires and hurricanes (McMichael, Citation2015; Rigaud et al., Citation2018). In contrast, slow-onset migration is associated with long-term climatic stressors such as water shortages, droughts, and rising sea levels (Raleigh, Citation2011; Ridde, Citation2018; Sellers et al., Citation2019; Semenza & Ebi, Citation2019). Each form of climate-related migration is also embedded within socioeconomic and political landscapes that further define the migration experience (Sellers et al., Citation2019) Twinomuhangi, et al. (Citation2023, p. 595), illustrate the complexities of climate change and migration decisions in rural Uganda, where

slow-onset processes, such as rising temperatures, desertification and environmental degradation, as well as sudden-onset events, such as storms, floods and landslides, have become more frequent and often result in livelihood hardship such as crop failure, loss of livestock, food insecurity, water scarcity, disease outbreaks and resource conflicts that can be linked to households and individuals’ decisions to migrate temporarily or permanently, while others are displaced.

Morris (Citation2022) discusses how these landscapes affect perception of climate change. In fieldwork in the Pacific Island nation of Nauru, she found that her interlocutors were aware of climate change and could articulate dramatic changes in climate over time, but they resisted the label of ‘climate refugee’ (or potential future climate refugee), which she ties to the historical and contemporary situations of colonial and capitalist extractivism in this part of the world. In a recent article, Jacobsen (Citation2023:, p. 97) notes that ‘in the past five years, multilateral organisations … have begun to promote climate migration as an emerging global priority … no state or international organisation recognises the concept of ‘climate refugees’. However, this concept can be useful in understanding the needs of people in climate-vulnerable settings where structural inequalities also affect health and well-being.

Health risks and vulnerabilities add another layer of complexity to the nexus of climate change and migration (Schwerdtle et al., Citation2020). Climate-sensitive health exposure risks, from extreme heat to infectious diseases, are present pre-migration and at every stage of the migration experience. In addition to health challenges like malnutrition and diarrheal diseases due to food and water insecurity (Schwerdtle et al., Citation2020; Sellers et al., Citation2019), climate change is associated with the emergence or reemergence of certain infectious diseases. Some of these diseases, once under control, are now endemic again or have emerged in new areas with limited resources for surveillance, prevention, and intervention (Booth, Citation2018; Carlson et al., Citation2022; Castro et al., Citation2019; McMichael, Citation2015; Short et al., Citation2017). Butler et al.’s (Citation2022) discussion of primary, secondary, and tertiary effects of climate change helps to pull together how climate change-related events can provide a backdrop for a number of other problems, including many that are health-related, that underlie decisions to migrate.

Health risks, including those due to climate-related environmental exposures, continue upon resettlement. Migrant workers have a greater risk of heat-related illness and death during extreme heat events that are intensifying in our changing climate (Salas et al., Citation2019). Physicians may lack awareness of environmental exposure risk factors for patients who have migrated to the U.S. as well as of infectious and chronic disease patterns from migrants’ country of origin. These knowledge gaps can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or improper treatment for these diseases (Hotez et al., Citation2008; Short et al., Citation2017).

The stress involved at every stage of the migration process can also result in mental health sequelae (Nolas et al., Citation2020). In some cases, climate-related health vulnerabilities are further complicated by linguistic isolation, poor socioeconomic conditions commonly experienced by migrants in host communities (e.g. substandard housing, low wages, occupational exposure hazards, limited access to nutritional foods), and limited access to healthcare (Caballo et al., Citation2008), all of which might lead to health deterioration among international migrants (Malmusi et al., Citation2010). Anti-immigrant sentiment and xenophobia in the host country can also contribute to delays in seeking treatment, as some migrants fear being detained or deported (Cleaveland & Ihara, Citation2012; Kalengayi et al., Citation2012; Poorman, Citation2017), which again can further complicate health outcomes that might be related to climate change. The combination of these factors places migrants at increased risk for poor health and negative health outcomes related to climate change.

Drawing upon subsets of data collected in a mixed-methods parent, multi-disciplinary pilot study, this paper examines the perceptions and experiences of the climate change-migration-health nexus among adult first generation migrants from Latin America to the Atlanta metropolitan-area; identifies factors that contributed to migration decisions; and assesses the consideration of climate change amongst these reasons using both qualitative and quantitative data. We identified climate change-related vulnerabilities that may play a part in decision-making related to migration, though these vulnerabilities were not always stated or articulated as climate change by participants in the study.

Methods

Study design and population

Due to the heterogenous manifestations of the climate change-migration-health nexus, researchers have called for multidisciplinary methodologies with an emphasis on qualitative data (Barnes et al., Citation2013; Schwerdtle et al., Citation2020). Alongside a growing body of literature answering this call, we implemented a multi-institutional and multi-disciplinary pilot study to examine the climate change-migration-health nexus in the state of Georgia. Our study team included experts in the fields of immigrant/migrant health, anthropology, infectious disease, planetary health, and environmental sciences, as well as community partners from a local Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), the CPACS Cosmo Health Center, which serves the immigrant population of metro-Atlanta.

