ABSTRACT

Urban inequalities are exacerbated due to rapid urbanisation. This is also evident within slums in low- and middle-income countries, where high levels of heterogeneity amongst the slum population lead to differential experiences in Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) and housing access. This scoping review provides evidence of the interconnection of WASH and housing and presents barriers to access and the consequences thereof for slum dwellers. It does so while considering the social stratification amongst urban slum dwellers and their lived experiences. A systematic search of journal articles was conducted in November 2022 in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. A total of 33 papers were identified which were full text reviewed and data extracted. Infrastructure, social and cultural, socio-economic, governance and policy and environmental barriers emerged as general themes. Barriers to WASH and housing were more frequently described concerning women and girls due to gender norms within WASH and the home. Barriers to WASH lead to compromised health, socio-economic burdens, and adverse social impacts, thus causing residents of slums to navigate their WASH mobility spatially and over time. Insights from this review underscore the need for an intersectional approach to understanding access inequalities to WASH and housing.

1. Introduction

The world has been urbanising at rapid pace and presently half of the world’s population lives in cities (Spencer, Citation2021). One in seven people are estimated to live in slums. To cater to the growing urban population and meet demand, new infrastructure must be set up such as schools, hospitals, houses and other basic services like water and sanitation. The growth of cities is generally associated with increasing inequalities (Brelsford et al., Citation2017). As it is difficult to keep up with the rapid increase in urban populations, challenges arise such as inadequate housing, insecure tenure, and limited access to basic services (Lucci et al., Citation2015). This is coupled with the expansion of existing, or emergence of new slums. Maintaining basic services in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in the face of increasing urbanisation and limited institutional capacity, presents a significant challenge (Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020). Thus, the rapid pace of urbanisation exacerbates inequalities in accessing adequate Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) services and housing in urban areas (UNICEF, Citation2020), whereby the effects are experienced differently within urban populations. This is also the case for urban slum dwellers. WASH service delivery has been described as a ‘wicked problem’, meaning it is complex, multifaceted, and difficult to solve (Carvalho & Van Tulder, Citation2022; Singh Chouhan et al., Citation2022). It has been acknowledged that urban WASH is interconnected with broader poverty-related issues such as tenure security, and thus necessitates a trans-sectoral perspective (McGranahan, Citation2013) and a systems approach (Walters et al., Citation2022). Thus, in this review we approach WASH interconnected to the housing domain.

Poor access to WASH leads to various diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, typhoid, and hepatitis. Diarrhoea makes up 57% of global disease burden and is the leading cause of death among under-five children in developing countries (Saroj et al., Citation2020). Moreover, poor housing quality in slums is linked to threats to respiratory health due to indoor household air pollution (Anand & Phuleria, Citation2022; Checkley et al., Citation2016). Thus, access to housing and WASH services in slums is crucial to human well-being, fostering improved health outcomes, promoting social inclusion, and supporting sustainable urban development.

The United Nations, in 1996, provided the following definition of adequate housing: ‘Adequate housing means more than a mere roof over one’s head. It encompasses sufficient privacy, space, physical accessibility, security, tenure security, structural stability, durability, appropriate lighting, heating, and ventilation, essential basic infrastructure like water supply, sanitation, and waste management, suitable environmental quality, health-related considerations, and a location that is both adequate and accessible concerning work and essential facilities, all of which should be attainable at an affordable cost.’ (Singh et al., Citation2022). UN-Habitat recognises that the right to adequate housing includes ensuring access to adequate services, such as WASH (UN-Habitat, Citation2009). As of 2010, the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation stands independently as a recognised human right since its adoption by the UN General Assembly. The UN resolution acknowledges that safe and clean drinking water and sanitation are crucial to the realisation of all human rights (OHCHR, Citationn.d.). However, the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation is also embedded in the right to an adequate standard of living (Article 11(1) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) (WWAP, Citation2019). Planning for rapid urbanisation has been difficult and consequently, an increasing number of people live in slums that lack access to the most basic of services (Gulyani et al., Citation2010). Although the proportion of the global urban population living in slums declined slightly, from 25.4% to 24.2% between 2014 and 2020, the absolute number of slum dwellers continues to rise with increasing urbanisation (UN-Habitat, Citation2023). It is estimated that approximately 1 billion people live in informal settlements and slums, with roughly 350 million to 500 million of them being children under the age of 18 (Singh et al., Citation2022; UNICEF, Citation2018). UN-Habitat estimates that over 3 billion people will live in slums or slum-like conditions by the year 2050 (UN-Habitat, Citation2023).

In slums, the interconnectedness of WASH and housing becomes evident as access is influenced by various social dimensions. For example, women – who are regularly tasked with domestic chores – undergo hardships in arranging the water management of their household when access to adequate housing with water on the premises is unavailable (Sarkar, Citation2020). Moreover, slums are characterised by high levels of heterogeneity among their inhabitants (Rigon, Citation2022), leading to differential experiences amongst social identities in accessing housing and WASH services. Whilst housing and WASH access is a challenge that impacts all slum residents, some social groups in particular face greater challenges in access, for example, due to age, socio-economic status, gender or physical and mental disabilities. Furthermore, differentiated access inequalities within these groups exist when social identities intersect. Women, for example, rely on toilets, water, and private spaces for bathing/cleaning to address their bodily needs and fulfil socio-economic roles (Chant, Citation2013). However, the presence of toilets does not ensure women and girls use these facilities due to attacks and fear of violence around their use (O'Reilly, Citation2016).

Although there is a substantial body of research on women and their access to sanitation facilities (e.g. Pommells et al., Citation2018; Wali et al., Citation2020), there is a notable lack of studies that examine access inequalities to infrastructures and services in slums related to other social identities (Rigon, Citation2022). Moreover, limited attention has been given to the non-health consequences of poor WASH provision (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, few studies have explored the intersection of WASH and housing in relation to access disparities. Here, access to housing and WASH is predominantly researched in terms of tenure status and water access (e.g. Joshi et al., Citation2023) and land tenure security and investments in housing – including WASH infrastructures within the house (e.g. Nakamura, Citation2016; Nyametso, Citation2012). Therefore, this paper is centred on the domains of WASH, as well as aspects of housing, encompassing both the physical and social dimensions within the built environment. Furthermore, in this review, the term ‘slum(s)’ refers to both slum(s) and informal settlement(s). In cases where the review refers to specific publications, the term in the original publication was used. We acknowledge that the term ‘slum(s)’ can be controversial and carry negative connotations. In other instances, scholars, organisations and individuals identify themselves with a positive use of the term. An example of this is Slum Dwellers International, who have been deliberately using the term ‘slum(s)’ to reclaim it and emphasise slum communities positively (Khan et al., Citation2023). Also, the use of the terminology varies depending on the context and user (e.g. Rashid, Citation2009). The search string in this review included variations of slums to capture a variety of angles including tenure and land status. Moreover, this review uses ‘slum(s)’ because its UN definition encompasses the scope of the review. Informal settlements are associated with a lack of tenure security, formal basic services and a lack of housing compliance with current planning and building regulations. Slums are also associated with this but are more specifically linked to a lack of access to improved water sources, improved sanitation facilities, and sufficient living area in addition to a lack of housing durability and tenure security (UNSD, Citation2021).

The aim of this scoping review is three-fold, namely (1) synthesising evidence on the interconnection of WASH and housing, (2) presenting access inequalities approached from a user-centred perspective that considers the social stratification amongst urban slum dwellers and their lived experiences, and (3) compiling suggestions for policy and interventions derived from the selected studies. The guiding question of this scoping review is the following: ‘How are slum dwellers impacted by access inequalities to housing and WASH services in slums in low- and middle-income countries?

