ABSTRACT

Currently, Nepal is not on track to meet Sustainable Development Goal 5.3 – the elimination of harmful practices, including child, early and forced marriage by the year 2030. Evidence on what works to prevent child, early and forced marriage often is inattentive to contextual factors that influence intervention effectiveness. This study presents qualitative results of a mixed-methods evaluation of CARE’s Tipping Point Program to prevent child, early and forced marriage in Nepal, interrogating the perceived benefits of the programme and elucidating contextual features that enhance or detract from programme benefit. Baseline data included interviews with adolescent girls (N = 20), boys (N = 10), adult community leaders (N = 8) and focus group discussions (FGDs) with girls (N = 8 groups; 48 individuals), boys (N = 8 groups; 47 individuals) and parents (N = 16 groups; 95 individuals). Using thematic analysis and structured comparisons by time, gender, district, caste/community, stakeholder type and arm, we found diverse programme participation, but widespread improvements in knowledge across several domains, with behavioural changes concentrated among participants with stronger participation and pre-programme characteristics suggestive of low risk of child marriage. Findings underscore the need to address structural barriers to prevent child marriage and the challenges of attributing programme benefit amidst a dynamic social context.

Highlights

New or enhanced knowledge was the most frequently reported benefit of the programme among participants.

The TPI failed to address the structural barriers and clustering of risk among those most vulnerable to CEFM.

Adolescents described enduring risk or protection from CEFM, which set the stage for the degree of participation and perceived benefit.

Findings support calls to better align programming to address structural barriers and the needs of those most vulnerable to CEFM.

Introduction

Approximately 650 million women and girls alive today were married as children – below the age of 18 (United Nations Children's Fund, Citation2018). In most regions of the world, child marriage is declining, down by 15% over the last decade (United Nations Children's Fund, Citation2018). Declines in child marriage in Nepal are similar (United Nations Children's Fund, Citation2018) but may be plateauing (MacQuarrie & Juan, Citation2019). The slowing decline and the still sizable proportion of women marrying as children in Nepal (Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Citation2020) affirm that Nepal, along with other countries in South Asia and all other regions of the world, will not meet Sustainable Development Goal 5.3 – the elimination of harmful practices, including child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) by the year 2030 (Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Citation2020). The well-documented harms to girls’ physical, emotional and social well-being, the intergenerational impacts on their children and the associated economic costs (Wodon et al., Citation2017) provide ample justification for enhanced understanding of what works to prevent CEFM.

Evaluations of CEFM prevention strategies are accelerating (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021b). However, a recent systematic review identified only 31 experimental or quasi experimental studies of CEFM prevention in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) published between 2000 and 2019 (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). This review, and several prior reviews of the evidence base (Chae & Ngo, Citation2017; Kalamar et al., Citation2016; Lee-Rife et al., Citation2012; Owusu-Addo et al., Citation2018; Yount et al., Citation2017) demonstrate mixed effectiveness and deficits in rigour evidenced by having to exclude studies on the basis of quality ratings. The one prior test of an intervention designed to prevent CEFM in Nepal exemplifies these findings. It was quasi-experimental, graded as low quality per the recent systematic review, and demonstrated mixed results on the proportion of girls 14–21 who married during the study (effective in urban populations, ineffective in rural populations) (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021a). Many interventions delivered in South Asia suffer from the same limitations, necessitating more rigorous testing.

Evidence on what works to prevent CEFM also points to the role of participant, familial and social factors that influence the effectiveness of CEFM interventions (Muthengi et al., Citation2021). Intervention types successful in one setting have shown divergent results in others (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021a). Commonly identified drivers of CEFM, such as poverty, gender inequality and marriage decision-making (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021b; Petroni et al., Citation2017; Psaki et al., Citation2021) manifest differently across and within countries (Cislaghi et al., Citation2019; McDougal et al., Citation2020) suggesting that contextualised intervention approaches are needed. Finally, the degree of girls’ vulnerability at the start of programming and the availability and acceptability of alternatives to CEFM have been shown to influence intervention effectiveness (Makino et al., Citation2021).

To address this gap, Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) made a multi-year investment in two districts in Nepal (Kapilvastu and Rupandehi) to understand the nature and context of CEFM finding that a complex interplay of geographic isolation, poverty, limited livelihood options, norms and multi-stakeholder marriage processes with limited input from girls drove the persistence of CEFM (Karim et al., Citation2016). CARE used these findings to inform the development of the CARE Tipping Point Program (TPP) which is multi-stakeholder, community-based intervention designed to address the root causes of CEFM, promote adolescent rights, challenge social expectations and repressive gender norms, and promote girl-centric and girl-led activism (Yount et al., Citation2021). A similar process was undertaken in Bangladesh in cooperation with International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) (Parvin et al., Citation2022). The focus of this analysis is the qualitative evaluation of the TPP in Nepal. The study was a rigorous, mixed-methods three-arm (core intervention, enhanced intervention and control) cluster randomised trial (cRCT). The quantitative portion of the c-RCT found no impact of the programme on reducing the rate of child marriage and only limited impact on girls’ agency, including improvements in girls’ knowledge of sexual and reproductive health and increased participation in community groups among those participating in the enhanced intervention relative to control (Yount et al., Citation2023). This paper presents the longitudinal qualitative results of the trial to examine the changes in social norms and girls’ agency perceived to be attributable to TPP in a purposive sample of participants in two intervention arms – core and enhanced. The paper also elucidates contextual features that enhanced or detracted from perceived programme benefit. This information can be used to refine interventions and research strategies toward greater effectiveness.

