ABSTRACT

The terracing of vineyards has been a centuries-old traditional land use type in the Tokaj-Hegyalja region (887 km2). However, most of them have since been abandoned and are occupied by dense vegetation. In this study, we mapped the spatial extent of vineyard terraces, based on aerial photos. We classified the terraced fields, considering their topographic characteristics as assessed by topographic factors (slope, exposure and elevation) and the process of abandonment between 1784 and 2010 using historical and contemporary land use maps. Based on the overall map of vineyard abandonment (scale: 1:120,000), the process of the abandonment of terraces can be divided into six consecutive time intervals (1784–1858, 1858–1884, 1884–1940, 1940–1969, 1969–1989 and 1989–2010). Vineyard terraces were found on 590 ha, which were concentrated on hillsides steeper than 17%, on southwestern, southern and southeastern exposures, and lying between 150 and 500 m a.s.l. In the period between 1884 and 1989, 77.8% of the terraces were abandoned, with a particularly intense period of abandonment between 1940 and 1969, which saw a 31.1% decrease in the extent of cultivated terraces.

1. Introduction

Terraced landscapes occur widely all over the world, from the rice terraces of China to the arable lands of Peru (CitationPetit, Konold, & Höchtl, 2012). In Europe, and also in Hungary, terraces were built primarily for vine cultivation. Vineyards represent one of the most extensive of the agro-ecosystems which cover the mountainous and hilly areas of temperate climate regions (CitationStanchi et al., 2013; CitationTarolli, Preti, & Romano, 2014). Viticulture has a tradition stretching back hundreds of years in Hungary, and this is also the case in the Tokaj-Hegyalja region (CitationBalassa, 1991). The vineyard terraces with retaining walls show a close interaction between nature and human beings, resulting in the creation of unique cultural and aesthetic values which have become part of the cultural heritage of the country (CitationNyizsalovszki & Fórián, 2007; CitationTóth, Endrődi, & Horváth, 2014). The first use of terracing in Central Europe is presumed to have occurred between the tenth and the thirteenth centuries (CitationPetit et al., 2012), while in Hungary the first written evidence comes from the seventeenth century (CitationBalassa, 1991). In spite of being mentioned in written documents, we know of only a very few cases where they appeared in early cartographic materials (CitationAnonymous, 1714; CitationGolenics, 1833; CitationSárospataky, 1789).

Their illustration in historic or contemporary maps was not considered relevant, and only a few maps of landlords’ estates from the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries represent exceptions to this rule within our study area; in these cases, the maps featured symbols representing retaining walls, or sometimes a written indication, for example, ‘stone retainer’ and ‘deteriorated stone retainer’ (CitationAnonymous, 1714; CitationNovák & Incze, 2014). On modern topography maps, vineyard terraces are marked by gaps in contour lines and by notation for some stone walls, but their spatial extent are not accurately shown.

Land terracing with retaining walls facilitates cultivation on steeper slopes by decreasing slope angle, retaining more water and reducing soil erosion (CitationLasanta, Arnaez, Oserin, & Ortigosa, 2001). However, because of their high labour-intensity, as well as the high initial and ongoing investment costs, the role of terraces is decreasing (CitationDouglas, Kirkby, Critchley, & Park, 1994; CitationDunjo, Pardini, & Gispert, 2003; CitationKiss, Barta, Sümeghy, & Czinege, 2005). Over the centuries, walls were repaired by labourers, but in the absence of appropriate management or after the abandonment of terraces, soil erosion and slope failures can occur (CitationLesschen, Cammeraat, & Nieman, 2008; CitationNovák & Incze, 2014; CitationRuecker, Schad, Alcubilla, & Ferrer, 1998). Due to secondary succession on terraces (CitationNovák, Incze, Spohn, Glina, & Giani, 2014), the process of degradation slows down, but the aesthetic value of the landscape is reduced, particularly by the expansion of scrubland on abandoned areas (CitationAntrop, 2003). According to CitationAngelstam, Boresjö-Bronge, Mikusiński, Sporrong, and Wästfelt (2003), cultural landscapes are at risk of disappearing due to land abandonment and, as CitationTarolli et al. (2014) have noted, terraced vineyards are among the most endangered landscapes in Europe. The reasons for the collapse of terraces in the Mediterranean region are well explored (CitationLasanta et al., 2001; CitationLesschen et al., 2008); however, the destruction of terraced areas is also an important cultural and aesthetic issue in the Central European region (CitationMojses & Petrovič, 2013; CitationNyizsalovszki & Fórián, 2007), and therefore special attention should be paid to their protection. CitationCyffka and Bock (2008) highlighted the importance of establishing the historical state of landscapes as a way of understanding changes over time, an essential step in beginning the planning process.

