ABSTRACT

African refugee women resettled in the United States are exposed to multiple risk factors for poor mental health. Currently, no comprehensive framework exists on which to guide mental health interventions specific to this population. Through a community-based participatory research partnership, we interviewed N = 15 resettled African refugees living in Rhode Island. Here we (1) describe how meanings of mental health within the African refugee community vary from US understandings of PTSD, depression, and anxiety and (2) generate a framework revealing how mental health among participants results from interactions between social support, African sociocultural norms, and US norms and systems. Multiple barriers and facilitators of mental wellbeing lie at the intersections of these three primary concepts. We recommend that public health and medicine leverage the strength of existing community networks and organisations to address the heavy burden of poor mental health among resettled African refugee women.

Globally, the number of individuals displaced by conflict is at an unprecedented high. As of 2022, 108.4 million people are living forcibly displaced from their homes, 35.3 million of them living internationally as refugees, and this number continues to grow with ongoing conflict (UNHCR, Citation2023). Refugees, or people who are forced to flee their homes for fear of violence or persecution, have a vastly increased risk for mental health disorders (i.e. depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) compared to general adult populations (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Siriwardhana et al., Citation2014). Refugees resettled in high income countries, e.g. Western Europe and the United States (US), are 15 times more likely to have PTSD and 14 times more likely to have depression compared to their native-born neighbours (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Henkelmann et al., Citation2020; Scoglio & Salhi, Citation2021). Two major additional risk factors for generalised anxiety disorder, specifically, among refugees are (1) resettling in the US and (2) being a woman (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Jankovic-Rankovic et al., Citation2020).

Meta-analyses indicate that traumatic events endured through the process of fleeing conflict and finding safety are strong predictors of PTSD, depression, and anxiety among refugees (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2017; Hawkins et al., Citation2021; Porter & Haslam, Citation2005). These exposures associated with PTSD, depression and anxiety – collectively referred to here as mental health outcomes due to their common risk profiles and high comorbidity – operate at multiple socioecological levels, including individual, interpersonal, community, and organisational (Farhood et al., Citation2016; Goessmann et al., Citation2020; Hawkins et al., Citation2021; Idemudia & Boehnke, Citation2020). Commonly cited risk factors for poor mental health during wartime or while fleeing for safety include living amongst high rates of crime, experiencing physical or sexual violence, depletion of socioeconomic resources, and witnessing atrocities (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Chen et al., Citation2017; Tlapek, Citation2015). Risk factors for poor mental health that occur once refugees are resettled include unemployment, low income, poor English language skills, changing family dynamics, acculturation, and social isolation (Birman & Tran, Citation2008; Bogic et al., Citation2015; Jorgenson & Nilsson, Citation2021; Mahajan et al., Citation2021). Stressors experienced during resettlement may exacerbate symptoms related to previous trauma and increase the fear of surviving in a new place (Bogic et al., Citation2015; Smigelsky et al., Citation2017). Therefore, mental health after resettling must be considered within the context of a person’s entire refugee experience rather than during resettlement alone.

For African refugee women, cultural gender dynamics may worsen mental health during resettlement. Many African societies are patriarchal, with women expected to assume a subservient role to men (Harrison et al., Citation2014; Tlapek, Citation2015). Upon resettlement, African refugee women may have limited education and English-fluency and are likely to have experienced some form of sexual or physical violence (Ramzy et al., Citation2017; Stark et al., Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Tlapek, Citation2015). One in five women who are refugees, internally displaced, or living in complex humanitarian settings have experienced sexual violence, though this is likely a gross underestimate (Vu et al., Citation2014); the rate of sexual violence may also be higher for women coming from certain areas of conflict. For example, the prevalence of sexual violence during the height of political violence and conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was unprecedented, with an estimated 1,150 women between the ages of 15 and 49 being raped every day (Peterman et al., Citation2011). Resettled African refugee women may therefore lie at the intersection of multiple significant risk factors for poor mental health upon resettlement. Conversely, several powerful sources of resilience among resettled African refugees have been documented, including social support, communalism, religion and spirituality, and education (Babatunde-Sowole et al., Citation2016; Kiteki, Citation2016). Despite these many documented risk and resiliency factors, currently no comprehensive framework exists on which to build mental health interventions specific to this population, especially taking into account how mental health may be understood differently across cultures (Betancourt et al., Citation2015) and can deviate from the World Health Organization definition.Footnote1

Study population

Though parts of sub-Saharan Africa are thriving following their independence from European colonial rule (Byfield et al., Citation2015), many nations are still finding their way out of the legacy of colonialism. In several areas across sub-Saharan Africa, the struggle to establish peaceful political structures continues today, creating a rise in the number of civilians who have been exposed to violent conflict. Two key examples are the modern histories of DRC and neighbouring Rwanda.