Methods

Study setting

The qualitative component of the Nepal TPI impact evaluation was conducted in eight project sites, two in each of the two intervention arms in each of the two study districts. These adjacent districts are in the Lumbini Province in Nepal, bordering India. According to the most recent UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey in 2019, a nationally representative survey of men and women ages 15–49 years, more than one third of women 20–24 (33.7%) and women 18–49 (38.3%) were in a CEFM (Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Citation2020). Baseline qualitative findings for the c-RCT revealed widespread perceptions that child marriage and gauna (transition to conjugal life) were in decline. The research team identified at-risk girls as those who were not studying in school or who were perceived as disobedient (especially, girls who were suspected of being in a relationship with boy). Elopement was recognised as a contributor to CEFM, as adolescents taking this route to marriage were generally younger, and fears of elopement incentivised parents to marry their daughter expeditiously to a match of their choice. Love marriages were perceived to be more acceptable among the more educated, but the prevailing expectation was for girls to marry based on their parent’s choice, with the ultimate authority being fathers or male heads of household (Bergenfeld et al., Citation2019; Morrow et al., Citation2022).

Intervention

PP focuses on the synchronised engagement of different participant groups (adolescent girls and boys, parents, community members and community leaders) around four programmatic pillars including: social norms; access to alternatives to CEFM; adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights; and girls-centered movement building (Manuals – Tipping Point Initiative-CARE (caretippingpoint.org)). The core TPP approach entailed weekly group sessions for boys and girls and monthly sessions with fathers and mothers of participants. For all four participant groups these sessions focused on building an understanding of social norms that underpin gender inequities and CEFM, building basic literacy in adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights, and foster joint intergenerational dialogues. In addition, girls also participated in sessions designed to promote financial literacy and the establishment of savings groups, strengthening leadership, collective action, civic participation skills and capacities, and activists training. A social norms enhanced package also was tested, which contained the core programming along with intensive trainings and follow-up meetings with religious leaders, local government officials, and school personnel, election of girl leaders, and girl-led community-based activities designed to shift social norms. Due to the COVID pandemic, the intervention had to be altered including: a reduction in programme duration from 18 to 16 months, a reduction in post-programme ‘freeze’ period from 12 to 8 months, a reduced number of sessions and community-based activities, and a five month pause in programming from March to July 2020 (Yount et al., Citation2023).

Sample

The sample for the qualitative component of the impact evaluation included adolescent girls, adolescent boys, parents of adolescents and community stakeholders in eight clusters, four core and four enhanced. Eligible adolescents (unmarried, 12–16 years of age, living in the selected cluster, and not having plans to migrate in the subsequent 24 months) were identified from a household listing in each cluster. Parents of eligible adolescents were themselves eligible with half of the sample being chosen because their child participated in TPP while the other half was chosen because their child did not participate. Community stakeholders were eligible if they were identified as a local leader by TPP partners and contacts.

Baseline data included in-depth interviews (IDIs) with 20 adolescent girls and 10 adolescent boys, 8 key informant interviews (KIIs) with adult community leaders, 16 FGDs (8 groups with adolescent girls (N = 48 individuals) and 8 groups with adolescent boys (N = 47 individuals)), and 16 FGDs with parents of adolescents in study communities, 8 groups of which were parents of adolescent study participants (N = 48 individuals) and 8 groups with parents of adolescents not enrolled at the study at baseline to provide a point of comparison for perceived norms change (N = 47 individuals). Follow-up of all participants was attempted at endline. All KIIs and adolescent boy IDI participants were retained. Of the IDIs, 2 girl adolescent IDI participants were replaced. One IDI participant was inadvertently switched with a baseline FGD participant and one participant married and left the study area. Replacement IDIs data were retained for analysis. All FGD discussion groups were retained; however, 23 members of the original total 190 (12.1%) did not participate at endline.

Procedures

The team’s local collaborating partner on the research had experience working in the selected districts, with adults and adolescents, and on sensitive topics, including violence. Male and female data collectors were recruited to enable gender-matching with participants. Data collectors and field supervisors had experience collecting data on sensitive topics, qualitative research experience, and local language (Awadhi and Bhojpuri) proficiency. A 10-day training was conducted just prior to baseline and just prior to endline. Training content included information about the project and study design, gender and norms, researching sensitive topics, building rapport, interview etiquette, instrument content, consent, research ethics, adverse events, safety plan and logistics. The training was administered using a mix of didactics, role play, individual and group feedback, mock testing, and a pilot test. The qualitative and quantitative teams were trained together for core common content but were split into two separate tracks for method specific training and practice.

A short-list of eligible participants who had agreed to participate in programming was prepared which included contact information from the household listing. The firm used this list to contact eligible participants in the field, with the aid of CARE's local implementing partner when needed to locate a potential respondent. This process was repeated at endline. KIIs were conducted in worksites or the respondents’ homes, while IDIs were conducted in the respondents’ homes or outside the homes when needed for privacy. FGDs were organised in schools or community sites. Adult participants provided written informed consent. For adolescents, adults provided written informed consent, and adolescents provided their separate assent to participate. All interviews and FGDs adhered to international ethical standards on research on violence against women which included in part being conducted in privacy, referral to additional support services, and gender-matched data collection (Yount et al., Citation2021). The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (00109419) and the Nepal Health Research Council (576/2021 P) was subjected to continuing review at Emory University. Baseline data collection occurred 7–20 June 2019. Follow-up data collection occurred 3–20 December 2021, after an 8-month freeze period, during which there was no intervention or research contact.

