Abstract

The island of Elba (Tuscan Archipelago, Italy) Natura 2000 habitat map (1:25,000) and the CORINE Biotopes habitat map (1:25,000) were derived from the phytosociological map of Elba integrated with recent studies and field knowledge of the vegetation units. Conventional geographical information system queries were used to manage and select the spatial information. For each map polygon, the following attributes were assigned: (i) habitat typology and (ii) percentage cover of each habitat type. Where multiple habitat types were associated with the same polygon, the percentage cover of each habitat type was estimated. A total of 27 Natura 2000 habitat types and 58 CORINE Biotopes habitat types were identified, these being distributed in single and/or multiple typological units. Distribution and covers of the different habitat types are discussed. The usefulness of this kind of map for monitoring and managing conservation actions is discussed.

1. Introduction

The term habitat, although widely used, is ambiguous because it has been developed with contrasting meanings in different contexts (CitationBunce et al., 2008, Citation2012, Citation2013; CitationDennis, Shreeve, & Van Dyck, 2003; CitationHall, Krausman, & Morrison, 1997, etc.). Its use is thus potentially confusing making it difficult to apply. Despite this, for the pragmatic definition given in the European Directives (CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006, Citation2010), habitats remain a central pillar of European nature conservation policy. This is because the maintenance of a series of habitats in good condition is considered to be one of the best ways to conserve species (CitationBunce et al., 2013).

According to the European Directives, the field identification of a habitat is based on matching it to one (or more) vegetation types (CitationBiondi et al., 2012; CitationBiondi, Casavecchia, & Pesaresi, 2010; CitationBunce et al., 2013; CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006; CitationRodwell et al., 2002; CitationViciani, Lastrucci, Dell'Olmo, Ferretti, & Foggi, 2014a). For this reason, several national vegetation-mapping and data-archiving projects are currently being carried out (e.g. CitationBonis & Bouzillé, 2012; CitationDimopoulos et al., 2012; CitationFont, Pérez-García, Biurrun, Fernández-González, & Lence, 2012). Some of these are related to national habitat mapping projects (e.g. CitationIchter, Savio, Evans, & Poncet, 2012). In Italy, a similar project ‘VegItaly’ has been initiated (CitationGigante et al., 2012; CitationLanducci et al., 2012), but it is far from complete in many regions, with Tuscany being one of the regions in which work is ongoing (CitationViciani et al., 2014a). The Tuscan Regional Administration has not yet commenced a comprehensive vegetation-mapping project, either for the whole territory or areas that might reasonably be considered part of the essential support framework for active in situ conservation (i.e. the Natura 2000 sites). Accurate habitat mapping is an important tool in conservation (CitationAsensi & Díez-Garretas, 2007; CitationBiondi et al., 2007; CitationLoidi, Ortega, & Orrantia, 2007; CitationPavone et al., 2007) and especially so in areas considered hot spots of biodiversity, such as in the Mediterranean basin (CitationMédail & Quézel, 1999; CitationMyers, Mittermeier, & Mittermeier, 2000). The aim of this study is to develop a habitat map for the Mediterranean island of Elba, which forms part of the Tuscan Archipelago in central Italy. The study is based on existing knowledge of the phytosociological vegetation units.

2. The study area

Elba is situated in the Mediterranean biogeographic region (http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/biogeographical-regions-in-europe-1) and is the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago; it is located between Corse and Tuscany, about 10 km offshore from the Piombino promontory (). It has an area of about 223 km2 and a coastline of 147 km, which alternates between beaches and rocky headlands, with both gentle slopes and sheer cliffs. It has a varied orography, with mount Capanne (1018 m asl) being the highest point. Elba also has a complex geological history and structure, with prevalence of Neogene and Quaternary magmatic rocks in the western areas and of marls, limestones, shales, ophiolites and metamorphic rocks in central and eastern areas (CitationCarmignani & Lazzarotto, 2004). The climate is typically Mediterranean, with a primary maximum of precipitation in autumn, a second maximum in winter and a main minimum in summer (CitationFoggi et al., 2006a). The island as a whole is part of the Mediterranean macrobioclimate, pluviseasonal-oceanic bioclimate (CitationBlasi, 2010a), but some locally different bioclimatic subareas can be identified (CitationFoggi et al., 2006a).

