ABSTRACT

Children in Africa are disproportionately burdened by the neurosurgical condition hydrocephalus. In Blantyre, Malawi, paediatric hydrocephalus represents the majority of surgical procedures performed in the neurosurgical department at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital. To reduce morbidity and mortality, timely detection followed by referral from surrounding primary health centres is crucial. Aiming to explore perceptions and identify enablers and barriers to detection and referral, we conducted a qualitative study among primary healthcare providers (n = 30) from ten health centres in Blantyre district. Using a semi-structured interview-guide, we audio-recorded and transcribed the interviews before conducting a thematic analysis. One main finding is that there is a potential to improve detection through head circumference measurements, which is the recommended way to detect hydrocephalus early, yet healthcare providers did not carry this out systematically. They described the health passport provided by the Malawian Ministry of Health as an important tool for clinical communication. However, head circumference growth charts are not included. To optimise outcomes for paediatric hydrocephalus we suggest including head circumference growth charts in the health passports. To meet the need for comprehensive management of paediatric hydrocephalus, we recommend more research from the continent, focusing on bridging the gap between primary care and neurosurgery.

Introduction

Hydrocephalus is one of the the most common paediatric neurosurgical conditions worldwide, with an estimated almost 400,000 new cases each year (Dewan, Rattani, Mekary, et al., Citation2019). About half of these cases occur in Africa (Dewan, Rattani, Mekary, et al., Citation2019), where access to neurosurgical services is severely limited (Dewan, Rattani, Fieggen, et al., Citation2019). Reasons for the disproportionate distribution in Africa include higher incidence of postinfectious hydrocephalus following neonatal sepsis (Karimy et al., Citation2020; Ranjeva et al., Citation2018) and hydrocephalus resulting from neural tube defects, compared to high-income regions (Dewan, Rattani, Mekary, et al., Citation2019). Although both these aetiologies are mostly preventable, neurosurgery is currently the only treatment option to minimise morbidity and avoid mortality.

A growing body of literature emerging from the global surgery and global neurosurgery movements argue that in order to strengthen comprehensive management for (neuro) surgical conditions it is imperative to invest in integral public health strategies across various care delivery platforms (Bath et al., Citation2019; Dewan, Rattani, Fieggen, et al., Citation2019; Lartigue et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2016; Veerappan et al., Citation2022), including primary care services (CHYSPR, Citation2021; Griswold et al., Citation2018; Meara et al., Citation2015; Santos et al., Citation2018). For example, the evidence-based consensus document from Harvard Medical School Comprehensive Policy Recommendations for the Management of Spina Bifida & Hydrocephalus in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (CHYSPR) (CHYSPR, Citation2021) underscores the significant challenges faced by children with hydrocephalus in low-resource settings. The same comprehensive approach is applied in the World Health Organization (WHO) document Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and other Neurological Disorders, 2022–2031 (IGAP) which was launched in May 2022 (The Lancet Neurology Editorial, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2023). IGAP outlines ambitious objectives and targets which, in harmony with CHYSPR, highlight the importance of involvement of primary healthcare in neurological/neurosurgical management to optimise brain health and ensure effective care pathways across the life course.

Monitoring of head growth through routine measurements of head circumference is the most effective way to detect hydrocephalus in children early (Amare et al., Citation2015; CHYSPR, Citation2021; Zahl & Wester, Citation2008). This is crucial, as delayed management can cause irreversible damage to the brain and is associated with surgical complications (Santos et al., Citation2017) and poor prognosis (Cadotte et al., Citation2010; CHYSPR, Citation2021; Eriksen et al., Citation2016; Heinsbergen et al., Citation2002; Ozor et al., Citation2018). While neurosurgery usually occurs in tertiary level hospitals, monitoring of head circumference in children to detect abnormal head growth would typically take place within primary care level. However, across African health systems, numerous factors contribute to barriers in receiving quality primary care, including a shortage of healthcare workers, inadequate education and limited experience within the healthcare workforce, workforce burnout, scarce availability of medical supplies and equipment, inappropriate referrals, heavy patient loads, and weak managerial systems (Abrahim et al., Citation2015; Kaunda et al., Citation2021; Kruk et al., Citation2017; Makwero, Citation2018; Mash et al., Citation2018; Meara et al., Citation2015). Previous research refers to contextual features and reasons for delayed presentation to treatment facilities (Bankole et al., Citation2015). For example, individual and community barriers include distance to the health facility and lack of transport, as well as cultural perceptions and practices (Miles, Citation2002). Health system barriers include the availability and attitudes of qualified and skilled health workers, and poor infrastructure (Cairo et al., Citation2018; Idowu & Olumide, Citation2011; Muir et al., Citation2016; Salvador et al., Citation2014; Salvador et al., Citation2015). Since the 1960ies until today, the African hydrocephalus literature has described late presentation of children to tertiary treatment facilities, and reported that children are presenting with grossly enlarged heads (Afolabi & Shokunbi, Citation1993; Amare et al., Citation2015; Aukrust, Parikh, et al., Citation2022; Beck & Lipschitz, Citation1969; Biluts & Admasu, Citation2016; Eriksen et al., Citation2016; Idowu & Olumide, Citation2011; Muir et al., Citation2016; Ozor et al., Citation2018; Peacock & Currer, Citation1984; Salvador et al., Citation2014; Salvador et al., Citation2015; Santos et al., Citation2017; Seligson & Levy, Citation1974). These reports have included Malawi (Chimaliro et al., Citation2022), located in the eastern sub-Saharan Africa, and the place for the study described in this paper.

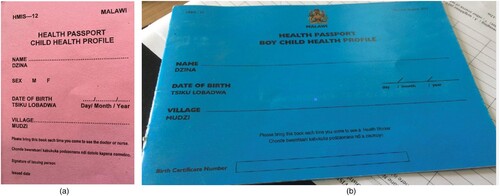

Children with hydrocephalus and their families meet a four-tiered healthcare service system in Malawi, as in many other African countries. This tiered system allows for more organised and efficient delivery of healthcare services, with each tier building upon the level below it. The Malawian Government provides small booklets for all children and adults called health passports, which serve as the primary mode of written clinical documentation and communication between healthcare providers within the different levels of care delivery. The health passport can be purchased at health facilities for a small amount of money. It is retained by the patients or, in the case of children by their parents, and should be brought to all routine check-ups or encounters with the healthcare system. Any important health event, such as immunisation, diseases or any medication prescribed is recorded in the health passport. For women of childbearing age, specific passports cover antenatal and maternity care, such as gestational age, planned delivery mode and breast-feeding information. The health passports for children include a weight for age monitoring growth chart, and the newest version of the health passport has added a length/height for age monitoring growth chart up until 5 years. While different versions of the health passports exist ((a,b)), none currently include head circumference growth charts.

