ABSTRACT

Japan and South Korea are experiencing drastic declines in marriage rates. One of the main factors explaining these declines is deteriorating youth employment. This study examined the effects of youth employment on marriage timing and the moderating effects of social contexts in both countries using longitudinal data and discrete-time logit analysis. The results indicated that unmarried people, particularly men, who were not regular employees with low annual income delayed marriage; this association was moderated by educational background and family structure (parents living together, primogeniture). Comparing the two countries, Japan experiences a stronger influence on marriage from the traditional family system, and South Korea has a stronger influence from economic disadvantages. This reflects differences in the strength of the traditional family system and the degree of deterioration of youth employment in the two countries.

Introduction

In Japan and South Korea, an increasing number of people remain unmarried, a situation described as a ‘flight from marriage’ (Jones, Citation2005). In Japan in 2015, the rates of unmarried men aged 25–29 years and 30–34 years were 72.7 per cent and 47.1 per cent, respectively, while those for women were 61.3 per cent and 34.6 per cent, respectively (Cabinet Office of Japan, Citation2021). In South Korea, the same rates for men in 2015 were 90.0 per cent and 55.8 per cent, and those for women were 77.3 per cent and 37.5 per cent (Statistics Research Institute, Citation2020). Younger generations in both countries are less and less likely to see marriage as a must (Lee, Citation2019; NIPSSR, Citation2016), which magnifies differences in whether and when individuals marry based on their personal attributes. Cohabitation, an alternative to marriage, has not been widespread in either country; in addition, there are few children born out of wedlock, as having children only after getting married is a widely accepted social norm (Matsuda, Citation2020; Raymo et al., Citation2015; Suzuki, Citation2013; Tsuya et al., Citation2019). Thus, marriage decline is directly linked to decline in fertility in Japan and South Korea.

The deterioration in youth employment has been identified as one of the major factors promoting marriage decline (Blossfeld et al., Citation2005). In addition, the effect of youth employment on marriage is influenced by social contexts such as employment systems and family systems in each country.

In Japan and South Korea, despite steady economic growth, the number of young, precariously employed low-income earners is increasing (Lee & Shin, Citation2017; Matsuda, Citation2020; Piotrowski et al., Citation2015), making it difficult to get married. Japan and South Korea, neighbouring countries in East Asia, generally share a social context different from that of Western societies. This creates similarities and differences in the relationship between youth employment and first marriage in both countries. However, these matters have not been fully investigated academically.

Based on the above, this study aimed to elucidate the effects of precarious employment and low income on the delayed timing of first marriages and the moderating effects of social contexts in Japan and South Korea and examined commonalities and differences in social contexts between the two countries.

Theoretical considerations

Economic foundation affecting marriage

Youth economic conditions predict the timing of marriage in Western countries because an economic foundation remains a key requirement for family formation (Thornton et al., Citation2007). Blossfeld et al. (Citation2005) argued that globalisation destabilises the employment conditions of young people and thus delays their transition to parenthood. This increases social uncertainty, affecting decisions at the micro level, such as partnerships and parenthood, through institutional or social filters, including specific countries’ employment systems, education systems, welfare regimes, and family systems (Blossfeld et al., Citation2005).

Studies have revealed that men’s employment conditions, such as low income and precarious employment, are primary predictors of later marriages in European countries (Blossfeld et al., Citation2005; Wolbers, Citation2007) and in the United States (Burstein, Citation2007; McClendon et al., Citation2014). In Japan and South Korea, the timing of the first marriage for low-income, precariously employed men has been found to be delayed (Lee et al., Citation2021; Kim, Citation2015; Kim, Citation2017; Matsuda & Sasaki, Citation2020; Piotrowski et al., Citation2015; Yoon, Citation2012; Yoon et al., Citation2022).

On the other hand, the effects of women’s economic conditions on marriage are slightly different. According to Becker’s (Citation1973, Citation1981) theoretical model of marriage, men and women choose to marry when they are better off doing so than remaining single (rational choice). Women’s economic resources in particular affect the costs and benefits of marriage. Highly educated and high-income women are more likely to postpone family formation because such events have higher ‘opportunity costs.’ Simultaneously, however, as employment uncertainty increases due to globalisation and other factors, those with stable occupational background (stable employment and high economic power), who can more easily predict the future, are more likely to marry (Oppenheimer et al., Citation1997; Oppenheimer, Citation2003).

