?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

While there have been notable advancements in child health in Egypt, disparities in child mortality still exist. Understanding these disparities is crucial to addressing them. The objective of this study is to explore the factors linked to child mortality in Egypt, providing a comprehensive understanding of the disparities in child mortality rates. The study utilises cross-sectional data from Egypt's Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) in 2014 to examine child mortality. The dataset consists of 15,848 observations from mothers with children born within five years prior to the survey. The choice of explanatory variables was guided by the Mosely and Chen Framework and logistic multivariate regression was used to conduct the analyses. The study finds lower education, early childbearing, insufficient birth spacing, lack of breastfeeding, and absence of improved toilet facilities (proxy for living conditions) were all significantly linked to an increased likelihood of child loss. Additionally, poorer people in rural settings experienced the worst child mortality. The findings align with the World Health Organization's Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). Recommended policy interventions include targeting women in rural areas, improving living conditions and removing financial/other barriers to accessing care.

1. Introduction

The global under-five mortality (U5M) rate was estimated at 37 deaths per 1000 live births in 2020. This represents a dramatic drop of almost 60% from 1990. Despite this remarkable achievement, the burden of child mortality remains uneven; U5M in Africa, which has the highest rate in the world, is 72 per 1000 live births in 2020 (WHO, Citation2022). Additionally, within a single country such as Egypt, there are variations in rates, with under-five mortality (U5M) being higher in rural areas compared to urban ones (EDHS, Citation2015).

Notwithstanding an overall decline in child mortality in recent decades, it remains a global challenge and a focus of development plans for low and lower-middle-income nations. Egypt is no exception. Egypt adopted the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) strategy in healthcare facilities in 1997 to address the main diseases that cause child death and improve knowledge about preventing illnesses such as diarrhoea and malnutrition. The strategy has been successful in significantly reducing U5M between 2000 and 2005 (Rakha et al., Citation2013). However, the U5M remained virtually unchanged between 2008 and 2014 (28 per 1000 live births in 2008 and 27 per 1000 live births in 2014) (EDHS, Citation2015).

This paper aims to investigate the factors associated with child mortality in Egypt, offering a deeper insight into the disparities present in child mortality rates with a particular focus on urban-rural inequalities. The study is guided by our adaptation of the 1984 Mosley and Chen Child Survival framework and employs multivariate regression analysis to examine the influence of different factors.

2. Conceptual frameworks

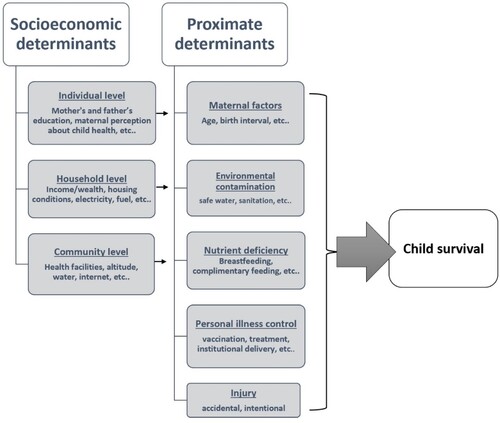

Utilising the Mosley and Chen framework, this study seeks to uncover factors potentially related to under-five mortality (U5M) in Egypt. This framework examines factors contributing to the risk of child mortality in developing nations. This framework consolidated social and medical research on child health, positing that social and economic factors influence a series of proximate (intermediate) determinants, which directly endanger children’s lives. The framework identifies three levels of socioeconomic factors: (I) individual, (II) household, and (III) community, which operate through five sets of proximate determinants of childhood health: (1) maternal factors, (2) environmental contamination, (3) nutrient deficiency, (4) personal illness control (e.g. personal preventive measures; medical treatment), and (5) injury. shows the set of socioeconomic and proximate determinants that pose risk to child health according to the framework adopted from Mosely and Chen (Mosley & Chen, Citation1984).

Figure 1. The conceptual framework adapted from Mosley and Chen (Citation1984).

3. Data source and methods

This article uses cross-sectional data on child mortality from Egypt's Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) in 2014. The EDHS includes face-to-face interviews with a representative sample of women between 15 and 49 years old in six major subdivisions in Egypt (Urban Governorates, urban Lower Egypt, rural Lower Egypt, urban Upper Egypt, rural Upper Egypt, and the Frontier Governorates). The dataset for children is used for this article, which contains 15,848 observations from mothers with a child born in the five years preceding the survey. The dataset includes information related to child health indicators and on mothers’ educational background, place of residence, and other related socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (EDHS, Citation2015).