2. Methodology

A scoping review was found most appropriate as it provides a broad overview of evidence on the topic (Peters et al., Citation2020). Given the novelty of the topic and thus the limited availability of evidence, a scoping review was chosen as the preferred method (Munn et al., Citation2018). The protocol (Appendix 1) for this study was developed in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020) and was not registered to accommodate the potential evolution of the topic through thorough literature exploration.

2.1. Eligibility criteria

A systematic search of published articles was carried out in PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science in November 2022. PubMed was specifically chosen as poor housing and WASH are linked to health-related problems. Scopus and Web of Science were chosen for their large citation databases across disciplines. To formulate the population, intervention, outcomes and context, the PICOC framework was utilised. After an initial scoping search, the PICOC elements from the initial review question were further refined and the following elements were considered: the population consists of slum dwellers, the intervention is access to housing and WASH services, the outcomes are experiences around access inequalities and the context is slums in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. A list of synonyms for the PICOC elements was created to construct the search string. The synonyms and search string can be found in Appendix 2 and 3, respectively. The concepts of the PICOC framework were defined as follows:

Slum dwellers are individuals or families (households) residing in slums, representing a diverse range of social identities. Research on inequalities is mostly conducted using a gendered lens (e.g. Rakodi (Citation2015)), or by approaching urban slum dwellers as a homogenous group (Banerjee & Chattopadhyay, Citation2020) who look at slum households vs. non-slum households (Rigon, Citation2022) excluding other forms of inequalities that affect access (e.g. class, age, religion, disabilities). However, this scoping review incorporates various social identities and considers multiple forms of inequality that impact access. By adopting a broader approach, this review seeks to provide evidence of inequalities on multiple fronts and their impact on slum dwellers.

Access inequalities refer to the condition or state in which a person experiences exclusion in accessing and thus utilising housing or WASH infrastructures and/or services. This does not only entail a total denial of access but also reduced access, i.e. the extent to which the effort required to gain access negatively impacts someone's life. This not only refers to spatial considerations (physical barriers), but also temporal (opening hours, reliability of water supply) and social. The latter is based on a person’s position in society/community/other given context (e.g. socio-economic status, gender, age, (dis)ability, caste) and external factors that play into vulnerabilities and an individual’s or group’s power to decide. Additionally, this review examines access inequalities within household settings, rather than focusing on WASH facilities in schools or workplaces, as the primary emphasis of this review lies on WASH and housing

Adequate housing refers to access to safe, healthy and affordable infrastructure that protects people from the elements (e.g. heat or rain) (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015) with access to basic services (within or close to the house). Besides, the house should be in reasonable proximity to the residents’ place of work/education (Singh et al., Citation2022). In addition to the physical characteristics, housing refers to a place where family units co-exist, children are raised, traditions and food habits are practised, lends residents privacy and dignity, and simply have a home to call their own (Akatch & Kasuku, Citation2002).

WASH refers to access to safe drinking water for consumption and washing and access to safe and sanitary toilets that safely separate waste from human contact, provide shelter and dignity to the person using it, respect cultural practices, shared by a reasonable number of people (Cities Alliance, Citationn.d.) as well as the opportunity to maintain hygienic conditions such as handwashing with soap, showering and bathing.

Slums are areas that provide shelter to slum dwellers (Wekesa et al., Citation2011), where housing is generally affordable and structures are regularly not in compliance with safe planning and building regulations, often accompanied by a lack of basic services, insecure land and tenure rights and exclusion.

LMICs refers to low- and middle-income regions in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. To ensure a geographical spread of LMICs globally in our review, our focus centres on three broad regions (Latin America, Africa and Asia). Within these regions, we examined the proportion of slum dwellers. The proportion of slum dwellers is particularly high in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Amegah, Citation2021). Over half of the urban population in Sub-Saharan Africa lives in slums (UN-Habitat, Citation2020) and one in three in South Asia (Auerbach & Thachil, Citation2023). Therefore, in addition to Latin America, this review is focusing specifically on sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, rather than the entire continent of Africa and Asia. Lastly, the studies selected for this scoping review have an urban or peri-urban focus. Although urban areas have an overall higher sanitation coverage than rural areas, access to sanitation in urban areas is accompanied by greater inequalities (UNICEF, Citation2020).

In addition to the PICOC criteria, Non-English published articles were not considered, as non-English languages increase resource challenges with respect to cost, time, and expertise in non-English languages. The studies selected for the review date from 2000 to 2022, aligning with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) period. The scope of the review was intentionally directed towards studies employing either a qualitative or mixed methods approach (including various forms of interviews, observations, case studies, and Focus Group Discussions). Studies that report secondary qualitative data were also included. Studies with a strictly quantitative approach were excluded for multiple reasons. This review aims to provide evidence of people’s lived experiences, beyond quantitative data. Focusing on solely quantitative methodologies in the water domain coupled with housing and land access fails to give insights into the intricate power dynamics and lived experiences at play (Nastar et al., Citation2019). Moreover, several studies with a quantitative approach that were excluded used national survey data. Vulnerable populations may be unintentionally excluded from these surveys, or their data is masked in urban averages (Thomson et al., Citation2021). The review exclusively focuses on scientific literature, excluding grey literature due to its vastness and variability across different organisations and countries. Focusing solely on scientific papers ensures a more standardised and consistent analysis of the topic.

2.2. Screening of records

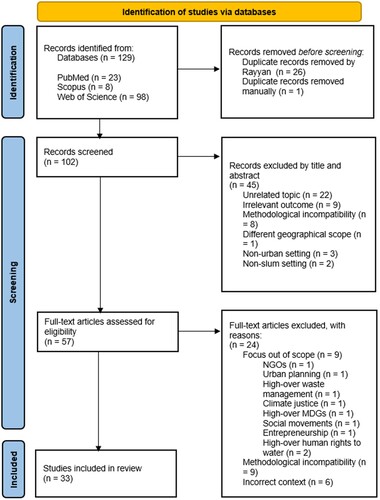

A search across three databases yielded a total of 129 published articles, all of which were uploaded into the open-access software Rayyan (https://rayyan.ai) to consolidate all records and facilitate the systematic screening, reviewing, and selection process with an additional reviewer. Following the removal of duplicates, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 102 records against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. These criteria were discussed to avoid ambiguity. Any discrepancies and doubts between the two reviewers were discussed, leading to the exclusion of 45 records. Subsequently, the full texts of the remaining 57 records were evaluated for eligibility by one reviewer, resulting in the exclusion of 24 records. Ultimately, a total of 33 published articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis ().

2.3. Data extraction and analysis

In the data extraction phase, a total of 33 articles were selected by one author based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A data extraction table was created in Excel that captured the following information: author(s), year of publication, geographical focus, focus domain, study population, barriers to access, consequences thereof and proposed policy and/or intervention recommendations (Appendix 4). The analysis of the articles occurred in two stages. First, data was extracted on the study characteristics (author(s), year of publication, geographical focus, focus domain, study population). Second, a thematic analysis was conducted to extract information regarding barriers to access, consequences thereof and proposed policy and/or intervention recommendations.

