ABSTRACT

Transgender women (TGW) and men who have sex with other men (MSM) often encounter disparities in accessing HIV testing, leading to delayed diagnoses and worse prognoses. We analysed barriers and facilitators for accessing HIV rapid testing by TGW and MSM in Brazil, 2004-2023. Citations were included whether the study population consisted of individuals aged ≥18y old, and studies addressed HIV testing and have been conducted in Brazil. The study protocol was based on Joanna Briggs’ recommendations for scoping reviews. We included 11 studies on TGW and 17 on MSM. The belief that one is not at risk of contracting HIV infection, fear expressed in different ways (e.g. lack of confidentiality) and younger age were the main barriers. Feeling at risk for HIV infection, curiosity, and favourable characteristics of the setting where the testing takes place were cited as the main facilitators. Barriers and facilitators specifically for HIV self-testing included, respectively, concerns about conducting the test alone vs. autonomy/flexibility. Brazil is unlikely to achieve the UN’ 95-95-95 goal without minimising testing disparities. Combating prejudice against TGW and MSM in testing settings, along with educational campaigns and transparent protocols to ensure confidentiality, can help increase HIV testing among these populations.

Introduction

The 74th World Health Assembly reaffirmed the goal of eradicating the HIV/AIDS pandemic by 2030 (UNAIDS, Citation2014). As a result, signatory countries should translate their policies and strategies into concrete actions that can help them reach the target of 95% of HIV-positive individuals diagnosed, 95% of those diagnosed on sustained antiretroviral therapy, and 95% of those on antiretroviral therapy with suppressed viral load by 2025 (Frescura et al., Citation2022). As made clear in the UNAIDS statement, access to HIV testing and early diagnosis is a key step in the cascade of care. However, there are disparities in access to HIV testing, particularly among the most HIV-vulnerable populations, also called ‘key populations’ (Creasy et al., Citation2019; Pitasi et al., Citation2020).

Due to prejudice and discrimination experienced by key populations when interacting with health services and providers, they often face obstacles to being tested for HIV (Koutentakis et al., Citation2019; Price et al., Citation2019). Consequently, the detection rates of HIV infection in transgender women (TGW) and gay and other men who have sex with men (for the sake of conciseness ─ MSM) tend to be lower than among less stigmatised population groups (Sandfort et al., Citation2019). Such vulnerable populations frequently become aware of their diagnosis in the advanced stages of the infection, which results in much worse prognosis.

On the other hand, several studies have identified facilitators for HIV rapid testing, which may serve as valuable tools for policymakers in efficiently extending testing initiatives among key populations and improving early diagnosis rates. In Brazil, the HIV epidemic is concentrated in key populations (Pinto et al., Citation2021). Despite numerous initiatives undertaken by the federal government in collaboration with civil society organisations to expand access to HIV testing, these populations continue to encounter challenges in accessing their entitlement to HIV counselling and testing services (Cruz et al., Citation2021). Understanding the barriers and facilitators for HIV testing is crucial for assisting policy makers in allocating resources for strategies to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment. We aimed to systematize and analyse the scientific knowledge on barriers and facilitators for accessing HIV rapid testing by transgender women and men who have sex with men in Brazil from 2004 to 2023.

Methods

The study protocol was based on Joanna Briggs’ recommendations for scoping reviews and has been published in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/ewj53/) (Tricco et al., Citation2018). We followed the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (S1 PRISMA-ScR Statement) (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The review was guided by the research question as follows: What are/were the barriers and facilitators for HIV rapid testing among TGW and gay and other MSM in Brazil from 2004 to 2023? We used the framework ‘Condition’ (including: ‘Condition’, ‘Condition & diagnosis/screening’, ‘Factors associated with access/barriers to diagnosis/screening’), ‘Context and Population’ (Acronym: ‘CoCoPop’) to identify the standardised indexing terms/keywords that represent those three main concepts in order to answer the research question (Munn et al., Citation2018). The search terms were chosen by identifying heading index terms (i.e. Medical Subject Headings [MeSH terms] or equivalent) and their synonyms according to the CoCoPop acronym/main concepts for each database (Box S1).

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE via PubMed, Web of Science (main collection), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE), SCOPUS, Scientific Electronic Library (SCIELO), Virtual Health Library (VHL) Regional Domain, and Academic Search Premier/EBSCO. We implemented a grey literature search plan to incorporate different search strategies using the following strategies, resources, and tools (Godin et al., Citation2015): (i) Google Scholar (ii); Brazilian and international grey literature databases relevant to the subject under review; (iii) selected websites of relevant national health organisations and agencies related to the subject under review; and (iv) Brazilian and international conference websites related to the subject under review (Boxes S2-S5). Brazilians’ researchers, experts in the field were also contacted. The final search took place on 31 April 2023.

We performed independent searches for each population. Retrieved documents comprised papers published between January 2004 and April 2023 in English and Portuguese. The search strategies were implemented independently by two researchers (LT and GR [the latter is a senior public health librarian expert]). The final search results were keyed into Rayyan® (Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, Citation2016). Duplicates were removed. Discrepancies made evident by aligning references side-by-side were resolved by consensus, with discussion between the two independent researchers and input from a senior expert (FB).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in this review, peer-reviewed manuscripts/grey literature documents had to meet the following criteria: (i) study population consisting of TGW or MSM ≥18y old (i.e. legal age in Brazil); (ii) experimental, observational, mixed-methods, or qualitative study design; (iii) study results including aspects of barriers and/or facilitators of HIV testing, stratified by TGW and MSM; (iv) study conducted in Brazil; and (v) published in Portuguese or English.

Manuscripts and grey literature were excluded if they focused on heterosexual, lesbian, queer, bisexual men and women, the general population, pregnant or TGW or MSM <18y old (i.e. unable to provide full consent), as well as animal studies (even in case findings might be inferred for human beings); reviews; editorials; case reports, commentaries, and preprints. Studies that did not present results on barriers and/or facilitators of HIV testing or that did not stratify the results by TGW or MSM were excluded.

