?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Nigeria carries a high burden of HIV infections, with Taraba State having a prevalence of 2.49%. This quasi-experimental study evaluated the impact of the Lafiyan Yara project, which utilised various community-based mobilisation models, on the enhancement of HTS uptake among women during pregnancy, and children. The intervention involved the implementation of mobilisation by Traditional Birth Attendants (TBA), Village Health Workers (VHW), Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs), and a combination of the three in four study local government areas (LGA) in Taraba State. Baseline and end-line surveys were conducted focused on women aged 15–49 years who delivered a child in the past 1 year, and children in their households, in the study and a control LGA. A difference-in-difference (DID) approach was applied by using a probit regression model with interaction terms for treatment status (intervention vs. control) and survey timing to compute the DID estimates of uptake of HTS. The TBA model showed the highest impact in the referral of women to HTS, while the combined model demonstrated the greatest impact in referrals for children. Scaling up and strengthening these community mobilisation efforts can improve access to HIV testing and contribute to HIV/AIDS prevention and control in the region.

Introduction

One crucial element needed for the success of the ambitious 95-95-95 three-pronged strategy of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) is increased access to HIV testing services (HTS) (Heath et al., Citation2021; Kumar et al., Citation2015; Scanlon & Vreeman, Citation2013). This is especially in countries where widespread inequalities and barriers exist (Heath et al., Citation2021), as ten million people still do not have access to ART, and about 48% of children living with HIV are unable to access life-saving treatment (UNAIDS, Citation2022). HIV counselling and testing, also known as HIV voluntary counselling and testing, was introduced in 1994 by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNAIDS as both a primary and secondary preventive strategy to address the separate aspects of health promotion and early diagnosis and treatment of the disease (Xu et al., Citation2020). This approach has proven effective in reducing anxiety about the disease and lowering risky behaviours (Xu et al., Citation2020). However, in countries with problems of access, such important gains are often missing or lacking. One major approach that has shown promise in addressing this, is the utilisation of community structures to improve access and utilisation of such services.

From a sociological point of view, a community structure is the organisation of social groups and networks within a community (University of Minnesota, Citation2016). This includes interpersonal networks, community organisations, infrastructure, employment, housing, and options for leisure activity. Numerous interventions have shown that existing community structures can be used to improve health services utilisation (UNAIDS, Citation2020). An example is the community-directed treatment with Ivermectin (CDTI) intervention to control onchocerciasis which made use of lay community members as health workers to distribute drugs to community members (Homeida et al., Citation2002). Also, community-based health workers have been used in the delivery of various other health interventions including for malaria and diarrheal disease control using integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) (Marsh et al., Citation2014), as well as for maternal health services (Grant et al., Citation2017). Successes recorded in these applications have prompted further implementation research into how existing community structures can be used to deliver numerous health services within communities (Singh et al., Citation2017). Such a possibility includes lay members of communities and structures already existing within communities being used to enhance HIV care within the communities.

Nigeria currently has the second largest burden of HIV infections in the world, with an estimated 1.9 million people living with HIV in 2018 (NACA, Citation2019). Taraba state, in the Northeastern part of the country, has an HIV prevalence of 2.49% (the highest in the Northeast geopolitical zone), and the fourth highest in the country after Akwa-Ibom, Benue, and Rivers States (NACA, Citation2019). Drivers of the HIV epidemic include norms that promote multiple concurrent sexual partnerships, low-risk perceptions, low awareness of HIV, and poor literacy rates (NACA, Citation2019). Likewise, there is low awareness of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (Adeleke et al., Citation2009). Like many northern states in Nigeria, the demand for women health services is very low in Taraba and the maternal indicators are among the poorest in the world (Sinai et al., Citation2017). In addition, a common maternal behaviour pattern in northern Nigeria is that women are more likely to visit traditional birth attendants (TBA) than orthodox health facilities for antenatal and postnatal care which hinders HTS access (Doctor et al., Citation2012). Since HTS services are provided at orthodox health facilities, preference for traditional birth attendants preclude early identification and treatment of positive infants. Gaps therefore exist in early infant diagnosis (EID) at the facility level because women do not visit health facilities for ANC. It is known that the benefit of surviving from early use of ART is lost when infant diagnosis of HIV is not picked up early (Mphatswe et al., Citation2007; Wamalwa et al., Citation2012). While polymerase chain reaction has made infant HIV diagnosis easier and more reliable, the generation of early infant diagnosis (EID) results is often delayed due to limited accessibility to the services and the need to process a substantial number of samples (Spooner et al., Citation2019). Also, there are limited donor funded HIV interventions happening in Taraba leaving a gap in the continuum of care for HIV (personal communication). The last intensive intervention for HIV was the Sure-P funds for scaling up the treatment of HIV/AIDS which ended in 2017 (Itiola & Agu, Citation2018). There is consequently a large number of undiagnosed people living with HIV (PLHIV) including children and pregnant women.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of a community-based referral for HIV testing services from mobilisation by existing community structures including patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMV), traditional birth attendants (TBA), and village health workers (VHW). This research was carried out as part of the broad objectives of the Lafiyan Yara Project, a context-specific community participatory intervention which had the overall aim of creating greater demand for HIV testing services (HTS), anti-retroviral treatment (ART) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services. The intervention was aimed at the rapid identification and linkages of children less than 15 years of age living with HIV in eight LGAs in Taraba State, Nigeria, to underutilised HIV testing services (HTS) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services in State government-owned facilities. The intervention strategy leveraged on the acceptance of community and informal health structures to bridge the gap between households and health facilities for HTS.

