ABSTRACT

The Mt. Argentario promontory (southern Tuscany, Italy) is a protected area hosting habitats and species of European importance. The Mt. Argentario Natura 2000 habitat map (1:10,000) was compiled from photo-interpretation and field surveys, integrated with data from past cartographic and phytosociological studies. Conventional geographical information system procedures were used to select and manage spatial information, and delimit the map polygons. The following attributes were assigned to each map polygon: (i) habitat type name, with Natura 2000 code and (ii) percentage cover of the habitat type. Where multiple habitat types were associated in a mosaic attributed to the same polygon, the percentage cover of each habitat type was estimated. The survey allowed to identify and map a total of 13 Natura 2000 habitat types covering more than 40% of the study area. Presence and conservation importance of the detected habitat types are discussed, together with the usefulness of this kind of maps for monitoring and managing purposes.

1. Introduction

The conservation of biodiversity, at all its multiple levels of organization, is universally considered a crucial goal (CitationBalmford et al., 2002; CitationCafaro & Primack, 2014; CitationMillennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005), as shown by the numerous existing national and international agreements, frameworks and directives focused to stop and prevent biodiversity loss (see e.g. CitationCITES, 1973; CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992; CitationEuropean Commission, 2011; CitationSecretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2010; CitationUnited Nations, 1976, Citation1992, Citation2015). In the past, conservation was mainly focused on the species level (CitationIUCN, 2012, Citation2013; CitationMace et al., 2008), but in recent times it became increasingly evident that biodiversity can be more effectively represented, monitored and preserved by an ‘above species level approach’, because this may more efficiently represent the biological diversity as a whole and also indirectly preserve those species not yet or poorly known (CitationBerg et al., 2014; CitationCowling et al., 2004; CitationGaldenzi, Pesaresi, Casavecchia, Zivkovic, & Biond, 2012; CitationGigante, Attorre, et al., 2016; CitationIzco, 2015; CitationKeith et al., 2015; CitationKontula & Raunio, 2009; CitationNicholson, Keith, & Wilcove, 2009; CitationNoss, 1996; CitationRodríguez et al., 2011, Citation2012, Citation2015; CitationViciani, Lastrucci, Dell’Olmo, Ferretti, & Foggi, 2014). This ‘above species level unit’ can be an ecosystem, an ecological community or other similarly defined operational units (CitationIUCN, 2015; CitationNicholson et al., 2009). Habitats, in the pragmatic definition given in the European Directives (CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992; CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006, Citation2010), are considered a suitable ‘above species level’ operational unit and have become a central pillar of European nature conservation policy, because the maintenance of a series of habitats in good condition is one of the best ways to conserve species and biodiversity (CitationBerg et al., 2014; CitationBunce et al., 2013; CitationEvans, 2012; CitationGigante, Foggi, Venanzoni, Viciani, & Buffa, 2016; CitationKontula & Raunio, 2009; CitationNicholson et al., 2009; CitationRodríguez et al., 2011, Citation2012, Citation2015). This approach led also to the production of the first European Red List of Habitats (CitationJanssen et al., 2016).

According to the European Directive 92/43/EEC, the field identification of a habitat is based on matching it to one (or more) vegetation types (CitationAngiolini, Viciani, Bonari, & Lastrucci, 2017; CitationBiondi, Casavecchia, & Pesaresi, 2010; CitationBiondi et al., 2012; CitationBunce et al., 2013; CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006; CitationKeith et al., 2013, Citation2015; CitationRodwell et al., 2002; CitationViciani et al., 2014; CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo, et al., 2016; CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo, Vicenti, & Lastrucci, 2017). For this reason, several national and regional vegetation-mapping and vegetation data archiving projects are currently being carried out (e.g. CitationBonis & Bouzillé, 2012; CitationDimopoulos et al., 2012; CitationFont, Pérez-García, Biurrun, Fernández-González, & Lence, 2012; CitationGigante et al., 2012; CitationLanducci et al., 2012). Tuscany is one of the regions in which work is ongoing (CitationViciani, Lastrucci, et al., 2014; CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo, et al., 2016, Citation2017). The Tuscan Regional Administration and the University of Florence have just finished a comprehensive habitat mapping project (named HaSCITu) involving the mapping of conservation-relevant habitats in its Natura 2000 Sites of Community Importance (SCI, all confirmed now as Special Areas of Conservation – SACs), the protected areas that can reasonably be considered an essential framework for active in situ conservation (CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992; CitationFoggi, Viciani, Baldini, Carta, & Guidi, 2015). Accurate habitat mapping is an important tool in conservation (CitationAsensi & Díaz-Garretas, 2007; CitationBiondi et al., 2007; CitationLoidi, Ortega, & Orrantia, 2007; CitationPavone et al., 2007; CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo et al., 2016), especially in areas considered hot-spots of biodiversity, such as the Mediterranean basin (CitationCasazza et al., 2014; CitationMédail & Quézel, 1999; CitationMyers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca, & Kent, 2000). The aim of this study was to develop a Natura 2000 habitat map for Mt. Argentario, a Tuscan coastal promontory that was in the past one of the islands of the Tuscan Archipelago (central-northern Mediterranean basin), and today is a Special Area of Conservation, i.e. an important protected area of the Italian peninsula belonging to Natura 2000 network.