Brutal conflict has plagued DRC for over two decades. With connections to the 1994 Rwandan genocide and civil wars in the neighbouring countries of Sudan and Uganda, the ongoing conflict in DRC has been referred to as ‘Africa’s World War’ (Meger, Citation2010). Rich with natural resources and mineral wealth, DRC’s eastern provinces were exploited by European colonisers and now by varying political forces on the African continent (Nest et al., Citation2006). Armed conflict continues within DRC today between domestic armies, international militia groups and newly emerging rebel groups (Nest et al., Citation2006). Notably, in addition to violence across political and militia groups, rape of women and girls has been used since the outbreak of war in 1998 on a ‘scale never seen before’ (Nolen, Citation2005). As a result of the brutal violence against civilians in DRC, an estimated five million Congolese have been displaced between 2017 and 2019 alone, though Congolese civilians have been fleeing in mass groups since the 1990s (UNHCR, Citation2020).

In Rhode Island (RI), the majority of all resettled refugees entering the state in the last decade have been from West and Central Africa, specifically Liberia, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Somalia (Omaha World-Herald, Citation2017). Although exact data on the current number of African refugees living in Rhode Island are not readily available, from our community partners we are aware of a growing community of roughly 100 families comprising at least 500 people concentrated in the greater Providence, Rhode Island area. The majority of refugees living in RI come from the DRC. These individuals and families have arrived in RI over the last decade as a result of ongoing conflict in Eastern DRC, as well as related conflict in neighbouring countries Rwanda and Burundi.

Study objectives

Recent literature calls for new research to focus on the interrelated, multi-level determinants that influence mental health outcomes among resettled refugee women (Hawkins et al., Citation2021; Siriwardhana et al., Citation2014; Wachter et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the objective of this research is to develop a deep understanding of mental health experiences among resettled African refugee women in the context of their broader refugee experience to generate a framework for understanding mental health experiences among African refugee women living in the US to inform strategies for mental health interventions based on real world contexts.

Two research questions are addressed: (1) In what ways, if any, do mental health experiences of resettled African refugee women relate to US understandings of the trauma-related mental health diagnoses PTSD, depression, and anxiety; and (2) What are the barriers and facilitators to mental well-being post-resettlement? These research questions are addressed within the African refugee community in Rhode Island.

Materials and methods

Research design

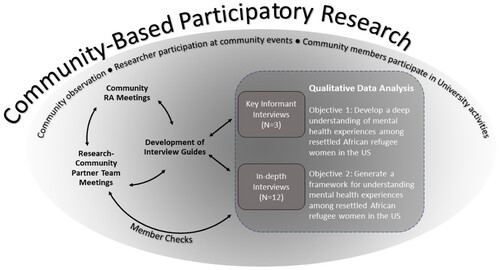

This study was designed using community-based participatory research (CBPR) practices and thus was designed and implemented in partnership with an African refugee community-led organisation in RI. This methodological approach prioritised: community input throughout all stages of the research; equitable compensation of community partners (competitive hourly rate for community-member research assistants, financial reimbursement of organisational leaderships’ time collaborating on research materials, providing platform for university lectures); and a shared goal among community and academic partners of affecting social change (Lloyd Michener et al., Citation2012; Wallerstein & Duran, Citation2006). The research team was comprised of researchers from Brown University and directors of the community-led organisation serving a portion of RI’s resettled African refugee population called Women’s Refugee Care (WRC). WRC functions as a non-profit organisation assisting resettled African refugee women and families in their transition to life in the US.

represents the CBPR approach that provided the backdrop for this research. The community-research partnership began when the first three authors met over a mutual interest in addressing the needs of resettled African women living in RI. At the invitation of WRC, the first author attended community events to observe and to participate in a volunteer capacity; WRC leaders were invited to lecture at the University and partake in CBPR-related events at the school. Throughout the design of the study, data collection, and data analysis, the community-research team continued to meet about the study and community issues; the first author held regular reflection meetings with two multi-lingual community members hired as research assistants (RAs) whom she trained in research ethics, interviewing, and interpreting.

Figure 1. Community-based participatory research approach as the foundation for community-partnership, study design, data collection, and data analysis.

The research team designed a two-phase qualitative study. Phase 1 was comprised of key informant interviews which would provide essential background information on which to build the rest of the study. These formative interviews provided context for Phase 2, which was comprised of in-depth interviews with women in the community. All study procedures and data collection materials were approved by Brown University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Protocol #1906002475), and all participants provided informed consent prior to enrolment.

Participant selection

Purposive sampling was used to identify individuals to participate in Phase 1 key informant interviews. Individuals were eligible to participate if they identified as a refugee from any region of Africa; were at least 18 years of age; spoke English; and were able to provide informed consent. Key informant interviews covered three primary areas, including (1) meanings of mental health within the African refugee community; (2) changes in mental health experiences over time; and (3) cultural considerations around discussing mental health in a research setting.

For Phase 2 in-depth interviews, recruitment was led by RAs, WRC Directors, and an additional Providence-based non-profit organisation serving refugees. Given their membership in the community, they used purposive sampling to identify eligible women in the community as possibly participants. Women were either called or approached in-person while visiting community centres, described the intent of the study, and asked if they were interested in participating. Women were eligible to participate in in-depth interviews if they identified as a refugee woman from Africa; were at least 18 years of age; spoke English or Swahili (the language most commonly spoken within this community); and were able to provide informed consent.

