Abstract

The manuscript presents maps of internationally important wetlands located in the Kis-Sárrét (Hungary) from 1860 to 2008. The study area is located in south-east Hungary, in the Körös-Maros National Park and covers 8048 ha. For the historic map review, we used digitized data of topographic maps from the period of two military surveys and the Second World War. We also made habitat maps of the area in 2007 and 2008. Data processing, and the establishment of a database of the mapped area, was made using QuantumGIS 1.7.0 and Esri ArcView GIS 3.2. Maps were produced using Esri ArcGIS 10.0 and show where and in what ratio the once extensive wetlands occurred, how they changed and in which part of the area they survived in different mapping periods. They provide a point of reference for the monitoring of wetlands, contributing to the long-term conservation of these valuable habitats. Maps and diagrams show that between 1860 and 1944 wetland extent decreased by half. The ratio of natural, ‘purely’ wet habitats reaches only 4.67% now. Wetlands typically occur in habitat complexes, therefore not ‘purely’ wet habitats (20.77%) also have to be taken into account. Considering this, and a recent habitat reconstruction, the extent of wetlands is more favourable today than it was in 1944. However, to sustain them requires care and well-planned management to which the maps presented here provide an important basis.

1. Introduction

In the central part of the Carpathian Basin, following the ice age, floodplain habitats became typical along the rivers. At the same time, forest steppe and loess grassland developed at higher altitudes, whilst various wetlands evolved in lower lying places (CitationJakab, 2012; CitationSümegi, 2011). In the Great Hungarian Plain, which contains the study area, a series of extremely diverse, mosaic-like, habitats have developed. This is due to the effect of the soil, microrelief and microclimate (CitationJakab, 2012; CitationRakonczai, 2011). The transformation of the original vegetation of the Great Plain began relatively early, when man first modified the landscape (CitationSümegi; 2003; CitationWillis, 2007). Bringing land into agricultural cultivation and river regulation carried out in the nineteenth century has had the greatest influence on the transformation of the landscape. As a result, habitats of good soil (loess grassland, forest steppe), floodplains and, following the drainage, marshlands were converted to farmland (CitationDuray & Hegedűs, 2005; CitationJakab, 2012; CitationKertész, 2003; CitationPaládi-Kovács, 1979; CitationRakonczai, 2011; CitationSzűcs, 1977).

The mapped area – the Kis-Sárrét (means ‘Little Mudland’) – is located in the south-eastern part of Hungary, within the administrative border of Körösnagyharsány, Biharugra, Zsadány, Geszt and Mezőgyán villages, covering 8048 ha. It is an area of international importance within the Körös-Maros National Park, part of the Natura 2000 network, with some of its habitats falling under the Ramsar Convention and is registered as an internationally Important Bird Area (CitationTardy, 2007). The third largest fishpond system of the Carpathian Basin, the Biharugra Ponds, can be found within this area.

The central part of the Kis-Sárrét was dominated by a coherent marshland during the Holocene (CitationSümegi, 2004, Citation2011). However, as a result of human activity transforming the landscape, the marshy, waterlogged areas have been fragmented and their extent decreased significantly over the last 300 years (CitationJakab, 2012; CitationSümegi, 2003). The once waterlogged depressions gradually dried out and became salinized, whilst land use was transformed with the amount of arable land and pasture increasing (CitationJakab, 2012). In spite of large-scale transformation of the landscape, there are important habitats of high conservation value within the Kis-Sárrét. The complexity of natural factors and specifically the influence of climatic and edaphic conditions on each other play a key role in the survival of these valuable habitats (CitationBodrogközy, 1965, Citation1966; CitationKertész, 2003; CitationMarosi & Somogyi, 1990; CitationStefanovits, Filep, & Füleky, 1999).