The landscape is dominated by a typical Mediterranean sclerophyllous – evergreen forest and by its degradation stages, such as high and low matorrals, garrigues and discontinuous ephemeral grasslands (CitationFoggi et al., 2006a). More than half of the island surface is part of the Tuscan Archipelago National Park; this territory hosts Sites of Community Importance and Special Protection Areas of great relevance for biodiversity conservation. Over the last 50 years the island was involved in a transition from an economy based largely on agricultural exploitation to one based on tourism development, determining a substantial shift in land use.

3. Methods

All the cartographic and phytosociological information available for Elba was interpreted on the basis of field knowledge. This resource was mainly CitationFoggi et al. (2006a, Citation2006b) and CitationCarta (2009), but also included preliminary habitat maps (CitationViciani et al., 2012), studies on vegetation series by CitationBlasi (2010a, Citation2010b), CitationViciani, Lastrucci, Geri, and Foggi (2014b) and some older studies, such as CitationVagge and Biondi (1999) and CitationBiondi, Vagge, and Mossa (2000).

The vegetation survey by CitationFoggi et al. (2006a, Citation2006b) was carried out on the Island during the period 2000–2006 adopting the phytosociological method (CitationBiondi, 2011; CitationBraun-Blanquet, 1964). Over 400 phytosociological relevés were surveyed and analysed across the whole island, leading to the identification of 64 vegetation types (of various syntaxonomical ranks) (CitationFoggi et al., 2006a). The interpretation of aerial georeferenced orthophotos, according to the ‘Photo-guided method’ (CitationKüchler & Zonneveld, 1988; CitationZonneveld, 1979) together with the study of the spatial distribution of vegetation types (recognised in the field on both physiognomical and phytosociological bases), allowed the identification of vegetation types at a scale of 1:10,000. Using this information, the island's vegetation map (1:25,000) was drawn up. This comprised units both of natural and semi-natural vegetation as well as of land use (for further details on the vegetation-mapping method, see CitationFoggi et al., 2006a). The vegetation map includes a total of 71 typologies (CitationFoggi et al., 2006b). In addition, new data on the previously poorly known, annual hygrophytic vegetation of Isoëto-Nanojuncetea class on Elba were published by CitationCarta (2009). All these vegetation data were taken into account to build the habitat maps.

Information used to interpret the habitat types was derived from European Commission (EC) documents and from the literature (CitationAngelini, Bianco, Cardillo, Francescato, & Oriolo, 2009; CitationBiondi & Blasi, 2009; CitationBiondi et al., 2010, Citation2012; CitationCommission of the European Community, 1991; CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006, Citation2010). The map of conservation-interest habitats (sensu 92/43 EC Directive, Natura 2000) was created using a geographical information system (GIS). The correspondence between the available syntaxonomical information and the mapped Natura 2000 habitat types is reported in Table S1. After this, the map of all the habitats sensu CORINE Biotopes was developed and the related geo-database created. The correspondence between the syntaxonomical/land-use information and the mapped CORINE Biotopes habitat types is reported in Table S2.

To extract and select the information used, conventional GIS queries have been employed. The following attributes were assigned to each map polygon: (i) habitat typology, (ii) percentage cover occupied by each habitat type. Where more than one habitat type co-occurred within the same polygon without being possible to separate them (very small and very fragmented units), we used the ‘mosaic’ concept. In such cases the relative percentage cover of the habitat types constituting the mosaic was estimated on the basis of professional and scientific experience acquired while conducting the field relevés. The equivalent area occupied by each habitat type was then calculated. The minimum mapping unit was assumed to be 2000 m2. Habitat types covering polygons smaller than 2000 m2 were treated as points. Both the Natura 2000 habitat map and the CORINE Biotopes map were produced at 1:25,000.

4. Results and discussion

A total of 27 Natura 2000 habitat types were identified, distributed in single and/or multiple typological units (). A Natura 2000 habitat map of Elba was produced (Main Map).

Table 1. Natura 2000 habitat types for the island of Elba, with surface areas (ha) and cover percentages, with respect to the total area covered by Natura 2000 habitats.