Figure 1. (a) The older version of the health passport, which is still widely used, has one growth chart for weight, combined for boys and girls, but no growth chart for length or head circumference (private photo). (b) A more recent version of the health passport has separate growth charts for boys and girls for both weight and length, but no head circumference growth chart (CC-BY American Red Cross).

Studies from the largest tertiary level hospital in Malawi, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) located in Blantyre city, report substantial challenges when the paediatric hydrocephalus population meets the health system. In a recently published study from QECH, the authors stress the importance of detecting hydrocephalus early and suggest implementing monitoring of head growth through measurement of head circumference in primary health centres. They further suggest that providers in primary health centres receive education about hydrocephalus and head circumference measurements (Chimaliro et al., Citation2022). Although the study did not establish a causal relationship between delayed presentation and poor outcomes, they found a 1-year surgical mortality rate of hydrocephalic children of around 15% and a 1-year surgical morbidity rate of 33% (Chimaliro et al., Citation2022). Another study from the same setting concluded that almost 93% of the hydrocephalus children had severe sequela from the condition, only 66% had complete (or expected) control of bladder/bowel, 15% had a recent history of seizures, about 70% were stunted, while 44% were underweight. This study also found that almost 50% of the children had developmental delay, 41% to a severe degree (Rush et al., Citation2022).

Rationale and objectives

In order to meet the need for a comprehensive approach in the care delivery of paediatric hydrocephalus, we conducted a qualitative study among 30 healthcare providers in ten primary health centres in the catchment area of QECH in Blantyre, Malawi. The study had three research objectives: (1) To explore perceptions of paediatric hydrocephalus among primary healthcare providers in Blantyre, Malawi; (2) To describe enabling factors for identifying and referring children with suspected hydrocephalus within the primary health centre; (3) To identify barriers to identification and referral of suspected hydrocephalic children that primary healthcare providers encounter.

Materials and methods

Study setting

We conducted the study in Blantyre district in Malawi’s Southern Region. Blantyre district has both urban and rural areas and Blantyre city is the second most populated city in the country, with around 995,000 inhabitants (PopulationStat, Citation2022). Although all four central hospitals in Malawi perform hydrocephalus surgeries, only QECH and Kamuzu Central Hospital in the capital Lilongwe perform additional neurosurgical operations, and these services still need to be improved. For example, QECH, which serves as a referral hospital for patients from the entire Southern Region (population of roughly 7.7 million people) (National Statistical Office-Government of Malawi, Citation2019) as well as a secondary-level referral hospital for the 37 primary health centres in the district (personal communication with Chrissy Chilenje, Health Management Information Systems Officer at Blantyre District Health Office, October 25, 2023) had only one neurosurgeon (PDK) who managed all neurosurgical cases until 2020. Fortunately and partly due to a long-term institutional health partnership between Malawi and Norway initiated in 2013, three neurosurgeons and two neurosurgery residents are now available at QECH, along with a dedicated team of nurses (Slettebø et al., Citation2022). Of the 380 neurosurgical operations performed at QECH in 2016, 300 were associated with paediatric hydrocephalus (Chimaliro et al., Citation2022; Slettebø et al., Citation2022).

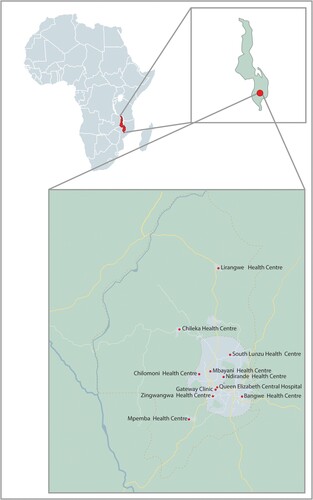

We aimed to achieve maximum variation (Maxwell, Citation2012) of health centres in Blantyre by selecting ten facilities based on various catchment areas (small vs big) (), location (urban vs peri-urban/rural), and distance from the main referral centre QECH (), as well accessibility. All facilities were public and free of charge for patients, attended to adults and children, included emergency and planned consultations, and commonly had opening hours from 07:30 to 16:30, but often received patients at all hours of the day.

Figure 2. Top left: African continent and Malawi marked in red. Top right: Malawi, Blantyre is marked as a dot. Bottom: Blantyre District, and Blantyre City marked with red dotted lines. The ten health centres we visited marked with a dot. QECH is marked with a cross.

Table 1. Selected primary health centres.

Study design and data collection

We conducted the study from February to April 2021, and deliberately chose an explorative and qualitative methodology to gain a deeper understanding of healthcare providers’ perceptions and experiences as well as the context in which they work. Based on relevance related to the research objectives, review of previous research, and conversations within the research team, we developed a semi-structured interview guide with 20 questions and several probes (Appendix 1). The interview guide included questions about the healthcare providers’ work in general, about hydrocephalus specifically, and traditional healing practices.

Due to travel restrictions during the pandemic, a Malawian research assistant (GF) with experience performing interviews within the Blantyre primary healthcare context, conducted the interviews alone. To ensure reliability and rigour, the first author and GF had several meetings through phone calls and text messages to prepare the interview guide and continued to have weekly meetings during the data collection period, which included six pilots and 30 interviews. After the pilot interviews, which were done in three different primary health centres (rural and urban) and included different professional cadres, we made some revisions to the interview guide. Considering the study’s explorative nature, we also made minor adjustments to the interview guide during data collection to better capture relevant and meaningful topics.

Participants

The study population consisted of healthcare providers within the selected primary health centres. Inclusion criteria were prior or potential future involvement with paediatric hydrocephalus patients. The health facility in-charge at the selected health centres identified relevant study participants. GF subsequently approached and recruited the healthcare providers, explained the study objectives in English or Chichewa, and obtained written informed consent for inclusion in the study and for recording the interview. All but one agreed to participate (no specific reason was provided).

We included two to four healthcare providers from each health centre based on convenience sampling; a pragmatic approach often applied within exploratory work (Green et al., Citation2018). To collect a diverse variety of perceptions and experiences (Green et al., Citation2018; Maxwell, Citation2012) also at the participant level, we included male and female healthcare workers of all ages and different professions (). The participants could choose between English and Chichewa for the interviews, as GF is fluent in both languages. Although all chose English, some participants used Chichewa words, phrases, or sentences to express an opinion, articulate a perspective, or communicate an experience during parts of the interview.

