?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Temporary internal migration is an important livelihood strategy but there have been inconsistencies in its conceptualisation and measurement which limit understanding of the phenomenon across diverse geographical contexts. This paper explores the ontological category of temporary internal migration and how it is defined and measured in eight Asian countries. We identify three broad approaches to measurement: Place of enumeration; Multilocality and Administrative measures. Using these data, we undertake comparisons of migration intensity, age profiles, and rural- to-urban flows across countries in our sample. Our findings indicate that temporary migration ranges between 0.3 to 2.9 per cent of the population—likely an underestimate of internal temporary mobility. Applying an average intensity of 1.5 per cent to all Asian countries yields an estimate of 71 million temporary internal migrants in any given year. Analysis of age profiles reveals that temporary internal migration peaks not only at young adult ages, but also at older ages in selected countries, pointing to the importance of consumption-related movements in some settings. The geographical patterns are also diverse with rural-to-urban flows matched by significant rural-to-rural and urban-to-rural flows. The paper concludes with recommendations for advancing both the conceptualisation and measurement of temporary internal migration.

1. Introduction

Migration research has focused on permanent population movement, to the exclusion of substantial and diverse temporary movements (Bell et al., Citation2015). This is changing, with growing interest in non-permanent movements including those of international guest labour (Boucher & Gest, Citation2018), seasonal agricultural labour (Gibson et al., Citation2014), and digital nomads (Müller, Citation2016). In both international (Castles & Ozkul, Citation2014) and internal migration studies (Iyer, Citation2017; Skeldon, Citation2012), temporary mobility has been characterised as a ‘triple win’, in which migrants acquire higher wages and skills, fill labour market shortages at destinations, and send remittances back to their origins. At the same time, temporary migrants can be vulnerable. This was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic with temporary migrants severely impacted (Yeoh, Citation2022). In India, tens of millions of temporary migrants returned to their home villages (Garg & Agarwal, Citation2022; Srivastava, Citation2020), as the caste system restricts seasonal migrants—an underprivileged social group (Keshri & Bhagat, Citation2010)—from establishing permanent residence and accessing social support at the destination. International temporary migrants were similarly excluded from government support in several countries due to a lack of permanent residence (Istiko et al., Citation2022).

With the growing prominence of temporary migration, attention has turned to its definition and measurement. For example, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (Citation2017) proposes a statistical definition of international circular migration in Europeas ‘ … a person who has crossed the national borders of the reporting country at least 3 times over a 10-year period, each time with duration of stay (abroad or in the country) of at least 90 days’ (p. 20). By contrast, Boucher and Gest (Citation2018) define international temporary migration based on visa class. These developments in the conceptualisation of international temporary movements have not been matched by standards for the measurement of internal temporary moves (i.e., between regions within countries) with definitions varying across countries. The absence of standardised concepts, data and measures remains a barrier to understanding the scale, composition, and distribution of temporary movements and how they vary in countries around the globe (Bell, Citation2004; Charles-Edwards et al., Citation2020).

This paper sets out to advance understanding of temporary internal migration as an ontological category, explore how temporary migration is captured by statistical instruments in selected countries of Asia, and undertake a first cross-national comparison of the scale, age composition and geography of temporary migration. Asia is an ideal test bed due to the long-established importance of temporary mobility as a livelihood strategy (Hugo, Citation1982; Keshri & Bhagat, Citation2013) and the diversity of migration regimes in the region (Boucher & Gest, Citation2018; Fielding, Citation2015). It is also the most populous continent in the world, with 60 per cent of the global population residing in the region (United Nations, Citation2022).

The paper begins with a discussion of what constitutes temporary internal migration before exploring how the temporary migration data is collected in selected countries of Asia. To do this, we draw on information held in the IPUMs data repository (Minnesota Population Center, Citation2020) and the Indian National Sample Survey (National Sample Survey Office, Citation2009) ranging from the years 2000 to 2014, which we then assess against multiple dimensions of temporary mobility (Bell, Citation2004). We then undertake a cross-national comparison of the scale, age composition, and spatial distribution of temporary movements for countries in our sample. The paper concludes by highlighting key empirical findings and making recommendations for the measurement of temporary internal migration.

2. Temporary migration as an ontological category

Migration has conventionally been defined as a permanent change of people’s residences (Bell & Ward, Citation2000; Petzold, Citation2017; Roseman, Citation1971). Temporary mobility can be defined as its complement (Bell & Ward, Citation2000), i.e., moves that do not entail a change in usual residence. The concept of usual residence is central: defined as ‘the place at which the person lives at the time of the census and has been there for some time or intends to stay there for some time’ with a threshold of 12 months based on having spent most of the previous year or intends to live there for at least 6 months (United Nations, Citation2008). Scholars frequently adopt criteria to restrict studies of temporary migration to subsets of mobility, for example by setting minimum or maximum duration thresholds. One night is the lowest bound adopted (Bell & Ward, Citation2000; Hugo, Citation1982), but is not universal, with two days (Coffey et al., Citation2014), one week (Rudiarto et al., Citation2020), two weeks (Bedford, Citation2017), one month (Keshri & Bhagat, Citation2013), and three months (Gavonel, Citation2023) used. The upper bound is commonly set at 6 months or 12 months to accord with the definition of usual residence (Charles-Edwards et al., Citation2020; Hugo, Citation1982).

Studies of temporary mobility can also be restricted to specific movement purposes. Temporary mobility can be undertaken for both consumption and production related reasons (Bell & Ward, Citation2000). The former includes tourism and visits to friends, while the latter includes seasonal agricultural work and other forms of labour mobility. In more developed countries, definitions of temporary migration commonly incorporate both production and consumption related moves (Bell & Ward, Citation2000; Smith, Citation1989). In less developed countries, the focus has been on employment moves (Elkan, Citation1967). For example, Mitchell (Citation1985) describes labour circulation as such: ‘[…] people periodically leave their permanent residence in search of wage employment at places too far away to enable them to commute daily, stay at these labour centres for extensive periods and then return to their homes’.