The map of all habitats sensu CORINE Biotopes, covering all of Elba, was produced subsequently (Main Map). As expected, the CORINE Biotopes habitat list was more complex with 58 different typologies detected (). Only two vegetation types had surfaces too small to be mapped (just a few squares metres). These cases were treated as point habitats and were marked on the maps as simple points (see map).

Table 2. CORINE Biotopes habitat types for the island of Elba, with surface areas (ha) and cover percentages with respect to the entire Elba land area.

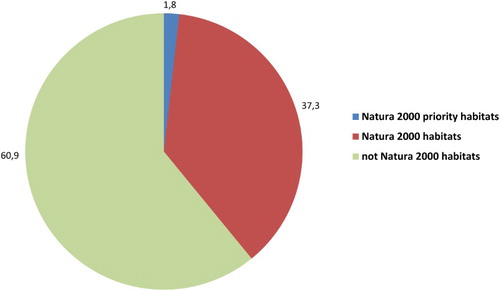

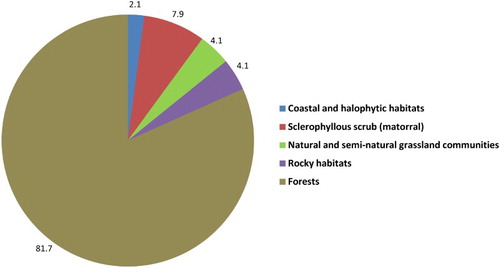

The Natura 2000 habitats cover almost 40% of the total land area of Elba, and have a total area of about 8700 ha. Four priority habitat types cover about 1.8% (, ) but only three were large enough to be mapped as polygons (coastal dunes with Juniperus spp., pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea and alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior, codes 2250, 6220 and 91E0, respectively). It is noted that the two punctual habitats are also of high conservation relevance. They correspond to dwarf amphibious Mediterranean vegetation and belong partly to priority European interest habitats as listed in Annex I of the EU Habitats Directive. As shown in , the main Natura 2000 habitats represented were forests, followed by sclerophyllous matorrals and then the other typologies. Within these forest habitats, the woods dominated by Quercus ilex and Mediterranean pines are by far the most widespread typologies and represent more than 80% of the total cover of the island Natura 2000 habitat types (, ). Natura 2000 matorral habitats and natural and semi-natural grassland communities do not reach high percentages but are nevertheless widespread throughout Elba. The rocky habitats are concentrated mainly on two sites – Mt Capanne and Mt Volterraio. Coastal and halophytic Natura 2000 habitats appear to be about 2% in cover. They are well-represented only by the habitat code 1240 (vegetated cliffs with Limonium spp.), while dune habitats cover only 0.02%, due both to the island's geomorphology and also to the intense pressure of tourism on the larger sandy beaches. As mentioned above, freshwater habitats of dwarf amphibious Mediterranean vegetation (Natura 2000 codes 3120 and 3170) are present but without significant cover values, as is often the case in the Mediterranean area (CitationGrillas, Gauthier, Yavercovski, & Perennou, 2004).

Figure 3. Cover percentages of Natura 2000 habitats on Elba with respect to the total area covered by Natura 2000 habitats, grouped into broad environmental typologies.

