ABSTRACT

Establishing a robust One Health (OH) governance is essential for ensuring effective coordination and collaboration among human, animal, and environmental health sectors to prevent and address complex health challenges like zoonoses or antimicrobial resistance. This study conducted a mixed-methods environmental scan to assess to what extent Mexico displays a OH governance and identify opportunities for improvement. Through documentary analysis, the study mapped OH national-level governance elements: infrastructure, multi-level regulations, leadership, multi-coordination mechanisms (MCMs), and financial and OH-trained human resources. Key informant interviews provided insights into enablers, barriers, and recommendations to enhance a OH governance. Findings reveal that Mexico has sector-specific governance elements: institutions, surveillance systems and laboratories, laws, and policies. However, the absence of a OH governmental body poses a challenge. Identified barriers include implementation challenges, non-harmonised legal frameworks, and limited intersectoral information exchange. Enablers include formal and ad hoc MCMs, OH-oriented policies, and educational initiatives. Like other middle-income countries in the region, institutionalising a OH governance in Mexico, may require a OH-specific framework and governing body, infrastructure rearrangements, and policy harmonisation. Strengthening coordination mechanisms, training OH professionals, and ensuring data-sharing surveillance systems are essential steps toward successful implementation, with adequate funding being a relevant factor.

Introduction

For a long time, the public health sector has focused predominantly on the direct effects of health threats on humans, without considering their underlying causes, prevention, and the impact of our actions on animal health and ecosystems. However, the recent COVID-19 pandemic, potentially attributed to human-wildlife interactions, has highlighted the need to take systemic perspectives to address the complex health challenges arising from population growth, animal-human interconnectedness, and environmental transformation (Destoumieux-Garzón et al., Citation2018; One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) et al., Citation2022). In particular, the One Health (OH) approach proposes an interdisciplinary and multisectoral collaboration to achieve optimal health for people, animals, and the environment. While this approach has been widely used to address zoonotic and infectious diseases, it is also vital for managing other intertwined complex health challenges, such as antimicrobial resistance (AMR), food safety, and environmental risks and hazards (One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) et al., Citation2022; Robbiati et al., Citation2023).

The prevention, preparedness, and response given to health challenges that cross the human-animal-environment interface have often been conducted in a vertical manner or in sectoral silos, offering an inadequate, slow, or unsynchronised response that compromises the health outcome itself (Mor, Citation2023; Nyatanyi et al., Citation2017; Zinsstag et al., Citation2005). Therefore, adopting a OH approach is crucial, particularly at the country level. This involves building a strong OH governance that ensures the necessary articulation mechanisms and engagement between relevant cross-sectoral institutions and stakeholders (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Nyatanyi et al., Citation2017). The One Health governance architecture encompasses coordination, collaboration, regular communication, and capacity building among public health, animal health, and environmental institutions. It also includes legal instruments, regulatory frameworks, existing capacities, knowledge resources, and economic and human resources (Elnaiem et al., Citation2023; FAO et al., Citation2019). The goal of such integration is to harness the strengths of each sector to achieve mutual, shared, and equitable benefits and to promote an efficient and sustainable response while avoiding duplication and lowering operational costs (Bhatia, Citation2021; Rasanathan et al., Citation2017; Ruckert et al., Citation2024). Ideally, it should also involve those relevant non-health sectors at local, national, regional, and global levels (see glossary definitions in Appendix i) (FAO et al., Citation2019).

Given the relevance of adopting governance with this approach to tackling complex diseases and health challenges at different levels, the recently formed Quadripartite AllianceFootnote1 has emphasised the importance of understanding its elements, progress, and practices in all countries (Asaaga et al., Citation2021; FAO et al., Citation2022; Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2021). Some high-income countries (HICs) have notably institutionalisedFootnote2 this concept, as demonstrated by Denmark´s creation of an institute to integrate preparedness and response capacities involving human and animal health (Benedetti et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, in low– and middle-income countries (LMICs) across regions like Africa or South Asia, there has been significant but variable progress on institutionalisation, mainly concerning the creation of OH frameworks and teams (McKenzie et al., Citation2016; Otu et al., Citation2021). Bangladesh, for example, has established a One Health strategic plan (McKenzie et al., Citation2016); in Kenya, a zoonotic disease unit has been set up to prevent zoonotic diseases better (Mbabu et al., Citation2014), while Rwanda, for example, has installed formal One Health strategic plans, multisectoral Multi-Coordination MechanismsFootnote3 and working groups around complex health challenges (Igihozo et al., Citation2022a). Additionally, in such countries, it has been reported that the implementation of governance elements has not been without difficulties due to tensions between institutions, power asymmetries, and non-harmonised frameworks, among others (Elnaiem et al., Citation2023; Lee & Brumme, Citation2013).

In Latin America, the OH principles are not new, as they can be traced to the indigenous peoples' deep-rooted understanding of the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health (Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2021). However, ironically, at present in the region, there is widespread unsustainable environmental exploitation and biodiversity loss (Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2022). This impact can mainly be attributed to the quest for development, political upheaval, and social, demographic, and economic disparities. Therefore, OH governance in these countries would seem adequate to prevent and counteract similarly experienced endemic and reemerging diseases, AMR, and other complex health challenges.

In regard to the application of the present form of the OH approach in Latin America, several educational and knowledge translation experiences or initiatives, particularly awareness projects and bottom-up collaborations, have been traced back to Chile, Brazil, and Colombia in the last decades (Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2021). In addition, OH academic networks like SAPUVET and OHLAIC have flourished in the last years, managing to bring together several countries and experts into discussing OH experiences. Other cross-sectoral mechanisms or academic exercises have been implemented in diverse countries in the region, for example, to address vector control, zoonoses, AMR, foodborne diseases, and ecosystem fragmentation, as evidenced by a survey on the implementation of the approach (Cediel Becerra et al., Citation2021). Rabies prevention is one of such examples, which has been seen through OH lenses, particularly in Brazil (Schneider et al., Citation2023), Colombia (Cediel-Becerra et al., Citation2023), and Mexico (González-Roldán et al., Citation2021). Also, one of the most well-known OH institutionalisation projects is the Colombian Integrated [Surveillance] Programme for Antimicrobial Resistance (COIPARS) (Donado-Godoy et al., Citation2015).

Nevertheless, the institutional adoption of the OH approach in the region remains generally limited due to a lack of commitment and resources, hindering its implementation (Cediel Becerra et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) has requested mapping the establishment of OH governance and its implementation at the national level with the intention of building OH capacity in the region (Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2021). Brazil has been among the first to undertake this effort (Wakimoto et al., Citation2022). However, many OH experiences and institutionalisation examples remain unpublished or unclassified as OH exercises. Mexico is one of those countries that has reported OH academic and cross-sectoral experiences (Cediel Becerra et al., Citation2021; Zenteno-Savin et al., Citation2017), potentially providing insights that can resonate with Latin America and other LMICs as they gradually transition towards OH governance.

Mexico, a middle-income country (MIC), has a centralised governance structure, a vast territory divided into 32 states, a large population, and wide socioeconomic disparities (INEGI, Citation2023). Therefore, organising the country to address health challenges can be demanding. Nevertheless, the country has previously demonstrated coordination and collaboration to address complex challenges such as epizootic outbreaks, including cattle screwworm, Venezuelan equine encephalitis, yellow fever, foot and mouth disease, and highly pathogenic avian influenza (Garza, Citation2010). Furthermore, in 2009, Mexico faced the H1N1 influenza virus pandemic and participated in international plans such as the North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI) with Canada and the United States (Martínez Coronado, Citation2016). This led to effective coordination, enabling a timely and transparent epidemiological identification and helped to prompt timely and transparent epidemiological identification that helped to alert the population (Cordova-Villalobos et al., Citation2017).

Following this event, the High-Level Tripartite Technical Meeting was held in Mexico in 2011 to foster effective inter-ministerial collaboration between the human, animal, environmental, and non-health health sectors (FAO et al., Citation2019). However, it is uncertain whether the concept has been successfully institutionalised. Therefore, the present study aims to (1) provide a first assessment of the status of the OH governance elements and (2) analyze the enablers, barriers, and recommendations in Mexico to institutionalise a successful OH governance.

