ABSTRACT

Leprosy is an infectious neglected tropical disease, which can cause irreversible disabilities if not diagnosed in time. Colombia continues to show high rates of leprosy-related disability, mainly due to a delay in diagnosis. Limited knowledge is available that explains this delay, therefore our study aimed to explore the perceptions and experiences of leprosy health professionals with the delay in leprosy diagnosis in the Cesar and Valle del Cauca departments, Colombia. Nine semi-structured expert interviews with leprosy health professionals were conducted in May-June 2023 in Colombia. Thematic analysis was performed to analyse the interview results. Our analysis highlighted that the main reasons for delay at the health system-level included accessibility issues to obtain a diagnosis, lack of expertise by health staff, and barriers related to the organisation of the care pathway. Individual – and community-level factors included a lack of leprosy awareness among the general population and leprosy-related stigma. Diagnostic delay consists of a fluid interplay of various factors. Structural changes within the health system, such as organising integral leprosy care centres and highlighting leprosy in the medical curriculum, as well as awareness-related interventions among the general population, might help reducing diagnostic delays.

Introduction

Leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, is an infectious neglected tropical disease caused by Mycobacterium Leprae. If not detected and treated early, leprosy can cause severe irreversible disabilities, formally classified by the World Health Organisation (WHO) (Citation2017) as Grade Two Disability (G2D). Therefore, the delay in diagnosis of leprosy is considered ‘one of the leading causes of preventable disability worldwide’ (Gómez et al., Citation2018, p. 193). In the Global Leprosy Strategy 2021-2030, the WHO (Citation2017) highlighted the delay in diagnosis as a core challenge to reach a 90% global reduction aim of new G2D cases by 2030. However, prior targets set by the WHO (Citation2017) to diminish the G2D rate in newly detected cases to less than one per million population and to reduce the G2D rate in newly detected child cases to zero by 2020 have not been achieved.

Although Colombia has a low leprosy burden with approximately 300 new cases annually (compared to India and Brazil with respectively 75,394 and 18,318 new cases in 2021), the disease continues to be endemic in certain parts of the country, including the departments of Cesar and Valle del Cauca (Cáceres-Durán, Citation2022; WHO, Citation2022). Colombia’s National Health Institute (Instituto Nacional de Salud [INS], Citation2023) reported 19 new leprosy cases in Cesar and 38 in Valle del Cauca (including the district of Cali) in 2022. With new case detection rates of 1.42, 1.00 and 0.79 (per 100,000 population) for respectively Cesar, Valle del Cauca and its district Cali, these rates are far above the national average (0.56) (INS, Citation2023). In addition, Colombia shows high rates of disability at the time of leprosy diagnosis (Cáceres-Durán, Citation2022). Specifically, approximately 63% of the new leprosy cases in the department of Cesar had some degree of disability at the time of diagnosis in 2022 (INS, Citation2023).

Several studies researched the delay in leprosy diagnosis within Colombia. For instance, two studies by Guerrero et al. (Citation2013) and Gómez et al. (Citation2018) found an average delay of nearly three years (respectively 2.9 years and 33.5 months). A recent study by Rodríguez Torres et al. (Citation2023) which considered cases from 2016–2021 in Valle del Cauca, found an average delay of 21.5 months. However, there is still limited knowledge about the underlying reasons that lead to the delay in leprosy diagnosis in Colombia. Gómez et al. (Citation2018) provided initial understanding by highlighting that patients tended to not seek help after noticing the first symptoms due to their inability to recognise the importance of the symptoms. In addition, they found that up to five consultations might be required for a patient to receive a final diagnosis (Gómez et al., Citation2018). A recent study by Rodríguez Torres et al. (Citation2023) found that attending public health services increased the risk of delay in diagnosis compared to using private health services.