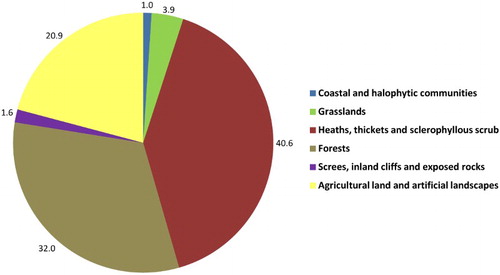

The mapping of CORINE Biotopes habitat types was more complex (), also because CORINE Biotopes typologies were allowed to cover the entire land area of the island. Some typologies correspond exactly to Natura 2000 habitats (e.g. saltmarsh scrubs, Juniperus phoenicea s.l. arborescent matorral, cork-oak forests), others are defined more precisely (e.g. Mediterranean pine forests, grouped under a single Natura 2000 code but separated in the CORINE Biotopes legend, according to the dominant species). Many others are not included in the Natura 2000 list, even though they often correspond to natural and semi-natural habitat types (e.g. several high and low maquis typologies). The percentage subdivision into broad environmental typologies is shown in . Forests cover about 32% of Elba in total land area. This high percentage is interesting for a Mediterranean island inhabited and exploited for thousands of years, and differentiates Elba from other islands of the Tuscan Archipelago, where wooded areas are extremely reduced: examples are on the islands of Capraia (CitationFoggi & Grigioni, 1999), Giannutri (CitationFoggi et al., 2011), and some other islands in the Mediterranean (CitationBartolo, Brullo, Minissale, & Spampinato, 1988). Agricultural land and artificial landscapes (urban areas included, see CORINE Biotopes Manual, CitationCommission of the European Community, 1991) cover about 21% of the area. This value is higher than on other islands of the Tuscan Archipelago (see CitationFoggi et al., 2011; CitationFoggi, Cartei, & Pignotti, 2008; CitationFoggi & Grigioni, 1999; CitationFoggi & Pancioli, 2008; CitationViciani, Albanesi, Dell'Olmo, & Foggi, 2011) and is testimony to the intense human presence on the island. It is worth noting that on Elba (as on many Mediterranean islands) heaths, thickets and sclerophyllous scrubs comprise the largest CORINE Biotopes comprehensive typology (more than 40%, see ), while they represent only about 8% in the cover of Natura 2000 habitat types. This has also been reported for other Mediterranean areas (see CitationPasta & La Mantia, 2009).

5. Conclusions

An accurate phytosociological vegetation map involves a number of activities from several points of view (e.g. a large amount of fieldwork, plant identification, creation of databases, statistical analyses and syntaxonomical checks). Even though some authors (see e.g. CitationChiarucci, 2007) suggest that all this work is not always adequately rewarded in terms of scientific impact, it is nevertheless often useful for a range of purposes. In particular, an important role of phytosociology relates to the identification of habitats deserving the highest conservation effort (see CitationBiondi et al., 2012). Therefore, the availability of cartographic documentation based on phytosociological data allows documents to be derived such as the mapping of habitats of conservation interest or of Corine habitats that are important tools for the management and planning of actions to protect the territory. Moreover, the detection of habitats and species listed as being of Community interest is crucial to the designation of Sites of Community Interest (SCI) by the Member States as stated in the Habitats Directive (CitationCommission of the European Communities, 1992). Furthermore, where there is an obligation on behalf of the Member State to guarantee a Favourable Conservation Status, with requirements for monitoring and reporting, at least for the habitats and species for which the SCI has been designated (CitationOstermann, 1998), Natura 2000 habitat maps represent an extremely valuable tool for gaining new knowledge and for monitoring habitats in the SCIs. This is particularly true nowadays, as the attention of conservationists is increasingly being focused on evaluating not only species but also communities (e.g. habitats, biotopes, ecosystems and ecological communities, see CitationGigante, Buffa, Foggi, Venanzoni, & Viciani, 2013; CitationKeith et al., 2013; CitationKontula & Raunio, 2009; CitationNicholson, Keith, & Wilcove, 2009; CitationRodriguez et al., 2011, Citation2012; CitationRodwell, Janssen, Gubbay, & Schaminée, 2013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Software

The maps were created and edited using the Esri ArcGIS 9.2.

Table_S1_Correlazione_Syntaxa_Habitat_N2000_1.xlsx

Download MS Excel (14.7 KB)Table_S2_Correlazione_Syntaxa_Habitat_CORINE.xlsx

Download MS Excel (20.4 KB)HABITAT MAP (NATURA 2000 Classification) Scale 1:25,000 - ELBA ISLAND

Download PDF (13.3 MB)ORCID

Daniele Viciani http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-5999

References

- Angelini, P., Bianco, P., Cardillo, A., Francescato, C., & Oriolo, G. (2009). Gli habitat in Carta della Natura. Roma: Dipart Difesa della Natura, ISPRA.

- Asensi, A., & Díaz-Garretas, B. (2007). Cartografía de los hábitat naturales y seminaturales en el Parque natural del Estrecho (Cádiz, España). Estado de conservación. Fitosociologia, 44(2), 17–22.

- Bartolo, G., Brullo, S., Minissale, E., & Spampinato, G. (1988). Flora e vegetazione dell'Isola di Lampedusa. Bollettino Accademia Gioenia Scienze Naturali di Catania, 21, 119–255.

