ABSTRACT

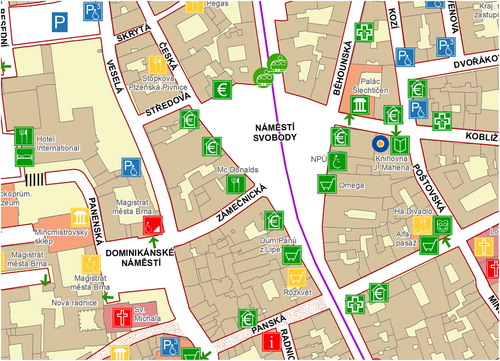

Accessibility mapping is an emerging initiative across the world since people with impaired mobility are becoming more and more integrated into mainstream society. People with impaired mobility include, for example, wheelchair users, elderly people, pregnant women, or people with babies in prams or with children under three years of age. They can constitute up to 30% of the population. This paper therefore aims at creating the map for the ‘Accessibility Guide to Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility’ published in a paper and on the Web by Brno City Municipality (Czech Republic) in cooperation with Masaryk University between 2012 and 2016. Issues with respect to methodology, visualisation, as well as perception are discussed (Main Map). The developed map presents complex information about the accessibility of buildings in Brno city centre. General accessibility is displayed by specially developed map symbols presenting two types of information, quantitative information, i.e. the level of accessibility, and qualitative information, i.e. the type of the location.

1. Introduction

Currently, there is increasing interest in accessibility mapping because society is becoming more open to people with special needs, such as those with impaired mobility. Various tools for people with impaired mobility are being created. Accessibility mapping is one of the ways of helping disabled people integrate into mainstream society. The approach to people with impaired mobility is specific to every culture, as is the approach of people to using maps or other orientation devices. Therefore, there has been no general research into the topic of accessibility mapping and only local studies have been performed. Also, maps which are created for a specific cultural background are of limited transferability.

One of the greatest challenges facing accessibility mapping is the fact that the spectrum of map users is very wide, many such users having very different requirements. It is therefore very difficult to define the target group of users for accessibility maps and create proper map symbolisation and visualisation. Paradoxically, some users are even more handicapped by using maps, i.e. wheelchair users who have used a wheelchair since early childhood and have grown up in an institution for people with disabilities have, according to research, worse orientation in space than people who became wheelchair users in later life (CitationOsman, 2014). Selected issues concerning the conducted research are described in CitationMulicek, Osman, and Seidenglanz (2013). The principles of localisation by means of mobile phones were described by CitationReznik, Horakova, and Szturc (2015) and CitationYang, Sheng, and Zeng (2015), automated map generation by CitationŠtampach and Mulíčková (2016), and cartographic visualization by CitationŠtampach, Kubíček, and Herman (2015) as well as CitationStachoň et al. (2016).

National definitions and regulations on accessibility (mapping) are available in many countries of the world (see the following section). For instance, according to Czech CitationNotice 398/2009 Sb., which must be followed in the field of accessibility mapping, people with impaired mobility are defined as people with physical handicap, elderly people (in the Czech Republic, people aged 65 and above), pregnant women, and people with babies in prams or with children under three years of age. They can constitute up to 30% of the population. The assumption legally defined by the Czech Notice 398/2009 states that if an object is considered as accessible for wheelchair users, it is also considered as accessible for other groups of people with impaired mobility.

At the authors’ institution, the topics of accessibility and accessibility mapping have been subjects of research for ten years, including 3D visualizations as described by CitationReznik (2013) as well as by CitationHerman and Reznik (2013). The research includes student fieldwork and theses in cooperation with Brno City Municipality and two institutions catering for wheelchair users. The methodology for accessibility mapping was established together with the Liga vozíčkářů, z.ú. (in English ‘League of wheelchair users’), a non-profit organisation comprising hundreds of wheelchair users. This methodology was employed in fieldwork in conjunction with representatives of the Liga vozíčkářů, z.ú. In total, 3000 buildings were mapped. The concept of the created map and atlas was developed by CitationJaňura (2011), CitationStehlíková (2012), CitationStehlíková (2018), and CitationOsman (2014); the mapping of public transport infrastructure was developed by CitationHavlas (2011); and an interactive Web version of the map was developed by CitationSháněl (2016). The Health Department of Brno City Municipality revised all the gathered data. The concept of the accessibility map was inspired by similar mapping in Prague (CitationPrazska organizace vozickaru, 2010) as well as by more than 50 examples of accessibility maps from around the world (CitationStehlíková, 2018). Several accessibility maps, such as the one for Prague, focused on the level of whole blocks of buildings. In contrast, accessibility mapping in Brno was, from the beginning, performed at the level of individual buildings.