While a single fixed place of usual residence can be identified for large portions of the population, it is not a universal trait. Nomadic pastoralism, for example, involves the cyclical movement of individuals across territories (Dyson-Hudson & Dyson-Hudson, Citation1980). More modern manifestations of peripatetic livelihoods such as digital nomadism (Hannonen, Citation2020) and other forms of ‘multilocality’ necessitate an alternative framing of temporary migration (Greiner & Sakdapolrak, Citation2013; Vertovec, Citation2007). Multilocality recognises that people can have social, economic, and cultural ties to multiple places,which aremaintained through spatial mobility (Monsutti, Citation2006; Yeoh & Chang, Citation2001). For example,many rural households in Indonesia demonstrate a long-term commitment to bilocality with members continually circulating between home and work locations (Hugo, Citation1982). A usual residence or ‘home’ may exist as a node in the network of places inhabited by temporary migrants but may not meet the statistical criteria of usual residence.

A third approach to the definition of temporary migration is based on settlement intentions, commonly proxied via some administrative mechanism. The concept of usual residence becomes less important;rather it is the legal status that determines temporariness. This approach isused in China where temporary migration is considered a product of institutional barriers (Hukou)(Liu & Xu, Citation2017). It is also widely used in the context of international temporary migration with visa class used as an indicator of settlement intentions (Boucher & Gest, Citation2018). In practice, intentions may change over time (Connelly et al., Citation2011; Zhu & Chen, Citation2010), with temporary migrants transitioning to permanency. Moreover, as duration of stay increases, the distinction between permanent and temporary migrants becomes blurred with ‘temporary migrants’ included as permanent additions to population stocks (Australia Bureau of Statistics, Citationn.d.). Inconsistencies in the conceptualisation of temporary migration is a barrier to comparative research. While there is value in creating statistical concepts that reflect the national context (Raymer et al., Citation2015), there is a need for standardisation, or at least clear categorisation, of mobility that fall under the rubric of temporary migration.

3. Temporary internal migration data ineight countries in Asia

The long history of temporary migration data collection in Asian countries reflects the importance of mobility as a livelihood strategy. Most temporary internal migration studies rely on data from bespoke surveys (Morten, Citation2019) and fieldwork (Fan, Citation2011; Hugo, Citation1982) in a limited range of geographic settings. Outside of China and India, nationally representative statistics are rarely available. In China (Liu & Xu, Citation2017; Sun & Fan, Citation2011), census data have been used to study internal temporary migration based on hukou status. In India, the Indian National Sample Survey (National Sample Survey Office, Citation2009) collects nationally representative data on internal temporary labour migration, while the India Human Development Survey (Desai & Vanneman, Citation2012) also contains information on seasonal migrants. In addition, the Indonesian Family Life Survey (Strauss et al., Citation2004) collected retrospective information on temporary movements for people who moved more than 1 month and less than 6 months in the past, but the sample is too small for national-level analyses.

Using IPUMS, we identified seven countries collecting information on temporary migration out of 23 Asian countries on the platform (Minnesota Population Center, Citation2020). We also include data from the Indian National Sample Survey (National Sample Survey Office, Citation2009). From our sample we identify three distinct approaches to data on temporary migration: Place of enumeration (POE)measures; Multilocality measures; and Administrative measures. The questions for each country in our sample are shown in . Five countries collect data on internal temporary migration on the night of the census (Place of enumeration measure) as a by-product of de facto enumeration. The place of enumeration measure defines temporary migration as an absence from the place of usual residence. Of these, three countries (Cambodia, Mongolia, and Myanmar) enumerate both visitors away from their usual residenceFootnote1 and people who are temporarily absent from the household on census night, while two countries (Iran and the Kyrgyz Republic) collect information on people who are temporarily absent from the household, either domestically or internationally (excluded in this paper). In the latter approach, temporary migrants are likely under enumerated as it does not consider lone person and whole household mobility. Three countries (India, Indonesia, Iran) collect information on multi-locality over time (Multilocality measure). The Indian National Sample Survey asks respondents whether they have moved out from the village or town for 1 month or more but less than 6 months for employment in the last year. The Iranian Census asks respondents if they lived in another residence for less than 6 months in the past year. In both instances, these questions assume a place of usual residence. The Indonesian Intercensal Population Survey asks individuals if they periodically visit their hometown and the frequency of visits. The concept of usual residence is again implicit in this definition. A single country in our sample, China, defines temporary migration using an Administrative measure, based on Hukou with individuals enumerated outside their place of registration as part of the ‘floating population’ (Lin & Zhu, Citation2022; Zhu & Chen, Citation2010). This is a settlement intention-based approach, which assumes that temporary migrants will eventually return to their place of origin.

Table 1. Description of internal temporary migration data collection in eight countries of Asia.

Differences in the definition of temporary migration are not the only barrier to comparative research. Data items vary with respect to the spatial scale at which data are collected, the interval over which mobility is captured, and the types of spatiotemporal information captured. To better understand the similarities and differences of extant measures of temporary migration, we assess the data across dimensions identified by Bell (Citation2004). These are intensity, duration, seasonality, frequency, and periodicity (elaborated below). We combine three of Bell’s spatial dimensions (distance; impact; connectivity) as spatial displacement between a single origin and destination, from which these dimensions can be derived. We also determine if information is collected on spatial circuits, i.e., movements between multiple origins and destinations. Results are discussed in the following sections and summarised in .