Similar challenges have been identified in other countries. Two systematic reviews by Dharmawan et al. (Citation2021, Citation2022) provide an overview of research on diagnostic delay of leprosy around the world. The authors distinguished between healthcare-related factors, individual and community factors (Dharmawan et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). According to Dharmawan et al. (Citation2022), healthcare-related factors included poor geographical access to healthcare services as well as limited availability and low commitment of health staff. In addition, the authors highlighted that lack of awareness about leprosy symptoms, rural residence, and stigma that associates leprosy with isolation and a high risk of contagion are among the individual and community factors that contribute to delay in diagnosis (Dharmawan et al., Citation2021). Nicholls et al. (Citation2003) conducted a qualitative study with patients, health staff and other community members (including pastors and natural healers) at a leprosy referral centre in Paraguay. They showed how traditional beliefs, such as the idea that symptoms are only considered important when causing pain, diminish health-seeking behaviour for early leprosy symptoms in patients (Nicholls et al., Citation2003). In addition, they described how the fear associated with isolation after receiving a diagnosis negatively impacted patients’ decisions to seek help.

There is still very limited in-depth qualitative research exploring the reasoning behind the delay in leprosy diagnosis in Colombia, specifically in the endemic regions. Therefore, this study aims to address this gap in knowledge by exploring the perceptions and experiences of leprosy health professionals with the delay in leprosy diagnosis in two endemic departments Cesar and Valle del Cauca in Colombia. These experiences are crucial to further understand the reasoning behind the delay in diagnosis in the two departments of Colombia and allow us to map potential solutions for early diagnosis that might prevent not only physical complications, but also psychosocial consequences in leprosy patients.

Methods

Study design

Research was based on a case study qualitative design and had an exploratory nature. The method of semi-structured expert interviews was chosen to explore the perceptions about the delay in leprosy diagnosis in Cesar and Valle del Cauca in Colombia. A qualitative approach provided us with an opportunity for in-depth exploration and understanding of the reasons behind the delay in leprosy diagnosis (Green & Thorogood, Citation2018). The semi-structured interviews included both the pre-determined research themes as well as broader open questions to provide research participants with flexibility to explain their experiences and perceptions of delay in leprosy diagnosis.

Study setting

Our study focuses on the departments of Cesar and Valle del Cauca in Colombia. Valle del Cauca and its capital Santiago de Cali are located in Western Colombia. The department is divided into 42 municipalities and encompasses a population of approximately 4.5 million (Roldán González & Velasco Franco, Citation2020). Cesar is situated in Northern Colombia, near the border with Venezuela. The department is divided into 25 municipalities and is less densely populated with a population of over 1.3 million (Departamento Administrativo Nacional Estadística, Citation2020). Accordingly, Cesar contains more rural areas than Valle del Cauca (Ramírez Jaramillo & De Aguas, Citation2017).

According to the Leprosy Public Health Surveillance Protocol and the National Strategic Plan of Leprosy Prevention and Control, responsibility for the implementation of leprosy control activities in Colombia is mainly found at the departmental/district and municipal/local health directorates (INS, Citation2022; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social [MSPS], Citation2015). This includes appointing specific health professionals for the coordination of leprosy surveillance, active case finding and capacity building, including technical assistance to laboratories. Primary health services are responsible for the diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation if necessary. Both the WHO (Citation2018) and national guidelines consider clinical examination as the most important for diagnosis, possibly complemented with additional tests (slit skin smear test or biopsy) (INS, Citation2022).