Our aims are to identify the extent of vineyard terraces in the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region, to show their topographic characteristics, based on three topographic factors (slope angle, exposure and elevation) and to analyse the land abandonment process occurring between 1784 and 2010.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

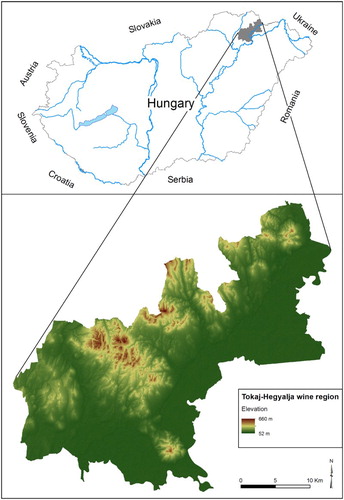

Tokaj-Hegyalja () is one of the most famous wine regions of Hungary. This historic vine producing area is located in the foothills of the Zemplén Mountain between the latitudes of 48.05° and 48.24° and includes 27 settlements. Although the border of the study area has changed over the centuries, in this paper we analyse its present-day area (887 km2).

The hills of Tokaj-Hegyalja consist of andesite, dacite, riolite and their tuffs from the Miocene, which were covered by aeolian loess in the late glacial periods (CitationPinczés, 1969). The study area is dissected by lower mountain ridges and erosional valleys, resulting in a great diversity of microclimatic characteristics within the region (CitationNyizsalovszki & Fórián, 2007). In Europe, viticulture is economically viable between the latitudes of 30° and 50° and as Tokaj-Hegyalja is close to the northern edge of this zone, it is highly sensitive to climatic changes (CitationNyizsalovszki & Fórián, 2007).

In 2002, Tokaj-Hegyalja was declared a UNESCO World Heritage area in the cultural landscape category due to its traditional viticulture and the interaction between nature and human beings (CitationNyizsalovszki & Fórián, 2007).

2.2. Methods applied

2.2.1. Identification of terraced vineyards

The spatial presence of vineyard terraces with retaining walls was mapped on aerial photos which were taken in 1952 and 1957. The photos were taken in periods with reduced vegetation, in order to avoid photographing vegetation cover on terraces, which would have made their identification difficult. Aerial photos were georeferenced and transformed into the EOV projection, selecting well-defined fixed points; polygons were then used to cover the areas. The investigation of terraces was supplemented with GPS coordinates recorded during the field trip, where the length, height, width and angle of retaining walls were measured, as well as the length of collapsed sections (CitationIncze & Novák, 2013).

2.2.2. Topographic characteristics of terraced areas

The topographic characteristics of vineyard terraces were assigned using a digital elevation model derived from the contours of a topographic map (date: 1989, scale: 1:10,000). Slope angles were categorised taking the Hungarian agronomy practice into consideration (<5%, 5.1–12%, 12.1–17%, 17.1–25%, 25.1–35%, 35.1–45% and 45.1%<). Exposure was evaluated by assigning the terraced slopes to the four cardinal – north (N), east (E), south (S) and west (W) – and the four intercardinal directions – northeast (NE), southeast (SE), southwest (SW) and northwest (NW). Based on the elevation, terraced slopes were assigned at 50-metre distance intervals (<150, 150.1–200, 200.1–250, 250.1–300, 300.1–350, 350.1–400, 400.1–450, 450.1–500 and 500.1 m< a.s.l.).

The distribution of vineyard terraces in terms of their varying slopes, exposures and elevations can be calculated with the ‘Zonal Statistics as Table’ toolbar of ArcGIS 10 after rasterising polygons using the ‘Polygon to raster’ command.

2.2.3. Analysis of the abandonment of vineyard terraces between 1784 and 2010

To reconstruct long-term changes (CitationSzilassi, 2003; CitationSzilassi & Kiss, 2001) in the study area between 1784 and 2010, historical and contemporary georeferenced maps were used ().