Data and analysis

The qualitative data collection guides were based on ones developed for a companion study occurring in Bangladesh (Parvin et al., Citation2022; Yount et al., Citation2021). The guides were translated into Nepali and back translated into English to check the quality of the translation. Since the sponsor wanted to maintain the ability to do cross site comparisons at a later date, content of the tools remained as similar as possible. The tools were subject to a pilot test, which suggested that they were well understood, but needed to be shortened from the Bangladesh tools; however, core content was retained across all tools (). IDIs with adolescents provided narrative data on attitudes and perceptions towards gender roles, life aspirations, girls’ safety and security, and girls’ mobility, and at endline, collective action and participation in TPI. FGDs with adolescents and parents were based on CARE’s social norms analysis plot framework (Stefanik & Hwang, Citation2017), highlighting social norms surrounding girls’ mobility or freedom of movement, decision-making around marriage, and interaction with boys, and at endline, collective action. KIIs with teachers and local officials assessed perceived changes in the prevalence of child marriage, social norms and practices around marriage, work and education, girls’ safety and security, and collective action. At endline, questions pertaining to change were interspersed throughout the interview guides, with explicit interrogation of perceived changes due to TPI occurring only at the end of the instrument.

Table 1. Topics addressed in the interview and group discussion guides, by stakeholder, qualitative evaluation of the tipping point programme in Nepal.

Interviews with girls, boys, and key informants lasted on average 52, 53 and 65 min, respectively. Focus group discussions with girls, boys, and parents lasted an average of 84, 74 and 72 min, respectively. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed by the data collectors to enhance accuracy, and translated into English for analysis. As the same study was occurring in Bangladesh at the same time and had the same research questions, the team did not develop a new codebook, but instead streamlined and adapted a codebook developed by icddr,b for use in Nepal. The analysis team revised the codebook in several stages, first through careful reading of 10 transcripts and discussions with CARE and icddr,b; second, after two rounds of intercoder reliability testing among three Emory team members using seven transcripts, and finally, after the three team members coded 20 transcripts across two sites. Team debriefs were used to resolve discrepancies and make minor edits to codes and definitions, after which the same team divided the remaining 50 transcripts to code individually. At study endline, one additional code to reflect TPP participation was added to the codebook. Inter-rater reliability testing was repeated with a new analytic team prior to coding. All coding, cross-classification and inter-coder reliability testing was performed in MAXQDA V.18 (Berlin, Germany).

As the study is part of a trial with specific research questions, the interpretation was structured similarly. However, emergent themes were explored as they arose, and the narratives of participants were privileged throughout. A narrative analysis of IDIs with adolescents began with memos of each transcript summarising apriori themes related to adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH), aspirations, marriage, mobility, safety and security. Descriptive analysis of social norms data across all 70 transcripts was performed by crossing each major theme with relevant norms codes (normative expectations (belief about what others expect one to do), empirical expectations (belief about what others do) and sanctions/sensitivity to sanctions, exceptions). Thick descriptions (detailed, contextualised descriptions and interpretations) were generated for each theme. At endline, we repeated the above process and conducted structured comparisons between baseline and endline data within themes. Potential differences by gender, district, caste/community, stakeholder type and arm were explored. We explored attribution of impact to the TPP programme by interrogating participant reported reasons for change by theme and noted where change was attributed spontaneously by the participant to the programme or if attribution was made in response to specific questioning. Interpretation of the findings involved integrating findings from the analysis of all transcripts at baseline and endline with the micro-level longitudinal analysis of the adolescent IDIs. All coding and analysis were done with analysts blinded to the study arm through completion of the thick descriptions. Two focus group discussions with community stakeholders occurred in August 2023 to share and validate findings.

Results

Sample description

In all sites, adolescents were on average approximately 14 years of age while parents were in their fourties and stakeholders were in the mid to late thirties (). The caste/ethnicity of the respondents was different across the districts and the arms, with the largest differences across districts. Religious minorities, especially Muslims were much more prominent in the sample from Kapilvastu compared to Rupandehi which had a more even distribution of Terai castes, Janajatis and Dalits with no Muslim participants except among parents in Rupandehi. The stakeholders in both Kapilvastu and Rupandehi were of Terai castes and Janajatis in Kapilvastu and high caste, other Terai caste and Janajatis in Rupandehi.

Table 2. Sample demographics, qualitative evaluation of the tipping point programme in Nepal (N = 228).

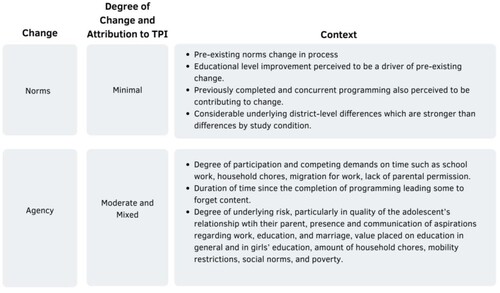

The impact of the intervention is presented, below, starting with perceived changes in norms followed by perceived change at the levels of the participants and their families in light of their level of participation. The section concludes with insights that emerged pertaining to the characteristics of participants who reported considerable benefit and those who ultimately were married or arranged to be married by endline, highlighting qualitative differences in potential underlying risk of these two sets of participants ().

Norms: Minimal social norms change but pronounced differences by district

The normative environment in which TPP was implemented was complex, showing change over time in some norms and less change over time in most others. Across districts and arms, most stakeholders noted that ‘empirical expectations’ regarding age at marriage had shown substantial change before baseline, although CEFM was clearly not eradicated, evidenced by examples of child marriage among study participants, and reports of child marriage among sisters, relatives and friends. Still, most participants reported marriage in late teens or after age 20 to be general practice while very early marriage was said to generally be a thing of the past.

