ABSTRACT

Foodborne illnesses result from inadequate food handling practices, but prevention is possible through implementing food safety principles by handlers and consumers. This paper presents an overview of food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers and consumers in the Gulf countries, identifies factors affecting knowledge and practice, and offers recommendations for promoting food safety among handlers and consumers. A literature search was conducted using an integrative review method. Various combinations of the following descriptors were used: (food safety, food hygiene), (knowledge, practice), and (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait). Out of 164 studies screened, 37 met the eligibility criteria. Food handler studies reported insufficient food safety knowledge, with poor translation of existing knowledge into practice. Consumer studies showed varying levels of food safety knowledge, and the translation of existing knowledge into practice was also found to be inconsistent. Training and educational level were the primary factors positively affecting food safety knowledge and practices. Overall, significant gaps in knowledge and practices were identified among food handlers and consumers in the Gulf. These gaps require urgent attention from the Gulf regulatory bodies to develop targeted food safety training and education programs to enhance awareness and implementation of food safety principles.

1. Introduction

Despite ongoing efforts in recent years, food safety continues to be a major concern worldwide. The Gulf Cooperation Council (hereafter referred to as the Gulf), which comprises Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain, is no exception. According to the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Saudi Arabia, a total of 1632 foodborne outbreaks were reported between 2014 and 2018, resulting in 11,458 illnesses. Nearly half of these outbreaks occurred in public settings such as restaurants, catering, and banquet facilities, while the other half occurred in private homes (MOH, Citation2018). The most common causes of foodborne outbreaks in Saudi Arabia were Salmonella, Bacillus cereus, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), and Staphylococcus aureus (MOH, Citation2018). The mortality rates observed in outbreaks associated with households were significantly greater, potentially due to the relatively larger proportion of children among the affected individuals (MOH, Citation2018). Although countrywide reports on foodborne illnesses are scarce in other Gulf countries, several sporadic outbreaks have been recorded (Al-Abri et al., Citation2011; Al-Maqbali et al., Citation2021; Faour-Klingbeil & Todd, Citation2020; Todd, Citation2017a). For instance, a Salmonella outbreak with 101 cases was recently linked to the consumption of contaminated food at a local restaurant in Oman (Al-Maqbali et al., Citation2021). It should be noted that many individuals affected by gastrointestinal illnesses do not seek medical attention, and not all physicians collect stool samples for microbiological testing. As a result, many foodborne illnesses remain unreported. Moreover, these findings only account for a small proportion (less than 1%) of the actual burden of foodborne diseases in the Gulf region (Todd, Citation2017b).

Given that the majority of reported cases of foodborne illness occur in commercial food services and households, food handlers and consumers play an essential role in the prevention of foodborne diseases. Most cases of foodborne illnesses are preventable if food handlers and consumers adhere to food safety principles (Al-Makhroumi et al., Citation2022; Ayaz et al., Citation2018; Jevšnik et al., Citation2008; Redmond & Griffith, Citation2003). The World Health Organization (WHO) has outlined five key principles of food safety, which include general cleanliness, separation of raw and cooked products, thorough cooking, food storage at safe temperatures, and the use of safe water and raw materials (Alimentarius, Citation2020). Therefore, safe handling practices of food service workers in food establishments are vital to protect consumer health and minimise the risk of foodborne diseases. In addition, as producers cannot guarantee a pathogen-free food supply, consumers at home play a critical role in the food chain to avoid foodborne illnesses (Wilcock et al., Citation2004). Food safety knowledge and practices can play a fundamental role in preventing such diseases (Ripabelli et al., Citation2017; Tamburro et al., Citation2017; Zanin et al., Citation2017). Therefore, obtaining information on this subject is crucial in developing effective food safety education and training programmes aimed at reducing the risks associated with inadequate food handling by food workers or consumers (Faour-Klingbeil, Citation2022).

The Gulf countries, which share many cultural and socio-economic similarities such as traditional food products, religious beliefs, ethnicity, reliance on migrant workers, and language, face significant challenges in ensuring food safety in the region. These challenges are mainly due to several factors, including the absence of training or national food safety programmes, immature traceability systems for foodborne diseases, climate conditions, and the unique cultural background of the Gulf countries (Tajkarimi et al., Citation2013; Todd, Citation2017a). In addition, the rapid growth of the tourism industry in the region demands progressive policies to guarantee food safety. The fact that up to two-thirds of the food consumed in the region is imported from outside the Gulf presents an even greater challenge to ensuring food safety (Todd, Citation2017a). The presence of multiple agencies responsible for ensuring food safety and tracing foodborne incidents instead of a single agency makes it challenging to communicate food safety issues and take prompt action towards these issues (Todd, Citation2017a).

Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate food safety knowledge and practices among food workers and consumers across diverse regions and settings within the Gulf ( and ). Considering that the Gulf countries share similar social, political, economic, and cultural characteristics, as well as food safety systems, this article presents an overview of food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers and consumers in the Gulf, identifies the factors affecting knowledge and practice, and offers recommendations to enhance food safety for both handlers and consumers.

Table 1. Description of the studies that addressed food safety knowledge and/or practices of food handlers in Gulf countries.

Table 2. Description of the studies that addressed food safety knowledge and/or practices of consumers in Gulf countries.

2. Approach

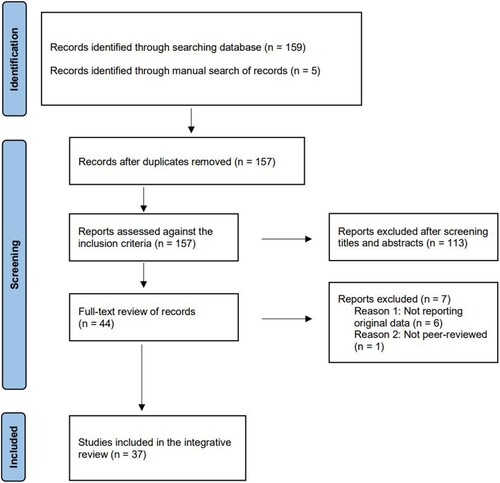

Data collection and analysis were conducted using the integrative review methodology. This method allows for the combination of diverse data sources to synthesise existing knowledge and provide new insights on a given topic (Torraco, Citation2016). shows an overview of the selection process using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant studies, an extensive literature search was conducted using the electronic databases Scopus, Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Science, and PubMed. The following search terms were used in various combinations: ‘food safety’ or ‘food hygiene,’ ‘knowledge’ or ‘practice,’ and the names of Gulf countries including ‘Saudi Arabia’, ‘Qatar’, ‘Emirates’, ‘UAE’, ‘Bahrain’, ‘Oman’, or ‘Kuwait’. Titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles were screened to assess their eligibility for inclusion in the review. The inclusion criteria were: A) addressing the knowledge and/or practices of food handlers or consumers regarding food safety, B) conducted in Gulf countries (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, and Bahrain), C) peer-reviewed, D) reporting original data, and E) published in English or Arabic within the last 10 years (2012-2022). A manual search of the references and citations in the included papers was also conducted to retrieve additional relevant articles. The search was performed to ensure comprehensive coverage of the available literature on the knowledge and practices of food handlers and consumers regarding food safety in the Gulf region. After further evaluation, 37 out of the initial 164 articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. General characteristics of the included studies