Table 1. Dataset of maps used in the study.

Some of the maps we used (CitationMilitary Surveys I, CitationII, and CitationIII, and Topographic maps from the time of II World War, 1940–1944) were digitally available and provided with a coordinate system, but since their geodetic precision varies from tens to hundreds of metres (CitationKanianska, Kizeková, Novácek, & Zeman, 2014) we decided to transform them again into the EOV projection in order to increase the relative accuracy of the maps in relation to each other. The satellite images of Google maps, 2010 were accessible in the EOV projection thanks to the OpenLayer plugin of QGIS, while 1:25000 scale Topography Maps of Hungary, 1969 were available in printed form, and consequently they were scanned, initially at 600 DPI, before being transformed into the EOV projection. In every case the 1:10 000 scale Topography Maps of Hungary in EOTR projection, 1985–89 was used as the reference map during the georeferencing process.

After georeferencing the maps, vineyards were localised visually and then were digitised manually (polygon) on every map.

With the use of the Update tools of ArcGIS 10, the maps were overlaid on top of each other from the oldest to the newest, resulting in six separate intervals (1784–1858, 1858–1884, 1884–1940, 1940–1969, 1969–1989 and 1989–2010). The given interval shows that the vineyards mapped at the beginning of the period were not identified as vineyards at the end of the period and were therefore abandoned during this time. Finally, the terraced areas were cross-referenced with the map of abandoned vineyards in order to identify the time of abandonment.

3. Results and discussion

Terraced slopes were identified over a 590 ha area, equivalent to 11.3% of the present-day area of vineyards in the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region.

About 574.9 ha (97.7% of the terraced area) were found on hillsides steeper than 17% (), which is in accordance with the usual soil conservation aim, where terracing is recommended on slopes steeper than 12%. The largest area of vineyard terraces occurred on an area with a 25.1–35% slope angle (264.6 ha), followed by hillsides with 35.1–45% (208.3 ha) and 17.1–25% (87.72 ha) slope angles. About 14.3 ha of terraces occurred on hillsides steeper than 45%, while the extent of terraces occurring on slopes under a 17% angle is considered negligible.

In terms of exposure (), 377.7 ha (64.2% of the vineyard terraces) are divided among SW (142.7 ha), S (123.8 ha) and SE (111.2 ha) hillsides. In addition, W (91.6 ha) and E (70.5 ha) exposures can be noted, but the northern slopes accommodate less than 5% of terraces, which confirms the climatological results of CitationJustyák and Tar (1974a, Citation1974b) who investigated the dominant role of southern, western and eastern slopes in vine cultivation.

In terms of elevation, terraces occurred between 150 and 500 m a.s.l. (), where the intervals of 250.1–300 m (226.2 ha), 300.1–350 m (156.7 ha) and 200.1–250 m a.s.l. (122.6 ha) were found to be the most notable, while the other categories did not feature to any great extent.

CitationBoros, Horváth, and Csüllög (2012) noted that up to a height of 250–260 m a.s.l. elevation has a positive effect on the sugar content of grapes, while according to CitationJustyák (1965) a heat surplus can be observed up to a height of 300–350 m a.s.l. on the southern slopes, which explains the location of terraced areas.

The land abandonment process of vineyard terraces () was examined in six consecutive time periods.

The Main Map of vineyard abandonment (scale: 1:120,000) shows that 450.5 ha (77.8% of the terraces) were abandoned between 1884 and 1989. The first substantial abandonment occurred between 1884 and 1940, when 116.3 ha (20.1% of vineyard terraces) were abandoned. In this period, the Phylloxera vastatrix (grape disease) reached the study area (in 1885) and destroyed almost two thirds of the vineyards (CitationBalassa, 1991). The reconstruction (starting at the beginning of twentieth century) progressed slowly, and was further slowed by the First World War (CitationBalassa, 1991).