The effects of women’s economic power on marriage differ depending on the gender system (one type of social context). The higher economic power of women promotes women’s marriage in Northern Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where gender equality is more advanced, and suppresses it in East Asia and Southern Europe, where gender inequality is greater (Blossfeld, Citation1995; Schneider et al., Citation2019). Regarding this study’s target countries, the positive effect of women’s economic power on marriage has not generally been observed in Japan (Piotrowski et al., Citation2015). But, some recent studies have obtained the positive effect, suggesting that Japanese women also need economic power in their marriage life (Sasaki, Citation2012; Fukuda et al., Citation2020). Additionally, a study in Japan suggests that the delay in marriage for highly educated women is due to both their economic independence and their anticipated continued economic dependence on men in unequal societies (Raymo & Iwasawa, Citation2005). In South Korea, women’s economic power has not been generally observed to have a positive effect on marriage (Choi & Min, Citation2015; Kim, Citation2015; Yoon, Citation2012), but recent studies have shown that women with stable employment get married earlier (Lee et al., Citation2021; Kim, Citation2017; Yoon et al., Citation2022).

Social contexts of Japan and South Korea

Labour markets, higher education, and family systems are social contexts that may affect the impact of economic conditions on marriage in Japan and South Korea.

In Japanese employment practices, young graduates will secure a regular job at a company, following the custom to recruit new graduates immediately. Subsequently, the stable employment and income of regular employees are protected by the seniority and lifetime employment systems. Young non-regular employees have lower wages, unstable employment, and fewer opportunities to move to regular employment (Matsuda & Sasaki, Citation2020). Like Japan, there is a strict division between regular and non-regular employment in South Korea (Arita, Citation2016); non-regular employees have lower annual income and less stable employment than regular employees (Shin, Citation2021). Employment liquidity in Japan and South Korea is lower than that in Western society; hence, non-regular employment in the two countries does not act as a stepping stone toward decent regular jobs for young people, but instead that of a ‘dead-end’ trap (Lee & Shin, Citation2017).

Economic growth was once strong in both Japan and South Korea. However, it slowed in Japan after the collapse of the bubble economy in the 1990s. Young people who graduated from their highest level of schooling from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s are called ‘the lost generation’ because they have fewer employment opportunities and lower incomes than older generations. In South Korea, economic growth slowed after the International Monetary Fund crisis of 1997 and the global financial crisis of 2008. Due to harsh social conditions, the term ‘N-Po generation’ was coined in 2015, as the young generation was forced to give up on desirable employment and marriage opportunities. In addition to this slowdown in economic growth, deregulation of employment was also carried out in both countries during this period; hence, their economies have been confronted with the serious problem of sharply growing economically inequality, characterised as the ‘gap society’ in Japan, or ‘social polarisation’ in Korea (Lee & Shin, Citation2017). Comparing the two countries, the deteriorated employment experienced by the lost generation is more problematic than that experienced by subsequent generations in Japan, while the continued deterioration of youth employment is regarded as a serious problem in South Korea. Therefore, the current youth employment situation is more serious in South Korea than in Japan.

Recently, higher education has become universal in these countries. The rate of enrolment in universities and junior colleges increased from 36.3 per cent in 1990–58.6 per cent in 2020 in Japan and from 33.2 per cent in 1990–72.5 per cent in 2020 in South Korea.Footnote1 The progress of higher education in both the countries, especially South Korea, has been faster than in numerous Western countries. Consequently, a large number of highly educated people are entering the labour market simultaneously, and they cannot easily secure a job that matches their educational background.

Family systems have a pronounced effect on the transition to marriage. Suzuki (Citation2013) proposes the viewpoint that fertility is relatively high in northwestern Europe, which has a weak family culture, but is low in other regions, including East Asian countries, which have strong family ties. Traditional family systems and norms, which are also remnants of Confucian culture, continue in Japan and South Korea. East Asian countries have undergone ‘compressed modernity’ (Chang, Citation2010), and while socioeconomic modernisation is proceeding rapidly, traditional family systems are changing more slowly.

Concretely, the main characteristics of the distinct family systems of Japan and South Korea that affect marriage are as follows: First, traditional gender norms, in which household chores and childcare are considered women’s roles, remain strong. In Japan, average daily housework time in 2016 was 49 min for husbands and 4 h and 55 min for wives (Statistics Bureau of Japan, Citation2017). Similarly, in South Korea, it was 60 min for husbands and 4 h and 4 min for wives in 2019 (Statistics Korea, Citation2019). Comparing Japan and South Korea, women's family responsibilities are somewhat heavier in Japan. It is not easy for women to balance work and family while performing housework and childcare. Therefore, many women leave their jobs after marriage or childbirth. In such a society, the opportunity cost for women is high, especially for highly educated and high-income women. In this regard, Bumpass et al. (Citation2009), analysing the Japanese situation, propose the concept of the ‘marriage package,’ which means that getting married for women is closely linked to giving birth and raising children; if so, in such societies, highly educated and high-income women are aware of the high opportunity costs when they get married. McDonald (Citation2009) argued that the number of women who marry later is increasing in East Asia because the family systems are not gender equal. Furthermore, in such a society, men are strongly expected to take up the role of money-earner.

