ABSTRACT

Cervical cancer is a significant public health concern globally, with low and middle-income countries bearing the highest burden, specifically the South Asian region. Therefore, the current scoping review aimed to highlight the factors influencing the implementation of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in South Asia. Adopting the ‘Arksey and O'Malley and Levac et al.’ methodology, multiple electronic databases were searched to identify relevant records. The results were narratively synthesised and discussed, adopting the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) model. We identified 527 records, which were assessed for eligibility based on title, abstract, and full text by three reviewers, followed by data extraction of 29 studies included for analysis in the review. Implementing HPV vaccination programs in South Asia faces various challenges, such as economic, health system, financial, health literacy, and sociocultural factors that hinder their successful implementation. To successfully implement the vaccine, a tailored risk communication strategy is necessary for these countries. Knowledge gained from the experience of South Asian nations in implementing the HPV vaccine can assist in policymaking in similar healthcare for advancing the implementation of HPV vaccination.

Introduction

Globally, cervical cancer is a considerable burden, causing premature death and disability. The GLOBOCAN Report 2020 highlights an increasing trend in cervical cancer incidence, 604,127 worldwide and 341,831 deaths (GLOBOCAN, Citation2020). The Asia-Oceania region accounts for more than 50% of cervical cancer cases, with Southeast and South-central Asia having the highest burden (Arbyn et al., Citation2020; Garland et al., Citation2012). Approximately 90% of cervical cancers occur in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) that lack organised screening and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programs (Shet & Bar-Zeev, Citation2023).

In response to this urgent public health issue, the World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed the triple-intervention strategy, emphasizing the expansion of HPV vaccination, screening, and treatment interventions (World Health Organisation, Citation2020). This approach applies to South Asian nations, as most are classified as LMIC (The world bank, Citation2023a).

Supplementing this, the WHO guides HPV vaccine integration into national immunization programs; however, South Asian countries face inadequate coverage (World Health Organization, Citation2014, Citation2016a). Successful incorporation occurred in Bhutan in 2010, the Maldives in 2019, and Sri Lanka in 2017, achieving vaccination rates of 74%, 50%, and 41% among females, respectively (Hingmire et al., Citation2023; PATH, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2022a), While India initiated vaccination as a demonstration project in 2009, with subsequent efforts in Delhi in 2016 , Punjab in 2017, and Sikkim in 2018, endeavouring to achieve large-scale execution (Burki, Citation2023; Sankaranarayanan et al., Citation2019). Bangladesh started a scaled program in 2016 and intends to implement routine inclusion by 2023 (PATH, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2016b). Nepal conducted a feasibility study in 2006, introduced a demonstration project in 2016, and plans routine inclusion by 2023 (PATH, Citation2022; World Health Organization, Citation2016c). However, Pakistan and Afghanistan lack vaccination programs (Annexure 1 of the Online Appendix) (Awan et al., Citation2023; Burney & Zafar, Citation2023). Inadequate vaccine implementation in these regions stems from sociocultural, health system, and political influences (Wigle et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, ethical concerns, including alleged human rights violations and rule breaches, arose during vaccine trial projects in India, leading to project suspensions (Sankaranarayanan et al., Citation2019; Sharma, Citation2013). Additionally, claims of deaths and safety concerns fueled post-vaccination a contentious debate (Sankaranarayanan et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it is essential to conduct a thorough examination of the factors that influence the implementation of HPV vaccination in these nations.

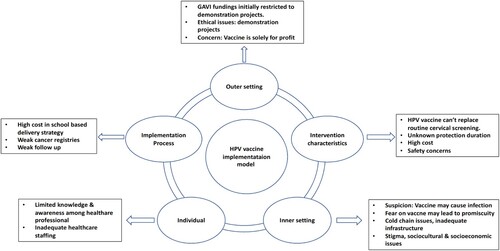

To understand these challenges, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) model is adopted (Damschroder et al., Citation2009). CFIR, with its five domains, offers a comprehensive analysis: 1. Intervention characteristics: Examining the nature, complexity, adaptability, evidence base, and relative advantage of the intervention. 2. Outer setting: Encompassing external factors like social, political, and economic context and the influence of external stakeholders. 3. Inner setting: Considering factors within the implementing organization, such as culture, leadership, and resources. 4. Individuals: Focusing on characteristics of those involved, including knowledge, skills, attitudes, and motivation. 5. Implementation process: Concentrating on specific strategies for planning, executing, and monitoring the intervention.

The CFIR model has found application in various health contexts, including mHealth solutions and school-wide sexual assault prevention programs (Ardito et al., Citation2023; Orchowski et al., Citation2023). Therefore, in this scoping review, we adopted the CFIR model to map the evidence on factors that influence the implementation of HPV vaccination in South Asia. Such an approach can provide a concise overview of the available evidence, enabling further research to formulate informed decisions and develop interventions to improve HPV vaccine implementation in South Asia.

Materials and methods

The scoping review was conducted by following the frameworks presented in ‘Arksey and O’Malley’ and ‘Levac et al.’ (Levac et al., Citation2010). To ensure the adequate coverage of necessary elements in reporting, the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)’ was adopted (Tricco et al., Citation2018), and its recommended items are included in Annexure 2 of the Online Appendix. The subsequent sections elaborate on the specific stages employed during this scoping review.

Stage 1: Identifying the review question

The review question was formulated after a thorough literature search and brainstorming.

What are the factors impacting HPV vaccination implementation in South Asia?

We adopted the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) format, according to the JBI manual for evidence synthesis 2020 (Peters et al., Citation2020), for developing the research question . While the primary emphasis of the study cohort lies in the examination of adolescents as recommended by the WHO (Kaur et al., Citation2017), it is imperative to incorporate additional essential stakeholders in evaluating human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the South Asian region. These stakeholders encompass healthcare professionals and parents/guardians who wield substantial influence over the implementation and acceptance of the vaccine. Accordingly, the study comprises investigations involving these pertinent stakeholders.