Between May and December 2021, individuals were recruited to participate in this pilot, observational study in the Atlanta-metropolitan area, where 48% of those born in another country identify as having been born in Latin America (Migration Policy Institute 2019). Individuals were recruited using a convenience sampling approach during visits to the Cosmo Health Center (CHC) and the associated Center for Pan Asian Community Services (CPACS) as well as through other local neighbourhood organisations. Study team members not affiliated with the clinic itself were responsible for recruiting participants, to reduce the risk of feelings of coercion amongst regular patients who were potential participants in the study. Individuals who had migrated from Latin America to Georgia (and who resided in the Atlanta metropolitan area at the time of the study) were eligible to participate in the study. For the parent study, which involved infectious disease and nutritional screening (involving blood tests, fecal samples, and skin exams), the results of which will be reported in other publications, and an initial survey, participants had to be at least 3 years old; legal guardians provided informed consent for children aged between 3 and 5, and assent was required for children ages 6 years and older. Individuals were eligible to participate in an in-depth interview (IDI) if they were 18 and older and otherwise eligible for the parent study as noted above. All study materials, including recruitment materials, consent forms, initial surveys, and IDIs, were prepared in participants’ preferred language (i.e. English, Spanish, or Portuguese). In addition, we prepared handouts to give out to participants in the study – one with information about the health screening and another with local community resources related to health, housing, education, food security, job training, and utilities assistance.

Eligible participants were given an initial survey at recruitment. The initial survey included 38 questions that were formatted as short answer, multiple choice, select-all-that apply, and Y/N questions. For this paper, we include the self-reported socio-demographic variables (age, gender identity, and country of birth), categorical variables on reasons for moving to the U.S., and binary variables on perceived changes to the land, climate, or environment prior to migration. In one question, we asked, ‘What were the reasons you decided to move to the U.S.? (Check all that apply). Some reasons may be about the country or countries where you lived. Others could be reasons you came to the U.S.’, and this was followed by 24 choices, including ‘climate change’ but also slow- and rapid-onset climate stressors (such as droughts and floods) and many possible push/pull factors, like violence, work, poverty, and education. Participants could also give ‘other reasons’ that the interviewer would write in.

A subset of individuals was invited to complete an in-depth open-ended interview. The IDI guide created by the study team included 31 open-ended questions (including some with follow-up questions depending on the answers) exploring participants’ baseline understanding of climate change; perceived changes to the climate or environment in participant’s community of origin; and how, if present, these changes may have impacted the work, health, and well-being of the community. There were also questions about participants’ migration experiences, including factors that influenced the migration decision, who made the decision to migrate, and what resources were needed to make an international move. We attempted to avoid suggestive questions about whether climate change was a factor in the decision to migrate, but instead asked, ‘What influenced your decision to leave?’ with additional probes, depending on what response this question elicited. While not discussed in this paper, post-migration experiences were also explored in the IDI, ranging from topics of work, health issues, access to community resources, and resilience.

IDIs were carried out via in person meetings at the Cosmo Health Center or telephone calls, depending on participants’ choices. Interviews were conducted by members of the research team who were fluent in the participant’s language, taking between 20 minutes and one hour with real-time note taking. Interview responses were transcribed and translated by the team members. Participants received compensation in the form of gift cards for participation in each part of the study.

In light of the potential risks related to immigration status of participants, no questions were asked regarding legal status, documentation, or home address (Jach et al., Citation2020). Some participants chose to disclose information about documentation status in IDIs, however. All participant data were de-identified and participants were assigned pseudonyms, inspired by lists of common names in participants’ countries of origin. Approval for this study was granted by Approval for this study was granted by Emory University’s Institutional Review Board (Study00002165) and an External Reliance Agreement from Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board (Study H21439).

Analysis

We utilised thematic analysis to identify themes that emerged from the IDI data. Interview transcripts were uploaded to NVivo, an ethnographic analysis software, which assisted in systematic coding of the data into overarching themes. This created a ‘style of inquiry’ that did not pre-identify themes or outline hypotheses, allowing ‘unanticipated findings’ to emerge from that were then contextualised ‘with existing concepts and knowledge’ to understand the triad explored in this paper (Timonen et al., Citation2018, p. 6). Components of the initial survey data related to migration motivations and perceived land changes were analyzed using descriptive statistics via Excel.

Results

Demographics

Between May 2021 and January 2022, 57 people completed the initial survey, of whom 81% (46) identified as cisgender women and 91% (52) were 18 years old and up. Ten countries and one U.S. territory in Latin AmericaFootnote1 were represented, of which El Salvador and Mexico represented the majority at 33% (19) and 23% (13) respectively. Guatemala and Honduras represented the following two most frequently mentioned countries of origin at 12% (7) and 11% (6), respectively. Forty-four percent (25) of participants had been in the U.S.Footnote2 for more than 15 years, though nearly a quarter (23%) had been in the U.S. for less than five years.

Twenty-three participants completed qualitative IDIs. Most immigrated from El Salvador (11) and Mexico (8) with one each from Honduras, Peru, Brazil, and Paraguay. All identified as cisgender with 21 women and two men whose ages ranged from 20 to 57 years old. Dates of arrival to the U.S. ranged from 2020 to 1970, though it should be noted that the 1970 date was an outlier, with the next earliest arrival date being 1988; the majority of IDI participants (61%, n = 14) had arrived in 2000 or later. More than half (15) migrated directly to the Atlanta-metro area, with the remaining seven spending time in one or more locations (i.e. Texas, California, New York, Chicago, Canada, and North Carolina). Interview themes are outlined below and summarised in .

Table 1. Qualitative in-depth interview themes exploring the intersection of climate change, migration, and health and migration motivations.