Materials and methods

Study design

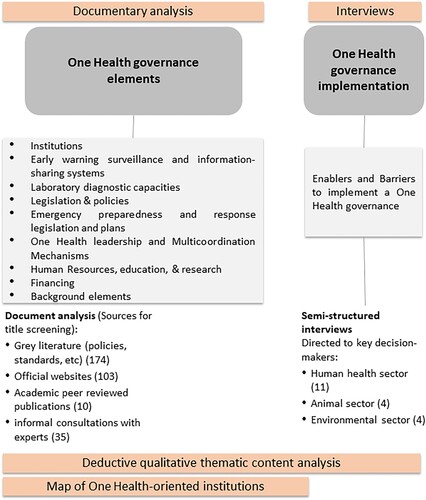

The present study was reviewed and approved (ID: #1671) by the National Institute of Public Health's Institutional Review Board (including an ethics review). It consisted of an environmental scan adapted from Wilburn et al. (Citation2016) (Supplementary Material A), a mixed-methods tool used to collect, organise, and analyze data as part of an international collaborative study exploring OH principles (governance and equity) in several countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ruckert et al., Citation2020b). In this paper, we focus on the country's pre-existing OH elements, as well as perceived enablers and barriers to the implementation of OH governance in Mexico. In the absence of an OH explicit governance framework at a national level (Ghai et al., Citation2022), we identified and adapted specific OH-oriented governance infrastructure elements from the Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Diseases in Countries (FAO et al., Citation2019). The environmental scan employed a documentary analysis and key informant semi-structured interviews with selected stakeholders (Methodological scheme in ). Deductive qualitative thematic content analysis of the documents and interviews (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, Citation2017) was conducted following an adapted theoretical coding tree to target OH governance in depth (see codebook definitions in Appendix ii).

The main OH-oriented governance elements at the national level were grouped in components as follows: a) infrastructure (institutions, early warning surveillance and information-sharing systems, laboratory diagnostic capacities), b) multi-level regulations and policies (legislation and policies, emergency preparedness and response legislation and plans of action), and c) OH leadership, MCMs, and human resources (OH-governing body, MCMs, human resources, education, and research). Financing was transversal to several elements.

Documentary analysis: Identifying One Health governance elements

The sequential process to identify documents concerning OH governance elements in Mexico included the following steps: i. search and collection of documents, ii. title screening and scanning of key elements, iii. selection of documents for full-text screening, and iv. thematic content analysis and synthesis. These are briefly described below (detailed information such as sources, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, and search periods can be found in Supplementary Material B). General inclusion criteria concerned a) content: fulfilling the codebook element description; b) document type: websites, grey documents (laws, programmes, policies, standards, agreements, decrees, reports, plans, guidelines, technical reports, etc.), and other documents derived from informal expert consultations, d) place and language: Information on Mexico in Spanish or English. Documents that did not satisfy the definition were eliminated.

The intentional search of documents was executed through differential strategies. Firstly, we identified OH-oriented infrastructure entities at national level out of the 19 national government ministries, known as Secretariats (Supplementary Material C); those included Secretariats and subunits responsible for human, animal, environmental or combined health matters. After this, we executed: 1) A deep review of the websites of each OH-oriented secretariat and subunit (s). Their main objective and mission, activities, news, and cited references were identified; additional sources referring to MCMs were identified through snowballing (Moser & Korstjens, Citation2018). 2) A hand-search in the Google browser using a specific combination of keywords, i.e. (((One Health governance element) AND (‘One Health’ OR zoonoses OR antimicrobial resistance OR environment)) AND Mexico). 3) Laws and standards were collected from official websites (Cámara de Diputados, Citation2021; Gobierno de México, Citationn.d.). 4) Additional resources (35 documents: websites, internal invitations, programmes, and academic publications) were identified based on informal consultations with experts (academics and national-level government officials with an understanding or working on topics related to the OH approach). 5) We also identified critical relevant academic peer-reviewed literature concerning background information on OH governance (including evidence of cross-sectoral collaboration to combat epizooties, zoonoses, or AMR matters in the country) through a pin-point search in Pubmed (MEDLINE): (‘One Health’ AND ‘Mexico’).

The documentary analysis was performed by AA, AAS, IR, AM, and JH, initially, from May 2020 to Dec 2020. However, informal consultations with experts and documents derived from it continued until June 2022. Three hundred and twenty-two sources were reviewed by title and scanned for essential details, including 192 grey literature documents, 116 websites, and 15 academic publications. All websites were reviewed thoroughly; the full text of 53 grey documents (Supplementary Material D) was also reviewed to perform thematic content analysis using the NVivo 12 software and Microsoft Word matrixes.

Data processing

The following was elaborated:

A map with OH-oriented institutions was schematised.

The information per OH governance element in the coding scheme was synthesised; these were classified per type of coordination (sector-specific, multisectoral, other).

MCMs per health threat (zoonotic and infectious diseases, AMR, food safety and security, and environmental and ecosystemic issues) were identified after the 2011 High-Level Technical Meeting to Address Health Risks at the Tripartite Interface in Mexico City (FAO et al., Citation2019). Adapted from the Abbas et al. framework (Abbas et al., Citation2022), these were cataloged according to their formality (formal, ad hoc, or informal) and according to their type (systems, commissions, committees, groups, agreements, programmes, policies, collaborations, event meetings, among others.).

A zoonoses and infectious diseases management and sanitary surveillance matrix was developed based on an existing framework (Asaaga et al., Citation2021) specifying the existence of standards and programmes in effect for the prevention and control of zoonoses in the country and its surveillance notification obligations in humans and animals. Specific stakeholders were identified.

Semi-structured interviews: Identifying enablers and barriers to build a One Health governance

Between October 2020 and April 2021, 19 semi-structured interviews were undertaken to identify perceived enablers and barriers to the potential implementation of a OH governance approach. Key informants were selected using purposive sampling by criteria: a) decision/policy makers, leading professionals, or second-in-command belonging or having worked at a human-animal-environment health government institution at a national level, b) working or having worked with OH complex challenges in academia, civil society organisations (CSOs), non-government organisations (NGOs) at national or regional level. Through the snowball approach, we included other actors.

Eleven actors worked in the human health sector (two of them in intersecting animal health topics and another two in non-health topics within that sector), four in the animal sector, and four in the environmental health sector (Supplementary Material E). Inquiries followed an interview guide with a priori-defined themes and orienting questions. ‘Recommendations’ came out as an emergent theme. Twelve interviewees had worked or were currently working in federal government units and subunits; the others currently worked in academia (5); eight people were from NGOs or CSOs. Seven informants had managerial/director positions, three had strategic jobs, one was an operational link, and six worked as researchers or consultants. Informants were invited by email, and all participants signed an online informed consent form. The interviews were conducted via telephone or Zoom, recorded (when the participant agreed), and fully transcribed. The name of the interviewees was not included in the transcript or notes. Deductive qualitative content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was performed using Microsoft Word matrixes to explore the enablers, barriers, and recommendations to build a OH governance infrastructure.

Results

One Health governance: Infrastructure and main stakeholders

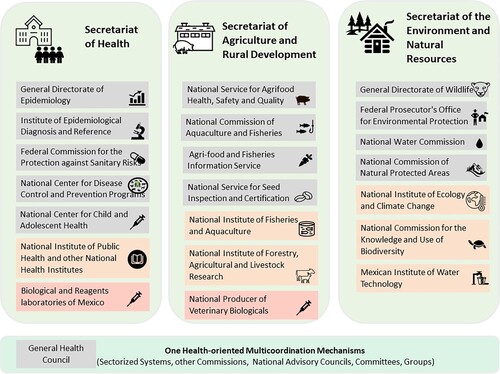

Institutions are one of the main infrastructure components of One Health governance. In Mexico, three Secretariats and their deconcentrated units play primary roles in human, animal, and environmental health: the Secretariat of Health or MoH, the Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development, and the Secretariat of the Environment and Natural Resources. OH-oriented institutions are depicted in , while their detailed responsibilities are listed under Appendix iii. In addition, identified decentralised research institutions build knowledge around selected topics such as public health, forestry, agriculture, climate change, and biodiversity. Parastatal entities also participate in human vaccine production/distribution and veterinary vaccine production.