Table 1. PCC framework for developing the research question.

The South Asian region bears a significant burden of HPV-related diseases, particularly cervical cancer. Conducting an HPV vaccination study in South Asia is paramount in promoting regional collaboration and facilitating knowledge sharing among researchers, policymakers, and healthcare professionals. This endeavour can foster partnerships between countries, facilitate the exchange of best practices, and encourage joint efforts to address common challenges encountered in implementing HPV vaccination programs. Therefore, the present study to include South Asia aims to fulfil these objectives.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

The research question was divided into concepts, and relevant keywords were identified for each concept. The databases searched included PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Scopus, with a limited scope to English language articles only. An overview of the electronic search in the databases is provided in Annexure 3 of the Online Appendix. In addition to the database search, reference lists of included papers were screened to identify any potentially qualifying articles that may have been missed. The studies must have been conducted from 2006 to January 2023, as the HPV vaccine was first licensed in June 2006 (Cutts et al., Citation2007).

Stage 3: Study selection

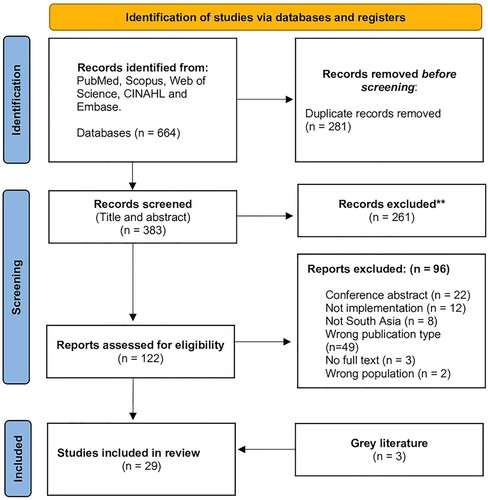

Retrieved papers’ titles and abstracts underwent screening by three reviewers, PR, SD, and DSP, assessing eligibility through pre-defined criteria on the Rayyan platform, a systematic review web-based management platform (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). In case of uncertainty, a fourth reader or independent opinion was sought. Full texts of eligible studies were retrieved after the initial screening and independently reviewed by the three reviewers. The included studies underwent data charting for the final scoping review, detailed in a flowchart following PRISMA 2020 diagram (Page et al., Citation2021). All studies meeting pre-defined criteria, irrespective of quality, were included (). This review encompasses a variety of research methods, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies. Furthermore, to ensure comprehensive coverage, the reference lists of the included papers were thoroughly evaluated to incorporate all relevant literature.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Stage 4: Charting the data

The data charting process was executed utilising a predetermined data charting format in Annexure 4 of the Online Appendix.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising, and reporting the results

The study employs a narrative synthesis, utilising tables to summarise characteristics and findings. A comprehensive list of South Asian countries and sources since June 2006 was compiled to identify relevant literature. Quantitative and qualitative data from the charting table were used to map and report on HPV vaccine implementation studies and influencing factors in South Asia. These findings, offering valuable evidence for countries with insufficient HPV vaccination coverage, are synthesised into a cohesive publication with scientific and clinical implications.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

In this study, a rigorous systematic search was executed, culminating in identifying 383 unique entries after removing 281 duplicates . These entries were then subjected to a thorough screening process based on the pre-defined eligibility criteria, ultimately including 29 studies, including 3 grey literature for the review and encompassing four countries, namely India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

In this review, 29 paper were included (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Ali et al., Citation2022; Basu & Mittal, Citation2011; Bhuiyan et al., Citation2018; Biellik et al., Citation2009; Bingham et al., Citation2009; Canon et al., Citation2017; Chellapandian et al., Citation2021; Holroyd et al., Citation2021; Jacob et al., Citation2010; Johnson et al., Citation2014; Kamath et al., Citation2021; Krupp et al., Citation2010; Kumari & Pankaj, Citation2021; Madhivanan et al., Citation2009, Citation2014; Mehta et al., Citation2013; Padmanabha et al., Citation2019; Pandey et al., Citation2012; Paul et al., Citation2014; Prinja et al., Citation2017; Priya & Kumar, Citation2023; Rao et al., Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2021; Shah et al., Citation2022; Shaikh et al., Citation2019; Shetty et al., Citation2021; Swarnapriya et al., Citation2015; Tsui et al., Citation2009). These papers were also organised in a separate numeric list called ‘References (List of papers included in the review)’ which is available in the Annexure 5 of the OnlineAppendix. In order to improve the readability of the results, from this point, these papers are mentioned using the numeric citation accordingly. Please access Annexure 5 for the details.

The investigations conducted in this study utilised a diverse range of research methodologies, including both qualitative and quantitative approaches and mixed-methods studies. The study focused solely on empirical research and included no commentaries, reviews, or conference abstracts. A comprehensive summary of each exploration is presented as a ‘Study characteristics table’ (Annexure 6 of the Online Appendix). The Study characteristics table is organised according to the author's name, study's title, study objective, study design, study origin, study population, and the findings, providing readers with a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the collective results. The presentation of these findings is carefully structured to facilitate a thorough and precise data comprehension.

Factors influencing implementation and uptake of HPV vaccines in South Asia

Several factors are found to have an impact on the implementation of HPV vaccination in South Asia. These include the vaccine's high cost, ethical concerns surrounding sexual health and the HPV vaccine, limited understanding regarding the vaccine among healthcare professionals and the guardians of the beneficiaries, and a range of sociocultural barriers. These factors are further elucidated in detail below.