2. The study area

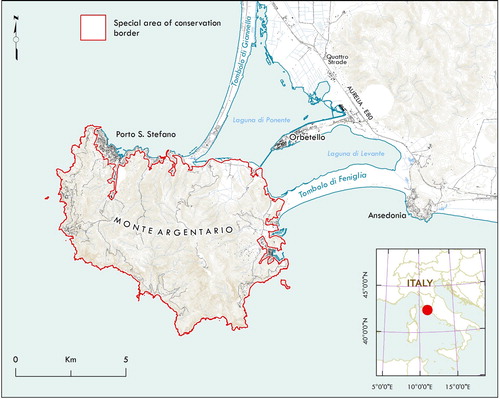

Mt. Argentario is an orographically isolated promontory located in the south-western Tuscan coast (), in the Mediterranean Biogeographic region (CitationEuropean Environment Agency, 2017). It is considered a ‘fossil island’, belonging in the past to the Tuscan Archipelago, because only in relatively recent times it was connected to the mainland by sand deposits, which formed two cordons of dunes and an internal lagoon (CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997; CitationLanza, 1984; CitationLazzarotto, Mazzanti, & Mazzoncini, 1964). It has an area of about 60 km2 and a coastline formed mainly by steep rocky cliffs, alternate with small stony and sometimes sandy inlets. Mt. Argentario has a varied orography, with Punta Telegrafo (635 m a.s.l.) being the highest point. It has a complex geology and geomorphology, with limestones and dolostones, metasandstones and acid metavolcanic rocks, calcschists and metamorphic ophiolites (CitationCarmignani & Lazzarotto, 2004). The climate is typically Mediterranean, with a mild winter and a warm and arid summer (CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997). The promontory as a whole is part of the Mediterranean macrobioclimate, pluviseasonal-oceanic bioclimate, with a lower mesomediterranean thermotype at lower altitudes and an upper mesomediterranean thermotype at higher altitudes (CitationPesaresi, Biondi, & Casavecchia, 2017).

The landscape is dominated by a typical Mediterranean sclerophyllous – evergreen forest and by its degradation stages, such as high and low matorrals, garrigues and discontinuous ephemeral grasslands (CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997). The vegetation has been heavily disturbed for millennia by anthropic recurrent fires, clearance for agricultural purposes, grazing and, in recent years, also by reforestations. As a consequence, the present vegetation is a mosaic of plant communities at different successional stages, influenced by the past land uses and by some natural local factors, such as different substrata, altitude, exposure, geomorphological features, distance from the sea, etc. (CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997).

A large part of the promontory surface (the main urban areas are excluded) is part of the Special Area of Conservation named ‘Monte Argentario, Isolotto di Porto Ercole e Argentarola’, a protected area of European importance (SAC code: IT51A0025 – Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC).

3. Methods

All the cartographic and phytosociological information available for Mt. Argentario was interpreted on the basis of our field knowledge. The main sources were CitationCavalli (1985), CitationArrigoni and Di Tommaso (1997), CitationArrigoni et al. (2001), but we also included studies on vegetation series by CitationBlasi (2010a, Citation2010b), CitationViciani, Lastrucci, Geri, and Foggi (2016) and previous vegetation studies and habitat maps concerning, in particular, the islands of the Tuscan Archipelago, because of their similarity with the study area (CitationBiondi, Vagge, & Mossa, 2000; CitationFoggi et al., 2006, Citation2011; CitationFoggi & Grigioni, 1999; CitationFoggi & Pancioli, 2008; CitationFoggi, Cartei, & Pignotti, 2008; CitationViciani, Albanesi, Dell’Olmo, & Foggi, 2011; CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo, et al., 2016). Data sources and correspondence between the available vegetation information and the mapped Natura 2000 habitat types are reported in Table S1.

The main vegetation survey regarding Mt. Argentario, by CitationArrigoni and Di Tommaso (1997), was carried out adopting the phytosociological method (CitationBiondi, 2011; CitationBraun-Blanquet, 1964) and consisted of over 110 phytosociological relevés that were surveyed and analysed across the whole territory, leading to the identification of several vegetation types of various syntaxonomical ranks (see CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso,1997). To update this information, we considered also a more recent and unpublished cartographic environmental study, with land use and phytosociological data, promoted by the Municipality of Mt. Argentario, but the main sources for the habitat map were field work and photo-interpretation.

