ABSTRACT

Women from low- and middle-income countries face challenges in accessing and utilising quality healthcare. Technologies can aid in overcoming these challenges and the present scoping review is aimed at summarising the range of technologies used by women and assessing their role in enabling Indian women to learn about and access healthcare services. We conducted a comprehensive search from the date of inception of database till 2022 in PubMed and Google Scholar. Data was extracted from 43 studies and were thematically analysed. The range of technologies used by Indian women included integrated voice response system, short message services, audio–visual aids, telephone calls and mobile applications operated by health workers. Majority of the studies were community-based (79.1%), from five states (60.5%), done in rural settings (58.1%) and with interventional design (48.8%). Maternal and child health has been the major focus of studies, with lesser representation in domains of non-communicable and communicable diseases. The review also summarised barriers related to using technology – from health system and participant perspective. Technology-based interventions are enabling women to improve awareness about and accessibility to healthcare in India. Imparting digital literacy and scaling up technology use are potential solutions to scale-up healthcare access among women in India.

Introduction

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), adopted in 2015, underline the importance of universal health coverage and access to quality health care to achieve overall health and wellbeing (Asma et al., Citation2020). SDG aimed to decrease gender gap in many scenarios including healthcare access and utilisation by 2030 (Mariani et al., Citation2017). Despite efforts made over last few decades, women face many challenges in accessing and utilising healthcare, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (United Nations, Citation2022). The COVID-19 pandemic slowed progress for women, and in many countries, their participation in healthcare reduced drastically. A 2020 study estimated that the indirect health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on income, nutrition and healthcare access could result in 24,000–113,000 additional maternal deaths and 417,000–1.8 million additional child deaths, in LMIC (Roberton et al., Citation2020).

A recent report has showcased the magnitude of excessive gender discrimination in health care access by women in India and has called for an urgent societal and governmental action to correct this scenario (Mahase, Citation2019). In India, traditionally, women have poorer health-seeking behaviour compared to their male counterparts, and often resort to no treatment or where possible, treatment limited to the confines of their home (Kapoor et al., Citation2019). There is a complex interplay of factors such as poor health literacy, economic dependence as a consequence of lack of education, culturally prescribed gender roles in the prevailing patriarchal system and inaccessibility of basic health care, that further increases the gender disparity in healthcare access in India (Das et al., Citation2018; Faizi & Kazmi, Citation2017; Reddy et al., Citation2020). While technology can partly bridge gender inequality in accessing healthcare through digital solutions, there is a marked disparity in use of technology between men and women in India. Indian women are less likely to own a mobile phone and use internet by 15% and 33% respectively, compared to men (Nikore, Citation2021). The existing gender gap worsens with increasingly sophisticated digital technology, such as smartphones, where ownership rates of these phones were 14% in women, compared to 37% in men, in 2019. National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-4 and NFHS-5 have reported that rural women were at greater disadvantage in terms of digital access compared to their urban counterparts and probable reasons could be poor digital literacy, social norms and prohibitive costs of digital devices and data package, further narrowing down their opportunities to access digital technology (James et al., Citation2021; Tyers et al., Citation2021; World Bank Group, Citation2021). This gender disparity in use of technology deprived women of access to healthcare through virtual platform, despite multi-fold increase in telehealth consultations in India during COVID-19 era (Nikore, Citation2021).

Recent NFHS-5 data showed underachievement in terms of indictors of women empowerment in India, with only 32% of currently married women representing workforce, of which 15% have worked without being paid. Further, decisions about spending of women’s earnings as well as their healthcare were still made by husbands in 14% and 17% of families, respectively (James et al., Citation2021). Empowering women with technological aids can help them gain autonomy and make strategic life choices to overcome gender bias and achieve access to healthcare (Mackey & Petrucka, Citation2021; Nasrabadi et al., Citation2015). Programmes such as ‘mMitra’, ‘Kilkari’, ‘Arogya Sakhi’ and ‘moderately underweight children (MUW)’ have been implemented in several states in India over last decade to leverage mobile-based technology use among women to access information on preventive health and utilise health services (ARMMAN, Citationn.d.). Evidence from certain geographies report the impact of technologies in improving health literacy and health outcomes among women, thereby advancing reduction in mortality among pregnant women and children at the national level (ARMMAN, Citationn.d.; Modi et al., Citation2019; Murthy et al., Citation2019). With rapid expansion of smart phone coverage in population recently and reduction in internet charges in future, the use of technology is identified to have a greater potential in improving health outcomes among women (Abbas, Citation2021; Krithika, Citation2021). At this juncture, a situational analysis of various technology platforms that are in use by women to access various health services in India is warranted to support policy decisions on choosing appropriate technologies that can have potential impact in addressing key health issues of women in India. A scoping review format was deemed fit to determine the scope of literature with regard to above and provide a broad overview of evidence (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018). Our scoping review aimed at identifying the range of technologies used by women to access healthcare, understanding their scope and assessing their impact in enabling Indian women to learn about and access various healthcare services – with particular focus on maternal, reproductive and child health; communicable and non-communicable diseases across all levels of healthcare. This review also reports barriers faced by women while using these technologies in a resource constrained settings like India.

Methods

A scoping review of the available evidence was conducted following the Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This review is presented according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (see Appendix 1). Briefly, the review followed five steps: research question identification, identification of relevant studies, selecting studies based on predefined eligibility criteria, synthesising evidence and reporting the findings. The protocol for this review was registered in open science forum (OSF) registries (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3CAZ6).

Theoretical framework considered in this review

This review considered its study population as adult biological women including women of elderly age group, to understand technology utilisation in accessing health care by women. Studies pertaining to transgender or transwomen were not included in this review, as our preliminary search showed obtaining data pertaining to this subgroup is difficult. Gender disparity in accessing healthcare services in Indian context is shown to exist mainly at household level with a bias in prioritising healthcare spending for women compared to men and difficulty in accessing nearest health facilities owing to their greater distance (Dupas & Jain, Citation2021). To overcome these shortcomings, technology can serve as an approach in universalising healthcare among women in India through improving access to health services, improving quality of service delivery and improving diagnosis, prevention, treatment and care for diseases (Chaudhuri et al., Citation2022). Optimal penetration of technology such as mobile-based ones in the community can help women learn about and access healthcare services. Thus empowerment of women is theorised as a process where women gain capacity to exercise personal choice related to healthcare, after acquiring sufficient health information and knows-how to access health services through technologies. This individual empowerment can contribute to collective gain at community level in terms of better health indicators (Huis et al., Citation2017).