- Biondi, E. (2011). Phytosociology today: Methodological and conceptual evolution. Plant Biosystems – An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology, 145(supplement 1), 19–29. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2011.602748

- Biondi, E., & Blasi, C. (2009). Manuale italiano di interpretazione degli Habitat della Direttiva 92/43/CEE. Retrieved September 15, 2014, from http://vnr.unipg.it/habitat/

- Biondi, E., Burrascano, S., Casavecchia, S., Copiz, R., Del Vico, E., Galdenzi, D., … Blasi, C. (2012). Diagnosis and syntaxonomic interpretation of Annex I Habitats (Dir. 92/43/EEC) in Italy at the alliance level. Plant Sociology, 49(1), 5–37.

- Biondi, E., Casavecchia, S., & Pesaresi, S. (2010). Interpretation and management of the forest habitats of the Italian peninsula. Acta Botanica Gallica, 157(4), 687–719. doi: 10.1080/12538078.2010.10516242

- Biondi, E., Catorci, A., Pandolfi, M., Casavecchia, S., Pesaresi, S., Galassi, S., … Zabaglia, C. (2007). Il Progetto di “Rete Ecologica della Regione Marche” (REM): per il monitoraggio e la gestione dei siti Natura 2000 e l'organizzazione in rete delle aree di maggiore naturalità. Fitosociologia, 44(2), 89–93.

- Biondi, E., Vagge, I., & Mossa, L. (2000). On the phytosociological importance of Anthyllis barba-jovis L. Colloques Phytosociologiques, 27, 95–104.

- Blasi, C. (ed.). (2010a). La vegetazione d'Italia. Roma: Palombi & Partner srl.

- Blasi, C. (ed.). (2010b). La vegetazione d'Italia. Carta delle Serie di Vegetazione, scala 1:500000. Roma: Palombi & Partner srl.

- Bonis, A., & Bouzillé, J.-B. (2012). The project VegFrance: Towards a national vegetation database for France. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 97–99.

- Braun-Blanquet, J. (1964). Pflanzensoziologie. Wien: Springer Verlag.

- Bunce, R. G. H., Bogers, M. M. B., Evans, D., Halada, L., Jongman, R. H. G., Mücher, C. A., … Olsvig-Whittaker, L. (2013). The significance of habitats as indicators of biodiversity and their links to species. Ecological Indicators, 33, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.07.014

- Bunce, R. G. H., Bogers, M. M. B., Ortega, M., Morton, D., Allard, A., Prinz, M., … Jongman, R. H. G. (2012). Conversion of European habitat data sources into common standards (Alterra Report 2277). Wageningen.

- Bunce, R. G. H., Metzger, M. J., Jongman, R. H. G., Brandt, J. J., De Blust, G., Elena-Rossello, R., … Wrbka, T. (2008). A standardized procedure for surveillance and monitoring European habitats and provision of spatial data. Landscape Ecology, 23, 11–25. doi: 10.1007/s10980-007-9173-8

- Carmignani, L., & Lazzarotto, A. (2004). Carta geologica della Toscana (scala 1:250.000). Firenze: Università di Siena.

- Carta, A. (2009). Contributo alla conoscenza della classe Isoëto-Nanojuncetea dell'Isola d'Elba (Arcipelago Toscano – Livorno). Atti Società toscana di Scienze naturali, Memorie, Serie B, 115(2008), 35–42. Retrieved from http://www.stsn.it/images/pdf/serB115/05_carta.pdf

- Chiarucci, A. (2007). To sample or not to sample? That is the question – for the vegetation Scientist. Folia Geobotanica, 42, 209–216. doi: 10.1007/BF02893887

- Commission of the European Community. (1991). CORINE biotopes manual – Habitats of the European Community. Luxembourg: DG Environment, Nuclear Safety and Civil Protection.

- Commission of the European Communities. (1992). Council directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Official Journal L206. Retrieved July 22, 1992 (Consolidated version 1.1.2007).

