ABSTRACT

The paper considers son preference effects оn actual fertility behaviour in Kyrgyzstan, a post-Soviet country of Central Asia. Using data from the DHS2012 and DHS1997, I argue that risks of transitions to parities from the second to the fifth are significantly higher among women with no sons. Furthermore, the relation of risks of parity progressions to sex composition of children already born is not generally stronger in families with strict gender asymmetries. Attempting to explain this, I show that in such families, contraceptive use is less frequent – and that could complicate the implementation of son preference in such families and weaken their expected contrast with other families in the role of son preference for fertility outcomes. The possibility also is discussed that son preference may be supported by factors not related to family-internal norms, such as the need for all families to have a male heir for securing family wealth.

1. Introduction

Son preference is known to be one of the significant factors influencing fertility behaviour in a considerable number of countries. Studies of recent decades have shown that it can affect fertility at least in two different ways. First, son preference can cause sex-selective abortion, resulting in a skewed sex ratio at birth in low fertility contexts (see Chung & Das Gupta, Citation2007 for South Korea; Guilmoto, Citation2009 for Armenia and Azerbaijan and for an overview; Murphy et al., Citation2011 for China; Guilmoto, Citation2012 for Vietnam; Grogan, Citation2018 for Albania). Second, under son preference, transition to the next child is more probable if the couple has not yet achieved the desired number of boys. This is expected in societies where abortion is either socially disapproved or is of restricted availability. A higher propensity towards contraceptive use after achieving a certain number and sex composition of children is often observed there, and, on the other hand, desire to have a(nother) boy supports the transition to higher parities – in this way, increasing total fertility (see e.g. Chowdhury & Bairagi, Citation1990 for Bangladesh; Yount et al., 2000 for Egypt; Channon, Citation2017 for Pakistan).

Most studies on son preference agree that it is more expected in the context of strict gender asymmetries at the societal and family level, which make the value of sons significantly higher than the value of daughters (see e.g. Chowdhury, Citation1994 and for Bangladesh; Das Gupta et al., Citation2003 for several countries of South and South-East Asia; Kim, Citation2004 for South Korea; Pande & Astone, Citation2007 for India; Brunson, Citation2010 for Nepal; Boer & Hudson, 2017 for Vietnam, among many others). Generalising over existing studies, two groups of gender asymmetries can be distinguished which are expected to support son preference. One group provides for a demand for sons. Firstly, these include strict patrilinearity, under which daughters are basically ‘lost’ to their parents after marriage, when a young woman practically becomes a member of her husband’s extended family, does not have much interaction with her parents and in many cases is not a heir of their property. Secondly, demand for sons can arise from the higher ‘economic value’ of sons caused by better opportunities for men compared to women in the labour market. A weak system of state support of elder generations in some developing countries, together with gender discrimination in the availability of labour market positions, wage levels etc. lead parents to consider it important to have support of grown sons in old age. Apart from these practical issues, son preference can be strengthened by patriarchal values and norms in the family and the society, which subsume low empowerment and a subordinate position of a woman in her family and high social role of extended (joint) family, based mainly on the solidarity of male relatives (see cf. Miller (Citation2001) considering son preference as a component of what she calls ‘patriarchal demographics’). Such values and norms, however, are supposed to be less articulated in families where the wife has high education, employment outside the household or other attributes of autonomy. The suppressing effect of woman’s education and autonomous work on son preference has been evidenced by some studies. Asadullah et al. (Citation2021) argue that in Bangladesh, higher education of women correlates with a more balanced sex preference for children as opposed to a stronger desire to have boys among less educated women; Kabeer et al. (Citation2014) conclude that in the same country son preference is weakened among women having paid work (see also Bongaarts, Citation2013 for a discussion of women education and labour force participation as factors lowering son preference across developing countries).

The other group of factors correlating with son preference has to do with disadvantages of having a daughter rather than advantages of having a son. In some societies, having a daughter can be considered disadvantageous because of special responsibilities imposed on her parents. These can be financial responsibilities arising from marital norms (obligation of a big dowry paid by parents of a bride, etc.; cf. Arnold et al., Citation2002 for India), and moral obligations to guarantee daughter’s ‘honour’ and virginity.

At the same time, however, there are reasons to expect that the low position of women can also indirectly weaken the role of son preference for fertility outcomes. As already mentioned, contraceptive use after achieving the desired sex composition of children is known to be the central implementation of son preference in a number of countries. Some studies on societies where strict gender asymmetries prevail at the family level have shown that a turn to a broad use of contraception there is more likely in families with higher gender equality (see Sathar et al., Citation1988; Morgan & Niraula, Citation1995; Mason & Smith, Citation2000; cf. Chowdhury, Citation1994 and Yount et al., 2000 arguing for Bangladesh and Egypt, respectively, that women with higher education have a higher propensity to contraceptive use there). Therefore, a bidirectional effect on son preference can be expected from strict gender asymmetries in a family. Under such asymmetries, both the desire of parents to have a son (or a certain number of sons) can be higher and stopping child bearing after achieving desired sex composition of children can be more problematic.