Search strategy

We conducted an exhaustive literature search of each database from inception to the date of search (3rd February 2022) that included – the MEDLINE via PubMed and Google Scholar using the search terms under four broad headings – ‘technology’, ‘access to healthcare’, ‘women’ and ‘India’, as described in Supplementary file 1. The search strategy was built with the inputs from librarian and subject experts. This review considered ‘technology’ to include wide range of terms pertaining to mHealth, telemedicine, remote sensing technologies, wearable electronic devices, social media and health information system to account for various technologies used by women. Search terms for ‘access to healthcare’ included key words such as availability, affordability, approachability and access, to represent ‘access’; and preventive, promotive, curative, treatment and rehabilitative services to cover dimension of ‘health services’. Further, search terms for ‘health services’ were expanded to include key terms covering maternal, reproductive and child health; communicable and non-communicable diseases across various levels of healthcare.

Screening process and criteria for study selection

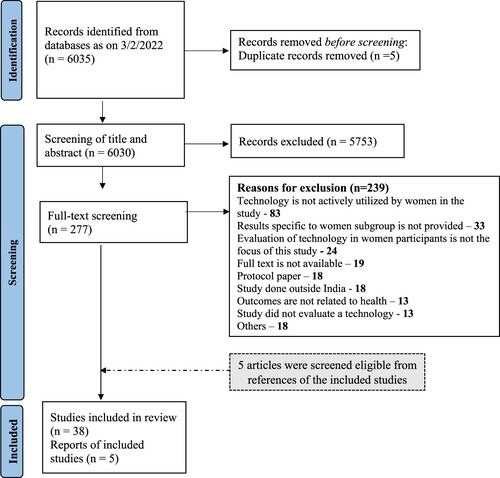

The search results of 6035 records were imported into a literature review software, DistillerSR and five duplicate citations were removed. First step involved title and abstract screening, where four review authors (MS, GM, NM and MK) screened the articles based on following criteria – if the article reported use of technology and provided information pertaining to any health-related outcome. The full texts of the articles were retrieved and reviewed if the relevance could not be ascertained by screening the title and abstract. In the second step, 277 articles found eligible in title and abstract screening were subjected to full text screening independently by two groups of review authors (group 1: MS & GM and group 2: NM & MK). Full texts were considered eligible for inclusion if they reported active utilisation of technology by women – either operated by women directly or with the help of family members or frontline health workers (FLHWs), and that were translated into measurable health outcomes specific to women. Additionally, articles that had both men and women as study participants were included if they reported health outcomes specific to the women subgroup. We included primary research (observational and experimental designs), letters and grey literature (unpublished studies, dissertation abstracts, reports). Published opinion pieces, correspondence, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, studies reporting women and/or girls outside India, non-English literature and articles without full-text were excluded. Disagreements while screening full texts were resolved through discussion between the authors of each group. Initially, 38 full-text articles were included for data extraction, with an additional 5 articles that were included after screening references of the included articles. Steps of screening process along with reasons for exclusion were provided in PRISMA flow diagram ().

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the scoping review (Page et al., Citation2021).

Data extraction

Three review authors (MS, GM and NM) extracted data from 43 articles using a pre-designed data abstraction form in DistillerSR software, after pilot testing of the form using a sample of included studies.

Following characteristics were extracted from each study:

Administrative details: Name of the first author and year of publication

Study specific details: Title of the study, type of study, aims and objectives of the study, study setting (state; urban or rural; hospital (including level of care) or community), study participants (involves women and/or girls only, or women and/or girls form a subgroup of the overall study participants), sample size

Participant specific information: Type of study participants (women or mothers with their children and involvement of family members), age and morbidity status

Intervention specific details: Type of intervention, point of intervention delivery, need for trained healthcare workforce, choice of healthcare worker for intervention delivery, intervention duration and study comparison group

Study outcomes: Outcomes measured, method of outcome measurement, impact of the intervention on health outcomes, determinants (both facilitators and barriers) for technology utilisation or non-utilisation

Study recommendations.

Study characteristics of included articles are summarised in Table S1 of Supplementary File 2. Data analysis was performed by thematic analysis, where findings from each study were further categorised into subthemes and broader themes.

Role of funders: Funders of this study have no role in conduct of this review, data analysis or publication of the results.

Results

Synthesis of evidence retrieved from included articles revealed range of technologies used by women. This included short message services (SMS), interactive voice response system (IVRS), phone calls or helpline services, exposure to mass media such as radio and television, telemedicine services, audio–visual (AV) aids with assistance of Frontline health workers (FLHWs) and use of mHealth or web-based technologies operated by FLHWs. Various health outcomes reported in the studies were broadly classified under themes such as maternal health, child health, mental health, chronic diseases and communicable diseases.

Study characteristics

This review synthesised data from 43 publications which were done across India, predominantly over last decade evaluating technology use in women’s health. 26 (60.5%) out of 43 articles were based on studies done in 5 Indian states; 8 from Maharashtra, 5 each from Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, and 4 each from Delhi and Karnataka. A lack of representation of studies is noted from Jammu & Kashmir, north-eastern states, West Bengal, Odisha, Rajasthan and Kerala. Most of the published articles (34 out of 43) were based on community-based studies, with three-fourth of these being done in rural settings. Quasi-randomised and randomised controlled trials were most adopted study designs, in 21 out of 43 articles. Healthy women were study participants in most of the studies, except for seven studies that had women participants with co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, HIV and psychiatric morbidities. Women between 18 and 49 years were participants in most of the studies, with lack of representation of data from elderly women (see Table S2).

Type of technologies used

Studies have reported wide range of technologies being utilised by women. Nearly half of the published articles (23 out of 43) reported the use of mobile-based technologies that facilitated one-to-one channel of communication between healthcare provider and women. Of these, 10 articles reported use of short message services (SMS) (Chandra et al., Citation2014; Khokhar, Citation2009; Kumar et al., Citation2021; Murthy et al., Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2018; Santra et al., Citation2021; Seth et al., Citation2018; Shinde et al., Citation2018; Shukla et al., Citation2020; Suryavanshi et al., Citation2020), 14 articles utilised interactive voice response system (IVRS) (Chakraborty et al., Citation2021; Johri et al., Citation2020; Mohan et al., Citation2021; Murthy et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Scott et al., Citation2021; Seshu et al., Citation2021 ) and phone calls or helpline services (Chandra et al., Citation2014; Gulati et al., Citation2020; Kannure et al., Citation2021; Kulathinal et al., Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2018; Ragesh et al., Citation2020; Santra et al., Citation2021). Seven articles reported using AV aids for health education by FLHWs, either on a one-to-one basis by showing videos to women or by playing audio clips in small group meetings with women participants (Adhisivam et al., Citation2017; Hiremath et al., Citation2020; Kalokhe et al., Citation2021; Karri et al., Citation2022; Ramagiri et al., Citation2020; Suryavanshi et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2021). Exposure to mass media such as radio and television was noted in five articles where health education messages pertaining to reproductive health were broadcasted to communities (Dhawan et al., Citation2020; Fatema & Lariscy, Citation2020; Lam et al., Citation2019; Pakrashi et al., Citation2022; Speizer et al., Citation2014). Notably, nine articles reported use of mHealth or web-based technologies by FLHWs such as ASHAs, AWW and/or staff of primary health centres (PHC) to provide health education and track preventive, screening and curative services offered to beneficiaries at community level (Bhatt et al., Citation2018; Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Choudhury et al., Citation2021; Ilozumba et al., Citation2018; Maulik et al., Citation2017; Modi et al., Citation2019; Pant Pai et al., Citation2019; Prinja et al., Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2019). Telemedicine platform has been used in three studies which enabled women in remote locations to reach healthcare providers for healthcare, contraceptive services and new-born screening for hearing loss (Chourasia & Tiwari, Citation2012; Lo, Citation2011; Ramkumar et al., Citation2013) ().

