?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Existing research suggests that women spend a disproportionate amount of time on unpaid housework and childcare compared to men. However, there is a lack of empirical evidence on unequal time burdens due to childcare among women. This study analyses the quantum of time poverty and multitasking behaviours of 3623 rural women with children of varying ages across rural North India. Findings show that mothers with infants spend more time on childcare and less time on self-care and leisure, and employment-related activities as compared to mothers with older children; they also multitask with childcare more than mothers of older children across all their daily activities. Our findings suggest that interventions and policies need to be designed to raise awareness, identify/adopt novel approaches and technologies to reduce work burden of unpaid work on women’s time, provide accessible childcare and encourage a more equitable distribution of household responsibilities.

Introduction

Time is a finite resource necessary for ensuring wellbeing (Williams et al., Citation2016). Gender analyses of time use studies show that, across societies, women do more unpaid work than men (Craig et al., Citation2012; Dong & An, Citation2015; Qi & Dong, Citation2018; Sanghi et al., Citation2015; Sousa-Poza et al., Citation2001; Williams et al., Citation2016). This unpaid work includes household chores, caring for children as well as adults, among other tasks (Choudhary & Parthasarathy, Citation2007; Knodel et al., Citation2005; Shimray, Citation2004; Sidh & Basu, Citation2011).

When quantifying unpaid work, a study in Switzerland showed values of unpaid time usage range from approximately 27–39 per cent of gross domestic product for household work and approximately 5–8 per cent of gross domestic product for childcare (Sousa-Poza et al., Citation2001). Another study in China valued unpaid care work at approximately 44–56 per cent of the value of paid work (Dong & An, Citation2015). Women generally bear a greater burden of unpaid work that contributes to the essential wellbeing of their families and households (Floro & King, Citation2016).

Unpaid work is more prevalent in developing countries, where multiple social and economic factors burden women with arduous work and minimal support structures (Esplen, Citation2009; Kabeer, Citation2007). Rural women in these countries not only engage in labour-intensive activities such as agriculture and construction, but are also solely responsible for household chores including cooking and cleaning, collecting fuel and water, and caring for children and the elderly (Manhas & Gupta, Citation2017; Shimray, Citation2004). Boundaries between paid and unpaid work are more clearly established for men, who also spend comparatively more time in paid work and leisure activities, while women spend more time on unpaid work (Bhatia, Citation2002). Even if men do participate in household work, they consider certain tasks as feminine chores, such as washing clothes, outside their purview (Luke et al., Citation2014). As a result, women bear any additional burdens of unpaid work within households, which often goes unrecognised and undocumented (Hirway, Citation2015).

Literature review

In 1977, Vickery posited ‘time poverty’ as lack of time for rest and leisure after accounting for time spent in work (paid or unpaid) (Vickery, Citation1977). Since then, the literature has expanded substantially from assumptions about time spent on activities to more quantifiable measures of time poverty (Bittman, Citation2002). The underlying concepts used in the measurement of time poverty were coined by As in 1978, and they vary based on the degree of freedom of choice in these activities (As, Citation1978). These concepts postulate ‘four kinds of time’: 1) necessary time: time needed to satisfy basic physiological needs such as sleep, meals, and personal health and hygiene, 2) contracted time: referring to regular paid work including all work for which money is received for work or money is invested for things such as for education (this includes time to travel for work and waiting time), 3) committed time: includes all the activities that the an individual executes such as housework, buying a house, etc., and 4) free time: the time remaining after removing time for all activities included in the other types. Time poverty occurs when individuals have limited time for leisure, rest, and other activities they would like to pursue. Literature further posits that individuals’ decisions to allocate time are affected by the various responsibilities they have thus producing varying degrees of time poverty across the four kinds of time described above (Burchardt, Citation2008; Steinbach, Citation2006).

Time poverty is a discretionary measure looking at one activity at a time (sequentially). Many studies suggest, however, that women address time poverty by performing many tasks simultaneously (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017; Jain & Zeller, Citation2015). In 1995, Floro showed that omission of overlapping activities tends to create a systematic data bias (Floro, Citation1995). As a result, time devoted to certain activities such as childcare, for example, tends to be underestimated. In India, one study found that women struggled to balance both paid work and unpaid care responsibilities and used strategies of time stretching and multitasking; the study defines ‘time stretching’ as managing work and care activities by waking up early, taking minimal or no time for rest or leisure throughout the day, and going to bed late (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017). The same study defines ‘multitasking’ as taking care of children while cooking or washing clothes, or during paid work. Research in Bangladesh found that multitasking was practiced by both literate and illiterate women for more than two hours a day, combining childcare with other tasks such as cooking, cleaning, and farm work (Jain & Zeller, Citation2015). Multitasking is embedded in the concept of work intensity, and evidence suggests it negatively affects wellbeing (Jain & Zeller, Citation2015). The longer a woman has to mind children while performing other tasks increases the amount of stress due to such work (Floro, Citation1995). Mattingly and Bianchi note that women’s free time is often intermixed with other activities or the presence of their children, so their free time is not as beneficial as men's, in terms of reducing time pressure (Mattingly & Bianchi, Citation2003). Multitasking can also lead to constant mental stress and physical weakness, as women replace time for rest with management of their numerous responsibilities (Jain & Zeller, Citation2015).

Time burden due to childcare

Women with young children face an especially challenging predicament of balancing housework, childcare, as well as work outside the home (Becker, Citation1965; Chaturvedi et al., Citation2016; Gallaway & Alexandra, Citation2002; Sivakami, Citation1997, Citation2010). The limits of time combined with an overburdening of responsibilities lead to under-nutrition of young children, reliance upon older children to help care for young ones, and insufficient time for self-care, cooking, rest, and leisure (Chaturvedi et al., Citation2016; Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017; Jain & Zeller, Citation2015; Komatsu et al., Citation2018; Qi & Dong, Citation2018). Previous studies have shown that higher parity along with pre-school children increase mothers’ time on childcare compared to mothers of low parity or with older children, resulting in time poverty (Bittman & Wajcman, Citation2000; Bryant & Zick, Citation1996; Milkie et al., Citation2004; Sandberg & Hofferth, Citation2001; Sayer et al., Citation2004). In addition, other studies show that time burden also differs for women depending on whether they are employed or not as well as by the type of occupation they carry out (Cho, Citation2017; Sivakami, Citation2010). For example, a recent study shows that children of women working in low status occupations, which are often strenuous, are associated with a low nutritional status and high risk of mortality (Saabneh, Citation2017). While there are many studies showing that women’s contributions to household work are disproportionately greater than men’s, there is a lack of evidence on how time burdens vary among women of varying childcare responsibilities and life stages. This study examines time poverty among women with children of different ages and varying childcare responsibilities, especially within the context of a developing country.

