ABSTRACT

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck and China reported the first case to the World Health Organization in December 2019, there was no evidence-based treatment to combat it. With the catastrophic situation that followed, materialised by a considerable number of deaths, researchers, doctors, traditional healers, and governments of all nations committed themselves to find therapeutic solutions, including preventive and curative. There are effective treatments offered both by modern medicine and traditional medicine for COVID-19 today. However, other therapeutic proposals have not been approved due to the lack of effectiveness and scientific rigour during their development process. Proponents of modern medicine prefer biomedical therapies while in some countries, traditional treatments are used regularly because of their availability, affordability and satisfaction they bring to the population. In this paper, we propose a transactional medicine approach where the interaction between traditional and modern medicine produces a change. With this approach, the promoters of traditional medicine and those of modern medicine will be able to acquire knowledge through the experience produced by their encounters. Transactional medicine aims to be a model for decolonising medicine and recognising the value of both traditional and modern medicine in the fight against COVID-19 and other global emerging pathogens.

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the first case being confirmed in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, there have been the urgency to identify effective treatment strategies, and there have been several therapeutic proposals to fight against COVID-19 both in traditional medicine and in biomedicine.Footnote1 This urgency is understandable given the fast evolution of the pandemic and the high number of cases and deaths worldwide. As of November 13, 2022, the COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update of the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 632,179,816 confirmed cases and 6,590,768 deaths. Africa with 174,811 deaths had the lowest number of reported deaths compared to other regions of the world (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Others claim that this mortality is underreported (Impouma et al., Citation2022). Vaccines have been a prophylactic measure against the spread of COVID-19; however, the data available show inequitable access to vaccination. The Africa CDC Vaccination dashboard, as of November 21, 2022, reported that only 24.1% of the African population was fully vaccinated (Africa CDC, Citation2022). As of October 5, 2022, when the Bloomberg Vaccine Tracker ceased to be updated, the vaccination rate was 73.6% in Europe, 67% in the United States, 84.7% in Australia, and 89.8% in mainland China (Bloomberg, Citation2022). Other therapeutic proposals have been made but some of them have not been approved by the WHO (Arukwe, Citation2022; Attah et al., Citation2021; Boro & Stoll, Citation2022). Yet treatments based on scientific evidence or nonscientific measures continue to be used to fight COVID-19 (Brüssow & Zuber, Citation2022) in some countries. However, it is difficult to convince people to use traditional medicine without scientific evidence; instead, people want a scientific approach to the development of herbal drugs (Yang, Citation2020). For example, the WHO, the repository of global health legitimacy, has refrained from endorsing Madagascar’s COVID-Organics as a miracle cure for COVID-19 and values only evidence-based claims with satisfactory efficacy and safety margins obtained via clinical trials (Attah et al., Citation2021). In a recent report, the WHO repeated the urgent need for better data to strengthen the world’s response to the pandemic and improve health outcomes. The implementation of the WHO’s Survey, Count, Optimize, Review, and Enable technical tool for health data aligns with the need to avoid any illusion of promoting nonscientific practices (World Health Organization, Citation2021). However, it would not be heuristic to establish a form of hierarchy of medical knowledge because a certain reality of modern medicine has originated from the flanks of traditional medicine. It would not be pragmatic to underestimate the contribution of traditional medicine to the development of modern medicine and its present contribution to the maintenance of people’s health. For example, according to the WHO, 25% of modern medicines are prepared from plants that were originally used traditionally (Rees, Citation2011). Also, at the level of medical practices, randomised studies have shown the contribution of traditional medicine in the management of certain pathologies. This is notably the case in the management of type 2 diabetes, where it has been shown that certain medicinal plants used in Ayurvedic medicine can help regulate blood sugar levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (Chattopadhyay et al., Citation2022). In addition, the scientific fact that is central to evidence is produced in a context that can be influenced by sociocultural values and factors (Pirozhkova, Citation2022). How did it happen that traditional medicine became a second-class medicine because of the primacy of modern medicine? Is it because of its static nature that it does not evolve toward evidence-based medicine?

The WHO’s approach to promoting evidence-based health research is not always followed because sometimes the sociocultural contexts of the countries, their health beliefs, availability, and poor experiences with biomedicine make local populations prefer traditional medicine as an alternative (Gyasi et al., Citation2016). Alternatively, some are reluctant to use traditional medicine due to the fact that they perceive it as less safe and effective than biomedicine and also claim that it is demonic (James et al., Citation2018). Occasionally, local populations are suspicious of biomedicine because of its scientific nature which is perceived as nonhumanistic – as not considering the patient’s experience and as technical, impersonal, and careless (Chan et al., Citation2016; Kriel, Citation2000). Sometimes patients have complete confidence in biomedicine because of its rapid effectiveness in terms of the positive effects of the treatments it offers (Chan et al., Citation2016). Faced with these conflicting points of view concerning the perspectives on traditional medicine and biomedicine, it is important to question the relevance of the therapies proposed by these two types of medicines.

During the past 2 years, researchers have conducted several studies (in vitro, animal models, and clinical practice) to find effective solutions against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studies have shown that different effective measures would be needed to enrich the defense arsenals and reduce the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. These measures would emphasize a holistic approach that would combine different factors to provide effective responses to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. A holistic approach is primarily the consideration when studying the vaccine efficacy of host genetic and environmental factors including age, biological sex, diet, geographic location, microbiome composition, and metabolites (Tomalka et al., Citation2022). Also, the study of the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and small molecule inhibitors has shown the importance of small molecule inhibitors in containing and potentially weakening the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 (Kolarič et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2021; Wang & Yang, Citation2022). Among the elements that could play a central role in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2, bioactive natural products would be an essential component in the treatment of pulmonary diseases. Research has shown that natural products could be applied in vitro as monotherapies for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 through ginkgolic acid, resveratrol, and baicalein (Yang & Wang, Citation2021). L. Yang and Wang (Citation2021) emphasized that natural products could serve as a starting point for further drug development in the treatment of COVID-19. Other relatively recent work has also shown the potential role of many natural products in the treatment of COVID-19. In particular, Z. Wang et al. (Citation2022) based on a review of studies published from May 2021 to April 2022 on bioactive natural products isolated from medicinal plants, animal products, and marine organisms in the in vitro treatment of COVID-19, demonstrated promising results in the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Although natural products would be an essential response to the treatment of SARS-CoV-2, Wang and Yang (Citation2021) highlighted the recognition of Chinese medicinal plants as key components of the COVID-19 treatment regimen because of their remarkable role in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection since January 2020 and contribution to the containment of the epidemic in China. Similarly, van de Sand et al. (Citation2021) mentioned that glycyrrhizin with its antiviral activity shows promising results in the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. These advances give hope for an effective fight COVID-19, but promising drugs to fight SARS-CoV-2 are not yet available (Wang & Yang, Citation2020, Citation2022).

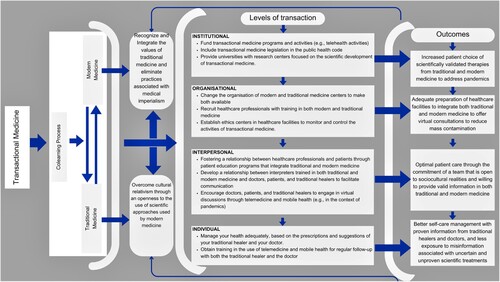

Based on the therapeutic initiatives mobilising these two medicines, the originality of our article is that it emphasizes the importance of transactional medicine in the fight for global health. In this sense, we propose a transactional medical approach built on 4 levels of transaction: institutional, organisational, interpersonal, individual. Our approach points out the challenges related to its implementation, even if we foresee the possible limitation of discussions of the comparison between the practices in the two schools of thought and believe it would be more beneficial to go in the direction of a transactional medicine as the WHO calls for an alignment of traditional medicine with Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) (World Health Organization, Citation2013). Indeed, the transactional medicine for COVID-19 that we propose in this article, as a response to WHO’s call, goes beyond the superimposition of traditional and biomedical practices. Our approach differs from the integrative medicine often confused alternative and complementary or characterised by a one-way relationship where traditional medicine integrates the scientific approach of modern medicine (Hu et al., Citation2015). Our approach is part of a dialogical approach between traditional medicine and modern medicine based on a transaction (i.e. mutual learning between the groups promoting traditional medicine and modern medicine, respectively) and on scientific foundations. Thus, transactional medicine makes sense in the conduct of institutional and organisational actions, interpersonal care relationships, and individual management of care taken to eliminate the dominance of modern medicine over traditional medicine. This approach should allow for greater treatment adherence in populations fighting COVID-19. We argue for hybridisation of knowledge to promote cross-cultural dialogue, bridge the knowledge gap, and improve initiatives to maintain good health. Indeed, as African researchers who have observed the way modern medicine is brought to the fore in our countries with little consideration of the value of traditional medicine, we propose this reflection to address this bias of lack of consideration of traditional medicine before modern medicine.