Study population

The study population consisted of Colombian leprosy health professionals who fulfilled a job related to leprosy within Cesar and/or Valle del Cauca in Colombia at the time of the study. These included people working for leprosy-related non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as healthcare workers and the NGO’s national representatives, and health staff working for the leprosy programme in the national public health system. These participants presented unique experiences and expertise with leprosy diagnosis on various levels of healthcare provision and therefore they could share their diverse experiences with the delay in leprosy diagnosis. presents a summary of participant details.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Data collection and analysis

The participants were recruited through the existing professional network of the German Leprosy and Tuberculosis Relief Association (GLRA/DAHW) Colombia. To fulfil the inclusion criteria, the participants were either currently or recently (when quit within the last three years) fulfilling a role in leprosy healthcare that suggested expertise about the topic of diagnosing leprosy in Cesar and/or Valle del Cauca. Ten potential participants were contacted by email (by HNWD, DGEA) which consisted of information about the research, its aims, and the invitation for an interview. In the invitation email, it was highlighted that research participation was voluntary and that they were free to reject the invitation. Eight people responded to the invitation agreeing to take part in the study, one person did not respond and one person declined the invitation but recommended someone else in their network who was later contacted by email and agreed to participate in an interview. No further participants were invited due to the limited availability of experts and reaching the point of data saturation by the ninth interview.

In May-June 2023, nine semi-structured interviews were conducted with leprosy health professionals in Cesar and Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Interviews were conducted remotely (online) by the first author and audio-recorded with an external recording device. The choice to conduct interviews online allowed for a flexibility to collect interviews with participants who were physically present in different parts of Colombia. The preferred date and time of the participant were taken into account. Participants were offered the choice to speak in English or Spanish language. All nine participants chose to be interviewed in Spanish language. The interviews lasted 36:52 minutes on average, ranging from 22:30–46:04 minutes. Interviews followed an interview guide with mainly open-ended questions that was prepared in advance and reviewed by experts in the field of leprosy and qualitative research in the research team (see the final interview guide in Appendix 1). During the interviews, time was spent on introductions and explanation of the study. Participants were instructed to ask questions in case anything was unclear and were asked to tell about anything that they may find important concerning the topic. Additionally, the interviewer was free to ask further questions that arose from the information given by the participant; these questions aimed to be open questions to invite the participant to maximally elaborate on their views.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, and analysed using the method of thematic analysis (Green & Thorogood, Citation2018). A combination of deductive and inductive strategies was used for thematic analysis. The pre-determined themes that informed the interview guide included the perception of the moment of diagnosis, the perceived route to diagnosis, the perceived reasons for diagnostic delay, and suggestions to diminish the diagnostic delay. No new themes were generated during the analysis, however, sub-themes were added to reflect the specific complexities that emerge during the different steps of the care-pathway. In particular, focus was given to events before and after the moment when a patient gets in touch with health services.

Below, the analysis is presented following the defined themes with specific focus on the perceived reasons for diagnostic delay. After thematic analysis was completed, the different reasons were distinguished between individual-level, health system-level and community-level factors, which is reflected in the results section.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, the Francisco de Paula Santander University, Colombia (ethical clearance registration number: CEI-ISEM-03-2023: ENFERMERÍA) and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, the Netherlands (ethical clearance registration number: FHML/GH_2023.005). Informed written consent was obtained from the participants before data collection.

Results

Before scrutinising the pathways and delays of leprosy diagnosis, we firstly aimed to verify whether our participants perceive the moment of diagnosis in Cesar and Valle del Cauca as delayed. Participants were asked to share their thoughts on the moment of diagnosis of the leprosy patients who were diagnosed in 2022 or 2023. Regardless of profession or department of focus, participants perceived the moment of diagnosis as delayed. This delay was expressed in time (years or months) between noticing the first symptoms and obtaining the diagnosis, the number of consults that are necessary to receive a diagnosis, or symptomatic cases that remain undiagnosed. For example, one participant mentioned the following:

‘On average, it is delayed. I would say that the average [delay] is between three and five years.’ (Local project worker leprosy program, 12 years of experience)

Secondly, we mapped out a pathway of the general route to diagnosis of a leprosy patient in the two departments, following the results from the interviews. According to our participants, there seems to be a common route that leads to diagnosis. Leprosy patients get in touch with the health services either on their own initiative or via active case detection programmes via the public leprosy programme or an NGO. Once in touch with the health services, patients generally get referred to a dermatologist by their general practitioner, who will perform diagnostic tests and confirm the diagnosis. The diagnosis seems to mainly occur by complementary tests (biopsy and sometimes slit skin smear test) rather than clinically. In this second part of the route variations occur, as consultations by other specialists (such as infectious diseases, internal medicine or emergency services) might be included in the route too.

