ABSTRACT

As national demands for security came to override the concerns of border communities more decisively in recent decades, local input in areas such as land use, the environment, and civil rights has been concomitantly diminished. Under the George W. Bush Administration in the U.S. this trend culminated in congressional authorization for and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) execution of legal waivers to push through the construction of new border barriers. Ultimately, DHS voluntarily complied with many components of the waived laws. Still, by exercising Indigenous sovereignty, the Tohono O’odham Nation of southern Arizona pushed back against these waivers to require compliance with laws that had been dismissed. In the Trump era, additional and upgraded border barriers bypassed the Tohono O’odham Nation, but construction took place on nearby traditional territory, illustrating the enduring if tentative role of Indigenous sovereignty in this context. As a cross-border group, the Tohono O’odham are concerned about both the dramatic increase of external policing on their lands and the erosion of contact with tribal members in Mexico, which from an Indigenous perspective is increasingly difficult to traverse and manage.

Introduction

Conflict with central government priorities is a common dynamic between border communities and the countries of which they are a part. Frequently asked to bear the brunt of social and environmental costs for security enjoyed by the entire country, border communities are more likely to be recipients than shapers of policy (Martinez and Hardwick Citation2009). In the U.S. context, border communities are important stakeholders and partners. They are also frequently treated as obstacles to be worked around by representatives of Customs and Border Protection (CBPFootnote1) and other federal authorities whose mandate is to implement federal law (Sundberg Citation2015). Despite recent recognition of the role of border communities and the importance of local involvement as recognized by a social ecology of borders (Grichting and Zebich-Knos Citation2017), local communities are often sidelined rather than made central to border security. In balancing national perceptions of need against the immediacy of daily life for a much smaller sub-set of the country, it is the latter that is generally expected to yield. The perception of a ‘greater national good’ outweighs the interest of local communities and individuals in such cases.

While direct financial costs may be covered nationally, local communities also experience indirect social costs. In order that others may feel more secure, border residents are more heavily policed, endure more extensive surveillance, and find their movements more restricted and monitored (ACLU Citationn.d.; Amnesty International Citation2012). Residents’ motives are questioned when they visit friends and family, backup proof is best offered if stopped after a return from the grocery store late at night, and deference is essential to avoid an escalating incident. Civil rights and freedoms are often infringed upon, an experience most others in the country do not face.Footnote2 Furthermore, some border residents are more likely to be suspected and detained, while others are more likely to be trusted and allowed freer reign. It was not always and consistently the case, but as a white person with university credentials (if they even needed to be shared), I generally was not questioned too intensely while doing fieldwork in the area. In the borderlands – where a significant part of the local population is visually recognizable as Hispanic/Latinx or Indigenous – such individuals are more likely to be questioned.Footnote3

There are also other costs to border security, particularly when considering the construction of border barriers.Footnote4 Such construction activities in remote areas often have an extensive environmental footprint. Under normal circumstances, all parts of the country would be afforded equal protection to limit or mitigate the negative impacts of such activity. However, with the waiver of laws those protections are noticeably absent in the case of barrier and related infrastructure construction.

This article investigates how DHS waiver authority impacts Indigenous nations with a degree of sovereign authority along the U.S.-Mexico border. The spotlight is on the Tohono O’odham of southern Arizona and northern Sonora.Footnote5 In the next section, I introduce the geographic and political setting of the Tohono O’odham and how that intersects with the context of U.S. border security. I then discuss the origins and relevance of DHS waiver authority to border barrier construction and Indigenous people before examining the case of the Tohono O’odham in more detail. The Tohono O’odham situation counters the narrative that a waiver of laws is necessary to facilitate border barrier construction. My focus is on the legal implications of laws waived from 2005–2021, an alternative form of compliance (now voluntary), and the response by the Tohono O’odham tribal government vis-à-vis tribal sovereignty. A more general discussion ensues about the use of the waivers in practice and other border security initiatives, such as monitoring towers that do not qualify for waiver authority. This discussion sheds light on the greater political environment in which these issues take place and on implications for the future. The paper concludes with a consideration of dynamics during the Trump administration, conflict and collaboration between the Tohono O’odham and the U.S. federal government over border security, and what that could mean for other border communities.

This project builds on over twenty years of working with the Tohono O’odham Nation on tribally-approved research projects. My experience on the Tohono O’odham Nation (‘the Nation’) includes almost five years of cumulative employment on the reservation at Tohono O’odham Community College between 2004 and 2017—including nine months on a tribal research project about education, a year working with distance education programs, two years as a full-time faculty member, and a year an adjunct instructor while on sabbatical from my current home institution. Since 2017, I have also been a core member of Indivisible Tohono, a group that promotes civic engagement among tribal members. Opposition to barrier border construction was one of the key issues motivating the formation of this group prior to my participation therein and continues to be an area of the group’s interest. My ongoing research on border walls has been approved by the tribe (TOLC Citation2017b) and is currently supervised by the Tohono O’odham Nation Institutional Review Board (IRB) and The Ohio State University’s Behavioral and Social Sciences IRB (study number 2009B0386). While formal interviews are possible under those research protocols, most of the background context for this paper was collected through publicly available documents and observation/interaction in public contexts. Informal conversations and requests for feedback on my ideas and writing from acquaintances and friends honed my understanding of these topics.

The Tohono O’odham context

Living in the Sonoran Desert since before European Contact, in recent centuries Tohono O’odham territory was controlled by Spain and later Mexico. During this time the group was known to others as the Papago. A large portion of their homeland was transferred to the United States with the Gadsden Purchase in 1854, which created the current split of the tribe’s traditional territory between two countries. Today the Tohono O’odham remain divided, with the Tohono O’odham Nation having a land base of several million acres (over a million hectares) in Arizona. The U.S.-based tribal government is federally recognized and sub-divided into eleven local governance units known as districts. Each district is comprised of multiple villages or communities. The community of Sells serves as the capital of the Nation. Pre-Contact, the Tohono O’odham extended well into what is now Mexico (Erickson Citation1994, 17), yet today only a handful of rural communities in that country identify as predominantly Tohono O’odham. As in the U.S., there are several urban concentrations of Tohono O’odham. On both sides of the border, Tohono O’odham have some degree of autonomy in their governance but it is on the U.S. side that tribal sovereignty is most formalized as a recognition of inherent tribal rights and self-determination.

While the division of the tribe’s fate into two countries initially had few consequences, internalization of its progressive division between the U.S. and Mexico is well-documented (Madsen Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015; Mott Citation2016; Nabhan Citation1982, 67–74; Naranjo Citation2011; Spears Citation2005; Weir and Azary Citation2001). Even so, much of the literature also recognizes that the tribe’s identity continues to have a strong cross-border component and there have been periodic efforts to push back on cross-border restrictions (in addition to the above, see Barnett Citation1989; Castillo and Cowan Citation2001; Papago Council Citation1979a, Citation1979b). Shared sacred sites and ceremonies endure on both sides of today’s international border.

There remains substantial resentment and resistance among the O’odham to the idea that they should face increasing restrictions on crossing given their deep ties to and continuous presence in the Sonoran Desert. Mobility is traditionally important to Tohono O’odham residential patterns, economic activity, and cultural ceremonies. Traditional seasonal migration is largely a thing of the past, but mobility as practiced today remains incongruous with contemporary norms of international borders (Gentry et al. Citation2019; Hoover Citation1935; Jones Citation1969; Schermerhorn Citation2019).

Despite global mobility for corporations, capital, and select sets of people through official ports of entry, cross-border unity among the O’odham faces a difficult challenge in an era increasingly dominated by nation-states and the corresponding fortification of borders. Today, arguments favoring cross-border O’odham interests are outweighed by trade priorities and security concerns which have come to dominate the border policy agenda. Meanwhile, northbound flows of migrants through the border region have shifted since the 1990s out of urban areas and through more rural places like the Tohono O’odham Nation due to deterrence-based strategies that incorrectly assumed migrants would give up as crossings were forced into more dangerous desert areas (Boyce Citation2019; Cornelius and Salehyan Citation2007; Madsen Citation2007). Security sensitivities after 9/11 and the ongoing war on drugs have further complicated cross-border unity among the O’odham (Luna-Firebaugh Citation2005; Singleton Citation2008).