Second, the social norm that unmarried young people should be independent of their parents is weak, and they often live with their parents. Adults living with their parents account for more than 70 per cent of unmarried adults in Japan and about 60 per cent in South Korea.Footnote2 In Japan, the ‘parasite single hypothesis’ focuses on the high rate of cohabitation with parents (Yamada, Citation1999), and posits that living with parents delays marriage of young people and that unmarried young people living with their parents are economically better off because they depend on their parents. Additionally, the economic condition of young people has worsened, making it difficult for them to live separately from their parents. The effect of the living with parents on marriage has been studied in Japan and Korea (Kojima, Citation2021; Kim & Lee, Citation2019), but results are mixed.

Third, Japan has a social norm wherein the eldest son takes over the house (primogeniture), therefore, he is expected to live with his parents after marriage at the parents’ residence. Even if the married couple live separately with their parents, they are expected to take care of the parents during the latter’s old age. However, South Korea has weak primogeniture social norms (Suzuki, Citation2013), although it still has a patrilineal family system (Kim & Kim, Citation2018).

From the perspective of the ‘life course’ of the current young generation in Japan and South Korea, the characteristics of the above-mentioned three social contexts can be summarised as follows. First, they are generally less blessed with employment opportunities and have a weaker economic position than the generations who got jobs during the periods of high economic growth in their respective countries. Next, it is not easy for highly educated people to secure favourable employment opportunities because of the rapid increase in the number of young people pursuing higher education. Moreover, regarding family systems, traditional gender norms are still strong, but women are becoming more educated and their employment rates are rising, while male employment opportunities are no longer of such good quality as previously. As a practical matter, both men and women now need to earn money to keep up with costs, including within marriage. Finally, young people live together with their parents not merely based on traditional norms but also be due to the precarious economic conditions of the younger generation.

Research questions

Based on the above theory and the social contexts, this study established the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1. Do economically disadvantaged men (such as low-educated men, non-regular employees, and low-income earners) marry later? Is this effect more pronounced in South Korea?

RQ1-1. Is it difficult for highly educated people to get married unless they can earn a high income and receive a decent occupation (stable employment and employment in a large company) commensurate with their educational background? Is this tendency more pronounced in South Korea?

According to Blossfeld et al. (Citation2005), the risk of precarious employment increases for people with lower education, and their timing of marriage is delayed (RQ1). This relationship is expected to be more pronounced in South Korea than in Japan since the situation of youth employment is worse in South Korea. A rapid increase in higher education causes an oversupply of highly educated people in the labour market. Under these circumstances, well-educated young people who do not secure the job they deserve are at a disadvantage in the marriage market (RQ1-1). This tendency is expected to be more pronounced in South Korea because Korea is becoming more highly educated than Japan.

RQ2. Does women’s growing economic power have a positive effect on marriage timing as it does among men in the current young generation? Is this tendency more pronounced in Korea than in Japan?

It was assumed that unmarried women who have stable employment and earn a high income postponed the timing of marriage since their opportunity costs are high due to traditional gender norms. However, as mentioned above, the current employment situation in Japan and South Korea is worse than that of the older generation, and it seems that not only men but also women have to earn money to get a comfortable marriage life.

RQ3. Family factors such as living with parents and birth order are considered to affect young people’s timing of first marriage. Specifically, is marriage timing later for young people living with their parents than for those living separately from their parents, and for eldest sons than for others? Are these tendencies more pronounced in Japan?

Those who live with their parents may have a later marriage in Japan and South Korea. Moreover, unmarried people living with their parents will not try to get married unless their annual income is higher than unmarried people who live separately. It is noted that unmarried people who are not financially comfortable have a higher rate of living with their parents; thus, it is necessary to control the employment status and income level of unmarried people in order to clarify the unique effects of living with their parents.

The eldest son may more likely avoid getting married because marrying would oblige him to take care of his parents in the future due to primogeniture, a social norm that remains stronger in Japan than in South Korea.

Methods

Data

This study uses two (almost) simultaneous longitudinal datasets from Japan and South Korea since the late 2000s; the datasets have been used in numerous academic studies. The data for Japan is from 2007 (wave 1) to 2016 (wave 10: latest year available to the public) of the Japanese Life Course Panel Survey (JLPS-Y/M), which comprises randomly selected men and women aged 20–40 who live in Japan in wave 1, and the individual has followed up annually on subsequent waves. The Korean data is additional samples tracked since 2009; the sample was tracked from 2009 (wave 12) to 2019 (wave 22: latest year) of the Korean Labor & Income Panel Study (KLIPS). In the KLPIS, households are selected for the survey using two-stage cluster systematic sampling. Further, KLIPS data necessarily tracks all individual household members whose age is 15 years or older over time and thus keeps track of the household comprehensively. The following analysis used a sample of unmarried individuals who were 20–34 years old at the time of the first wave. The number of individuals used was 1,746 (7,853 person-years) in Japan and 917 (4,384 person-years) in South Korea. Individual attrition rates from the first wave to the last wave used in this study were 47.6 per cent for JLPS-Y/M and 69.3 per cent for KLIPS, meaning that the latter was higher.