Theory of change

The Lafiyan Yara theory of change is grounded on the premise that early detection for HIV has the propensity to reduce infant, child and maternal mortality. To facilitate early detection of HIV, we noted that increased access to antenatal care (ANC) services by pregnant women and quality delivery services by health workers would enhance exposure to HTS and PMTCT services which would consequently eliminate new infections in babies. Similarly, improved linkages between informal and formal health structures in Taraba state will amplify finding of new HIV positive cases, increase anti-retroviral uptake, increase the number of virally suppressed women and children living positively invariably reducing mortality among target groups.

A second outcome anticipates better health seeking behaviours among direct and indirect beneficiaries when people are informed, motivated, equipped and have opportunities to voluntarily seek HTS as a result of recognised benefits such as decreased mortality. While it is understood that the changes in behavioural practices rarely occur through linear mechanisms but are influenced by a range of other factors such as education, knowledge and wealth status, the programme anticipates that contact between programme beneficiaries and health worker can lead to an increase in knowledge and motivation to adopt positive behaviours. When reinforced by influencers within the community or the home, beneficiaries become increasingly motivated to adopt what they now see as socially acceptable HIV prevention and treatment practices.

Method

Study design

This study employed a difference-in-difference (DID) design as its primary methodological approach, aimed at evaluating the impact of the community-based referral system for HIV testing services during pregnancy among women who had completed term pregnancy within the preceding year, and children below the age of 15 residing in their households. The DID design is a quasi-experimental method that estimates causal effects by comparing the difference in outcomes before and after treatment (or intervention) between a group that receives the treatment and a control group that does not (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2008). This approach has the advantage of addressing some of the limitations of traditional pre–post comparisons, such as selection bias and time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity, making it well-suited for evaluating the impact of interventions in real-world settings. In the context of this study, it involved comparing the differences in outcomes for individuals exposed to the community-based referral intervention before and after its implementation with those who were not exposed to it.

Study location

The Lafiyan Yara project was carried out in eight selected Local Government Areas (LGA) across the three senatorial districts in the Taraba State, Nigeria, namely: Taraba North senatorial district (Jalingo, Zing & Karim Lamido LGA); Taraba South senatorial district (Wukari LGA); and Taraba Central senatorial districts (Gassol, Bali, Gashaka & Sardauna LGA) from 2019 to 2022. To demonstrate proof of concept for standalone community mobilisation models, the intervention was concentrated in three specific LGAs while the other five LGAs employed a combined approach using all three mobilisation methods. The three LGAs with standalone model, plus one additional LGA with the combined approach, were part of this quasi-experimental study reported here. This strategic choice enabled a detailed assessment and comparison of the different models. In Lau LGA, serving as the control, no intervention model is implemented, facilitating a comparison of outcomes with the intervention LGAs. The control LGA represented the prevailing state of routine HIV testing services in the study location, characterised by the absence of a deliberate and intentional community-based referral system for accessing the available HIV testing services in healthcare facilities. The choice of study LGAs took into account their equitable geographical distribution across the state, and was independent of population size or HIV prevalence rates.