Examples of the use of biomedicine and traditional medicine in the context of COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, biomedicine and traditional medicine offered solutions to treat infected persons. The engagement of countries all around the world result from the fact that the outbreak caused the death of millions of people. To end this situation, researchers and promoters of both biomedicine and traditional medicine made proposals.

Biomedicine’s therapeutic proposals against COVID-19

The first therapeutic proposals that have been tested to combat COVID-19 have shown promise even if later on some of them will be at the origin of controversies because of the lack of scientific evidence as to their effectiveness. We mention a few examples here. Biswas et al. (Citation2021) listed a number of them, namely remdesivir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, azithromycin, lopinavir/ritonavir, chloroquine, baricitinib and cepharanthine. They also mentioned plasma therapies to treat patients and prevent severe phases that can lead to death. As the search for a cure for the pandemic has not subsided, effective treatments have been proposed for COVID-19 as shown in recent studies. These treatments are administered in different contexts of the management of patients with COVID-19. For example, a study conducted by Gupta et al. (Citation2021) showed that sotrovimab reduced the progression of COVID-19 in high-risk patients with mild to moderate Covid-19. Another study conducted by Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD) and reported by Mahase (Citation2021) found that the antiviral drug molnupiravir reduced the risk of hospital admission or death by approximately 50% in nonhospitalized adults with mild-to-moderate covid-19 at risk for poor outcomes. Similarly, the RECOVERY Collaborative group and other investigators proposed dexamethasone as an effective treatment for COVID-19 in an open-label controlled trial comparing a range of treatment options in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (Horby et al., Citation2021). Although promising, drug therapy proposals lack the evidence to prove their effectiveness in controlling COVID-19 and some populations, particularly those in countries with limited access to biomedicine, have turned to traditional medicine as a way to fight COVID-19 (Lasco & Yu, Citation2022). We present below some drugs and vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used to fight COVID-19 ( and ).

Table 1. Drugs used to fight against COVID-19.

Table 2. Vaccines approved by the FDA.

The treatment of COVID-19 by plants

Before the development of the pharmaceutical industry, plants were used during the occurrence of pandemics or as alternatives to existing treatments for certain infectious diseases. Plants still continue to be used as treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Garcia (Citation2020) reviewed the plants that have been used to fight some of the pandemics that have marked history before presenting some remedies against COVID-19, to fight the Black Death, smallpox, tuberculosis, malaria, and Spanish flu. For example, to fight the Black Death, she reports, citing Gattefossé (Citation1937) the use of remedy of the ‘the four thieves vinegar’ remedy by brewing in vinegar the following herbs: angelica (Angelica archangelica), camphor (Cinnamomum camphora), cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), garlic (Allium sativum), marjoram (Origanum majorana), meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), and sage (Salvia officinalis) and applying it on hands and face for avoiding contraction of the plague. Concerning the control of COVID-19, Garcia reports the use of quinine and its derivatives chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. More focused on COVID-19, Sytar et al. (Citation2021) listed in a review, remedies extracted from tree or plant parts (e.g. fruits, roots, barks, seeds, leaves, oleo-resin, flowers, Trehala manna, bulbs, Inflorescences, Rhizomes) that have antiviral activity that may contribute to the fight against COVID-19. Also, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in combination with Western medicine has made important contributions in the battle against COVID-19. For example, Artemisia annua, Lianhua Qingwen and Jinhua Qinggan granules have been proven effective in prevention and treatment of COVID-19 (An et al., Citation2021; Fuzimoto, Citation2021; Huang et al., Citation2021; Lyu et al., Citation2021; D. C. Wang et al., Citation2022). Other medicinal plants have been used to prevent or treat COVID-19. We referred to the herbs listed by Khadka et al. (Citation2021) for prevention of COVID-19 and those promoted by Phumthum et al. (Citation2021) to inform the reality of the use of herbs in fighting COVID-19.

Although these reviews point to the importance of plants in the management of infectious diseases, they all lack clinical evidence. The use of traditional medicine is, in fact, criticised for its lack of reference to solid evidence (James et al., Citation2018; Sytar et al., Citation2021).

Modern medicine and traditional medicine still face challenges due to limitations in the fight against COVID-19. We note some of the challenges in relation to the perception of their effectiveness and the way they are mobilised in the following lines. However, the fact there have been many proven treatments against COVID-19 across the world emphasize the importance of giving due consideration to other medical traditions in the fight against global emerging diseases like COVID-19 ().

Table 3. Medicinal Plants in the fight against COVID-19.

Challenges related to the use of modern medicine and traditional medicine in the era of COVID-19 pandemic

Modern medicine – characterised by its reference to EBM and Western medicine (Calvet-Mir et al., Citation2008) – has limitations. For example, even if modern medicine contributes to reducing infant mortality, improving people’s quality of life, increasing longevity, and finding cures for infectious diseases, it is more palliative and has not yet found cures for some diseases (Singh, Citation2010). Moreover, randomised clinical trials are not always appropriate for patients who experience serious health problems. Evidence for the treatment of a disease may be generalised to all patients (Lefkowitz & Jefferson, Citation2014). Regarding limits of EBM, we may observe controversies concerning therapeutic proposals to treat certain diseases, and the COVID-19 pandemic confirms this phenomenon. For example, reservations have been raised about COVID-19 vaccines regarding their production and implementation time. Some vaccines such as those for pneumonia, polio, and typhoid took ten years to be approved, whereas the COVID-19 vaccines were authorised in less than one year (Kaul, Citation2021).

In addition, people have reported serious side effects after receiving COVID-19 vaccines (Halim et al., Citation2021; Kaul, Citation2021). For example, a study by (Klugar et al., Citation2021) reported several side effects related to the injection of mRNA-based vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) and viral vector-based COVID-19 vaccines (AstraZeneca) among German healthcare workers. We list some of the side effects here: fever, chills, headache/fatigue, muscle pain, joint pain, nausea, malaise, vesicles, ulcers, rash, urticaria. Because of their implementation in such a short time, the long-term side effects are unknown (Forni & Mantovani, Citation2021). This active debate about the efficacy of proposed COVID-19 treatments raises questions about an apparent orientation toward modern medicine that is still uncertain for COVID-19. Disassociating himself from imperialist medicine, Dew (Citation2021), a health sociologist conducting his research in New Zealand, underscores that traditional medicine could move toward a different science rather than stand on the one upon which modern medicine is based. Such a proposal is understandable if we can define traditional medicine clearly. According to the World Health Organization (Citation2013), traditional medicine

is the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement, or treatment of physical and mental illness. (p. 15)

COVID-19 and the primacy of modern medicine over traditional medicine

Recently, an alignment with a scientific approach recognised by modern medicine in the fight against COVID-19 has characterised traditional medicine to combat the disease. Traditional medicines have proven to be effective; as Lee et al. (Citation2021) indicated, TCM ‘used in Wuhan showed 89% to 92% efficacies in 692 studies registered on Clinical Trial.gov’ (p. 2). The authors added that although effective, such medicines are under investigated or misunderstood. However, the effectiveness of TCM is still questioned because its applications are considered unproved (Dai et al., Citation2022). Arguably, this situation could be due to minimisation by modern medicine that has closed itself to the practices of other forms of medicine. Traditional medicine in Africa is also following this scientific approach with promising studies, although the situation is progressing slowly (Yimer et al., Citation2021). However, treatments proposed by traditional medicine that do not conform to the scientific approach are not recognised, although in some African countries, there has been some public recognition of traditional solutions against COVID-19. In Cameroon, for example, the Ministry of Public Health officially approved several local therapies because of their efficacy against COVID-19; two of the most prominent are Adsak COVID and Elixir COVID, which the Archbishop of Douala, Samuel Kleda, promotes. However, these herbal solutions are considered adjuvant treatments and have not achieved the same level of verification despite their proven efficacy against COVID-19. Decision No. D23-1164/L/MINSANTE/SG/DPML/ in Yaoundé approved these treatments for use on July 8, 2021 (Attah et al., Citation2021).

