ABSTRACT

The ubiquity of public-space sexual harassment (PSH) of women in the global South, particularly in South Asia, is both a public health and gender equity issue. This study examined men’s experiences with and perspectives on PSH of women in three countries with shared cultural norms and considerable gender inequalities – Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. The three-country survey in 2021–2022 was completed by 237 men who were generally young, urban, single, well-educated, and middle-/high-income. Among the 53.3% who witnessed PSH, 80% reported intervening to stop it or help the victim. A substantial share of men worried about PSH, and bore emotional, time, and financial costs as they took precautionary or restorative measures to help women in their families avoid PSH or deal with its consequences. Most respondents articulated potential gains for men, women, and society if PSH no longer existed. However, a non-negligible share of participants held patriarchal gender attitudes that are often used to justify harassment, and a small share did not favour legal and community sanctions. Many called for stricter legal sanctions and enforcement, culture change, and education. Men’s perspectives offer insights for prevention of harassment and mitigation of its consequences.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

The ubiquity of public-space sexual harassment (PSH) of women in the global South, particularly in South Asia, is both a public health and gender inequity problem. PSH, also known as street harassment, is experienced by women and girls in public spaces in the form of menacing, staring, following, insults, vulgar gestures, or comments, inappropriate or aggressive touching. While sexual harassment in workplace and academic settings has been widely studied globally, this is not the case for PSH, which is equally important for women’s achievement of basic human capabilities, such as educational, livelihood, leadership, and social aspirations. In the last decade there has been growth in research on women’s experiences of PSH in the global South (e.g. Dhillon & Bakaya, Citation2014; Bharucha & Khatri, Citation2018; Ahmad et al., Citation2020). Based on small-scale surveys, these studies highlight the pervasive nature of PSH and its immediate and potential long-term adverse consequences for women and society. By contrast, men’s views on or responses to PSH are underexplored (Fileborn & O’Neill, Citation2023; Fairchild, Citation2023).

In South Asia, along with the Middle East and North Africa, PSH is argued to be a means for men to maintain traditional gender norms that reserve public spaces for men and confine women to the private domain (Ilahi, Citation2009). As with other forms of gender-based violence (GBV), PSH entails victim-blaming, which leads women to learn not to speak about the incidents they experience (Shahid et al., Citation2021). Women often do not disclose street harassment even to family members for fear that it might further restrict their mobility (Dhillon & Bakaya, Citation2014; Hebert et al., Citation2020). Nor do women regularly report to police or other authorities, even though PSH is a crime in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Due to the perceived lower severity and normalisation of PSH as a form of sexual violence, when women report incidents to the police, they are met with victim blaming and inaction or harassed by the police (Ilahi, Citation2009; Dhillon & Bakaya, Citation2014; Bergenfeld et al., Citation2022; Ribeiro, Citation2024).

Confronting GBV by working with men and boys has been on feminist activist agendas in the last decade (Mitchell, Citation2013; Doyle & Kato-Wallace, Citation2021). This approach calls for understanding the views of men and boys. Yet, there are few studies on men’s views of PSH, and those have engaged perpetrators to examine their perceptions and motivations (Henry, Citation2017; Zietz & Das, Citation2018). The scant literature on men’s perspectives is surprising given the clear burden on men who are compelled to escort and assure safety of female family members in public (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). We address this gap by contributing evidence on men’s perspectives on PSH in three South Asian countries with shared gender norms. Based on small-scale surveys of men in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan in 2021–2022, we examined men’s experiences of PSH, how it affects men, their views on the gender norms that contribute to PSH and the solutions to address PSH.

Background: Public-space sexual harassment in South Asia

In the South Asian context, attention to PSH as a form of GBV increased in the aftermath of serious cases of sexual assault in the last decade (Adur & Jha, Citation2018; Verma et al., Citation2017). While often dismissed and trivialised as ‘merely compliments’ in the global North (Fairchild, Citation2023) and ‘eve-teasing’ in the Indian/South Asian context (Misri, Citation2017; Raman & Komarraju, Citation2018), feminist scholarship conceptualises PSH on the spectrum of violence against women, rooted in discriminatory gender norms (Fileborn & O’Neill, Citation2023). Recent studies on South Asia indicate a high prevalence of PSH (Bharucha & Khatri, Citation2018; Anwar et al., Citation2019; Ahmad et al., Citation2020), and show its harmful effects: PSH limits women’s presence in public spaces and their ability to pursue education and employment (Borker, Citation2021; Chakraborty et al., Citation2018; Siddique, Citation2018), undermines their mental health (Talboys, Citation2015), and contributes to early marriage (Nahar et al., Citation2013). These negative consequences likely will be reflected in gender disparities in education, labour force participation, occupational segregation, and health at the societal level.