The intervention

Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) model was implemented in Bali, Village Health Workers (VHWs) model in Gashaka LGA, Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs) model in Zing LGA, and in Jalingo LGA a combination of all the three models was implemented. TBAs are women living within communities, who have no formal health training but provide midwifery services to pregnant women. VHWs are individuals living within communities, usually having up to secondary level education but no formal health training, who volunteer, and are trained to provide specified community health services to members of their communities. PPMVs are persons registered with appropriate government agency to sell off-the-counter drugs and medications within their communities. The implementation of the Lafiyan Yara Project was carried out by the Society for Family, Nigeria, who recruited, trained and deployed the different groups of community mobilisers. The mobilisers were required to intentionally find pregnant women, educate them about HTS, and refer them to public health facilities within their catchment area to receive HIV test. In each public health facilities in intervention areas, a facility focal person who was identified to whom beneficiaries are referred. In addition, community volunteers, who are members of staff from community-based organisations in the intervention communities, were enlisted to collect and compile all the referred and tested data from various facilities into a monthly summary report for the routine monitoring and evaluation of the intervention. The TBAs and VHW were given in incentive package of NGN 12,000 which was changed to NGN 30,000 in keeping with the national minimum wage. The PPMV were not given this incentive because this group typically operated from their commercial drug shops and were not required to conduct house-to-house visit. However, all the types of community mobilisers were given a tracking incentive of NGN 100 for every completed referral (i.e. when referred person goes to the health facility for HTS). The community volunteers were also given a stipend to cover their costs.

Study population

In line with the DID design, we conducted baseline and end-line household surveys in this study. We included only women, aged 15–49 years, who had delivered of a child in the 12 months preceding each survey regardless of the current status of the child. We excluded eligible women who had not lived in the study communities for at least 1 year preceding each survey. Our intervention exclusively targeted pregnant women and children in their households for HIV testing services. Consequently, inclusion criteria for both the baseline and end-line survey participants required completed pregnancies within the past year to ensure comparability. However, interviewing the same women in the two surveys was not feasible due to the typical 9-month duration of pregnancies. To maintain consistency, we selected participants from the same areas using uniform sampling techniques. While assessing the same individuals would have directly measured individual-level changes, practical constraints prevented this approach.

Sample size determination

To detect a programmatically significant increase in uptake of HTS by at least nine percentage points, sample size calculation for this study was based on 80% power, assuming a type I error of 5%, adjusting for potential clustering using a design effect of 1.2, and a non-response rate of 10% among respondents. The NARHS 2012 survey estimated that the proportion of women in reproductive age group who have ever done an HIV test in Northeast geopolitical zone was 17.6%, consequently a sample size of 430 households was determined for each study LGA to be interviewed at each round of household survey. An eligible household was one that had a woman who completed term pregnancy in the past 12 months regardless of the current status of the child.

Sampling technique

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed. For each study LGA, the list of political wards and the estimated population was acquired and five of these were selected per LGA by simple random sampling. In each selected ward, ten communities were selected by simple random sampling. Starting from a randomly selected building in each selected community, an eligible household was interviewed in every alternate building till the proportionate sample size assigned to that community was exhausted. In selected buildings with more than one eligible respondent, the data collector selected who to interview by balloting. In each household, the woman selected responded to questions about the pregnancy she had in the past 1 year of the survey as well as on children <15 years old in her household.

Study instrument

The instrument for household surveys was an interviewer-administered questionnaire that included questions on background characteristics of respondents, exposure to community-based referral for HTS, and uptake of HIV testing services. Each study participant answered questions regarding their exposure to and utilisation of HTS services, as well as the exposure and utilisation of HTS services by children under 15 years living in their households.

Pre-test

The instrument for the household survey was pre-tested at a location within Jalingo LGA that was not included in the data collection at all the rounds of the survey. The results of the pre-test were utilised to refine the tools and make necessary adjustments to accommodate the specific characteristics and needs of the target population while maintaining contextual relevance. The same set of tools that were used during the baseline were employed for the end-line survey.

Method of data collection

Data collection was with the aid of computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) device by appropriately trained data collectors. The baseline data collection took place in October 2019, coinciding with the commencement of the intervention. The end-line survey was conducted in October 2021, although the formal conclusion of the intervention was in March 2022.