Table 1. Various technologies used by women across studies in India (n = 43 articles).

Health outcomes assessed

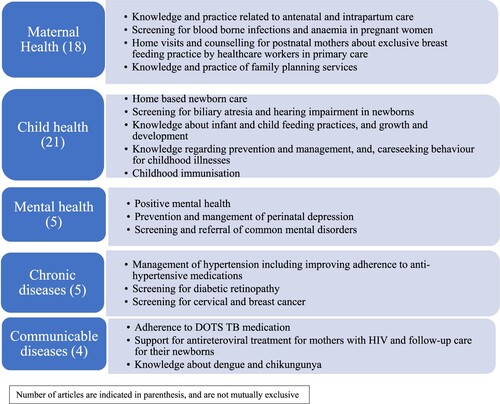

Broadly, five themes emerged while grouping health outcomes reported across studies. Maternal and child health were two major themes covering key outcomes reported in 18 and 21 articles, respectively. Mental health, chronic diseases and communicable diseases were other themes identified, which included fewer number of articles ().

Figure 2. Thematic analysis of health outcomes assessed in studies among women in India (n = 43 articles).

Maternal health

Technologies such as IVRS, SMS, mass media, telemedicine and mHealth application as a job aid to FLHW have been utilised to improve maternal health in India. The use of specific technology in a setting has been largely driven by socioeconomic status and maternal literacy of study population. The main outcomes pertaining to maternal health are improvement in knowledge and practice regarding antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care, and family planning services. Early detection of anaemia and blood-borne infections was other important maternal health outcomes reported. IVRS platform has been extensively studied in rural Madhya Pradesh under Kilkari project where pregnant mothers received health education messages in Hindi regarding nutrition, supplementation of calcium, iron and folic acid, pregnancy care, family planning and child care (Mohan et al., Citation2021; Scott et al., Citation2021). Kilkari health messages were delivered as 72 once weekly voice calls to mothers between 18 weeks of pregnancy until first-year birthday of child and contents constituted 10% on pregnancy care, 16% on family planning, 13% on infant feeding and 11% on child immunisation, predominantly (LeFevre et al., Citation2019). Currently, Kilkari programme has been scaled up to 18 states and union territories with a reach over 24.6 million women subscribers (ARMMAN, Citationn.d.). In another study in urban Mumbai, IVRS and SMS have been found useful in improving knowledge and practice related to ANC care such as receiving tetanus toxoid immunisation [OR: 1.6 (95% CI: 1.1–2.4)], consulting doctor in case of spotting or bleeding [OR: 1.7 (95% CI: 1.1–2.8)] and for delivery in hospital facility [OR: 2.5 (95% CI: 1.5–4.4)], compared to mothers who received standard of care (Murthy et al., Citation2020). Population-based studies such as ImTeCHO, ICT-CCS and ReMiND have evaluated translational value of providing mHealth application as a job aid to FLHWs in improving maternal health outcomes (Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Modi et al., Citation2019; Prinja et al., Citation2017). The use of mHealth application enabled FLHWs to schedule and track beneficiary home visits, thereby showing an increase in number of home visits to ANC and PNC mothers by 15.7% and 12%, respectively compared to mothers who received standard of care. FLHWs used mHealth platform to counsel and provide health education to mothers using its AV features and easily accessed guided protocols for screening and referral of maternal illnesses identified during their home visits (Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Modi et al., Citation2019; Prinja et al., Citation2017). Television exposure, having dedicated toll free helpline services and telemedicine provision centres in communities, was useful for the transmission of knowledge and improving practice related to family planning services among women in rural communities (Kulathinal et al., Citation2019; Lo, Citation2011; Pakrashi et al., Citation2022; Speizer et al., Citation2014).

Child health

Technologies used in studies based on child health included SMS, IVRS and mHealth application, provided as a job aid to FLHWs. Key outcomes related to child health include improvement in awareness regarding home based new-born care, knowledge regarding infant and child feeding practices, growth and development during childhood and immunisation practices. Lactation counselling through daily SMS reminders and weekly calls to postnatal mothers have been found effective in increasing rate of exclusive breast feeding at 6 months to 97% in intervention group, compared to 49% in control group (Patel et al., Citation2018). SMS-based health education about early childhood development and nutrition provided at the level of study families and FLHWs in study district has promoted discussions at community about best child care practices and facilitated overall reduction in undernutrition and stunting by 19% and 9% respectively, in the intervention area compared to control area (Kumar et al., Citation2021). The use of IVRS and SMS platform for improving knowledge about childhood immunisation and sending out vaccination reminders to parents was effective and reported an increase in fathers’ knowledge on childhood immunisation [OR: 1.2 (95% CI: 1.0–1.5)], and improvement in timeliness of childhood immunisation (Chakraborty et al., Citation2021; Seth et al., Citation2018). mHealth application as a job aid to FLHWs facilitated effective tracking and improvement in practices related to home-based new-born care, infant and child feeding, and childhood immunisation, by increasing coverage of home visits and counselling services provided by FLHWs in the community (Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Modi et al., Citation2019; Prinja et al., Citation2017; Shah et al., Citation2019).

