ABSTRACT

Alcohol harms threaten global population health, with youth particularly vulnerable. Low – and middle-income countries (LMIC) are increasingly targeted by the alcohol industry. Intersectoral and whole-of-community actions are recommended to combat alcohol harms, but there is insufficient global evidence synthesis and research examining interventions in LMIC. This paper maps existing literature on whole-of – community and intersectoral alcohol harms reduction interventions in high-income countries (HIC) and LMIC. Systematic searching and screening produced 61 articles from an initial set of 1325: HIC (n = 53), LMIC (n = 8). Data were extracted on geographic location, intersectoral action, reported outcomes, barriers, and enablers. HIC interventions most often targeted adolescents and combined community action with other components. LMIC interventions did not target adolescents or use policy, schools, alcohol outlets, or enforcement components. Programme enablers were a clear intervention focus with high political support and local level leadership, locally appropriate plans, high community motivation, community action and specific strategies for parents. Challenges were sustainability, complexity of interventions, managing participant expectations and difficulty engaging multiple sectors. A learning agenda to pilot, scale and sustain whole-of-community approaches to address alcohol harms in settings is crucial, with consideration of local contexts and capacities, more standardised methods, and a focus on community-driven action.

Introduction

Harmful use of alcohol is one of the most serious challenges to population health globally (World Health Organisation, Citation2018b). It directly hinders progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in areas as diverse as maternal and child health, infectious diseases (including HIV and TB) (Daniels et al., Citation2018; Schensul et al., Citation2010), noncommunicable diseases, traumatic injury, poisoning and mental health (Sileo et al., Citation2020; World Health Organisation, Citation2018b). Alcohol is also a known carcinogen (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; World Health Organisation, Citation2018b), and a dependence-causing psychoactive drug (Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020).

LMIC regions are particularly vulnerable to alcohol harms, given their contexts of intersecting inequalities (Larson et al., Citation2016; Logie et al., Citation2024), cultural and social dynamics, and alcohol marketing practices linked to heavy episodic drinking (Morojele et al., Citation2021). This indicates a pressing need to investigate harm reduction measures. Recognition of alcohol harms, and national policy responses, have seen alcohol consumption reduced in HIC, leading to transnational alcohol conglomerates strategically targeting new markets in LMIC regions such as Africa (Walls et al., Citation2020). The alcohol conglomerate Diageo, for example, saw sales increase in Brazil, China, India, and Turkey from 10% to 40% between 2000 and 2015, while global sales in Europe and North America fell from 83% to 42% over the same period (Anderson et al., Citation2018).

While some countries have introduced policy measures to combat alcohol harms, and experienced stabilised consumption rates, few have adopted other WHO ‘best buys’ and consumption in LMIC has generally risen (Ayano et al., Citation2019; Morojele et al., Citation2021). Alcohol-attributable deaths are high in LMIC, and countries lack resources to combat alcohol related harms (El Hayek et al., Citation2024; Leung et al., Citation2019). An analysis of the global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries found that in Sub-Saharan Africa, 5.1% (95% UI 4.3–6.0) of all disability adjusted life years lost (DALYs) were attributable to alcohol (Degenhardt et al., Citation2018). These issues are compounded by the demographic composition of LMIC regions.

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to alcohol harms (Leung et al., Citation2019), and make up a large proportion of LMIC populations. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), for example, is projected to contain 24% of the global adolescent population by 2030 (Melesse et al., Citation2020), and development in LMIC depends on the health of their adolescents (World Health Organisation, Citation2018a). Even in countries where alcohol use is illegal, such as Iran, alcohol use is prevalent among youth with substance use disorder (El Hayek et al., Citation2024). Although adolescents in HIC have greater access to alcohol, consumption in LMIC is more commonly linked to intoxication. In a South African study, for example, nearly half of adolescents who consumed alcohol were heavy episodic drinkers (Harker et al., Citation2020). Authors recommended multi-level and community-based approaches for their increased sense of community ownership and sustainability to target the problem (Leung et al., Citation2019).

This is in keeping with the WHO Strategy on Alcohol, which recommends a range of evidence-based interventions for population-level alcohol harms reduction (World Health Organisation, Citation2010). These ‘best buys’ focus on higher-level policy options including taxation, restricting availability of alcohol, advertising, and minimum unit pricing (Matanje Mwagomba et al., Citation2018). Programmes in Russia, Thailand and Lithuania have shown that multi-pronged strategies to address alcohol harm can be effective, and form part of a growing body of evidence indicating that interventions based on WHO ‘best buys’ and ‘good buys’ are cost effective and impactful (World Health Organisation, Citation2019). Without considering community contexts, however, interventions may be counterproductive and have unanticipated consequences (Clough et al., Citation2018).

The need to address the specific contexts of communities in which harmful drinking occurs is widely recognised (Flewelling & Hanley, Citation2016; Leddy et al., Citation2021; World Health Organisation, Citation2018b). Communities have the greatest insight into their specific problems of alcohol and substance-related harms and are crucial to realising sustained changes in drinking behaviour and norms (Stockings et al., Citation2018). Causes and impacts of alcohol harms are multifaceted, and interventions to reduce harms likewise require approaches that span varying determinants and are multisectoral in nature (World Health Organisation, Citation2010). Such action should include measures to reduce demand as well as supply and involve a mix of local level action accompanied by higher level policy or legislative support (Jones et al., Citation2018; Shakeshaft et al., Citation2014; Stockings et al., Citation2018). Community engagement forms part of a ‘systems thinking’ approach, and community capacity has been harnessed in diverse fields of health promotion and harms reduction (Felmingham et al., Citation2023).

Intersectoral (or multisectoral) action refers to relationships that can be both horizontal between sectors, or vertical, between different governmental levels, for example global institutions partnering with national or regional government organisations, or national governments with states (Public Health Agency of Canada & Equinet, Citation2007). Such action refers to a deliberate and purposeful relationship where there is negotiation and distribution of power, resources, and capabilities between various stakeholders and involves different degrees of collaborative action ranging from integration to co-operation (Axelsson & Axelsson, Citation2006). In this review, we use the terms ‘whole-of-society’ interchangeably with ‘whole-of-community’ to refer to intersectoral interventions that typically target a well-defined population within a delimited geographical region and include the implementation of several simultaneously coordinated interventions across various community settings (e.g. schools, sports clubs, social services, law enforcement, etc.). By activating multiple community stakeholders in the intervention process, the goal for these types of interventions is to delay the onset of alcohol use and decrease general alcohol consumption.

