ABSTRACT

Despite tobacco marketing diversification, limited research has examined use profiles across countries, particularly in relation to consumer values (e.g. appeal of innovation, conscientiousness). Using 2021 data, latent class analysis assessed past-month use of seven tobacco products (cigarettes, electronic cigarettes [e-cigarettes], heated tobacco products, cigars, hookah, pipe, smokeless) among adults reporting past-month use in the United States (US n = 382) and Israel (n = 561). Multivariable multinomial regression examined consumer values and sociodemographics in relation to country-specific class membership. US classes included: primarily cigarette 58.1%; e-cigarette–no cigarette 17.5%; primarily cigar 14.9%; and poly-product 9.9%. Higher innovation correlated with e-cigarette–no cigarette and poly-product (vs. primarily cigarette) use. Other correlates included being: younger with e-cigarette–no cigarette; male, Black, and more educated with primarily cigar; and Black and Asian (vs. White) with poly-product. Israel classes included: primarily cigarette 39.0%; moderate poly-product 40.3%; high poly-product 13.4%; and hookah 7.3%. Lower conscientiousness correlated with moderate poly-product (vs. primarily cigarette) use; higher innovation correlated with high poly-product; lower innovation correlated with hookah. Other correlates included being: younger, male, and more educated with moderate poly-product; male and sexual minority with high poly-product; and Arab with hookah. Tobacco consumer segments within and across countries likely reflect different consumer values and industry marketing targets.

Introduction

The global tobacco market has dramatically evolved in the past decade to include a broad range of alternative tobacco and nicotine products, including electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), heated tobacco products (HTPs), cigars, hookah, and various forms of smokeless tobacco products (World Health Organization, Citation2022). The product market and regulatory context vary greatly across countries; thus, research assessing country-specific tobacco use is imperative for informing tobacco control efforts.

Diffusion of Innovations Theory (DOI) explains how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technologies – like these products – are adopted in different social systems (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). Three general sets of variables influence diffusion. First, diffusion is influenced by an innovation’s attributes, often assessed with regard to: cost; effectiveness or relative advantage (compared to what it would replace); complexity and compatibility (e.g. ease and convenience of use); and observability or trialability (i.e. whether its use can be seen or tried) (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). The second set of factors pertains to consumer characteristics, particularly who will be the first to adopt (innovators), sometimes because of an innovation’s novelty but more often because of the individual’s desire to be the first to try what is new or take risks. Those who do not immediately adopt an innovation typically adopt it later after conscientiously appraising its advantages or due to pressure to do so (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). People may have some characteristics of both groups, depending on the nature of the innovation. Third, diffusion is impacted by the larger sociopolitical context (e.g. how proponents and opponents frame the innovation) (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). This includes how the tobacco industry frames and promotes these products, as well as how regulatory contexts shape restrictions on tobacco and nicotine products’ marketing, use, and social norms (Almeida et al., Citation2021; Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002).

As newer tobacco and nicotine products enter various markets globally, tobacco industry marketing promotes their positive attributes, particularly their advantages relative to existing products (Almeida et al., Citation2021; Kislev & Kislev, Citation2020). How their advantages are promoted may differ across countries, depending on restrictions on existing products like cigarettes, and regulations regarding the extent to which advertising can explicitly or implicitly promote health advantages. Industry marketing has been shown to impact consumer appraisal, perceptions, and rate of adoption of newer products (e.g. HTPs) (Kislev & Kislev, Citation2020; Lekezwa & Zulu, Citation2023). How these products are initially promoted may result in their adoption being concentrated among adults who currently or previously used other tobacco products (Adkison et al., Citation2013; Dockrell et al., Citation2013; Kislev & Kislev, Citation2020; Tattan-Birch et al., Citation2022).

To understand the role of regulatory context for the tobacco and nicotine product market, it is critical to study differences in consumer behaviour across countries with differing sociopolitical characteristics. The current study focuses on adults in two countries – the United States (US) and Israel – which were chosen based on their similarities and differences with regard to tobacco control efforts and tobacco use. Regarding tobacco control, the US signed the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2004 but has not ratified it (Framework Convention Alliance, Citation2018), while Israel signed and ratified the FCTC in 2003 and 2005, respectively (Rosen et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, these countries have similar legislations regarding health warning labels (text, ≥ 50% of package face), advertising bans/restrictions, and smoke-free policies (Rosen & Peled-Raz, Citation2015). In terms of differences, Israel established the minimum legal sales age requirement of 18 in 2018 (Rosen et al., Citation2020), while US federal legislation increased it from 18 to 21 in 2019 (US Food and Drug Administration, Citation2020b). Additionally, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates all tobacco products in the US (as of 2016), and has measures to oversee new products entering the market (US Food and Drug Administration, Citation2019) and to authorise modified risk or exposure claims in the marketing of certain products (e.g. IQOS, an HTP) (US Food and Drug Administration, Citation2020c). Further, the FDA banned the sale of flavoured cartridge-based e-cigarettes in 2020 (US Food and Drug Administration, Citation2020a); some states and localities also have comprehensive flavour restrictions on e-cigarettes or all tobacco products (Truth Initiative, Citation2021). Tobacco control legislation in Israel banned advertising in all media (excluding print) in 2019, and banned point-of-sale displays and required plain packaging for all tobacco and nicotine products in 2020 (Baumer, Citation2019; Wootliff, Citation2019).