Measures

The dependent variable was whether an unmarried individual experienced a first marriage event within two years from the time of a survey in which explanatory variables such as employment status (described below) were measured. A dichotomous indicator was equal to 1 if an unmarried individual experienced a first marriage event in the next two years, and 0 otherwise. The method to create the dependent variable is based on Matsuda and Sasaki (Citation2020); in Japan and South Korea, it takes one or two years from the time an individual decides to get married to their marriage event. Piotrowski et al. (Citation2015) considered how many years should be lagged, with a lag of 0–5 years from an employment condition at a certain point in time to the occurrence of the marriage event. The results show that the analysis is most applicable after a two-year lag.Footnote3

As explanatory variables, the variables in both the Japanese and Korean data are used in the simple format below. Thus, it becomes easier and more effective to analyse the interaction effects between the variables to answer the RQs. Specifically, the variables used in each dataset are as follows: The respondent is a university graduate or above ( = 1, 0); the employment form is regular employment including management ( = 1, 0); a respondent working at a large company with 1,000 or more employees ( = 1, 0); the respondent’s annual income (the unit is 1 million yen for Japan and 10 million won for South Korea). They were centered by gender and adjusted for each year by the consumer price index, living with parents (including living with one of the parents) ( = 1, 0), eldest son/daughter ( = 1, 0), and the respondent’s age (centered by men’s and women’s ages separately). For the risk period, dummy variables (1 year later, 2 years later, etc.) are used, which indicates the number of years that elapsed since the commencement of observation. Presence of a romantic partner ( = 1, 0) is only in the Japanese data, therefore, it is used as a reference to investigate how the effects of other explanatory variables differ from before to after controlling this variable.

Analytical strategy

Discrete-time event history analysis was used to estimate the probability of the first marriage event. The relationship between youth employment and first marriage events differs significantly between men and women in Japan and South Korea. Therefore, this study analysed men and women separately. Subsequently, to obtain the answer for the RQs, a plurality of models with different explanatory variables was conducted for each of the four samples (details will be described later). Their standard errors were adjusted using a heteroskedastic robust procedure (White, Citation1980).

Results

Results of Japanese data

summarises the descriptive statistics for the variables used. First marriage events occurred more frequently in women than in men during the observation period. Regular employees account for approximately 60 per cent, which means that the number of other employment statuses is – by no means – small. More than 70 per cent of surveyed men and women live with their parents.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

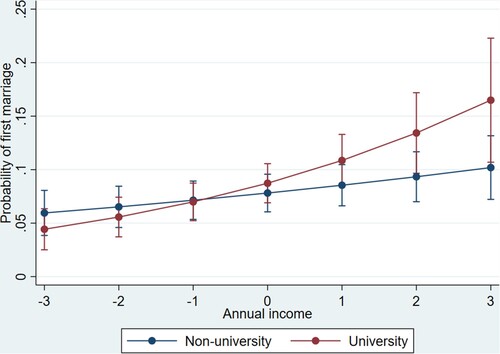

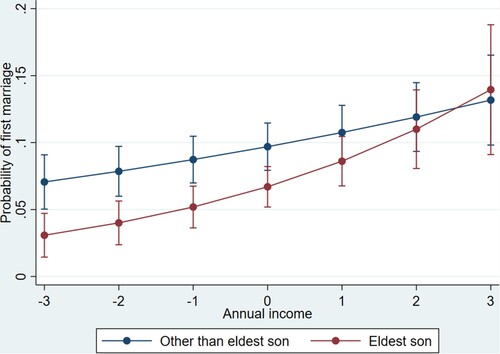

shows discrete time logit models that estimate the occurrence of the first marriage event in Japan. First, the analysis of the men’s sample highlighted the following points: Model 1 is the result of analysing only the main effects of independent variables other than company size. Regarding the variables related to employment, the higher the annual income and the more regular employees, the higher the first marriage hazard ratio. Regarding variables related to the family systems, the eldest son had a significantly lower first marriage hazard ratio than others, and the respondents living with parents have a significantly lower hazard ratio than those living separately. An analysis of a model that excluded the independent variables related to the family system of Model 1 was also performed. However, the effects of educational background, employment status, and annual income in that model are almost unchanged from Model 1 (analysis results omitted). Model 2 adds the interaction between education attainment, regular employment, and annual income to Model 1. depicts the results from Model 2 for Japanese men. We find that the first marriage hazard ratio is significantly higher for university graduates than for non-university graduates when they earn above an average income (). Conversely, university graduates are less likely to enter their first marriage if their annual income is low. Model 3 adds the interaction between family system variables and annual income to Model 1. shows that the first marriage hazard ratio for the eldest sons is significantly lower than for other sons when their annual income is less than the average. Model 4 adds company size to the variables in Model 1. The effect of the company size added was not significant.