Despite wide acknowledgement of the need for community-based and whole-of-community interventions for alcohol harms reduction, there is a lack of well-reported evidence synthesis about this subject. One systematic review and meta-analysis of whole of community interventions to reduce alcohol harms, which included 24 trials, reported a significant reduction in risky drinking but no impact on past month alcohol use or binge drinking (Stockings et al., Citation2018). The review concluded that the studies were subject to high risk of bias.

There is a paucity of research that explores intersectoral action targeting populations or communities in (LMIC) (Greene et al., Citation2023; Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020). The aim of this scoping review was to map and synthesise interventions that use a whole-of-community approach and intersectoral action, or operate at population level, and include the reduction of alcohol harms as an outcome. This review includes global studies, but the qualitative analysis focusses on LMIC. It explores the geographic location of these interventions, target populations and groups, intervention components, reported outcomes, and examines the level of community engagement where applicable by noting whether programmes engaged communities or were community-led. We outline common barriers and enablers to implementation, with the intention that this will inform ways to design locally appropriate, sustainable interventions in the future.

Methods

Protocol

The research protocol (Okeyo et al., Citation2022), was based on Arksey and O’Malley’s framework (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010) and adhered to the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Steps in conducting the review

We followed six stages: (1) identify the research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) data summary and results synthesis; and (6) consultation.

Step 1: Research questions were:

(1) What intersectoral, whole of society or community approaches (interventions) have been used to modify alcohol-related harms? (2) What are the settings, delivery methods, theoretical bases and reported effectiveness of these interventions, especially in terms of reducing harm to children and families? (3) To what extent have these interventions been carried out in both high income and LMIC contexts?

Step 2: Identifying relevant studies

We included all studies published in English between 2010 and 2021 (2010 was chosen as the start of the search since it was the year in which the WHO Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol was published), and which reported on community-based, collective, multisectoral or whole-of-society approaches to reducing harms arising from alcohol use. Based on search strategy guidelines (The Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2015), and with assistance from a university faculty librarian, we first conducted iterative preliminary searches of PubMed, Web of Science and CINAHL. This aided in developing an overview of existing literature and identifying relevant keywords to define search terms (). Once finalised, these terms were used to search titles and abstracts in four electronic databases: SCOPUS, CINAHL Plus, Web of Science and PubMed. Supplementary File 1 details the search strategy.

Table 1. Overview of search terms.

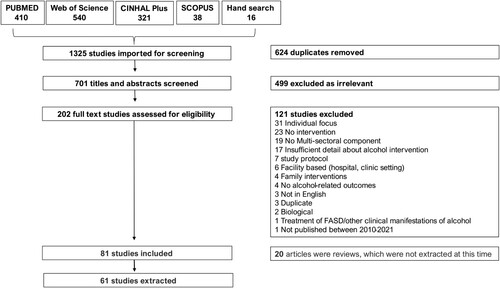

A systematic search of online databases delivered a total of 1309 records. Consultation and hand-searching citations resulted in sixteen additional records. A total of 1325 records were uploaded to Covidence, of which 624 duplicates were removed. The remaining 701 titles and abstracts were screened, and 499 were excluded as irrelevant. Following this, 202 full text articles were assessed for eligibility, a further 120 excluded, based on the exclusion criteria presented in Box 1, leaving a total of 81 records. Twenty of these were reviews which we set aside to focus on original research, resulting in sixty-one articles being included for extraction.

Articles were excluded if:

they were not in English.

they did not include an intervention.

they included an intervention that was only biological, technological or pharmacotherapeutic in nature (for example, measurement of blood alcohol levels).

they included interventions which treated foetal alcohol spectrum disorder, or other clinical manifestations of alcohol consumption.

they included an intervention which featured individual-based interventions including one-on-one counselling sessions or motivational interviews designed for individuals or families.

the intervention was facility-based, in a hospital or clinic setting; and

where interventions were not clearly described.

Step 3: Study selection

Each title and abstract was screened by two reviewers for eligibility. To establish the reliability and precision of the process, screening was piloted using twenty-five titles and abstracts to allow the team to gain clarity on exclusion criteria (Box 1).

Eligible articles proceeded to full text review, where two reviewers again assessed each for relevance as per our criteria. In cases where the full text was not available online, we attempted to retrieve these through a library database, and thereafter from the author directly. Where all attempts were unsuccessful, articles were excluded and noted to be due to non-availability. Where either of the two reviewers disagreed on whether an article should be included, or on the reason for exclusion, this was discussed in weekly team meetings until consensus was reached.

Ongoing studies and study protocols were included if they fitted the criteria above. Review papers were excluded as these did not describe original research but were used for reference during write-up. Papers that described interventions in LMIC contexts were tagged for further analysis. Articles that did not fit the eligibility criteria but presented useful background information were also tagged for future reference.

Step 4: Data charting

A data extraction template was developed using Microsoft Excel, piloted, and amended by the research team. Data were extracted by one team member, and reviewed by another, to ensure coherence and completeness. In all, four team members did the extractions and three reviewed these data. Issues were discussed in weekly meetings.

Data elements included study characteristics (date of publication, study location and design, target populations), intervention characteristics (reported outcomes, primary and secondary outcomes, intervention components, intersectoral elements, theoretical basis, implementation barriers and enablers). After initial data extraction was completed, three team members reviewed it and noted that interventions often operated at community level with the objective of reducing risk or harms for a particular group within that community. For example, an intervention within a school community involved parents, teachers, and students to reduce risky drinking for adolescents.

It was therefore decided to categorise and report both the type of community, as well as the target group involved ().

Table 2. Categories of communities & target groups.

Categorising communities and target populations

We noted that the term ‘community’ had different meanings across the data set. Based on input from the research team and building on descriptions by Midford and Shakeshaft (Midford & Shakeshaft, Citation2016), We categorised communities as (1) common purpose (schools, sports clubs) (2) common risk (heavy drinkers) (3) shared heritage (Indigenous groups) (4) shared location (geographic area, neighbourhood, states)

Based on interventions described within the data set, target groups were categorised as (1) adolescents (ages 15–19), (2) both adolescents & young people (age 20–24), (3) adult drinkers (when age was not specified), (4) all community members, (5) marginalised groups (those within communities who did not reflect mainstream norms, such as the homeless or excessive drinkers).

We did not assess the quality of studies as this was beyond the remit of this review. Study results were categorised according to authors’ descriptions of intervention outcomes in narrative for qualitative studies or using effect sizes for quantitative studies as (1) mixed/unclear (some positive and some negative results, or results were neither overall positive or negative, or results were not clearly stated), (2) no change, or (3) positive. Studies were excluded from assessment of outcomes where they described the process of developing an intervention or policy, but did not report outcomes, or where they reported a single case study.