Even if this situation goes in the direction of curbing the domination of modern medicine by practitioners considering the value of traditional medicine, a race toward modernity will still exist in some developing countries. Seduced by advanced technology that developed countries use to treat diseases, some developing countries are adopting revolutionary new modes of treatment. The urgency of the current situation, manifested by the difficulties that some vaccines have in controlling certain COVID-19 variants (Duong, Citation2021), should push Western researchers to show epistemic humility by realising they do not know everything (Koloroutis & Trout, Citation2012) and to be open to other ways of dealing with the pandemic and diseases in general. Practitioners in developing countries and their institutional or political leaders turn elsewhere to find funding to develop medical methods while omitting or minimising the contribution of local therapies. For this reason, there is no serious research on traditional medicine as a means to win the fight against certain diseases. This rejection of traditional medicine compared to modern medicine evokes moral imperialism that can be defined as ‘the exportation of moral standards from one culture to another; usually from a politically, economically, and culturally dominant group to weaker groups as universally applicable to all persons and cultures’ (Tosam, Citation2020, p. 614). In this article, we use the term moral imperialism to refer to the imposition of Western views and values on other cultures in the context of COVID-19 treatment. Notably, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, any treatment not scientifically proven per the methods of modern medicine is considered inferior. Traditional healers have proposed various traditional herbal treatments, but most scientists remain sceptical. Although some proposals have limitations, others have been discarded before their efficacy could be judged. Controversies remain with the WHO being judged as following the colonial agenda because of its refusal to recognise the efficacy of therapeutic proposals from traditional medicine (Sibanda et al., Citation2022), on the one hand, and the WHO regional office for Africa conditioning the use of traditional medicine against COVID-19 to the conduct of clinical trials with scientific rigour (de Loera, Citation2022) on the other hand. We wonder where this disregard or indifference toward traditional medicine originates. It may be the result of political institutions that have not taken up the challenge of promoting research on traditional medicine to assert its usefulness and value in the eyes of other cultures. It may be intellectual alienation by the medical and political elite, who have been seduced by ‘superiorist biomedicine’ and who ignore the contributions that local medicines may bring to solving certain health problems. It is not a matter of ignoring the value of modern medicine but of giving voice to traditional medicine from a collaborative and complementary perspective. For example, Tangwa (Citation2007) condemns those who believe traditional medicine must align with modern medicine; he notes that at Cameroon’s Shishong Hospital, doctors refer their patients to traditional healers for diseases that cannot be cured. An international nongovernmental organisation (NGO) in Senegal, PROMETRA, is focused on the promotion of medicine and treatments from Africa. Its objective is to preserve African traditional medicine and to increase collaboration. Traditional healers are also trained in some concepts of modern medicine (Faye, Citation2011). Even when there is a willingness to listen to traditional healers, there are systemic limits to the achievement of this recognition. For example, African scientists do not have sufficient support from their governments to conduct research on local problems; instead, Western endowments fund them, and by accepting such funds, they contribute to continuing Western medicine’s domination and hegemony (Tangwa, Citation2017).

However, the collaboration between traditional medicine and modern medicine or traditional medicine practices in developed countries where modern medicine was created is a reality. Indeed, a French family doctor reveals that he adds homeopathy to his medical prescriptions for patients to treat COVID-19 (Payrau, Citation2021). Similarly, the combination of TCM based on clinical practice with modern medicine offers promising results in preventing and combating COVID-19 (Wu et al., Citation2021). In 2002, the WHO highlighted the importance of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicines in many developing and developed countries. In some African countries, 80% of the population use traditional medicine; according to Sarman and Uzuntarla (Citation2022), they are also used in some developed countries, with 69% of the population in Australia, 35% of the population in the United States, and 73% of the population in Canada using them. The explanations given in these countries for using alternative medicine include concerns about the harmful effects of chemical drugs (World Health Organization, Citation2002).

Because the interdependence between traditional medicine and modern medicine is beneficial, we believe we need a colearning process through a transactional approach to benefit fully from these two methods of medicine. In the following section, we define the transactional approach and how to focus it to fight global emerging pathogens.

Drawbacks, challenges, and potential solutions of transactional medicine

On the basis of the advantages and disadvantages of the two types of medicine, namely, traditional and modern medicine, as well as the observation that modern medicine does not allow traditional medicine to assert itself or that traditional medicine struggles to adopt a scientific approach to better contribute to the current health challenges, we propose potential solutions based on four levels of transactional medicine to map out the path that transactional medicine should take. Before we present our approach, we will describe what we mean by transactional medicine and then discuss the drawbacks and the challenges that can hinder its effectiveness.

Transactional medicine

From American philosopher Dewey’s (Citation1997) perspective, the word transaction suggests mutual or colearning in which participants learn from one another. Dewey’s approach advocates for positive changes through sharing experiences. This learning is transformative and the result of positively considering others’ values. More specifically, Dewey (Citation1989) defined a transaction as ‘that point of view which systematically proceeds upon the grounds that knowing is co-operative and, as such, is integral with communication’ (p. 4). By referring to this definition, we mean by Transactional medicine an approach whose objective is to fight medical imperialism in the approach to managing global emerging pathogens. In this sense, the issue is not targeted against modern medicine, which contributes to people’s quality of life worldwide. The goal of transactional medicine is to bring modern medicine and traditional medicine to grow together through a process of colearning to enable patients to make optimal use of both medicines through scientifically valid innovative practices and approaches that are not blind to sociocultural realities and are supported by institutional, organisational, interpersonal and individual strategies. With the recognition and valorisation of such an approach, it would not be an exaggeration to say that Dewey’s perspective of acquiring knowledge is not different from the perspectives of some African scholars advocating scientific procedures that align with African sociocultural realities. We thus call for a transaction between traditional and modern medicine by disassociating ourselves from a Western vision of the management of COVID-19 that overrides all other proposals – including those of traditional medicine – to manage the pandemic. The ways some populations interact with their environment to protect themselves against COVID-19 are socioculturally embedded. They differ from the ways Western populations manage COVID-19.

From a transactional perspective, the epistemic humility of people promoting modern medical knowledge that does not impose itself but recognises the value of other medical practices is a starting point. There is a need for acknowledgement of the contribution of cultures using traditional medicine to support the well-being of many people because they too are involved in managing a disease that affects all of humanity. For the transactional medicine model to work, modern medicine must be open to traditional medical practices. Transactional medicine is a way of saying that the interaction between traditional and modern medicine produces a change in that the promoters of traditional medicine and those of modern medicine acquire knowledge through the experience produced by these encounters (Biesta, Citation2014).