Initial survey

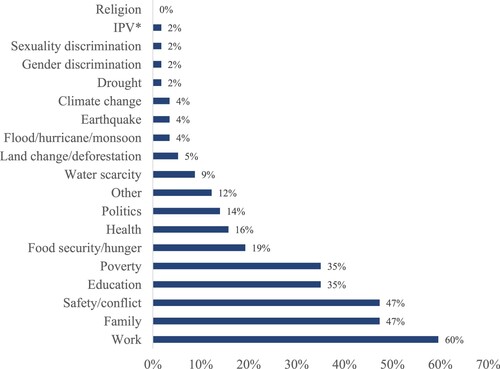

On the quantitative, initial survey, direct climate change and environmental drivers (i.e. flood/hurricane/monsoons, land change/deforestation, drought, earthquakes, and specifically climate change) were identified infrequently (5 participants in total) as reasons for migration. Similarly, a small percentage (4%) in the initial survey chose the term ‘climate change’ as a reason for migration. Despite this, participants chose a number of climate-related issues and other factors related to social determinants of health that could be exacerbated by climate change (). For example, 74% (42) participants noted changes to the land overtime, and 33% (19) believed these changes impacted their life and community of origin. Of the 57 participants for whom we had completed surveys by January 2022, the most frequent reasons for migrating included work, 60% (34), family, 47% (27), and safety, 47% (27), followed by education and poverty, on par at 35% (20) (). Those who cited ‘other’ (12%) expanded with reasons including: tourism, family conflict, marriage, love, and ‘better future for family’, some of which highlight how familial connections were strong impetuses for migration.

The multi-causal nature of environment and climate-induced migration: Climate change and structural determinants of health in communities of origin

The theme of climate change compounding and complicating structural determinants of health as drivers for migration emerged from the data collected for this research, with IDIs providing details that complemented initial survey answers. Participants discussed climate-related events in their communities in their responses to asking them to define climate change, and when asked to go into more detail about climate, the environment, and daily life in their communities of origin, we were able to collect additional information. The most frequently cited climate-related events reported were heavy rains and floods, hurricanes, droughts, and rising temperatures, with a few references to air and environmental pollution. While heavy rains and floods have always been a part of life in the regions of origin for the people in this study, the intensification of these events over time is well-documented, and it is possible to link participant narratives of perceived climate change to climate data for their regions of origin.

Participants associated climate-related events with loss of livelihoods, risks for infectious diseases, food and water insecurity, and pollution and toxic exposures. Violence in people’s communities of origin was another common theme, especially for participants from El Salvador, and this constitutes a public health risk that intersects with several other social determinants of health. Although we have separated the following examples into themes, each theme intersects and overlaps with others. For example, a participant might have focused on job loss related to flooding or drought, but their story also contains a mention of health issues related to these circumstances.

Understanding and articulating climate change and its impacts

Thirteen (57%) of the 23 participants in the IDIs gave an explanation of climate change that aligns well with the scientific definition, including an acknowledgement of human-induced contributions to climate change. Two said they had never heard of climate change, and four said they heard of it but ‘couldn’t really explain it’ or ‘define it’. Four participants defined climate change as regular seasonal changes as opposed to progressive changes over time, or they talked about individual natural disasters such as a hurricane or earthquake when asked about climate change.

Among the participants who could not define climate change or who described it as seasonal changes, some still talked about changes in the climate in their communities of origin over time and articulated the ways in which climate affected aspects of daily life, health, well-being, and job opportunities. Of the four participants who described climate change as seasonal changes, two had arrived in the U.S. over 30 years ago and so may not have noticed significant changes in climate over time. In our IDIs, we found that in separating participants into three categories for time of migration to the U.S. (1970–2000, 2001–2010, and 2011–2020), participants across these time frames of migration mentioned flooding, drought, and increases in both heat and flooding over time, though only participants who came to the U.S. after the year 2000 mentioned hurricanes specifically as disruptive climate-related events. Length of time in the U.S. did not correspond to a lack of understanding of climate change, as some participants had learned more about it in the U.S. or had heard from friends and family members about changes in their communities over time, however. For example, Camila, who came to the U.S. from Mexico in 1991 as a young child, mentioned going back for a visit as a teenager and subsequently talking to her sister who still lives there and has noticed ‘more rain, flooding, hurricanes’ over time. Francisco came to the U.S. from Brazil in 2013, and though he said he did notice evidence of climate change when he was a child, he told us, ‘Now I hear different things and things I was not familiar with, like more snow where there wasn’t any before … and droughts (in São Paulo)’. Sofia came to the U.S. in 1994. She travels back often. ‘I didn’t notice it so much when I was living there’, she shared, ‘but I go back every three years or so and it’s getting dryer’. She continued, ‘my grandfather used to have his own irrigation system and used his own well, but now they’ve had to dig another well because there’s not enough water’. This affected their drinking water, having to create new sources.

For those who provided a robust definition of climate change, the most frequent theme that emerged was the understanding that human actions and misuse of resources are a main cause of climate change. Josefina arrived in the U.S. less than a decade ago from an urban area in central Mexico, where she worked selling snow cones (nieve artesanal). She said that ‘each year it was a little hotter, a little colder each season … more extreme every year’, and she tied this to human activity: ‘We’re destroying the environment with garbage, things that can’t be recycled, ruining the environment, dumping into the ocean’. Adriana, who came to the U.S. in 2001 from a city in northeastern Mexico, characterised her home city as ‘very dry, more or less like a desert’. She similarly highlighted anthropogenic influence stating, the earth is getting hotter from misuse, and she specified the increasing ‘lack of water from regular droughts’ in this region. Isabel, from the same region, arrived in the U.S. in 2019 and linked climate change to human health by noting the connection to the food supply:

Basically, it’s when the climate was [a certain way], but human actions against the environment and against the world [have caused problems/changes]; it affects the plants and the ocean, so that fish are contaminated.