In the remainder of this paper, I examine one particular way in which the Tohono O’odham Nation’s contemporary tribal government has responded to transborder challenges. The ability of the tribal government to impact border policy comes from its capacity as a federally-recognized and regulated entity with a degree of sovereign authority to make decisions on the land under its control. Such sovereignty is by no means absolute and certainly pales compared to that enjoyed by nation-states. However, it does provide a basis by which this particular border community can exert some influence on securitization processes otherwise almost entirely dominated by a national agenda. Of course, resistance happens at multiple scales, including outside the purview of formal government structures. Sovereignty at the tribal level does not reflect the full diversity of Tohono O’odham perspectives or actions on the issue of border, nor should it be expected to do so (Madsen Citation2015). While many support tribal actions, other individuals and groups have taken up positions critical of the tribal government.Footnote6

Given that there is internal discussion and debate among tribal members about the appropriate role of federal law enforcement on tribal land, tribal government finds itself in the complicated position of criticizing CBP and the federal government for their social and environmental impacts while also broadly supporting efforts to secure the area against illicit cross-border traffic to minimize the impact such flows have on the tribe. In this latter respect, however, the Nation has come down firmly on the need to be culturally and environmentally sensitive to local concerns. This translates into a very hands-on approach to overseeing CBP activity on tribal land.

DHS waiver authority

To assure minimal interference with the extensive and rapid construction of border barriers as provided for by Congress, a provision was included in the REAL ID Act of 2005 giving the Secretary of Homeland Security the ability to waive laws in areas of planned fence construction (see U.S. Congress Citation2005). This authority is also sometimes referred to as Section 102(c) waiver authority after the section of 8 U.S. Code § 1103 in which it is codified (Cornell Law School Citationn.d.).

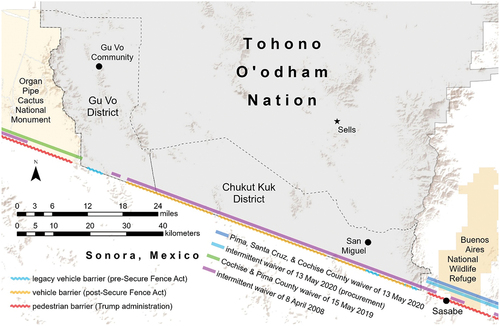

To date, 84 federal statutes and regulations – as well as numerous federal, state, and other laws derived from or related to them – have been waived by the U.S. government, suspending normal legal protections along the border. Among the laws waived are the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which takes alternative approaches under consideration and ensures transparency through consultation with local communities and other stakeholders (Eccleston and Doub Citation2012). Other statutes provide oversight for clean water (the Clean Water Protection Act), waste disposal (the Solid Waste Disposal Act), archaeological sites (the Archaeological Resources Protection Act), and birds (the Migratory Bird Treaty and the Migratory Bird Conservation Acts). Of particular interest to Indigenous people, the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) has been waived in 27 out of 32, waiver determinations to date, as was the Eagle Protection Act. Elsewhere, I have published a more detailed history of the spatial extent of DHS waiver authority (Madsen Citation2022). It is worth noting here, however, that the use of waivers has unique implications for the distinctive status of Native land and tribal sovereignty in the United States in that the Tohono O’odham do not want to abandon the protections offered by these waived laws. While the Tohono O’odham Nation represents the most prominent Indigenous presence along the U.S.-Mexico border, other tribes are also impacted (Connolly Citation2020). A listing of waiver determinations covering tribal lands along the U.S.-Mexico border is provided in , while illustrates their spatial extent and the placement of various barrier styles on and near the Tohono O’odham reservation.

Figure 1. The Tohono O’odham Nation and the U.S.-Mexico border, 2022. Map by the author. Data sources: ESRI, USGS, NOAA, NPS, FWS, U.S. Census. Barrier locations based on Baker (Citation2013) and Traphagen (Citation2021). For full view of traditional territory and the current reservation boundaries (see Erickson Citation1994, 17; and; Madsen Citation2014a, 54). See color version online.

Table 1. Intersection of native lands with DHS waiver authority.

In addition to waiving legal compliance with laws specified in the determinations, by utilizing waivers DHS avoids having to defend itself against legal challenges. For example, neither the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA, waived 26 times) nor the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA, waived four times) offer robust protection as the courts have already struck down substantial portions of their texts.Footnote7 As a result, these two laws hardly seem to have been a priority. Nonetheless, RFRA was successfully used in the defense of Tohono O’odham tribal member Amber Ortega who obstructed border wall construction at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in September 2020 (Ingram Citation2022). This usage was possible because RFRA was not waived for this particular construction project, and as a result, the Ortega lawsuit tied up DHS resources in court.Footnote8 The rationale for waiving a particular statute is not always obvious, but waiving pre-emptively sidesteps legal challenges and thereby clears the way for fast-tracking border barrier construction – an essential goal of DHS waiver authority.

While Section 102(c) of 8 U.S. Code § 1103 provides for DHS waiver authority, starting in December 2007 (Madsen Citation2022), Section 102(b) also puts some expectations on the DHS Secretary as the agency proceeds with the construction of border barriers:

In carrying out this section, the Secretary of Homeland Security shall consult with the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Agriculture, States, local governments, Indian tribes, and property owners in the United States to minimize the impact on the environment, culture, commerce, and quality of life for the communities and residents located near the sites at which such fencing is to be constructed. (Cornell Law School, Citationn.d., italics added)

While the format of such consultation is not spelled out, and judicial recourse is limited (Madsen Citation2022, 19), this wording sets an expectation for interaction with tribes. Even so, well before the incorporation of this wording, CBP was working closely with the Tohono O’odham Nation to construct border barriers on and near reservation land.

Border barriers on the Tohono O’odham Nation

Political events in the 1910s led to construction of the first fence along the southern edge of what is today the Tohono O’odham Nation (Erickson Citation1994). Tensions due to the Mexican civil war meant that Papagos sometimes could not cross the border freely to retrieve wandering cattle. Theft of cattle north of the boundary by Mexican soldiers and bandits was also reported. Later, there was concern about the illicit smuggling of arms in support of the Yaqui, an Indigenous group in southern Sonora. Ultimately the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs agreed to provide material to construct a barbed wire cattle fence along the border and Papagos provided the labor to build it.

Throughout the 1900s, other border fences – limited in extent, temporary during the Mexican civil war, often oriented towards cattle and preventing the spread of livestock diseases rather than people and traffickers – were proposed and established along the Arizona-Sonora border. By mid-century, some 206.5 miles of seven-strand barbed wire fencing had been built in rural areas west of El Paso, Texas with an additional 13.5 miles of chain link construction in urban areas near ports of entry (Bell Citation1985, 3). In the 1970s and early 1980s, a heavy mesh material was used in many urban stretches. It was not until the early 1990s that solid walls began to appear in California. As such projects expanded to the edges of urban areas and other high-traffic crossing areas, the cumulative impact of border barrier construction and accompanying enforcement actions was to increasingly funnel migration and illicit cross-border traffic to more rural areas, such as the Tohono O’odham Nation (Madsen Citation2007; Soto Citation2018; Sundberg Citation2008).

The funnel effect created a need for border barriers on the Tohono O’odham Nation from the perspective of the Border Patrol as a logical extension of their enforcement activities. It also triggered the formation of a receptive audience among the Tohono O’odham themselves. Nevertheless, there was general Tohono O’odham resistance against the influx of Border Patrol agents, the erection of barriers across the open Sonoran Desert, and the accompanying waiver of laws that protected their land base.