2.4. Synthesis of results

This scoping review presents its findings in a narrative summary of the access inequalities experienced by a range of slum dwellers. The review will present findings in three sections: (1) findings on the interconnection between WASHFootnote1 and housing (2) barriers to access and consequences thereof and (3) policy and/or intervention recommendations.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of sources of evidence

One of the objectives of this paper was to provide evidence of the interconnection of housing and WASH. A set of N = 11 studies present the interconnection between housing and WASH or a subdomain of WASH. One study (Uddin, Citation2018) does not focus on their integration as such, but separately as dimensions of sustainability. While the interconnection between housing and WASH is a primary focus in some studies, in others, it is a side order or WASH is compartmentalized within the broader category of basic services. Moreover, several studies primarily concentrate on housing, considering WASH as an essential component of basic services. Furthermore, in terms of social identities, the scope of the studies varies. Some studies focus on slum dwellers as a homogeneous group, while others delve into specific social identities or explore the intersection of multiple identities. However, gender emerges as the most prominent social identity researched regarding housing and WASH in the selected studies, with N = 14 studies specifically focusing on women and/or girls, as also noted by Rigon (Citation2022).

3.2. Interconnection WASH and housing

Papers vary in their conceptualizations of housing in relation to WASH. These aspects include landlord-tenant relationship (Foggitt et al., Citation2019), the quality and location of the physical housing structure in the settlement (Butcher, Citation2021; Cherunya et al., Citation2020), housing formalisation (Rodina & Harris, Citation2016), land tenure and/or security of settlements (Butcher, Citation2021; Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Rashid, Citation2009; Richmond et al., Citation2018; Singh, Citation2022; Vu et al., Citation2022), the home as the locus of domestic spaces – including parental responsibilities – (Baruah, Citation2007; Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Panchang, Citation2021; Vu et al., Citation2022) and of economic activities (Baruah, Citation2007; Cherunya et al., Citation2020).

Several studies emphasised the influence of tenure status on the availability and usage of toilet facilities (Ali & Stevens, Citation2009; Butcher, Citation2021; Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Vu et al., Citation2022). The absence of legal land tenure hampers both residents and local authorities to invest in permanent services (Ali & Stevens, Citation2009). Rodina and Harris (Citation2016) exemplify how housing formalisation including an in-house water connection shapes citizenship and invokes notions of responsible water use. In certain cases, landlords permit their tenants to access toilets within the housing premises (Foggitt et al., Citation2019). Moreover, the absence of access to adequate facilities leads to the practice of open defecation (OD), which is the practice of defecating in open spaces such as in water bodies, along railway tracks and in bushes. OD poses a significant threat to public health. Furthermore, housing, when defined as a space where domestic tasks occur, is closely linked to access to WASH (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). This connection is highly gendered since women are often primarily responsible for domestic chores and childcare (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Foggitt et al., Citation2019). This is also evident from an economic perspective, where homes may function as workspaces, workshops, warehouses, stores and other economic hubs where water connections are essential for the production process (Baruah, Citation2007). The interconnection between housing and WASH is further evident in situations where individuals rely, either partially or entirely, on public WASH facilities. The proximity of the house to these facilities plays a significant role in shaping access to WASH services (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Rodina & Harris, Citation2016; Vu et al., Citation2022; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021). Access inequalities are exacerbated in cases where specific social groups are socially excluded (Butcher, Citation2021). On the contrary, Panchang (Citation2021) exemplifies how Community Toilet Blocks (CTB) near the house are associated with the stigma of uncleanliness around the home. On a settlement level, the legal status of the settlement also influences the provision of basic services. In some instances, national policies dictate the status of slum settlements, which can impede the provision of adequate WASH services in informal settlements by the government (Singh, Citation2022).

3.3. Barriers and social identities

The following themes emerged regarding barriers to housing and WASH facilities and services: (1) infrastructure-related, (2) social and cultural, (3) economic, (4) governance and policy, and (5) environmental. The factors exhibit overlap and/or demonstrate interrelationships. Moreover, all these factors are related to various social identities. The following paragraph will delve into the barriers derived from the selected papers and, where relevant, reflect on their relation to social identities.

3.3.1. Infrastructure-related

Limited options for accessing WASH facilities arise for certain social groups, both in household and public settings, due to inadequate infrastructures. Some households are not able to construct a household toilet due to limited space (Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Nowreen et al., Citation2022; Okurut et al., Citation2015; Peprah et al., Citation2015; Sahoo et al., Citation2015). Access can also be denied for people in cases where multiple households share a toilet infrastructure. Factors such as poor physical toilet condition and unpleasant odours of the toilet (Foggitt et al., Citation2019), lead to increased utilisation of public restroom facilities.

In some cases, people have no alternative to using a public toilet (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). Certain social groups are restricted in their toilet options. Older adults might continue using toilets in poor conditions if they are conveniently situated (Foggitt et al., Citation2019) and encounter mobility restrictions at public toilets (Peprah et al., Citation2015). The distance from the home to the shared facility has been mentioned as a barrier, as well as the waiting time due to overcrowding (Nowreen et al., Citation2022; Panchang, Citation2021; Rashid, Citation2009; Vu et al., Citation2022; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021). This is also the case for distance to water pumps (Nowreen et al., Citation2022). Consequently, a trade-off emerges between the convenience of proximity and the quality of the toilet facility. The same issue extends to children, as caregivers perceive public toilets as unsafe, thereby preventing their children from using these facilities independently. Additionally, caregivers are often constrained by time limitations, making it difficult for them to accompany their children to public toilets (Foggitt et al., Citation2019) and even if they do it is a time-consuming activity especially with many children (Cherunya et al., Citation2020).

Natural or physical barriers to water points and public toilets (Adams et al., Citation2022; Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Sahoo et al., Citation2015) and conflicts around public toilets or water points (Adams et al., Citation2022; Biswas, Citation2020; Sahoo et al., Citation2015) also serve as barriers for access, especially for women. Water and sanitation challenges are exacerbated for females with disabilities, as they typically need more time in the restroom, may encounter impatience from fellow users (Chowdhury et al., Citation2022) and experience difficulties accessing disabled-friendly facilities (Nowreen et al., Citation2022).

Fear of being attacked and harmed hampers women and girls from public toilet use at night (Rashid, Citation2009). Design features play a role, whereby inadequate design features, such as lack of lighting and poor toilet structure act as barriers to toilet access (Kwiringira et al., Citation2014; Nagpal et al., Citation2021; Nowreen et al., Citation2022; Vu et al., Citation2022; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021). Toilet infrastructures with improper waste management systems in place (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015; Nowreen et al., Citation2022; Uddin, Citation2018) and/or lack of hygienic maintenance (Kwiringira et al., Citation2014; Winter et al., Citation2019), also act as a barrier to accessing toilet facilities. This is gendered as improper Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) (e.g. absence of sanitary bins, lack of private and hygienic toilets with functioning doors and locks, separate gender stalls, and running water) has adverse effects on women’s sanitation experiences (Nowreen et al., Citation2022; Winter et al., Citation2019). The lack of space and high population density limits the privacy, safety and security that women need, especially during menstruation (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019). This situation is further exacerbated for women and girls with intellectual or physical impairment as their increased vulnerability places them at an increased risk of being deprived of access to WASH services, including adequate MHM (Nowreen et al., Citation2022).

The spatial positioning of the house within the settlement is a crucial factor that relates directly to access denial of WASH facilities and the trade-offs that emerge (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Panchang, Citation2021). Exclusion from WASH facilities is fuelled by biased perceptions of locations within the settlement, marginalising certain slum residents even further. Housing may also fail to adhere to the necessary standards of habitability, for example with the absence of more than one room (Uddin, Citation2018), the absence of WASH infrastructures within the housing unit (Sheuya et al., Citation2007), the lack of external infrastructures by service providers for WASH facilities to function (e.g. availability of water) (Cherunya et al., Citation2020), or denied access thereof by the landlord (Foggitt et al., Citation2019). This exemplifies the socio-spatial configurations in the sphere of the house, whereby access to the built infrastructure relies on social hierarchies (landlordism, landlord-tenant relationship, and service provider).