Data collection

Key informant interviews were completed in November 2019 by the first author, took place in English, and were done in-person in a private room located within the WRC offices. The key informant interview guide was semi-structured and designed by the university research team members. In-depth interviews were completed between June and October 2020 over the phone by the first author in English, or English and Swahili and assisted by RAs for interpreting. Interviews lasted an average length of 45 minutes and were audio-recorded; the interviewer took detailed notes throughout. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study and were given $15 to reimburse them for their time. For interviews completed over the phone, though facial expressions could not be captured, tone and non-verbal expressions were documented in written notes.

Key informant interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide focused on meanings of mental health, Swahili-English translations for mental health terminology, refugee mental health over time, and how to approach discussing mental health within the community. Results of these interviews were then used to create the semi-structured interview guide used for in-depth interviews. The community-member RAs reviewed and revised the in-depth interview guides; the meaning of each question and accompanying probes were discussed at length between the first author and RAs to ensure that each question would be understandable, relevant, and consistent across interviews when translated to Swahili. The RAs then forward- and back-translated the interview guide from English to Swahili. The in-depth interview guides addressed: (1) life before coming to the US; (2) arriving in the US; (3) mental health and feelings over time; (4) facilitators and barriers to mental wellbeing among African refugee women; (5) ways to help those suffering in the community; and (6) experiences with COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement in the US. These topics were refined on a continual basis; for example, the final topic was formally added to the interview guide following the first half of interviews due to its consistent presence in participant narratives. This cyclical process of data collection, instrument development, and analysis is discussed more in the next section.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and analysed using NVivo software (QSR International, Citation2020). In Phase 1, key informant interviews were analysed by the first author and coded into pre-defined categories intended to inform data collection in Phase 2. In-depth interviews and key informant interviews were then analysed together in Phase 2. The first author completed initial open-coding and memo-writing using NVivo. This took place alongside data collection, allowing the research team to continually revisit their assumptions to maximise study acceptability, to amend the in-depth interview guides as needed, and to determine when saturation was reached (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019). The research team, comprised of both academic and community partners, discussed the data, reviewing de-identified transcripts and discussed their meaning. After initial open-coding and memo-writing were complete, the team finalised the codebook, and interviews were recoded by the first author to ensure consistency.

Axial coding was then used to examine relationships among codes that were hypothesised throughout memo-writing and team discussions (Birks & Mills, Citation2015). Synergies and relations among major categories that arose through the initial and axial coding processes were identified, giving rise to a single theoretical proposition pertaining to the two research questions regarding meanings of mental health and barriers and facilitators to mental wellbeing (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990).

In line with the study’s CBPR approach, data analysis used a modified-grounded theory approach to create an inductive, broad representation of African refugee women’s mental health as experienced by this community (Chun Tie et al., Citation2019; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1997). The research team used an iterative and team-based process to ensure rigorous, ethical, and trustworthy findings (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1989; Tracy, Citation2010). Member checks and reflections – frequent opportunities for community partner authors to provide feedback and guide the analytic process – were built in at several points throughout the analysis to enhance rigour and the credibility of findings () (Kraemer Diaz et al., Citation2015; Lindlof & Taylor, Citation2002).

Results

Participant characteristics

N = 3 key informant interviews and n = 12 in-depth interviews were completed, for a total of N = 15 interviews. All interview participants came from Africa to the US as refugees within the last 10 years (). Each reported fleeing their home country during conflict to find safety. Thirteen participants were from Central Africa, and one participant each came from Southern and West Africa. All participants were women, apart from one male key informant. Results are presented in two sections. First, the primary findings from the key informant interviews are described as formative research. Second, the results of the grounded theory-informed analysis of all interviews combined are presented as primary findings.

Table 1. Demographic and descriptive characteristics of participants, N = 15.

Formative research: Initial findings from key informant interviews

Initial formative work was comprised of key informant interviews conducted with English-speaking leaders within the RI African refugee community.

Meanings of mental health

Mental health is a term that key informants either learned at school in Africa or were exposed to while engaging with healthcare providers in humanitarian settings. Generally, however, mental health as a term was considered ‘very strange for the African community’. Further, there was no direct translation of ‘mental health’ from English to Swahili, the official language of each key informant. Instead, key informants offered Swahili words that translated to ‘feeling bad’ or being a ‘fool’. One key informant explained that ‘when a high percentage of people didn’t go to school, it becomes very hard to ask about mental health’, as it was not a concept commonly discussed among the lay population.

Though the term ‘mental health’ seemed foreign, the experiences associated with ‘that hidden sickness’ were well understood and described in detail. Signs of poor mental health included when people ‘lose the desire of doing something’; ‘don’t want to move forward [and] stay in the state of life that they are in’; ‘[do not] want to interact with other people’; are ‘sleepy, [and] not interested’ at community gatherings; ‘get crazy for a period of time’; ‘complain about physical pain’; or are ‘not stable’. One key informant noted that some in their community may ‘have mental health, but they don’t want to complain’, as they are simply grateful to be alive.

