ABSTRACT

Indigenous peoples in Latin America are historically underrepresented in elected bodies. In 2009, Bolivia introduced a new mechanism for direct representation to counteract this systematic representation gap, securing 7 of 130 seats (5.4%) in the national parliament for indigenous peoples of the lowlands. The reform was part of a series of implementation conflicts related to a new vision of plurinational state-building, included in the new 2009 Constitution. Although most indigenous organizations were seeking a ‘power-sharing’ agreement with direct representation for all indigenous nations, the new government, led by President Evo Morales, successfully intervened in favor of a minority protection scheme. Furthermore, for the direct representatives, the room to maneuver left was severely limited, leaving little space to act on behalf of their minority constituencies. Curiously, this reduced version of direct representation is nonetheless the most advanced in Latin America. The Bolivian case provides important lessons on the ‘de-monopolization’ of political parties as a key factor in the effective representation of indigenous peoples in parliament, as well as on the importance of a goal-oriented design for electoral mechanisms focusing on substantive representation.

The emergence of direct seats in Bolivia

In recent decades, several Latin American countries have attempted to respond to the systemic exclusion and silencing of indigenous peoples in public institutions by introducing specific measures to strengthen their participation in legislative bodies. Successively, Colombia (1989), Venezuela (1999), Peru (2002), Bolivia (2009), and Mexico (2017) established a fixed number of seats in the national or sub-national legislature for indigenous peoples (Fuentes and Encina Citation2018, 10–16).Footnote1 These changes in the representative system were often connected to broader state reforms, which recognized indigenous rights and sought to adapt institutional frameworks to a pluriethnic reality (Barié Citation2004). Direct representation of indigenous peoples in national parliaments and assemblies is often seen as one of several other concrete measures ‘beyond mere declarations’ (Schavelzon Citation2012, 525), that attempt to respond to what Assies, van der Haar, and Hoekema (Citation1999) once called the ‘challenge of diversity.’

Bolivia is widely considered the most advanced example of direct representation in Latin America and has received positive mention for its electoral reforms based on the recognition of the pluricultural structure of Bolivian society (Cabrero Miret Citation2013; MOE OAS Citation2014; MOE UE Citation2009). Since the establishment of the new mechanism of reserved seats in 2009, 7 of 130 seats (5.4%) in the national parliament have been secured for minority indigenous peoples. This percentage is in line with the overall share of minority indigenous groups within the total population, which stands at approximately 4.6% (INE Citation2012, 31). The mechanism has been applied in three national (2009, 2014, 2019) and two subnational elections (2010, 2015).

Direct seats are filled by means of competitive elections in special districts; indigenous organizations can nominate candidates according to customary norms and procedures. This only applies to smaller minorities and excludes Quechua- and Aymara-speaking indigenous peoples of the Andean region, which represent much higher percentages of the population, 18.5% and 17% respectively (INE Citation2012, 31). Thus, for the first time, Bolivia broke with the electoral principle of proportionality, resulting in a guaranteed representation of indigenous minorities.

In this article, the discussion around direct representation mechanisms for indigenous peoples in Bolivia is used as a case study to reflect on the practical implications and consequences of such legal measures, in order to identify the factors that make dedicated seats more effective and meaningful. In short, how can a plurinational state ensure that the interests of indigenous constituencies are adequately represented and that direct representatives act on behalf of their constituents? What are the desirable outcomes of direct representation? These questions are not only relevant in the context of current discussions on identity politics and demands for justice in Latin America, but also shed light on the complex relationship between indigenous peoples and ostensibly progressive governments, which claim to represent precisely those who have historically been excluded. The following analysis will hopefully also contribute to the emerging discussion on the origins of the collapse of the government in November 2019, when Evo Morales and his cabinet were forced to resign.

The Bolivian reform of the representation system is the result of an agitated decade, from approximately 1999 to 2009, that witnessed the social mobilization and empowerment of different subaltern groups (Calderón Citation2004; Laserna and Nikitenko Citation2013). During this phase, the concept of a ‘plurinational state,’ already extant in the discourse of various indigenous organizations and intellectual circles in the Andean region, was developed further and transformed into the ideological basis for a new nation-building project. As a political vision, plurinationality cuts across a whole range of issues, including the recognition of indigenous territories, the establishment of autonomous governments, open consultation mechanisms, the administration of justice according to local culture, and buen vivir (good living) as a new guiding principle for development, among others (Resina de la Fuente Citation2012, 139–147; Schavelzon Citation2015). Thus plurinationality, as eventually formalized in the new Bolivian Constitution, explicitly challenges the dominant notion of the nation-state as it has been widely applied in Latin America since independence (Barié Citation2014).Footnote2

This period is also closely related to the rapid growth of the Movement towards Socialism (MAS-IPSP) and its consolidation as a hegemonic party. From its origins, MAS was conceived as a ‘political instrument’ of different social organizations, and not as a conventional party, which is also reflected in the second part of its acronym, IPSP: Political Instrument for the Sovereignty of the People.Footnote3 The common bond between members seemed to be the willingness to fight against the growing marginalization and discrimination resulting from a closed political system and a long series of neoliberal economic measures.

Since its foundation, the coca growers have been one of the most influential organizations in the MAS. Many of them are originally miners who, within the framework of the ‘New Economic Policy’ initiated in 1985, became unemployed and were forced to seek their luck as colonizers in the tropics of Cochabamba (Postero Citation2010, 21–22). The indigenous peoples of the lowlands, whose growing political awareness had been expressed during the 500 Years of Resistance Campaign from 1989 to 1992, also joined the struggle and complemented the class-based views of the trade unions with the perspectives of historical exclusion and the experience of displacement from their territories (Zuazo Oblitas Citation2009, 37).

MAS’s speeches revolve around the defense of sovereignty and national resources such as the coca leaf and hydrocarbons against external intervention. These nationalist and anti-imperialist components were often complemented by a discourse in favor of the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples and by a socialist rhetoric, introduced mainly by urban intellectual groups (Barrientos Garrido Citation2010, 35–36).Footnote4

Research on indigenous districts and reserved seats in Bolivia – despite its particular features and the innovative aspirations underlying it as a political project – is rather limited. For the most part, these new mechanisms of representation are only considered en passant as part of broader historical and political analyses of the constitutional process and of the new institutions created during the implementation phase (Komadina Citation2016; Schavelzon Citation2012; Zegada, Arce, and Canedo Citation2011; Zegada and Jorge Komadina Citation2014). Certain qualitative studies consider the role and participation of indigenous and peasant deputies in the new plurinational Assembly, but do not specifically focus on direct representation (Chávez Citation2013). Similarly, Htun and Ossa (Citation2013) compare participation rights gained by women’s organizations and indigenous peoples in contemporary Bolivia; Tamburini and Bascopé Sanjinés (Citation2010) analyze how indigenous participation is affected by changing legal frameworks, especially electoral laws. Finally, there is a growing literature of rather formal descriptions of indigenous election mechanisms in Bolivia, mainly published by official institutions (Díez Astete Citation2012).

Conversely, the research presented here combines a theoretical-legal analysis of current discussions on representation with a political historical recounting of the conflict over the new mechanism of reserved seats in Bolivia. Beginning with a short overview of the longstanding debate in political philosophy about how democratic regimes should handle the challenge of insufficient minority representation, three typical responses are isolated: formal equality, minority protection, and power-sharing. The minority protection approach has heavily contributed to the development of an international legal framework with a broad repertoire of instruments to promote the participation of disadvantaged groups.

As we will see in the section that follows, the question of direct participation in Bolivia was part of a series of conflicts related to implementing different visions on how to put plurinational nation-building into practice. Accordingly, most indigenous organizations sought a power-sharing model (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010) with direct representation of all indigenous peoples in the legislature without party intermediation, while the new government intervened in favor of a model of minority protection in which the logic of political parties continued to define the rules of the game. The government finally imposed a much weaker interpretation of the constitutional postulate of plurinationality and transformed it in a reductionist way into laws and public policies that limited the direct representatives’ room to maneuver.