Selection of publications to be included

Two independent reviewers (LT and PP) screened titles, abstracts, and results against the inclusion and exclusion criteria as displayed by Rayyan® (Mourad et al., 2016). Next, two independent reviewers (LT and PP) examined all eligible sources of evidence for inclusion. Uncertainties on eligibility were resolved by discussion, consensus, and deliberation by the two former researchers with the help of a senior author (FIB).

Data charting

One reviewer (LT) extracted data from each included article using a standardised data extraction spreadsheet. For accuracy and completeness, the other reviewer (PP) double-checked the extracted data. Discussions were conducted whenever differences of opinion emerged, aiming to reach consensus. General sociodemographic characteristics were identified for the study populations, barriers and facilitators for HIV testing, and factors associated with access and willingness to undergo HIV testing. After several rounds of debate, no major discrepancy remained.

Data analysis

A narrative synthesis approach was used to summarise and describe the findings (Tricco et al., Citation2018). We categorised the studies based on the summary of the literature mapped, the sociodemographic general characteristics of the study's participants, barriers and facilitators of HIV rapid testing (quantitative and qualitative evidence) and specific barriers and facilitators of HIV self-testing.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Results

Overview of the mapped literature

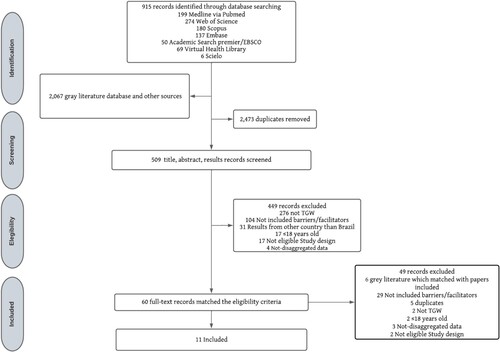

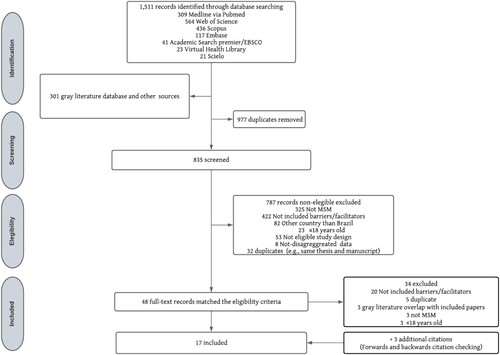

Following the removal of duplicates, 11 studies of TGW and 17 on MSM were included in the review ( and ). Among the TGW citations, one citation (Bastos, Coutinho, & Malta, Citation2018) was a research project which described results stratified by 12 Brazilian cities. These was multicity cross-sectional study that recruited TGW through respondent-driven sampling (RDS). Since each city had its own RDS referring-chain sample, we considered the results of each city described in the reports as independent sources of evidence. Among the TGW studies had both epidemiological and qualitative designs, whereas the majority of MSM studies used epidemiological designs (Tables S1-S4).

Figure 1. PRISMA Scoping Review flowchart of identified, screened and included citations on Barriers and facilitators to HIV rapid testing among Transgender women in Brazil, from January 2004 to April 2023.

Figure 2. PRISMA Scoping Review flowchart of identified, screened, and included citations on barriers and facilitators for HIV rapid testing among men who have sex with men in Brazil from January 2004 to April 2023.

Most of the epidemiological studies on TWG used cross-sectional designs using RDS. In epidemiological studies on MSM, cross-sectional designs also predominated; however, they displayed a diverse array of recruitment methods, such as RDS and enrolling potential interviewees from gay socialising venues, dating apps, and social media. In studies on TWG, the sample sizes varied from 77 participants to 864 participants, whereas among studies on MSM such figures varied from 51 to 11,118 participants (Tables S1–S4). Thematic content analysis was the predominant method used for data analysis in qualitative studies on both populations (Tables S2 and S4).

Several studies were performed in Brazil’s five major geographic regions, but most of the studies on TWG were concentrated in the Southeast, whereas the studies on MSM were predominantly multicity ones (Tables S1–S4). Another important difference was that studies targeting TWG tended to be local or regional. Studies targeting MSM were far more diverse and several reported findings from large, pooled samples. Fifteen studies (Elorreaga et al., Citation2022; Bay et al., Citation2019; Brito et al., Citation2015; Cota & Cruz, Citation2021; De Boni et al., Citation2019; Gomes, Citation2014; Gonçalves et al., Citation2016; Lima, Citation2019; Lippman et al., Citation2014; Magno et al., Citation2020; Melo, Citation2012; Sousa et al., Citation2019; Torres et al., Citation2018; Vasconcelos et al., Citation2022; Volk et al., Citation2016), identified factors related with the barriers, and six studies (Gonçalves et al., Citation2016; Bay et al., Citation2019; Almeida et al., Citation2021; Melo, Citation2012; Redoschi, Citation2016; Sousa et al., Citation2019) addressed facilitators of HIV testing among MSM. Meanwhile, ten studies (Costa et al., Citation2018; Dourado et al., Citation2016; Leite et al., Citation2021; Monteiro & Brigeiro, Citation2019; Pinheiro Júnior et al., Citation2016; Porto, Citation2018; Sevelius et al., Citation2019; Souza & Pereira, Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2019, Citation2021) identified barriers related with HIV testing, and seventeen studies (Bastos et al., Citation2018; Costa et al., Citation2018; Leite et al., Citation2021; Monteiro & Brigeiro, Citation2019; Pinheiro Júnior et al., Citation2016; Sevelius et al., Citation2019) addressed factors associated with facilitators of HIV testing among TGW. Six studies on MSM addressed barriers and facilitators for HIV self-testing (Elorreaga et al., Citation2022; Magno et al., Citation2020; Lima, Citation2019; Lippman et al., Citation2014; Torres et al., Citation2018; Volk et al., Citation2016). This aspect was absent from studies on TGW population (Tables S1–S4).