A growing body of evidence shows that women are responding to time constraints by multitasking through the day. A multi-country study in South Asia and East Africa (India, Nepal, Rwanda and Tanzania) reveals that the women interviewed by the study were multitasking an average of 11.1 h a day (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017). Research also shows that multitasking can have serious negative physical and mental health consequences, which are enhanced among mothers with younger children (Jain & Zeller, Citation2015). Although many studies emphasise the importance of measuring multitasking, there is a growing need to develop precise measures of multitasking, by integrating unpaid and care work (Braunstein et al., Citation2011; Floro, Citation1995). There is also insufficient evidence about increased multitasking among mothers of young children compared to mothers of older children. Capturing childcare multitasking with other activities is often a secondary focus of many studies, which this paper explicitly addresses.

Conceptual framework

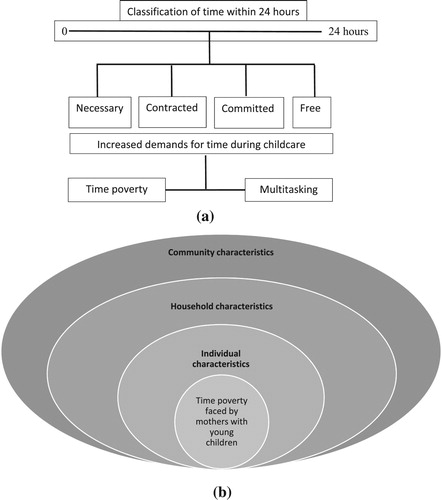

As existing literature suggest, this study conceptualises time as a finite commodity divided into the four kinds of time described: necessary time, contracted time, committed time, and free time (As, Citation1978). Within a day of 24 h, if an individual spends time in one of the four domains of time, that equates to reduced time in one of the remaining three areas. If a mother of a young child has to spend a disproportionately large amount of her time caring for a young child while engaged in all of her other unpaid work- such as domestic work- that she is expected to complete in a day, the time permitted in the three other domains during her day will suffer, such as necessary time for sleep and personal care, paid work and free time. We explore the time a woman spends on childcare within the finite time every individual has by studying patterns of time poverty among women with children of varying ages (see a).

Figure 1. a: Theoretical distribution of time resulting in time poverty among mothers with young children. b: Conceptual framework on time use poverty among mothers with young children.

Besides adjusting for time within the four domains, women accommodate additional responsibilities by multitasking while performing any discrete activity. While a woman cooks, she may also need to care for her children (engage them in play, feed them, etc.). Not accounting for this may lead to underestimations of workloads as well as time poverty. The literature falls short in addressing this within a conceptual framework. In this paper, we introduce the concept of multitasking within the context of time poverty as a second option or response to increased time burdens.

Literature suggest that several factors affect women’s time poverty, which result in multitasking. Considered within a socioecological framework, these factors include individual, household, and broader community factors. Individual factors include a woman’s age, parity and education. Household characteristics include household wealth and assets, and whether a family is nuclear or joint. Community factors can include local norms of household work and labour force participation, and availability of local services such as electricity, tap water, creches, etc. (Piggott, Citation2018). There is, however, a lack of evidence on factors associated with multitasking due to childcare. This paper attempts to fill this gap by hypothesising underlying individual and household characteristics that influence women’s multitasking behaviour with childcare (see b). A main reason is that infants require continuous attentive childcare. As a result, women take care of children while doing other activities.

Context

Our primary survey focuses on rural north India, as the majority of India’s population is still rural. Fertility rates remain high in rural India, where most women of reproductive age reside. Literature from India suggests that rural household chores are still a woman’s responsibility, with very little participation by men (Hirway, Citation2015; Kabeer, Citation2007). Women must make great additional sacrifices to work outside the home. The implications of these work burdens are much greater in rural areas, given the sheer numbers of women.

Analyses by various economists show that labour force participation by rural Indian women has declined and lags their urban counterparts (Abraham, Citation2009; Afridi et al., Citation2018; Gandhi et al., Citation2014; Himanshu, Citation2011; Hirway, Citation2012; Kapsos et al., Citation2014; Mazumdar & Neetha, Citation2011; Neetha, Citation2014; Neff et al., Citation2012; Rodgers, Citation2012; Sanghi et al., Citation2015). Several theories have been advanced to explain this phenomenon. Educated women from higher castes and wealthier households often have their mobilities curtailed to protect the status and honour of their families (Eswaran et al., Citation2013; Olson & Mehta, Citation2006). Meanwhile, there is a dearth of jobs for educated women, who no longer want to work as labourers or casual workers (Chowdhury, Citation2011; Kapsos et al., Citation2014; Rangarajan et al., Citation2011; Sanghi et al., Citation2015). As economic patterns have changed in rural India, men have sought employment through migration (Rodgers, Citation2012). Women remained confined to home, however, and experienced fewer opportunities closer to home (Rodgers, Citation2012). As young women are in the prime of their reproductive lives, having children, several productive years, in economic terms, are lost when they are expected to raise children and take care of the home before pursuing any other economic interests (Gammage et al., Citation2019; Naidu & Rao, Citation2018). Women then remain limited to low-paying, insecure, and part-time employment near their homes (Sanghi et al., Citation2015). Cultural norms that strongly determine behaviours are most prevalent in rural areas, and affect women’s work force participation (Kapsos et al., Citation2014; Piggott, Citation2018; Zaidi et al., Citation2017). Often local norms restrict women to limited, often segregated, labour market options (Kapsos et al., Citation2014).