3.3.2. Social and cultural

Gendered roles play a significant role in the intersection of exclusion from WASH facilities and housing. Wiltgen Georgi et al. (Citation2021) describe how in the context of South Africa gender norms and roles hamper toilet access in various ways. Reproductive roles (childcare), productive roles (informal work), community roles (voluntary maintenance of community facilities), and biological and cultural processes (menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth and menopause) (Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021) exacerbate inequalities regarding WASH.

In the South Asian context, women typically bear the responsibility of domestic WASH work (Ashraf et al., Citation2022; Biswas, Citation2020). Where street taps are the dominant source of water, supply is not always continuous depending on the water source. In cases where households frequently rely on communal facilities such as street taps, women engage in negotiating tactics that can be both positive (information sharing) and negative (conflict). Conflicts may arise from queueing issues or exceeding permitted water consumption limits, between women or between groups of women and linemen. In periods of scarcity, women from worse-off localities search for better WASH options within or outside their settlement, leading to conflicts (Biswas, Citation2020). This is fuelled by stigmas and biases on certain social groups and localities within the settlement. In such scenarios, individuals tend to safeguard the limited accessible sources, such as those that are regularly cleaned or conveniently located (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Panchang, Citation2021). This even extends beyond the settlement's boundary, whereby exclusion is rooted in xenophobic sentiments directed at migrant slum residents from different national backgrounds or a minority ethnic background (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021). This leads to further exclusion of people based not only on gender (men vs. women, women vs. women) but also on larger social dynamics, such as locality (location of house) and nationality. In a study on toilet adoption patterns in Bolivia, intra-household women may have no or less decision-power compared to their male partners (machismo) when it comes to adopting a specific toilet system (Helgegren et al., Citation2018).

Safety is a factor that affects especially women regarding WASH access (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019). They experience harassment from passers-by, male community members and the police (Butcher, Citation2021; Corburn & Karanja, Citation2014). The lack of police support influences women’s perceptions of safety and thus access to public toilet facilities (Corburn & Karanja, Citation2014). The safety factor extends to the perception of caretakers of children and the safety of public toilets (Foggitt et al., Citation2019). Concerning water access, water-deprived households experience emotional distress, including feelings of fear regarding contamination, discomfort, concerns about arbitrary price changes, and anxiety (Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020).

Regarding menstruation, many stigmas exist because of limited knowledge and awareness of menstruation and MHM (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019). The lack of knowledge also stretches to the use of menstruation products. Lack of knowledge and awareness impacts the use of products and services (type of product and frequency of changing, not understanding how to maintain hygiene during menstruation, understating symptoms, not knowing when to access healthcare) (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019).

In exploring evidence on the social and cultural facets of WASH and housing, the literature exemplifies that sociocultural norms surrounding WASH (such as hygiene, discretion, and dignity) impact toilet access (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019). Cultural norms and religious beliefs influence community attitudes and actions regarding water, sanitation, and hygiene practices. The distance between the house and the toilet facility is influenced by cultural factors and reinforces stigmas of uncleanliness when built too close to the house (Panchang, Citation2021). Religion can also serve as a justification for not constructing a household toilet (Nagpal et al., Citation2021).

3.3.3. Socio-economic

When households cannot afford private household toilets (Sahoo et al., Citation2015), they often rely on public toilets which further economically burdens them in the long term (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Das & Crowley, Citation2018; Vu et al., Citation2022). The cost of each toilet use (pay-per-use) hampers people from using them (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015). Factors such as the number of children within a household and the number of breadwinners may exclude people even further (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). This is especially because slum dwellers have irregular cash flows (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). Given that women frequently assume caregiving roles, they experience an additional burden. This is also the case for women and access to menstrual health products, whereby limited financial resources influence MHM (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019; Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Nowreen et al., Citation2022). In India, Ashraf et al. (Citation2022) illustrate how family hierarchies impede women’s participation in financial decision-making, making it a gendered affair. According to Ashraf et al. (Citation2022), the extent of decision-making concerning sanitation is shaped by a woman's age and her social role within the family.

Moreover, adequate housing requires adequate income. This includes not only the infrastructure cost of housing but also the availability of basic services (Sheuya et al., Citation2007). The affordability of housing frequently drives households to opt for residing in slum settlements. For slum dwellers, this becomes a vicious cycle, where a lack of funds prevents individuals from accessing adequate houses with reliable water connections and toilets. This leads them to rely on public facilities which come with a cost for each use.

3.3.4. Governance and policy

The reviewed studies reveal various factors associated with public, private, and philanthropic entities and their contribution to slum dwellers’ exclusion and barriers to adequate housing and WASH facilities. Inadequate provision and maintenance (Rashid, Citation2009) of WASH facilities, or no service provision by the responsible authorities (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015) have been mentioned as barriers to access. This situation is exacerbated by private, informal or illegal vendors who assume the role of service providers in the absence of the government and operate unchecked (Rashid, Citation2009; Subbaraman et al., Citation2015).

Moreover, the studies mention that uncertain land tenure (Ali & Stevens, Citation2009; Rashid, Citation2009; Vu et al., Citation2022), slum rehabilitation plans (Panchang, Citation2021) and slum upgrading initiatives greatly impact slum dwellers’ sense of security and thus their ability to invest in WASH facilities. Ambiguity on who can legally claim their house and the fear of eviction influence households’ uptake of toilets (Panchang, Citation2021). Amidst slum eviction risks in Bangladesh, Rashid (Citation2009) mentions that evictions also threaten operations by NGOs with infrastructure projects, as they risk a loss of capital investment. Moreover, other studies mentioned the lack of consideration for slum populations in urban planning and policies – such as within slum upgrading – as a barrier to housing and WASH access (Sheuya et al., Citation2007; Singh, Citation2022). Slum dwellers at large are excluded from planning and design processes (Biswas, Citation2020). Rashid (Citation2009) also mentions a lack of political will to rehabilitate the urban poor. Efforts to formalise housing and WASH access through policies can inadvertently worsen exclusion for those who were already marginalised (Rodina & Harris, Citation2016) or in cases of deliberate slum clearance (Muchadenyika, Citation2015). According to Uddin (Citation2018), a lack of policies addressing the specific needs of informal settlements is evident. Hence the political exclusion of slum dwellers serves as a barrier to WASH access (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015). Political exclusion regarding water access also exists based on party politics and short-term election priorities (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015).

Another factor mentioned is the failure of various toilet systems to align with user needs (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the competing approaches of NGOs and charities also serve as a barrier to access (Baruah, Citation2007). Additionally, directing attention towards effective accountability mechanisms (such as monitoring) is considered crucial for funding organisations aiming to assist the most impoverished, rather than merely increasing the availability of funds (within the context of NGO-funder relationships) (Baruah, Citation2007). Regarding NGOs, Baruah (Citation2007) also states that a limited understanding of the significance of proper housing and housing infrastructure in enhancing the overall well-being of low-income households, inadequate funding and a lack of technical expertise also hamper their involvement in the housing sphere.

3.3.5. Environmental

External macro factors concerning the environment have also been identified as barriers. The diversion of water from the slums by the authorities due to scarcity in the system is mentioned as a barrier to access (Singh, Citation2022). This is an example of socio-spatial configurations and how this may come at the expense of slum dwellers. Moreover, weather-seasonality impacts the WASH system at large and thus access (Adams et al., Citation2022; Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019; Uddin, Citation2018), especially when coupled with a lack of infrastructure (Rashid, Citation2009). Scarcity based on seasonality may thus also lead to conflicts at public water taps, mainly experienced by women fetching water (Biswas, Citation2020). Climate change also influences water quality and availability (Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020). In relation to that, the location of slums – often hazardous areas – coupled with climate change (Sheuya et al., Citation2007) serves as a barrrier. The spread of waterborne, vector-borne diseases, and pandemics due to climate change is evident (Nowreen et al., Citation2022).

