ABSTRACT

There are many examples of poor TB infection prevention and control (IPC) implementation in the academic literature, describing a high-risk environment for nosocomial spread of airborne diseases to patients and health workers. We developed a positive deviant organisational case study drawing on Weick’s theory of organisational sensemaking. We focused on a district hospital in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa and used four primary care clinics as comparator sites. We interviewed 18 health workers to understand TB IPC implementation over time. We included follow-up interviews on interactions between TB and COVID-19 IPC. We found that TB IPC implementation at the district hospital was strengthened by continually adapting strategies based on synergistic interventions (e.g. TB triage and staff health services), changes in what value health workers attached to TB IPC and establishing organisational TB IPC norms. The COVID-19 pandemic severely tested organisational resilience and COVID-19 IPC measures competed instead of acted synergistically with TB. Yet there is the opportunity for applying COVID-19 IPC organisational narratives to TB IPC to support its use. Based on this positive deviant case we recommend viewing TB IPC implementation as a social process where health workers contribute to how evidence is interpreted and applied.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

In high tuberculosis (TB) burden countries, the airborne spread of TB in healthcare facilities places both health workers and patients at risk, and disproportionally affects those most vulnerable to developing severe disease (Uden et al., Citation2017). This hazard is extensive: in South Africa TB has been the leading cause of death, with health workers falling ill with TB disease at a three times increased rate compared to the general population (Department of Statistics South Africa, Citation2020; Uden et al., Citation2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, as airborne precautions became an increasingly important part of the pandemic response, there was an opportunity to consider airborne infection prevention and control (IPC) implementation as a multi-disease intervention combining the emergency COVID-19 response and ‘routine’ care for diseases such as TB (van der Westhuizen et al., Citation2022).

Implementation of TB IPC across health facilities in South Africa and in other high TB burden countries is generally described to be poor (Colvin et al., Citation2021; Engelbrecht et al., Citation2018; Farley et al., Citation2012; O’Hara et al., Citation2017). This failure may be due to TB IPC requiring multiple components of an effective airborne IPC programme to be implemented simultaneously. This includes administrative controls (triage and the use of isolation and respiratory hygiene for people with TB symptoms or disease, as well as prompt initiation of effective treatment), environmental controls (ventilation and upper-room germicidal ultraviolet systems) and use of personal protective equipment (World Health Organization, Citation2019). These components interact to influence the risk of nosocomial airborne disease transmission making this a complex intervention (van der Westhuizen et al., Citation2022).

Arakelyan and colleagues argue that TB IPC efforts should move beyond using a checklist approach to monitor implementation, and instead incorporate ethnographic methods (Arakelyan et al., Citation2022). Their research focussed on six primary healthcare clinics in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, and described how dimensions of the ‘enabling environment’ such as infrastructure, resources and organisational constraints interact. They noted that while some of the system hardware components (such as IPC protocols, committees and champions) were available in principle, they were not implemented in a meaningful way. One clinic was the exception, where they noted the influence of supportive senior management and good working relationships between staff in facilitating TB IPC improvements.

Kallon and colleagues explored the contribution of organisational culture to mask-wearing practices for TB in six primary healthcare facilities in South African (Kallon et al., Citation2021). They found that mask-wearing was impacted by perceptions during social interactions, that health workers tended to normalise TB risk and viewed it as an individual risk rather than collective responsibility. In this case study we develop this organisational focus further by predominantly focussing on a district hospital.

The setting for this research is the rural Eastern Cape of South Africa, which has the highest annual TB disease incidence rate in the country at 692 per 100,000 people (Kanabus, Citation2021). The local municipalities are some of the most deprived areas in South Africa, with only 8.5% of the population over 15 years employed and 72% of the population needing to collect water from a river (Wazimap, Citationn.d.). While many descriptions of the rural areas in South Africa draw strongly on measures of deprivation, there are also conceptualisations of how rural areas may develop resilience through using relationships to identify, recruit and utilise resources (Ebersöhn & Ferreira, Citation2012). Ebersohn and colleagues researched rural schools in South Africa and proposed viewing relationships as discs of systemic strength, like a honeycomb, that enable agency that can challenge the depiction of rural areas as ever-widening circles of deficit (Ebersöhn & Ferreira, Citation2012).

In this study, we develop an in-depth understanding of an organisation where TB IPC as a bundle of interventions was implemented well, an example of what Flyvbjerg calls a ‘positive deviant’ case study (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006). While Arakelyan and colleagues briefly discussed a positive case example of a primary care clinic in their study, this approach has not received in-depth focus in TB IPC research (Arakelyan et al., Citation2022). Flyvberg’s method examines in-depth context-dependent knowledge – what allows people to become virtuoso experts in a field rather than knowledge based on rule. Flyvbjerg argues that focussing on a deviant provides rich information that could deepen understanding useful in different settings and demonstrates that positive deviation from the usual is possible.