The result of all these activities is the Accessibility Guide to Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility (CitationBrno City Municipality, 2016) in cooperation with Brno City Municipality, the first edition of which was published in 2012. Masaryk University and Brno City Municipality both engaged in accessibility mapping, Masaryk University produced the final map, and institutions representing wheelchair users provided feedback.

1.1. Accessibility mapping in the world

In every part of the world, there are local accessibility strategies: In the USA, accessibility guides are usually available for every larger city. Such guides are usually prepared without a map. A useful example of an accessibility guide is that developed for the city of Minneapolis (CitationMinneapolis City by Nature, 2014). However, there are accessibility maps for many universities in the USA such as The University of Kansas with its Accessibility Map, Brown University with its CitationBrown University Campus Accessibility Map (2014), and Boston University with its Boston University Maps (http://www.bu.edu/maps/) (The University of Kansas, Citationn.d.). Some cities also offer accessibility maps for people with limited mobility, e.g. The Downtown Seattle Accessible Map and Guide (CitationKing Country Metro, n. d.). Another means of presenting accessibility is a mobile application such as Wheely (http://www.wheelyapp.com/), which is an accessibility guide to New York City.

In Australia, the system of accessibility mapping is highly developed and there is a Mobility Map for almost every city. URL links to all the available mobility maps can be found on the MobilityMaps.com.au webpage (http://www.mobilitymaps.com.au/).

In the European Union, most countries have a national scheme for presenting accessibility information. Accessibility mapping and the presentation of accessibility information is highly developed in Germany. A good example of an accessibility map developed on the ArcGIS online platform is the Lisbon Wheelchair Map (CitationESRI, n. d.). The Mind the Accessibility Gap conference was held in Brussels in 2014, where the general approach to presenting accessibility information in Europe was presented and discussed. Spain provides ‘The Technical and Design Guide on Accessibility in Greenways’, prepared by PREDIF (the State Representative Platform for People with Physical Disability) in collaboration with the Spanish Railways Foundation; it is available under the URL http://www.viasverdesaccesibles.es/ The European Greenways Association and the Spanish Railways Foundation are developing the project ‘Accessible Tourism in European Greenways: Greenways for All’ (Greenways4ALL), which has already published the ‘Catalogue of accessible tourism products in Greenways in Spain and Portugal,’ Citation2017 (see http://www.viasverdes.com/pdf/CatalogoGW4ALL_ENG.pdf) that follows the methodology as defined by Guía Tecnica y de Diseño Sobre Accesibilad en Vías Verdes [Technical and Design Guide on Greenways Accessibility] (Citation2018).

Some worldwide webpages aim to provide accessibility information. One example is Wheelmap.org (https://wheelmap.org), which is an interactive accessibility map with a base map taken from Open Street Maps and into which anyone can insert information. For some parts of the world, a great deal of information is available; for other parts the information is extremely scant. For example, most German cities have published accessibility information for this website. Another webpage is MyAccessible.EU (http://myaccessible.eu/), which is associated with Wheelmap.org but only covers Europe. A similar crowdsourced website is WheelchairTravel.org (https://wheelchairtravel.org/), which offers accessibility information on very large cities in the USA, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Google, meanwhile, plans to add accessibility information as a feature of Google Maps (CitationKumparak, 2016).

1.2. The map overview

The map ‘An Accessible Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility’ (Main Map) is a part of the Accessibility Guide to Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility (CitationBrno City Municipality, 2016) published in 2016, which is the third edition of the Guide. The map is designed for people with very different needs and abilities with respect to moving and reading maps. Locations at the level of buildings displayed on the map are divided into three categories according to their general level of accessibility: ‘accessible’, ‘accessible with assistance’, and ‘inaccessible’. The main purpose is to highlight locations which are accessible and ready to use for people with impaired mobility (known also under the term ‘people with limited mobility’). However, public institutions and cultural amenities such as theatres and museums are mapped in their entirety, even though many are not accessible.