3.4. Consequences of access barriers to WASH and housing

The following section highlights the main consequences of denied access mentioned in the included studies. The evidence on consequences is based on N = 28 studies.

3.4.1. Compromised health

The consequences of barriers to WASH and housing are fundamentally rooted in the direct relationship with health. Housing without access to WASH services can significantly hinder health outcomes and well-being. A substantial number of the papers highlight that inadequate housing, characterised by the absence of basic WASH services, poses significant barriers to achieving optimal health outcomes (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015; Corburn & Karanja, Citation2014; Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020; Okurut et al., Citation2015; Panchang, Citation2021; Sheuya et al., Citation2007; Subbaraman et al., Citation2015). In the reviewed studies, denied access to adequate housing and WASH services primarily results in compromised health. Lack of private toilets (Peprah et al., Citation2015) in the house or non-use of private or shared toilets leads to public toilet usage, OD or flying toilets, the latter referring to the use of plastic bags for the collecting human faeces that are subsequently thrown in the open (Das & Crowley, Citation2018; Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Kwiringira et al., Citation2014; Okurut et al., Citation2015; Peprah et al., Citation2015; Vu et al., Citation2022). The lack of piped water leads to reverting to open springs that are contaminated by pit latrines, exemplifying the interrelation between the latrines, the polluted environment and contaminated water (Richmond et al., Citation2018). OD and flying toilets also pollute the environment, causing diseases and health risks for the public. This disproportionately affects older adults, people with disabilities, and children, who have fewer sanitation options or are restricted. Restrictions may occur from inconvenient locations of latrines, and accessibility barriers such as steep inclines or stairs, potentially leading to OD or the use of flying toilets (Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Peprah et al., Citation2015). Women and girls experience stress and deteriorated health due to avoidance behaviour of not being able to use toilets at nighttime (Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Kwiringira et al., Citation2014; Nagpal et al., Citation2021; Rashid, Citation2009; Vu et al., Citation2022; Vu et al., Citation2022). This is aggravated during menstruation (Nagpal et al., Citation2021). Children face childhood diarrheal diseases, malnutrition and food contamination due to inadequate sanitation and water leading to sickness (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015; Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020). Inadequate housing that lacks access to clean water and sanitation facilities poses a significant health risk, particularly to children who may suffer from potentially life-threatening diarrhoea, especially those under the age of five (Singh et al., Citation2022). Moreover, poor quality housing and neighbourhoods lead to health problems, including respiratory diseases, malnutrition, and mental health issues (Sheuya et al., Citation2007). Improper management of human waste also leads to the spread of viral and communicable diseases within slum areas due to human waste in water bodies (Uddin, Citation2018).

3.4.2. Socio-economic burden

Water and sanitation services are too expensive, especially for the urban poor (Ali & Stevens, Citation2009), thus people are unable to buy a private toilet (Nagpal et al., Citation2021) or pay-per-use toilets (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015). Failure in water service delivery and thus compromised access has a range of negative impacts on various aspects of life, including household economy, employment opportunities, education, quality of life, social cohesion, and people's sense of political inclusion (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015). Moreover, household budgets are compromised, and time spent caring for sick family members due to contaminated water puts financial constraints on households (Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Nagpal et al., Citation2021; Rashid, Citation2009; Subbaraman et al., Citation2015), as well as increased medical costs (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015). This is gendered as women take care of the sick and miss wages (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015). In terms of housing, sometimes families receive adequate housing with access to public utilities as part of government resettlement projects. However, cash-deprived families opt to sell their land/housing to others and move to other slum settlements to have extra income, illustrating the intricate interplay between the socio-economic situation of households and the need for cash (Rashid, Citation2009). Moreover, households resort to cheaper and more portable materials for housing (Muchadenyika, Citation2015).

3.4.3. Adverse social impacts

In the reviewed studies, social impacts are mostly related to gender – women and girls – whereby inadequate access to sanitation, leads to school absenteeism for girls, indignity and violence, increased anxiety, a sense of powerlessness and hopelessness, marginalisation, and stigmatisation (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015). MHM is frequently associated with gendered perceptions of hygiene (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019; Nowreen et al., Citation2022). Thus, the majority of the studies on MHM, mention that the lack of WASH facilities has negative impacts on MHM of women and girls. Moreover, Sahoo et al. (Citation2015) found that women and girls face environmental, sexual and social stressors during sanitation practices that take place in the public sphere. The conflicts experienced depended on a woman and/or girl's life stage (Sahoo et al., Citation2015). In other cases, women experienced Gender-Based-Violence (GBV) during public toilet use during the day or time or OD (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021) and other psychosocial stressors (Vu et al., Citation2022) leading to further stigmatisation (Corburn & Karanja, Citation2014).

3.4.4. Navigating WASH mobility

The barriers to housing and WASH facilities and services are multifaceted and complex, and so are the consequences thereof. The consequences of denied WASH access are not confined to a binary ‘access’ or ‘no access’ dichotomy (Foggitt et al., Citation2019) and the complexity similarly applies to toilet construction which cannot simply be answered by ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (Panchang, Citation2021). Several studies report on the difficulties experienced in navigating water and sanitation (Biswas, Citation2020; Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Winter et al., Citation2019). This is especially felt among women, who are commonly in charge of domestic (WASH) chores including childcare coupled with fulfilling economic roles (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). This places psychological stress on women due to the emotional burden of day-to-day planning and decision-making (Adams et al., Citation2022). Access is not predictable and is navigated or ‘improvised’ spatially over time (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Foggitt et al., Citation2019; Panchang, Citation2021).

3.5. Policy and intervention recommendations

The recommendations derived from the selected studies highlight the imperative for inclusive and holistic approaches, policies and interventions in the realm of informal settlements and access to adequate housing and/or WASH services (Chakravarthy et al., Citation2019; Kangmennaang et al., Citation2020; Muchadenyika, Citation2015; Singh, Citation2022; Uddin, Citation2018; Winter et al., Citation2019). Several policy and intervention recommendations outlined in the studies are specifically aimed at addressing gender-related issues in WASH and housing. These recommendations aim to ensure equitable access and opportunities for women and girls, with and without disabilities. Suggestions include gender-sensitive policies (Panchang, Citation2021) and inclusive planning for improved WASH and MHM, education for disabled girls, empowerment measures, and housing priority (Nowreen et al., Citation2022).

The recommendations emphasise the necessity of collaborative efforts of actors involving residents, NGOs, governments, and diverse stakeholders to alleviate urban inequalities and increase access to housing and WASH (Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015; Sheuya et al., Citation2007; Uddin, Citation2018). Recognising the interplay between basic services and living conditions, these interventions advocate for multidimensional metrics that extend beyond conventional health outcomes, considering the broader impact of access inequalities on quality of life (Subbaraman et al., Citation2015) as well as nuanced indicators that assess the quality of access, including toilet mobility and thus the agency of individual users and the extent to which structural factors facilitate this could offer stronger incentives (Foggitt et al., Citation2019).