General characteristics of the study populations

In most studies on TGW and MSM, the study populations consisted predominantly of young adults 18–35 years of age (Tables S1–S4). Across both populations, most study participants self-reported their race/colour/ethnicity as non-white (Tables S1–S4). In the majority of TGW studies, participants reported low schooling, with a minority reporting secondary school diplomas. Meanwhile, in the majority of MSM studies, participants had secondary schooling or greater, including a sizeable minority with university degrees (Tables S1–S4).

Barriers to HIV rapid testing

‘The belief that one is not at risk of contracting HIV infection’ (verbatim [mentioned by 5 manuscripts]) by abstaining from sex or engaging in sexual relations self-defined as ‘safe’ was the primary barrier to HIV testing, consistently reported by both TGW and MSM (Box 1). In the pooled national analysis by Sousa et al. (Citation2019), engaging in sex without penetration (adjOR:2.30; 95%CI:1.17–4.50) and ejaculating outside of the anal canal (adjOR:1.79; 95%CI:1.04–3.05) were factors associated with not taking the HIV test (Table S3).

Box 1. Factors described as barriers to HIV testing among transgender women and men who have sex with men. Brazil, 2004-2023

The second most cited barrier to HIV testing for both TGW and MSM was fear. Fear was expressed in different ways, including apprehension about receiving a positive result (Costa et al., Citation2018; Volk et al., Citation2016), concerns about facing discrimination after receiving a positive test result (Bay et al., Citation2019; Gonçalves et al., Citation2016; Volk et al., Citation2016) and worries about potential mistreatment and/or stigmatisation at healthcare facilities (Box 1) (Cota & Cruz, Citation2021; Costa et al., Citation2018). In a 2010 cross-sectional study of 391 MSM participants in Fortaleza, Northeast Brazil, 20.3% (95%CI:9.6–36.7) reported fearing discrimination if they had a positive result (Gonçalves et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, 17.5% of 337 TGW in a 2010 cross-sectional study in Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo reported to be afraid of getting a positive result (Costa et al., Citation2018).

The third barrier refers to a sociodemographic characteristic. In both populations, younger age was identified as associated with less frequent HIV testing. Pinheiro Júnior et al. (Citation2016), found that TGW under 18 years of age were more likely to avert being tested (AdjOR:4.22; 95%CI:2.41–7.36) in Fortaleza, Ceará, in 2008. Similarly, Brito et al. (Citation2015), reported that MSM ≤20 years of age were more likely not to be tested for HIV before the study under analysis (AdjOR: 5.29; 95% CI:3.21–8.71) (Box 1).

Factors related to the willingness to undergo HIV testing and the facilitators to do so

Citations mentioning facilitators are far fewer than those highlighting barriers (Box 2). Most papers simply fail to mention facilitators. The most widely cited factors refer to feeling himself/herself at risk (such ‘feeling’ may or may not be similar to experts’ points of view but perceived as such by interviewees nevertheless), sometimes combined with the individual’s curiosity about their serostatus (Box 2).

Box 2. Potential motivating/facilitating factors for HIV testing in transgender women and men who have sex with other in Brazil, 2004–2023

Curiosity, cited by 6 different papers was the second most cited factor related with the willingness to undergo HIV testing (Box 2). In the RDS study conducted in Brasília, in 2016, it was found that 34.98% (95%CI:22.65–47.31) of the 201 TGW interviewed expressed a sense of feeling at risk for HIV infection as a primary motivation for undergoing testing (Table S1) (Bastos et al., Citation2018). Similarly, in a cross-sectional study conducted in São Paulo in 2012, 50.6% (95%CI:42.0–59.1) of the surveyed MSM reported feeling at risk of contracting HIV as a key factor influencing their decision to get tested (Redoschi, Citation2016). The third most common factors mentioned by interviewees involve the set and setting where the testing takes place and how the entire procedure is conducted. In Natal, 2012, a study by Bay et al. (Citation2019), found that knowing where to obtain a free-of-charge HIV test was significantly associated with MSM undergoing HIV testing, with a prevalence ratio of 1.69 (95%CI:1.05–2.71). In a study conducted by Gonçalves et al. (Citation2016), in Fortaleza, various factors were identified as motivating MSM to seek HIV testing. These factors included participating in the ‘Fique Sabendo’ booster HIV testing campaign (34%; 95%CI:10.7–39.1), having easy access to health services (27.1%; 95%CI:8.3–34.4), being aware of the availability of HIV/AIDS treatment (23.6%; 95%CI:6.4–35.3), and receiving encouragement from a healthcare professional to get tested (23.2%; 95%CI:8.9–37.2). In the case of TGW studies, the predominant reasons for seeking HIV testing were a medical request or receiving advice from someone else to undergo testing (Table S1).

Self-testing

We identified six studies that investigated barriers and facilitators related to self-testing for HIV among MSM, and none specifically focused on TGW (Elorreaga et al., Citation2022; Lima, Citation2019; Lippman et al., Citation2014; Magno et al., Citation2020; Torres et al., Citation2018; Volk et al., Citation2016). HIV self-testing was basically used by highly educated affluent people (except for targeted distribution of such tests provided free of cost at the point of delivery). Many of the barriers and facilitators related to HIV self-testing overlap those of regular testing. These common factors include the belief of not being at risk of HIV infection, the fear of receiving a positive result and potential discrimination consequently, as well as curiosity as a facilitator (Box 3).

Box 3. Factors described as barriers and facilitators specifically for HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men Brazil, 2004–2023

However, some specificities need to be noted due to the intrinsic characteristics of self-testing. Barriers to HIV self-testing encompass concerns related to the apprehension of conducting the test alone, which involves the potential of receiving positive results without immediate access to counselling. A study conducted by Elorreaga et al. (Citation2022), involving 11,118 MSM in Brazil in 2018, revealed that reduced trust in self-testing compared to testing at a health centre (adjusted prevalence ratio [adjPR]:0.90; 95%CI:0.88–0.93), fear of conducting the test alone (aPR:0.91; 95%CI:0.88–0.93), and the belief in the essentiality of pre-test counselling with a health professional (aPR: 0.95; 95%CI:0.91−0.98) were negatively associated with the willingness to self-test for HIV.