Figure 2. One Health-oriented entities in the country.

Grey rectangles: Deconcentrated or subordinated government subunits; Orange rectangles: Decentralised subunits holding organic and technical autonomy from the central administration. Red rectangles: Parastatal entities. Notes: Undersecretariats and most directorates and centres are not detailed in the map, however their responsibilities are considered within the Secretariats´. Entities in charge of surveillance and information-sharing systems and laboratories are also part of the infrastructure, as shown in .

When analyzed per complex health challenge, such as the prevention and control of zoonoses, OH-oriented governance in Mexico is fragmented among different stakeholders. For instance, in the case of rabies, the National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Programmes (CENAPRECE), within the human health sector, oversees infectious disease control and zoonoses, the Secretariat of Agriculture oversees livestock immunisation, while the General Directorate of Wildlife reports affectations on wildlife. In the case of the control of taeniasis/cysticercosis, entities like the National Water Commission (CONAGUA) and food-safety subunits also must participate, making it difficult to articulate efforts. And, although non-health secretariats and subunits were not the main subjects of the study, Secretariats such as Education, Economy, External Affairs, and others should collaborate, when necessary, with the other OH-oriented Secretariats.

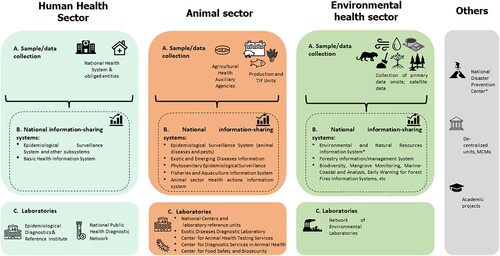

Regarding surveillance infrastructure, in the human sector, data on notifiable diseases at local, subnational, and national levels are collected by epidemiological information-sharing systems and subsystems () under the General Directorate of Epidemiology. The data is integrated with the central reference laboratory, the Institute of Epidemiological Diagnosis and Reference, and the State Laboratories for diagnostic capacities (see Appendix iii for detailed responsibilities and Surveillance items within the Supplementary Material F). In the animal sector, information about animal and plant diseases and pests is collected by different actors and is available through several service platforms. Various laboratories and reference centres across the country focus on exotic and endemic diseases in animals, as well as food-borne diseases and contaminants. Some of these laboratories have been designated as collaborating or reference centres by international organisations, such as the FAO´s Reference Centre for AMR. In addition, the National Environmental and Natural Resources Information System and other platforms collect and share information on environmental indicators through platforms managed by several subunits (limited information is available on laboratories). This system integrates the analysis results of samples collected in the different laboratories in the country. Non-health sectors, decentralised units, MCMs, and academic researchers also generate independent information.

Figure 3. Early warning surveillance and information-sharing systems and Laboratory diagnostic capacities.

*indicators: water, forests, soil, air, land use, protected areas, Wildlife Conservation Management Units. Specific data concerning subsystems is listed in Supplementary Material F.

Despite the robustness of the country's existing capacities for sectoral surveillance, information sharing between sectors is uncommon unless officially required. In the specific case of zoonoses and infectious diseases, human and animal diseases are notified and recorded separately in unrelated information systems (. Zoonoses and infectious diseases management and sanitary surveillance). Additionally, official notification standards for the prevention and control of each disease in humans and animals do not yet align with the updated surveillance priorities and prevention and control priorities of the current government´s Specific Action Programmes 2020-2024 (see Multi-level regulations and policies). Overall, these challenges highlight the need for improved integration of surveillance systems, alignment of prevention and control strategies with changing policies, and an integrated approach to disease management based on stakeholders´ coordination.

Table 1. Zoonoses and infectious diseases surveillance and sanitary management.

Multi-level regulations and policies in Mexico

Multi-level regulations and policies are another basic component of One Health governance (). In this study, although the ‘One Health’ concept in Mexico was not explicitly referenced in any law and there was no evidence of a specific OH strategic framework, we identified specific laws covering the health of humans, animals, fish and aquaculture, and the environment. In general, laws in Mexico refer mainly to sector-specific matters but barely establish a connection with other sectors. The General Health Law governs the right to human health protection (a summarised description is available in Supplementary Material G). Laws belonging to the animal and plant sector tackle animal health and quality for food-producing purposes and diminish human sanitary risks. On the environmental side, the Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection Law contains overarching general provisions involving several different stakeholders with mixed responsibilities concerning the ecological management of natural resources. Other specific laws govern wildlife, forestry, water, waste, climate change, and environmental liability matters. Regulations and standards derive from these laws to guarantee the execution of specific provisions.

Table 2. One Health governance elements in Mexico.

Matters related to emergency preparedness and response are also covered by legislation. For example, the General Health Law, in alignment with the International Health Regulations, covers provisions for Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEIC), often involving human epidemics caused by infectious diseases. Historically, the country has responded to international notifications by issuing specific national decrees. These decrees have been issued in the past to declare extraordinary measures and the development of detailed plans for the protection of the population during emergencies, such as during the H1N1 influenza outbreak (i.e. the National Plan for Preparing and Responding to an Escalation of Seasonal or Pandemic Influenza), in preparation for Ebola, and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding other sectors, the Federal Animal Health and the Plant Health Law contain emergency provisions to declare animal epidemics or crop pests causing death or altering their health. Examples of plans deriving from that legal framework include the Emergency Plan for the management of an outbreak of African swine fever. Also, the Civil Protection Law covers other types of multisectoral-affecting disasters and phenomena. The four laws mentioned above may grant the government extraordinary economic resources and mandate multi-sectoral coordination between entities, including subnational and local ones.

In addition to regulations, Mexico has a legal instrument called the National Development Plan (PND) that defines the government's objectives according to the presidential term and identifies the country´s priorities. These are further elaborated into specific programmes, such as the Human Health Sectoral Programme, which outlines objectives, strategies, and actions that the different subunits and institutions are required to follow. During the 2018–2024 presidential term, certain Specific Action Programmes stemming from the previously mentioned sectoral programme adopted a horizontal approach (including one with a specific OH-orientation) aiming to promote efficient prevention and control across the multiple sectors that need to be involved. This means they were designed to address multiple diseases within one programme, based on shared characteristics rather than focusing on a single disease, for instance, including rabies, rickettsiosis, brucellosis, and taeniasis in a single programme (see ). On the other hand, programmes in the animal sector displayed a more human-centered approach, prioritising an ‘Economic perspective’ over animal health and welfare. Regarding environmental concerns, these were drafted through an ‘environmental services’ perspective, which prioritises utility over preservation; this is exemplified in programmes such as the National Water Programme or the National Forest Programme.

Other complex health challenges, such as climate change, have been addressed in special programmes and policies that take a multi and cross-sectoral approach, involving the human, animal, and environmental sectors, as well as relevant non-health sectors. Of note, the AMR National Action Plan (also known as the National Strategy to contain AMR) drafted by the Inter-secretarial Group on AMR in 2018 is one of the only documents with a OH-explicit approach.

Regarding financing, economic resource allocation is primarily specific to each sector, subunit, or institution. Also, government-prioritized programmes can secure additional financial support. In the case of zoonoses and emerging diseases, for example, diseases undergoing elimination efforts, such as leprosy and malaria, received higher priority in prevention and control programmes during the 2018–2024 presidential term. On the other hand, less prevalent diseases like leptospirosis, despite still being listed under the priority zoonotic notification obligations in the official surveillance standard (Secretaría de Salud, Citation2013), was not included and did not receive the same level of attention as diseases listed in the Specific Action Programmes.