India

The introduction of the HPV vaccine in India faces multiple challenges in the realm of intervention characteristics, notably the high cost, creating a financial burden on healthcare professionals, women, and parents, as indicated by seven studies conducted in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Chennai, Manipal, Mangalore, Mysore, and some parts of the South Indian region (7, 8, 10, 15, 19, 27, 28). Consequently, most individuals find the vaccine unaffordable unless it becomes part of India’s Universal Immunization Program schedule, as mentioned in a study conducted in Mysore (13). Additionally, women's concerns about vaccination potentially implying an existing HPV infection further hinder acceptance, as indicated by three studies in Bangalore, Mangalore and Uttar Pradesh (9, 23, 25). Additionally, the requirement of a three-dose schedule for the HPV vaccine has posed a significant obstacle to its delivery and acceptance by incurring high costs, as indicated by a study in Patna (14).

Implementation of HPV vaccination faces multiple challenges in the context of the outer setting, with a prominent requirement of budget approval for the successful implementation of the vaccination program, as reported by a study in some parts of low-resource settings, including India (29). Another study in Mysore highlights that the lack of a program protocol or endorsement by authoritative bodies makes physicians hesitant to recommend the vaccine. Physicians emphasise that unless the vaccine is available in government settings or endorsed by the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) Committee on Immunization, they are reluctant to recommend it (10).

Multiple sociocultural beliefs impact HPV vaccination in the inner setting, with misconceptions about safety and efficacy prevailing among healthcare professionals. These findings are reported by six studies conducted in some parts of low-resource settings, including India, and in other locations such as Chennai, Manipal, Mangalore, and various areas in South India (7, 8, 18, 19, 28, 29). Furthermore, such misconception and vaccine apprehension have been conveyed by women, parents, and community members, as reported by five studies conducted in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Mangalore, Mysore, Uttar Pradesh, Kolkata, and some parts of low-resource settings, including India (3, 6, 10, 16, 25). This misconception has potentially resulted in hesitancy towards HPV vaccination, attributed to a lack of comprehensive knowledge on the subject. Also, numerous women have expressed a desire for further research to foster a greater acceptance of this vaccine, particularly regarding the potential side effects and overall efficacy. This sentiment was demonstrated by a study in Mangalore (25). However, it is worth noting that married women of advanced age who possess a college education and have one or more children were more inclined to accept the HPV vaccine for their children. This was revealed by a study conducted in Mangalore (24).

Additionally, some sociocultural beliefs include an association of sexual promiscuity, as reported by three studies in Mangalore and Delhi (17, 18, 27), and familial restrictions due to father’s role as decision-makers, as reported by a study in some parts of low resource settings (6). It may be because parents do not acknowledge that their daughters would engage in sexual activity, hindering vaccine acceptance, as reported by two studies in Mysore (13, 15). Furthermore, perceptions like the notion that a regular menstrual cycle eliminates the need for HPV vaccination (6), and the perceived low risk of contracting cervical cancer (25, 28), also influence implementation, as reported by three studies in Bangalore, Mangalore, and some parts of South India.

A range of favourable factors support the implementation of the HPV vaccination, including parents’ positive attitudes toward vaccination benefits, as stated in three studies conducted in Mysore, Patna, and Andhra Pradesh (14, 15, 20). Additionally, cost-effectiveness has been identified as another favourable factor in implementing the HPV vaccination in Punjab, thereby underscoring the potential for successful implementation (21).

Several factors impede the implementation of the HPV vaccine in India within the domain of individual characteristics, including limited understanding regarding the vaccine among healthcare professionals, highlighted in seven studies across Delhi, Mangalore, Mysore, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chennai, and other parts of low-resource settings, including India (5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 17, 18). Also, most physicians discuss sexual health only if initiated by patients or for specific concerns, as noted in a Mysore study (13). Despite these hindering factors, there are also positive aspects. Three studies in some parts of South India, Delhi, and Mangalore show that despite insufficient knowledge, medical students exhibit a positive attitude towards HPV vaccine implementation (17, 22, 27).

In the domain of the implementation process, various factors influence HPV vaccination implementation. In contrast, the school health system’s success in Sikkim is noted (1). Nonetheless, policymakers highlight challenges in integrating HPV vaccination into schools. It is due to concerns that include perceived risks of inadequate adverse event management due to perceived gaps between the school and health systems, as reported by a study in some parts of low-resource settings, including India (29). Additionally, a study in some low-recourse settings emphasises the need for human resources for cold chain and logistics management if the HPV vaccine is introduced (5).

Nepal

A study conducted in two Nepalese communities, Khokana and Sanphebagar, has illuminated numerous concerns about HPV vaccination, particularly within intervention characteristics and inner settings. These concerns include the prohibitively high vaccine cost and the limited knowledge and awareness among the population regarding HPV vaccination. Despite a constrained understanding, women have expressed a readiness to have their children vaccinated against HPV, mainly if the vaccine is provided free of charge. Additionally, the influence of fathers in decision-making regarding vaccinating their daughters against HPV has been documented (11). Consequently, factors within these domains impact HPV vaccination efforts in Nepal.

Pakistan

In inner settings, diverse factors play a pivotal role in influencing the execution of HPV vaccination. Notably, a substantial concern identified in the Sindh region (2), revolves around insufficient knowledge regarding HPV vaccination among adolescent girls, parents, and community members. Furthermore, a study in Karachi reveals that misconceptions and misinformation about the vaccine exacerbate implementation challenges (26). This, in turn, contributes to vaccine hesitancy, driven by fears of adverse effects such as scar formation at the injection site, the influence of fathers in decision-making, and general concerns about potential drawbacks.

Moreover, paternal involvement in decision-making processes, highlighted by a study in the Sindh region, is identified as another critical factor impacting the adoption of HPV vaccination (2). Nonetheless, studies suggest that augmenting awareness can improve vaccination acceptance, thereby facilitating the implementation of HPV vaccination in Karachi, as evidenced by findings from (26).