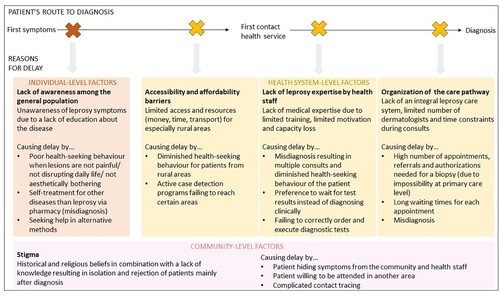

Based on the interview results, the reasons behind diagnostic delay can be characterised through the individual-level factors, health system-level factors, and community-level factors, with health system-level factors being highlighted as a major drive of delay. Below we provide a detailed examination of these factors. An overview of the various reasons for delay is presented in .

Figure 1. Reasons for diagnostic delay along the patient’s route to diagnosis according to leprosy health professionals in Cesar and Valle del Cauca.

Reasons for delay

Individual-level factors

According to the participants, people might not be able to recognise that certain symptoms that they experience might be leprosy disease, resulting in several scenarios once a person notices the first symptoms. First of all, this person might not seek help at all as leprosy disease usually begins with skin symptoms that do not give any pain and only show slow progress. For instance, one of the participants explained:

‘Here in Colombia, someone usually goes to the doctor when he is in pain. If there is no pain, it is not considered a priority to get a consult.’ (Social worker leprosy-related NGO, 26 years of experience)

When asked about the cause of this lack of awareness regarding leprosy symptoms among the general population, participants indicated the lack of knowledge and education about leprosy disease overall. Due to the low prevalence of leprosy and the non-urgent (not life threatening) character of the disease, leprosy campaigns do not have the same significance, emphasis and funding as other diseases, such as cancer or HIV.

Health system-level factors

Participants mentioned that affected persons might feel discouraged to seek medical help due to a lack of economic resources, transport or time. This especially applies to people residing in rural areas. Considering that leprosy mainly occurs among the lower socioeconomic classes, participants highlighted that people might rather not want to take time off from their jobs to seek help, especially when their symptoms are not severe. Simultaneously, it was mentioned that active case detection programmes are not executed to their full potential. One participant illustrated this as follows:

‘In general, the leprosy programs do not execute active case detection in rural areas. In general, case detection is done where it is the most accessible to do it.’ (Representative leprosy-related NGO, 28 years of experience)

Another health system-level factor that might delay the diagnosis is the lack of expertise of health staff. According to the participants, a major reason for the delay in diagnosis is that many doctors have the idea that leprosy does not exist anymore, which often leads to a misdiagnosis and treating the patient for other diseases than leprosy. For instance, one of the participants explained:

‘In general, leprosy is initially treated as mycosis. I would say that in ninety percent of the cases, leprosy is initially treated as mycosis. […] It is very rare that a person is diagnosed with leprosy disease during the first consult. That generally does not occur.’ (Representative leprosy-related NGO, 28 years of experience)

‘[We have seen] cases of people going through five dermatologists until arriving at a dermatologist that knew the disease and [was able to] diagnose leprosy.’ (Local project worker leprosy program, 12 years of experience)

Even when doctors do suspect leprosy, some participants felt like doctors often do not feel confident enough to clinically diagnose the patient, which leads to additional delays by doctors waiting for test results. The following participant elaborated on this:

