ABSTRACT

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) continues to be a pervasive issue globally, and in Ethiopia, that harms women and challenges progress towards a more gender-equal society. Many interrelated social, economic, and cultural factors impact VAWG. Religion is a complex factor that can contribute to and act as a preventative measure against VAWG. Thus, faith-leaders have been identified as key actors in VAWG prevention. This study examines Ethiopian Evangelical faith-leaders transformative knowledge change following a Channels of Hope for Gender training intervention. Focus group discussions were conducted with faith-leaders from five different Evangelical Church groups. The results show that the faith-leaders’ experience of the Channels of Hope training challenged their gender norms and allowed them to enact relationship and community-level changes. Additionally, they demonstrated efforts and interest in generating change at the level of the Church. However, barriers remained to fully addressing VAWG and implement gender transformative learning more widely. Thus, we conclude that the Channels for Hope training is useful in generating mindset changes and improving relationship-level interactions, but that it requires a longer implementation timeframe and further support from other structures and interventions to achieve sustainable change to prevent VAWG.

Introduction

Violence against women and girls

Globally, about 736 million women have experienced some form of intimate partner or non-partner violence or abuse (UN Women, Citation2022a). According to the World Health Organization, violence against women and girls (VAWG) is defined as

‘any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life’ (World Health Organization, Citation2021).

All forms of gender marginalisation and inequalities contribute to VAWG. In this study, we have defined gender as the economic, social, and cultural factors associated with being male or female; gender equality as men and women having the same access to opportunities; and gender equity as being fair to both genders based on their needs (UNFPA, Citation2005). Several studies have shown that social and cultural ideas supporting continued gender inequality through patriarchal views, referring to the socio-political system in which men hold power, perpetuate VAWG (Heise, Citation1998; Le Roux & Palm, Citation2021b; Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020). In particular, a qualitative study in Ghana revealed that factors including the man’s prerogative to decision-making in the home, rigid and strict gender roles, the right to sex at the man’s choosing, and wife beating as a legitimate form of punishment contribute to VAWG (Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020). In addition to patriarchal norms, many other individual, social, community, and institutional factors intertwine leading to VAWG (Heise, Citation1998).

Religion is one such factor that can contribute to patriarchal views and VAWG (Le Roux & Pertek, Citation2022). In this research, we define religion as the normative order linked with a set of practices and beliefs in other realities (Rakodi, Citation2007; Schilbrack, Citation2013). The focus is on the implications of beliefs and structures rather than proving theological arguments (Rakodi, Citation2007; Schilbrack, Citation2013). Through this viewpoint, religion can be examined as both a protective and a risk factor for VAWG. Several studies have shown that religious influence or association with a religion can increase IPV occurrence (Le Roux & Palm, Citation2021a; Le Roux & Pertek, Citation2022; Takyi & Lamptey, Citation2020). However, simultaneously, studies have shown that religious affiliation or religious-based interventions can prevent or reduce VAWG (Boyer et al., Citation2022; Petersen, Citation2016; Zavala & Muniz, Citation2022). Thus, religion is a complex factor in VAWG that requires further examination in different settings.

VAWG and religion in Ethiopia

Over the past several decades, Ethiopia has been committed to tackling gender inequality with the 1987 constitution establishing equal rights for women and men, 1994 reforms to strengthen women’s empowerment, the 1997 constitution protecting women, the 1993 policy on women, the 2005 Family Law, and the ongoing Growth and Transformation plan (UN Women, Citation2022a). These laws have made progress to protect women against gender-based violence and improve women’s access to resources and positions of influence (UN Women, Citation2022b). Despite these positive recent changes, concrete change in the lives of women is more difficult due to limited enforcement of laws (UN Women, Citation2022b), poor accountability (Irish Aid & UN Women Ethiopia, Citation2016), and insufficient economic opportunities for women (Zeidane, Citation2018). Additionally, this rights-based strategy minimises the significant role that religious institutions play in shaping societal norms and behaviours in Ethiopia (Petersen, Citation2016).

Ethiopia is a highly religious country and, despite, many policy and societal changes, continues to have high rates of VAWG. According to the Ethiopian 2019 Demographic survey report, 98% of people report a religious affiliation with about 27% (appx. 30 million) affiliating with Protestantism/Evangelicalism (Ethiopian Public Health Institute et al., Citation2021). Concurrently, 34% of ever-married women in Ethiopia report a lifetime experience of IPV and the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime reported in 2020 that VAWG is still a serious problem fuelled by persistent gender-biased attitudes and practices (Ethiopian Public Health Institute et al., Citation2021; Negash, Citation2021; UNODC, Citation2020). Faith-leaders are thought to be useful change agents for other public health challenges, such as vaccination (Yibeltal et al., Citation2024). Consequently, Ethiopia has previously been identified as a country whereby faith-leaders and religion could be a tool for rhetoric change of VAWG (Boyer et al., Citation2022; Le Roux & Pertek, Citation2022; Sikweyiya et al., Citation2020). There have been some initial efforts to move beyond the rights-based discourse and engage with faith-leaders or faith-based organisations (Istratii, Citation2022; Negash, Citation2021). A project in the Tigray region, for example, has worked extensively with faith-leaders from the Orthodox Thawedo Church through a series of workshops to address domestic violence (Istratii, Citation2022).