We use Weick’s theory of organisational sensemaking as it starts from the premise that organisations have environments that are in flux, and that organisational narratives reflect interpretations of this environment, but also help to shape or ‘enact’ the environment (Weick, Citation1995). Our research aims are to explore: (1) How organisational sensemaking theory can help to explain a positive deviant case of TB IPC implementation at a health facility. (2) How implementing TB IPC prepared the organisation for the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

The study design used an organisational case study approach, drawing on the interpretive case study method of Stake, with detailed, naturalistic and longitudinal observation of events and relationships, including thick descriptions and narrative extracts (Stake, Citation1995). Our primary unit of analysis is a rural district hospital – it includes the infrastructure, the staff and patients who use the hospital and local policies that influence the hospital’s way of work. We also conducted interviews at four primary care clinics based in the same area, to contrast different IPC organisational practices in the same geographic area, while keeping our focus on the district hospital. Pseudonyms for the health facilities are used to promote confidentiality.

Context

Mamele hospital was selected as a positive outlier for good TB IPC practices based on provincial audit data. It delivers services to a catchment area of approximately 130,000 people and has 150 beds. The hospital delivers outreach support to 14 primary healthcare clinics in the surrounding area, of which four were comparator study sites for this research (Aphiwe, Camago, Fassi and Khumbula clinics). Key differences between the district hospital and primary care clinics are size and organisational structure: the district hospital has a CEO and clinical manager, with a multi-disciplinary team of health professions including allied health workers, doctors and nurses. The primary care clinics are nurse-run, have between 6 and 12 staff members, and ranged from having newly renovated facilities to old infrastructure. The primary healthcare clinics were selected for maximum variation (considering distance from district hospital, physical infrastructure, patient load and TB incidence based on number of TB referrals sent to hospital).

Data collection

Data sources include in-depth individual interviews with 18 health workers conducted between 2019 and 2020 which lasted between 30 and 90 min each. We also used fieldnotes, policy document reviews and reviews of IPC audits. During 2021 we approached all participants for remote follow-up interviews and conducted this with the six health workers who expressed interest, all were based at the hospital. Sampling was purposive, specifically including health workers who played key roles over time in developing TB and COVID-19 IPC systems in the hospital. Interviews were audio recorded and conducted in isiXhosa or English, transcribed and translated into English where applicable, and checked for accuracy by the research team. This study formed part of a broader programme of research that also included interviews with patients and a specific focus on stigma and IPC, which will be reported elsewhere.

Data analysis

Initial analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, using line-by-line coding with NVivo software (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We then looked to develop an understanding of how the organisation made sense of airborne IPC as an intervention over time, using narrative summaries of key informants and creating a narrative overview.

We draw on Weick’s theory of organisational sensemaking as theoretical approach to understand TB IPC implementation (Weick, Citation1995). Weick recommends a literal definition of sensemaking – referring to a process that is both an individual and social activity of making sense. When applied to organisations, it refers to the way members of an organisation interpret their environment in and through interactions with others, which then leads to collective action (Weick, Citation1995). We use the seven properties of sensemaking (in italics below) that Weick described and apply it to TB IPC implementation in these facilities.

The seven properties include how organisational sensemaking is grounded in identity construction, which involves establishing and maintaining identity. We approached this component by considering – what do health workers perceive a ‘good’ professional should do with regards to TB IPC implementation in their setting? Sensemaking is retrospective, which involves occasions for sensemaking that interpret events and processes that could either support or hinder TB IPC implementation. Examples would be what health workers view the results of their TB IPC actions or lack of action to be. Sensemaking is enactive of sensible environments, meaning it shapes the environment and the way health workers think about TB IPC as intervention. This includes how they conceptualise ‘effective’ TB IPC for their context. Sensemaking is social, meaning it is influenced by the opinions of others and constructed between people in a way that may be contested and negotiated. Sensemaking is ongoing, which implies that for our in-depth case it would be important to gauge how the process of sensemaking has adapted over time. Sensemaking involves using extracted cues, and looking at how these are interpreted at an organisational level. We draw on this when sharing what participants felt key milestones were in TB IPC implementation. Sensemaking is driven by plausibility rather than accuracy. With this, Weick means that accuracy (for example, the most effective place to target TB IPC measures) is helpful but not necessary for sensemaking. What is more important is to get some interpretation to start with, instead of waiting for ‘the’ definitive interpretation to arrive. We selected this theoretical approach to help understand the social processes of TB IPC implementation that are distinctive to the positive deviant organisational case study and contrast examples of guided organisational sensemaking where there is a unitary rich account, with fragmented sensemaking (Maitlis, Citation2005).

The research team was led by HvdW, a clinician-researcher who had previously worked in the facilities, with co-investigators bringing expertise in occupational health (RE), primary care (CB and TG), behavioural science (STC) and sociology (TG). A research assistant familiar with the area received two days’ training in qualitative research methods and mentorship during the study. She supported recruitment and led the isiXhosa interviews.

Ethics

The study was approved by the research ethics committees at the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences (HREC REF: 259/2019) and the University of Oxford (Oxtrec number: 541-19). It received institutional permission from the Eastern Cape Department of Health (EC_201907_010) and local permissions from health facilities.