Figure 1. Predicted interaction effect of educational background and annual income of Japanese men (odds ratio and its margin with 95 per cent Cls).

Figure 2. Predicted interaction effect of eldest son and annual income of Japanese men (odds ratio and its margin with 95 per cent Cls).

Table 2. Discrete time logit models estimating first marriage in Japan (odds ratio).

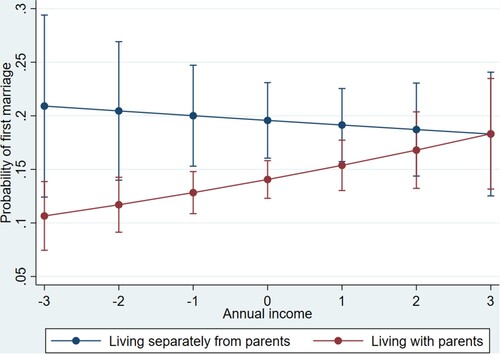

The analysis results of the Japanese women’s sample highlight the following: As assumed the results of Model 1 show that regular employees are significantly more likely to get married. Women with a high annual income do not have a low first marriage hazard ratio. Being the eldest daughter does not affect first marriage timing (as expected). However, those living with their parents have a significantly lower first marriage hazard ratio than those living separately from their parents. From Model 2, the higher the annual income of women who are not regular employees, the higher the first marriage hazard ratio; however, the higher the annual income of women of regular employees, the more moderately the first marriage hazard ratio decreases (plot diagram omitted). We graphically display the results from Model 3 for Japanese women in . For women living without parents, the first marriage hazard ratio does not increase, even if annual income increases. For women as well as Japanese men, working for a large company is not related to the timing of their first marriage (Model 4).

Figure 3. Predicted interaction effect of living with parents and annual income of Japanese women (odds ratio and its margin with 95 per cent Cls).

For reference, an analysis was performed in which romantic partner, an explanatory variable, was added to the previous models (Appendix Table A). The analysis results in the following three points: First, the presence of a romantic partner is the most effective variable for the marriage among all variables used. Second, in men, the magnitude of the effects of regular employment, annual income, and eldest son in men remain almost unchanged after controlling romantic partner. Third, controlling romantic partner makes living with parents insignificant for both men and women. Also, for women, all explanatory variables other than regular employment become non-significant after controlling romantic partner. This implies that these explanatory variables affect the first marriage via encounter with a romantic partner.

Results of Korean data

From the descriptive statistics for the Korean data (), the incidence of first marriage events during the observation period was almost the same in Japan and South Korea.

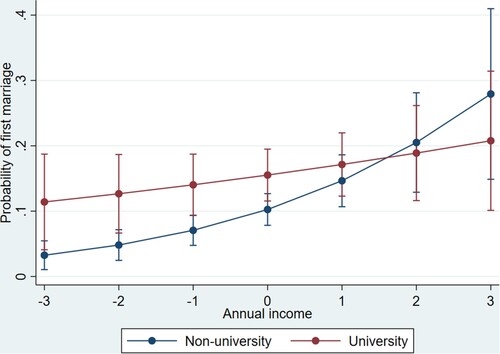

The analysis results of the Korean men’s sample show the following points (): Unlike Japanese men, Korean men who are university graduates have a first marriage hazard ratio that is 1.5 times higher than non-university graduates (Model 1). The results for Korean men are the same as for Japanese men – regular employees and those with a high annual income have a significantly high marriage hazard ratio. Men living with their parents have a first marriage hazard ratio that is 0.6 times higher than those not living with their parents (the value is almost the same as for Japanese men). However, being the eldest son does not relate to the first marriage hazard ratio. From the results of Model 2, the increase in the first marriage hazard ratio by the annual income level of non-university graduates is higher than that of university graduates. For that, university graduates have a higher first marriage hazard ratio than non-university graduates in the lower annual income group. However, when the annual income is 10 million won higher than the average, there is almost no difference between the two categories (). There was no significant interaction between the family system variables and annual income (Model 3). In addition, those who worked for large companies had more than twice the ratio of first marriage hazards (Model 4). Considered together, the above results show that Korean men have a greater advantage in the marriage market in terms of educational background, employment type, company size, and income (all the variables relate to economic power).