However, it is also important to work beyond the dominant Orthodox faith, especially as Ethiopia has a growing Evangelical population (Haustein, Citation2011). The region where our study is based is Woliso, Oromia in South-East Ethiopia, which is 18.6% Evangelical (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission & UNFPA, Citation2008), and has the highest reported rate of spousal abuse, at 38.4%, in Ethiopia (Ethiopian Public Health Institute et al., Citation2021; Ministry of Women Children and Youth, Citation2019). Thus, it is important to understand and address VAWG and IPV within this population in order to generate change for women.

Gender transformative learning

Creating substantive change for women and reducing rates of VAWG is a complex process. The gender-transformative learning framework (GTLF) is a model for understanding gender equity efforts that shifts the focus from women changing their behaviour to collective responsibility and political engagement (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). The framework involves addressing agency, relations, and structure. Agency refers to individual and collective attitudes, reflections, actions, and access towards VAWG, harmful practices, traditional masculinity, and gender equality. Relations include the expectations and ways of negotiating dynamics between people such as controlling behaviour, the ability to negotiate in intimate relations, and freedom from violence. Lastly, structures are the formal and informal rules that govern people and society like tolerance of violence, community attitudes, employment policies, and mechanisms to respond to and prevent VAWG (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). The GTLF is useful for understanding how change can be made and to track how change has occurred.

Creating gender transformative change is a complex unpredictable process that requires influence and interventions from many sectors and actors (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). Faith-leaders have been identified as key actors in gender equality and VAWG prevention (Le Roux & Palm, Citation2021a). Several studies have shown success in using faith-leaders for gender transformative learning, including a three-year study with Christian and Muslim faith-leaders in the Democratic Republic of Congo that showed improved gender-equal attitudes and less tolerance for IPV, and a Ugandan study with Christian faith-leaders illustrated a shift in power and reduction in IPV prevalence (Kamanga & World Vision International, Citation2014; Le Roux et al., Citation2020). This study aims to understand Evangelical faith-leaders’ perspectives and experiences of an intervention to create transformative knowledge change and assess facilitators and barriers to congregation-level program implementation in Woliso, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design

This is a qualitative study evaluating the implementation of a gender transformative intervention from World Vision’s Channels of Hope for Gender (CoHG) model through focus group discussions (FGD). The project is part of a wider collaboration between the Ethiopian Graduate School of Theology (EGST) and Karolinska Institutet (KI) that aims to work with faith-leaders to address VAWG. The project involved three main parts: (1) a formative qualitative research study to understand the perspectives of faith-leaders (study 1) (Gobbo et al., Citation2023), (2) a follow-up with the faith-leaders to assess their gender transformative change and the integration of that knowledge into a series of faith-leader-led interventions to address VAWG (this study); and (3) an evaluation of the effects of the intervention on VAWG (study 3).

The CoHG is a transformational knowledge strategy rooted in guiding participants in understandings of Christian scripture (Bible) to shift away from a patriarchal perspective towards a gender-equal one (World Vision, Citation2014, Citation2015). The model mostly addresses the agency level of the GTLF by addressing faith-leaders’ attitudes and beliefs to then catalyse further gender change in relationships and structures. The ultimate goal of the CoHG model is to transform faith-leaders’ gender perceptions and to help them become agents of change within their respective communities. Several months after the intervention, the researchers returned to the faith-leaders to gather information on their perceptions and experiences of what they learned during the CoHG intervention and how they implemented what they learned in practice.

The CoHG intervention was completed as follows. In the fall of 2022, two workshops were conducted with faith-leaders by authors WB and MD from EGST. They are well-suited to conduct the training due to their backgrounds in Evangelical Theology, experience as trained and accredited facilitators of the CoHG model, and prior work in project planning and development. In November, a preliminary, one-day workshop was done with the most influential faith-leaders (Workshop #1). Then in December, a three-day CoHG workshop was held that used a series of exercises and action-based research to help the faith-leaders reexamine their attitudes through Christian theology (Workshop #2). The workshop includes the use of Biblical texts to debate the interpretation of scriptures in light of VAWG, fosters dialogue, and explores options as to how faith-leaders could address VAWG in their community (workshop agenda available in Appendix 1) (World Vision, Citation2014). Faith-leaders were then tasked to try and implement VAWG interventions within their congregations.

Study setting and study participants

The study took place in Woliso, Ethiopia which is a semi-urban area south-east of the capital Addis Ababa in the Oromia Regional State with a projectedFootnote1 2022 population size of 202,219 inhabitants (City Population, Citation2022; Unicef Ethiopia, Citation2022). Ethnically they are Oromo and Gurage, and linguistically they mostly speak Amharic and Afan Oromo (Ethiopian Public Health Institute et al., Citation2021).

The study participants invited to participate were all faith-leaders from seven different Evangelical Churches in Woliso. They were Workshop #2 participants who were faith-leaders who had the opportunity to address scripture, theology, or ethical issues by leading bible study, preaching, teaching, or other leadership roles. All participating Churches are under the umbrella of the Evangelical Churches Fellowship of Ethiopia, which aims to coordinate and facilitate amongst Evangelical members. Each of the seven Churches within this study has its own internal hierarchy that typically includes a collective leadership model with seven leaders appointed by the Church members (occasionally there is a one-man leadership). This is typically the main planning and event implementation body in the Church that makes financial and logistical decisions regarding the Church, in addition to their other spiritual responsibilities. These top leaders were the ones who participated in Workshop #1, and then recruited the other faith-leaders from their respective Churches to participate in Workshop #2.