Tobacco use profiles likely differ across countries, as the industry adjusts its marketing strategies to respond to sociopolitical factors (Almeida et al., Citation2021). In the US and Israel, the tobacco markets are similar in terms of prominent cigarette companies and brands (e.g. Marlboro is the leading brand in both countries (Huit, Citation2016; Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021; Sun, Citation2017)), high availability of e-cigarettes and hookah (Cornelius et al., Citation2022; Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021), and low HTP use rates (Berg, Romm, et al., Citation2021; Levine et al., Citation2023). On the other hand, cigars and smokeless tobacco are highly available in the US, but less so in Israel. In terms of use prevalence, in 2021, 18.7% of US adults reported current (past-month) use of any commercial tobacco product, including cigarettes (11.5%), e-cigarettes (4.5%), cigars (3.5%), smokeless tobacco (2.1%), and pipes (including hookah, 0.9%) (Cornelius et al., Citation2022). Any product use was higher among men, certain racial/ethnic minority groups (e.g. American Indian/Alaska Natives), those representing indicators of lower socioeconomic status (SES; lower education or income), those <65, and sexual minorities (Cornelius et al., Citation2022). In Israel, 2021 current adult cigarette and e-cigarette use rates were 20.1% and 1.6% (Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021). Rates differ between the two largest ethnic groups; for example, cigarette use prevalence is 24.2% among Arab individuals and 19.1% among Jewish individuals. Rates further differ by sex (e.g. cigarettes: Arab men, 38.2%; Jewish men, 22.6%; Jewish women, 15.8%; Arab women, 10.2%; e-cigarettes: men, 2.9%; women, 0.4%; Arab, 2.8%; Jewish, 1.2%). Moreover, cigarette use is more prevalent in lower education groups (Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021).

While use prevalence estimates provide some information, research examining use profiles represented in a population – for example, through latent class analysis (LCA) – might enhance our understanding of how and why products are used, and by whom. One US-based LCA study of current use frequency of nine tobacco products, using adult data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (2016–2017) (Mistry et al., Citation2021), identified six classes: non-users (75.7%); daily exclusive cigarette users (15.5%); occasional cigarette and poly-product users (3.8%); frequent e-cigarette and occasional cigarette users (2.2%); daily smokeless tobacco and infrequent cigarette users (2.0%); and occasional cigar users (0.8%) (Mistry et al., Citation2021). These groups differed by sociodemographics (e.g. younger, male, and more educated more likely in the classes using alternative products) (Mistry et al., Citation2021).

To date, no LCA studies have examined tobacco use profiles in Israel. However, LCA studies in other countries suggest likely country-specific use profiles. For example, an LCA of India’s 2016–17 Global Adult Tobacco Survey data identified five tobacco use classes: predominantly oral chewable products (51.7%), predominantly cigarette (24.3%), predominantly bidi (22.7%), poly-product (0.5%), and snuff and chewable products (0.8%) (Tripathy & Maha Lakshmi, Citation2023). These distinct classes highlight the nuances of India’s tobacco market which has a significant representation of smokeless products (Mohan et al., Citation2018). Given the tradition of hookah use in the Middle East (Maziak et al., Citation2015), an LCA of Iranian hookah users was conducted, which indicated classes differing in nicotine dependence (Adham et al., Citation2021).

In summary, the tobacco industry uses specific marketing strategies in each country, which consider the country’s sociopolitical context – and DOI provides a lens for the industry and public health to anticipate how to target and understand potential consumers. However, limited research has examined the adult tobacco use profiles across countries or using a DOI perspective. This study aimed to address these limitations. Specifically, we examined: (1) different tobacco use profiles (using LCA) among US and Israeli adults (collectively and separately); and (2) correlates of tobacco use classes – including sociodemographics and measures tapping consumer values of ‘innovation’ and ‘conscientiousness’ (per DOI (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002)).

Methods

Study design and participants

We used the data from a cross-sectional online survey focused on tobacco use and related factors conducted in October–December 2021 among adults in the US and Israel. Study procedures are detailed elsewhere (Levine et al., Citation2023). This study received ethical approvals from George Washington University (NCR213416) and Hebrew University (27062021) and adhered to STROBE guidelines.

Briefly, eligibility criteria were: (1) 18–45 years old (to capture adults most likely aware of, interested in, or with prior use of newer tobacco products (Berg, Romm, et al., Citation2021; Gravely et al., Citation2020; Karim et al., Citation2022; Nyman et al., Citation2018; Phan et al., Citation2020; Yi et al., Citation2021)); and (2) English-speaking (US), or Hebrew- or Arabic-speaking (Israel). Our target sample size was 2,000 total participants (1,000/country). We aimed to recruit roughly equal sample sizes of males and females in each country. Given the literature documenting racial/ethnic differences in tobacco use in each country (Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021; US Census Bureau, Citation2021), the samples were constructed to allow for subgroup analyses. Specifically, racial/ethnic group targets in the US were: 45% White, 25% Black, 15% Asian, and 15% Hispanic; and in Israel were: 80% Jewish and 20% Arab. We aimed for 40% tobacco users to ensure sufficient sample sizes to examine differences among key demographic groups. These sample composition parameters were intended to achieve ≥80% power (at α = .05) to detect small to medium effects in relation to the primary outcomes of interest (newer tobacco product use). The final sample included 2,222 participants (US, n = 1,128; Israel, n = 1,094).