Table 2. Assessment of data utility across a range of dimensions.

3.1. Movement intensity

Measurement of movement intensity, i.e., how much movement, is fundamental to both understanding and comparing temporary migration across countries and over time. Measures of movement intensity can be derived for all types of measures; however, these vary with respect to the type of data collected (e.g., movers or movements); the observation interval; the spatial framework; and the type/purpose of movement. Data on the number of temporary movers is collected by all countries in the sample. In contrast, information on temporary movements is collected in six countries. Data on movements in Cambodia, Iran, Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia and Myanmar are a by-product of the Place of enumeration approach and the short observation interval (i.e., one night) which means that the number of movers and movements is equivalent. Only one Multilocality measure, the Indian National Sample Survey asks respondents to record the number of movements during the previous year. The Chinese Administrative measure only collects Hukou status on the night of the census and does not capture the number of movements.

Movement intensity is also impacted by variations in the observation interval (whether movements are observed on a single night or over a calendar year), with the longer the interval, the more movements captured. Observation intervals differ across question types. Place of enumeration measures only capture mobility on census night. By contrast, the Multilocality measures used in India and Iran ask respondents about their mobility over the previous year, while Indonesia does not specify an observation interval but asks if people return to their hometown periodically. The Chinese data (Administrative measure) capture movers based on their administrative status on Census night, but also collect information on duration of residence which can be used to limit the sample to recent movers.

The spatial framework also impacts movement intensity, with the smaller the spatial unit, the more movements captured. Place of enumeration measures capture all temporary movers enumerated away from their usual address on census night (Cambodia, Iran, Kyrgyz Republic, Myanmar, Mongolia). Multilocality and Administrative measures capture movements between towns/cities and villages (India, Indonesia and Iran) and neighbourhoods (China) while missing very local movements. These are still relatively fine-grained geographies; thus the effect on intensity is much smaller than if data were collected, for example, at the state or province level.

Another factor impacting comparisons of intensity is the purpose or type of mobility captured. While place of enumeration measure captures all temporary movements on census night, regardless of purpose, Multilocality measures are more restrictive. In the case of India, only work-related movements longer than a month are counted. In Iran, data refer to moves to second residences. Indonesia adopts a different tact, asking respondents if they return to their hometown at least once a week, once a month, every two to six months, or rarely. We exclude the last category from our analysis in this paper.

3.2. Movement duration

Movement duration refers to the length of time migrants spend in their destinations or away from their origins. While duration is used to define temporary migration in several countries, precise information on duration is not widely collected. Information on the duration of move is not generally available from Place of enumeration measures as these capture only a snapshot of mobility at a single point in time. The exception is Kyrgyz Republic, which asks for duration of absence of less than 1 month, less than 1 year and more than 1 year (zero people were enumerated in this final category). Three other countries collect information on movement duration but these lack temporal precision. India sets an upper bound of 6 months and lower bound of 1 month. Iran differentiates between moves less than 3 months and 3–6 months. China distinguishes between stays of less and greater than 6 months. For all other countries, duration must be assumed as shorter than the threshold used for the definition of usual residence which is at least six months and one day (United Nations, Citation2008).

3.3. Seasonality

No data set in our sample collects information on the precise timing of movements which would allow for measures of seasonality, i.e., the regular cyclical variation in the intensity of movements. Seasonality is important for two reasons. First, for its impact on the measurement of movement intensity. This is a particular issue for a Place of enumeration measures as censuses are commonly scheduled to minimise the number of individuals away from home (Bell & Ward, Citation2000). Second, is the impact of seasonality on demand for goods and services at destinations which can vary substantially over the course of the year (Charles-Edwards & Bell, Citation2015).

3.4. Frequency and periodicity

Temporary migration is often repetitive or cyclical in nature. Frequency refers to the number of movements undertaken by an individual over an interval. Two countries collect information on movement frequency. The Indian National Sample Survey asks respondent the number of trips undertaken in the preceding year. While the Indonesian Census asks migrants how often they return to their hometown (e.g., at least once a week, once a month, every two to six months, or rarely). Periodicity refers to the unique temporal signature of mobility by combining movement frequency with duration of absence (Taylor & Bell, Citation2012). No country in our sample collects information on duration and frequency of move which is necessary for capturing periodicity.

3.5. Spatial displacement and circuits

A key feature of both migration is its ability to redistribute population across space. To understand these impacts, information is needed on both the origin and destination of movements. This information may be in terms of simple displacement between a single origin and destination (i.e., displacement) or between multiple locations (e.g., spatial circuits). All eight countries collect some information on displacement; however, the scale varies. Of the five nations that measure all address changes on census night, only Myanmar has data on origins and destinations at multiple geographic scales (states, districts, urban and rural areas). Cambodia and Mongolia measure spatial displacement between provinces, while the Kyrgyz Republic captures displacement between districts and cities. The Iranian census does not record the destination. For Multilocality measures, India and Iran record only rural and urban status of origins and destinations, while Indonesia collects data for provinces and regencies. China’s administrative measure includes data for provinces and for urban/rural areas. No country gathers data on more complex spatial circuits.