Data collection

Data collection took place on May 29–31, 2023. Two data collectors (WB and MD) recruited faith-leaders who had previously participated in the CoHG intervention (Workshop #2) months earlier. We conducted five focus group discussions (FGD) with faith-leaders from five of the original congregations that participated. The FGDs were homogenous in the sense that they included members from the same Church. We used FGDs to explore faith-leaders’ perceptions of their experience of the intervention. FGDs were conducted because they allow for group discussion and reflection within an implementation team. The purpose of the FGD was explained, and verbal and written consent was obtained before a sound recorder was used to collect data. A FGD guide was used to guide the discussion (Appendix 2). The guide was informed by our conceptual framework – the gender-transformative learning framework (GTLF). Audio recording was completed and subsequently translated into English and transcribed by a translator external to the team. A and B, who collected data checked the transcripts for accuracy of translation.

Data analysis

For the data analysis, the researchers conducted a thematic inductive reflexive qualitative analysis based on Braun and Clark’s methodology (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2020). The data meaningfulness and the textual interpretations were crucial for theme creation (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Byrne, Citation2022). There was no prior existing coding scheme, and the analysis was data-driven based on the inductive methodology (Braun & Clarke, Citation2020).

EG and SHvW generated descriptive codes, created a coding tree, and formulated the first round of themes utilising Nvivo 12 software (Lumivero, Citation2022). Then input from the whole research team (including the data collectors) was gathered for cultural and data collection context. From there, the themes were finalised with the whole research team.

Reflectivity

Inductive thematic analysis is a subjective process, and the subjectivity is integral to the generation of interpretative themes. Thus, inherently, researcher bias, interpersonal biases, and methodological biases all affect the final presented results, and that makes it critical to reflect on the team’s biases.

The data collection and research team from EGST is based in Addis Ababa and is an Evangelical institution. Based on its Constitutional and strategic provisions, EGST believes in gender equality on relevant scriptural interpretations and applications. EGST is also sensitive about the positions of different denominations on gender issues, and they customise trainings to such contexts. EGST uses its freedom as an academic institution to discuss sensitive gender-related issues in academic teaching and research. EGST also considers government policies, ecumenical positions, and cultural responses on such matters. However, issues like VAWG unites almost all the Evangelical constituencies in Ethiopia and their willingness to engage can positively mobilise the community.

The research team from KI is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and is a public medical institute. EG is an Italian American with a Christian background and is a white woman from the Global North. SHvW is a white European woman, who is now living in Addis Ababa and working at KI. Living in Addis Ababa provides her with more contextual experience, and her academic background in social anthropology also impacts results creation.

Reflexivity was practiced throughout our team meetings and during data collection and analysis.

Ethics

The research team received ethical approval from Ethiopian Society of Sociologists, Social Workers, and Anthropologists (ESSWA) ethical review board. Prior to each FGD, the data collectors received written and verbal informed consent from the participants. To follow good ethical practice, all the data were anonymized and are stored appropriately according to ESSWA’s board regulation at EGST. All the participants were freely participating, informed of the study, and allowed to withdraw at any time. There are no benefits to the participants other than the knowledge gained from the prior CoHG training.

Results

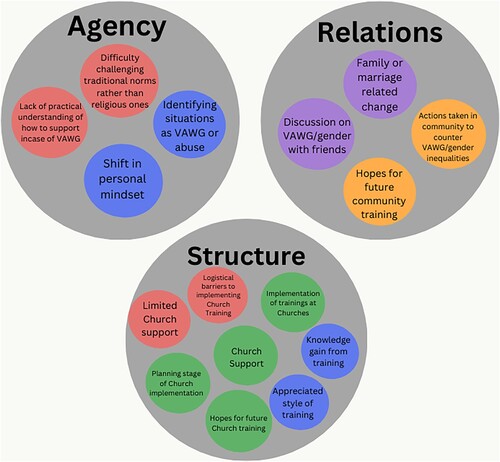

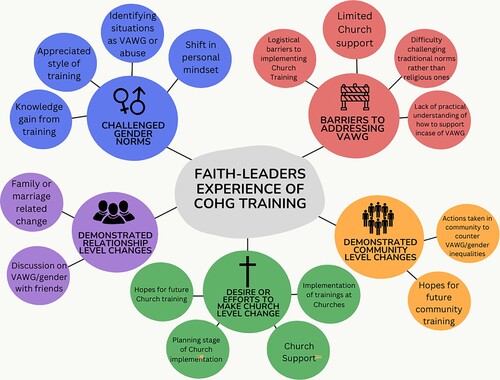

In total, there were five FGDs with faith-leaders from five different Churches out of the seven that were invited to participate. Faith-leaders from two Churches were unable to participate in the FGDs for logistical reasons. There were 17 participants with 14 males and three females. The data analysis process generated five themes and 16 sub-themes ().

Figure 1. Coding tree of themes and subthemes generated from focus group discussions with faith-leaders in Woliso, Ethiopia (Spring 2023). Formatting from Canva (Canva, Citation2024).

Challenged gender norms

The data analysis illustrates that the CoHG training challenged faith-leaders’ thinking and beliefs relating to gender norms and inequality. Data analysis reveals reflections on their personal mindset change and examples whereby faith-leaders defined situations as VAWG.