The survey samples were constructed using somewhat different approaches in the two countries due to differences in the availability and nature of survey panels, a common limitation in international research (Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group, Citation2020; International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project, Citation2020).

The US survey was conducted primarily using KnowledgePanel® (KP), a probability-based web panel designed to be representative, and recruited via random digit dialling and address-based sampling. KP members are incentivised by points redeemable for cash (∼$5 for a 25-minute survey). Of 4960 panelists recruited, 2397 (48.3%) completed eligibility screening, and 1095 (45.7%) completed the survey. To meet subgroup recruitment targets, an opt-in (i.e. off-panel) convenience sample of US adults reporting Asian race and tobacco use were also recruited by Ipsos via banner ads, web pages, and e-mail invitations; those who clicked ads completed eligibility screening (i.e. sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use). Of 353 individuals screened, 33 (9.3%) were eligible and completed the survey.

The Israeli survey was conducted among an opt-in sample, using the same approach specified above. Of 2970 individuals who completed the eligibility screening and were eligible, 1,094 (36.8%) completed the survey.

Measures

Tobacco use

We assessed past 30-day (current) use of seven products: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, HTPs, hookah/waterpipe/nargila, cigar products, pipe tobacco, and smokeless tobacco (each operationalised as any vs. no use).

Consumer values (innovation, conscientiousness)

We administered a newly-developed measure informed by DOI, specifically characteristics of those who adopt innovations early (‘innovators’) vs. later (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). Items were developed by the study team and examined for face validity; then, adult volunteers in the US and Israel pilot tested the items in English, Hebrew, and Arabic to assess comprehension. The final measure included 11 statements (), and participants were asked to indicate the extent to which each item described them (1 = not at all to 5 = very much/completely). Principal component factor analysis yielded 2 factors, indicating one’s tendencies to value ‘innovation’ (five items, e.g. ‘I like to be the first among my friends and family to try something new’; ‘When I shop, I look for what is new’) or ‘conscientiousness’ (six items, e.g. ‘I like to weigh the pros and cons of a product before trying it’; ‘I like to stick with brands I know’). Subscale scores were calculated as averages of the items (i.e. higher scores indicate greater tendencies for each dimension). Cronbach's alphas were .80 and .67, respectively; subscale correlation = .09 (p < .001).

Table 1. Diffusion of innovation factor analysis results.

Sociodemographics

We assessed age, sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, and marital status.

Data analysis

The current study analysed data from participants reporting past 30-day (current) use of ≥1 tobacco product (US, n = 382; Israel, n = 561). First, latent class analysis (LCA) assessed tobacco use profiles, using the seven tobacco use variables, in the total sample (Collins & Lanza, Citation2010; Hagenaars & McCutcheon, Citation2002). We estimated model fit indices for 1–6 class structures and used multiple model fitness criteria: Log-likelihood (LL), Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size adjusted BIC (SABIC) (Vrieze, Citation2012), and entropy values. LL values closer to zero, lower values of AIC, BIC, and SABIC, and larger values of entropy indicate better model fit (Nylund et al., Citation2007). We also used the Vuong–Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR-LRT) and bootstrapped parametric likelihood ratio test (BLRT) to compare the model with K classes to the model with K-1 classes; significant p-values indicate better model fit for the model with K classes (Nylund et al., Citation2007). Other considerations included smallest class (>5%) and class interpretability. Robust Maximum Likelihood was used. We further examined whether tobacco use profiles differed by country using multiple-group LCA. Measurement invariance (comparing the model constraining conditional probabilities for the use of each product to be equal across countries vs. unconstrained model) was assessed based on Satorra–Bentler (SB) scaled Chi-square difference test. After determining the final number of classes, multivariable multinomial logistic regression assessed associations between predictors (i.e. sociodemographics, consumer values) and class membership. LCA and regressions were conducted in Mplus 8.7 and SPSS.v27, respectively.

Results

Determination of classes in the total sample and by country

In the total sample, the four-class model had the lowest BIC, and the six-class model had the lowest LL, AIC, and SABIC (). The VLMR-LRT and bootstrapped LRT were significant for all models. The smallest classes for the four-, five-, and six-class models were 11.7% (n = 110), 5% (n = 49) and 2% (n = 18), respectively. Thus, the four-class model was chosen (entropy = .853).

Table 2. Model fit/diagnostic criteria for LCA models with 1–6 classes in the total sample, and in the US and Israel samples, respectively.

In multiple-group LCA assessing measurement invariance, the SB scaled Chi-square test showed decreased model fit after constraining the conditional probability to be equal across countries, supporting measurement non-invariance (X2 = 129.40, df = 29, p < .001) and thus, indicated country-specific LCAs (). For the US sample (n = 382, 33.9% of the US sample), we considered differences in model fitness indicators (e.g. BIC for four classes, LL and AIC for six, SABIC for five) and differences in smallest class size (i.e. n = 10, 2.6% for five-class model vs. n = 38, 10% for four-class model), and chose the four-class model. For the Israel sample (n = 561, 51.3% of the Israeli sample), we considered differences in model fitness criteria (e.g. LL and AIC supported six, BIC for three, SABIC for four) and interpretability (including across samples), ultimately choosing the four-class model.