The majority of the studies included in this review (26/37) were published since the year 2019, indicating a recent growing interest in evaluating the knowledge and practices of food safety in the Gulf region. Of these studies, 18 addressed food handlers, while 19 focused on consumers. Descriptions of studies addressing food safety knowledge and/or practices of food handlers and consumers are shown in and , respectively. Nearly half of these studies (19/37) were conducted in Saudi Arabia, with the remaining studies conducted in UAE (8/37), Kuwait (4/37), Oman (3/37), and Qatar (3/37). Interestingly, no studies were conducted in Bahrain. It is important to note that Saudi Arabia’s population is larger than the combined population of the other five Gulf countries (Iqbal et al., Citation2021), which could explain the higher number of studies conducted in this country. The included studies were conducted in various settings, including schools/universities (10/37), food service establishments (10/37), households (8/37), hospitals (5/37), and multiple settings (4/37). Most studies (25/37) included both female and male participants, while the remaining studies included only one gender, either females (9/37) or males (2/37), and one study did not report gender. Among studies on food handlers, data were collected using self-administered questionnaires (10/18), face-to-face interviews (5/18), or a combination of both methods (3/18). For studies on consumers, self-administered questionnaires were the main data collection method (18/19), with only one study using face-to-face interviews. Overall, the analysis of food safety knowledge and practices in the included studies relied mostly on descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation of correct answers. Many studies calculated overall scores for different topics, such as cross-contamination, foodborne diseases, and personal hygiene. However, there were different cut-off points used to determine whether the level of knowledge or practice was good, moderate, or poor, which could limit the comparability of findings across studies. In most cases, the overall food safety knowledge or practice was based on the authors’ interpretation of the scores of each topic.

3.2. Food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers in Gulf countries

3.2.1. Food safety knowledge

The level of food safety knowledge varied among the included studies, but overall, the knowledge in the areas of cross-contamination, foodborne diseases, and foodborne pathogens was found to be low (). Studies conducted in the Gulf region have primarily focused on food handlers working in hospitals, universities, and restaurants. Some studies conducted in hospitals in Saudi Arabia (Alqurashi et al., Citation2019; Alrasheed et al., Citation2021) and Kuwait (Moghnia et al., Citation2021) concluded that the overall food safety knowledge among catering workers and supervisors was acceptable. However, these studies also highlighted some concerning gaps in food safety knowledge. For example, over 90% of food handlers answered that they would continue working if they were sick until the illness was confirmed, and one-third of food handlers said they would not report sickness to avoid being unpaid (Alrasheed et al., Citation2021). Similarly, a study conducted in Al Madinah hospitals found that more than half of food handlers had poor knowledge regarding foodborne pathogens, factors affecting microbial growth, and cross-contamination; approximately 40% of them did not know the recommended temperature for refrigerated foods (Alqurashi et al., Citation2019). Abdelhafez (Citation2013) reported low levels of knowledge about foodborne pathogens and food storage temperatures among food handlers working in Makkah hospitals. These findings are particularly concerning because food service staff in hospitals provide meals to vulnerable patients who may have compromised immune systems. Saudi regulations mandate that hospitals comply with Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) as part of the Saudi Nutrition Service Programme, but some state hospitals have not implemented the system (Abdelhafez, Citation2013). Even in hospitals where HACCP is implemented, there are gaps in the knowledge of food service staff and supervisors related to HACCP principles. For example, approximately 40% of food handlers working in state hospitals did not understand the objective of the HACCP system (Alqurashi et al., Citation2019), while almost half of the catering supervisors were found to have inadequate knowledge about HACCP principles (Alrasheed et al., Citation2021).

Foodborne outbreaks are more frequent in food service establishments in schools and universities compared to other settings (Albgumi et al., Citation2019; Sani & Siow, Citation2014). As many students visit on-campus restaurants, it is crucial for food handlers in university settings to have adequate food safety knowledge and practices to prevent foodborne illnesses (Ripabelli et al., Citation2017; Tamburro et al., Citation2017). In a survey conducted at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia (Al-Shabib et al., Citation2016), food handlers were found to have good knowledge of personal hygiene but poor knowledge about basic temperature control requirements, foodborne pathogens, and cross-contamination. Alarmingly, one-third of food handlers in this study also reported that they would handle food while ill or when having cuts and wounds. This behaviour is not allowed according to the regulations set by the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (FDA), which strictly prohibits any person with infections or diarrheal diseases from handling food or entering food preparation areas. In contrast, food service staff at Princess Nourah University had adequate food safety knowledge according to a study by Albgumi et al. (Citation2019), which could be attributed to the fact that the food handlers at Princess Nourah University were females, while those in the Al-Shabib et al. (Citation2016) study were males. Similarly, a study conducted in fast-food restaurants at Qatar University by Elobeid et al. (Citation2019) found that two-thirds of food handlers had insufficient knowledge about cross-contamination and danger zone temperature, and failed to identify Salmonella as a foodborne pathogen.

The worldwide increase in food consumption outside the home highlights the importance of restaurant supervisors in monitoring employees and implementing food safety measures (Taha et al., Citation2020a). A study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Al-Mohaithef et al. (Citation2021) found that restaurant supervisors had good knowledge of safe temperatures for cold food but lacked adequate knowledge of the danger zone and safe temperatures for hot food. In addition, the authors observed that supervisors working in international restaurants had lower levels of food safety knowledge compared to their counterparts working in local restaurants. A study conducted in Dubai, UAE (Taha et al., Citation2020b) concluded that restaurant food handlers had a high level of food safety knowledge. However, another study conducted in Dubai and Sharjah, UAE, reported that food handlers had a lower level of food safety knowledge (Taha et al., Citation2020a). The difference in findings could be attributed to variations in survey questions, protocols, and participant demographic characteristics (Taha et al., Citation2020b).