OH leadership, MCMs, and human resources

In terms of OH governance leadership, Mexico currently lacks a dedicated OH-specific government body. However, it has established several legally consolidated multisectoral MCMs (non-explicitly OH-oriented) to facilitate formal cross-sectoral collaboration between entities (Supplementary Material H and Appendix i. Glossary). These MCMs demonstrate routine collaboration schemes and occasionally have dedicated economic support. The General Health Council (CSG), comprising nearly half of the secretariats of the country and diverse invitees, holds decision-making powers as a national health authority with regulatory, advisory, and executive functions. It also assumes leadership during sanitary emergencies or events. Another type of MCM includes the so-called ‘Systems,’ which can bring together public and private sector participants into thematic groups. Though usually sectorized, these groups manage to address complex issues, such as the appropriate use of antimicrobials in animals, where multiple stakeholders are involved. Also, the formation of inter-secretarial commissions in Mexico has allowed to address overarching topics such as emerging diseases, biodiversity concerns, the use of pesticides and toxic substances, and climate change; the Commission for the Prevention of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and Other Exotic Animal Diseases is a prominent example of this. Most importantly, each health sector has National Advisory Councils with advisory and consultative functions (councils can sometimes take in civil society participation), such as the Water Advisory Council. Lastly, the formation of formal thematic Groups has allowed more flexible and less sectorized collaborations of government stakeholders in complex health challenges such as food security (i.e. the Intersectoral Health, Food, Environment, and Competitiveness Group).

Our study also identified that many high-profile objectives to advance in zoonotic diseases, AMR, food safety, and preventing environmental risks to human health have been tackled by MCMs that were not formalised as working groups or that did not meet regularly; these are referred to as ad hoc MCMs (Supplementary Material H). Government subunits responsible for human health and its intersections with animals and the environment, such as the National Service for Agrifood Health, Safety and Quality (SENASICA), the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS), and CENAPRECE, were often found to be primary participants in ad hoc MCMs between international and national peers involving agreements, plans, and workshops aligned with regional obligations (regarding rabies elimination for instance). Additionally, there is evidence of ad hoc event meetings of expert participants, for example, to fill out the National AMR tripartite survey every year; these gatherings of people have been observed to grow in size and relevance, eventually forming Groups or Commissions to advance higher objectives.

Concerning OH-trained human resources, in recent years, the previously mentioned government subunits with intersectional objectives, such as SENASICA and CENAPRECE, have promoted the OH-explicit approach through awareness conferences, focusing mainly on zoonoses and AMR (Supplementary material I). Also, decentralised research institutes and academic entities like the National Institute of Public Health (INSP) have developed OH courses. The animal sector has also performed OH-specific multisectoral training for technical experts to strengthen food contamination risk reduction capacities. Concerning research, the orginally known as, theNational Council of Research and Technology (CONACYT) has launched diverse multidisciplinary intersectoral scientific calls for professionals to implement the OH vision. Also, researchers have promoted the approach on their own, through congresses, and as part of other international groups and societies in the region.

The documentary analysis of OH governance infrastructure showed that Mexico displays a sectoral-oriented organisation with no strategic OH framework and few multisectoral policies. However, the country does display many diverse formal and ad hoc MCMs, and evidence of OH training and research. Therefore, the following section explores how these elements could be operationalised to establish a permanent OH governance infrastructure.

Challenges towards the implementation of a One Health governance

Several infrastructure elements that work as enablers () to consolidate a OH governance were identified, but also important barriers (). The complete list of synthesised barriers and enablers can be found in Supplementary Material J.

Table 3. Enablers.

Table 4. Barriers.

Enablers

Enablers identified by key stakeholders were aligned with the findings of the documentary analysis, such as the existence of a sector-specific infrastructure (institutions) and legal and individual regulatory frameworks in charge of either human, animal, or environmental health. Regarding surveillance and laboratory capacities, stakeholders mentioned that information systems in the country (at least sectorally) can react promptly, which is a country's advantage. The pandemic of Influenza H1N1 in 2009 also managed to leverage emergency capacities such as laboratories like the InDRE and its network laboratories.

As identified previously, existing sectoral laws and regulations, multisectoral programmes for zoonoses and climate change, to prevent health emergencies are already in place and this is viewed as an enabler. In addition, during the COVID-19 pandemic, special measures were taken, where the regulatory framework was effectively modified according to shifting needs, which is desirable in OH-addressed health emergencies.

Enablers also included experiences of coordination, collaboration, and capacity building between national stakeholders and cited having formal OH-like structures or Inter-secretarial commissions. Also, during the H1N1 pandemic, stakeholders recalled ad hoc MCMs between the human health and the animal sectors that solved unstated gaps. In addition, as repeatedly pointed out by stakeholders, dog-transmitted human rabies was successfully eliminated in 2019 due to commitment and political will, which resulted in an optimal flow of economic resources and practical activities. Other examples of success highlight the existing communication channels with subnational entities.

Barriers

Key informants noted that OH governance remains hindered by insufficient coordination, poor communication with and between peers, and even mistrust within sectors due to hierarchy and verticality between entities (especially from the Human Health Sector). Also, specific key stakeholders stated that there are individual priorities, no common priorities between sectors, and no horizontal work, including limited sharing of surveillance information and equipment. Collaboration is frequently hampered because there are no instrumented mechanisms for collaboration due to differential sector attributions.

Another barrier for OH governance included the tendency of its objectives to prioritise international agendas over addressing local needs, neglecting the actual requirements of the region. This observation may be also consistent with the tendency to prioritise and fund emergency response over local prevention of health challenges. Also, despite the publication of adapted OH documents, such as the AMR National Action Plan, stakeholders mentioned a lack of follow-up toward appropriate implementation.

Moreover, most human resources were considered sectorally trained and lacked OH integrative training. The absence of a non-biased vision reflects itself in the fact that there is usually no leadership or OH focal point identified to work with regarding international commitments. Regarding MCMs, although several informants agreed that Mexico has had successful collaborations between sectors, they underlined the difficulties of establishing long-term organisational changes and network support due to a high turnover of political stakeholders.

Recommendations by key stakeholders

Key informants suggested several recommendations to improve OH governance in Mexico, including changing the current sectoral infrastructure organisation. One interviewee argued that due to the critical connections between zoonosis, food safety, and animal welfare, ‘SEMARNAT … we have to remove its wildlife directorate … Agriculture should also be stripped of its part of Animal Health and Plant Health and be transferred to the Ministry of Health … ’ (16, Academia, Animal Sector). Also, it was mentioned that ‘there should be a super-connected axis’ between health and other sectors, including joint programmes (13, Academia, Environmental Sector). Many interviewees stressed that the reduction of natural spaces is likely to increase the probability of pathogens causing human and animal diseases; therefore, ‘[a] very aggressive policy towards the conservation of natural ecosystems is … one of the outstanding missing elements … ’ (9, Environmental Sector). The need to reinvent the CSG or to create a novel OH committee, including other perspectives that transcend human public health, was often mentioned. Stakeholders also commented that creating appropriate attributions for cooperation is needed: ‘The regulations, rules, norms that arise in the country for the approach to any of these diseases should be developed jointly … that each one has … responsibilities well established for … common objectives … ’ (17, Human Health Sector). Recommendations also included incorporating other stakeholders ‘from the bottom up’ such as academia and CSOs. Regarding AMR: ‘We should try to combine what is now dispersed … that … epidemiological surveillance of infectious agents and antimicrobial resistant strains are seen in a cross-cutting, multisectoral way … A very broad program … .’ (12, Human Health Sector). Finally, an interviewee recommended institutionalising or creating new OH laws or policies ‘translated into a special national program, arising from an inter-secretariat structure with government institutions and translated into state strategies … which in turn contemplates the municipalities’ (9, Environmental Sector).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the extent to which institutionalised OH governance exists in Mexico and reflects on how to improve the implementation of OH governance to address complex health challenges. It revealed that each of the human health, animal, and environmental sectors is already equipped with OH-relevant infrastructure (i.e. institutions) and multi-level regulations, but these remain primarily unlinked or require additional coordination; they also need to address barriers such as a lack of harmonised frameworks, limited cross-sectoral data sharing, and other implementation challenges. Nevertheless, evidence indicates a growing orientation towards OH cross-sectoral collaboration, especially in the form of OH-oriented policies, formal and ad hoc MCMs, and an increasing emphasis on OH human resource development and research.