- Dennis, R. L. H., Shreeve, T. G., & Van Dyck, H. (2003). Towards a functional resource-based concept for habitat: a butterfly biology viewpoint. Oikos, 102(2), 417–426. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12387.x

- Dimopoulos, P., Tsiripidis, I., Bergmeier, E., Fotiadis, G., Theodoropoulos, K., Raus, T., … Mucina, L. (2012). Towards the Hellenic national vegetation database: VegHellas. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 81–87.

- Evans, D. (2006). The habitats of the European union habitats directive. Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 106(3), 167–173.

- Evans, D. (2010). Interpreting the habitats of Annex I. Past, present and future. Acta Botanica Gallica, 157(4), 677–686. doi: 10.1080/12538078.2010.10516241

- European Commission. (2013). Interpretation manual of European union habitats, vers. EUR28. Brussel: European Commission, DG Environment.

- Foggi, B., Cartei, L., & Pignotti, L. (2008). La vegetazione dell'Isola di Pianosa (Arcipelago Toscano, Livorno). Braun-Blanquetia, 43, 1–41.

- Foggi, B., Cartei, L., Pignotti, L., Signorini, M. A., Viciani, D., Dell'Olmo, L., & Menicagli, E. (2006a). Il paesaggio vegetale dell'Isola d'Elba (Arcipelago Toscano). Studio di fitosociologia e cartografico. Fitosociologia, 43(1), Suppl. 1, 3–95. Retrieved from http://www.scienzadellavegetazione.it/sisv/documenti/Articolo/pdf/121.pdf

- Foggi, B., Cartei, L., Pignotti, L., Signorini, M. A., Viciani, D., & Dell'Olmo, L. (2006b). Carta della vegetazione dell'Isola d'Elba (Arcipelago Toscano). Scala 1:25.000. Ente Parco Nazionale Arcipelago Toscano, Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio, Università degli Studi di Firenze. Retrieved from https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/15732686/CARTAVEG_ELBA.pdf

- Foggi, B., Cioffi, V., Ferretti, G., Dell'Olmo, L., Viciani, D., & Lastrucci, L. (2011). La vegetazione dell'Isola di Giannutri (Arcipelago Toscano, Livorno). Fitosociologia, 48(2), 23–44.

- Foggi, B., & Grigioni, A. (1999). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell'isola di Capraia. Parlatorea, 3, 5–33.

- Foggi, B., and Pancioli, V. (2008). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell'Isola del Giglio (Arcipelago Toscano, Toscana meridionale). Webbia, 63(1), 25–48. doi: 10.1080/00837792.2008.10670831

- Font, X., Pérez-García, N., Biurrun, F., Fernández-González, F., & Lence, C. (2012). The Iberian and Macaronesian vegetation information system (SIVM), five years of online vegetation's data publishing. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 89–95.

- Gigante, D., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Attorre, F., Cambria, V. E., Casavecchia, S., … Venanzoni, R. (2012). VegItaly: Technical features, crucial issues and some solutions. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 71–79.

- Gigante, D., Buffa, G., Foggi, B., Venanzoni, R., & Viciani, D. (2013). Crucial points for a habitat red list in Italy. 22nd European Vegetation Survey International Workshop, Rome (Italy) 9–11 April 2013. Book of abstracts, pp. 14–15.

- Grillas, P., Gauthier, P., Yavercovski, N., & Perennou, C. (Eds). (2004). Mediterranean temporary pools. Arles: Station biologique de la Tour du Valat.

- Hall, L. S., Krausman, P. R., & Morrison, M. L. (1997). The habitat concept and a plea for standard terminology. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 25, 173–182.

- Ichter, J., Savio, L., Evans, D., & Poncet, L. (2012). State-of-the-art of vegetation mapping in Europe: Results of a European survey and contribution to the French program CarHAB. International Conference “Vegetation mapping in Europe”, 17–19 October 2012, Saint-Mandé (94), France. Abstract book, p. 18.

- Keith, D. A., Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Nicholson, E., Aapala, K., Alonso, A., … Zambrano-Martínez, S. (2013). Scientific foundations for an IUCN red list of ecosystems. PLoS ONE, 8(5), e62111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062111

- Kontula, T., & Raunio, A. (2009). New method and criteria for national assessments of threatened habitat types. Biodiversity and Conservation, 18, 3861–3876. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9684-5

- Küchler, A. W., & Zonneveld, I. S. (1988). Vegetation mapping. Handbook of Vegetation Science, 10. Dordrecht: Kluwer academic publisher.