Studies from other Gulf countries also reported gaps in food safety knowledge among restaurant workers. Ali et al. (Citation2018) reported that food handlers in Salalah, Oman had adequate knowledge of personal hygiene and sanitation but lacked knowledge of foodborne pathogens and temperature control. Al-Ghazali et al. (Citation2020) reported low-to-moderate levels of food safety knowledge among restaurant workers in Oman. In Kuwait, Al-Kandari et al. (Citation2019) and Allafi et al. (Citation2020) reported acceptable levels of food safety knowledge among food handlers in restaurants but noted that they lacked knowledge of foodborne pathogens, time and temperature control, and cross-contamination. These studies suggest that food handlers have some food safety knowledge, but the major gaps in their knowledge concerning cross-contamination and food temperature control could pose consumer health risks.

3.2.2. Food safety practices

Although it is expected that food handlers translate their food safety knowledge into practice, it is important to note that knowledge alone may not necessarily lead to improved practices (Da Cunha et al., Citation2014; Medeiros et al., Citation2011). In this review, only half of the studies that evaluated food handlers included an assessment of food safety practices, and these studies reported moderate levels of food safety practices among food handlers. Albgumi et al. (Citation2019) found high levels of compliance with food safety practices among food handlers at Princess Nourah University, and reported a positive correlation between knowledge and practice. Similarly, food handlers at King Saud University had good personal hygiene practices despite their inadequate knowledge (Al-Shabib et al., Citation2016). Elobeid et al. (Citation2019) concluded that the level of food safety practices among food handlers working in fast-food restaurants at Qatar University was satisfactory, and reported a positive correlation between food safety knowledge and practice. In Kuwaiti restaurants, Al-Kandari et al. (Citation2019) also found a positive correlation between knowledge and practice among food handlers.

In contrast, four studies indicated that there was an insufficient translation of knowledge into practice among food handlers (Ali et al., Citation2018; Asim et al., Citation2019; El-Nemr et al., Citation2019; Moghnia et al., Citation2021). Ali et al. (Citation2018) observed that food safety knowledge of restaurant workers in Oman was not translated into practice. Similarly, Asim et al. (Citation2019) reported that food safety managers in food service establishments in Qatar did not translate their knowledge into practice. El-Nemr et al. (Citation2019) found that the application of knowledge into practice was poor among produce handlers working in the wholesale produce market in Doha, Qatar. In Kuwait, Moghnia et al. (Citation2021) concluded that the food safety knowledge of food handlers in community and hospital settings did not translate into practice. Similarly, a comprehensive international review by Zanin et al. (Citation2017) found that nearly half of the included studies reported no proper translation of knowledge into practice. The findings of these studies suggest that there is a need to bridge the gap between food safety knowledge and practice among food handlers.

3.2.3. Factors affecting food safety knowledge and practices of food handlers

Exploring the association between food safety knowledge and practices and the factors affecting them among food handlers may facilitate the development of customised training programmes that address specific needs and challenges. Studies included in this review have identified several factors that have been found to affect food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers. Many of these studies have reported statistically significant associations between food safety knowledge/practices and specific factors based on the sociodemographic characteristics of food handlers, including their food safety training, education level, and years of experience. Specifically, five studies reported that enrolment in food safety training was associated with better food safety knowledge/practices among food handlers (Al-Kandari et al., Citation2019; Alqurashi et al., Citation2019; Asim et al., Citation2019; Taha et al., Citation2020a; Taha et al., Citation2020b). Eight studies found that workers with higher educational levels had better food safety knowledge/practices than those with lower educational levels (Abdelhafez, Citation2013; Al-Mohaithef et al., Citation2021; Alqurashi et al., Citation2019; Asim et al., Citation2019; El-Nemr et al., Citation2019; Moghnia et al., Citation2021; Taha et al., Citation2020a; Taha et al., Citation2020b). Asim et al. (Citation2019) noted that food service managers with higher education levels were more likely to receive food safety training and implement better food safety practices. This, in turn, increased the probability of their staff receiving food safety training as well. Additionally, two studies reported a positive relationship between years of work experience and food safety knowledge/practices (Taha et al., Citation2020a; Taha et al., Citation2020b), whereas one study found lower food safety knowledge among food handlers with more years of experience (Moghnia et al., Citation2021).

3.3. Food safety knowledge and practices among consumers in Gulf countries

3.3.1. Food safety knowledge

Consumer knowledge of food safety is a crucial factor in reducing the risk of foodborne diseases. Studies included in this review predominantly focused on assessing the food safety knowledge of students and household members (). The results of these studies revealed varying levels of food safety knowledge. A study conducted at the Electronic University in Saudi Arabia reported that students had adequate knowledge about food safety (AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020). However, a study by Al-Shabib et al. (Citation2017) revealed that students at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, demonstrated good knowledge about hand hygiene and preventing cross-contamination, but lacked sufficient knowledge regarding temperature control for food. Similarly, Almansour et al. (Citation2016) found significant gaps in food safety knowledge among primary and secondary school students in Majmaah city, Saudi Arabia. In the same city, Banawas (Citation2020) reported that most college students lacked knowledge about the potential risks associated with consuming raw foods. Moreover, a recent study conducted in Kuwait by Ashkanani et al. (Citation2021) reported that more than 90% of students were unaware of proper food cooking and holding temperatures. Likewise, a global survey found that a significant number of consumers, particularly young adults aged 21–25 from Asia and Africa, lacked awareness regarding the potential spoilage of food when left at room temperature for extended periods (Odeyemi et al., Citation2019).

In Saudi Arabia, numerous studies have been conducted to assess the food safety knowledge of women, who are often responsible for preparing food for their families. Arfaoui et al. (Citation2021) surveyed 1490 women and found that the majority lacked knowledge about proper food storage and holding temperatures, while one-third had poor knowledge of cross-contamination prevention. Similarly, Farahat et al. (Citation2015) found that almost half of the interviewed Saudi women had inadequate knowledge about cleaning food utensils and equipment, proper food storage, and cooking temperatures. Alsayeqh (Citation2015) reported that nearly half of the surveyed Saudi women had insufficient knowledge about food-holding temperatures, and one-third lacked knowledge about cross-contamination and proper cooking temperatures. Ayaz et al. (Citation2018) conducted a survey of 979 mothers in Saudi Arabia and found that, while mothers had moderate knowledge about proper food storage and kitchen hygiene, their knowledge of food handling was inadequate. Similarly, Ayad et al. (Citation2022) reported that almost half of the household members surveyed in Saudi Arabia had insufficient knowledge about physical hazards, and two-thirds were not aware of refrigerator or freezer temperatures. Alhashim et al. (Citation2022) also reported that approximately half of the surveyed Saudi consumers lacked sufficient knowledge about food safety. Shati et al. (Citation2021) surveyed 3011 parents from Aseer province in Saudi Arabia and found that half of the participants had poor knowledge about food safety, particularly in relation to handling and consumption of raw or undercooked foods and foodborne intoxications. These findings are concerning as parents are typically responsible for preparing food for their children.