This survey focuses on rural north India, and was conducted in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (U.P.), states with the lowest female workforce participation in rural India (Chakravarty, Citation2015; Dubey et al., Citation2017). Both are large states with similar contextual factors. Bihar is administratively divided into 38 districts, with a population of 104 million according to the 2011 census (Government of India, Citation2011). Primarily rural (88 Per cent), 59.7 per cent of those living in rural areas are literate, compared to 75.1 per cent literacy in urban centres. U.P is administratively divided into 75 districts, with a population of 199 million (Government of India, Citation2011). Three quarters (77.3 Per cent) of U.P.’s population is rural, with a literacy rate of 65.4 per cent compared to 75.1 per cent in urban areas. The average monthly income for a rural household in Bihar is INR 6,277, and about INR 6,257 in U.P. (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Citation2017). In Bihar, the median age at first marriage is 17.5 for women and 18.5 in U.P. The total fertility rate (TFR) is 3.6 children per woman in rural Bihar, and 3 in rural U.P. (Government of India, Citation2016a, Citation2016b).

Contributions to the field

This study contributes to the conceptual and methodological understanding of time poverty and multitasking. Using primary survey data from 3,623 women of rural north India, we developed a measure of work intensity while a woman is involved in childcare, i.e., a multitasking measure for concurrent childcare. This study provides and shares a new survey method and measure for multitasking analysis. The results show how time burdens captured by multitasking vary among mothers with children of varying ages, along with the factors associated with the behaviour of maternal multitasking.

We focus on the constraints faced by mothers and the importance of accounting for these constraints for better and equitable realisation of benefits for maternal and child health. This focus on the inequalities of time burdens, an often under-studied concept, reveals several implications for policy and programmes in rural north India. We emphasise the importance of raising awareness, adopting approaches to reduce the work burdens of women, and facilitating access to equitable childcare. For effective policies and programmes, it is important to understand time poverty, which women face disproportionately, and some of the associated factors to guide steps that can be taken to reduce women’s burdens and ensure time for other essential activities.

The next section of the paper describes the sampling and primary data collected for the study. It outlines the construction of measures and the statistical methods used for data analysis. Section three presents our analysis and results, and lays the groundwork for discussion of implications in section four. The paper concludes with ultimate findings and policy implications, in section five.

Data and methods

Sampling and data

The sampling strategy involved a random selection of blocks, an administrative unit, in the two states – 33 blocks in Bihar and 68 blocks in U.P. Twenty villages were randomly selected from each of the blocks. A house listing of 50 households in each village utilised a household roster. All members in a household were listed. Households were selected on the basis of a married woman in the household with an infant or youngest child five years of age or older. To measure time poverty and multitasking due to childcare, we included mothers with infants in our sample, contrasting their time burdens to mothers with a youngest child age five or older to identify the unique factors associated with time poverty among mothers with infants. If more than one woman in a household met the eligibility criteria, only one woman was randomly selected from that household. We chose to contrast the patterns of time use among mothers with infants and those with a youngest child at least five years of age to emphasize the differences in time burdens and multitasking among women of different life stages, and to compare how these women use their time over the course of a day.

A cross-sectional study collected primary data through structured interviews with women (Irani, Citation2018). Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to data collection. Trained investigators conducted interviews in a private space within a respondent’s home with full consent prior to initiating the interview. No form of compensation was provided to respondents for their time. In Bihar, data were collected from August through October 2017, and in U.P. from November 2017 through January 2018. The women in the three categories were identified from the same villages, which were randomly selected in the states. The survey included 960 women with a child under 6 months of age, 1,788 women with a child between 6 and 11 months of age, and 875 women with children 5 years of age or older.

The response rate was over 95 per cent. Non-responses were primarily because a potential respondent was not at home. Responses on time use patterns were compared among three groups of women: women with a child under 6 months of age, women with a child 6–11 months of age, and women with a child 5 years or older. All ages were captured in completed months or years. Mothers with different age groups of children were the primary independent variable of interest.

This study hypothesised that mothers with younger children spend more time in childcare and multitasking than mothers with older children do, and that multitasking and childcare would be especially greater for mothers with children under six months of age due to continued breastfeeding and other demands on their time. Based on prior field experience, as children grow older, they become less dependent, altering mothers’ workloads. As a consequence, we chose the lifecycle approach to observe time poverty and means of coping with it.

Measures

Time use surveys in India

Historically, NSSO surveys have collected time use data from men and women in India (National Sample Survey Organization, Citation1978, Citation1983, Citation2000, Citation2006a, Citation2011, Citation2014). Several scholars have argued, however, that these surveys underestimated the amount of women’s work, as they did not account for unpaid work (Chakravarty, Citation2015; Government of India, Citation2000; Hirway, Citation2002, Citation2012, Citation2015; Hirway & Jose, Citation2011; Jain, Citation2007; Jain & Chand, Citation1982; Mukhopadhyay & Tendulkar, Citation2006; National Sample Survey Organization, Citation2006b; Pandey, Citation2000). The first comprehensive time use survey was conducted by the Ministry of Statistics of the Government of India in 1998–99 (Central Statistics Organization, Citation2001; Government of India, Citation2000; Hirway, Citation2009). Further attempts to incorporate time use within existing national statistical surveys met with little success due to the mere scale and cost of such surveys. Several researchers have attempted to adapt and use it for various small scale studies (Chakravarty, Citation2015). A 2012 time use survey piloted in the states of Bihar and Gujarat helped classify women’s extensive contribution to the Indian rural economy by quantifying unpaid work (Government of India, Citation2012; Samantroy & Khurana, Citation2015). That national tool from the Ministry of Statistics was pilot tested and adapted for this study, as it has the most extensive list of non-work related codes, and has been used on a smaller scale in similar populations (Central Statistics Organization, Citation2001).

Quantifying time use

This time use survey was designed to obtain information on women’s various activities during the preceding 24 h. A quantitative tool was administered to respondents, who were asked to recall their last typical day, reported in 30-minute increments. The information collected provided a detailed account of time spent in approximately 29 activities such as resting, eating, personal care, work inside and outside the home, childcare, cooking, shopping, socialising, etc.; of these 29 activities, eight relate to childcare. Information was also collected on agricultural activities such as farming, gardening, and livestock raising, whether in the field or at the homestead. These categories were developed after extensive local field testing of a nationally used tool (Government of India, Citation2000; Hirway & Jose, Citation2011). Surveyed activities can be broadly categorised within four groups: self-care and leisure, childcare, household chores, and employment-related activities (see Annex Table 1). To understand time use patterns, we calculated the time spent on each of these primary activities by taking a sum across the 24 h in which the women reported doing that activity.