As Parrish et al. (Citation2011) noted, ‘openness admits of dependency on others – but also an interdependency and social capacity that demonstrates personal commitment to the experience as well’ (p. 19). In addition, the transactional medicine model presents as a critique against coloniality, which sees Western science as the most credible approach (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2020) alongside a recognition of the positive impact of traditional medicine. We must avoid thinking that modern medicine is the only medicine capable of saving humanity, and we must avoid imposing one approach through mechanisms of rigour that, until now, have not called into question the limits of this medicine. Doing so is equivalent to wanting to govern bodies that have never asked for it and to deny others the autonomy of action promoted in most Western health care systems. Transactional medicine that we advocate goes against a vertical relationship that favours modern medicine medicine as determined by a Western worldview and against the practice of a traditional medicine as expression of cultural relativism that refuses to recognise and exploit the scientific methods used by modern medicine. We detail our approach through the four levels of transaction that we propose below.

Potential solutions of transactional medicine through the four levels of transaction

We distinguish four levels for the deployment of transactional medicine: institutional, organisational, interpersonal, and individual ().

Institutional level of transaction

The first level is an institutional level where the elements of reflection on the transactional medicine must be incorporated through health governance policies and legal provisions in the health field. For example, in addition to the rules for the practice of hospital medicine, legal provisions for the practice of traditional medicine could be integrated into the public health code. In concrete terms, this transactional approach would of course involve putting the practice of traditional medicine in order by creating schools for such practice, as is done in certain countries, such as in Asia, where the scientific approach is emphasised (Chen et al., Citation2015). The training system in traditional medicine borrows its methods from modern medicine, and moreover doctors also train in traditional medicine, as in Japan, where they become Kampo specialists (Park et al., Citation2016). We could go further in this practice of traditional medicine in a more orderly framework, implying a consideration of its scientific approach through the establishment of theoretical, methodological, and conceptual development centres that borrow from modern science their tools and scientific approach. Paranormal medicine could take this path because promising results to evaluate it are available (Bluemke et al., Citation2016). As traditional medicine finds order through borrowing approaches from modern medicine, so must modern medicine integrate traditional medicine into its courses and doctor training. This approach to modern medicine helps us find a solution to a perspective that traditional healers hold toward doctors, namely, that for traditional healers, doctors underestimate them or do not value their practices, relegating them to a secondary status. By integrating traditional medicine, such as the study of plants used by traditional healers and their patients, doctors can negotiate with patients which traditional healing practices to allow and which to reject or discuss alternatives. The transactional approach occurs in a process whereby science is not neutered; however, in cases where science is subjective, there is a refusal to embody Western domination through medical imperialism. It should include a commitment by African political institutions to promote and fund research programmes on traditional medicine that focus on evidence as perceived and considered by traditional healers, not on evidence as modelled by Western protocols that have an imperialist agenda. Transactional medicine through training allows for mutual appreciation and comprehensive patient care. In addition, at the institutional level, the outcome of transactional medicine is the promotion of a greater choice of scientifically validated therapies from traditional medicine and modern medicine to deal with pandemics.

Organisational level of transaction

At the organisational level, hospital structures are often limited to medical care oriented toward a modern perspective of medicine. However, because the hospital is a stage in the patient’s journey, the patient can enter it after having consulted traditional healers (Xu & Xia, Citation2019). Some countries have set up structures where biomedicine and traditional medicine coexist. The Malango centre in Senegal is an example where there is a collaboration between doctors and traditional healers, and the traditional healers are trained in certain notions of biomedicine (Faye, Citation2011; Fokunang et al., Citation2011). Such structures would help doctors by making traditional healers their allies, allowing them to control the course of treatment and reduce the harm caused by charlatans who lack honesty. Learning from the qualities of traditional medicine can help biomedical experts not judge traditional medicine negatively concerning its scientific rigour. Following Dewey’s perspective, Hildreth (Citation2011) stated, ‘If a person gains a better sense of the meaning of experience and gains a greater sense of control over future experiences, they are better prepared to apply what they have learned flexibly in future situations’ (p. 34). An arrangement between traditional medicine and modern medicine reinforces trust in an institution that takes into consideration the sociocultural realities of patients while helping patients to dispel negative representations of modern medicine. Such structures are a form of transaction that translates into the recognition of the limits and qualities of each medicine, positively affecting the care given to the patient by allowing them to choose a complementary, solely traditional, or solely modern care approach. Practitioners for this must be trained, and this is made possible by an institutional approach on both sides that allows doctors as well as traditional healers to know their limits. Their contribution will come from knowing the specificities of each medicine in terms of approaches and the will to be part of a scientific approach while adopting an epistemic humility. For this to happen, financial resources are needed at the organisational level to set up these complementary care structures. In the context of a pandemic, transaction at an organisational level can foster a better preparation in health care facilities to offer both types of medicine and to consult virtually to reduce mass contamination by looking to unproven treatments or prevention against COVID-19.

Interpersonal level of transaction

To ensure a better approach to the management of care from a transactional perspective, one of the approaches that can be fruitful is the implementation of culturally oriented therapeutic education programmes; that is, education should not focus only on modern care practices. We do not doubt the contribution of these educational programmes, but if the patient continues to go to a traditional healer and follow advice that hinders the effectiveness of modern medicine, it is clear why the quality of care will not improve. Educational programmes must therefore, in addition to the presence of doctors and nurses, include traditional healers, psychologists, interpreters, insurers, and social workers. The reality is that in some African countries the literacy rate is low, and doctors may have difficulty explaining complex medical terms to patients (Pitt & Hendrickson, Citation2020), which is something that traditional healers can do because they use language that patients understand and give them more privacy (Muhamad et al., Citation2012). Therefore, interpreters are needed. Interpreters can be either caregivers or professionals who have been trained in the patient’s language (put at the institutional level for translation and/or the creation of language courses applied to medicine). During these therapeutic education sessions, the traditional healer can help patients find alternatives to the potions and remedies and explain why these can be harmful and how to find alternatives that can reconcile their taking of medications proposed by doctors and those proposed by a traditional healer. These therapeutic education sessions should be done by doctors who are knowledgeable in traditional medicine and by traditional healers who are knowledgeable in modern medicine. A transactional perspective where change is made is materialised by a respectful environment without thinking that the patient is not rational. The idea is to offer optimal care through which the patient can reconcile traditional and modern medicine without reducing the quality of care. The resources to do this are both interprofessional and interdisciplinary. If these sessions are collective, the fact that in certain societies people do not like to reveal traditional practices means that there is a possibility of organising individual sessions with the different actors already mentioned with an approach that consists of the professional actors with overlapping education proposing advice. A management plan that reconciles modern and traditional medicine would be effective. With a transactional process of combating COVID-19, optimal patient support is achieved thanks to a team open to sociocultural realities and ready to provide valid information on therapeutic proposals in both traditional and modern medicine.

Individual level of transaction

At the individual level – that is, in the management of the patient’s health – there is a better collaboration between the two medicine types and a practice that will not create a conflict of care. By conflict of care, we mean a consumption of both medicine types that harms health, rather than improving it, because of simultaneous and inefficient management by both care teams. Therefore, avoiding this conflict is one of the objectives of transactional medicine as well as a better empowerment of the patient and their family in the face of a sociocultural and modern context that offers a multitude of care options. For the doctor, there is a gain in systemic humility, a respect for the patient’s cultural care practices, and a better negotiation of care with the patient to allow for better care. There must be a dialogue with the patient on how to combine medicines from traditional medicine and those from modern medicine. Based on patient education sessions, some of which may be virtual in the case of pandemic, the transactional attitude will be based on evidence-based judgment. The transaction has a decision support function since it allows the individual to use either complementarity or a single medicine depending on the situation. In fact, the way in which the management of the health problem is done, results from ‘the goals, preferences, conditions, and constraints [that] emerge in the agent’s transactions with the rest of the functions that constitute the situation in which the transactions themselves constitute a participating subfunction’ (Mousavi & Garrison, Citation2003, p. 140). Thanks to transactional medicine, which promotes a more scientific approach to COVID-19 through a mutual appropriation between traditional and modern medicine, the agent has more tools to deal with misinformation about fake drugs, home remedies (Chavda et al., Citation2022).