Bangladesh

In one study in the specific setting of Dhaka, Bangladesh, inner-setting characteristics have been observed to influence the attainment of acceptance. Women in professional occupations and residing in urban areas have expressed concerns about the HPV vaccine. They highlight perceived risks of unfavourable consequences and potential infertility attributed to the vaccine as noteworthy determinants (4). These concerns ultimately lead to a lower adoption rate of the vaccine.

Discussion

Implementing HPV vaccination programs in South Asia has faced numerous challenges due to several factors. In this examination, a compilation of 29 studies is utilised to identify the factors that influence the implementation of the HPV vaccination in South Asia, employing the CFIR model as a framework (Damschroder et al., Citation2009) ().

Figure 2. Adopted CFIR domains, constructs, and subconstructs of the HPV vaccine implementation model, CFIR, Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

In summary, successfully implementing the HPV vaccine requires careful consideration of intervention characteristics such as vaccine efficacy, safety, and affordability. These factors include vaccine efficacy, safety, and affordability, which are crucial for successful vaccination efforts. Furthermore, given the ongoing disease of a stigmatised disease, these factors remain critical for effective intervention. In contrast, there is an ongoing debate about including the HPV vaccine in vaccination programs, mainly because it cannot replace routine cervical cancer screening alone (Jindal et al., Citation2017). However, the low uptake of cervical cancer screening in South Asian countries underscores the need for alternative preventive measures (Annexure 7 of the Online Appendix). In this context, the HPV vaccine emerges as a primary strategy for preventing the disease, aligning with the WHO's Triple Intervention strategy for cervical cancer elimination by 2030, thus justifying its adoption (World Health Organization, Citation2020). However, it is essential to note that this paper does not intend to advocate for any particular interventional approach to address these factors.

The affordability of the HPV vaccine is another important factor impacting its implementation. However, the HPV vaccine, developed in India, has been launched at an affordable cost of 200–400 INR per dose, substantially lower than the GAVI (Burki, Citation2023; Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, Citation2023). This low-cost vaccine is expected to support the implementation of HPV vaccination programs in resource-limited countries. Furthermore, developing the domestically produced vaccine, particularly in India, may instil a sense of national pride and promote greater acceptance among the population, as was seen with the COVID-19 vaccine (UNICEF, Citation2021). This messaging positioned India as a global leader in the fight against COVID-19 and motivated Indians to participate in the effort by receiving the vaccine. Thus, a similar approach could be employed to launch HPV vaccination programs in South Asia, especially in India. Also, the implementation can be further boosted by the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) launched in 2015, which aims to provide quality health services without financial hardship (World Health Organization, Citation2022c). Additionally, countries such as Bhutan, Nepal, and India, which initially employed a three-dose regimen, have now transitioned to a two-dose regimen (Appendix 1 of the Online Annexure) (Ahmed et al., Citation2021; Hingmire et al., Citation2023; Sankaranarayanan et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2010). This shift, aligned with WHO recommendations, coupled with the availability of UHC, has the potential to enhance the accessibility of HPV vaccination programs in South Asia, particularly with the endorsement of transitioning to a one or two-dose vaccination regimen by WHO.

Moreover, concerns over funding, policy support, and infrastructure in the outer setting are pivotal in HPV vaccine implementation. Prior research has documented that a favourable implementation environment in resource-limited countries is strongly associated with the availability of healthcare resources and infrastructure (Van Boekholt et al., Citation2019). Funding challenges persist despite substantial support from GAVI, impeding HPV vaccine implementation in South Asian countries. Moreover, countries within the region may obtain supplementary financial assistance from alternative origins to sustain the undertaking’s operations (Hanson et al., Citation2015). In particular, external resources allocated to health in South Asian countries amounted to only 2.3% of the total health expenditure in 2010, compared to 10.5% in Sub-Saharan Africa (Mooketsane & Phirinyane, Citation2015). The funding gap significantly affects vaccine implementation in South Asian countries, particularly in India, where health expenditure is low (Rebecchi et al., Citation2016). This disparity may be resolved with the recent launch of an Indian-developed HPV vaccine (Burki, Citation2023). It allows nations to negotiate between the Serum Institute of India and the GAVI (Burki, Citation2023; Mahumud et al., Citation2020). Such negotiations could potentially lead to further reductions in vaccine prices and provide support for the successful implementation of the vaccine program in the region.

The inner setting highlighted factors such as organisational culture, suspicion of the vaccine, and weak health infrastructure as essential considerations for successful implementation. Sociocultural and economic variables influence vaccine adoption. Historical evidence indicates that cultural, economic, and educational factors significantly impact health technology acceptance (Ammenwerth, Citation2019). Consequently, developing context-specific social mobilisation strategies considering these factors is essential (Olaleye, Citation2019). People were also seeking credible information regarding the vaccine’s efficacy, safety concerns, and stigmatisation-driven factors impacting its uptake. Similar patterns have been observed in stigmatised diseases such as monkeypox (mpox) (Núñez & Valdés-Ferrer, Citation2023; Rajkhowa et al., Citation2023). By addressing these highlighted vaccination concerns, a utilisation of diverse risk communication approaches analogous to those employed in the context of monkeypox may enhance the uptake of HPV vaccination (World Health Organization, Citation2022b). The insufficiency of cold chain infrastructure in certain countries also represents an additional obstacle to the successful deployment of vaccines. Still, anecdotal reports suggest expansion, especially in response to the COVID-19 impact in South Asian countries, including India (The Economic Times, Citation2021). Moreover, digital platforms such as the eVIN (Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network) platform have been utilised for vaccination efforts in India, indicating that they may be suitable for HPV vaccination programs to facilitate data transparency and accountability (Saxena, Citation2022).