Other participants who referred to changes in temperatures over time, such as Luisa from Mexico and Ana from El Salvador, talked about the ‘heat becom[ing] unbearable’ and ‘dangerous levels of warming’, respectively. The most frequently mentioned downstream effects of climate change were associated with ‘glaciers’, ‘plant life’, and ‘oceans’. The theme of climate and environmental changes over time was most pronounced in participants’ mention of drought and temperature. Three other participants from El Salvador also offered poignant examples of drought and temperature changes over time. Carolina, like Isabel, shared how this ‘affected the agricultural harvests (cosechas) because there’s less rain’. Gabriela explained it was not just drought but rather, the ‘weather was warmer and warmer … in the winter [it] rains but less and less’, made worse by the ‘country deforesting itself’; it was apparent that Anita herself understood the relationship of climate change, deforestation, and drought. Anita agreed that when there was drought, farmers ‘would lose everything’. She continued, reminiscing on how ‘there used to be vientos de octubre (winds of October)’ This phrase is common in El Salvador to refer to the strong winds that indicate the transition to fall and cooler temperatures (Chincilla, Citation2023); the vientos de octubre are also frequently referenced in Salvadoran art and literature as well. Anita told us, ‘Those cold months are no longer there’, and she can no longer ‘feel the difference in the seasons’.

Disrupted livelihoods: Work, health, and climate

Daniela was in her late 20s when we interviewed her in 2021, and she arrived in the Atlanta area in 2018. She recalled heavy rains in El Salvador, sharing: ‘Rain would fill the lake, come into the houses and schools in the summer. We’d evacuate to the church. Rescue workers would come to help’. She also talked about how flooding affected her and her husband’s job before they came to the U.S.; they worked as guards for aquaculture ponds, ‘keeping people from stealing the shrimp’. When it would flood, ‘there was no work until the tides went down’. Although she saw these floods as happening throughout her lifetime, she was arguably experiencing the documented effects of climate change in this region that began before she was born. Daniela’s narrative, in describing how flooding affected this particular industry and thus employment, suggests one way in which climate change intersects with economic opportunities, a push factor for migration.

Maria, from Honduras, who arrived in the U.S. in 2015, mentioned heavy rains in the context of Hurricane Mitch in 1998. To date, Hurricane Mitch represents one of the deadliest hurricanes in the Atlantic that led to nearly 7000 deaths and 70,000 homes affected in Honduras alone (PAHO, Citation1998). She recalls that while it ‘personally did not affect [her] very much … many people lost their houses, water sources … crops … lives, due to the flooding’.

Isabel moved to the U.S. in 2019 citing better job opportunities and her own health issues as reasons for migrating. She made explicit connections among working conditions, health, illness, climate change. She experienced severe effects of drought in her hometown in northeastern Mexico, noticing temperatures getting a littler warmer each year. She told us that she was ‘sick working in Mexico’. She described how both heat and water quality affected her own health and that of others in her community:

It could get really hot … we could easily get dehydrated … There were a lot of illnesses [in my community] … I have an autoimmune disorder. Cancers were common; my neighbor had skin cancer. Stomach bacteria was an issue for many people in the community. I had a long treatment regimen for stomach bacteria, and then it came

back … My grandmother didn’t have potable water, no paving. The river had mosquitos, flies (rio de sancudo, rio de moscas) … I sold tacos for a while; [because of my auto-immune disorder it] was hard to work in a street market/outdoor market (mercado rodante).

Infectious disease and climate-related events

We asked participants to talk specifically about health problems in their communities of origins. Again, in this section of the IDI, participants drew links between infectious disease and flooding and drought events. Daniela, from El Salvador, perceived that flooding affected people’s risk for infectious diseases:

[w]ith flooding, there were more diseases – rabies, dengue, typhoid, which 3 of us got; my younger son got chikungunya, [and possibly Avian flu, from her description]. And now Coronavirus (is a problem there).

Similar links made by participants between infectious diseases and environmental factors – drought and flooding – were pervasive. Dengue and chikungunya were the most frequently mentioned health issues by participants in IDIs, with 5 total mentions of dengue and 4 of chikungunya. Gabriela also mentioned the presence of ‘typhoid fever, cholera and other stomach problems like diarrhea’.

Adriana, from central Mexico, gave ‘work’ and ‘following her husband’ as her stated reasons for migrating to the Atlanta-area in 2001, but she also linked the droughts she lived through in central Mexico with numerous health issues as well as water security and safety concerns. Wells ‘would sometimes become contaminated with dead animals’, and she said she got polio as a child from contaminated wells.

Food and water insecurity

Beyond the impact to livelihoods and infectious diseases, participants expanded on the links between climate impacts like drought and flooding and basic determinants of health – food and water security. Most participants described ‘pull’ factors as their primary reasons for migration, but they gave vivid accounts of food and water insecurity as stressors influencing their decisions. Some talked more generally about lack of resources – for example, Alejandra, who came to the U.S. from western Mexico in the late 1990s, said she experienced hunger throughout her childhood. She did not tie this to climate change in her interview, but she did discuss her memories of flooding:

What I remember [during floods] is that the river would overflow [levee would break], and sometimes we had to leave running (nosotros salimos corriendo); houses would flood, cars floating – there would be turtles everywhere.

Gabriela, from El Salvador, who came to the U.S. in 2012, described the effects of flooding on food availability: ‘When there was lots of rain, people lost their crops, and there was less food to purchase’. Yesenia, also from El Salvador and who arrived in 2010, similarly associated rising temperature and rainfall with food and water insecurity. Her stated reason for immigration (when she was pregnant) was to give her child a better opportunity at life, but she echoed stressors of other participants: ‘When there is more warm weather, there is rain, less food, and water shortage in all places’.