For the 2014 EDHS, a four-stage sampling process was utilised. Initially, 926 Primary Sampling Units (PSU) from urban and rural areas were listed. These units were sectioned based on population sizes, with varying numbers of parts selected for large, medium, and small towns. These parts were then divided into nearly equal-sized segments. From this process, a systematic representative sample of 29,471 households was chosen, and all ever-married women between 15 and 49 years in these households were eligible for individual interviews (EDHS, Citation2015). More details about the survey are available from the DHS (EDHS, Citation2015).

The selection of socioeconomic and proximate variables for our analysis was guided by the Mosely and Chen Framework, and these specific variables are detailed in . The socioeconomic factors include the educational levels of both parents, which were categorised into four groups: no education, primary, secondary, and university. Additionally, we considered the mother's employment status (whether the mother is employed or not), the mother's religion (categorised as Muslim or other), and the mother's marital status (either married or not). The EDHS did not gather direct income data, but rather developed a wealth index derived from various household assets while adjusting for urban-rural disparities. This index considered the availability of several assets, such as electricity, car, motorcycle, refrigerator, radio, TV, and the type of flooring, following the approach of Rutstein and Johnson (Citation2004). Based on the presence of these assets, households were assigned scores, which the EDHS team then used to segregate them into five wealth brackets: poorest, poor, middle, rich, and richest (EDHS, Citation2015).

Table 1. Description of study variables.

The proximate/intermediate variables are determined according to the frameworks as well. Starting with maternal factors, the mother’s age and birth spacing are categorised into three groups (below 20, between 20 and 40, above 40 years old; 1 birth in the last five years, 2 births, 3 or more births). Also included is the mother’s age at the first birth. Nutritional and biological factors include if the child ever breastfed, the size of the child at birth (larger than average, average, smaller than average), and the child’s sex. In the personal illness category, variables include whether the mother has health insurance, the place of delivery. This article uses water source (protected or unprotected), and sanitary system (improved or unimproved) as environmental factors.

This research employed logistic multivariate regression analysis to estimate the association of the identified factors with U5M as per EDHS 2014. In the following model, the dependent variable is the U5M, which is coded as one if the child dies before the age of five and zero if the child is still alive.

The independent variables are: X is a vector for socioeconomic characteristics that includes parents’ education, location, and wealth status, and mother’s marital status, occupation, and religion. Y is a vector for biological and nutritional factors, including breastfeeding, child size at birth, and child sex. M represents the vector of maternal characteristics and personal illness control factors and includes the number of births in the 5 years preceding the study, mother’s age, mother’s age at the first birth, place of delivery, and the mother’s health insurance status. Vector E is environmental factors (i.e. source of water, and sanitary system).

summarises the distribution of all, urban, and rural mothers according to their socioeconomic characteristics and proximate determinants. Around 60% of the respondents live in rural regions while the rest are in urban areas. The table illustrates that more than 50% of mothers and their partners completed the secondary educational level. However, while only 9.2% of urban mothers are uneducated, 22.4% of mothers in rural areas are. Concerning the mother’s wealth index, 33% and 53% of richer and the richest mothers, respectively, reported living in urban areas. In contrast, there are no rural mothers in the richest group and only 13% in the richer category. Of the remaining rural mothers, 27% are in the poorest category, 29% are poorer, and 31% are in the middle. These descriptive statistics indicate that women in rural areas tend to be poorer and less educated in general, compared to those in urban areas of Egypt ().

Table 2. The summary statistics for all, urban, and rural households.

Table 3. The results for socioeconomic variables for all households (odds ratios).

The majority of all mothers were married, not working, and between 20 and 40 years old. Most of the respondents had one or two children in the five years before the interview and had given birth in a medical health facility. Forty-six per cent of the children were breastfed. Around 52% of mothers had a female child. More than 80% of children had an average weight at birth. Turning to environmental variables, the majority of residents reported an on-premises protected source of water and improved sanitary facilities. Lastly and interestingly, almost all households with no toilets were reported in the rural areas.