In the period 2014–2016 many field surveys were carried out, with the aim of identifying the habitats of conservation interest. For photo-interpretation, we used the Tuscany Region aerial georeferenced orthophotos, true colour RGB, acquired in June and July 2013, with an on-the-ground pixel resolution of 50 × 50 cm, with accuracy guaranteed by the Tuscan Regional WMS Service. The interpretation of orthophotos, according to the ‘Photo Guided Method’ (CitationKüchler & Zonneveld, 1988; CitationZonneveld, 1979) together with the study of the spatial distribution of land use and vegetation types (recognized in the field on both physiognomic and phytosociological bases) allowed identification of land use and vegetation types at a scale between 1:5000 and 1:10,000. In order to delimit the different polygons, trough manual segmentation, we considered many factors: (i) the results of the field surveys that, together with the vegetation relevé data, provided georeferenced locations of the floristic composition of the local plant communities; (ii) the analysis of the orthophoto traits (colors, tones, textures and grain) around the relevé point that, together with the local geomorphological and lithological characteristics, helped us to define the borders between different typologies. Of course, in some difficult cases, when the transition between two community/habitat types were found to be gradual, the limits we assigned and the surface areas we calculated could be subjected to some changes. Using this information, a vegetation map (1:10,000) was compiled and used to derive the habitat map.

Information used to interpret the habitat types was derived from European Community documents and from the literature (CitationAngelini, Bianco, Cardillo, Francescato, & Oriolo, 2009; CitationAngelini, Casella, Grignetti, & Genovesi, 2016; CitationBiondi et al., 2010, Citation2012; CitationBiondi & Blasi, 2009, Citation2016; CitationCommission of the European Community, 1991, Citation1992; CitationEuropean Commission, 2013; CitationEvans, 2006, Citation2010). The map of conservation-interest habitats (sensu 92/43 EC Directive, Natura 2000) was created using GIS software.

To extract and select the information used, conventional GIS queries were employed. The following attributes were assigned to each map polygon: (i) habitat typology, with Natura 2000 code; (ii) percentage cover occupied by each habitat type. Where more than one habitat type co-occurred within the same polygon without being possible to separate them (very small and/or very fragmented units), we used the ‘mosaic’ concept. In such cases, the relative percentage cover of the habitat types forming the mosaic were estimated on the basis of professional and scientific experience acquired while conducting the field surveys. The equivalent area occupied by each habitat type was then calculated. The minimum mapping unit was assumed to be 2000 m2. Habitat types covering only polygons smaller than 2000 m2 were treated as points.

In the text, plant names are indicated without authors for brevity. The references for the complete nomenclature are CitationConti, Abbate, Alessandrini, and Blasi (2005) and the ‘anArchive’ database (CitationLucarini, Gigante, Landucci, Panfili, & Venanzoni, 2015).

4. Results and discussion

The Natura 2000 habitat map was released at 1:10,000 scale (Main Map). A total of 13 habitat types listed in Annex I of Habitat Directive were identified, distributed in single and/or multiple typological units (). Only one habitat (Caves not open to the public – Natura 2000 code: 8310) had areas below the minimum mapping unit and was marked on the maps as points (see map). The Natura 2000 habitats cover more than 40% of the total SAC area and have a total area of about 2330 ha (). The territory not covered by conservation interest habitats consists of urban and industrial areas, arable land and tree cultivations (mostly olive groves and vineyards), and artificial conifer plantations. Also, some natural- and semi-natural habitat types (e.g. several high and low maquis typologies), rather widespread, are not included in Natura 2000 habitat list, as already noted in other Mediterranean areas (CitationViciani, Dell’Olmo, et al., 2016). Two habitat types (Arborescent matorral with Laurus nobilis and Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea – Natura 2000 codes: 5230 and 6220, respectively) are of priority interest, i.e. deserve particular importance for conservation (CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992). They cover relatively small surface areas (), but are important, at least at regional and national scale, because they are not widespread, especially Arborescent matorral with L. nobilis (CitationFilibeck, 2006; CitationFoggi, Chegia, et al., 2006; CitationBiondi & Blasi, 2009). As shown in , the habitat types with higher cover values are sclerophyllous forests, followed by Mediterranean low matorrals and scrubs. The sclerophyllous forest habitat consists of woods dominated by Quercus ilex (Natura 2000 codes: 9340), which represents more than 72% of the total cover of the Natura 2000 habitat types of the SAC (). Small patches of Castanea sativa woods (Natura 2000 codes: 9260), of clear artificial origin (CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997), are present in the northern slopes of the promontory. Low matorral and scrub formations (Thermo-Mediterranean and pre-desert scrub – Natura 2000 codes: 5330) cover a notable percentage of the habitat area (); this habitat includes different vegetation types: (i) one more widespread, formed by garrigues with Erica multiflora, Cistus sp. pl. and other woody species invaded and dominated by the large tussock grass Ampelodesmos mauritanicus, whose presence is encouraged by recurrent fires (CitationBaldini, 1995); (ii) sporadic and small surface tree-spurge formations, dominated by Euphorbia dendroides, located in the more rocky, warm and arid slopes; (iii) very rare and sporadic garrigues, dominated by Palmetto (Chamaerops humilis), which reaches in the northern Thyrrenian sea one of its northern distribution limits. The habitats of the coastal rocky cliffs are well-represented by (i) the ‘Vegetated cliffs with Limonium spp.’ (Natura 2000 code: 1240), which is important also from a biogeographic and conservation viewpoint, as it hosts the strict endemic Limonium multiforme (CitationFenu et al., 2016); (ii) the ‘Low formations of Euphorbia close to cliffs’ (Natura 2000 code: 5320), here dominated by Helichrysum litoreum or Anthyllis barba-jovis (CitationBrullo & De Marco, 1989; CitationBiondi et al., 2000); (iii) the ‘Arborescent matorral with Juniperus spp.’ (Natura 2000 code: 5210), dominated by Juniperus phoenicea subsp. turbinata and other thermophilous species (Olea oleaster, Pistacia lentiscus, Prasium majus, Teucrium fruticans, etc., see CitationArrigoni & Di Tommaso, 1997). Some patches of halophytic habitats (Natura 2000 codes: 1310, 1410 and particularly 1420 – Mediterranean and thermo-Atlantic halophilous scrubs – see ) are present in the eastern lowlands bordering the Orbetello Lagoon, where the halophilous vegetation is widespread (CitationAndreucci, 2004). The inland rocky habitat is represented by ‘Calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation’ (Natura 2000 code: 8210); it is widespread in several sites located on very steep and southern-exposed rocky outcrops, but patches with mappable surface area are concentrated mainly in the area of Costa della Scogliera, above Cala Acqua Dolce (Main Map).