Table 2. Study participant’s demographics and characteristics.

Among all the 30 participants interviewed, seven responded that they had some healthcare specialisation (16 responded no to this question, and seven were unassigned). All participants described working hours as equivalent to a full-time position; most worked shifts (day and night). All nurses described having a rotation schedule, meaning they worked in different departments within the facility, typically alternating between antenatal, maternity and family planning. Clinicians and medical assistants were primarily working in the outpatient department.

Data management

GF conducted one or two interviews a day, and participants could choose the location for the interview. She recorded the interviews applying the ‘Dictaphone app’ provided by the University of Oslo, which immediately transferred the encrypted audio recordings to a safe server. In addition, GF made brief field notes moved to the same server. The mean interview time was 38, 9 minutes (27–56 minutes). During and following piloting and data collection, GF and CGA did verbatim transcriptions of all interviews by applying the software F4. Following this, CGA re-listened to the interviews to check for accuracy while reviewing the transcripts.

Qualitative analysis

CGA imported the transcribed interviews into the qualitative data analysis software Nvivo (version 12 Pro) and conducted a thematic content analysis. Following a thorough review, we identified 60 codes that we grouped into three overarching themes. Upon further examination of the transcripts, we have strategically chosen to focus on themes that we believe will have significant clinical implications.

Ethics

Prior to data collection, we presented and discussed the study proposal with the Blantyre District Health Office, who approved. On request from the Blantyre District Health Office, we also shared our findings with them after the data was analysed. In addition, we sought ethics and scientific review from the College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee in Blantyre, Malawi (protocol number P.11/19/2862), and approval was received on 23 January 2020. The Norwegian Regional Ethical Committee exempted the study from review. Last, we notified and received approval from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (reference number 691276). All participants received 1500 Malawian Kwacha (the equivalent of approximately 1.5 USD) as compensation for taking part in the study.

Results

Responding to our research objectives, we identified three key themes. First, healthcare providers had good theoretical knowledge of hydrocephalus and its severity. However, compared to other diseases they perceived it to be uncommon, and none of the primary healthcare providers mentioned to systematically and routinely monitor head circumference in children. Second, teamwork and communication were described as facilitating clinical work. The description of the health passport as a useful clinical communication tool applied by all providers across the different levels of service delivery was unanimous. Third, barriers to detection and referral included experiences related to contextual health systems constraints such as signs of previous traditional healing efforts, a high volume of patients, and transport challenges (for additional quotes, please see Appendix 2).

Perceptions

Overall, the healthcare providers demonstrated good theoretical knowledge of hydrocephalus. Several participants mentioned common signs of hydrocephalus, such as an enlarged head, irritability, sun-setting eyes, protruding skull veins, and bulging fontanelles.

Theoretical knowledge

Some participants mentioned that there was a possible link between neonatal infections and the development of hydrocephalus. In addition, all participants acknowledged that hydrocephalus is a condition that requires surgical intervention. Most mentioned the surgical procedure ventriculoperitoneal shunting, and that this could be performed at QECH.

‘I think hydro means water, cephale; is the head. So, we are told that hydrocephalus is the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid, more especially in the head. It may be due to two things. It is either an obstruction or an infection simply because the cerebrospinal fluid is produced in the head by the choroid plexus. So naturally, it is supposed to be produced and absorbed, so either there is an obstruction, or the absorption mechanism is disrupted. It is either an obstruction or an infection, and meningitis can cause that. This will cause accumulation of the fluid in the space in the head, that the head will get enlarged, I think that is it in short’ (IDI_6_M).

Hydrocephalus is severe but rare

Everyone described hydrocephalus as a severe condition associated with morbidity and mortality if left untreated. However, compared with other severe and common childhood illnesses such as malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea, hydrocephalus was perceived to be a rare encounter.

‘If the condition is not treated, the child may die’. (IDI_1_F)

‘Ahh, like here it’s very rare. It could be maybe in six months, could be one, it’s very rare’. (IDI_21_M)

The importance of the clinical gaze

Although the participants demonstrated good theoretical knowledge of hydrocephalus and the potentially severe consequences if left untreated, no one reported that head circumference measurements were monitored routinely during check-ups in their health facility. However, some said that head measurements were taken if a child’s head visually appeared to be larger than usual. The emphasis on the importance of the clinical gaze appeared to legitimate the lack of routine head circumference measurements, although some seemed to express a sense of ‘forgetfulness’ related to the ad-hoc measuring of head circumferences. Nine healthcare providers from five health centres mentioned that head circumference measurements were done immediately after birth, and one healthcare provider from another health centre mentioned that it was done at the nutrition services. All participants reported the absence of clinical guidelines for detecting hydrocephalus or performing head circumference measurements.

‘Of course, first we check the baby, if he has some abnormalities, weight and whatsoever. And even if you notice that the head is very, is big; we can also confirm maybe by measuring the head’. (IDI_1_F)

Communication

Communication included teamwork and telemedicine. During the pilot phase of the study the health passport was described as important, and we therefore included a question about this in the revised interview guide. The participants reported that the health passports are applied within the primary care facility, but also across levels of healthcare and between different professional cadres.

The health passport

According to the healthcare providers, the health passport is a document where ‘everyone documents everything’. The mothers keep the health passport, and different cadres of healthcare professionals will use this small booklet to record information. For example, the participants mentioned that nurses would record information related to postnatal visits, and clinicians document any illnesses or prescriptions. Health surveillance assistants typically enter immunisation and anthropometric measurements, such as weight.

‘The health passport is used every time they (referring to mother and child) visit the facility for a check-up. Whatever has been done is documented in the health passport. For example, it will be documented if the child comes for vaccines. For weighing, and weight monitoring, it will be documented. If the child is sick, it will also be documented’. (IDI_19_M)

Teamwork and telemedicine

The participants underscored the importance of teamwork in facilitating clinical work, mainly when there was uncertainty about a patient's condition. Collaboration could involve communication with other providers within the health centre, the Blantyre District Health Office, and QECH. The participants highlighted telemedicine, such as telephone calls, WhatsApp groups, and a ‘friend squad group’. The identification of teamwork as an opportunity to have more ‘eyes and heads’ was seen as advantageous in a clinical environment with a high volume of patients. Furthermore, communicating as a team was considered beneficial for the patients and motivating for healthcare providers.