Conversely, facilitators of HIV self-testing encompass attributes such as flexibility, privacy, autonomy, confidentiality, and independence from tangible or potential constraints, as well as the avoidance of any associated embarrassment linked to attending crowded testing facilities with extended waiting times. Individuals who opt for self-testing often have concerns about encountering unsupportive/judgmental healthcare professionals, or the possibility of running into friends and acquaintances at testing services, with whom they may prefer not to share personal information. In a web-based survey conducted by Lippman et al. (Citation2014) in 2011, involving 629 MSM, it was observed that a substantial fraction (75%) of respondents agreed that self-testing offers a greater degree of privacy compared to clinic-based tests. Furthermore, 62% of participants reported that the ability to test at home could assist them in making informed decisions regarding engaging in unprotected sexual encounters with regular partners, while 54% indicated that it could have a similar impact when considering new partners.

Qualitative evidence on barriers and facilitators to HIV testing

There were fewer qualitative studies (Tables S2, S4) than quantitative ones. Most of them refer to TGW. Excerpts from qualitative studies function as informative vignettes about empirical aspects of day-to-day experiences of interviewees in their encounters with disrespectful healthcare professionals. The stigmatisation of MSM and especially TWG by healthcare workers is evident in the quantitative studies, but they are especially vivid in the narratives of interviewees. An unfortunate combination of abuse, harassment, and disrespect emerges from some reports. Beyond the violation of protocols designed to be based on best practices, widespread human rights violations were described in several situations and contexts (e.g. health units) where such unacceptable attitudes should have been totally absent.

The narratives surrounding barriers to HIV testing among TGW and MSM highlight key challenges, including bureaucratic hurdles and inadequate service provision. These obstacles interact with restrictive norms, such as the requirement for identification documents to retrieve test results, disrespect towards the use of preferred social names, limited operating hours at healthcare facilities for HIV testing, experiences of stigma discrimination within healthcare settings, difficulty in paying for transportation to go to the health centre, especially for those who live far away, and a rude pre-and post-test counselling (Cota & Cruz, Citation2021; Sevelius et al., Citation2019). Unfortunately, training and capacitation of health professionals to properly address stigma and discrimination is far from comprehensive and it´s not available in most health centres. Few papers describe a concerted effort to provide comprehensive training to their health professionals.

Another key complaint referred to the ‘tunnel vision’ of some healthcare professionals who focused only on HIV, without any commitment to one of the pillars of the SUS (or of any fair health service or system), namely comprehensiveness. Interviewees, especially TWG, reported that they would like to be viewed as integral persons instead of people affected only by HIV, as any other patient.

The straightforward relationship between TGW identity and HIV by both healthcare providers and fellow clients exposes TGW to pervasive stigma and discrimination in health settings. Additionally, two qualitative studies emphasise the fear of breached confidentiality regarding HIV test results as a barrier (Dourado et al., Citation2016; Porto, Citation2018). This mistrust stems from concerns among TGW about their test results being disclosed within their social networks, not only in health settings but also when HIV testing is offered in shared socialisation spots or living environments (Dourado et al., Citation2016; Porto, Citation2018). Furthermore, Monteiro and Brigeiro (Citation2019), highlight that for some TGW, HIV testing takes a backseat to other gender transition-related procedures, such as plastic surgery, sex reassignment, or hormone therapy. Lastly, Sevelius et al. (Citation2019), emphasise that many TGW are fatigued by discussions centred around HIV and related topics, expressing a preference for topics that empower the TGW community. Respecting HIV testing facilitators, particularly within the TGW population, there are auspicious narratives. TGW have underscored the pivotal contributions of peer educators in mitigating their apprehensions and biases, thereby aiding them in navigating healthcare environments with fewer health and human rights violations.

Furthermore, TGW narratives highlighted the optimal integration between certain steps in the transsexualization process, such as the use of hormones or surgical procedures, and the provision of HIV testing, management, and care by the same referral services. In some services, such procedures may occur in the context of a single-visit medical appointment.

Discussion

This is the first scoping review conducted in Brazil on barriers and facilitators to HIV testing in two key populations, MSM and TGW. Brazil has a long tradition of successful AIDS policies, which however have been challenged by the emergence of a powerful coalition of homophobic and transphobic governmental and conservative civil society sectors, a process that has still not been fully reversed. Such policies require permanent assessment to address caveats and challenges and contribute to their strengthening and updating. The study provides a comprehensive synthesis of peer-reviewed and grey literature, spanning two decades and covering a wide range of publications.

Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing frequently overlap in our review. Several factors listed as barriers are the same that have been identified as key facilitators in other directions and contexts. For instance, risk self-perception was one of the most frequently cited factors, either as a barrier (when individuals feel they are not at risk) or as a facilitator to engage people in HIV testing (when individuals see themselves at risk) (Golub & Gamarel, Citation2013; Khan et al., Citation2022). According to a cross-sectional study of 305 MSM in New York City in 2012/13, individuals with increased perception of their risk of HIV infection showed 33% higher odds of having undergone HIV testing in the previous 6 months (Golub & Gamarel, Citation2013). Meanwhile, in a qualitative study of MSM and Hijra in Dhaka, Bangladesh, some participants attributed their consistent condom use during transactional sex to a belief that they did not require HIV testing, even though they engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse with their romantic partners (Khan et al., Citation2022). The dual role of self-perceived HIV risk highlights the intricate nature of factors shaping HIV testing behaviour, sometimes involving misconceptions regarding susceptibility to HIV infection. Inversely, a sense of vulnerability can trigger proactive health measures, as discussed by the Health Belief Model, according to which the perceived exposure to a health hazard plays a crucial role in initiatives related to seeking healthcare (Alizade et al., Citation2021).