These descriptions reveal two major findings critical to the construction of the rest of the study. First, when asked to define mental health, key informants described symptoms of poor mental health. As one shared, mental health ‘mean[s] that you have a problem inside you that you cannot express’. Mental health was not understood as a neutral term that can be either good or bad, as people in their community ‘don’t have any idea what good mental health is’. This is a significant deviation from the US understanding of mental health following the WHO definition as overall psychological wellbeing, which has the potential to range from positive to negative. Second, the range of descriptions of mental health included hallmark symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety, but not in these direct terms.

Translations of mental health from English to Swahili

Key informants differed on whether or not they believed there were direct translations for ‘mental health’ from English to Swahili. Some shared that there was no Swahili translation for ‘mental health’, while the another shared the term akapoteza akili, directly translating to ‘loose his mind’. All agreed that the best translation for ‘mental health’ was to kujisikya, meaning feelings. Key informant descriptions of PTSD, depression and anxiety were extremely similar if not identical. Though they knew that these were different medical diagnoses that one may receive ‘in the refugee camp’, their descriptions of the symptoms and associated feelings were often indistinguishable. Key informants argued that the study would be best suited to not distinguish between these diagnoses, and instead, simply describe the feelings and symptoms we sought to understand. This approach would be most accessible to community members, including English speaking women.

Discussing mental health in a research setting

Key informants explained that mental health was not discussed in their community openly ‘in the public’. The first key informant shared,

In our culture, when you face something that you don’t really understand and you have difficulties to deal with it, the only way African people do and deal with it is to pray and to keep silent and that is the problem.

Though they described how the ‘African mentality’ is to not share ‘especially hard things that we experience’, key informants believed that women in the African refugee community would be open to discussing mental health in an interview setting among other trusted women. They shared that – though it may not be discussed publicly – women do confide in other women, ‘a friend or a religious leader’. In a research setting, ‘it matters who that interviewer is. Not just that they are in the community, but it matters which woman that is asking the questions, depending on who that woman is [and] who is the participant’. For this reason, key informants suggested that participants be recruited by community organisations who know community members personally and can who may be comfortable discussing sensitive topics. Key informants also cited the prolonged presence of the first author and interviewer within the community in helping to create a feeling of trust, making participation more acceptable.

Key informants shared that direct questions about post-resettlement experiences would be acceptable; however, they recommended that questions about experiences in wartime and while finding safety should remain vague. Otherwise, key informants shared, ‘you will not get what you want from them’.

Applying the formative research

These initial findings allowed us to tailor our scientific approach to the African refugee community, maximising the acceptability and feasibility of the study to the community. First, rather than using ‘mental health’ as a term, our interview guide referred to ‘feelings throughout the resettlement process’. We offered descriptions for PTSD, depression, and anxiety, rather than asking about those terms alone. Second, only community-research partners would recruit participants. Lastly, we rephrased all questions to be open-ended about wartime and escape experiences.

Primary findings from a modified-grounded theory approach

We developed a framework to understand the present experiences of African refugee women living in the US, in the context of their past lived experiences and accompanying mental health outcomes using all key informant and in-depth interviews (). We find that mental health experiences are affected by three intersecting primary domains: social support, collective and shared African norms, and US norms and systems. Where one primary domain intersects with another, this is where barriers or facilitators to mental wellbeing arise. Finally, we find that community-led efforts to assist African refugee women optimally lie at the intersection of all three primary domains in order to break down barriers and promote facilitators of mental wellbeing. Our findings are described below in three thematic sections.

Figure 2. Post-resettlement determinants of mental health experiences among resettled African refugee women.

Social support is a primary determinant of mental wellbeing and is greatly facilitated by collective and shared African norms

In general, social support was highlighted as a major contributor to resettlement experiences and mental wellbeing. In fact, the ability to access social support as a resource was a signal to many that a person is doing well, whereas those who are shut off from social support resources are indicating to others that they are unwell. For one participant, a person with good mental health is ‘able to express yourself’ to another by saying ‘I’m not feeling well’. She continued, ‘The bad one [poor mental health], you don’t want to talk to someone’, saying things like, ‘leave me alone’.

Social support was frequently discussed whenever participants described their perception of collective and shared African norms. Participants explained that Africans ‘share a culture, and we understand each other through our similar languages’, and did not distinguish this aspect of culture to be country specific. Participants described the African cultural norm of expansive family, shared spaces, and a strong fabric of social support.Footnote2 Participants describe family as not limited to blood-relatives or those who live within one house. One woman shared that in her home country, ‘you live like all [is] family, with the aunties, the uncle, the wife. There are so [many] people’. In Africa, ‘I think like the neighbor is my kids’. Simply sharing an African identity was reason enough to feel that others are family and to care for them as such. ‘In Africa, we say hi to everybody, we dance for everybody’. In times of joy ‘everybody should be there to celebrate, to be together’, while in times of difficulty, ‘[in] our culture of being together, no one can feel really isolated, because … we live with the principle of: I am because you are’.