‘Sometimes it is, you may be a couple of you on duty, so you call your friends from another department to come and discuss a condition. When you are alone, you can do it over the phone. So, you call somebody you consider more experienced and explain everything you see, and then you can discuss on the phone on the way forward, so we consult each other’. (IDI_18_M)

Contextual health systems conditions

The healthcare providers mentioned several contextual health systems challenges affecting the treatment and care of patients. These challenges consisted of factors relating to the existence of a parallel healing system, heavy patient loads, and the lack of transportation.

Parallel healing systems

While some healthcare providers confirmed asking about previous treatment efforts, others expressed that this was a sensitive topic. Signs of earlier visits to traditional healers included skin scars or tattoos, amulets, strings around the waist, or stories of herbal medicine use. While some providers believed it was common to seek treatment from traditional healers before going to the primary health centres, others reported that families of sick children went straight to QECH, bypassing the primary healthcare level.

‘At first, I just heard, but I have no evidence that a certain child was with … According to the explanation of the lay people, it could be hydrocephalus because they said that the child had a big head, and they went to a traditional healer. The traditional healer confirmed that maybe there are many fluids in there, so we needed to remove the fluid, and they tried to pierce with … a razor blade. However, they said it was a big incision, so they drained the blood instead of the water. So, the mother was curious that you have said there was much water here and look what is coming, it is blood, and it was not successful, and I do not know if that child is still alive, I just heard’. (IDI_14_F)

Patient loads-triage and priorities

Many healthcare providers described enormous patient loads, sometimes between 200 and 600 daily. Because of high patient volumes and frequent encounters with severe conditions, many participants also mentioned triaging and negotiation of urgency, what needed to be done immediately and what could be given less attention or postponed.

‘Yes, sometimes, mostly during this season of malaria, sure we reach up to 500, 600’. (referring to patients) (IDI_2_F)

Challenges with transportation

All the healthcare providers reported that mothers were the ones who typically accompanied their children to the primary health centre, most often by walking, public transport, or bike/motorbike. However, when the patients needed to transfer from the primary health centre to QECH, the availability of ambulances and fuel posed a challenge. Although many health centres were urban and not necessarily very far away from QECH, it would still be far to walk. Patients were often advised to use public transport if they could pay for a minibus.

‘The second one is (referring to the second challenge), sometimes we have a fuel shortage. So, if you call for an ambulance, we have this case, and they will respond that the ambulance is now at Chileka health centre; from Chileka, the ambulance will go to Mpemba. From Mpemba, every then you can find that it is not easy. So, if they have some money to use for public transport, we advise them to go. If they do not have, we have no option; we wait up to night’. (IDI_14_F)

Discussion

Applying a qualitative methodology, we aimed to explore perceptions of hydrocephalus and identify enabling factors and barriers to detect and refer suspected hydrocephalic children within the primary care context in Blantyre, Malawi. The discussion will primarily focus on findings we perceive as most relevant to guide clinical practice.

Despite Malawi’s efforts and progress to reduce under-five child mortality (Moise et al., Citation2017), children daily die from preventable and treatable medical conditions such as malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhoea (Kobayashi et al., Citation2017), and more than 40% of children are stunted (Agyepong et al., Citation2017). Clinical care is always context dependant, and therefore it is unsurprising that the healthcare providers in Blantyre perceive hydrocephalus to be a less important health problem. However, while some neurosurgical disorders, such as hydrocephalus, are relatively uncommon compared to other conditions, they are still accountable for considerable morbidity and mortality.

Although the initiation of several neurosurgery capacity-building efforts at QECH in recent years is timely and necessary, the lack of systematic head circumference measurements within primary healthcare represents a barrier to detecting and referring children that may need further investigations and evaluations due to an enlarged or rapidly growing head. This finding points to the importance of providing comprehensive care, as prescribed by IGAP and CHYSPR. Improvements in one sector of the healthcare system may not necessarily result in better outcomes for patients if delivery in other areas is suboptimal. To treat hydrocephalus in children effectively, timely surgery is of uttermost importance. The expanded neurosurgery capacity at QECH is necessary for escalated clinical management of neurosurgical cases in general and paediatric hydrocephalus cases. However, the expansion alone is insufficient because successful clinical outcomes depend on timely identification and appropriate referrals from primary healthcare providers (Chimaliro et al., Citation2022), often referred to as gatekeepers of the healthcare system (Meara et al., Citation2015). To address this would respond to several of IGAP’s five objectives (World Health Organization, Citation2023), and the CHYSPR group’s recommendations that head measurements are taken at all routine encounters with the healthcare system during childhood, in addition to emphasise on efficient and appropriate referral pathways (CHYSPR, Citation2021). Our participants identified communication tools, such as telemedicine platforms and the health passport, as beneficial for identifying and referring patients across different care delivery platforms.

Head circumference measurement is an important screening tool and indicator for brain development in children (Bergerat et al., Citation2021; Eriksen et al., Citation2016; Zahl & Wester, Citation2008). However, there is a need for growth charts to detect and discern the normal from the abnormal according to age and gender (Bergerat et al., Citation2021). The WHO has developed and published international child growth standards collected through the Multicentre Growth Reference Study (Bergerat et al., Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2007; World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, Citation2006). Although some of our participants reported taking head circumference measurements immediately after birth, the usefulness of such stand-alone measurements is limited. Especially in a sub-Saharan African context, such as Malawi, where studies have shown that the most common cause of hydrocephalus in children is of postinfectious origin (Adeloye & Khare, Citation1997; Aukrust, Paulsen, et al., Citation2022; Dewan, Rattani, Mekary, et al., Citation2019; Warf, Citation2022). This is typically not evident at birth but evolves following an infection in the neonatal period, strengthening the argument and rationale of serial measurements after birth for this population.

Although the WHO has developed reference ranges for child growth, several studies have addressed limitations to these international standards (Bergerat et al., Citation2021; Daymont et al., Citation2010; Natale & Rajagopalan, Citation2014). In Ethiopia, they found that reference ranges for children below two years differed significantly from the WHO reference ranges (Amare et al., Citation2015). In line with these findings, a recent systematic review concluded that national and ethnic group head circumference means varied considerably, and that using the international WHO charts could lead to children erroneously being diagnosed as having either micro or macrocephaly (Natale & Rajagopalan, Citation2014). In addition, and importantly, an enlarged or rapidly growing head does not in itself equal a diagnosis of hydrocephalus. It merely indicates that further investigations may be required. Nonetheless, monitoring head growth can provide essential information, and a Norwegian study found that head circumference measurements were vital to detect hydrocephalus within the first year of life (Zahl & Wester, Citation2008).

