ABSTRACT

Following landmark legislation in 2013, Uruguay became the first country to regulate the legal production, distribution and sale of recreational cannabis. While broader debates anticipated the significance of the UN drug conventions, the extent to which Uruguay’s drug treaty obligations shaped regulation is unclear and the relevance of finance norms has been neglected. Drawing on institutionalist and governance theories, this study explores how international drug and finance regulations limited Uruguay’s policy space to implement cannabis regulation, and how this was perceived by policy actors. Policy documents and 43 semi-structured interviews were thematically analysed. The analysis demonstrates how Uruguay’s drug treaty obligations were less directly constraining to policy space compared to international finance norms, including the US Patriot Act, anti-money laundering standards and financial inclusion practices. Such norms exerted powerful influence over Uruguay’s ability to implement aspects of cannabis supply that interact with broader financial systems, allowing banks to terminate business relationships with clients deemed as high risks for money laundering. The Uruguayan case suggests that financial regulations at diverse levels are likely to constrain policy space in other contexts where the market-based policies of cannabis regulation raise tensions with a narrowly constructed risk management principle in approaches to financial supply.

Introduction

Following landmark legislation in 2013, Uruguay became the first country to comprehensively regulate the legal production, distribution and sale of recreational cannabis. Uruguay’s Marihuana Regulation Act has been widely recognised for its innovation and leadership (Baudean, Citation2021; Walsh & Ramsey, Citation2018) and depicted as a model of health governance for other countries (von Hoffmann, Citation2018). This regulatory strategy was intended to be far reaching, liberalising access of cannabis to residents (18 and older) via home cultivation, cannabis clubs and commercial sales through pharmacies. Passage of Uruguay’s comprehensive cannabis legislation represented a seminal moment in international drug policy and a point of departure from the conservative approach of the global drug control regime, which has focused on repressive measures directed at producers, traffickers and consumers of illegal substances within an overall prohibitionist framework (Bewley-Taylor et al., Citation2020).

However, between 2014 and 2018, Uruguay struggled to develop a national production system, and widespread supply shortages and delayed implementation of cannabis sales were salient issues (Cerda & Kilmer, Citation2017; Queirolo, Citation2020). First, it took Uruguayan authorities 20 months to evaluate and verify the applications and financial records of 22 cannabis firms, resulting in only two companies being identified as qualified to receive national production licenses in October 2015 (Walsh & Ramsey, Citation2018). This was followed by nearly two years of Uruguay struggling to meet public demand for legal cannabis, in part, due to issues that the cannabis production companies had faced in securing access to lending and banking services (Mander, Citation2020).

Although commercial sales were eventually implemented in July 2017, Uruguayan regulators were soon confronted with unexpected challenges. In response to threats by US and other foreign financial institutions, several Uruguayan banks have refused to offer financial services to pharmacies legally authorised to sell recreational cannabis. Alleging that cannabis regulation conflicted with international drug and finance norms of other countries in which they operate, banks from the US and other leading markets contended that they were required to terminate their financial relationships with Uruguayan banks linked to the sale of cannabis (Gaudán, Citation2017). Concerned with the risk of losing access to foreign financial services, Uruguayan banks promptly warned pharmacy owners that if they did not cease from selling recreational cannabis, they would close their bank accounts immediately (Londoño, Citation2017). This issue is not Uruguay-specific, however. Cannabis companies in the US states (Hill, Citation2015), Canada (Crabb, Citation2019) and Jamaica (Bewley-Taylor et al., Citation2020) have also struggled to secure and maintain access to basic financial services from banks, despite the newfound legality of cannabis (both recreational and medical) in these jurisdictions. This underlines the wider implications of international financial regulations and thus explains, in part, the power of international banks to constrain implementation of cannabis policy innovation.

Most studies in the field have tended to focus on issues of sovereignty and legal authority to explain how Uruguay was able to pass cannabis legislation, despite apparently contravening its international drug treaty obligations. To date, Uruguay’s ability to overcome the limitations of the UN drug conventions has been widely linked to the apparent consistency between cannabis regulation and wider obligations under international human rights law (Musto, Citation2018; Walsh & Jelsma, Citation2019); the International Narcotics Control Board’s (INCB) lack of formal police power to enforce treaty compliance (Hawken & Kulick, Citation2014); and the US government’s alleged reluctance to intervene in Uruguay’s policy deliberations (von Hoffmann, Citation2018). In this context, Uruguay’s ‘success recently in walking away from’ (Conti-Brown, Citation2018) its international drug treaty obligations has been widely attributed to the largely symbolic nature of these conventions (Hawken & Kulick, Citation2014). Despite the global significance of Uruguay’s reform, very little attention has been paid to the international challenges to implement cannabis regulation. Consequently, existing studies neglect the significance of issues of power and autonomy in understanding how external pressures and constraints might limit Uruguay’s policy space to develop a legal cannabis market.

Policy space refers to the freedom, scope and mechanisms that governments have to choose, design and implement public policies to fulfil their aims’ (Koivusalo et al., Citation2009). Within global health, the concept of policy space primarily has been used to assess the impacts of trade agreements and the restrictions these can impose on the autonomy available to governments to make their own policy decisions (Koivusalo, Citation2014; Mayer, Citation2009). The public health literature has documented specific examples of the implications of international trade and investment agreements for health policy space (Garton et al., Citation2021; Koivusalo et al., Citation2009; Thow & McGrady, Citation2014) and has made invaluable contributions in terms of providing governments with proactive responses to preserve their regulatory autonomy. This conceptual approach recognises that ‘power, and its asymmetrical distribution between stakeholders’ play key roles in enabling such restrictions to occur (Garton et al., Citation2021). A focus on policy space provides innovative scope to explore the significance of complex interactions across national, intergovernmental and supranational decision-making processes, whereas the challenging and complex implementation phase suggests the need to explore the relevance of international finance norms.