‘The doctors of the health institutions … I think that they do not feel confident enough to confirm the case. Let’s say that they identify it, but they do not feel sure enough to diagnose it clinically. Instead they do not notify the case until they see a slit skin smear test or skin biopsy.’ (Local project leader leprosy program, 9 years of experience)

The underlying reasons for this lack of leprosy expertise were explained by a lack of education in university and limited motivation by doctors to attend trainings to improve their knowledge about leprosy. According to the participants, universities tend to scantily include leprosy in their medical curricula and hospital-university agreements that facilitated practical education seem to disappear. Explanations for these trends were sought in leprosy being a rare disease and limited budgets. This reveals the underlying political infrastructure contributing to the delay, specifically decision-making processes and (de)prioritisation of leprosy. Furthermore, health staffing seems to be an issue related to this lack of expertise. Due to a high turnover of health staff, knowledge capacity is thought to get lost. In addition, participants indicated that sometimes healthcare workers are hired to be in charge of the leprosy programme who do not possess the required knowledge and skills. Overall, this results in a limited number of doctors trained in leprosy.

Another health system-level factor causing delay in diagnosis involves the organisation of the care pathway, including the multitude of procedures necessary to obtain a diagnosis. The Colombian health system is organised in a way where various authorisation procedures are required for specialist referrals or complementary tests. For example, participants indicated that when a general practitioner refers the patient to a dermatologist, the patient must first go to his insurer (Entidad Promotora de Salud) to authorise the referral. Once authorised, the patient can make an appointment with the dermatologist. However, participants mentioned that this appointment might not be scheduled earlier than a few months, due to a limited number of dermatologists and leprosy not being considered an urgent disease. The following participant illustrates how this delays the diagnosis:

‘The problem in my country is the arbitration. […] For example, if I [as a general practitioner would] see a patient and I order a biopsy today, I have to send him to the dermatologist, which can take four or five months for him [the patient] to be seen by the dermatologist. The dermatologist sees him, orders the biopsy, [and then] it can take another two or three months before they do the biopsy, before they give him the control appointment with the result of the biopsy and finally, for him [the patient] to reach me [to receive treatment]. So it is a lot of arbitration. Many steps to be able to finally receive a positive result. So that causes a lot of delay in the diagnosis.’ (Dermatologist leprosy program, 8 years of experience)

Community-level factors

Participants mentioned that the actual consequences of the stigma linked to leprosy, described as rejection and isolation of leprosy patients, are mainly seen once patients already received their diagnosis. For instance, one participant explained:

‘[Once someone receives the diagnosis], it gets to being rejected by the family, the society, and often even by the health system itself.’ (Representative leprosy-related NGO, 10 years of experience)

‘When they are diagnosed, they want to keep their diagnosis silent. They don’t want to share it with their relatives, they don’t want to tell it. They don’t want to make it known that they have this condition.’ (Local project worker leprosy program, 12 years of experience)

Our participants thus highlighted how common health-seeking behaviour, misconceptions about skin symptoms and stigma among the community might contribute to the delay in diagnosis. This makes the important role of the underlying social infrastructure in diagnostic delay visible and possibly reveals the shortcomings of the current system in addressing these issues.

Recommendations by leprosy health professionals

Leprosy health professionals proposed several suggestions to diminish the delay in diagnosis. Changes within the health system leading towards a more integral leprosy care system and the strengthening of collaborations were recommended, as well as education and awareness-related interventions both among the general population and health staff. For the latter, it was suggested to pose special attention on the course of the disease and the meaning of ‘contagious’, which might currently still be misinterpreted by the general population, resulting in shock and stigma. According to the participants, education among health staff must focus on creating awareness that the disease still exists and creating the confidence to establish the diagnosis clinically. For example:

‘[For health staff] to be able to suspect the disease […] it is fundamental that, at least, the general theoretical topics and general concepts about the disease are known [among health staff].’ (Representative leprosy-related NGO, 28 years of experience)