The largest area was abandoned between 1940 and 1969 (180.1 ha, 31.1%), and then again between 1969 and 1989 (154.1 ha, 26.6%) despite the fact that the extent of vineyards increased significantly during these periods. After the Second World War, Hungary became a member of Comecon and due to the mechanisation of viticulture (CitationKopsidis, 2008) and forced mass production, terraces inaccessible by machines were abandoned. Land abandonment or land use changes in the study area resulting from political decisions were not unique events. This phenomenon is recognisable in the post-socialist countries of Europe, where the collectivisation and mechanisation of agriculture followed by the political transition and the change to a market-oriented economy caused significant land abandonment and land use changes (CitationBaumann et al., 2011; CitationBicik, Jelecek, & Stepanek, 2001; CitationHostert, Kuemmerle, Radeloff, & Müller, 2008; CitationKanianska et al., 2014; CitationKuemmerle et al., 2008; CitationLieskovský et al., 2015; CitationŁowicki, 2008). These processes were considered to be the main driving forces in the abandonment of vineyards in this area, too (CitationDobos, Nagy, & Molek, 2014; CitationLieskovský et al., 2013).

At present, only 2.4% of terraced areas are under cultivation in the Tokaj-Hegyalja region.

4. Conclusion

The study illustrates the importance of historic and contemporary maps (with GIS) in the identification of the extent, the topographic characteristics and the land abandonment process of vineyard terraces in the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region.

Terraced vineyards were found on 590 ha in the study area, 97.7% of which occurred on hillsides steeper than 17%. In terms of exposure, 64.2% of the vineyard terraces were located on SW, S and SE slopes, while in terms of elevation the 250.1–300 m a.s.l. height interval is particularly important.

The process of the abandonment of vineyard terraces was evaluated, based on six consecutive time periods. According to our results, 77.8% of the terraces were abandoned between 1884 and 1989, with the period between 1940 and 1969 being particularly noteworthy.

Although vineyard terraces are part of the world’s cultural heritage, in the absence of appropriate management, their collapse may accelerate soil erosion and slope failures. Therefore, the identification of these terraces contributes to the prevention of potential slope stability problems induced by their collapse, and may facilitate the foundation of an effective strategy for their maintenance.

Software

Erdas 2013 was used for the ortorectification of aerial photos. The transformation of maps to the same projection system (EOV) was carried out with QGIS 2.4, while the investigations of the process of abandonment and the topographic characteristics of vineyard terraces were conducted with ArcGIS 10.

Identification of extent, topographic characteristics and land abandonment process of vineyard terraces in the Tokaj-Hegyalja wine region between 1784 and 2010.pdf

Download PDF (13.2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCiD

József Incze http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5706-9242

Tibor József Novák http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5514-9035

Additional information

Funding

References

- Angelstam, P., Boresjö-Bronge, L., Mikusiński, G., Sporrong, U., & Wästfelt, A. (2003). Assessing village authenticity with satellite images: A method to identify intact cultural landscapes in Europe. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, 32, 594–604.

- Anonymous. (1714). Delineatio vineae Királyhegy dictae in promonthorio Sárospatakiensi existentis, telekrajz. Magyar Országos levéltár, Térképtár, S 82 No 0317, 34 × 19 cm [eredeti jelzet: P 392 Lad. 43. No. 100].

- Antrop, M. (2003). Development of European landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning, 67, 1–8.

- Balassa, I. (1991). Tokaj-Hegyalja szőlője és bora [Vineyards and wine of Tokaj-Hegyalja]. Tokaj-Hegyaljai ÁG: Borkombinát, Tokaj, p. 752 (in Hungarian).

- Baumann, M., Kuemmerle, T., Elbakidze, M., Ozdogan, M., Radeloff, V. C., Keuler, N. S., … Hostert, P. (2011). Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy, 28, 552–562.

- Bicik, I., Jelecek, L., & Stepanek, V. (2001). Land-use changes and their social driving forces in Czechia in the 19th and the 20th centuries. Land Use Policy, 18, 65–73.

- Boros, L., Horváth, G., & Csüllög, G. (2012). Tokaj-Hegyalja szőlő- és borgazdaságának természetföldrajzi alapjai [Physical geography fundamentals of grape and vine economy in Tokaj-Hegyalja]. In Frisnyák-Gál (Ed.), Tokaj-hegyaljai borvidék. Hazánk első történeti tája (pp. 23–40). Debrecen: Nyíregyházi Főiskola Turizmus és Földrajztudományi Intézet (in Hungarian).

- Cyffka, B., & Bock, M. (2008). Degradation of field terraces in the Maltese Islands – Reasons, processes, and effects. Geografia Fisica e Dinammica Quaternaria, 31(2008), 119–128.