Within these implementation conflicts,Footnote5 different conceptions of state-building resonated: on the one hand, a more top-down and statist perspective, emphasized by most leaders within the new government, and on the other, a bottom-up ‘constructivist’ conception, driven by certain indigenous organizations of the lowlands.Footnote6

In the third section, I focus on the linkage between MAS and indigenous representatives as a relevant factor in the failure of the original proposal by the indigenous and the limited impact of the final measure. I conclude with lessons learned to be considered when designing or adapting mechanisms of direct representations for indigenous peoples.

The representation challenge

Globally, ethnic, cultural, and religious minorities are underrepresented in elective bodies, especially on the national level (Bird Citation2003, 2; Togeby Citation2008, 325–26) – a general trend that also applies to Latin America, where representatives tend to be members of the economic and cultural elite (Serna Citation2018). Conversely, indigenous peoples, who account for ‘the highest and “stickiest” poverty rates in the region’ (Hall and Patrinos Citation2014, 344) are members of one of the most marginalized groups in terms of political participation in the region. Approximately 10% of the population in Latin America is indigenous – 30 to 50 million inhabitants.Footnote7 Despite increased visibility in the last two decades and strong mobilization, ‘their political participation, particularly among women, is still low’ (Azevedo and Basz Citation2013). In fact, according to data collected by Hoffay and Rivas (Citation2016), a significant ‘representation gap’ persists, calculated as the difference between the percentage of the indigenous population and the percentage of seats in Congress held by deputies who self-identify as indigenous. In no country in the region does the percentage of indigenous peoples even roughly reflect the composition of parliament.Footnote8

Certainly, statistics on minorities and their participation are not necessarily comparable and should be taken as purely indicative – particularly since there is still no exclusive definition of minorities in international law (Kugelmann Citation2007, 237). The definition of minority applied in each country varies significantly and can be based on ethnicity, language, religion, nationality, caste, and tribe (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 262). The working definition developed in 1979 by Capotorti (Citation1979, 96), the former Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, is still the best starting point for any analysis on this subject.Footnote9

Indigenous peoples are not necessarily numerical minorities in their countries and often do not consider themselves minorities. As a result of a longstanding mobilization and lobbying, they are usually referred to in the present discourse as ‘peoples,’ implying inter alia the right to freely determine their political status, as guaranteed by article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007).Footnote10 There are obvious differences between understandings of minorities and indigenous peoples in terms of their conceptual genesis and the political implications thereof. In practice, however, indigenous peoples often appeal to a minority protection framework when defending their rights (Verstichel Citation2009, 14). Additionally, some analysts question the ‘distinctiveness’ of the category of indigenous peoples in international law as suggested, for instance, by Anaya (Citation1996).Footnote11 Minority’s rights and indigenous people’s rights, despite pertaining to different discussion strands, are therefore still connected and interwoven, especially when it comes to the question of participation in public life.

A fundamental question thus remains: is action needed when societal groups are systematically absent from or underrepresented in democratically elected bodies? Simplifying a rather longstanding and ramified debate in political philosophy, for the sake of this case study, we can identify three basic positions (Bird Citation2003; Dovi Citation2017; Verstichel Citation2009).

Exponents of formal equality emphasize the uniform application of rules and procedures (one person, one vote).

Supporters of minority protection, which includes many international agencies, suggest establishing special representation mechanisms, including direct seats, in order to ensure that certain groups can live their cultural identity without harmful intrusion from the dominant society.

Finally, advocates of a power-sharing model propose a complete reconfiguration of the system of representation with the goal of stability, justice, and peacebuilding.

Formal equality

According to the rather widespread Anglo-American tradition in political philosophy, ‘the chronic underrepresentation of historically marginalized groups is not problematic’ (Verstichel Citation2009, 65), negating the need for any corrective measure. From this perspective, cultural or religious identity should not have mayor relevance in the design of electoral systems and the link between representative and constituency should mainly consist of a shared political affinity (Gutmann and Taylor Citation1994). The idea of ‘mirror representation’ or ‘descriptive representation,’ which postulates that parliaments should ‘reflect’ the characteristics of their constituencies, is considered counterproductive and even absurd, as the legislature would be reduced to a ‘replica’ or simply a statistical sample of society, ‘such that children represented children, lunatics represented lunatics’ (Bird Citation2003, 2; Pitkin Citation1967, 73).

Instead, the principle of ‘one person, one vote’ and the basic guarantees of freedom of assembly and association culminate – in a democratic system – in the ideal that all individuals are able to promote their positions, ideas, and beliefs in a ‘neutral camp’ and organize and mobilize interest groups around them. As a result of the application of the principles of formal equality, certain groups within minority communities are often not present in legislative bodies, as they are unable to sway sufficient numbers of followers and consequently do not obtain a sufficient number of votes. In any case, representatives should not be elected to bring forward the interests of a particular group, but to freely debate and make decisions on behalf of the nation as a whole.Footnote12

Minority protection

States are far from culturally neutral. Implicitly, they promote a certain model of the nation through the establishment of official languages rules, public holidays, school curricula, and the use of state symbols, among other markers. Accordingly, election systems and procedures are not neutral either: They define who can vote and who can be elected, how to count the votes and how to establish majorities.Footnote13 Existing election rules in many liberal democracies, such as mechanisms to increase the representation of territorial interests or the particular definitions of election districts, tend to have negative implications for certain groups, including indigenous peoples, Afro-descendants, and women: ‘There are systematic biases inherent in candidate selection procedures and methods of election, that lead to the political marginalization of … [minority] groups’ (Bird Citation2003, 5–6).

Formal equality can thus lead to discrimination in practice – a position sustained by numerous authors often defined as ‘liberal culturalists,’ including Iris Young, Will Kymlicka, Anne Phillips, Melissa Williams, and Jane Mansbridge. Liberal culturalists seek to complement civil and political rights by adopting ‘group-specific rights or policies that recognize and accommodate the distinctive identities and needs of ethnocultural groups’ (Kymlicka Citation2001, 39). In their view, differential treatment can be justified in order to protect minorities from harmful actions resulting from an overpowering nation-building model. But the means and aims of special measures must be carefully evaluated, as ‘the stigma of difference may be recreated both by ignoring and by focusing on it’ (Minow Citation1990, 20).

Reserved (or direct) seats are often conceived of as complementary (temporary or permanent) measures to make the protection of minority rights viable and adaptable in the long term, since they guarantee a certain number of minority representatives in the legislature no matter what the election results. Criteria for the nomination or election of these representatives can involve characteristics such as religion, ethnicity, language, and gender. Kymlicka (Citation1996, 143) describes group representation on the national level as ‘corollary’ and a logical consequence of the delegation of functions and authority to minorities, such as through self-government. The aim is to avoid the possibility of a national government ‘intruding’ on existing minority protection arrangements and to guarantee participation when modifications do occur (Verstichel Citation2009, 66). The number of seats assigned as part of minority protection schemes is usually between one to two percent (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 262–63).

Power-sharing

The question of whether a society is adequately represented by its elected bodies is often difficult to answer, in part because it is difficult to define and to assess ‘representativeness’ (MacKinnon and Feoli Citation2013, 92). Nevertheless, when a major cultural group perceives itself to be suffering from systemic marginalization by the majority political power, national stability can be at risk.Footnote14

Power-sharing aims at stabilizing deeply divided societies in times of escalating conflict and political crisis. As part of a national pact or agreement on the reorganization of the political system, a large proportion of seats in the legislature, between 25 to 70%, is divided between factions or groups defined by ethnicity, religion, or language (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 263).Footnote15

Since 1990, special measures for minorities (both minority protection and power-sharing arrangements) have increased worldwide. Currently, about 40 countries have established state-mandated quotas for minorities in national parliaments (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 257–58). The academic debate, often characterized by a ‘disconnection’ between theory and empirical analysis (Bird Citation2003, 6), seems to be overwhelmed by these legal advancements. These new institutions of direct representation are thus far ‘little understood’ (Bird Citation2014, 12) and few studies focus on the impact of quotas beyond the numbers (Zuber Citation2015, 391). Nevertheless, international organizations and human rights bodies increasingly support contextual special measures: ‘At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the attitude toward reserved communal seats and special mechanisms has swung to a point where they are considered signs of liberal progressiveness’ (Reynolds Citation2005, 303). Accordingly, a broad repertoire of instruments fostering the participation of disadvantaged groups has been developed and systematized, inspired for the most part by the ‘liberal culturalists’ debates. These measures can be divided into three groups (): The first one reinforces the direct participation of minorities in the electoral and legislative process (reserved seats, quotas on party lists). The second establishes instances of self-government for local territorial or non-territorial entities. A third type is based on guarantees, such as constitutional and legal safeguards. Thus, policy makers and civil society organizations can draw on a broad spectrum of options and comparative experiences when designing minority protection mechanisms.