In the present study, we focus on one of the most valuable types of habitat of the Kis-Sárrét: the wetlands. They are of importance as the extent and diversity of wetlands worldwide decrease, along with the change of landscape ecological factors and the increase of farmland (CitationBáldi & Faragó, 2007; CitationHongyu, Shikui, Zhaofu, Xianguo, & Qing, 2004; CitationIhse, 1995; CitationKleijn & Sutherland, 2003; CitationLastrucci, Landi, & Angiolini, 2010; CitationLiu, Lu, & Zhang, 2004; CitationTilman, Cassman, Matson, Naylor, & Polasky, 2002; CitationTamisier & Grillas, 1994; CitationTscharntke, Klein, Kruess, Steffan-Dewenter, & Thies, 2005;CitationVan der Nat, Tockner, Edwards, Ward, & Gurnell, 2003). For the preservation of habitats and the development of conservation plans, it is essential to research the past state and to record the present one (CitationBiró, 2008; CitationNagy, 2008; CitationPásztor, Bakacsi, & Szabó, 2008). Therefore, we undertook a review of historical maps for the wetlands of the Kis-Sárrét. In the course of our work, we both used historic maps and completed a detailed survey of the area's present habitats. The importance of the resultant maps is that they provide an overview of the wetland habitats of the Kis-Sárrét, detailing their extent in historic times. They show that where and in what ratio these habitats occurred during different mapping periods, how they changed and in which part of the area they survived. In addition, the maps provide a point of reference for the monitoring of the wetlands, and so contribute to the long-term conservation of wetland habitats representing extraordinary value.

2. Methods

The aim of the mapping was to provide an historic overview of the wetlands of the Kis-Sárrét region. For this reason, in order to display the past state, we processed historic maps, whilst for recording the present state we undertook habitat mapping.

For the previous state of the Kis-Sárrét, we digitally processed the following topographic maps: (1) Second military survey [Ministry of Defence – Military History Institute and Museum (MD-MHIM) Collection of Maps (XLII/54–56 and XLIII/54–56)], produced in 1860 and 1863, at a scale of 1:28,800 (CitationTímár et al., 2006); (2) Third military survey [MD-MHIM Collection of Maps (5167/3–4 and 5267/1–4)], produced in 1884 at a scale of 1:25,000 (CitationBiszak, Tímár, Molnár, & Jankó, 2007) and (3) Second World War [MD-MHIM Collection of Maps (5167/NY-K and 5267/NY-K)], produced between 1940 and 1944, at a scale of 1:50,000 (CitationTímár, Molnár, Székely, Biszak, & Jankó, 2008).

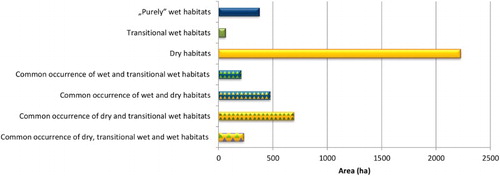

To display the current wetlands of the area, we used the categories of the General National Habitat Classification System of Hungary (GNHCSH) (CitationFekete, Molnár, & Horváth, 1997) as a basis. We surveyed all habitat types occurring in the area, covering the whole vegetation period in 2007/2008. For the preliminary separation of habitats, we used aerial photographs, with accurate demarcation of habitat patches in the field made using hand-held global positioning system receivers. In the subsequent database, the habitat type (or types) typical in the habitat patch, as well as the common, protected and invasive plant species, was recorded. As the natural habitats of the area occur in a mosaic-like structure, the demarcation of the patches was difficult. During the habitat mapping, we demarcated 580 different habitat patches, which resulted in 191 types of (GNHCSH) habitat combination because of the strong mosaic-like structure of the area. We classified these 191 types of habitat combination into 28 habitat categories in order to display them on the map (see Main Map – Habitats of Kis-Sárrét 2007–2008). To emphasize the extent to which the wet character appears in the present habitats of the Kis-Sárrét, we classified the occurring habitats and habitat groups according to their wet or dry quality (). Their areal distribution is shown both in the form of a map and a diagram.

Table 1. Habitats grouped according to their wet or dry character. (Categories shown on the habitat map ungrouped according to their wet or dry characters: man-made fishpond, agricultural land and inhabited area).

3. Results

3.1. Historic maps

On the layers resulting from the processing of historic maps, we show man-made open water surfaces. However, when presenting and comparing the maps we take into account only the natural wetlands, not man-made fishponds.