Furthermore, the need for structural changes within the organisation of the health system was accentuated. To bypass delays caused by appointment procedures and waiting times, it has been mentioned to enable performing the biopsy at the primary care level. Along these lines, it was valued to work towards an integral leprosy care system where leprosy care is centralised in specialised sites. Certain locations do already successfully exist, such as the Pan American Health Centre in Cali (Valle del Cauca). This way, a general practitioner could refer a patient directly to a place that is in charge of evaluation, diagnosis and treatment. The delay caused by authorisations and referrals is then avoided. In addition, as is the case in Cali (Valle del Cauca), this centre could be in charge of the surveillance and follow-up of cohabitants. Participants highlighted that it is fundamental to improve active case detection. At least contact tracing activities should be executed properly, especially in endemic areas. Additionally, it was recommended to make better use of the existing information systems and national databases to give direction to interventions and the distribution of resources.

Discussion

Delay in leprosy diagnosis contributes significantly to the health burden of leprosy in Colombia, specifically in endemic regions like Cesar and Valle del Cauca. Based on nine in-depth expert interviews with leprosy health professionals in Colombia, our findings suggest that delay in leprosy diagnosis often consists of a fluid interplay of various barriers, including individual-level, health system-level and community-level factors. Due to the multitude of possible barriers along the way to diagnosis, it seems very difficult to currently avoid at least some degree of delay for leprosy patients in Cesar and Valle del Cauca. Our results imply that the diagnosis in both departments might indeed be delayed in terms of months or even years, as was suggested by previous studies in Colombia (Gómez et al., Citation2018; Guerrero et al., Citation2013; Rodríguez Torres et al., Citation2023). Moreover, building on our participants’ reflections, it is possible to suggest the presence of potentially undiagnosed or hidden cases within the departments. This generates the hypothesis that leprosy prevalence rates and G2D rates might in reality be higher than the rates measured by the National Health Institute (INS, Citation2023).

The highlighted reasons for the delay in leprosy diagnosis from our study are in line with findings from other countries. For example, the unpreparedness of health staff to diagnose leprosy has been observed before in Brazil by Cavalcante et al. (Citation2020); Osorio-Mejía et al. (Citation2020) mentioned geographical and economic barriers for patients to access diagnosis in Peru. Despite the aim by the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MSPS, Citation2015) to eradicate leprosy by 2025, leprosy seems to have gained a low priority on the national health agenda. A relatively low prevalence, the non-deadly character of the disease, and not being officially considered as a public health issue might have contributed to the perception that leprosy is controlled or eliminated. This seems to be a tendency in more countries around the world with lower leprosy prevalence rates and might explain the lack of commitment by doctors and the low impact of awareness campaigns among communities (Muthuvel et al., Citation2017; Nicholls et al., Citation2003; Zaw et al., Citation2020).

Within Colombia, our study provides further context to research by Gómez et al. (Citation2018) on how five or more consults might be reached before obtaining the diagnosis. Whereas a study by Rodríguez Torres et al. (Citation2023) found that leprosy patients who were treated in private sector clinics were less likely to experience delay compared to those attending public services, this was not established as a major theme in our study.