4. Results

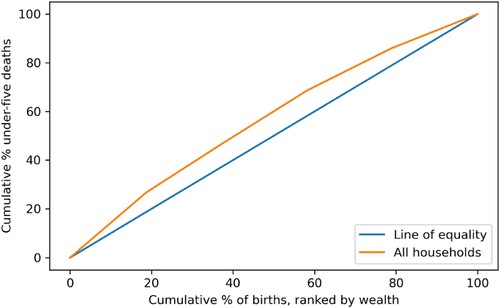

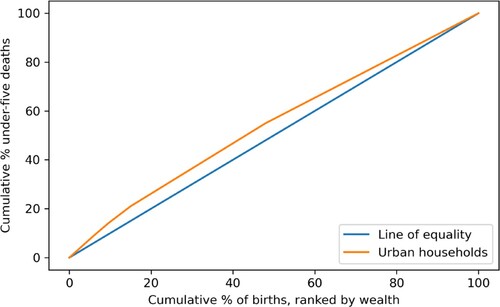

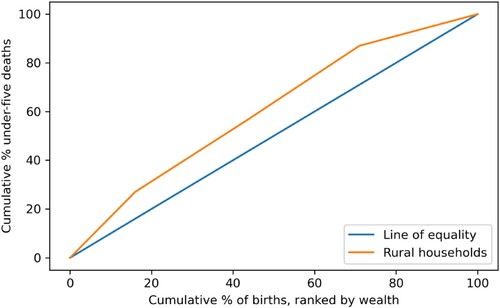

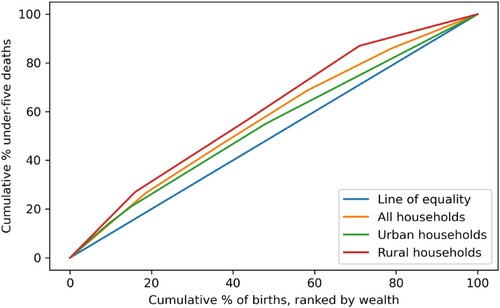

represent concentration curves (CC) that plot for the cumulative percentage of under-five deaths against the cumulative percentage of births ranked by living standards in five wealth groups from poorest to richest groups for the EDHS data from 2014 (Wagstaff et al., Citation2007). The CC is plotted for all households in , and for urban and rural households separately in and , respectively. shows that the CC for all households lies above the line of inequality, indicating that U5M is concentrated among poor groups. Additionally, and 4 indicated that this is also the case considering the CC of child mortality in urban and rural families separately.

provides a visual assessment of the differences in child mortality across Egypt in 2014. It shows that the rural curve lies above the urban curve indicating more inequality among mothers from rural areas than in urban areas. In spite of the evidence that the CC of infant mortality disparity in Egypt narrowed from 1995 to 2014 in the study of Sharaf and Rashed in 2018. This study shows that the burden of the child mortality in Egypt is not only concentrated among the poor families but also among the families who live in the rural areas in Egypt.

We first analysed the association of socioeconomic determinants with child mortality. The analysis indicates that the level of a mother's education has a significant association with U5M. Children born to mothers with higher education have a substantially lower risk of U5M compared to children born to uneducated mothers (OR = 0.59. p-value = 0.039). Household wealth status also plays a significant role in U5M rates. Children from the poorest families have a higher risk of U5M compared to children from ‘richest’ families (OR = 0.61, p-value = 0.053). This suggests that economic disparities and the associated proximate factors – such as access to healthcare and living conditions – significantly contribute to the risk of U5M ().

Geographical disparities were evident in U5M rates. Children from rural areas in Upper Egypt experience a higher risk of U5M compared to children from urban governorates. This suggests that there are key regional disparities in terms of access to and quality of healthcare, sanitation, and nutritional services. These results are consistent with the theoretical model and the evidence in the literature.

Next, we analysed the association of child mortality with both socioeconomic and proximate variables in the same model. The results of the logistic multivariate regression analysis are shown in , the model was estimated using all households first, and then it was estimated for urban and rural households separately. The findings show evidence of the association between mother’s and father’s education and child health, e.g. both are significantly associated with U5M. First, mothers with higher education are 40% less likely to experience the death of a child under five compared with uneducated mothers (OR = 0.6 and p-value = 0.065). Regarding the father’s education, there is evidence of a positive association between the father’s level of education and child health. Fathers with primary education level experience 37% less U5M compared with uneducated fathers (OR = 0.62 and p-value = 0.032). In comparison, other socioeconomic factors that show insignificant association with U5M risk were wealth, place of residence (the reference group is frontier governorates), religion, marital status and mother’s occupation. Therefore, among the various socioeconomic factors included here, mothers with higher levels of education consistently experience less child loss.

Table 4. The results for all households, urban and rural regressions (odds ratios).

Turning to maternal factors, both mother’s age at the time of the interview and birth interval were significantly associated with child loss. Mothers aged 20–40 were 66% less likely to experience U5M compared with those under 20years of age (OR = 0.34 and P-value = 0.002); Likewise, the analysis shows an association between the number of births in the five years before the survey and child health. Compared with the reference group of mothers with four or above births in the last five years, mothers with one and two births in the last five years had 97% and 92% less chance of experiencing U5M risk, respectively. Similarly, U5M is 60% less likely for mothers with three births in the previous five years. Having a child before the mother is 20 years old and short birth spacing are positively associated with under-five death.

The association between breastfeeding and child survival is as expected. The U5M risk is 69% less among children who had ever breastfed. The odds ratio of breastfeeding children is 0.31 (P-value = 0.000) compared with children who never breastfed. As for child size, the reference group is larger than average weight. The risk of U5M among children with average birth weight is 66% less chance of death than the children weighed above average (OR = 0.34 and P-value = 0.000). While there was no evidence to risk U5M if the child weighed less than average.