Drawbacks of transactional medicine

Transactional medicine can produce an alignment of one medicine with another and erase cultural practice because of a need for a scientific approach modelled on modern medicine. In effect, it can rob communities of local health practices that have been carried out for millennia (Hosseinzadeh et al., Citation2015). Another disadvantage of this transactional medicine is that its normative aspect can lead to the use of both medicines, whereas treatment is sufficient only in the use of one medicine. In fact, even if there is advocacy for its development, the use of traditional medicine for certain diseases such as chronic illnesses are seen as potentially irrational (Pradipta et al., Citation2023). The distribution of funds for the financing of traditional medicine and the provision of hospitals with these structures can lead to not focusing on medical priorities, and some patients have more hope of being treated by modern medicine, particularly when traditional medicine is considered less profitable than modern medicine (Sugito & Son, Citation2019). Some governments may need to fund traditional medicine to address access to primary health care (Ijaz & Boon, Citation2018). However, if there is no balance in the distribution of funding, the management of certain serious diseases that are undergoing advanced scientific development may be left unattended. The time to set up training and to change the service system of traditional medicine and its integration into a modern medical system may be long and require a massive investment in terms of human and financial resources. To evolve in a modern dynamic following the same scientific approaches as modern medicine, traditional medicine faces the problem of long-term exposure effects (Fung & Wong, Citation2015). Moreover, with the training of traditional practitioners in modern medicine and doctors in traditional medicine, there is a risk of professional encroachment and of considering that one can prescribe in the place of the doctor or in the place of the traditional practitioner, which can be a risk for the health of the patient if control and accountability of the doctors and traditional practitioners is not enacted. Epistemic humility must go both ways to preserve the patient’s trust in modern medicine or in traditional medicine (Pietschmann & Mertz, Citation2020). The other negative consequence that this transactional medicine can cause is that the dialogue between traditional and modern medicine cannot have the expected effect or lead to conclusive actions. Indeed, the knowledge gained by experience (Biesta, Citation2014) can be limited by the lack of competences of agents involved in the transaction or their inability to meet the need of knowledge by the others to act and to improve their points of view. Another disadvantage of transactional medicine may be that it is not ready to integrate paranormal medicine or rather that some promoters of modern medicine do not take it into consideration. However, this supernatural medicine is now being investigated in Western countries. For example, the mathematician Joseph Banks Rhine, whose work on telepathy and extrasensory perception was recognised by the American Institute of Mathematical Statistics, has given the study of such phenomena and the results obtained a scientific status. Today, chairs exist in Western universities devoted to the research and teaching of so-called paranormal phenomena (Kloosterman, Citation2012).

Challenges to the effectiveness of transactional medicine

One of the first problems with the idea of borrowing structures for training in traditional medicine or developing a public health code by inviting the different actors to achieve the objective of transactional medicine is the fact that there are a huge number of traditional healers, and it would take time to organise or control them. The other challenge is that at the institutional level the resources are already insufficient for modern medicine, and the use of human and material resources is not sufficient because of lack of financial means. Adding the management of traditional medicine would be problematic given that modern medicine follows a scientific approach whereas traditional medicine does not. It would also cost some states to train traditional healers who have traditionally acquired their knowledge as a legacy. This lack of resources can also be pointed out at the organisational level. Hospitals often lack resources for their patients who use modern medicine. The integration of traditional medicine would require an upheaval of the organisation and new jobs that need to be funded. At the interpersonal level, one problem may be the reluctance of patients to share traditional care practices that are frowned upon by society. There is also the problem of understanding the technical terms used by physicians. Patients and their families may also accept a supernatural diagnosis of the disease and believe it is not only due to organic dysfunction. Another issue is the lack of epistemic humility and that practitioners may consider patients as irrational beings clinging to modern scientific medicine. Patients may be less oriented toward modern medicine and therefore less inclined to enrol in a transactional approach to care when they lack financial resources to take care of themselves in a hospital, whereas traditional healers are more socially accessible and financially affordable. Another challenge to face is the socialisation of medical students to traditional practices from a perspective of conciliation, complementarity, and mutual learning with biomedicine. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, an anticipatory approach could help dissipate some people’s concerns regarding vaccination. However, because it is never too late to set things right, we can reflect on transactional medicine to avoid cultural imperialism in the approach to managing COVID-19 in a global context. In this sense, modern medicine must grow by letting people freely choose traditional medicine that is scientifically validated. To approach scientifically the paranormal and the spiritual, Niang (Citation2020) mentioned the existence of a sub-quantum environment through which the psychic phenomena would be expressed, materialising by a relationship of interference and synchronisation between the researcher and the spiritual object of study. According to Niang, the researcher combines paranormal faculties, telepathic dispositions, and intuitive dispositions, which either favour or do not the coincidence between the hypothesis elaborated by the researcher and the reality that the researcher is going to discover. The scientific process of reflection on paranormal objects of study requires the researcher to have recourse to dispositions that allow them to approach the object and objectify it by following the scientific process. At the individual level, the problem of a poorly negotiated transaction where drugs and plants are taken without control can have harmful consequences for health (Izzo & Ernst, Citation2001).

Conclusion

Transactional medicine can help reduce the reluctance of non-Western populations to accept Western ways of managing COVID-19 medically. This also will help Western populations and scientists to stop imposing their views, consider the value of traditional medicine positively, and better trust the contributions of traditional medicine in fighting COVID-19. International collaboration and a wise and compassionate attitude could lead to a paradigm shift in which traditional medicine is better valued and the quality of patient care improved. Regarding the management of COVID-19, this approach would be beneficial in a context where countries around the world are struggling to find an effective treatment. Indeed, patients with good management of their health would, thanks to proven information received from traditional healers and doctors, be less subject to misinformation related to uncertain and unverified scientific treatments.

Acknowledgements

First, we would like to thank the reviewers for their pertinent criticisms and suggestions. We would also like to thank Dr. Eric Racine from Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal, Dr. Oyinlola Oyebode from University of Warwick, Krystal Tennessee from Université de Montréal, Dr. Jonathan Daw from Penn State University, Anne-Sophie Guernon from McGill University, Dr. Cynthia T. Cook from Creighton University, and Dr. Patrice Forrester from University of Maryland Baltimore for their helpful comments on an early draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In this article, we use interchangeably the notions of biomedicine and western medicine since western medicine is referred to as biomedicine (Boersma, Citation2020) and biomedicine is the dominant medical system in western countries (Ibeneme et al., Citation2017).

References

- Ader, F., Peiffer-Smadja, N., Poissy, J., Bouscambert-Duchamp, M., Belhadi, D., Diallo, A., Delmas, C., Saillard, J., Dechanet, A., Mercier, N., Dupont, A., Alfaiate, T., Lescure, F. X., Raffi, F., Goehringer, F., Kimmoun, A., Jaureguiberry, S., Reignier, J., Nseir, S., … Mentré, F. (2021). An open-label randomized controlled trial of the effect of lopinavir/ritonavir, lopinavir/ritonavir plus IFN-β-1a and hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 27(12), 1826–1837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.020

- Africa CDC. (2022, November 21). Africa CDC COVID-19 vaccine dashboard. Africa CDC. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://africacdc.org/covid-19-vaccination/

- An, X., Xu, X., Xiao, M., Min, X., Lyu, Y., Tian, J., Ke, J., Lang, S., Zhang, Q., Fan, A., Liu, B., Zhang, Y., Hu, Y., Zhou, Y., Shao, J., Li, X., Lian, F., & Tong, X. (2021). Efficacy of Jinhua Qinggan granules combined with Western medicine in the treatment of confirmed and suspected COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 728055. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.728055

- Arukwe, N. O. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic in Africa, “copy-and-paste” policies, and the biomedical hegemony of “cure”. Journal of Black Studies, 53(4), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219347221082327

- Attah, A. F., Fagbemi, A. A., Olubiyi, O., Dada-Adegbola, H., Oluwadotun, A., Elujoba, A., & Babalola, C. P. (2021). Therapeutic potentials of antiviral plants used in traditional African medicine with COVID-19 in focus: A Nigerian perspective. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 596855. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.596855