Measurement of outcome variables

The primary survey question of interest in this study was, ‘During your last pregnancy, did anyone in your community provide counselling or refer you to a health facility for HIV screening? (Yes/No)’. A similar question was posed for each child >15 years old in the household of the respondent. Subsequent questions aimed to identify the responsible person, including options like a Patent Medicine Vendor, Traditional Birth Attendant, Village Health Worker, Facility-based Health Worker, Religious Leader, or Others. We created individual variables for each type of community mobiliser of interest (1 if mobilised by that type of mobiliser of interest, and 0 if not). As the community mobilisers under investigation in this study are integral components of the community structures even without the intervention, our expectation was that there would be heightened referrals by the different types of community mobilisers in the intervention LGA compared to the control LGA.

Data analysis

To assess the association between referral for HIV Testing Services (HTS) and the independent variables (intervention model and survey timing), we employed a probit regression model incorporating interaction terms for treatment status and survey timing to compute the difference-in-differences estimates, while also estimating robust standard errors. The regression model is as follows:

yit represents the exposure to community mobilisation for each woman during pregnancy for treatment and control group (unit i) at time t (baseline and end-line surveys).

Treatmenti is a binary variable that equals 1 if unit i is in the intervention LGA and 0 if it’s in the control LGA.

Postt is a binary variable that equals 1 for time periods at end-line line and 0 for time periods at baseline.

β0 is the intercept, representing the expected value of the outcome variable in the control LGA before the intervention.

β1 represents the average treatment effect (ATE), which quantifies the impact of the treatment on the outcome.

β2 represents the average time effect, capturing any secular trends or changes in the outcome over time unrelated to the treatment.

β3 represents the difference-in-differences (DID) estimator, which measures the differential effect of the treatment over time for the treatment group compared to the control group.

ϵit represents the error term, accounting for unobserved factors and random variation.

In addition, similar regression analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between exposure to referral for HIV Testing Services and the independent variables, controlling for the background characteristics of the participants. To assess the performance of these regression models, likelihood ratio test was conducted. However, the results indicated that the inclusion of additional control variables did not consistently improve the models’ performance. Therefore, for the purpose of this analysis, we opted not to report the models with the additional control variables. We note that the DID for children referred for HTS by PPMV in Zing LGA and TBA in Bali LGA could not be estimated due to non-convergence of the models. This issue may be attributed to the limited sample size of children referred for HTS by these models in both the intervention and control LGAs.

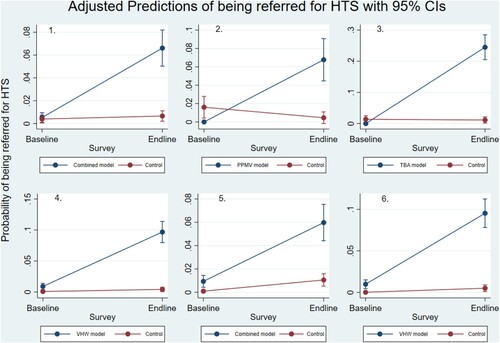

Additionally, adjusted predictions were estimated to examine the interaction between the timing of survey (baseline vs. end-line) and community mobilisation models (intervention vs. control) on the probability of being referred for HTS among women and children. These adjusted predictions provided insights into the effects of different community mobilisation models on the exposure to referral for HTS, considering the baseline and end-line time points. The ‘margins’ syntax in Stata 16 was used to generate the adjusted prediction as margins estimates.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Institute of Public Health (IPH) Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC No: IPHOAU/12/1384). Also, permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Taraba State Ministry of Health. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the study has been properly explained to them. Participants who were unable to write or sign after consenting to participate in the study were requested to thumb-print on the consent form. Also, verbal consent was obtained from community leaders in every community where the survey was conducted. Confidentiality was assured by ensuring that there are no personal identifiers on any data instrument, and only key research personnel have access to the data.

Results

presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants across different study Local Government Areas (LGAs), and study phases. The total number of women interviewed ranged from 430 to 458 in each of the five study LGAs at both baseline and end-line, while the children in their households aged <15 years old ranged from 953 to 1340. Most of the women fell into the 20–29 years age group, ranging from 36.7% at baseline to 60.7% at end-line across all the study LGAs. The highest proportion of the women had no formal education or only Quranic education at baseline and end-line, with percentages ranging from 27.5% at baseline to 48.6% at end-line, apart from in Jalingo LGA where there was a higher proportion of women that had completed formal education. The majority of children in the households of the women interviewed were under 5 years old, ranging from 54.5% to 64.6%. The proportion of female children was slightly higher than male children across all study locations and phases. The socio-demographic characteristics showed little change between baseline and end-line evaluation among the study population in each LGA.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of the women and children.