Turning to health services utilisation variables labelled ‘personal illness’ according to Mosley and Chen’s framework, there were no significant associations between either the presence of health insurance or place of delivery and child morality in the main model which includes all households. However, the findings show that whether the mother had health insurance or not had a significant association with U5M for households living in rural areas.

For the environmental factors, having improved toilet facilities is associated with a reduced risk of U5M. U5M risk in households with improved toilet facilities is 69% less than in families with unimproved toilet services (OR = 0.310 and P-value = 0.033). Though there is a significant association between improved toilet services and U5M risk, the impact of safe water sources on U5M is not statically significant.

Considering urban and rural households separately, higher levels of mother’s and father’s education were associated with lower U5M risk in both urban and rural areas. In particular, mothers with secondary education were 35% less likely to experience child loss than uneducated mothers in rural areas (OR = 0.65 and P-value = 0.021), while urban mothers with higher education were 60% less likely to experience U5M than uneducated mothers (OR = 0.4 and P-value = 0.069). Additionally, fathers with primary education in urban areas experienced lower U5M than uneducated fathers (OR = 0.5 and P-value = 0.096). Even though wealth quintile was not significantly associated with U5M for all households, the results were different when urban and rural households were examined separately. The findings indicate that more affluent households in rural areas were significantly less likely to experience child loss compared with the reference group of poorest category.

Considering the urban and rural regressions separately, the significant association of mother’s age with U5M risk was found among mothers in urban and rural areas. Similarly, the significant role of short birth spacing was clear among mothers who live in rural areas. For instance, mothers with one, two, or three births in the last five years were less likely to experience U5M compared with mothers with four or more births in the last five years. As expected, breastfeeding and child size are significantly associated with U5M for both rural and urban mothers. Mothers in urban and rural areas who reported that their child was ever breastfed have a 62% and 70% lower likelihood of experiencing under-five mortality (U5M), respectively.

Interestingly, the findings show that possession of health insurance coverage had a significant association with child survival (OR = 0.272 p = 0.036) in rural areas. Place of delivery is not significantly associated with U5M in either urban and rural areas. Turning to the environmental variables, mothers in rural areas with improved toilet services were 71% less likely to experience U5M compared to rural mothers with unimproved toilet services (with p-value = 0.025). However, type of water sources was still not significantly associated with U5M when urban and rural households were considered separately.

5. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without its limitations. A primary limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the data which limits our ability to infer causality or understand temporal relationships. For instance, while we have analysed the relationship between socioeconomic factors and child mortality, we cannot assert that a lack of education causes increased child mortality. Additionally, there is a potential for recall bias. Another limitation is that the indirect measurement of wealth indices which are derived from proxy variables, might not fully capture ‘wealth’. The self-reported nature of data can be affected by social desirability bias, with respondents providing socially acceptable answers rather than entirely factual ones. Lastly, while the EDHS is rich in individual and household-level data, it lacks some variables related to health care utilisation that would have been helpful for our analysis.

6. Discussion

6.1. Socioeconomic determinants

6.1.1. Education

This study reveals that in both rural and urban areas of Egypt, parents with higher education levels are less likely to experience child loss. This finding is consistent with a previous study focusing on rural Egypt, which identified parental literacy as a major determinant of child mortality based on verbal autopsies with mothers who had lost children (Yassin, Citation2000). Similar observations regarding the positive impact of parental education on child health have been made in numerous international studies. For instance, Koffi et al.'s, Citation2017 research using data from the 2013 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey highlighted that a significant number of child deaths occurred in the country's northern region, where 72.5% of the deceased children's mothers had no education and lived in impoverished conditions (Koffi et al., Citation2017). Several other studies from different countries also echo this association (Afshan et al., Citation2020; Chowdhury et al., Citation2020; Fenta & Nigussie, Citation2021; Hussein et al., Citation2021; Kanmiki et al., Citation2014; Nattey et al., Citation2013; Van Malderen et al., Citation2019; Vikram et al., Citation2012).

Additionally, a global systematic review and meta-analysis examined the relationship between parental education levels and child mortality worldwide. Drawing from 300 studies across 92 countries, including primary analyses of Demographic and Health Survey data, the research found a clear link between increased maternal and paternal education and reduced under-5 mortality. Children born to mothers with completed secondary education (12 years) had a 31% lower risk of mortality, while the same education level in fathers resulted in a 17.3% decrease, compared to parents with no education (Balaj et al., Citation2021). The evidence from our study combined with international literature overwhelmingly emphasises the importance of education as a social determinant of health.