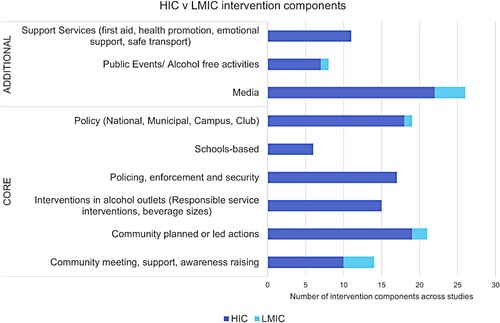

Categorising intervention components: We viewed interventions as plans constituted of distinct elements, or components. Intervention components were categorised as either ‘core’ or ‘additional’. Core components were fundamental to interventions and included community engagement, and structural or sectoral action. These included (1) community meetings, support, and awareness raising, (2) community-planned or led actions, (3) schools-based programmes, (4) interventions with alcohol outlets, (5) policing, enforcement, and security, and (6) policy (national, municipal, campus, club).

Additional components functioned as adjuncts to core components. These were (1) support services (first aid, health promotion, emotional support, safe transport), (2) public events/ alcohol free activities, (3) media. The term ‘media’ was used to describe a wide variety of awareness-raising measures enacted through online, broadcast and print media, as well as the use of posters in public spaces (). Each intervention was composed of at least one core component, sometimes accompanied by additional components.

Table 3. Intervention categories & components.

Step 5: Results synthesis

Descriptive analysis of studies was conducted, and information was categorised per the data extraction template. Thematic and content analysis was carried out to produce a qualitative synthesis of patterns, similarities and contrasts which emerged across and between LMIC and HIC interventions.

Where analysis of multi-sectoral interventions is reported, we focus on studies in LMIC, which are a neglected area of study, where there is a need to better understand existing programming, and which are an area of focus for future market growth by the alcohol industry (Walls et al., Citation2020).

Step 6: Consultation

Discussions were held with an advisory group at the beginning of the search process, and preliminary analysis was presented for feedback at a stakeholder consultation later in 2021. Advisory group members and key stakeholders included representatives from local government, research organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with an interest in alcohol harms reduction.

Results

Based on the results of the analysis, the PRISMA flowchart depicting the screening process is presented below, followed by an overview of the study characteristics of all the included studies. The results of the qualitative content analysis are then discussed, drawing out key themes noted in terms of the type of approach used, reported impacts, and the intervention components. Thereafter, we focus in detail on studies from LMIC countries.

provides a PRISMA flowchart describing the selection of studies. describes characteristics of included studies.

Table 4. Characteristics of included studies.

Study characteristics

Publication dates

There was a steady production of articles over the review period, with an annual total number of publications being mostly 5 between 2010 and 2021, with fewer published in 2011 (n = 2) and more published in 2012 (n = 9), 2014 (n = 8) and 2018 (n = 14).

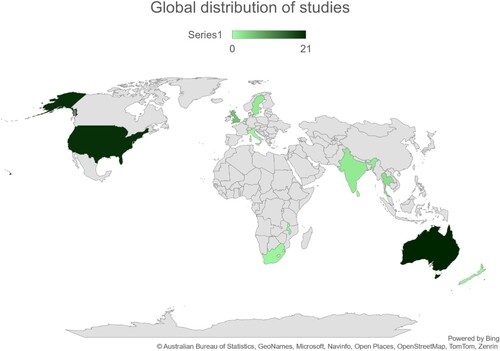

Global distribution of studies

Of the total (N = 61) studies, (n = 8) were in LMIC and (n = 53) in HIC (). Three LMIC studies originated in Thailand, two from India, and one each from South Africa, Malawi, and Sri Lanka. None were from Central or South America. Most studies in high-income countries were undertaken in Australia (n = 21), the U.S.A. (n = 20), and the UK (n = 6). The remaining studies (n = 6) were conducted in Sweden, Netherlands, Italy, and New Zealand.

Study designs

For HIC there was a range of study designs used, however, the majority were programme evaluations (n = 19), followed by cluster-randomised trials (n = 15). For LMIC, the most used study designs included non-randomised trials, programme evaluations and participatory action research. None of the LMIC studies used observational, or cluster-randomized trial designs.

Study populations and target groups

The most common type of community was that of shared location for both HIC (n = 25), and LMIC (n = 8). For HIC, shared heritage and common purpose definitions of community were equally common (n = 12), and the community of common risk was least frequently the focus of included studies (n = 4). Within these communities, HIC studies most often targeted adolescents (n = 18), all community members (n = 15), adult drinkers (n = 12), marginalised groups (n = 3) and adolescents as well as young adults (n = 2). LMIC studies only targeted adult drinkers (n = 5) or the whole community (n = 3). Adolescents were not targeted in any LMIC interventions.

Outcomes

HIC studies: (n = 2) were excluded from assessment of, (n = 4) had no change, (n = 16) had outcomes with mixed results, and (n = 31) had positive outcomes.

LMIC studies: (n = 3) were excluded from assessment of outcomes, (n = 5) had positive outcomes.

Intervention components

LMIC studies relied mainly on community action and engagement (). One study was a description of multi-sectoral development of national alcohol policy (Matanje Mwagomba et al., Citation2018). Policy development was not undertaken in conjunction with community action or other components. LMIC interventions incorporated elements of activity related to media, and public or alcohol-free events.

In contrast, HIC interventions incorporated a wider range of activities, in varying combinations. HIC interventions often used community planned or led action, as well as community engagement through meetings, support and awareness raising. These were sometimes used alone, but usually combined with other core components such as school-based activities, policy, law enforcement and interventions in alcohol outlets. The use of media was a common adjunct, while support services and public events were used less often.

Results of analysis: A closer look at intersectoral, whole-of-society or community approaches

This section examines intervention components in greater detail, focussing particularly on LMIC studies, where harms reduction work needs to be most strengthened. Supplementary file 2 shows extraction of HIC data on geographic location, interventions and implementation barriers and enablers.

High income country approaches

Multi-component and multi-sectoral interventions were common in HIC studies. Sectors involved in these interventions included schools, religious organisations, sporting associations, police, public prosecution, municipalities, and engagement with alcohol serving and sales establishments. A major focus was educating and sensitising the population on alcohol-related problems with specific attention to reaching adolescents and youth through parent committees, schools, religious and sporting associations. Components were varied and included digital technology, health education, alcohol regulation, and enforcement across multiple settings (Bagnardi et al., Citation2011; Jansen et al., Citation2016; Quigg et al., Citation2018)

Reported enablers in HIC included specific strategies for parents (knowledge transfer, raising awareness and increasing parenting skills) (Jansen et al., Citation2016). Having a clear intervention focus complemented by high political support and leadership at the local level was also identified to be important (Schelleman-Offermans et al., Citation2014). Barriers to intervention success focused on long-term sustainability with varying levels of lasting effect, due potentially to intervention fidelity and/or differences in structural (e.g. partnership working practices) and cultural (e.g. alcohol consumption) factors between settings. Lack of support from the local authorities was also identified as a barrier (Schelleman-Offermans et al., Citation2014).