Outside Saudi Arabia, Al-Makhroumi et al. (Citation2022) evaluated the food safety knowledge among female employees at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman and found that 91% of the participants had low levels of food safety knowledge. In the UAE, Osaili et al. (Citation2022) found that approximately 40% of surveyed women in Dubai had inadequate knowledge about the prevention of cross-contamination and proper handwashing. Moreover, only 8.3% of the participants followed cooking instructions, and 23.9% were aware of the potential risk of drinking unpasteurised milk. In another study conducted in Sharjah, UAE (Saeed et al., Citation2021), nearly 50% of the surveyed women had poor knowledge about food cooking and holding temperatures, and around 80% lacked knowledge about foodborne disease risk factors. However, Afifi and Abushelaibi (Citation2012) reported adequate food safety knowledge among surveyed consumers in Al Ain, UAE. Overall, these studies highlight significant gaps in food safety knowledge among consumers in the Gulf region, particularly concerning proper food storage and holding temperatures, prevention of cross-contamination, and safe handling of raw or undercooked foods.

3.3.2. Food safety practices

Consumer studies showed varying levels of translation of food safety knowledge into practice. Al-Shabib et al. (Citation2017) reported a correlation between food safety knowledge and self-reported practices, except for temperature control. Farahat et al. (Citation2015) and Al-Makhroumi et al. (Citation2022) found that surveyed consumers had better food safety practices than knowledge. In contrast, Arfaoui et al. (Citation2021) found that most food safety knowledge was not translated into practice. Shati et al. (Citation2021) reported unsafe food safety practices among Saudi parents, including not washing their hands after touching animals or washing fruits and vegetables before consumption. Another study conducted at Majmaah University found that the majority of students (93%) did not wash their hands with soapy water before eating food (Banawas, Citation2020). Ayad et al. (Citation2022) noted good food safety practice levels in their study, except for the fact that over 80% of participants were unaware of the consequences of thawing food at room temperature. These findings correspond with previous research conducted in other regions, which have also reported inconsistent relationships between knowledge and practices (Patil et al., Citation2005; Redmond & Griffith, Citation2003; Young et al., Citation2017).

3.3.3. Factors affecting food safety knowledge and practices of consumers

The education level of consumers was found to be the main factor affecting food safety knowledge and practices. Ten studies reported that higher levels of education were associated with better food safety knowledge and practices (Afifi & Abushelaibi, Citation2012; AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020; Alhashim et al., Citation2022; Arfaoui et al., Citation2021; Ayad et al., Citation2022; Ayaz et al., Citation2018; Farahat et al., Citation2015; Osaili et al., Citation2022; Saeed et al., Citation2021; Shati et al., Citation2021). Seven studies found a correlation between consumer age and their level of food safety knowledge and practice (Al-Makhroumi et al., Citation2022; AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020; Arfaoui et al., Citation2021; Farahat et al., Citation2015; Mohamed, Citation2022; Osaili et al., Citation2022; Shati et al., Citation2021). Five studies found that employed individuals demonstrated better food safety knowledge and practices compared to those who were unemployed (Arfaoui et al., Citation2021; Farahat et al., Citation2015; Osaili et al., Citation2022; Saeed et al., Citation2021; Shati et al., Citation2021). Additionally, other factors have been reported to impact food safety knowledge and practices, including gender (AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020; Ayad et al., Citation2022; Shati et al., Citation2021), marital status (Alhashim et al., Citation2022; Arfaoui et al., Citation2021), having children (Arfaoui et al., Citation2021), and academic discipline (AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020).

3.4. Remarks and recommendations

3.4.1. Regarding food handlers

The reported gaps in food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers in the Gulf region warrant immediate attention from authorities. It is crucial for food handlers to have the necessary knowledge to handle food safely and understand their role in preventing food contamination. Therefore, it is highly recommended that every food service establishment has at least one supervisor who is adequately trained in food safety, possesses the necessary knowledge to identify potential risks of food contamination, and is capable of taking appropriate corrective actions to address any potential issues. The supervisor should also take responsibility for training and educating their staff in food safety practices, thus fostering a proactive food safety culture within the establishment. Regular training and education programmes should be provided to supervisors to ensure their continuous professional development and to keep them informed about the latest food safety practices and regulations. Dubai Municipality has made it mandatory for food service establishments to have at least one certified person in charge (PIC) in food safety present whenever food is prepared or served (Dubai Municipality, Citation2020). Similarly, by 2024, the Saudi FDA will require all food service establishments with five or more employees to have a food protection plan that includes at least one supervisor with sufficient training in food safety, food protection, and risk management (SFDA, Citation2020).

The presence of a food safety supervisor should not substitute food safety training for all food handlers in the same establishment. It is recommended that governing authorities provide educational resources and training courses on food safety for free. Training is the most commonly used and effective approach for enhancing food safety knowledge and practices (Medeiros et al., Citation2011). Considering that most Gulf countries do not have mandatory training requirements for those who handle food, it is strongly recommended that food safety training becomes mandatory and that untrained food handlers should not be allowed to work on food premises without proper training. Murphy et al. (Citation2011) found that mandatory training for individuals responsible for food handling resulted in a positive impact on their food safety knowledge and behaviour. Effective training programmes should include only relevant information and consider the education levels and languages of food handlers (Sani & Siow, Citation2014; Zanin et al., Citation2017). According to a systematic review on factors affecting safe food handling at retail and food service (Thaivalappil et al., Citation2018), language was a barrier among food handlers, with difficulty in communication being noted between managers and staff, as well as between health inspectors and operators. To address the issue of limited proficiency in Arabic and English among many food handlers in Abu Dhabi, UAE, the food safety training programme was offered in the four most widely spoken languages by the majority of food handlers (Todd, Citation2017a). To ensure effective food safety training, it is important to identify and correct unsafe practices observed while working in the establishment (Adesokan et al., Citation2015; McFarland et al., Citation2019). A systematic review by Levy et al. (Citation2022) found that the effect of training interventions on safe handling practices was found to diminish over time.

