ABSTRACT

Child marriage has adverse consequences for young girls. Cross-sectional research has highlighted several potential drivers of early marriage. We analyse drivers of child marriage using longitudinal data from rural Malawi, where rates of child marriage are among the highest in the world despite being illegal. Estimates from survival models show that 26% of girls in our sample marry before age 18. Importantly, girls report high decision-making autonomy vis-à-vis the decision to marry. We use multivariate Cox proportional hazard models to explore the role of 1) poverty and economic factors, 2) opportunity or alternatives to marriage, 3) social norms and attitudes, 4) knowledge of the law and 5) girls’ agency. Only three factors are consistently associated with child marriage. First, related to opportunities outside marriage, girls lagging in school at survey baseline have significantly higher rates of child marriage than their counterparts who were at or near grade level. Second, related to social norms, child marriage rates are significantly lower among respondents whose caregivers perceive that members of their community disapprove of child marriage. Third, knowledge of the law has a positive coefficient, a surprising result. These findings are aligned with the growing qualitative literature describing contexts where adolescent girls are more active agents in child marriages.

Highlights

Despite growing legal barriers, the incidence of child marriage (marriage before age 18) remains high among girls in Malawi.

Few of the hypothesised drivers of child marriage are significant predictors of child marriage in the cohort under study.

Lagging behind in school and caregivers’ perceptions of community acceptance of child marriage are significant predictors of girls’ early marriage.

In Malawi, adolescent girls are active agents of child marriages; we need to understand the perceived benefits of child marriage from the adolescent perspective in order to reduce child marriages.

1. Introduction

Child marriage – marriage before age 18 – has long attracted considerable research and policy attention. Child marriage is much more common for girls than boys: UNICEF estimates that globally 21% of young women (age 20–24) married before their 18th birthdays, compared with 3% of young men (United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2023). A sizeable literature has shown child marriage to be associated with several harmful outcomes for young women, especially higher exposure to intimate partner violence (Kidman, Citation2017), worse maternal and child health (Fan & Koski, Citation2022), and loss of life opportunities, notably in education (Field & Ambrus, Citation2008; Parsons et al., Citation2015; Wodon et al., Citation2017).

A growing literature investigates why child marriages persist despite such concerns and legal barriers. However, the quantitative literature on the drivers of child marriage relies almost exclusively on cross-sectional and retrospective survey designs, which introduces the possibility of recall biases and reverse causality. The present study investigates the drivers of child marriage using rich prospective longitudinal data on a cohort of adolescent girls from rural Malawi, where the prevalence of child marriage ranks among the highest in the world (United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2023).

1.1. The legal landscape

Given the harmful consequences of child marriage, there has been strong international opposition to the practice for several decades. In 1979, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women directed countries to set a minimum marriage age (UN General Assembly, Citation1979). In an effort to curb the incidence of child marriages, many countries have enacted laws raising the minimum marriage age to 18 (Raub & Heymann, Citation2021).

Against this backdrop, there have been growing legal efforts to curb child marriage in Malawi. In 2015, the Malawian Parliament raised the minimum legal age for all types of unions – from civil to religious marriages, also including marriage by reputation or permanent cohabitation – from age 15 to age 18 through the Marriage, Divorce and Family Relations Act. In 2017, the Parliament unanimously adopted a constitutional amendment to align the Constitution with the 2015 law, effectively legally banning child marriage. Estimates from Malawi’s latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) show that, in 2015-16, 42% of females aged 20–24 had married before the age of 18 compared to 33% among females aged 18–19 (National Statistical Office/Malawi & ICF, Citation2017), hinting at a decline of child marriage potentially linked to these legal efforts.

1.2. Drivers of child marriage: A conceptual framework

Studies have yielded mixed results regarding the ability of minimum-marriage-age laws to prevent child marriage (Batyra & Pesando, Citation2021; Collin & Talbot, Citation2023; Maswikwa et al., Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2022). Furthermore, in many instances, the decreases in child marriage attributed to minimum-age-of-marriage laws have been only moderate (Maswikwa et al., Citation2015). This has prompted some scholars to suggest that the persistence of child marriage may be due to people not knowing the law or countries otherwise not enforcing it (Akter et al., Citation2022; Gage, Citation2013).

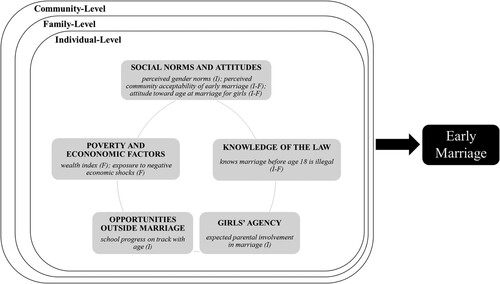

Beyond legal considerations, most studies on the persistence of child marriage pertain to the broader societal drivers of child marriage. In a recent review of the literature on this topic, Psaki and coauthors (Citation2021) developed a nuanced conceptual framework to model the drivers of child marriage. This framework underscores two primary drivers of child marriage, namely economic factors and social norms and attitudes. It also highlights three ancillary drivers, namely girls’ lack of agency, lack of opportunity (or lack of alternatives to marriage), and parents’ fears of girls’ sexuality and pregnancy. These drivers interact with one another at three levels: at the individual-, the family- and the community-level. Owing to these interactions, the effect of these drivers may vary significantly from context to context.