Over a year before passage of the REAL ID Act of 2005 and two and a half years before passage of the Secure Fence Act in Oct. 2006, the Tucson Sector of the Border Patrol secured unanimous passage of a resolution by the Tohono O’odham Legislative Council (TOLC) supporting the construction of vehicle barriers (TOLC Citation2004). In keeping with Tohono O’odham political practices, the Border Patrol had obtained supporting resolutions the previous year from the two districts of the Tohono O’odham Nation that run parallel with the international border. DHS waiver authority was not yet in place, but a predecessor law had already raised the specter of waiving NEPA and the Endangered Species Act (U.S. Congress Citation1996, 555). As a result, the resolution specifically stated as a condition ‘that the USBP [U.S. Border Patrol] will perform cultural resource clearance and fully comply with the National Environmental Policy Act’ (TOLC Citation2004, 2). Additional constraints specified that construction was primarily limited to the federal 60-foot (18.3 m) Roosevelt Easement aligning the border (see Roosevelt Citation1907), future approvals were required for additional rights-of-way, CBP would maintain the barriers and related roads (which would be open for tribal use), and the Nation reserved the right to approve border barrier and road design. There was also an expectation that tribal members would be given preferential hiring on the project when possible.

By contrast to pedestrian barriers being built in and near urban areas, vehicle barriers disrupt traffic by stopping vehicles rather than people. Several designs used on the Tohono O’odham Nation and elsewhere are shown in . The idea with such barriers was that crossers without vehicular support can cover less distance, and smaller quantities of drugs could pass through the area. Forced to walk to a pick-up point, migrants and people carrying drugs would be more easily intercepted by authorities. The more solid and wall-like appearance of pedestrian barriers found in urban areas by this time were out-of-place and unnecessary in the open desert and opposed at any rate by the Tohono O’odham. Migrants in rural areas did not have the cover of urban life, and anyone who crossed a vehicle barrier on foot would stand out to even the most casual observer. The danger of inexperienced pedestrians walking long distances through harsh terrain was to be a deterrent, although one that unfortunately often ended in death rather than pre-emption of crossings (Boyce Citation2019; Cornelius and Salehyan Citation2007; Madsen Citation2007; Simpson and Correa Citation2020; Soto Citation2018; Sundberg Citation2008).

Figure 2. Bollard-style fencing southeast of San Miguel. Note supplementary cable and barbed wire. Feb. 2010. (Photograph by author). See color version online.

Figure 3. Normandy fencing on the left, frequently used in areas of steeper incline and across dry washes, and corral (rail-on-rail) fencing on the right. View from La Lesna Mountains west toward Papago Farms. Non-linear barrier placement reflects the sidestepping of tribally identified cultural sites and environmentally significant areas. March 2018. (Photograph by author). See color version online.

Further approval for vehicle barriers was confirmed with another resolution in July 2006 with the provision that openings be maintained in three traditional crossing locations in Chukut Kuk District (TOLC Citation2006b). None were to be left open within Gu Vo District in the far western part of the Nation, although ultimately, other gaps were left in remote and otherwise difficult-to-cross terrain in that area. Another resolution the previous month authorized the use of National Guard troops for border vehicle barrier installation and other non-patrol, non-law enforcement duties (TOLC Citation2006a).

As the ramp-up to barrier construction proceeded on the Nation, the tribal government approved a Historical Properties Treatment Plan in compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1996 to mitigate the impact on ten properties eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (TOLC Citation2007a). Fourteen months later, this type of consultation, which was expected under tribal sovereignty and further enshrined in various national laws, came under threat. In early April 2008, two waivers covering 581.3 miles (935.5 km) of border were proclaimed. Most of the reservation’s 61.6 miles (99.2 km) along the U.S.-Mexico border was included – all but 2.6 miles (4.3 km) on the western edge of the reservation where legacy vehicle barriersFootnote9 already existed and an additional 3.9 miles (6.3 km) where the terrain was rough enough it was not deemed necessary to be fenced.Footnote10

Two months prior to the issuance of the April 2008 waiver determinations that covered most of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s international boundary, the tribe had passed a general resolution urging the repeal of DHS waiver authority and the Secure Fence Act and encouraging greater consultation with tribes (TOLC Citation2008a). The Tohono O’odham Nation had already worked with the Border Patrol for years on this topic. They saw value in reducing illicit crossings across the reservation and were committed to allowing the construction of vehicle barriers along the international border. Nevertheless, members were also concerned about negative interactions with the growing Border Patrol presence in terms of harassment, increasing feelings of invasion, and privacy concerns (e.g. Amnesty International Citation2012; Rozemberg Citation2001; Runner Citation2004, Citation2014; Smith Citation2006). Waivers on O’odham land increased the challenge of balancing support for and criticism of CBP.

A December 2008 TOLC resolution specifically noted that the tribe’s original 2004 approval was premised on full compliance with NEPA and highlighted the loss of protection due to the waiver. The tribe moved forward and re-affirmed its support for what they had already agreed to in terms of vehicle barriers, but at the same time it also took a firm stand against the waivers (TOLC Citation2008b). Continued support was subject to consultation and coordination with the tribe and compliance with all waived laws. Somewhat out of character for the resolution, another condition was to avoid interruption of cultural events and “respect the Nation’s members’ human and civil rights and respond in a timely manner to concerns regarding these issues” (TOLC Citation2008b, 2). Although not directly tied to the waiver of laws, this was indicative of the need to balance such support for border barriers with the concerns of tribal members (see also TOLC Citation2017a).

Voluntary compliance and tribal sovereignty

Despite the waiver of legal protections along the Tohono O’odham Nation’s stretch of the international border, two dynamics moderated the situation: voluntary compliance and tribal sovereignty. With voluntary compliance, DHS softened the impact of waivers by choosing to follow aspects of many waived laws even though they were under no obligation to do so and did not have any external oversight or enforcement as part of that process. Tribal sovereignty complicated this approach, however, by adding a new layer of oversight, that of the Tohono O’odham Nation, which was hesitant to grant DHS release from such formal obligations and procedures.

Voluntary compliance

The phrase ‘voluntary compliance’ is not used publicly by DHS or CBP, but is a phrase encountered among activists opposed to additional border barrier construction. I adopt it here because the language aptly describes in neutral terms how DHS approached the waived laws. In this scenario, DHS argues that it is a responsible actor largely complying with waived laws despite its use of waivers to protect the agency from administrative minutiae and distracting lawsuits.

Central among the laws waived is the flagship law set aside in all but two of the waiver determinations, NEPA.Footnote11 As an alternative to required Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Environmental Impact Statements (EISs) under NEPA, DHS created a parallel review process. Under this approach, CBP developed Environmental Stewardship Plans (ESPs) and Environmental Stewardship Summary Reports (ESSRs) as their own version of environmental review to allay the concerns of border communities and environmental groups (CBP Citation2019, Citation2020).Footnote12 Although often associated with the transition to the Obama Presidency in 2009, the utilization of ESPs began under the previous Bush Administration, with one of the earliest being issued in May 2008 for projects around Yuma just a month after the waiver of laws for border barrier construction in that area. In that document, DHS emphasized their approach: ‘Although the Secretary’s waiver means that CBP no longer has any specific legal obligations under these laws, the Secretary committed the Department to responsible environmental stewardship of our valuable natural and cultural resources’ (DHS Citation2008a, ES-1).

There is substantial flexibility in the structure of an EA under NEPA and how a government agency might receive public input, but there are some general expectations (Eccleston and Doub Citation2012). The content of an ESP roughly parallels much of what might go in an EA. Rather than external norms and expectations, however, CBP itself determines what gets documented and what public input on the process should be. ESSRs detail a project’s final impact, including post-ESP changes, actual vs. expected impacts, and reports from environmental monitors during the process (CBP Citation2020). No new waivers were declared during the Obama Administration, but border barriers continued to be built as mandated by the Secure Fence Act of 2006 utilizing the previous Bush-era waivers. ESPs continued to be used during this time for previously planned projects, although NEPA-regulated EAs were carried out for new construction plans (e.g. DHS Citation2012).

Tribal sovereignty

Parallel with the expanding role of national security, tribal governments in the U.S. are aspiring to fulfill the ideals of Native American sovereignty by carving out and sustaining a more significant role for tribes within the U.S. political system. Similar to how CBP has been given increasing latitude in recent decades, the trend is toward incorporating a more significant role for Indigenous community governance. This is the case both in the U.S. and elsewhere, and corresponds to a broader global trend (Nicol Citation2010; Weissner Citation2008).