Fear in its various forms emerged consistently as a barrier in the studies we reviewed. According to a multicity study of 753 urban youths consisting of MSM and TGW in the United States, 2012–2023, the fear of experiencing rejection in case of receiving a positive HIV test result, also known as anticipated HIV stigma, was associated with a 4% increase in the odds of deferred HIV testing (Gamarel et al., Citation2018). Fear of suffering discrimination and previous experience with discrimination in healthcare settings based on sexual orientation and gender identity have been consistently highlighted as obstacles to seeking HIV testing, in line with the qualitative evidence reviewed by us and other authors (Hamilton et al., Citation2020; Magno et al., Citation2023; Wilson et al., Citation2019).

The studies reviewed consistently described a negative association between young age (≈ under 25 years) and HIV testing among both MSM and TGW. In San Salvador, El Salvador, in a RDS study in 2011/2, individuals ≥25y old showed higher likelihood of previous HIV testing (Andrinopoulos et al., Citation2015). The findings were similar for MSM and TGW and suggest the possibility of a birth cohort effect. The new generation of MSM and TGW faces a transformed landscape characterised by potent treatments and higher survival rates of people living with AIDS. This shift may have led to changes in behaviours among the younger generation, favouring optimism and reduced concerns.

Optimism has been associated with decreased reliance on preventive measures such as condom use and regular HIV testing, according to several studies (Peterson et al., Citation2012). Evidence from two studies in low- and middle-income countries indicates that young MSM are more likely to engage in unprotected receptive anal intercourse and transactional sex while perceiving a low level of HIV risk and presenting low rates of HIV testing (Nowak et al., Citation2019; Torres et al., Citation2019).

Concerns regarding the confidentiality of HIV test results may act either as barriers or facilitators, depending on (mis)trust and strict/lack of adherence to norms protecting confidentiality (Bien et al., Citation2015; Cooke et al., Citation2017; Magno et al., Citation2023). In a qualitative study conducted in China, the absence of confidentiality protocols, such as calling patients by their names during testing procedures and the mandatory requirement to disclose sexual orientation were pivotal factors influencing decisions by MSM to forgo HIV testing (Bien et al., Citation2015). In that study, MSM expressed a preference for using pseudonyms or providing phone numbers during the testing registration process (Hawk et al., Citation2020). Meanwhile, in a systematic review by Magno et al. (Citation2023), ensuring the confidentiality of HIV test results was found to be a key facilitator of testing among MSM and TGW.

In accordance with other studies (Bien et al., Citation2015; Hawk et al., Citation2020; Iribarren et al., Citation2020; Magno et al., Citation2023), we identified factors such as flexibility, privacy, autonomy, and the avoidance of some clinical and testing settings as facilitators for HIV self-testing. MSM are afraid to face stigma and discrimination when visiting less than optimal testing facilities, where confidentiality and anonymity are not strictly guaranteed (Freeman et al., Citation2018). In a cross-sectional study involving key populations in New York City in 2017/8, participants’ preferences were primarily driven by the convenience of avoiding some testing sites (84%) and the ability to be tested at their preferred times (52%) (Hubbard et al., Citation2020).

One concern reported in several studies that we reviewed is a lack of awareness among MSM regarding the HIV testing window period. The use of HIV test results to inform decisions about engaging in unprotected sex may inadvertently lead to the misuse of HIV testing as a form of serological screening, where individuals mistakenly assume they are free from HIV infection if they tested negative, thus engaging in unprotected sex, and increasing their vulnerability.

Scientific knowledge concerning barriers and facilitators related to HIV testing among MSM and TGW in Brazil is still far from comprehensive. There are limitations to be considered here: First, the studies exhibit considerable heterogeneity. Most studies on MSM were large, multicity studies, focusing on barriers and facilitators of both regular and self-HIV testing. Meanwhile, such large multicity studies are the exception in TGW. Most interviewees (both MSM and TGW) usually lacked essential information on aspects highlighted by the international literature on testing, such as knowledge about where to get HIV testing free-of-charge and limited information on where they can be tested without further difficulties such as waiting lists, long distances, and high transportation costs. Several web-based surveys have focused on MSM, while remaining rare or even absent in TGW. This disparity can be attributed partly to the larger MSM population compared to TGW, rendering recruitment for web-based surveys easier for the former group. MSM also have a decades-long history of activism and proactive policies. Such a proactive role is still recent and fragmentary among TSW in most settings.

There may also be disparities in internet access between MSM and TGW in Brazil. MSM are more likely to have access to the internet and technology due to their better average socioeconomic status after decades of social activism and compensatory policies. Engagement of TGW in Brazil and worldwide in advocacy coalitions is more recent and less comprehensive, compared to individuals self-identified as gay men and women. Research on HIV/AIDS in Brazil has historically focused more on MSM than on TGW.

Another major limitation is secondary to the fact that the great majority of studies for both populations in Brazil have been conducted in urban areas, especially in major cities and state capitals. There is a persistent gap in our understanding of the lives and contexts where gay and TGW live in rural areas and small cities. Furthermore, MSM studies aggregated results of pooled samples or multiple cities, while TGW studies were predominantly from Southeast Brazil, a largely industrialised region, making regional comparisons and cross-comparative analyses challenging and even unfeasible in several situations. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs and used RDS or convenience samples. Both may introduce selection biases, usually not taken into consideration regarding statistical inference. Although probability samples are not applicable to hard-to-reach, marginalised populations, there are several strategies to improve statistical inference. Unfortunately, the vast majority of such studies tend to ignore such methods and tools. Lastly, the assessment of barriers or facilitators predominantly relied on descriptive studies. Statistical associations assessed with the proper methods are seldom explored. Studies using the methods and analytic strategies of the modern science of causality are virtually absent.