Management in food service establishments should evaluate worker satisfaction after training because worker satisfaction can be an indicator of the effectiveness of the training, can increase awareness of the importance of food safety practices, and encourage adherence to proper procedures (Tokuç et al., Citation2009). It is advisable that supervisors regularly quiz their employees about hygiene and safety-related issues to ensure that they maintain adequate food safety knowledge and to identify any areas that may require further training (Todd, Citation2017b). Authorities should have a legislative requirement to regularly evaluate food safety knowledge of food handlers. One effective way to meet this requirement is by implementing a system for food safety certificates or cards, similar to the hygiene passports required in Finland. These certificates can be obtained by passing a test covering essential food safety topics, such as food contamination, basic microbiology, personal hygiene, cleaning and sanitation, foodborne diseases, and legislation (Vaarala et al., Citation2021). It is important to note that management should not only clarify to workers that they should not report to work when sick but also ensure that there would be no deduction to their salary for being absent from work. This approach will encourage workers to prioritise food safety and prevent the spread of foodborne diseases.

Despite being mandatory in hospitals, studies have shown that not all hospitals comply with the implementation of the HACCP system. Even when the HACCP system is implemented, it is often executed poorly, leading to ineffective outcomes (Abdelhafez, Citation2013; Alqurashi et al., Citation2019; Alrasheed et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is necessary for researchers to develop a standardised HACCP assessment tool that can evaluate HACCP plans in different settings, identify weaknesses, failures, and gaps that hinder successful implementation, and for authorities to ensure effective compliance with HACCP. Additionally, HACCP implementation should be mandated not only in hospitals but also in other settings, such as small-sized food businesses, to ensure food safety for consumers.

3.4.2. Regarding consumers

Food handling, preparation, and storage practices at the household level are not subject to monitoring or regulation, leaving consumers to rely on their own food safety knowledge and practices. Even when dining outside the home, the food safety knowledge of consumers is critical for identifying the risks associated with the food consumed at commercial food services. Therefore, increasing the awareness of consumers about safe food handling practices is a key intervention for maintaining food safety, serving as the last line of defense on the food chain against foodborne diseases (Flynn et al., Citation2019). Based on the findings of the reviewed studies, it is clear that there are significant gaps in both food safety knowledge and practice among consumers in Gulf countries. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no national education programme in the Gulf countries aimed at promoting food safety knowledge and practices among consumers. Therefore, it is imperative for Gulf countries to establish a national education programme that focuses on enhancing food safety knowledge and practices, with special attention given to high-risk groups such as older adults and immunocompromised individuals. To minimise the risks of foodborne illnesses, effective food safety messaging should focus on personal hygiene, prevention of cross-contamination, proper food cooking and holding temperatures, and avoiding risky foods. The messaging should be simple and easy to understand for all consumers, regardless of their background or education level, employing sources widely used by different groups of consumers. To develop effective food safety messages, it is important to utilise data from transdisciplinary science to assess and prioritise consumer food handling practices, and to understand consumer behaviour (Langsrud et al., Citation2023). Implementation science can also be employed through expert surveys to analyze the effectiveness of these messages. The content of the messages should include information about risks and motivational content, accompanied by appropriate graphics, and should be tailored to the target audience and consider the risk profile specific to each group (Langsrud et al., Citation2023).

One study included in this review (AL-Mohaithef et al., Citation2020) found that government websites and social media were the most commonly used sources to seek information about food safety among Saudi students. Therefore, it is recommended that authorities utilise these media channels to create effective communication interventions aimed at enhancing consumers’ understanding of food safety. While governing authorities in the Gulf have already used their official Twitter accounts to educate the public about food safety, more needs to be done. Of note, students participating in AL-Mohaithef et al.’s (Citation2020) study were generally younger in age, which could explain their preference for Internet sources. Similarly, previous research has indicated that younger individuals tend to rely more on the Internet for information, while older individuals prefer mass media and other sources (Kuttschreuter et al., Citation2014; Tiozzo et al., Citation2019). The use of government websites as the main source of information is a sign of public trust in governing authorities. To maintain such trust, it is essential for governing authorities to be transparent and responsive to consumer concerns regarding food safety issues. Information about foodborne outbreaks and actions taken to address these issues should be immediately shared with the public to enhance their food safety knowledge (FAO, Citation2023).

Understanding consumer behaviour can guide the development of effective interventions. Young and Waddell (Citation2016) observed that food-handling practices were mostly shaped by daily routines, unconscious actions, and personal experiences. Similarly, Young et al. (Citation2017) conducted a systematic review and found that consumers’ safe food handling behaviours were consistently impacted by attitudes, risk perceptions, habits, subjective norms, and levels of self-confidence and control. This information can be leveraged to devise strategies that promote food safety among consumers. For example, creating new habits and routines by establishing a new ‘norm’ can be achieved through hands-on training in unfamiliar environments, such as community settings (e.g. centres, schools, etc.) (Warde, Citation2014; Young & Waddell, Citation2016). Another example is to target young adults and children who are still developing their habits and may have limited food-handling experience. Targeting school-aged children may also positively influence their parents’ practices at home, leading to a broader impact (Young et al., Citation2015).

Evaluating consumers’ knowledge about food safety can help governments identify specific groups that need education, supporting the creation and evaluation of educational programmes (Uggioni & Salay, Citation2013). The accuracy and understanding of future research findings would be influenced by using a valid and reliable questionnaire. It is important to stress the need for trustworthy tools to measure the general public’s knowledge of food safety. To achieve this, experts should evaluate the relevance of survey questions to the specific areas of knowledge being studied to establish content validity. Then, it is recommended to establish criteria for validity and construct validity, such as comparing two groups with different knowledge levels to assess discriminative validity. For reliability, commonly used methods include evaluating internal consistency and test-retest procedures (Iorio & Konicki, Citation2005; Uggioni & Salay, Citation2013).

Strengthening national food safety governance is crucial in significantly improving food safety standards. According to WHO/FAO (Citation2003), an effective food safety system requires efficient regulations and laws, inspection services, monitoring and surveillance systems for food, surveillance systems for foodborne diseases, and education and training on food safety. However, Gulf countries mostly rely on a multiple-agency system for food safety, which can result in a lack of coordination, confusion over jurisdiction, over-regulation or inadequate regulatory activity, and decreased confidence in the system’s credibility among consumers. To overcome these challenges, Gulf countries should consider consolidating all food safety responsibilities into a single food control agency with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, as recommended by FAO and WHO.