Table 1. Repertoire of measures to strengthen the participation of minorities in public life

Reforms do not, however, follow a universal blueprint, but take place in a particular historical context and evolve over time (Zuber Citation2015, 399). Each country tends to elaborate a specific institutional solution, wherein tactical concerns and the ability to negotiate play a crucial role (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010). This is particularly crucial when it comes to the definition of the number of direct representatives: ‘The number of seats allocated to communal groups generally matches their numerical strength and power to threaten majority interests’ (Reynolds Citation2005, 308). As we will see in the Bolivian case, power relations and political dynamics can also lead to a cherry-picking effect, as politically convenient measures mold the above-described menu of options. There is thus a clash between theoretically desirable objectives such as the coherence and comprehensiveness of minority protection mechanisms and the actual dynamics of political negotiation focused on a single, visible measure.

From a plurinational to a minority model of representation

The dispute about direct representation mechanisms in Bolivia is strongly connected to different conceptions of how to approach a pending state reform, which was broadly discussed at the beginning of the new millennium (Mokrani Chávez and Crespo Citation2011; Salman Citation2009). When President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada was forced by a popular rebellion to resign in October 2003, it became clear that the ‘ancien régime,’ associated with a neoliberal model and political pacts between elites, had lost the necessary credibility and support. A profound institutional reform was needed, but the way toward a new model was deeply uncertain with few institutional solutions in sight. The increase of violent social conflicts suggested a near-future of permanent instability, marked by violent clashes between regions and socio-cultural groups or even the imminent ‘suicide’ and dissolution of Bolivia (Falcoff Citation2004).

Despite the many pessimistic predictions, the rise of Evo Morales and his political movement MAS and the adoption of a new Constitution in 2009 engendered an unprecedented decade of political stability, economic growth based on neo-extractivism (Gudynas Citation2014), and certain advances in terms of social inclusion in Bolivia. Since then, Evo Morales and Álvaro García Linera were elected three times in presidential elections with wide popular support: 2005 (53.7%), 2009 (64.2%), and 2014 (61.4%). They succumbed to their first significant national electoral defeat only recently in 2016, when Evo Morales lost a referendum to pave the way for re-election, with 51.3% voting against re-election. The president managed to override the popular veto by applying to the Supreme Court. Finally, the 2019 national election was surrounded by serious concerns about irregularities and fraud, which led to the president’s resignation (BBC, 13 November 2019). Jeanine Áñez, the second vice president of the Senate, assumed the presidency and committed herself to organizing a new electoral process. There is an ongoing debate on the circumstances of Evo Morales’s resignation and the constitutional character of the current government.Footnote16

Already in the mid-1990s, indigenous organizations had begun to question the role of political parties, which were often oblivious to local needs and interfered in their organizational structures (Gonzales Salas Citation2013, 37). Probably the first proposal for direct indigenous delegates was raised by the Great National Assembly of Indigenous Peoples (GANPI) in 2000. During the fourth March for Popular Sovereignty, Territory, and Natural Resources, led by the Ethnic Peoples of Santa Cruz (CPESC) in 2002 to demand the prompt convening of a constituent assembly, the argument was further developed and the concept of ‘party de-monopolization’ was introduced (Equipo Nizkor Citation2002, 17 May 2002).

Based on these previous elaborations and encouraged by the recent introduction of the figure of the citizen and indigenous associations for the nomination in the electoral processes (Congreso Nacional Citation2004), indigenous organizations began to stand up for direct representation at different moments: first in 2006, before the election of the assembly members, then during the sessions and debates of the Assembly (2006–2007). After the approval of the new Constitution, these organizations tried to influence the transitory laws (2009), and in 2010 they participated in the dispute over the new electoral system, which is still in force (see ).

Table 2. The emergence of direct representation for indigenous peoples in Bolivia

The first hurdle to overcome was therefore the definition of an electoral formula to convene a Constituent Assembly. With the rapid electoral ascent of MAS, the indigenous and peasant organizations saw the opportunity to introduce new visions of representation based on their organizational traditions. At the beginning of 2006 a Joint Commission of the Parliament, charged with facilitating a consensus, had received 24 proposals on how to elect the new members of the Constituent Assembly (Gamboa Citation2009, 52). However, for the first time ideological differences between the indigenous organizations and the governing party regarding direct representation became visible. The executive suggested a novel system of 3 constituents for each of the 70 single-member constituencies. The party that would win by 50% would take all three candidates: ‘Obtaining a majority, in the governmental reading was a condition for the reform, also to avoid it being expropriated by the traditional sectors’ (Rodríguez Ostria Citation2009b, 133).Footnote17

The Unity Pact, an alliance of highland and lowland indigenous organizations,Footnote18 certainly affirmed its political alignment with the government’s proposals at a social summit in Santa Cruz in February 2006 (La Razón, 17 February 2006). Nevertheless, as a condition of this support, it demanded the incorporation of 32 additional indigenous constituents (adding up to a total of 248). In a public statement, the social leaders stressed that at this historic juncture, indigenous peoples should finally be represented as such: ‘The Constituent Assembly … is the mechanism to repair the historical exclusion of more than 500 years, of the indigenous and original nations and peoples. Therefore, it must guarantee their presence and participation’ (Pacto de Unidad Citation2006).

However, these differences between the government and social organizations were minor compared to the increasing political and regional polarization. In order to achieve the approval of the Law of Convocation with two thirds in Congress, the governing party had to achieve the support of at least 21 parliamentarians from the opposition parties. The parliamentary opposition sought to obtain the greatest possible presence of representatives of the ‘Half Moon’ (Media Luna) departmentsFootnote19 in the imminent election and to achieve the formalization of departmental autonomies, which was already beginning to be implemented de facto.

As the deliberations were not progressing, Vice President García Linera opted for informal talks with the main party leaders behind closed doors. The deal he finally obtained was to make the Constituent Assembly elections viable in exchange for the guarantee of a binding referendum on the departmental autonomies. The Special Law of Convocation to the Constituent Assembly, approved in March 2006, was based on the proposal of the executive. Thus ‘the election format was, contrary to what most social sectors expected, totally liberal’; the majority voter system was also reinforced, favoring the opposition (Salazar Lohman Citation2015, 158).

The Bolivian media celebrated the agreement as ‘a historical milestone’ that showed the ability of political leaders ‘to get out of the impasse through consultation and not confrontation’ (El Potosí, March 6, 2006b). The vice president received a special mention for his ‘calm and firm leadership’ (El Deber, March 6, 2006a). For the indigenous organizations it meant that, although they were the driving force of the Constituent Assembly, once again they could not represent themselves without the mediation of third parties.

The second obstacle was to obtain constitutional recognition. After the setback suffered when trying to influence the rules of the game for the convocation, the organizations in the Unity Pact agreed to join efforts to mature an indigenous proposal of their own and to guarantee a close and critical accompaniment of the debates in the Constituent Assembly. As a result of extensive deliberations, the Unity Pact publicly presented its proposal for the new Constitution in Sucre on 6 August 2006, the day of the inauguration of the Constituent Assembly. A more elaborate version, delivered eight months later in full deliberative sessions, introduces three notions of exercising sovereignty that are still in force in Bolivia today: participatory, representative, and community democracy. As far as the formation of the legislature, the members of the Covenant suggested that 70 of 167 (41.9%) representatives be directly elected by each of the nations and original indigenous peoples, peasants, and afro-descendants’ by their own rules (Pacto de Unidad Citation2007, art., 6).