The DID estimate (represented by the interaction term Intervention#End-line) revealed statistically significant increases in the likelihood of being referred for HTS during pregnancy in various contexts (). There was an increase in referrals by PPMVs (β = 4.83, p < 0.001) and by TBAs (β = 5.14, p < 0.001) in the intervention group compared to the control group, indicating a positive impact of the intervention. Similarly, referrals from combined model showed a significant increase (β = 1.72, p < 0.001), as did referrals by VHWs (β = 1.18, p < 0.001). Among the four models, the TBA model exhibited the largest difference-in-difference (DID) coefficient for women, and the least was by the VHW model.

Table 2. Difference-in-difference (DID) coefficients of the intervention models from probit regression for HTS referral of women and children.

In the case of children, the DID estimates demonstrated a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of HTS referrals from combined model in the intervention group compared to the control group (β = 0.88, p < 0.001), highlighting a positive intervention impact. However, for children, the DID estimate did not yield a statistically significant change in the likelihood of HTS referrals by VHWs in the intervention group compared to the control group.

presents adjusted predictions obtained from a difference-in-difference probit regression estimation following the model estimations presented in (Please refer to Supplementary Table S1 for the values of the predicted margins displayed in ). The combinations of timing of evaluation (baseline vs. end-line) and study location (control vs. intervention) are depicted. It is important to note that the coefficients of the probit regression are not easily interpretable, therefore, only the margins are reported here. The findings for the PPMV model revealed that the intervention group experienced an increase in margin from 0.02 (p < 0.001) at baseline to 0.07 (p < 0.001) at end-line, while the control group margin decreased from 0.02 (p = 0.008) to 0.00 (p = 0.156) [Table S1]. For the TBA model, the intervention group demonstrated significant improvement with a margin of 0.24 (p < 0.001) at end-line, whereas the control group margin remained at 0.01 (p = 0.025) with a baseline margin of 0.01 (p = 0.014). In the VHW model, the intervention group experienced an increase in margin from 0.02 (p = 0.002) at baseline to 0.11 (p < 0.001) at end-line, while the control group’s margin remained at 0.01 (p = 0.082). Regarding the combined interventions model for women referred for HTS, the intervention group witnessed a substantial increase in margin from 0.02 (p = 0.008) at baseline to 0.22 (p < 0.001) at end-line, while the control group margin remained at 0.02 (p = 0.001) with a baseline margin of 0.05 (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Adjusted predicted probability of being referred for HIV testing services (HTS) from difference-in-difference analysis using probit regression for women and children. (1) Mothers referred in the combined model, (2) mothers referred in the PPMV model, (3) mothers referred in the TBA model, (4) mothers referred in the VHW model, (5) children referred in the combined model, (6) children referred in the VHW model.

For children referred for HTS by VHW, the VHW group showed improvement with a margin of 0.10 (p < 0.001) at end-line, while the control group margin increased slightly to 0.01 (p = 0.025) from a baseline margin of 0.01 (p = 0.001). Lastly, for children referred for HTS by combined intervention, the intervention group experienced an increase in margin to 0.07 (p < 0.001) at end-line, while the control group margin reached 0.01 (p = 0.005) with a baseline margin of 0.01 (p = 0.014). These results suggest that the interventions had positive effects on increasing margins for women and children referred for HTS, indicating the potential effectiveness of these interventions in improving HTS referrals.

presents referral for HIV Testing Services (HTS) through various other persons as reported by study participants. The results show at both baseline and end-line, a large proportion of women reported that either they or the children in their households were referred for HTS by health facility-based health workers, husbands/fathers, or a relative. However, the referral for HTS through religious leader, friend/neighbour, self, and others was low at both baseline and end-line in the intervention and control LGAs.