Support for others in the community was deeply engrained within African social norms. The natural tendency towards togetherness and communal support created resiliency for these resettled women. Members of this community discussed rebuilding the social support structures they knew from home in the US. One participant explained, ‘[our community] is very supportive. We have good people, think about each other, how to help. Anytime there is a problem, or anything, events in our community, where we come together and then try to find the solution’. The social support from the community therefore served as a backboard in times of hardship. One participant described her personal experience with this, sharing:

In [this city], you are not in your hometown, everything is difficult, but you make yourself comfortable to make it easy. Before, it was so hard. Right now, [I] can say [it is] not as difficult like it was before … When you miss your people, if you have a difficult time, you can share [your] story, and they can maybe help you. Different people that we have in the community … [they] help too much. If you have sometime difficult, you can go there, and they help you so much.

The person who come to pick us [up] … the time he came to airport here … First thing we hear, he is talking. He speak Swahili, he speak French. We say, ‘Ah, this person is our father.’ We start calling him father, and to this day, we call Papa … They welcome us in this place … I see them like my parents. I treat them like my parents. My children, they see them like they are grandfather and grandmother.

Tension between collective and shared African norms and US norms and systems acts as a considerable barrier to mental wellbeing

When discussing life in America, participants described what they understood to be cultural norms and critical infrastructures that make up US society. Those most frequently discussed were social boundaries between households, gender dynamics between men and women, and anti-Black racism. The systems participants detailed included housing contracts and leases; bill structures; employment; medical insurance; transportation infrastructures; food availability; law enforcement; public schools; and access to English language learning.

Seldom were US norms and systems discussed without contrasting them with African norms. In few cases, women expressed a preference for US norms and systems, specifically regarding ‘having enough food’, being able to call the police if you have a problem, and having ‘access to medical’ insurance and services. Overwhelmingly, however, the change in their cultural backdrop presented challenges to everyday life and mental wellbeing.

A common example of how a changing social landscape affected mental wellbeing was the social boundaries experienced across households in the US. One woman explained that ‘here, they don’t say hi to everybody … Everybody has to stay with his own house’. Upon resettling, boundaries were placed around family units that had not existed previously in Africa. Now, women had to ‘live like you’re only you, just with me and my husband and the kids’. Participants explained how this dramatic cultural shift had ramifications for community connectedness, problem solving as a group, and child rearing. One woman described,

Here, it’s so different. I can be in the first floor [apartment]. The third floor, they don’t know me. They just meet to their door, “Hi, Hi.” You can have the neighbor. Just see he will come in. You see he’s [a] good person. I can say, “Hi, hi,” but it’s odd. It’s a big difference.

The stiffness and formality ascribed to social interactions in the US was analogous to their experiences with official infrastructures. One participant shared that ‘The first month was so hard … because when the people first come, [you] go to see the landlord for the house. You need to sign the documents … This is the agreement’. She continued,

We never had those agreements when we were living in Africa. [Laughter] You go in people’s houses. You rent the house. There is no agreement. There is nothing. You just say, ‘Oh, I want to rent the house. Okay, how much?’

The shift in perceived power dynamics between women and men sometimes led to a change in expectations regarding gender roles within families. While in Africa, the expectation was for women ‘to do everything in the house’, and men are expected to earn money for the family, ‘in America, women work 50/50 … The husband here in America is 50/50. Even the man can cook. Even the man can do [the] wash’.

Most importantly, however, immersion into a society with drastically different gendered expectations within the home led to conflict. One participant described that ‘when they come in America, [women] start to think like they are born here’. The more time African women spend in America, they suddenly ‘want [their] husband to start to do things he never do before’. Men are left feeling confused and often angry, not understanding why women suddenly expect everything to change.

Further, household tensions related to shifting gender norms in African versus US cultures were exacerbated for women seeking professional counselling. One woman explained that,

They [the counselors] are gonna just say, ‘Oh, that husband is abusing you.’ That is not the case when he was in Africa. We don’t know this kind of stuff that he’s abusing you. No, but when you come here, if you want to say, ‘I want to talk to someone’ I believe that something bad usually happens, and so that is the problem for women …

Finally, racism and ‘the problem of this Black killing’ in America was brought up frequently by participants as a new and unexpected part of American society. Being targeted for the colour of their skin was a new experience for women and their families, as for some, living in the US ‘is the first time learning that I am Black’. In Africa, women describe their identity as defined by ethnicity; to suddenly be subject to a new, foreign, and dangerous social phenomena was terrifying for them.

Participants had not anticipated targeted violence in the US ‘It’s the same thing which I ran from back [in my home country]’, one woman shared. ‘We ran, people being killed by others and when we arrived here now, [we] experience the same thing’. Another participant explained that with ‘watching the news on the TV of how the Black people are being killed’, her ‘happiness is changing somehow’ about being resettled in the US. Another described feeling like coming to America was ‘just a chance in life to get peace’, but now ‘it’s like … you leave your country to go to a new place, but you get the same thing. It’s no different … The news in America … . I don’t know why they kill people [here]’.