In the present paper, I consider son preference in Kyrgyzstan, a former post-Soviet republic of Central Asia. The reason to turn to this country is that a number of informal social norms reported for it make son preference probable, and that son preference in desired fertility has been reported for Kyrgyzstan (see Section 2 for details). The paper mainly deals with the effects of son preference on actual fertility behaviour rather than with fertility desires or intentions. With the help of proportional risk models based on the data of Kyrgyzstan Demography and Health Surveys (DHS) of 2012 (the DHS1997 is used for robustness check), it is demonstrated that transition to third and subsequent children is significantly more probable when all children born to a couple before are girls. I further demonstrate that son preference has nearly equal strength among subsamples of women whose families differ in the degree of certain gender asymmetries. Some explanations to this result are considered, including the possible role of contraceptive use. In this way, the paper contributes to the study of son preference in two ways. First, it extends current knowledge on the geographical scope of son preference in actual fertility behaviour. Second, it demonstrates possible new aspects of the relationship between son preference and gender asymmetries.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 gives a short overview of demographic trends and gender relations in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan. In Section 3, the research questions (hypotheses) are outlined. Section 4 represents the data used in the study and the research methodology. Results of the analysis are put forward in Section 5 and discussed in Section 6.

2. Kyrgyzstan: fertility changes and their context

Kyrgyzstan, with a total population of 6.3 million people in 2018, is a multi-ethnic country of Central Asia. Its main ethnic groups are Kyrgyz (71 per cent according to the 2009 census and 73.5 per cent according to the administrative sources at 2018), Uzbeks (14.3/14.7 per cent) and Russians (7.8/5.5 per cent). Kyrgyz and Uzbeks are for the most part Muslims, and Russians for the most part Orthodox Christians.

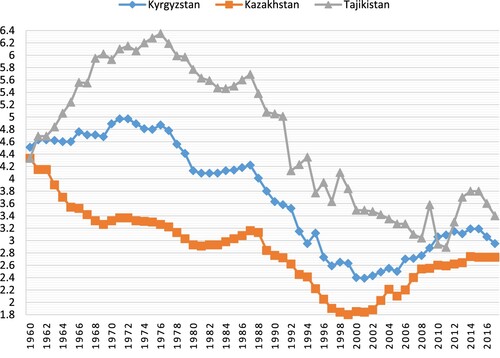

Kyrgyzstan experienced a dramatic decrease in fertility after the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991), which was followed by its growth in the 2000s (see for TFR dynamics in Kyrgyzstan and some of its neighbours). The fertility decrease in the 1990s did not reach the replacement level (for more details on fertility quantum and timing in Kyrgyzstan, see Nedoluzhko & Andersson, Citation2007; Agadjanian et al., Citation2008, Citation2013; Spoorenberg, Citation2013, Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Nedoluzhko & Agadjanian, Citation2015; Kazenin & Kozlov, Citation2020) ().

Figure 1: Period TFR in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Tajikistan, 1960–2018. Source: Based on data available at: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/sng__tfr.php

The issue of gender relations in Kyrgyzstan after the collapse of the Soviet Union is rather controversial. Generally speaking, the dissolution of Soviet institutions and societal norms – which imposed gender equality, is known to result in a partial revival of traditional family norms in Central Asia, supported by the active Islamic renaissance (Kandiyoti, Citation2007). In some particular aspects of social organisation, existence of strict gender asymmetries in the post-Soviet decades looks undisputed. Specifically, according to Ismailbekova (Citation2014), women normally leave their parental family after marriage. A young family can either live with the husband’s parents or separately, but in each case, the wife is expected to actively assist her parents-in-law in housework and to take a strictly subordinate position with respect to relatives of her husband.

Strict gender asymmetries are also indicated by very different roles of parents of the groom and the bride in relation to the wedding ceremony. While the former are usually expected to pay for the wedding reception, the latter are required to prepare a sizeable dowry, which includes furniture, household appliances and sometimes even an apartment or a house (Liebert, Citation2010).

With some other gender asymmetries, however, the situation is less obvious. Available studies agree that temporary labour migration to Russia and Kazakhstan, in which a high per cent of Kyrgyzstan population is involved since the beginning of the 2000s, has had a serious impact on the position of women, both those who had migration experience and those who stayed home.Footnote1 Long absence of men from their homes makes the role of women staying in the country more decisive in some family questions (Ismailbekova, Citation2016). Thieme (Citation2008) reports on a rather complex transformation of family relations due to labour migration of women, under which women often become economically most successive members of their households, but conventional obligations in house-keeping and child-rearing are still for the most part imposed upon women.