Table 1. Natura 2000 habitat types of the Mt. Argentario Special Area of Conservation (SAC), with surface areas (ha) and cover percentages, with respect to the total area of the SAC and to the overall area covered by Natura 2000 habitats.

5. Conclusions

The production of an accurate habitat map represents an extremely valuable tool for knowing and managing a protected area, and the scale 1:10,000 can be considered accurate and highly suitable at regional and local scale, at least for Italy (CitationBagnaia, Bianco, & Laureti, 2009). Moreover, the EC Member States have to guarantee, at least for the Natura 2000 habitats for which a SAC has been designated, a Favourable Conservation Status, with requirements for monitoring and reporting (CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992; CitationEvans & Arvela, 2011; CitationOstermann, 1998) and the European and national methodological frameworks for monitoring conservation interest habitats consider habitat mapping as crucial (CitationAngelini et al., 2016; CitationGigante, Attorre, et al., 2016; CitationJanssen et al., 2016).

Producing such maps requires a significant commitment in terms of personnel, time and resources. Indeed, an accurate habitat map can be derived only from a previous detailed vegetation map, whose preparation generally involves a large amount of work, such as GIS analysis, field surveys, plant identification, creation of databases, statistical analyses, syntaxonomical checks, etc., performed by expert personnel (GIS and vegetation scientists). Even if, as in the case of Mt. Argentario, the phytosociological knowledge is almost entirely available, for the updating and checking of phytosociological and cartographic data, both in office and in the field, and for the conversion of such data to habitat information, at least the work of two experts for a few weeks is necessary.

To periodically check their conservation status and trends, and to verify if the EU biodiversity policy has been effective (CitationEvans, 2012; CitationHenle et al., 2013), in Europe Annex I Habitats monitoring is mandatory every six years for the countries belonging to European Union (CitationCommission of the European Community, 1992; CitationGigante, Attorre, et al., 2016). Nevertheless, only in recent times, this task begins to be standardized and coordinated, at least at the national level in Italy (CitationAngelini et al., 2016; CitationGigante et al., 2018; CitationGigante, Attorre, et al., 2016). Considering the high number of Natura 2000 Special Areas of Conservation in Italy (only in Tuscany they are 131), it must be noted that without adequate and recurrently financial resources granted by regional and national administrations, habitat monitoring risks being able to be realized only partially.

Software

The maps were created and edited using the software ESRI ArcGIS 10.4.

Table_S1.xlsx

Download MS Excel (12.7 KB)MONTE ARGENTARIO (Tuscany) HABITAT MAP

Download PDF (6.2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Daniele Viciani http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-5999

Bruno Foggi http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6451-4025

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andreucci, F. (2004). La vegetazione alofila della laguna di Orbetello (Toscana, Grosseto). Fitosociologia, 41(2), 31–49.

- Angelini, P., Bianco, P., Cardillo, A., Francescato, C., & Oriolo, G. (2009). Gli habitat in Carta della Natura. Roma: Dipart. Difesa della Natura, I.S.P.R.A.