4. Comparing internal temporary migration in a cross-national framework

4.1. How much movement?

Following cross-national studies of internal permanent migration (Charles-Edwards et al., Citation2019), we measure temporary migration intensity using crude migration intensity which is calculated as:

where M is the total number of internal temporary moves or movers, and P is the population at risk of moving.Footnote2

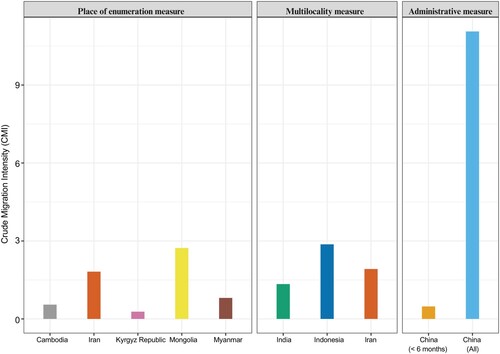

Results are shown in . For the countries in our sample, movement intensity is most readily compared for countries using the Place of enumeration measure which captures all changes in address and reference on a single night. The average CMI for this group is1.24 per cent. Mongolia has the highest intensity (2.7 per cent), perhaps reflecting its context as a traditional nomadic country, followed by Iran (1.8 per cent), Myanmar (0.8 per cent), Cambodia (0.6 per cent), and Kyrgyz Republic (0.3 per cent). The Place of enumeration measure will underestimate the intensity of temporary migration over a calendar year as it captures only a snapshot of temporary migration on a single night. At the same time, the lack of restriction with respect to movement purpose and the fact that data are collected for all changes of address inflates estimates compared with other measures in our sample.

Figure 1. CMIs of sample Asian countries by measurement type. Note. China (< 6 months) only refers to persons living in current residential area less than 6 months; China (All) refers to persons living in current residential area more or less than 6 months; persons in both groups are registered elsewhere. This applies to all the graphs.

Countries using a Multilocality measure record an average intensity of 1.6 per cent. Indonesia has the highest intensity at 2.9 per cent, followed by Iran at 1.9 per cent and India at 1.4 percent. Differences in both the observation interval and spatial framework are likely to impact comparability of these measures. The impact of differences in observation interval are difficult to resolve. While both India and Iran explicitly capture mobility behaviour over the year prior to the census, the observation interval for movements in Indonesia is more difficult to define. It is only possible to know that mobility is occurring contemporaneous with the census, but unlike the Place of enumeration data, the measure is independent of an individual’s location on census night. Differences in the geographic units also have the potential to impact these measures of intensity. In all three countries, movement is measured across settlements (e.g., villages, towns) and thus the impact is likely to be relatively small. More of an issue in comparative terms is the minimum duration threshold and explicit purpose criteria in the Indian data which exclude short duration trips (i.e., less than a month) and movements undertaken for work-related purposes, both of which act to reduce the level of intensity recorded. Indonesia and Iran also limit their collection to particularly subsets of mobility: hometowns and second residences respectively. It is worth noting however, that the Iranian Place of Enumeration measure and Multilocality measures produce similar sized estimates, despite the different concepts use.

China (Administrative measure) exhibits the highest intensity, with 11.1 per cent of its population on census night being temporary migrants. However, when movements greater than 6 months in duration are excluded, this drops to just 0.48 per cent. This highlights the limitations of administrative measures based on settlement intention. Movements may have taken place years before, blurring the boundary between permanent and temporary movements.

4.2. The age profile of temporary migrants

A key advantage of census and survey data is the wealth of person attribute data it collects. Here we focus on age at temporary internal migration. The age selectivity of permanent migration is well recognised, peaking in young adulthood, with a secondary peak in childhood tied to the migration of families, and in some cases, a retirement peak (Bernard et al., Citation2014). The age profile of temporary migration is less well understood. Work by Bell and Ward (Citation2000) in Australia based on a Place of enumeration measure has revealed that the age schedule of temporary migration was bimodal, peaking in young adulthood and again at older ages. They have suggested that the age profile was tied to distinct movement purposes, with production or work-related mobility concentrated among working ages, and consumption related movements concentrated at older ages.

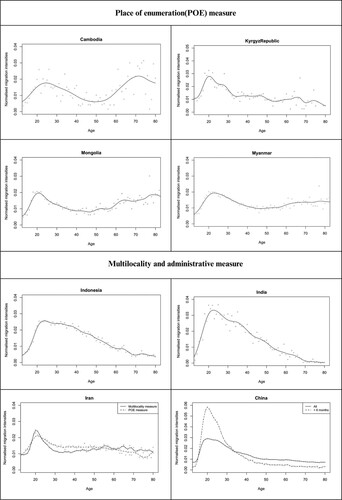

We generate age profiles by calculating age-specific migration intensities, i.e., the proportion of temporary movers at a specific age in terms of the population at risk of moving at a specific age within a country (Bell et al., Citation2002). We then normalise the age-specific migration intensities to unity to establish a standard scale and apply smoothing splines to minimise noise in the data (James et al., Citation2013). We limit profiles to individuals aged 15–80 to reduce issues associated with small numbers at younger and very old ages. We calculate the age and intensity at peak for the countries in our sample. Results are shown in .

Figure 2. Smoothed age schedules for temporary migration in sample Asian countries. Note. We normalised the age-specific migration intensities to sum to unity to establish a standard scale. ‘+' sign indicates the normalised age specific migration intensity for each country.

There is heterogeneity in the age schedules of temporary migration even among countries collecting similar types of temporary internal migration data. Among countries collecting Place of enumeration data, two distinct profiles emerge. The first is a unimodal profile (Iran, Kyrgyz Republic, and Myanmar) with ages at peak of 20, 20, and 23 respectively. The Kyrgyz Republic is the only country in our sample that also collects information on purpose of move and is dominated by movement for work (50 per cent) followed by family circumstances (28 per cent) and study (15 per cent). The remaining 7 per cent of temporary migration is due to other reasons. The Kyrgyz Republic data confirm the distinct age profiles associated with different movement purposes (Appendix 1). Work-related temporary migration peaks in young adulthood. By contrast moves for family circumstances and other purposes peak at older ages.