6.1.2. Wealth

In the regression model that considered only socioeconomic determinants, as well as in the comprehensive model which included all socioeconomic and proximate variables in rural areas, the wealth quintile proved to be a significant factor. However, this significance was exclusively observed in the model for rural areas but not in the comprehensive model that includes all households. The influence of household wealth might not be evident in the full model, possibly due to the indirect impact of wealth on health being mediated by proximate variables. These proximate variables, like access to health services and improved living conditions, could be the mechanisms through which income and wealth exert their effects on health. The results of other studies examining similar socioeconomic factors find mixed results with some studies finding household’s wealth and residence to be associated with U5M. (Adeolu et al., Citation2016;Ettarh & Kimani, Citation2012; and Ezeh et al., Citation2021) and other studies finding these variables not significantly associated with child mortality (Imbo et al., Citation2021; Kanmiki et al., Citation2014; and Ahinkorah et al., Citation2022).

6.1.3. Rural urban divide

Our findings indicate that mothers who live in rural areas experience more child loss than those living in urban areas. In this study even though most factors impacted U5M in both rural and urban areas similarly, there were key differences between the rural and urban models. Wealth quintile only mattered in rural areas in the full model including proximate variables. Also, access to health insurance was significantly associated with child survival in rural areas but not significantly in urban areas. Further research is needed to understand this finding. In addition, an examination of which type of insurance appears to be effective in reducing the U5M within urban and rural regions would be beneficial.

Consistent with our findings regarding family’s wealth, a study by Sharaf and Rashad (Citation2018) exploring infant mortality trends in rural Egypt from 1994 to 2014 using repeated cross-sectional data found that while there was a substantial decrease in infant mortality, from 63 deaths per 1000 live births in 1995 to 22 in 2014, the poorest wealth quintile still had infant mortality rates double those of the wealthiest quintile in 2014 (Sharaf & Rashad, Citation2018). Our study further reinforces that low-income households in rural Egypt face the highest risks of child loss. Both studies underscore the pressing need to address health disparities rooted in socioeconomic factors in rural areas.

Inequities in child mortality can and should be addressed and evidence from other countries suggests that it is possible if the right policies are in place. Vapattanawong et al. (Citation2007) in a study using Thailand's census data from 1990 to 2000 show a significant reduction in child mortality rates. The study also revealed that while most families experienced better conditions, it was the poorest who saw the biggest drop in child deaths. The gap in death rates between the wealthiest and poorest narrowed by 55%. This success was driven by Thailand's economic growth, broader insurance coverage, and more even distribution of essential healthcare. Improving equitable access to healthcare services in Egypt, especially in rural areas, through an expanded and enhanced health insurance system, could help address inequities.

6.2. Proximate/intermediate determinants

6.2.1. Maternal health factors

In this study, maternal health factors such as age and birth spacing were associated with under-five mortality (U5M). Mothers older than 20 years were less likely to experience child loss, and having fewer children in recent years served as a protective factor against child loss. These findings are consistent with the evidence in the literature from Egypt, Jordan, Kenya and Nigeria (Blackstone et al., Citation2017; Ettarh & Kimani, Citation2012; Hussein et al., Citation2021; Kaldewei, Citation2010). Maternal health factors were also associated with child mortality in other studies in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nigeria (Abir et al., Citation2015; Fenta & Nigussie, Citation2021; Gebretsadik & Gabreyohannes, Citation2016 and Ezeh et al., Citation2022).

6.2.2. Nutritional factors

In our study, the nutritional aspects of both breastfeeding and birthweight were found to be significant. Children who were ever breastfed had a lower likelihood of dying in childhood. Similarly, in Jordan, a study by Kaldewei in 2010 revealed that not only breastfeeding is important for child health but also the duration of breastfeeding plays a significant role in reducing child mortality. This finding is similar to Abou-Ali (Citation2003) study in Egypt using EDHS 1995 data, as well as Ettarh and Kimani (Citation2012), Bello and Joseph (Citation2014), Kanmiki et al. (Citation2014), Ayele et al. (Citation2022) and Gebretsadik and Gabreyohannes’s (Citation2016) studies.

6.2.3. Environmental factors

As for environmental factors, having improved toilet facilities was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of experiencing child loss. Previous studies reached the same conclusion on the association between improved toilet services and child health in Egypt. (Abou-Ali, Citation2003 and Aly, Citation1991). Conversely, the influence of safe water sources on under-five mortality (U5M) was not statistically significant in our study.

The insignificant association between water source and child health was also found in a previous study from Egypt (Sharaf & Rashad, Citation2018) and Ethiopian studies (Shifa et al., Citation2018 and Regassa, Citation2012). However, studies from other countries have found significant associations between access to clean w ater and child health. In 2020, Tusting et al. and Yang et al. found an increased risk posed by unprotected water sources and sanitation on child health in the Sub-Saharan Africa region (Tusting et al., Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2020). Additionally, improvements in water and sanitation services were reported to be associated with child survival in Bangladesh and Jordan (Khan et al., Citation2023 and Kaldewei, Citation2010) and in many other studies (Adeolu et al., Citation2016; Gebretsadik & Gabreyohannes, Citation2016; Paul, Citation2020).