- Angelini, P., Casella, L., Grignetti, A., & Genovesi, P. (Eds.). (2016). Manuali per il monitoraggio di specie e habitat di interesse comunitario (Direttiva 92/43/CEE) in Italia: habitat. ISPRA, Serie Manuali e Linee Guida, 142/2016. Roma: I.S.P.R.A.

- Angiolini, C., Viciani, D., Bonari, G., & Lastrucci, L. (2017). Habitat conservation prioritization: A floristic approach applied to a Mediterranean wetland network. Plant Biosystems, 151(4), 598–612. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2016.1187678

- Arrigoni, P. V., Baldini, R. M., Corsi, M., Della Monaca, G., Del Prete, C., Lenzi, M., & Tosi, G. (2001). Geobotanica ed etnobotanica del Monte Argentario (p. 245). Pitigliano: Laurum Ed.

- Arrigoni, P. V., & Di Tommaso, P. L. (1997). La vegetazione del Monte Argentario (Toscana meridionale). Parlatorea, 2, 5–38.

- Asensi, A., & Díaz-Garretas, B. (2007). Cartografía de los hábitat naturales y seminaturales en el Parque Natural del Estrecho (Cádiz, España). Estado de conservación. Fitosociologia, 44(2) suppl. 1, 17–22.

- Bagnaia, R., Bianco, P., & Laureti, L. (2009). Carta della Natura alla scala 1:10.000. Ipotesi di lavoro (p. 16). Roma: ISPRA. Retrieved from http://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/carta-della-natura/ipotesi-1-10000.pdf

- Baldini, R. M. (1995). Flora vascolare del Monte Argentario (Arcipelago Toscano). Webbia, 50(1), 67–191. doi: 10.1080/00837792.1995.10670598

- Balmford, A., Bruner, A., Cooper, P., Costanza, R., Farber, S., Green, R. E., … Turner, K. T. (2002). Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. Science, 297, 950–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1073947

- Berg, C., Abdank, A., Isermann, M., Jansen, F., Timmermann, T., Dengler, J., & Mucina L. (2014). Red Lists and conservation prioritization of plant communities – A methodological framework. Applied Vegetation Science, 17, 504–515. doi: 10.1111/avsc.12093

- Biondi, E. (2011). Phytosociology today: Methodological and conceptual evolution. Plant Biosystems, 145( supplement 1), 19–29. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2011.602748

- Biondi, E., & Blasi, C. (Coord.). (2009). Manuale italiano di interpretazione degli Habitat della Direttiva 92/43/CEE [online]. Retrieved from http://vnr.unipg.it/habitat/

- Biondi, E., & Blasi, C. (2016). Prodromo della vegetazione d’Italia [online]. Retrieved from http://www.prodromo-vegetazione-italia.org/

- Biondi, E., Burrascano, S., Casavecchia, S., Copiz, R., Del Vico, E., Galdenzi, D., … Blasi, C. (2012). Diagnosis and syntaxonomic interpretation of Annex I Habitats (Dir. 92/43/EEC) in Italy at the alliance level. Plant Sociology, 49, 5–37.

- Biondi, E., Casavecchia, S., & Pesaresi, S. (2010). Interpretation and management of the forest habitats of the Italian peninsula. Acta Botanica Gallica, 157(4), 687–719. doi: 10.1080/12538078.2010.10516242

- Biondi, E., Catorci, A., Pandolfi, M., Casavecchia, S., Pesaresi, S., Galassi, S., … Zabaglia, C. (2007). Il Progetto di ‘Rete Ecologica della Regione Marche’ (REM): per il monitoraggio e la gestione dei siti Natura 2000 e l’organizzazione in rete delle aree di maggiore naturalità. Fitosociologia, 44(2), suppl. 1, 89–93.

- Biondi, E., Vagge, I., & Mossa, L. (2000). On the phytosociological importance of Anthyllis barba-jovis L. Colloques Phytosociologiques, 27, 95–104.

- Blasi, C. (Ed.). (2010a). La vegetazione d’Italia. Roma: Palombi & Partner srl.

- Blasi, C. (Ed.). (2010b). La vegetazione d’Italia. Carta delle Serie di Vegetazione, scala 1:500000. Roma: Palombi & Partner srl.

- Bonis, A., & Bouzillé, J.-B. (2012). The project VegFrance: Towards a national vegetation database for France. Plant Sociology, 49, 97–99.

- Braun-Blanquet, J. (1964). Pflanzensoziologie. Wien: Springer Verlag.

- Brullo, S., & De Marco, G. (1989). Antyllidion barbae-jovis alleanza nuova dei Crithmo-Limonietea. Archivio Botanico e Biogeografico Italiano, 65(1-2), 109–120.