Indigenous sovereignty in the U.S. political context is a highly contested issue that must be contextualized. While the vocabulary is reminiscent of the Westphalian sovereignty of nation-states, in the U.S. domestic political context the self-governance rights (‘sovereignty’) of Indigenous peoples is quite different even if it often aspires to full equality in this regard. Indigenous sovereignty is hinted at in the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which lists ‘Indian Tribes’ alongside with, but separate from, ‘foreign Nations.’ Such sovereignty was formalized in treaties between the federal government and various tribes prior to 1871, but subsequent to that time alternatively constrained and reinforced by shifting Congressional interpretations. As a dynamic concept, tribal sovereignty generally encompasses U.S. federal and state interactions with tribal governments. However, in recent years the concept has also served as source material for a broader understanding of self-determination, self-sufficiency, and autonomy by individual tribal members and wider Indigenous political/cultural movements.

Formal U.S. tribal sovereignty is limited by the legal history of European settler-colonialism (Williams Citation1991) even as it became a global model for colonial-Indigenous relationships (Mamdani Citation2020). Today, it is what Lenzerini (Citation2006) calls a ‘parallel sovereignty,’ which grants a degree of internal autonomy, although one that varies and is frequently in flux. Framed as ‘domestic dependent nations’ by the Supreme Court in 1831, a common understanding today by many Indigenous peoples and in the Tohono O’odham political context is that of a ‘government-to-government’ relationship. This term refers to a more equitable and direct relationship with the U.S. federal government that largely bypasses the states but also implies a standing somewhat independent of the U.S. political framework. The specifics of this relationship are limited in practice by the persistence of U.S. assimilation and widespread assumptions about political structures that give scant credence to tribes even as recent decades have seen a promotion of self-government (Silvern Citation1999). Few would argue that it is equivalent to complete independence, although some, such as the Akwesasne Mohawk, are recognized as pushing the limits of this concept more than others (Simpson Citation2014).

Mamdani (Citation2020) argues that Indigenous sovereignty, as practiced in the U.S., is not simply an anemic version of jurisdiction. It is instead an ongoing colonial strategy of domination. Mamdani further argues that although many Indigenous people have bought into the idea that their rights are best protected in this system, it is actually geared more toward protecting settler descendants.

As insightful as Mamdani’s critique of Indigenous sovereignty is, it is also the case that many Indigenous people themselves are aware of the limitations inherent in this system (see Tohono O’odham perspectives referenced in Hennessy-Fiske Citation2019; Leza Citation2019, 68) and continue to push to widen the scope of Indigenous sovereignty as it has been handed to them. Mamdani understandably asserts that many academic works, such as the present article, are overly optimistic in celebrating the resolve of Indigenous people against colonialism as if it were a past condition to be overcome rather than an ongoing oppression. Native culture in these cases sometimes comes across as a static entity with limited power to make incremental improvements to the status quo. In Mamdani’s view, this unique relationship is less empowered by the government-to-government relationship than constrained by it given that Congress and not the Constitution is the ultimate arbiter of Native American political and civil rights (Mamdani Citation2020, 38).

This tenuous status of Native Americans highlights the political balancing act the Tohono O’odham undertake in defending their interests, whether understood as an act of Indigenous sovereignty or simply a political maneuver to be heard. Either way, the tribe operates in a highly charged and fragile political environment that is not built to accommodate their interests. In terms of sovereignty, the critical issue in this paper is not just how the Tohono O’odham have made the best of a difficult situation – but how they have actively used what is generally a tool of oppression and made it work for them in a new way. In this case, Indigenous sovereignty – as limited and colonial-in-origin as the concept may be – serves a purpose unavailable to any other level of government, state or local.

In this sense, the Tohono O’odham Nation is using sovereignty not just as a means of grabbing the attention of authorities or translating Tohono O’odham concerns for a non-Native audience but as a means of dispossessing U.S. claims from traditional O’odham lands (after Rifkin Citation2009, 113). By emphasizing their deep connection to the land, which pre-date the borders of contemporary U.S. and Mexican settler-states, the Tohono O’odham undermine external demands for border barriers and legitimize their own position. To be sure, it is an uphill battle, but one made possible by the unique role tribal governments play in the U.S. political system.

On top of these more expressly political and federally-recognized levels of sovereignty, increasing consideration is also given in Indian country to the importance of other types of independence couched in this framework, such as financial, cultural, and educational sovereignty. For Gentry et al. (Citation2019), autonomy is a fundamental expression of Indigeneity beyond the legal definition, creating and re-establishing a place for the Tohono O’odham in Mexico on their terms and as defined by their own cultural traditions. This aspect of sovereignty is understood by tribal leadership and members in both countries as having a seat at the table when decisions are made. At all levels for the Tohono O’odham, being a part of discussions that impact their lives is key to how sovereignty is advanced and lived. One Tohono O’odham tribal member quoted in the press referred to sovereignty as holding the Border Patrol accountable for its impact and behavior on tribal land (Hennessy-Fiske Citation2019). At its most basic level, sovereignty is here understood as exerting political agency – being present and acting for oneself versus being acted upon – something applicable both to the tribe and to individual members (see Leza Citation2019, 75). Unlike its broader definition and popular understanding in other contexts, ‘sovereignty’ has become a catch-all term in Indian country reflecting a sense of collective political power and control over their own lives.

In the U.S., an essential element of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s sovereign authority is to protect tribal land from encroachment by others. The focus is mainly on areas currently controlled by those identifying as Tohono O’odham (i.e. reservation and trust lands). Nonetheless, there remains an interest in what happens more broadly on historic or traditional lands of the Tohono O’odham and the tribe frequently advocates for such areas and provides input on government actions affecting such areas.Footnote13 In the U.S., NAGPRA even mandates the repatriation of remains and cultural objects from off-reservation locations. While these approaches reinforced conceptions of sovereignty in recent years, today they are also challenged by DHS waiver authority.

The Tohono O’odham reservation was established as an executive order tribe rather than through a treaty ratified by Congress but today U.S. tribes are generally administered similarly regardless of how they came to be recognized by the federal government. Even when the federal government-tribal relationship is modeled after a treaty, it is worth remembering that such status has historically been weak and tenuous. Nonetheless, Native Americans are today less constrained by past shortcomings and diligently seek to fulfill the ideals of sovereignty long promised to them. In the Tohono O’odham case, the 1916 executive order by President Wilson was not set in stone but was rescinded, adjusted, re-issued, and eventually added onto by various acts of Congress (Erickson Citation1994, 104–109, 140–142). Despite these and other subsequent Congressional actions as a form of legislative confirmation (Levy Citation2017, 4), the contemporary tribal government’s status as an executive order tribe became the cause of some anxiety in the Trump era. Some tribal members were concerned that opposition to border barriers might result in a reduction in trust land or even tribal termination (the withdrawal of federal recognition) to make way for new border barrier construction.

It is also worth noting that some have expressed concern the tribal government is hesitant to be too vocal in their opposition to border barriers given a degree of fiscal dependence on federal funding. To some degree this critique acknowledges that federal recognition essentially defines the tribal government as an extension of the settler state (anonymous reviewers of this manuscript; see also Leza Citation2019, 69–70, 74; Mamdani Citation2020). Both of these are legitimate points to raise, but they also overlook justifiable tribal concerns over safety and security that incentivize cooperation with the DHS. The tribe sees CBP as being able to assist with smuggling networks entangling the reservation and with the diversion of tribal police resources from the local community even as the tribe also seeks to manage the negative aspects of their presence (see Madsen Citation2015). The decision of the tribe to work with DHS rather than take a more confrontational approach is an unremarkable choice made by the tribal government to work within the system. Furthermore, while these issues might indeed temper some tribal reactions, allegations of a wholesale sellout on this basis are largely unsupported speculation. In the end, concerns about retribution in terms of funding or federal recognition did not turn out to be justified, and this dynamic has not pre-empted direct and pointed tribal criticism of the U.S. federal government (U.S. House of Representatives Citation2008, Citation2020).