In the realm of individual characteristics, the implementation of HPV vaccination is significantly influenced by the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of healthcare providers and parents/guardians (Meyer, Citation2015). Active involvement of healthcare professionals is crucial, yet barriers such as inadequate knowledge persist in the region. Similar concerns have been reported in studies conducted in different healthcare contexts, highlighting that increasing awareness among healthcare providers is vital to achieving vaccination goals (Reddy et al., Citation2020). Therefore, there is a pressing need to implement vaccine communication strategies that increase awareness and promote the adoption of HPV vaccination. For that, steps highlighted by the WHO can be adopted (UNICEF, Citation2021). In South Asian countries, insufficiencies in healthcare staffing, limited healthcare infrastructure, and inadequate distribution of healthcare workers have been identified as prominent contributing factors to the diminished prevalence of unmet healthcare needs (Thammatacharee et al., Citation2012).

In conclusion, in the domain of the implementation process, success relies on planning, training, and monitoring. Evidence suggests that training and continuing education courses are recommended for health professionals to effectively recommend and administer the HPV vaccine (Guadiana et al., Citation2021). Despite the success of the school-based model, low student enrollment in South Asian countries like Bangladesh requires tailored strategies, such as stagiaires, to strengthen school health programs and increase student participation (The world bank, Citation2016).

The nuanced exploration of variables influencing HPV vaccination has practical implications, particularly in South Asia. Addressing implementation obstacles is crucial for effective solutions, with tailored strategies needed for India’s sociocultural influences, Nepal and Pakistan’s awareness concerns, and Bangladesh’s vaccination issues. Therefore, policymakers in these countries should foster regional collaboration and facilitate the exchange of knowledge among researchers, policymakers, and healthcare professionals to ensure the successful implementation of the vaccine. Moreover, the favourable factors that enhance implementation should be leveraged to promote extensive adoption of HPV vaccination in the regions of South Asia. However, empowered local communities can collaborate to modify policies perpetuating healthcare stigmatisation (Tran et al., Citation2019). Effective stigma communication plans, inspired by successful HIV/AIDS strategies, are imperative to mitigate stigma (Pulerwitz et al., Citation2010).

Additionally, insights gained from the successful COVID-19 vaccination campaigns offer valuable lessons for supplementing HPV vaccination efforts in South Asia. Clear and accurate communication strategies, as highlighted in the context of COVID-19, can be applied to enhance public awareness and acceptance of HPV vaccination (Hong, Citation2023; UNICEF, Citation2021). The collaborative regional approach observed in COVID-19 initiatives can serve as a model for policymakers and healthcare professionals involved in HPV vaccination, fostering efficient knowledge exchange and tailored strategies (Monaco et al., Citation2021). This cross-application of lessons learned from COVID-19 to HPV vaccination in South Asia holds significant potential for optimising implementation and overcoming specific challenges outlined in the nuanced exploration of variables influencing HPV vaccination.

Strength and limitations

The present study demonstrates several strengths and limitations concerning identifying factors critical to implementing human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on a large scale in the South Asian region. The current investigation employs the CFIR model to identify factors that impact the implementation of a vaccination program on a broad scale, which is the first instance of this approach being applied to such a context. A thorough review of the primary literature reveals a substantial body of research conducted in India, highlighting diverse factors linked to the implementation of HPV vaccination. However, in countries such as Bhutan, Maldives, and Sri Lanka, there is a lack of research on HPV vaccination, necessitating further primary studies to identify and illustrate the factors that affect HPV vaccination programs. This research provides a basis for scholars to investigate HPV vaccination in these regions further.

Contributions

The study, conceived and designed by PR in collaboration with DSP and SMD, established the protocol and methodology. PR and DSP conducted the initial literature review, and all three researchers collaborated on data charting. PR performed data analysis and drafted the manuscript with input from DSP and SMD. HB and PN provided critical feedback during the review process. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (92.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The personnel of Prasanna School of Public Health, MAHE, express sincere appreciation for providing logistical support. It is important to note that this is a nonfunded study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data availability for this review study is based on publicly accessible and peer-reviewed sources.

References

- Ahmed, D., VanderEnde, K., Harvey, P., Bhatnagar, P., Kaur, N., Roy, S., Singh, N., Denzongpa, P., Haldar, P., & Loharikar, A. (2021). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine introduction in Sikkim state: Best practices from the first statewide multiple-age cohort HPV vaccine introduction in India-2018–2019. Vaccine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.024

- Ahmed, D., VanderEnde, K., Harvey, P., Bhatnagar, P., Kaur, N., Roy, S., Singh, N., Denzongpa, P., Haldar, P., & Loharikar, A. (2022). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine introduction in Sikkim state: Best practices from the first statewide multiple-age cohort HPV vaccine introduction in India-2018–2019. Vaccine, 40(Suppl 1), A17–A25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.07.024

- Ali, R. F., Arif Siddiqi, D., Mirza, A., Naz, N., Abdullah, S., Kembhavi, G., Tam, C. C., Offeddu, V., & Chandir, S. (2022). Adolescent girls’ recommendations for the design of a human papillomavirus vaccination program in Sindh, Pakistan: A qualitative study. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(5), 2045856. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2045856

- Ammenwerth, E. (2019). Technology acceptance models in health informatics: TAM and UTAUT. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 263, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190111

- Arbyn, M., Weiderpass, E., Bruni, L., de Sanjosé, S., Saraiya, M., Ferlay, J., & Bray, F. (2020). Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 8(2), e191–e203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6

- Ardito, V., Golubev, G., Ciani, O., & Tarricone, R. (2023). Evaluating barriers and facilitators to the uptake of mHealth apps in cancer care using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Scoping Literature Review. JMIR Cancer, 9, e42092. https://doi.org/10.2196/42092

- Awan, U. A., Guo, X., Khattak, A. A., Hassan, U., & Bashir, S. (2023). HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening in Afghanistan threatened. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 23(2), 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00868-4