- Bansal, P., Goyal, A., Cusick, A. t., Lahan, S., Dhaliwal, H. S., Bhyan, P., Bhattad, P. B., Aslam, F., Ranka, S., Dalia, T., Chhabra, L., Sanghavi, D., Sonani, B., & Davis, J. M., 3rd. (2021). Hydroxychloroquine: A comprehensive review and its controversial role in coronavirus disease 2019. Annals of Medicine, 53(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2020.1839959

- Biesta, G. (2014). Pragmatising the curriculum: Bringing knowledge back into the curriculum conversation, but via pragmatism. The Curriculum Journal, 25(1), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2013.874954

- Biswas, P., Hasan, M. M., Dey, D., Dos Santos Costa, A. C., Polash, S. A., Bibi, S., Ferdous, N., Kaium, M. A., Rahman, M. D. H., Jeet, F. K., Papadakos, S., Islam, K., & Uddin, M. S. (2021). Candidate antiviral drugs for COVID-19 and their environmental implications: A comprehensive analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(42), 59570–59593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16096-3

- Bloomberg. (2022, October 5). Vaccine tracker. Bloomberg. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/

- Bluemke, M., Jong, J., Grevenstein, D., Mikloušić, I., & Halberstadt, J. (2016). Measuring cross-cultural supernatural beliefs with self- and peer-reports. PLoS ONE, 11(10), e0164291. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164291

- Boersma, K. A. (2020, July 16). RE: Is it time for a change in Western medicine? CMAJ. Retrieved November 16, 2022, from https://www.cmaj.ca/content/re-it-time-change-western-medicine

- Boro, E., & Stoll, B. (2022). Barriers to COVID-19 health products in low-and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review and evidence synthesis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 928065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.928065

- Boumy, K.-K. (2020). Le COVID organics et l’émergence des théories de l’Afro-charlatanisme; plaidoyer pour une hybridation des savoirs. Recherches & Educations, https://doi.org/10.4000/rechercheseducations.9906

- Brüssow, H., & Zuber, S. (2022). Can a combination of vaccination and face mask wearing contain the COVID-19 pandemic? Microbial Biotechnology, 15(3), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13997

- Calvet-Mir, L., Reyes-García, V., & Tanner, S. (2008). Is there a divide between local medicinal knowledge and Western medicine? A case study among native Amazonians in Bolivia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 4(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-4-18

- Chan, J. F., Yao, Y., Yeung, M. L., Deng, W., Bao, L., Jia, L., Li, F., Xiao, C., Gao, H., Yu, P., Cai, J. P., Chu, H., Zhou, J., Chen, H., Qin, C., & Yuen, K. Y. (2015). Treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir or interferon-β1b improves outcome of MERS-CoV infection in a nonhuman primate model of common marmoset. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 212(12), 1904–1913. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv392

- Chan, K., Siu, J. Y., & Fung, T. K. (2016). Perception of acupuncture among users and nonusers: A qualitative study. Health Marketing Quarterly, 33(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07359683.2016.1132051

- Chattopadhyay, K., Wang, H., Kaur, J., Nalbant, G., Almaqhawi, A., Kundakci, B., Panniyammakal, J., Heinrich, M., Lewis, S. A., Greenfield, S. M., Tandon, N., Biswas, T. K., Kinra, S., & Leonardi-Bee, J. (2022). Effectiveness and safety of ayurvedic medicines in type 2 diabetes mellitus management: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 821810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.821810

- Chavda, V. P., Sonak, S. S., Munshi, N. K., & Dhamade, P. N. (2022). Pseudoscience and fraudulent products for COVID-19 management. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(42), 62887–62912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21967-4

- Chen, L., Fu, Y., Zhang, L., Zhao, S., Feng, Q., Cheng, Y., Yanai, T., Xu, D., Luo, M., An, S. W., Lee, W. S., Cho, S. H., & Lee, B. W. (2015). Clinical application of traditional herbal medicine in five countries and regions: Japan; South Korea; Mainland China; Hong Kong, China; Taiwan, China. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences, 2(3), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcms.2016.01.004

- Dai, Z., Liao, X., Wieland, L. S., Hu, J., Wang, Y., Kim, T. H., Liu, J. P., Zhan, S., & Robinson, N. (2022). Cochrane systematic reviews on traditional Chinese medicine: What matters-the quantity or quality of evidence? Phytomedicine, 98, 153921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153921

- de Loera, D. (2022). The role of traditional medicine in the fight against SARS-CoV-2. In S. Rosales-Mendoza, M. Comas-Garcia, & O. Gonzalez-Ortega (Eds.), Biomedical innovations to combat COVID-19 (pp. 339–385). Elsevier.

- Dew, K. (2021). Complementary and alternative medicine: Containing and expanding therapeutic possibilities. Routledge.

- Dewey. (1989). The later works, 1925-1953: Volume 16: 1949-1952, essays, typescripts, and knowing and the known. Experience and nature. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. Simon & Schuster.

- Doi, Y., Hibino, M., Hase, R., Yamamoto, M., Kasamatsu, Y., Hirose, M., Mutoh, Y., Homma, Y., Terada, M., Ogawa, T., Kashizaki, F., Yokoyama, T., Koba, H., Kasahara, H., Yokota, K., Kato, H., Yoshida, J., Kita, T., Kato, Y., … Kondo, M. (2020). A prospective, randomized, open-label trial of early versus late favipiravir therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 64, 12. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01897-20

- Duong, D. (2021). Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma: What’s important to know about SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern? Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(27), E1059–E1060. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1095949

- Faye, S. L. (2011). Quand les tradithérapeutes ouest-africains soignent l’infertilité conjugale à Dakar (Sénégal): Recompositions et dynamiques entrepreneuriales. Anthropologie et Santé, 3. https://doi.org/10.4000/anthropologiesante.755

- Fokunang, C. N., Ndikum, V., Tabi, O. Y., Jiofack, R. B., Ngameni, B., Guedje, N. M., Tembe-Fokunang, E. A., Tomkins, P., Barkwan, S., Kechia, F., Asongalem, E., Ngoupayou, J., Torimiro, N. J., Gonsu, K. H., Sielinou, V., Ngadjui, B. T., Angwafor, F., Nkongmeneck, A., Abena, O. M., … Lohoue, J. (2011). Traditional medicine: Past, present and future research and development prospects and integration in the National Health System of Cameroon. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 8(3), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajtcam.v8i3.65276

- Forni, G., & Mantovani, A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccines: Where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death & Differentiation, 28(2), 626–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9

- Fung, H.-N., & Wong, C.-Y. (2015). Exploring the modernization process of traditional medicine: A Triple Helix perspective with insights from publication and trademark statistics. Social Science Information, 54(3), 327–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018415577504

- Fuzimoto, A. D. (2021). An overview of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of Artemisia annua, its antiviral action, protein-associated mechanisms, and repurposing for COVID-19 treatment. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 19(5), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.07.003

- Garcia, S. (2020). Pandemics and traditional plant-based remedies. A historical-botanical review in the era of COVID19. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 571042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.571042

- Gattefossé, R. M. (1937). Aromathérapie; les huiles essentielles hormones végétales. Girardot.