Due to its propositional capacity and its direct interlocution with the MAS leadership, the Unity Pact became one of the most influential actors of the Constituent Assembly, ‘a kind of collective organic intellectual’ (Tapia Citation2013, 131). Of the more than 3000 proposals of the constitutional text sent by different organizations, the proposal of the Unity Pact is considered the one that left most traces in the final text (Garcés Velásquez Citation2010, 14; Zegada, Arce, and Canedo Citation2011, 100). The commission in charge, in fact, incorporated almost literally the formula of a mixed system of election proposed by the Unity Pact and sent as a majority report to the plenary in July 2007 (Comisión Estructura Citation2009).

However, this promising picture for achieving constitutional recognition of direct representation quickly began to darken; in August 2007, MAS withdrew its support for the Structure Commission’s proposal, indicating that the indigenous quota should only apply to minority lowland peoples, not the Quechua and Aymara peoples. This change of position, which was given ‘on direct instructions from President Evo Morales’ (La Razón, 1 August 2007), caused a rift between the government and some indigenous organizations (such as Conamaq, National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu, and CIDOB, Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia) and led to a split between organizations that were part of the Unity Pact. Isaac Avalos, a peasant leader, tried to minimize the impending rupture by explaining that the issue was ‘a bit complicated’ since ‘Quechua and Aymara groups are the majority in the country’ (La Razón, 1 August 2007).

While the Executive sought to speed up the final stretch of the Constituent Assembly, a new controversy over Sucre’s constitutional status as the capital provoked increasingly violent confrontation between different civil society actors and prevented the resumption of debate and a vote on the proposals. Faced with the formal suspension of the Constituent Assembly in ‘a permanent climate of war’ in Sucre (Rodríguez Ostria Citation2009a, 12), in September 2007, a Supra-Party Political Council (Consejo Político Suprapartidario) was formed, responsible for drawing up agreements between the various political sectors to ensure the completion of the constitutional process. In a tense political negotiation process outside the Constituent Assembly, again facilitated by the vice president, the issue of political representation became a matter for negotiation (La Prensa, 29 October 2007).Footnote20 In the final Constitution, the ‘special rural native indigenous districts’ are limited in various aspects: they are not to cross department borders, and can be only established in a rural area for the minority population. The Electoral Commission (Órgano Electoral), not the legislature, is responsible for the definition of the special districts (Congreso Nacional Citation2008, art. 46, VII). The number of reserved seats was left open and the formulation of the article was ‘contradictory’ and incomprehensible, likely because of an editing error at the last minute (Bonifaz et al. Citation2009, 78). The new Constitution was approved by referendum, with 61.4% voting in favor on 25 January 2009.

As the constitutional text on indigenous districts is vague and contradictory, the next hurdle indigenous organizations had to overcome was the transitional election law. The traditional political opposition continued to have a strong parliamentary presence, with more than 55% of seats in the Senate and almost 45% in the Chamber of Deputies.

As the Unity Pact gradually began to lose ground, CIDOB took the lead and formed a technical commission headed by a longstanding indigenous leader and ex-member of the Constituent Assembly, José Bailaba Parapaino. The new proposal was adapted to the Constitution’s minority approach, provided criteria for the definition of special districts, and established 13 seats for lowland indigenous and 5 for highland indigenous communities, equaling 13.8% of the chamber of deputies (Tamburini and Bascopé Sanjinés Citation2010, 12). The advisors of the parliamentary commission in charge of the process (Comisión de Constitución, Justicia y Policía Judicial) committed to incorporating the points raised by the indigenous movement into the executive project.

However, once again the government sacrificed this indigenous demand in a closed-door negotiation with opposition leaders. In February 2009, President Morales tried to calm indigenous leaders in a private meeting and asked them to momentarily renounce their claims in order to ‘make the democratic process viable’ (Tamburini Citation2013, 13).

Law 4021 established seven ‘special rural native indigenous districts’ in the lowlands, to be defined by the National Election Court based on the last census information. Candidates could be nominated by political parties, citizens’ groups, and organizations representing indigenous peoples; representatives would be elected by simple majority (Ley 4021, art. 35). This law made national elections on 6 December 2009, viable and resulted in the re-election of Evo Morales as president of Bolivia, alongside Álvaro García Linera as vice president. A new Plurinational Legislative Assembly was established, which was composed of 36 senators, 70 single-member deputies, 53 multi-member deputies, and 7 indigenous deputies, to replace the old Congress (Tamburini Citation2013, 16). The political setting had changed dramatically, as MAS now headed an absolute majority in the legislature (88 of 130 seats in Chamber of Deputies; 26 of 36 in the Senate).

The last chance for the indigenous organizations to introduce their longstanding demands was the elaboration of the final legislation in 2010. Within 180 days (from January 2010 on) the new Plurinational Legislative Assembly had to approve five laws that would structure the new state, among them a new definitive electoral law. Recalling President Evo Morales’s personal commitment to revise the transitional law once the opposition was defeated, indigenous direct representatives reopened the debate on the electoral law. Their demands included an increase from 7 to 18 special constituencies and compliance with the right to prior consultation (La Patria, 27 June 2010). The government, however, accused the indigenous leaders of participating in an alliance with right-wing groups and of receiving financial aid from USAID (El Diario, 26 June 2010). Despite a hunger strike and a massive protest by indigenous representatives, the election law was finally approved on 30 June 2010, without major changes.

The above-mentioned hurdles, which comprised disputes over a) the election mechanism for the Constituent Assembly, b) constitutional recognition, c) the transitional legislation, and d) the final election law, resulted in limited successes, compared to initial expectations. Many indigenous leaders felt that their interests ‘were literally negotiated between the ruling party and the operators of the opposition,’ leaving a sense of ‘disenchantment’ with a popular government whose president supposedly was a ‘silent ally’ (Patricia Chávez and Emiliano Madrid, author interviews, 2014).

The early proposals tabled by indigenous organizations in relation to political representation, especially the Unity Pact, resemble the above-mentioned ‘power-sharing’ model for representation (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 262–63). From this perspective, as a consequence of the collapse of the political system (1999–2006), the republic should be ‘re-founded’ as a plurinational state. The ‘re-assemblage’ of the state should start from its main components, in particular the indigenous communities, as expressed by an indigenous leader: ‘We want a new Bolivian state. Self-determination based on what? We propose it from our original territories’ (indigenous leader quoted in Valencia García, María del Pilar, and Iván Egido Zurita Citation2010, 33–34). The initial notion of direct representation was therefore based on the idea of creating autonomous territorial spaces or entities for each indigenous nation (at that time, the discussion included 36 peoples) that would elect their respective representatives according to custom and without the intervention of the parties.

The numerous innovations contained in the new 2009 Constitution seemed to increase the expectation of being part of a community-based power-sharing deal. Simultaneously, new state symbols, like the wiphala flag, and official holidays were introduced, and the official name of Bolivia changed. These symbolic acknowledgments suggest a significant alteration of the above-mentioned model of nation-building (Kymlicka Citation2001): the neoliberal and multicultural conception of the state, reflected in the former Constitution (1967, with reforms in 1994 and 2004) was replaced by an intercultural democracy, actively promoted by the state (Salman Citation2011).