Mental health

Only five articles have reported mental health outcomes that were evaluated through platforms such as – helplines, IVRS, SMS, AV aid and mHealth application. The synthesis of evidence from studies pertaining to mental health showed that positive mental health, prevention and management of perinatal depression and improving knowledge about screening and referral of common mental disorders as important health outcomes. Helpline services hosted by trained counsellors were adopted in two studies, where a study among postnatal mothers with psychiatric illness reported effective use of helpline for enquiring broad range of problems such as medications, sleep problems, domestic violence, and infant and child feeding practices (Chandra et al., Citation2014; Ragesh et al., Citation2020). In another study ‘SMS for mental health’, young women received SMS messages on positive mental health tip and information about the availability of helpline services as part of intervention. Of these, 63% of women reported to have utilised helpline services for seeking mental health services during study period and stated that intervention was supportive for improving their mental wellness (Chandra et al., Citation2014). A rural community-based study adopted ‘SMART’ – mHealth application, which is a technology-based intervention package and was tested to deliver mental health services in the community by constituting a linkage between ASHAs and PHC staff for screening, referral and management of people with common mental disorders in community. As a part of this study, IVRS messages were also sent to participants who screened positive for mental disorders to motivate them to continue the treatment in addition to multimedia-based stigma reduction campaigns that were conducted in communities. This study demonstrated that technology use has increased screening and management for common mental disorders among women of rural communities (Maulik et al., Citation2017).

Chronic diseases

Technology use for chronic diseases was reported in the five studies for screening and management of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetic retinopathy and cancer in women. Health outcomes related to chronic diseases included improving treatment adherence to anti-hypertensive medications and screening services for diabetic retinopathy, cervical and breast cancer in community. Of the two studies based on blood pressure management, one study utilised telephone services for providing health education and reminders for follow-up clinic visits to participants with hypertension, and it was found that better blood pressure was achieved among women following intervention (Kannure et al., Citation2021; Shukla et al., Citation2020). In the other study, SMS reminders for blood pressure medications were sent to participants and 62% increase in adherence to medication compared to baseline was reported (29). One of the few studies done among elderly women found that health education delivered through videos were two times more effective than pamphlets to motivate women to get screened for diabetic retinopathy (Ramagiri et al., Citation2020). There was a single study that concluded a negative result, where mHealth application, when provided as a job aid to FLHWs for screening cancers in community did not improve treatment rates among women who were screened positive for cervical or oral cancer, compared to the modality of routine primary care services offered by FLHWs (Bhatt et al., Citation2018).

Communicable diseases

Four studies have utilised technology to address health outcomes related to tuberculosis, HIV, dengue and diarrhoeal illness in children. Outcomes reported in the domain of communicable diseases included improving adherence to anti-tuberculosis medication and anti-retroviral treatment and knowledge about prevention of dengue and chikungunya. In a study, mothers with HIV who received SMS reminders for follow-up visits and health education through AV aid were twice as likely to practice exclusive breastfeeding and adhere to early infant diagnosis for HIV by 6 weeks, compared to mothers who received standard of care, and thereby resulting in better retention of mother and baby in HIV care (Suryavanshi et al., Citation2020). SMS and phone call-based reminders to women with tuberculosis reported 5% increase in adherence to DOTS medications in intervention group compared to control group that showed an increase of only 2% (Santra et al., Citation2021) ().

Table 2. Mapping of various technologies to health outcomes assessed in studies done among women in India.

Barriers and recommendations

Barriers reported in the studies are – technology related, issues at field level, those pertaining to participant’s knowledge and attitude while adapting to newer technologies and, challenges posed by participants’ families while women accessed these technologies. Technology related barriers included poor network coverage in study areas resulting in non-delivery of messages or calls to participants and other technical glitches related to hardware and software of the mobile applications (Bhatt et al., Citation2018; Kumar et al., Citation2021; Modi et al., Citation2019). Field level barriers were encountered among FLHWs, who reported a perceived difficulty to adapt to newer technologies and faced increased job responsibilities while having to serve in an already overburdened health system (Carmichael et al., Citation2019; Modi et al., Citation2019). Knowledge barriers such as poor literacy of women and linguistic challenges limited the penetration of health messages to participants (Hiremath et al., Citation2020; Kumar et al., Citation2021; Ragesh et al., Citation2020; Scott et al., Citation2021). Additionally, reluctance among participants in adapting to healthy practices that were discordant to their traditional beliefs further limited achieving health outcomes despite of successful technology penetration (Lo, Citation2011; Scott et al., Citation2021). Having to share mobile phones with family members, being financially dependent on husbands to recharge their mobile phones and lack of autonomy amongst women in making decisions pertaining to their health were challenges that participants faced at family level (Chakraborty et al., Citation2021; Chandra et al., Citation2014; Ilozumba et al., Citation2018; Kannure et al., Citation2021; Mohan et al., Citation2021; Seshu et al., Citation2021; Suryavanshi et al., Citation2020). Recommendations provided in studies to overcome technology and field related barriers included – provision of adequate training to staff while introducing newer technologies, and having a single application that allows data capture of various health outcomes in a comprehensive manner (Bhatt et al., Citation2018; Modi et al., Citation2019). The inclusion of photos or videos during health education sessions among populations with lower literacy was suggested to overcome participant related barriers (Bhatt et al., Citation2018; Dhawan et al., Citation2020). Studies also advised tailoring health messages as per norms of the community based on real time feedback during the course of the intervention (Mohan et al., Citation2021; Scott et al., Citation2021) ().

Table 3. Barriers encountered while using technologies by women and recommendations provided in the studies.

Discussion

This scoping review serves as a synthesis of evidence on technology utilisation in achieving women’s health exclusively from an Indian context. This review adds to context-specific findings from the literature based on India and supplements to the body of evidence from an already review synthesised from a global perspective (Mackey & Petrucka, Citation2021). This review synthesised evidence from 43 articles published between 2009 and 2022, listing out various technologies accessed by Indian women and health outcomes that were attained and the facilitators and barriers to their use. Technologies have been useful in improving healthcare access for women in India by serving as a medium for the transmission of health-related information as well as in assisting for the management of specific diseases. Fewer studies have documented that technology based on telemedicine helped women come into contact with health systems by overcoming physical barriers to access health services. Mirroring India’s priority to reduce maternal and under-five mortality as a part of millennium development goals and SDG, the major focus of studies included in this review has been to address maternal and child health related outcomes with the help of technology driven solutions.

This review found that mobile-based technologies (such as IVRS, SMS and helplines), telemedicine platforms and FLHW-operated mHealth applications were frequently used to offer continuum of care in the field of maternal and child health. Similar to findings of this review, a systematic review from Ethiopia has reported the predominant use of mHealth applications, calls, SMS, information and communication technology, and telemedicine in their country to address maternal and child health related health priorities. Furthermore, studies in Ethiopia have also described technologies related to artificial intelligence and cloud-based applications for the screening of diseases and diagnosis, which underscores the possibility of exploring such technologies in Indian setting as well in future studies (Manyazewal et al., Citation2021).