If we turn to quantitative indicators, the picture also is rather complex: certain advances towards higher gender equality coexist with some rather strict gender asymmetries. According to the DHS2012, woman’s median age at first marriage was 20.6 years, which shows that child marriages, typical for societies with the low social position of women (Asadullah & Wahhaj, Citation2019), are not popular. The mean age gap between husband and wife, however, was 3.9 years, which is considerably more than in societies with high degree of gender equity (on age gap between spouses as an indicator of gender inequality in families, see e.g. Bras & Schumacher, Citation2019 and references there). Mother’s mean age at first birth stayed on a rather high plateau of 23.4–23.7 between 2006 and 2010 according to Kyrgyzstan National Statistics Agency, but afterwards, it started a gradual decrease, somewhat unexpected if weakening of gender asymmetries is supposed (cf. Samari, Citation2017 for possible relation of early motherhood to gender asymmetries in the context of a developing country). Nedoluzhko and Agadjanian (Citation2015b) note a decrease of arranged marriages and marriages involving bride kidnapping in the post-Soviet era; woman’s freedom to divorce her husband, however, differs considerably across ethnic groups, despite the country growth of risks of divorce (Dommaraju & Agadjanian, Citation2018).

Educational level of women was actually higher than that of men according to DHS2012 (26.8 per cent of women, but only 21.6 per cent of men had higher education). Note, however, that treating educational level of a woman as an indicator of her position in her family and in the society is problematic in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan. As noted by Thieme (Citation2008), the value of education has become considerably lower in Kyrgyzstan during the recent decades, caused both by massive corruption in educational institutions and by loss by many highly educated people in their professional positions at the labour market after the collapse of the USSR. Despite the higher educational attainment, only 31.1 per cent of women reported to have a job within 12 months before the survey at the DHS2012, compared to 78 per cent of men. Moreover, 47.9 per cent of married women with a job reported that their earnings were lower than those of their husbands, and only 9.5 per cent acknowledged the opposite. Women enjoyed considerable autonomy in taking decisions concerning money they earned (only 3.5 per cent of those who had labour income reported that it was their husband who mainly made decisions on how to use the money), but women’s attitudes to domestic violence towards wives were rather tolerant: 33.7 per cent of women aged 15–49 found husband beating his wife acceptable – at least under some circumstances.

Gender asymmetries can be observed in desired fertility measured by the DHS1997 and 2012 (Spoorenberg, Citation2018). As shown by those surveys, the probability of wanting one more child was significantly higher among women who have only girls or who have only one boy compared to those who have at least two boys. Available data suggest that son preference can be implemented by contraceptive use rather than by abortions in Kyrgyzstan. The proportion of those who have had at least one abortion among all respondents was 30.2 per cent according to DHS1997 and 18.0 per cent according to DHS2012, which points to a possible decrease of abortions in post-Soviet time. Moreover, among women who have had an induced abortion, less than one per cent called gender preference (unwillingness to have a girl or a boy) as the reason at the DHS2012. By contrast, the proportion of women using contraception was growing in the post-Soviet time, as a comparison of survey results suggests. According to the DHS1997, only 16.7 per cent of never-married women have reported not to have ever used any contraception method, and 76.7 per cent reported they had used a modern method. The DHS2012 indicate widespread knowledge of contraceptive methods, as 94.4 per cent of all respondents have reported to know modern methods. The unmet need for contraception discovered by the DHS2012 was at a level of 18.1 per cent among women currently married or living with a partner.

The low frequency of sex-selective abortions agrees with the lack of imbalances in sex ratio at birth (SRB). According to the Kyrgyzstan National Statistics office, in 2010–2019, country-level SRB fluctuated between 104.8 and 107.4 boys to 100 girls, i.e. did not depart from natural standards (see note 2 on DHS estimates of SRB). Note that SRB is expected to be balanced if sex preference is not implemented by abortions, because the sex of the child at each birth order is not controlled by the parents in this case (see Basu & de Jong, Citation2010).

3. Research objectives

My central research question concerns the role of sex composition of children already born to a woman for risks of further childbearing. I compare effects of all possible variants of sex composition of children already born on the transition to the next child. I do not consider the order of sons and daughters among children already born, concentrating instead on the total sex composition of children. In this way, I attempt to find out what total number of sons can be considered as the ‘target’, which regulates fertility behaviour. My central hypothesis is that risks of transition to the next child are negatively related to the number of boys already born. I consider this hypothesis separately for transitions from the second to the fifth parities.

My second hypothesis concerns the role of family relations for son preference at the individual level. It suggests that the role of sex composition of children already born for transition to the next child is higher among women in whose families gender inequalities are more articulated. This hypothesis, again, is separately considered for transition to different parities.