Contrary to these expectations, the issue of direct representation was ultimately resolved within the terms subscribed by the notion of minority protection. This ‘minoritization’ – understood as a rather limited vision of indigenous peoples as minorities (Garcés Velásquez Citation2010, 96) – is palpable in the numbers: whereas in the early draft proposals, 42% of the deputies of a new plurinational Assembly were to be elected directly as indigenous representatives (Pacto de Unidad Citation2007, 214), this percentage decreased to 13.8% of deputies during the subsequent bargaining process (Tamburini and Bascopé Sanjinés Citation2010, 12) and was finally set at 5.4%. This effect is even more evident in qualitative terms: in the original proposal, all indigenous peoples were considered (lowland – highland, minority – majority groups) and the election and appointment of representatives was guaranteed through a community’s ‘own authorities, institutions, mechanisms and procedures’ without needing to register as a political organization (Pacto de Unidad Citation2007, art., 24). The final 2010 election law restricted participation to minorities groups in lowlands, set departmental limits, demanded registration as a political organization, and restricted the use of customary law to the appointment of candidates, leaving the election process itself unchanged. As a result, ‘the structure of the state continues being multiculturalist,’ granting indigenous peoples no more than a minority status (Defensoría del Pueblo Citation2016, 120), whereas ‘a strictly plurinational policy would involve the presence of all peoples in the national legislative body’ (Komadina Citation2016, 8). Similarly, Exeni Rodríguez (Citation2014, 216–17) concludes that ‘communitarian democracy has had to pass through the filter, if not the frank supremacy, of representative democracy’ and that, ‘paradoxically,’ most ‘advances depend on the individual vote.’

The party association factor

What aspects determined that the indigenous peoples of the lowlands were ultimately treated as minorities and not as constituent nations of a new plurinational state? Firstly, this effect was the result of a highly polarized social context that favored high-level negotiations and pacts between the main protagonists, sidelining indigenous interests (Chávez Citation2013, 157). In the midst of a state crisis, even basic demands for legality were not observed, and previous agreements simply dismissed, as Carlos Romero, one prominent political negotiator admits (Bonifaz et al. Citation2009, 65). The right to political representation, according to Tamburini and Bascopé Sanjinés (Citation2010, 19), suffered the effects of ‘so-called democratic pacts’ and violated several constitutional principles and rights, inter alia on free, prior, and informed consultation.

Secondly, the alliance of indigenous peoples of the highlands and lowlands within the Unity Pact remained fragile. By Htun and Ossa (Citation2013) inter-sectoral analysis, it seems that the members of the Unity Pact temporarily overcame their internal differences while discussing the general project of state reform. As mentioned, the Unity Pact substantively contributed to the elaboration of a vision of a plurinational state model that combined participative, representative, and communitarian elements (Pacto de Unidad Citation2007, art., 6). Nevertheless, relations between members of this platform were tense; the lowland organization CIDOB left the alliance several times (Zuazo, author interview, 2014). The question of direct political representation was not a suitable entry point to elaborate a common position between indigenous groups. The discussion involved very complex aspects of institutional design and was not an issue with similar relevance for all. Additionally, the capacity of the Unity Pact to negotiate an alliance with the government was gradually diluted after the Constitution was approved (Paulino Guarachi, author interview, 2013). Since then, a process of fragmentation and division between most indigenous organizations has taken place, leading to parallel and weakened organizational structures.

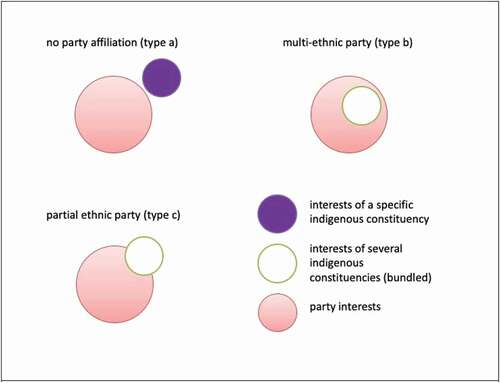

The third and probably most relevant factor explaining the minimization effect relates to the intervention of the governing MAS party in this implementation conflict, a finding supported by recent investigations on the role of political parties as a decisive factor in the effectiveness of special measures for underprivileged groups. According to Zuber (Citation2015, 395) the party affiliation of the minority representative functions as an ‘important moderator of the overall relationship between reserved seats and substantive representation.’ The most effective situation for minority representatives would be no party affiliation (independent candidate) or a ‘coinciding ethnic’ affiliation (Zuber Citation2015, 395). Adapting Zuber’s typology of party affiliation (Citation2015, 394–400) as a visualization tool of different perceptions and expectations (Fisher, Ury, and Patton Citation1983; Maiese Citation2004), it is possible to identify three interest configurations on the issue of reserved seats ().

Figure 1. Correlation between party interests and indigenous interests

When demanding direct election without the interference of political parties as part of a new power-sharing agreement, the indigenous organizations involved were seeking a ‘type a’ relationship of autonomy toward the mainstream MAS party. According to Zuber (Citation2015, 395–97), in this configuration, coincidently, the ‘clearest positive effect’ on substantive representation can be expected, as indigenous representatives act as ‘a one-person ethnic minority party.’ The use of customary law for the election (not only for the nomination of candidates) would give these deputies further legitimacy with their constituencies. It thus seems that the slogan of ‘de-monopolization of parties’ expresses the interest of the indigenous organizations in gaining more room to maneuver on behalf of their minority constituencies.

Since MAS was a platform composed of quite different organizations, initially it did not express a homogeneous position on the special indigenous districts and on the expected legislative behavior of the representatives. In fact, its ideological framework was quite broad, with some internal contradictions, and sufficiently ‘ambiguous’ to serve as a container for a multiplicity of demands. On the one hand, public speeches and programs between 2000 and 2006 contain clear indications of an emerging pluri-national approach. The 2005 government program provides for the ‘representation and participation of indigenous nations in government bodies, such as ministries, in order to give the State a truly multicultural and multinational content’ (MAS-IPSP Citation2005, 3.1.1).

However, since then, MAS made a gradual but drastic change in its position and ended up even opposing direct representation. Under the leadership of the president, a majority opinion was consolidated among peasant organizations and members of MAS that, once the plurinational state had been established, there was no further need for indigenous representation outside of the party’s competence. Majority indigenous candidates should be exposed to the electoral competition under the same rules and conditions as any other candidate, and minority indigenous peoples should run as political organizations or in alliance with like-minded political parties (Schavelzon Citation2012, 528). Thus, according to a predominant conception of MAS, the ruling party was a ‘multi-ethnic’ party, which explicitly included the interests of minority groups (type b).

This change in attitude towards direct representation occurred precisely in a phase of accelerated internal transformation: first, from a political platform of mainly rural social organizations to a party of national scope and then to a hegemonic government party. Being an ‘atypical’ organization (Mayorga Citation2019), a mixture between movement and party (Anria Citation2013, 21), MAS apparently did not become an oligarchic and authoritarian party in this process of institutionalization. The fact that the Government maintained during successive administrations continuous communication links with the different social organizations affiliated to MAS is to some extent surprising, because it contradicts certain principles and ‘laws’ established in political science (Anria Citation2018, 3–4). However, in this rapid organizational transformation there were quite subtle shifts towards greater centralization of power and closure of participation that require further analysis.

The governance model seemed to revolve around the president as the articulating and moderating axis of three ‘rings’ or political spheres quite separated from each other: CONALCAM (National Coordination for Change), ‘a form of unconditional articulation of social organizations with the government’ (Zegada, Arce, and Canedo Citation2011, 268), created in 2007; the cabinet of ministers for strictly public management issues; and the parliamentary bench to coordinate the legislative process: ‘The president is the exclusive actor who decides in consultation with the members who compose these rings either in the execution of policies or in the adoption of strategic decisions’ (Mayorga Citation2019, 170). Thus the plurality of actors with direct access to the government was reduced and political power was concentrated in a ‘palatial binomial’ (Mayorga Citation2019, 171), led by the president and an unconditionally loyal vice president. Additionally, the existing forms of deliberation and consensus building became vertical and authoritarian, leaving very few spaces for discussion and debate of ideas within the government (Luis Tapia and Dunia Mokrani Chávez, author interviews, 2014). Applying this to our case, we certainly detect a systematic pattern of interventions by the president at key moments to reduce the scope of indigenous representation, using different communication strategies, from promises and persuasion to threats.