For interventions, studies mention the incorporation of social dimensions in health interventions (Sheuya et al., Citation2007), maintenance, disabled-friendly facilities, affordable menstrual hygiene options, and enhanced school support for girls (Nowreen et al., Citation2022), recognising the role of toilet facilities in influencing overall quality of life, rather than focusing solely on biomedical outcomes (Panchang, Citation2021), and small-scale infrastructure measures by the government, such as incremental approaches, or larger-scale initiatives, like providing complete housing units (Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of evidence

The review’s analysis of the studies addressing access inequalities to the coupling of housing and WASH reveals a research gap on social identities and access inequalities in informal settlements, underscoring the need for further exploration in this domain (Mukherjee et al., Citation2020; Rigon, Citation2022). Women and girls are disproportionately impacted by the consequences of inadequate access to water, sanitation, and housing, resulting in gendered disparities. The majority of the included papers focus on women and/or girls – at times intersecting with other social identities such as disabilities (Nowreen et al., Citation2022) – and access to WASH. The papers include factors impeding women and girls from having adequate WASH access (including MHM), evidence on how women and girls are impacted by poor water and sanitation access and how, as a result, they navigate WASH access. The gendered consequences of WASH insecurity have been emphasised explicitly before (O'Reilly & Dreibelbis, Citation2018). This review contributes by highlighting the evidence of how WASH and housing intersect to create these access inequalities. It is therefore important to focus on intra-household inequalities in access to basic services since access differs per member of the household (Wutich, Citation2009). Beyond the physical infrastructure, the connection between housing and WASH extends to the broader neighbourhood dynamics, social interactions, and the psychosocial dimensions, the latter including aspects of security, control, sense of attachment, permanence, and continuity (Sheuya et al., Citation2007). In terms of intra – and inter-slum dynamics, access inequalities can also occur on the basis of ethnicity and nationality (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021), resulting in social exclusion based on cultural and/or social identity (Mukherjee et al., Citation2020). The findings exemplified how both WASH and housing in slums are intertwined with socioeconomic status – reason for living in slums, incremental housing, purchasing WASH products and services – and social and cultural elements – the role of women and girls in WASH and homemaking. This evidence has also shown how the right to adequate housing, including access to services such as WASH (UN-Habitat, Citation2009), is not solely a matter concerning the provision of sufficient infrastructure. As access to WASH and housing is part of larger poverty-related issues (McGranahan, Citation2013), people will negotiate access based on their financial circumstances at that moment.

Moreover, in the included studies, not all aspects of hygiene are emphasised although it is an integral aspect of WASH. According to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP), hygiene consists of handwashing, food hygiene and MHM (JMP, Citationn.d.). Handwashing with soap after toilet use is important and considered a crucial public health behaviour, as it diminishes exposure to harmful faecal pathogens (Wolf et al., Citation2019). Clean water and handwashing are viewed as the most cost-effective intervention for preventing diarrheal diseases and it has been widely acknowledged that handwashing and basic hygiene can prevent diarrhoea (Langford et al., Citation2011). Several studies, especially the ones discussing gender, do emphasise menstrual hygiene management (Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Nowreen et al., Citation2022). However, there is a lack of emphasis on handwashing with soap and food hygiene.

Furthermore, emphasis on individual private household facilities which are not shared with other households may perpetuate access inequalities on a collective scale – especially in dense areas. At the collective level, shared toilets prevent people from defecating in the open (Singh, Citation2022). In the JMP ladder, toilets shared by two or more households are categorised as ‘limited sanitation’. Other scholars have also advocated that under certain conditions, shared sanitation should move to the next level on the sanitation ladder to be counted as ‘basic sanitation’ (Mara, Citation2016). We aim to contribute to this body of literature by bringing in the argument of access inequalities. To exemplify, a woman might be better off utilising another household’s toilet (on the condition that the toilet is cleaned and maintained sufficiently) than strategizing toilet usage daily for herself and her family (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). In line with that, Hawkins et al. (Citation2013) have argued that shared facilities, designated for small, self-selected groups are more desirable than communal facilities as they foster a sense of ownership that motivates users to maintain cleanliness.

Besides, access is often defined as per JMP standards (the presence of a facility that is improved or safely managed) – but does not go beyond to address factors such as proper use, cleaning and maintenance (Kwiringira et al., Citation2014) or cost (Panchang, Citation2021; Rashid, Citation2009; Vu et al., Citation2022).

Moreover, the evidence exemplified that slum dwellers still experience a lack of access to WASH – coupled with housing – despite the availability of (albeit inadequate) infrastructures, due to natural and physical barriers (Adams et al., Citation2022; Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Sahoo et al., Citation2015), identity-based factors (Chowdhury et al., Citation2022; Nowreen et al., Citation2022), socio-economic factors (Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Corburn & Hildebrand, Citation2015), or existing social and cultural fabrics (Biswas, Citation2020; Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Wiltgen Georgi et al., Citation2021). This highlights the importance of going beyond a merely quantitative approach to understanding the social dynamics at play when it comes to access inequalities (Nastar et al., Citation2019). Additionally, recognising the social dynamics that often underlie access inequalities, extending beyond mere infrastructure availability, this paper advocates for a shift away from primarily technical approaches to WASH (O'Reilly & Dreibelbis, Citation2018), while also emphasising infrastructure quality in terms of cleanliness and maintenance (Kwiringira et al., Citation2014). The latter has been associated with higher use of sanitation facilities (Garn et al., Citation2017).

On housing specifically, the included studies often focused on the tenure status of slum residents and/or households or on the land tenure of the settlement as a whole in relation to the city (Butcher, Citation2021; Cherunya et al., Citation2020; Rashid, Citation2009; Richmond et al., Citation2018; Singh, Citation2022; Vu et al., Citation2022). The findings emphasise the importance of a more elaborate understanding of the intricate interplay between the two domains of WASH and housing, to develop comprehensive trans-sectoral strategies for addressing access inequalities to WASH and housing in slums (McGranahan, Citation2013). Moreover, complex and multi-sectoral approaches are advocated for health planning in informal settlements based on the local knowledge of the residents, considering the interplay between various services and living conditions (Corburn & Karanja, Citation2014).

In response to the current situation in slums and the projections for 2050, governments, and local and international stakeholders are working to improve living conditions through various interventions. While the ‘bulldozer’ approaches of slum demolition and large-scale evictions are still present in many places, alternative approaches such as in-situ and participatory slum upgrading are increasingly considered. However, these do not guarantee success: while systematic reviews on slum upgrading interventions show positive yet limited outcomes with regard to health (communicable diseases) and quality of life (Henson et al., Citation2020; Turley et al., Citation2013), literature also warns us to be cautious e.g. of unintended health and environmental effects (Henson et al., Citation2020); long-term effects and sustainability of interventions (e.g. repair and maintenance, affordability, gentrification) (Doe et al., Citation2020; Turley et al., Citation2013); the lack of attention to diversity and intersectional inequalities within slums (Rigon, Citation2022; Yeboah et al., Citation2021); and overall the highly contextualised, politicised and diverse nature of interventions and effects (Doe et al., Citation2020; Henson et al., Citation2020; Muchadenyika, Citation2015; Rigon, Citation2022; Yeboah et al., Citation2021).

The studies in this review advocate for holistic, community-led, and sustainability-driven approaches for achieving city-wide sustainability in slum upgrading (Muchadenyika, Citation2015) and housing policies that address historical patterns of exclusion by engaging with communities (Rodina & Harris, Citation2016). While our review did not focus on slum upgrading as an intervention specifically, it does show the need to take seriously the varying aspirations (e.g. concerning housing) among slum dwellers based on social identities, and the importance of diversity in participation amongst slum dwellers regarding slum upgrading policies and interventions (see also Rigon, Citation2022).

4.2. Limitations

The exclusion of non-English studies led to limited papers on the Latin American and Francophone Sub-Saharan African context. Moreover, the focus on solely Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia may have also excluded critical literature on other parts of Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and the Middle East that may have been relevant to this review. Moreover, the time scope may have excluded relevant literature before the year 2000. Additionally, the coupling of WASH and housing may have excluded literature on inequalities and social exclusion solely related to WASH or housing. Finally, while literature addressing urban housing, slums, and informal settlements may not explicitly include keywords related to social identity or intersectional inequalities, they may implicitly engage with these issues. Despite the limitations, the comprehensive search strategy yielded relevant literature on the subject matter explored and it is anticipated that a reasonable level of saturation has been achieved.