- Bunce, R. G. H., Bogers, M. M. B., Evans, D., Halada, L., Jongman, R. H. G., Mücher, C. A., … Olsvig-Whittaker, L. (2013). The significance of habitats as indicators of biodiversity and their links to species. Ecological Indicators, 33, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.07.014

- Cafaro, P., & Primack, R. (2014). Species extinction is a great moral wrong. Biological Conservation, 170, 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.022

- Carmignani, L., & Lazzarotto, A. (coord.). (2004). Carta geologica della Toscana (scala 1:250.000). Firenze: Università di Siena, Dipart. Scienze della Terra, Centro di GeoTecnologie, RegioneToscana. Litografia Artistica Cartografica.

- Casazza, G., Giordani, P., Benesperi, R., Foggi, B., Viciani, D., Filigheddu, R., … Mariotti, M. G. (2014). Climate change hastens the urgency of conservation for range-restricted plant species in the central-northern Mediterranean region. Biological Conservation, 179, 129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.09.015

- Cavalli, S. (1985). Carta del paesaggio vegetale del Monte Argentario. Scala 1:15.000. Florence, Italy: SELCA Firenze, Regione Toscana, Comune di Monte Argentario.

- CITES. (1973). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Signed at Washington, D.C., on 3 March 1973. Amended at Bonn, on 22 June 1979 [online]. Retrieved from http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/text.php

- Commission of the European Community. (1991). CORINE biotopes manual – Habitats of the European Community. Luxembourg: Commission of the European Community.

- Commission of the European Community. (1992). Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Official Journal L206. 22.07.92 (Consolidated version 1.1.2007).

- Conti, F., Abbate, G., Alessandrini, A., & Blasi, C. (2005). An annotated checklist of the Italian vascular flora. Roma: Palombi Editori.

- Cowling, R. M., Knight, A. T., Faith, D. P., Ferrier, S., Lombard, A. T., Driver, A., … Desmet, P. G. (2004). Nature conservation requires more than a passion for species. Conservation Biology, 18, 1674–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00296.x

- Dimopoulos, P., Tsiripidis, I., Bergmeier, E., Fotiadis, G., Theodoropoulos, K., Raus, T., … Mucina, L. (2012). Towards the Hellenic National Vegetation Database: VegHellas. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 81–87.

- European Commission. (2011). Our life insurance, our natural capital: An EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. COM/2011/0244 final [online]. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52011DC0244

- European Commission. (2013). Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats, vers. EUR28. Brussel: European Commission, DG Environment.

- European Environment Agency. (2017). Biogeographical regions in Europe – Map. Retrieved from www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/biogeographical-regions-in-europe-2

- Evans, D. (2006). The habitats of the European Union Habitats Directive. Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 106, 167–173.

- Evans, D. (2010). Interpreting the habitats of Annex I. Past, present and future. Acta Botanica Gallica, 157, 677–686. doi: 10.1080/12538078.2010.10516241

- Evans, D. (2012). Building the European Union’s Natura 2000 network. Nature Conservation, 1, 11–26. doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.1.1808

- Evans, D., & Arvela, M. (2011). Assessment and reporting under Article 17 of the Habitats Directive. Explanatory Notes & Guidelines for the period 2007–2012. Final version. July 2011. ETC-BD. Brussel: European Commission.

- Fenu, G., Bacchetta, G., Bernardo, L., Calvia, G., Citterio, S., Foggi, B., … Orsenigo, S. (2016). Global and regional IUCN Red List assessments: 2. Italian Botanist, 2, 93–115. doi:10.3897/italianbotanist.2.10975.

- Filibeck, G. (2006). Notes on the distribution of Laurus nobilis L. (Lauraceae) in Italy. Webbia, 61(1), 45–56. doi: 10.1080/00837792.2006.10670794

- Foggi, B., Cartei, L., & Pignotti, L. (2008). La vegetazione dell’Isola di Pianosa (Arcipelago Toscano, Livorno). Braun-Blanquetia, 43, 1–41.

- Foggi, B., Cartei, L., Pignotti, L., Signorini, M. A., Viciani, D., Dell’Olmo, L., & Menicagli, E. (2006). Il paesaggio vegetale dell’Isola d’Elba (Arcipelago Toscano). Studio di fitosociologia e cartografico. Fitosociologia, 43(1), Suppl. 1, 3–95.

- Foggi, B., Chegia, B., & Viciani, D. (2006). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione del Promontorio di Piombino (Livorno – Toscana). Parlatorea, 8, 121–139.

- Foggi, B., Cioffi, V., Ferretti, G., Dell’Olmo, L., Viciani, D., & Lastrucci, L. (2011). La vegetazione dell’Isola di Giannutri (Arcipelago Toscano, Livorno). Fitosociologia, 48(2), 23–44.

- Foggi, B., & Grigioni, A. (1999). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell’isola di Capraia. Parlatorea, 3, 5–33.