Shift in personal mindset

Participants expressed that they previously felt women were inferior and meant to be the helpers of men, but that the CoHG training taught them gender equality. Several noted that they began helping with household tasks, labour division, and gained more respect for their wives. Specifically, some discussed how important the Biblical re-interpretation process was for shifting their mindset. A faith-leader explains this transformative change process:

We [faith-leaders] have used the Bible verses out of context and after the training I have come to understand the truthful use of the verses. It has helped me understand what the Bible really speaks about when it comes to these [gender] issues. (FGD 1)

A change in mindset was also illustrated by the ways that faith-leaders explained how they would help an abused woman. Generally, they expressed a desire to help and support women. Examples of how they would help were by calming them down, taking them to the hospital, and bringing the issue to the Church or law. One participant claimed:

So, I will help her by telling her not to give up. And try to aid her in every way she needs even if it involves taking the matter to court. (FGD 3)

Identifying situations as VAWG or abuse

Another indication of a mindset change is the faith-leaders’ explanations of different situations as abuse. In their interactions with the congregation or community, faith-leaders described several instances where they noticed a woman was being treated unfairly. They mentioned a husband having an affair, a story of a young pregnant girl in a hospital who was raped by her brother, a young woman abandoned by a man after having sex with him, and many married couples experiencing conflict. One even noted a situation of psychological and physical abuse:

There is a psychological abuse because the husband used to say to her that she has another man in her life. Second thing they don’t agree they hit each other and also hit their children, and when the man hits the children, she will say things like you hit our children because you don’t like me. (FDG 2)

Discussion and dialogue as an impactful strategy to facilitate change

The faith-leaders implied that the style of the CoHG training facilitated their personal transformation. The Biblical and interactive nature of the CoHG training was particularly appreciated. Some mentioned that in prior trainings they just received a lecture, but in the CoHG training, they valued being able to get to know each other, hear real scenarios, re-interpret the Bible, and have discussions with the group. One participant explains how his fellow participants, helped change his mind.

We have already mentioned that the training was very nice. I don’t forget the disagreement we had during the discussion and how some of them changed their minds during the discussion. It has helped us assess ourselves, and we thank God. (FGD 4)

Relationship level changes

The faith-leaders were not merely changing the way they thought about gender, but also changing their relationships with family and friends.

Family or marriage-related changes

Many participants discussed how they are implementing the new knowledge within their family lives. Faith-leaders mentioned how post-CoHG training, they reframed their perceptions and no longer believed that the husband was the sole decision-maker, nor that the wife should be the only one doing household chores. They discussed how they now participate in the household and should serve each other. One male faith-leader described how he has implemented the changed mindset in his relationship with his wife.

I used to joke with my wife, saying I had authority over the house. We even talked about it in front of our children. But after the training, I decided I would never say this to her, and I refrained from joking in such a way even if I did not tell her. I now realized that even if I was joking about it, deep down I had an aspiration for it. (FGD 5)

Discussions on VAWG and gender with friends

Beyond the family space, some of the faith-leaders utilised the knowledge and skills from the CoHG training to shift the discourse among their friends. A female participant discussed how she is helping to free women from the confines of gender stereotypes, and others mentioned discussions with friends about the husbands’ role in the house. A particularly stark example is one faith-leader convincing a man away from abusing a girl.

One of the men that were there was preparing to violate this one girl then he was listening to me very carefully he didn’t say anything then he came closer to me and said … is this the truth about these things? And I said yes. Then he told me that he was preparing to do bad things on this girl and told me that what he heard about this issue really changed his mind and that he wants to repent. (FGD 2)

Community level actions or changes

As respected members of the community, faith-leaders also explained efforts they have made within other families or communities to reduce VAWG. They expressed their hopes to spread their new knowledge more broadly.

Actions taken at the community level to counter VAWG or gender inequalities

Several faith-leaders shared stories of when they saw or heard of gender inequality or abuses, and how they attempted to intervene. Specifically, among married couples, faith-leaders were facilitating conversations in homes about VAWG and gender. An emblematic instance was when a faith-leader noticed abuse and then went to the home to teach the husband and wife the lessons from the CoHG training.

After I took the training there was this woman who was a mother of two children, she was very hurt her husband used to beat her even in markets … Another day I went to her home and taught them the things we learned here. I told them that are a sin in front of God and that his wife is part of himself and no one is inferior to anyone. (FGD 3)

Hopes for future community VAWG programming

Faith-leaders also emphasised a need for the CoHG training among non-Evangelical populations and in rural areas. A faith-leader clearly describes this desire stating,

Especially in the rural areas these issues are very demanding, and they need to be addressed. I would like you guys to extend your training to rural areas for the people who desperately need it. (FGD 3)

Desires or efforts to make Church level change

Since the CoHG workshops, faith-leaders had begun some efforts to establish either a formal or an informal training program within their own Church congregations. While many of them stated they had yet to conduct a faith-leader organised intervention, most had taken some steps to include VAWG and gender inequalities in existing Church spaces.

Implementation of programs at Church

Faith-leaders at all five Churches included in this study have introduced the ideas from the CoHG model into regular Church programs such as youth groups, Bible studies, women’s groups, and marriage counselling. For example, they introduced the ideas of gender equality in a Bible study discussion of the book of Corinthians or with a newly married couple. Focus groups from two of the Churches claimed to have begun more official training programs. One FGD described establishing an educational program and moving it to Sundays to increase participation. Another one described a process of educating other individuals and implementing a program at different Church locations.