- Basu, P., & Mittal, S. (2011). Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccine among the urban, affluent and educated parents of young girls residing in Kolkata, Eastern India. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 37(5), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01371.x

- Bhuiyan, A., Sultana, F., Islam, J. Y., Chowdhury, M. A. K., & Nahar, Q. (2018). Knowledge and acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine for cervical cancer prevention among urban professional women in Bangladesh: A mixed method study. BioResearch Open Access, 7(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2018.0007

- Biellik, R., Levin, C., Mugisha, E., LaMontagne, D. S., Bingham, A., Kaipilyawar, S., & Gandhi, S. (2009). Health systems and immunization financing for human papillomavirus vaccine introduction in low-resource settings. Vaccine, 27(44), 6203–6209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.003

- Bingham, A., Drake, J. K., & LaMontagne, D. S. (2009). Sociocultural issues in the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccine in low-resource settings. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(5), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.50

- Burki, T. K. (2023). India rolls out HPV vaccination. The Lancet Oncology, 24(4), e147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00118-3

- Burney, A., & Zafar, R. (2023). HPV vaccination as a mode of cervical cancer prevention in Pakistan. South Asian Journal of Cancer, 12(1), 51–52. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1764211

- Canon, C., Effoe, V., Shetty, V., & Shetty, A. K. (2017). Knowledge and attitudes towards human papillomavirus (HPV) among academic and community physicians in Mangalore, India. Journal of Cancer Education, 32(2), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-0999-0

- Chellapandian, P., Myneni, S., Ravikumar, D., Padmanaban, P., James, K. M., Kunasekaran, V. M., Manickaraj, R. G. J., Arokiasamy, C. P., Sivagananam, P., Balu, P., Chelladurai, U. M., Veeraraghavan, V. P., Baluswamy, G., Sreekandan, R. N., Kamaraj, D., Suga, S. S. D., Kullappan, M., Ambrose, J. M., Kamineni, S. R. T., & Surapaneni, K. M. (2021). Knowledge on cervical cancer and perceived barriers to the uptake of HPV vaccination among health professionals. BMC Women’s Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01205-8

- Cutts, F. T., Franceschi, S., Goldie, S., Castellsague, X., de Sanjose, S., Garnett, G., Edmunds, W. J., Claeys, P., Goldenthal, K. L., Harper, D. M., & Markowitz, L. (2007). Human papillomavirus and HPV vaccines: A review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85(9), 719–726. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.06.038414

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Garland, S. M., Bhatla, N., & Ngan, H. Y. S. (2012). Cervical cancer burden and prevention strategies: Asia oceania perspective. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 21(9), 1414–1422. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0164

- Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. (2023). Human papillomavirus vaccine support. https://www.gavi.org/types-support/vaccine-support/human-papillomavirus.

- GLOBOCAN. (2020). Cervix uteri - International Agency for Research on Cancer. International Agent for Research on Cervic Uteri. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/23-Cervix-uteri-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Guadiana, D., Kavanagh, N. M., & Squarize, C. H. (2021). Oral health care professionals recommending and administering the HPV vaccine: Understanding the strengths and assessing the barriers. PLoS One, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248047

- Hanson, C. M., Eckert, L., Bloem, P., & Cernuschi, T. (2015). Gavi HPV programs: Application to implementation. Vaccines, 3(2), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines3020408

- Hingmire, S., Tshomo, U., Dendrup, T., Patel, A., & Parikh, P. (2023). Cervical cancer HPV vaccination and Bhutan. South Asian Journal of Cancer, 12(1), 41–43. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1764220

- Holroyd, T. A., Yan, S. D., Srivastava, V., Srivastava, A., Wahl, B., Morgan, C., Kumar, S., Yadav, A. K., & Jennings, M. C. (2021). Designing a pro-equity HPV vaccine delivery program for girls who have dropped out of school: Community perspectives from Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Promotion Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399211046611

- Hong, S.-A. (2023). COVID-19 vaccine communication and advocacy strategy: A social marketing campaign for increasing COVID-19 vaccine uptake in South Korea. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01593-2

- Jacob, M., Mawar, N., Menezes, L., Kaipilyawar, S., Gandhi, S., Khan, I., Patki, M., Bingham, A., LaMontagne, D. S., Bagul, R., Katendra, T., Karandikar, N., Madge, V., Chaudhry, K., Paranjape, R., & Nayyar, A. (2010). Assessing the environment for introduction of human papillomavirus vaccine in India. The Open Vaccine Journal. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875035401003010096

- Jindal, H. A., Kaur, A., & Murugan, S. (2017). Human papilloma virus vaccine for low and middle income countries: A step too soon? Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 13(11), 2723–2725. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2017.1358837

- Johnson, D. C., Bhatta, M. P., Gurung, S., Aryal, S., Lhaki, P., & Shrestha, S. (2014). Knowledge and awareness of human papillomavirus (HPV), cervical cancer and HPV vaccine among women in two distinct Nepali communities. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(19), 8287–8293. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8287

- Kamath, A., Yadav, A., Baghel, J., Bansal, P., & Mundle, S. (2021). Level of awareness about HPV infection and vaccine among the medical students: A comprehensive review from India. Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology, 19(4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-021-00553-5

- Kaur, P., Mehrotra, R., Rengaswamy, S., Kaur, T., Hariprasad, R., Mehendale, S. M., Rajaraman, P., Rath, G. K., Bhatla, N., Krishnan, S., Nayyar, A., & Swaminathan, S. (2017). Human papillomavirus vaccine for cancer cervix prevention: Rationale & recommendations for implementation in India. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 146(2), 153–157. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1906_16

- Krupp, K., Marlow, L. A. V., Kielmann, K., Doddaiah, N., Mysore, S., Reingold, A. L., & Madhivanan, P. (2010). Factors associated with intention-to-recommend human papillomavirus vaccination among physicians in Mysore, India. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.001