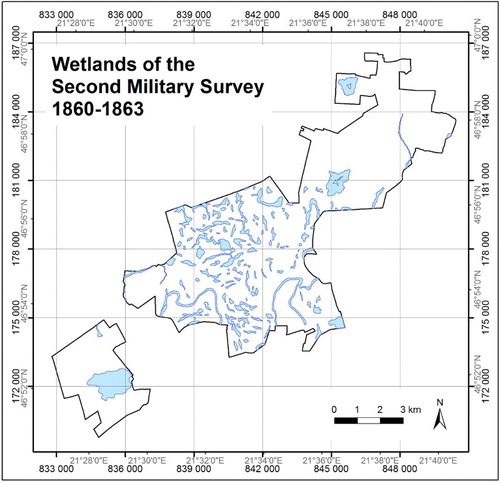

3.1.1. 1860–1863

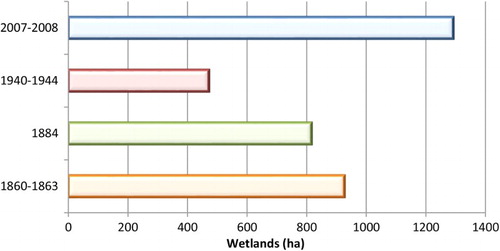

The earliest map originates from the period of time of the first stage of drainage works carried out between 1856 and 1879. These works began one of the major landscape changes that would change the wetlands. Wet habitats typically occur in the central part of the area and their distribution is quite even (). They occur in 129 patches, covering 926.1 ha (), 11.5% of the study area. Three bigger wetland patches can clearly be separated; the upper one is found in the Ugrai-rét (a meadow), the middle one in the area of the Fishponds of Ugra (established later on), whilst the lower one is in the area of the present marshland at Kisgyanté. It is interesting that the meadow of Sző-rét, which is an important wetland now, does not appear on the map.

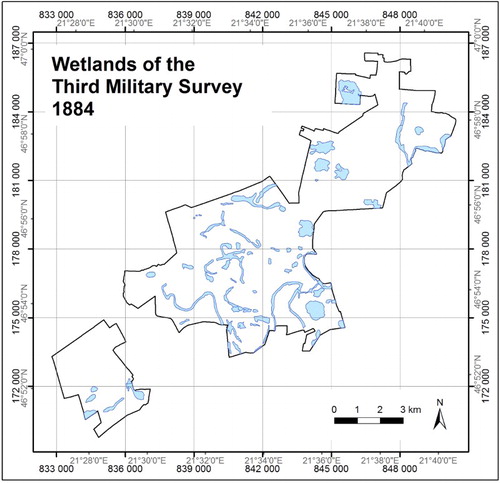

3.1.2. 1884

Based on the third military survey of 1884, the landscape was now much drier, a result of the drainage completed in 1879 (). Compared to the previous mapping period, the extent of wetlands is now significantly less; only 70 patches can be separated with a total area of 815.15 ha () (10.12%). The smaller wet patches have disappeared or merged into larger ones in some places (e.g. Baglyas). Due to the drainage, several wetlands with an almost regular shape have developed. In the upper part of the study area new, larger wetlands evolved, such as the meadow of Sző-rét. In addition to the waterlogged patches in the area of the present man-made Fishponds of Ugra, a coherent wetland can be seen in the place of the Begécs Pond system. Another important change is that the area of the Kisgyanté Marshland has significantly decreased and become fragmented.

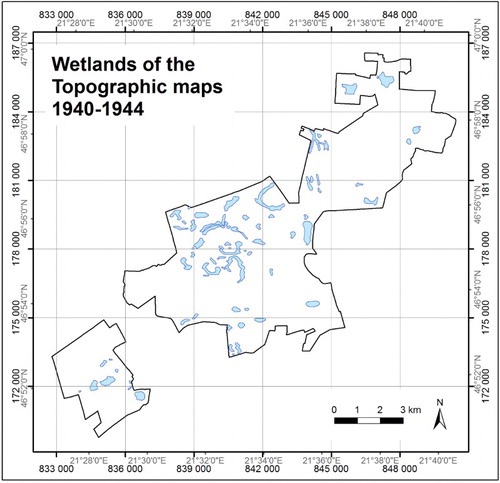

3.1.3. 1940–1944

The final historic data set () from the Second World War shows that the ratio of wetlands has further decreased – there are 71 patches covering 471.29 ha (). The primary cause is anthropogenic transformation (drainage, melioration) in order to bring land into agricultural cultivation. Wetlands have become fragmented, and their area has significantly decreased. The formerly extensive Meadow of Ugra has shrunk to less than half of its original size. The watery depressions around the Fishpond of Ugra have also lost part of their area, the waterlogged patch of Baglyas grassland has also largely diminished and many streams have dried out and disappeared.