Table 3. Referral of women and children for HIV testing services (HTS) through other community members.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study we assessed the community-based referral for HIV testing services from mobilisation by existing community structures including patent and proprietary medicine vendors (PPMV), traditional birth attendants (TBA), and village health workers (VHW). The study showed that the percentage of women and children aged 0–14 years referred for HIV testing increased at the end-line in all the intervention LGAs while there was a reduction in the control LGA. This finding is in support of similar research done by Sweat et al. (Citation2011) which showed that community-based voluntary counselling and testing strategies achieved a higher intake of clients than those in standard clinic-based VCT in Tanzania (37% vs 9%), Zimbabwe (51% vs 5%) and Thailand (69% vs 23%). Their study further showed that this increase was due to the ‘multi-component, comprehensive and integrated nature of the intervention’. The role of private and public sector providers in HIV testing services has been increasingly recognised as a major way of increasing PMTCT services (White et al., Citation2016). Further, community-level interventions often play greater roles in managing epidemics, especially in resource-poor areas in developing countries (Khumalo-Sakutukwa et al., Citation2008) and this was evident in our study. Poor training of health workers, weak referral linkages and poor community and private sector participation have been identified as some of the challenges facing HIV diagnosis in rural communities (Adebimpe, Citation2013). These challenges may have accounted for the difference seen between the intervention and control LGAs.

The results of this study indicate that the intervention had a significant positive impact on the likelihood of being referred for HIV Testing Services (HTS) during pregnancy for both women and children. Specifically, the results show that there was an increase in referrals by Patent and Proprietary Medicine Vendors (PPMVs) and Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) in the intervention group. This suggests that involving PPMVs and TBAs in HTS referral efforts can be effective in increasing access to HTS during pregnancy. These findings align with previous research that has highlighted the importance of involving informal community health workers providers in promoting healthcare services in resource-limited settings. Lewin et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated that community-based health workers can be instrumental in increasing HIV/AIDS awareness, prevention, and testing rates in resource-limited setting. Similarly, community-based health workers have mobilised communities for HIV testing campaigns and awareness-raising activities, leading to increased participation (Shrestha et al., Citation2017).

Furthermore, referrals from the combined model, which encompass a variety of community mobilisers, demonstrated a substantial increase in the intervention group. This finding underscores the effectiveness of a multifaceted approach involving diverse healthcare providers, aligning with the recommendations of integrated healthcare delivery models. Both WHO and national guidelines stress the importance of broadening HIV testing efforts by implementing a strategic combination of clinic-based and community-based services to enhance the identification of individuals with HIV infection (Ford et al., Citation2018). However, it’s worth noting that while referrals by Village Health Workers (VHWs) showed a significant increase in the intervention group but had the smallest difference-in-difference coefficient compared to other healthcare providers. This suggests that while VHWs play a role in increasing referrals, additional efforts may be needed to strengthen their impact in promoting HTS during pregnancy.

The increase in referrals from the combined model for children within the intervention group underscores the benefit of the multi-prong approach in the context of HTS for children. Children often encounter distinctive hurdles when accessing healthcare services, including HTS, owing to their reliance on caregivers and the imperative for age-appropriate testing and care (Bhutta et al., Citation2014). Engaging various healthcare providers and community-based sources in the referral process can effectively address these challenges. However, it is noteworthy that the evidence supporting standalone community mobilisation efforts was comparatively weaker in this study. This may be attributed to the fact that the primary target of the intervention was women. For future studies, it is useful to explore models that directly focus on children as the primary beneficiaries of HTS interventions. This approach could potentially yield more robust outcomes in terms of referrals and access to vital healthcare services for children.

In this study, other members of the communities such as facility-based health workers, husbands and relatives were said to have referred pregnant women for HTS in all the study locations. This suggests that there is an increasing awareness and acceptance of the importance of HIV testing and treatment among these stakeholders. The involvement of husbands and relatives is particularly important, as they play a significant role in decision-making regarding health care-seeking behaviour, especially for women and children. Husbands’ support in health seeking behaviours and utilisation of health services has long been known as a high positive correlate for women and child health issues (Yogman & Eppel, Citation2022), and this prospect can be harnessed in these communities for higher utilisation of HTS at health facilities. Engaging these stakeholders in community mobilisation efforts can help to increase uptake of HIV testing services among pregnant women and children, as additional community structures along with those tested in this study.