Personally, in the administration of the Church we have planned numerous things. We tried training 20 people in different parts of the Church which are 22 different Churches. (FGD 3)

Church support

All except one group of faith-leaders mentioned some form of support or anticipated strong support from their Church. Although some mentioned logistical or priority barriers, faith-leaders generally felt that the top Church leadership supported the ideas and efforts to implement a VAWG and gender equality-based program.

Also, when we work on the issue, they [high-level Church leaders] are on our side and are positive about it. (FGD 5)

Barriers towards future change or action

Even though faith-leaders describe general Church support for the ideas of the training and a desire to create a congregational training program, several barriers persist. Although the data illustrates many positive mindset changes and actions taken, barriers remain towards implementing congregational training programs and furthering ideas on gender equality.

Logistical barriers to implementing Church training program

Specifically, faith-leaders explained that they experienced logistical barriers to implementing a Church training program. Some mentioned personal issues, or financial barriers, or a lack of general interest among congregants. One faith-leader described that the congregants were expecting a per diem and focusing on the payment rather than the learning experience.

When they are asked to attend training, they ask if it has payment, and they don’t focus on the knowledge they will gain. The main problem is this. They say we are coming by leaving our work, so we need to get paid for it. (FGD 2)

Limited Church support

Although most of the Churches generally support the training programs, they experienced a lack of logistical or financial support from the leadership of their Church. One Church group (FGD 2) had not received official support and were struggling to economically prepare for the programs. Their Church leadership has other financial priorities, and thus are unwilling to fund supplies. Even among faith-leaders’ whose Church leadership had expressed support (FGD 3), the Church leadership had other logistical priorities.

There were plans to train the leaders and the trainers. There were other things going in our Church. We couldn’t go to the elders of the Church in order to start the training. (FGD 3)

Traditional norms rather than religious ones

The data analysis also revealed some gaps in the CoHG model that limited the faith-leaders ability to challenge their own or other traditionally held norms. From the results presented earlier, faith-leaders portrayed shifts in their Biblical or religiously held beliefs. However, addressing traditionally held norms or beliefs appeared to be more difficult. The faith-leaders mention the importance of maintaining marriages and long-held ideas of how situations are handled within the community. One faith-leader describes seeing a mentally ill mother cutting her young daughter, but the community just ignored it. In one clear example, a faith-leader describes seeing a visiting relative of a neighbour raping their housemaid and he took a picture of the rapist. Yet, despite clear evidence and calling the police, the family decided to use traditional reconciliationFootnote2 instead.

The boss asked me to call a police and I did. The police arrived at the house and talked to the girl, but the guy was nowhere to be found. Since the guy was a relative, they solved the issue with traditional reconciliation method. After the incidence all the family members including the boss put the blame on me because I called the police. (FGD 4)

Lacking a practical understanding of how to support in case of VAWG

Similar to the faith-leaders situation above, many of the participants wanted to support women but lacked a practical understanding of what to do in a situation of abuse. In response to how would they respond if an abused woman came to them, they generally expressed a desire to help but often did not explain specific actions. Most mentioned that it might depend on the situation and that they would take action to comfort her, take her to the hospital, go to the Church or law, and/or speak to the abuser. Although generally positive actions, they lacked some clarity on how to provide the best support. Several of the faith-leaders also mentioned wanting to make the abuse public without considering the stigma or harm that may cause to the woman involved.

For example, previously, we used to keep everything a secret but in the case of the woman, I called her Church leaders and told them that their Church member has caused a problem in his marriage, and I asked them how well they know the guy and I made an appointment to discuss with them. (FGD 4)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of faith-leaders transformative knowledge regarding VAWG and gender equality, following their participation in an intervention using the CoHG model, and to assess barriers and facilitators to congregation-level program implementation. The inductive thematic qualitative analysis indicates that the CoHG model challenged faith-leaders’ thinking and gender norms, the faith-leaders began transforming family and community relationships, and they had a desire to implement activities at the Church level. However, there were some barriers to further progress, such as logistical barriers, limited Church support, the CoHG training failing to address traditional norms, and a lack of a practical understanding of how to support women experiencing VAWG.

From the faith-leader perspective presented in this study, the CoHG training seemed to successfully allow for reflection and a mindset change regarding VAWG and gender. Compared with the prior study, the faith-leaders’ were identifying more situations as abuse and embracing a wider definition of VAWG than beating (Gobbo et al., Citation2023). Similar results are found in other studies with Orthodox, other Christian denominations, and Muslim faith-leader trainings with noted improvements in gender-equal mindsets (Istratii, Citation2022; Kamanga & World Vision International, Citation2014; Le Roux et al., Citation2020; Project dldl/ድልድል, Citation2024).

The Ethiopian faith-leaders also indicated a desire to work towards further change in their congregations and communities. Currently, EGST and other stakeholders are supporting further efforts with ongoing trainings on CoHG and Celebrating Family and Youth Empowerment training in Ethiopia. To further these positive developments, other studies (Freeman et al., Citation2017; Palm & Le Roux, Citation2017; Wolff et al., Citation2001) and the Ethiopian faith-leaders’ perspectives indicate that an expansion of the CoHG training and improved long-term support for the religious communities is important for effective, sustainable prevention efforts.