7. Conclusion and policy implications

The findings of this study indicate that the social of determinants of health are at the root of the inequities in U5M mortality we observe in Egypt. In our study, factors such as lower education, early childbearing, insufficient birth spacing, lack of breastfeeding, and absence of improved toilet facilities were all significantly linked to an increased likelihood of child loss. Notably, women from rural areas bore a higher burden of this loss.

In 2010, The World Health Organization (WHO) put forth the Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). This framework is based on social production of health/illness theories, and it posits that inequities in health outcomes are rooted in social factors which are grouped into structural determinants, produced by the socioeconomic and political context, which lead to intermediary determinants of health. The structural determinants include factors such as gender, racial, educational, occupational and income statuses. These factors then produce the intermediate determinants such as material circumstances (living and working condition, food availability, etc.), behaviours, biological and psychological factors (Solar & Irwin, Citation2010). Hence, the CSDH proposes that action to reduce inequities in health should not only target the intermediate factors but also target the more upstream factors.

Empirical evidence confirms the importance of the social determinants of health for child health. Bishai et al. (Citation1990) investigated the factors behind the decline in maternal and child mortality in 146 low- and middle-income countries from 1990 to 2010. Their research found that while the significance of individual determinants varied by country, about half of the mortality reductions were attributed to advancements within the health sector. The remaining half resulted from progress made outside the health sector. Our findings point in the same direction and indicate that inequities in health are rooted in social inequities.

Both our findings and the broader literature emphasise that interventions targeting the upstream determinants of health, particularly inequities in income and education, have the potential for the greatest impact in addressing disparities in child mortality. While Egypt has seen a significant reduction in child mortality rates, stark inequities persist, with the poorest women in rural areas experiencing the gravest outcomes. As such, increasing investment in education and tailoring public health campaigns to parents with minimal educational attainment can be effective strategies to lower child mortality.

Focusing on the upstream determinants does not mean ignoring the proximate/intermediate determinants. Our findings underscore the significance of breastfeeding, birth spacing, child size, and maternal age on under-five child mortality in Egypt. Hence, building on our findings, public health programmes that focus on promoting breastfeeding and birth spacing can play a crucial role in improving under-five children’s health. This paper also highlights disparities between urban and rural areas in Egypt, with higher child mortality rates among rural mothers using unimproved toilet facilities. Enhancing sanitation, particularly toilet facilities, and educating communities on hygiene practices in rural areas could significantly improve child health outcomes.

Building on successful programmes in Egypt such as The Integrated Management for Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) could also be an effective strategy. Rakha et al. (Citation2013) analysed data from vital registration to evaluate the effect of IMCI implementation from 2000 to 2006 on child mortality. Their findings indicate a significant association between IMCI implementation and a twofold increase in the annual reduction rate of under-five mortality (from 3.3% to 6.3%). This result is supported by enhancements in the quality of care for ill children in health facilities that adopted IMCI.

Implementing policies that address both the upstream social and intermediate determinants of child mortality, while capitalising on existing successful programmes, may provide the most effective solution for improving child health outcomes and narrowing disparities in child mortality in Egypt. There is a pressing need for policies grounded in evidence; therefore, future research that evaluates the impact of various policies could be highly influential.

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere gratitude to the DHS for availing the dataset that was used in this study. Author M. A. expresses grateful for Society of Friends GdF of the Thünen Institute for their support in presenting this research at the UNICEF conference. Author M. A. is also grateful for the assistance of the UNICEF team and for the faculty of economics and political science of Cairo University who provided support in presenting this work and offering valuable feedback. All the authors contributed to all phases of the manuscript preparation and approval of final draft for submission. M. A.: conceptualized the study, conducted the data analysis, and co-authored the paper. M. F.: conducted the formal analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript, and co-authored the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Since birth weight is not always known for babies, a question was included to obtain the mother’s estimate of the baby’s size for all babies, i.e. whether the baby was very small, smaller than average, or average or larger. This assessment is based on the mother’s own perception of what is a small, average, or large baby and not on a uniform definition.

2 Government medical facilities include urban and rural hospitals, urban and rural health units, etc. The private medical facilities include private hospital/clinic, private doctor. The nongovernmental has Egypt family planning association, csi project and other NGOs.

3 Protected source of drinking water: piped into dwelling, to yard or plot, Public tap or standpipe, tube well or borehole, protected well, spring, truck, cart with small tank, bottled water. Unprotected source of drinking water: unprotected well, spring, surface water like river, dam, lake, ponds, stream and canal and other.