Based on the literature discussed in the Introduction, I consider two hypotheses concerning contraceptive use. One hypothesis suggests that the propensity of contraceptive use among women is positively related to the number of boys being born. If this hypothesis is borne out, it will confirm that contraception is an instrument with which son preference is implemented. According to the other hypothesis, contraceptive use is less expected in families with strict gender asymmetries. Simultaneous confirmation of both hypotheses points to an indirect negative relation between gender inequality and son preference in actual fertility outcomes.

4. Data and methodology

4.1. Data

My primary source of data was DHS2012, held in August–December 2012. Its individualised sample of women comprises 8208 respondents aged between 15 and 49. Observing consistency and regularity of reported fertility trends, Schoumaker (Citation2014, p. 16) ranks the quality of DHSs in Kyrgyzstan as ‘good’. Nevertheless, Spoorenberg (Citation2017b) has argued that the DHS2012 has overestimated fertility level in Kyrgyzstan as compared to civil registration data. It is, however, shown in that study that the overestimation is due in the serious degree to the underrepresentation of single (therefore presumably childless, because of very low out-of-wedlock fertility) women in the DHS sample. The TFR estimated according to the DHS becomes more than twice closer to the TFR calculated using civil registration data if the former is adjusted by applying the proportion of single women registered by the 2009 Census. Given this primary source of fertility overestimation by the DHS2012, I did not expect serious distortions in proportions of women having two, three etc. children in it.Footnote2

The same analytical procedures as I used for the DHS2012 were applied to the DHS1997, too, which allowed for the expansion of the study to women of earlier cohorts. However, due to the relatively small women sample of the DHS1997 (3848 women), not all models run for it were statistically significant. Besides, some relevant parameters were absent in the DHS1997 database. Therefore, the DHS2012 remained the principal source of data for my study, and the DHS1997 being used more for robustness checks.

To study the transition to different parities, subsamples were chosen from the surveys’ samples, which contained only women who were in their first marriage at the time of the survey. The exclusion of women who have never been married was justified because of the negligible frequency of out-of-partnership child bearing in Kyrgyzstan. Women whose marriage was not the first one for them were not included because such women could be motivated to achieve a desired sex composition of children with their current partner, irrespective of the number and sex of children they had before. Divorced and widowed women were excluded because the DHS database does not indicate the date of termination of their partnership, what did not allow to limit the period for which odds of child bearing had to be studied.

4.2. Indicators of gender asymmetries

On choosing parameters of the DHS dataset as indicators of gender asymmetries, I mainly follow the family patriarchy measures discussed in Szołtysek et al. (Citation2017) as well as women empowerment measures suggested in Mason (Citation1987) and measures of gender bias in a family discussed in Asadullah and Wahhaj, Citation2019. The following parameters available from the DHS1997 and DHS2012 databases were used:

Age gap between the woman and her husband (see references in Section 2 on the use of this indicator as a proxy for gender (in)equality in a family). A dichotomic variable was used to distinguish women whose age gap was higher than the average for married women of the sample.

Patrilocal residence. As mentioned above, the absence of patrilocality does not obligatorily imply a departure from patriarchal family norms in the case of Kyrgyzstan, because even when a young family resides separately from the husband’s parents, the wife often is expected to be actively involved in house-keeping work in the household of her in-laws. Nevertheless, I assume that a woman identifying her father-in-law as the head of the household indicates not just joint residence with in-laws, but also acknowledging the authority of the elder members of husband’s family.

Educational gap between spouses. The dichotomic parameter takes the meaning 1 if only husband has higher education, and 0 if either both spouses or none of them does.Footnote3

Accepting a husband’s violence towards his wife. The DHS questionnaire contains questions on the acceptability of a husband to physically punish his wife under various circumstances (when she neglects her children, when she goes out without telling her husband, etc.). I used a generalised dichotomic parameter which had the meaning 1 if a respondent found this practice possible at least under some conditions and 0 otherwise.

4.3. Models

For transition to each parity, the Cox regressions were run with the sex composition of children already born as an independent parameter. The regressions estimated risks of the next childbirth for woman depending upon the number of sons she has, separately for each parity, and in this way checked the hypothesis on the role of son preference for parity transitions. To check the hypothesis on the role of gender asymmetries for son preference, I followed the approach of Javed and Mughal (Citation2020) and ran the same models for subsamples differing on the meaning of the parameters listed in 4.2.

At modelling transition risks to parity n, I excluded women whose children of orders n−1 and n were twins. The independent parameter of interest was the number of boys already born, ranging from 0 to the number of the woman’s current parity. In all the models, I controlled for woman’s year of birth, higher education (completed or at least started) vs. lack thereof, wealth quintile, age at the previous childbirth and native language (used as a proxy for ethnicity).