Indeed, the legal regulation of a recreational cannabis market raises important tensions with Uruguay’s obligations under the UN drug conventions, namely the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (i.e. Single Convention) and the 1988 Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (i.e. the Trafficking Convention) (see ). However, Uruguayan regulators have emphasised the ongoing challenges to implement cannabis regulation arising from tensions with international financial regulations, including the US Patriot Act, the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the World Bank’s Financial Inclusion Initiative. In this context, Uruguay’s cannabis legislation applies to the production, distribution and sale of an internationally controlled substance that cannot be legally traded between countries, which is also governed by the norms and practices of international financial systems.

Figure 1. Overview of the international mechanisms governing the control of cannabis.

Although the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances is also part of the international drug control regime, its primary purpose is the international control of psychoactive drugs like methamphetamine and barbiturates (United Nations, Citation1971). It is not included in the current analysis due to its limited reference to interactions and tensions with Uruguay’s cannabis regulation.

Reflecting this broader political context, the current article also draws on the concept of ‘multi-level governance’ (MLG) to understand the ways in which interactions across drug and finance agendas create additional layers of complexity through which policies like cannabis regulation must navigate to be implemented. More specifically, I employ the concept of MLG to denote a process by which policy interdependencies may limit or remove decision-making power away from local regulators while simultaneously providing international actors such as private banks with broad scope over their internal practices and procedures. This includes, for example, the ability to limit access to lending and banking services for cannabis-related businesses or remove financial investment entirely. Complex multi-level systems, particularly highly integrated institutions such as the wider governance of international crime, highlight how policy decisions taken in one context can have important implications for the effectiveness of national policy instruments in another (Hawkins & McCambridge, Citation2021).

A focus on norms and practices offers a promising route to explore multiple, complex spheres of influence and how they interact, and the sanctioning mechanisms used by international actors to limit Uruguay’s cannabis policy space. Drawing on institutionalist and governance theories, informal institutions refer to ‘socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels’ (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004), where a diverse range of actors play critical roles in ‘interpreting and practising the agreed rules and norms and in implementing decisions’ (Tatenhove et al., Citation2006). In contrast to formal institutions and structures, informal constraints are often subtle and hidden, ranging from public condemnation, social exclusion and blacklisting to threats of criminal prosecution or economic sanctions (Shaffer, Citation2013; Sharman, Citation2008).

While informal institutions may subvert formal decision-making processes, they can also reinforce or substitute formal enforcement mechanisms by creating or strengthening incentives to comply with formal rules and procedures. Accordingly, they may carry out ‘much of the enabling and constraining’ (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004) of policy space that is widely attributed to formal institutional structures. Wider analyses of global financial governance highlight the importance of informal pressures in understanding policy decisions and outcomes (Helleiner, Citation1999), with the power and influence of non-binding commitments seen as shaped by significant financial and reputational costs associated with their non-compliance (Eggenberger, Citation2018).

This paper therefore focuses on the constraining effects of international policies and processes on cannabis policy space, namely their informal enforcement beyond officially sanctioned channels, and their underlying mechanisms. First, it examines the extent to which Uruguay’s international obligations and wider commitments have restricted the range of interventions available to achieve national policy aims or limited the ways in which these aims are met. Second, it explores how underlying economic and structural power imbalances (Jackson, Citation2021; Koivusalo et al., Citation2009) have fostered a policy environment that is conducive to external actions and conditions limiting Uruguay’s cannabis policy space. In the concluding discussion, the article situates Uruguay’s cannabis regulation within its broader political context, in which policy space is shaped by the risk management practices of international finance and significantly constrained by tangible risks of economic loss for banks that fail to comply with them.

Methods

This analysis emerges from a wider study of the political considerations that influenced Uruguay’s approach to cannabis regulation between 2005 and 2018. The wider project sought to develop a comprehensive understanding of how Uruguay’s cannabis regulation was designed, and its most distinctive provisions developed, through an exploratory, inductive approach. It was through this approach that tensions with international finance norms were identified by key gatekeepers and interviewees as the primary drivers of the constraints to Uruguay’s policy space to fully implement cannabis regulation between 2014 and 2018.

This article draws on 43 semi-structured interviews conducted in Montevideo, Uruguay between 2017-2018. Respondents comprised a wide range of backgrounds, perspectives and positions, including representatives of the Executive Branch, ministers and ex-ministers who had held positions relevant to cannabis regulation, e.g. Ministry of Public Health (MSP), legal and medical experts, domestic and international NGOs, international health and drug organisations and representatives of the cannabis industry, as illustrated in . Purposive sampling was used to identify potential interviewees who were actively engaged or participating on behalf of an organisation or government agency in the development of Uruguay’s cannabis regulation between 2007 and 2018. Additional participants were recruited using ‘snowball sampling’ by asking early participants their views on the people and organisations that they believed to be especially knowledgeable about international processes and policies relevant to the development of Uruguay’s cannabis regulation. This sampling strategy was selected to help locate people and organisations who may be further removed from the core problem but still relevant to certain aspects of implementation challenges.

Table 1. Interview participant characteristics.Table Footnote1

The analysis draws principally on interview accounts, but also uses documents to add additional contextual information to the overall narrative. Documentary sources consulted include position papers, reports and regulatory guidelines of relevant institutions including the Office of the President (Office of the President of Uruguay, Citation2023), the Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis (Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis, Citation2023), the Drug Control Board (Junta Nacional de Drogas, Citation2016), the Ministry of Public Health (Ministerio de Salud Pública, Citation2020) and the National Secretariat to Combat Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (SENACLAFT, Citation2018), the United Nations Drug Conventions (United Nations, Citation1961; United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, Citation1988), the Financial Action Task Force International Anti-money Laundering Standards (Financial Action Task Force, Citation1990) the World Bank’s Financial Inclusion Initiative (World Bank, Citation2020a) and the USA Patriot Act (Citation2001) and US federal Controlled Substances Act (1970). News reports about the implementation process and information gathered from the websites of non-governmental organisations identified as relevant to the policy process were also analysed.