4 Improved sanitation are flush to piped sewer system, to septic tank, to vault (bayara), to pipe connected to canal, to pipe connected to ground water. Unimproved sanitation are flush to somewhere else, pit latrine, without slab or open pit, bucket toilet and others, no facility.

References

- Abir, T., Agho, K. E., Page, A. N., Milton, A. H., & Dibley, M. J. (2015). Risk factors for under-5 mortality: evidence from Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2004–2011. BMJ Open, 5(8), e006722. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006722

- Abou-Ali, H. (2003). The effect of water and sanitation on child mortality in Egypt. rapport nr.: Working Papers in Economics, (112).

- Adeolu, M., Akpa, O. M., Adeolu, A. T., & Aladeniyi, I. O. (2016). Environmental and socioeconomic determinants of child mortality: evidence from the 2013 Nigerian demographic health survey. American Journal of Public Health Research, 4(4), 134–141.

- Afshan, K., Narjis, G., Qureshi, I. Z., & Cappello, M. (2020). Social determinants and causes of child mortality in Pakistan: Analysis of national demographic health surveys from 1990 to 2013. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 56(3), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14670

- Ahinkorah, B. O., Budu, E., Seidu, A. A., Agbaglo, E., Adu, C., Osei, D., Banke-Thomas, A., & Yaya, S. (2022). Socio-economic and proximate determinants of under-five mortality in Guinea. PLoS One, 17(5), e0267700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267700

- Aly, H. Y. (1991). Egyptian child mortality: A household, proximate determinants approach. Journal of Developing Areas, 25(4), 541–552.

- Ayele, B. A., Abebaw Tiruneh, S., Azanaw, M. M., Shimels Hailemeskel, H., Akalu, Y., & Ayele, A. A. (2022). Determinants of under-five mortality in Ethiopia using the recent 2019 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data: nested shared frailty survival analysis. Archives of Public Health, 80(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00896-1

- Balaj, M., York, H. W., Sripada, K., Besnier, E., Vonen, H. D., Aravkin, A., Friedman, J., Griswold, M., Jensen, M. R., Mohammad, T., Mullany, E. C., Solhaug, S., Sorensen, R., Stonkute, D., Tallaksen, A., Whisnant, J., Zheng, P., Gakidou, E., & Eikemo, T. A. (2021). Parental education and inequalities in child mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 398(10300), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00534-1

- Bello, R. A., & Joseph, A. I. (2014). Determinants of child mortality in Oyo state, Nigeria. African Research Review, 8(1), 252–272. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v8i1.17

- Bishai, D. M., Cohen, R., Alfonso, Y. N., Adam, T., Kuruvilla, S., & Schweitzer, J. (1990). Factors contributing to maternal and child mortality reductions in 146 low-and middle-income countries between. PLoS One, 11(1).

- Blackstone, S. R., Nwaozuru, U., & Iwelunmor, J. (2017). An examination of the maternal social determinants influencing under-5 mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic Health Survey. Global Public Health, 12(6), 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1211166

- Chowdhury, A. H., Hanifi, S. M. A., & Bhuiya, A. (2020). Social determinants of under-five mortality in urban Bangladesh. Journal of Population Research, 37(2), 161–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-019-09240-x

- Egypt Demographic and Health Survey EDHS, Ministry of Health and Population (Egypt), El-Zanaty and Associates (Egypt), and ICF International. (2015). Egypt demographic and health survey 2014. Ministry of Health and Population and ICF International.

- Ettarh, R. R., & Kimani, J. (2012). Determinants of under-five mortality in rural and urban Kenya. Rural and Remote Health, 12(1), 3–11.

- Ezeh, O. K., Odumegwu, A. O., Oforkansi, G. H., Abada, U. D., Ogbo, F. A., Goson, P. C., Ishaya, T., & Agho, K. E. (2022). Trends and factors associated with under-5 mortality in northwest Nigeria (2008–2018). Annals of Global Health, 88(1), 51–63.

- Ezeh, O. K., Ogbo, F. A., Odumegwu, A. O., Oforkansi, G. H., Abada, U. D., Goson, P. C., Ishaya, T., & Agho, K. E. (2021). Under-5 mortality and Its associated factors in northern Nigeria: Evidence from 22,455 singleton live births (2013–2018). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9899. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189899

- Fenta, S. M., & Nigussie, T. Z. (2021). Factors associated with childhood diarrheal in Ethiopia; a multilevel analysis. Archives of Public Health, 79(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00513-z

- Gebretsadik, S., & Gabreyohannes, E. (2016). Determinants of under-five mortality in high mortality regions of Ethiopia: an analysis of the 2011 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey data. International Journal of Population Research, 2016, 7. Article ID 1602761.