South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa are characterised as the region of ‘classic patriarchy’ (Kandiyoti, Citation1988), where female dependency and male guardianship are practiced through rigid division of labour in the household and segregation of sexes in public spaces. Under the unwritten rules of classic patriarchy, male family members police the behaviour of wives, daughters, sisters (often through the direct supervision of older women in the family) to preserve the honour of the family while women are expected to practice modesty and acquiesce to the restrictions on their movement. While there are variations within the wide swathe of the patriarchal belt, research on Morocco and Pakistan shows how discriminatory sociocultural practices and representations of women that are enacted and reproduced in the family, schools, media, and legislation might promote and sustain violent behaviour by men, including PSH (Chafai, Citation2017; Khan, Citation2020). This argument is consistent with findings of a systematic review of qualitative research on sexual harassment in lower – and middle-income countries, which highlights the importance of cultural context, such as the role of patriarchal norms on the normalisation of GBV and gender inequalities (Hardt et al., Citation2023). Moreover, where social norms that restrict women’s access to public spaces are increasingly challenged by the growing number of women who step out of the social and familial boundaries to participate in the labour force and pursue their education, especially in urban areas (Hossain, Citation2017), PSH may represent a backlash against what is perceived as a breach of rules of classic patriarchy. In the context of rising religious conservatism (Ilahi, Citation2009), the harassment may also take on religious overtones, as some harassers in Egypt claimed harassment as their right when women defy strict interpretations of religious texts by not staying home (Henry, Citation2017).

In all three countries, workplace or public space sexual harassment is a crime, punishable by imprisonment and fines. The Indian Penal Code, revised in 2013, outlaws sexual harassment, stalking, voyeurism (SafeCity India, Citation2022). In Bangladesh, while there is no specific law on PSH or legal term sexual harassment, the behaviours that constitute PSH fall under certain provisions of Bangladesh laws (Dhaka Tribune, Citation2022). In Pakistan, workplace and public-space harassment of women is outlawed under section 509 of the Pakistan Criminal Penal Code and the Protection Against Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act of 2010 (Jatoi, Citation2018). Yet, enforcement of these legal provisions is limited or missing, as the women who are harassed do not bring up formal complaints and when they do, the police do not take it seriously – both these responses being conditioned by the normative acceptance or tolerance of PSH. When no prosecution cases are brought under the law, the law fails to act as a deterrent. The result is that women’s silence, poor redressal mechanisms, and bystander indifference perpetuate harassment.

Literature review: Men’s perspectives on PSH

Studies on men’s views on PSH are rare (Fairchild, Citation2023). The few studies on the global South examined the mindset of perpetrators of PSH. The study by Zietz and Das (Citation2018) in two slum communities of Mumbai, India, examined the perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs of adolescent boys and young men regarding PSH. In focus-group discussions, participants admitted that they sexually harassed women, even as they acknowledged that this was a form of violence. Most participants also viewed their communities as unsafe for girls and women due to PSH, an outcome to which they contributed. By delineating a vague category of ‘bad girls’ based on community gossip and narratives related to the behaviour of the girl and her social status, young men gave themselves license to harass women and girls they deemed bad. Participants reported that their low socio-economic status was an obstacle to both intervening as bystanders and reporting to the police because of potential retaliation from the police or the community, especially if a higher-status male was the perpetrator.

In Egypt, the ‘self-professed’ harassers from different socio-economic strata in the study by Henry (Citation2017) also blamed the victims: they faulted female victims’ appearance and actions; viewed PSH as an act of punishment for women’s desire to seek employment outside the home and compete with men for jobs; and claimed that by not staying home and walking alone, women were violating religious proscriptions. Participants also viewed harassment as not harmful, and lacked empathy for victims, which suggests that male socialisation normalises and justifies harassment. In addition, they thought that harassing women was part of the oppression experienced by everyone in Egyptian society which, according to Henry (Citation2017), suggests that men may be harassing women to compensate for feeling emasculated. PSH may thus be men’s public response to their perceived loss of sole breadwinner status, akin to the sharp increase in domestic violence when women took up factory employment in Bangladesh (Kabeer, Citation1999).

It is also possible to gain insights into why men engage in harassment from studies on women’s experiences of PSH. A study of female university students in Islamabad, Pakistan, included questions on widely held ideas about why men engage in PSH (Ahmad et al., Citation2020). Respondents strongly disagreed that men harass women because they dress inappropriately but strongly agreed that men think it is fun to scare a vulnerable group in society and that they won’t be punished.

Research on causes of other forms of sexual violence and men’s behaviour as bystanders in those cases may also provide insights on men’s views on and responses to PSH. Focus groups and surveys about perceived causes of workplace sexual harassment at a large urban university in Jordan indicate multi-level causes (including social norms, university environment, and individual socialisation) and victim blaming (Bergenfeld et al., Citation2022). Both men and women respondents identified women’s breach of social norms as causes of sexual harassment. Men and women students also identified male peers as enablers of sexual harassment, PSH as a form of bonding or showing off, underscoring the lack of perceived seriousness of such behaviours by men. Qualitative research by Edwards et al. (Citation2024) shows that young men are generally intolerant of GBV in theory, but also justify violence in certain contexts. Justifications are rooted in paternalistic views, for example, if a woman fails to fulfill expectations within a relationship. Other justifications included intent (i.e. just a joke) or victim-blaming.