Results

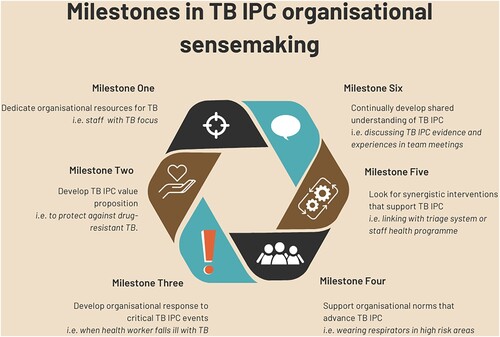

We start by introducing TB IPC implementation narratives at the comparator primary care clinics and consider why these did not lead to comprehensive TB IPC implementation. We then introduce our positive deviant case study of the district hospital with additional details about the rural context and six key milestones that staff identified as important in their collective sensemaking. We present an in-depth narrative from the clinical manager, who played a key role in this process, which we describe as leadership sensegiving. Finally, we look at how organisational sensemaking was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how these new disease transmission narratives can translate to TB IPC.

For a summary of participant characteristics, including the number of health workers interviewed at primary care facilities compared to the district hospital, see .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

TB IPC implementation narratives at primary care level

The following four primary care facilities show fragmented narratives of organisational sensemaking of TB IPC implementation. They represent narrow approaches that focus on a specific subcomponent of TB IPC. Our impression was that their activities aimed to demonstrate some compliance, at times at significant resource costs, but that TB IPC did not seem to have substantive broader value for the organisations and therefore implementation fell short.

Organisational narrative 1 based on Aphiwe Clinic: In this facility health workers decided not to use masks or respirators for TB as they felt patients experienced this as stigmatising. The health worker’s bare face was seen as a visual manifestation that they do not find patients ‘disgusting’ and did not need a protective barrier. This links with identity construction of professional norms for what a ‘good’ health worker should do, which in this context they interpreted as avoid making patients feel stigmatised. The TB service was run by a nurse who previously had TB, which the other health workers felt meant he could relate more closely to the patients. The risk of recurrent TB for this health worker was not considered. They did not routinely open windows. Their overarching narrative about TB IPC was that it was not practical as they were thwarted by poor facility infrastructure (comprised of a temporary prefab structure and hut) which led to overcrowded, poorly ventilated indoor waiting areas when patients had to wait inside when it rained. They felt that unless they received a new facility, TB IPC implementation was beyond their influence.

Organisational narrative 2 based on Camago Clinic: This facility has been recently renovated and had purpose-built coughing booths for sputum collection and windows that can open widely. Their main TB IPC focus was to fast-track people with positive TB laboratory results. The designated TB and HIV nurse would alert the facility administrator that a person’s TB diagnosis was positive, give a surgical mask for the patient when they arrived at the facility and let them skip the queue. The health workers did not use respirators, arguing that they had managed to avoid falling ill with their current practices thus far, an example of retrospective sensemaking. Their overarching narrative about TB IPC was that it should be targeted towards people with a positive TB diagnostic test but who had not yet started treatment.

Organisational narrative 3 based on Fassi Clinic: This facility rotated their TB focal nurse every three months to share the TB risk staff faced. The facility’s IPC efforts were targeted towards separating patients who had been diagnosed with TB. There was an important visual manifestation of TB IPC, where TB patients used a separate area of the clinic: they had a separate waiting area, vital signs room, and medication dispensing pathway. This reflected a deeper shared assumption that known TB patients posed the infection risk. However, staff did not apply this to the use of protective equipment. Masks and respirators were only viewed as needed for patients with drug resistant TB, who were rarely seen at the clinic. Respirators which had been out of stock for three months would appear in time for audits to avoid a negative evaluation. This incongruent response, localising infection risk to known TB patients through having a separate patient flow system but health workers not using respiratory equipment, could reflect a fatalistic approach to the TB risk to health workers or a belief that drug-sensitive TB was not as severe.

Organisational narrative 4 based on Khumbula Clinic: During the site visit, two junior nurses were working on their own. The location was isolated with very poor road infrastructure and limited mobile reception. They described receiving an instruction from their clinic manager that all patients visiting the facility, irrespective of symptoms, should receive a mask and the nurses should also wear surgical masks as PPE. Yet there were no surgical masks in stock at the facility for health workers or patients. They felt the only tool they could use was to ask patients to cover their cough with a scarf or their hand. They felt that the power relations with the clinic manager meant that they feared engaging their manager about the implications of the mask directive and did not have influence over stock-outs. One of the junior nurses (participant 27) summarised their overall work experiences as: Things are not happening here. The narrative of the nurses around TB IPC in this facility was that despite junior staff having significant organisational responsibilities, it was yet another requirement they had insufficient support to execute.

These organisational narratives describe a patchwork of TB IPC measures. The starting point for this is that the bundle of TB IPC measures did not always convince health workers of its relative advantage over not implementing it. Where TB was not considered a significant threat to the health of health workers, or if health workers were fatalistic about their TB risk, IPC measures were less persuasive. This scepticism may also be due to the outcomes of poor TB IPC implementation being less observable since it could take two years or longer for a health worker to fall ill with TB after being exposed. A health worker may also choose not to disclose this to their colleagues, which would omit this from the organisation’s narrative. This results in fewer cues for organisational sensemaking on the importance of TB IPC. These focussed conceptualisations of what TB IPC implementation entailed in each primary care setting were incomplete, and seldomly accompanied by a strategy to progressively expand implementation.