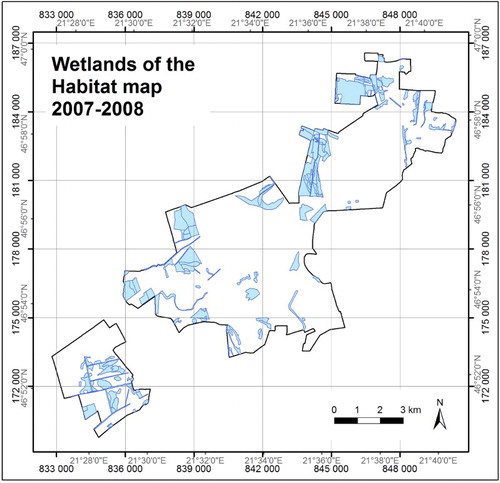

3.2. Current map

The present state of the Kis-Sárrét is shown on the habitat map for 2007 and 2008. The 191 types of habitat and habitat groups recorded in 580 habitat patches were grouped into 28 categories. To demonstrate the extent of wetness of the wetlands, we grouped natural and semi-natural habitats of the 28 habitat categories according to their wet or dry character, which is also shown on the map ().

The habitat map shows that the one-time coherent euhydrophyte and marshy area has significantly diminished, and the majority of wetlands appear in habitat complexes. The dominantly wet habitats (C) are typical on 13.93% of the area, and from this the ratio of ‘purely’ wet habitats (C/4) is only 4.67% (, ). Coherent wetlands have survived in the meadow of Sző-rét, westward from the Fishponds of Ugra and also along the west side of Begécs Pond and in the Vátyon region (). In the two latter areas, the national park has carried out landscape reconstruction with coherent marshland created around the Begécs Pond by damming. In the Vátyon region – where the water level has been regulated by lock since 2000 – one of the most varied, mosaic-like and diverse wetlands of the Kis-Sárrét has developed. In the transitional wet habitats (C/3) category, we grouped the gallery forests, independent stands of which can be found on no more than 0.77% of the area, and are typical only in a few patches (forests of Eperjes, Vátyon and Csillaglapos). From among the habitat complexes containing wetlands, saline habitats and euhydrophyte habitats with marshes represent the biggest ratio (4.69%). The state of wetlands is well demonstrated by the species recorded in the habitat patches. In the ‘purely’ wet habitats (C/4) (euhydrophyte wet habitats with marshes and marshes), the Natura 2000 designator Cirsium brachypodium occurs from among the protected species. Though in the complexes of saline habitats and wetlands the number of protected species is larger, these belong to species typical in saline habitats (Aster sedifolius and Aster tripolium). At the same time, these complexes are also affected by invasive species (Bidens frondosus and Amorpha fruticosa), which demonstrates the secondary character of these habitats.

Dry habitats (A) – the majority of which are saline ones – occur independently on 27.64% of the area (), that is, they are almost six times more frequent than the ‘purely’ wet habitats. In respect of their spatial distribution, they can be found in continuous form in the region below the Begécs Ponds and near Mezőgyán. The extensive saline habitats and saline complexes of the Kis-Sárrét are extremely valuable (its endemic and protected plant species is Plantago schwarzenbergiana, its further protected species are Peucedanum officinale, Iris spuria, A. sedifolius and A. tripolium), the conservation of which is highly important.

4. Conclusion

Data gained from the maps () presenting the history of the wetlands of the Kis-Sárrét region and related diagrams clearly show that the extent of wetlands drastically decreased by 1944 () dropping to half the size in 1860. The drivers for this large-scale change lie in river regulation and landscape transforming activities carried out in order to bring land into agricultural cultivation. According to contemporary mapping (2007/2008), the extent of patches containing ‘purely’ wet habitats (C/4) is only 4.67% at present. Within the separate patches, however, due to the mosaic-like structure of habitats, wetlands can rarely be demarcated on their own and typically occur in habitat complexes. Therefore, the ratio of not ‘purely’ wet habitats (C/1: Common occurrence of wet and dry habitats, C/2: Common occurrence of wet and transitional wet habitats, C/3: Transitional wet habitats, 9.26%) should also be taken into account (, ). The variegated habitats, and their appearance in complexes, demonstrate the mosaic-like features of the region's environment. As a result of this, former habitats did not vanish – they are just repressed – and with adequate environmental conditions can be extended again. That is the reason why the region's varied habitat diversity could be sustained through the centuries of change in spite of large-scale landscape transformation. The success of wetland preservation activity in the national park (water retention and regulation in the Sző-rét, Kisvátyon and Kisgyanté parts of the region) is due in part to this, and has resulted in a more favourable extent of wetlands now than since 1940–1944. To increase and sustain the extent of wetlands, the Kis-Sárrét serves as a good example of international relevance.

Table 2. Changes of wetlands (1860–2008).