As an additional limiting aspect, seven elected indigenous deputies were expected to represent 41 indigenous nations or groups. In Beni, for instance, 18 indigenous nations and peoples are represented by one deputy. In this case, the ‘indigenous’ interests to be represented are much more generic than the interests of any one specific constituency. This broad mix of interests made negotiations with the affiliated party even more complex, as the specific interests of each constituency had to be bundled into a more generic and collective interest (illustrated by the white circles in the type b and type c configurations).

Meanwhile, the seven direct indigenous representatives in parliament made serious attempts to push forward the perceived interest of their constituencies by trying to institute a cross-party parliamentary group (brigada indígena). Nevertheless, these attempts were actively boycotted by high powerful representatives of the MAS party. And when it came to elections, the ‘parliamentary roll’ (obligated party-line vote) was applied, as Pedro Nuni, speaker of the indigenous representatives, complained (La Patria, 28 June 2010). On several occasions, the president himself stopped indigenous initiatives; Morales, for example, prohibited the formation of an independent parliamentarian group (El Deber, 2 September 2010). In the last instance, the scope and limits of the parliamentary action of indigenous representatives was defined by the political party MAS ‘to the extent that if they decide to assume different positions, it has to be in terms of quasi rupture with the party, since there is no room for other positions’ (Chávez Citation2013, 163). Tamburini (Citation2015, 27) concludes that MAS punished the indigenous representatives for organizing and forming their own opinion: ‘This rebellious attitude vis-à-vis the MAS was not forgiven by the government, which intensified the pressure on the indigenous people, who were practically dictated a kind of civil death in the Plurinational Legislative Assembly.’

In practice, relationships between direct representatives and party seem thus to fit into the type c model, where only (small) elements of the interest of the indigenous constituencies are contained within the party platform, and where most issues are in conflict or left out. In fact, as a result of the conflict, indigenous leaders from the lowlands claimed in 2010 that their interests were no longer represented by MAS: ‘We see that for the indigenous peoples of the lowlands, the Plurinational state does not exist and the attentions are different’ (Pedro Moye, Consejo Educativo Amazónico Multiétnico, in Cambio, 2 July 2010). Similarly, the vice president maintained his distance from leaders ‘who directly or indirectly are coinciding in their criteria with the extreme right and try to undermine the Constitution’ (El Diario, 26 June 2010).

Party politics had an impact, even beyond the parliamentarian process. Evaluations of the 2009 elections indicate that formal restrictions made nomination as a political organization very difficult for indigenous organizations and led to forced alliances with traditional parties (MOE UE Citation2009). In response, six winning candidates in indigenous districts were affiliated to the governmental party MAS, and the victorious candidate in Pando was nominated by the conservative party Plan Progress for Bolivia – National Convergence (PPB-NC). Similarly, during the 2014 national elections, ‘political forces instrumentalized the forms and practices of community democracy,’ often leaving ‘organic’ (community-based) indigenous leaders out (Vargas Delgado Citation2014, 2). The predominance of the government party and an above-average number of invalid votes characterized the election of direct representatives in both national elections in 2009 and 2014 (OEP Citation2010, 428, Citation2017, 18). The new mechanism installed in 2010 certainly facilitated the presence of indigenous peoples from the lowlands that ‘otherwise would not have counted on a representative in the legislative body’ (Komadina Citation2016, 8). However, the formal limitations established by the election law and the predominance of MAS in the legislature determined the weak profile of indigenous deputies and the low visibility of their interventions. Félix Patzi, ex-minister of education, concludes: ‘Most of the direct representatives have not been able to generate their own opinions and propositions … they have not been able to generate national norms that really benefit the population that they supposedly represent. They participate passively, dependent and totally submissive to the guidelines of the executive branch’ (Patzi Citation2011, 18). Descriptive representation did not transform into substantive representation and failed to strengthen the interests of the indigenous constituencies (Chávez Citation2013; Tamburini Citation2013; Zegada Citation2014; Zegada and Jorge Komadina Citation2014).Footnote21

Conclusion

Contrary to what many analysts would have expected, the political and legal window of opportunity presented in 2006 to ‘re-found’ Bolivia as a plurinational state was not actually used by the new government to reformulate the electoral system from scratch. In effect, the concrete design of communitarian representative elements, as guaranteed by the new Constitution in 2009, was part of a series of implementation conflicts between the government and indigenous organizations of the lowlands, which ended in an exhausting obstacle race for indigenous organizations (Arce Citation2014). The intervention of the ‘palatial binomial’ (Mayorga Citation2019, 171) formed by the president and vice president determined a turn of opinion in MAS and a restrictive interpretation of indigenous participation. The strict application of party discipline reduced the room for maneuver of the seven indigenous representatives in the legislature to a minimum. As a consequence of an insufficient elaboration and weak internal alliances between indigenous organizations, discussions focused mainly on the ‘input’ side of representation (number of reserved seats) at the expense of the desirable output (quality of representation and resulting policies). Thus, compared to the original proposal of most indigenous organizations tabled during the Constituent Assembly (2006–2007), the electoral reform that resulted was limited in scope and ambiguous in intention.

In the period under review, the original idea of a ‘power-sharing’ model that combined collective and individual representation on equal terms, as foreseen by the Constitution, was reduced to a minority approach (Krook and O’Brien Citation2010, 262–63). Even after this solution was accepted, the negotiation on its design and concrete implementation remained tedious and conflictive. Most indigenous organizations aspired to one independent representative for each nation (, type a), whereas the mainstream discourse painted the MAS as a ‘multi-ethnic’ party that already represented all indigenous constituencies (type b). In practice, this resulted in a situation wherein most of the interests of the lowland indigenous were not compatible with party interests (type c). The challenge to build a plurinational electoral system remained unsolved: ‘It is not a Plurinational Assembly if indigenous peoples have to participate through political parties. Representatives will always be subject to party rules or statutes’ (Poweska Citation2013, 274)

This conclusion must be qualified in the case of departmental elections, where indigenous peoples were formally allowed to apply their own rules and procedures in the election of their direct representatives to departmental assemblies (according to Art. 67, IV of Law 4021). In this case, the room to maneuver seems to be broader, although it would require a more in-depth analysis (Tamburini and Bascopé Sanjinés Citation2010, 17; TSE Citation2012; Zegada and Jorge Komadina Citation2014, 85–86).

The Bolivian case provides important lessons on party affiliation as a key factor in the effective representation of indigenous peoples in parliament. The demand for a ‘de-monopolization’ of political parties, put on the public agenda by indigenous organizations in the late 1990s, anticipated the academic debate on the hitherto neglected role of political parties in shaping the scope of direct representation (Zuber Citation2015). The concrete design of electoral mechanisms can have a vital impact on the substantive representation of indigenous peoples. In the case of a minority approach, the number of representatives does not seem to be the decisive factor, even though it was the most dominant and controversial point of debate in Bolivia. Instead, the dissociation of the party apparatus in the electoral and legislative process, as well as the possibility of creating cross-party parliamentary groups, appears to be a much more effective tool for strengthening substantive representation. Thus, direct representation, even when it’s quantitatively low, has the potential to become a powerful instrument for substantive representation if it is embedded in a range of other measures and if it is kept outside of the conventional party logic.

There are a number of other mechanisms available, which were not even discussed in Bolivia, such as qualified majority voting, the veto of certain types of bills, a lower threshold for proposals, and budget allocations (see ). These types of specific measures should be designed in a more comprehensive way taking into account the overall objective of ensuring ‘an effective voice at the central government level’ (HCNM Citation1999).