A limitation of this study is its focus on specific local government areas (LGAs) within Taraba State, Nigeria, which possess unique characteristics and may not be representative of the entire country or other geographical areas. Nevertheless, the study provides a proof of concept that engaging existing community structures can be effective in HIV prevention and care. In addition, it is important to note that the data collected through household surveys relied on self-reporting, introducing the possibility of recall bias. Participants may not have accurately remembered their exposure to and utilisation of HIV testing services (HTS), or the exposure and utilisation of HTS by children in their households. The DID methodology presents several limitations. It crucially relies on the assumption that, in the absence of the intervention, the treatment and control groups would have followed parallel trends over time; any deviation from this assumption can introduce bias. Additionally, it assumes that external factors, beyond the treatment, do not influence outcomes, although unexpected events or policy changes outside the study’s scope can confound results (notably, no significant policy changes affecting the intervention occurred during the study period). Furthermore, DID assumes a uniform treatment effect across all units in the treatment group, which may not universally hold true, particularly since community mobilisers may not have reached every place of the intervention LGAs. Typically, DID requires longitudinal data for both treatment and control groups, which may not always be readily available or feasible to collect; in our study, due to the intervention’s nature (requiring participants to have delivered a child in the past year), we conducted two rounds of surveys, at the beginning and end of the intervention, within the same geographical location among eligible but different sets of individuals each time. Finally, it’s important to note that the findings from a DID analysis may not always generalise to other contexts, as the results are specific to the study’s time and place.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the effectiveness of community-based interventions in improving HIV testing services among pregnant women and children in a Nigerian setting. The findings of this study suggest that community-based interventions involving TBAs, VHWs, and PPMVs have the potential to significantly increase the proportion of women referred for HIV testing. However, the increase in the proportion of women referred for the test did not translate into a corresponding increase in the number of women who actually went for the test in all the intervention LGAs, indicating a need for further efforts to improve the uptake of HIV testing and counselling services. There were on-going community-based activities in the LGAs to refer women and their children for HTS. VHW, PPMVs and TBAs participated in referring pregnant women and their children although the number of such referrals were few. The knowledge gap in mother-to-child transmission of HIV presents a viable opportunity for health promotion on PMTCT and this should be pursued. This study shows that PPMV, TBA and VHW as community-based referral mechanisms were underused resources in HIV interventions therefore their roles should be strengthened in identifying and referring pregnant women and children for HIV services.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.4 KB)Acknowledgement

We wish to thank all the participants who contributed their time and effort to the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adebimpe, W. O. (2013). Challenges facing early infant diagnosis of HIV among infants in resource poor settings. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 17(1), 122–129.

- Adeleke, S. I., Mukhtar-Yola, M., & Gwarzo, G. D. (2009). Awareness and knowledge of mother-to-child transmission of HIV among mothers attending the pediatric HIV clinic, Kano, Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine, 8(4), 210–214. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.59573

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

- Bhutta, Z. A., Das, J. K., Bahl, R., Lawn, J. E., Salam, R. A., Paul, V. K., Sankar, M. J., Blencowe, H., Rizvi, A., Chou, V. B., & Walker, N. (2014). Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? The Lancet, 384(9940), 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3

- Doctor, H. V., Findley, S. E., & Afenyadu, G. Y. (2012). Estimating maternal mortality level in rural Northern Nigeria by the sisterhood method. International Journal of Population Research, 2012, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/464657

- Ford, N., Ball, A., Baggaley, R., Vitoria, M., Low-Beer, D., Penazzato, M., Vojnov, L., Bertagnolio, S., Habiyambere, V., Doherty, M., & Hirnschall, G. (2018). The WHO public health approach to HIV treatment and care: looking back and looking ahead. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 18(3), e76–e86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30482-6

- Grant, M., Wilford, A., Haskins, L., Phakathi, S., Mntambo, N., & Horwood, C. M. (2017). Trust of community health workers influences the acceptance of community-based maternal and child health services. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 9(1), a1281. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1281

- Heath, K., Levi, J., & Hill, A. (2021). The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS 95-95-95 targets: Worldwide clinical and cost benefits of generic manufacture. AIDS, 35(Supplement 2), S197–S203. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002983

- Homeida, M., Braide, E., Elhassan, E., Amazigo, U. V., Liese, B., Benton, B., Noma, M., Etya’alé, D., Dadzie, K. Y., Kale, O. O., & Sékétéli, A. (2002). APOC’s strategy of community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) and its potential for providing additional health services to the poorest populations. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, 96(Suppl. 1), S93–S104. https://doi.org/10.1179/000349802125000673

- Itiola, A. J., & Agu, K. A. (2018). Country ownership and sustainability of Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS supply chain system: Qualitative perceptions of progress, challenges and prospects. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice, 11(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-018-0148-8