The present study builds on this framework by empirically testing the significance of such drivers using prospective data from rural Malawi. We retain most of the drivers delineated by Psaki and coauthors and incorporate a new one: knowledge of the law (see ). While some studies explore perceptions and knowledge of minimum-age-of-marriage laws in sub-Saharan Africa (Gage, Citation2013; Melnikas et al., Citation2021), no study has investigated whether individuals’ knowledge of the legal age at marriage is linked to their (or their children’s) likelihood of marrying early. We omit one risk factor – parents’ fears of girls’ sexuality and pregnancy – as we do not have data on parents’ expectations of the likelihood and consequences of out-of-wedlock pregnancies for their daughter(s). We do not review the literature on these drivers here as this task has already been accomplished by Psaki and coauthors.

Figure 1. A Conceptual Framework of the Drivers of Early Marriages. Notes: Adapted from Psaki et al. (Citation2021). This simplified figure omits the more complex interactions linking all five drivers of early marriage, which may mediate and moderate each other’s impact on early marriage and do so at multiple levels of analyses, namely individuals, families and communities. The present study includes data on variables (in italics) at the individual-level (I) and family-level (F), but not at the community-level.

Finally, as noted above, drivers of child marriage include factors at the community level. In Malawi, contextualising child marriages further requires highlighting the role of key community actors, in particular village heads. In addition to the literature on heads’ authority in a host of legal, economic, sociopolitical, and traditional ceremonial matters (Basurto et al., Citation2020; Eggen, Citation2011), there is a growing qualitative literature on the village heads’ authority over marriage arrangements. This literature details the village heads’ powers to uphold traditional initiation rituals and marriage practices (Naphambo, Citation2022). It also provides several ethnographic examples of village heads using their power to veto marriage arrangements between young potential spouses, often on the premise that such unions are against the law (Maiden, Citation2021). There is, however, a dearth of studies exploring to what extent village heads are aware of the law on minimum legal age at marriage, personally approve of child marriage practices, and perceive them to be accepted by members of their community.

1.3. Contribution

The present study contributes to the literature on child marriage in several ways. First, using survival analysis, we describe the risk of child marriage in a cohort of 915 adolescent girls from rural Malawi between 2017–18 and 2021 – after a legal ban on child marriage was introduced and consolidated. Second, we contextualise child marriage in Malawi, describing knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions related to child marriage for adolescents, caregivers, and village heads. Third, building from a clear conceptual framework, we provide one of the first studies of the drivers of child marriage using prospective longitudinal data on adolescent girls (Murphy-Graham et al., Citation2020; Singh & Espinoza Revollo, Citation2016). This longitudinal perspective is particularly critical to both reduce recall error and to lessen reverse causality. For example, it is essential that we capture the temporal order between educational outcomes and child marriage, given their bidirectional relationship (Cameron et al., Citation2022). Overall, the present study highlights important elements of contexts, as well as potential pathways, for interventions aimed at reducing child marriage.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

We use data from the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) (Kohler et al., Citation2015), combining data from the MLSFH-Adverse Childhood Experiences (MLSFH-ACE) project and a survey of village heads. The MLSFH began in 1998 and includes a sample covering three districts in the three major regions in rural Malawi: Mchinji (central), Balaka (south) and Rumphi (north). Prior analyses have shown that the MLSFH sample closely matches nationally representative samples of the rural population of Malawi (ibid.).

The MLSFH-ACE is a prospective cohort study of adolescents who are age-eligible household members (mostly biological children) of original MLSFH respondents. The baseline survey wave of the MLSFH-ACE was carried out in 2017–18 and follow-up was carried out in 2021. Adolescents and their caregivers were interviewed at baseline; only adolescents were interviewed at follow-up. Interviews were conducted in respondents’ homes and in their native languages (chiChewa, chiTumbuka or chiYao) by trained interviewers. IRB approval for the MLSFH-ACE was obtained from Stony Brook University (case 1008094) and Malawi’s National Health Science Research Committee (case 1805).

Adolescents in the MLSFH-ACE cohort were aged 10 to 16 at baseline. Of the 2,061 adolescents surveyed at baseline, 1,878 were interviewed again at follow-up. Survey attrition was therefore less than 10%, being slightly more concentrated among girls and respondents living in southern Malawi. We observe no difference in attrition by respondents’ educational attainment or socioeconomic status at baseline. We restrict our sample for this study to girls only, as only five boys in our sample were married before age 18. Of the 915 girls interviewed at both survey waves, we exclude 17 respondents who were already married at baseline. Of the 898 remaining respondents, 10% declared that they had not yet had their first menstruations by survey follow-up. Our analytic sample therefore includes 806 girls who were not already married at survey baseline and who had menarche by survey follow-up, and the 708 caregivers of these girls (some sisters were each interviewed as participants).