P5: … daughters were married at an early age but now the parents wait until their daughter turns 20. This is applicable everywhere. We ourselves won’t get our daughters married at an early age. We will firstly make them independent before marrying them. This doesn’t cause much shame now. (Father group, Kapilvastu, core)

It is up to the girl to decide at what age and with whom the marriage will take place if she likes the boy first of all and the parents have to support her. If the girl doesn’t like the boy, everyone in the family as well as the girl should be involved. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, enhanced)

People fear that their daughters might choose wrong paths in life. They don’t have trust upon their daughters and they think that she might elope. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, enhanced)

Across all stakeholder groups and districts, girls are still expected to accept their father’s final decision on a marriage. Participants residing in Kapilvastu more frequently mentioned the importance of maintaining family honour and were more sensitive to sanctions surrounding marriage decision-making, namely from community members who backbite or start rumours about girls who reject proposals. So, while expectations of later marriage are becoming more widespread, and the potential is expanding for girls to influence the process, decision-making remains in the hands of their fathers.

Overall, little normative change was detectable in the sample over the course of the study. Instead, participants mentioned repeatedly their perceptions of declines in marriage already underway at baseline, such as shifts in many communities toward later ages at marriage, girls’ ability to talk to boys about schoolwork, and greater consultation of boys and girls regarding marriage, with some cracks, albeit limited mostly to educated families, in girls’ ability to influence the marriage process. Further, differences by district were repeatedly mentioned while differences by arm were not detectable. However, similar to the perceived benefits of the programme, changes in norms were attributable in part to TPP in general, which was noted as a source of education and awareness raising among families and in the community, often alongside other programmes that had come before or were concurrent. Participants in the enhanced TPP arm also reported perceived benefit to their community from their community-based activities. However, the most frequently mentioned driver of social norms change was improvements in the educational status of the community and the increasing enrolment of girls in school.

Agency and the role of participation

Varied programming participation

A prerequisite to benefiting from programming is engaging with it. In core and TPP enhanced sites, participants in the qualitative sample described a variety of degrees of participation in the intervention, from those who were very engaged, missing only a few sessions, to those who attended few or no programme sessions. For the parents and community stakeholders, participation in programming varied based on competing demands on their time and level of interest. Among the community stakeholders in the analysis, the majority had little engagement, either due to competing demands on their time, or in a few instances, due to reports of being invited infrequently or not being invited at all, although a few of the stakeholders were quite aware of the programming and described TPP’s its benefits to the participating adolescents and their families. Among the adolescents, across both programme arms, participation varied from regular to almost none. One study participant mentioned that her programme group lost 10 members over the course of programme implementation, although the study participant herself was heavily involved. According to study participants, reasons for not attending programme sessions ranged from migration, work, or school responsibilities to a lack of parental support or permission. ‘I went there but only two or three times. I wanted to go but my mother didn’t allow me to. I really wanted to go’ (Adolescent girl, Kapilvastu, Maharajgunj 1). Much of the programmatic content was the same in the core and enhanced programme arms, namely weekly discussion groups, which were described as very interactive, such as including games. Clearly differentiated between sites across the two programme arms was mention of rallies, a cooking competition, and other collective events involving the community in the enhanced arm, which were by design not included in the core arm.

Forms of enhanced agency

Across all participant types, some study participants described benefitting from the intervention, although many of the adolescents mentioned that they had forgotten what they had learned, as considerable time had passed since the end of the programme. Some participants in each arm mentioned having forgotten everything, or quite a lot, but most participants could recall key topics of discussion, activities they had engaged in, and skills they had learned, and in several cases, described how they or their families had put this knowledge into practice.

Knowledge. By far, the most often described change attributed to the Tipping Point (core or enhanced) Program was enhanced knowledge of a range of topics. While study participants rarely described TPP as the only source of information, for example, also learning content from school, family, friends and other programmes, TPP was identified as an important source of information. Among adolescent boys and girls in core and enhanced study arms, child marriage and the health impacts of early childbearing were the most common areas of enhanced knowledge and most frequently recalled topics (). Girls’ recollection in general was more expansive than that of boys. The health impacts of childbearing were mentioned mostly as a reason to delay marriage.

Girls below 20 are still small and can’t work properly. If they get pregnant, that too will be a problem because their uterus still hasn’t developed properly. All the body organs develop properly after crossing 20 so one should get married only after 20 years of age. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, core TPP)

Table 3. Content recalled, ranked by frequency, by gender, qualitative evaluation of the tipping point programme in Nepal.

Parents who were interviewed seldom directly referenced specific content personally learned and mostly mentioned TPP content regarding their child’s participation, likely reflective of their lower level of participation compared to that of their children. The most common topics mentioned by parents were child marriage, self-confidence, the importance of girls’ education, and equality of boys and girls labour in support of the household. There were no differences in the frequency of content discussed across gender or arm among parents, but parents of non-participants mentioned TPP content the least, as would be expected. While the parents of adolescents who were not enrolled at baseline were not expected to have knowledge or experience with the programme, some participants’ narratives suggested that at least some of those adolescents ultimately were enrolled in the programming.

Behavioural Change. Although much less frequently mentioned, some participants described that knowledge had been put into action by adolescents or parents instituting changes in the household because of TPP, reflected among those who recalled much greater participation. Most participants mentioned sharing their learning with family members, friends and neighbours. For example, a few boys and girls mentioned having shared information about how to make pads, which was well received by mothers and sisters and was especially useful during COVID lockdown. Some girls described advocating with their parents for a more equitable division of labour in their households, which was reported to have changed from baseline. While changes to the division of labour were generally perceived to be modest, i.e. brothers sometimes helping their sisters or mothers with the household work, or parents assuming housework to allow the adolescents more time to study, these actions were recognised by some parents as noteworthy, given the strong prevailing norm of women and girls completing all household chores. While major transformations in the division of labour did not occur, according to participant narratives, many participants did describe a more cooperative approach to work in the family.

Several adolescents, and some parents and community stakeholders, mentioned that the adolescents gained confidence in expressing themselves from their participation in TPP, especially among participants from Rupandehi.