Low-and-middle income country approaches

In LMIC, 7 of 8 studies reported community level interventions (5 community level, 2 community led) (). Of the five that examined outcomes, all had positive study impacts according to self-reported surveys measuring changes in attitudes and behaviour, or qualitative research exploring the impact of the intervention more broadly on the participants involved (Areesantichai et al., Citation2013; Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; Matanje Mwagomba et al., Citation2018; Oladeinde et al., Citation2020; Pelto & Singh, Citation2010; Schensul et al., Citation2010; Witvorapong & Watanapongvanich, Citation2020).

Table 5. Intervention components.

Two LMIC studies which described community-led actions were based on participatory action research (Oladeinde et al., Citation2020). The Tailored Goal Oriented Community Brief Intervention was delivered in Thailand (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014), and operated at individual level (goal setting) and community level (12 sessions of family alcohol education visits) and found substantial and significant reduction in drinking and alcohol intake at 6 month follow up. In South Africa, 48 stakeholders in 3 rural villages identified problems and formulated action plans in 16 workshops over 7 consecutive weeks (Oladeinde et al., Citation2020).

Both interventions experienced community empowerment as a positive outcome of the process. Communities themselves identified alcohol use as problematic, and jointly planned and executed interventions. Researchers found that communities were motivated, and had the capacity, to effect change and work within multi stakeholder partnerships. The expanded use of these methods was recommended to distribute power to those most affected by health challenges (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; Oladeinde et al., Citation2020).

Although the five remaining community-linked interventions in LMIC were not led by communities, strong community engagement was central to these approaches. In two Thai studies (Areesantichai et al., Citation2013; Witvorapong & Watanapongvanich, Citation2020), ‘community reinforcement’ created enabling environments for interventions by imposing social consequences for participants. Accountability for reduced alcohol consumption was enhanced as alcohol users publicly set their own goals, and the support of close-knit communities enhanced adherence to these commitments. Interventions were strengthened through appropriateness to community and the cultural contexts and were characterised by intense multisectoral activity.

Intensity was likewise a hallmark of three articles which reported the use of street theatre to facilitate community education on alcohol harms. Two articles reported on the Rishta project in India (Pelto & Singh, Citation2010; Schensul et al., Citation2010). Scripts for street plays were developed following 18 months of formative research, and were performed a total of 150 times, with each performance followed by community meetings, and supported by posters exhibitions, televised presentations shown in 22 locations, and other printed material (banners, pamphlets). A Sri Lankan street-theatre intervention delivered over 3 months was similarly multi-component (traditional street theatre, print media, group discussions and brief individual interventions), and its authors reported sustained reduction in alcohol use at two-year follow up, and the spontaneous formation of a community group which eliminated illegal sources of alcohol (Siriwardhana et al., Citation2013).

The above studies describe caveats: Lengthy and rigorous interventions were demanding to implement (Areesantichai et al., Citation2013), it was difficult to engage sectors outside of health such as community safety and policing, youth participants sometimes dominated discussions and were disruptive, some community members were dissatisfied with levels of reimbursement, and researchers had to manage participants’ expectations of quick results from the participatory process and identify aspects of action agendas that might expose community members to harm, for example monitoring the activity of taverns (Oladeinde et al., Citation2020). Interventions should be carefully planned and documented, and interpersonal dynamics within collaborations should be considered (Pelto & Singh, Citation2010). The success of interventions is context-specific, so although ‘community reinforcement’ may be effective in Thailand, where community bonds are strong and fundamental to society, this influence may be weaker in Western contexts where community networks are less robust (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014).

Promising programmatic elements were described as intervention simplicity (Areesantichai et al., Citation2013), cultural and local appropriateness of plans, high participant motivation (Pelto & Singh, Citation2010), community support which reinforces commitment to alcohol harms reduction (Witvorapong & Watanapongvanich, Citation2020), empowering participants and making them partners and implementers (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; Oladeinde et al., Citation2020), activity of community forums and action groups (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; Siriwardhana et al., Citation2013), and collaborative meetings and community control which helped to refine the problem definition and reach deeper understanding of issues (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014; Oladeinde et al., Citation2020). In the case of the Tailored Goal Oriented Community Brief Intervention, authors note that its delivery through home visits could feasibly be incorporated into health programmes using similar methods, and that it may be possible to achieve positive results even if the intervention is applied with less intensity (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014) .

Table 6. LMIC interventions.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to examine whole-of-community, community-based and intersectoral approaches as a strategy for addressing alcohol harms reduction globally. Previous reviews have examined different aspects of alcohol harms reduction, for example in the context of homelessness (Novotna et al., Citation2023), strategies for enhancing school-based harms reduction practice (Wolfenden et al., Citation2017), global and regional impacts of alcohol use on public health (Park & Kim, Citation2020) and home-based abstinence support from community health workers (Jirapramukpitak et al., Citation2020). We identified 61 studies that made use of whole-of-community and multisectoral approaches to address alcohol-related harms. The majority (n = 53) were drawn from high income countries, and from the U.S.A. and Australia in particular. The few which did originate in LMIC focussed on communities defined by shared location, did not target youth or adolescents, and reported outcomes in such a way that it was difficult to categorise or summarise results. Interventions in HIC included multisectoral components not found in those from LMIC, such as the involvement of schools, alcohol outlets, law enforcement or policy measures, or support services.

Whole-of-community interventions for substance and alcohol abuse were the subject of a systematic review (Stockings et al., Citation2018), which estimated the effectiveness of programmes. Due to its methodology the review excluded interventions without parallel comparison groups, or which were limited to only one community setting, and therefore did not capture the broader scope of community-based interventions in LMIC, which commonly used qualitative study designs. Whole-of-community interventions were reported to show limited effectiveness in reducing population level harms arising from alcohol and other drug use (Stockings et al., Citation2018), although there was evidence that they might mitigate outcomes. It was suggested that future interventions should work towards using standardised outcomes and measures to permit easier evaluation and comparison, and that reporting on interventions should be strengthened using best-practice guidelines. The review also recommended that interventions should employ evidence-based approaches like alcohol regulation, restricted marketing, and brief interventions in health care facilities and workplaces. A systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions for alcohol harms reduction (Greene et al., Citation2023) made similar recommendations for further and more standardised research to understand what is required for effective intervention.