Class characteristics in the total sample

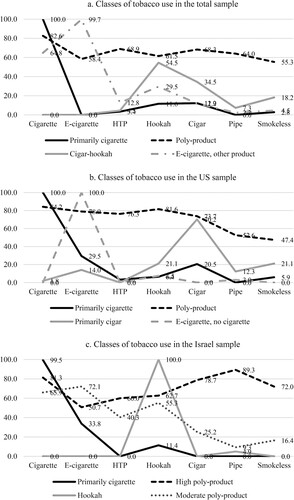

The four classes in the total sample (, (a)) included: primarily cigarette (n = 320, 33.9%, average number of products used = 1.30), with 100% using cigarettes, 0% e-cigarette and pipe, ∼12% hookah and cigar, and ∼3% HTP and smokeless tobacco; poly-product (n = 161, 17.1%, average products used = 4.60), with >55% using each product; cigar–hookah (n = 110, 11.7%, average products used = 1.19), with 54.5% using hookah, 34.5% cigars, 0% cigarette or e-cigarette, and <20% other products; and e-cigarette–other product (n = 352, 37.3%, average products used = 2.26), with 99.7% using e-cigarettes, 64.8% cigarettes, 29.5% hookah, and <13% other products. The classes reporting the greatest number of days of use for each product were: primarily cigarette and e-cigarette–other product for cigarette use (primarily cigarette: M = 18.89, SD = 12.01; e-cigarette–other product: M = 16.14, SD = 11.17 vs. poly-product: M = 8.04, SD = 8.11), e-cigarette–other product for e-cigarettes (M = 11.65, SD = 11.34 vs. poly-product: M = 6.42, SD = 5.75), and cigar–hookah for smokeless tobacco (M = 13.60, SD = 13.41 vs. M < 8 in other classes).

Figure 1. The final LCA models in the full sample, US sample and Israel sample, respectively. Notes: Across figures, primarily cigarette indicated by solid black line, poly-product by dashed black line, cigar–hookah by solid grey line, and fourth group (e.g. e-cigarette, moderate poly-product) by grey lines with distinct dashes.

Table 3. Select characteristics for the total sample, and for the US and Israel samples, respectively.

Class characteristics by country

The four US classes (, (b)) included: primarily cigarette (n = 222, 58.1%, average number of products used = 1.65), with 100% using cigarettes, 29.5% e-cigarettes, 20.5% cigars, and 0–6.4% other products; poly-product (n = 38, 9.9%, average products used = 4.95), with use ranging from 47.4% for smokeless to 84.2% for cigarettes; primarily cigar (n = 57, 14.9%, average products used = 1.40), with 70.2% using cigars, 21.1% hookah and smokeless, and 0–14% other products; and e-cigarette–no cigarette (n = 67, 17.5%, average products used = 1.10), with 100% using e-cigarettes, 0% cigarettes, HTPs, cigars, and smokeless, and <8% other products. The classes reporting the greatest number of days of use for each product were: primarily cigarette for cigarette use (M = 19.49, SD = 11.85 vs. poly-product: M = 10.41, SD = 10.92), e-cigarette–no cigarette for e-cigarettes (M = 19.46, SD = 12.49 vs. M ≤ 16 in other classes), and primarily cigar for smokeless (M = 23.50, SD = 11.02 vs. M < 10 in other classes).

The four Israeli classes (, (c)) included: primarily cigarette (n = 219, 39.0%, average number of products used = 1.45), with 99.5% using cigarettes, 33.8% e-cigarettes, 11.4% hookah, and 0% other products; high poly-product (n = 75, 13.4%, average products used = 4.96), with >50% using each product (ranging from 50.7% e-cigarettes to 89.3% pipe); hookah (n = 41, 7.3%, average products used = 1.05), with 100% using hookah and ∼0% other products; and moderate poly-product (n = 226, 40.3%, average products used = 2.84), with 72.1% using e-cigarettes, 65.9% cigarettes, 55.3% hookah, 40.3% HTPs, 25.2% cigars, and <17% other products. The classes reporting the greatest number of days of use for each product were: primarily cigarette for cigarette use (M = 17.67, SD = 11.33 vs. M < 12 in other classes), high poly-product for HTPs, cigars, and smokeless (M = 6–8 vs. M = 4–5 in primarily cigarette), and high poly-product and hookah for hookah use (high poly-product: M = 7.15, SD = 9.98; hookah: M = 7.05, SD = 8.98 vs. primarily cigarette: M = 3.00, SD = 4.03; moderate poly-product: M = 5.43, SD = 5.22).

LCA model comparisons

All three models (total, US, Israel) indicated primarily cigarette and poly-product use classes, with varying prevalence. While the total sample model included a cigar/hookah use class, these classes were distinctly characterised as primarily use of cigars in the US and hookah in Israel. In the total sample, there was a class of e-cigarette and other tobacco product use, while the US sample had an e-cigarette use class (with 100% e-cigarette use but nearly no use of other products), and the Israel sample had a moderate poly-product use class with similar proportions of cigarette and e-cigarette use, with half also using HTPs and hookah.