Daniela, from El Salvador, ultimately decided to move to the U.S. to join her husband, making the dangerous border crossing journey with her son, who was just a toddler at the time. She also cited food and economic insecurity as big factors in her decision to migrate: ‘In El Salvador, we could only afford to go for groceries every 8 days’; this could also be related to her story mentioned above, of the ways in which regular flooding contributed to job insecurity in aquaculture.

Pollution and toxic exposures

Some participants explicitly linked pollution and toxin exposures, worsened by environmental degradation, to health. Monica, from northeast El Salvador, mentioned contaminants in the wells from fertiliser runoff:

The water supply was from wells; fertilizers from agriculture were contaminating wells and causing health problems, kidney problems in kids from contaminants from the poison wells.

When asked what health concerns were most common in their communities of origin, Lorena, from a city on the Peruvian coast, said ‘asthma’. Although she believed the rise in asthma was due to the ‘humidity increased in the city/port’, she separately recounted ‘there’s a lot of pollution’. She continued: ‘The sky isn’t clear’ and it has ‘affected my family members who had asthma’. Yesinia, who moved to the Atlanta area in 2010 from El Salvador also acknowledged the growing presence of ‘air pollution, warmer weather’ in her community of origin. She said these did not impact her health or migration decision, though later in the conversation when discussing health challenges in her community, she mentioned that ‘respiratory problems’ were a common concern in her community.

Safety and violence

Migration decisions also encompassed the public health issues of safety and violence. This was particularly poignant for participants from El Salvador. When asked if Carolina would ever return to El Salvador, she shared, ‘there are security issues and safety risks. You could start a business there and be robbed or risk extortion’. Sherlyn moved to the Atlanta area from El Salvador during the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, and she mentioned gang violence as the reason that finally compelled her to move.

Daniela and Anita highlighted the disproportionate impact that violence had on males in the family. Anita shared how her dad ‘had been threatened by gang members’. Coming to the U.S. ‘was an all or nothing situation for the family’. Even though her dad was ‘given political asylum’, she did not want to come because she was ‘close to graduating college’. Beyond her dad, she shared how the war and insecurity affected the boys in El Salvador in particular. She said, ‘many boys were being kidnapped’. Daniela’s husband also made the initial move because of concerns about gang activity. She said that he was not involved directly in a gang: ‘He didn’t smoke or drink and never did anything wrong, but they were suspicious of him’. Participants who talked about violence in their communities of origin did not make a direct connection between local conflict and climate change, but climate change and climate-related events were discussed by them in other parts of their interviews.

Discussion

Our findings show the many ways in which a changing climate has affected and continues to affect participants’ communities of origin in Latin America. In terms of the original research question of whether climate change, particularly as it impacted health and well-being, served as or was perceived to be a driver of migration from Latin American to Georgia, we found that there was not a straightforward answer. In presenting our results above, we have separated examples of the interaction of climate change with structural determinants of health in terms of how they were described by people who participated in this study, but we were struck how many participant narratives illustrated the complexities of the relationship between climate change and living conditions that could in turn impact migration decisions long-term. Re-connecting the pieces of their stories is another way to illustrate how climate change may be interwoven into other experiences of participants in their countries of origin. Daniela’s family’s story demonstrates how multiple factors affect the migration experience from El Salvador, with climate change being part of the picture. She talked about flooding as it relates to agricultural job opportunities, violence and conflict that prompted her husband’s migration to the U.S., and food an economic insecurity that was the push factor she cited in her own decision to migrate. Isabel linked her migration decision both to a health issue that was exacerbated by climate change and to better job opportunities in the U.S. In just a short description of her life in Mexico, she illustrated the complex factors that impacted her health and that of others in the community, including poverty, problems with infrastructure and access to clean water, lack of access to healthcare, and working outdoors in increasingly hot conditions.

This study revealed the ways in which social determinants of health (such as poverty, conflict, lack of sufficient income or job opportunities, and food insecurity), which were the most common stated reasons for migration, intersected with climate-related issues and environmental degradation. Through stark accounts of rising temperatures, floods, drought, pollution, climate-associated loss of lives and livelihoods, food and water insecurity, and health challenges, our findings indicate that climate and environmental changes played a role in the multifactorial decision to migrate.

The difference between overt attribution of climate change as a driver of migration and lived experience may be reflected in participants’ overall conceptualisation of climate change. As evidenced by the interviews, articulation of climate change was grounded in understanding of anthropogenic contribution to climate change with implications for rising temperatures and their effects on the environment. The explicit connections to human health that participants made were in their discussions of pollution, resources shortages, chronic illness, and infections. Our findings are consistent with prior literature noting that while challenges to human health and challenges from climate change are both increasing and connected, there remains a lag in how individuals frame climate change as a human health problem (Watts et al., Citation2019).

Qualitative interviews identified and fleshed out social determinants of health factors that are directly or indirectly influenced by climate change in their decisions to migrate to the U.S., providing greater insight into the complex relationship between climate change, migration, and health. Further appreciating the value of qualitative data at this nexus, participants’ ‘place-based knowledge’ (Barnes et al., Citation2013, p. 541) was not only valuable for local contextualisation of climate drivers but also consistent with findings in the literature. Participants clearly articulated observations of increased drought, coupled with intermittent heavy rainfalls leading to extreme floods. Participants mentioned regionally-verifiable climate changes, such as the diminishing of the vientos de octubre in El Salvador. Descriptions of drought from participants from Mexico and El Salvador of drought may represent the lived experience of the Central America ‘Dry Corridor’ (Hotez et al., Citation2020). The Dry Corridor is the consequence of a five-year drought attributed to climate change that reaches across southern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (Hotez et al., Citation2020). This drought has led to widespread deleterious effects on agricultural production, in turn leading to food and water insecurity and thereby rural-to-urban migration and displacement. It is also thought to have led to changes in illegal drug trade routes, expanding to the ‘Northern Triangle’ (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) (Raleigh, Citation2011). Compounded with a fraught historical and sociopolitical landscape, the drought has contributed to a rise in conflict, violence and insecurity (Hotez et al., Citation2020). Argomedo (Citation2020, p. 81) noted, ‘climate change is injecting more scarcity in the region, such as an increased difficulty in sustainable farming, which will create more conflict’. Bowles et al. (Citation2015) have also discussed the role of climate change in exacerbating conflict which is in turn related to public health. Climate change has been linked to increases in violence in many regions of the world by contributing to conditions that lead to fewer economic opportunities and food scarcity that in turn could fuel gang membership and corruption (Levy et al., Citation2017).