Studies included in this review aimed to improve ANC and PNC services, with specific focus on maternal knowledge and practice related to ANC attendance, maternal immunisation, micronutrient supplementation, facility-service utilisation and contraception services via technological aid. Future studies could focus on investing technologies to address pregnancy related complications such as gestational diabetes, pregnancy induced hypertension and heart disease complicating pregnancy in India. Taking inputs from developed countries, India must scale up technology utilisation in maternal health that are based on advanced RMNCH application, sensors and wearable-based interventions, which can offer diverse functionalities for mothers, instead of simple algorithm-based SMS interventions that focus only on health education and promotion (Chen et al., Citation2018). Studies related to child health in this review demonstrated successful utilisation of IVRS and SMS platform for knowledge dissemination regarding infant and child feeding practices and sending out reminders to parents for increasing the coverage of childhood immunisation. This finding ties well with evidence from Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, Asia-Pacific and southern Asia, where the effectiveness of these platforms has been evaluated in increasing immunisation coverage in children (Atnafu et al., Citation2015; Bossman et al., Citation2022; Kabongo et al., Citation2021).

This review identified very few studies addressing other health challenges such as tuberculosis, HIV and chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cancer and mental illnesses among women with the help of technology. While India is moving towards the goal of eliminating tuberculosis in near future, it is important to scale up patient centric approaches using digital technologies such as digital pill boxes, ingestible sensors, smart phone-based technologies and video assisted DOTS therapy, compared to traditional DOTS, for achieving better medication adherence and treatment outcomes among women (Subbaraman et al., Citation2018). With regard to studies that evaluated blood pressure control as an outcome in this review, the utilisation of technology was limited only to SMS and phone calls for improving adherence to medications and follow-up clinic visits in women. Studies from sub-Saharan Africa have used technology to establish linkages between healthcare provider and patients using bluetooth enabled devices to transmit information on blood pressure recordings and medication intake of patients to healthcare providers, for further follow-up (Kabongo et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, wearable devices enable real-time monitoring of blood pressure, glucose, daily exercise, diet, heart rate and weight to provide tailored health recommendations to patients with non-communicable diseases and have been tested in high income countries. While it is ambitious in our context to implement advanced technologies based on wearable devices as demonstrated in high income countries, it is still possible that these approaches would benefit subset of Indian women belonging to higher socio-economic status, if tested effective (Bossman et al., Citation2022).

This review also found limited utilisation of technology for cancer care for women in India. The focus of these studies has been limited to improving cancer screening using technologies, but has failed to address deficiencies in of cancer treatment, rehabilitation and palliation. Further studies among cancer patients can explore the possibility of establishing effective digital counselling environment by linking them to health counsellor or clinicians for self-management support and utilise mobile-based technologies for improving adherence to cancer medications and quality of life among women in Indian setting (Huang et al., Citation2022; Moradian et al., Citation2018).

This review shows possibility for diversifying technology use by women in India, in addition to increasing their geographic coverage and population outreach of these technologies. Parallely, at the societal level, women need to be empowered to use these technologies effectively. Major setbacks that limited effective use of technology by women, as identified in this review were poor digital literacy, lack of sole ownership of mobile phones, community norms that limited women’s access to digital technologies, threats to their safety and higher costs incurred by women while using mobile-based technologies. Barriers reported in this scoping review is similar to a recent review based on global literature that reported privacy, confidentiality, security concerns and sociocultural challenges to be key concerns women face while using technologies pertaining to healthcare (Moulaei et al., Citation2023). Potential solutions to overcome some of these technology related barriers among women are improving awareness, offering skill-based training, adopting user-friendly design of technologies and providing incentives for using technologies (Moulaei et al., Citation2023).

In the Indian context, improving digital literacy among women is a key element of focus and literature has provided examples based on field experiences from certain geographies in India (Tyers et al., Citation2021). This include establishing internet kiosks, telecentres and community resource centres in the locality so that women can access these centres for digital outreach and training. Establishing community liaison is an important strategy, wherein women, along with their family members, can acquire digital literacy from community workers or through peer educators, as evidenced in ‘Internet Saathi’ and ‘iSocial Kallyani’ programmes. Another initiative that can be planned at government level for empowering women to access technology would be free distribution of phones and providing data access for female family heads of underprivileged societies, as piloted in Chhattisgarh state under ‘Sanchaar Kranti Yojana’ (Tyers et al., Citation2021).

Technology expansion in a resource-limited settings like India is accompanied with important challenges pertaining to sustained funding support for such technologies, participant’s data security and other cybersecurity issues with data platform. With women in India representing vulnerable section of the society, particularly owing to their limited digital literacy, there is a strong emphasis on building-in cybersecurity measures into health-related technologies. Crucial solutions to address cybersecurity threats at health system level include applying firewalls against cyberattacks, restrict technologies and devices used by health staff with security regulations, applying multifactor authentication, improve staff awareness pertaining to cybersecurity and developing strong culture of cyber vigilance (He et al., Citation2021). At country level, there is a need for policies and regulations to mitigate cybersecurity threats at various levels such as guiding manufacturers to become more security-minded while designing medical devices (He et al., Citation2021).

Strengths of this review include the use of an exhaustive search strategy, formulated in collaboration with an experienced healthcare research librarian and evaluation of eligibility of full-texts independently by more than one reviewer. Limitations of this review include the exclusion of studies that used technologies and reported health outcomes, yet did not report results for women as a subgroup and exclusion of literature in languages other than English. Although a comprehensive number of records were identified from two databases in our review, possibility of missing few relevant studies from other databases exists.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified a wide range of technologies such as integrated voice response system, short message services, audio–visual aids, telephone calls and front line health worker-operated mobile applications, as the predominant technologies that women used in India to access healthcare. Information on prevention and health promotion was transmitted through these technologies to address predominantly maternal and child health, followed by non-communicable and communicable diseases under a limited scope. Imparting digital literacy and improving access to technology among women are potential solutions to empower women in achieving better access to healthcare in India.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (109.2 KB)Acknowledgement

This article has been written as part of the research for the Lancet Citizens’ Commission on Reimagining India’s Health System. The Lancet Commission has received financial support from the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute, Harvard University; Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore; Azim Premji Foundation, Infosys; Kirloskar Systems Ltd.; Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd.; Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies; and Serum Institute of India. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Lancet Citizens’ Commission or its partners. Authors extend their acknowledgement to Mrs. Vasumathi Ganesh from QMed foundation for her guidance in finalising the search terms in the databases and also Dr Dipinwita Sengupta for her technical support during conduct of this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abbas, M. (2021, October 26). India’s growing data usage, smartphone adoption to boost Digital India initiatives: Top bureaucrat. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/indias-growing-data-usage-smartphone-adoption-to-boost-digital-india-initiatives-top-bureaucrat/articleshow/87275402.cms