- Foggi, B., & Pancioli, V. (2008). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell’Isola del Giglio (Arcipelago Toscano, Toscana meridionale). Webbia, 63(1), 25–48. doi: 10.1080/00837792.2008.10670831

- Foggi, B., Viciani, D., Baldini, R. M., Carta, A., & Guidi, T. (2015). Conservation assessment of the endemic plants of the Tuscan Archipelago, Italy. Oryx, 49(1), 118–126. doi: 10.1017/S0030605313000288

- Font, X., Pérez-García, N., Biurrun, F., Fernández-González, F., & Lence, C. (2012). The Iberian and Macaronesian Vegetation Information System (SIVIM, www.sivim.info), five years of online vegetation’s data publishing. Plant Sociology, 49, 89–95.

- Galdenzi, D., Pesaresi, S., Casavecchia, S., Zivkovic, L., & Biond, I. E. (2012). The phytosociological and syndynamical mapping for the identification of High Nature Value Farmland. Plant Sociology, 49(2), 59–69.

- Gigante, D., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Armiraglio, S., Assini, S., Attorre, F., … Viciani, D. (2018). Habitat conservation in Italy: The state of the art in the light of the first European Red List of Terrestrial and Freshwater Habitats. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali. Published online. doi: 10.1007/s12210-018-0688-5

- Gigante, D., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Attorre, F., Cambria, V. E., Casavecchia, S., … Venanzoni, R. (2012). Vegitaly: Technical features, crucial issues and some solutions. Plant Sociology, 49, 71–79.

- Gigante, D., Attorre, F., Venanzoni, R., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Aleffi, M., & Zitti, S. (2016). A methodological protocol for Annex I Habitat monitoring: The contribution of vegetation science. Plant Sociology, 53, 77–87.

- Gigante, D., Foggi, B., Venanzoni, R., Viciani, D., & Buffa, G. (2016). Habitats on the grid: The spatial dimension does matter for red-listing. Journal for Nature Conservation, 32, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2016.03.007

- Henle, K., Bauch, B., Auliya, M., Külvik, M., Pe’er, G., Schmeller, D. S., & Framstad, E. (2013). Priorities for biodiversity monitoring in Europe: A review of supranational policies and a novel scheme for integrative prioritization. Ecological Indicators, 33, 5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.028

- IUCN. (2012). IUCN red list categories and criteria. Version 3.1. 2nd ed. Gland: Author.

- IUCN. (2013). Guidelines for using the IUCN Red List categories and criteria. Version 10.1. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Subcommittee.

- IUCN. (2015). Guidelines for the application of IUCN Red List of ecosystems categories and criteria, version 1.0. Edited by L. M. Bland, D. A. Keith, N. J. Murray, & J. P. Rodríguez. Gland: IUCN. ix+93 pp.

- Izco, J. (2015). Risk of extinction of plant communities: Risk and assessment categories. Plant Biosystems, 149, 589–602. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2014.1000998

- Janssen, J. A. M., Rodwell, J. S., García Criado, M., Gubbay, S., Haynes, T., Nieto, A., & Valachovič, M. (2016). European Red List of habitats. Part 2. Terrestrial and Freshwater Habitats (p. 38). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. ISBN 978-92-79-61588-7. doi: 10.2779/091372

- Keith, D. A., Rodríguez, J. P., Brooks, T. M., Burgman, M. A., Barrow, E. G., Bland, M., … Spalding, M. D. (2015). The IUCN Red List of ecosystems: Motivations, challenges, and applications. Conservation Letters, 8, 214–226. doi: 10.1111/conl.12167

- Keith, D. A., Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Nicholson, E., Aapala, K., Alonso, A., … Zambrano-Martinez, S. (2013). Scientific foundations for an IUCN Red List of ecosystems. PLoS One, 8(5), e62111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062111

- Kontula, T., & Raunio, A. (2009). New method and criteria for national assessments of threatened habitat types. Biodiversity and Conservation, 18, 3861–3876. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9684-5

- Küchler, A. W., & Zonneveld, I. S. (1988). Vegetation mapping. Handbook of vegetation science (Vol. 10). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

- Landucci, F., Acosta, A. T. R., Agrillo, E., Attorre, F., Biondi, E., Cambria, V. E., … Venanzoni, R. (2012). Vegitaly: The Italian collaborative project for a national vegetation database. Plant Biosystems, 146, 756–763. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2012.740093

- Lanza, B. (1984). Sul significato biogeografico delle isole fossili, con particolare riferimento all’arcipelago pliocenico della Toscana. Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze naturali e Museo civico di Storia naturale di Milano, 12.5(3-4), 145–158.

- Lazzarotto, A., Mazzanti, R., & Mazzoncini, F. (1964). Geologia del Promontorio Argentario (Grosseto) e del Promontorio del Franco (Isola del Giglio-Grosseto). Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana, 83, 1–124.

- Loidi, J., Ortega, M. & Orrantia, O. (2007). Vegetation science and the implementation of the Habitat Directive in Spain: up-to-now experiences and further development to provide tools for management. Fitosociologia, 44(suppl. 1), 9–16.