Health issues discussed also have parallels in existing studies on the regions that participants described. For example, Daniela, Maria, and Gabriela’s shared observation of increased dengue, matching the 288% increased risk in dengue in Central America between 2000 and 2017 identified in the Global Burden of Disease study referred to in Hotez et al. (Citation2020). Increased asthma on the Peruvian coast, which Lorena mentioned, is something Butler et al. (Citation2022) discussed as a possible secondary effect of climate change. Monica’s observation of kidney disease in El Salvador is also born out in literature, noting a rise in chronic kidney disease in the region (J. Glaser et al., Citation2016). First identified in 2002 in El Salvador due to higher rates of kidney disease among patients without typical risk factors or disease presentations, the hypothesis was formed of what is now known as heat-stress nephropathy (HSN) (Glaser et al., Citation2016). HSN is thought to be due to the combination of recurrent exposure to high temperatures and dehydration, leading to repeated kidney injury. Over time, this can develop into end-stage-renal disease. While most prevalent in sugarcane workers – likely a result of highest maximum heat exposure and working conditions with infrequent re-hydration – individuals in similar environments, including women and children, can also be affected. Compounding toxin exposures, such as agrochemicals have also been implicated in the disease process, magnified by concentrated runoff in drying well water (Glaser et al., Citation2016).

Through this mixed-methods and multidisciplinary pilot project, which provided information on the lived experience of Latin American migrants to the Atlanta area, we were also able to identify another potential application of this approach to research. As we prepared the analysis of the data for this research, our physician collaborators at the Cosmo Health Center mentioned that they were surprised to learn some of the details of how climate change (or perceived climate change) intersected with and affected everyday life in sending communities and how people discussed health-related issues that they connected to increased drought, flooding, and environmental changes. The perspectives gained from this type of research collaboration can lead to increased knowledge on the part of healthcare professionals about their patient population, which might in turn lead to better health outcomes.

Limitations

As can be expected in a pilot study, this study had several limitations. Our sample size was relatively small, and participants were from different communities and geographic areas, many with heterogeneous and evolving risks due to climate and environmental change. Participants’ length of time since migration also varied, though the majority of IDI participants had arrived in the U.S. in the twenty-first century. Although experiences in participants’ country of origin may have been affected by recall bias, participants in in-depth interviews talked about maintaining connections with their communities of origin and/or returning for visits, which may have given them an even broader picture of the changes taking place in these communities than their counterparts who had arrived more recently. However, for the purposes of data analysis, it might have been useful to limit the sample to people who had migrated in the past two decades.

In terms of our data collection instruments, the structure of some of our questions might have led to under-reporting of climate change as a driver of migration. Although we gave opportunities for participants to give details about climate-related events, future studies could be more explicit in their study design to find parallels between migrants’ narratives and personal histories to existing climate change statistics, while still avoiding leading questions.

Another potential limitation is related to recruitment of participants who either accessed the services of the community centre affiliated with the collaborating health centre or who were patients at this health centre. The location of many of our interviews at the clinic itself, albeit in private rooms, could have impacted the responses of participants to some extent in terms of what they felt comfortable revealing in interviews.

Our sample is not necessarily representative of the population of Latin American migrants from the Atlanta metropolitan area in terms of representation of gender identities or nationalities of origin. Convenience sampling at the clinic, food distribution centre, and daycare settings in the northeast part of metro Atlanta likely contributed to over-representation of both women and of migrants from Mexico and El Salvador. The lived experiences and perceptions of men who migrate from Latin America to the Atlanta area may differ greatly because of gender roles potentially associated with different health outcomes, employment opportunities, and migration decisions. When children and an adult family member or members were included in the initial survey, there was arguably some repetition in the data in terms of people coming from the same household. In IDIs, there was only one example of two people from the same household, but there was a significant age difference, and their migration narratives were quite distinct. Despite the limitations, community recruitment extended alongside relationships of trust, necessary for future partnership, and provides a helpful opening towards understanding the nexus of climate change, migration experiences, and health.