None of the independent parameters was treated as time-varying in Cox regressions. Treating the family wealth parameter as time-constant was justified by the rather low level of wealth mobility in Kyrgyzstan, including poverty stagnation as discussed in World Bank (Citation2015). The same solution looked more questionable for educational level. To set that parameter as time-varying, however, was impossible because the DHS data did not provide a chronology of women’s education. At the same time, assigning the current educational level of a woman to all months of her life course included in the analysis was unlikely to create a serious distortion because students normally start higher (tertiary) education quite early – at the age of 18–19 – in Kyrgyzstan. Among the parameters used for subsamples stratification, treating an educational gap between spouses as time-constant was justified under the same reasoning, and age gap between spouses is time-constant, as only women in their first marriage are considered. Treating partilocality as time-constant appears justified because living with parents of the husband is Kyrgyzstan is much more common for women married to the youngest son (Landmann et al., Citation2017). This is based on a custom for the youngest son to stay in the parental home, and this custom is most often already obeyed from the start of marriage. For attitude to domestic violence, time-variability is disputable. However, I stick to the assumption that women’s attitudes to such basic aspects of family relations are to a large extent conditioned by their early socialisation experience and therefore does not tend to fluctuate during the life course.

To check the hypotheses about contraception, logistic regressions were run for women’s report whether they use (some type of) contraception at the period of the survey. To get a higher statistical validity, I included women of all parities in these models, starting with the first one in the sample, and used the current number of children as a control parameter together with the controls used in the models discussed above. The parameter of sex composition had four generalised meanings: ‘no boys’, ‘equal number of boys and girls’, ‘more boys than girls’ and ‘more girls than boys’. The parameters of gender relations were included one by one in the models. As contraceptive use was modelled for the time of the survey, some time-varying dichotomic parameters defined for the time of the survey were added, which signalled a woman’s having a say in some domestic issues (solutions on spending money which her husband earns, large household purchases, visits to relatives and family, etc.; obvious time-variability of these parameters did not allow to use them for building the subsamples for the Cox regressions).

5. Results

The distribution of the independent variables in the largest subsample of the DHS2012 used in the study, i.e. women in the first union, is shown in . The distribution of different parameters signalling gender asymmetries is far from uniform. Thus, about 50 per cent found domestic violence towards wives acceptable at least under some conditions, and only a little above 20 per cent had a job which they were doing autonomously from members of their household in the time of the sample. More than 85 per cent reported that they have a say in household solutions.Footnote4

Table 1. Descriptive parameters of women in their first union, DHS2012 (weighted sample)

shows the Cox regressions for transition to the next parity relative to sex composition of the existing children (in this and the subsequent tables, incidence rates ratios are shown for non-continuous independent parameters). For all the parities from the second to the fifth, risks of the transition are significantly higher for women who had no boy before. The significance level for transition to the third and subsequent parities is higher than for transition to the second one. Differences between transition risks between women with different positive numbers of boys already born appear to be rather low.

Table 2. Cox regressions for transitions to parity transitions (risk ratios), for women with different sex composition of children already born, DHS2012 (here and below ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1, and SE in parentheses)

reports results of similar regression analysis for the DHS1997 (for reasons of space, only risk ratios for different sex compositions of children already born are shown; for transition to the fifth child, the model was insignificant probably because of low sample size and is not shown). Similar to the DHS2012, risks of transition to the third and the fourth children become significantly lower if there is at least one boy among children already born.

Table 3. Cox regressions for transitions to parity transitions (risk ratios), for women with different sex composition of children already born, DHS1997

shows logistic regressions for contraceptive use. Among parous women having no boys, odds of contraceptive use are significantly lower than among women having at least one boy. Exact proportion of boys among children already born to women having at least one boy does not seriously affect the odds ratios. Among the gender relations parameters, patrilocal residence makes odds of contraception use significantly lower, whereas woman’s partaking in the household decisions and autonomous work makes the odds significantly higher. The age gap between partners is not significant for contraception use, as well as woman’s attitude to domestic violence (the respective models are not shown in ). So, a number of the indicators of gender asymmetries make the propensity of contraceptive use lower, while others are neutral to it.

Table 4. Logistic regressions for odds of contraception use, DHS2012, women in first marriage

In , risk ratios for transitions to different parities are shown for subsamples of women respondents of the DHS2012 with different meanings of the parameters introduced in Section 4.2. For transition to the fifth parity, the ratios are not shown as most of the ‘subsample’ models for it were of low significance. It is easy to see that in most of the pairs of subsamples, the relation of risks of parity transition to sex composition of children is quite similar in both subsamples.

Table 5. Cox regressions for parity transitions for subsamples of women differing on one of the parameters of family patriarchy, DHS2012

In , a comparison of the same subsamples is undertaken for the DHS1997 (except for subsamples differing for attitude to domestic violence, as the relevant parameters are absent from the DHS1997 database). Overall, the results obtained for the DHS2012 are confirmed, as the contrasted subsamples of the DHS1997 also for the most part do not differ in the significance of sex composition (except the cases when one of the subsamples is very small).