- Lucarini, D., Gigante, D., Landucci, F., Panfili, E., & Venanzoni, R. (2015). The anArchive taxonomic checklist for Italian botanical data banking and vegetation analysis: Theoretical basis and advantages. Plant Biosystems, 149, 958–965. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2014.984010

- Mace, G. M., Collar, N. J., Gaston, K. J., Hilton-Taylor, C., Akcakaya, H. R., Leader-Williams, N., … Stuart, S. N. (2008). Quantification of extinction risk: IUCN’s system for classifying threatened species. Conservation Biology, 22, 1424–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01044.x

- Médail, F., & Quézel, P. (1999). Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: Setting global conservation priorities. Conservation Biology, 13, 1510–1513. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.98467.x

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. (2005). Ecosystems and human wellbeing: Biodiversity synthesis. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B., & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

- Nicholson, E., Keith, D. A., & Wilcove, D. S. (2009). Assessing the threat status of ecological communities. Conservation Biology, 23, 259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.01158.x

- Noss, R. F. (1996). Ecosystems as conservation targets. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 351. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)20058-8

- Osterman, O. P. (1998). The need for management of nature conservation sites designated under Natura 2000. Journal of Applied Ecology, 35, 968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.1998.tb00016.x

- Pavone, P., Spampinato, G., Tomaselli, V., Minissale, P., Costa, R., Sciandrello, V., & Ronsisvalle F. (2007). Cartografia degli habitat della Direttiva CEE 92/43 nei biotopi della Provincia di Siracusa (Sicilia orientale). Fitosociologia, 44(suppl. 1), 183–193.

- Pesaresi, S., Biondi, E., & Casavecchia, S. (2017). Bioclimates of Italy. Journal of Maps, 13(2), 955–960. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2017.1413017

- Rodríguez, J. P., Keith, D. A., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Murray, N. J., Nicholson, E., Regan, T. J., & Wit, P. (2015). A practical guide to the application of the IUCN RedList of ecosystems criteria. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 370, 20140003. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0003

- Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Baillie, J. E. M., Ash, N., Benson, J., Boucher, T., … Zamin, T. (2011). Establishing IUCN Red List Criteria for Threatened Ecosystems. Conservation Biology, 25, 21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01598.x

- Rodríguez, J. P., Rodríguez-Clark, K. M., Keith, D. A., Barrow, E. G., Benson, J., Nicholson, E., & Wit, P. (2012). IUCN Red List of ecosystems. S.A.P.I.EN.S, 5, 60–70.

- Rodwell, J. S., Schaminée, J. H. J., Mucina, L., Pignatti, S., Dring, J., & Moss, D. (2002). The diversity of European vegetation. An overview of phytosociological alliances and their relationships to EUNIS habitats. Wageningen: Ministry of Agriculture Nature Management and Fisheries, The Netherlands and European Environmental Agency.

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. (2010). Global biodiversity outlook 3. Montréal: Author.

- United Nations. (1976). Convention on Wetlands of International Importance especially as Waterfowl Habitat. Concluded at Ramsar, Iran, 2/2/1971. UN Treaty Series N. 14583, Vol. 996, 246–268.

- United Nations. (1992). Convention on biological diversity. United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. UN Treaty Series. Vol. 1760.

- United Nations. (2015). Sustainable development goals. New York: United Nations [online]. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ summit/

- Viciani, D., Albanesi, D., Dell’Olmo, L., & Foggi, B. (2011). Contributo alla conoscenza della vegetazione dell’Isola di Gorgona (Arcipelago Toscano) (con carta in scala 1: 5.000). Fitosociologia, 48(2), 45–64.

- Viciani, D., Dell’Olmo, L., Ferretti, G., Lazzaro, L., Lastrucci, L., & Foggi, B. (2016). Detailed Natura 2000 and Corine Biotopes habitat maps of the island of Elba (Tuscan Archipelago, Italy). Journal of Maps, 12(3), 492–502. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2015.1044040

- Viciani, D., Dell’Olmo, L., Vicenti, C., & Lastrucci, L. (2017). Natura 2000 protected habitats, Massaciuccoli Lake (northern Tuscany, Italy). Journal of Maps, 13(2), 219–226. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2017.1290557

- Viciani, D., Lastrucci, L., Dell’Olmo, L., Ferretti, G., & Foggi, B. (2014). Natura 2000 habitats in Tuscany (central Italy): synthesis of main conservation features based on a comprehensive database. Biodiversity and Conservation, 23, 1551–1576. doi: 10.1007/s10531-014-0686-6

- Viciani, D., Lastrucci, L., Geri, F., & Foggi, B. (2016). Gap analysis comparing protected areas with potential natural vegetation in Tuscany (Italy) and a GIS procedure to bridge the gaps. Plant Biosystems, 150, 62–72. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2014.950623

- Zonneveld, I. S. (1979). Land evaluation and land(scape) science. Use of aerial photographs in geography and geomorphology. ITC textbook of photointerpretation, Volume VII, ITC.