The degree of accessibility is presented by the colour of the relevant map symbol. In the text part of the guide, there is also a great deal of more detailed information about the accessibility of locations, such as information about lifts, toilets, staircases, handrails or ramps, and narrow doors, which cannot be displayed directly on the map.

2. Methods

Accessibility mapping and map production require several different approaches. These include establishing a methodology for acquiring accessibility data, using appropriate methods of cartographic visualisation, and creating suitable map symbols.

To determine whether a location is accessible or inaccessible is a complete task and several criteria have to be considered. People with impaired mobility have different capacities and the same location could be easily accessible for one person but completely inaccessible for another. Among people with impaired mobility, wheelchair users often tend to have some of the highest requirements with respect to accessibility. Personal visits to all locations covered by the map were necessary and were undertaken by Brno City Municipality.

The conducted accessibility mapping followed the requirements defined in national legislation (Czech CitationNotice 398/2009); however, it went further with respect to its complexity and depth. The following criteria and requirements were used to assess the degree of accessibility at a given location:

Access to the building itself: the surface of the sidewalk had to be even (with up to 2 cm of height variation and up to 5 mm of height variation between contiguous tiles/paving stones), solid, and non-slippery, with a maximum slope of no more than 8% for a ramp of up to 9 m in length (or no more than 12.5% for a ramp of up to 3 m in length). A fixed ramp had to have a minimum length of 1.1 m.

Building entrance: an entrance was considered barrier-free when it was at the same level as the adjoining path or ramp (up to 2 cm height differences were tolerated); when its doors were composed of leaves that were at least 80 cm wide; and when the free space in front of the door was at least 1.5 × 1.5 m in area (or 2 × 1.5 m in the case of a door that opened outwards). A building entrance was considered to be partly accessible (accessible with assistance) in cases when, for example, a ramp was too steep, there was a height difference of up to 10 cm, or doors were heavy and more difficult to manipulate, etc. The presence of a door bell, a video-telephone, a ramp (even a temporary one), an elevator (including an elevator for a wheelchair, with a free space of at least 1.00 × 1.25 m in area), and stairs was always documented.

Accessibility within a building: it was explicitly determined whether the whole interior of a building was accessible, whether only the entrance floor remained accessible while the other floors were inaccessible, or even whether there was a barrier immediately after the entrance (such as stairs) that made the interior of a building completely inaccessible. Relevant features were also mapped, i.e. those assisting movement within a building, such as an elevator, ramp, or information/orientation system, etc. Special attention was paid to the accessibility of a toilet. The following criteria were applied: the minimum size of a cubicle had to be 1.6 × 1.6 m in area (1.4 × 1.4 m in the case of a partly accessible toilet); the door had to be at least 90 cm wide; the space in front of the door had to be at least 1.5 × 1.5 in area; the keys needed to enter the toilet had to be accessible (or there had to be support for a harmonised European wheelchair users key); the seat of the toilet basin had to be from 46 to 50 cm above the floor; there had to be at least 80 cm of space next to the toilet basin and at least 50 cm in front; the wash-basin had to be at a height that allowed a wheelchair to pass under it; the presence of features such as handrails was noted.

Parking: we distinguished between parking places reserved and ready for wheelchair users, i.e. those with appropriate lanes marked on the ground and relevant traffic signs, and parking places for general use. We also recorded the complete absence of parking spaces that could be in any way used by a wheelchair user.

Public transport accessibility: the accessibility of public transport was determined according to the level of the accessibility of tram, bus, and trolleybus stops. A stop was considered to be accessible if it allowed barrier-free access to all forms of public transport.

All the above-mentioned criteria and requirements were strictly followed for each mapped object. All results of the application of mapping criteria to objects are available as textual object descriptions within the printed atlas as well as in a form of object attributes for users of the developed Web (map) application. Any user may therefore explicitly see in advance the parameters of an object (s)he would like to visit.