4. Conclusion

Based on a comprehensive review of 37 articles, this review highlights significant gaps in food safety knowledge and practices among food handlers and consumers in the Gulf countries, emphasising the need to bridge the gap between existing knowledge and practice. The review provides valuable insights for policymakers, researchers, and food service management, by enabling the development of national education programmes, effective food safety interventions, and identification of areas for improvement in food safety practices and staff training. This can lead to better food safety outcomes for consumers in the Gulf region. Studies evaluating food safety knowledge and practice have targeted females more frequently than males, with claims that studies targeting females are lacking. Therefore, future studies should aim to include both males and females in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of food safety knowledge and practice among both genders. Although food safety knowledge and practices have been evaluated in most Gulf countries, there is a lack of information on consumers in Qatar and no studies conducted in Bahrain, highlighting the need for further research. To ensure the effectiveness of food safety interventions, it is essential to understand consumer preferences for sources of food safety information. Thus, food safety knowledge and practice studies should incorporate questions about consumers’ preferred sources. Future studies should encompass various Gulf countries and settings, such as homes and supermarkets, using standardised methodologies to ensure comparability of findings across studies. it is also necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of different food safety training methods and assess consumers’ food safety knowledge to enhance food safety practices in the region.

Acknowledgments

The researcher would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University for funding the publication of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

Data are from publicly available sources.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdelhafez, A. M. (2013). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food service staff about food hygiene in hospitals in Makkah area, Saudi Arabia. Life Science Journal, 10(3), 1079–1085.

- Abushelaibi, A., Jobe, B., Al Dhanhani, F., Al Mansoori, S., & Al Shamsi, F. (2016). An overview of food safety knowledge and practices in selected schools in the city of al ain, United Arab Emirates. African Journal of Microbiology Research, 10(15), 511–520. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR2016.7917

- Adesokan, H. K., Akinseye, V. O., & Adesokan, G. A. (2015). Food safety training is associated with improved knowledge and behaviours among foodservice establishments’ workers. International Journal of Food Science, 1, 1–18.

- Afifi, H. S., & Abushelaibi, A. A. (2012). Assessment of personal hygiene knowledge, and practices in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Food Control, 25(1), 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.10.040

- Al-Abri, S. S., Al-Jardani, A. K., Al-Hosni, M. S., Kurup, P. J., Al-Busaidi, S., & Beeching, N. J. (2011). A hospital acquired outbreak of Bacillus cereus gastroenteritis, Oman. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 4(4), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2011.05.003

- Al-Beesh, F., Al-Ammar, W., & Goja, A. M. (2019). Assessing the knowledge, behavior and practices of food safety and hygiene among Saudi women in Eastern province, Saudi Arabia. European Journal of Nutrition & Food Safety, 10(3), 178–186.

- Albgumi, M. B., Binshaieg, N. A., Alshaifani, T. A., Alajlan, H. A., Almater, R. S., & Bakry, H. M. (2019). Food safety and hygiene among food handlers at princess Norah Bint Abdulrahman university canteens. International Research Journal of Public and Environmental Health, 6(7), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.15739/irjpeh.19.019

- Al-Ghazali, M., Al-Bulushi, I., Al-Subhi, L., Rahman, M. S., & Al-Rawahi, A. (2020). Food safety knowledge and hygienic practices among different groups of restaurants in Muscat, Oman. International Journal of Food Science, 2020, 8872981. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8872981

- Alhashim, L. A., Alshahrani, N. Z., Alshahrani, A. M., Khalil, S. N., Alrubayii, M. A., Alateeq, S. K., & Zakaria, O. M. (2022). Food safety knowledge and attitudes: A cross-sectional study among Saudi consumers from food trucks owned by productive families. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4322. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074322

- Ali, M. A., Shuaib, Y. A., Ibrahaem, H. H., Suliman, S. E., & Abdalla, M. A. (2018). Food safety knowledge among food workers in restaurants of Salalah municipality in Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Horticulture, Agriculture and Food Science, 2(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.22161/ijhaf.2.2.1

- Alimentarius, C. (2020). General principles of food hygiene. Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice, No. CXC 1-1969. Codex Alimentarius Commission, 5, 2–6.

- Al-Kandari, D., Al-abdeen, J., & Sidhu, J. (2019). Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in restaurants in Kuwait. Food Control, 103, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.03.040

- Allafi, A. R., Al-Kandari, D., Al-Abdeen, J., & Al-Haifi, A. R. (2020). Cross-cultural differences in food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers working at restaurants in Kuwait. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(4), e2020181. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i4.8614

- Al-Makhroumi, N., Al-Khusaibi, M., Al-Subhi, L., Al-Bulushi, I., & Al-Ruzeiqi, M. (2022). Development and validation of a food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices (KAP) questionnaire in Omani consumers. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2022.02.001

- Almansour, M., Sami, W., Al-Rashedy, O. S., Alsaab, R. S., Alfayez, A. S., & Almarri, N. R. (2016). Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of food hygiene among school students’ in Majmaah city, Saudi Arabia. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 66(4), 442–446.

- Al-Maqbali, A. A., Al-Abri, S. S., Vidyanand, V., Al-Abaidani, I., Al-Balushi, A. S., Bawikar, S., El Amir, E., Al-Azri, S., Kumar, R., Al-Rashdi, A., & Al-Jardani, A. K. (2021). Community foodborne of Salmonella weltevreden outbreak at northern governorate, sultanate of Oman. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 11(2), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.210404.001

- AL-Mohaithef, A., Padhi, B. K., Shameel, M., Elkhalifa, A. M., Tahash, M., Chandramohan, S., & Hazazi, A. (2020). Assessment of foodborne illness awareness and preferred information sources among students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Food Control, 112, 107085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107085

- Al-Mohaithef, M., Abidi, S. T., Javed, N. B., Alruwaili, M., & Abdelwahed, A. Y. (2021). Knowledge of safe food temperature among restaurant supervisors in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Food Quality, 2021, 2231371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2231371

- Alqurashi, N. A., Priyadarshini, A., & Jaiswal, A. K. (2019). Evaluating food safety knowledge and practices among foodservice staff in al Madinah hospitals, Saudi Arabia. Safety, 5(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety5010009