Table 6. Cox regressions for parity transitions for subsamples of women differing on one of the parameters of family patriarchy, DHS1997

6. Discussion and conclusions

The main finding of the study based on the DHS1997 and the DHS2012 is that transitions to the third and subsequent children in Kyrgyzstan are strongly conditioned by the sex composition of children already born to a woman. Women who already have at least one boy show significantly lower propensity to transition to those parities than women having no boy. This suggests that son preference shapes the fertility of the women of ages covered by the two surveys. This conclusion for Kyrgyzstan agrees with the results of Filmer et al., Citation2009, putting Central Asia together with the Middle East, North Africa and South Asia to the number of world regions, where stopping of fertility is significantly more probable when a couple has no girls than when a couple has no boys. Also, results of the analysis put Kyrgyzstan in line with some post-Soviet countries outside Central Asia, such as Armenia and Moldova, where the sex composition of children already born has been reported to be significant for transition to certain parities (Billingsley, Citation2011).

At the same time, we have seen that women differing on parameters which indicate gender relations in their families demonstrate nearly the same level of son preference in actual fertility behaviour. This result is somewhat unexpected, given the extensive evidence that son preference arises from the subordinate position of woman in her family and the society (see Section 1). However, Kyrgyzstan is not the first country where family-level characteristics of gender relations do not appear to be relevant for the degree of son preference. Javed and Mughal (Citation2020), using an analytical technique close to ours, come up with a similar conclusion for Pakistan.

A possible explanation of the low contrast between son preference in groups of women differing on gender relations in their families is related to the results on contraceptive use outlined in the previous section. As we have seen there, odds of contraceptive use are positively related with the number of boys already born to a woman. Note that similar results were obtained in studies on some other countries where son preference exists, but is not implemented by sex-selective abortions (cf. Yount et al., 2000 for Egypt; Altindag, Citation2016 for Turkey; Channon, Citation2017 for Pakistan). At the same time, the analysis has shown that the odds of contraceptive use are negatively related to some indicators of gender inequality in a family. One could speculate, therefore, that gender inequality in a family complicates the implementation of son preference, and in this way, the expected contrasts on the degree of son preference between families with different degrees of gender inequality are partly neutralised.

This, however, does not explain why son preference does not become significantly lower in families where strict gender asymmetries are not observed. It could be suggested that the desire to have a son can come not as much from the parents’ personal attitudes and values than from norms operative in the society as a whole. Among the society-level norms discussed in Section 2, son preference can be supported by patrilineal order of inheritance, by obligations of married daughters to become intensively involved in domestic work in the in-laws’ household and well as by special tasks and responsibilities of daughter’s parents at her marriage. These all are factors external to the parents’ family, but they are likely to be taken into consideration in reproductive decisions (cf. Brunson, Citation2010 reporting the decisive role of patrilinearity accepted at the level of society as a whole for son preference in Nepal in the context of weakening gender asymmetries in relations between spouses). If these family external factors are of high relevance for son preference, one could expect differences in son preference between parts of the country differing in patterns of family relations. Since interregional differences in gender practices are expected for Kyrgyzstan, partly conditioned by differences of the ethnic composition of the population of its regions (cf. Agadjanian & Dommaraju, Citation2011), this could be a question for further research. The relative weight of family-internal and family external factors for son preference is of interest also for other countries where son preference has been reported. Available studies which compare the significance of family-internal and family-external factors for son preference concentrate on fertility desires (cf. Pande & Astone, Citation2007 for India). To the best of my knowledge, this issue for son preference in actual fertility behaviour has not been addressed so far.

Another problem which needs a separate study concerns relation between son preference in actual and desired (and/or intended) fertility. As seen in Spoorenberg (Citation2018), the desire to have one more child is stronger among Kyrgyzstan women who have only one boy compared to women already having two boys. This asymmetry generally was not observed for actual fertility. Studying contrasts between patterns of son preference in actual and desired fertility allows us to figure out what sex preferences are relevant for parity transitions and in this way for total fertility and what remain inactive for actual reproduction trends in the country.

Although my study puts some interesting questions for further research, it has obvious limitations. As already mentioned, for some parameters on which the subsamples were built, time-constant nature may be to some extent disputable. Also, modelling son preference for women of all available ages could conceal possible intergenerational contrasts.

Acknowledgements

The article is based on research conducted under government contract with Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration. The author is thankful to Vladimir Kozlov for much help and valuable discussions during the research. All remaining errors are author's full responsibility.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 On economic and social aspects of labour migration from Kyrgyzstan, see Rocheva & Varshaver (Citation2017) and Wang et al. (Citation2019). In the absence of reliable statistics on labour migration, exact per cent of women who have had this experience is hard to determine.