Since 2009, the government led by Evo Morales began to establish a dominant interpretation of the scope and limits of a plurinational vision, still incipiently contained in the programs of MAS and in the new constitution. In this conflicting path of decantation and clarification, a line was soon drawn between the official, permitted interpretation of plurinationality and another discordant one.Footnote22 Gradually, actors with a broader interpretation were marginalized and lost their privileged access to the center of power. Some of them became subordinate or remained silent. A new form of relationship was established between indigenous organizations and the government, marked by the more vertical exercise of hegemony, the discipline of ‘free thinkers,’ and the exclusion of dissidents. The concept of state-building from below was once again postponed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cletus Gregor Barié

Cletus Gregor Barié is a researcher and practitioner in the field of indigenous rights and social dialogue with a focus on the Andean region. He lived in Bolivia working in development cooperation programs from 2000 to 2009, and completed additional field research in 2013, 2015, and 2016.This article is part of his PhD research at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and the Centre for Latin American Research and Documentation (CEDLA) in Amsterdam on conflicts over plurinational state building in Bolivia and Ecuador.

Notes

1. In Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela, direct representation of indigenous peoples is laid down in the constitution and amounts to 5.4%, 1.1%, and 2.7% of the members of the legislature, respectively. In Mexico, since 2017, all parties must nominate indigenous candidates in 13 of 500 electoral districts for national elections; consequently 2.6% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies are occupied by indigenous people, but with a party affiliation. In Peru there are no direct indigenous representatives in the legislature, but since 2002 there has been a quota system for political parties in regional and municipal elections (Fuentes and Encina Citation2018; Laurent Citation2012). For an overview on indigenous direct representation in Latin America see Fuentes and Encina (Citation2018, 8), Htun (Citation2004, 453, Citation2016, 16), Hoffay and Rivas (Citation2016) and Reynolds (Citation2005, 304–5). The conclusions of comparative analyses are sometimes contradictory, because the availability and quality of data on indigenous inclusions in parliaments at a global level is rather limited and because the election formula applied are highly idiosyncratic (Protsyk Citation2010, 20; Zuber Citation2015, 399).

2. ‘We have left the colonial, republican, neoliberal state in the past. We take on the historic challenge of collectively constructing a Unified Social State of Plurinational Communitarian Law’ (Preamble, all translations are by the author).

3. The founding organizations conscientiously opted for this new form of organization, to break with the logic of conventional parties: ‘MAS is a group of social movements, we don’t want it to be a party, with a leader and statutes’ (Deputy Dionisio Núñez in 2003, quoted in Stefanoni Citation2008, 350).

4. MAS was able to take advantage of the opportunities presented by the decentralization reforms such as the Law of Popular Participation (1994) to broaden its social base, acquire experience in municipal electoral processes under different acronyms, and define new leaderships. Although it did not play a leading role in the different waves of protests since 1999, its markedly anti-system character allowed it to quickly transcend its rural origins and establish new alliances with urban sectors.

5. I understand as implementation conflicts a whole series of debates and disputes between social organizations and the Government over the interpretation of the notions of plurinationality contained in the constitution and how to transform these principles into public policies (Emiliano Madrid, author interview, 2014). These include the question of the protection of the rights of Mother Earth (Law on the Rights of Mother Earth, 2010 and the subsequent Framework Law, 2012), legal pluralism (Law on Jurisdictional Boundaries, 2010), indigenous autonomies (Framework Law on Autonomies and Decentralization, 2010), and the application of prior consultation.

6. Similarly, Canessa (Citation2012, 33) observes both a mainstream discourse that proposed the (re)foundation of a strong state based on an ‘ecumenical indigeneity for a majority’ and a minority perspective seeking ‘respect for cultural difference in its multiple forms and the protection of marginal peoples.’

7. The countries with the highest percentage are Bolivia (41%), Guatemala (41%), Peru (26%), and Mexico (15%) (World Bank Citation2015, 25).

8. Chile, Uruguay, and Guatemala are among the countries with comparatively fewer indigenous representatives, while Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela have recently managed to increase the presence of indigenous peoples in their political institutions.

9. Capotorti (Citation1979, 96) combines objective and subjective aspects, referring both to ‘a group numerically inferior to the rest of the population of a state’ and to the more subjective will of a community to preserve their own characteristics in terms of tradition, religion, or language. He also suggests that only groups holding a non-dominant (economic or political) position fall under minority protection.

10. However, as in the case of ‘minorities,’ there is no broadly accepted definition of ‘indigenous peoples’ and in many countries the concept itself is party to public debate. Most legal documents are based on a definition established by the Ecuadorian Martínez Cobo (Citation1987, 50), Special Rapporteur on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations. In Latin America, the concept of indigenous peoples is often used as a ‘higher order identity category’ (Zuber Citation2015, 397), encompassing various languages, identities, cultures, and situations of subalternality. Bearing in mind the variety and multiplicity of indigenous peoples, Hall and Patrinos (Citation2014, 90) suggest a more flexible way to define indigenous peoples, based on the idea of a polythetic type, where there is a spectrum of characteristics, but each group shares only some of them.

11. Kymlicka (Citation2001, 120) prefers comparing them to other ‘stateless nations’ like the Catalans, the Scots, the Québécois, the Flemish, or Puerto Ricans, with whom they ‘typically share the tendency […] to resist state nation‐building policies, and to fight instead for some form of territorial self‐government.’

12. The independence of the legislator to act freely is often illustrated in reference to Edmund Burke (1729–1797), who argued during a public meeting in 1774: ‘You choose a member, indeed; but when you have chosen him he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of Parliament’ (Burke Citation[1774] 1854, 391).

13. One example of how electoral systems can hinder exact representation is the 2016 presidential election in the United States, where Hillary Clinton received 2.8 million more votes than the legally-elected President Donald Trump by dint of the rules of the Electoral College.

14. As Zhanarstanova and Nechayeva (Citation2016, 78) conclude, ‘underrepresentation of [ethnic] groups in the political life of a country can lead to tragic consequences,’ after revisiting the 2010 political crisis in Kyrgyzstan, caused by ‘weak political representation of non-titular groups.’

15. Illustrative examples of power-sharing arrangements include the Constitution of Belgium (1970–1993), the Taif Agreement in Lebanon (1989), the Dayton Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1995), and the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland (1998). More recently, the participative constituent processes in Ecuador (2007–2008) and Bolivia (2006–2007) also resemble power-sharing agreements, as major stakeholders came to the negotiation table seeking to reorganize the basic principles and structures of the state (Nolte and Schilling-Vacaflor Citation2012).

16. For some analysts, Evo Morales’s resignation was a coup d’état, since the military ‘invited’ him to leave office, while others interpret it as constitutional succession in a crisis situation (Diaz Cuellar Citation2019; El País, 12 November 2019).

17. Both leaders, Evo Morales and García Linera, also expressed their opposition to direct representation of indigenous peoples as a matter of principle, indicating the risk of promoting the division and atomization of indigenous groups. Instead, they supported party quotas, usually a measure applied for strengthening the participation of women (Cordero Carraffa Citation2005, 71; Htun Citation2004; Schavelzon Citation2012, 144).

18. The Unity Pact (Pacto de Unidad) was a national alliance of indigenous and peasant organizations that fought for a profound reform of the Bolivian State through a new constitution. It was formally founded in September 2004 in Santa Cruz with the participation of more than 300 representatives. The Unity Pact represented the culmination of several decades of coordination and articulation between different peasant and indigenous actors. Members included peasant and colonist organizations, indigenous peoples from the lowlands, indigenous peoples from the highlands, and the Landless People’s Movement (Garcés Velásquez Citation2010; Valencia García, María del Pilar, and Iván Egido Zurita Citation2010, 27–28; Zegada, Arce, and Canedo Citation2011).

19. This is an informal political denomination for an area located in the east, formed by the departments of Tarija, Santa Cruz, Beni, and Pando, which together seem to be shaped like a crescent. The opposition to the government of Evo Morales was geographically centered in this region, characterized by strong autonomist movements.

20. In the successive versions of the text – including the Constitution ‘adopted in large measure on the basis of majority reports’, ‘approved in large, detailed and revised’ and ‘text amended in Congress’ (Bonifaz et al. Citation2009, 79, art. 146, 147) the original approach was reduced.