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this review has several implications for HIV policies and interventions aimed at enhancing HIV testing among MSM and TGW. Interventions and educational campaigns designed to enhance individuals’ self-perception and self-awareness regarding HIV infection should be reinforced as they can substantially boost HIV testing, promoting early detection and timely referral to treatment. Health managers should prioritise the establishment of inclusive and culturally sensitive testing spaces for MSM, TGW, and the whole LGBTQIAPN + community. An integrated network should comprise primary care units and HIV/AIDS referral centres, as well as social venues. It is imperative to enforce anti-discriminatory legislation and norms and to establish ongoing educational initiatives on HIV/AIDS for specific segments, the general population, and healthcare practitioners.

Educational campaigns should not only highlight the criminal consequences of discrimination but also strive to diminish the stigma and bias surrounding HIV and the LGBTQIAPN + community. Establishing transparent protocols that not only ensure confidentiality but also guarantee that only healthcare professionals and patients will have access to HIV test results is crucial for advancing HIV testing among vulnerable populations. The full integration of testing, counselling, agile referral to treatment, and a comprehensive array of preventive measures is key to the effort to eliminate HIV by 2030, as mandated by the UN sustainable development goals (SDG-3). This goal appears not to be achievable in Brazil and several other countries, especially after the disruption secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of far-right governments. The latter fuelled discrimination and homo- and transphobic attitudes and policies, challenging decades-long efforts toward health promotion and protection of the human rights of such stigmatised populations. Notwithstanding, elimination should remain a guiding principle: there is no room for inertia and prejudice.

Study registration protocol number

The study protocol is publicly accessible at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WKYFP.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (34.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Research Council (CNPq) (CNPq/MS-DIAHV N° 24/2019) for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This study was funded by National Research Council (CNPq) (CNPq/MS-DIAHV N° 24/2019).

References

- Alizade, M., Farshbaf-Khalili, A., Malakouti, J., & Mirghafourvand, M. (2021). Predictors of preventive behaviors of AIDS/HIV based on health belief model constructs in women with high-risk sexual behaviors: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10(1), 446. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1046_20

- Almeida, L. F., Guimarães, M. D. C., Dourado, I., Veras, M. A. S. M., Magno, L., Leal, A. F., Kerr, L. R. S., Kendall, C., Pontes, A. K., & Rocha, G. M. (2021). Envolvimento em organizações não governamentais e a participação em ações de prevenção ao HIV/aids por homens que fazem sexo com homens no Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 37, e00150520. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00150520

- Andrinopoulos, K., Hembling, J., Guardado, M.E., Hernández, F.M., Nieto, A.I., & Melendez, G. (2015). Evidence of the negative effect of sexual minority stigma on HIV testing among MSM and transgender women in San Salvador, El Salvador. AIDS and Behavior, 19(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0813-0

- Bastos, F. I. P. M., Coutinho, C., & Malta, M. (2018). Estudo de Abrangência Nacional de Comportamentos, Atitudes, Práticas e Prevalência de HIV, Sífilis e Hepatites B e C entre Travestis - Relatório Final Pesquisa DIVaS (Diversidade e Valorização da Saúde). Retrieved March 8, 2023, from https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/handle/icict/49082

- Bay, M. B., Freitas, M. R., Lucas, M. C. V., Souza, E. C. F., & Roncalli, A. G. (2019). HIV testing and HIV knowledge among men who have sex with men in Natal, Northeast Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 23(1), 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2019.01.003

- Bien, C. H., Muessig, K. E., Lee, R., Lo, E. J., Yang, L. G., Yang, B., Peeling, R. W., & Tucker, J. D. (2015). HIV and syphilis testing preferences among men who have sex with men in South China: A qualitative analysis to inform sexual health services. PLoS One, 10(4), e0124161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0124161

- Brito, A. M., Kendall, C., Kerr, L., Mota, R. M. S., Guimarães, M. D. C., Dourado, I., Pinhp, A. A., Benzaken, A. S., Brignol, S., & Reingold, A. L. (2015). Factors associated with low levels of HIV testing among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Brazil. PLoS One, 10(6), e0130445. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130445

- Cooke, I. J., Jeremiah, R. D., Moore, N. J., Watson, K., Dixon, M. A., Jordan, G. L., Murray, M., Keeter, M. K., Hollowell, C. M., & Murphy, A. B. (2017). Barriers and facilitators toward HIV testing and health perceptions among African-American men who have sex with women at a South Side Chicago Community Health Center: A pilot study. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00286

- Costa, A. B., Fontanari, A. M. V., Catelan, R. F., Schwarz, K., Stucky, J. L., Rosa Filho, H. T., Pase, P. F., Gagliotti, D. A. M., Saadeh, A., Lobato, M. I. R., Nardi, H. C., & Koller, S. H. (2018). HIV-related healthcare needs and access barriers for Brazilian transgender and gender diverse people. AIDS and Behavior, 22(8), 2534–2542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-2021-1

- Cota, V. L., & Cruz, M. M. (2021). Access barriers for men who have sex with men for HIV testing and treatment in Curitiba (PR). Saúde Debate, 45, 129. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-1104202112911I

- Creasy, S. L., Henderson, E. R., Bukowski, L. A., Matthews, D. D., Stall, R. D., & Hawk, M. E. (2019). HIV testing and ART adherence among unstably housed black men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 23(11), 3044–3051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02647-w

- Cruz, M. M., Cota, V. L., Lentini, N., Bingham, T., Parent, G., Kanso, S., Rosso, L. R. B., Almeida, B., Torres, R. M. C., Nakamura, C. Y., & Santelli, A. C. F. E. S. (2021). Comprehensive approach to HIV/AIDS testing and linkage to treatment among men who have sex with men in Curitiba, Brazil. PLoS One, 16(5), e0249877. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249877

- De Boni, R. B., Veloso, V. G., Fernandes, N. M., Lessa, F., Corrêa, R. G., Lima, R. D. S., Cruz, M., Oliveira, J., Nogueira, S. M., Jesus, B., Reis, T., Lentini, N., Miranda, R. L., Bingham, T., Johnson, C. C., Barbosa Junior, A., & Grinsztejn, B. (2019). An internet-based HIV self-testing program to increase HIV testing uptake among men who have sex with men in Brazil: Descriptive cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(8), e14145. https://doi.org/10.2196/14145