A positive deviant case for sensemaking on TB IPC implementation

As an introduction to the district hospital, Box 1 describes the rural setting and process of being screened for TB.

‘Mamele hospital is easy to spot – it is the biggest conglomeration of buildings for kilometres, with huts dotting the surrounding hills. Taxis speed past, hooting at goats, chickens and sheep to clear the way. The hospital entrance is a large, well-ventilated atrium with wooden benches. Patients slowly shuffle their way through one queue to the administrative clerks to collect their hospital number. They then shuffle down the next queue to have their vital signs taken. Blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, oxygen saturation. Then the next queue shifts to a different line of benches, this time to discuss their presenting problem with a nurse. If someone is visiting the hospital for emergency care, they receive a triage colour. This is the point where the nurse also screens for TB symptoms. If a patient is coughing, has night sweats and is losing weight, they go directly to TB Point, instead of queuing to see the doctor. At TB Point, the TB nurse directs them to the corrugated iron coughing booth outside to take a sputum sample that is sent to the on-site laboratory. Then it is time to wait. First for the TB results, then to see the doctor, then to collect medication. Amagwinyas [deep fried fat cakes] are for sale at the tuck shop across the road. On the grassy embankment next to the hospital entrance, gogos [elderly women] unfurl the blankets that they wear around their waist and use head wraps as pillows to prepare for a nap. A hospital visit starts early and can take the whole day.’ – Description of a Mamele hospital visit, field work journal 2019

The narratives among health workers and patients about generally providing good patient care also included TB IPC, with participants describing how they score ‘green’ on audits. This corresponded with our fieldnotes: in general, patients visiting the facility were screened for TB, surgical masks were offered to people with a cough. There were rosters for opening windows in different hospital areas and the waiting area had large doors on either side that were kept open, cross ventilating the most crowded area in the hospital. Health workers obtained particulate filter respirators distributed through the pharmacy, and frequently used them in the wards and in the out-patient department.

At Mamele hospital, in contrast to the primary care clinics, the process of TB IPC organisational sensemaking was guided by the organisation’s leadership (using training sessions for staff, and formal policies to support TB IPC) and through peer influence (for example by seeing the practices of other health workers in the same team), while adapting the process based on iterative feedback. Health workers at Mamele hospital described TB IPC implementation as an unstructured ‘journey’ mirroring the 15-year trajectory of improving care at the facility.

Prior to developing a deliberate strategy to implement TB IPC, the organisation focussed on strengthening the TB care that was provided to patients:

TB had become this thing that we wore as a badge of pride as South Africa – the highest rates – something that was part of life. And then suddenly it was something that we should probably do something about. That's as simple as the change was at first. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

Milestone 1: Dedicated organisational resources earmarked for TB through ‘TB Point’

A consulting room, called TB Point, was set up where a member of the nursing staff coordinated all components of TB care. This provided dedicated resources within the organisation for TB, and later TB IPC. Since 2007, TB Point had been led by a nurse who had developed occupational TB herself. She described her organisational role as champion for TB:

They [the health workers] must change their attitudes. They must like TB, just like any other disease. I know all my patients. Because I like TB very much as I like myself. Don't treat people as if [they’re] not a human being. The sister from one hospital said, “ I don't like this TB. They just put me [there] because there is no one [else].” TB is not like that. [Where] you stay, you walk, we must speak of TB. You must love it. – participant 13, Mamele hospital, nurse, previous TB

Milestone 2: A clear relative advantage becomes evident for TB IPC

A treatment programme for drug-resistant TB at Mamele was initiated by the hospital at the beginning of decentralised management of drug-resistant TB in South Africa in 2011 (South African National Department of Health, Citation2011). The clinical manager described how the success of the drug resistant TB treatment programme depended on using TB IPC to reduce the risks of infection and allay staff and community fears about its transmission. The tension for change for introducing TB IPC grew as the value proposition focussed on preventing drug-resistant TB infection. This likely shifted perceptions of the relative advantage of TB IPC. TB IPC was also combined with drug-resistant TB care as a new manifestation of identify construction for health workers – where a ‘good health worker’ strives to provide more comprehensive care at the district hospital, instead of referring patients to a distant specialist TB hospital.