Quantifying multitasking with childcare

Our primary interest is in quantifying multitasking and childcare and assessing the individual and household factors associated with multitasking, specifically quantifying the true workloads of women involved with childcare for varying ages of children. The design of this survey allowed a unique measure of multitasking missing in previous studies. Typical surveys capture childcare as a primary activity and measure time spent on those activities, but our survey tool also captures childcare as a secondary activity when women are completing other tasks, providing a more precise estimate of the burden of childcare. We are also able to compare childcare burdens across child age groups.

In addition to recounting childcare as an exclusive activity, for every other discrete activity a respondent was asked whether she was taking care of her child during that activity as well. In this survey childcare, either captured as a primary activity or conducted while multitasking, was characterised as physical care of a child, grooming, putting a child to sleep, playing with a child, cooking, preparing food or feeding a child, accompanying a child to other places, along with other activities that could be deemed as childcare. This specificity helped prevent under-estimating time for childcare and workloads involved.

Using the unique survey tool, we calculated a multitasking score with the number of activities in which a woman respondent reported taking care of her child. If childcare was reported as a primary activity, we do not include that in the multitasking score, to avoid double counting. A woman who did not take care of her children would score a zero, but if she took care of her child while cooking and fetching water, the score would be one. This allowed measurement of multitasking with childcare for activities that do not necessarily involve childcare. Scores increase as women’s multitasking with childcare occurs with more activities.

Other covariates of interest include respondents’ ages (in completed years), type of family (nuclear/joint), number of children in the household, and household monthly income (in Indian rupees). Besides these variables, we include covariates such as the educational levels of the mother and sex composition of the child. However, we do not present those results in the analysis as they do not show any effect majorly due to homogeneity in the variables. These variables were chosen because existing literature suggests that they are associated with the amount of women’s unpaid work women do at home thus leading to time poverty (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017; Dubey et al., Citation2017; Dutta, Citation2016; Malathy, Citation1994; Zaidi et al., Citation2017). Around 25 per cent of the sample could not provide or estimate their monthly household incomes, and so the survey’s average household income was imputed to those households so to not to lose those responses from the sample. We repeated the entire analysis using the sub-sample having household wealth data and the full sample with imputed household wealth data, and there was no statistical difference in the values across all tables. Women’s age may influence multitasking behaviours, as it reflects not only energy levels but likely empowerment. Existing evidence suggests that an increase in household size and joint families reduce unpaid work by women (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017). In extended families, other women in a household may share unpaid work, and other family members may assist in childcare. In nuclear families, women may get support for care activities from older children, or from relatives nearby (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017; Zaidi et al., Citation2017). Due to this evidence, we include variables such as whether the family is nuclear or joint, and total children a woman has. Evidence also suggests that higher household income may reduce need for a woman to multitask, as she can substitute paid services to fulfill activities both at home and outside the home (Dubey et al., Citation2017; Dutta, Citation2016; Malathy, Citation1994). Hence, we include reported household income as a covariate in our analysis.

Statistical methods

Analysis began by describing the characteristics of the respondents and their homes by age of last child, and tested the differences in those characteristics among the groups. Since the variables are non-normally distributed and the groups being compared are not of an equal distribution, an F-statistic is biased. Hence, we present the Levene’s statistic and the Brown and Forsethe’s statistic to test the assumption of equality of variances among the summary variables (Brown & Forsythe, Citation1974; Mu, Citation2006). Levene proposed a test that could give an appropriate comparison for non-normal distributions. Brown and Forsethe proposed an additional test using other measures of central tendency.

We then calculated the average time spent in each category among the groups and tested if the differences were significant or not. To test the differences across the groups, a test of equal variances, Levene’s test, determined if the difference in the time use pattern was significant or not. This provided patterns for proportions and types of activities by women while caring for their children.

Regression analysis: factors associated with multitasking score

We first looked at the association of the categorisation of mothers by the age of the last child with the score of multitasking to analyse the direction and the magnitude of the effect relative to the reference group of mothers with children under six months of age. In the same regression framework, we added individual and household characteristics to see if they had associations to the categories of mothers. This study is interested in understanding factors associated with the multitasking behaviours of childcare among women.

Our outcome variable is the multitasking score, which is a count variable, and follows a non-normal distribution. To identify these associations with a count variable as an outcome variable, we first conducted a multivariate regressions analysis using Poisson regression, controlling for all household and individual characteristics. To control for the bias introduced by the presence of zeroes, we ran the models using zero inflated Poisson regression analysis. We developed the following equation:(1)

(1) where,

is the constructed individual variable, a count of the number of activities for which each woman reported she was taking care of her child;

is the categorical variable representing the category of the woman;

is a vector of individual characteristics such as women’s age and square of her age to see distributional differences;

is a vector of household indicators such as whether the family is nuclear or joint, total number of children of a woman, and household income. The zero inflated Poisson regression tested how these associations of individual characteristics with multitasking score varied by category of woman through a separate regression for each category and interaction of each characteristic with the multitasking score. The specification is:

(2)

(2)

Results

Descriptive statistics

presents the summary statistics of women for the three groups, those with children under six months of age, those with children 6–11 months of age, and those with children older than five years of age. The average age of respondents is 27 years old, with mothers of older children around age 37. About half of households were nuclear, represented by the type of family variable; the proportion of women living in nuclear families was highest among women with older children. The average number of children per woman is three, with household monthly income ranging from Rs. 8000–9000 across all categories.

Table 1. Summary statistics by women based on age of last child.

reports the average time spent in each activity in the three categories of women. Findings suggest that average time for personal care and leisure activities such as socialising and personal care are lower for women with infants than women with older children. Patterns in childcare show that women with children under the age of one year have significantly higher averages for time spent feeding, grooming, and playing with children than women with older children. Women with older children have higher averages of time spent in some household chores compared to women with infants; some of these chores include collecting fuel and water, cleaning the home, shopping, and caring for adults. Time spent in food preparation and cooking appear to be the same in all categories. Women with older children, on average, spend 60 min more per day in income-generating activities such as raising small and large livestock, compared to women with infants.

Table 2. Distribution of time spent on various activities across categories of women based on the age of last child.