Men could also play an important role in intervening when they witness PSH. In the global North, bystander intervention is viewed as a key instrument for bringing about a shift in the culture that normalises PSH (Fairchild, Citation2023). Research on men as bystanders and what motivates them to intervene mostly focuses on intervention in cases of sexual assault or workplace sexual harassment (Labhardt et al., Citation2017). The few studies on bystander intervention in instances of PSH examine women’s perspectives. Fileborn (Citation2017) reports that women in her Australian study experienced few instances where bystanders intervened. The first study of bystander behaviours in the Latin American context, Lyons et al. (Citation2022) focuses on sexual harassment in the workplace in Ecuador. Based on an online survey of university staff and students, Lyons et al. show that people who accept rape myths (that blame the victim) and those with higher previous perpetration experience had more difficulty intervening. With limited research on effectiveness of bystander approaches it is difficult to determine how relevant the findings from Latin America or the global North are for the design of interventions in South Asia. The ‘SAFE-ACTIONS Bystander Intervention Framework,’ informed by promising practices from the global South, highlights the importance of adapting interventions to varying cultural norms about gender expectations (Lee & Golwalkar, Citation2023).

In this study, we fill some of the gaps in the scant literature on men’s perspectives of PSH in terms of the extent to which men view PSH as a problem, are witnesses to harassment, what motivates or restricts them to intervene, how they respond to the harassment of their family members, and the gender norms they hold.

Materials and methods

We recruited men from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan to complete an online survey consisting of a structured questionnaire, Survey of Men’s Perspectives on PSH, 2021–2022. This cross-sectional exploratory survey was administered in 2021–2022 using slightly tailored country-specific questionnaires. The Bangladesh and Pakistan surveys included two open-ended questions to elicit how reducing harassment of women would impact participants’ lives and proposed solutions to eliminate PSH. We added these questions after implementing the survey in India and feedback from research collaborators in Bangladesh and Pakistan. We used snowball sampling via email or social media invitation that originated with academic and community partners in each country. In India, the Public Health Department at Amity University in New Delhi, the National Dental College in Punjab, and the Mehar Baba Charitable Trust in Punjab initiated the recruitment. In Bangladesh, recruitment was initiated through the Asian University for Women in Chittagong, and in Pakistan, it was through Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). Communication included emails with digital links, fliers, text via phones, and social media (Facebook and WhatsApp). The University of Utah Institutional Review Board IRB_00134270 approved this study.

Key measures in the questionnaire included the prevalence of men’s experiences as witnesses to PSH, how they responded, barriers to intervening, whether they took precautionary or restorative steps for female relatives who experience PSH, and, if they did, the extent to which they bore monetary or time costs for these steps. We also assessed their attitudes about women’s behaviours and mobility in public to explore the gender norms that they and the men in their community held. We devised a gender-norm scale in the questionnaire by adapting existing standardised instruments, including the Gender Role Beliefs Scale (GRBS) (Kerr & Holden, Citation1996) and questions on the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (DHS Program, Citation2021), and adding questions to align with our study’s focus on public-space sexual harassment of women. To explore whether men justified or condoned PSH we inquired about their views on legal and community sanctions against harassers.

Study limitations are non-random sampling, small sample size, the online survey format, and potential social desirability bias. The small sample size limited our ability to disaggregate results by men’s socio-economic status. The data collection method of snowball sampling via social media may have yielded a selection bias in the sample population, as participants are likely to share the survey with others with similar opinions or experiences. Likewise, the online survey format, necessitated by COVID-19 restrictions, likely excluded specific groups without easy internet access or those not active on social media platforms. As a result, we do not claim generalisability of the results. The online format also limited further exploration of responses to open-ended questions and those that relate to gender norms, which are prone to social desirability bias. Nonetheless, our sample provides insights into the views of a relatively privileged group of men about PSH, which facilitates exploratory analysis of an under-researched aspect of PSH and lays the groundwork for further explorations.

Results

Demographic summary

A total of 237 men aged 17–46 years participated in the survey. Participants were drawn from the Delhi National Capital Region, Chandigarh, Patiala, Sirhind, and Fatehgarh Sahib in India; Dhaka, Chittagong, Sylhet, Khulna, Noakhali, Comilla, and Coxsbazar in Bangladesh; and Lahore, Islamabad, Karachi, Peshawar, and Quetta in Pakistan. Across countries, the sample is relatively homogeneous and characterised as young, unmarried, highly educated urban dwellers. About half were students (54.4%), and most (83.1%) were from middle – to high-income households ().

Table 1. Characteristics of survey participants.

Men’s experiences: Witnessing and responding to PSH

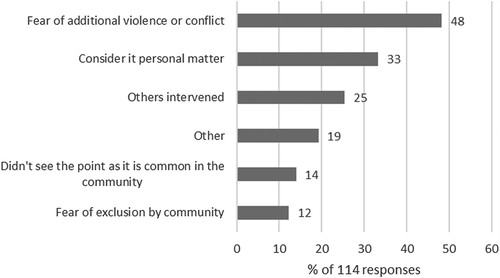

Overall, in the pooled sample of the three countries, 53% of men reported witnessing PSH, and most men reported intervening in incidents of PSH (). A non-negligible minority, 19%, indicated they never intervened with the modal reason for not intervening (48%) being fear of escalation of violence ().

Figure 1. Reasons for not intervening as a bystander. Note: The numbers do not add to 100%, as respondents were allowed to select more than one option. ‘Other’ includes instances when they learned about the harassment too late, or they were young at the time, or heard about it second hand later, were too busy at the time or unable to stop what they were doing, such as driving. Source: Survey of Men’s Perspectives on PSH, 2021–2022.