- Dourado, I., Silva, L. A. V., Magno, L., Lopes, M., Cerqueira, C., Prates, A., Brignol, S., & MacCarthy, S. (2016). Construindo pontes: a prática da interdisciplinaridade. Estudo PopTrans: um estudo com travestis e mulheres transexuais em Salvador, Bahia, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 32(32), e00180415. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00181415

- Elorreaga, O. A., Torres, T. S., Vega-Ramirez, E. H., Konda, K. A., Hoagland, B., Benedetti, M., Pimenta, C., Diaz-Sosa, D., Robles-Garcia, R., Grinsztejn, B., Caceres, C. F., & Veloso, V. G. (2022). Awareness, willingness and barriers to HIV self-testing (HIVST) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Brazil, Mexico, and Peru: A web-based cross-sectional study. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(7), e0000678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000678

- Freeman, A. E., Sullivan, P., Higa, D., Sharma, A., MacGowan, R., Hirshfield, S., Greene, G. J., Gravens, L., Chavez, P., McNaghten, A. D., Johnson, W. D., Mustansk, IB., & eSTAMP Study Group. (2018). Perceptions of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in the United States: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention, 30(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2018.30.1.47

- Frescura, L., Godfrey-Faussett, P., Feizzadeh, A. A., El-Sadr, W., Syarif, O., & Ghys, P. D. (2022). Achieving the 95 95 95 targets for all: A pathway to ending AIDS. PLoS One, 17(8), e0272405. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272405

- Gamarel, K. E., Nelson, K. M., Stephenson, R., Rivera, O. J. S., Chiaramonte, D., & Miller, R. L. (2018). Anticipated HIV stigma and delays in regular HIV testing behaviors among sexually-active young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS and Behavior, 22(2), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-2005-1

- Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S. I., Hanning, R. M., & Leatherdale, S. T. (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0

- Golub, S. A., & Gamarel, K. E. (2013). The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(11), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2013.0245

- Gomes, R. R. F. M. (2014). Conhecimento sobre HIV/Aids entre homens que fazem sexo com homens em 10 cidades brasileiras. Retrieved March 7, 2023 https://repositorio.ufmg.br/handle/1843/BUOS-9MRGQF

- Gonçalves, V. F., Kerr, L. R. F. S., Mota, R. S., Macena, R. H. M., Almeida, R. L., Freire, D. G., Brito, A. M., Dourado, I., Atlani-Duault, L., Vidal, L., & Kendall, C. (2016). Incentives and barriers to HIV testing in men who have sex with men in a metropolitan area in Brazil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 32(5), https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00049015

- Hamilton, A., Shin, S., Taggart, T., Whembolua, G. L., Martin, I., Budhwani, H., & Conserve, D. (2020). HIV testing barriers and intervention strategies among men, transgender women, female sex workers and incarcerated persons in the Caribbean: a systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 96(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053932

- Hawk, M. E., Chung, A., Creasy, S. L., & Egan, J. E. (2020). A scoping review of patient preferences for HIV self-testing services in the United States: Implications for harm reduction. Patient Preference and Adherence, 14, 2365–2375. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S251677

- Hubbard, S. J., Ma, M., Wahnich, A., Clarke, A., Myers, J. E., & Saleh, L. D. (2020). #Testathome: Implementing 2 phases of a HIV self-testing program through community-based organization partnerships in New York City. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 47(5S), S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001151

- Iribarren, S., Lentz, C., Sheinfil, A.Z., Giguere, R., Lopez-Rios, J., Dolezal C., Frasca, T., Balán, I.C., Tagliaferri Rael, C., Brown, W. 3rd, Cruz Torres, C., Crespo, R., Febo, I., Carballo-Diéguez, A. (2020). Using an HIV self-test kit to test a partner: Attitudes and preferences among high-risk populations. AIDS and Behavior, 24(11), 3232–3243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02885-3

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2014). 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Retrieved March 8, 2023 https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf

- Khan, M. N. M., Sarwar, G., Irfan, S. D., Gourab, G., Rana, A. K. M. M., & Khan, S. I. (2022). Understanding the barriers of HIV testing services for men who have sex with men and transgender women in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 42(3), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X21995672

- Koutentakis, K., Hoyos, J., Rosales-Statkus, M. E., Guerras, J. M., Pulido, J., De La Fuente, L., & Belza, M. J. (2019). HIV self-testing in Spain: A valuable testing option for men-who-have-sex-with-men who have never tested for HIV. PLoS One, 14(2), e0210637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210637

- Leite, B. O., Medeiros, D. S., Magno, L., Bastos, F. I., Coutinho, C., Brito, A. M., Cavalcante, M. S., & Dourado, I. (2021). Association between gender-based discrimination and medical visits and HIV testing in a large sample of transgender women in northeast Brazil. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01541-z

- Lima, V. V. P. C. (2019). A negação de rótulos e fatores associados como parte do estigma sofrido por homens que fazem sexo com outros homens no Brasil. Retrieved March 15, 2023 https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/38463.