We used to play and talk. We even learned to make pads. We learned about good touch and bad touch and not differentiating between boys and girls. We used to talk about ourselves. We used to talk about menstruation. We had even conducted a rally. I mentioned about it earlier. … I used to get scared to talk to my family members, but I can freely talk to them now. I am not scared to talk anymore … I used to think that I will get married after studying till a certain grade but now I have realized that I need to get married after 20 years of age. I have understood that I shouldn’t get married at a younger age. (Adolescent girl, Kapilvastu, enhanced TPP)

There have been some changes. I think it’s because of the programs that you ran on Saturdays. The girls learned to make pads. We had also called the mayor recently in another program where the girls could openly share their wants. “Aba mero palo” [Tipping Point] program has boosted the confidence in these girls. They were able to demand for pads in front of the mayor. The girls had also gone out and made flags. I liked the program. P3: We loved the program. Both girls and boys had walked around the village with flags. (Mother, Kapilvastu, enhanced TPP)

A girl in our community was being married off by her grandfather. At that time, our group went there and reminded him that she isn’t old enough to marry, to let her study and marrying at a young age is unhealthy both physically and mentally. It also has impact on one’s health and will make childbirth more difficult. The newborn baby will be disabled and the mother’s life will be in danger. After saying this, her marriage was called off and the girl is currently studying. This incident happened within the last two years. I did this work will all the girls of the group. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, core TPP)

There have been many programs in our village related to violence against women, child marriage, non-discrimination against sons and daughters and these programs have also conducted various awareness programs. People have changed by watching and listening to seminars, street plays and speech programs conducted by these programs. ‘Aba Mero Palo’ and other various programs before that has come in our village. (Adolescent Girl, Rupandehi, core TPP)

Characteristics of participants reporting multiple notable changes attributed to TPP

Among the adolescents who were interviewed, five participants (4 girls and 1 boy) had notably positive changes to their knowledge or behaviours at endline. These adolescents were from Kapilvastu and Rupandehi districts, either Muslim or Hindu, and had several similarities. All five of these adolescents were generally older, with an average age of 17 at endline. As such, all participants were teenaged when the baseline intervention began. Additionally, all five participants were attending or enrolled in school at the time of the interviews. No adolescent from this sample was married or had undergone guana and all desired from baseline to marry after the age of 20. When compared to baseline, the desired age for marriage either stayed the same or increased for these participants. Further, the boy in this sample preferred to have a love marriage rather than an arranged marriage which has also changed from baseline. Importantly, all five participants seemed at baseline to have relatively strong relationships with their parents. They were communicative with their parents and shared their desired marriage age, education preferences and future aspirations. In most cases, adolescent study participants described receiving support and agreement from their parents on these choices and anticipated plans. All five study participants aspired to pursue professional careers out of the home, such as a lab technician, nurse, or doctor.

My father says that I should be doing something and not stay at house ideally. My father says do good in whatever field you want but don’t sit at home doing nothing. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, core TPP)

I want to be a nurse. I have already told my parents that I want to be a nurse. They were happy. They have asked me to study well and be a good nurse. They have told me that they will let me study whatever I want. (Adolescent girl, Rupandehi, enhanced TPP)

Interestingly, several characteristics differed among these five participants. Parental education for adolescents from this sample ranged from no schooling to having a Bachelor’s degree. While many mothers were housewives, paternal occupations and fields were different across all participants. Participants were from different castes and religions including Teli, Terai, Kurmi, Tharu and Khatun. Additionally, there was not a majority of participants from one study arm. Notably, all the girls in this sample still had relatively restricted mobility, which did not expand appreciably for most girls in the entire sample, and these girls remained responsible for most of the household chores as noted above. The case study below exemplifies the characteristics of participants who described benefitting from the programme.

Case study of adolescent girl reporting substantial benefit from TPP

Adolescent girl, age 15, grade 8, Rupandehi, core TPP: The participant seemed to have strong participation in the programme sessions and wanted the programme to expand to other villages to increase knowledge elsewhere. When TPP was suspended due to COVID-19, this participant was proactive and called the session’s group leader to attempt to reschedule some remaining activities. While the participant shared her learnings and knowledge with family and friends, it was not clear if anyone changed as a result of her learnings. The participant, however, clearly gained voice, leadership and knowledge from participating.

We should not hide anything, we should not fear anyone, we should directly say our things at people’s face. We should not discriminate anyone (based on caste). We should not fight; we should live together in harmony with all. We should spread good message to all. First of all, we should say these things at our home. When people from our family learn, villagers will also learn. These things will bring development in the country.

I didn’t have any goals earlier. I was aimless, like a small child who doesn’t know anything about his/her future goal. My father asked me this year, what do I want to be. I told him staff nurse.

Characteristics of married adolescent participants or those having their marriages fixed

Among the sample of adolescent girls and boys, marriage was relatively rare (overall sample <4%). Two girls, one each from Kapilvastu and Rupandehi were married by endline. One participant in Rupandehi also detailed that her friend in the group had been married, although her friend was not among the adolescents who had been interviewed for the study. In Kapilvastu, two girls, while not married, had had their marriages ‘fixed’ and one additional girl was at high risk as she was already 18, not studying, and her parents had decided that it was time for her to get married. No boys in the sample were married at endline or had their marriages ‘fixed.’

The girls in the sample who were married or who had their marriages fixed shared several common characteristics. Most were from Kapilvastu, a location with a much greater concentration of Muslim families, characterised by the participants as having very restrictive gender norms. All the girls experiencing marriage or having their marriages fixed in Kapilvastu were Muslim; however, direct comparison to other religions or castes is not possible given the predominance of Muslims in the Kapilvastu qualitative sample. Regardless of location, all the girls lived in families that did not value education for girls, a feature that was noted as being against the norms among the Kapilvastu participants. None of the girls were in school despite wishing to be, none had exceeded a primary school education, with education levels ranging from illiterate to the 6th grade, and all but one came from a family with very little education, including among siblings.