In Malawi, there are no nationally developed head circumference measurement ranges. Nevertheless, systematic head circumference measurements should be supported, and including the WHO international growth charts for head circumference in the health passports provides potential for improvements related to detection and referral of suspected hydrocephalus children. While growth charts for head circumference measurements are not included in the national Malawian health passports, all children with a confirmed hydrocephalus diagnosis in Blantyre are provided with a SHIP (short for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus International Program) passport. The SHIP passports are developed by the International Federation for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus and have included growth charts applying the international reference ranges from the WHO (International Federation for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus, Citation2023). Although these passports are invaluable for children who have been diagnosed with hydrocephalus, they are not utilised in detecting the condition in children on routine health check-ups at the health centres.

Measuring head circumference is low-cost, time efficient, and without side effects, which makes it practical and accessible for primary healthcare providers in resource-limited contexts. Despite the conceptual simplicity of monitoring head circumference, a worldwide survey uncovered that healthcare providers encountered both theoretical and practical challenges using growth charts, including difficulties interpreting growth and reference curves (de Onis et al., Citation2004). The study found that while the weight-for-age charts were applied globally, only 33% of countries used head circumference-for age-charts, and only 2% did so in the African region (de Onis et al., Citation2004). However, progress has been made and a later survey concerned with the implementation process of the WHO child growth standards which was launched in 2006, found that seven of 31 African countries included in the study had adopted head-circumference for age charts. They also found that resource constraints, coordination challenges, procedural impediments, and other more pressing health priorities were challenges encountered in the implementation process (de Onis et al., Citation2012). This is in line with an Ethiopian study reporting on barriers encountered when implementing the national reference ranges within their local health centres (Eriksen et al., Citation2016). Challenges included poor compliance due to long lines of patients, reluctance to adopt another routine examination procedure, and staff rotation. In addition, they found that compared to other diseases, such as malaria and diarrhoea, the relatively lower incidence rate of hydrocephalus made it difficult for healthcare providers to see the potential gain and acknowledge it as a priority (Eriksen et al., Citation2016). This is consistent with what the healthcare providers in our study reported. Although the participants expressed sound theoretical knowledge of hydrocephalus, they viewed it as a less common condition than other serious and daily illnesses, such as malaria, and introducing a new medical routine in a clinical context already facing multiple severe global health maladies may seem overwhelming. Nevertheless, it is a paradox that this screening method is not consistently carried out when epidemiological research shows that hydrocephalus, especially the acquired postinfectious form, represents a significant health issue in sub-Saharan Africa (Aukrust, Paulsen, et al., Citation2022; Dewan, Rattani, Mekary, et al., Citation2019; Warf, Citation2022), including in Malawi (Adeloye & Khare, Citation1997; Chimaliro et al., Citation2022; Kamalo, Citation2013).

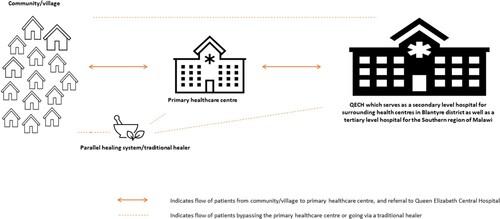

Our study suggests that contextual factors, including the existence of parallel healing systems such as traditional healers, high volumes of patients, and the unavailability of ambulances or fuel, are perceived as obstacles to timely detection and referrals. In addition to the formal tiered healthcare system, traditional healers and traditional medicine are widely used across Africa (DeJong, Citation1991; Meara et al., Citation2015; World Health Organization, Citation2002), including in Malawi (Hill et al., Citation2019; Simwaka et al., Citation2007). Several African studies have addressed the tendency to attribute supernatural powers as a cause of hydrocephalus, which may act as a barrier to timely presentation (Bankole et al., Citation2015; Idowu & Olumide, Citation2011; Mathebula et al., Citation2018; Salvador et al., Citation2014; Santos et al., Citation2018; Seligson & Levy, Citation1974). The tendency to seek traditional healing for hydrocephalus aligns with the literature (Bankole et al., Citation2015; Idowu & Olumide, Citation2011) describing religious, social, and cultural factors leading patients to present in the primary healthcare sector after reaching out to more informal providers (Ozor et al., Citation2018). Yet, other studies describe that patients tend to bypass the primary care level and seek help directly at the tertiary level (Abrahim et al., Citation2015), indicating that the primary level within the tiered health systems pyramid is often in reality secondary or simply omitted. While our participants mentioned that mothers of hydrocephalic children might seek help from informal providers (traditional healers), some also said they were prone to go directly to QECH, indicating the complex role of primary care within the healthcare system ().

Figure 3. Illustrative representation of referral pathways as described by our participants; sometime bypassing the primary healthcare centres and other times going via traditional healers.

Many participants in our study reported experiencing massive patient loads, reinforcing the need for a straightforward and pragmatic method for healthcare providers to perform additional anthropometric measures, such as head measurements. To harness the leveraging opportunities that lie in including head circumference growth charts in the health passport is not only a WHO recommendation but also has strong support from local civil society and the non-governmental organisation Child Help Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus in Malawi, as well as the neurosurgical department at QECH. Last, our findings indicate that the unavailability of ambulances and fuel was perceived as a barrier to timely referral, which is line with the literature (Meara et al., Citation2015), including a study from Malawi (Varela et al., Citation2019).

While each of these three factors alone may contribute to delay detection and referral, their interplay exacerbates the clinical challenges caused by deferred medical attention, underscoring the need ‘to look beyond the narrow focus of the operating theatre’ (Bagenal et al., Citation2023, p. 86), and to address the broader contextual factors contributing to the lack of access and availability of surgical services in resource-constrained settings (Meara et al., Citation2015). The cascade of delays at various stages has been comprehensively addressed within the surgical literature (Meara et al., Citation2015), applying the three delays framework as a lens (Thaddeus & Maine, Citation1994). In this framework, the first delay is described as a delay in seeking medical care, the second delay involves a delay in reaching care, and the third delay includes a delay in receiving care. Our results identify visits to traditional healers as the first delay (delay in seeking medical attention), the huge patient volumes at the health centres and the overstretched healthcare system act as a second delay (delay in detection and referral), while challenges with transportation act as the third delay (delay in reaching appropriate neurosurgical care). The second delay (delay in receiving care) is not limited to appropriately detecting children suspected to have hydrocephalus within the primary level but also involves timely attention within the tertiary hospital context. This underscores the tight connection between all levels of the healthcare system and the importance of acknowledging the comprehensiveness of the (neuro)surgical ecosystem.