Table 2. Experiences of PSH.

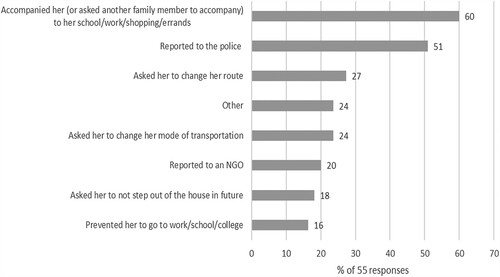

A small share of respondents (9%) considered their neighbourhood unsafe and 15% reported that most men they know perceive their neighbourhood as unsafe (). These low figures are not surprising, given the relatively affluent background of the respondents. PSH is likely more prevalent beyond their neighbourhood, which may explain the high rates of reported worry about PSH. In the pooled sample, 88% of men reported being worried about PSH. Respondents reported that most men they know are worried to a similar extent about PSH, 35% reported being aware of an incident of PSH experienced by a female family member, and 80% reported taking some action in response (). Among those who reported acting, as shown in , the most common step was to accompany, or ask someone else to accompany her to school/work/shopping/errands to avoid PSH, which is the expected response from men as guardians of women relatives according to the gender norms in South Asia. The second most frequent action was to report the incident to the police. Other steps included asking their relative to choose a different route, a different mode of transportation, to not step out of the house in the future, and to prevent her from going to work/school/college (the last taken by about one-fifth of respondents). These responses lay bare how gender norms that give men the right to control women’s behaviour (as the flipside of men’s responsibility to protect them) may constrain women’s education and employment prospects.

Figure 2. Actions in response to PSH experience of a female family member. Note: The numbers do not add to 100%, as respondents were allowed to select more than one option. ‘Other' includes confronting the harasser, providing emotional support to the victim. Source: Survey of Men’s Perspectives on PSH, 2021–2022.

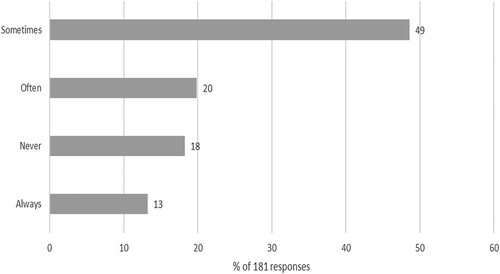

Respondents also reported taking preemptive measures to keep their female family members safe, distinct from taking such steps after a family member was harassed. The most common of these steps (for 82%) was again to accompany them in public spaces (). Nearly half of those respondents accompanied their female relative ‘sometimes,’ which was the most common practice (). Overall, 19% of respondents prevented female family members from going to school/work preemptively because they felt it would be unsafe due to likely PSH ().

Figure 3. Accompanied a female family member to school/work/shopping/errands to avoid PSH. Source: Survey of Men’s Perspectives on PSH, 2021–2022.

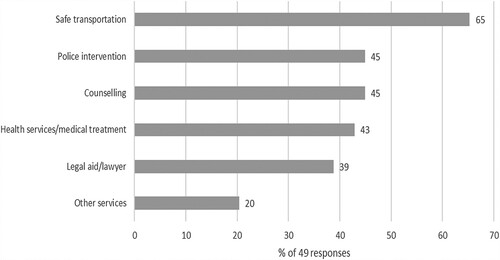

A small share of respondents mentioned using services such as safe transportation, police intervention, counseling, health services, and legal aid ().

Figure 4. Services used in response to PSH experience of a female family member. Note: The numbers do not add to 100%, as respondents were allowed to select more than one option. Other services include family support and reporting to the social/community head. Source: Survey of Men’s Perspectives on PSH, 2021–2022.

Overall, 65% of men reported being aware of resources intended to protect women such as helplines for women, public service banners, NGOs, or government agencies (), which suggests there is scope to enhance awareness about these resources. The use of these resources by the respondents or someone they know is low across all three countries (). These statistics indicate that even if resources to help women are available, and a large share of men are aware of them, the usage is limited.

Costs of PSH for men

The results suggest that most men in the survey have borne at least some time cost for dealing with PSH: 82% accompany their female family member in public spaces preemptively, and 60% did so (or asked another family member to do so) after their relative experienced harassment. When asked about time cost involved for taking action, 97% of 116 respondents answered in the affirmative (). Given that 93% of respondents are either employed or students, such time commitment by a large share of men to deal with PSH would translate into at least some loss of productivity in these countries. In addition, a small share of respondents – 72% of 46 respondents – reported incurring a monetary cost to deal with incidents of PSH experienced by their female family members ().

Men also bear emotional costs, which we glimpse in their responses to the open-ended survey question: If harassment no longer existed, how might your life change? A majority of the respondents described positive effects, some of which were in unspecific or general terms, such as ‘freedom,’ ‘peaceful,’ ‘beautiful,’ and ‘comfortable.’ Our question was about the impact of PSH on men personally, and the most common sentiments confirmed positive benefits for men. They also described benefits to women and society at large, possibly because they see improvements for women as an important and beneficial factor for themselves. Many responses highlighted wider benefits, as illustrated by this common sentiment:

‘I as well as all of the persons in the world like me will be free from stress of harassment about their family and the world will be equally livable to both male and female.’