Correlates of class membership in the total sample

In bivariate analyses, class membership was associated with country, age, sex, sexual orientation, and innovation scores, but no other factors (see for specific associations). Multinomial logistic regression () indicated the following correlates of class membership (referent group: primarily cigarette) – poly-product: being from Israel (vs. US: aOR = 1.68, 95%CI = 1.07–2.65), younger (aOR = 0.94, 95%CI = 0.91–0.97), male (vs. female: aOR = 1.79, 95%CI = 1.19–2.70), sexual minority (aOR = 1.91, 95%CI = 1.14–3.14), and higher innovation scores (aOR = 1.87, 95%CI = 1.49–2.35); cigar–hookah: younger age (aOR = 0.96, 95%CI = 0.93–0.99), being male (aOR = 1.75, 95%CI = 1.11–2.78), and education ≥ college degree (aOR = 1.65, 95%CI = 1.04–2.64); and e-cigarette–other product: younger age (aOR = 0.93, 95%CI = 0.91–0.96), being married/cohabitating (aOR = 1.43, 95%CI = 1.02–1.99), and higher innovation scores (aOR = 1.49, 95%CI = 1.25–1.78).

Table 4. Multinomial regression analyses identifying correlates of tobacco use class membership among past 30-day tobacco users in the total sample, and the US and Israel samples, respectively (ref: primarily cigarette use group in each LCA).

Correlates of class membership in the US sample

Bivariate analyses showed that class membership was associated with age, sex, race/ethnicity, and innovation scores (see for specific associations). Multivariable multinomial regression () indicated the following correlates of class membership (referent group: primarily cigarette) – poly-product: being Black and Asian (vs. White: aOR = 4.63, 95%CI = 1.56–13.76; aOR = 4.01, 95%CI = 1.23–12.99) and higher innovation (aOR = 2.32, 95% CI = 1.51–3.57); primarily cigar: being male (aOR = 2.04, 95%CI = 1.03–4.00), being Black (aOR = 3.79, 95%CI = 1.78–8.07), and education ≥ college degree (aOR = 2.31, 95%CI = 1.15–4.64); and e-cigarette–no cigarette: younger age (aOR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.89–0.97) and higher innovation (aOR = 1.35, 95%CI = 1.00–1.82).

Correlates of class membership in the Israel sample

Bivariate analyses showed that class membership was associated with age, sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and conscientiousness scores (see for specific associations). Multivariable multinomial regression () indicated the following correlates of class membership (referent group: primarily cigarette) – high poly-product: being male (aOR = 2.94, 95%CI = 1.67–5.26), sexual minority (aOR = 2.93, 95%CI = 1.53–5.61), and higher innovation (aOR = 1.43, 95%CI = 1.02–1.99); hookah: being Arab (vs. Jewish: aOR = 3.85, 95%CI = 1.72–8.33) and lower innovation (aOR = 0.66, 95%CI = 0.44–0.99); and moderate poly-product: younger age (aOR = 0.93, 95%CI = 0.90–0.96), being male (aOR = 2.33, 95%CI = 1.54–3.45), education ≥ college degree (aOR = 1.88, 95%CI = 1.21–2.91), and lower conscientiousness (aOR = 0.58, 95%CI = 0.41–0.80).

Discussion

This study examined different use profiles of various tobacco products among US and Israeli adults and examined correlates of tobacco use classes – including sociodemographics and measures tapping consumer values of ‘innovation’ and ‘conscientiousness’ (per DOI (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002)). We found four different use profiles among US and Israel adults. While both samples included a class who primarily used cigarettes and a poly-product class, these classes and others differed in the proportion of the samples they represented, a combination of products used, and correlates of use.

Both samples included primarily cigarette use classes (58.1% in US LCA, 39.0% in Israel), comprised of nearly 100% cigarette smokers using ∼1.5 products in the past month, most commonly e-cigarettes (∼30% in each country). The total sample indicated a cigar–hookah use class; however, country-specific LCAs indicated groups using primarily cigars in the US (70.2% used cigars, 21.1% hookah and smokeless tobacco) and hookah in Israel, all of whom used hookah but almost nothing else. The poly-product use class in the US and the high poly-product use class in Israel represented ∼10–13.4% of the respective samples and used nearly 5 products on average in the past month. The final group in Israel – the moderate poly-product use class (40.3%) – used an average of ∼3 products, with >50% using e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and hookah. In the final class in the US (17.5%), all members used e-cigarettes but very little or no other products, including no cigarette use.

Compared to primarily cigarette users, poly-product users in both countries and e-cigarette–no cigarette users in the US were more innovation-oriented, and moderate poly-product users in Israel had lower conscientiousness scores. These findings support DOI, which suggests that those who initially adopt an innovation tend to do so due to its novelty or their own proclivity to change and desire to be the first to try new products, whereas those who follow may more intentionally appraise its advantages or as social norms change (Dearing & Cox, Citation2018; Rogers, Citation2002). The poly-product users also used more traditional products, reflecting that the adoption of newer products does not necessarily imply the abandonment of previously used products, which may suggest that newer products may be used only in certain contexts, for example, when cigarette use is not allowed. In addition, hookah (vs. primarily cigarette) users in Israel were less innovation-oriented, which may be related to the historical presence of hookah use in Israel (Rosen et al., Citation2020) and the Middle East more broadly, particularly among Arab populations (Maziak et al., Citation2015) (as also found in this study).