5. Conclusions

The existing evidence on the interconnection of WASH and housing varies, ranging from the tenure status of the settlement (the availability of basic services), the tenancy agreements between landlords and tenants (access permittance by landlords), tenancy (as opposed to ownership of the house), the quality of physical infrastructures and the proximity of the house to public taps and toilets, and lastly, the interconnection on social fronts (the home as the locus of domestic spaces and economic activities and its relation to water and toilet access). Barriers to housing and WASH focused mostly on infrastructural, social and cultural, socio-economic, governance & policy, and environmental-related factors. The evidence focused largely on women and girls, predominantly related to gender norms in WASH.

The consequences of barriers to WASH and housing drive slum dwellers to seek solutions for securing themselves with access to WASH spatially and over time. Denied access is not binary (Cherunya et al., Citation2020). Rather a WASH journey continuum where people find solutions (e.g. using neighbours’ toilets, reverting to other CBT/public toilets or public taps). Navigating WASH mobility is highly dependent on someone’s social identity (within the household, community and city), their housing situation (type of house, its location in the settlement, tenancy/ownership) and the type of settlement they live in.

The findings of this review underpin the need for an intersectional approach to understanding access inequalities to WASH and housing in slums that – includes and – goes beyond gender and incorporates social identity factors such as ethnicity, religion, socio-economic status and gender (Mukherjee et al., Citation2020). A greater understanding is needed of different social identities in slums – how they intersect and create multiple forms of inequalities – and how they experience access (and the lack thereof) to WASH and housing. Moreover, holistic slum interventions that advocate for working with multiple stakeholders, including slum dwellers, need to consider the internal diversity that exists amongst slum dwellers and the resulting access inequalities. This is to avoid that slum interventions create losers, in addition to winners (Rigon, Citation2022). The complex nature of WASH accessibility connects with numerous domains, presenting a multifaceted challenge. This review aimed to approach access to WASH more holistically. It highlighted the intersection of WASH and housing to showcase inequalities in access experienced by slum dwellers, which disproportionately manifest based on their various social identities. A deeper understanding of the relationship between WASH and different domains may facilitate the development of innovative strategies for achieving universal water supply and sanitation provisions among the diverse urban poor populations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.6 KB)Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the important contributions of the reviewers who screened the records. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers and the Editor for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Barriers and their subsequent consequences are not mutually exclusive. Thus, in some cases, a single factor can act as both a barrier and a consequence depending on the studied context.

References

- Adams, E. A., Byrns, S., Kumwenda, S., Quilliam, R., Mkandawire, T., & Price, H. (2022). Water journeys: Household water insecurity, health risks, and embodiment in slums and informal settlements. Social Science & Medicine, 313, 115394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115394

- Akatch, S. O., & Kasuku, S. O. (2002). Informal settlements and the role of infrastructure: The case of Kibera, Kenya. Discovery and Innovation, 14(1), 32–37.

- Ali, M., & Stevens, L. (2009). Integrated approaches to promoting sanitation: A case study of Faridpur, Bangladesh. Desalination, 248(1-3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.030

- Amegah, A. K. (2021). Slum decay in Sub-saharan Africa. Environmental Epidemiology, 5(3), e158. https://doi.org/10.1097/EE9.0000000000000158

- Anand, A., & Phuleria, H. C. (2022). Assessment of indoor air quality and housing, household and health characteristics in densely populated urban slums. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 24(10), 11929–11952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01923-x

- Ashraf, S., Kuang, J., Das, U., Shpenev, A., Thulin, E., & Bicchieri, C. (2022). Social beliefs and women’s role in sanitation decision making in Bihar, India: An exploratory mixed method study. PLoS One, 17(1), e0262643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262643

- Auerbach, A. M., & Thachil, T. (2023). Migrants and machine politics: How India's urban poor seek representation and responsiveness. Princeton University Press.

- Banerjee, A., & Chattopadhyay, B. (2020). Inequalities in access to water and sanitation: A case of slums in selected states of India. In R. Singh, B. Srinagesh, & S. Anand (Eds.), Urban health risk and resilience in Asian cities. Advances in geographical and environmental sciences (pp. 57–72). Springer.

- Baruah, B. (2007). Assessment of public–private–NGO partnerships: Water and sanitation services in slums. Natural Resources Forum, 31(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2007.00153.x

- Biswas, D. (2020). Navigating the city’s waterscape: Gendering everyday dynamics of water access from multiple sources. Development in Practice, 31(2), 248–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1836128

- Brelsford, C., Lobo, J., Hand, J., & Bettencourt, L. M. (2017). Heterogeneity and scale of sustainable development in cities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(34), 8963–8968. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1606033114

- Butcher, S. (2021). Differentiated citizenship: The everyday politics of the urban poor in Kathmandu, Nepal. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 45(6), 948–963. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.13003

- Carvalho, D. M., & Van Tulder, R. (2022). Water and sanitation as a wicked governance problem in Brazil: An institutional approach. Frontiers in Water, 4, 781638. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2022.781638

- Chakravarthy, V., Rajagopal, S., & Joshi, B. (2019). Does menstrual hygiene management in urban slums need a different lens? Challenges faced by women and girls in Jaipur and Delhi. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 26(1-2), 138–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521518811174

- Chant, S. (2013). Cities through a “gender lens”: A golden “urban age” for women in the global South? Environment and Urbanization, 25(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477809

- Checkley, W., Pollard, S. L., Siddharthan, T., Babu, G. R., Thakur, M., Miele, C. H., & Van Schayck, O. C. P. (2016). Managing threats to respiratory health in urban slums. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 4(11), 852–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30245-4

- Cherunya, P. C., Ahlborg, H., & Truffer, B. (2020). Anchoring innovations in oscillating domestic spaces: Why sanitation service offerings fail in informal settlements. Research Policy, 49(1), 103841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103841

- Chowdhury, M. A., Nowreen, S., Tarin, N. J., Hasan, M. R., Zzaman, R. U., & Amatullah, N. I. (2022). WASH and MHM experiences of disabled females living in Dhaka slums of Bangladesh. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(10), 683–697. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2022.060

- Cities Alliance. (n.d.). Slums and slum upgrading. What are Slums? https://www.citiesalliance.org/themes/slums-and-slum-upgrading

- Corburn, J., & Hildebrand, C. (2015). Slum sanitation and the social determinants of women’s health in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2015, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/209505

- Corburn, J., & Karanja, I. (2014). Informal settlements and a relational view of health in Nairobi, Kenya: Sanitation, gender and dignity. Health Promotion International, 31(2), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dau100

- Das, P., & Crowley, J. (2018). Sanitation for all: A Panglossian perspective? Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 8(4), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2018.011

- Doe, B., Peprah, C., & Chidziwisano, J. R. (2020). Sustainability of slum upgrading interventions: Perception of low-income households in Malawi and Ghana. Cities, 107, 102946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102946

- Foggitt, E., Cawood, S., Evans, B., & Acheampong, P. (2019). Experiences of shared sanitation – towards a better understanding of access, exclusion and ‘toilet mobility’ in low-income urban areas. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 9(3), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2019.025

- Garn, J. V., Sclar, G. D., Freeman, M. C., Penakalapati, G., Alexander, K. T., Brooks, P., Rehfuess, E. A., Boisson, S., Medlicott, K. O., & Clasen, T. F. (2017). The impact of sanitation interventions on latrine coverage and latrine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 220(2 Part B), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.10.001