- Alrasheed, A., Connerton, P., Alshammari, G., & Connerton, I. (2021). Cohort study on the food safety knowledge among food services employees in Saudi Arabia state hospitals. Journal of King Saud University-Science, 33(6), 101500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101500

- Alsayeqh, A. F. (2015). Foodborne disease risk factors among women in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Food Control, 50, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.08.036

- Al-Shabib, N. A., Husain, F. M., & Khan, J. M. (2017). Study on food safety concerns, knowledge and practices among university students in Saudi Arabia. Food Control, 73, 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.08.005

- Al-Shabib, N. A., Mosilhey, S. H., & Husain, F. M. (2016). Cross-sectional study on food safety knowledge, attitude and practices of male food handlers employed in restaurants of King Saud university, Saudi Arabia. Food Control, 59, 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.05.002

- Arfaoui, L., Mortada, M., Ghandourah, H., & Alghafari, W. (2021). Food safety knowledge and self-reported practices among Saudi women. Current Nutrition & Food Science, 17(8), 891–901. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573401317666210322115237

- Ashkanani, F., Husain, W., & AlDwairji, M. A. (2021). Assessment of food safety and food handling practice knowledge among college of basic education students, Kuwait. Journal of Food Quality, 2021, 5534034. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5534034

- Asim, H. S., Elnemr, I., Goktepe, I., Feng, H., Park, H. K., Alzeyara, S., AlHajri, M., & Kushad, M. (2019). Assessing safe food handling knowledge and practices of food service managers in Doha, Qatar. Food Science and Technology International, 25(5), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1082013219830843

- Ayad, A. A., Abdulsalam, N. M., Khateeb, N. A., Hijazi, M. A., & Williams, L. L. (2022). Saudi Arabia household awareness and knowledge of food safety. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 11(7), 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11070935

- Ayaz, W. O., Priyadarshini, A., & Jaiswal, A. K. (2018). Food safety knowledge and practices among Saudi mothers. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 7(12), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7120193

- Banawas, S. S. (2020). Food poisoning knowledge, attitudes and practice of students in Majmaah university. Majmaah Journal of Health Sciences, 7(2), 1. https://doi.org/10.5455/mjhs.2019.02.002

- Da Cunha, D. T., Stedefeldt, E., & De Rosso, V. V. (2014). The role of theoretical food safety training on Brazilian food handlers’ knowledge, attitude and practice. Food Control, 43, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.03.012

- Dubai Municipality. (2020). Food Code 2020. https://www.dm.gov.ae [Accessed 20 January 2023].

- El-Nemr, I., Mushtaha, M., Irungu, P., Asim, H., Tang, P., Hasan, M., & Goktepe, I. (2019). Assessment of food safety knowledge, self-reported practices, and microbiological hand hygiene levels of produce handlers in Qatar. Journal of Food Protection, 82(4), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-18-191

- Elobeid, T., Savvaidis, I., & Ganji, V. (2019). Impact of food safety training on the knowledge, practice, and attitudes of food handlers working in fast-food restaurants. British Food Journal, 121(4), 937–949. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-01-2019-0066

- FAO. (2023). Contribution of terrestrial animal source food to healthy diets for improved nutrition and health outcomes – an evidence and policy overview on the state of knowledge and gaps. Rome.

- Faour-Klingbeil, D. (2022). Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices among food handlers in foodservice establishments in the Arab countries of the Middle East. In I. Savvaidis & T. Osaili (Eds.), Food safety in the Middle East (pp. 227–273). Elsevier.

- Faour-Klingbeil, D., & Todd, E. (2020). Prevention and control of foodborne diseases in middle-east north African countries: Review of national control systems. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010070

- FAO/WHO. Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization. (2003). Assuring food safety and quality: Guidelines for strengthening national food control systems.

- Farahat, M. F., El-Shafie, M. M., & Waly, M. I. (2015). Food safety knowledge and practices among Saudi women. Food Control, 47, 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.07.045

- Flynn, K., Villarreal, B. P., Barranco, A., Belc, N., Björnsdóttir, B., Fusco, V., Rainieri, S., Smaradottir, S. E., Smeu, I., Teixeira, P., & Jörundsdóttir, HÓ. (2019). An introduction to current food safety needs. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 84, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2018.09.012

- Iorio, D., & Konicki, C. (2005). Measurement in health behavior: Methods for research and education (Vol. 1). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Iqbal, J., Ahmad, S., Sher, A., & Al-Awadhi, M. (2021). Current epidemiological characteristics of imported malaria, vector control status and malaria elimination prospects in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Microorganisms, 9(7), 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9071431

- Jevšnik, M., Hoyer, S., & Raspor, P. (2008). Food safety knowledge and practices among pregnant and non-pregnant women in Slovenia. Food Control, 19(5), 526–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2007.06.005

- Kuttschreuter, M., Rutsaert, P., Hilverda, F., Regan, Á, Barnett, J., & Verbeke, W. (2014). Seeking information about food-related risks: The contribution of social media. Food Quality and Preference, 37, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.04.006

- Langsrud, S., Veflen, N., Allison, R., Crawford, B., Izsó, T., Kasza, G., Lecky, D., Nicolau, A. I., Scholderer, J., Skuland, S. E., & Teixeira, P. (2023). A trans disciplinary and multi actor approach to develop high impact food safety messages to consumers: Time for a revision of the WHO-five keys to safer food? Trends in Food Science & Technology, 133, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2023.01.018

- Levy, N., Hashiguchi, T. C. O., & Cecchini, M. (2022). Food safety policies and their effectiveness to prevent foodborne diseases in catering establishments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Research International, 156, 111076.

- McFarland, P., Checinska Sielaff, A., Rasco, B., & Smith, S. (2019). Efficacy of food safety training in commercial food service. Journal of Food Science, 84(6), 1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/1750-3841.14628

- Medeiros, C. O., Cavalli, S. B., Salay, E., & Proença, R. P. C. (2011). Assessment of the methodological strategies adopted by food safety training programmes for food service workers: A systematic review. Food Control, 22(8), 1136–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.02.008

- Moghnia, O. H., Rotimi, V. O., & Al-Sweih, N. A. (2021). Evaluating food safety compliance and hygiene practices of food handlers working in community and healthcare settings in Kuwait. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041586

- MOH. (2018). التقـــرير السنوي لفاشيات الأمراض المنقولة بالغذاء. https://www.moh.gov.sa/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Documents/2014-2018.pdf [Accessed December 13, 2022].

