ABSTRACT

Landscape has always been the focus of artistic interest. Landscape is also the object of research interest of geographers, and it offers a field for cooperation between art and geography. Our study focuses on landscape painting as an important source in identifying landscape changes. We focused on discovering the location where the painter placed his canvas. We used Czech landscape paintings from the end of the nineteenth century in the Iron Mountains. We have combined information about paintings and their authors with terrain analysis in GIS. We have carried out field research and consulted a painter to localise the locations where the landscapes were painted. Main map depicts the sites of selected landscape paintings from where the painters captured the image of the landscape. Our proposed combination of terrain analysis with the information about the paintings and the painters is a convenient way to identify the sites of the paintings.

1. Introduction

Landscape is a central concept and an object of study in many disciplines, from the natural sciences through to the humanities and the arts. Whether landscape is seen as part of a tangible world or as an abstract entity that contains everything and so is more closely related to a social construct than to reality, it creates a broad interdisciplinary realm where different fields of enquiry may encounter each other. For scientists, the landscape is a constant source of inspiration and knowledge; a thought-provoking, endless puzzle whose laws they try to unravel. Landscape is also an unlimited source of inspiration for artists. It can affect them strongly through its material forms and overall compositions, as well as through the impressions, moods and emotions evoked in the artists. Thus, landscape becomes a platform where natural science, humanities and the arts can cooperate and integrate.

Landscape painting is significant for geoscientists as it reflects the relationship between reality and an artist’s experiences. In his magnum opus Ansichten der Natur, Alexander von Humboldt introduced the concept of landscape and looked for the ideal balance between the objective reality of the world and the aesthetic impressions of the traveller (CitationMinca, 2007). Leon Battista Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci were among the first artists to utilise perspective in their work (which facilitated the formation of landscape painting), and would probably see painting as an exact science based on mathematics and the observation of nature (CitationCosgrove, 1985). In the past, geosciences were positively inclined towards landscape painting, as can be seen in the mutual inspiration of art and geology in the second half of the nineteenth century (CitationWagner & Ruskin, 1988). This relationship was rather weakened with the rise of critical positivistic science, which was followed by a more intense and fruitful period leading up to recent decades, and which was reflected in the manner of education in geosciences (Nordstrom & Jackson, Citation2001; CitationPestrong, 1994; CitationRomey, 2000).

Geography (as a sub-discipline of geosciences) has always had a close relationship with the visual arts as they are the most commonly used tools of geographical expression. This includes maps, plans and drafts, which can all be seen as forms of art (CitationDaniels, 1984). The first map creators and landscape painters were usually the same people (Rees, Citation1980). Moreover, geography and landscape painting have the same study object – the landscape (CitationRees, 1973). Geographers' interest in landscape painting was originally connected to its ‘exotic nature’; old paintings were used as visual representations of a studied space if no photographs were available (CitationWallach, 1997). In modern and later post-modern geography, landscape paintings were used to interpret the history of the landscape and to subsequently reveal its hidden symbolism by semiotic and hermeneutical means (CitationWhyte, 2002). Through these approaches, geographers can view images as silent witnesses to the period they portray; the landscape of the past. Or they can be representations (symbols) of the promotion of a certain political power, social order, mindset or interests (Daniels, Citation1988; CitationMcGregor, 2003). However, both these approaches lead to a certain dialectic, as pointed out by CitationWallach (1997). It can be called a ‘slippery reality’, where an image is perceived either in extreme positions as a sterile and undistorted picture of a real historic landscape, or as a set of symbols and clichés with many hidden meanings which all testify to anything except the depicted reality. Both these extreme approaches are significantly eclectic and somewhat resigned to the fact that painterś artistic depictions of the landscape combine reality with emotion and are a reaction to the overall social or artistic style of the period. Phenomenological philosopher CitationMerleau-Ponty (2004) stated that the scientific idea of an objective world, described only by physical laws and empirical observations, is misleading. Every observation depends on the status of the observer. Merleau-Ponty mentioned modern painters because they offered a new way of seeing; a break with the traditional laws of perspective and classical landscape painting with its ‘gaze fixed in infinity’. He appreciates painters who depict objects seen from several points of view at once, because of ‘the nature of the real to compress into each of its instants an infinity of relations’ (CitationMerleau-Ponty, 1981, p. 323). The view of landscape through the eyes of painters connects the physical structures of the world with perception and the world of the senses. Landscape is shaped by the human view, but real time and place are part of it too (CitationTomášek, 2016).