- Landucci, F., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Attorre, F., Biondi, E., Cambria, V. E., … Venanzoni, R. (2012). VegItaly: The Italian collaborative project for a national vegetation database. Plant Biosystems – An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology, 146(4), 756–763. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2012.740093

- Loidi, J., Ortega, M., & Orrantia, O. (2007). Vegetation science and the implementation of the habitat directive in Spain: Up-to-now experiences and further development to provide tools for management. Fitosociologia, 44(2), 9–16.

- Médail, F., & Quézel, P. (1999). Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: Setting global conservation priorities. Conservation Biology, 13, 1510–1513. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98467.x

- Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., & Mittermeier, C. G. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

- Nicholson, E., Keith, D. A., & Wilcove, D. S. (2009). Assessing the threat status of ecological communities. Conservation Biology, 23(2), 259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01158.x

- Ostermann, O. P. (1998). The need for management of nature conservation sites designated under Natura 2000. Journal of Applied Ecology, 35, 968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.1998.tb00016.x

- Pasta, S., & La Mantia, T. (2009). La Direttiva 92/43/Cee ed il patrimonio agro-forestale, pre-forestale e forestale siciliano: alcune note critiche. Naturalista siciliano. S. IV, 33(3–4), 315–328.

- Pavone, P., Spampinato, G., Tomaselli, V., Minissale, P., Costa, R., Sciandrello, V., & Ronsisvalle, F. (2007). Cartografia degli habitat della Direttiva CEE 92/43 nei biotopi della Provincia di Siracusa (Sicilia orientale). Fitosociologia, 44(2), 183–193.

- Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Baillie, J. E. M., Ash, N., Benson, J., Boucher, T., … Zamin, T. (2011). Establishing IUCN red list criteria for threatened ecosystems. Conservation Biology, 25(1), 21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01598.x

- Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Keith, D. A., Barrow, E. G., Benson, J., Nicholson, E., & Wit, P. (2012). IUCN red list of ecosystems. SAPIENS, 5(2), 60–70.

- Rodwell, J. S., Janssen, J., Gubbay, S., & Schaminée, J. (2013). Red list assessment of European habitat types. A feasibility study (Report for the European Commission). Alterra: Wageningen and European Commission, DG Environment.

- Rodwell, J. S., Schaminée, J. H. J., Mucina, L., Pignatti, S., Dring, J., & Moss, D. (2002). The diversity of European vegetation. An overview of phytosociological alliances and their relationships to EUNIS habitats. Ministry of Agriculture Nature Management and Fisheries. The Netherlands and European Environmental Agency.

- Vagge, I., & Biondi, E. (1999). La vegetazione delle coste sabbiose del Tirreno settentrionale. Fitosociologia, 36(2), 61–96.

- Viciani, D., Albanesi, D., Dell'Olmo, L., & Foggi, B. (2011). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell'Isola di Gorgona (Arcipelago Toscano) (con carta in scala 1: 5.000). Fitosociologia, 48(2), 45–64.

- Viciani, D., Dell'Olmo, L., Ferretti, G., Lazzaro, L., Lastrucci, L., & Foggi, B. (2012). Phytosociological vegetation mapping and habitat detection: The example of Elba Island (Tuscan Archipelago, Italy). International Conference “Vegetation mapping in Europe”, 17–19 October 2012, Saint-Mandé (94), France. Abstract Book, p. 81.

- Viciani, D., Lastrucci, L., Dell'Olmo, L., Ferretti, G., & Foggi, B. (2014a). Natura 2000 habitats in Tuscany (central Italy): Synthesis of main conservation features based on a comprehensive database. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23, 1551–1576. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0686-6

- Viciani, D., Lastrucci, L., Geri, F., & Foggi, B. (2014b). Gap analysis comparing protected areas with potential natural vegetation in Tuscany (Italy) and a GIS procedure to bridge the gaps. Plant Biosystems. doi:10.1080/11263504.2014.950623

- Zonneveld, I. S. (1979). Land evaluation and land(scape) science. Use of aerial photographs in geography and geomorphology. ITC textbook of photointerpretation, Volume VII, ITC.