Except for four interviews, most (n = 39) were conducted in Spanish and face-to-face. For the interviews not conducted in person, these were carried out with international experts via Skype and in English, as this was the native language of these participants. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and uploaded to Nvivo qualitative software for analysis using an iterative, thematic approach. Interviews were analysed alongside documentary data to identify the most relevant external pressures and obligations – based on the perceptions of interview participants – to Uruguay’s cannabis policy process, organised by international treaties, international norms and practices and extraterritorial impacts of national legislation in other jurisdictions. To enhance the robustness of this work, direct quotes from participants are presented in the findings. Note that interview accounts represent the views of individual officials or representatives and not that of a government agency or organisation. All interviewees signed a written consent and agreed to being digitally recorded. This study received ethical approval from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Social and Political Science.

Results

International treaties and conventions

It had been widely expected that passage of Uruguay’s cannabis legislation would be jeopardised by its international obligations under the UN drug conventions, which limit its legal production, distribution and sale exclusively to medical and scientific purposes. According to one Uruguayan official, ‘we had problems with the INCB, with the International Narcotics Control Board’, commenting that ‘legalising [cannabis] strongly clashed with the Conventions of Vienna and Uruguay is very respectful of its international participation because it is a small country’.

Although the INCB did attempt to intervene and stop Uruguayan efforts to introduce a regulated cannabis market (International Narcotics Control Board, Citation2013), interviewees viewed its informal pressure and effectiveness as limited. First, respondents felt that the UN drug treaties afford signatory states certain latitude, providing space for policymakers to regulate cannabis for the purpose of protecting public health. As one Uruguayan official noted, the 1961 Single Convention contains a ‘health and welfare’ exemption, which provided legitimate ground for Uruguay to experiment with and ultimately pass an alternative control model than the current international drug system could allow:

We understood we were complying with the spirit of the Conventions because, ultimately, it [cannabis regulation] was another mechanism of legislative control. That Convention was so broad that there were even countries who gave the death penalty for consuming cannabis. To us, this was a violation of human rights … we understood that other countries did not have the possibility of imposing their decision on us, which was sovereign. It was a decision of our country to improve access to public health for our citizens regarding their addictions. (government official)

The INCB somehow did not put Uruguay in violation. Something that both Bolivia and Uruguay have, a small exception by saying that this is a public health and human rights issue.

The politics of who else defends the Conventions [and] to a large extent, that is the United States. The US has created a much more relaxed control over – not their validity – but rather how far the Conventions can go and what behaviours to sanction. (legal expert)

Marijuana is on a more restrictive list than morphine. And we have a law that is inconsistent with that list … It’s the same that happened with the banks. Yes, this is legal. Yes, it is legal. But for them [the banks], it is illegal. (civil society)

International norms and practices around prevention of money laundering

Although the UN drug conventions are the only international drug control treaties, they also sit within a wider multilateral crime control regime. The key requirements and provisions of the 1988 Trafficking Convention have been embedded within the US Patriot Act, the FATF’s Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Standards and the World Bank’s Financial Inclusion Initiative, all of which appear to pose challenges to implementation of Uruguay’s cannabis legislation. This is notably the case with respect to the extraterritorial scope of the US Patriot Act (defined as the practice of one country enforcing its domestic laws inside another jurisdiction without prior authorisation (Arnold & Salisbury, Citation2019)). As noted below, the Act contains provisions that expand the US government’s extraterritorial reach over foreign banks that maintain correspondent banking arrangements with US financial institutions via tangible risks of economic sanctions for providing financial services to criminal organisations (USA Patriot Act, Citation2001).

US efforts to strengthen its international reach to combat financial crime have influenced the FATF to adopt stricter standards and procedures for its members (Alexander, Citation2002). The FATF is an independent intergovernmental body of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development that was established in 1989 by the G7 Heads of State (Financial Action Task Force, Citation1990). It guides implementation of the anti-money laundering provisions of the 1988 Trafficking Convention via its Forty Recommendations, which aim to globalise a comprehensive framework that countries should implement to combat money laundering and terrorist financing (Financial Action Task Force, Citation2019b).

The FATF has three different membership types: members (jurisdictions that represent most major financial centres), associate members (FATF-style regional organisations representing most low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs)) and observer organisations (intergovernmental organisations and financial groups) (Financial Action Task Force, Citation2019a). Uruguay is part of the associate member organisation, the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT), which works to ensure that its members strictly adhere to the FATF’s Forty Recommendations as the recognised international standard (Financial Action Task Force of Latin America, Citation2019). Regardless of membership type, all members are urged to endorse the FATF standards, including financial institutions, which are expected to undertake extensive measures to combat the misuse of financial systems by persons laundering drug money (Financial Action Task Force, Citation2016).

Finally, the FATF has worked closely with the World Bank to the effect of integrating its anti-money laundering standards with financial inclusion practices by encouraging members to adopt a risk-based approach to customer due diligence (Financial Action Task Force, Citation2014; World Bank, Citation2020b). Acknowledging that the US Patriot Act, regional anti-money laundering standards and international financial inclusion practices are closely interlinked (Alexander, Citation2002), the analysis explores the relevance of their interactions with Uruguay’s cannabis legislation as separate, yet interdependent strands, and the implications of such tensions for Uruguay’s cannabis policy space.