In Latin America, as previously mentioned, few countries, such as Brazil (Wakimoto et al., Citation2022) and now Mexico, have conducted OH governance assessments; Colombia has documented several aspects as well (Cediel Becerra et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is essential to focus on identifying similarities or areas of opportunity that will differ from those in HICs; the latter include the institutionalisation and implementation of the approach.

In Mexico, as can also be observed in other MICs in the region (i.e. Brazil), there is little coordination among sectors despite having strong sector-specific infrastructure elements, typical of a consolidated State, which could enable OH collaboration efforts (Corrêa et al., Citation2023; Espeschit et al., Citation2021; Mor, Citation2023; Wakimoto et al., Citation2022). One way of addressing coordination issues, as suggested by some interviewees, is by creating or altering infrastructure responsible for separate processes, similarly to what HICs do. For example, Sweden developed a specific institution for veterinary health, while Denmark established a specific institution for natural resource protection, splitting from its food and trade component, to avoid competing priorities among them (Humboldt-Dachroeden, Citation2022; Ministry of Environment of Denmark, Citation2023). However, such approaches can be costly and risk creating new silos by ‘reinventing the wheel instead of funding what is already existing’ (Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2022). Another recommendation from stakeholders regarding institutionalisation was to create or redistribute One Health operational units in other ministries, including non-health sectors. Such a unit could be critical in Ministries of Economy or Land Management (Loh et al., Citation2015; Mor, Citation2023) to prevent disorganised growth and resource depletion that damages ecosystems and contributes to the emergence of complex health challenges. However, achieving this solution requires political commitment and financing for OH governance, which are common barriers in the region.

Coordinating existing surveillance systems also stood out as a crucial starting point for enhancing One Health governance institutionalisation and improving decision-making, especially in countries like Brazil and Mexico, which possess robust but disjointed surveillance systems (Espeschit et al., Citation2021). To address this, it is imperative to conduct a comprehensive situational analysis within and across sectors to align methods, technologies, and analytical approaches, considering regulatory frameworks and logistical aspects (Dos S Ribeiro et al., Citation2019; Espeschit et al., Citation2021).

In Mexico, plans were announced to develop a National Centre of Epidemiological Intelligence, aiming to integrate previously unconnected and duplicated human data sources (Secretaría de Salud, Citation2022); however, this initiative is still in progress. In a OH governance context, integrating data across all relevant health sectors will be crucial (Ghai et al., Citation2022). For example, creating a joint platform that exchanges data on humans, livestock, and wildlife will be particularly beneficial for diseases like rabies, as remarked by Brazil and Colombia (Bastos et al., Citation2021; Cediel-Becerra et al., Citation2023). Concerning AMR, there are lessons to be learned from Colombia´s experience in integrating surveillance data from both the human and animal sectors through collaboration among public and private entities, international agencies, and academia, managing to share information and optimise resources (Donado-Godoy et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez et al., Citation2023). Regarding this particular topic, regional-level articulation could be a useful capacity-building implementation strategy (Elnaiem et al., Citation2023). Finally, Mexico collects government and academia-generated environmental data, however, integrating it into OH-oriented surveillance systems is still pending. Furthermore, monitoring One Health Index (OHI) indicators could help to address interacting animal health and environmental issues, such as chemical pollutants and defaunation, extending beyond zoonoses and infectious diseases (Mor, Citation2023; Zhang et al., Citation2022).

Our findings on the multi-level regulations component of OH governance brought to light a significant challenge; specifically, they highlighted the coordination issue among the numerous existing sector-specific and multisectoral regulations, standards, and policies. In Mexico, this coordination is further complicated by the involvement of many actors (Riojas-Rodríguez et al., Citation2013) with unclear responsibilities and attributions, leading to a lack of accountability. To address this, the creation of a flexible multisectoral political instrument (Sheikh et al., Citation2021), such as a OH strategic framework or plan (which currently does not exist in the country and in most countries in the region) could help to solve priority gaps in the law and establish new responsibilities. However, experiences from LMICs show that coordination and implementation issues can persist despite the existence of such a framework (Igihozo et al., Citation2022).

Updating instruments to adopt a OH approach and aligning them with existing ones was also identified as a complex task. An example was presented earlier in the text: despite Mexico´s progress in developing several programmes focusing on recommended horizontal disease prevention (Ghai et al., Citation2022; McKenzie et al., Citation2016; Taaffe et al., Citation2023), the country encountered challenges due to the lack of harmonisation with existing legally binding normative standards, whose function is to guide quality regulatory actions, including prevention, control, and surveillance notifications within programmes. In response, and since these standards are usually outdated and slow to modify, the government considered cancelling them with the intention of developing easily updatable guidelines aligned with current programmes; however, this was met with open stakeholder confrontation (Mondragón, Citation2023). In the near future, harmonising these programmes with a OH strategic framework and establishing mechanisms to address legal gaps will be crucial to prevent implementation difficulties.

In our findings, political priorities wielded significant influence, as evidenced during health emergencies such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In Mexico, such emergencies prompt immediate prioritisation, funding, and coordination. However, when it comes to prevention policies, national priorities have historically favoured unsustainable economic growth, particularly favouring the food-producing industry over animal and environmental health, which echoes trends in other Latin American countries (Wakimoto et al., Citation2022). In Mexico, this emphasis has been translated into funding cuts and personnel reductions by political decree in the animal and environmental health sectors, with the latter remaining the most neglected aspect of OH governance in Mexico and other Latin American countries (Cediel Becerra et al., Citation2021; Corrêa et al., Citation2023).

Unclear and changing priorities are additional challenges in addressing complex OH health challenges. For instance, in Mexico, initially, AMR did not have a prominent status on the national agenda due to its complexity, the lack of political will to address it, and the absence of a dedicated governmental office to coordinate AMR policies (Dreser Mansilla, Citation2018). Also, this study evidenced a difficulty in appropriating the international agenda to tackle this problem. These situations mirror almost identical AMR governance challenges in Brazil (Corrêa et al., Citation2023).

Another example of changing priorities is the high turnover of public officials due to government changes in Mexico, which significantly impacted the continuity of policies and inter-secretarial commissions, such as those related to climate change, as evidenced by interviewees. These changes threaten the implementation and sustained support and efforts, leading to ‘loss of the institutional memory’ (Corrêa et al., Citation2023), and underscore the importance of political commitment and financial support (Ear, Citation2012). Of note, the effective functioning of OH governance and the implementation of OH actions require, as is often forgotten, continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation to ensure effectiveness and resilience, especially in response to political changes (Dos S Ribeiro et al., Citation2019).

Our study also emphasised the relevance of MCMs in OH governance, as they help to lead and implement multisectoral or inter-secretarial mandates. For example, Rwanda established a formal and independent OH steering committee, allowing the country to develop joint strategies and allocate funding and resources (Igihozo et al., Citation2022). In Mexico, such a hierarchical coordination or a ‘higher authority’ (Corrêa et al., Citation2023) exists in the form of the General Health Council, also known as the CSG. This structure may help to prevent overlapping decision-making and serve as an impartial agency between actors, ensuring their compliance (Asaaga et al., Citation2021; Corrêa et al., Citation2023). However, this model may not be the solution, as concerns have been raised about it, leading to the MoH prioritising its own agenda (Mor, Citation2023). Also, if OH leading functions should be assigned to the General Health Council, other challenges must be addressed first. One of those is the Council's loss of authority due to political decisions, as reported by some of our interviewees. Additionally, it will be necessary to overcome the visible group homophilyFootnote4 within it (Humboldt-Dachroeden, Citation2022), where only government stakeholders prevail while sidelining non-government ones, such as the academia (DOF (Official Journal of the Federation), Citation2023b).