- Gulyani, S., Talukdar, D., & Jack, D. (2010). Poverty, living conditions, and infrastructure access: A comparison of slums in Dakar, Johannesburg, and Nairobi. (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5388). The World Bank. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1650479

- Hawkins, P., Blackett, I., & Heymans, C. (2013). Poor-Inclusive Urban Sanitation: An Overview. (Water and Sanitation Program Study No. 80347). The World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/17385

- Helgegren, I., Rauch, S., Cossio, C., Landaeta, G., & McConville, J. (2018). Importance of triggers and veto-barriers for the implementation of sanitation in informal peri-urban settlements – The case of Cochabamba, Bolivia. PLoS One, 13(4), e0193613. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193613

- Henson, R. M., Ortigoza, A., Martinez-Folgar, K., Baeza, F., Caiaffa, W., Vives Vergara, A., Diez Roux, A.V., Lovasi, G. (2020). Evaluating the health effects of place-based slum upgrading physical environment interventions: A systematic review (2012–2018). Social Science & Medicine, 261, 113102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113102

- Joint Monitoring Programme [JMP]. (n.d.). Hygiene. https://washdata.org/monitoring/hygiene

- Joshi, N., Gerlak, A. K., Hannah, C., Lopus, S., Krell, N., & Evans, T. (2023). Water insecurity, housing tenure, and the role of informal water services in Nairobi’s slum settlements. World Development, 164, 106165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106165

- Kangmennaang, J., Bisung, E., & Elliott, S. J. (2020). ‘‘We Are drinking diseases’: Perception of water insecurity and emotional distress in urban slums in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030890

- Khan, S. S., Te Lintelo, D., & Macgregor, H. (2023). Framing ‘slums’: Global policy discourses and urban inequalities. Environment and Urbanization, 35(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/09562478221150210

- Kwiringira, J., Atekyereza, P., Niwagaba, C., & Günther, I. (2014). A review of life expectancy and infant mortality estimations for Australian Aboriginal people. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1

- Langford, R., Lunn, P., & Panter-Brick, C. (2011). Hand-washing, subclinical infections, and growth: A longitudinal evaluation of an intervention in Nepali slums. American Journal of Human Biology, 23(5), 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.21189

- Lucci, P., Bhatkal, T., Khan, A., & Berliner, T. (2015). What works in improving the living conditions of slum dwellers. A review of the evidence across four programmes. (Dimension Paper, 4). Overseas Development Institute. https://www.cib-uclg.org/sites/default/files/odi-what_works_in_improving_the_living_conditions_of_slum_dwellers.pdf

- Mara, D. (2016). Shared sanitation: To include or to exclude? Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 110(5), 265–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trw029

- McGranahan, G. (2013). Community-driven sanitation improvement in deprived urban neighbourhoods: Meeting the challenges of local collective action, co-production, affordability and a trans-sectoral approach. (SHARE research report). London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.01236350

- Muchadenyika, D. (2015). Slum upgrading and inclusive municipal governance in Harare, Zimbabwe: New perspectives for the urban poor. Habitat International, 48, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.03.003

- Mukherjee, S., Sundberg, T., & Schütt, B. (2020). Assessment of water security in socially excluded areas in Kolkata, India: An approach focusing on water, sanitation and hygiene. Water, 12(3), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12030746

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Evaluating screening approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of HCV related cirrhosis patients from the Veteran’s Affairs Health Care System. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0458-6

- Nagpal, A., Hassan, M., Siddiqui, M. A., Tajdar, A., Hashim, M., Singh, A., & Gaur, S. (2021). Missing basics: A study on sanitation and women’s health in urban slums in Lucknow, India. GeoJournal, 86(2), 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-019-10088-0

- Nakamura, S. (2016). Revealing invisible rules in slums: The nexus between perceived tenure security and housing investment. Habitat International, 53, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.029

- Nastar, M., Isoke, J., Kulabako, R., & Silvestri, G. (2019). A case for urban liveability from below: Exploring the politics of water and land access for greater liveability in Kampala, Uganda. Local Environment, 24(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1572728

- Nowreen, S., Chowdhury, M. A., Tarin, N. J., Hasan, M. R., & Zzaman, R. U. (2022). A participatory SWOT analysis on water, sanitation, and hygiene management of disabled females in Dhaka slums of Bangladesh. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 12(7), 542–554. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2022.061

- Nyametso, J. K. (2012). The link between land tenure security, access to housing, and improved living and environmental conditions: A study of three low-income settlements in Accra, Ghana. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 66(2), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2012.665079

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR]. (n.d.). OHCHR and the right to water and sanitation. About water and sanitation. https://www.ohchr.org/en/water-and-sanitation

- Okurut, K., Kulabako, R. N., Abbott, P., Adogo, J. M., Chenoweth, J., Pedley, S., Tsinda, A., & Charles, K. (2015). Access to improved sanitation facilities in low-income informal settlements of East African cities. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 5(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2014.029

- O'Reilly, K. (2016). From toilet insecurity to toilet security: Creating safe sanitation for women and girls. WIRES Water, 3(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1122

- O'Reilly, K., & Dreibelbis, R. (2018). WASH and gender: Understanding gendered consequences and impacts of WASH in/security. In O. Cumming, & T. Slaymaker (Eds.), Equality in water and sanitation services (pp. 80–93). Routledge.

- Panchang, S. V. (2021). Beyond toilet decisions: Tracing sanitation journeys among women in informal housing in India. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 124, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.011

- Peprah, D., Baker, K. K., Moe, C., Robb, K., Wellington, N. I. I., Yakubu, H., & Null, C. (2015). Public toilets and their customers in low-income Accra, Ghana. Environment and Urbanization, 27(2), 589–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247815595918

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), Jbi manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 407–452). JBI.

- Pommells, M., Schuster-Wallace, C., Watt, S., & Mulawa, Z. (2018). Gender violence as a water, sanitation, and hygiene risk: Uncovering violence against women and girls as it pertains to poor WASH access. Violence Against Women, 24(15), 1851–1862. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218754410

- Rakodi, C. (2015). Addressing gendered inequalities in access to land and housing. In C. Moser (Ed.), Gender, asset accumulation and just cities (pp. 81–99). Routledge.

- Rashid, S. F. (2009). Strategies to reduce exclusion among populations living in urban slum settlements in Bangladesh. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 27(4), 574. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3403

- Richmond, A., Myers, I., & Namuli, H. (2018). Urban informality and vulnerability: A case study in Kampala, Uganda. Urban Science, 2(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci2010022

- Rigon, A. (2022). Diversity, justice and slum upgrading: An intersectional approach to urban development. Habitat International, 130, 102691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102691

- Rodina, L., & Harris, L. (2016). Water services, lived citizenship, and notions of the state in marginalised urban spaces: The case of Khayelitsha, South Africa. Water Alternatives, 9(2), 336–355.

- Sahoo, K. C., Hulland, K. R., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Freeman, M. C., Panigrahi, P., & Dreibelbis, R. (2015). Sanitation-related psychosocial stress: A grounded theory study of women across the life-course in Odisha, India. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.031

- Sarkar, A. (2020). Everyday practices of poor urban women to access water: Lived realities from a Nairobi slum. African Studies, 79(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2020.1781594

- Saroj, S. K., Goli, S., Rana, M. J., & Choudhary, B. K. (2020). Availability, accessibility, and inequalities of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) services in Indian metro cities. Sustainable Cities and Society, 54, 101878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101878

- Sheuya, S., Howden-Chapman, P., & Patel, S. (2007). The design of housing and shelter programs: The social and environmental determinants of inequalities. Journal of Urban Health, 84(S1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-007-9177-3