Discussion

With the waiving of laws on and alongside land reserved for Indigenous use, the trend of greater authority for two political agencies comes into direct conflict. The CBP is used to having the upper hand in carrying out national security priorities. The Tohono O’odham Nation is used to increasingly make its own decisions about land and people under its control. Perhaps as with many political relationships, how far each agenda could be pushed is an open question on both sides. Tribes are unsure how far the federal government might push DHS waiver authority to get what they want on tribal lands. At the same time, DHS is unsure as well. Even though waiver authority has been upheld in courts so far, political winds do change. As a result, both entities have proceeded to negotiate carefully while respecting each other’s positions. Neither wants to come across as too pushy in the public eye, especially the DHS. Negotiating and working with local communities at some level is good for their image and, like voluntary compliance, helps undercut arguments that waiver authority should be invalidated. Contributing to the tribe’s willingness to work with CBP was that the Tohono O’odham also wanted to find a solution to the issue of national security as their homeland was being dramatically impacted.

Considering these factors and acknowledging that CBP did prepare a final EA for the project in 2006 (DHS Citation2006), the TOLC rejected CBP’s subsequent ESP as ‘not grounded in any federal law or regulation’ and furthermore was not a ‘legally sufficient document from which to base decisions regarding construction’ (DHS Citation2008b; TOLC Citation2008b). DHS subsequently relented and carried out a NEPA-regulated supplemental EA (DHS Citation2009). With an EA, the Tohono O’odham had a document that historically provided legal recourse even if it was not clear an EA would have legal viability in federal courts given DHS’s use of waiver authority. In any event, by rejecting the ESP the tribe was setting the standards for compliance with waived laws higher than a general desire for DHS to do voluntarily the right thing. Sovereignty is often interpreted as an ability to operate independently and outside the confines of external dictates but the TOLC’s action demonstrates that U.S. tribal sovereignty, in particular, is exercised in large part through an ability to determine what is appropriate for their interests in a given situation.

The twin issues of access to the border through tribal land and the waiver of laws therein complicated the construction of border barriers on the Tohono O’odham Nation over the last two decades. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) pointed out that the Department of Interior (in which the Bureau of Indian Affairs is housed) could grant the Department of Homeland Security rights-of-way across the reservation only with the prior written consent of the tribe (Haddal, Kim, and Garcia Citation2009, 30). Even more importantly, the CRS questioned whether waiver authority even provides DHS with authority over another federal agency (30–31). Their closing comments on this issue reference a 1980 Supreme Court case that decided ultimately the federal government ‘holds all Indian lands in trust, and Congress may take such lands for public purposes, as long as it provides just compensation as required by the Fifth Amendment’ (31). This legal case itself referenced an earlier 1903 ruling that Congress (and, by extension, the federal government) has ‘paramount authority over the property of the Indians’ even where it may conflict with ‘the strict letter of a treaty with the Indians’ (The United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians et al. Citation1982, 408). As mentioned earlier, this potentially places the Tohono O’odham – who do not even have treaty-based Reservation lands – in an even more vulnerable position. Left unmentioned in the 2009 CRS report is the fact that the Sioux Nation that litigated the 1980 case has refused to accept the money offered in compensation for their lost land – funds which have now grown to over $1 billion with interest – because by doing so they would legally and permanently relinquish their claims to land which was taken from them (Streshinsky Citation2011). Indigenous attachment to the land and desires for sovereignty run deep, but unfortunately also lack an inviolable legal standing. As a result, it can sometimes be more effective to work out a compromise than engage in a drawn-out legal battle.

While tribal government political sovereignty is limited, it still pits CBP against a very different set of circumstances than elsewhere along the border. Leza argues that DHS authority outpaces tribal sovereignty (Citation2019, 119), and I concur that it is theoretically possible for CBP to bypass tribal governments in ways done elsewhere along the border. On other issues, tribal recognition has been ignored by the U.S. federal government when convenient or even unilaterally terminated. Courts have not consistently upheld the concept of ‘Native sovereignty,’ and today abrogating federal responsibilities that get in the way of border security has become the norm (Simpson and Correa Citation2020). Furthermore, both treaties and executive orders have been overturned by DHS waiver authority in other areas.Footnote14 However, in the context of Native American relations, there are benefits to collaboration even when DHS has the upper hand with waiver authority. There remains the possibility that tribal sovereignty could tip the scales in favor of the Tohono O’odham. Tohono O’odham concerns could potentially be upheld in the courts if DHS pushes their agenda too unilaterally. Nonetheless, the Tohono O’odham also recognize the historical limits of tribal sovereignty.

Integrated fixed towers

As an alternative (from the Tohono O’odham Nation’s perspective) and a supplement (from CBP’s perspective) to border barriers, a series of integrated fixed towers (IFTs) for monitoring illicit border traffic was proposed by during the Obama Administration. The program was an outgrowth of an earlier monitoring program known as the Southern Border Initiative Network (SBInet). The approval processes dragged on for a decade, but IFTs were ultimately overwhelmingly approved by the tribal government (TOLC Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2019). CBP adjusted the proposal to secure support for the project: fewer towers in the western district of Gu Vo (which was particularly concerned about the tower’s presence), design adjustments, road improvements, tying the project in with better cell phone service, etc. The extended approval process also gave the project time to be divisive, with some arguing that it undercut the need for additional and more invasive border barrier construction and others contending that monitoring towers were an equally insidious invasion of privacy and civil rights that should not be accepted as the new normal.

Unlike for border barrier construction, full compliance with relevant federal statutes was required for the IFT project, given that DHS waivers can be used only for barrier and road construction. The compliance element of this project and the need for review and comment were specifically mentioned in the Nation’s authorizing legislation. The first Preliminary Draft EA was distributed within CBP, the BIA, and the Tohono O’odham Nation in April 2014. A Revised Preliminary Draft was submitted to the same group in December 2015. In response, the Gu Vo District Chair sent a letter to CBP opposing the project in January 2016 (DHS Citation2017, Appendix A, 3).

A common emphasis among responses to the subsequent Draft Environmental Assessment (not preliminary), open for public comment from 5 April to 16 May 2016, was the need to acknowledge Gu Vo’s rejection of the IFTs. ‘Sovereignty’ or some version of that word was mentioned explicitly by half a dozen different people and the concept was even more widely referenced. People weighing in on the project described it as ‘an obvious violation of native sovereignty’ (DHS Citation2017, Appendix A, 10). Most took it as a given and did not specifically define the concept, casually referencing the ‘sovereign nation of the Tohono O’odham’ (DHS Citation2017, Appendix A, 12) or ‘the towers are an affront to O’odham national sovereignty’ (DHS Citation2017, Appendix A, 16). More widely used was the term ‘respect’ for the position of the Gu Vo District, and in places, it seems to have been talking points from a letter-writing campaign.Footnote15 Nonetheless, the idea was recognized by many who were not tribal members and built on the opposition mounting in Gu Vo against DHS actions (after Rifkin Citation2009). While Native sovereignty was an important concept in tribal discussions, the EA also provided a relatively rare opportunity for others to go on the record with their concerns over border security. By contrast, DHS waivers of NEPA abbreviate or entirely skip this opportunity for public input.

A year later, in July 2017, Gu Vo Community (the village) unanimously passed a resolution against the IFTs (Gu-Vo Community Council Citation2017Footnote16). A few months after that, Gu Vo District (a larger entity incorporating Gu Vo Community) proposed a compromise. The District suggested eliminating five towers in the northern part of the District along the eastern flank of the Ajo Mountains (Gu-Vo District Governing Council Citation2017). Primary concerns included culturally-sensitive sites, environmental impacts, and general militarization of the area. The two remaining towers were the southernmost ones nearest the border. This compromise reflected a common critique of CBP – to focus their enforcement at the border and not across the entire reservation. The resolution also put two significant conditions on CBP activity: First, it created a Culture Committee to communicate with CBP about culturally sensitive sites in the future. Secondly, it restricted the movement of the Mobile Surveillance System trucks to existing roads upon completion of the IFTs. In the Tohono O’odham political system, decisions are often discussed and endorsed locally before being voted on centrally. As a result, the two Gu Vo representatives joined their TOLC colleagues to unanimously pass the IFT project resolution in March 2019. Tribal Vice Chairman Verlon Jose told the Los Angeles Times that the final supportive vote was intended to be a compromise to dissuade the federal government from building a new wall in the area. Unfortunately, as Jose also pointed out, the Nation is ‘only as sovereign as the federal government will allow us to be.’ A Border Patrol spokesperson mentioned in the same article that there are no plans to reduce the number of agents and that the IFTs do not eliminate the need for new border barriers (Hennessy-Fiske Citation2019). While the likelihood of fewer agents was part of the early conversations around SBInet (TOLC Citation2007b), that perk evaporated as time passed.