- Grein, J., Ohmagari, N., Shin, D., Diaz, G., Asperges, E., Castagna, A., Feldt, T., Green, G., Green, M. L., Lescure, F. X., Nicastri, E., Oda, R., Yo, K., Quiros-Roldan, E., Studemeister, A., Redinski, J., Ahmed, S., Bernett, J., Chelliah, D., … Flanigan, T. (2020). Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(24), 2327–2336. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2007016

- Gupta, A., Gonzalez-Rojas, Y., Juarez, E., Crespo Casal, M., Moya, J., Falci, D. R., Sarkis, E., Solis, J., Zheng, H., Scott, N., Cathcart, A. L., Hebner, C. M., Sager, J., Mogalian, E., Tipple, C., Peppercorn, A., Alexander, E., Pang, P. S., Free, A., … Shapiro, A. E. (2021). Early treatment for Covid-19 with SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody sotrovimab. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(21), 1941–1950. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2107934

- Gyasi, R. M., Asante, F., Abass, K., Yeboah, J. Y., Adu-Gyamfi, S., & Amoah, P. A. (2016). Do health beliefs explain traditional medical therapies utilisation? Evidence from Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 2(1), 1209995. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2016.1209995

- Gyasi, R. M., Mensah, C. M., Osei-Wusu Adjei, P., & Agyemang, S. (2011). Public perceptions of the role of traditional medicine in the health care delivery system in Ghana. Global Journal of Health Science, 3(2), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v3n2p40

- Halim, M., Halim, A., & Tjhin, Y. (2021). COVID-19 vaccination efficacy and safety literature review. Journal of Clinical and Medical Research, 3(1), 1–10.

- Hildreth, R. W. (2011). What good is growth?: Reconsidering Dewey on the ends of education. Education and Culture, 27(2), 28–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5703educationculture.27.2.28.

- Horby, P., Lim, W. S., Emberson, J. R., Mafham, M., Bell, J. L., Linsell, L., Staplin, N., Brightling, C., Ustianowski, A., Elmahi, E., Prudon, B., Green, C., Felton, T., Chadwick, D., Rege, K., Fegan, C., Chappell, L. C., Faust, S. N., Jaki, T., … Landray, M. J. (2021). Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

- Hosseinzadeh, S., Jafarikukhdan, A., Hosseini, A., & Armand, R. (2015). The application of medicinal plants in traditional and modern medicine: A review of Thymus vulgaris. International Journal of Clinical Medicine, 06((09|9)), 635–642. https://doi.org/10.4236/ijcm.2015.69084

- Hu, X.-Y., Lorenc, A., Kemper, K., Liu, J.-P., Adams, J., & Robinson, N. (2015). Defining integrative medicine in narrative and systematic reviews: A suggested checklist for reporting. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 7(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2014.11.006

- Huang, K., Zhang, P., Zhang, Z., Youn, J. Y., Wang, C., Zhang, H., & Cai, H. (2021). Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in the treatment of COVID-19 and other viral infections: Efficacies and mechanisms. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 225, 107843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107843

- Iaccarino, M. (2003). Science and culture. Western science could learn a thing or two from the way science is done in other cultures. EMBO Reports, 4(3), 220–223. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.embor781

- Ibeneme, S., Eni, G., Ezuma, A., & Fortwengel, G. (2017). Roads to health in developing countries: Understanding the intersection of culture and healing. Current Therapeutic Research, 86, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.curtheres.2017.03.001

- Ijaz, N., & Boon, H. (2018). Statutory regulation of traditional medicine practitioners and practices: The need for distinct policy making guidelines. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 24(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2017.0346

- Impouma, B., Carr, A. L. J., Spina, A., Mboussou, F., Ogundiran, O., Moussana, F., Williams, G. S., Wolfe, C. M., Farham, B., Flahault, A., Codeco Tores, C., Abbate, J. L., Coelho, F. C., & Keiser, O. (2022). Time to death and risk factors associated with mortality among COVID-19 cases in countries within the WHO African region in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology and Infection, 150, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026882100248X

- Izzo, A. A., & Ernst, E. (2001). Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: A systematic review. Drugs, 61(15), 2163–2175. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002

- James, P. B., Wardle, J., Steel, A., & Adams, J. (2018). Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e000895. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895

- Juhn, P., Phillips, A., & Buto, K. (2007). Balancing modern medical benefits and risks. Health Affairs, 26(3), 647–652. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.647

- Kaul, D. (2021). COVID-19 vaccines: Facts and controversies. Current Medicine Research and Practice, 11(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.4103/cmrp.cmrp_11_21

- Kenmogne, E. (2016). Maladies paranormales et rationalités: Contribution à l'épistémologie de la santé. L’Harmattan.

- Khadka, D., Dhamala, M. K., Li, F., Aryal, P. C., Magar, P. R., Bhatta, S., Thakur, M. S., Basnet, A., Cui, D., & Shi, S. (2021). The use of medicinal plants to prevent COVID-19 in Nepal. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 17(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-021-00449-w

- Kloosterman, I. (2012). Psychical research and parapsychology interpreted: Suggestions from the international historiography of psychical research and parapsychology for investigating its history in the Netherlands. History of the Human Sciences, 25(2), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695111421580

- Klugar, M., Riad, A., Mekhemar, M., Conrad, J., Buchbender, M., Howaldt, H. P., & Attia, S. (2021). Side effects of mRNA-based and viral vector-based COVID-19 vaccines among German healthcare workers. Biology, 10(8), 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10080752

- Kolarič, A., Jukič, M., & Bren, U. (2022). Novel small-molecule inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding to neuropilin 1. Pharmaceuticals, 15(2), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15020165

- Koloroutis, M., & Trout, M. D. (2012). See me as a person: Creating therapeutic relationships with patients and their families. Creative Health Care Management.

- Kriel, J. R. (2000). Matter, mind, and medicine: Transforming the clinical method. Rodopi.

- Lasco, G., & Yu, V. G. (2022). Pharmaceutical messianism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114567

- Lee, D. Y. W., Li, Q. Y., Liu, J., & Efferth, T. (2021). Traditional Chinese herbal medicine at the forefront battle against COVID-19: Clinical experience and scientific basis. Phytomedicine, 80, 153337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153337

- Lefkowitz, W., & Jefferson, T. C. (2014). Medicine at the limits of evidence: The fundamental limitation of the randomized clinical trial and the end of equipoise. Journal of Perinatology, 34(4), 249–251. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2013.172

- López-Medina, E., López, P., Hurtado, I. C., Dávalos, D. M., Ramirez, O., Martínez, E., Díazgranados, J. A., Oñate, J. M., Chavarriaga, H., Herrera, S., Parra, B., Libreros, G., Jaramillo, R., Avendaño, A. C., Toro, D. F., Torres, M., Lesmes, M. C., Rios, C. A., & Caicedo, I. (2021). Effect of ivermectin on time to resolution of symptoms among adults with mild COVID-19: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 325(14), 1426–1435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3071

- Lyu, M., Fan, G., Xiao, G., Wang, T., Xu, D., Gao, J., Ge, S., Li, Q., Ma, Y., Zhang, H., Wang, J., Cui, Y., Zhang, J., Zhu, Y., & Zhang, B. (2021). Traditional Chinese medicine in COVID-19. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 11(11), 3337–3363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.008

- Mahase, E. (2021). Covid-19: Molnupiravir reduces risk of hospital admission or death by 50% in patients at risk, MSD reports. BMJ, 375, n2422. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2422

- Makita-Ikouaya, E., Milleliri, J.-M., & Rudant, J.-P. (2010). Place de la médecine traditionnelle dans le système de soins des villes d'Afrique subsaharienne: Le cas de Libreville au Gabon. Cahiers d'Etudes et de Recherches Francophones/Santé, 20(4), 179–188.

- Mordeniz, C. (2019). Integration of traditional and complementary medicine into evidence-based clinical practice. In C. Mordeniz (Ed.), Traditional and complementary medicine (pp. 1–8). IntechOpen.

- Mousavi, S., & Garrison, J. (2003). Toward a transactional theory of decision making: Creative rationality as functional coordination in context. Journal of Economic Methodology, 10(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350178032000071039

- Muhamad, M., Merriam, S., & Suhami, N. (2012). Why breast cancer patients seek traditional healers. International Journal of Breast Cancer, 2012, 689168. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/689168

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. (2020). Diagnosis and treatment of corona virus disease-19 (8th trial edition). Chinese Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 13(5), 321–328.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2020). Geopolitics of power and knowledge in the COVID-19 pandemic: Decolonial reflections on a global crisis. Journal of Developing Societies, 36(4), 366–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X20963252

- Niang, A. (2020). Sciences et sixième sens : La physique des sub-quanta, les ondes de probabilité et le rôle de la paranormalité dans la créativité et la découverte scientifique. Revue Sénégalaise de Sociologie, 12, 9–39.