Although the abovementioned systematic reviews differed in their aim and scope from our work, common findings are that intervention composition is heterogenous, making it difficult to summarise and compare them, and develop guidelines. The issue of intervention heterogeneity was also noted by other reviews in LMIC settings (Greene et al., Citation2023; Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020), and by reviews which examined alcohol harms reduction efforts more broadly (Beckwith et al., Citation2023; Wolfenden et al., Citation2017). Community-based interventions have an important role to play in addressing alcohol harms (Flewelling & Hanley, Citation2016; Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020; McKay et al., Citation2018; Quigg et al., Citation2018; Siriwardhana et al., Citation2013), but without clear evidence as to how these should be structured, or best practice guidelines for LMIC, there is likely to be limited investment in their implementation or scale up.

This review notes that the concept of ‘community’ can be understood in different ways, also linked to varying cultural norms and values. Western communities may view drinking as an individual choice, and lack the reinforcing capacity found in LMIC settings (Jongudomkarn, Citation2014). In keeping with this, literature guiding community-based participatory research found diverse conceptions of community, but unified by the idea that a community is a group of people with diverse characteristics who are linked by social ties, share common perspectives, and engage in joint action in geographical locations or settings (Kathleen M MacQueen et al., Citation2001). Authors note the need to consider cultural contexts when engaging communities, to appropriately harness their capacity.

A key finding of our work is the paucity of studies from LMIC. This is echoed by other reviews examining alcohol harms reduction (Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020). A narrative literature review on community-based psychosocial substance-use disorder interventions in LMIC found that most literature was generated by middle and upper-middle income countries, while none originated in low-income countries (Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020). Likewise, a review of randomised controlled trials for alcohol harms reduction (Greene et al., Citation2023) found that of a total 66 studies, 63 were from middle income countries, and only 3 from low-income countries. This is significant because the harmful use of alcohol is growing in LMIC (Walls et al., Citation2020), while resources for prevention and treatment are limited (Greene et al., Citation2023).

In addition to finding few studies from LMIC, we also found that none targeted adolescents or young people. Among HIC studies, in contrast, adolescents and young adults were the focus of community-based interventions more than any other group, with 20 out of the 53 HIC studies specifically targeting them, noting the risk to adolescents and young people from binge drinking, drink driving, and living in communities with widespread alcohol misuse (Jansen et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2015; McCalman et al., Citation2013; Van Horn et al., Citation2014). This lack of focus on adolescents is mirrored in the systematic review of interventions in LMIC conducted by Greene et al. (Citation2023), where the average age of participants – where this was stated – was over 18 years, suggesting that youth and adolescents were generally not a focus of these studies.

This is concerning considering the prevalence of alcohol use by adolescents and young people in LMIC (Jain et al., Citation2023; Ramsoomar & Morojele, Citation2012), and the risks this poses to their health and wellbeing. Alcohol use by adolescents has been linked to multiple negative outcomes, including increased risk of motor-vehicle accidents, risky sexual behaviour, increased likelihood of tobacco and illegal drug use, and poorer academic results (van der Wath et al., Citation2023). The serious negative impact of alcohol on the health of adolescents is linked to the increased risk of HIV among adolescents who drink (Govender et al., Citation2020; Jonas et al., Citation2016), particularly as youth aged 15–24 face rising incidence of HIV infection (Maskew et al., Citation2019; Slogrove et al., Citation2017). In a 2010 systematic review which reported evidence-based interventions for reducing HIV transmission for youth in South Africa, reduction in alcohol use was a key recommendation. Alcohol use by adolescents and those around them is not only linked to an increased risk of HIV transmission – alcohol use by caregivers is also associated with an increased risk of violence against children and adolescents (Cluver et al., Citation2020).

There is a global call for multisectoral action on the health and wellbeing of adolescents, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa where adolescents make up 23% of the population (Efevbera et al., Citation2020). Given the sizeable proportion of adolescents in LMIC populations (Kusi-Mensah et al., Citation2022; Melesse et al., Citation2020), and the triple dividend yielded by investing in adolescent health (World Health Organisation, Citation2018a), it is advisable to include them as a focus for whole-of-community and multisectoral interventions as has been the case in HIC. An overview of systematic reviews identified school-based interventions as effective in reducing alcohol consumption, which should include elements of personalised feedback, moderation strategies, and goal setting. These could be combined with other substance use harms reduction strategies and target both young and older adolescents. Interventions involving families and communities also appear to have a persistent effect on reduced alcohol use (Das et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, there was not robust evidence for multicomponent interventions. This could be relevant to planning in LMIC, where resources for wide-ranging multicomponent interventions may be lacking.

In reviewing studies from LMIC, we summarised enablers to interventions. These included simplicity of the intervention process, cultural appropriateness, participant commitment and empowerment, collaborative community driven engagement to hone problem definition and understanding, and the engagement of community fora and action groups. The importance of cultural appropriateness was highlighted in the Rishta project in India, which featured street theatre (Pelto & Singh, Citation2010). Street theatre has a long cultural tradition in India (Pelto & Singh, Citation2010), and therefore created a high level of engagement.

Cultural appropriateness as it relates to research practice is an issue which needs to be addressed in LMIC, particularly in light of conversations around the need to decolonise research approaches (Cloete & Auriacombe, Citation2019; Keikelame & Swartz, Citation2019). In developing interventions, there needs to be respect, trust and equality between partners, and recognition of communities’ assets (Keikelame & Swartz, Citation2019). Rather than problematising communities, there should be recognition of resources, capacities, and strengths. Doing so can empower communities to better understand, and advocate for, their own priorities.

Decolonisation can also be applied to the issue of LMIC regions being a target for market expansion by global alcohol producers (Morojele et al., Citation2021). This trend can be combatted by governments in LMIC which resist pressure from the alcohol industry, as exemplified by the South African government’s alcohol ban during the Covid 19 pandemic (Reuter et al., Citation2020).

An aspect of HIC interventions which was not found in LMIC studies was the use of policy in combination with community engagement. This has been found in other work reporting on LMIC community-based psychosocial substance use interventions (Heijdra Suasnabar & Hipple Walters, Citation2020) which found little government involvement in planning and implementation, and lack of national government funding. The policy environment is a noted difference between HIC, where alcohol regulation is gaining political priority, and LMIC, where policy makers are hesitant to regulate the alcohol industry due to economic arguments and influence of the alcohol industry (Walls et al., Citation2020). However, any contribution to domestic economies in employment, output and export earnings generated by the alcohol industry is outweighed by tangible costs to the taxpayer in the form of welfare, crime, increased mortality and morbidity, and days lost to employment. The positive impacts of policies which limit access to, and consumption of, alcohol are well documented (Filby et al., Citation2023; Kilian et al., Citation2023; Maharaj et al., Citation2023; Matzopoulos et al., Citation2014), so it would be advantageous to harness policy in combination with community engagement to combat alcohol harms.