Trump era

Pressure mounted in the Trump era for the extension of solid pedestrian barriers into rural areas. As pedestrian barriers became increasingly normalized, the Tohono O’odham Nation proved to be a notable holdout. Although no specific public plan was ever announced for such construction in this stretch of land, the tribe did not wait for Trump to take office to anticipate and denounce such a possibility. The tribe’s Vice Chairman was widely cited in the press for his comments that Trump would build a wall along the reservation only ‘over my dead body’ (e.g. Hennessy-Fiske Citation2019). While support for vehicle barriers and IFTs slowly developed over the years, the conversation over pedestrian barriers was quickly shut down. Even with a lighter environmental footprint allowing the relatively free movement of wildlife, vehicle barriers had also been controversial. As visual invasions on the landscape they were reminders of the difficult compromises made in the name of national security.

Despite appeals by tribal authorities and protests by some tribal members and allies, more imposing pedestrian walls did replace vehicle barriers in other areas of traditional O’odham territory, most notably in nearby Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Unlike on the reservation, tribal impact was more limited in such areas.

The Obama Administration completed much of the fencing mandated by the Secure Fence Act, and some have criticized barrier opponents as turning on the concept more recently because it was a signature project of President Trump. The distinction missed in such arguments is that construction under Bush and Obama generally saw more cooperation. The tribal government did hold the federal government accountable in ways they were not elsewhere along the border, but it was a compromise reached in the shadow of 9/11 security concerns and the completion of a congressional mandate rather than an end to itself. By contrast, the much more antagonistic and confrontational tone of the federal government during the Trump administration resulted in quick and substantial tribal resistance.

Discussion and conclusion

By contrast to tribal concerns of sustaining cross-border connections and minimizing impact on the environment and tribal members, the U.S. federal government prioritizes national strategies for tighter restrictions on border permeability. This is manifest in a more intense law enforcement presence and general militarization. The case of the Tohono O’odham and the quasi-sovereign nature of federally-recognized Native American tribes highlights the extent to which many border communities straddle the divergent priorities of local jurisdiction and national hegemony, and the role that Indigenous sovereignty plays in this context. Resolving this tension collaboratively also sheds insight on the potential relationships that could exist in other places along the border between the federal government and other (non-sovereign) communities. Relationships in which local communities are active partners challenge society to envision alternatives rather than impose a unilateral understanding of border security. As tribal chairman Norris said in a hearing in 2008:

We know from our own experience living on the border that security can be improved while respecting the rights of tribes and border communities, while fulfilling our duty to the environment and to our ancestors, and without granting any person the power to ignore the law. (U.S. House of Representatives Citation2008, 32)

While the Tohono O’odham hardly get everything they want out of this relationship, they exercise some sovereignty and have input on CBP activities. Most importantly, they provide a legal justification for collaboration by resisting the waiver of federal legal protections. Yet inherent sovereign tribal status is not all that makes this possible. Native sovereignty has rarely been a given throughout U.S. history. In the face of what many scholars recognize as ongoing settler colonialism, the tribe must be extremely vigilant to defend the concept and continually make and defend spaces where they can practice their political and social agency. CBP recognizes these dynamics to a certain degree and is willing to work with the tribe despite claims that they do not have to do so. Victory in a court case over sovereignty would not be a sure thing for either side.

Rather than the current national environment, which gives short shrift to local communities’ concerns over the construction of border barriers, the Tohono O’odham situation highlights the possibilities for a more positive working relationship between the federal government and local communities. The Border Patrol certainly faces an added and complicated layer of negotiation and partnership on the Tohono O’odham Nation. In the end, however, their border security mission endured and even garnered a degree of additional support by considering local concerns regarding border barriers, just as it did with the construction of security towers. Furthermore, by insisting on playing an active role in implementing federal border security on their lands, the Tohono O’odham exert their unique political agency, and highlight the deficiency of voluntary compliance. Their actions reinforce the importance of Indigenous sovereignty and, by extension, consultation with local communities more broadly.

Acknowledgements

I am forever grateful to the Tohono O’odham Nation and its members for allowing me to study borders and bordering processes in the context of the tribe. I hope my perspective as an academic researcher seeking a better understanding of these topics does justice to their complex circumstances, but it should be noted that I do not speak for or represent the tribe in any way. Special thanks to the Tohono O’odham Legislative Council for authorizing my research projects and to my colleagues and friends at Indivisible Tohono. Thanks as well to Scott Nicol and Matt Clark for sharing their collection of border environmental reviews and to Scott for his expertise regarding the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Finally, thanks to U.S. Customs and Border Protection for their responsiveness to my FOIA requests. The support of many others not listed here is also appreciated. Any errors, omissions, or incomplete consideration of the topic are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Although only one of several subdivisions within the organization, ‘Border Patrol’ is often used synonymously with the CBP in popular use and in this paper because it is the most prominent manifestation of CBP in border communities. In turn CBP is a division within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). This paper generally refers to DHS when referring to waiver determinations and upper administration and CBP when referring to implementation of the waivers and local interactions.

2. While others elsewhere do face increased security at airports and various forms of everyday surveillance, border security per se falls more specifically on residents of the borderlands.

3. On one of my field reconnaissance trips south of Yuma, Arizona to check out border wall construction in 2017, an agent was notably sharper with my passengers and colleagues who were Indigenous, questioning their presence in my car which was stopped near the border on a canal road being used by nearby residents for an evening walk. By contrast, the next day when I was alone but also still near the international border on another canal road east of Yuma with no one else nearby, my presence barely registered with agents on patrol. Individual agents have different approaches and reactions and other elements of context matter, of course, and this is not to say all the rest of my field interactions with the Border Patrol were seamless or that Natives and Hispanics/Latinxs are consistently harassed. Nonetheless, my experiences here reflect my wider knowledge of such interactions along the border.

4. The term ‘barrier’ is used broadly to refer to any structure built near a border for the purpose of blocking entry into the country. Fence here refers specifically to one that blocks vehicle traffic but can be easily traversed by an individual at ground level. ‘Wall’ is reserved to refer to a more impenetrable barrier blocking pedestrian as well as vehicular traffic and may or may not allow for cross-border visibility. Others may use these terms in other ways. The Secure Fence Act, for example, does not restrict itself to structures that only block vehicles.

5. Where otherwise clear, the Tohono O’odham are also sometimes referred to as simply ‘O’odham,’ although this term could be construed in other contexts to include nearby related tribes.

6. For examples see Censored News Citationn.d.; Defend O’odham Jewed Citationn.d.; Gentry et al. Citation2019; Hia-Ced Hemajkam, LLC Citationn.d.; Levy Citation2017, 13, 24, 30–32; Lucero Citation2014; Mott Citation2015, Citation2016; O’odham Anti Border Collective, Citationn.d.; O’odham Solidarity Project Citationn.d. and the Tohono O’odham Hemajkam Rights Network Citationn.d.. Regarding opposition by O’odham Voice Against the Wall and waiver authority specifically see also Leza (Citation2019, 63). Leza also discusses barrier opposition by other tribal members and activist groups, see esp. Ch. 2. On another level and reflective of pan-tribal sovereignty, see the border-crossing and tribally driven security consultation proposals by the Tribal Border Alliance (Citation2019). The Tohono O’odham Nation’s resolve and support on this issue is also seen in resolutions supportive of the Nation’s position by the Intertribal Association of Arizona and the National Congress of American Indians (see Tohono O’odham Nation Citation2017).