The second type of age profile is a bimodal profile (Cambodia and Mongolia). Movement among young adults peak at ages 26 and 20, and again at older ages, 74 and 77 years respectively. The inference that can be drawn from these is that consumption related forms of temporary migration are more prevalent compared to work-related movements in other countries in the sample and point to the importance of capturing temporary movements undertaken for diverse purposes.Footnote3

Differences also exist in the age profiles of movements captured using a multi-locality measure. India and Indonesia both exhibit a clearly unimodal migration age schedule. The peak age of mobility in India is 25,since young adults are more likely to migrate temporarily for work (Dodd et al., Citation2016). Indonesia stands out as an outlier, with the most gradual peak around 24, likely due to a significant representation of its temporary migrant population falling within the 30–40 age groups. The older age of temporary migration in Indonesia may reflect the structure of the question which specifically asks about return to the hometown. While some temporary migrants are circulating at high frequency between their place of residence and their hometown for work purposes, other trips are tied to obligations to friends and families. The older age profile, therefore, reflects placeties built at earlier ages triggering recurrent visits to their families and friends (McHugh et al., Citation1995). Temporary migration in Iran also peaks at young ages (20 years). However the peak is concentrated, and mobility remains relatively evenly distributed across older age groups. Notably, the age profile is similar to that produced by the Place of enumeration measure, showing a similar age at peak and distribution but with slightly varying intensities across other age groups.

Although China's census does not capture the reasons for temporary migration, prior research suggests that most of the floating population moves for work (Lin & Zhu, Citation2022; Zhu, Citation2007). This is reflected in the unimodal distribution with an age peak of 20. There is however a smaller peak around age 60 which may be tied to changes in the residential (but not Hukou) status of grandparents as they co-locate with children and grandchildren (Wu, Citation2014).

4.3. The geography of temporary movements

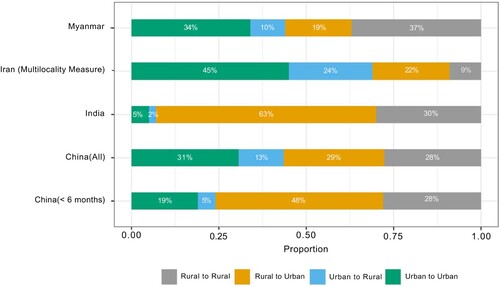

Work on temporary internal migration in Asia has frequently framed it as a rural-to-urban process, with poor rural residents circulating to urban areas for work (Deshingkar, Citation2006; Fan, Citation2011). Rural-to-rural circulation has also been observed in India, with agricultural labour moves from one village to another to participate in farm work (Visaria & Joshi, Citation2021). Little is known about the prevalence of both urban-to-ruraland urban-to-urban flows which are an important component of temporary migration in other parts of the world (Charles-Edwards, Citation2011; Müller & Hall, Citation2003). A full exploration of the geography of temporary migration is outside the scope of the current paper. Instead, we limit the analysis to an examination of the proportion of flows between rural and urban areas in four countries—China, India, Myanmar, and Iran—where information on the rural and urban status of both origins and destinations is available. Given the well-known limitations of measures of urban status (Long et al., Citation2001; Rees et al., Citation2017), these results should be interpreted with some caution.

shows the proportion of total temporary flows between rural and urban areas. There is considerable heterogeneity across the sample. Rural-to-urban flows comprise the majority of flows in India (63 per cent) and make up almost half of flows (48 per cent)shorter than six months in China. By contrast, rural-to-urban flows comprise just 22 per cent of flows in Iran and 19 per cent in Myanmar. In Myanmar, temporary internal migration is dominated by rural-to-rural flows (37 per cent) followed by urban-to-urban flows (34 per cent). One possible explanation for the prevalence of rural-to-ruralcirculation in Myanmar is a substitution effect whereby labour shortages due to emigration are being met on a seasonal basis by agricultural labour moving from other rural areas (Griffiths & Ito, Citation2016). Urban-to-urban flows may represent temporary movement across the urban hierarchy from small to large towns for higher income (Maharjan & Myint, Citation2015) but more analysis is needed.

Figure 3. Spatial patterns of temporary migration (Selected countries). Note. The definition of urban might be different across countries; these results should be interpreted with some caution. The urbanisation rate in each country is also different at the time of the census. According to the United Nations (Citation2019), the urban rate (percentageof total population) in each country is: China (2000): 35.877per cent; Myanmar (2014): 29.65 per cent; Iran (2011): 71.2 per cent; and India (2008): 30.246 per cent.

The geography of internal temporary flows in Iran is distinct from other countries in the preponderance of urban origins which account for more than two thirds of temporary movers. This likely reflects the high levels of urbanisation in Iran with 70 per cent of its total population living in urban areas (Sadeghi et al., Citation2020). The urban dominance may also reflect the question structure, focusing on second residences, which are generally located in high amenity areas (Alipour et al., Citation2017; Back & Marjavaara, Citation2017).

5. Discussion and conclusion

Despite its importance as a livelihood strategy in many parts of the world, temporary internal migration remains poorly understood outside a select few countries (e.g., India and China) and comparative studies are non-existent. This reflects ontological inconsistencies, poor data availability and significant variations in statistical collection practices. In this paper, we identified three general approaches to the definition of temporary internal migration. The first, based on individual’s absence from their place of usual residence treats temporary migration as a complement to permanent migration. This approach has the advantage of sitting neatly within population accounting frameworks as well as clearly distinguishing temporary and permanent migration. Fundamental to this definition is the assumption that individuals have a single fixed place of usual residence. This assumption does not hold for traditional nomadic populations, nor for modern forms of multilocalitysuch as digital nomadism (Hannonen, Citation2020). For other highly mobile individuals, the place of usual residence may be one node in a wider network of places periodically inhabited by the individual, such as for second homeowners. The third approach to defining temporary migration is based on administrative status. Populations are temporary based on their visa class or other forms of residency permit such as Hukou. Usual residence is incidental to this definition with temporary status potentially stretching into years.