US patriot act

Although cannabis is currently legal in some US states, it remains illegal under US federal drug laws. This legislative divide has created significant uncertainties that, in turn, have discouraged most federally regulated banks from servicing the accounts of the US cannabis industry due to alleged concerns of violating US federal money laundering statutes (Conti-Brown, Citation2018). Given their limited options, several cannabis-related companies and retailers have resorted to operating solely on cash transactions (Hill, Citation2015), exposing them to substantial financial and safety risks (e.g. theft) that other established industries do not face. The constraints to Uruguay’s policy space by the US Patriot Act were unexpected, however:

The problem with the banks is the 2001 Patriot Act, which makes it so that you must ensure that the funds do not come from clandestine gambling, human trafficking, arms trafficking, drug trafficking. However, we never thought that this would be considered drug trafficking. (drug regulator)

The US Federal Reserve has certain norms with respect to banks … So, those banks that have branches in the United States must comply with those norms and therefore, its parent company indicated to its subsidiaries, in this case those in Uruguay, that according to Federal Reserve regulations, they could not operate with those clients that were related to cannabis. (agriculture policymaker)

According to Section 319 of the US Patriot Act, financial institutions subject to forfeiture of funds include foreign financial institutions that hold a US interbank account with a covered financial institution, an agreement where a larger correspondent bank processes payments on a smaller bank’s behalf (Alexander, Citation2002). The relevance of Section 319 is that funds deposited into foreign banks with a US interbank account are interpreted, under US federal law, as having been deposited in the United States and, therefore, subject to US federal criminal and civil forfeiture rules. This mechanism grants US authorities the power to seise assets indirectly from foreign banks with a US interbank account by seising the funds directly from US correspondent banks.

Although foreign banks could opt-out of the US’ regulatory controls and service the accounts of cannabis businesses in accordance with Uruguay’s financial laws, this would require they terminate their correspondent banking relationships with US financial institutions (Alexander, Citation2002). This alternative is difficult, however, as terminating a US interbank account is similar to dissolving commercial relations with the United States (Preston, Citation2002) and would prevent these banks from processing international transactions for their clients abroad. The relevance of the US Patriot Act’s extraterritorial scope is also demonstrated partially by the requirement that foreign banks have access to a US interbank account to participate in the foreign exchange market (Alexander, Citation2002). Evidently, Section 319 presents foreign banks operating in Uruguay with very limited options: either ensure their clients’ funds are not derived from cannabis sales, risk asset forfeiture or sever financial ties with US banks (Preston, Citation2002).

While Uruguay has its own state-operated banks, links between Uruguayan and US banks indicate that the US Patriot Act has relevance to financial transactions in Uruguay:

The respondent banks here including the Bank of the Republic, which is a state-owned bank and the main bank of the country – due to commercial relations with parent companies in the United States, they also saw the need to warn their clients that they could not have operable accounts with this product. (agriculture policymaker)

Uruguay works in US dollars, which means that the economy is quite dollarized. Besides all countries in the region work in dollars. When Uruguay uses dollars, we buy it from the US through the correspondent banks. Several banks. At the same time, these international transactions, as a country we also use the North American banking system and the dollar. So, Uruguay cannot escape this. Because we are a dependent country in this regard, like most in the region. (government official)

Regional anti-money laundering standards

The US Patriot Act is not alone in imposing constraints on Uruguay’s policy space, as regional anti-money laundering standards also exert powerful influence. Although the FATF’s Forty Recommendations are non-binding and the FATF does not possess legal authority to enforce their compliance (Hülsse, Citation2008), previous literature suggests that ‘many states consider them to be de facto binding if they are to remain in good standing before the organization’ (Shaffer, Citation2013). This de facto pressure might seem even more relevant to LMICs, given the apparent power imbalance of the FATF’s membership. While several high-income countries with major financial centres are full members of the FATF, associate members, including Uruguay, represent most LMICs, which are economically dependent on full member states (Helleiner, Citation1999). This hierarchical relationship implies that associate members may ‘comply [with FATF standards] even in the absence of explicit threats’ (Hülsse, Citation2008), as non-compliance may have wider repercussions for other policy areas or relations.

The threat of FATF sanctions or being placed on its ‘Non-cooperative Countries and Territories’ (NCCT) ‘blacklist’ (Financial Action Task Force of Latin America, Citation2019) was identified by one interviewee as having influenced Uruguay to pursue policies consistent with its AML commitments. The FATF’s ‘blacklist’ is a list of countries that the organisation perceives as facilitating money laundering activities (Sharman, Citation2008), as described by one drug regulator in Uruguay: ‘We promoted an AML law because, in 2005, Uruguay was designated as a country that laundered money. It was about to be blacklisted’. Though formally abandoned in 2006, this reference to the NCCT ‘blacklist’ highlights the extent of the FATF’s leverage, since it allows financial institutions that invest in dependent economies like Uruguay to impose economic sanctions or restrictions on states that fail to comply with its international standards (Mugarura, Citation2016).

Interviewees pointed towards policies focused on cannabis producers and retailers, and on broader financial systems, as evidence that Uruguay has sought to respond to the risk that a legal cannabis market might create opportunities for money laundering. Some policymakers interviewed indicated that they specifically designed cannabis legislation so that banks could provide financial services to cannabis producers and retailers consistent with their AML obligations:

No one anticipated the issue that we were going to have with the banks. Because in the legislation and particularly in the regulation, with much pleasure we established clear limitations so that the companies could apply for a license. Importantly, with the view that this was not going to launder drug money, with a legal structure linked to another legal structure. (drug regulator)

One participant situated the relevance of Uruguay’s AML commitments within a wider business perspective. The ability to license enough cannabis producers to meet public demand is presented as a product of whether the private firms perceived the financial benefits of producing cannabis in Uruguay exceeded the time and cost expenses (including lost business) of applying for a production license. Remarking on the actions of cannabis companies, one interviewee felt the excessive financial costs of applying for a production license influenced the more experienced producers to abandon the process entirely:

It was a paradox. Because the proposals that had more ‘know-how’, they came from outside the country. They came from other countries like Canada and the USA, from California, Israel. However, to present all that documentation, get it notarised, translated and sent here. That’s why we even extended the deadline to present proposals [for the international companies]. However, for the companies, it was an expense issue, and some did not finish the process. (drug regulator)

International financial inclusion practices

Available data do not suggest a direct contradiction between cannabis regulation and financial inclusion practices. However, it was cannabis’s status as an internationally controlled substance that created challenges for Uruguay to promote financial inclusion of cannabis producers and retailers:

Cannabis falls within the characteristics of psychoactive substances of the World Health Organization that are not legally traded between countries. That led to difficulties sometimes, even for the producers because they couldn’t have money in their banks. (health policymaker)

It started with the private banks. Private banks have a right to open or close accounts. One bank told a pharmacy owner that you cannot sell cannabis because Santander Bank has its affiliates in Spain, right? In the US, all that money in circulation, there will come a time when they are going to cut you off. Because with all that international money in circulation, I am contaminating it with a pharmacy that sells cannabis in Uruguay. (civil society)

Several interviewees strongly felt that the power of correspondent banks to exert this type of influence over their Uruguayan counterparts came down to Uruguay being ‘a very small country’, suggesting that the ‘international financial system, the correspondents, did not want to take on the risks. And much less will they take on the risks for a small market like Uruguay’. However, it is also evident that cannabis legalisation has not been sufficiently reconciled with Uruguay’s international commitments to financial inclusion. For instance, some participants from Uruguay’s business community identified certain counterproductive policy interventions with respect to commercial sales through pharmacies. As one pharmacy owner highlighted, Uruguay’s cannabis regulation was coexisting with the state’s commitment to financial inclusion, with limited consideration of cannabis’s illegal status at the international level:

I am going to where the Uruguayan government, let’s say contradicted itself. They push forward the cannabis sales law, of recreational cannabis through pharmacies. International law does not permit banks to receive money from the sale of cannabis, although it is legal. Then, on the other hand, you ask for financial inclusion in the country. You ask for it, you demand it. It is a law; if you don’t [digitalise your services], you receive a fine. On the other hand, you sell something that cannot be deposited into banks. (commercial actor)

Discussion and conclusions

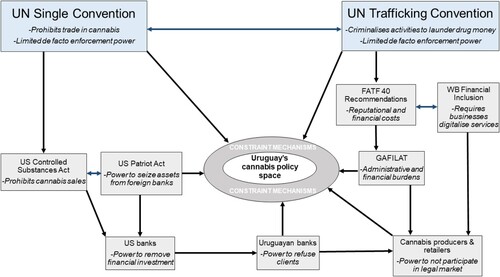

Contrary to expectations and wider literature, Uruguay’s drug treaty obligations constrained policy space less than the norms and practices of international finance, at least partly because they lack clear enforcement mechanisms. This does not imply that the UN drug conventions were insignificant, however. As shows, their significance was more indirect via their integration into the norms and practices of international financial institutions responsible for preventing the misuse of financial systems by organisations laundering drug money.

Figure 2. International policies and processes relevant to Uruguay’s cannabis policy space3.

Each box represents a different international policy or process with key characteristics in italics that factor into their influence on cannabis policy space. Black arrows represent their ability to influence cannabis policy space. Double ended blue arrows represent high levels of integration and areas where international policies and processes mutually reinforce each other. Note drug and finance policies of other countries can be as important as the US Patriot Act, but this diagram displays the most relevant external pressures to Uruguay’s cannabis policy space mentioned in the interviews.

From a health policy perspective, the significance of this case lies in the potential for international finance norms enforced beyond officially sanctioned channels to constrain implementation of national health policy innovation. This is apparent in the unanticipated constraints to Uruguay’s policy space to implement aspects of cannabis supply that interact with broader financial systems, and arguably more importantly, the US interbank payment system. Elements of cannabis regulation involving business transactions denominated in US dollars were more likely to face considerable challenges in implementation compared to other policy options, e.g. cannabis clubs or home cultivation. This situation may have been intensified by Uruguay’s highly dollarized economy, resulting in a dependence on bilateral relationships between Uruguayan banks and US financial institutions, which restricted how Uruguayan banks could work with cannabis producers and retailers. In this context, it is not surprising that banks in Uruguay and from leading financial markets were reluctant to provide financial services to the emergent cannabis industry, as this could interfere with their relationships with US financial institutions and place them at risk of losing access to the US interbank payment system.

This case is notable for the unexpected impacts on policy space arising from tensions between cannabis regulation and the US Patriot Act. From an international politics and governance perspective, this type of interaction might be presumed to be the least problematic since Uruguay is not legally obligated to comply with the US Patriot Act, unlike its obligations under the UN drug conventions. However, the extraterritorial scope of the US Patriot Act has served somewhat as a regional AML policy, effectively substituting the formal enforcement mechanisms of the 1988 Trafficking Convention. Consistent with previous analyses on the extraterritorial reach of US law (Alexander, Citation2002; Preston, Citation2002), the threat of economic sanctions by US banks to their Uruguayan counterparts appears to have served as a powerful signal to close the accounts of cannabis producers and retailers as perceived high risks for money laundering.

The extraterritorial impacts of national legislation in other jurisdictions are widely neglected in the political science and public health literatures, with theoretical and empirical insights focused primarily on national-supranational relations. However, as this analysis shows, the extraterritorial reach of national legislation in other jurisdictions can be as important to constraining domestic policy space as legally binding international agreements. Accordingly, health policymakers and advocates should be aware of the potential for informal enforcement of international finance norms to constrain development of national health policy innovation and the challenges that the US Patriot Act may pose for implementation of cannabis sales in other contexts.