Figure 4. Predicted interaction effect of educational background and annual income of Korean men (odds ratio and its margin with 95 per cent Cls).

Table 3. Discrete time logit models estimating first marriage in Korea (odds ratio).

As for Korean women, few variables had a significant effect on the timing of their first marriage. This shows that the current marriage formation in South Korea depends more on the economic variables of men than women. However, the higher the woman’s annual income, the higher the first marriage hazard ratio (Model 1). Unlike the assumption, the eldest daughter had a significantly lower first marriage hazard ratio than the second and subsequent daughters. Model 4 shows that women with a university degree who worked for a large company had a high first marriage hazard ratio.

Discussion and conclusions

In response to the RQs, the following four points summarise the main findings and implications of the analysis:

First, economically disadvantaged young people, especially men, generally marry significantly later in both Japan and South Korea. This relationship is more pronounced in South Korea. This is the answer to RQ1. Specifically, Japanese and Korean men who are not regular employees or those with low annual income have a significantly lower first marriage hazard ratio. It is difficult for non-university graduate men to marry in Korea. Korean men who work for large companies tend to have an early first marriage. The effects of these variables were less clear in women than in men in both countries. In addition, university graduates with a low annual income are less likely to have their first marriage than non-university graduates among Japanese men. This result indicates a mismatch between highly educated supply and demand in the labour market. This pattern concurs with the assumption of RQ1-1. Korean women university graduates are more likely to get married when they enter a large company, which is also consistent with the perspective of supply–demand mismatch for highly educated graduates.

The above results have several implications. In recent years, in Japan and South Korea, as in Western countries, youth employment has deteriorated and become an obstacle to young people’s family formation, especially for men. Specifically, non-university graduates, those in unstable employment, and low-income earners are less likely to get married. Additionally, the rapid rise in higher education graduates in both countries has changed the supply–demand balance for highly educated people in the labour market. These relationships are more clearly observed in Japan. This has contributed to marriage decline, as described above. Furthermore, from traditional gender norms, the effects of youth employment deterioration mainly affect men’s family formation.

Second, the results show that high opportunity costs do not curb women’s marriage probability in either country, especially South Korea (RQ2). This finding is similar to the findings of Kim (Citation2017) and Yoon et al. (Citation2022), which analysed a cohort older than this study. This suggests that the higher costs associated with married life, such as house acquisition and child-rearing costs, may be associated with the results. Especially in South Korea, housing prices in urban areas have soared dramatically in recent years, and the high costs have delayed the marriage of young people (Kang & Ma, Citation2017). Therefore, women may take on a similar breadwinner role to men.

Third, observing the impact of the family system on marriage, the timing of the first marriage is significantly later for unmarried people living with parents than for those living alone, except for Korean women (RQ3). In Japan, the lower the annual income of women living with parents, the lower their first marriage hazard ratio. This is consistent with the assumption of the parasite single hypothesis. Unmarried young people tend to live with their parents in East Asian countries, and this delays their family formation. Moreover, among Japanese men, the eldest son often finds it more difficult to marry than younger siblings, especially when their annual income is relatively low. This result suggests that eldest sons are still obliged to support their parents, and they tend to be avoided by unmarried women in the Japanese marriage market. However, no such relationship was observed in South Korea. This corresponds to our expectations because Japan has a social norm for primogeniture, and while South Korea exhibits the same, it is much weaker. Furthermore, in this analysis, the marriage timing of eldest daughters was significantly later in South Korea, but the social norm of primogeniture usually applies to men; therefore, we cannot determine the reason for this finding.

Fourth, from the above three points, we can see the commonalities and differences in the background to marriage decline in Japan and South Korea. As a common feature, the deterioration in employment opportunities for young people significantly delays the timing of their first marriage, especially for men. The difference is that Japan is a society in which the family system has a strong influence on the transition to marriage, while South Korea is a society in which economic variables are more strongly related to marriage. These differences between the two countries are caused by the stronger traditional family norms in Japan and worsening youth employment situation in South Korea. Both countries are undergoing a rapid decline in marriage rates, partly due to these features of their social contexts.

Based on the above, the academic contributions of this study are as follows: First, this study revealed that youth precarious employment significantly delayed marriage timing in Japan and South Korea, using the latest high-quality longitudinal dataset. In particular, taking advantage of progressive data used, we have elucidated the effect of income levels on marriage, which has not been elucidated in detail by previous research.

Next, this study empirically shows that the East Asian social context in Japan and South Korea influences the relationship between employment deterioration and marriage decline. Specifically, numerous highly educated people are entering the labour market because of their countries’ rapid expansion of higher education. The family system (living with parents, inheritance by the firstborn) also strongly influences an individual’s marriage or non-marriage, especially in Japan. In other words, our results reveal that the relationship between youth employment deterioration and marriage decline in Japan and South Korea is progressing based on a different social context from Western countries. Of particular note is that unmarried young people often live with their parents in both countries, which slows their transition to marriage; in particular, an increasing number of young precarious workers are forced to live with their parents for financial reasons. Existing studies in both countries have not fully elucidated the effects of these social contexts.