Historic aspects of wetlands are important, because with their help we can investigate the previous and current extent and spatial location of wetlands of a landscape – the Kis-Sárrét region is presented here as a case study. The habitat map also displays the current state and forms a detailed database of the area to serve as baseline data. This is an important foundation for future monitoring activity.

Software

For the processing of the historic maps and the habitat map, QuantumGIS 1.7.0 (www.qgis.org) and Esri ArcView GIS 3.2 were used. For map production, we used Esri ArcGIS 10.0.

WETLAND HABITATS OF THE KIS-SÁRRÉT 1860-2008 (KÖRÖS-MAROS NATIONAL PARK, HUNGARY)

Download PDF (69.6 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Editor in Chief and Reviewers that their constructive comments and suggestions helped the higher level preparation of the manuscript and the map. In addition, we would like to express our thanks to the Körös-Maros National Park Directorate, to the staff of the Map Collection of the Military History Institute and Museum and to the Arcanum Database Ltd.

Funding

The research was supported by ‘TÁMOP- 4.2.2/B-10/1-2010-011’, and the Research Centre of Excellence – ‘17586-4/2013/TUDPOL’ project.

References

- Báldi, A., & Faragó, S. (2007). Long-term changes of farmland game populations in a post-socialist country (Hungary). Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 118, 307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.05.021

- Biró, M. (2008). Lehetőségek a történeti térképek tartalmi gazdagítására; természetvédelmi és botanikai célú alkalmazások. In Z. S. Flachner, A. Kovács, & E. Kelemen (Eds.), A történeti felszínborítás térképezése a Tisza-völgyben. Szemináriumkötet (pp. 78–80). Budapest: SZÖVET.

- Biszak, S., Tímár, G., Molnár, G., & Jankó, A. (Eds.). (2007). Ungarn, Siebenbürgen, Kroatien-Slawonien – The Third Military Survey (1869–1887), 1:25000, Digitized Maps of the Habsburg Empire. Budapest: MD Military History Institute and Museum, Arcanum Adatbázis Ltd.

- Bodrogközy, G. Y. (1965). Ecology of the halophytic vegetation of the Pannonicum III. Results of the investigation of the Solonetz of Orosháza. Acta Biologica, 11, 3–25.

- Bodrogközy, G. Y. (1966). Ecology of the halophytic vegetation of the Pannonicum V. Results of the investigation of the ‘Fehértó’ of Orosháza. Acta Botanica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 12, 9–26.

- Duray, B., & Hegedűs, Z. (2005). Geoecological mapping in a Kis-Sárrét study area. Acta Climatologica et Chorologica, Tom. 38–39, 47–57.

- Fekete, G., Molnár, Z. S., & Horváth, F. (Eds.). (1997). A magyarországi élőhelyek leírása, határozója és a Nemzeti Élőhely-osztályozási Rendszer. Nemzeti Biodiverzitás-monitorozó Rendszer II. Budapest: Magyar Természettudományi Múzeum.

- Hongyu, L., Shikui, Z., Zhaofu, L., Xianguo, L., & Qing, Y. (2004). Impacts on wetlands of large-scale land-use changes by agricultural development: The small Sanjiang Plain, China. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 33(6), 306–310.

- IHSE, M. (1995). Swedish Agricultural Landscapes – Patterns and Changes During the Last 50 years, Studied by Aerial Photos. Landscape and Urban Planning, 31(1–3), 21–37. doi: 10.1016/0169-2046(94)01033-5

- Jakab, G. (Ed.). (2012). A Körös-Maros Nemzeti Park növényvilága. Szarvas: Körös-Maros Nemzeti Park Igazgatóság.

- Kertész, É. (2003). A Biharugrai Tájvédelmi Körzet tájtörténeti, florisztikai és cönológiai jellemzése. A Békés Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei, 24–25, 11–40.

- Kleijn, D., & Sutherland, W. J. (2003). How effective are European agri-environment schemes in conserving and promoting biodiversity? Journal of Applied Ecology, 40, 947–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2003.00868.x

- Lastrucci, L., Landi, M., & Angiolini, C. (2010). Vegetation analysis on wetlands in a Tuscan agricultural landscape (Central Italy). Biologia, 65, 54–68. doi: 10.2478/s11756-009-0213-5

- Liu, H.-Y., Lu, X.-G., & Zhang, S.-K. (2004). Landscape biodiversity of wetlands and their changes in 50 years in watersheds of the Sanjiang Plain. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 24(7), 1472–1479.