Effective OH governance will require that the central OH-steering MCM facilitates horizontal participation from existing and emerging MCMs. Establishing multilevel governmental OH operational units (Munyua et al., Citation2019) at national and subnational levels (considering the existing ones) could work to distribute power effectively (Mor, Citation2023). Also, in a large country like Mexico, horizontal participation should include state and local governments and communities, including citizens and indigenous voices (often overlooked and not addressed in this study), in decision-making processes (Buregyeya et al., Citation2020; Humboldt-Dachroeden, Citation2022; Pettan-Brewer et al., Citation2021). For instance, community participation in the notification and adoption of measures could be crucial to tackle zoonoses and other environmental issues.

At present, formal MCMs continue to emerge in the country as ways to tackle previously unattended challenges like AMR; such is the case of the Technical AMR Committee and sectoral subcommittees (DOF (Official Journal of the Federation), Citation2023a). Nevertheless, evaluating their effectiveness and identifying what has worked well or failed is pending (Elnaiem et al., Citation2023). Common issues identified in LMICs, like lack of cooperation and information asymmetries among MCMs and in cross-sectoral initiatives, will most probably represent a challenge (Asaaga et al., Citation2021; Buregyeya et al., Citation2020; Yopa et al., Citation2023).

Also, while there is value in the political and technical consolidation of most formal MCMs (Ear, Citation2012; McKenzie et al., Citation2016), not all of them (especially ad hoc ones) need to be institutionalised. Less formal collaborations, non-de Jure, or soft capacities can also be effective (Sheikh et al., Citation2021), as seen in our study. However, it will be important to evaluate the strength of these partnerships over time (Abbas et al., Citation2022; Asaaga et al., Citation2021). Clear delineation of technical responsibilities, regular assessment of outcomes, and fostering joint accountability can enhance overall responsibility. Offering incentives, distributing shared funds, and establishing collaborative budgets may decrease reliance on goodwill and informal interpersonal cooperation (Asaaga et al., Citation2021; Ruckert et al., Citation2020a).

Finally, the establishment of effective OH governance requires the professionalisation of multidisciplinary human resources, which is slowly growing but still remains a barrier in the country, as in many other LMICs/MICs due to non-sustained efforts. This should include integrating One Health education into academic curricula and continuous training for public servants, creating the needed future OH expertise (Espeschit et al., Citation2021). Also, advocacy campaigns in the country, particularly on social media platforms, should be used to communicate with higher levels of government to embed OH culture (Ghai et al., Citation2022).

Going beyond epidemiological, biomedical, and public health system aspects, research will play a pivotal role in the development of OH governance. Evidence supporting integrated policies and coordinated policymaking (McKenzie et al., Citation2016) and cost-effectiveness analyses should help to secure resources and support (Ghai et al., Citation2022) as countries adopt their own home-grown, national OH agenda. Transforming academic research projects into nationally embedded initiatives can accelerate progress at the local level. In this sense, identifying champions of One Health within the government, non-governmental organisations, and academic institutions is crucial to keep pushing for economic support and institutionalisation (Okello et al., Citation2014).

Limitations

This rapid environmental scan provides an overview of the current collaboration between the health sectors in Mexico but was not designed to provide an exhaustive description of all published information (which would be difficult due to rapid progress in the field). Findings are current to completing the last additions to the document scan and key informant interviews (as of June 2022). Other aspects, such as equity, were not included in this manuscript and should be the focus of future research in this area. In addition, addressing a subnational perspective was outside this study's scope but will be essential to be included in future works. Finally, most of the infrastructure described was part of the government, which was the focus of the study, but other stakeholders and NGOs should be described in future studies.

Conclusions

The current environmental scan represents an analysis of existing governance infrastructure in Mexico to inform progress towards implementing a formal OH governance approach. Understanding the present sectoral panorama and identifying governance enablers and barriers can help to fully embed OH principles in the country. Building a OH governance in Mexico entails the creation of a OH strategic framework and the designation of a leading OH governing body; the enhancement of current MCMs; the harmonisation of OH policies and programmes with existing instruments; potentially restructuring infrastructure and surveillance systems; and the formation of a skilled OH workforce. This assessment can also inform other countries in the region and other MICs facing similar challenges, providing valuable insights into their own circumstances. Garnering international support from organisations like the Quadripartite will be vital to drive One Health agendas forward without waiting until the next emergency to prevent, prepare, and respond.

Ethical approval

The present study was registered with the number 1671 under the National Institute of Public Health's Institutional Review Board.

Appendixiiii13ene23.docx

Download MS Word (42.9 KB)Supplementary Material_24jun24_.docx

Download MS Word (434.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Global 1 Health Network for funding and logistical support. We would also like to acknowledge Alejandro Álvarez, Andrea Anaya, Jesús Isaac Rico, Blanca Pelcastre, and especially our key actors for their valuable contributions. We are grateful for continuous dedicated support from Hortensia Reyes and Germán Guerra.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Quadripartite alliance: encompassed by the World Health Organization (WHO), The World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) (previously known as the OIE), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

2 Institutionalisation: the process of embedding a conception (or approach) within an organization, system, or society.

3 Multi-coordination mechanisms (MCMs): can be formed among formal multisector groups with routine meetings, described roles and responsibilities, guidelines and functions, and monitored results to strengthen or develop collaboration, communication, and coordination between two or more entities from different sectors (Abbas et al., Citation2022; FAO et al., Citation2019).

4 Homophily: ‘the principle that a contact between similar people occurs at a higher rate than among dissimilar people’ (McPherson et al., Citation2001)

References

- Abbas, S. S., Shorten, T., & Rushton, J. (2022). Meanings and mechanisms of One Health partnerships: Insights from a critical review of literature on cross-government collaborations. Health Policy and Planning, 37(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab134

- Asaaga, F. A., Young, J. C., Oommen, M. A., Chandarana, R., August, J., Joshi, J., Chanda, M. M., Vanak, A. T., Srinivas, P. N., Hoti, S. L., Seshadri, T., & Purse, B. V. (2021). Operationalising the “One Health” approach in India: Facilitators of and barriers to effective cross-sector convergence for zoonoses prevention and control. BMC public health, 21(1), 1517. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11545-7

- Bastos, V., Mota, R., Guimarães, M., Richard, Y., Lima, A. L., Casseb, A., Barata, G. C., Andrade, J., & Casseb, L. M. N. (2021). Challenges of rabies surveillance in the eastern Amazon: The need of a one health approach to predict rabies spillover. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fpubh.2021.624574.

- Benedetti, G., Jokelainen, P., & Ethelberg, S. (2022). Search term “One Health” remains of limited use to identify relevant scientific publications: Denmark as a case study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 938460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.938460

- Bennett, S., Glandon, D., & Rasanathan, K. (2018). Governing multisectoral action for health in low-income and middle-income countries: Unpacking the problem and rising to the challenge. BMJ Global Health, 3(Suppl 4), e000880. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000880

- Bhatia, R. (2021). Addressing challenge of zoonotic diseases through One Health approach. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 153(3), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_374_21

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buregyeya, E., Atusingwize, E., Nsamba, P., Musoke, D., Naigaga, I., Kabasa, J. D., Amuguni, H., & Bazeyo, W. (2020). Operationalizing the One Health approach in Uganda: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 10(4), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.200825.001

- Cámara de Diputados. (2021). Leyes Federales Vigentes. Retrieved October 22, 2021 from: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/index.htm

- Cediel-Becerra, N., Collins, R., Restrepo, D., Pardo, M. C., Polo, L. J., & Villamil, L. C. (2023). Lessons learned from the history of rabies vaccination in Colombia using the One Health approach. One Health & Implementation Research, 3(2), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2023.01

- Cediel Becerra, N. M., Olaya Medellin, A. M., Tomassone, L., Chiesa, F., & De Meneghi, D. (2021). A survey on One Health approach in Colombia and some Latin American countries: From a fragmented health organization to an integrated health response to global challenges. Frontiers in public health, 9, 649240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.649240

- Cordova-Villalobos, J. A., Macias, A. E., Hernandez-Avila, M., Dominguez-Cherit, G., Lopez-Gatell, H., Alpuche-Aranda, C., & Ponce de León-Rosales, S. (2017). The 2009 pandemic in Mexico: Experience and lessons regarding national preparedness policies for seasonal and epidemic influenza. Gaceta Medica de Mexico, 153(1), 102–110.