Moreover, this study shows that the traditional family system has a stronger influence on the timing of marriage in Japan; instead, economic disadvantage has a stronger influence in South Korea. This implies that the more prominent the characteristics of a social context in a society, the stronger its influence on the relationship between youth employment and family formation. This finding is unique.

Finally, in recent years, although the size of the data used is not as large as that of US and European countries, longitudinal data for academic research have been released by countries in East Asia. Originally, longitudinal data on East Asia were collected for countries’ own purposes and were not designed for international comparisons. However, it is possible to clarify the commonalities and uniqueness of each country to some extent by aligning time, variables, and data analyses from different countries. Thus, this study elucidates the current topic in Japan and South Korea.

Limitations and challenges to the future

This study has several limitations. First, the timing of marriage might be affected by the presence or absence (i.e., availability) of a romantic partner. Japanese data included a variable about a romantic partner, but Korean data does not; therefore, this study could analyse this variable only in Japan.

Further, the deterioration of youth employment might affect not only marriage but also childbirth. The fertility rate is low in both Japan and South Korea. In the future, it will also be important to clarify whether the variables used, such as employment status, affect the declining birth rate.

Finally, as of this writing, the world is still combatting the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic may further degrade the employment conditions of numerous young people worldwide, including East Asia, thus making family formation more difficult. The data used in this study have not yet been able to cover the time of the pandemic. Elucidating the impact of the pandemic on youth employment deterioration and family formation will be an important academic subject in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 22H00917. The data of Japanese Life Course Panel Survey conducted by Institute of Social Science of the University of Tokyo were provided by the Social Science Japan Data Archive, Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo. The data of Korean Labor & Income Panel Study were provided by Korean Labor Institute.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The figures for Japan are from the annual statistics of the School Basic Survey published by the Japanese government’s e-Stat (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid = 0003147040). The figures for South Korea are from the Educational Statistical Analysis Data Collection (Korean Educational Development Institute, Citation1990).

2 Japan’s cohabitation rate was derived from individuals 18–34 years old in 2015 (NIPSSR, Citation2016); for South Korea, it was derived from 20–44 years old for the same year. (Statistics Korea, Citation2017).

3 According to the study, the number of lag years affects the results of an analysis of the effects of employment patterns, especially in women, on marriage events. In Japan, several women quit or change their jobs due to marriage.

References

- Arita, S. (2016). Sociology of employment opportunity and compensation disparity: Comparison of non-regular employment and social stratifications between Japan and Korea. University of Tokyo Press. [in Japanese].

- Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81(4), 813–846. https://doi.org/10.1086/260084

- Becker, G. S. (1981). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

- Blossfeld, H. P. (1995). The new role of women: Family formation in modern societies. Westview Press.

- Blossfeld, H. P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M., & Kurz, K. (2005). Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society: The losers in a globalizing world. Routledge.

- Bumpass, L. L., Rindfuss, R. R., Choe, M. K., & Tsuya, N. O. (2009). The Institutional context of low fertility. Asian Population Studies, 5(3), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730903351479

- Burstein, N. R. (2007). Economic influences on marriage and divorce. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 26(2), 387–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20257

- Cabinet Office of Japan. (2021). White paper of countermeasures against low fertility in reiwa 3. Naikakufu. [in Japanese].

- Chang, K. S. (2010). South Korea under compressed modernity: Familial political economy in transition. Routledge.

- Choi, P. S., & Min, I. S. (2015). Labor force status and employment quality, and marriage event for young workers: Applying the discrete-time hazard model. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 38(2), 57–83. in Korean.

- Choi, S. (2022). Coresidence with parents and intergenerational transfer of economic resources: A focus on the characteristics of unmarried adults. Health and Welfare Policy Forum, 308, 77–92. in Korean.

- Fukuda, S., Raymo, J. M., & Yoda, S. (2020). Revisiting the educational gradient in marriage in Japan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(4), 1378–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12648

- Jones, G. W. (2005). The “flight from marriage” in south-east and east Asia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36(1), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.36.1.93

- Kang, J. K., & Ma, K. R. (2017). The impact of regional housing price on timing of first marriage. Journal of the Korean Regional Development Association, 29(2), 97–110. in Korean.