Conclusion

At the 2021 Conference of the Parties (COP26) for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Director General of the International Organisation of Migration, António Vitorino, noted that ‘it has become critical to address the impacts of climate change on migration, displacement, and health … These issues are interconnected but have been addressed in a siloed manner for too long. We must address them together’ (IOM, Citation2021, online). However, this statement does not provide guidelines for how to explore these complex intersections. This study attempted to address this call, demonstrating the importance and promise of mixed-methods research to understand the nexus of climate change, migration, and health. We identified some of the climate change-related vulnerabilities that intersect with social determinants of health and well-being to play a part in decision-making related to migration and that in turn, can impact health outcomes for migrants. In-depth interviews provided opportunities for participants to elaborate on their lived experiences in communities of origins and discuss ways that climate change and climate-related events shaped daily life and complicated economic, social, and political circumstances. Narratives further helped to demystify the relationship among intersecting, multifactorial, and compounding factors that influence migration. For example, increased heat can impact the ability to work outside and thus to be able to a make a living and buy enough food in an already precarious economy or in the face of pre-existing health conditions, which might all play in to the decision to migrate. As global migration continues as a form of adaptation to the climate crisis, understanding these intersections is key to improve health outcomes and address structural barriers to well-being for those who are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff of the CPACS Cosmo Health Center for allowing us to both recruit and conduct interviews on site. Thanks to the participants in our study for their time and willingness to tell us their stories. Thanks also to the Atlanta Global Research and Education Cooperative (AGREC) and the Atlanta Global Studies Center for both grant support and for allowing us to present and further disseminate the results of our research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Participants were from Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Paraguay, Brazil, and Dominican Republic. One participant in the survey was from Puerto Rico; although our initial intent was to capture international migrant experiences from Latin America, people from Puerto Rico (a U.S. territory) fit the criteria we created for the study of people who migrated to the Atlanta metropolitan area from Latin America and the Caribbean, so this participant was included in the analysis. However, we acknowledge that Puerto Ricans moving to the mainland U.S. are internal migrants and that Puerto Ricans have more freedom in migrating, which factors into to decision-making.

2 Continental U.S., in the case of the one participant from Puerto Rico

References

- Argomedo, D. W. (2020). Climate change, drug traffickers and La Sierra Tarahumara. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(4), 81–95. doi:10.5038/1944-0472.13.4.1813. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26965519

- Barnes, J., Dove, M., Lahsen, M., Mathews, A., McElwee, P., MicIntosh, R., & Yager, K. (2013). Contribution of anthropology to the study of climate change. Nature Climate Change, 3(6), 544–545. doi:10.1038/nclimate1775

- Booth, M. (2018). Climate change and the neglected tropical diseases. Advances in Parasitology, 100, 39–126. doi:10.1016/bs.apar.2018.02.001

- Bowles, D. C., Butler, C. D., & Morisetti, N. (2015). Climate change, conflict and health. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 108(10), 390–395. doi:10.1177/0141076815603234

- Butler, C. D., Ewald, B., McGain, F., Kiang, K., & Sanson, A. (2022). Climate change and human health. In S. J. Williams, & R. Taylor (Eds.), Sustainability and the new economics: Synthesising ecological economics and modern monetary theory (pp. 51–68). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78795-0_4

- Caballo, M., Smith, C., & Pettersson, K. (2008). Health challenges. South Asia 2060: Envisioning regional futures (pp. 229–237). https://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/climatechange/carballo-smith-petterssen.pdf.

- Carlson, C. J., Albery, G. F., Merow, C., Trisos, C. H., Zipfel, C. M., Eskew, E. A., & Bansal, S. (2022). Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature, 607(7919), 555–562. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04788-w

- Castro, M. C., Baeza, A., Codeço, C. T., Cucunubá, Z. M., Dal’Asta, A. P., De Leo, G. A., & Santos-Vega, M. (2019). Development, environmental degradation, and disease spread in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Biology, 17(11), 4–11. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000526

- Chincilla, K. (2023). Los vientos de octubre. Retrieved January 15, 2023. https://guanacos.com/vientos-de-octubre-clima-de-el-salvador/.

- Cleaveland, C., & Ihara, E. (2012). ‘They treat us like pests:’ Undocumented immigrant experiences obtaining health care in the wake of a ‘crackdown’ ordinance. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(7), 771–788. doi:10.1080/10911359.2012.704781

- de los Ríos, C., & Almeida, J. (2010). Percepciones y formas de adaptación a riesgos sociambientales en el páramo de Sonsón, Colombia. Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 7(65), 107–124.

- Fierros-González, I., & López-Feldman, A. (2021). Farmers’ perception of climate change: A review of the literature for Latin America. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 9, 672399. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.672399

- Forero, E. L., Hernández, Y. T., & Zafra, C. A. (2014). Latin American perceptions of climate change: Methodologies, tools and adaptation strategies in local communities. A review. Revista UDCA Actualidad & Divulgación Científica, 17(1), 73–85.

- Glaser, J., Lemery, J., Rajagopalan, B., Diaz, H. F., García-Trabanino, R., Taduri, G., & Johnson, R. J. (2016). Climate change and the emergent epidemic of CKD from heat stress in rural communities: The case for heat stress nephropathy. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 11(8), 1472–1483. doi:10.2215/CJN.13841215

- Hotez, P. J., Bottazzi, M. E., Franco-Paredes, C., Ault, S. K., & Periago, M. R. (2008). The neglected tropical diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: A review of disease burden and distribution and a roadmap for control and elimination. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2(9), doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000300

- Hotez, P. J., Damania, A., & Bottazzi, M. E. (2020). Central Latin America: Two decades of challenges in neglected tropical disease control. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(3), 1–7. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007962

- Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). (2020). Ecological threat register 2020. https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ETR_2020_web-1.pdf.

- Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). (2022). Ecological threat register 2022. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/ETR-2022-Web-V1.pdf.

- International Organization of Migration (IOM). (2021). COP26: Direct linkages between climate change, health and migration must be tackled urgently – IOM, WHO, Lancet migration 26: Direct linkages between climate change, health and migration must be tackled urgently – IOM, WHO, Lancet migration. https://www.iom.int/news/cop26-direct-linkages-between-climate-change-health-and-migration-must-be-tackled-urgently-iom-who-lancet-migration.