In a separate set of descriptive analyses, we describe knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of child marriage among a sample of 97 village heads. These village heads were selected from MLSFH villages in all three MLSFH regions (30 to 35 village heads were selected per region, from villages with the most MLSFH respondents) and surveyed in 2019. Interviews with heads covered a wide range of topics – from local and governmental initiatives to patterns of land ownership and dispute resolution – including two sections about child marriage. Because villages in Malawi often have fluid and disputed boundaries (Mitchell, Citation1956; Verdon, Citation1995), however, we cannot rigorously merge village-heads-level data with data on adolescents from the MLSFH-ACE. Our analyses of village heads therefore remain separate from our analyses of adolescents and their caregivers.

2.2. Outcome: Child marriage

The event under study is defined as marriage before age 18. Scholars have long noted how local definitions of marriage in sub-Saharan Africa may vastly differ among regions and ethnic groups (Meekers, Citation1992). In Malawi, marriages may occur in the absence of formal ceremonies or official community recognition. Postmarital residence may be patrilocal, matrilocal or neolocal depending on region or tribe. There are also cases of spouses who do not immediately live together after marriage, or of polygynous men dividing their time among the houses of their wives (Reniers, Citation2003; Reniers & Tfaily, Citation2008). Given this variability, we rely on respondents’ own categorizations when defining marriage, as our survey question asked respondents: ‘Are you currently married or living with a partner as if married?’. This definition corresponds to the legal framework for defining minimum marriage age in Malawi (in which marriage by reputation or permanent cohabitation are construed as marriage), and is aligned with UNICEF’s definition of child marriage as encompassing cohabitation (Efevbera & Bhabha, Citation2020; United Nations Children’s Fund, Citation2023).

For our main analyses, we use survival analysis to model the risk of child marriage as a function of age, with respondent's age at menarche denoting the onset of the risk period. Menarche appears to mark the onset of marriageability throughout rural Malawi, despite the fact that initiation ceremonies are more prevalent in the south than in the north (Mair, Citation1951; Munthali & Zulu, Citation2007; Perianes & Ndaferankhande, Citation2020). Observations are right-censored at age 18 or at respondent's age at follow-up (whichever is lower) when the respondent is not married by survey follow-up. Respondents who married at age 18 and above are also right-censored at age 18.

2.3. Predictors

In our multivariate analyses, we use predictors related to all five drivers of child marriage at two levels of analysis: individuals and families. These predictors were provided by the girls themselves at the individual-level and by their primary caregivers at the family-level. All data on predictors were collected at baseline. maps these predictors on the general conceptual framework inspired by Psaki and co-authors.

We capture social norms and attitudes using a combination of individual- and family-level predictors. To capture the role of norms indirectly related to child marriage, we build an index denoting girls’ perceptions of gender norms in their communities. This index adds data from nine questions on girls’ perceptions of women’s decision-making power, freedom of movement and intimate-partner violence in their communities (see supplemental materials), with all questions receiving equal weight in the index. Higher values of this index signify that gender norms are perceived to be more equitable. This predictor on gender norms was collected only among girls, whereas predictors on attitudes toward child marriage and perceptions of acceptability of child marriage were collected among both adolescents and their caregivers, using identical questions. For some of these questions, we recoded respondents’ continuous responses as binary variables. The attitude component is a binary variable coded 0 if respondents declared that the ideal age for a young girl to get married is below 18, and 1 if respondents declared that this ideal age is 18 and above. The perception component is a binary variable coded 0 if respondents declared that members of their communities generally approved of marriage before age 18, and 1 if they perceived that members of their communities generally disapproved of marriage before age 18.

We use two predictors related to poverty and economic factors collected only at the family level. The first is the family’s wealth using a standardised wealth index summing household ownership of 20 durable assets, where each asset is weighted by the inverse of the proportion of households in the sample also owning this asset. The second is the count of negative economic shocks in the 12 months preceding the interview. Negative economic shocks are poor crop yields, loss of livestock, loss of income sources in the households, and damage to house due to unexpected events.

Knowledge of the law is measured at the individual- and family-level. We use a binary variable coded 0 if respondents declared that the minimum legal age at marriage is below 18, and 1 if respondents declared that this minimum legal age is 18 and above.

We capture opportunities or alternatives to marriage at the individual-level using respondents’ delays in schooling, which is a continuous variable subtracting respondents’ schooling in years from the ‘expected’ schooling progression given respondents’ ages if they had entered school at the legal age of six years old and progressed one grade each year.

Lastly, we capture agency at the individual-level using a binary variable denoting whether girls expected that they will be able to choose when to get married.

2.4. Analyses

First, we use descriptive and multivariate analyses to estimate rates of child marriage and the determinants of these rates. For descriptive analyses we estimate a Kaplan-Meier survival function of child marriage by age, with delayed entries accounting for differences in age at menarche. Several respondents (N = 38) declared that they married and had menarche at the same age. Some respondents (N = 4) also declared that their age at menarche was their current age (at follow-up). For these respondents, we assume that average duration of exposure is 0.5 person-years, a simplifying assumption that posits that the risk of marriage and menarche are linearly distributed during each age year.