These findings challenge aspects of how the significance of the UN drug conventions was anticipated and shaped parts of policy debates in Uruguay and in publications, positioning them as significant but in more complex ways than previously has been understood. While previous research has focused on issues of sovereignty and legal authority in relation to the UN drug conventions, this is the first study to thoroughly examine the significance of the wider governance of international crime and the informal mechanisms of constraint used by US and other foreign banks to limit Uruguay’s cannabis policy space. This analytical distinction is important as examining the complex policy dynamics of cannabis regulation reveals aspects of decision-making that are highly interconnected and, in practice, grant immense power to private-sector actors.

In contrast to accounts that emphasise the limited relevance of Uruguay’s obligations under the UN drug conventions (Conti-Brown, Citation2018; Musto, Citation2018; von Hoffmann, Citation2018; Walsh & Jelsma, Citation2019), here their impact appears to be highly significant, albeit indirectly, operating via intersections with the global financial system. Exclusive focus on issues of sovereignty and legal authority may deflect attention from the exercise of power and influence that occurs within a dynamic and fluid system consisting of various overlapping policies and processes. Here, informal enforcement of what otherwise are formally constituted financial regulations appears more significant to questions of policy space, allowing financial institutions to remove decision-making power on risk management away from Uruguayan regulators.

While this partly reflects high levels of interconnectedness of drug and finance agendas at diverse levels, the primacy of a narrowly constructed risk management principle in approaches to financial supply intensifies the constraints experienced by Uruguayan regulators. In particular, the FATF’s AML standards and the World Bank’s financial inclusion initiative typically exclude reference to the money laundering implications of potentially low-risk financial transactions, at least in the context of perceived risky business activities, including drugs, Internet gambling and tobacco sales (Hill, Citation2015). Alongside interview accounts that suggest its highly dollarized economy limited Uruguay’s options, the dominant expectation for banks to avoid risky business relationships restricts the ability of Uruguayan regulators to exercise national policy space over the availability of financial services.

The constraints to policy space described above are also likely to reduce scope for Uruguay to achieve its national health and public security objectives relative to cannabis regulation. Although international commitments to control money laundering are non-binding, non-compliance carries tangible risks of economic sanctions for banks that fail to comply with them, which likely will continue to restrict access to financial services for the emergent cannabis industry. This is significant to Uruguay’s health and public security objectives of cannabis regulation as providing users with legal access to a quality-controlled product was developed as a strategy both to protect health and combat the illicit drug market (Musto, Citation2018).

The practical challenges of achieving Uruguay’s health and public security objectives are illustrated via how international financial regulations require that banks undertake costly due diligence measures to assess the money laundering risks of any client linked to the sale of cannabis. While such stringent measures impose a significant fiduciary duty on Uruguayan banks looking to service cannabis producers and retailers, the paperwork associated with anti-money laundering requirements may also dissuade additional cannabis firms from applying for a production license. International finance norms may also reduce access to cannabis due to the financial risks that pharmacies face in selling a substance that cannot be legally traded between countries. Notably, the risk of losing access to financial services may discourage additional pharmacies in Uruguay from participating in the legal supply system. Moreover, if banks refuse to work with Uruguay’s emergent cannabis industry, this has the potential to increase the risk of money laundering, as cannabis companies may be forced to operate in the untraceable economy of cash.

Although finance norms have limited Uruguay’s ability to produce and sell cannabis through the formal financial system, there is scope for Uruguay to achieve its national health and public security objectives via cash-based sales, home cultivation or cannabis clubs. Nevertheless, as long as the market-based policies of cannabis regulation remain fundamentally in conflict with the risk management practices of international finance, reconciling tensions across Uruguay’s health, crime and finance priorities will likely prove challenging. While this study did not specifically examine the impacts of international financial controls on Uruguay’s national cannabis policy, future research could assess how such tensions might affect (both positively and negatively) the law’s health and public security outcomes, e.g. cannabis consumption and the size of the illicit market.

This study has a number of recognised limitations, including those inherent to single case studies (Yin, Citation2018). While the findings suggest that the UN drug conventions were indirectly significant to constraining implementation of Uruguay’s cannabis regulation, it is possible that there are some hidden aspects of this influence and relevance due to the types of actors and organisations recruited for a formal interview. In part, this reflects a decision to focus on interviews with domestic-level participants given the relative dearth of research examining Uruguay’s cannabis policy process through the lens of local perspectives (for notable exceptions, see: Musto (Citation2018) and von Hoffmann (Citation2018)). Focus on complex policy dynamics across diverse governance levels may also risk neglecting the significance of horizontal coordination challenges within Uruguay. However, this emphasis reflects evidence provided by interviewees, highlights important aspects of decision-making power and influence in Uruguay and contributes to the public health literature on policy space that has focused primarily on national-supranational relations.

Concerns about the impact of finance norms on national policy space are not limited to Uruguay or even cannabis regulation but also economic (Alexander, Citation2002; Mayer, Citation2009; Preston, Citation2002) and health governance (Koivusalo, Citation2014; Thow & McGrady, Citation2014), among other sectors. Nevertheless, the ongoing challenges of developing Uruguay’s cannabis market suggest the need to advance understanding of the relationships between implementation of cannabis sales, anti-money laundering standards and financial inclusion practices. Indeed, previous US-based research shows that finance norms have also created challenges for developing state-level cannabis supply systems (Conti-Brown, Citation2018; Hill, Citation2015).