Underlying conceptual variations are reflected in the data collected in the countries in our sample. To assert some order, we developed a tripartite classification of measurement approaches, namely Place of enumeration, Multilocality, and Administrative measureswhich broadly correspond to the categories described above. Place of enumeration measures were the most common in our sample and the most consistent with respect to their spatial and temporal framework—capturing all changes of address in a single night. With the exception of the Kyrgyz Republic, these data are extremely limited with respect to information on the duration, seasonality, frequency, periodicity, and purpose of movement. The example of the Kyrgyz Republic points to the possibility of collecting supplementary information on movement purpose and duration to advance understanding of temporary internal migration. Multilocality measures are the second most common and are explicitly designed to capture absences over an extended interval or, in the case of Indonesia, regular movement around the time of Census. Differences in questions hinder cross-national comparisons, including the setting of a minimum duration threshold and limiting movements to selected movement purposes. China is the sole country in the sample using an administrative definition of temporary migration—Hukou status. This inflates estimates as it includes movers who are long-term residents of the destination despite not having Hukou. When estimates are limited to people with a duration of residence less than 6 months, intensity drops to just 0.5 per cent of the population—broadly in line with other countries. This figure needs to be treated with caution as it likely includes temporary migrants who intend to stay at the destination long-term.

Results of the cross-national comparison of temporary migration suggest that temporary migration sits between 0.3 and 2.9 per cent of the population in Asian countries, which is lower than the estimated intensity of permanent migration observed over a five-year period (Bell et al., Citation2015). However, these are underestimates due to the short observation interval in the case of Place of enumeration data, limits to the types of mobility captured in the Multilocality estimates, and rigidity of Hukou standard adopted in the Administrative measure. Applying an average of 1.5 per cent to the total population of Asia of 4.75 billion (United Nations, Citation2022)gives an estimate of close to 71 million peopleundertaking some form of temporary internal migration periodically within the region. This number is more than twice as large as the total number of international migrants estimated each year in the region (Raymer et al., Citation2022), confirming the significance of internal temporary mobility.

The age profiles of internal temporary migration suggest a diversity of movement. Like permanent migration, temporary internal migration peaks in young adulthood. Evidence from the Kyrgyz Republic and India (which only collects information on work-related moves) appears to confirm that work is the primary motivation in these age groups. Several countries including Cambodia, Mongolia and, to a lesser extent, Myanmar show a peak in movements at older ages. These are presumably related to family circumstances or other consumption-related purposes as many of these individuals are no longer in the workforce (Bell & Ward, Citation2000). Consumption-related temporary migration at older ages has received very little attention in Asiabut is likely to become more significant as populations age. Results of the spatial analysis reveal further heterogeneity across countries in our sample. While rural-to-urban flows dominate temporary movement in India and China, rural-to-rural flows are the most common in Myanmar, while in Iran most flows originate from urban areas. Yet, these results point to significant diversity in the motivations and practice of temporary migration in Asia absent from many accounts.

The empirical results from this paper demonstrate both the significance and diversity of temporary movements in Asia. To further advance the understanding of temporary internal migration as a phenomenon, attention needs to be paid to its definition and measurement. One option is to supplement data on the place of enumeration with questions capturing purpose, duration, and the number of absences over the previous year. This approach has the advantage of consistency with the measurement of permanent migration. The disadvantage is that it does not capture the mobility of individuals for whom a single place of usual place of residence is not readily identifiable. Cross-sectional data, such as that captured by censuses, also needs to be supplemented with longitudinal data to address hitherto unanswered questions about temporary migration. For example, is there a clear duration threshold distinguishing temporary and permanent migration? Do temporary and permanent migration substitute or complement one another?

In conclusion, we hope that this article provides a better understanding of the definitions, measurement, and features of internal temporary migration in Asia. This first cross-national comparison of temporary internal migration in countries of Asia highlighted both the scale of temporary migration as well as variability in the characteristics and spatial patterns. As societies continue to progress through the demographic and mobility transition, temporary mobility is posited to become an increasingly important component of demographic change (Zelinsky, Citation1971). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vulnerability of temporary migrants to extreme shocks and brought new forms of temporary migration to public attention, for example digital nomadism and houselessness (Stewart & Sanders, Citation2023). Given the importance and growing prevalence of temporary migration, attention must be paid to both its the classification and measurement. This is not a small task, requiring effort from both researchers and statistical offices to create meaningful instruments to capture this important, yet understudied phenomenon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

IPUMS provides census and survey data from around the world integrated across time and space, with data and services available free of charge. Access to the 64th Indian National Sample Survey can be obtained through formal request procedures established by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A place of usual residence in the census usually refers to where a person has lived for more than 6 months in the last 12 months or where he/she intends to live for a longer time.

2 Both M and P are conditional on survival to the census.

3 The temporary migrants captured at the night of census in the Mongolian census include the following groups of people: people on official/business missions; temporary or seasonal workers; people on vacation or travelling for more than one week; people on industrial practice; people visiting other aimag(province)and soum(district)to meet relatives and friends; people caring for ill relativesin hospital for not more than seven days; people under police arrest.

References

- Alipour, H., Olya, H. G., Hassanzadeh, B., & Rezapouraghdam, H. (2017). Second home tourism impact and governance: Evidence from the Caspian Sea region of Iran. Ocean & Coastal Management, 136, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.12.006

- Australia Bureau of Statistics. (n.d.). Net overseas migration.https://population.gov.au/population-topics/topic-overseas-migration

- Back, A., & Marjavaara, R. (2017). Mapping an invisible population: The uneven geography of second-home tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 595–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260

- Bedford, R. D. (2017). New hebridean mobility: A study of circular migration. Dept. of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University.