- Adhisivam, B., Vishnu Bhat, B., Poorna, R., Thulasingam, M., Pournami, F., & Joy, R. (2017). Postnatal counseling on exclusive breastfeeding using video – Experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital, south India. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 30(7), 834–838. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2016.1188379

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- ARMMAN. (n.d.). Helping mothers and children. https://armman.org/

- Asma, S., Lozano, R., Chatterji, S., Swaminathan, S., de Fátima Marinho, M., Yamamoto, N., Varavikova, E., Misganaw, A., Ryan, M., Dandona, L., Minghui, R., & Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Monitoring the health-related Sustainable Development Goals: Lessons learned and recommendations for improved measurement. The Lancet, 395(10219), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32523-1

- Atnafu, A., Bisrat, A., Kifle, M., Taye, B., & Debebe, T. (2015). Mobile health (mHealth) intervention in maternal and child health care: Evidence from resource-constrained settings: A review. The Ethiopian Journal of Health and Development, 29(3), 137–196.

- Bhatt, S., Isaac, R., Finkel, M., Evans, J., Grant, L., Paul, B., & Weller, D. (2018). Mobile technology and cancer screening: Lessons from rural India. Journal of Global Health, 8(2), 020421. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.020421

- Bossman, E., Johansen, M. A., & Zanaboni, P. (2022). mHealth interventions to reduce maternal and child mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Global Women's Health, 3, 942146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.942146

- Carmichael, S. L., Mehta, K., Srikantiah, S., Mahapatra, T., Chaudhuri, I., Balakrishnan, R., Chaturvedi, S., Raheel, H., Borkum, E., Trehan, S., Weng, Y., Kaimal, R., Sivasankaran, A., Sridharan, S., Rotz, D., Tarigopula, U. K., Bhattacharya, D., Atmavilas, Y., Pepper, K. T., … Darmstadt, G. L., Ananya Study Group. (2019). Use of mobile technology by frontline health workers to promote reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and nutrition: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Bihar, India. Journal of Global Health, 9(2), 0204249. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.020424

- Chakraborty, A., Mohan, D., Scott, K., Sahore, A., Shah, N., Kumar, N., Ummer, O., Bashingwa, J. J. H., Chamberlain, S., Dutt, P., Godfrey, A., & LeFevre, A. E., Kilkari Impact Evaluation Team. (2021). Does exposure to health information through mobile phones increase immunisation knowledge, completeness and timeliness in rural India? BMJ Global Health, 6(Suppl. 5), e005489. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005489

- Chandra, P. S., Sowmya, H. R., Mehrotra, S., & Duggal, M. (2014). ‘SMS’ for mental health – Feasibility and acceptability of using text messages for mental health promotion among young women from urban low income settings in India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 11, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.008

- Chaudhuri, A., Biswas, N., Kumar, S., Jyothi, A., Gopinath, R., Mor, N., John, P., Narayan, T., Chatterjee, M., & Patel, V. (2022). A theory of change roadmap for universal health coverage in India. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1040913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040913

- Chen, H., Chai, Y., Dong, L., Niu, W., & Zhang, P. (2018). Effectiveness and appropriateness of mHealth interventions for maternal and child health: Systematic review. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 6(1), e7. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8998

- Choudhury, A., Asan, O., & Choudhury, M. M. (2021). Mobile health technology to improve maternal health awareness in tribal populations: Mobile for mothers. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(11), 2467–2474. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab172

- Chourasia, V. S., & Tiwari, A. K. (2012). Implementation of foetal e-health monitoring system through biotelemetry. International Journal of Electronic Healthcare, 7(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEH.2012.048668

- Das, M., Angeli, F., Krumeich, A. J. S. M., & Schayck, V. O. C. P. (2018). The gendered experience with respect to health-seeking behaviour in an urban slum of Kolkata, India. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0738-8

- Dhawan, D., Pinnamaneni, R., Bekalu, M., & Viswanath, K. (2020). Association between different types of mass media and antenatal care visits in India: A cross-sectional study from the National Family Health Survey (2015–2016). BMJ Open, 10(12), e042839. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042839

- Dupas, P., & Jain, R. (2021). Women left behind: Gender disparities in utilization of government health insurance in India. Stanford - King Centre on Global Development. https://kingcenter.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj16611/files/media/file/wp1090_0.pdf

- Faizi, N., & Kazmi, S. (2017). Universal health coverage – There is more to it than meets the eye. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 6(2), 169–170. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_13_17

- Fatema, K., & Lariscy, J. T. (2020). Mass media exposure and maternal healthcare utilization in South Asia. SSM – Population Health, 11, 100614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100614

- Gulati, S., Shruthi, N. M., Panda, P. K., Sharawat, I. K., Josey, M., & Pandey, R. M. (2020). Telephone-based follow-up of children with epilepsy: Comparison of accuracy between a specialty nurse and a pediatric neurology fellow. Seizure, 83, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2020.10.002

- He, Y., Aliyu, A., Evans, M., & Luo, C. (2021). Health care cybersecurity challenges and solutions under the climate of COVID-19: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e21747. https://doi.org/10.2196/21747

- Hiremath, P., Chakrabarty, J., & Sequira, L. (2020). Video assisted education on knowledge and practices of house wives towards prevention of dengue fever at Gokak Taluk, Karnataka, India. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 58(5), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2019.1685900

- Huang, Y., Li, Q., Zhou, F., & Song, J. (2022). Effectiveness of internet-based support interventions on patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Open, 12(5), e057664. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057664

- Huis, M. A., Hansen, N., Otten, S., & Lensink, R. (2017). A three-dimensional model of women’s empowerment: Implications in the field of microfinance and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1678. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01678

- Ilozumba, O., Van Belle, S., Dieleman, M., Liem, L., Choudhury, M., & Broerse, J. E. W. (2018). The effect of a community health worker utilized mobile health application on maternal health knowledge and behavior: A quasi-experimental study. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00133

- James, K. S., Singh, S. K., Lhungdim, H., Shekhar, C., Dwivedi, L. K., Pedgaonkar, S., & Arnold, F. (2021). National Family Health Survey-5: NFHS-5 India Report, 2019–21. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Government of India. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-5Reports/NFHS-5_India_Report.pdf

- Johri, M., Chandra, D., Kone, K. G., Sylvestre, M. P., Mathur, A. K., Harper, S., & Nandi, A. (2020). Social and behavior change communication interventions delivered face-to-face and by a mobile phone to strengthen vaccination uptake and improve child health in rural India: Randomized pilot study. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 8(9), e20356. https://doi.org/10.2196/20356