The emphasis was placed on public institutions and cultural amenities such as theatres, museums, and galleries, which were covered in their entirety although many were not barrier-free. Other locations such as restaurants, cafes, shopping centres, banks, hotels, pharmacies and sport centres were included only if they were completely accessible. Attribute values were obtained through paper observation and then digitalised. The position was collected using PDA (Personal Digital Assistant) with a GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) receiver or smart phone.

Reference data were adopted from the Czech national Cadastral database. The coordinate system used is the Czech national S-JTSK with EPSG (European Petroleum Survey Group) code 5514, see http://epsg-registry.org/.

Accessibility data are presented as a thematic layer of the map. Thematic data are visualised by specially created map symbols presenting qualitative information, i.e. the type of the location, and quantitative information, i.e. the general level of accessibility. The type of location is visualised by a map symbol, and the level of accessibility is visualised by the symbol's colour.

The general style of map symbols – the representation of a wheelchair user on a coloured square background – was provided by the Prague Organisation of Wheelchair Users. The square format was used for all map symbols and was prepared in three different colours – green, orange and red – according to the general accessibility of the location. The pictogram of a wheelchair user was assigned to public institutions. Other pictograms were created for the Accessibility Guide to Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility (CitationBrno City Municipality, 2016). The style of these pictograms was unified with that of the wheelchair user.

The pictures inside the squares represent the type of location and were designed along conventional lines. For example, a theatre is presented by a face mask, while a restaurant is represented by a knife and fork.

The degree of accessibility is presented by the colour of the background square. The colour scheme corresponds to the traffic light colours used worldwide and is thus intuitively understandable to almost everyone. Accessible locations are symbolised by a green colour, orange is assigned to locations which are accessible with assistance, and inaccessible locations are represented by red. shows examples of map symbols for a theatre.

Figure 1. Map symbols representing theatres which are accessible, accessible with assistance, and inaccessible.

Base map layers originate from cadastral maps with a scale of 1:1000 and were adopted from the Brno City Municipality and the Institute of Computer Science of Masaryk University. They consist of buildings, streets, parks, water sources, railways, and roads. They are visualised in a conventional colour scheme and highlight cultural locations and churches. The reason for highlighting churches is that most wheelchair users use church towers and steeples as important points of orientation – as revealed by research at Masaryk University (CitationOsman, 2014). Cultural locations were highlighted because they are often the target destination for tourists.

Streets, public transport stops, and various other important locations were labelled. The style of labelling corresponds with the relevance of the label and the hierarchy of mapped locations. The placement of labels is shown in .

3. Conclusions

The development of the map ‘An Accessible Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility’, which is a part of the Accessibility Guide to Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility (CitationBrno City Municipality, 2016) took over three years. The process of mapmaking consisted of research in the field of accessibility mapping and preparation of the methodology, personal visits to all covered locations, the creation of map symbols, and map visualisation, as well as printing and the collection of feedback from users.

Accessibility information is very complex and it was not possible to present all relevant on the map. For this reason, the Accessibility Guide consists of a text part with detailed information about the accessibility of each location. There is also other information about accessibility represented by special pictograms adopted from the Prague Organisation of Wheelchair Users.

One of the main outcomes of the accessibility mapping of Brno city centre is a geodatabase of mapped locations which, in the last edition, 2016, consisted of 185 formally accessible or inaccessible locations from a total of almost 3000 mapped buildings in Brno city centre. Out of these185 locations on the map, 130 locations are accessible, 35 are accessible with assistance, and 20 are inaccessible. The geodatabase covers all relevant information about the accessibility of the location such as the general accessibility as well as detailed information about the entrance to the building, possibilities with respect to moving inside the building, and the existence of barrier-free toilets and parking spaces. The detailed description of barriers in the location is stored as attributes. Information about public transport stops is also available. In the city centre, there are 117 stops in total, 47 are completely barrier-free, 45 accessible with assistance, and 25 inaccessible. The developed database is also used in several other projects, where wheelchair users provide their feedback on locations, such as the Web-based interactive Brno Accessibility Map (http://gis.brno.cz/mapa/mapa-pristupnosti). The main advantages of the web application are (1) that periodic updates can easily be implemented and (2) the possibility of integration with other information resources. For instance, the web application allows the search for barrier-free public transport connections between two places directly in a map window. Such functionality is the result of cooperation between Masaryk University, Brno City Municipality, Brno Public Transport Authority, and the T-mapy company (an ESRI developer in the Czech Republic). The web application currently (March 2018) contains around 400 objects under the same categories as those defined in the printed version of the map presented in this paper. Details including accessibility level, address, and link to an interactive panoramic photograph (Google Street View as well as national Seznam Panorama) are available for each object. The web application is in line with the principles of so-called responsive design. Ongoing work aims at creating both interactive and paper versions of the Accessibility Guide for other (Czech) cities.