‘It would relieve me of the constant tension as women of the family have to go out for study, work, shopping or entertainment [on a] daily basis and there is always this fear of any such unpleasant incident to take place.’

‘I would no longer be afraid of having a female child’

‘If harassment no longer exists women would trust men more … ’

‘(W)e [men] will go outward with pride.’

‘ … It'll add productivity to our society, somewhere I believe a lot of females and males don’t reach their potential and skill level because they fear harassment … .’

‘More meritocracy, increased innovation.’

‘Girls will be safe always … . because girls are my sister, mother, aunties and my future life partner also’

Men’s views about patriarchal gender norms

We explored men’s views on patriarchal gender norms based on categorical responses to the following statements concerning women’s behaviour: women should not interact with male strangers in public spaces; women should dress modestly to avoid harassment in public spaces; a girl/woman should drop out of school/work if she experiences any harassment in public spaces; women should not be allowed to step out of the house alone; women should not be allowed to stay out of the house after it is dark; it is a woman's fault if she is subject to any harassment in public spaces; a girl/woman should not disclose/report an incident of harassment in public spaces because it would bring shame on her/her family. Most of these gender norms concerning women’s behaviour in public spaces are also commonly held views that place the blame for harassment on women. We also inquired whether perpetrators of PSH should face legal and community sanctions in order to capture respondents’ views about men’s license to harass women.

We asked respondents to indicate what they thought about each statement above and whether ‘most men they know’ would agree with them. We hypothesise that the latter could capture the gender norms held by men in society, though not necessarily held by the respondents. Given the topic of gender norms, it is highly likely that men’s responses regarding their own views are susceptible to social desirability bias, whereby participants self-report in a socially acceptable manner instead of providing answers that reflect their own views (Labhardt et al., Citation2017). By asking them about the views of ‘most men’ we anticipate the respondents could report not only their perceptions of views of men they know but also express their true feelings about a statement without worrying about social desirability.

The responses in and indicate a substantial prevalence of patriarchal views in the sample. The three most prevalent views are: (1) women should dress modestly to avoid harassment in public spaces (40% agreed); (2) women should not interact with male strangers in public spaces (42% agreed); and (3) women should not be allowed to stay out of the house after it is dark (37% agreed). Moreover, 75% of respondents hold at least one discriminatory gender norm and the prevalence of these views in the community is potentially more extensive, given that this statistic rises substantially – to 91% – when men report their perceptions of views held by most men they know.

Table 3a. Gender norms held by respondents.

Table 3b. Perceptions about patriarchal gender norms held by most men the respondent knows.

Lower shares of our respondents think girls’/women’s freedom to attend school or office should be restricted if they experience harassment (12%); explicitly blame girls/women for the harassment they experience (10%); think girls/women should not report PSH incidents as it would bring shame on them/their family (10%) (). These answers suggest that our sample of mostly young, educated men holds some ‘enlightened’ gender-related attitudes, which is contrary to research that indicates that education reproduces gender-unequal attitudes, especially among men (Kane & Kyyro, Citation2001). We believe that there may be an element of social desirability bias in these responses: Some answers may reflect the stereotypical perspectives of an educated man in South Asia. Again, these statistics rise substantially for most men our respondents know (), which suggests that these patriarchal views are widely held by men in the community.

Most respondents indicate that men who engage in PSH should face legal and community sanctions. Only 9% of respondents disagree that men who engage in harassment in public spaces should be punished by law, and 20% disagree that besides law, there should be some form of community-level action against men who engage in any sort of PSH. In the Bangladesh and Pakistan surveys, we probed further through an open-ended question: ‘In your opinion, what (if anything) should be done to stop harassment?’ The most common suggestions called for enforcing existing laws, updating laws, and assuring strict and swift justice. The following views are illustrative:

‘The culprits should be punished immediately and strongly, create awareness about the laws and charges on harassment.’

‘Punishment and public shaming, news, and pictures of harasser to be posted on social media and news channels, shared by large number.’

‘Fear of God and strict adherence to the teachings of Islam.’

‘Women should dress appropriately when leaving the house which should not expose any of their skin which might cause disturbance to them in the future. They should choose to dress in a very decent manner keeping in view their physique and body type.’

‘Teaching self-defense to women, educating the children (boys and girls) at school levels to know and understand how to prevent harassment.’

‘Raise gender equality, make public awareness for harassment, and make strict law against woman harassment.’

‘Educate men and promote the role of women in public places.’

Conclusions

Discussion

Our survey sample of mostly young, single, highly educated urban men of middle-income backgrounds in India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan provided insights on their experiences with PSH (as witnesses and relatives of women who experience PSH), the burden of PSH for them, and their views of gender norms that underlie and perpetuate PSH. Half the survey participants reported having witnessed PSH, and about 80% reported having intervened in these instances. The main reason for not intervening was fear of provoking further violence, which is not surprising, given the well-publicised cases, at least in India, where men who accompanied women were assaulted by harassers (Dhillon & Bakaya, Citation2014).