- Corrêa, J. S., Zago, L. F., Da Silva-Brandão, R. R., de Oliveira, S. M., Fracolli, L. A., Padoveze, M. C., & Cordoba, G. (2023). The governance of antimicrobial resistance in Brazil: Challenges for developing and implementing a One Health agenda. Global Public Health, 18(1), 2190381. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2023.2190381

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D., Mavingui, P., Boetsch, G., Boissier, J., Darriet, F., Duboz, P., Fritsch, C., Giraudoux, P., Le Roux, F., Morand, S., Paillard, C., Pontier, D., Sueur, C., & Voituron, Y. (2018). The One Health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5(14), https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00014

- DOF (Official Journal of the Federation). (2021). ACUERDO mediante el cual se dan a conocer en los Estados Unidos Mexicanos las enfermedades y plagas exóticas y endémicas de notificación obligatoria de los animales terrestres y acuáticos. Retrieved December 07, 2023 from: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5545304&fecha=29/11/2018#gsc.tab=0

- DOF (Official Journal of the Federation). (2023a). ACUERDO por el que se establece la integración y funcionamiento del Comité Técnico sobre Resistencia a los Antimicrobianos. Retrieved December 07, 2023 from: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5692245&fecha=15/06/2023#gsc.tab=0

- DOF (Official Journal of the Federation). (2023b). DECRETO por el que se expide el Reglamento Interior del Consejo de Salubridad General. Retrieved December 21, 2023 from: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5711276&fecha=13/12/2023#gsc.tab=0

- Donado-Godoy, P., Castellanos, R., León, M., Arevalo, A., Clavijo, V., Bernal, J., León, D., Tafur, M. A., Byrne, B. A., Smith, W. A., & Perez-Gutierrez, E. (2015). The establishment of the colombian integrated program for antimicrobial resistance surveillance (COIPARS): A pilot project on poultry farms, slaughterhouses and retail market. Zoonoses and Public Health, 62(s1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12192

- Dos S Ribeiro, C., van de Burgwal, L. H. M., & Regeer, B. J. (2019). Overcoming challenges for designing and implementing the One Health approach: A systematic review of the literature. One Health (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 7, 100085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2019.100085

- Dreser Mansilla, A. (2018). Antibiotics in Mexico: An analysis of problems, policies, and politics [Doctoral dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine]. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Online Repository. https://doi.org/10.17037/PUBS.04650760

- Ear, S. (2012). Swine flu. Mexico’s handling of A/H1N1 in comparative perspective. Politics and the life sciences : The journal of the Association for Politics and the Life Sciences, 31(1-2), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.2990/31_1-2_52

- Elnaiem, A., Mohamed-Ahmed, O., Zumla, A., Mecaskey, J., Charron, N., Abakar, M. F., Raji, T., Bahalim, A., Manikam, L., Risk, O., Okereke, E., Squires, N., Nkengasong, J., Rüegg, S.R., Hamid, M.M.A., Osman, A.Y., Kapata, N., Alders, R., Heymann, D.L., & Dar, O. (2023). Global and regional governance of One Health and implications for global health security. The Lancet, 401(10377), 688–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01597-5

- Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 7(3), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

- Espeschit, I., de, F., Santana, C. M., & Moreira, M. A. S. (2021). Public policies and One Health in Brazil: The challenge of the disarticulation. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 644748. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.644748

- FAO, UNEP, WHO, & WOAH. (2022). One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022-2026). Working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment. World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Organisation for Animal Health & United Nations Environment Programme. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc2289en

- FAO, WOAH, & WHO. (2019). Taking a multisectoral, one health approach: A tripartite guide to addressing zoonotic diseases in countries. FAO, WOAH, WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514934

- Garza, J. (2010). La situación actual de las zoonosis más frecuentes en México. Gaceta medica de Mexico, 146, 430–436.

- Ghai, R. R., Wallace, R. M., Kile, J. C., Shoemaker, T. R., Vieira, A. R., Negron, M. E., Shadomy, S. V., Sinclair, J. R., Goryoka, G. W., Salyer, S. J., & Barton Behravesh, C. (2022). A generalizable One Health framework for the control of zoonotic diseases. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 8588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12619-1

- Gobierno de México. (n.d.). Normas oficiales mexicanas. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from: http://www.profepa.gob.mx/innovaportal/v/325/1/mx/normas_oficiales_mexicanas.html

- González-Roldán, J. F., Undurraga, E. A., Meltzer, M. I., Atkins, C., Vargas-Pino, F., Gutiérrez-Cedillo, V., & Hernández-Pérez, J. R. (2021). Cost-effectiveness of the national dog rabies prevention and control program in Mexico, 1990-2015. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 15(3), e0009130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009130

- Humboldt-Dachroeden, S. (2022). A governance and coordination perspective - Sweden's and Italy's approaches to implementing One Health. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health, 2, 100198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100198

- Igihozo, G., Henley, P., Ruckert, A., Karangwa, C., Habimana, R., Manishimwe, R., Ishema, L., Carabin, H., Wiktorowicz, M. E., & Labonté, R. (2022). An environmental scan of One Health preparedness and response: The case of the Covid-19 pandemic in Rwanda. One Health Outlook, 4(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42522-021-00059-2

- INEGI. (2023). México en Cifras [INEGI]. Retrieved July, 2023, from: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/areasgeograficas/#collapse-Resumen

- Lee, K., & Brumme, Z. L. (2013). Operationalizing the One Health approach: The global governance challenges. Health Policy and Planning, 28(7), 778–785. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs127

- Loh, E. H., Zambrana-Torrelio, C., Olival, K. J., Bogich, T. L., Johnson, C. K., Mazet, J. A. K., Karesh, W., & Daszak, P. (2015). Targeting transmission pathways for emerging zoonotic disease surveillance and control. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 15(7), 432–437. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2013.1563

- Martínez Coronado, M. (2016). The Mexican experience of the NAPAPI revision process. Contexto Internacional, 38(1), 203-239. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100006

- Mbabu, M., Njeru, I., File, S., Osoro, E., Kiambi, S., Bitek, A., Ithondeka, P., Kairu-Wanyoike, S., Sharif, S., Gogstad, E., Gakuya, F., Sandhaus, K., Munyua, P., Montgomery, J., Breiman, R., Rubin, C., & Njenga, K. (2014). Establishing a One Health office in Kenya. The Pan African Medical Journal, 19, 106. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.19.106.4588

- McKenzie, J. S., Dahal, R., Kakkar, M., Debnath, N., Rahman, M., Dorjee, S., Naeem, K., Wijayathilaka, T., Sharma, B. K., Maidanwal, N., Halimi, A., Kim, E., Chatterjee, P., & Devleesschauwer, B. (2016). One Health research and training and government support for One Health in South Asia. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 6(1), 33842. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v6.33842

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Ministry of Environment of Denmark. (2023). Objects and history. Retrieved August 17, 2023, from: https://en.mim.dk/the-ministry/objects-and-history/

- Mondragón, L. M. (2023). Cancelar 34 Normas de Salud tendrá graves consecuencias. Cámara Periodismo Legislativo. Retrieved December 05, 2023, from: https://comunicacionsocial.diputados.gob.mx/revista/index.php/a-profundidad/cancelar-34-normas-de-salud-tendra-graves-consecuencias

- Mor, N. (2023). Organising for One Health in a developing country. One Health, 17, 100611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100611

- Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

- Munyua, P. M., Njenga, M. K., Osoro, E. M., Onyango, C. O., Bitek, A. O., Mwatondo, A., Muturi, M. K., Musee, N., Bigogo, G., Otiang, E., Ade, F., Lowther, S. A., Breiman, R. F., Neatherlin, J., Montgomery, J., & Widdowson, M. A. (2019). Successes and challenges of the One Health approach in Kenya over the last decade. BMC Public Health, 19(Suppl 3), 465. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6772-7