Moreover, whereas national and WHO guidelines emphasise clinical examination as the basis for diagnosis, our study highlighted the limited medical expertise to perform such examination. This suggests the discrepancy between diagnostics guidelines and the reality of clinical practice where there is a lack of clinical expertise concerning leprosy. Considering that our study was conducted just after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, it is interesting that participants barely mentioned the topic of the pandemic as a reason for delay. According to Cáceres-Durán (Citation2022), the pandemic clearly disrupted the health system, resulting in a limited detection of leprosy cases and an amplification of G2D cases. The fact that participants barely mentioned this topic might reflect the structural character of the problem of delay in diagnosis and suggests that the infrastructural challenges to diagnosis were already present before the impact of the pandemic.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, we included only two regions in this research, which means that the findings are not generalisable to the whole of Colombia. The two selected regions are, however, two of the endemic departments and were carefully selected based on contrasting features, such as G2D cases above and below the national average. Second, the research involved a limited number of participants compared to the size of both departments. Despite various efforts, it was difficult to locate leprosy health professionals in both departments, which could have resulted in missing certain perceptions. Considering the nationwide connections and experience of the GLRA/DAHW, a probable explanation for this difficulty in locating participants could be that there actually is a limited number of leprosy health professionals in the departments. This also reflects the results of our interviews. Also, being dependent on the connections of the GLRA/DAHW for recruitment of the participants, the possibility of some degree of selection bias cannot be ruled out. Third, our study represents only the perceptions of leprosy health professionals. This might have possibly led to missing out on crucial perspectives from other important stakeholders related to the topic of delay in leprosy diagnosis. Further research is necessary to substantiate the findings of this study, possibly by obtaining the perspectives of other stakeholders, such as patients.

Despite slight progress over the years, systemic changes seem insurmountable to lower the number of G2D cases and fulfil the objectives of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (MSPS, Citation2015) and the WHO (Citation2017) to eliminate Leprosy. The multitude and complexity of the various reasons for delay imply a multifactorial approach. To avoid delays caused by the number of appointments, procedures and waiting times, it would be beneficial to develop a referral route that guides the patient from the general practitioner to an integral leprosy care centre. Patient-centred stepwise referral systems have been proposed before to avoid delays in other endemic regions in Colombia (Gómez et al., Citation2018). Strategies should be developed to ensure adherence to contact tracing protocols and the surveillance of contacts. Additionally, these centres should have the expertise to diagnose clinically and possess the tools for complementary tests (including biopsy).

Based on the results of this study and following the suggestions from our research participants, we summarised the main recommendations to lower diagnostic delays in Cesar and Valle del Cauca below (see ).

Table 2. Recommendations to lower diagnostic delays in Cesar and Valle del Cauca based on our study.

In conclusion, our study identifies the various factors contributing to delay in leprosy diagnosis in Cesar and Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Delay often consists of a fluid interplay of various factors and cannot be narrowed to one single reason, implying a multifactorial approach to redress the current barriers. To lower delays in our study setting, recommendations for improvement include implementing structural changes within the health system to organise integral leprosy care centres with strict contact tracing protocols. Additionally, highlighting leprosy in the medical curriculum is recommended, as well as interventions among the general population aiming to reduce stigma and create awareness about leprosy. Collaboration among stakeholders is crucial to reinvigorate attention and commitment towards leprosy eradication, especially considering its relatively low prevalence in Colombia.

Data sharing

The data from this study are not available for open access but can be requested directly from the first or corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express special gratitude to Martha Cecilia Barbosa Ladino, Eveleidis Rafaela Cordoba Brizuela, Hugo Marin Loude, Lizeth Andrea Paniagua Saldarriaga, Alberto Rivera, Jennifer Santa Yepes, Natalia Valderrama Cuadros, Lucrecia Vasquez Acevedo and Lorena Villamarin Lopez for their expertise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Cáceres-Durán, M. (2022). Comportamiento epidemiológico de la lepra en varios países de América Latina, 2011-2020. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 46, 1. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2022.14

- Cavalcante, M. D. M. A., Larocca, L. M., & Chaves, M. M. N. (2020). Multiple dimensions of healthcare management of leprosy and challenges to its elimination. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 54, e03649.

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional Estadística. (2020). Colombia. Demographic indicators by department 1985-2020. https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/en/statistics-by-topic-1/population-and-demography/population-series-1985-2020

- Dharmawan, Y., Fuady, A., Korfage, I., & Richardus, J. H. (2021). Individual and community factors determining delayed leprosy case detection: A systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15(8), e0009651. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009651

- Dharmawan, Y., Fuady, A., Korfage, I., & Richardus, J. H. (2022). Delayed detection of leprosy cases: A systematic review of healthcare-related factors. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 16(9), e0010756. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010756

- Gómez, L., Rivera, A., Vidal, Y., Bilbao, J., Kasang, C., Parisi, S., Schwienhorst-Stich, E. M., & Puchner, K. P. (2018). Factors associated with the delay of diagnosis of leprosy in north-eastern Colombia: a quantitative analysis. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 23(2), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13023

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research. SAGE.