A substantial share of respondents (88%) reported worrying about PSH. About a third were aware that a female family member experienced PSH, and 80% took some action to deal with its consequences. Their most common response was to accompany the family member in public spaces. Even without such incidents, 82% accompanied female family members preemptively. Other preventive or restorative actions in response to PSH (keeping their female relative home and away from school or work) provide insights on male control over female relatives’ behaviour as the mechanism that may underlie the adverse education and employment outcomes of PSH documented in statistical studies (Borker, Citation2021; Chakraborty et al., Citation2018). Coupled with the high endorsement of beliefs (self and particularly ‘other men’) that women should modify their behaviour to avoid harassment, these responses indicate heavy costs of PSH for women.

Men also bear costs of PSH. Nearly all (97%) respondents reported that they bore at least some time cost for taking preventive or restorative actions to help their female relative, which would translate into at least some loss of productivity in these countries in addition to the far-reaching adverse consequences of PSH for women. A much smaller share also reported monetary costs. The responses to the open-ended question about the anticipated impact of curbing PSH on men’s lives reveal that men also bear emotional costs under the status quo, as they worry about the safety of their female family members. Their responses underscore that PSH imposes spillover costs on the family members of women who are harassed.

Despite their awareness of the costs of PSH and their acknowledgement of widespread gains from curbing PSH, most participants adhered to at least one patriarchal gender norm that is widely believed to contribute to PSH in South Asia. While most disagreed with restricting women's attendance in school or work or blaming them for the harassment they may experience, the opinions were mixed on whether women should interact with male strangers in public spaces, dress modestly, or be allowed to stay out after dark. Respondents reported that most men they know are substantially more conservative than themselves, which suggests that this question provides a more accurate gauge of the intensity of patriarchal gender norms in these countries than respondents’ own views registered in the survey.

Given the relative homogeneity of our sample, we are unable to explore how socio-economic background could affect these findings. Yet, based on our findings and existing scholarship, we can infer that recognition of and response to PSH may be easier for well-off men. Men in our sample have more means to incur costs for protection of their relatives; they can arrange for safe (private) transportation or more easily take time off to accompany their relatives, compared to less-privileged men. With fewer means to escape, female relatives of less-privileged men will be less secure in public spaces, as supported by Ilahi (Citation2009). Socio-economic background also likely affects ability to intervene as bystanders. While most of our respondents intervened when they witnessed PSH marginalised men may be intimidated by the police or the community, especially when harassers are powerful men (e.g. Zietz & Das, Citation2018). Less-privileged men (women) may also be less likely to report such incidents since reporting GBV (more broadly) can be both expensive and time-intensive (Khan, Citation2020).

Research and policy implications

Our exploratory study is one of the first to examine men’s perspectives on PSH in South Asia – their views on patriarchal gender norms that are often cited as justifications for PSH, how PSH of women affects their lives, and what can be done to address PSH. The majority of respondents holds at least one patriarchal gender norm, which is at odds with their awareness of the harms of PSH that are perpetuated and justified by these gender norms. This dissonance is consistent with research that shows individuals justify GBV in a variety of situational contexts, even though they oppose it in principle or are aware that their harassing behaviours are wrong (Edwards et al., Citation2024; Zietz & Das, Citation2018). Our study lays the groundwork for future research (and educational programs), which could probe this cognitive dissonance, and develop a deeper understanding of the social and cultural factors that foster violent attitudes and subject women to harassment, as called for by Khan (Citation2020) and Chafai (Citation2017).

We also highlight the need for larger-scale representative data collection. For example, questions to probe PSH should be included in representative national and international surveys, such as DHS. This would allow researchers to fill a gap identified in our work, namely, how men’s (and women’s) experiences and responses to PSH may vary by socio-economic status and other social identities. Future work could also query the sensitive issue of men’s experiences as perpetrators of PSH, inquire in greater depth about their bystander experiences and their thoughts on how they could be part of the solution to reduce PSH.

Most respondents agreed that men who engage in harassment should face legal sanctions, which along with transforming norms, are the most common measures identified for combatting PSH in the scholarship on South Asia (Bharucha & Khatri, Citation2018; Madan & Nalla, Citation2016). While many mentioned education and awareness raising, these were rather general and somewhat ambiguous suggestions, which did not indicate respondents’ awareness of the connection between the patriarchal gender norms they hold and the widespread incidents of PSH about which they were worried, and which generated costs for them.

Our findings support interventions suggested by previous studies on GBV (and PSH) on the need for tackling gender norms through a multi-pronged approach, at both the macro level, targeting policymakers, the legal environment, and NGOs and the micro level, through work with families, local communities, and by directly engaging men (Mitchell, Citation2013; Bergenfeld et al., Citation2022; Chafai, Citation2017; Khan, Citation2020). The micro-level interventions could include school curricula that promote ideas of equality and discourage discrimination, harassment, and violence; and community-based education that targets both men and boys and women and girls to raise awareness about GBV and its consequences and challenge the deep-rooted gender norms, power imbalances, and societal expectations that allow violence to continue. Programs aimed at boys and men could include training them to call out the harassing behaviours as bystanders to disrupt the normalisation of PSH. As our findings and previous scholarship indicate, however, men are less likely to intervene if they blame the victim, fear an escalation of violence, or have been perpetrators. These potential obstacles must be considered in the design of bystander approaches.