- Kumari, P., & Pankaj, S. (2021). HPV vaccination programmme-hurdles & challenges in a tertiary care centre. Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-021-00548-2

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Madhivanan, P., Krupp, K., Yashodha, M. N., Marlow, L., Klausner, J. D., & Reingold, A. L. (2009). Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among parents of adolescent girls in Mysore, India. Vaccine, 27(38), 5203–5208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.073

- Madhivanan, P., Li, T., Srinivas, V., Marlow, L., Mukherjee, S., & Krupp, K. (2014). Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among parents of adolescent girls: Obstacles and challenges in Mysore, India. Preventive Medicine, 64, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.002

- Mahumud, R. A., Gow, J., Alam, K., Keramat, S. A., Hossain, M. G., Sultana, M., Sarker, A. R., & Islam, S. M. S. (2020). Cost-effectiveness of the introduction of two-dose bi-valent (Cervarix) and quadrivalent (Gardasil) HPV vaccination for adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Vaccine, 38(2), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.037

- Mehta, S., Rajaram, S., Goel, G., & Goel, N. (2013). Awareness about human papilloma virus and its vaccine among medical students. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 38(2), 92–94. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.112438

- Meyer, G. (2015). An evidence-based healthcare system and the role of the healthcare professions. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 109(4–5), 378–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2015.07.014

- Monaco, A., Casteig Blanco, A., Cobain, M., Costa, E., Guldemond, N., Hancock, C., Onder, G., Pecorelli, S., Silva, M., Tournoy, J., Trevisan, C., Votta, M., Yfantopoulos, J., Yghemonos, S., Clay, V., Mondello Malvestiti, F., De Schaetzen, K., Sykara, G., & Donde, S. (2021). The role of collaborative, multistakeholder partnerships in reshaping the health management of patients with noncommunicable diseases during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 33(10), 2899–2907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-021-01922-y

- Mooketsane, K. S., & Phirinyane, M. B. (2015). Health governance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Social Policy, 15(3), 345–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018115600123d

- Núñez, I., & Valdés-Ferrer, S. I. (2023). Fulminant mpox as an AIDS-defining condition: Useful or stigmatising? Lancet (London, England), 401(10380), 881–884. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00333-1

- Olaleye, Y. (2019). Social mobilization and community participation in development programmes (pp. 389–408). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yemisi-Olaleye/publication/333172944_Social_Mobilization_and_Community_Participation_in_Development_Programmes/links/5d0a395d299bf1f539cf4ebd/Social-Mobilization-and-Community-Participation-in-Development-Programmes.pd.

- Orchowski, L. M., Oesterle, D. W., Zong, Z. Y., Bogen, K. W., Elwy, A. R., Berkowitz, A. D., & Pearlman, D. N. (2023). Implementing school-wide sexual assault prevention in middle schools: A qualitative analysis of school stakeholder perspectives. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(3), 1314–1334. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22974

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Padmanabha, N., Kini, J. R., Alwani, A. A., & Sardesai, A. (2019). Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among medical students in Mangalore, India. Vaccine, 37(9), 1174–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.032

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pandey, D., Vanya, V., Bhagat, S., Vs, B., & Shetty, J. (2012). Awareness and attitude towards human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine among medical students in a premier medical school in India. PLoS One, 7(7), e40619. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040619

- PATH. (2022). Global HPV vaccine introduction overview. https://media.path.org/documents/Global_Vaccine_Intro_Overview_Slides_Final_PATHwebsite_MAR_2022_qT92Wwh.pdf?_gl=1*7u8qw5*_ga*ODY4Nzk5MTkyLjE2ODE4MDQ1NzY.*_ga_YBSE7ZKDQM*MTY4MTgwNDU3NS4xLjAuMTY4MTgwNDU3NS4wLjAuMA.

- Paul, P., Tanner, A. E., Gravitt, P. E., Vijayaraghavan, K., Shah, K. V., Zimet, G. D., & Study Group, C. (2014). Acceptability of HPV vaccine implementation among parents in India. Health Care for Women International, 35(10), 1148–1161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2012.740115

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Prinja, S., Bahuguna, P., Faujdar, D. S., Jyani, G., Srinivasan, R., Ghoshal, S., Suri, V., Singh, M. P., & Kumar, R. (2017). Cost-effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccination for adolescent girls in Punjab state: Implications for India’s universal immunization program. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30734

- Priya, S., & Kumar, M. A. (2023). Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of cervical cancer and hpv vaccine among pharmacy and paramedical female students at a private university (South India). International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 15. https://doi.org/10.31838/ijpr/2020.12.03.097

- Pulerwitz, J., Michaelis, A., Weiss, E., Brown, L., & Mahendra, V. (2010). Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from Horizons research and programs. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), 125(2), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491012500218

- Rajkhowa, P., Dsouza, V. S., Kharel, R., Cauvery, K., Mallya, B. R., Raksha, D. S., Mrinalini, V., Sharma, P., Pattanshetty, S., Narayanan, P., Lahariya, C., & Brand, H. (2023). Factors influencing monkeypox vaccination: A cue to policy implementation. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-023-00100-9

- Rao, B. A., Seshadri, J. G., & Thirthahalli, C. (2017). Impact of health education on HPV vaccination. Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40944-017-0134-0

- Rebecchi, A., Gola, M., Kulkarni, M., Lettieri, E., Paoletti, I., & Capolongo, S. (2016). Healthcare for all in emerging countries: A preliminary investigation of facilities in Kolkata, India. Annali Dell’Istituto Superiore Di Sanita, 52(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.4415/ANN_16_01_15