- Marosi, S., & Somogyi, S. (Eds.). (1990). Magyarország kistájainak katasztere I-II. Budapest: MTA Földrajztudományi Kutató Intézet.

- Nagy, D. (2008). A történeti felszínborítás térképezése. In Z. S. Flachner, A. Kovács, & E. Kelemen (Eds.), A történeti felszínborítás térképezése a Tisza-völgyben. Szemináriumkötet (pp. 7–39). Budapest: SZÖVET.

- Paládi-Kovács, A. (1979). A magyar parasztság rétgazdálkodása. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Pásztor, L., Bakacsi, Z. S., & Szabó, J. (2008). A történelmi földhasználat térképezése a Digitális Kreybig Talajinformációs Rendszer alapján. In Z. S. Flachner, A. Kovács, & E. Kelemen (Eds.), A történeti felszínborítás térképezése a Tisza-völgyben. Szemináriumkötet (pp. 72–74). Budapest: SZÖVET.

- Rakonczai, J. (Ed.). (2011). Környezeti változások az Alföldön. A Nagyalföld Alapítvány kötetei 7. Békéscsaba.

- Stefanovits, P., Filep, G. Y., & Füleky, G. Y. (1999). Talajtan. Budapest: Mezőgazda Kiadó. 472 p.

- Sümegi, P. (2003). Early neolithic man and riparian environment in the Carpathian Basin. In E. Jerem & P. Raczky (Eds.), (2011) Morgenrot der Kulturen. Frühe Etappen der Menschheitgeschichte in Mittel- und Südosteuropa. Festschrift für Nándor Kalicz zum 75 Geburtstag (pp. 53–60). Budapest: Archaeolingua Alapítvány és Kiadó.

- Sümegi, P. (2004). Findings of geoarcheological and environmental historical investigations at the Körös site of Tiszapüspöki-Karancspart Háromága. Antaeus: Communicationes Ex Instituto Archaeologico Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 27, 307–342.

- Sümegi, P. (2011). Az Alföld élővilágának fejlődése a jégkor végétől napjainkig. In J. Rakonczai (Ed.), Környezeti változások az Alföldön. A Nagyalföld Alapítvány kötetei 7 (pp. 35–44). Békéscsaba: Nagyalföld Alapítvány.

- Szűcs, S. (1977). Régi magyar vízivilág. Budapest: Magvető Kiadó.

- Tamisier, A., & Grillas, P. (1994). A review of habitat changes in the Camargue: An assessment of the effect of the loss of biological diversity on the wintering waterfowl community. Biological Conservation, 70, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(94)90297-6

- Tardy, J. (2007). A magyarországi vadvizek világa. Hazánk Ramsari-területei. Budapest: Alaexandra Kiadó.

- Tilman, D., Cassman, K. G., Matson, P. A., Naylor, R., & Polasky, S. (2002). Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature, 418, 671–677. doi: 10.1038/nature01014

- Tímár, G., Molnár, G., Székely, B., Biszak, S., & Jankó, A. (Eds.). (2008). Topographic maps of Hungary in the period of the WWII, 1:50000. Budapest: MD Military History Institute and Museum, Arcanum Adatbázis Ltd.

- Tímár, G., Molnár, G., Székely, B., Biszak, S., Varga, J., & Jankó, A. (Eds.). (2006). Königreich Ungarn – The Second Military Survey (1806–1869), digitized maps of the Habsburg Empire [DVD–ROM]. Budapest: MD Military History Institute and Museum, Arcanum Adatbázis Ltd.

- Tscharntke, T., Klein, A. M., Kruess, A., Steffan-Dewenter, I., & Thies, C. (2005). Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity – Ecosystem service management. Ecology Letters, 8, 857–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00782.x

- Van Der Nat, D., Tockner, K., Edwards, P. J., Ward, J. V., & Gurnell, A. M. (2003). Habitat change in braided flood plains (Tagliamento, NE Italy). Freshwater Biology, 48, 1799–1812. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01126.x

- Willis, K. J. (2007). Impact of the early Neolithic Körös culture on the landscape: Evidence from palaeoecological investigations of Kiri-tó. In A. Whittle (Ed.), The early Neolithic on the Great Hungarian Plain: Investigations of the Körös Culture site of Ecsegfalva 23. Co. Békés: Varia Archaeologica Hungarica (Vol. 21, pp. 83–99). Budapest: AKAPRINT Nyomdaipari Kft.