Milestone 3: Tension for change reaches a critical level

When one of the health workers at Mamele developed occupational TB, the clinical manager viewed this as an observable consequence of inadequate TB IPC at an organisational level, not an individual error attributable to the health worker. They used it as a cue for further action:

When we got our first audiology booth, we'd test the hearing of our drug resistant TB patients. And the next thing our audiologist had TB. But she wore a mask. What we hadn't appreciated was that the booth wasn't ventilated. If there was a moment she didn't have a mask on, at the point of opening the booth, that was really where it was going wrong. We thought we were doing infection control and then realised, hold on a moment [there are gaps]. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

Milestone 4: TB IPC becomes normalised

Several health workers described a gradual change in the organisational norms at Mamele hospital, from seeing very few health workers wearing a respirator, to one where most health workers would wear a respirator when providing TB care – initially most often in the TB wards:

I remember the first two years people really were not really thinking about [TB]. And a lot of nurses didn’t wear masks. But we did a lot of health education and support. As part of the orientation programs, we tried to get people to wear masks. For the last five years I honestly cannot remember when last I told a healthcare provider “where’s your mask?” – participant 4, Mamele hospital, doctor

Milestone 5: TB IPC becomes further embedded, and aligned with new interventions

Participants described three interventions that were introduced to improve overall quality of care, that were then aligned to TB IPC. Firstly, access to novel molecular diagnostics at the on-site hospital laboratory reduced the turnaround time for TB test results from multiple days to six hours. This made it feasible to isolate people with potential TB until their diagnostic result became available. Prior to this the hospital would not have had sufficient isolation space. Using TB diagnostic tests for timely IPC decisions required negotiating about when specimens were taken from the hospital to the laboratory to facilitate this faster turnaround and how TB tests were prioritised by laboratory personnel.

Secondly, a triage system for patients visiting the outpatient department was introduced to differentiate between people requiring routine or urgent care. Screening for TB symptoms was added to the triage form that was used for all patients, which helped identify patients who may pose a risk of TB transmission to others in the general waiting areas:

Initially we didn’t have a triage system. Everyone used to walk in and it used to be first come first serve – unless you were an emergency. Everyone used to sit in line – we used to just say ‘next’ and then whoever came in, came in. We introduced a triage system and TB symptom screen – sending people through TB Point. People had been pre-identified and removed [from the general queue]. It was better for the patients in the line. And it was better for us because someone walked in with a mask and you’re like ‘okay this is TB’ and then you could put your mask on straight away. They’d usually already had a GeneXpert so you could check for results. – participant 33, Mamele hospital, doctor

The third synergistic intervention was the development of a dedicated staff occupational health clinic. This provided organisational resources to screen staff for TB. At the facility, baseline and then annual chest X-rays was offered through the staff health clinic. This likely also contributed to awareness among health workers that they were at risk of occupational TB.

These three examples describe an organisational context for change that was receptive to the introduction of different innovations. It required viewing TB IPC implementation as an ongoing process that required finding linkages beyond the core elements of TB IPC, and offered scope for adapting the intervention as the broader system also underwent changes.

Milestone 6: There is a continually developed, shared understanding of TB IPC among staff

At a clinical team meeting in 2018, the clinical manager presented research that showed people with TB became rapidly less infectious after 48 h of effective TB treatment (Dharmadhikari et al., Citation2014). The study used TB rates in guinea pigs: one group was exposed to air from rooms of patients with TB before treatment was started and another group was exposed to air from the rooms of patients after TB treatment was started. The guinea pigs exposed to patients who were already on effective treatment had much lower rates of TB. At the team meeting, health workers discussed the application of this finding to who poses the biggest risk of infection in the facility and decided to isolate the patients most likely to do so (for example waiting for a TB test result not yet on treatment) instead of TB patients already on treatment for multiple weeks.

Well, who's actually the dangerous patient? … Sometimes you just need to get enough momentum. I think our high-risk coughing room was that. … We'd been talking about it for a while, but there was pushback. There were [health workers who said,] “No, we're scared of TB”. And it took a while before people [shifted from]: we are scared of TB. That's good. But who's got TB [and poses an infection risk]?” Suddenly - once that penny dropped - it was amazing. … The idea that you could have a TB patient in the general ward [who is still on treatment but not infectious any longer] and not have nurses up in arms about it is incredible. The crucial difference is this change from ‘TB is bad’ to ‘infection risk is bad’. That understanding of infection control has helped. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

The role of ‘leader sensegiving’ in TB IPC organisational sensemaking

Box 2 provides an in-depth reflection from the facility manager about the process of TB IPC implementation.

‘I’ve often described what we're trying to do here as starting the conversation around X, Y or Z. There are multiple role players and different opinions. It's a process of changing head knowledge into belief. Realising there isn't a quick fix. It becomes part of the way you do things. If you're wanting to address TB you need to start to talk about TB and develop a consensus – but also just find the people who are interested. There are a couple of people who will [it] find academically interesting, or they've got a relative who had TB. And once you've got a couple of people you're having a conversation and you're not just the town crier. Once you're getting momentum, then the question is – what small things can we do better? Because it is a journey, change management isn't about arrive, sing and dance, fireworks, leave and it's all fine. No. Even when you do it carefully, when you stop, it starts to regress. Everything we do is about continual education of ourselves, our colleagues and our patients. Find what are the small things that you can do better. Just opening windows – that's a big one. It's easy to do and it's difficult to start. Just focus on opening the windows because – once the windows are open you've done two things: 1) you've opened the windows, but 2) you've created enough awareness to have the windows open. And then you're thinking – what's next? Can we order N95’s? Yes okay. When should we wear them? Who should wear them? How long should you wear them? Then do a bit of education. Make sure patient flow in your facility is right and that's the undiagnosed patients, but also the TB patients who are coming back. And then education. Staying up to date with what's happening and generating some enthusiasm around it. I think if TB's left to that old burnt-out [medical officer] or the nurse who's been here forever and it happens in the dark corner office – then it doesn’t move forward. But now TB is dynamic. There's never been a better time to be interested in TB. I often say pick your battles wisely. What do you have the capacity for? How long are you going to be around? Some changes take years. Don't pick a year's kind of change when you're only going to be [at the facility] a couple of months, because you won't achieve it. And then you'll feel disillusioned.’ – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