Awareness programs that target men and boys could also include legal literacy and awareness about resources. We found in our sample that while men indicated they are aware of the availability of resources to help women their reported utilisation was low. Therefore, in addition to public outreach about the availability of institutional resources to help women deal with PSH, support of and easier access to such resources could help strengthen their impact. Nevertheless, failure to utilise such resources may continue to be low due to institutional failure to take the charges seriously and/or the limited enforcement or awareness of existing legal provisions.

Therefore, these micro-level interventions could be completed by strengthening sanctions against PSH at the macro level (Stark et al., Citation2020). Legislation that criminalises PSH must be implemented and enforced, including challenging views that minimise the severity of PSH (Ribeiro, Citation2024), taking all complaints, regardless of perceived severity, seriously (Bergenfeld et al., Citation2022), and adopting a zero-tolerance approach against perpetrators (Madan & Nalla, Citation2016). While we did not probe the respondents’ dealings with the police when they reported incidents of PSH, their relatively low reliance on police and evidence from previous studies on South Asia suggest that legal reforms should encompass effective police response.

Research on effectiveness of policing to reduce PSH indicates the relevance of incorporating gender egalitarian values in their design and effectiveness. Experimental evidence from India has found that a visible police presence reduces severe forms of PSH and as a result, also improves women’s mobility (Amaral et al., Citation2023). Researchers also found a reduction in both mild and severe forms of harassment among police units that hold more gender-egalitarian views. Yet, Raman and Komarraju (Citation2018) show the limits to the effectiveness of first-responder police teams. While they are helpful in mainstreaming conversations about violence against women, they operate in a patriarchal framework of surveillance and control of women and fail to address the underlying contextual issues behind such violence, and in fact, may contribute to perpetuating patriarchal discourse and men’s control over women. Promoting egalitarian gender norms in the wider community as well as in law enforcement is therefore a tangible option for primary prevention.

The time, monetary, and emotional costs of PSH for men also suggest a public-awareness campaign strategy that speaks to men’s self-interest as a potential focus. When men realise that they bear a collective burden due to the prevalence of PSH, they are more likely to join as allies of women and intervene to eliminate this wicked problem.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mahima Elahi and Wasima Alam Choudhury in Bangladesh, Dr. Vijul, Dr. Rohini Dua, and staff of Mehar Baba Charitable Trust in India, and Armughan Hafeez in Pakistan for their assistance in implementing the survey, Yihao Qin and Tejashree Prakash for their research assistance, and our survey respondents for their time and attention. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the University of Utah VPR 1U4U Interdisciplinary Seed Grant Award, February 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adur, S. M., & Jha, S. (2018). (Re)centering street harassment – An appraisal of safe cities global initiative in Delhi, India. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1264296

- Ahmad, N., Masood, M. M. A., & Masood, R. (2020). Socio-psychological implications of public harassment for women in the capital city of Islamabad. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971521519891480

- Amaral, S., Borker, G., Fiala, N., Kumar, A., Prakash, N., & Sviatschi, M. M. (2023). Sexual harassment in public spaces and police patrolling: Experimental evidence from urban India. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, Working Paper 31734 https://www.nber.org/papers/w31734.

- Anwar, F., Österman, K., & Björkqvist, K. (2019). Three types of sexual harassment of females in public places in Pakistan. Çağdaş Tıp Dergisi, 9(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.16899/gopctd.468324

- Bergenfeld, I., Clark, C. J., Sandhu, S., Yount, K. M., Essaid, A. A., Sajdi, J., Abu Taleb, R., et al. (2022). There is always an excuse to blame the girl’: Perspectives on sexual harassment at a Jordanian university. Violence Against Women, 28(14), 3457–3481. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012221079373

- Bharucha, J., & Khatri, R. (2018). The sexual street harassment battle: Perceptions of women in urban India. The Journal of Adult Protection, 20(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-12-2017-0038

- Borker, G. (2021). Safety first: Perceived risk of street harassment and educational choices of women. The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 9731. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/723631626710146405/pdf/Safety-First-Perceived-Risk-of-Street-Harassment-and-Educational-Choices-of-Women.pdf.

- Chafai, H. (2017). Contextualizing street sexual harassment in Morocco: A discriminatory sociocultural representation of women. The Journal of North African Studies, 22(5), 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2017.1364633

- Chakraborty, T., Mukherjee, A., Rachapalli, S. R., & Saha, S. (2018). Stigma of sexual violence and women’s decision to work. World Development, 103, 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.10.031

- Demographic and Health Survey Program. (2021). DHS8: Module on domestic violence questionnaire. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSQM/DHS8-Module-DomViol-Qnnaire-EN-12Nov2021-DHSQM.pdf.

- Dhaka Tribune. (2022). “FACTBOX: What Bangladesh’s Laws Say about Sexual Harassment of Women.” April 5 https://www.dhakatribune.com/crime/2022/04/06/factbox-what-bangladeshs-laws-say-about-sexual-harassment-of-women.

- Dhillon, M., & Bakaya, S. (2014). Street harassment: A qualitative study of the experiences of young women in Delhi. SAGE Open, July-September, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014543786

- Doyle, K., & Kato-Wallace, J. (2021). Program H: A review of the evidence: Nearly two decades of engaging young men and boys in gender equality. Equimundo. https://www.youthpower.org/resources/program-h-review-evidence-nearly-two-decades-engaging-young-men-and-boys-gender-equality.