Historical context was also important to consider in terms of potential cohort effects (i.e. age), specifically the younger age of the e-cigarette use class in the US (representing no cigarette use) and the moderate poly-product use class in Israel (representing the largest proportion of e-cigarette users), given the significant emergence of e-cigarettes in the past decade (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Additionally, compared to primarily cigarette users, in Israel, both poly-product use classes were more likely male, the high poly-product use group was more likely sexual minority, and the moderate poly-product users were more educated; in the US, poly-product users were more likely Black or Asian (vs. White), and primarily cigar users were more likely Black, male, and college-educated. These findings reflect those of national data in the US and Israel examining factors associated with the use of distinct products (Cornelius et al., Citation2022; Israel Minister of Health, Citation2021), and with analyses examining profiles of tobacco use in the US (Mistry et al., Citation2021) and elsewhere (Adham et al., Citation2021; Mohan et al., Citation2018; Vardavas et al., Citation2015) (i.e. younger, male, and more educated more likely in alternative product classes (Mistry et al., Citation2021)). These findings also coincide with concerns raised that early adopters of newer products may represent more advantaged groups that may be prioritised by the industry (Brown et al., Citation2014; Hartwell et al., Citation2017; Kock et al., Citation2019), or that slower acquisition of knowledge about or access to innovations among disadvantaged subgroups (e.g. by race/ethnicity, SES) may perpetuate inequality (Bhatti et al., Citation2011; Boushey, Citation2016; Buchanan et al., Citation2015).

Regarding implications for research and practice, findings illustrated the utility of DOI in contextualising tobacco use profiles across countries, particularly in relation to the sociopolitical context of tobacco regulation and marketing. Further research should elucidate mechanisms underlying differences in latent class structures among adults in the two countries, for example, other consumer attributes or country-specific advertising content emphasising different product attributes. Such work showed that US FDA authorisation of IQOS to use reduced exposure claims in advertising was an important component of IQOS’ marketing in the US, as well as in other countries (Berg, Abroms, et al., Citation2021; Berg, Romm, et al., Citation2021; Duan et al., Citation2022; Khayat et al., Citation2022). Moreover, such research examining latent classes of adults who use tobacco should consider differing public and healthcare provider sentiment regarding harm reduction products, like e-cigarettes and HTPs, as such context might impact use profiles.

Study strengths and limitations

Study strengths include the application of multiple-groups LCA to determine use profiles of multiple tobacco products in a heterogeneous sample of adults (with regard to sociodemographics and tobacco use behaviours) in two countries with similar yet distinct tobacco use and control contexts (the US and Israel), and the inclusion of novel covariates (e.g. consumer values) potentially targeted by the tobacco industry. Limitations include limited generalisability given recruitment of participants via an online panel in the US and via an opt-in panel in Israel, potential differences between those who participated vs. chose not to, our restricted age range (ages 18–45), and limited ability to conduct more in-depth analyses within use classes due to small subgroup sample sizes. Additionally, the cross-sectional design and self-report measures preclude causal inferences and introduce the potential for bias reports. Finally, this study did not account for all potentially important factors (e.g. other substance use, mental health) (Bar-Or et al., Citation2021; Lim et al., Citation2023; Rodzlan Hasani et al., Citation2023).

Conclusions

This study succinctly characterised differences in complex population-level latent profiles of the use of various tobacco products and across two countries. Common use profiles included primarily cigarette use and poly-product use, while countries differed in how cigar, hookah, and e-cigarette use profiles were manifested. Consumer values were important correlates; for example, being innovation-oriented was related to poly-product use. Moreover, the historical context of hookah in the Middle East and alternative tobacco products (particularly e-cigarettes) globally were reflected by use profiles and sociodemographic correlates of use (e.g. age, Arab ethnicity). The differential tobacco use profiles across countries underscore the need to examine how different consumer segments are targeted and differentially impacted by the diverse tobacco marketplace, particularly given different sociopolitical contexts. Furthermore, reducing the population impacts of cigarette use, including co-use with other tobacco products, as well as any perpetuating disparities, should remain a public health priority.

Acknowledgements

Conceptualisation: YW, CRL, YC, ZD, YBZ, HL, LCA, AK, CJB. Methodology: YW, CJB. Validation: YW, CJB. Formal analysis: YW, CJB. Investigation: YBZ, HL, CJB. Data Curation: YW, ZD, CJB. Writing – Original Draft: YW, CJB. Writing – Review & Editing: YW, CRL, YC, ZD, YBZ, HL, LCA, AK, CJB. Visualisation: YW, CJB. Supervision: YBZ, HL, CJB. Project administration: YBZ, HL, CJB. Funding acquisition: YBZ, HL, CJB.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adham, D., Kalan, M. E., Fazlzadeh, M., & Abbasi-Ghahramanloo, A. (2021). Latent class analysis of initial nicotine dependence among adult waterpipe smokers. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, 19(2), 1765–1771. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40201-021-00731-9

- Adkison, S. E., O'Connor, R. J., Bansal-Travers, M., Hyland, A., Borland, R., Yong, H.-H., Cummings, K. M., McNeill, A., Thrasher, J. F., & Hammond, D. (2013). Electronic nicotine delivery systems: International tobacco control four-country survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(3), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018

- Almeida, A., Galiano, A., Golpe, A. A., & Álvarez, J. M. M. (2021). The usefulness of marketing strategies in a regulated market: Evidence from the Spanish tobacco market. E + M Ekonomie a Management, 24(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2021-2-011

- Bar-Or, R. L., Kor, A., Jaljuli, I., & Lev-Ran, S. (2021). The epidemiology of substance use disorders among the adult Jewish population in Israel. European Addiction Research, 27(5), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513776

- Baumer, L. (2019). Israel to paint cigarette, e-cigarette packages with world's ugliest color. Retrieved January 3, from https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3753353,00.html.