Strengths and limitations

The search strategy had no restrictions on study methodology, study population or country which enabled the inclusion of studies from as many settings as possible. The search strategy was limited in terms of the date range selected (only studies published after 2010 were included) therefore this review does not constitute an exhaustive historical account of all relevant research undertaken but does cover the period following the publication of the 2010 Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol (World Health Organisation, Citation2010). Despite efforts to include all terms in the search strategy that related to whole – of – community and intersectoral approaches, it is likely that interventions were omitted which used these methods, but described them differently. The results may therefore exclude some studies that used community engagement and multisectoral action, but the final data set should provide a broad summary of published work in this area. The review only included articles published in English and may therefore have missed some relevant research published in other languages.

Conclusion

This scoping review has provided valuable insights into possible whole-of-community interventions that can inform future work with communities to address alcohol-related harms. Overwhelmingly, research to date has been carried out in HIC. Given the alcohol industry focus on LMIC and the increase in alcohol consumption in these contexts, communities are facing growing risks from alcohol harms. This is particularly true for vulnerable groups such as adolescents, but the few projects that we identified in LMIC did not target adolescents at all. There is a gap in literature on whole-of-community and multisectoral interventions addressing alcohol harms from LMIC. Future research should include adolescents and use simple, culturally appropriate, and community-driven action, accompanied by evidence-backed elements such as school-based interventions and policy support. A learning agenda to pilot, scale and sustain whole of society approaches to address alcohol harms using standardised outcomes and measures to evaluate impact will be crucial to build the evidence base for these approaches.

Copyright

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in BMJ editions and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence.

Transparency declaration

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Ethics and dissemination

The review only makes use of published and publicly available data and thus, no ethic approval was required at this stage of the process. The results from this study will be disseminated via presentations at relevant academic research fora and conferences.

Statement of independence of researchers from funders

The funders had no role in the screening of abstracts, analysis or write up.

Patient and public involvement statement

Given that this is a scoping review, patients and the public were not involved in the design or undertaking of the study.

Data sharing statement n/a

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Any further data required are available on request from the corresponding author.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (58.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Dalglish and Rajani Ved for reviewing an initial draft of the protocol. Author contributions: ASG, TD and MT conceptualised the initial study. UW led the search strategy, development of key concepts and prepared the manuscript, supported by ASG, TD, MT, IO, MDJ and CS. NS and NH provided methodological guidance and also reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, K., Meloni, G., & Swinnen, J. (2018). Global alcohol markets: Evolving consumption patterns, regulations, and industrial organizations. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023331

- Areesantichai, C., Chapman, R. S., & Perngparn, U. (2013). Effectiveness of a tailored goal-oriented community brief intervention (TGC-BI) in reducing alcohol consumption among risky drinkers in Thailand: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 74(2), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2013.74.311

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Axelsson, R., & Axelsson, S. B. (2006). Integration and collaboration in public health — a conceptual framework. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 21(1967), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.826

- Ayano, G., Yohannis, K., Abraha, M., & Duko, B. (2019). The epidemiology of alcohol consumption in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Substance abuse: Treatment, prevention, and policy, 14(26), 1–16.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0214-5

- Bagnardi, V., Sorini, E., Disalvatore, D., Assi, V., Corrao, G., & De Stefani, R. (2011). Alcohol, less is better” project: Outcomes of an Italian community-based prevention programme on reducing per-capita alcohol consumption. Addiction, 106(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03105.x

- Beckwith, D., Ferris, L. J., Cruwys, T., Hutton, A., Hertelendy, A., & Ranse, J. (2023). Psychosocial interventions and strategies to support young people at mass gathering events: A scoping review. Public Health, 220, 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.05.006

- Cloete, F., & Auriacombe, C. (2019). Revisiting decoloniality for more effective research and evaluation. African Evaluation Journal, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/aej.v7i1.363

- Clough, A. R., Fitts, M. S., Muller, R., Ypinazar, V., & Margolis, S. (2018). A longitudinal observation study assessing changes in indicators of serious injury and violence with alcohol controls in four remote indigenous Australian communities in far north Queensland (2000-2015). BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6033-1

- Cluver, L., Shenderovich, Y., Meinck, F., Berezin, M. N., Doubt, J., Ward, C. L., Parra-Cardona, J., Lombard, C., Lachman, J. M., Wittesaele, C., Wessels, I., Gardner, F., & Steinert, J. I. (2020). Parenting, mental health and economic pathways to prevention of violence against children in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine, 262(July), 113194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113194

- Daniels, J., Struthers, H., Lane, T., Maleke, K., McIntyre, J., & Coates, T. (2018). Booze is the main factor that got me where I am today”: alcohol use and HIV risk for MSM in rural South Africa. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 30(11), 1452–1458. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1475626

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Arshad, A., Finkelstein, Y., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(2), S61–S75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021

- Degenhardt, L., Charlson, F., Ferrari, A., Santomauro, D., Erskine, H., Mantilla-Herrara, A., Whiteford, H., Leung, J., Naghavi, M., Griswold, M., Rehm, J., Hall, W., Sartorius, B., Scott, J., Vollset, S. E., Knudsen, A. K., Haro, J. M., Patton, G., Kopec, J., … Vos, T. (2018). The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(12), 987–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7

- Efevbera, Y., Haj-Ahmed, J., Lai, J., Hainsworth, G., Levy, M., Sirivansanti, N., Winnie, A., Zurak, M., & Petroni, S. (2020). Multisectoral programming for adolescent health and well-being in Sub-saharan Africa—insights from a symposium hosted by UNICEF and the Bill & Melinda gates foundation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(1), 24–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.007

- El Hayek, S., Lasebikan, V., & Noroozi, A. (2024). Editorial: Alcohol and drug use in low- and middle-income countries. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1381726. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1381726

- Felmingham, T., Backholer, K., Hoban, E., Brown, A. D., Nagorcka-Smith, P., & Allender, S. (2023). Success of community-based system dynamics in prevention interventions: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1103834

- Filby, S., Hill, R., & van Walbeek, C. (2023). The impact of reducing trading times of retailers selling alcohol for onsite consumption: Western Cape analysis. A report prepared for the DG Murray Trust. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/the_impact_of_reducing_trading_times_of_retailers.pdf.