- Bell, M. (2004). Measuring temporary mobility: Dimensions and issues. Proceedings of the Cauthe Conference (pp.1-29). Queensland Centre for Population Research, The University of Queensland.

- Bell, M., Blake, M., Boyle, P., Duke-Williams, O., Rees, P., Stillwell, J., & Hugo, G. (2002). Cross-national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-985X.00247

- Bell, M., Charles-Edwards, E., Ueffing, P., Stillwell, J., Kupiszewski, M., & Kupiszewska, D. (2015). Internal migration and development: Comparing migration intensities around the world. Population and Development Review, 41(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00025.x

- Bell, M., & Ward, G. (2000). Comparing temporary mobility with permanent migration. Tourism Geographies, 2(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/146166800363466

- Bernard, A., Bell, M., & Charles-Edwards, E. (2014). Improved measures for the cross-national comparison of age profiles of internal migration. Population Studies, 68(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2014.890243

- Boucher, A. K., & Gest, J. (2018). Crossroads: Comparative immigration regimes in a world of demographic change. Cambridge University Press.

- Castles, S., & Ozkul, D. (2014). Circular migration: Triple win, or a new label for temporary migration? In Global and Asian Perspectives on International Migration (pp. 27–49).Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Charles-Edwards, E. (2011). Modelling flux: Towards the estimation of small area temporary populations in Australia. PhD thesis. University of Queensland.

- Charles-Edwards, E., & Bell, M. (2015). Seasonal flux in Australia’s population geography: Linking space and time. Population, Space and Place, 21(2), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1814

- Charles-Edwards, E., Bell, M., Bernard, A., & Zhu, Y. (2019). Internal migration in the countries of Asia: Levels, ages and spatial impacts. Asian Population Studies, 15(2), 150–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2019.1619256

- Charles-Edwards, E., Bell, M., Panczak, R., & Corcoran, J. (2020). A framework for official temporary population statistics. Journal of Official Statistics, 36(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2478/jos-2020-0001

- Coffey, D., Papp, J., & Spears, D. (2014). Short-Term labor migration from rural north India: Evidence from New survey data. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(3), 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9349-2

- Connelly, R., Roberts, K., & Zheng, Z. (2011). The settlement of rural migrants in urban China - some of China's migrants are not ‘floating’ anymore. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 9(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14765284.2011.592356

- Desai, S., & Vanneman, R. (2012). India Human Development Survey-II (IHDS-II) 2011-12. India Human Development Survey (IHDS) Series.

- Deshingkar, P. (2006). Internal migration, poverty and development in Asia: Including the excluded. IDS bulletin, 37(3),88-100.

- Dodd, W., Humphries, S., Patel, K., Majowicz, S., & Dewey, C. (2016). Determinants of temporary labour migration in southern India. Asian Population Studies, 12(3), 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2016.1207929

- Dyson-Hudson, R., & Dyson-Hudson, N. (1980). Nomadic pastoralism. Annual Review of Anthropology, 9(1), 15–61. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.09.100180.000311

- Elkan, W. (1967). Circular migration and the growth of towns in east Africa. International Labour Review, 96(6), 581–589.

- Fan, C. C. (2011). Settlement intention and split households: Findings from a survey of migrants in Beijing's urban villages. China Review, 11(2), 11–41.

- Fielding, T. (2015). Asian migrations: Social and geographical mobilities in Southeast, East, and Northeast Asia. Routledge.

- Garg, A., & Agarwal, P. (2022). Analysis of rural-urban migration in India and impact of COVID-19. International Journal of Policy Sciences and Law, 1(4), 2467–2493.

- Gavonel, M. F. (2023). Are young internal migrants ‘favourably’selected? Evidence from four developing countries11. Oxford Development Studies, 51(2), 97–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2022.2156491

- Gibson, J., McKenzie, D., & Rohorua, H. (2014). Development impacts of seasonal and temporary migration: A review of evidence from the pacific and southeast A sia. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 1(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.12

- Greiner, C., & Sakdapolrak, P. (2013). Translocality: Concepts, applications and emerging research perspectives. Geography Compass, 7(5), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12048

- Griffiths, M., & Ito, M. (2016). Migration in Myanmar: Perspectives from current research. Social Policy and Poverty Research Group, Yangon.

- Hannonen, O. (2020). In search of a digital nomad: Defining the phenomenon. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 335–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00177-z

- Hugo, G. (1982). Circular migration in Indonesia. Population and Development Review, 8(1), 59–83. https://doi.org/10.2307/1972690.

- Istiko, S. N., Durham, J., & Elliott, L. (2022). (Not that) essential: A scoping review of migrant workers’ access to health services and social protection during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2981. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052981

- Iyer, S. (2017). Circular migration and localized urbanization in rural India. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 8(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425316683866

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2013). An introduction to statistical learning. Springer.

- Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2010). Temporary and seasonal migration in India. Genus, 66(3), 25–45.

- Keshri, K., & Bhagat, R. B. (2013). Socioeconomic determinants of temporary labour migration in India. Asian Population Studies, 9(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2013.797294

- Lin, L., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Types and determinants of migrants’ settlement intention inChina's new phase of urbanization: A multi-dimensional perspective. Cities, 124, 103622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103622

- Liu, Y., & Xu, W. (2017). Destination choices of permanent and temporary migrants in China, 1985-2005. Population, Space and Place, 23(1), e1963. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1963

- Long, J. F., Rain, D. R., & Ratcliffe, M. R. (2001, August). Population density vs. urban population: Comparative GIS studies in China, India, and the United States. In session S68 on “Population Applications of Spatial Analysis Systems (SIS)” at the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population Conference (pp. 18–25). Salvador, Brazil.