- Lippman, S. A., Périssé, A. R. S., Veloso, V. G., Sullivan, P. S., Buchbinder, S., Sineath, R. C., & Grinsztejn, B. (2014). Acceptability of self-conducted home-based HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Brazil: data from an on-line survey. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 30(4), 724–734. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00008913

- Magno, L., Leal, A. F., Knauth, D., Dourado, I., Guimarães, M. D. C., Santana, E. P., Jordão, T., Rocha, G. M., Veras, M. A., Kendall, C., Pontes, A. K., Brito, A. M., & Kerr, L. (2020). Acceptability of HIV self-testing is low among men who have sex with men who have not tested for HIV: a study with respondent-driven sampling in Brazil. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20(1), 865. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05589-0

- Magno, L., Pereira, M., Castro, C. T., Rossi, T. A., Azevedo, L. M. G., Guimarães, N. S., & Dourado, I. (2023). HIV testing strategies, types of tests, and uptake by men who have sex with men and transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 27(2), 678–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03803-5

- Melo, E. M. O. (2012). Incentivos e barreiras para a realização do teste de HIV entre homens que fazem sexo com homens. Retrieved March 8, 2023, from http://repositorio.ufc.br/handle/riufc/6952

- Monteiro, S., & Brigeiro, M. (2019). Experiências de acesso de mulheres trans/travestis aos serviços de saúde: avanços, limites e tensões. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 35(35), e00111318. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00111318

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4

- Nowak, R. G., Mitchell, A., Crowell, T. A., Liu, H., Ketende, S., Ramadhani, H. O., Ndembi, N., Adebajo, S., Ake, J., Michael, N. L., Blattner, W. A., Baral, S. D., & Charurat, M. E. (2019). Individual and sexual network predictors of HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 80(4), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001934

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 31. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Peterson, J. L., Miner, M. H., Brennan, D. J., & Rosser, B. R. S. (2012). HIV treatment optimism and sexual risk behaviors among HIV positive African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2012.24.2.91

- Pinheiro Júnior, F. M. L., Kendall, C., Martins, T. A., Mota, R. M. S., Macena, R. H. M., Glick, J., Kerr-Correa, F., & Kerr, L. (2016). Risk factors associated with resistance to HIV testing among transwomen in Brazil. AIDS Care, 28(1), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1066751

- Pinto, L. F. S., Perini, F. B., Aragón, M. G., Freitas, M. A., & Miranda, A. E. (2021). Brazilian protocol for sexually transmitted infections, 2020: HIV infection in adolescents and adults. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 54(Suppl 1), e2020588. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-588-2020

- Pitasi, M. A., Clark, H. A., Chavez, P. R., DiNenno, E. A., & Delaney, K. P. (2020). HIV testing and linkage to care among transgender women who have sex with men: 23 U.S. cities. AIDS and Behavior, 24(8), 2442–2450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02804-6

- Porto, R. L. A. (2018). Sentidos atribuídos a partir do diagnóstico de HIV/AIDS em mulheres transgênero à luz da fenomenologia de Heidegger. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://tede.ufam.edu.br/handle/tede/6752

- Price, D. M., Howell, J. L., Gesselman, A. N., Finneran, S., Quinn, D. M., & Eaton, L. A. (2019). Psychological threat avoidance as a barrier to HIV testing in gay/bisexual men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-0003-z

- Redoschi, B. R. L. (2016). Teste anti-HIV entre homens que fazem sexo com homens em São Paulo: busca espontânea rotineira e episódica. Retrieved March 15, 2023, from https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/6/6136/tde-29032016-144517/pt-br.php

- Sandfort, T. G. M., Dominguez, K., Kayange, N., Ogendo, A., Panchia, R., Chen, Y. Q., Chege, W., Cummings, V., Guo, X., Hamilton, E. L., Stirratt, M., & Eshleman, S. H. (2019). HIV testing and the HIV care continuum among sub-Saharan African men who have sex with men and transgender women screened for participation in HPTN 075. PLoS One, 14(5), e0217501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217501

- Sevelius, J., Murray, L. R., Fernandes, N. M., Veras, M. A., Grinsztejn, B., & Lippman, S. A. (2019). Optimising HIV programming for transgender women in Brazil. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(5), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1496277

- Sousa, A. F. L., Queiroz, A. A. F. L. N., Fronteira, I., Lapão, L., Mendes, I. A. C., & Brignol, S. (2019). HIV testing among middle-aged and older men who have sex with men (MSM): A blind spot? American Journal of Men's Health, 13(4), 155798831986354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319863542

- Souza, M. H. T. D., & Pereira, P. P. G. (2015). Health care: The transvestites of Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Texto & Contexto - Enfermagem, 24(1), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015001920013

- Torres, T. S., De Boni, R. B., Vasconcellos, M. T., Luz, P. M., Hoagland, B., Moreira, R. I., Veloso, V. G., & Grinsztejn, B. (2018). Awareness of prevention strategies and willingness to use preexposure prophylaxis in Brazilian men who have sex with men using apps for sexual encounters: Online cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.8997

- Torres, T. S., Luz, P. M., De Boni, R. B., Vasconcellos, M. T. L., Hoagland, B., Garner, A., Moreira, R. I., Veloso, V. G., & Grinsztejn, B. (2019). Factors associated with PrEP awareness according to age and willingness to use HIV prevention technologies: the 2017 online survey among MSM in Brazil. AIDS Care, 31(10), 1193–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1619665

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Vasconcelos, R., Avelino-Silva, V. I., de Paula, I. A., Jamal, L. F., Gianna, M. C., Santos, F., Camargo, R., Barbosa, E., Casimiro, G., Cota, V., Abbate, M. C., Cruz, M., & Segurado, A. C. (2022). HIV self-test: A tool to expand test uptake among men who have sex with men who have never been tested for HIV in São Paulo, Brazil. HIV Medicine, 23(5), 451–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13178

- Volk, J. E., Lippman, S. A., Grinsztejn, B., Lama, J. R., Fernandes, N. M., Gonzales, P., Hessol, N. A., & Buchbinder, S. (2016). Acceptability and feasibility of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in Peru and Brazil. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 27(7), 531–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462415586676

- Wilson, E. C., Jalil, E. M., Castro, C., Fernandez, N. M., Kamel, L., & Grinsztejn, B. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to PrEP for transwomen in Brazil. Global Public Health, 14(2), 300–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2018.1505933

- Wilson, E. C., Jalil, E. M., Moreira, R. I., Velasque, L., Castro, C. V., Monteiro, L., Veloso, V. G., & Grinsztejn, B. (2021). High risk and low HIV prevention behaviours in a new generation of young trans women in Brazil. AIDS Care, 33(8), 997–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1844859