The clinical manager spoke about the process of introducing an innovation as ‘starting or changing the conversation’ around TB IPC. By changing the conversation, the way people think or feel about TB IPC is slowly influenced, which in this case study, contributed to a receptive environment for TB IPC. It also embraces the social component of sensemaking, where a shared meaning of what effective TB IPC would entail is constructed between people.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a major shift in how TB IPC was implemented at Mamele hospital. The following section presents insights on how IPC changed in 2021.

COVID-19 IPC as an example of fragmented organisational sensemaking

Participants described how the COVID-19 pandemic challenged Mamele hospital in unexpected ways, testing the core values of the organisation. Health workers described a heightened sense of isolation when the referral hospital stopped their outpatient clinics, ambulances were slower to respond to calls, and social grant offices closed causing severe economic hardship and impacting patients’ ability to afford transport to visit the hospital.

There was a breakdown in trust between colleagues, trust in the leadership of the organisation and trust in the ability of guidelines to protect health workers. This became a traumatic time for many health workers at Mamele, with one commenting, The strengths that we had before were lost … [Hopeful attitude] imploded, exploded. – participant 30, Mamele hospital, doctor.

While these health workers worked in a health system that was under chronic strain prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the acute strain of COVID-19 heightened uncertainty and fear. Many disagreements focussed on IPC:

The tension in this hospital was palpable. It was heavy. It was everywhere. It was permeating. Cloth masks became the symbol of this stress. There were definite lines drawn amongst different groups. There were factions in the hospital … The mask became a uniform of one of the teams and the bare face became the uniform of the other. – participant 30, Mamele hospital, doctor

At Mamele hospital during that time we had massive [nursing and general worker] strikes - the worst we’ve ever seen - over PPE - the whole [hazmat] suit. There was just a heightened awareness and anxiety and fear, but it almost made people really illogical. – participant 4, Mamele hospital, doctor

Our journey was really difficult: from an organisational culture point of view, from a trust point of view with staff, for me personally, politically within the hospital environment, and in my role as clinical manager. Suddenly it felt like nobody trusted anybody and there were wild rumours about all sorts of things including the virus itself, but also what the agenda of management was. Suddenly everyone wanted to wear PPE as if they were going to the moon and rational thought left the building. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

COVID-19 providing new organisational IPC narratives useful for TB

At the time of the follow-up interviews in 2021, health workers identified many opportunities to integrate COVID-19 and TB prevention and care, including testing patients presenting with a cough for both diseases. COVID-19 also led to the repurposing of TB resources: the drug-resistant TB ward was converted into a COVID-19 ward, and all the drug-resistant TB patients were discharged home. This also had symbolic meaning – the most feared infectious disease, drug-resistant TB, was being replaced by COVID-19.

Staff described how, during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the focus of the entire organisation had shifted to COVID-19, deprioritising TB and not linking the two illnesses together:

One of the great ironies of COVID in South Africa is that, because it's been a pandemic and it has implications for developed economies, we paid a lot more attention to COVID than we've ever paid to TB. I’m not sure that it's been a better experience, but it's bizarre that we've poured so much money into PPE for COVID, managing spaces and trying to identify patients early. It’s not scientifically justifiable really. … given that TB kills so many people in our country … TB had that journey– trying to highlight TB as something that was both potentially dangerous to staff and preventable. That was a mindset shift. COVID on the other hand was going to kill everyone dead 10 seconds after it arrived in South Africa and the level of panic and fear was completely insane. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager

The first new narrative was the use of airborne IPC measures for people with no symptoms of illness:

COVID is TB's twin, but with a different set of rules. Let’s forget what you know [about TB]: that in order to be sick you have to lose weight and then wear a mask and to be identified [as someone with TB] through the mask. Let’s just say anyone can have it and then what will we do?. – participant 31, Mamele hospital, allied health worker

The second new narrative was that universal mask-use in health facilities was feasible. Participants described that initially mask availability was a challenge – the increase in demand could not be met through hospital provision of masks to all patients, health workers and visitors. As time passed, more patients brought their own cloth masks, eventually leading to a situation where everybody in the hospital setting would wear a cloth or surgical mask.

It continually blows my mind that within the hospital every single person is wearing a mask. You know, all our patients. How powerful is continuous messaging? It's amazing. We used to look to Asia where mask wearing for pollution was common. And just think, how would we ever adapt to that? And then here we are. – participant 12, Mamele hospital, manager.