7. While AIRFA raised some helpful issues, nine years after its passage Michaelsen (Citation1987, 126) was already describing it as ‘a toothless resolution’. RFRA was struck down in relation to state and local governments, even as it continues to have relevance for the federal government itself, but several key suits related to the practice of Native American religion under RFRA were ultimately not successful (Wiles Citation2010). It seems likely that the reason RFRA was waived less frequently is to allow the Trump administration to avoid the optics of waiving religious liberty protections given that the religious right was one of his most fervent constituencies. Vice President Pence is certainly very acquainted with RFRA, having signed the Indiana version of that law during an uproar over its LGBTQ implications (Knowles Citation2019). Even as it is a crucial piece of legislation for the affirmation of Indigenous sovereignty, AIRFA is less critical in this light and affects fewer voters, certainly fewer Trump supporters, given Native Americans’ overwhelming tendency to vote for Democrats.

8. Another RFRA case was brought by La Lomita Mission in Mission, Texas. The La Lomita situation was temporarily resolved when that specific tract of land was exempt from border wall construction as part of a compromise funding bill in February 2019.

9. Legacy vehicle barriers are those segments constructed prior to the Secure Fence Act.

10. Prior to this point the waiver of laws had been used vary narrowly. Nationally there had been only three waiver determinations and this was for specific projects in San Diego (14.0 miles or 22.5 km), the Barry Goldwater Air Force Range in western Arizona (38.1 miles or 61.3 km), and the San Pedro River in eastern Arizona (7.1 miles or 11.4 km).

11. The only determinations in which NEPA was not waived were two focused on procurement regulations. In both cases, NEPA was waived for these geographic areas under earlier waiver determinations.

12. Environmental documents developed by DHS during the process of border infrastructure construction are in the public domain. Those cited in this paper (indicated in the Reference section with a # symbol) and others are assembled centrally in Madsen (Citation2023b).

13. Protecting traditional O’odham land in Mexico and sustaining a cross-border presence is also important but given the international context many members and tribal officials feel there is no specifically prescribed legal role for the tribe there and limited action is possible.

14. For example, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1916 and the Presidential proclamations of 13 April 1937 establishing Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and 5 November 1952 establishing Coronado National Monument, both in Arizona. In these cases, the protections offered were eliminated in terms of border barrier construction even as the Treaty and Monuments themselves continued to exist. Interestingly the waiving of a treaty with Mexico does not seem to have had any diplomatic repercussions.

15. Eleven out of fifteen ‘respect’ comments were variations on the theme of ‘respect the will of the Tohono O’odham nation to not have these towers on their land. Respect the Gu-Vo District position of “NO IFTs whatsoever.” Respect the Gu-Vo District’s actions to protect and preserve sacred places, ceremonial places and burial place and ancient village places. Respect the Gu-Vo District’s efforts to protect future generations. Respect the authority of Gu-Vo District as O’odham authority, voice of O’odham Communities and community members’ (DHS Citation2017, Appendix A, 11).

16. Both ‘Gu Vo’ and ‘Gu-Vo’ are common spellings. The latter is used here only when citing directly to a source using the dash.

References

- ACLU. n.d. “Know Your Rights: 100 Mile Border Zone.” Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.aclu.org/know-your-rights/border-zone/.

- Amnesty International. 2012. “In Hostile Terrain: Human Rights Violations in Immigration Enforcement in the US Southwest.” https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ai_inhostileterrain_032312_singles.pdf.

- Baker (Michael Baker Jr., Inc.). 2013. “Border Fence Locations.” October 23, 2013. https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/borderwall/maps/background-maps.html. See also Madsen (2023a).

- Barnett, George S. 1989. “Report Regarding the Tohono and Hia-Ced O’odham of Mexico Indigenous Peoples’ Loss of Their Land, Violations of Convention 107 of the ILO, Violations of Treaty Rights, and the Lack of Protection for Cultural and Religious Rights of the O’odham of Mexico and the United States.” Tohono O’odham Nation, October 9, 1989.

- Bell, Monte R. 1985. “History of Establishment of Federal Zone (So Called 6O-Foot Strip) Along the Western Land Boundary by Presidential Proclamations of 1897 and 1907, and Chronology of Pertinent Events Regarding Jurisdiction and Works Constructed Thereon.” Internal memoran-dum. June 14, 1985. El Paso, Texas: International Boundary and Water Commission, United States and Mexico, United States Section.

- Boyce, Geoffrey A. 2019. “The Neoliberal Underpinnings of Prevention Through Deterrence and the United States Government’s Case Against Geographer Scott Warren.” Journal of Latin American Geography 18 (3): 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2019.0048.

- Castillo, Guadalupe, and Margo Cowan, eds. 2001. It’s Not Our Fault—The Case for Amending Present Nationality Law to Make All Members of the Tohono O’odham Nation United States Citizens, Now & Forever. Sells, Arizona: Tohono O’odham Nation, Executive Branch.

- CBP. 2019. “CBP Environmental Documents.” November 21, 2019. https://www.cbp.gov/about/environmental-management-sustainability/cbp-environmental-documents. # This URL is no longer available but many ESSRs can be found at https://www.cbp.gov/about/environmental-management in the “Archive” section.

- CBP. 2020. “Environmental Stewardship Plans (ESPs) and Environmental Stewardship Summary Reports (ESSRs).” November 25, 2020. https://www.cbp.gov/about/environmental-management-sustainability/documents/esp-essr. # This URL is no longer available but similar content available at https://www.cbp.gov/faqs/what-are-environmental-stewardship-plans-esps.

- Censored News. n.d. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://bsnorrell.blogspot.com/.

- Connolly, Colleen. 2020. “Border Wall Desecrates Native American Lands in Southern California and Arizona.” The American Prospect, October 12, 2020. https://prospect.org/civil-rights/border-wall-desecrates-native-american-lands-in-southern-cal/.

- Cornelius, Wayne A., and Idean Salehyan. 2007. “Does Border Enforcement Deter Unauthorized Immigration? The Case of Mexican Migration to the United States of America.” Regulation & Governance 1 (2): 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00007.x.

- Cornell Law School, Legal Information Institute. n.d. “8 U.S. Code § 1103 - Powers and duties of the Secretary, the Under Secretary, and the Attorney General.” Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1103.

- Defend O’odham Jewed [trans. Defend O’odham Land]. n.d. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.instagram.com/defendoodhamjewed/.

- DHS. 2006. Final Environmental Assessment for the installation of permanent vehicle barriers on the Tohono O’odham Nation Office of Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Arizona. Washington, DC. December. #

- DHS. 2008a. Final Environmental Stewardship Plan for the Construction, Operation, and Maintenance of Tactical Infrastructure U.S. Border Patrol Yuma Sector, Arizona and California. Washington, DC. May. #.

- DHS. 2008b. Final Environmental Stewardship Plan for Construction, Operation, and Maintenance of Tactical Infrastructure, Segments DV-2, DV-3B, and DV-4C, U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector Ajo and Casa Grande Stations, Arizona. September. #

- DHS. 2009. Draft Supplemental Environmental Assessment for the Construction, Operation, and Maintenance of Tactical Infrastructure, Segments DV-2, DV-3C, and DV-4C U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Ajo and Casa Grande Stations, Arizona. Washington, DC. September. #

- DHS. 2012. Final Environmental Assessment Addressing Proposed Tactical Infrastructure Maintenance and Repair Along the U.S./Mexico International Border in Arizona. December. #

- DHS. 2017. Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Arizona. Washington, DC. March. #.

- Eccleston, Charles, and J. Peyton Doub. 2012. Preparing NEPA Environmental Assessments: A User’s Guide to Best Professional Practices. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Erickson, Winston P. 1994. Sharing the Desert: The Tohono O’odham in History. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Gentry, Blake, Geoffrey Alan Boyce, Jose M. Garcia, and Samuel N. Chambers. 2019. “Indigenous Survival and Settler Colonial Dispossession on the Mexican Frontier: The Case of Cedagĭ Wahia and Wo’oson O’odham Indigenous Communities.” Journal of Latin American Geography 18 (1): 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2019.0003.