For multivariate analyses of child marriage rates, we use Cox proportional hazard models. These models do not require us to specify the underlying risk function of child marriage but assume that the risk of child marriage is proportional between different values of a predictor. Analysis of Schoenfeld residuals show no evidence that this assumption is violated for the predictors under study. To account for tied failures and censoring (as ages at menarche and marriage were reported in whole years), we compute likelihoods using the Efron approximation (Efron, Citation1977). All multivariate analyses control for respondents’ ages, regions (districts of residence) and ages at menarche. Of the 806 female respondents eligible for multivariate analyses, 11% had missing values on at least one predictor of interest. We handled these missing data using multiple imputations. All predictors included in our multivariate models were included in the imputation model, which relied on chained regressions (as we used continuous, categorical and binary predictors) imputing 20 datasets over 200 iterations.

As detailed in Psaki and coauthors’ framework, the drivers of child marriages may be directly associated with child marriages. However, they may also mediate, confound or moderate the associations between other predictors and child marriages. For the present paper, we leave aside the question of statistical moderation and focus on detecting potential mediation and confounding between the drivers of child marriages. We therefore produce three sets of models: 1) bivariate relationships between child marriages and the drivers of child marriages; 2) multivariate relationships between child marriages and drivers of child marriages adjusting for respondents’ ages, regions of residence at baseline and ages at menarche; 3) multivariate relationships where all drivers are included in a single model.

Finally, in addition to our analyses of rates of child marriages, we provide separate descriptive analyses detailing village heads’ knowledge of the law and attitudes and perceptions about child marriages.

3. Results

3.1. Description of sample

describes the sample at survey baseline and follow-up, in addition to village-level characteristics and reports by village heads at mid-point between baseline and follow-up. We describe both the full sample of 915 adolescent girls who were interviewed at both waves of the MLSFH-ACE, as well as our analytic sample of 806 adolescent girls who had had their first menstruations by survey follow-up and who were not already married at survey baseline. Median age at menarche was 14 years and ranged between 10 and 18 years.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of full and analytic samples.

More than 60 percent of respondents in our sample were two or more years behind their expected schooling given their age. This number grew between baseline and follow-up, as the proportion of girls in our sample who had dropped out of school grew from 7% to 45%. Households saw virtually no increase or decrease in their wealth indices between survey rounds but experienced slight reductions in the number of negative economic shocks they faced in the previous 12 months.

As Melnikas et al. (Citation2021) noted in their qualitative study, we find that respondents and caregivers tend to overestimate the minimum legal age at marriage, with several of them reporting ages well beyond 18. Roughly 90% of respondents and caregivers know that the minimum legal age at marriage is age 18 or higher. Attitudes toward age at marriage present more variation. More than 55% of adolescent respondents declared that the youngest age at which a girl should marry is 18 years and older. This number increases to 70% among caregivers. However, more than 97% of girls in our sample declared – at survey baseline – that they aspired to marry at age 18 and above (Zahra et al., Citation2021). Lastly, roughly 65% of adolescent girls and caregivers perceive that members of their community disapprove of marriage before age 18.

3.2. Prevalence and incidence of child marriages

Nearly 25% of girls in our sample were married by survey follow-up. However, more than 60% of girls in our sample were less than 18 years old at survey follow-up; these respondents are still at risk of child marriages. Nevertheless, nearly half of respondents aged 18 and above were married by survey follow-up, and half of them reported ages at marriage below 18. This figure is lower than that estimated in Malawi’s latest DHS (fielded in 2015–16), which reports that 42% of women aged 20–24 were married before age 18 compared to 33% among women aged 18–19 (National Statistical Office/Malawi & ICF, Citation2017).

Regarding incidence, the 806 respondents in our analytic sample spent an average of 2.4 years at risk of child marriage (measured since menarche). 125 child marriages were recorded during this period, yielding a total incidence rate of 0.06 per person-year. provides a Kaplan-Meier survival estimate which models the cumulative incidence of child marriage as a function of age. This estimate accounts for delayed entries (due to differences in age at menarche) and right censoring and shows that more than 26% of girls in our sample marry before age 18.

Table 2. Kaplan-Meier survival function of early marriages.

3.3. The decision to marry: Girls and their caregivers

Girls in the MLSFH-ACE cohort reported a high degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the decision to marry. At survey baseline, more than 90% of girls reported that they expected to choose when they would marry. The 10% of girls who did not expect to choose when to marry at survey baseline do not have significantly different marriage rates (p = 0.95) than those of the remaining 90% of girls, even after controlling for age. Among girls who were married by survey follow-up, nearly 95% declared that the decision to marry was primarily theirs (only 3% declared that their families were the primary decision-makers). Crucially, this figure does not significantly differ between girls who married before or after age 18 (p = 0.55). Furthermore, 90% of married girls declared that they chose their spouses themselves (as opposed to ‘chosen for me’), and girls who married before age 18 were in fact more likely to have selected their spouses than girls who married at age 18 and above (93% versus 81%; p = 0.01).