- Kabongo, E. M., Mukumbang, F. C., Delobelle, P., & Nicol, E. (2021). Explaining the impact of mHealth on maternal and child health care in low- and middle-income countries: A realist synthesis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03684-x

- Kalokhe, A. S., Iyer, S., Gadhe, K., Katendra, T., Kolhe, A., Rahane, G., Stephenson, R., & Sahay, S. (2021). A couples-based intervention (Ghya Bharari Ekatra) for the primary prevention of intimate partner violence in India: Pilot feasibility and acceptability study. JMIR Formative Research, 5(2), e26130. https://doi.org/10.2196/26130

- Kannure, M., Hegde, A., Khungar-Pathni, A., Sharma, B., Scuteri, A., Neupane, D., Gandhi, R. K., Patel, H., Surendran, S., Jondhale, V., Gupta, S., Phalake, A., Walkar, V., George, R., Mcguire, H., Jain, N., & Vijayan, S. (2021). Phone calls for improving blood pressure control among hypertensive patients attending private medical practitioners in India: Findings from Mumbai hypertension project. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 23(4), 730–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14221

- Kapoor, M., Agrawal, D., Ravi, S., Roy, A., Subramanian, S. V., & Guleria, R. (2019). Missing female patients: An observational analysis of sex ratio among outpatients in a referral tertiary care public hospital in India. BMJ Open, 9(8), e026850. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026850

- Karri, P. S., Jagadisan, B., Lakshminarayanan, S., & Plakkal, N. (2022). Biliary atresia screening in India—Strategies and challenges in implementation. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 89(2), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12098-021-03862-x

- Khokhar, A. (2009). Short text messages (SMS) as a reminder system for making working women from Delhi Breast Aware. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 10(2), 319–322.

- Krithika. (2021). Internet usage in India to grow exponentially by 2025. Economic Diplomacy Division, Ministry of External Affairs, India. https://indbiz.gov.in/internet-usage-in-india-to-grow-exponentially-by-2025/

- Kulathinal, S., Joseph, B., & Säävälä, M. (2019). Mobile helpline and reversible contraception: Lessons from a controlled before-and-after study in rural India. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 7(8), e12672. https://doi.org/10.2196/12672

- Kumar, V., Mohanty, P., & Sharma, M. (2021). Promotion of early childhood development using mHealth: Learnings from an implementation experience in Haryana. Indian Pediatrics, 58(Suppl. 1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-021-2354-8

- Lam, F., Pro, G., Agrawal, S., Shastri, V. D., Wentworth, L., Stanley, M., Beri, N., Tupe, A., Mishra, A., Subramaniam, H., Schroder, K., Prescott, M. R., & Trikha, N. (2019). Effect of enhanced detailing and mass media on community use of oral rehydration salts and zinc during a scale-up program in Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010501. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010501

- LeFevre, A., Agarwal, S., Chamberlain, S., Scott, K., Godfrey, A., Chandra, R., Singh, A., Shah, N., Dhar, D., Labrique, A., Bhatnagar, A., & Mohan, D. (2019). Are stage-based health information messages effective and good value for money in improving maternal newborn and child health outcomes in India? Protocol for an individually randomized controlled trial. Trials, 20(1), 272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3369-5

- Lo, T. Q. K. (2011). Telemedicine provision centers and reproductive age women in rural Uttar Pradesh, India [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkley]. UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/33w37940

- Mackey, A., & Petrucka, P. (2021). Technology as the key to women’s empowerment: A scoping review. BMC Women’s Health, 21(1), 1–12.

- Mahase, E. (2019). Women in India face “extensive gender discrimination” in healthcare access. BMJ, 366, l5057. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l5057

- Manyazewal, T., Woldeamanuel, Y., Blumberg, H. M., Fekadu, A., & Marconi, V. C. (2021). The potential use of digital health technologies in the African context: A systematic review of evidence from Ethiopia. NPJ Digital Medicine, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00487-4

- Mariani, G., Kasznia-Brown, J., Paez, D., Mikhail, M. N., Salama, D. H., Bhatla, N., Erba, P. A., & Kashyap, R. (2017). Improving women’s health in low-income and middle-income countries. Part I: Challenges and priorities. Nuclear Medicine Communications, 38(12), 1019–1023. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNM.0000000000000751

- Maulik, P. K., Kallakuri, S., Devarapalli, S., Vadlamani, V. K., Jha, V., & Patel, A. (2017). Increasing use of mental health services in remote areas using mobile technology: A pre-post evaluation of the SMART Mental Health project in rural India. Journal of Global Health, 7(1), 010408. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.010408

- Modi, D., Dholakia, N., Gopalan, R., Venkatraman, S., Dave, K., Shah, S., Desai, G., Qazi, S. A., Sinha, A., Pandey, R. M., Anand, A., Desai, S., & Shah, P. (2019). mHealth intervention “ImTeCHO” to improve delivery of maternal, neonatal, and child care services—A cluster-randomized trial in tribal areas of Gujarat, India. PLoS Medicine, 16(10), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002939

- Mohan, D., Scott, K., Shah, N., Bashingwa, J. J. H., Chakraborty, A., Ummer, O., Godfrey, A., Dutt, P., Chamberlain, S., & LeFevre, A. E. (2021). Can health information through mobile phones close the divide in health behaviours among the marginalised? An equity analysis of Kilkari in Madhya Pradesh, India. BMJ Global Health, 6(Suppl. 5), e005512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005512

- Moradian, S., Voelker, N., Brown, C., Liu, G., & Howell, D. (2018). Effectiveness of internet-based interventions in managing chemotherapy-related symptoms in patients with cancer: A systematic literature review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(2), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3900-8

- Moulaei, K., Moulaei, R., & Bahaadinbeigy, K. (2023). Barriers and facilitators of using health information technologies by women: A scoping review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 23(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02280-7

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Murthy, N., Chandrasekharan, S., Prakash, M. P., Ganju, A., Peter, J., Kaonga, N., & Mechael, P. (2020). Effects of an mHealth voice message service (mMitra) on maternal health knowledge and practices of low-income women in India: Findings from a pseudo-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1658–1669. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08965-2

- Murthy, N., Chandrasekharan, S., Prakash, M. P., Kaonga, N. N., Peter, J., Ganju, A., & Mechael, P. N. (2019). The impact of an mHealth voice message service (mMitra) on infant care knowledge, and practices among low-income women in India: Findings from a pseudo-randomized controlled trial. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(12), 1658–1669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02805-5

- Nasrabadi, A. N., Sabzevari, S., & Bonabi, T. N. (2015). Women empowerment through health information seeking: A qualitative study. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 3(2), 105–115.