- Hussein, M. A., Mwaila, M., & Helal, D. (2021). Determinants of under-five mortality: A comparative study of Egypt and Kenya. Open Access Library Journal, 8(9), 1–23.

- Imbo, A. E., Mbuthia, E. K., & Ngotho, D. N. (2021). Determinants of neonatal mortality in Kenya: evidence from the Kenya demographic and health survey 2014. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS, 10(2), 287.

- Kaldewei, C. (2010). Determinants of infant and under-five mortality – the case of Jordan. Technical note, February.

- Kanmiki, E. W., Bawah, A. A., Agorinya, I., Achana, F. S., Awoonor-Williams, J. K., Oduro, A. R., Phillips, J. F., & Akazili, J. (2014). Socio-economic and demographic determinants of under-five mortality in rural northern Ghana. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 14(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-14-24

- Khan, G. R., Baten, A., & Azad, M. A. K. (2023). Influence of contraceptive use and other socio-demographic factors on under-five child mortality in Bangladesh: semi-parametric and parametric approaches. Contraception and Reproductive Medicine, 8(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-023-00217-z

- Koffi, A. K., Kalter, H. D., Loveth, E. N., Quinley, J., Monehin, J., & Black, R. E. (2017). Beyond causes of death: The social determinants of mortality among children aged 1-59 months in Nigeria from 2009 to 2013. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177025

- Mosley, W. H., & Chen, L. C. (1984). An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Population and Development Review, 10, 25–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/2807954

- Nattey, C., Masanja, H., & Klipstein-Grobusch, K. (2013). Relationship between household socio-economic status and under-five mortality in Rufiji DSS, Tanzania. Global Health Action, 6(1), 19278. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.19278

- Paul, P. (2020). Child marriage and its association with morbidity and mortality of children under 5 years old: Evidence from India. Journal of Public Health, 28(3), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01038-8

- Rakha, M. A., Abdelmoneim, A. N. M., Farhoud, S., Pièche, S., Cousens, S., Daelmans, B., & Bahl, R. (2013). Does implementation of the IMCI strategy have an impact on child mortality? A retrospective analysis of routine data from Egypt. BMJ Open, 3(1), e001852. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001852

- Regassa, N. (2012). Infant mortality in the rural sidama zone, southern Ethiopia: Examining the contribution of key pregnancy and postnatal health care services. Journal of Nursing, Social Studies, Public Health and Rehabilitation, 1(2), 51–61.

- Rutstein, S. O., & Johnson, K. (2004). The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports no. 6. ORC Macro.

- Sharaf, M. F., & Rashad, A. S. (2018). Socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality in Egypt: analyzing trends between 1995 and 2014. Social Indicators Research, 137(3), 1185–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1631-3

- Shifa, G. T., Ahmed, A. A., & Yalew, A. W. (2018). Socioeconomic and environmental determinants of under-five mortality in Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A matched case control study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-018-0153-7

- Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services.

- Tusting, L. S., Gething, P. W., Gibson, H. S., Greenwood, B., Knudsen, J., Lindsay, S. W., & Bhatt, S. (2020). Housing and child health in sub-Saharan Africa: A cross-sectional analysis. PLoS Medicine, 17(3), e1003055. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003055

- Van Malderen, C., Amouzou, A., Barros, A. J., Masquelier, B., Van Oyen, H., & Speybroeck, N. (2019). Socioeconomic factors contributing to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: A decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7111-8

- Vapattanawong, P., Hogan, M. C., Hanvoravongchai, P., Gakidou, E., Vos, T., Lopez, A. D., & Lim, S. S. (2007). Reductions in child mortality levels and inequalities in Thailand: analysis of two censuses. The Lancet, 369(9564), 850–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60413-9

- Vikram, K., Vanneman, R., & Desai, S. (2012). Linkages between maternal education and childhood immunization in India. Social Science & Medicine, 75(2), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.043

- Wagstaff, A., O'donnell, O., Van Doorslaer, E., & Lindelow, M. (2007). Analyzing health equity using household survey data: A guide to techniques and their implementation. World Bank Publications.

- World Health Organization. (2022). World health statistics 2022: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals, 7. p. 25.

- Yang, D., He, Y., Wu, B., Deng, Y., Li, M., Yang, Q., Huang, L., Cao, Y., & Liu, Y. (2020). Drinking water and sanitation conditions are associated with the risk of malaria among children under five years old in sub-Saharan Africa: a logistic regression model analysis of national survey data. Journal of Advanced Research, 21, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2019.09.001

- Yassin, K. M. (2000). Indices and sociodemographic determinants of childhood mortality in rural Upper Egypt. Social Science & Medicine, 51(2), 185–197. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00459-1