Additional survey questions on attitudes reveal a high endorsement of girls’ autonomy to select their spouses themselves. At survey baseline, 85% of respondents and 93% of caregivers agreed with the statement that ‘A daughter has the right to freely choose who she wants to marry’. There is a lower endorsement of girls’ autonomy to choose when to marry. Only 65% of respondents agreed with the statement that ‘A daughter has the right to freely choose when (at what age) to marry’, compared to 64% among caregivers. Considering girls’ high autonomy over the decision to marry, these reports may imply that several respondents and caregivers perceive that daughters will, if unimpeded, marry too early. Other qualitative studies noted similar perceptions in Tanzania (Schaffnit & Lawson, Citation2021; Schaffnit, Hassan, et al., Citation2019) and Malawi (Melnikas et al., Citation2021).

3.4. Multivariate analyses of socioeconomic and normative predictors of child marriages

shows results of Cox-proportional-hazard-regression analyses of child marriage on five categories of drivers of child marriage. Estimates of hazard ratios are mostly stable among all three sets of models (bivariate, adjusted and full), although estimates of p-values decrease when additional controls and predictors are included in the analysis. This shows that only a modest level of mediation and confounding is occurring between predictors.

Table 3. Cox proportional hazards regression analyses of early marriages on socioeconomic and normative predictors; hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals presented.

Overall, most drivers of child marriages explored in the conceptual framework are not significantly associated with rates of child marriages. This finding is itself of interest. Instead, results show that only three hypothesised variables are significant predictors of child marriages. First, girls lagging behind in school at survey baseline had significantly higher rates of child marriages than their counterparts with no delays in schooling. More precisely, each additional grade behind in school is associated with a 15 percent higher risk of child marriages. Second, girls whose caregivers perceive that their community disapproves of marriages before age 18 have roughly 40 percent lower rates of child marriages than girls whose parents perceive that their community approves of child marriages. Third, and contrary to our hypothesis, when girls correctly identified that marriages before age 18 were illegal had marriage rates that were more than twice as high at follow-up. These associations hold after adjusting for region and age at menarche and when including all other drivers of child marriages in the same model.

3.5. Knowledge, attitude and perception of child marriages among village heads

describes knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of child marriages among a sample of 97 heads from villages surveyed by the MLSFH. The median age among village heads is 56. Nearly 20% of village heads are women. We find no evidence that the knowledge, attitudes and perception of child marriage differ by village heads’ gender (data not shown).

Table 4. Village heads’ demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of early marriages.

Virtually all village heads in our sample knew that marriage before age 18 is illegal. However, 30% of them overestimated the minimum legal age at marriage, a figure that is similar to that provided by adolescent respondents and their caregivers. Three quarters of village heads declared that the youngest age at which girls should marry is 18 and above. Likewise three quarters perceived that members of their community disapprove of child marriages. Interestingly, among village heads who personally approved of marriages before age 18, 60% perceived that their communities disapprove of such marriages, compared to 80% among village heads who personally disapproved of child marriages. Finally, 93% of village heads reported that ‘girls should be free to choose who to marry’, as opposed to only 30% reporting that ‘girls should be free to choose when to marry’.

Contrary to the reports of adolescent respondents, who by-and-large declared that they chose to marry on their own, 15% of village heads declared that parents were the primary decision-makers in marriage matters in their village. This figure varied substantially by region, however, as 30% of village heads from the Balaka district (south) reported that parents were the primary decision-makers in marriage arrangements, compared to 11% among village heads from the Mchinji (central) district and 9% among village heads in the Rumphi (north) district. 57% of village heads reported that girls’ participation in decisions about when and whom to marry had increased during the past five years. 82% also declared that at least one governmental or non-governmental initiative to reduce child marriage occurred in their village.

4. Discussion

A growing literature explores why child marriages persist in many regions of the world despite mounting legal barriers against these marriages. Existing quantitative analyses of the drivers of child marriage have all been conducted using cross-sectional or retrospective survey designs. Against this backdrop, we carry out prospective longitudinal analyses of the timing and determinants of child marriage in rural Malawi, a country where rates of child marriages are among the highest in the world. Our longitudinal analyses has the advantages of not being subject to recall error and less risk of reverse causality. We present three main contributions from this study.

First, we find that approximately 1 in 4 girls marry before they turn 18. This high incidence occurs despite widespread knowledge among respondents, their caregivers and village heads that marrying before age 18 is now illegal in Malawi. Moreover, this is occurring in communities where the majority of village heads reported public initiatives aimed at preventing child marriages. The prevalence of child marriages measured in the MLSFH-ACE cohort is lower than that estimated in the latest DHS in Malawi, which was fielded after the minimum marriage age law was voted on in parliament but one year before this law was inscribed in Malawi's constitution. Our results, however, do not allow us to assess whether there was a national decline in rates of child marriage due to these legal changes.

Second, we show that married girls report a high degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the decision to marry. Nearly 95 percent of married girls in our sample reported that they were the primary decision-makers on when to marry. Across the board – in interviews with adolescent girls, their caregivers, and village heads – most respondents endorsed girls’ agency to choose whom and when they marry. Most of these respondents also believed that the youngest age at which girls should marry is 18 or above. However, adolescent girls favoured younger ages at marriage than their caregivers and village heads. At any rate, results from multivariate analyses show that these attitudes were not significant predictors of rates of child marriages.