- Maharjan, A., & Myint, T. (2015). Internal labour migration study in the Dry Zone, Shan State and the Southeast of Myanmar. HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation Myanmar.

- McHugh, K. E., Hogan, T. D., & Happel, S. K. (1995). Multiple residence and cyclical migration: A life course perspective. The Professional Geographer, 47(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1995.251_q.x

- Minnesota Population Center. (2020). Integrated public use microdata series, international: version 7.3 [dataset]. Minneapolis: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.2

- Mitchell, J. C. (1985). Towards a situational sociology of wage-labour circulation. In R. M. Prothero, & M. Chapman (Eds.), Circulation in third world countries (pp. 30–53). Routledge.

- Monsutti, A. (2006). Afghan transnational networks: Looking beyond repatriation. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit.

- Morten, M. (2019). Temporary migration and endogenous risk sharing in village India. The Journal of Political Economy, 127(1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1086/700763

- Müller, A. (2016). The digital nomad: Buzzword or research category? Transnational Social Review :A Social Work Journal, 6(3), 344–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/21931674.2016.1229930

- Müller, D., & Hall, C. M. (2003). Second homes and regional population distribution: On administrative practices and failures in Sweden. Espace Populations Sociétés, 21(2), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.3406/espos.2003.2079

- National Sample Survey Office. (2009). Migration in India 2007-2008. Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation, Government of India.

- Petzold, K.. (2017). Mobility experience and mobility decision-making: An experiment on permanent migration and residential multilocality. Population, Space and Place, 23(8), e2065. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2065

- Raymer, J., Guan, Q., Shen, T., Wiśniowski, A., & Pietsch, J. (2022). Estimating international migration flows for the Asia-pacific region: Application of a generation–distribution model. Migration Studies, 10(4), 631–669. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnac023

- Raymer, J., Rees, P., & Blake, A. (2015). Frameworks for guiding the development and improvement of population statistics in the United Kingdom. Journal of Official Statistics, 31(4), 699–722. https://doi.org/10.1515/jos-2015-0041

- Rees, P., Bell, M., Kupiszewski, M., Kupiszewska, D., Ueffing, P., Bernard, A., … Stillwell, J. (2017). The impact of internal migration on population redistribution: An international comparison. Population, Space and Place, 23(, 6 ), e2036.https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2036.

- Roseman, C. C. (1971). Migration as a spatial and temporal process. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 61(3), 589–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1971.tb00809.x

- Rudiarto, I., Hidayani, R., & Fisher, M. (2020). The bilocal migrant: Economic drivers of mobility across the rural-urban interface in central java, Indonesia. Journal of Rural Studies, 74, 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.12.009

- Sadeghi, R., Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., & Shahbazin, S. (2020). Internal migration in Iran. In M. Bell, A. Bernard, E. Charles-Edwards, & Y. Zhu (Eds.), Internal migration in the countries of Asia (pp. 295–317). Springer.

- Skeldon, R. (2012). Going round in circles: Circular migration, poverty alleviation and marginality. International Migration, 50(3), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00751.x

- Smith, S. K. (1989). Toward a methodology for estimating temporary residents. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(406), 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1989.10478787

- Srivastava, R. (2020). COVID-19 and circular migration in India. Review of Agrarian Studies, 10(1), 164–180.

- Stewart, S., & Sanders, C. (2023). Cultivated invisibility and migrants’ experiences of homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Sociological Review, 71(1), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261221100359

- Strauss, J., Beegle, K., Sikoki, B., Dwiyanto, A., Herawati, Y., & Witoelar, F. (2004). The third wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS3): Overview and field report. WR144/1-NIA/NICHD. RAND Labor and Population Working Paper Series.

- Sun, M., & Fan, C. C. (2011). China's permanent and temporary migrants: Differentials and changes, 1990– 2000. The Professional Geographer, 63(1), 92–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2010.533562

- Taylor, J., & Bell, M. (2012). Towards comparative measures of circulation: Insights from indigenous Australia. Population, Space and Place, 18(5), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.695

- United Nations. (2008). Principles and recommendations for population and housing censuses revision 2. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division.

- United Nations. (2019). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

- United Nations. (2022). World population prospects 2022: Summary of results. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2017). Defining and measuring circular migration.https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/publications/2016/ECECESSTAT20165_E.pdf

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Circular migration: The way forward in global policy? Working Paper No. 4. Oxford: International Migration Institute.

- Visaria, L., & Joshi, H. (2021). Seasonal sugarcane harvesters of Gujarat: Trapped in a cycle of poverty. Journal of Social and Economic Development, 23(1), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00120-2

- Wu, Q. ((2014). An exploratory study of the livingstatus of the migratory bird elders taking care of grandchildren in the urban. South China Population, 29(3), 51–61.

- Yeoh, B. S. A. (2022). Is the temporary migration regime in Asia future-ready? Asian Population Studies, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441730.2022.2029159

- Yeoh, B. S. A., & Chang, T. C. (2001). Globalising Singapore: Debating transnational flows in the city. Urban Studies, 38(7), 1025–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980123947

- Zelinsky, W. (1971). The hypothesis of the mobility transition. Geographical Review, 61(2), 219–249. https://doi.org/10.2307/213996

- Zhu, Y. (2007). China's floating population and their settlement intention in the cities: Beyond the hukou reform. Habitat International, 31(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2006.04.002

- Zhu, Y., & Chen, W. (2010). The settlement intention of China's floating population in the cities: Recent changes and multifaceted individual-level determinants. Population, Space and Place, 16(4), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.544

Appendix

Appendix 1. Smoothed age schedules by purposes in Kyrgyz Republic.

Note.'+’ sign indicates the normalised age specific migration intensity under each purpose.