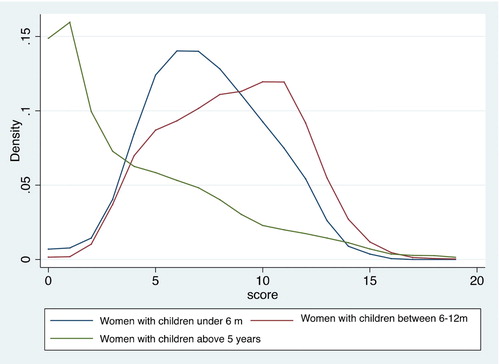

depicts the distribution of multitasking by women over the course of a day, by respondent category. The X-axis refers to the number of tasks each respondent reported (out of 29 broad categories). The graph shows a wide variance in work burdens among the categories. The density curve for mothers with children under one year of age is broader than for mothers with older children, and is skewed to the right. This is also reflected in , with an average number of activities by women with younger children being 7 or 8, compared to 4 activities for women with older children.

Figure 2. Number of activities where multitasking is reported by women with children of varying ages.

Multitasking patterns were dis-aggregated to understand which activities women principally multitask. shows that 20–30 per cent more mothers of infants report multitasking to provide themselves self-care and leisure compared to mothers of older children. For several household chores, a higher proportion of mothers with infants report multitasking than do mothers of older children; these household chores include travel, collecting fuel and water, cleaning, food preparation and cooking, and shopping. In most employment-related activities, women with infants are more likely to multitask than women with older children.

Table 3. Proportion of women reporting multitasking across categories.

Factors associated with multitasking

Having observed high proportions of multitasking among mothers with infants, we proceeded to identify characteristics of respondents and their homes associated with multitasking behaviours. presents the Poisson and zero inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression analysis of multitasking for the full sample. The first specification is a Poisson regression, which does not correct for women who reported no multitasking. In specification two, ZIP regression controls for the problem of zeroes. Specification three includes robust standard errors in the ZIP regression. The coefficients of the ZIP models are robust and consistent, even after controlling for heteroscedasticity. We also tested for model specification by calculating the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for the different specifications, as reported in . AIC and BIC are lower for the ZIP models, compared to the regular Poisson models, suggesting that ZIP models are preferable.

Table 4. Factors associated with Multitasking score (n=3623).

Table 5. Model specifications for Poisson and ZIP models.

According to the ZIP models, compared to women with children under 6 months of age, women with children between 6 and 11 months of age have 13 per cent higher multitasking scores, and women with older children have 25 per cent lower multitasking scores, suggesting that child age distribution is associated with multitasking behaviour. Women’s age squared term is also significant and negative, suggesting a lower multitasking score for older women that is lower by 0.1 per cent. If a family is joint rather than nuclear, we see that a woman’s multitasking score is lower by 6 per cent, implying that more adult family members are potentially helping women by sharing tasks. More children ares associated with more childcare tasks done by women. A higher income is associated with lessened work burdens, as the coefficient is both negative and significant.

Varying associations across categories of mothers

We hypothesised that if a woman’s youngest child was older, the mother would multitask less; our results support this hypothesis. We also wanted to identify the characteristics associated with multitasking by category of woman. In other words, we were interested to see if variations in age, type of family, number of children, and household income among the three categories of women were associated with multitasking or not. reports the interaction effects for each characteristic with the multitasking score using ZIP regressions; we report coefficients and associated standard errors. Each row in the table reports the level effects and interaction effects by category of woman with the multitasking score as the outcome variable.

Table 6. Associations of individual and household characteristics with multitasking score across categories of women (n=3623).

For women with younger children, if the age of the youngest child is five years or older, older women are three percent less likely to multitask than younger women. Being a member of a joint family and mother of an older child is associated with a 7.9 per cent lower multitasking score (p<0.001) than for women in nuclear families and with a child under six months of age. Among the same women with older children, however, more children is associated with lower multitasking, suggesting aid from older children. The level effect of income association suggests that a lower income among women with children older than 5 years of age is associated with more multitasking and higher workloads compared to women with children under six months of age from higher income households.

Discussion

This study addresses the importance of a key resource, time, and constructed inequalities among women and mothers throughout their lifecycles. Specifically, it highlights the unequal time burdens mothers of young children face compared to older counterparts. Mothers of young children spend less time caring for their own health and wellbeing while spending similar amounts of time in household chores compared to mothers of older children. This unequal work burden, with limited time for self-care and rest, can have negative impacts on the health and wellbeing of mothers of young children. As suggested by existing literature, time poverty also reduces the time women spend in cooking (Chaturvedi et al., Citation2016). As a result, nutritional outcomes, such as adequate dietary diversity and adequate feedings both for themselves and their children, are likely affected.

This paper fills a gap in the literature, both conceptually and methodologically, by revealing inequitable time poverties experienced by mothers at different life stages and their strategies for managing increased household and familial burdens through multitasking. Using primary data from 3,623 women in rural India, this research contributes to the dearth in the literature for quantifying burdens of unpaid work among mothers with children of various ages. It further contributes methodologically by capturing multitasking for childcare in a unique way, as opposed to only denoting primary and secondary activities measured in previous studies. This study also reveals that mothers of infants are accommodating their time poverty by multitasking with childcare more than mothers of older children do, during all major activities during the day such as household chores, self-care and leisure, and even other employment activities.

Multitasking during other employment activities highlights the need for developing measures and policies to support mothers of young children who want or need to be productive members of society, spending time in income-generating activities. Previous research suggests that support for unpaid care work allows women to pursue paid work that is empowering and is seen as a ‘double boon’ (Zaidi et al., Citation2017). To have access to self-earned money, women often leave home to pursue economic opportunities and are also less burdened with unpaid care work.

Some studies have attempted to identify processes by which women’s time in unpaid household work can be reduced, but find no reductions in time burden. A study in Australia attempted to determine if self-employment reduced time in household activities, while another study in India tried to measure similar effects of microcredit schemes on women’s time (Craig et al., Citation2012; Garikipati, Citation2012); both studies note no marked impacts from either self-employment or microcredit schemes on women’s time burdens. Consequently, several studies discuss women’s desires for safe and affordable alternate childcare facilities close to their work sites, enabling them to manage both tasks (Ilahi, Citation2000; Manhas & Gupta, Citation2017; Nair et al., Citation2014; Narayanan, Citation2008; Yeleswarapu & Nallapu, Citation2012). Systems need to be put in place to help women realise their full potential for earning as well as serving others. Other studies looking at mothers’ working patterns also stress the need for policies supporting formal childcare systems for women who wish to work (Sivakami, Citation1997).