- Mohamed, R. R. (2022). Assessment of the level of knowledge and practices of food safety-rafha-kingdom of Saudi Arabia. مجلة البحوث في مجالات التربية النوعية, 8(42), 899–924. https://doi.org/10.21608/JEDU.2022.118592.1589

- Murphy, K. S., DiPietro, R. B., Kock, G., & Lee, J. S. (2011). Does mandatory food safety training and certification for restaurant employees improve inspection outcomes? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 150–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.04.007

- Odeyemi, O. A., Sani, N. A., Obadina, A. O., Saba, C. K. S., Bamidele, F. A., Abughoush, M., Asghar, A., Dongmo, F. F. D., Macer, D., & Aberoumand, A. (2019). Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices among consumers in developing countries: An international survey. Food Research International, 116, 1386–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.030

- Osaili, T., Shaker Obaid, R., Taha, S., Kayyaal, S., Ali, R., Osama, M., Alajmi, R., Al-Nabulsi, A. A., Olaimat, A., Hasan, F., & Ayyash, M. (2021). A cross-sectional study on food safety knowledge amongst domestic workers in the UAE. British Food Journal, 124(3), 1009–1021. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2020-1124

- Osaili, T.M., Saeed, B.Q., Taha, S., Omar Adrees, A. and Hasan, F. (2022). Knowledge, practices, and risk perception associated with foodborne illnesses among females living in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 11(3), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030290

- Patil, S. R., Cates, S., & Morales, R. (2005). Consumer food safety knowledge, practices, and demographic differences: Findings from a meta-analysis. Journal of Food Protection, 68(9), 1884–1894. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-68.9.1884

- Redmond, E. C., & Griffith, C. J. (2003). Consumer food handling in the home: A review of food safety studies. Journal of Food Protection, 66(1), 130–161. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-66.1.130

- Ripabelli, G., Mastronardi, L., Tamburro, M., Forleo, M. B., & Giacco, V. (2017). Food consumption and eating habits: A segmentation of university students from Central-South Italy. New Medit: Mediterranean Journal of Economics, Agriculture and Environment = Revue Méditerranéenne d’Economie Agriculture et Environment, 16(4), 56.

- Saeed, B. Q., Osaili, T. M., & Taha, S. (2021). Foodborne diseases risk factors associated with food safety knowledge and practices of women in Sharjah-United Arab Emirates. Food Control, 125, 108024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108024

- Sani, N. A., & Siow, O. N. (2014). Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers on food safety in food service operations at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Food Control, 37, 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.036

- SFDA-Saudi Food and Drug Administration. (2020). Food hygiene requirements. https://sfda.gov.sa/en/regulations/68665 [Accessed 24 January 2023].

- Shati, A. A., Al Qahtani, S. M., Shehata, S. F., Alqahtani, Y. A., Aldarami, M. S., Alqahtani, S. A., Alqahtani, Y. M., Siddiqui, A. F., & Khalil, S. N. (2021). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards food poisoning among parents in Aseer region, southwestern Saudi Arabia. Healthcare, 9(12), 1650. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121650

- Taha, S., Osaili, T. M., Saddal, N. K., Al-Nabulsi, A. A., Ayyash, M. M., & Obaid, R. S. (2020a). Food safety knowledge among food handlers in food service establishments in United Arab Emirates. Food Control, 110, 106968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106968

- Taha, S., Osaili, T. M., Vij, A., Albloush, A., & Nassoura, A. (2020b). Structural modelling of relationships between food safety knowledge, attitude, commitment and behavior of food handlers in restaurants in jebel Ali Free Zone, Dubai, UAE. Food Control, 118, 107431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107431

- Tajkarimi, M., Ibrahim, S. A., & Fraser, A. M. (2013). Food safety challenges associated with traditional foods in Arabic speaking countries of the Middle East. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 29(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2012.10.002

- Tamburro, M., Ripabelli, G., Forleo, M. B., & Sammarco, M. L. (2017). Dietary behaviours and awareness of seasonal food among college students in central Italy: Diet and knowledge on seasonal food among college students. Italian Journal of Food Science, 29(4), 14674.

- Thaivalappil, A., Waddell, L., Greig, J., Meldrum, R., & Young, I. (2018). A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research studies on factors affecting safe food handling at retail and food service. Food Control, 89, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.01.028

- Tiozzo, B., Pinto, A., Mascarello, G., Mantovani, C., & Ravarotto, L. (2019). Which food safety information sources do Italian consumers prefer? Suggestions for the development of effective food risk communication. Journal of Risk Research, 22(8), 1062–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1440414

- Todd, E. C. (2017a). Foodborne disease and food control in the Gulf states. Food Control, 73, 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.08.024

- Todd, E. C. (2017b). Foodborne disease in the Middle East. Water, Energy & Food Sustainability in the Middle East, 389–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-48920-9_17

- Tokuç, B., Ekuklu, G., Berberoğlu, U., Bilge, E., & Dedeler, H. (2009). Knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices of food service staff regarding food hygiene in Edirne, Turkey. Food Control, 20(6), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.08.013

- Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: Using the past and present to explore the future. Human Resource Development Review, 15(4), 404–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484316671606

- Uggioni, P. L., & Salay, E. (2013). Reliability and validity of a questionnaire to measure consumer knowledge regarding safe practices to prevent microbiological contamination in restaurants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 45(3), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2011.09.007

- Vaarala, A., Uusitalo, L., Lundén, J., & Tuominen, P. (2021). The relevance of the Finnish hygiene passport test. Food Control, 130, 108254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108254

- Warde, A. (2014). After taste: Culture, consumption and theories of practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 14(3), 279–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540514547828

- Wilcock, A., Pun, M., Khanona, J., & Aung, M. (2004). Consumer attitudes, knowledge and behaviour: A review of food safety issues. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 15(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2003.08.004

- Young, I., Reimer, D., Greig, J., Turgeon, P., Meldrum, R., & Waddell, L. (2017). Psychosocial and health-status determinants of safe food handling among consumers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Control, 78, 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.03.013

- Young, I., & Waddell, L. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to safe food handling among consumers: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research studies. PLoS One, 11(12), e0167695. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167695

- Young, I., Waddell, L., Harding, S., Greig, J., Mascarenhas, M., Sivaramalingam, B., Pham, M. T., & Papadopoulos, A. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of food safety education interventions for consumers in developed countries. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2171-x

- Zanin, L. M., da Cunha, D. T., de Rosso, V. V., Capriles, V. D., & Stedefeldt, E. (2017). Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in food safety: An integrative review. Food Research International, 100, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.042