- Guerrero, M. I., Muvdi, S., & León, C. I. (2013). Retraso en el diagnóstico de lepra como factor pronóstico de discapacidad en una cohorte de pacientes en Colombia, 2000 - 2010. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 33(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892013000200009

- Instituto Nacional de Salud. (2022). Protocolo de Vigilancia en Salud Pública de Lepra. Versión 7. https://doi.org/10.33610/infoeventos.53s.7

- Instituto Nacional de Salud. (2023). Boletín Epidemiológico Semanal - Semana epidemiológica 02. https://www.ins.gov.co/buscador-eventos/BoletinEpidemiologico/2023_Bolet%C3%ADn_epidemiologico_semana_2.pdf

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. (2015). Plan Estrategico Nacional de Prevención y Control de la Enfermedad de Hansen: “Compromiso de todos hacia un país libre de enfermedad de Hansen” 2016-2025. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/PP/ET/Plan-strategico-enfermedad-hansen-2016-2025.pdf

- Muthuvel, T., Govindarajulu, S., Isaakidis, P., Shewade, H. D., Rokade, V., Singh, R., & Kamble, S. (2017). ““I wasted 3 years, thinking it’s Not a problem”: patient and health system delays in diagnosis of leprosy in India: A mixed-methods study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(1), e0005192. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005192

- Nicholls, P. G., Wiens, C., & Smith, W. C. (2003). Delay in presentation in the context of local knowledge and attitude towards leprosy—The results of qualitative fieldwork in paraguay. International Journal of Leprosy and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, 71(3), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1489/1544-581X(2003)71<198:DIPITC>2.0.CO;2

- Osorio-Mejía, C., Falconí-Rosadio, E., & Acosta, J. (2020). Interpretation systems, therapeutic itineraries and repertoires of leprosy patients in a low prevalence country. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública, 37(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2020.371.4820

- Ramírez Jaramillo, J. C., & De Aguas, J. (2017). Configuración territorial de las provincias de Colombia: ruralidad y redes. https://hdl.handle.net/11362/40852

- Rodríguez Torres, E., Beitia Cardona, P. N., Eslava Albarracín, D. G., Fastenau, A., Penna, S., & Kasang, C. (2023). Epidemiological trends and diagnosis delay for Hansen's disease in Valle del Cauca - Colombia 2016-2021. Leprosy Review, 94(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.94.2.111

- Roldán González, C. L., & Velasco Franco, L. S. (2020). Plan de Desarrollo Departamental 2020 - 2023 Valle del Cauca Versión preliminar. https://www.valledelcauca.gov.co/loader.php?lServicio=Tools2&lTipo=viewpdf&id=41713#:~:text=Al%20considerar%20la%20demograf%C3%ADa%20del,%C3%BAltimo%20censo%20poblacional%20a%C3%B1o%202018

- World Health Organization. (2017). Towards Zero Leprosy. Global Leprosy (Hansen's disease) Strategy 2021-2030. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290228509

- World Health Organization. (2018). Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/274127

- World Health Organization. (2022). Leprosy - number of new Leprosy cases Data by country. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A1639

- Zaw, M. K. K., Satyanarayana, S., Htet, K. K. K., Than, K. K., & Aung, C. T. (2020). Is Myanmar on the right track after declaring leprosy elimination? Trends in new leprosy cases (2004–2018) and reasons for delay in diagnosis. Leprosy Review, 91(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.47276/lr.91.1.25