- Khumalo-Sakutukwa, G., Morin, S. F., Fritz, K., Charlebois, E. D., van Rooyen, H., Chingono, A., Modiba, P., Murumbi, K., Visrutaratna, S., Singh, B., Sweat, M., Celentano, D. D., & Coates, T. J. (2008). Project accept (HPTN 043): A community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49(4), 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a6cb5

- Kumar, A., Singh, B., & Kusuma, Y. S. (2015). Counselling services in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) in Delhi, India: An assessment through a modified version of UNICEF-PPTCT tool. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 5(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jegh.2014.12.001

- Lewin, S., Munabi-Babigumira, S., Glenton, C., Daniels, K., Bosch-Capblanch, X., van Wyk, B. E., Odgaard-Jensen, J., Johansen, M., Aja, G. N., Zwarenstein, M., & Scheel, I. B. (2010). Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2010(3), CD004015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3

- Marsh, D. R., Hazel, E., & Nefdt, R. (2014). Medical special issue: Integrated community case management (iCCM) at scale in Ethiopia: Evidence and experience. Ethiopian Medical Journal, 52(Sup. 3), 47–54.

- Mphatswe, W., Blanckenberg, N., Tudor-Williams, G., Prendergast, A., Thobakgale, C., Mkhwanazi, N., McCarthy, N., Walker, B. D., Kiepiela, P., & Goulder, P. (2007). High frequency of rapid immunological progression in African infants infected in the era of perinatal HIV prophylaxis. AIDS, 21(10), 1253–1261. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281a3bec2

- NACA. (2019). Revised national HIV and AIDS strategic framework: 2021–2025. National Agency for the Control of HIV/AIDS, 8, 15–20.

- Scanlon, M. L., & Vreeman, R. C. (2013). Current strategies for improving access and adherence to antiretroviral therapies in resource-limited settings. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 5, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S28912

- Shrestha, R., Altice, F. L., Huedo-Medina, T. B., Karki, P., & Copenhaver, M. (2017). Willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): An empirical test of the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model among high-risk drug users in treatment. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1299–1308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1650-0

- Sinai, I., Anyanti, J., Khan, M., Daroda, R., & Oguntunde, O. (2017). Demand for women’s health services in Northern Nigeria: A review of the literature. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 21(2), 96. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.11

- Singh, S., Srivastava, A., Haldane, V., Chuah, F., Koh, G., Seng Chia, K., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2017). Community participation in health services development: A systematic review on outcomes. European Journal of Public Health, 27(Suppl_3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckx187.429

- Spooner, E., Govender, K., Reddy, T., Ramjee, G., Mbadi, N., Singh, S., & Coutsoudis, A. (2019). Point-of-care HIV testing best practice for early infant diagnosis: An implementation study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 731. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6990-z

- Sweat, M., Morin, S., Celentano, D., Mulawa, M., Singh, B., Mbwambo, J., Kawichai, S., Chingono, A., Khumalo-Sakutukwa, G., Gray, G., Richter, L., Kulich, M., Sadowski, A., & Coates, T. (2011). Community-based intervention to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043): A randomised study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 11(7), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70060-3

- UNAIDS. (2020). Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the centre. Author.

- UNAIDS. (2022). In danger: UNAIDS global AIDS update 2022. Author.

- University of Minnesota. (2016). Sociology: Understanding and changing the social world. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing.

- Wamalwa, D., Benki-Nugent, S., Langat, A., Tapia, K., Ngugi, E., Slyker, J. A., Richardson, B. A., & John-Stewart, G. C. (2012). Survival benefit of early infant antiretroviral therapy is compromised when diagnosis is delayed. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 31(7), 729–731. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3182587796

- White, J., Callahan, S., Lint, S., Li, H., & Yemaneberhan, A. (2016). Engaging private health providers to extend the global availability of PMTCT services: Strengthening high impact interventions for an AIDSfree generation (AIDSFree) project. JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc.

- Xu, Z., Ma, P., Chu, M., Chen, Y., Miao, J., Xia, H., & Zhuang, X. (2020). Understanding the role of voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) in HIV prevention in Nantong, China. BioMed Research International, 2020, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5740654

- Yogman, M. W., & Eppel, A. M. (2022). The role of fathers in child and family health. In M. Grau-Grau, M. las Heras Maestro, & H. Riley Bowles (Eds.), Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality: Healthcare, social policy, and work perspectives (pp. 15–30). Springer.