Although the results indicate many positive outcomes, they also illustrate gaps in the CoHG model. The first gap is that the model focuses on religious transformation and does not explicitly consider traditional norms. The results illustrate that the faith-leaders had a good grasp of the scriptural reinterpretation. They even employed these new textual interpretations with family, congregants, neighbours, and friends. However, there are also indications that they struggled to address some traditional cultural norms they experienced. Other research supports this idea. Tarekegn and Worku’s (Citation2018), who work on challenges in evidence in the Ethiopian court on rape, identified cultural norms as barriers to ensuring justice for victims. Traditional and religious norms are inseparable and the ideas of one can shape the other (Le Roux & Pertek, Citation2022). Thus, the CoHG training could benefit from addressing this overlapping influence.

The second gap is the faith-leaders lack of practical knowledge on supporting women experiencing abuse. When discussing how to support a woman, there was a wide variety of answers. Some were comprehensive, but others focused on making the abuse public or going to Church leadership. Studies on supporting women experiencing VAWG emphasise the importance of referring women to informal and formal support services and not always encouraging a woman to stay in an abusive marriage (Mshweshwe, Citation2018; World Bank et al., Citation2014). Providing the faith-leaders with concrete skills and resources on how to support women during future CoHG trainings, could greatly improve their impact as change agents. Additionally, supporting abused women is more difficult in a system that lacks support services such as shelters, mental healthcare, and economic opportunities (Irish Aid & UN Women Ethiopia, Citation2016; Zeidane, Citation2018). Thus, it is important to also examine other sectoral and structural changes that empower women.

Gender-transformative learning

Our study shows that the CoHG model can be considered to work towards transformative gender learning. However, the CoHG model mainly addresses the level of agency regarding gender equity and VAWG (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015; Kamanga & World Vision International, Citation2014). As our study shows, faith-leaders’ responses illustrate a shift in their own agency and a desire to improve the agency of women. Then the individual changes begin a larger process of transformation in their relationships and communities, but there are structural barriers that remain ().

Rao and Kelleher (Citation2005) describe that to improve inequal social systems and institutions, change must happen in both formal and informal relations. The four areas they claim require change are (1) women's and men’s consciousness, (2) women’s access to resources, (3) informal cultural norms and practices, and (4) formal institutions (Rao & Kelleher, Citation2005). From the results, it’s possible to see the change in the faith-leaders’ consciousness. Many expressed how they now believe men and women are equal. Their perceptions of men as the decision makers of the household or accepting certain harmful and unequal practices changed due to the CoHG training. This illustrates the ways that the faith-leaders own agency, for both men and women, strays from the traditional male dominating views (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015).

The transformation in individual consciousness of the faith-leader could also begin to improve informal religious and personal norms (Rao & Kelleher, Citation2005). The results suggest that the faith-leaders began to spread their new mindset into their personal relationships. This is especially clear in the way that the faith-leaders discussed their own marriages. Many mentioned that, after receiving the CoHG training, they use a more gender-equal distribution of household tasks and no longer use controlling language with their spouse. The faith-leaders also began changing the discourse with friends and neighbours regarding gender equality and equity. Here steps towards making relationship-level change are taking place (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015). Faith-leaders are aware of and attempting to reduce controlling actions of their own and in their community members.

Despite these positive changes in the agency and relationship aspects of the GTLF, there are more structural challenges remaining. Although many of the churches are supportive, there were logistical barriers on the Church level and personal challenges preventing the implementation of the planned faith-leader-led interventions.

There was also a lack of clear understanding of how to handle situations of abuse. For example, many faith-leaders mentioned following Church rules, but if the rules stigmatise the woman or prioritise marriage in all instances then it may not be helpful. Without clear guidelines, or social support services, or economic opportunities available to women then it is much more difficult to support women experiencing abuse and violence (Hillenbrand et al., Citation2015; Irish Aid & UN Women Ethiopia, Citation2016). Thus, the structural level, including improving aspects of women’s access to resources and transforming formal institutions, must be done at the same time as the agency and relationship changes initiated by the CoHG model training. This illustrates that although the CoHG training is useful, there are limitations that should be addressed by expanding it. Additionally, the CoHG model cannot happen in isolation but must be supported by other interventions, sectors, and actors (Heise & Manji, Citation2016).

Further implications

The results further demonstrate that providing continued and expanded CoHG training would be beneficial for the faith-leaders. Several expressed the need for financial support, more CoHG training in rural areas, and more information on VAWG and gender issues. These findings are supported by other studies, which conclude that faith-based prevention approaches should include accountability measures, more adaptive long-term interventions, and consideration of local health system complexities (Herzig Van Wees & Jennings, Citation2021; Le Roux & Palm, Citation2021a; UNDP, Citation2014). The findings also indicate that successful faith-leader led program implementation requires the support of top Church leadership. Thus, the Church’s top leadership who took the sensitisation training may need to be reminded with a refresher CoHG training and review session to strengthen their commitment.