Discussion

This organisational case study examined TB IPC implementation at a rural district hospital in South Africa as a positive deviant case and included experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that TB IPC implementation was approached as a multi-year process, continually adapted based on available resources, drawing on perceptions of the relative advantage of using TB IPC and other synergistic interventions (such as triage processes and staff occupational health). This was strengthened by viewing implementation as a social process, where health workers could contribute to how evidence is interpreted, valued and applied.

As Flyvberg describes, a positive deviant case firstly shows that the intervention is possible, and then helps to generate insights that could inform positive case examples in other settings (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006).

In Box 3 we consider which insights may be transferable from our positive deviant case findings.

1. Look for opportunities where TB IPC can be aligned with the organisational identity being constructed, for example TB IPC being part of providing higher quality services.

2. Create occasions for sensemaking that interpret key events (a health worker getting organisational TB) and processes (naming of an isolation cubicle) that could support TB IPC implementation.

3. Focus on ‘starting or changing the conversation’ around TB IPC. This is likely a more productive approach to changing IPC practices, compared to viewing health workers as passive recipients to be ‘filled’ with the correct knowledge.

4. View TB IPC as a shared, social practice, where effective TB IPC for that setting needs to be negotiated between people by discussing key pieces of scientific evidence.

5. Existing ways in which TB IPC is conceptualised, can change. Implementation strategies should account for this.

6. TB IPC prioritisation often centres around health worker perceptions of occupational TB risk, which could be one extracted cue for sensemaking.

7. The process of TB IPC implementation should be an ongoing conversation, where the aim is to reach a shared understanding driven by plausibility.

As part of the sensemaking process, critical questions that the organisation engaged with were: Where should IPC resources be directed? Where are high risk areas for transmission? How should occupational risk to health workers be communicated? These questions have been raised in different settings, with little detail on how they may be resolved (van der Westhuizen et al., Citation2022). Kallon and colleagues used organisational culture as guiding framework and described primary care settings in the Western Cape, where health workers chose to localise risk to certain clinical areas in the facility where patients known with TB were attended to, neglecting patients who may have TB but were not on treatment (Kallon et al., Citation2021). Our case study describes how this was overcome, through a shift in how health workers came to think about risk as present anywhere in the health facility. While this approach was still contested by different health workers, there was sufficient consensus to facilitate a shift in how TB IPC resources were being used.

Kallon and colleagues also described how mask-wearing was seen as individual choice, informed by a health worker’s perception of risk and assumption of responsibility should they fall ill with TB (Kallon et al., Citation2021). This contrasted with a stronger emphasis on organisational responsibility in this district hospital dataset. When a health worker fell ill with TB, the cause was sought in their working environment and not blamed on the individual. There was a collective approach to inducting new members into accepting the organisation’s TB IPC norms, and TB IPC was linked to staff health programmes.

Existing research about supporting TB IPC implementation has included participatory theatre as educational tool (Parent et al., Citation2017), personal narratives of HCWs affected by TB (van der Westhuizen et al., Citation2015), and educational games and TB awareness campaigns (Haeusler et al., Citation2019). Our findings have a different emphasis – on TB IPC as a process of collective organisational sensemaking – which has implications for TB IPC training for health workers. Instead of covering content that emphasises adherence to guidelines and the use of checklists to audit implementation, training should include discussions about organisational values, negotiating complexity and individual versus collective responsibility.

The social component of IPC implementation was also prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time of the interviews, opportunities for achieving synergy between COVID-19 and TB IPC were not taken up. Participants mentioned uncertainty due to changing guidelines, an atmosphere strikingly similar to the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic globally, including as described in Australia (Broom et al., Citation2022).

In this case study, strong TB IPC implementation was not sufficient preparation for COVID-19 IPC, as the fragmented sensemaking of COVID-19 IPC contrasted with the guided sensemaking of TB IPC that was characterised by a series of broadly compatible actions. This raises questions for pandemic preparedness. If a pandemic strains critical resources for resilience, such as relationships between health workers and organisational trustworthiness, what could be put in place as preparation? How can uncertainty around transmission, debates about supporting evidence and changes in IPC guidelines be managed in a more supportive way? And how can TB IPC programmes incorporate new sensemaking from COVID-19 IPC, particularly around managing asymptomatic transmission through universal mask wearing? This would be valuable to explore in future IPC research.

Our study had important limitations. A case study of a single organisation enabled us to provide in-depth insights but does not provide a representative overview of TB IPC implementation in all district hospitals. Our data collection from the primary care facilities had smaller numbers of participations per facility and did not have a similarly in-depth focus. Further observational and ethnographic work would have strengthened this study. This was planned but limited by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the sample of follow-up interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic was small and limited by a lack of observational data and to one facility, it can provide only provisional insights.