Successive editions of the Accessibility Guide were published in 2012, 2014, and 2016. The content of the new edition was updated, especially with respect to specific data on accessibility. The Guide was distributed free of charge to Brno City Municipality information points, and all copies were fully distributed within six months of publication. There were 4000 copies in the first and second editions in 2012 and 2014 and 2000 copies in the third edition in 2016, the smaller number denoting only a decrease in the printing budget rather than a decrease in demand. Thus, it may be assumed that the Guide is very useful for people with impaired mobility living in Brno or visiting as tourists. It is evident from the feedback that there is strong interest in the area of accessibility mapping with respect to cities.

Software

The map presented in this paper was created in ESRI ArcMap 10.4.1. During the accessibility mapping, ESRI ArcPad was used to obtain the GPS positions of locations. MS Excel was used to process data collected by paper survey.

Data

Accessibility data were acquired during the accessibility mapping. PDAs/smart phones with GNSS receivers were used to measure the positions of locations, and all attributes of accessibility were assessed by means of personal visits to each location. Attributes were also recorded by paper observation. During post-processing, the collected positional data were processed to features and the accessibility attributes were digitalised.

The base maps of streets, parks, water sources, railways and roads originating from cadastral maps with a scale of 1:1000 were provided by Brno City Municipality and the Institute of Computer Science of Masaryk University.

The created map presenting complex information about the accessibility of buildings in Brno city centre.

Download PDF (3.9 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Brno City Municipality for their support and for the accessibility mapping of locations displayed on the map. Theye also thank the Prague Organisation for Wheelchair Users for their support and for the use of their general symbol of a wheelchair user. They are also grateful to the organisation Liga vozíčkářů for their support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brown University. (University Support Services). Brown University Campus Accessibility Map. (2014). [Map]. Retrieved from http://www.brown.edu/Facilities/Facilities_Management/docs/DS-570R12_Front_18x28.pdf [Last accessed: 5 April 2017].

- Catalogue of accessible tourism products in Greenways in Spain and Portugal. European Greenways Association. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.viasverdes.com/pdf/CatalogoGW4ALL_ENG.pdf [Last accessed: 20 February 2018].

- City of Brno, Brno City Municipality. (2016). Accessibility Guide of Brno City Centre for People with Limited Mobility. Retrieved from https://www.brno.cz/fileadmin/user_upload/sprava_mesta/magistrat_mesta_brna/OVV/Publikace/Ostatni_publikace/OZ_Atlas_pristupnosti_centra_mesta_Brna.pdf. [Last accessed: 10 May 2017].

- ESRI. (Popovic, D. & Tedeschi, A.). (n. d.). Lisbon Wheelchair Map. [Map]. Retrieved from http://novagis.maps.arcgis.com/apps/View/index.html?appid=24b4aa61cf214a67aa461de1ee0f6c96 [Last accessed: 6 March 2017].

- Guía Tecnica y de Diseño Sobre Accesibilad en Vías Verdes [Technical and Design Guide on Greenways Accessibility]. (2018). PREDIF - Plataforma Representativa Estatal de Personas con Discapacidad Física. Retrieved from http://www.viasverdes.com/vvandalucia/pdf/GuiaTecnicaAccesibilidad-ViasVerdes.pdf [Last accessed: 20 February 2018].

- Havlas, J. (2011). Kartografické vyjádření mobility vozíčkářů v rámci brněnské MHD [Accessibility map of Brno for wheelchair bounds - theoretical approaches and practical solution]. (Masteŕs thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- Herman, L., & Reznik, T. (2013). Web 3D visualization of noise mapping for extended INSPIRE buildings model. Environmental Software Systems: Fostering Information Sharing (IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology), 413, 414–424.