The results presented here are specific to Ethiopian Evangelical faith-leaders from Woliso. Conducting further research in other contexts could provide additional nuance on the CoHG and faith-leaders as VAWG change makers. Specifically, it could be useful to expand the intervention to address the unique challenges in rural areas. Research into perceptions of gender equality and VAWG among Orthodox, Islamic, and other Protestant faith-leaders could expand the understanding of the benefits and limitations of a faith-leader intervention.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this qualitative study. The FGDs were small (some only had three participants) as they were based on the faith-leaders from each Church who had attended the CoHG training, and not all faith-leaders were able to attend. Larger FGDs would have perhaps allowed for longer and more stimulating discussions. Moreover, there are some limitations in the application of FGDs since group members may have hidden responses due to social desirability bias. Additionally, we were not able to differentiate based on opinions in the prior study and opinions in the FGDs due to the anonymization of the data for ethical reasons.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this study illustrate that the faith-leader CoHG training improves their personal mindset and individual relationships, but that the CoHG model could be expanded to include addressing traditional norms and more long-term support for the faith-leaders. This shows that a gender transformative learning-based approach among Evangelical Ethiopian faith-leaders can positively impact the GTLF levels of agency and relationships. Additional efforts may be required to address the higher level of structure by working directly and long-term with faith-based organisations, Churches, and other stakeholders.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was received from the Ethiopian Society of Sociologists, Social Workers, and Anthropologists with protocol number 027/2022. Received at ESSSWA’s IRB Meeting No. IRB/ESSSWA/016/022. Informed consent was received from all participants. Consent form attached as part of Appendix 1.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the participants during the informed consent process.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due ethical reasons for the privacy of the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors contributions

A.A., A.A.D., S.H.vW conceptualised the project. W.B. conducted the training, collected interview data, assisted with transcription and translation, and worked on the manuscript writing. N.M, Y.A. and M.D. conducted the data collection of interviews and observational data and did the transcription and translation. E.G. conducted the thematic data analysis and did the manuscript write up. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet, Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden, 171 65. Ethiopian Graduate School of Theology, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, [email protected]

Appendix 2_FGD Guide for Faith Leaders_GPH.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Appendix 1_CoHG Workshop 2 Agenda_GPH.docx

Download MS Word (17.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Project number based on 2007 Census (City Population, Citation2022; Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission & UNFPA, Citation2008).

2 Traditional reconciliation can take a variety of forms within Ethiopian culture. It often involves following rules that have been passed down generationally to elders or community leaders. Resolution can involve bringing in a third-party leader to negotiate or discussions between families. That often means, elders, family members, or other relatives will deal with and resolve cases of abuse/violence, such as abduction, beatings of wives, and other forms of violence. There can be forms of compensation provided to a victim or their family (Chemeda Edossa et al., Citation2007; Dezo, Citation2021; Tarekegn & Worku, Citation2018). For instance, the abductor could take her as his wife and demand a ransom for her family. The perpetuator will then not be taken to the court. From the data it is unclear what exactly took place in this scenario.

References

- Boyer, C., Paluck, E. L., Annan, J., Nevatia, T., Cooper, J., Namubiru, J., Heise, L., & Lehrer, R. (2022). Religious leaders can motivate men to cede power and reduce intimate partner violence: Experimental evidence from Uganda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(31), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). Thematic analysis | online resources. SAGE Publishing. https://study.sagepub.com/thematicanalysis.

- Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Canva. (2024). Canva Home. https://www.canva.com/.

- Chemeda Edossa, D., Awulachew, S. B., Namara, R. E., Singh Babel, M., & Das Gupta, A. (2007). Indigenous systems of conflict resolution in Oromia, Ethiopia.

- City Population. (2022). Woliso (District, Ethiopia). City Population Denmark. https://www.citypopulation.de/en/ethiopia/admin/oromia/ET041303__woliso/.

- Dezo, M. E. (2021). View of traditional conflict resolution mechanism in Ethiopia. Scientific Journal of Culture. https://biarjournal.com/index.php/lakhomi/article/view/422/443.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Federal Ministry of Health, & DHS Program. (2021). Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, & UNFPA. (2008). Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census Results.

- Freeman, D., Kelly, M., Milner, M., Patterson Roe, E., Stoltzfus, K., Van Hook, M., Wilson Harris, H., University, B., Terry Wolfer, T. A., Adedoyin, C., Anderson, G. R., Baldridge, S., Barker, S. L., Nazarene College, E., Bauer, S., Bell, M., Beach, T., Tanya Brice, R., College, F., … Poe, T. (2017). Integrating Faith and Practice: A Qualitative Study of Staff Motivations. Social Work & Christianity. www.nacsw.org.

- Gobbo, E. L., Berhanu, W., Amado Dube, A., Megersa, N., Demeke, M., Addisse, A., & Herzig Van Wees, S. (2023). Leveraging Faith-Leaders to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls: A Qualitative Study of Evangelical Faith-leaders’ Perceptions in Woliso, Ethiopia. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Haustein, J. (2011). Charismatic renewal, denominational tradition and the transformation of Ethiopian society. Encounter beyond routine. Cultural roots, cultural transition, understanding of faith and cooperation in development.

- Heise, L. (1998). Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002

- Heise, L., & Manji, K. (2016). Professional development reading pack: Social norms. GSDRC Applied Knowledge Services. www.gsdrc.org.

- Herzig Van Wees, S., & Jennings, M. (2021). The challenges of donor engagement with faith-based organizations in Cameroon’s health sector: A qualitative study. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czab006

- Hillenbrand, E., Karim, N., & Wu, D. (2015). Measuring gender-transformative change a review of literature and promising practices Written by CARE USA for WorldFish and the CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems.

- Irish Aid & UN Women Ethiopia. (2016). Shelters for women and girls who are survivors of violence in Ethiopia.

- Istratii, R. (2022). Training Ethiopian Orthodox clergy to respond to domestic violence in Ethiopia: Programme summary and evaluation report A Project dldl/ድልድል and EOTC DICAC collaborative programme. https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/855584/.