In the Indian context specifically, this study contributes to the discourse on the continued need for a robust time use survey capturing unpaid work that is primarily carried out by women (Hirway, Citation2015). Capturing a substantially large sample of over 3,000 women in rural north India, this study reveals the disparate proportions of household responsibilities mothers with young children are responsible for while caring for their young children. This study also reveals the need for nuanced time use surveys that capture variations within female populations. It also reveals the need for policies and programmes focusing on the needs of women with infants and young children, who are often in the prime of their economically productive lives and may have a desire for paid work and to be economically contributing members of their families (Dutta, Citation2016).

This study further captures the association of individual and household characteristics on the degrees of time burdens women experience, expressed as patterns of multitasking in a unique manner not previously studied among rural women in India. This research’s focus on India is timely, as it has a growing population of young entrepreneurial women yet to be engaged in the formal workforce. Factors positively associated with less multitasking include older age, living in a joint family, and belonging to a wealthier household. This may be explained by the fact that members of joint families share tasks of caring for young children 6–11 months old. Women from wealthier households also more likely receive support for housework and other chores. These associations are consistent with previous literature showing that women perform less unpaid work in wealthier as well as joint households (Chopra & Zambelli, Citation2017; Dubey et al., Citation2017; Dutta, Citation2016; Malathy, Citation1994; Zaidi et al., Citation2017).

Policies and programmes are needed to address the inequalities of time poverty, an often under-studied burden. For individual families, interventions are needed with approaches that engage families of young mothers and their immediate social environments to raise awareness of the time burdens young mothers face, with redistributions of work burdens to others within the family or immediate social environment, adoption of labour-saving technologies to reduce household work burdens, and emphasis on the importance of equitable time distribution for better health and wellbeing of both mothers and their young children. Basic household appliances such as gas stoves, pressure cookers, refrigerators, blenders, and grinders can greatly reduce household workloads, along with piped household water access (Dutta, Citation2016). Local policies and programmes need to focus on affordable and accessible childcare in the vicinity of women’s homes to support young families. Angadwadi centres and neighborhood creches can provide childcare near homes. Community programmes need to be responsive and acknowledge and address gender norms in women’s expected roles for unpaid care work; engaging men in conversations to acknowledge the value of unpaid work and begin sharing those responsibilities with women would be an effective way to change normative practices (Zaidi et al., Citation2017). State governments have a key role in both acknowledging and addressing ways to reduce the burden of unpaid care work on women, while providing them with opportunities to seek employment and join the formal workforce. Government actions known to enhance women’s workforce participation include improved roads and transportation services, childcare at worksites, and rural electrification (Desai & Joshi, Citation2019; Dinkelman, Citation2011; Dutta, Citation2016; Government of India, Citation2014; Zaidi et al., Citation2017). A multi-pronged approach is needed to reduce women’s time poverty, unpaid workloads, and childcare burdens.

This study has some limitations. Although we contribute to the literature by measuring multitasking in a unique way, we were unable to quantify the exact amount of time women spend multitasking during a reported primary activity, as we did not ask for an exact amount of time in our survey. Hence, further research is needed to quantify the proportions of time spent multitasking concurrent with primary activities reported.

We did not include mothers in a continuous age pattern but contrasted mothers with infants with those with a youngest child of five or older. We cannot comment on the experience of time poverty and multitasking among mothers with children 1–4 years of age, as the intent of this paper is to understand the time burdens of mothers with infants and contrast them with women at a different life stage.

Another limitation is women’s ability to recall exactly all activities from the day before. Trained enumerators conducted the interviews in private spaces within women’s homes, with extensive preparation in conducting such interviews.

Conclusion

Due to limited evidence on time poverty among mothers of young children, we set out to understand inequalities in time poverty among these women and the degrees of multitasking and childcare they fulfill. Our study in rural Bihar and UP shows that mothers of infants experience more time poverty than mothers of older children. They also multitask more in daily activities than mothers of older children.

We then identified factors associated with multitasking and noted that women in nuclear families and those from poorer households multitask more than their counterparts. As families in developing countries become more nuclear in nature, policies and programmes are needed to address the unequal distribution of unpaid childcare and household chores among mothers of young children so all members of society can have the opportunity for a healthy, productive life. Furthermore, as countries like India work to advance their SDG goals, effective policies and investments need to better quantify time distribution and shift women’s time commitments so they can also participate in the formal economy (Floro & King, Citation2016).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abraham, V. J. (2009). Employment Growth in rural India: Distress-Driven? Economic & Political Weekly, 44(16), 97–104.

- Afridi, F., Dinkelman, T., & Mahajan, K. (2018). Why are fewer married women joining the work force in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades. Journal of Population Economics, 31(3), 783–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-017-0671-y

- As, D. (1978). Studies of time-Use: Problems and Prospects. Acta Sociologica, 21(2), 125–141. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4194228 https://doi.org/10.1177/000169937802100203

- Becker, G. (1965). A Thoery of the Allocation of time. The Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517. https://doi.org/10.2307/2228949

- Bhatia, R. (2002). Measuring gender Disparity using time Use Statistics. The Economic and Political Weekly, 37(33), 3464–3469.

- Bittman, M. (2002). Social participation and family Welfare: The money and time Costs of leisure in Australia. Social Policy and Administration, 36(4), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.t01-1-00262

- Bittman, M., & Wajcman, J. (2000). The Rush Hour: The Character of leisure time and gender Equity*. Social Forces, 79(1), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/79.1.165

- Braunstein, E., van Staveren, I., & Tavani, D. (2011). Embedding care and unpaid work in Macroeconomic Modeling: A Structuralist approach. Feminist Economics, 17(4), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.602354

- Brown, M. B., & Forsythe, A. B. (1974). Robust Tests for the equality of variances. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69(346), 364–367. https://doi.org/10.2307/2285659

- Bryant, W. K., & Zick, C. D. (1996). An examination of parent-child shared time. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(1), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/353391

- Burchardt, T. (2008). Time and income poverty: CASEreport 57. Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Central Statistics Organization. (2001). Time Use survey 1998-99. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Central Statistics Office, Social Statistics Division.