- Dobos, A., Nagy, R., & Molek, Á. (2014). Land use change in historic vine region and their connection with optimal land use: A case study of Nagy-Eged Hill, Northern Hungary. Carpathian Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 9(2), 219–230.

- Douglas, T. D., Kirkby, S. J., Critchley, R. W., & Park, G. J. (1994). Agricultural terrace abandonment in the Alpujarra, Andalucia, Spain. Land Degradation and Development, 5, 281–291.

- Dunjo, G., Pardini, G., & Gispert, M. (2003). Land use change effects on abandoned terraced soils in a Mediterranean catchment, NE Spain. Catena, 52, 23–37.

- Golenics, J. (1833). Situs vinearum Kővágó, Hangács et Felbér terreni oppidi Máad & Tállya, Magyar Országos levéltár, Térképtár. S 138 No 0002, 61 × 36 cm, [1:3600] 1˝ = 50°.

- Hostert, P., Kuemmerle, T., Radeloff, V. C., & Müller, D. (2008). Post socialist land-use and land-cover change in the Carpathian Mountains. IHDP Update 2. 70–73.

- Incze, J., & Novák, T. J. (2013). Geomorphological characteristic and significance of dry constructed terrace stone walls on abandoned vine-plantations in Tokaj Big-Hill. In J. Novotny, M. Lehotsky, Z. Raczkowska, & Z. Machova (Eds.), Carpatho-Balkan-Dinaric conference on geomorphology book of abstracts, Geomorphologia Slovaca et Bohemica (Vol. 13, p. 33). Bratislava, Slovak Republic: Institute of Geography SAS.

- Justyák, J. (1965). Terepklímamérések a tokaji Nagy-Kopasz déli lejtőjén [Climate measurements on the southern slope of Tokaj Nagy-Kopasz]. Acta Geographica Universitatis Debreceniensis, 10(3), sz. pp. 27–38. (in Hungarian).

- Justyák, J., & Tar, K. (1974a). Investigation on the ratio of direct and global radiation amounts. Part I: Radiation-ratio on a horizontal surface and on a Southern Slope. Acta Geographica Debrecina, XII, 127–148.

- Justyák, J., & Tar, K. (1974b). Investigation on the ratio of direct and global radiation amounts. Part II: Radiation received by the Western and Eastern Slopes and by the horizontal surface. Acta Geographica Debrecina, XIII, 125–137.

- Kanianska, R., Kizeková, M., Novácek, J., & Zeman, M. (2014). Land-use and land-cover changes in rural areas during different political systems: A case study of Slovakia from 1782 to 2006. Land Use Policy, 36, 554–566.

- Kiss, A., Barta, K., Sümeghy, Z., & Czinege, A. (2005). Historical land use and anthropogenic features: A case study from Nagymaros. Acta Climatologica et Chorologica Universitatis Szegediensis, 38–39, 111–124.

- Kopsidis, M. (2008). Agricultural development and impeded growth: The case of Hungary, 1870–1973. In P. Lains & V. Pinilla (Eds.), Agriculture and economic development in Europe since 1870 (pp. 286–310). Abingdon: Routledge Explorations in Economic History.

- Kuemmerle, T., Hostert, P., Radeloff, V. C., van der Linden, S., Perzanowski, K., & Kruhlov, I. (2008). Cross-border comparison of post-socialist farm land abandonment in the Carpathians. Ecosystems, 11, 614–628.

- Lasanta, T., Arnaez, J., Oserin, M., & Ortigosa, L. M. (2001). Marginal lands and erosion in terraced fields in the Mediterranean mountains. Mountain Research and Development, 21, 69–76.

- Lesschen, J. P., Cammeraat, L. H., & Nieman, T. (2008). Erosion and terrace failure due to agricultural land abandonment in a semi-arid environment. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 33, 1574–1584.

- Lieskovský, J., Kanka, R., Bezák, P., Stefunková, D., Petrovic, F., & Dobrovodská, M. (2013). Driving forces behind vineyard abandonment in Slovakia following the move to a market-oriented economy. Land Use Policy, 32(2013), 356–365.

- Lieskovský, J., Bezák, P., Špulerová, J., Lieskovský, T., Koleda, P., … Gimmi, U. (2015). The abandonment of traditional agricultural landscape in Slovakia – Analysis of extent and driving forces. Journal of Rural Studies, 37(2015), 75–84.