The wider significance to drug policy of examining such interactions with key global, regional and national financial governance mechanisms can be further illustrated by Canadian banks allegedly refusing to service cannabis-related businesses in Canada (Crabb, Citation2019), actions that have been apparently contested with reference to international finance norms. Potential challenges to Jamaica’s exportation of medical cannabis (Bewley-Taylor et al., Citation2020) also serve to highlight the significance of understanding such complex interactions between the normative practices of international finance across jurisdictions. This study highlights the governance challenges of reconciling tensions between the market-based policies of cannabis regulation and a narrowly constructed risk management principle in approaches to financial supply, where the reputational and financial costs of providing financial services to cannabis producers and retailers have generally discouraged banks from investing in this emergent industry.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks representatives of the Uruguayan Research Centre for the Tobacco Epidemic (CIET) and the Ministry of Health for their support during engagement of key interviewees. Professors Jeff Collin and Sarah Hill are thanked for their critical review of an early draft of this manuscript. Finally, I would like to thank the Reviewers for taking the time and effort required to review this manuscript. I sincerely appreciate their valuable comments and suggestions, which helped improve the overall quality of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, K. (2002). Extraterritorial US banking regulation and international terrorism: The Patriot Act and the international response. Journal of Banking Regulation, 3(4), 307–326. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1057palgrave.jbr.2340122.pdf.

- Arnold, A., & Salisbury, D. (2019). Going it alone: The causes and consequences of U.S. extraterritorial counterproliferation enforcement. Contemporary Security Policy, 40(4), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1595882

- Baudean, M. (2021). Five years of cannabis regulation: What can we learn from the Uruguayan experience? In D. Corva, & J. S. Meisel (Eds.), The routledge handbook of post-prohibition cannabis research (pp. 63–80). Routledge Handbooks.

- Bewley-Taylor, D., Jelsma, M., & Kay, S.. (2020). Cannabis regulation and development: Fair (er) trade options for emerging legal markets. International Development Policy, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.3758

- Bucacos, E., Graña, A., Licandro, G., & Mello, M. (2019). Intervention in Uruguay and its effects, 2005 to 2017. In A. Werner, M. Chamon, D. Hofman, & N. Magud (Eds.), Foreign exchange interventions in inflation targeters in Latin America (pp. 249–284). International Monetary Fund.

- Catão, L. A. V., & Terrones, M. E. (2016). Dollar Dependence. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/09/pdf/catao.pdf.

- Cerda, M., & Kilmer, B. (2017). Uruguay's middle-ground approach to cannabis legalization. International Journal of Drug Policy, 42, 118–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.007

- Conti-Brown, P. (2018). The policy barriers to marijuana banking. Penn Wharton Public Policy Initiative, 6(2), 1–9. https://repository.upenn.edu/pennwhartonppi/52.

- Controlled Substances Act, 21 U.S.C. 801 et seq. (1970). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title21/chapter13/subchapter1&edition=prelim.

- Crabb, J. (2019). Banks still scared of cannabis businesses. International Financial Law Review. https://www.iflr.com/article/2a638ls5pmz4hbpy1375s/banks-still-scared-of-cannabis-businesses.

- Eggenberger, K. (2018). When is blacklisting effective? Stigma, sanctions and legitimacy: the reputational and financial costs of being blacklisted. Review of International Political Economy, 25(4), 483–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2018.1469529

- Financial Action Task Force. (1990). Financial action task force on money laundering report. http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/1990%20ENG.pdf.

- Financial Action Task Force. (2014). Guidance for a risk-based approach: The banking sector. http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Risk-Based-Approach-Banking-Sector.pdf.

- Financial Action Task Force. (2016). Correspondent banking services FATF guidance, Issue. http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-correspondent-Banking-Services.pdf.

- Financial Action Task Force. (2019a). FATF Members and Observers. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/about/membersandobservers/.

- Financial Action Task Force. (2019b). International standards on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism and proliferation, adopted by the FATF plenary in February 2012 (FATF Recommendations Issue. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/pdfs/FATF%20Recommendations%202012.pdf.

- Financial Action Task Force of Latin America. (2019). Financial action task force of Latin America (GAFILAT). Retrieved 3 February from https://www.fatf-gafi.org/pages/gafilat.html.

- Financial Action Task Force of Latin America. (2020). Mutual evaluation report of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay. http://www.gafilat.org/index.php/es/biblioteca-virtual/miembros/uruguay-1/evaluaciones-mutuas-16/3726-mer-uruguay-jan-2020/file.

- Garton, K., Swinburn, B., & Thow, A. M. (2021). Who influences nutrition policy space using international trade and investment agreements? A global stakeholder analysis. Globalization and Health, 17(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00764-7

- Gaudán, A. (2017). International money laundering rules clash with Uruguay´s Legal Marijuana Shops. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/14561.

- Hawken, A., & Kulick, J. (2014). Treaties (probably) not an impediment to ‘legal’ cannabis in Washington and Colorado. Addiction, 109(3), 355–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12454

- Hawkins, B., & McCambridge, J. (2021). Alcohol policy, multi-level governance and corporate political strategy: The campaign for Scotland's minimum unit pricing in Edinburgh, London and Brussels. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 23(3), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120959040

- Helleiner, E. (1999). State power and the regulation of illicit activity in global finance. In F. RH, & A. P (Eds.), The illicit global economy and state power (pp. 53–90). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2004). Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics, 2(4), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472

- Hill, J. (2015). Banks, marijuana, and federalism. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 65(3), 597–647. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol65/iss3/7.

- Hülsse, R. (2008). Even clubs can’t do without legitimacy: Why the anti-money laundering blacklist was suspended. Regulation & Governance, 2(4), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2008.00046.x

- Institute for the Regulation and Control of Cannabis. (2023). Inicio. Retrieved 16 May 2023, from https://ircca.gub.uy/.

- International Narcotics Control Board. (2013). INCB is concerned about draft cannabis legislation in Uruguay. https://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/PressRelease/PR2013/press_release_191113e.pdf.