- Flewelling, R. L., & Hanley, S. M. (2016). Assessing community coalition capacity and its association with underage drinking prevention effectiveness in the context of the SPF SIG. Prevention Science, 17(7), 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0675-y

- Govender, D., Naidoo, S., & Taylor, M. (2020). My partner was not fond of using condoms and I was not on contraception”: understanding adolescent mothers’ perspectives of sexual risk behaviour in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08474-2

- Greene, M., Kane, J., Alto, M., Giusto, A., Lovero, K., Stockton, M., McClendon, J., Nicholson, T., Wainberg, M., Johnson, R., & Tol, W. (2023). Psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use in low- and middle-income countries (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, 1–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013350

- Harker, N., Londani, M., Morojele, N., Williams, P. P., & Dh Parry, C. (2020). Characteristics and predictors of heavy episodic drinking (HED) among young people aged 16-25: The international alcohol control study (IAC), tshwane, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3537), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093537

- Heijdra Suasnabar, J. M., & Hipple Walters, B. (2020). Community-based psychosocial substance-use disorder interventions in low-and-middle-income countries: A narrative literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00405-3

- Jain, V., Parveen, S., Dixit, K., & Singh, M. (2023). Assessment of substance abuse among adolescents in India: An overview. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN, 8(6), 1703–1708. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8116732

- Jansen, S. C., Haveman-Nies, A., Bos-Oude Groeniger, I., Izeboud, C., de Rover, C., & van’t Veer, P. (2016). Effectiveness of a Dutch community-based alcohol intervention: Changes in alcohol use of adolescents after 1 and 5 years. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 159, 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.032

- Jirapramukpitak, T., Pattanaseri, K., Chua, K. C., & Takizawa, P. (2020). Home-based contingency management delivered by community health workers to improve alcohol abstinence: A randomized control trial. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 55(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agz106

- Jonas, K., Crutzen, R., Van Den Borne, B., Sewpaul, R., & Reddy, P. (2016). Teenage pregnancy rates and associations with other health risk behaviours: A three-wave cross-sectional study among South African school-going adolescents. Reproductive Health, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-016-0170-8

- Jones, S. C., Andrews, K., Francis, K. L., & Akram, M. (2018). When are they old enough to drink? Outcomes of an Australian social marketing intervention targeting alcohol initiation. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(3), 375–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12550

- Jongudomkarn, D. (2014). A volunteer alcohol consumption reduction campaign: Participatory action research among Thai women in the Isaan region. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(17), 7343–7350. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.17.7343

- Keikelame, M. J., & Swartz, L. (2019). Decolonising research methodologies: Lessons from a qualitative research project, Cape Town, South Africa. Global Health Action, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1561175

- Kilian, C., Lemp, J. M., Llamosas-Falcón, L., Carr, T., Ye, Y., Kerr, W. C., Mulia, N., Puka, K., Lasserre, A. M., Bright, S., Rehm, J., & Probst, C. (2023). Reducing alcohol use through alcohol control policies in the general population and population subgroups: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 59, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101996

- Kusi-Mensah, K., Tamambang, R., Bella-Awusah, T., Ogunmola, S., Afolayan, A., Toska, E., Hertzog, L., Rudgard, W., Evans, R., & Omigbodun, O. (2022). Accelerating progress towards the sustainable development goals for adolescents in Ghana: A cross-sectional study. Psychology, Health, and Medicine, 27(9), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2108086

- Larson, E., George, A., Morgan, R., & Poteat, T. (2016). 10 best resources on … intersectionality with an emphasis on low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 31(8), 964–969. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw020

- Leddy, A. M., Hahn, J. A., Getahun, M., Emenyonu, N. I., Woolf-King, S. E., Sanyu, N., Katusiime, A., Fatch, R., Chander, G., Hutton, H. E., Muyindike, W. R., & Camlin, C. S. (2021). Cultural adaptation of an intervention to reduce hazardous alcohol use Among people living with HIV in southwestern Uganda. AIDS and Behavior, 25(S3), 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03186-z

- Leung, J., Chiu, V., Connor, J. P., Peacock, A., Kelly, A. B., Hall, W., & Chan, G. C. K. (2019). Alcohol consumption and consequences in adolescents in 68 low and middle-income countries – a multi-country comparison of risks by sex. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 205, 107520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.022

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lewis, A. J., Holmes, N. M., Watkins, B., & Mathers, D. (2015). Children impacted by parental substance abuse: An evaluation of the supporting kids and their environment program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2398–2406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0043-0

- Logie, C. H., Okumu, M., Admassu, Z., MacKenzie, F., Tailor, L., Kortenaar, J. L., Perez-Brumer, A., Ahmed, R., Batte, S., Hakiza, R., Kibuuka Musoke, D., Katisi, B., Nakitende, A., Juster, R. P., Marin, M. F., & Kyambadde, P. (2024). Exploring ecosocial contexts of alcohol use and misuse during the COVID-19 pandemic among urban refugee youth in Kampala, Uganda: Multi-method findings. Journal of Migration and Health, 9, 100215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2024.100215

- MacQueen, K., McLellan, E., Metzger, D., Kegeles, S., Strauss, R., Scotti, R., Blanchard, L., & Trotter, R. (2001). What Is community? An evidence-based definition for participatory public health. American Journal of Public Health, 91(1), 1929–1938. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929

- Maharaj, T., Angus, C., Fitzgerald, N., Allen, K., Stewart, S., Machale, S., & Ryan, J. D. (2023). Impact of minimum unit pricing on alcohol-related hospital outcomes: Systematic review. BMJ Open, 13(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065220

- Maskew, M., Bor, J., Macleod, W., Carmona, S., Sherman, G. G., & Fox, M. P. (2019). The adolescent HIV treatment bulge in South Africa’s national HIV program: A retrospective cohort. The Lancet HIV, 6(11), e760–e768. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30234-6

- Matanje Mwagomba, B. L., Nkhata, M. J., Baldacchino, A., Wisdom, J., & Ngwira, B. (2018). Alcohol policies in Malawi: Inclusion of WHO “best buy” interventions and use of multi-sectoral action. BMC Public Health, 18(Suppl 1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5833-7

- Matzopoulos, R. G., Truen, S., Bowman, B., & Corrigall, J. (2014). The cost of harmful alcohol use in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 104(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.7644

- McCalman, J., Tsey, K., Bainbridge, R., Shakeshaft, A., Singleton, M., & Doran, C. (2013). Tailoring a response to youth binge drinking in an aboriginal Australian community: A grounded theory study. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-726

- McKay, M., Agus, A., Cole, J., Doherty, P., Foxcroft, D., Harvey, S., Murphy, L., Percy, A., & Sumnall, H. (2018). Steps towards alcohol misuse prevention programme (STAMPP): A school-based and community-based cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 8(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019722

- Melesse, D. Y., Mutua, M. K., Choudhury, A., Wado, Y. D., Faye, C. M., Neal, S., & Boerma, T. (2020). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-saharan Africa: Who is left behind? BMJ Global Health, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002231