Women feared particularly for the lives of their sons, describing feeling ‘really scared’ and ‘always think[ing] about it’. One woman’s approach was to explain to her sons, ‘Hey, you were born and safe in America, but you need to feel like you don’t belong’. These feelings were exacerbated by the current political discourse surrounding refugees and immigrants, as well as Black American fears of the COVID-19 vaccine. Overall, the overt racism and general mistrust contributed to some women feeling dejected, like they do not belong within US society, inevitably asking themselves, ‘Will I ever belong?’

Social support from a range of community members can act as a bridge for newly resettled refugees to navigate the intricate landscape of US norms and systems

Whether mentorship came from other African refugees or US citizens met through work or resettlement agencies, participants referred to key relationships that helped them navigate the complexities of life in the US. Other African refugee women who had lived longer in the US were an ideal source of social support for many, as they could relate to their experiences while also providing guidance. One participant described support she received from an African refugee woman working for a local community-led organisation, sharing that,

[The] office, they help us a lot … when I just found [her], she just tell me if I need to go to see my doctor, I can just call her, and then she come pick me up and take me wherever I want to go, so that was easy when I found her, but before I found [her], oh, it was so hard.

Several participants described meaningful relationships they formed with women ‘from here’, or American women, whom they met at work. These mentors offered practical guidance and support through times of anxiety, as one participant stated, ‘It’s like I find my family’. Another participant shared,

I have a friend. That lady … she [is] helping me a lot … I was feeling that, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s better to go back [home],’ but she went, ‘Move forward. Move forward. Go ahead. Don’t think about that.’ She’s helping me so much. ‘You can learn … I was feel[ing] like, ‘Oh, my God. This country’s so hard to live.’ She show[ed] me that this country’s so easy to live … The more she [is] talking, the more I calm down.

You don’t know the American system. You are like a newborn when you come here. You have to start everything from zero. If you don’t have somebody who understand what you are going through, it’s like you are a nervous adult. You will never settle down.

Discussion

Through this community-engaged research, we used principles of grounded theory to reveal how mental health experiences among a sample of resettled African refugees in RI results from interactions between social support, African sociocultural norms, and US norms and systems. We also describe how meanings of mental health within the African refugee community vary from the US understanding of traditional PTSD, depression, and anxiety diagnoses.

A variety of facilitators and barriers to mental wellbeing are revealed when considering the intersection of social support, shared African cultural norms, and US norms and systems. Together, these intersections suggest several higher-level conclusions. First, social support and sense of community is engrained in the fabric of African society. Second, social support serves as a powerful antidote to poor mental health experiences. Third, many US systems are at odds with African sociocultural norms. Efforts to improve mental health experiences of this population require acknowledging each of these factors. Community-led organisations may themselves serve as interventions that promote resilience, as they naturally encompass community norms and are run by those with experience navigating US systems. The participants’ descriptions speak to how well-suited community organisations are to assisting women to have a healthy resettlement transition, to reinstate a foundation of social support and community, and to maximise their mental wellbeing in both the short and longer terms.

This work builds on and integrates several key areas within the refugee mental health literature. Here, we question what mental health means within this particular community and how it should be discussed. Our findings support previous work that advocates for thinking holistically about mental health outcomes following traumatic exposures, focusing on the experiences that are common to PTSD, depression and anxiety (Farhood et al., Citation2016; Goessmann et al., Citation2020; Greene et al., Citation2019), and establishing culturally relevant symptomologies associated with these mental health diagnoses (Betancourt et al., Citation2015). These findings suggest the importance of using an anthropological approach to understanding cultural meanings of mental health rather than focusing on medical diagnoses alone. Our findings also align with previous work that emphasises stressors during resettlement (e.g. unemployment, low income, language skills, changing family dynamics, acculturation, and social isolation) as significant contributors to refugee mental health (Birman & Tran, Citation2008; Bogic et al., Citation2015; Jorgenson & Nilsson, Citation2021; Mahajan et al., Citation2021).

These findings highlight the important role of community-led organisations – or other collectives that advocate for refugee wellbeing – in offering social support to refugee women to alleviate poor mental health. In particular, women’s lived experience of stressors introduced by US norms and systems are important factors associated with mental health. For many women, the mere presence of a community-led organisation may itself exist as an intervention promoting mental wellbeing, since it provides an accessible, culturally relevant institution in refugees’ communities. Recent studies echo the promise of social support to alleviate poor mental health among Congolese refugee women living in the US (Wachter & Gulbas, Citation2018), Syrian refugee women living in Canada (Mahajan et al., Citation2021), people who have developed PTSD after torture exposure (Gottvall et al., Citation2019), and refugee women in general (Greene et al., Citation2019; Hawkins et al., Citation2021; Idemudia & Boehnke, Citation2020). Balaam and colleagues advocate for the use of the volunteer sector to address the needs of refugee women and asylum seekers in the United Kingdom (Balaam et al., Citation2016). Further, social networks have recently been suggested as a possible effective alternative to formal mental healthcare among refugee women (Mahajan et al., Citation2021). Our findings argue for increased governmental support in the US for community-based and -led organisations; further, proven effective and acceptable community-led mental health interventions for resettled refugee communities should continue to be tailored to specific communities and explored as a reimbursable intervention (DiClemente-Bosco et al., Citation2023).