I have told my father that I want to study further but he tells me that the villagers here won’t like it if he sends me outside or to the school. Therefore, he tells me to leave it. (Adolescent girl, Kapilvastu, enhanced TPP)

Case study of girl married during the study

Adolescent girl, 18, illiterate, Kapilvastu, core TPP: This adolescent participated in the project and demonstrated increased voice and knowledge, especially in division of labour, marriage age and education. As she was pulled from school at an early age due to financial constraints, the intervention was a major source of information for this participant. The participant was married at 18 but believes girls should marry around age 21–25, after they have been educated, and acknowledges that she is the only girl in her village to have been married at 18 recently, as the community’s typical age for marriage is around 23 years. Her father also attended group sessions and is now more open to changes, while her mother, who did not participate, is still drawn to traditional ways.

My father says that old practices should not be followed, and everyone should do household chores. He also says that if someone teaches new things then we should learn them … My father used to attend this training and it is the reason behind change in him.

Everyone in the community should unite and talk with that kind of boys (bad boys) and convince them not to tease. Complain at ward. But there is no one like that in our community.

Discussion

This longitudinal qualitative study provides an in-depth examination of a well-designed intervention, tested in a rigorous mixed-methods c-RCT, that at the study population-level did not demonstrate effectiveness at decreasing child marriage (Yount et al., Citation2023). This study adds insight relevant for research and programming about the perceived benefits of the programme to norms change, girls’ agency, the characteristics of participants who described benefits beyond knowledge gain, and the disconnect between needs and programmatic offerings among those most vulnerable to CEFM. Overall, study findings support the emerging literature on the importance of understanding the influence of participant characteristics and the contexts that influence the effectiveness of CEFM interventions.

The role of TPP in norms change

TPP, like numerous other development initiatives, had to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in part by suspending activities for five months and reducing the planned number of activities, including those at the community level. Those who participated in these community-based activities felt that the activities were beneficial to their communities; however, the predominant narrative around norms change was to reference pre-existing and ongoing social changes in increasing age at marriage, greater consultation, if not decision-making, among adolescents in the marriage process leading to a slight shift in expectations among some adolescents and their families that girls should seek education and employment before marriage.

These shifts, while not equally strong across localities or families, were most consistently attributed to improved educational levels among community members with particular attention to increases in girls’ enrolment and the growing social and financial value of education for girls. The consistent attribution of change to educational improvements, particularly among girls, is in alignment with substantial increases in girls’ enrolment and generational differences in educational attainment for men and women. Attributions of change also are aligned with global evidence that education is among the most cost-effective development strategies and a consistent protective factor against CEFM (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021b; Wodon et al., Citation2017).

Study findings also point to the role of development programming in a dynamic landscape. As a low-income country that has just moved from least development status, Nepal remains dependent on donor funding in part to deliver core governance functions. The sheer number of development actors, however, means that different programmes on similar topics may overlap in locality, time and target group, making the attribution of programme effects among the qualitative study participants in the context of a c-RCT difficult.

Agency and challenges to participation

While norms change cannot be attributed uniquely to TPP, some study participants reported perceived benefit. New or enhanced knowledge was the most frequently reported benefit of the programme, which most adolescents and some parents in the qualitative sample recalled. Knowledge is a foundational asset, and TPP seemed to fill certain knowledge gaps, such as gaps in information about sexual and reproductive health, that were missing or only scantly provided in schools and normatively not the subject of conversation with parents. This narrative corroborates findings in the quantitative impact assessment, in which enhanced sexual and reproductive health knowledge was one of two secondary outcomes significantly impacted by the TPP + package (Yount et al., Citation2023). The other was group membership in social or cultural organisation club or association. Other agency-related characteristics, such as confidence and voice, enhanced communication and negotiation with parents, and skills like pad making were also noted among adolescents and some parents, with some reports that these skills had been used.

However, the application of knowledge or utilisation of a skill set was infrequently mentioned across the participant sample, due in large part to differences in degree of participation, which ranged from almost no participation to very frequent participation. While the quantitative analysis found little association at the population level between the extent of programme participation and secondary instrumental-agency outcomes (Yount et al., Citation2023), in the qualitative sample, more substantial benefits were attributed to the programme among those who reported greater participation with differences in findings potentially due in part to the purposive sample in the qualitative study and the probability-based sample in the quantitative study. Never-the-less, variable participation is in line with existing research about the challenges of engaging underserved participants in programming (Whitley et al., Citation2014). Men and women in rural Nepal spend approximately 45% of the day in productive work, whether paid or unpaid. When reproductive work (child and adult care, services for the household, household chores, travelling for household associated tasks) is added, the total for men is 53% and for women 62%, leaving little time, especially for women to participate (Picchioni et al., Citation2020). Adolescents in Nepal also have considerable responsibilities in these same domains, with a similar gender disparity. With the growing emphasis on education for boys and to some extent girls, school-going adolescents may also receive tutoring to pass standardised government exams or move to another locality to attend private boarding schools to overcome quality deficits in government schools, further limiting the time they have available to devote to development programming. While skills-building programming, such as TPP, may be appreciated by some families, it was not by others as noted in this study, and even when valued, must compete with productive and reproductive work and education.