21. As a curious detail, one of the first acts of the transitional government of Jeanine Áñez was the introduction of the direct nomination of indigenous representatives in the special districts, without the intermediation of political organizations (OEP Citation2020). This measure was possibly intended to reduce the influence of MAS.

22. This process is somehow reminiscent of the differentiation between ‘permitted Indian’ and ‘prohibited Indian,’ which applies for the neoliberal regimes of the 1990s (Hale Citation2005), and is taken up again by Postero (Citation2017) through the figure of the ‘allowed decolonized’ under the government of Evo Morales. Here I am interested in the aspect of the enforcement of a rather narrow and centralist vision of plurinationality by the State, rather than the differentiation between ‘accepted’ and ‘unacceptable’ persons.

References

- Anaya, J. 1996. Indigenous Peoples in International Law. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Anria, S. 2013. “Social Movements, Party Organization, and Populism: Insights from the Bolivian MAS.” Latin American Politics and Society 55 (3): 19–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2013.00201.x.

- Anria, S. 2018. When Movements Become Parties: The Bolivian MAS in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arce, C. 2014. “Las organizaciones indígenas y sus relaciones con el gobierno (2010–2014).” In Las naciones indígena originario campesinas en el horizonte plurinacional, edited by M. T. Zegada, 97–106. Cochabamba, Bolivia: Centro Cuarto Intermedio.

- Assies, W., G. van der Haar, and A. J. Hoekema. 1999. El Reto de la diversidad: Pueblos indígenas y reforma del estado en América Latina. Zamora, Mexico: El Colegio de Michoacán.

- Azevedo, C., and P. Basz. 2013. “Indigenous Peoples in Latin America Improve Political Participation, but Women Lag Behind, Says UNDP.” United Nations Development Programme [ News Centre], May 22. Accessed 20 June 2019 https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2013/05/22/pueblos-indigenas-en-america-latina-pese-a-los-avances-en-la-participacion-politica-las-mujeres-son-las-mas-rezagadas-segun-el-pnud.html

- Barié, C. G. 2004. Pueblos indígenas y derechos constitucionales en América Latina: Un panorama. 2nd ed. Quito, Ecuador: Abya-Yala.

- Barié, C. G. 2014. “Nuevas narrativas constitucionales en Bolivia y Ecuador: El buen vivir y los derechos de la naturaleza.” Latinoamérica. Revista de Estudios Latinoamericanos 59: 9–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1665-8574(14)71724-7.

- Barrientos Garrido, M. R. 2010. “De las calles a las urnas: Discurso político y estrategias identitarias del movimiento cocalero y su ‘instrumento político’: MAS-IPSP.” M.A. thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Instituto de Iberoamérica.

- Bird, K. 2003. “The Political Representation of Women and Ethnic Minorities in Established Democracies: A Framework for Comparative Research.” Working Paper presented for the Academy of Migration Studies in Denmark (AMID), Aalborg University, November 11.

- Bird, K. 2014. “Ethnic Quotas and Ethnic Representation Worldwide.” International Political Science Review 35 (1): 12–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512113507798.

- Bonifaz, R., C. Carlos, B. Irahola, and R. P. Undurraga, eds. 2009. Del conflicto al diálogo: Memorias del acuerdo constitucional. La Paz, Bolivia: Fundación Boliviana para la Democracia Multipartidaria(fBDM).

- Burke, E. [1774] 1854. “Speech to the Electors of Bristol.” Chap. 13 In The Founders’ Constitution. 1 vols., document 7, 391. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/print_documents/v1ch13s7.html

- Cabrero Miret, F., ed. 2013. Ciudadanía intercultural: Aportes desde la participación política de los pueblos indígenas en Latinoamérica. Quito, Ecuador: PNUD (United Nations Development Program).

- Calderón, G. F., ed. 2004. Informe Nacional de Desarrollo Humano 2004: Interculturalismo y Globalizacion: La Bolivia posible. La Paz, Bolivia: PNUD (United Nations Development Program).

- Canessa, A. 2012. “Conflict, Claim, and Contradiction in the New Indigenous State of Bolivia.” Working Paper Series. Berlin: desiguALdades.

- Capotorti, F. 1979. Study on the Rights of Persons Belonging to Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities. New York: United Nations.

- Chávez, P. 2013. ¿De la colorida minoría a una gris mayoría? Presencia indígena en el legislativo. La Paz, Bolivia: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Comisión Estructura. 2009. “Informe Organización Y Estructura Del Nuevo Estado.” In Enciclopedia histórica documental del proceso constituyente boliviano, edited by J. C. Pinto Quintanilla, 469–508. Bolivia: Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia.

- Congreso Nacional. 2004. Ley de Agrupaciones Ciudadanas y Pueblos Indígenas. La Paz, Bolivia: Honorable Congreso Nacional.

- Congreso Nacional. 2008. Nueva Constitución Política Del Estado. La Paz, Bolivia: Honorable Congreso Nacional.

- Cordero Carraffa, C. H. 2005. La representación en la Asamblea Constituyente: Estudio del sistema electoral. Cuaderno de análisis e investigación 6. La Paz, Bolivia: Corte Nacional Electoral.

- Defensoría del Pueblo. 2016. Sin los Pueblos Indígenas no hay Estado Plurinacional. La Paz, Bolivia: Defensoría del Pueblos.

- Diaz Cuellar, V. 2019. “Réquiem Para El ‘Proceso De Cambio’.” Control Ciudadano - Boletín de Seguimiento a Políticas Públicas Segunda Época, año XIII, núm. 32, La Paz, Bolivia: Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Laboral y Agrario (CEDLA).

- Díez Astete, A. 2012. Estudio sobre democracia comunitaria y elección por usos y costumbres en las tierras bajas de Bolivia. Elecciones departamentales y municipales 2010. Construyendo la democracia intercultural no. 1. La Paz: Tribunal Supremo Electoral (TSE); Instituto Internacional para la Democracia y la Asistencia Electoral (IDEA Internacional).

- Dovi, S. 2017. “Political Representation.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [ Archive]. Accessed 6 May 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/political-representation/

- Equipo Nizkor. 2002. “Continúa La Marcha De Los Indígenas Que Se Dirige a La Sede De Gobierno.” Derechos Website, May 23. Accessed 27 May 2017. http://www.derechos.org/nizkor/bolivia/doc/indig2.html

- Exeni Rodríguez, J. L. 2014. “Elusive Demodiversity in Bolivia: Between Representation, Participation, and Self-Government.” In New Institutions for Participatory Democracy in Latin America: Voice and Consequence, edited by M. A. Cameron, E. Hershberg, and K. E. Sharpe, 207–229. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Falcoff, M. 2004. “The Last Days of Bolivia?” Nueva Mayoria Website, June 8. Accessed 11 January 2019. http://nuevamayoria.com/EN/ANALISIS/falcoff/040608.html

- Fisher, R., W. Ury, and B. Patton. 1983. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving In. New York: Penguin Books.

- Fuentes, C., and M. S. Encina. 2018. Asientos reservados para pueblos indígenas: Experiencia comparada. Macul, Chile: Centro de Estudios Interculturales e Indígenas.

- Gamboa, F. 2009. Dilemas y conflictos sobre la Constitución en Bolivia: Historia política de la Asamblea Constituyente. La Paz, Bolivia: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

- Garcés Velásquez, F., ed. 2010. El Pacto de Unidad y el proceso de construcción de una propuesta de constitución política del estado: Sistematización de la experiencia. La Paz, Bolivia: Programa NINA.

- García Orellana, A., and F. G. Yapur. 2010. Atlas Electoral de Bolivia: Eleccciones Generales 1979–2009 Asamblea Constituyente 2006. La Paz, Bolivia: Tribunal Supremo Electoral.

- Gonzales Salas, I., ed. 2013. Pueblos indígenas en marcha: Demandas y logros de las nueve marchas. La Paz, Bolivia: IBIS.

- Gudynas, E. 2014. Derechos de la naturaleza y políticas ambientales. La Paz, Bolivia: Plural Editores.

- Gutmann, A., and C. Taylor. 1994. Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.