Although we believe that many aspects of our findings can be informative beyond this specific community, study replicability may be difficult due to the specificity of the community context (primarily English-speaking African refugee women resettled in RI). As the pandemic prevented in-person data collection, we found that non-English speaking women were hesitant to conduct phone interviews. However, English speaking women who had met the first author prior to the pandemic were willing to participate due to their established trust. Due to many non-English speaking women’s discomfort being interviewed over the phone, these findings are primarily indicative of experiences among women who are comfortable speaking English. Therefore, this study is limited in what it can contribute to our understanding of language and resettlement experiences. The need to conduct in-depth interviews over the phone further limited the data, as videoconferencing was not a feasible option for community members; facial expressions and certain non-verbal cues were therefore impossible to capture. Finally, the first author and lead researcher is not a member of the community, which may impact how findings are ultimately conveyed.

These findings illustrate ways that community-engaged approaches with refugee populations can enhance acceptability, feasibility, and rigour of public health research (Kraemer Diaz et al., Citation2015; Lindlof & Taylor, Citation2002). These findings would not have been possible without the in-depth formative research which took place throughout the many phases of CBPR described in this study. Our findings argue for the wider use of such approaches in developing US-based public health interventions, which tend to focus on specific outcomes, are often built from deterministic models from behavioural or medical sciences, and prioritise evaluation using quantitative measures. The methods presented here provide a framework for working with often hard to reach populations, and our findings indicate the richness and utility of qualitative data that can be attained through collaborative partnerships. Further, this study reinforces the idea that community-led organisations are uniquely suited to assist refugee women in their transition to life in the US in ways that can considerably improve mental health experiences. Future research should focus on bolstering these existing efforts, testing the effectiveness of such networks on improving mental health outcomes for resettled refugee women over time, and scaling up peer-led mental health support for refugees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The World Health Organization defines mental health as ‘a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community’ (WHO, Citation2022).

2 For this reason, we decided to take direction from the community members and refer to participants as ‘African’ on account of the importance of this shared identity and the role this played in their resettlement.

References

- Babatunde-Sowole, O., Power, T., Jackson, D., Davidson, P. M., & DiGiacomo, M. (2016). Resilience of African migrants: An integrative review. Health Care for Women International, 37(9), 946–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2016.1158263

- Balaam, M.-C., Kingdon, C., Thomson, G., Finlayson, K., & Downe, S. (2016). ‘We make them feel special’: The experiences of voluntary sector workers supporting asylum seeking and refugee women during pregnancy and early motherhood. Midwifery, 34, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.12.003

- Betancourt, T. S., Frounfelker, R., Mishra, T., Hussein, A., & Falzarano, R. (2015). Addressing health disparities in the mental health of refugee children and adolescents through community-based participatory research: A study in 2 communities. American Journal of Public Health, 105(S3), S475–S482. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302504

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Birman, D., & Tran, N. (2008). Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre- and postmigration factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109

- Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

- Byfield, J. A., Brown, C. A., Parsons, T., & Sikainga, A. A. (2015). Africa and world. Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, W., Hall, B. J., Ling, L., & Renzaho, A. M. (2017). Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9

- Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7, 2050312118822927. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

- DiClemente-Bosco, K., Neville, S. E., Berent, J. M., Farrar, J., Mishra, T., Abdi, A., Beardslee, W. R., Creswell, J. W., & Betancourt, T. S. (2023). Understanding mechanisms of change in a family-based preventive mental health intervention for refugees by refugees in New England. Transcultural Psychiatry, 60(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615221111627

- Farhood, L. F., Fares, S., Sabbagh, R., & Hamady, C. (2016). PTSD and depression construct: Prevalence and predictors of co-occurrence in a South Lebanese civilian sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 31509. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.31509

- Goessmann, K., Ibrahim, H., & Neuner, F. (2020). Association of war-related and gender-based violence with mental health states of Yazidi women. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2013418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13418

- Gottvall, M., Vaez, M., & Saboonchi, F. (2019). Social support attenuates the link between torture exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among male and female Syrian refugees in Sweden. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 19(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0214-6

- Greene, M. C., Rees, S., Likindikoki, S., Bonz, A. G., Joscelyne, A., Kaysen, D., & Tiwari, A. (2019). Developing an integrated intervention to address intimate partner violence and psychological distress in Congolese refugee women in Tanzania. Conflict and Health, 13(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0222-0

- Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. SAGE.