- Chakravarty, D. (2015). Capturing female work patterns in rural Bihar through NSS and TUS: A methodological note. Indian Journal of Human Development, 9(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973703020150207

- Chaturvedi, S., Ramji, S., Arora, N. K., Rewal, S., Dasgupta, R., Deshmukh, V., … Group, F. I. S. (2016). Time-constrained mother and expanding market: Emerging model of under-nutrition in India. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 632. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3189-4

- Cho, Y. (2017). Maternal work hours and adolescents’ body weight in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 13(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/1080/17441730.2019.1609294

- Chopra, D., & Zambelli, E. (2017). No time to rest: Women’s Lived Experiences of balancing paid work and unpaid care work. Institute of Development Studies.

- Choudhary, N., & Parthasarathy, D. (2007). Gender, work and household Food Security. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(6), 523–531.

- Chowdhury, S. (2011). Employment in India: What does the Latest data show? Economic & Political Weekly, 46(32).

- Craig, L., Powell, A., & Cortis, N. (2012). Self-employment, work-family time and the gender division of labour. Work, Employment & Society, 26(5), 716–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012451642

- Desai, S., & Joshi, O. (2019). The Paradox of Declining female work participation in an Era of economic Growth. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 62(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-019-00162-z

- Dinkelman, T. (2011). The effect of rural electrification on employment: New evidence from South Africa. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3078–3108. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.7.3078

- Dong, X.-Y., & An, X. (2015). Gender patterns and value of unpaid care work: Findings from China's first large-scale time Use survey. Review of Income and Wealth, 61(3), 540–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12119

- Dubey, A., Olsen, W., & Sen, K. (2017). The Decline in the labour force participation of rural women in India: Taking a Long-Run View. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 60(4), 589–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-017-0085-0

- Dutta, S. (2016). The Extent of female unpaid work in India: A Case of rural agricultural households. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 31(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.18356/5e29aba4-en

- Esplen, E. (2009). Gender and care: Overview report, BRIDGE Cutting Edge Pack. Institute of Development Studies.

- Eswaran, M., Ramaswami, B., & Wadhwa, W. (2013). Status, Caste, and the time Allocation of women in rural India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2), 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1086/668282

- Floro, M. S. (1995). Women's well-being, poverty, and work intensity. Feminist Economics, 1(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/714042246

- Floro, M. S., & King, E. M. (2016). The present and Future of time-Use analysis in developing countries. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 31(1), 5–42. https://doi.org/10.18356/748e616d-en

- Gallaway, H. J., & Alexandra, B. (2002). Gender and Informal Sector employment in Indonesia. Journal of Economic Issues, 36(2), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2002.11506473

- Gammage, S., Joshi, S., & Rodgers, Y. M. (2019). The Intersections of Women’s Economic and Reproductive Empowerment. Feminist Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1674451

- Gandhi, A., Parida, J., Mehtotra, S., & Sinha, S. (2014). Explaining employment Trends in the Indian economy, 1993–94 to 2011–12. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(32), 49–57.

- Garikipati, S. (2012). Microcredit and women's empowerment: Through the Lens of time-Use data from rural India. Development and Change, 43(3), 719–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2012.01780.x

- Government of India. (2000). Report of the time Use survey, main report. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Central Statistical Organization.

- Government of India. (2011). SRS Statistical Report 2011 Retrieved August 29, 2019, from http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Reports.html

- Government of India. (2012). Report of the Sub-Committee on time Use activity Classification. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Central Statistics Office, Social Statistics Division.

- Government of India. (2014). Mahatma Gandhi National rural employment Guarantee Scheme: Report to the People. Ministry of Rural Development. Government of India.

- Government of India. (2016a). National Family Health Survey-4, 2015-16, State Fact Sheet-Bihar: Minsitry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and International Institute of Population Sciences.

- Government of India. (2016b). National Family Health Survey-4, 2015-16, State Fact Sheet-Uttar Pradesh: Minsitry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and International Institute of Population Sciences.

- Himanshu. (2011). Employment Trends in India: A Re-examination. Economic & Political Weekly, 46(37).

- Hirway, I. (2002). Employment and Unemployment Situation in 1990s How Good Are NSS data. Economic & Political Weekly, 2027–2036.

- Hirway, I. (2009). Mainstreaming time Use surveys in National statistical System in India. Economic & Political Weekly, 44(49), 56–65.

- Hirway, I. (2012). Missing labor force: An explanation. Economic & Political Weekly, 47(37), 67–72.

- Hirway, I. (2015). Unpaid work and the economy: Linkages and their implications. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 58(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-015-0010-3

- Hirway, I., & Jose, S. (2011). Understanding women's work using time Use Statistics: The Case of India. Feminist Economics, 17(4), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.622289

- Ilahi, N. (2000). The intra-household allocation of time and tasks: What have we learnt from the empirical literature? World Bank, Development Research Group/Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network.

- Irani, L. (2018). Time use patterns of women in rural Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. . https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OGEXY6. In P. Council (Ed.), (1 ed.): Harvard Dataverse

- Jain, D. (2007). The Value of Time Use Studies in Gendering Policy and Programme [Paper presented]. International Seminar on Mainstreaming Time Use Survey in the National Statistical System in India.

- Jain, D., & Chand, M. (1982). Report on a time allocation study- Its methodological implications. In I. o. S. S. Trust.

- Jain, M., & Zeller, M. (2015). Effect of maternal time use on food intake of young children in Bangladesh: IFPRI.

- Kabeer, N. (2007). Marriage, Motherhood and Masculinity in the Global economy: Reconfigurations of personal and economic life IDS working paper No. 290. Institute of Development Studies.

- Kapsos, S., Silberman, A., & Bourmpula, E. (2014). Why is female labour force participation declining so sharply in India? ILO Research Paper No. 10: International Labor Organization.