- Reddy, N. K. K., Bahurupi, Y., Kishore, S., Singh, M., Aggarwal, P., & Jain, B. (2020). Awareness and readiness of health care workers in implementing Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana in a tertiary care hospital at Rishikesh. Nepal Journal of Epidemiology, 10(2), 865–870. https://doi.org/10.3126/nje.v10i2.27941

- Sankaranarayanan, R., Basu, P., Kaur, P., Bhaskar, R., Singh, G. B., Denzongpa, P., Grover, R. K., Sebastian, P., Saikia, T., Oswal, K., Kanodia, R., Dsouza, A., Mehrotra, R., Rath, G. K., Jaggi, V., Kashyap, S., Kataria, I., Hariprasad, R., Sasieni, P., … Purushotham, A. (2019). Current status of human papillomavirus vaccination in India’s cervical cancer prevention efforts. The Lancet Oncology, 20(11), e637–e644. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30531-5

- Saxena, A. (2022). eVIN to Co-WIN: Digitizing India’s immunization programme. https://www.undp.org/india/blog/evin-co-win-digitizing-india’s-immunization-programme.

- Shah, P., Shetty, V., Ganesh, M., & Shetty, A. K. (2021). Challenges to human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among women in south India: An exploratory study. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 105(4), 966–973. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-1650

- Shah, P. M., Ngamasana, E., Shetty, V., Ganesh, M., & Shetty, A. K. (2022). Knowledge, attitudes and HPV vaccine intention among women in India. Journal of Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01072-w

- Shaikh, M. Y., Hussaini, M. F., Narmeen, M., Effendi, R., Paryani, N. S., Ahmed, A., Khan, M., & Obaid, H. (2019). Knowledge, attitude, and barriers towards human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among youths of Karachi, Pakistan. Cureus, 11(11), e6134. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6134

- Sharma, D. C. (2013). Rights violation found in HPV vaccine studies in India. The Lancet Oncology, 14(11), e443. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70420-0

- Shet, A., & Bar-Zeev, N. (2023). Human papillomavirus vaccination strategies for accelerating action towards cervical cancer elimination. The Lancet Global Health, 11(1), e4–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00511-3

- Shetty, S., Shetty, V., Badiger, S., & Shetty, A. K. (2021). An exploratory study of undergraduate healthcare student perspectives regarding human papillomavirus and vaccine intent in India. Women's Health, 17. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455065211055304

- Singh, Y., Shah, A., Singh, M., Verma, S., Shrestha, B. M., Vaidya, P., Nakarmi, R. P., & Shrestha, S. B. (2010). Human papilloma virus vaccination in Nepal: An initial experience in Nepal. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention : APJCP, 11(3), 615–617.

- Swarnapriya, K., Kavitha, D., & Reddy, G. M. M. (2015). Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding HPV vaccination Among medical and para medical in students, India a cross sectional study. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 16(18), 8473–8477. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.18.8473

- Thammatacharee, N., Tisayaticom, K., Suphanchaimat, R., Limwattananon, S., Putthasri, W., Netsaengtip, R., & Tangcharoensathien, V. (2012). Prevalence and profiles of unmet healthcare need in Thailand. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 923. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-923

- The Economic Times. (2021). The Indian cold chain sector is expected to grow at 14% CAGR during 2021–2023. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/property-/-cstruction/the-indian-cold-chain-sector-is-expected-to-grow-at-14-cagr-during-2021-2023/articleshow/83426568.cms.

- The World Bank. (2016). Bangladesh: Ensuring education for all Bangladeshis. https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2016/10/07/ensuring-education-for-all-bangladeshis.

- The World Bank. (2023a). Low & middle income. https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-and-middle-income.

- The World Bank. (2023b). South Asia. https://data.worldbank.org/country/8S.

- Tran, B. X., Than, P. Q. T., Tran, T. T., Nguyen, C. T., & Latkin, C. A. (2019). Changing sources of stigma against patients with HIV/AIDS in the rapid expansion of antiretroviral treatment services in Vietnam. BioMed Research International, 4208638. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4208638

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tsui, J., LaMontagne, D. S., Levin, C., Bingham, A., & Menezes, L. (2009). Policy development for human papillomavirus vaccine introduction in low-resource settings. The Open Vaccine Journal. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875035400902010113

- UNICEF. (2021). Building confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine in India. https://www.unicef.org/india/stories/building-confidence-covid-19-vaccine-india.

- Van Boekholt, T. A., Duits, A. J., & Busari, J. O. (2019). Health care transformation in a resource-limited environment: Exploring the determinants of a good climate for change. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 12, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S194180

- Wigle, J., Coast, E., & Watson-Jones, D. (2013). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine implementation in low and middle-income countries (LMICs): Health system experiences and prospects. Vaccine, 31(37), 3811–3817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.016

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107.

- World Health Organization. (2014). Principles and considerations for adding a vaccine to a national immunization programme: from decision to implementation and monitoring. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/111548?search-result=true&query=HPV+vaccine¤t-scope=10665%2F26724&rpp=10&sort_by=score&order=desc&page=3.

- World Health Organization. (2016a). Guide to introducing HPV vaccine into national immunization programmes. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/253123/9789241549769-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- World Health Organization. (2016b). HPV vaccine introduced in Bangladesh. https://www.who.int/bangladesh/news/detail/18-05-2016-hpv-vaccine-introduced-in-bangladesh.

- World Health Organization. (2016c). National immunization programme: HPV vaccine demonstration programme in Kaski and Chitwan. https://un.info.np/Net/NeoDocs/View/7108.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107.

- World Health Organization. (2022a). Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage. https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/coverage/hpv.html.

- World Health Organization. (2022b). Risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) for monkeypox outbreaks: Interim guidance, 24 June 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-RCCE-2022.1.

- World Health Organization. (2022c). Universal health coverage (UHC). health coverage %28UHC%29 means that all people,rehabilitation%2C and palliative care across the life course.