- Kamanga, G. & World Vision International. (2014). Channels of Hope for Gender: Uganda Case Study. https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/CoH4G_Uganda%20Case%20Study.pdf.

- Le Roux, E., Corboz, J., Scott, N., Sandilands, M., Lele, U. B., Bezzolato, E., & Jewkes, R. (2020). Engaging with faith groups to prevent VAWG in conflict-affected communities: Results from two community surveys in the DRC. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 20), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-020-00246-8

- Le Roux, E., & Palm, S. (2021a). Learning from Practice: Engaging faith based and traditional actors in preventing violence against women and girls Child Marriage View project Ending Violence against Children and Faith View project. UN Women, 2. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16611.27688

- Le Roux, E., & Palm, S. (2021b). Learning from practice: Exploring intersectional approaches to preventing violence against women and girls.

- Le Roux, E., & Pertek, S. I. (2022). On the significance of religion in violence against women and girls. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003169086

- Lumivero. (2022, November 11). Nvivo. QSR International.

- Ministry of Women Children and Youth. (2019). Further analysis of findings on violence against women from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey.

- Mshweshwe, L. (2018). Support for abused rural women in the Eastern Cape: Views of survivors and service providers. University of Johannesburg.

- Negash, B. (2021, July 12). UN Women’s “Women of Faith” initiative working towards ending violence against women and girls in Ethiopia | United Nations in Ethiopia. United Nations Ethiopia. https://ethiopia.un.org/en/135607-un-women%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%9Cwomen-faith%E2%80%9D-initiative-working-towards-ending-violence-against-women-and-girls.

- Palm, S., & Le Roux, E. (2017). Working effectively with faith leaders to challenge harmful traditional practices -case study with Christian aid Christian identity research, for World Vision International view project faith and gender in development project, for World Vision International View project. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327510528.

- Petersen, E. (2016). Working with religious leaders and faith communities to advance culturally informed strategies to address violence against women. Agenda (Durban, South Africa), 30(3), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2016.1251225

- Project dldl/ድልድል. (2024). Impact - Project dldl/ድልድል. https://projectdldl.org/impact/.

- Rakodi, C. (2007). Religions and development understanding the roles of religions in development: The approach of the RaD programme. Regions and Development, 9. http://www.rad.bham.ac.uk.

- Rao, A., & Kelleher, D. (2005). Is there life after gender mainstreaming? Gender & Development, 13(2), 57–69. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070512331332287

- Schilbrack, K. (2013). What isn’t religion?*. The Journal of Religion, 93(3), https://doi.org/10.1086/670276

- Sikweyiya, Y., Addo-Lartey, A. A., Alangea, D. O., Dako-Gyeke, P., Chirwa, E. D., Coker-Appiah, D., Adanu, R. M. K., & Jewkes, R. (2020). Patriarchy and gender-inequitable attitudes as drivers of intimate partner violence against women in the central region of Ghana. BMC Public Health, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08825-z

- Takyi, B. K., & Lamptey, E. (2020). Faith and marital violence in sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the links between religious affiliation and intimate partner violence among women in Ghana. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(1-2), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516676476

- Tarekegn, H., & Worku, A. (2018). Challenges of the strength of evidences presented to Ethiopian courts in rape cases among children below 14 years old: The case of West Shoa High Court. Sociology and Criminology-Open Access, 06(01), https://doi.org/10.4172/2375-4435.1000181

- UNDP. (2014). UNDP guidelines on engaging with faith-based organizations and religious leaders.

- UNFPA. (2005). Frequently asked questions about gender equality. United Nations Population Fund. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/frequently-asked-questions-about-gender-equality.

- Unicef Ethiopia. (2022). Oromia: Regional brief.

- United Nations. (2016). The 17 goals | sustainable development. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- United Nations. (2022). The sustainable development goals report. United Nations.

- UNODC. (2020). Addressing violence against women and girls in Ethiopia. https://www.unodc.org/easternafrica/en/addressing-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-ethiopia.html.

- UN Women. (2022a). Facts and figures: Ending violence against women | What we do | UN Women – Headquarters. UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/facts-and-figures.

- UN Women. (2022b). Review of Ethiopian law from a gender perspective final.

- Wolff, D. A., Burleigh, D., Tripp, M., & Gadomski, A. (2001). Training clergy. Journal of Religion & Abuse, 2(4), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1300/J154V02N04_04

- World Bank, Global Women’s Institute, & IDB. (2014). Violence against women and girls (VAWG) resource guide.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Violence Info – Intimate partner violence. WHO. https://apps.who.int/violence-info/intimate-partner-violence/.

- World Vision. (2014). Channels of hope: Field guide.

- World Vision. (2015). Channels of hope level of evidence brief. In The Lancet (Vol. 386, Issue 10005). Lancet Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61082-0

- Yibeltal, K., Workneh, F., Melesse, H., Wolde, H., Kidane, W. T., Berhane, Y., & van Wees, S. H. (2024). God protects us from death through faith and science’: A qualitative study on the role of faith leaders in combating the COVID-19 pandemic and in building COVID-19 vaccine trust in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMJ Open, 14(4), https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2023-071566

- Zavala, E., & Muniz, C. N. (2022). The influence of religious involvement on intimate partner violence victimization via routine activities theory. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(3-4), 1133–1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520922375

- Zeidane, Z. (2018). The federal democratic Republic of Ethiopia selected issues. Approved By Women and the Economy in Ethiopia. http://www.imf.org.