- Itaú. (2020). Correspondent Banks. Retrieved 8 March 2023, from https://ir.itau.cl/English/our-company/correspondent-banks/default.aspx.

- Jackson, R. (2021). The purpose of policy space for developing and developed countries in a changing global economic system. Research in Globalization, 3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100039

- Junta Nacional de Drogas. (2016). Estrategia Nacional para el abordaje del problema drogas. Período 2016-2020. https://www.gub.uy/junta-nacional-drogas/comunicacion/publicaciones/estrategia-nacional-para-abordaje-del-problema-drogas-periodo-2016-2020.

- Koivusalo, M. (2014). Policy space for health and trade and investment agreements. Health Promotion International, 29(Suppl 1), ii29–ii47. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau033

- Koivusalo, M., Schrecker, T., & Labonté, R. (2009). Globalization and policy space for health and social determinants of health. In R. Labonté, T. Schrecker, C. Packer, & V. Runnels (Eds.), Globalization and Health (pp. 127–152). Routledge.

- Londoño, E. (2017, August 25). Pot was flying off the shelves in Uruguay. Then U.S. Banks Weighed In. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/25/world/americas/uruguay-marijuana-us-banks.html.

- Mander, B. (2020, 6 June). Uruguay cannabis producer sets sights on global dominance. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/ad308e8b-935c-4153-842e-8156b76c5786.

- Mayer, J. (2009). Policy space: What, for what, and where? Development Policy Review, 27(4), 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2009.00452.x

- Ministerio de Salud Pública. (2020). Cometidos. Retrieved 4 May from https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/institucional/cometidos.

- Mugarura, N. (2016). The global anti-money laundering regulatory landscape in less developed countries. Routledge.

- Musto, C. (2018). Regulating cannabis markets. The construction of an innovative drug policy in Uruguay [Doctoral dissertation, University of Kent, Utrect University]. University of Kent Theses and Dissertations Archive. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/68477/.

- Office of the President of Uruguay. (2023). Uruguay Presidencia. Retrieved 16 May 2023, from https://www.gub.uy/presidencia/.

- Preston, E. (2002). The USA Patriot Act: New adventures in American extraterritoriality. Journal of Financial Crime, 10(2), 104–116. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.110813590790310808664/full/html.

- Queirolo, R. (2020). Uruguay: The first country to legalize cannabis. In T. Decorte, S. Lenton, & C. Wilkins (Eds.), Legalizing cannabis: Experiences, lessons and scenarios (pp. 116–130). Routledge.

- Santander Group. (2013, October 17). Santander launches its retail banking brand in the U.S. 8 March 2023. https://www.santander.com/content/dam/santander-com/en/documentos/historico-notas-de-prensa/2013/10/NP-2013-10-17-Santander%20launches%20its%20retail%20banking%20brand%20in%20the%20U.S.%20-en.pdf.

- Scotiabank. (2020). Our global presence. Retrieved 21 March 2023, from https://www.gbm.scotiabank.com/en/about-overview/our-global-presence.html.

- SENACLAFT. (2018). Information to present for the issuance of financial inspection report to the National Secretariat for the fight against money laundering and financing of terrorism (SENACLAFT). https://www.ircca.gub.uy/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Instructivo-Senaclaft-v2.pdf.

- Shaffer, G. C. (2013). Transnational legal ordering and state change. In G. C. Shaffer (Ed.), Transnational legal ordering and state change (pp. 18–20). Cambridge University Press.

- Sharman, J. C. (2008). Power and discourse in policy diffusion: Anti-money laundering in developing states. International Studies Quarterly, 52(3), 635–656. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29734254.

- Tatenhove, J. v., Mak, J., & Liefferin, D. (2006). The inter-play between formal and informal practices. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 7(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705850600839470

- teleSur. (2018, August 22). Uruguay government defends legal cannabis as global bankers bust distributors. teleSur. https://www.mintpressnews.com/uruguay-government-defends-legal-cannabis-global-bankers-bust-distributors/231186/.

- The USA Patriot Act of 2001, Pub. L. No 107-156, 115 Stat. 272. (2001). https://www.congress.gov/107/plaws/publ56/PLAW-107publ56.pdf.

- Thow, A. M., & McGrady, B. (2014). Protecting policy space for public health nutrition in an era of international investment agreements. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92(2), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.120543

- United Nations. (1961). Single convention on narcotic drugs, 1961, As amended by the 1972 Protocol amending the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21517en/s21517en.pdf.

- United Nations. (1971). Commentary on the convention on psychotropic substances. https://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CND/Int_Drug_Control_Conventions/Commentaries-OfficialRecords/1971Convention/1971_COMMENTARY_en.pdf.

- United Nations. (1972). Commentary on the protocol amending the single convention on narcotic drugs, 1961. https://www.unodc.org/documents/treaties/organized_crime/Drug%20Convention/Commentary_on_the_protocol_1961.pdf.

- United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. (1988). United Nations convention against illicit traffic in narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances. http://www.incb.org/e/conv/1988/articles.htm.

- von Hoffmann, J. (2018). Breaking ranks: Pioneering drug policy protagonism in Uruguay and Bolivia. In A. Klein, & B. Stothard (Eds.), Collapse of the global order on drugs: From UNGASS 2016 to review 2019 (pp. 191–216). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Walsh, J., & Jelsma, M. (2019). Regulating drugs: Resolving conflicts with the UN drug control treaty system. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 1(3), 266–271. https://doi.org/10.31389/jied.23

- Walsh, J., & Ramsey, G. (2018). Uruguay’s Drug Policy: Major Innovations, Major Challenges. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Walsh-Uruguay-final.pdf.

- World Bank. (2020a). Financial Inclusion. 3 February 2023, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview.

- World Bank. (2020b). Financial Integrity. 20 March 2023, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialmarketintegrity.

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications. Sage.