Disconnect between needs and programmatic offerings among those most vulnerable to CEFM

Those adolescents who participated most consistently in the TPP and who reported benefiting beyond just knowledge shared several pre-programme characteristics. At baseline, they were older, communicated more with their parents, had aspirations for themselves outside of marriage that their parents supported, and reported parental expectations for educational attainment. All of these personal assets and aspects of agency are established aspects of positive youth development, girls’ empowerment, and protective factors against CEFM (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021b; Shek, Citation1999). While these participants reported benefit attributed to TPP, they already were at low risk of marriage before participation in the programme. On the other hand, the participants who underwent marriage or had their marriages ‘fixed’ during the study period were the opposite, characterised by poorer relationships with their parents, limited aspirations or support for a life outside of reproductive work, experience of adverse events, and financial insecurity. The extent of risk clustering among this most vulnerable participant subgroup seemed to set them on a trajectory to CEFM that the TPP could not have altered, despite the programme’s attention to normative root causes, engagement of norms bearers, and agency-enhancing programming. This study’s finding of a mismatch between need and programme benefit supports prior research identifying poverty, poor education and other structural barriers as key drivers to CEFM (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021b) and growing evidence on the effectiveness of CEFM interventions that offer tangible support for education, livelihoods training and accessible job markets as viable alternatives to early marriage (Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021a).

Strengths and limitations of this analysis

Findings presented here must be interpreted in light of strengths and limitations of the qualitative component of the study. Strengths of the study included the longitudinal design and strong retention of baseline study participants, allowing for within-person changes of time to be examined in depth. Study team members conducted the analysis blind to study arm until the structured comparisons, which included by arm, which necessitated unblinding. While the need to unblind for the comparisons could have introduced some bias, the extent of such bias is likely to be minimal as there were minimal differences across arms. Additionally, narratives from adolescents, parents and community stakeholders provided the opportunity to triangulate across the narratives of theoretically important groups for the programming as well as across the qualitative and the quantitative portions of the study. However, while the content of the qualitative guides was complementary across these stakeholder groups, it was not always directly comparable, complicating the process of triangulation. In addition, while a relatively large number of interviews and group discussions were held, there were few qualitative study participants of each type from each site, limiting comparisons across sites. Finally, the sizable number of secondary outcomes that were hypothesised to contribute to the prevention of CEFM in the quantitative component of the cRCT (Yount et al., Citation2021, Citation2023) led to interview guides that interrogated a breadth of topics at the expense of depth in each one. This made interrogation of the proposed theory of change impossible as saturation was not attainable for each type of agency examined in the quantitative portion of the trial. Investigators limited reporting to themes that reached saturation.

Implications for research and policy

In terms of research, in settings such as Nepal where multiple programmes are underway that overlap in scope, timing and geographic location, it is difficult to isolate the impact of one programme compared to others. Despite efforts initially to locate programming where no other relevant programming was underway, participants in this study had clearly participated in other programming, prior to and during TPP. The presence of other programming also was noted as a potential contributor to mostly null findings in the quantitative portion of this study (Yount et al., Citation2023). Since locating development programming and its evaluation is a process of negotiation with the federal and local governments, and organisations have no control over decisions about the approval and deployment of other programming over the timeframe of their activity, one approach to better ascertaining attribution would be to assess more thoroughly prior exposure at baseline as well as at endline so that such exposure can be accounted for in the interpretation of the qualitative findings.

The findings also suggest that instead of trying to parse out the unique benefit of any one programme, that research on the collective impact of programmes may better align with the lived experiences of individuals and the changing conditions of their communities since TPP and other programmes are filling gaps that other might otherwise remain given the number of simultaneous development challenges the government faces.

The programmatic challenge of identifying those most vulnerable to a particular health or social outcome is a consistent struggle. The sites for TPP were chosen as being disadvantaged with a large population of at risk girls. However, the differences that emerged during this study across districts and among sub-communities in the same locality suggests that resources were addressing general needs, not the multifaceted needs of those at greatest risk. Highly targeted, community-engaged formative research would be needed to identify the sub-communities and families at greatest risk or marrying their daughter early and to tailor programming to the complex needs of these individuals and sub contexts.

Maintaining strong and consistent participation across stakeholders is another common programmatic challenge. Given the growing expectation of education for both boys and girls, integrating programmes into the school curriculum might reduce some of the perceived or actual competition the programme has with other activities. Providing job-related skills or pairing with income generating activities may enhance the value of the programme to parents, reinforce the growing expectation among many parents that their daughters working before marriage, and address the risk of CEFM due to poverty.

In terms of policy, the government's efforts to improve the educational status of its population and get girls into the classroom have paid off in terms of norms change and altering the value of girls’ education. Continued emphasis in this area is needed to ensure high quality accessible education for all. Concomitantly, continued effort to develop markets and quality job opportunities will bolster expectations and perceived and actual benefits of girls working before marriage. Targeted governmental financial support, skill building, and attitudinal and norms change are needed among the sub-population of families whose attitudes and circumstances place girls at highest risk of CEFM.

Conclusions

Despite a thoughtful step-by-step approach to intervention development in Nepal, the TPP failed to address the structural barriers and clustering of risk among those most vulnerable to CEFM, highlighting the complexity of intervening on CEFM. Longitudinal narratives of adolescents showed either enduring risk or protection from early marriage and set the stage for the degree of participation and perceived benefit from TPP that adolescents, their families, and their communities could experience. Study findings support growing calls for better alignment of programming to the needs of those most vulnerable, especially the importance of addressing structural challenges including poverty and poor educational attainment as essential steps toward accelerating the decline in CEFM in Nepal and attainment of SDG 5.3.

Trial registration number

NCT04015856.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bergenfeld, I., Clark, C., Kalra, S., Khan, Z., Laterra, A., Morrow, G., Sharma, S., Sprinkel, A., Stefanik, L., & Yount, K. (2019). Tipping Point Program Impact Evaluation: Baseline study findings in Nepal. Atlanta, Emory University, CARE USA.

- Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2020). Nepal multiple indicator cluster survey 2019: Survey findings report. Central Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF Nepal.

- Chae, S., & Ngo, T. (2017). The global state of evidence on interventions to prevent child marriage. Girl Center Research Brief No. 1. New York, Population Council.

- Cislaghi, B., Mackie, G., Nkwi, P., & Shakya, H. (2019). Social norms and child marriage in Cameroon: An application of the theory of normative spectrum. Global Public Health, 14(10), 1479–1494.

- Kalamar, A. M., Lee-Rife, S., & Hindin, M. J. (2016). Interventions to prevent child marriage among young people in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the published and gray literature. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3), S16–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.015

- Karim, N., Greene, M., & Picard, M. (2016). The cultural context of child marriage in Nepal and Bangladesh: Findings from CARE’s tipping point project community participatory analysis. CARE.

- Lee-Rife, S., Malhotra, A., Warner, A., & Glinski, A. M. (2012). What works to prevent child marriage: A review of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning, 43(4), 287–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00327.x

- MacQuarrie, K. L., & Juan, C. (2019). Trends and factors associated with child marriage in four Asian countries. Gates Open Research, 3(1467), 1467. https://doi.org/10.12688/gatesopenres.13021.1

- Makino, M., Ngo, T. D., Psaki, S., Amin, S., & Austrian, K. (2021). Heterogeneous impacts of interventions aiming to delay girls’ marriage and pregnancy across girls’ backgrounds and social contexts. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6), S39–S45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.016

- Malhotra, A., & Elnakib, S. (2021a). 20 years of the evidence base on what works to prevent child marriage: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 847–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.11.017

- Malhotra, A., & Elnakib, S. (2021b). Evolution in the evidence base on child marriage 2000-2019. New York, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Global Program to End Child Marriage.

- McDougal, L., Shakya, H., Dehingia, N., Lapsansky, C., Conrad, D., Bhan, N., Singh, A., McDougal, T. L., & Raj, A. (2020). Mapping the patchwork: Exploring the subnational heterogeneity of child marriage in India. SSM-Population Health, 12(12), 100688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100688.

- Morrow, G., Yount, K. M., Bergenfeld, I., Laterra, A., Kalra, S., Khan, Z., & Clark, C. J. (2022). Adolescent boys’ and girls’ perspectives on social norms surrounding child marriage in Nepal. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 25(10), 1277–1294.

- Muthengi, E., Olum, R., & Chandra-Mouli, V. (2021). Context matters—One size does not fit all when designing interventions to prevent child marriage. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6), S1–S3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.018

- Owusu-Addo, E., Renzaho, A. M., & Smith, B. J. (2018). The impact of cash transfers on social determinants of health and health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 33(5), 675–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy020

- Parvin, K., Talukder, A., Mamun, M. A., Kalra, S., Laterra, A., Naved, R. T., & team, T. P. I. s. (2022). A cluster randomized controlled trial for measuring the impact of a social norm intervention addressing child marriage in Pirgacha in Rangpur district of Bangladesh: Study protocol for evaluation of the tipping point initiative. Global Health Action, 15(1), 2057644. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2057644

- Petroni, S., Steinhaus, M., Fenn, N. S., Stoebenau, K., & Gregowski, A. (2017). New findings on child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of Global Health, 83(5-6), 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2017.09.001

- Picchioni, F., Zanello, G., Srinivasan, C., Wyatt, A. J., & Webb, P. (2020). Gender, time-use, and energy expenditures in rural communities in India and Nepal. World Development, 136, 105137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105137

- Psaki, S. R., Melnikas, A. J., Haque, E., Saul, G., Misunas, C., Patel, S. K., Ngo, T., & Amin, S. (2021). What are the drivers of child marriage? A conceptual framework to guide policies and programs. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6), S13–S22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.001

- Shek, D. T. (1999). Parenting characteristics and adolescent psychological well-being: A longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 125(1), 27–44.

- Stefanik, L., & Hwang, T. (2017). Applying theory to practice: CARE’s journey piloting social norms measures for gender programming. Atlanta, GA, Care USA.

- United Nations Children's Fund. (2018). Child marriage: Latest trends and future prospects. UNICEF.

- Whitley, M. A., Forneris, T., & Barker, B. (2014). The reality of evaluating community-based sport and physical activity programs to enhance the development of underserved youth: Challenges and potential strategies. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ), 66(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2013.872043

- Wodon, Q., Male, C., Nayihouba, A., Onagoruwa, A., Savadogo, A., Yedan, A., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., John, N., Murithi, L., Steinhaus, M., & Petroni, S. (2017). Economic impacts of child marriage: Global synthesis report. The World Bank and International Center for Research on Women.

- Yount, K. M., Clark, C. J., Bergenfeld, I., Khan, Z., Cheong, Y. F., Kalra, S., Sharma, S., Ghimire, S., Naved, R. T., & Parvin, K. (2021). Impact evaluation of the care tipping point initiative in Nepal: Study protocol for a mixed-methods cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 11(7), e042032. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042032

- Yount, K. M., Durr, R. L., Bergenfeld, I., Sharma, S., Clark, C. J., Laterra, A., Kalra, S., Sprinkel, A., & Cheong, Y. F. (2023). Impact of the CARE tipping point program in Nepal on adolescent girls’ agency and risk of child, early, or forced marriage: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. SSM-Population Health, 22, 101407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101407

- Yount, K. M., Krause, K. H., & Miedema, S. S. (2017). Preventing gender-based violence victimization in adolescent girls in lower-income countries: Systematic review of reviews. Social Science & Medicine, 192, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.038