- Niang, A. (2021). Face à la COVID-19, la nécessité de la reprise du dialogue entre l’Islam et la science : Le cas des musulmans du Sénégal. In H. K. F. L. D. Seri, I. Kone, & A. Azalou-Tingbe (Eds.), Conscience historique et conscience sanitaire en Afrique. Qu'attendre des sciences sociales face à la COVID-19? (pp. 213–243). Presses de l'Université d'Abomey-Calavi (PUAC).

- Ning, A. M. (2013). How ‘alternative’ is CAM? Rethinking conventional dichotomies between biomedicine and complementary/alternative medicine. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 17(2), 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459312447252

- Nojomi, M., Yassin, Z., Keyvani, H., Makiani, M. J., Roham, M., Laali, A., Dehghan, N., Navaei, M., & Ranjbar, M. (2020). Effect of Arbidol (Umifenovir) on COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 954. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05698-w

- Park, Y. L., Huang, C. W., Sasaki, Y., Ko, Y., Park, S., & Ko, S. G. (2016). Comparative study on the education system of traditional medicine in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. Explore, 12(5), 375–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2016.06.004

- Parrish, P. E., Wilson, B. G., & Dunlap, J. C. (2011). Learning experience as transaction: A framework for instructional design. Educational Technology, 51(2), 15–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44429912.

- Payrau, B. (2021). Médecine intégrative et covid-19. Quel support l’homéopathie peut-elle proposer? Éléments de réponse fondés sur le témoignage d’un médecin praticien intégrant l’homéopathie à sa prescription. Hegel, 1(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.3917/heg.111.0019

- Phumthum, M., Nguanchoo, V., & Balslev, H. (2021). Medicinal plants used for treating mild Covid-19 symptoms among Thai Karen and Hmong. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 699897. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.699897

- Pietschmann, I. S., & Mertz, M. (2020). Humanisme médical et médecine complémentaire, alternative et intégrative. Archives de Philosophie, Tome 83(4), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.3917/aphi.834.0083

- Pirozhkova, S. V. (2022). Sociohumanistic knowledge and the future of science. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 92(2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1019331622020046

- Pitt, M. B., & Hendrickson, M. A. (2020). Eradicating jargon-oblivion—A proposed classification system of medical jargon. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(6), 1861–1864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05526-1

- Pradipta, I. S., Aprilio, K., Febriyanti, R. M., Ningsih, Y. F., Pratama, M. A. A., Indradi, R. B., Gatera, V. A., Alfian, S. D., Iskandarsyah, A., & Abdulah, R. (2023). Traditional medicine users in a treated chronic disease population: A cross-sectional study in Indonesia. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 23(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-023-03947-4

- Rees, L. A. (2011). Face aux défis des systèmes publics de santé, quel rôle pour la médecine traditionnelle dans les pays en développement? In D. Kerouedan (Ed.), Santé internationale (pp. 337–345). Presses de Sciences Po.

- Sanders, J. M., Monogue, M. L., Jodlowski, T. Z., & Cutrell, J. B. (2020). Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA, 323(18), 1824–1836. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6019

- Sarman, A., & Uzuntarla, Y. (2022). Attitudes of healthcare workers towards complementary and alternative medicine practices: A cross-sectional study in Turkey. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 49, 102096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2021.102096

- Sibanda, F., Muyambo, T., & Chitando, E. (2022). Introduction. Religion and public health in the shadow of COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Africa. In F. Sibanda, T. Muyambo, & E. Chitando (Eds.), Religion and the COVID-19 pandemic in Southern Africa (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- Singh, A. R. (2010). Modern medicine: Towards prevention, cure, well-being and longevity. Mens Sana Monographs, 8(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.58817

- Sorvig, K. H., Loveman, C., & Chiou, C. (2021, August 3). Lilly and Incyte’s baricitinib reduced deaths among patients with COVID-19 receiving invasive mechanical ventilation. Retrieved April 15, 2023, from https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-and-incytes-baricitinib-reduced-deaths-among-patients#:~:text=In%20this%20sub%2Dstudy%2C%20patients,%5BHR%5D%20%5B95%25%20CI

- Sugito, R., & Son, D. (2019). Obstacles to the use of complementary and alternative medicine by primary care physicians: Preliminary study. Traditional & Kampo Medicine, 6(3), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/tkm2.1225

- Sytar, O., Brestic, M., Hajihashemi, S., Skalicky, M., Kubeš, J., Lamilla-Tamayo, L., Ibrahimova, U., Ibadullayeva, S., & Landi, M. (2021). COVID-19 prophylaxis efforts based on natural antiviral plant extracts and their compounds. Molecules, 26(3), https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030727

- Tangwa, G. B. (2007). How not to compare Western scientific medicine with African traditional medicine. Developing World Bioethics, 7(1), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8847.2006.00182.x

- Tangwa, G. B. (2017). Giving voice to African thought in medical research ethics. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 38(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11017-017-9402-3

- Tomalka, J. A., Suthar, M. S., Deeks, S. G., & Sekaly, R. P. (2022). Fighting the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic requires a global approach to understanding the heterogeneity of vaccine responses. Nature Immunology, 23(3), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-022-01130-4

- Tosam, M. J. (2020). Global bioethics and respect for cultural diversity: How do we avoid moral relativism and moral imperialism? Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 23(4), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-020-09972-1

- van de Sand, L., Bormann, M., Alt, M., Schipper, L., Heilingloh, C. S., Steinmann, E., Todt, D., Dittmer, U., Elsner, C., Witzke, O., & Krawczyk, A. (2021). Glycyrrhizin effectively inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by inhibiting the viral main protease. Viruses, 13(4), 609, https://doi.org/10.3390/v13040609

- Wang, D. C., Yu, M., Xie, W. X., Huang, L. Y., Wei, J., & Lei, Y. H. (2022). Meta-analysis on the effect of combining Lianhua Qingwen with Western medicine to treat coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 20(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2021.10.005

- Wang, Z., Wang, N., Yang, L., & Song, X. Q. (2022). Bioactive natural products in COVID-19 therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 926507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.926507

- Wang, Z., & Yang, L. (2020). GS-5734: A potentially approved drug by FDA against SARS-Cov-2. New Journal of Chemistry, 44(29), 12417–12429. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0NJ02656E

- Wang, Z., & Yang, L. (2021). Chinese herbal medicine: Fighting SARS-CoV-2 infection on all fronts. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 270, 113869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2021.113869

- Wang, Z., & Yang, L. (2022). Broad-spectrum prodrugs with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities: Strategies, benefits, and challenges. Journal of Medical Virology, 94(4), 1373–1390. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27517

- Wang, Z., Yang, L., & Zhao, X.-E. (2021). Co-crystallization and structure determination: An effective direction for anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug discovery. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 19, 4684–4701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.08.029

- World Health Organization. (2002). Stratégie de l’OMS pour la médecine traditionnelle pour 2002-2005. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67313.

- World Health Organization. (2013). WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/92455.

- World Health Organization. (2021). SCORE for health data technical package: Global report on health data systems and capacity, 2020, Geneva (Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO).

- World Health Organization. (2022, November 16). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19. Edition 118. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—16-november-2022

- Wu, X. V., Dong, Y., Chi, Y., Yu, M., & Wang, W. (2021). Traditional Chinese medicine as a complementary therapy in combat with COVID-19—a review of evidence-based research and clinical practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(4), 1635–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14673

- Xu, J., & Xia, Z. (2019). Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) – does its contemporary business booming and globalization really reconfirm its medical efficacy & safety? Medicine in Drug Discovery, 1, 100003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medidd.2019.100003

- Yang, L., & Wang, Z. (2021). Natural products, alone or in combination with FDA-approved drugs, to treat COVID-19 and lung cancer. Biomedicines, 9(6), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9060689