Strengths and limitations

Our study aimed for maximum variation by interviewing healthcare providers with varying ages and years of work experience from ten different health centres in Blantyre. However, there are certain limitations inherent to qualitative methodology. GF’s experience with the context enabled the first author and GF to adjust the interview guide to enhance cultural relevance. In addition, the fact that GF is not a clinician may have resulted in less subject bias and the tendency of research participants to respond to the interviewer according to what they think is expected of them. This duality, acknowledging GF’s positionality as both an outsider (not a clinician) and an insider (being Malawian) with first-hand knowledge of contextual codes, may have influenced the study's findings positively and negatively. A strength of the study was GF’s fluency in English and Chichewa. Although all participants said they wanted to be interviewed in English, some switched to Chichewa phrases or words during parts of the interview, which might have provided nuances and perspectives that would have been lost had this opportunity not been provided. Finally, recall bias represents a possible limitation to our study, as we cannot exclude that participants did not accurately remember encounters with patients that occurred sometime back. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the perceptions, enablers, and barriers that healthcare providers in Blantyre encounter in detecting and referring suspected hydrocephalic children.

Conclusion

While access to neurosurgical services is severely limited in sub-Saharan Africa and investments are needed to strengthen management in tertiary level hospitals, this should not hinder simultaneous and comprehensive efforts beyond the operating rooms. Given the expansion of neurosurgical services at QECH, it is timely and necessary to initiate parallel endeavours within primary care. To implement the propositions and recommendations of IGAP and CHYSPR we suggest three critical steps that require further attention. First, future research should aim to establish national reference ranges for head circumference in Malawian children. In the meantime, the WHO international reference ranges may be applied. Second, including head circumference growth charts in the health passports, coupled with supervision and guidance on using these charts, is a fundamental and necessary initial step to improve early identification and timely referrals of (suspected) hydrocephalus children. Finally, there is a need for more research from the African continent and Malawi to investigate how to bridge the gap between primary healthcare and neurosurgery, avoid fragmented management conducted in silos, and enhance care delivery for children with hydrocephalus.

Authorship statement

CGA: Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, writing original draft, project administration, funding acquisition. PDK: Conceptualisation, writing-review and editing, and supervision. GF: Investigation (data collection). CM: Methodology, writing-review and editing, and supervision. BAC: Writing-review and editing. HEF: Methodology, writing-review and editing, and supervision. LMT: Methodology, writing-review and editing, and supervision.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We want to thank our study participants for their valuable time. We would not be able to share our findings without them. We also wish to thank Chrissy Chilenje (Health Management Information Systems Officer at the District Health Office, Blantyre, Malawi) for providing information about the number of health centres in Blantyre district and the catchment population for the health centres included in this study (). In addition, we are grateful to Ine Eriksen (Medical Photography and Illustration Service at the University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) for making the map of Africa/Blantyre (). Last, we want to thank the Department of Global Health at Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway for providing practical support and housing for the first author when she is in Blantyre, Malawi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data sets used and analysed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahim, O., Linnander, E., Mohammed, H., Fetene, N., & Bradley, E. (2015). A patient-centered understanding of the referral system in Ethiopian primary health care units. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0139024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139024

- Adeloye, A., & Khare, R. (1997). Ultrasonographic study of children suspected of hydrocephalus at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. East African Medical Journal, 74(4), 267–270.

- Afolabi, A., & Shokunbi, M. (1993). Socio-economic implications of the surgical treatment of hydrocephalus. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics, 20(4), 94–97.

- Agyepong, I. A., Sewankambo, N., Binagwaho, A., Coll-Seck, A. M., Corrah, T., Ezeh, A., Fekadu, A., Kilonzo, N., Lamptey, P., Masiye, F., Mayosi, B., Mboup, S., Muyembe, J.-J., Pate, M., Sidibe, M., Simons, B., Tlou, S., Gheorghe, A., Legido-Quigley, H., … Piot, P. (2017). The path to longer and healthier lives for all Africans by 2030: The Lancet Commission on the future of health in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet, 390(10114), 2803–2859. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31509-X

- Amare, E. B., Idsoe, M., Wiksnes, M., Moss, T., Roelants, M., Shimelis, D., Júlíusson, P. B., Kiserud, T., & Wester, K. (2015). Reference ranges for head circumference in Ethiopian children 0–2 years of Age. World Neurosurgery, 84(6), 1566–1571.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.08.045

- Aukrust, C. G., Parikh, K., Smart, L. R., Mdala, I., Fjeld, H. E., Lubuulwa, J., Makene, A. M., Härtl, R., & Winkler, A. S. (2022). Pediatric hydrocephalus in northwest Tanzania: A descriptive cross-sectional study of clinical characteristics and early surgical outcomes from the Bugando Medical Centre. World Neurosurgery, 161, e339–e346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.02.003

- Aukrust, C. G., Paulsen, A. H., Uche, E. O., Kamalo, P. D., Sandven, I., Fjeld, H. E., Strømme, H., & Eide, P. K. (2022). Aetiology and diagnostics of paediatric hydrocephalus across Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 10(12), e1793–e1806. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00430-2

- Bagenal, J., Lee, N., Ademuyiwa, A. O., Nepogodiev, D., Ramos-De la Medina, A., Biccard, B., Lapitan, M. C., & Waweru-Siika, W. (2023). Surgical research—comic opera no more. The Lancet, 402(10396), 86–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00856-5

- Bankole, O. B., Ojo, O. A., Nnadi, M. N., Kanu, O. O., & Olatosi, J. O. (2015). Early outcome of combined endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroid plexus cauterization in childhood hydrocephalus. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 15(5), 524–528. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.10.PEDS14228

- Bath, M., Bashford, T., & Fitzgerald, J. E. (2019). What is ‘global surgery’? Defining the multidisciplinary interface between surgery, anaesthesia and public health. BMJ Global Health, 4(5), e001808–e001808. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001808

- Beck, J., & Lipschitz, R. (1969). Hydrocephalus in African children: A survey of 3 years’ experience at Baragwanath Hospital. South African Medical Journal. Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde, 43(21), 656–658.