- Knodel, J., Loi, V. M., Jayakody, R., & Huy, V. T. (2005). GENDER ROLES IN THE FAMILY. Asian Population Studies, 1(1), 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730500125888

- Komatsu, H., Malapit, H. J. L., & Theis, S. (2018). Does women’s time in domestic work and agriculture affect women’s and children’s dietary diversity? Evidence from Bangladesh, Nepal, Cambodia, Ghana, and Mozambique. Food Policy, 79, 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.07.002

- Luke, N., Xu, H., & Thampi, B. V. (2014). Husbands’ participation in housework and child care in India. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 76(3), 620–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12108

- Malathy, R. (1994). Education and women's time Allocation to Nonmarket work in an urban Setting in India. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 42(4), 743–760. https://doi.org/10.1086/452118

- Manhas, S., & Gupta, U. (2017). An analysis of farm women’s participation in agricultural and domestic activites: A case of rural Jammu. International Journal of Applied Home Science, 4(11&12), 10.

- Mattingly, M. J., & Bianchi, S. M. (2003). Gender differences in the Quantity and Quality of free time: The U.S. Experience. Social Forces, 81(3), 999–1030. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0036

- Mazumdar, I., & Neetha, N. (2011). Gender Dimensions: Employment Trends in India, 1993-94 to 2009-10. Economic & Political Weekly, 46(43).

- Milkie, M. A., Mattingly, M. J., Nomaguchi, K. M., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). The time squeeze: Parental statuses and feelings about time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 739–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00050.x

- Mu, Z. (2006). Comparing the Statistical Tests for Homogeneity of Variances. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2212. http://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2212

- Mukhopadhyay, S., & Tendulkar, S. D. (2006). Gender differences in labour force participation in India working paper: GN(III)/2006/WP2. Institute of Social Studies Trust.

- Naidu, S. C., & Rao, S. (2018). Reproductive Work and Female Labor Force Participation in Rural India. Political Economy Research Institute: Working Paper Series 458 Retrieved January 15, 2020, from https://www.peri.umass.edu/publication/item/1070-reproductive-workand-female-labor-force-participation-in-rural-india

- Nair, M., Ariana, P., & Webster, P. (2014). Impact of mothers’ employment on infant feeding and care: A qualitative study of the experiences of mothers employed through the Mahatma Gandhi National rural employment Guarantee Act. BMJ Open, 4(4), Article e004434. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004434

- Narayanan, S. (2008). Employment Guarantee, women's work and childcare. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(9), 10–13.

- National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). (2017). NABARD all India rural Financial Inclusion survey 2016-17.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (1978). Employment Situation in India 1977-78. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (1983). Employment Situation in India 1983. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (2000). Employment Situation in India 1999-2000a. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (2006a). Employment and Unemployment Situation in India 2004-05 (part-I). Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (2006b). Report No. 515(61/10/1), employment and Unemployment Situation in India 2004-05 (part-I). Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (2011). Employment and Unemployment Situation in India 2009-10. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- National Sample Survey Organization. (2014). Employment and Unemployment Situation in India 2011-12. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- Neetha, N. (2014). Crisis in female employment: Analysis across social groups. Economic & Political Weekly, 49(47), 50–59.

- Neff, D., Kling, V., & Sen, K. (2012). The Puzzling Decline in rural women’s labour force participation in India: A Re-examination. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 55(3), 407–429.

- Olson, W., & Mehta, S. (2006). The right to work and Differentiation in Indian employment. Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 49(3), 389–406.

- Pandey, R. N. (2000). Women’s contribution to the economy through their unpaid household work. Discussion Paper Series, NIPFP.

- Piggott, H. (2018). Exploring Women’s Labour Market Participation in Rural Bangladesh and India Using Mixed-Methods: Social Attitudes, Social Norms and Lived Experiences. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), University of Manchester, Manchester.

- Qi, L., & Dong, X.-Y. (2018). Gender, Low-paid status, and time poverty in urban China. Feminist Economics, 24(2), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2017.1404621

- Rangarajan, C., Kaul, P. I., & Seema. (2011). Where is the missing labour force? Economic & Political Weekly, 46(39), 68–72.

- Rodgers, J. (2012). Labour force participation in rural Bihar: A Thirty-year Perspective based on village surveys (pp. 30). Institute for Human Development.

- Saabneh, A. (2017). The association between maternal employment and child survival in India, 1998–99 and 2005–06. Asian Population Studies, 13(1), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2016.1239412

- Samantroy, E., & Khurana, S. (2015). Capturing unpaid work: Labour Statistics and time Use surveys. In U. K. Panda (Ed.), Gender Issues and Challenges in Twenty first Century (pp. 319–339). Satyam Law International.

- Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children's time with parents: United States, 1981-1997. Demography, 38(3), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0031

- Sanghi, S., Srija, A., & Vijay, S. S. (2015). Decline in rural female labour force participation in India: A Relook into the Causes. Vikalpa, 40(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090915598264

- Sayer, L. C., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children. American Journal of Sociology, 110(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.1086/386270

- Shimray, U. A. (2004). Women's work in Naga society: Household work, workforce participation and Division of labour. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(17), 1698–1711.

- Sidh, S. N., & Basu, S. (2011). Women's contribution to household Food and economic Security: A study in the Garhwal Himalayas, India. Mountain Research and Development, 31(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd-journal-d-10-00010.1

- Sivakami, M. (1997). Female work participation and child health: An investigation in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Health Transition Review, 7(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/40652231

- Sivakami, M. (2010). Are poor working mothers in South India investing less time in the next generation? Asian Population Studies, 6(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441731003603520

- Sousa-Poza, A., Schmid, H., & Widmer, R. (2001). The Allocation and value of time Assigned to housework and child-care: An analysis for Switzerland. Journal of Population Economics, 14(4), 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001480000057

- Steinbach, D. (2006). Alternative and Innovative time Use research concepts. World Leisure Journal, 48(2), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2006.9674437

- Vickery, C. (1977). The time-Poor: A New Look at poverty. The Journal of Human Resources, 12(1), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/145597

- Williams, J. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Tallis, H. (2016). A measure Whose time has Come: Formalizing time poverty. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1029-z

- Yeleswarapu, B. K., & Nallapu, S. S. (2012). A comparative study on the nutritional status of the pre-school children of the employed women and the unemployed women in the urban slums of guntur. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 6(10), 1718–1721. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2012/4395.2629

- Zaidi, M., Chigateri, S., Chopra, D., & Roelen, K. (2017). ‘My Work Never Ends’: Women’s Experiences of Balancing Unpaid Care Work and Paid Work through WEE Programming in India: IDS Working Paper 49.

Appendix

Annex Table 1. Categorisation of activities.