Third, we tested five categories of hypothesised drivers. We find that the risk of child marriages is higher for girls lagging behind in school at baseline compared to their counterparts with no delays in schooling. Related to social norms and attitudes, we also find that the risk of child marriages is significantly lower among girls with caregivers who perceive that their community disapproves of child marriages. We also find that knowledge of the law, surpringly, is positively associated with child marriage. Other hypothesised drivers, such as poverty and agency were not significantly associated with child marriages.

Prior qualitative research provides more insight into why the first two of these factors may be important drivers. In their study of adolescent marriages in Tanzania, where child marriages are also highly prevalent and where arranged marriages are not common, Schaffnit and coauthors found that ‘education was the most desirable opportunity for most adolescent girls, seen as a way of improving lives of girls and parents’ (Schaffnit et al., Citation2021, p. 1824). This observation was also underscored in qualitative studies in Malawi (Frye, Citation2012, Citation2017). On the other hand, scholars also emphasise that girls and their parents must weigh any potential benefits of education against the cost of ancillary schooling fees and the perceived risks associated with schooling: these include negative peer influence, maltreatment from teachers, and the general risk of pre-marital pregnancy while in school (Schaffnit, Urassa, et al., Citation2019). We therefore hypothesise that girls already lagging behind in school expect fewer benefits from staying in school compared to their counterparts who are succeeding, and therefore are more likely to marry early (Petroni et al., Citation2017).

Regarding the role of caregivers’ perceptions, a qualitative study in northern Malawi by Melnikas and coauthors (Citation2021) highlights that most parents they interviewed feared punishment (through fines or even arrest) by village heads or community members should they allow their daughter(s) to break the law and marry early. Maiden (Citation2021) observed that the types of sanctions for violating marriage age laws, as well as village heads’ propensities to end child marriages and punish offenders, varied among communities. In this context, we hypothesise that parents who perceive that their community disapproves of child marriage may also perceive that they are more likely to be punished for their daughters’ child marriages. They would then be more likely to prevent their daughters’ child marriages than parents who perceive that their community approves of child marriages. However, Melnikas and co-authors underscore that ‘[a]s we heard from parents in focus groups, generally they feel that they are not able to prevent child marriages from occurring’ (Citation2021, p. 10).

Knowledge of the law was associated with greater child marriage. This relationship played out in an unexpected direction: girls who knew that child marriage was illegal married early at twice the rate of those who did not. This finding was surprising, and we can only roughly speculate as to its explanation and encourage further qualitative work. For instance, it is possible that social engagement plays a role in confounding this association. Only about 12% of girls did not know that marriage before 18 was illegal. These may represent girls who were more socially isolated, were not dating, and thus did not hear about the laws from peers. This may have protected them: a study in Tanzania found that girls who had to ask permission to leave the home were less likely to marry early (Misunas et al., Citation2021). Greater social engagement, on the other hand, would be linked to more romantic relationships. As girls date and begin thinking about marriage, conversations about the legal context may more naturally arise, thus providing a link between knowledge and early marriage. Finally, there is evidence that parental fears concerning premarital sex, early sexual debut, and unplanned pregnancy are all associated with child marriage (Misunas et al., Citation2021; Mpilambo et al., Citation2017). This may likewise tie into our finding that girls who married before age 18 were in fact more likely to have selected their spouse. Girls independently make the decision about who to date; after an unplanned pregnancy, families may have supported a marriage to this same partner.

Finally, we note that the drivers of child marriage are likely to be context specific. Our study took place in Malawi, where adolescent girls hold comparatively high agency vis-à-vis the decision to marry, yet many still decide to marry early (Guirkinger et al., Citation2021). This is in opposition to contexts where child marriages co-occur with arranged marriages, such as the so-called ‘patriarchal belt’ running from north Africa to southeast Asia (Littrell & Bertsch, Citation2013). Therefore, there is need for prospective studies of child marriage carried out in a diverse range of sociocultural settings to guide locally adapted intervention.

4.1. Limitations

We note a few limitations. First, this is still a relatively young cohort, and many girls have not yet reached the age of 18. While we attempt to deal with this through censoring, testing the conceptual framework in an older sample would be preferred. Second, there is the possibility of omitted variable bias, as unmeasured factors may explain both the drivers and child marriage outcomes. Third, we did not collect information on why girls chose to marry or the characteristics of their spouses; qualitative research would greatly strengthen our interpretation of the quantitative findings.

4.2. Implications

Overall, the present study highlights important elements of contexts, as well as potential pathways, for interventions aimed at reducing child marriage. Results show that child marriage may persist despite widespread knowledge of minimum legal age at marriage and comparatively high female agency. Findings instead emphasise the importance of improving educational opportunities for girls and addressing parents’ perceptions of norms toward child marriage in their communities. Interventions, such as cash transfers, aimed at improving school progression among girls could be an effective strategy for preventing child marriages, and in fact are the most common type of intervention for this purpose (Kalamar et al., Citation2016; Malhotra & Elnakib, Citation2021).