- Berg, C. J., Abroms, L. C., Levine, H., Romm, K. F., Khayat, A., Wysota, C. N., Duan, Z., & Bar-Zeev, Y. (2021). IQOS marketing in the US: The need to study the impact of FDA modified exposure authorization, marketing distribution channels, and potential targeting of consumers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (19), 10551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910551

- Berg, C. J., Romm, K. F., Bar-Zeev, Y., Abroms, L. C., Klinkhammer, K., Wysota, C. N., Khayat, A., Broniatowski, D. A., & Levine, H. (2021). IQOS marketing strategies in the USA before and after US FDA modified risk tobacco product authorisation. Tobacco Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056819

- Berg, C. J., Romm, K. F., Patterson, B., & Wysota, C. N. (2021bb). Heated tobacco product awareness, use, and perceptions in a sample of young adults in the United States. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 23(11), 1967–1971. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntab058

- Bhatti, Y., Olsen, A. L., & Pedersen, L. H. (2011). Administrative professionals and the diffusion of innovations: The case of citizen service centres. Public Administration, 89(2), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01882.x

- Boushey, G. (2016). Targeted for diffusion? How the use and acceptance of stereotypes shape the diffusion of criminal justice policy innovations in the American states. American Political Science Review, 110(1), 198–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055415000532

- Brown, J., West, R., Beard, E., Michie, S., Shahab, L., & McNeill, A. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: Findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 39(6), 1120–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.009

- Buchanan, A., Cole, T., & Keohane, R. O. (2015). Justice in the diffusion of innovation. In Political Theory Without Borders: Philosophy, Politics and Society 9, 133–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119110132.ch7

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cornelius, M. E., Loretan, C. G., Wang, T. W., Jamal, A., & Homa, D. M. (2022). Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(11), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7111a1

- Dearing, J. W., & Cox, J. G. (2018). Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice. Health Affairs, 37(2), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1104

- Dockrell, M., Morrison, R., Bauld, L., & McNeill, A. (2013). E-cigarettes: Prevalence and attitudes in Great Britain. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15(10), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt057

- Duan, Z., Henriksen, L., Vallone, D., Rath, J. M., Evans, W. D., Romm, K. F., Wysota, C., & Berg, C. J. (2022). Nicotine pouch marketing strategies in the USA: An analysis of Zyn, On! and Velo. Tobacco ControlPublished Online First: 11 July 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc-2022-057360

- Framework Convention Alliance. (2018). Parties to the WHO FCTC (ratifications and accessions). https://fctc.org/parties-ratifications-and-accessions-latest/.

- Global Adult Tobacco Survey Collaborative Group. (2020). Global adult tobacco survey (GATS): sample design manual. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Gravely, S., Fong, G. T., Sutanto, E., Loewen, R., Ouimet, J., Xu, S. S., Quah, A. C. K., Thompson, M. E., Boudreau, C., Li, G., Goniewicz, M. L., Yoshimi, I., Mochizuki, Y., Elton-Marshall, T., Thrasher, J. F., & Tabuchi, T. (2020). Perceptions of harmfulness of heated tobacco products compared to combustible cigarettes among adult smokers in Japan: Findings from the 2018 ITC Japan survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072394

- Hagenaars, J. A., & McCutcheon, A. L. (2002). Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Hartwell, G., Thomas, S., Egan, M., Gilmore, A., & Petticrew, M. (2017). E-cigarettes and equity: A systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tobacco Control, 26(e2), e85–e91. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222

- Huit, I. (2016). In four years: Cigarette sales have dropped by 19%. Globes Magazine. https://www.globes.co.il/news/article.aspx?did=1001101863.

- International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. (2020). International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project: 4-Country Smoking & Vaping W3. https://itcproject.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/documents/ITC_4CV3_Recontact-Replenishment_web_Eng_16Sep2020_1016.pdf.

- Israel Minister of Health. (2021). The report of the Minister of Health on smoking in Israel for 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2023, from https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/publications/reports/smoking-2021

- Karim, M. A., Talluri, R., Chido-Amajuoyi, O. G., & Shete, S. (2022). Awareness of heated tobacco products among US adults–health information national trends survey, 2020. Substance Abuse, 43(1), 1023–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2022.2060440

- Khayat, A., Berg, C. J., Levine, H., Rodnay, M., Abroms, L., Romm, K. F., Duan, Z., & Bar-Zeev, Y. (2022). PMI’s IQOS and cigarette ads in Israeli media: A content analysis across regulatory periods and target population subgroups. Tobacco Control. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc-2022-057671.