- Harrison, A., Short, S. E., & Tuoane-Nkhasi, M. (2014). Re-focusing the gender lens: Caregiving women, family roles and HIV/AIDS vulnerability in Lesotho. AIDS and Behavior, 18(3), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0515-z

- Hawkins, M. M., Schmitt, M. E., Adebayo, C. T., Weitzel, J., Olukotun, O., Christensen, A. M., & Dressel, A. (2021). Promoting the health of refugee women: A scoping literature review incorporating the social ecological model. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01387-5

- Henkelmann, J.-R., de Best, S., Deckers, C., Jensen, K., Shahab, M., Elzinga, B., & Molendijk, M. (2020). Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees resettling in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open, 6(4), e68. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.54

- Idemudia, E., & Boehnke, K. (2020). Viewpoints of other scientists on migration, mental health and PTSD: Review of relevant literature. In Psychosocial experiences of African migrants in six European countries (pp. 83–117). Springer International Publishing.

- Jankovic-Rankovic, J., Oka, R. C., Meyer, J. S., & Gettler, L. T. (2020). Forced migration experiences, mental well-being, and nail cortisol among recently settled refugees in Serbia. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113070

- Jorgenson, K. C., & Nilsson, J. E. (2021). The relationship among trauma, acculturation, and mental health symptoms in Somali refugees. The Counseling Psychologist, 49(2), 196–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000020968548

- Kiteki, B. (2016). The case for resilience in African refugees: A literature review and suggestions for future research. VITAS, 66, 1–21.

- Kraemer Diaz, A. E., Spears Johnson, C. R., & Arcury, T. A. (2015). Perceptions that influence the maintenance of scientific integrity in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 42(3), 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198114560016

- Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Lloyd Michener, M., Cook, J., Ahmed, S. M., Yonas, M. A., Coyne-Beasley, T., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2012). Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: Why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Academic Medicine, 87(3), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182441680

- Mahajan, S., Meyer, S. B., & Neiterman, E. (2021). Identifying the impact of social networks on mental and emotional health seeking behaviours amongst women who are refugees from Syria living in Canada. Global Public Health, 1–17.

- Meger, S. (2010). Rape of the Congo: Understanding sexual violence in the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 28(2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001003736728

- Nest, M. W., Grignon, F., & Kisangani, E. F. (2006). The Democratic Republic of Congo: Economic dimensions of war and peace. Lynne Rienner.

- Nolen, S. (2005). 'Not women anymore...': The Congo's rape survivors face pain, shame and AIDS.

- Omaha World-Herald. (2017). Rhode Island refugee resettlement. Omaha World-Herald.

- Peterman, A., Palermo, T., & Bredenkamp, C. (2011). Estimates and determinants of sexual violence against women in the Democratic Republic of Congo. American Journal of Public Health, 101(6), 1060–1067. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300070

- Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 294(5), 602–612. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.5.602

- QSR International. (2020). NVivo qualitative data analysis software version 12.

- Ramzy, L. M., Jackman, D. M., Soberay, A., & Pledger, J. (2017). Refugee resettlement in the U.S.: The impact of contextual factors on psychological distress. Universal Journal of Public Health, 5(7), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujph.2017.050703

- Scoglio, A. A., & Salhi, C. (2021). Violence exposure and mental health among resettled refugees: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(5), 1192–1208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020915584

- Siriwardhana, C., Ali, S. S., Roberts, B., & Stewart, R. (2014). A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Conflict and Health, 8(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-8-13

- Smigelsky, M. A., Gill, A. R., Foshager, D., Aten, J. D., & Im, H. (2017). “My heart is in his hands”: The lived spiritual experiences of Congolese refugee women survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 45(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2016.1197754

- Stark, L., Asghar, K., Yu, G., Bora, C., Baysa, A. A., & Falb, K. L. (2017a). Prevalence and associated risk factors of violence against conflict-affected female adolescents: A multi-country, cross-sectional study. Journal of Global Health, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010416

- Stark, L., Sommer, M., Davis, K., Asghar, K., Baysa, A. A., Abdela, G., & Falb, K. (2017b). Disclosure bias for group versus individual reporting of violence amongst conflict-affected adolescent girls in DRC and Ethiopia. PLoS One, 12(4), e0174741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174741

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). The basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. SAGE.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. SAGE.

- Tlapek, S. M. (2015). Women’s status and intimate partner violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(14), 2526–2540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514553118

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- UNHCR. (2020). DR Congo emergency: The UN refugee agency.

- UNHCR. (2023). Figure at a glance. Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html

- Vu, A., Adam, A., Wirtz, A., Pham, K., Rubenstein, L., Glass, N., Beyrer, C., & Singh, S. (2014). The prevalence of sexual violence among female refugees in complex humanitarian emergencies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Currents, 6.

- Wachter, K., & Gulbas, L. E. (2018). Social support under siege: An analysis of forced migration among women from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.056

- Wachter, K., Heffron, L. C., Snyder, S., Nsonwu, M. B., & Busch-Armendariz, N. B. (2016). Unsettled integration: Pre- and post-migration factors in Congolese refugee women’s resettlement experiences in the United States. International Social Work, 59(6), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872815580049

- Wallerstein, N., & Duran, B. (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7(3), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906289376

- World Health Organization. (2022). Mental health: Concepts in mental health. Retrieved November 7, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response