- Kim, K. (2017). The changing role of employment status in marriage formation among young Korean adults. Demographic Research, 36, 145–172. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.5

- Kim, M. D., & Kim, H. L. (2018). A study on the content analysis of holiday stress shown in the news articles from 1993 to 2016. Journal of Family Relations, 22(4), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.21321/jfr.22.4.107

- Kim, P. S., & Lee, Y. S. (2019). Female adult children’s coresidence with parents and transition to marriage. Survey Research, 20(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.20997/SR.20.4.1

- Kim, S. J. (2015). Why have marriages been delayed? Korean Journal of Labour Economics, 38, 57–81. in Korean.

- Kojima, H. (2021). A review of recent literature on marital formation in Japan. The Journal of Population Studies, 57, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.24454/jps.2103001

- Korean Educational Development Institute. (1990). Statistical yearbook of education. [in Korean].

- Lee, B. H., Klein, J., Wohar, M., & Kim, S. (2021). Factors delaying marriage in Korea: An analysis of the Korean population census data for 1990–2010. Asian Population Studies, 17(1), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2020.1781380

- Lee, B. H., & Shin, K. Y. (2017). Job mobility of non-regular workers in the segmented labor markets: A cross-national comparison of South Korea and Japan. Development and Society, 46(1), 1–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90011210.

- Lee, Y. (2019). Cohort differences in changing attitudes toward marriage in South Korea, 1998–2014: an age-period-cohort-detrended model. Asian Population Studies, 15(3), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2019.1647976

- Matsuda, S.2020). Low fertility in advanced Asian economies: Focusing on families, education, and labor markets. Springer Nature.

- Matsuda, S., & Sasaki, T. (2020). Deteriorating employment and marriage decline in Japan. Comparative Population Studies, 45, 395–416. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2020-22

- McClendon, D., Kuo, J. C., Raley, L., & K, R. (2014). Opportunities to meet: Occupational education and marriage formation in young adulthood. Demography, 51(4), 1319–1344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-014-0313-x

- McDonald, P. (2009). Explanations of low fertility in East Asia. In P. Straughan, A. Chan, & G. Jones (Eds.), Ultra-low fertility in Pacific Asia: Trends, causes and policy issues (pp. 23–39). Routledge.

- NIPSSR (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research). (2016). The fifteenth national fertility survey. NIPSSR [in Japanese].

- Oppenheimer, V. K. (2003). Cohabiting and marriage during young men’s career-development process. Demography, 40(1), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2003.0006

- Oppenheimer, V. K., Kalmijn, M., & Lim, N. (1997). Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography, 34(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038286

- Piotrowski, M., Kalleberg, A., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2015). Contingent work rising: Implications for the timing of marriage in Japan. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(5), 1039–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12224

- Raymo, J. M., & Iwasawa, M. (2005). Marriage market mismatches in Japan: An alternative view of the relationship between women’s education and marriage. American Sociological Review, 70(5), 801–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000504

- Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112428

- Sasaki, T. (2012). Marriage at a time of uncertainty. Kazoku Syakaigaku Kenkyu, 24(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.4234/jjoffamilysociology.24.152

- Schneider, D., Harknett, K., & Stimpson, M. (2019). Job quality and the educational gradient in entry into marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 56(2), 451–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0749-5

- Shin, J. (2021). The effect of the first job on labor income : Studies on job mobility and wage trajectory after the first job. Economy and Society, 131, 210–252. https://doi.org/10.18207/criso.2021..131.210. in Korean.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2017). Summary of results of 2016 survey on time use and leisure activities. http://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/2016/pdf/timeuse-a2016.pdf [in Japanese].

- Statistics Korea. (2017). Population of housing census 2015. https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1PM1506&conn_path=I2 [in Korean].

- Statistics Korea. (2019). Time use survey. http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=3027 [in Korean].

- Statistics Research Institute. (2020). Social indicators in Korea. https://kostat.go.kr/boardDownload.es?bid=12302&list_no=370138&seq=1 [in Korean].

- Suzuki, T. (2013). Low fertility and population aging in Japan and Eastern Asia. Springer.

- Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Xie, Y. (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. Chicago Press.

- Tsuya, O. N., Minja, K. C., & Feng, W. (2019). Convergence to very low fertility in East Asia: Processes, causes, and implications. Springer Japan.

- White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–838. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912934

- Wolbers, M. H. J. (2007). Employment insecurity at labour market entry and Its impact on parental home leaving and family formation. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 48(6), 481–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715207083339

- Yamada, M. (1999). The age of parasite singles. Chikuma Shobō. [in Japanese].

- Yoon, J. Y. (2012). Labor market integration and transition to marriage. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 35(2), 159–184. in Korean.

- Yoon, S. Y., Lim, S., & Kim, L. (2022). Labour market uncertainty and the economic foundations of marriage in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 18(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2021.1932065

Appendix

Table A. Discrete time logit models estimating first marriage in Japan (Added romantic partner) (odds ratio).