Conclusion

This organisational case study represents a positive deviant: a facility that, over a multi-year journey, developed successful strategy for TB IPC implementation. By drawing on Weick’s work on sensemaking in organisations, we identified features of this process that could support TB IPC efforts in other organisations. This would involve viewing TB IPC, and IPC more broadly, as a process of organisational sensemaking, where implementation is a social process and health workers can contribute to how evidence is interpreted and applied. Due to the strain on relational resources within the organisation, COVID-19 IPC posed significant implementation challenges at this site, but also presented new narratives on IPC implementation which could be utilised for TB IPC in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people who supported the research: Ncumisa Somdyala, Dr Karl Le Roux, Dr Nadisha Meyer and Catherine Young. We deeply appreciate the contributions of the health workers who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arakelyan, S., MacGregor, H., Voce, A. S., Seeley, J., Grant, A. D., & Kielmann, K. (2022). Beyond checklists: Using clinic ethnography to assess the enabling environment for tuberculosis infection prevention control in South Africa. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(11), e0000964. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000964

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Broom, J., Broom, A., Williams Veazey, L., Burns, P., Degeling, C., Hor, S., Barratt, R., Wyer, M., & Gilbert, G. L. (2022). One minute it’s an airborne virus, then it’s a droplet virus, and then it’s like nobody really knows … ’: Experiences of pandemic PPE amongst Australian healthcare workers. Infection, Disease & Health 27(2), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2021.10.005

- Colvin, C. J., Kallon, I. I., Swartz, A., MacGregor, H., Kielmann, K., & Grant, A. D. (2021). It has become everybody’s business and nobody’s business’: Policy actor perspectives on the implementation of TB infection prevention and control (IPC) policies in South African public sector primary care health facilities. Global Public Health, 16(10), 1631–1644. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1839932

- Department of Statistics South Africa. (2020). Mortality and causes of death in South Africa: Findings from death notifications in 2017. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932017.pdf

- Dharmadhikari, A. S., Mphahlele, M., Venter, K., Stoltz, A., Mathebula, R., Masotla, T., van der Walt, M., Pagano, M., Jensen, P., & Nardell, E. (2014). Rapid impact of effective treatment on transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 18(9), 1019–1025. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.13.0834

- Ebersöhn, L., & Ferreira, R. (2012). Rurality and resilience in education: Place-based partnerships and agency to moderate time and space constraints. Perspectives in Education, 30(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.38140/pie.v30i1.1730

- Engelbrecht, M. C., Kigozi, G., Janse van Rensburg, A. P., & van Rensburg, D. H. C. J. (2018). Tuberculosis infection control practices in a high-burden metro in South Africa: A perpetual bane for efficient primary health care service delivery. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 10(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1628

- Farley, J. E., Tudor, C., Mphahlele, M., Franz, K., Perrin, N. A., Dorman, S., & Van der Walt, M. (2012). A national infection control evaluation of drug-resistant tuberculosis hospitals in South Africa. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 16(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.10.0791

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Haeusler, I. L., Knights, F., George, V., & Parrish, A. (2019). Improving TB infection control in a regional hospital in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMJ Open Quality, 8(1), bmjoq-2018-000347. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000347

- Kallon, I. I., Swartz, A., Colvin, C. J., MacGregor, H., Zwama, G., Voce, A. S., Grant, A. D., & Kielmann, K. (2021). Organisational culture and mask-wearing practices for tuberculosis infection prevention and control among health care workers in primary care facilities in the western cape, South Africa: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212133

- Kanabus, A. (2021). Information about Tuberculosis. GHE. https://tbfacts.org/tb-statistics-south-africa/.

- Maitlis, S. (2005). The social processes of organizational sensemaking. The Academy of Management Journal, 48(1), 21–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20159639

- O’Hara, L. M., Yassi, A., Bryce, E. A., van Rensburg, A. J., Engelbrecht, M. C., Zungu, M., Nophale, L. E., & FitzGerald, J. M. (2017). Infection control and tuberculosis in health care workers: An assessment of 28 hospitals in South Africa. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(3), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.16.0591

- Parent, S. N., Ehrlich, R., Baxter, V., Kannemeyer, N., & Yassi, A. (2017). Participatory theatre and tuberculosis: A feasibility study with South African health care workers. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 21(2), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.5588/ijtld.16.0399

- South African National Department of Health. (2011). Policy guideline: Management of drug-resistant TB. https://www.nicd.ac.za/assets/files/MANAGEMENT of drug resistant TB guidelines.pdf

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research (1st ed.). SAGE publications.

- Uden, L., Barber, E., Ford, N., & Cooke, G. S. (2017). Risk of tuberculosis infection and disease for health care workers: An updated meta-analysis. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 4(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofx137

- van der Westhuizen, H., Dorward, J., Roberts, N., Greenhalgh, T., Ehrlich, R., Butler, C. C., & Tonkin-Crine, S. (2022). Health worker experiences of implementing TB infection prevention and control: A qualitative evidence synthesis to inform implementation recommendations. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(7), e0000292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000292

- van der Westhuizen, H., Kotze, J., Narotam, H., von Delft, A., Willems, B., & Dramowski, A. (2015). Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding TB infection among health science students in a TB-endemic setting. International Journal of Infection Control, 11(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v11i4.030.15

- Wazimap. (n.d.). Mbhashe Ward 19 Demographic information. Retrieved 18 January 2022, from https://wazimap.co.za/profiles/ward-21201019-mbhashe-ward-19-21201019/.

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3). Sage.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). WHO Guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2019/guidelines-tuberculosis-infection-prevention-2019/en/