- Grichting, Anna, and Michelle Zebich-Knos, eds. 2017. The Social Ecology of Border Landscapes. New York: Anthem Press.

- Gu-Vo Community Council. 2017. “Opposing the Department of Homeland Security/Customs and Border Protection Electronically Integrated Fixed Towers within the Boundaries of the Gu-Vo District.” Resolution No. GVC-17-001. July 30, 2017.

- Gu-Vo District Governing Council. 2017. “Approving the Amendment Alternate Routes 1 & 2 Environmental and Archaeological Survey.” Resolution No. GV-17-140. November 7, 2017.

- Haddal, Chad C., Yule Kim, and Michael John Garcia. 2009. “Border Security: Barriers Along the U.S. International Border.” March 16, 2009. Congressional Research Service. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/RL33659.pdf.

- Hennessy-Fiske, Molly. 2019. “Arizona Tribe Refuses Trump’s Wall, but Agrees to Let Border Patrol Build Virtual Barrier.” Los Angeles Times, May 9, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-arizona-tribe-border-patrol-trump-wall-20190509-htmlstory.html.

- Hia-Ced Hemajkam, LLC [trans. Sand People, LLC]. n.d. Accessed October 16, 2022. http://hiaced.com/.

- Hoover, J. W. 1935. “Generic Descent of the Papago Villages.” American Anthropologist 37 (2): 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1935.37.2.02a00060.

- Ingram, Paul. 2022. “Native Activist Found Not Guilty in Border Protest After New Arguments on Religious Freedom Defense.” Tucson Sentinel, January 19, 2022. https://www.tucsonsentinel.com/local/report/011922_ortega_hearing/native-activist-found-not-guilty-border-protestafter-new-arguments-religious-freedom-defense/.

- Jones, Richard Donald. 1969. “An Analysis of Papago Communities 1900–1920.” PhD diss., University of Arizona.

- Knowles, David. 2019. “A Tiny Chapel—And a Law Beloved by Evangelicals—Might Stand in the Way of Trump’s Wall.” February 12, 2019. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/church-uses-religious-freedom-restoration-act-to-contest-trumps-new-wall-section-221341325.html.

- Lenzerini, Federico. 2006. “Sovereignty Revisited: International Law and Parallel Sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples.” Texas International Law Journal 42 (2): 155–189.

- Levy, Taylor. 2017. “There’s No O’odham Word for Wall: Tribal Sovereignty, Resistance, and Acquiescence to the Militarization of the Border and the U.S.-Mexico Border Wall.” https://www.academia.edu/36572698/THERE_S_NO_O_ODHAM_WORD_FOR_WALL_TRIBAL_SOVEREIGNTY_RESISTANCE_AND_ACQUIESCENCE_TO_THE_MILITARIZATION_OF_THE_BORDER_AND_THE_U_S_MEXICO_BORDER_WALL.

- Leza, Christina. 2019. Divided Peoples: Policy, Activism, and Indigenous Identities on the U.S.- Mexico Border. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

- Lucero, José Antonio. 2014. “Friction, Conversion, and Contention: Prophetic Politics in the Tohono O’odham Borderlands.” Latin American Research Review 49 (S): 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2014.0055.

- Luna-Firebaugh, Eileen. 2005. “‘Att Hascu ‘Am O ‘I-Oi? What Direction Should We Take?: The Desert People’s Approach to the Militarization of the Border.” Washington University Journal of Law & Policy 19:339–363.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2007. “Local Impacts of the Balloon Effect of Border Law Enforcement.” Geopolitics 12 (2): 280–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650040601168990.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2014a. “The Alignment of Local Borders.” Territory, Politics, Governance 2 (1): 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2013.828651.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2014b. “A Basis for Bordering: Land, Migration, and Inter-Tohono O’odham Distinction Along the U.S.-Mexico Line.” In Making the Border in Everyday Life, edited by Reece Jones and Corey Johnson, 93–116. London: Ashgate.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2015. “Research Dissonance.” Geoforum 65:192–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.020.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2022. “Institutionalising the Exception: Homeland Security Sec. 102(c) Waivers and the Construction of Border Barriers.” Geopolitics. Published electronically October 25, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2022.2126766.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2023a. “History and Practice of 8 U.S. Code §1103 Notes, Section 102(c) - Improvement of Barriers at Border.” Dryad dataset. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.08kprr547.

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2023b. “Border Barrier Environmental Documents from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.” Dryad dataset. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.qnk98sfn0.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. 2020. Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674249998.

- Martinez, Adriana E., and Susan W. Hardwick. 2009. “Building Fences: Undocumented Immigration and Identity in a Small Border Town.” Focus on Geography 52 (4): 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8535.2009.tb00254.x.

- Michaelsen, Robert S. 1987. “Civil Rights, Indian Rites.” In Church-State Relations: Tensions and Transitions, edited by Thomas Robbins and Roland Robertson, 125–133. New Brunswick: Transaction Books. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003070313-13.

- Mott, Carrie. 2015. “Notes from the Field: Re-Living Tucson - Geographic Fieldwork as an Activist-Academic.” Arizona Anthropologist 24:33–41.

- Mott, Carrie. 2016. “The Activist Polis: Topologies of Conflict in Indigenous Solidarity Activism.” Antipode 48 (1): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12167.

- Nabhan, Gary Paul. 1982. The Desert Smells Like Rain: A Naturalist in Papago Indian Country. New York: North Point Press.

- Naranjo, Reuben Vasquez, Jr. 2011. “Hua A’aga: Basket Stories from the Field, the Tohono O’odham Community of A:l Pi’ichkiñ (Pitiquito), Sonora, Mexico.” PhD diss., University of Arizona.

- Nicol, Heather N. 2010. “Reframing Sovereignty: Indigenous Peoples and Arctic States.” Political Geography 29 (2): 78–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.02.010.

- O’odham Anti Border Collective. n.d. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.facebook.com/AntiBorderCollective/.

- O’odham Solidarity Project n.d. Accessed November 28, 2021. http://www.solidarity-project.org/. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20210530142701/http://www.solidarity-project.org/.

- Papago Council. 1979a. “Sonoran-Papagos.” Resolution No. 43-79. May 16, 1979. https://tolc-nsn.gov/docs/actions79/4379.pdf.

- Papago Council. 1979b. “Authorizing Issuance of Enrollment Applications to Sonoran Papagos.” Resolution No. 45-79. May 16, 1979. https://tolc-nsn.gov/docs/actions79/4579.pdf.

- Rifkin, Mark. 2009. “Indigenizing Agamben: Rethinking Sovereignty in Light of the ‘Peculiar’ Status of Native Peoples.” Cultural Critique 73:88–124. https://doi.org/10.1353/cul.0.0049.

- Roosevelt, Theodore. 1907. “A Proclamation.” In United States Statutes at Large 35 (2): 2136–2137. May 27, 1907. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924065976148.

- Rozemberg, Hernán. 2001. “Strangers in Their Own Land: Border Tensions Cause Woes for Tohono O’odham.” The Arizona Republic, November 26, 2001. Newspapers.com.

- Runner, The. 2004. “Border Patrol Agents Accused of Assault Won’t Be Moved.” October 14, 2004.

- Runner, The. 2014. “A Year After Facing Border Patrol Agent’s Gun, Man Awaits Resolution.” July 18, 2014.

- Schermerhorn, Seth. 2019. Walking to Magdalena: Personhood and Place in Tohono O’odham Songs, Sticks, and Stories. Baltimore, MD: American Philosophical Society. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcszzwf.

- Silvern, Steven E. 1999. “Scales of Justice: Law, American Indian Treaty Rights and the Political Construction of Scale.” Political Geography 18 (6): 639–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(99)00001-3.

- Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Simpson, Joseph M., and Jennifer G. Correa. 2020. “Abrogation of Public Trust in the Protected Lands of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley.” Society & Natural Resources 33 (6): 806–822. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2020.1725203.

- Singleton, Sara. 2008. “‘Not Our Borders’: Indigenous People and the Struggle to Maintain Shared Cultures and Polities in the Post-9/11 United States.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 23 (3): 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2008.9695707.