- Kislev, M., & Kislev, S. (2020). The market trajectory of a radically new product: E-cigarettes. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 12(4), 63–92. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v12n4p63

- Kock, L., Shahab, L., West, R., & Brown, J. (2019). E-cigarette use in England 2014–17 as a function of socio-economic profile. Addiction, 114(2), 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14446

- Lekezwa, S., & Zulu, V. M. (2023). Critical factors in the innovation adoption of heated tobacco products consumption in an emerging economy. International Journal of Innovation Science, 15(2), 302–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-10-2021-0187

- Levine, H., Duan, Z., Bar-Zeev, Y., Abroms, L. C., Khayat, A., Tosakoon, S., Romm, K. F., Wang, Y., & Berg, C. J. (2023). IQOS use and interest by sociodemographic and tobacco behavior characteristics among adults in the US and Israel. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043141

- Lim, C. C. W., Leung, J. K. Y., Gravely, S., Gartner, C., Sun, T., Chiu, V., Chung, J. Y. C., Stjepanović, D., Connor, J., Scheurer, R. W., Hall, W., & Chan, G. C. K. (2023). A latent class analysis of patterns of tobacco and cannabis use in Australia and their health-related correlates. Drug and Alcohol Review, 42(4), 815–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13614

- Maziak, W., Taleb, Z. B., Bahelah, R., Islam, F., Jaber, R., Auf, R., & Salloum, R. G. (2015). The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tobacco Control, 24(Suppl 1), i3–i12. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051903

- Mistry, R., Bondarenko, I., Jeon, J., Brouwer, A. F., Mattingly, D. T., Hirschtick, J. L., Jimenez-Mendoza, E., Levy, D. T., Land, S. R., Elliott, M. R., Taylor, J. M. G., Meza, R., & Fleischer, N. L. (2021). Latent class analysis of use frequencies for multiple tobacco products in US adults. Preventive Medicine, 153, 106762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106762

- Mohan, P., Lando, H. A., & Panneer, S. (2018). Assessment of tobacco consumption and control in India. Indian Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9, 1179916118759289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179916118759289

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Nyman, A. L., Weaver, S. R., Popova, L., Pechacek, T. F., Huang, J., Ashley, D. L., & Eriksen, M. P. (2018). Awareness and use of heated tobacco products among US adults, 2016-2017. Tobacco Control, 27(Suppl 1), s55–s61. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054323

- Phan, L., Strasser, A. A., Johnson, A. C., Villanti, A. C., Niaura, R., Rehberg, K., & Mays, D. (2020). Young adult correlates of IQOS curiosity, interest, and likelihood of use. Tobacco Regulatory Science, 6(2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.18001/trs.6.2.1

- Rodzlan Hasani, W. S., Robert Lourdes, T. G., Ganapathy, S. S., Ab Majid, N. L., Abd Hamid, H. A., & Mohd Yusoff, M. F. (2023). Patterns of polysubstance use among adults in Malaysia – a latent class analysis. PLoS One, 18(1), e0264593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264593

- Rogers, E. M. (2002). Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addictive Behaviors, 27(6), 989–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(02)00300-3

- Rosen, L., Kislev, S., Bar-Zeev, Y., & Levine, H. (2020). Historic tobacco legislation in Israel: A moment to celebrate. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-4015-1-1

- Rosen, L. J., & Peled-Raz, M. (2015). Tobacco policy in Israel: 1948-2014 and beyond. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research, 4(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-015-0007-x

- Sun, L. (2017). A Foolish Take: Which companies control the U.S. tobacco market? USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/markets/2017/05/09/a-foolish-take-which-companies-control-the-us-tobacco-market/101157434/.

- Tattan-Birch, H., Jackson, S. E., Dockrell, M., & Brown, J. (2022). Tobacco-free nicotine pouch use in Great Britain: A representative population survey 2020-2021. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 24(9), 1509–1512. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntac099

- Tripathy, J. P., & Maha Lakshmi, P. V. (2023). Patterns of tobacco or nicotine-based product use and their quitting behaviour among adults in India: A latent class analysis. Public Health, 214, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.10.023

- Truth Initiative. (2021). Local restrictions on flavored tobacco and e-cigarette products. Truth Initiative. Retrieved November 26, 2021, from https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/local-restrictions-flavored-tobacco-and-e-cigarette.

- US Census Bureau. (2021). Current population survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data/datasets.html.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2019). Tobacco products: Vaporizers, E-cigarettes, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/labeling/productsingredientscomponents/ucm456610.htm.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2020a). FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2020b). Tobacco 21. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/retail-sales-tobacco-products/tobacco-21.

- US Food and Drug Administration. (2020c). FDA authorizes marketing of IQOS tobacco heating system with ‘reduced exposure’ information. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-iqos-tobacco-heating-system-reduced-exposure-information.

- Vardavas, C. I., Filippidis, F. T., & Agaku, I. T. (2015). Determinants and prevalence of e-cigarette use throughout the European union: A secondary analysis of 26 566 youth and adults from 27 countries. Tobacco Control, 24(5), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051394

- Vrieze, S. I. (2012). Model selection and psychological theory: A discussion of the differences between the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Psychological Methods, 17(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027127

- Wootliff, R. (2019). Knesset stubs out ads for cigarettes with ‘historic, life-saving’ law. Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/knesset-stubs-out-ads-for-cigarettes-with-historic-life-saving-law/.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Tobacco fact sheet. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco.

- Yi, J., Lee, C. M., Hwang, S. S., & Cho, S. I. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of heated tobacco products use among male ever smokers: Results from a Korean longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10344-4