- Łowicki, D. (2008). Land use changes in Poland during transformation: Case study of Wielkopolska region. Landscape and Urban Planning, 87(4), 279–288.

- Mojses, M., & Petrovič, F. (2013). Land use changes of historical structures in the agricultural landscape at the local level – Hriňová case study. Ekológia (Bratislava), 32(1), 1–12.

- Novák, T. J., & Incze, J. (2014). Retaining walls of abandoned vineyard terraces on Tokaj Nagy Hill. 4D. Journal of Landscape Architecture And Garden Art, 35, 20–35.

- Novák, T. J., Incze, J., Spohn, M., Glina, B., & Giani, L. (2014). Soil and vegetation transformation in abandoned vineyards of the Tokaj Nagy-Hill. Catena, 123, 88–98.

- Nyizsalovszki, R., & Fórián, T. (2007). Human impact on the Landscape in the Tokaj Foothill Region, Hungary. Geogr. Fis. Din. Quat, 30, 219–224.

- Petit, C., Konold, W., & Höchtl, F. (2012). Historic terraced vineyards: Impressive witnesses of vernacular architecture. Landscape History, 33(1), 5–28.

- Pinczés, Z. (1969). Tertiary surfaces of the Tokaj (Zemplén) Mts. – Studia Geomorphol. Carpatho-Balcanica, 3, 3–14.

- Ruecker, G., Schad, P., Alcubilla, M. M., & Ferrer, C. (1998). Natural regeneration of degraded soils and site changes on abandoned agricultural terraces in Mediterranean Spain. Land Degradation & Abandonment, 9, 179–188.

- Stanchi, S., Godone, D., Belmonte, S., Freppaz, M., Galliani, C., & Zanini, E. (2013). Land suitability map for mountain viticulture: A case study in Aosta Valley (NW Italy). Journal of Maps, 9(3), 367–372.

- Sárospataky, M. (1789). Rátka és Tállya egy része, Magyar Országos Levéltár, Térképtár, S 57 No 0006, 48 × 32 cm [1:3600] 100 [öl = 52 mm].

- Szilassi, P. (2003). A területhasználat változásának okai és következményei a Káli-medence példáján [The reasons and consequences of land use change based on the example of the Kali-Basin]. Földrajzi Értesítő 2003. LII. évf. 3–4 füzet, pp 189–214

- Szilassi, P., & Kiss, R. (2001). Tájváltozás térinformatikai módszerekkel történő értékelése egy Balaton – felvidéki mintaterület (Fekete-hegy) példáján [Assessment of land use change with GIS methods based on a study area of Balaton Highland (Fekete hill)]. Magyar Földrajzi Konferencia

- Tarolli, P., Preti, F., & Romano, N. (2014). Terraced landscapes: From an old best practice to a potential hazard for soil degradation due to land abandonment. Anthropocene, 6, 10–25.

- Tóth, S. Z., Endrődi, J., & Horváth, G. (2014). Cadastral survey of unique landscape features via the example of Vászoly, Hungary. Landscape and Environment, 8(1), 20–35.

- References of maps

- I. Military Survey, digital edition. Kingdom of Hungary. 1:28.800, georeferenced edition. Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. Budapest. ISBN: 963 9374 95 4

- II. Military Survey, digital edition. Kingdom of Hungary. 1:28.800, georeferenced edition. Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. Budapest. ISBN: 963 7374 21 3

- III. Military Survey, digital edition 1869–1887, Kingdom of Hungary. 1:25.000, georeferenced edition. Arcanum Adatbázis Kft. Budapest. ISBN: 978-963-7374-54-8

- Topographic maps from the time of II World War. (1940–1944). HM – Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum Térképtár. In G. Tímár, G. Molnár, B. Székely, S. Biszak, & A. Jankó (Eds.), Magyarország Topográfiai Térképei a Második Világháború időszakából. Arcanum Adatbázis Kft., HM-HIM, HM-GEOSZ, Budapest, ISBN: 978-981 963-7374-71-5

- 1:25000 scale Topography Maps of Hungary (1969). Kartográfiai Vállalat, Országos Földügyi és Térképészeti Hivatal. Budapest.

- 1:10 000 Scale Topography Maps of Hungary in EOTR projection. (1985–1989) Kartográfiai Vállalat, Budapest

- Google Maps. (2010). Of Openlayer plugin in QGIS.