- Jaňura, J. (2011). Geografická analýza přístupnosti města brna pro vozíčkáře [Geographical accessibility of Brno city center for wheelchair users]. (Unpublished masteŕs thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- King Country Metro. (n.d.). Downtown Seattle Accessible Map and Transit Guide. [Map]. Retrieved from http://metro.kingcounty.gov/tops/accessible/riding-the-bus/seattle-accessibility.html [Last accessed: 15 May 2017].

- Kumparak, G. (2016, December 16). Google Map now notes of the location is wheelchair accessible. TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2016/12/16/google-maps-now-notes-if-a-location-is-wheelchair-accessible/ [Last accessed: 15 May 2017].

- Minneapolis City by Nature. (2014). Accessibility Guide. Retrieved from at <http://www.minneapolis.org/?ACT=25&fid=5&d=151&f=accessibility_guide_2014.pdf. [Last accessed: 10 April 2017].

- Mulicek, O., Osman, R., & Seidenglanz, R. (2013). The imagination and representation of space in everyday experience. Sociologicky Casopis-Czech Sociological Review, 45(5), 781–809.

- Notice 398/2009 Sb. (2009). Vyhláška 398/2009 Sb. o obecných technických požadavcích zabezpečujících bezbariérové užívání staveb [Notice about technical requirements for barrier – free buildings]. Ministry of Regional Development CZ. https://www.mmr.cz/getmedia/f015224c-ff91-4cad-a37b-dc0dc1072946/Vyhlaska-MMR-398_2009. [Last accessed: 10 May 2017].

- Osman, R. (2014). Městská teritorialita na příkladu města brna [Territoriality in a city: the case of Brno]. (PhD. thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- Prazska organizace vozickaru [in English Prague Organisation of Wheelchair Users, civic association]. (2010). Prague Heritage Reservation – Accessibility Atlas for People. 80 pages.

- Reznik, T. (2013). Geographic information in the age of the INSPIRE directive: Discovery, download and use for geographical research. Geografie, 118(1), 77–93.

- Reznik, T., Horakova, B., & Szturc, R. (2015). Advanced methods of cell phone localization for crisis and emergency management applications. International Journal of Digital Earth, 8(4), 259–272. doi: 10.1080/17538947.2013.860197

- Sháněl, J. (2016). Webová publikace atlasu přístupnosti centra města brna [Web publishing of the Brno city centre accessibility guide] (Bacheloŕs thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- Stachoň, Z., Kubíček, P., Štampach, R., Herman, L., Russnák, J., & Konečný, M. (2016). Cartographic principles for standardized cartographic visualization for crisis management community. In T. Bandrova & M. Konecny (Eds.), Proceedings, 6th international conference on cartography and GIS ( Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, pp. 781–788). Sofia: Bulgarian Cartographic Association.

- Stehlíková, J. (2012). Mapa přístupnosti města brna pro vozíčkáře - teoretická východiska a vlastní řešení [Accessibility map of Brno for wheelchair bounds - theoretical approaches and practical solution]. (Masteŕs thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- Stehlíková, J. (2018). Mapování přístupnosti pro pohybově postižené [Accessibility mapping for people with impaired mobility]. (Unpublished PhD. thesis). Masaryk University. Faculty of Science. Department of Geography, Brno.

- Štampach, R., Kubíček, P., & Herman, L. (2015). Dynamic visualization of sensor measurements: Context based approach. Quaestiones Geographicae, 34(3), 117–128. doi: 10.1515/quageo-2015-0020

- Štampach, R., & Mulíčková, E. (2016). Automated generation of tactile maps. Journal of Maps, 12, 532–540. doi: 10.1080/17445647.2016.1196622

- The University of Kansas. (n.d.). (ADA Resources Center for Equity and Accessibility). Accessibility Map | Student Access Services. [Map]. Retrieved from https://access.ku.edu/accessibility-map. [Last accessed: 5 April 2017].

- Yang, D., Sheng, W. H., & Zeng, R. L. (2015). Indoor human localization using PIR sensors and accessibility Map. 2015 IEEE international conference on cyber technology in automation, control, and intelligent systems (CYBER), IEEE annual international conference on cyber technology in automation control and intelligent systems, IEEE, pp. 577–581.