- Midford, R., & Shakeshaft, A. (2016). Alcohol-Related harms: From past experiences to future possibilities. In T. Kolind, B. Thom, & G. Hunt (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of drug and alcohol studies (pp. 213–236). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473921986.n13

- Morojele, N. K., Dumbili, E. W., Obot, I. S., & Parry, C. D. H. (2021). Alcohol consumption, harms, and policy developments in sub-saharan Africa: The case for stronger national and regional responses. Drug and Alcohol Review, 40(3), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13247

- Novotna, G., Nielsen, E., & Berenyi, R. (2023). Harm reduction strategies for severe alcohol Use disorder in the context of homelessness: A rapid review. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/11782218231185214

- Okeyo, I., Walmisley, U., de Jong, M., Späth, C., Doherty, T., Siegfried, N., Harker, N., Tomlinson, M., & George, A. S. (2022). Whole of community interventions that address alcohol related harms: Protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open, 12, e059332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059332

- Oladeinde, O., Mabetha, D., Twine, R., Hove, J., Van Der Merwe, M., Byass, P., Witter, S., Kahn, K., & D’Ambruoso, L. (2020). Building cooperative learning to address alcohol and other drug abuse in Mpumalanga, South Africa: A participatory action research process. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1726722

- Park, S. H., & Kim, D. J. (2020). Global and regional impacts of alcohol use on public health: Emphasis on alcohol policies. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology, 26(4), 652–661. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2020.0160

- Pelto, P. J., & Singh, R. (2010). Community street theatre as a tool for interventions on alcohol use and other behaviors related to HIV risks. AIDS and Behavior, 14(4 SUPPL.), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9726-8

- Public Health Agency of Canada, & Equinet. (2007). Crossing sectors - experiences in intersectoral action, public policy, and health. ISBN: 978-0-662-46187-6 https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.689882/publication.html?wbdisable = true

- Quigg, Z., Hughes, K., Butler, N., Ford, K., Canning, I., & Bellis, M. A. (2018). Drink less enjoy more: Effects of a multi-component intervention on improving adherence to, and knowledge of, alcohol legislation in a UK nightlife setting. Addiction, 113(8), 1420–1429. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14223

- Ramsoomar, L., & Morojele, N. K. (2012). Trends in alcohol prevalence, age of initiation and association with alcohol-related harm among South African youth: Implications for policy. South African Medical Journal, 102(7), 609–612. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.5766

- Reuter, H., Jenkins, L. S., De Jong, M., Reid, S., & Vonk, M. (2020). Prohibiting alcohol sales during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has positive effects on health services in South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 12(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2528

- Schelleman-Offermans, K., Knibbe, R. A., & Kuntsche, E. (2014). Preventing adolescent alcohol use: Effects of a two-year quasi-experimental community intervention intensifying formal and informal control. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54(3), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.001

- Schensul, S. L., Saggurti, N., Burleson, J. A., & Singh, R. (2010). Community-level HIV/STI interventions and their impact on alcohol use in urban poor populations in India. AIDS and Behavior, 14(4 SUPPL.), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9724-x

- Shakeshaft, A., Doran, C., Petrie, D., Breen, C., Havard, A., Abudeen, A., Harwood, E., Clifford, A., D’Este, C., Gilmour, S., & Sanson-Fisher, R. (2014). The effectiveness of community action in reducing risky alcohol consumption and harm: A cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 11(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001617

- Sileo, K. M., Miller, A. P., Huynh, T. A., & Kiene, S. M. (2020). A systematic review of interventions for reducing heavy episodic drinking in sub-saharan African settings. PLoS One, 15(12), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242678

- Siriwardhana, P., Dawson, A. H., & Abeyasinge, R. (2013). Acceptability and effect of a community-based alcohol education program in rural Sri Lanka. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(2), 250–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/ags116

- Slogrove, A. L., Mahy, M., Armstrong, A., & Davies, M. (2017). Living and dying to be counted: What we know about the epidemiology of the global adolescent HIV epidemic. Journal of the International Aids Society, 20(Suppl 3), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.4.21520

- Stockings, E., Bartlem, K., Hall, A., Hodder, R., Gilligan, C., Wiggers, J., Sherker, S., & Wolfenden, L. (2018). Whole-of-community interventions to reduce population-level harms arising from alcohol and other drug use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 113(11), 1984–2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14277

- Stockings, E., Shakeshaft, A., & Farrell, M. (2018). Community approaches for reducing alcohol-related harms: An overview of intervention strategies, efficacy, and considerations for future research. Current Addiction Reports, 5(2), 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0210-2

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2015). Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual: 2015. The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294736492_Methodology_for_JBI_Scoping_Reviews#fullTextFileContent.

- Tricco, A. C., Lille, E., Wasifa, Z., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horseley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M., Garrity, C., … Straus, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- van der Wath, A. E., Moagi, M. M., & van der Wath, E. (2023). Risk factors for harm caused by alcohol use among students at higher education institutions: An integrative literature review. Journal of Substance Use, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2023.2217249

- Van Horn, M. L., Fagan, A. A., Hawkins, J. D., & Oesterle, S. (2014). Effects of the communities that care system on cross-sectional profiles of adolescent substance use and delinquency. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(2), 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.004

- Walls, H., Cook, S., Matzopoulos, R., & London, L. (2020). Advancing alcohol research in low-income and middle-income countries: A global alcohol environment framework. BMJ Global Health, 5(4), e001958. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001958

- Witvorapong, N., & Watanapongvanich, S. (2020). Using pre-commitment to reduce alcohol consumption: Lessons from a quasi-experiment in Thailand. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 70(May 2019), 100723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2019.06.008

- Wolfenden, L., Nathan, N. K., Sutherland, R., Yoong, S. L., Hodder, R. K., Wyse, R. J., Delaney, T., Grady, A., Fielding, A., Tzelepis, F., Clinton-Mcharg, T., Parmenter, B., Butler, P., Wiggers, J., Bauman, A., Milat, A., Booth, D., & Williams, C. M. (2017). Strategies for enhancing the implementation of school-based policies or practices targeting risk factors for chronic disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, 1–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011677.pub2

- World Health Organisation. (2010). Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599931 ISBN: 9789241599931.

- World Health Organisation. (2018a). Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!) guidance to support country implementation. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512343 ISBN: 9789241512343.

- World Health Organisation. (2018b). Global status report on alcohol and health, 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639 ISBN: 978-92-4-156563-9.

- World Health Organisation. (2019). Alcohol policy impact case study: The effects of alcohol control measures on mortality and life expectancy in the Russian Federation. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328167/9789289054379-eng.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y ISBN: 978 92 890 5437 9.