These results are aligned with a growing qualitative literature describing contexts where adolescent girls are more active agents of child marriages, and where parents and other community actors may discourage these marriage arrangements. Many child marriage interventions focus on changing attitudes and knowledge, with an assumption that girls are forced into child marriages (Lokot et al., Citation2021). The underlying theory of change for many interventions is that creating agency will empower them to resist child marriages. Yet in Malawi, girls are seemingly aware of their legal rights and are not being pressured to marry by caregivers, yet a quarter still report that they choose to marry before age 18. In fact, research shows that many girls perceive that child marriages improve their status and independence (Schaffnit et al., Citation2021). Thus, we need to challenge the prevailing narrative that empowerment alone will deter child marriages. Instead, researchers thus need to do a better job listening to girls and understanding the structural barriers (e.g. social or economic advantages) that make child marriage an attractive option. Only once we understand the perceived benefits can we start designing interventions that really meet girls where they are.

We also need more research to elucidate why some caregivers and community members intervene to prevent child marriages while others do not – despite all knowing that the practice is illegal. As scholars have noted, this first requires a conceptual shift from focusing on parents’ often coercive efforts to arrange their daughters’ marriages in strongly patriarchal contexts, to focusing on parents’ involvement in helping daughters understand the risks inherent in child marriage in contexts of higher adolescent female agency. In this regard, Petroni and co-authors (Citation2017) have highlighted the importance of interventions aimed at improving intergenerational communication, especially as adolescents enter adulthood. This reflection can also be extended to the role of other community actors, such as village heads and members of extended kin networks, who can also act as catalysts of marriage change in their social network.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the respondents for their time and willingness to share their experiences. We also thank the staff (field supervisors, interviewers, counsellors, and many others) at Invest in Knowledge International for their time, effort, and support of this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

An anonymized public-use version of the MLSFH data is being prepared for release via the Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akter, S., Williams, C., Talukder, A., Islam, M. N., Escallon, J. V., Sultana, T., Kapil, N., & Sarker, M. (2022). Harmful practices prevail despite legal knowledge: A mixed-method study on the paradox of child marriage in Bangladesh. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29(2), 1885790. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2021.1885790

- Basurto, M. P., Dupas, P., & Robinson, J. (2020). Decentralization and efficiency of subsidy targeting: Evidence from chiefs in rural Malawi. Journal of Public Economics, 185, 104047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2019.07.006

- Batyra, E., & Pesando, L. M. (2021). Trends in child marriage and new evidence on the selective impact of changes in age-at-marriage laws on early marriage. SSM-Population Health, 14, 100811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100811

- Cameron, L., Contreras Suarez, D., & Wieczkiewicz, S. (2022). Child marriage: Using the Indonesian family life survey to examine the lives of women and men who married at an early age. Review of Economics of the Household, 21(3), 725–756.

- Collin, M., & Talbot, T. (2023). Are age-of-marriage laws enforced? Evidence from developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 160, 102950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102950

- Efevbera, Y., & Bhabha, J. (2020). Defining and deconstructing girl child marriage and applications to global public health. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1547. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09545-0

- Efron, B. (1977). The efficiency of Cox's likelihood function for censored data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 72(359), 557–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1977.10480613

- Eggen, Ø. (2011). Chiefs and everyday governance: Parallel state organisations in Malawi. Journal of Southern African Studies, 37(02), 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2011.579436

- Fan, S., & Koski, A. (2022). The health consequences of child marriage: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12707-x

- Field, E., & Ambrus, A. (2008). Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 881–930. https://doi.org/10.1086/593333

- Frye, M. (2012). Bright futures in Malawi’s new Dawn: Educational aspirations as assertions of identity. American Journal of Sociology, 117(6), 1565–1624. https://doi.org/10.1086/664542

- Frye, M. (2017). Cultural meanings and the aggregation of actions: The case of sex and schooling in Malawi. American Sociological Review, 82(5), 945–976. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122417720466

- Gage, A. J. (2013). Child marriage prevention in Amhara region, Ethiopia: Association of communication exposure and social influence with parents/guardians’ knowledge and attitudes. Social Science & Medicine, 97, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.017

- Guirkinger, C., Gross, J., & Platteau, J.-P. (2021). Are women emancipating? Evidence from marriage, divorce and remarriage in Rural Northern Burkina Faso. World Development, 146, 105512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105512

- Kalamar, A. M., Lee-Rife, S., & Hindin, M. J. (2016). Interventions to prevent child marriage among young people in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of the published and gray literature. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(3, Supplement), S16–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.015

- Kidman, R. (2017). Child marriage and intimate partner violence: A comparative study of 34 countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(2), 662–675.

- Kohler, H.-P., Watkins, S. C., Behrman, J. R., Anglewicz, P., Kohler, I. V., Thornton, R. L., Mkandawire, J., Honde, H., Hawara, A., & Chilima, B. (2015). Cohort profile: The Malawi longitudinal study of families and health (MLSFH). International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(2), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu049

- Littrell, R. F., & Bertsch, A. (2013). Traditional and contemporary status of women in the patriarchal belt. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(3), 310–324.

- Lokot, M., Sulaiman, M., Bhatia, A., Horanieh, N., & Cislaghi, B. (2021). Conceptualizing “agency” within child marriage: Implications for research and practice. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105086

- Maiden, E. (2021). Recite the last bylaw: Chiefs and child marriage reform in Malawi. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 59(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X20000713

- Mair, L. P. (1951). Marriage and family in the dedza district of nyasaland. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 81(1/2), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/2844018

- Malhotra, A., & Elnakib, S. (2021). Evolution in the evidence base on child marriage.