- Edwards, C., Bolton, R., Salazar, M., Vives-Cases, C., & Daoud, N. (2024). Young people’s constructions of gender norms and attitudes towards violence against women: A critical review of qualitative empirical literature. Journal of Gender Studies, 33(1), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2022.2119374

- Fairchild, K. (2023). Understanding street harassment as gendered violence: Past, present, and future. Sexuality & Culture, 27(3), 1140–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-09998-y

- Fileborn, B. (2017). Bystander intervention from the victims’ perspective: Experiences, impacts and justice needs of SH victims. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 1(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1332/239868017X15048754886046

- Fileborn, B., & O’Neill, T. (2023). From ‘ghettoization’ to a field of its own: A comprehensive review of street harassment research. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(1), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211021608

- Hardt, S., Stöckl, H., Wamoyi, J., & Ranganathan, M. (2023). Sexual harassment in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(5), 3346–3362. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221127255

- Hebert, L. E., Bansal, S., Lee, S. Y., Yan, S., Akinola, M., Rhyne, M., Menendez, A., & Gilliam, M. (2020). Understanding young women’s experiences of gender inequality in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh through story circles. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1568888

- Henry, H. M. (2017). Sexual harassment on Egyptian streets: Feminist theory revisited. Sexuality & Culture, 21(1), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9393-7

- Hossain, N. (2017). The Aid lab: Explaining Bangladesh’s unexpected success. Oxford University Press.

- Ilahi, N. (2009). Gendered contestations: An analysis of street harassment in Cairo and its implications for women’s access to public spaces. Surfacing: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Gender in the Global South, 2, 56–69.

- Jatoi, B. (2018). Sexual harassment laws in Pakistan. 8 February. The Express Tribune https://tribune.com.pk/story/1628822/sexual-harassment-laws-pakistan.

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Kandiyoti, D. (1988). Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender & Society, 2(3), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002003004

- Kane, E. W., & Kyyro, E. K. (2001). For whom does education enlighten?: Race, gender, education and beliefs about social inequality. Gender & Society, 15(5), 710–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015005005

- Kerr, P. S., & Holden, R. R. (1996). Development of the gender role beliefs scale (GRBS). Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11(5), 3–16.

- Khan, U. (2020). Gender-based violence in Pakistan – A critical analysis. Master's thesis. Harvard Extension School. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/37365403.

- Labhardt, D., Holdsworth, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. D. (2017). You see but you do not observe: A review of bystander intervention and sexual assault on university campuses. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 35, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.05.005

- Lee, J., & Golwalkar, R. (2023). A. Agarwal (Ed.), Bystander intervention framework. EngenderHealth. https://www.engenderhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Bystander-Internvetion-Framework-FINAL.pdf

- Lyons, M., Brewer, G., Caicedo, J. C., Andrade, M., Morales, M., & Centifanti, L. (2022). Barriers to sexual harassment bystander intervention in Ecuadorian universities. Global Public Health, 17(6), 1029–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1884278

- Madan, M., & Nalla, M. K. (2016). Sexual harassment in public spaces: Examining gender differences in perceived seriousness and victimization. International Criminal Justice Review, 26(2), 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057567716639093

- Misri, D. (2017). Eve-teasing. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 40(2), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2017.1293920

- Mitchell, R. (2013). Domestic violence prevention through the constructing violence-free masculinities programme: An experience from Peru. Gender & Development, 21(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.767516

- Nahar, P., Van Reeuwijk, M., & Reis, R. (2013). Contextualising sexual harassment of adolescent girls in Bangladesh. Reproductive Health Matters, 21(41), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(13)41696-8

- Raman, U., & Komarraju, S. A. (2018). Policing responses to crime against women: Unpacking the logic of Cyberabad’s “SHE Teams”. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 718–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1447420

- Ribeiro, B. (2024). Will boys always be boys? The criminalization of street harassment in Portugal. Violence Against Women, 30(6-7), 1431–1452. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778012221150276

- SafeCity India. (2022). What are the important laws governing sexual harassment in public spaces in India?” https://www.safecity.in/faq/what-are-the-important-laws-governing-sexual-harassment-in-public-spaces-in-india/.

- Shahid, R., Sarkar, K., & Khan, A. (2021). Understanding “rape culture” in Bangladesh, India, & Pakistan. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/southasiasource/understanding-rape-culture-in-bangladesh-india-pakistan/.

- Siddique, Z. (2018). Violence and female labor supply. IZA Discussion Paper No. 11874. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3273713.

- Stark, L., Seff, I., Weber, A., & Darmstadt, G. L. (2020). Applying a gender lens to global health and well-being. Framing a Journal of Global Health special collection. Journal of Global Health, 10(1), 010103. PMID: 32257130.

- Talboys, S. L. (2015). The public health impact of eve teasing: Public sexual harassment and its association with common mental disorders and suicide ideation among young women in rural Punjab, India (Doctoral dissertation). The University of Utah.

- Verma, A., Qureshi, H., & Kim, J. Y. (2017). Exploring the trend of violence against women in India. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 41(1-2), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924036.2016.1211021

- Zietz, S., & Das, M. (2018). Nobody teases good girls’: A qualitative study on perceptions of sexual harassment among young men in a slum of Mumbai. Global Public Health, 13(9), 1229–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1335337