- Bergerat, M., Heude, B., Taine, M., Nguyen The Tich, S., Werner, A., Frandji, B., Blauwblomme, T., Sumanaru, D., Charles, M.-A., Chalumeau, M., & Scherdel, P. (2021). Head circumference from birth to five years in France: New national reference charts and comparison to WHO standards. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe, 5, 100114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100114

- Biluts, H., & Admasu, A. K. (2016). Outcome of endoscopic third ventriculostomy in pediatric patients at Zewditu Memorial Hospital, Ethiopia. World Neurosurgery, 92, 360–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.114

- Cadotte, D. W., Viswanathan, A., Cadotte, A., Bernstein, M., Munie, T., & Freidberg, S. R. (2010). The consequence of delayed neurosurgical care at Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. World Neurosurgery, 73(4), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2010.02.017

- Cairo, S. B., Agyei, J., Nyavandu, K., Rothstein, D. H., & Kalisya, L. M. (2018). Neurosurgical management of hydrocephalus by a general surgeon in an extremely low resource setting: Initial experience in North Kivu province of Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Pediatric Surgery International, 34(4), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-018-4238-0

- Chimaliro, S., Hara, C., & Kamalo, P. (2022). Mortality and complications 1 year after treatment of hydrocephalus with endoscopic third ventriculostomy and ventriculoperitoneal shunt in children at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Malawi. Acta Neurochirurgica, 165, 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-022-05392-7

- CHYSPR. (2021). Comprehensive Policy Recommendations for the Management of Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus in Low-and Middle-income Countries. Program in global surgery and social change, Harvard Medical School, MA, 641 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from https://www.chyspr.org/

- Daymont, C., Hwang, W.-T., Feudtner, C., & Rubin, D. (2010). Head-circumference distribution in a large primary care network differs from CDC and WHO curves. Pediatrics, 126(4), e836–e842. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0410

- DeJong, J. (1991). Traditional medicine in Sub-Saharan Africa: Its importance and potential policy options (Vol. 735). World Bank Publications.

- de Onis, M., Onyango, A., Borghi, E., Siyam, A., Blössner, M., & Lutter, C. (2012). Worldwide implementation of the WHO Child Growth Standards. Public Health Nutrition, 15(9), 1603–1610. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001200105X

- de Onis, M., Wijnhoven, T. M., & Onyango, A. W. (2004). Worldwide practices in child growth monitoring. The Journal of Pediatrics, 144(4), 461–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.034

- Dewan, M. C., Rattani, A., Fieggen, G., Arraez, M. A., Servadei, F., Boop, F. A., Johnson, W. D., Warf, B. C., & Park, K. B. (2019). Global neurosurgery: The current capacity and deficit in the provision of essential neurosurgical care. Executive summary of the global neurosurgery initiative at the program in global surgery and social change. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.11.JNS171500

- Dewan, M. C., Rattani, A., Mekary, R., Glancz, L. J., Yunusa, I., Baticulon, R. E., Fieggen, G., Wellons, J. C., Park, K. B., & Warf, B. C. (2019). Global hydrocephalus epidemiology and incidence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Neurosurgery, 130(4), 1065–1079. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.10.JNS17439

- Eriksen, A. A., Johnsen, J. S., Tennoe, A. H., Tirsit, A., Laeke, T., Amare, E. B., & Wester, K. (2016). Implementing routine head circumference measurements in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Means and challenges. World Neurosurgery, 91, 592–596.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.132

- Green, J., Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research (4th ed.). SAGE.

- Griswold, D. P., Makoka, M. H., Gunn, S. W. A., & Johnson, W. D. (2018). Essential surgery as a key component of primary health care: Reflections on the 40th anniversary of Alma-Ata. BMJ Global Health, 3(Suppl 3), e000705. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000705

- Heinsbergen, I. N. A., Rotteveel, J. A. N., Roeleveld, N. E. L., & Grotenhuis, A. (2002). Outcome in shunted hydrocephalic children. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 6(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1053/ejpn.2001.0555

- Hill, J., Seguin, R., Phanga, T., Manda, A., Chikasema, M., Gopal, S., & Smith, J. S. (2019). Facilitators and barriers to traditional medicine use among cancer patients in Malawi. PloS One, 14(10), e0223853.

- Idowu, O., & Olumide, A. (2011). Etiology and cranial CT scan profile of nontumoral hydrocephalus in a tertiary black African hospital: Clinical article. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 7(4), 397–400. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.1.PEDS10481

- International Federation for Spina Bifida and Hydrocephalus. (2023). Retrieved March 27, 2023, from https://www.ifglobal.org/our-work/international-solidarity/

- Kamalo, P. (2013). Exit ventriculoperitoneal shunt; enter endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV): Contemporary views on hydrocephalus and their implications on management. Malawi Medical Journal, 25(3), 78–82.

- Karimy, J. K., Reeves, B. C., Damisah, E., Duy, P. Q., Antwi, P., David, W., Wang, K., Schiff, S. J., Limbrick, D. D., Alper, S. L., Warf , B. C., Nedergaard, M., Simard, J. M., & Kahle, K. T. (2020). Inflammation in acquired hydrocephalus: Pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nature Reviews Neurology, 16(5), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-0321-y

- Kaunda, W., Umali, T., Chirwa, M. E., & Nyondo-Mipando, A. L. (2021). Assessing facilitators and barriers to referral of children under the age of five years at Ndirande Health Centre in Blantyre, Malawi. Global Pediatric Health, 8, 2333794X2110518–2333794X211051815. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X211051815

- Kobayashi, M., Mwandama, D., Nsona, H., Namuyinga, R. J., Shah, M. P., Bauleni, A., Eng, J. V., Mathanga, D. P., Rowe, A. K., & Steinhardt, L. C. (2017). Quality of case management for pneumonia and diarrhea among children seen at health facilities in southern Malawi. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 96(5), 1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0945

- Kruk, M. E., Chukwuma, A., Mbaruku, G., & Leslie, H. H. (2017). Variation in quality of primary-care services in Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, Senegal, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(6), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.16.175869

- Lartigue, J. W., Dada, O. E., Haq, M., Rapaport, S., Sebopelo, L. A., Ooi, S. Z. Y., Senyuy, W. P., Sarpong, K., Vital, A., Khan, T., Karekezi, C., & Park, K. B. (2021). Emphasizing the role of neurosurgery within global health and national health systems: A call to action. Frontiers in Surgery, 8, 690735–690735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.690735

- Makwero, M. T. (2018). Delivery of primary health care in Malawi. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1799

- Mash, R., Howe, A., Olayemi, O., Makwero, M., Ray, S., Zerihun, M., & Goodyear-Smith, F. (2018). Reflections on family medicine and primary healthcare in sub-saharan Africa. BMJ Specialist Journals, 3, e000662.