- Maswikwa, B., Richter, L., Kaufman, J., & Nandi, A. (2015). Minimum marriage age laws and the prevalence of child marriage and adolescent birth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(2), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1363/4105815

- Meekers, D. (1992). The process of marriage in African societies: A multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review, 61–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1971859

- Melnikas, A. J., Mulauzi, N., Mkandawire, J., & Amin, S. (2021). Perceptions of minimum age at marriage laws and their enforcement: Qualitative evidence from Malawi. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11434-z

- Misunas, C., Erulkar, A., Apicella, L., Ngô, T., & Psaki, S. (2021). What influences girls’ age at marriage in Burkina Faso and Tanzania? Exploring the contribution of individual, household, and community level factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6, Supplement), S46–S56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.015

- Mitchell, J. C. (1956). The Yao village. Manchester University Press.

- Mpilambo, J. E., Appunni, S. S., Kanayo, O., & Stiegler, N. (2017). Determinants of early marriage among young women in democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of Social Sciences, 52(1–3), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2017.1322393

- Munthali, A. C., & Zulu, E. M. (2007). The timing and role of initiation rites in preparing young people for adolescence and responsible sexual and reproductive behaviour in Malawi. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11(3), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.2307/25549737

- Murphy-Graham, E., Cohen, A. K., & Pacheco-Montoya, D. (2020). School dropout, child marriage, and early pregnancy among adolescent girls in rural Honduras. Comparative Education Review, 64(4), 703–724. https://doi.org/10.1086/710766

- Naphambo, E. K. (2022). A vexing relationship between chiefship and girls’ sexuality: Insights from rural Malawi. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(3), S36–S42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.005

- National Statistical Office/Malawi, & ICF. (2017). Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR319/FR319.pdf

- Parsons, J., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., Petroni, S., Sexton, M., & Wodon, Q. (2015). Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature. The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2015.1075757

- Perianes, M. B., & Ndaferankhande, D. (2020). Becoming female: The role of menarche rituals in “making women” in Malawi. In C. Bobel, I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, & T. A. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies (pp. 423–440). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Petroni, S., Steinhaus, M., Fenn, N. S., Stoebenau, K., & Gregowski, A. (2017). New findings on child marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. Annals of Global Health, 83(5–6), 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2017.09.001

- Psaki, S. R., Melnikas, A. J., Haque, E., Saul, G., Misunas, C., Patel, S. K., Ngo, T., & Amin, S. (2021). What are the drivers of child marriage? A conceptual framework to guide policies and programs. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(6), S13–S22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.001

- Raub, A., & Heymann, J. (2021). Progress in national policies supporting the sustainable development goals: Policies that matter to income and its impact on health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094151

- Reniers, G. (2003). Divorce and remarriage in rural Malawi. Demographic Research, 1, 175–206. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2003.S1.6

- Reniers, G., & Tfaily, R. (2008). Polygyny and HIV in Malawi. Demographic Research, 19(53), 1811. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.53

- Schaffnit, S. B., Hassan, A., Urassa, M., & Lawson, D. W. (2019). Parent–offspring conflict unlikely to explain ‘child marriage’in northwestern Tanzania. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(4), 346–353. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0535-4

- Schaffnit, S. B., & Lawson, D. W. (2021). Married Too young? The behavioral ecology of ‘child marriage’. Social Sciences, 10(5), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050161

- Schaffnit, S. B., Urassa, M., & Lawson, D. W. (2019). “Child marriage” in context: Exploring local attitudes towards early marriage in rural Tanzania. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 27(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2019.1571304

- Schaffnit, S. B., Wamoyi, J., Urassa, M., Dardoumpa, M., & Lawson, D. W. (2021). When marriage is the best available option: Perceptions of opportunity and risk in female adolescence in Tanzania. Global Public Health, 16(12), 1820–1833. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1837911

- Singh, A., & Espinoza Revollo, P. (2016). Teenage marriage, fertility, and well-being: Panel evidence from India. Young Lives Working Paper, 151.

- UN General Assembly. (1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

- United Nations Children’s Fund. (2023). Child marriage data. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/.

- Verdon, M. (1995). Les Yao du Malawi: une chefferie matrilinéaire?(The Yao of Malawi: A Matrilineal Chiefdom). Cahiers d'etudes africaines, 477–511. https://doi.org/10.3406/cea.1995.1457

- Wilson, N. (2022). Child marriage bans and female schooling and labor market outcomes: Evidence from natural experiments in 17 low-and middle-income countries. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(3), 449–477. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20200008

- Wodon, Q., Male, C., Nayihouba, A., Onagoruwa, A., Savadogo, A., Yedan, A., Edmeades, J., Kes, A., John, N., & Murithi, L. (2017). Economic impacts of child marriage: global synthesis report.

- Zahra, F., Kidman, R., & Kohler, H. P. (2021). Social norms, agency, and marriage aspirations in Malawi. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(5), 1332–1348. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12780