2 One of the reviewers has kindly drawn my attention to considerable fluctuations of SRBs assessed for different calendar years in the DHS2012 final report. Fluctuations of annual SRBs attested by the DHS1997 also appear to be quite serious (between 75.8 for 1995 and 133.8 for 1987). Such fluctuations in both surveys, however, may well be due to relatively small samples of births reported by these surveys for each year. Note that SRBs calculated for all births to women covered by these surveys fall within the ‘natural’ limits (106.1 for the DHS1997 and 104.5 for the DHS2012). Given this, I assume that both surveys do not produce a serious bias for sex composition of children at the overall sample level.

3 As explained in Section 2, higher education did not imply a high level of autonomy for a woman in post-Soviet Kyrgyzstan. Nevertheless, we assume that husband’s outranking his wife in educational level fits the traditional gender asymmetries, independently upon exact advantages provided by higher education.

4 Note that this distribution is not the same as was discussed in Section 2 for the whole sample of the DHS2012.

References

- Agadjanian, V., & Dommaraju, P. (2011). Culture, modernization, and politics: Ethnic differences in Union formation in Kyrgyzstan. European Journal of Population, 27(1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-010-9225-7

- Agadjanian, V., Dommaraju, P., & Glick, J. (2008). Reproduction in upheaval: Ethnic differences in union formation in Kyrgyzstan. Population Studies, 62(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470802045433

- Agadjanian, V., Dommaraju, P., & Nedoluzhko, L. (2013). Economic fortunes, ethnic divides, and marriage and fertility in Central Asia: Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan compared. Journal of Population Research, 30(3), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-013-9112-2

- Altindag, O. (2016). Son preference, fertility decline, and the non-missing girls of Turkey. Demography, 53(2), 541–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0455-0

- Arnold, F., Choe, M., & Roy, T. (2002). Son preferences, the family building process and child mortality in India. Population Studies, 52(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000150486

- Asadullah, M., Mansoor, N., Randazzo, T., & Wahhaj, Z. (2021). Is son preference disappearing from Bangladesh? World Development, 140, 105353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105353

- Asadullah, M., & Wahhaj, Z. (2019). Early marriage, social networks and the transmission of norms. Economica, 86(344), 801–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12291

- Basu, D., & de Jong, R. (2010). Son targeting fertility behavior: Some consequences and determinants. Demography, 47(2), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0110

- Billingsley, S. (2011). Second and third births in Armenia and Moldova: An economic perspective of recent behavior and current preferences. European Journal of Population, 27(2), 125–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-011-9229-y

- Bongaarts, J. (2013). The implementation of preference for male offspring. Population and Development Review, 39(2), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00588.x

- Bras, H., & Schumacher, R. (2019). Changing gender relations, declining fertility? An analysis of childbearing trajectories in 19th-century Netherlands. Demographic Research, 41(30), 873–912. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.41.30

- Brunson, J. (2010). Son preference in the context of fertility decline: Limits to new constructions of gender and kinship in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning, 41(2), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00229.x

- Channon, M. D. (2017). Son preference and family limitation in Pakistan: A parity- and contraceptive method-specific analysis. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 43(3), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1363/43e4317

- Chowdhury, M. (1994). Mother’s education and effect of son preference on fertility in Matlab, Bangladesh. Population Research and Policy Review, 13(3), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01074337

- Chowdhury, M., & Bairagi, R. (1990). Son preference and fertility in Bangladesh. Population and Development Review, 16(4), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.2307/1972966

- Chung, W., & Das Gupta, M. (2007). The decline of son preference in South Korea: The roles of development and public policy. Population and Development Review, 33(4), 757–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00196.x

- Das Gupta, M., Zhenghua, J., Bohua, L., Zhenming, X., Chung, W., & Hwa-Ok, B. (2003). Why is son preference so persistent in east and South Asia? A cross-country study of China, India and the Republic of Korea. Journal of Development Studies, 40(2), 153–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380412331293807

- Dommaraju, P., & Agadjanian, V. (2018). Marital instability in the context of dramatic social change: The case of Kyrgyzstan. Asian Population Studies, 14(3), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2018.1512206

- Filmer, D., Friedman, J., & Schady, N. (2009). Development, modernization, and child-bearing: The role of family sex composition. World Bank Economic Review, 23(3), 371–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhp009

- Grogan, L. (2018). Strategic fertility behaviour, early childhood human capital investments, and gender roles in Albania. IZA Institute for Labour Economics Discussion Paper Series, 11937, November 2018.