- Nyatanyi, T., Wilkes, M., McDermott, H., Nzietchueng, S., Gafarasi, I., Mudakikwa, A., Kinani, J. F., Rukelibuga, J., Omolo, J., Mupfasoni, D., Kabeja, A., Nyamusore, J., Nziza, J., Hakizimana, J.L., Kamugisha, J., Nkunda, R., Kibuuka, R., Rugigana, E., Farmer, P., & Binagwaho, A. (2017). Implementing One Health as an integrated approach to health in Rwanda. BMJ Global Health, 2(1), e000121. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000121

- Okello, A. L., Bardosh, K., Smith, J., & Welburn, S. C. (2014). One Health: Past Successes and Future Challenges in Three African Contexts. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(5), e2884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002884

- One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP), Adisasmito, W. B., Almuhairi, S., Behravesh, C. B., Bilivogui, P., Bukachi, S. A., Casas, N., Becerra, N. C., Charron, D. F., Chaudhary, A., Zanella, J. R. C., & Cunningham, A. A. (2022). One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS Pathogens, 18(6), e1010537–2023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010537

- Otu, A., Effa, E., Meseko, C., Cadmus, S., Ochu, C., Athingo, R., Namisango, E., Ogoina, D., Okonofua, F., & Ebenso, B. (2021). Africa needs to prioritize One Health approaches that focus on the environment, animal health and human health. Nature Medicine, 27(6), 943–946. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01375-w

- Pettan-Brewer, C., Figueroa, D. P., Cediel-Becerra, N., Kahn, L. H., Martins, A. F., & Biondo, A. W. (2022). Editorial: Challenges and successes of One Health in the context of planetary health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1081067. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1081067

- Pettan-Brewer, C., Martins, A. F., Abreu, D. P. B. d., Brandão, A. P. D., Barbosa, D. S., Figueroa, D. P., Cediel, N., Kahn, L. H., Brandespim, D. F., Velásquez, J. C. C., Carvalho, A. A. B., Takayanagui, A. M. M., Galhardo, J. A., Maia-Filho, L. F. A., Pimpão, C. T., Vicente, C. R., & Biondo, A. W. (2021). From the approach to the concept: One Health in Latin America-experiences and perspectives in Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. Frontiers in public health, 9, 687110. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPUBH.2021.687110

- Rasanathan, K., Bennett, S., Atkins, V., Beschel, R., Carrasquilla, G., Charles, J., Dasgupta, R., Emerson, K., Glandon, D., Kanchanachitra, C., Kingsley, Soucat, A., Ssennyonjo , A., Wismar, M., & Zaidi, S. (2017). Governing multisectoral action for health in low- and middle-income countries. PLOS Medicine, 14(4), e1002285. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002285

- Riojas-Rodríguez, H., Schilmann, A., López-Carrillo, L., & Finkelman, J. (2013). La salud ambiental en México: situación actual y perspectivas futuras. Salud Pública de México, 55(6), 638–649. Retrieved on July 02, 2023 from: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-36342013001000013&lng=es&tlng=es

- Robbiati, C., Milano, A., Declich, S., Di Domenico, K., Mancini, L., Pizzarelli, S., D’Angelo, F., Riccardo, F., Scavia, G., & Dente, M. G. (2023). One health adoption within prevention, preparedness and response to health threats: Highlights from a scoping review. One Health, 17, 100613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100613

- Rodríguez, M., Vásquez, G. A., & Cediel-Becerra, N. (2023). Alianzas públicas, privadas y público-privadas para implementar Una Salud como acción contra la resistencia antimicrobiana en Colombia. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 47, e64. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2023.64

- Ruckert, A., Fafard, P., Hindmarch, S., Morris, A., Packer, C., Patrick, D., Weese, S., Wilson, K., Wong, A., & Labonté, R. (2020a). Governing antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review of global governance mechanisms. Journal of Public Health Policy, 41(4), 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-020-00248-9

- Ruckert, A., Harris, F., Aenishaenslin, C., Aguiar, R., Boudreau LeBlanc, A., Carmo, L., Labonté, R., Lambraki, I., Parmley, E., & Wiktorowicz, M. (2024). One Health governance principles for AMR surveillance: A scoping review and conceptual framework. Research Directions: One Health, 2. https://doi.org/10.1017/one.2023.13

- Ruckert, A., Zinszer, K., Zarowsky, C., Labonté, R., & Carabin, H. (2020b). What role for One Health in the COVID-19 pandemic? Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111(5), 641. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00409-z

- Schneider, M. C., Min, K. D., Romijn, P. C., De Morais, N. B., Montebello, L., Manrique Rocha, S., Sciancalepore, S., Hamrick, P. N., Uieda, W., Câmara, V. M., Luiz, R. R., & Belotto, R. (2023). Fifty years of the National Rabies Control Program in Brazil under the One Health perspective. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 12(11), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12111342

- Secretaría de Salud. (2013). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-017-SSA2-2012, Para la vigilancia epidemiológica. Retrieved October 23, 2021 from: https://epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/gobmx/salud/documentos/manuales/00_NOM-017-SSA2-2012_para_vig_epidemiologica.pdf

- Secretaría de Salud. (2022). 109. Centro Nacional de Inteligencia en Salud contribuirá a la toma de decisiones en emergencias sanitarias. Retrieved August 01, 2023 from: https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/109-centro-nacional-de-inteligencia-en-salud-contribuira-a-la-toma-de-decisiones-en-emergencias-sanitarias?idiom=es

- Sheikh, K., Sriram, V., Rouffy, B., Lane, B., Soucat, A., & Bigdeli, M. (2021). Governance roles and capacities of ministries of health: A multidimensional framework. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(5), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.39

- Taaffe, J., Sharma, R., Parthiban, A. B. R., Singh, J., Kaur, P., Singh, B. B., Gill, J. P. S., Gopal, D. R., Dhand, N. K., & Parekh, F. K. (2023). One Health activities to reinforce intersectoral coordination at local levels in India. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1041447. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1041447

- Wakimoto, M. D., Menezes, R. C., Pereira, S. A., Nery, T., Castro-Alves, J., Penetra, S. L. S., Ruckert, A., Labonté, R., & Veloso, V. G. (2022). COVID-19 and zoonoses in Brazil: Environmental scan of One Health preparedness and response. One Health, 14, 100400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2022.100400

- Wilburn, A., Vanderpool, R. C., & Knight, J. R. (2016). Environmental scanning as a public health tool: Kentucky’s human papillomavirus vaccination project. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E109. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd13.160165

- Yopa, D. S., Massom, D. M., Kiki, G. M., Sophie, R. W., Fasine, S., Thiam, O., Zinaba, L., & Ngangue, P. (2023). Barriers and enablers to the implementation of One Health strategies in developing countries: A systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health, , 11., 1252428.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1252428

- Zenteno-Savin, T., Straatmann, D., Huyvaert, K. P., Tucker, C., Castro-Prieto, A., & Sobral, B. (2017). Conferencia sobre “Una Salud en Las Americas”. Recursos Naturales y Sociedad, 3(2), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.18846/renaysoc.2017.03.03.02.0001

- Zhang, X. X., Liu, J. S., Han, L. F., Xia, S., Li, S. Z., Li, O. Y., Kassegne, K., Li, M., Yin, K., Hu, Q. Q., Xiu, L. S., Zhu, Y.Z., Huang, L.Y., Wang, X.C., Zhang, Y., Zhao, H.Q., Yin, J.X., Jiang, T.G., Li, Q., & Zhou, X.N. (2022). Towards a global One Health index: A potential assessment tool for One Health performance. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 11(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-00979-9

- Zinsstag, J., Schelling, E., Wyss, K., & Mahamat, M. B. (2005). Potential of cooperation between human and animal health to strengthen health systems. The Lancet, 366(9503), 2142–2145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67731-8