- International Organization of Migration (IOM). (2023). A complex Nexus. https://www.iom.int/complex-nexus#:~:text=Future%20forecasts%20vary%20from%2025,estimate%20of%20international%20migrants%20worldwide.

- Jach, E., Gloeckner, G., & Kohashi, C. (2020). Social and behavioral research with undocumented immigrants: Navigating an IRB committee. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 42(1), 3–17. doi:10.1177/0739986319899979

- Jacobsen, K. (2023). Climate migration, environmental degradation, and migration. Great decisions, Foreign Policy Association, 2023 edition (pp. 91–100).

- Kalengayi, F. K. N., Hurtig, A. K., Ahlm, C., & Krantz, I. (2012). Fear of deportation may limit legal immigrants’ access to HIV/AIDS-related care: A survey of Swedish language school students in Northern Sweden. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14(1), 39–47. doi:10.1007/s10903-011-9509-y

- Levy, Barry S, Sidel, V.W., & Patz, J.A. (2017). Climate change and collective violence. Annual Review of Public Health, 38(1), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1146/publhealth.2017.38.issue-1

- Malmusi, D., Borrell, C., & Benach, J. (2010). Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class and place of origin. Social Science & Medicine, 71(9), 1610–1619. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.043

- McMichael, C. (2015). Climate change-related migration and infectious disease. Virulence, 6(6), 548–553. doi:10.1080/21505594.2015.1021539

- Morris, J. (2022). Managing, now becoming, refugees: Climate change and extractivism in the Republic of Nauru. American Anthropologist, 124(3), 560–574. doi:10.1111/aman.13764

- Nolas, S. M., Watters, C., Pratt-Boyden, K., & Maglajlic, R. A. (2020). Place, mobility and social support in refugee mental health. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 16(4), 333–348. doi:10.1108/IJMHSC-03-2019-0040

- PAHO. (1998). Impact of Hurricane Mitch in Central America. Retrieved February 12, 2022, from https://www.paho.org/english/sha/epibul_95-98/be984mitch.htm.

- Parsons, L., & Nielsen, J. Ø. (2021). The subjective climate migrant: Climate perceptions, their determinants, and relationship to migration in Cambodia. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111(4), 971–988. doi:10.1080/24694452.2020.1807899

- Poorman, E. (2017, February 21). Caring for immigrant patients when the rules can shift any time | CommonHealth. Retrieved July 5, 2021, from https://www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2017/02/21/immigration-concerns-exam-room.

- Raleigh, C. (2011). The search for safety: The effects of conflict, poverty and ecological influences on migration in the developing world. Global Environmental Change, 21(Suppl. 1), S82–S93. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.08.008

- Ridde, V. (2018). Climate migrants and health promotion. Global Health Promotion, 25(1), 3–5. doi:10.1177/1757975918762330

- Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., & Midgley, A. (2018). Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2018/03/19/groundswell---preparing-for-internal-climate-migration.

- Salas, R., Knappenberger, P., & Hess, J. (2019). 2019 Lancet countdown on health and climate change: Policy brief for the U.S. – C-Change | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Retrieved July 5, 2021, from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/c-change/news/2019-lancet-countdown/.

- Schwerdtle, P. N., McMichael, C., Mank, I., Sauerborn, R., Danquah, I., & Bowen, K. J. (2020). Health and migration in the context of a changing climate: A systematic literature assessment. Environmental Research Letters, 15(10), doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab9ece

- Sellers, S., Ebi, K. L., & Hess, J. (2019). Climate change, human health, and social stability: Addressing interlinkages. Environmental Health Perspectives, 127(4), 1–10. doi:10.1289/EHP4534

- Semenza, J. C., & Ebi, K. L. (2019). Climate change impact on migration, travel, travel destinations and the tourism industry. Journal of Travel Medicine, 26(5), 1–13. doi:10.1093/jtm/taz026

- Short, E. E., Caminade, C., & Thomas, B. N. (2017). Climate change contribution to the emergence or re-emergence of parasitic diseases. Infectious Diseases: Research and Treatment, 10. doi:10.1177/1178633617732296

- Timonen, V., Foley, G., & Conlon, C. (2018). Challenges when using grounded theory: A pragmatic introduction to doing GT research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 1–10. doi:10.1177/1609406918758086

- Treulen, K. (2008). Análisis sobre el impacto de los cambios climáticos en la vida de las mujeres mapuche de la región de la Araucanía, Pueblo Mapuche. Chile. In A. Ulloa, E. Escobar, L. Donato, & P. Escobar (Eds.), Mujeres indígenas y cambio climático. Perspectivas latinoamericanas (pp. 71–82). Ed. UNAL-Fundación Natura-UNODC.

- Twinomuhangi, R., Sseviiri, H., & Kato, A. M. (2023). Contextualising environmental and climate change migration in Uganda. Local Environment, 28(5), 580–601. doi:10.1080/13549839.2023.2165641

- UN-DESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Population Division. (2020). International migration 2020 highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/452). https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf.

- Watts, N., Amann, M., Arnell, N., Ayeb-Karlsson, S., Belesova, K., Boykoff, M., & Montgomery, H. (2019). The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. The Lancet, 394(10211), 1836–1878. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6

- Welch-Devine, M., Sourdril, A., & Burke, B. J. (2020). Changing climate, changing worlds. Springer, 1–273. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37312-2.

- Wenden, C. W. (2016). New migrations. Sur File on Migration and Human Rights, 13(23), 17–28.

- Whitmarsh, L., & Capstick, S. (2018). Perceptions of climate change. In S. Clayton, & C. Manning (Eds.), Psychology and climate change: Human perceptions, impacts, and responses (pp. 13–33). Elsevier Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-813130-5.00002-3