- Mathebula, R. C., Lerotholi, M., Ajumobi, O. O., Makhupane, T., Maile, L., & Kuonza, L. R. (2018). A cluster of paediatric hydrocephalus in Mohale’s Hoek district of Lesotho, 2013–2016. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health, 1(3).

- Maxwell, J. A. (2012). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (Vol. 41). SAGE.

- Meara, J. G., Leather, A. J. M., Hagander, L., Alkire, B. C., Alonso, N., Ameh, E. A., Bickler, S. W., Conteh, L., Dare, A. J., Davies, J., Mérisier, E. D., El-Halabi, S., Farmer, P. E., Gawande, A., Gillies, R., Greenberg, S. L. M., Grimes, C. E., Gruen, R. L., Ismail, E. A., … Yip, W. (2015). Global Surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet, 386(9993), 569–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X

- Miles, M. (2002). Children with hydrocephalus and spina bifida in East Africa: Can family and community resources improve the odds? Disability & Society, 17(6), 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759022000010425

- Moise, I. K., Kalipeni, E., Jusrut, P., & Iwelunmor, J. I. (2017). Assessing the reduction in infant mortality rates in Malawi over the 1990–2010 decades. Global Public Health, 12(6), 757–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1239268

- Muir, R. T., Wang, S., & Warf, B. C. (2016). Global surgery for pediatric hydrocephalus in the developing world: A review of the history, challenges, and future directions. Neurosurgical Focus, 41(5), E11. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.7.FOCUS16273

- Natale, V., & Rajagopalan, A. (2014). Worldwide variation in human growth and the World Health Organization growth standards: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 4(1), e003735. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003735

- National Statistical Office-Government of Malawi. (2019). 2018 Malawi Population and Housing Census Main Report-National Statistical Office May 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://malawi.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/2018%20Malawi%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census%20Main%20Report%20%281%29.pdf

- Ozor, I. I., Chikani, M., Dada, O., Mezue, W., Ohaegbulam, S., & Ndubuisi, C. (2018). Causes of delayed presentation In patients with hydrocephalus. Journal of Experimental Research, 6(2), 52–59.

- Park, K. B., Johnson, W. D., & Dempsey, R. J. (2016). Global neurosurgery: The unmet need. World Neurosurgery, 88, 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.12.048

- Peacock, W. J., & Currer, T. H. (1984). Hydrocephalus in childhood. A study of 440 cases. South African Medical Journal. Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde, 66(9), 323–324.

- PopulationStat. (2022). Population stat-world statistical data. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://populationstat.com/malawi/blantyre

- Ranjeva, S. L., Warf, B. C., & Schiff, S. J. (2018). Economic burden of neonatal sepsis in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Global Health, 3(1), e000347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000347

- Rush, J., Paľa, A., Kapapa, T., Wirtz, C. R., Mayer, B., Micah-Bonongwe, A., Gladstone, M., & Kamalo, P. (2022). Assessing neurodevelopmental outcome in children with hydrocephalus in Malawi. A pilot study. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 212, 107091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.107091

- Salvador, S., Henriques, J., Munguambe, M., Vaz, R. M. C., & Barros, H. (2014). Hydrocephalus in children less than 1 year of age in northern Mozambique. Surgical Neurology International, 5(1), 175. https://doi.org/10.4103/2152-7806.146489

- Salvador, S., Henriques, J. C., Munguambe, M., Vaz, R. M., & Barros, H. P. (2015). Challenges in the management of hydrocephalic children in northern Mozambique. World Neurosurgery, 84(3), 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2015.03.064

- Santos, M. M., Qureshi, M. M., Budohoski, K. P., Mangat, H. S., Ngerageza, J. G., Schöller, K., Shabani, H. K., Zubkov, M. R., & Härtl, R. (2018). The growth of neurosurgery in east Africa: Challenges. World Neurosurgery, 113, 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.01.084

- Santos, M. M., Rubagumya, D. K., Dominic, I., Brighton, A., Colombe, S., O'Donnell, P., Zubkov, M. R., & Hartl, R. (2017). Infant hydrocephalus in sub-Saharan Africa: The reality on the Tanzanian side of the lake. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 20(5), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.5.PEDS1755

- Seligson, D., & Levy, L. F. (1974). Hydrocephalus in a developing country: A ten-year experience. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 16(3), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1974.tb03347.x

- Simwaka, A., Peltzer, K., & Maluwa-Banda, D. (2007). Indigenous healing practices in Malawi. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 17(1-2), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2007.10820162

- Slettebø, H., Aukrust, C. G., Rønning, P., Tisell, M., & Kamalo, P. (2022). Establishing neurosurgery in Malawi – the story of a fruitful collaboration. Journal of Global Neurosurgery, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.51437/jgns.v2i1.55

- Thaddeus, S., & Maine, D. (1994). Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social Science & Medicine, 38(8), 1091–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7

- The Lancet Neurology Editorial. (2022). WHO launches its Global Action Plan for brain health. The Lancet Neurology, 21(8), 671–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00266-6

- Varela, C., Young, S., Mkandawire, N., Groen, R. S., Banza, L., & Viste, A. (2019). Transportation barriers to access health care for surgical conditions in Malawi a cross sectional nationwide household survey. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 264–264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6577-8

- Veerappan, V. R., Gabriel, P. J., Shlobin, N. A., Marks, K., Ooi, S. Z., Aukrust, C. G., Ham, E., Abdi, H., Negida, A., & Park, K. B. (2022). Global neurosurgery in the Context of Global Public Health Practice-A literature review of case studies. World Neurosurgery.

- Warf, B. C. (2022). Postinfectious hydrocephalus in African infants: Common, under-recognised, devastating, and potentially preventable. The Lancet Global Health, 10(12), e1695–e1696. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00461-2

- World Health Organization. (2002). WHO traditional medicine strategy 2002–2005. Retrieved June 7, 2023, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67163/WHO_EDM_TRM_2002.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. (2007). WHO Child Growth Standards. Head circumference-for-age, arm circumference-for-age, triceps skinfold-for-age and subscapular skinfold-for-age. Methods and development. World Health Organization. Retrieved June 7, 2023, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924154693X

- World Health Organization. (2023). Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and other Neurological Disorders 2022-2031. Retrieved October 26, 2023, from 9789240076624-eng.pdf (who.int)

- World Health Organization Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. (2006). WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement, 450, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x

- Zahl, S. M., & Wester, K. (2008). Routine measurement of head circumference as a tool for detecting intracranial expansion in infants: What is the gain? A nationwide survey. Pediatrics, 121(3), e416–e420. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1598