- Nikore, M. (2021). India’s gendered digital divide: How the absence of digital access is leaving women behind. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-gendered-digital-divide/

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pakrashi, D., Maiti, S. N., Gautam, A., Nanda, P., Borkotoky, K., & Datta, N. (2022). Family planning campaigns on television and contraceptive use in India. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 37(3), 1492–1511. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3411

- Pant Pai, N., Daher, J., Prashanth, H. R., Shetty, A., Sahni, R. D., Kannangai, R., Abraham, P., & Isaac, R. (2019). Will an innovative connected AideSmart! app-based multiplex, point-of-care screening strategy for HIV and related coinfections affect timely quality antenatal screening of rural Indian women? Results from a cross-sectional study in India. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 95(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2017-053491

- Patel, A., Kuhite, P., Puranik, A., Khan, S. S., Borkar, J., & Dhande, L. (2018). Effectiveness of weekly cell phone counselling calls and daily text messages to improve breastfeeding indicators. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 337. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1308-3

- Prinja, S., Nimesh, R., Gupta, A., Bahuguna, P., Gupta, M., & Thakur, J. S. (2017). Impact of m-health application used by community health volunteers on improving utilisation of maternal, new-born and child health care services in a rural area of Uttar Pradesh, India. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 22(7), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12895

- Ragesh, G., Ganjekar, S., Thippeswamy, H., Desai, G., Hamza, A., & Chandra, P. S. (2020). Feasibility, acceptability and usage patterns of a 24-hour mobile phone helpline service for women discharged from a Mother-Baby Psychiatry Unit (MBU) in India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(6), 530–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620954148

- Ramagiri, R., Kannuri, N. K., Lewis, M. G., Murthy, G. V. S., & Gilbert, C. (2020). Evaluation of whether health education using video technology increases the uptake of screening for diabetic retinopathy among individuals with diabetes in a slum population in Hyderabad. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 68(Suppl. 1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2028_19

- Ramkumar, V., Hall, J. W., Nagarajan, R., Shankarnarayan, V. C., & Kumaravelu, S. (2013). Tele-ABR using a satellite connection in a mobile van for newborn hearing testing. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 19(5), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X13494691

- Reddy, P. M. C., Rineetha, T., Sreeharshika, D., & Jothula, K. (2020). Health care seeking behaviour among rural women in Telangana: A cross sectional study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(9), 4778–4783. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_489_20

- Roberton, T., Carter, E. D., Chou, V. B., Stegmuller, A. R., Jackson, B. D., Tam, Y., Sawadogo-Lewis, T., & Walker, N. (2020). Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(7), e901–e908. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1

- Santra, S., Garg, S., Basu, S., Sharma, N., Singh, M. M., & Khanna, A. (2021). The effect of a mHealth intervention on anti-tuberculosis medication adherence in Delhi, India: A quasi-experimental study. Indian Journal of Public Health, 65(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_879_20

- Scott, K., Ummer, O., Shinde, A., Sharma, M., Yadav, S., Jairath, A., Purty, N., Shah, N., Mohan, D., Chamberlain, S., & LeFevre, A. E., Kilkari Impact Evaluation team. (2021). Another voice in the crowd: The challenge of changing family planning and child feeding practices through mHealth messaging in rural central India. BMJ Global Health, 6(Suppl. 5), e005868. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005868

- Seshu, U., Khan, H. A., Bhardwaj, M., Sangeetha, C., Aarthi, G., John, S., Thara, R., & Raghavan, V. (2021). A qualitative study on the use of mobile-based intervention for perinatal depression among perinatal mothers in rural Bihar, India. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(5), 467–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020966003

- Seth, R., Akinboyo, I., Chhabra, A., Qaiyum, Y., Shet, A., Gupte, N., Jain, A. K., & Jain, S. K. (2018). Mobile phone incentives for childhood immunizations in rural India. Pediatrics, 141(4), e20173455. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3455

- Shah, P., Madhiwala, N., Shah, S., Desai, G., Dave, K., Dholakia, N., Patel, S., Desai, S., & Modi, D. (2019). High uptake of an innovative mobile phone application among community health workers in rural India: An implementation study. The National Medical Journal of India, 32(5), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-258X.295956

- Shinde, K., Rani, U., & Kumar, P. N. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of immunization reminder system among nursing mothers of South India. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 11(5), 1761. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360X.2018.00327.X

- Shukla, G., Tejus, A., Vishnuprasad, R., Pradhan, S., & Prakash, M. S. (2020). A prospective study to assess the medication adherence pattern among hypertensives and to evaluate the use of cellular phone text messaging as a tool to improve adherence to medications in a tertiary health-care center. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 52(4), 290–295.

- Speizer, I. S., Corroon, M., Calhoun, L., Lance, P., Montana, L., Nanda, P., & Guilkey, D. (2014). Demand generation activities and modern contraceptive use in urban areas of four countries: A longitudinal evaluation. Global Health: Science and Practice, 2(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00109

- Subbaraman, R., de Mondesert, L., Musiimenta, A., Pai, M., Mayer, K. H., Thomas, B. E., & Haberer, J. (2018). Digital adherence technologies for the management of tuberculosis therapy: Mapping the landscape and research priorities. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e001018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001018

- Suryavanshi, N., Kadam, A., Kanade, S., Gupte, N., Gupta, A., Bollinger, R., Mave, V., & Shankar, A. (2020). Acceptability and feasibility of a behavioral and mobile health intervention (COMBIND) shown to increase uptake of prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) care in India. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 752. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08706-5

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA–ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tyers, A., Highet, C., Chamberlain, S., & Khanna, A. (2021). Increasing women's digital literacy in India: What works. BBC Media Action. https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/pdf/india-research-study-women%E2%80%99s-digital-literacy-2021.pdf

- United Nations. (2022). Gender equality and women’s empowerment. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

- Ward, V., Abdalla, S., Raheel, H., Weng, Y., Godfrey, A., Dutt, P., Mitra, R., Sastry, P., Chamberlain, S., Shannon, M., Mehta, K., Bentley, J., & Darmstadt Md, G. L., Ananya Study Group (2021). Implementing health communication tools at scale: Mobile audio messaging and paper-based job aids for front-line workers providing community health education to mothers in Bihar, India. BMJ Global Health, 6(Suppl. 5), e005538. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005538

- World Bank Group. (2021). Accelerating gender equality in digital development. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/61714f214ed04bcd6e9623ad0e215897-0400012021/related/Digital-Development-Note-on-Gender-Equality-November2021-final.pdf