- Guilmoto, C. Z. (2009). The Sex ratio transition in Asia. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 519–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00295.x

- Guilmoto, C. Z. (2012). Son preference, sex selection, and kinship in Vietnam. Population and Development Review, 38(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00471.x

- Ismailbekova, A. (2014). Migration and patrilineal descent: The role of women in Kyrgyzstan. Central Asian Survey, 33(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2014.961305

- Ismailbekova, A. (2016). Constructing the authority of women through custom: Bulak village, Kyrgyzstan. Nationalities Papers, 44(2), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1081381

- Javed, M., & Mughal, M. (2020). Preference for boys and length of birth intervals in Pakistan. 2020. hal-02293629v2

- Kabeer, N., Huq, L., & Mahmud, S. (2014). Diverging stories of “Missing women” in South Asia: Is son preference weakening in Bangladesh? Feminist Economics, 20(4), 138–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.857423

- Kandiyoti, D. (2007). The politics of gender and the Soviet paradox: Neither colonized, nor modern? Central Asian Survey, 26(4), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634930802018521

- Kazenin, K., & Kozlov, V. (2020). What factors support the early age patterns of fertility in a developing country: The case of Kyrgyzstan. Vienna Yearbook for Population Research, 18, 185–213. https://doi.org/10.1553/populationyearbook2020.res04

- Kim, D.-S. (2004). Missing girls in South Korea: Trends, levels and regional variations. Population (English Edition, 2002), 59(6), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.406.0865

- Landmann, A., Seitz, H., & Steiner, S. (2017). Patrilocal residence and female labor supply. IZA Discussion Paper No. 10890.

- Liebert, S. (2010). Irregular migration from the former Soviet Union to the United States. Routledge.

- Mason, K. O. (1987). The impact of women's social position on fertility in developing countries. Sociological Forum, 2(4), 718–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01124382

- Mason, K. O., & Smith, H. L. (2000). Husbands’ versus wives fertility foals and use of contraception: The influence of gender context in five Asian countries. Demography, 37(3), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648043

- Miller, B. D. (2001). Female-selective abortion in Asia: Patterns, polices, and debates. American Anthropologist, 103(4), 1083–1095, https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2001.103.4.1083

- Morgan, S. P., & Niraula, B. B. (1995). Gender inequality and fertility in two Nepali villages. Population and Development Review, 21(3), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137749

- Murphy, R., Tao, R., & Lu, X. (2011). Son preference in rural China: Patrilineal families and socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review, 37(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00452.x

- Nedoluzhko, L., & Agadjanian, V. (2015). Marriage, childbearing, and migration: Exploring interdependences. Demographic Research, 22(7), 159–188. https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2010.22.7

- Nedoluzhko, L., & Andersson, G. (2007). Migration and first-time parenthood: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan. Demographic Research, 17, 741–774. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.25

- Pande, P. R., & Astone, M. R. (2007). Explaining son preference in rural India: The independent role of structural versus individual factors. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-006-9017-2

- Rocheva, A., & Varshaver, E. (2017). Gender dimension of migration from Central Asia to the Russian Federation. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 32(2), 87–135. https://doi.org/10.18356/e617261d-en

- Samari, G. (2017). First birth and the trajectory of women’s empowerment in Egypt. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(S2), 362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1494-2

- Sathar, Z. B., Crook, N., Callum, C., & Kazi, S. (1988). Women's status and fertility change in Pakistan. Population and Development Review, 14(3), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/1972196

- Schoumaker, B. (2014). Quality and consistency of DHS fertility estimates, 1990 to 2012. ICF International.

- Spoorenberg, T. (2013). Fertility changes in Central Asia since 1980. Asian Population Studies, 9(1), 50–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2012.752238

- Spoorenberg, T. (2017a). The onset of fertility transition in Central Asia. Population, 72(3), 473–504. https://doi.org/10.3917/popu.1703.0491

- Spoorenberg, T. (2017b). After fertility’s nadir? Ethnic differentials in parity-specific behaviours in Kyrgyzstan. Journal of Biosocial Science, 49(S1), S62–S73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932017000335

- Spoorenberg, T. (2018). Fertility preferences in Central Asia. In S. Gietel-Basten, J. Casterline, & M. K. Choe (Eds.), Family demography in Asia: A comparative analysis of fertility preferences (pp. 88–108). Edward Elgar.

- Szołtysek, M., Poniat, R., Gruber, S., & Klüsener, S. (2017). The Patriarchy Index: a new measure of gender and generational inequalities in the past (updated). MPDIR Working papers 2016-04.

- Thieme, S. (2008). Living in transition; how Kyrgyz women juggle their different roles in a multi-local setting. Gender, Technology and Development, 12(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/097185240901200303

- Wang, D., Hagedorn, A., & Chi, G. (2019). Remittances and household spending strategies: Evidence from the life in Kyrgyzstan study, 2011–2013. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(13), 3015–3036. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1683442

- World Bank Group. (2015). Poverty and economic mobility in the Kyrgyz Republic: Some insights from the life in Kyrgyzstan survey. World Bank.