Generally, visual art is a valuable resource for geographers and its use for the purposes of human and physical geography is growing (CitationHawkins, 2013). Old landscape paintings can be used in studies related to changes in the environment (CitationDaniels, 1984; CitationLavery, 2017). Historical landscape paintings can be utilised in three different ways for such purposes (CitationRees, 1973): (1) as visual records of historical landscape; (2) as forms of expression of the relationship between humans and nature; or (3) as determinants of our perception and understanding of the environment. Various applications of such approaches can be found in the studies of CitationPrince (1988), CitationRees (1982), CitationSmout (1996), CitationEwald (2001), CitationNordstrom and Jackson (2001), CitationLacina and Halas (2015), CitationBainbridge (2017), CitationLavery (2017) and CitationRay (2017). However, the issues of scale and purpose are very important. If our aim is to demonstrate general changes in the landscape or the way they are depicted in paintings, then the particular location of the origin of the painting is not important; it is rather the landscape and the period it represents. However, if we move to a lower spatial level we come to a particular landscape, a particular place that has been portrayed by an artist and has changed over time. Therefore, it is necessary to know the approximate location of the painter and his canvas. A particular landscape can be viewed from different angles, heights and perspectives. It is remarkable that the problem of a painting’s localisation has had limited study in both geographical and artistic work. The reason could be the massive transformation of the landscape connected with urbanisation and the destruction of the original landscape, as shown in the study by CitationBos (2015). He photographed modern landscapes that had been depicted in classic works by Dutch painters. Searching for a location where a painter placed his/her canvas, with respect to the focal views and focal points of the painting, is complicated, laborious and time consuming (CitationLacina & Halas, 2015). However, the use of a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) within a Geographical Information System (GIS) provides a simulation of the visibility of terrain features from particular locations. With information about painters and their paintings, we can reconstruct the field of view of landscape paintings and compare them to current and old maps to reveal how the landscape seen through the eye of the painter is represented from the (bird’s eye view) perspective of cartography. This is significant because many geographical studies deal with comparisons and analyses of historical and contemporary landscapes, and they use current and old maps. Studies on the development of land use/land cover (CitationHavlíček, Pavelková, Frajer, & Skokanová, 2014; Kopp, Frajer, & Pavelková, Citation2015; CitationSkaloš et al., 2011) are the most widely represented. Despite debate over the objectivity of maps, they are considered to be passive and empirical reflections of the reality of the landscape. But this reality is generalised and divided into points, lines and polygons, which can only be read by using the map’s legend. Using landscape paintings or photographs can reveal a historical landscape in a more familiar and ‘plastic’ view.

The main aim of this study is to find the precise locations at which the painters of the late nineteenth century depicted the Czech landscape and also to record the focal view of their paintings. Selected case studies will illustrate how finding these locations can be helpful in the study of landscape change.

2. Definition of the area of interest and its connection with painters

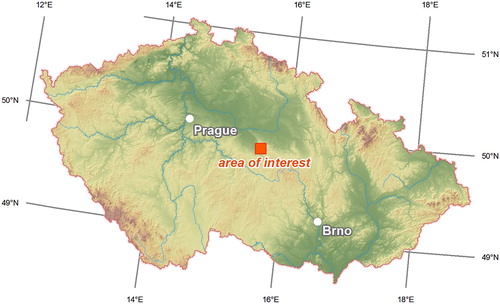

The Iron Mountains, part of the Českomoravská Highlands in the centre of the Czech Republic, have been selected as the area of interest (). The landscape of the Iron Mountains is an interesting mosaic of fields, meadows and forests. The dominant ridges (Chvaletická pahorkatina and Kaňkovy mountains) have fault slopes oriented to the south west where they drop 220 m to the Středolabská plateau (CitationDemek & Mackovčin, 2014). The ridges, together with deep valleys of two rivers (the Doubrava and the Chrudimka), create a visually interesting georelief. In addition, there is a varied geological composition and an agrarian landscape of picturesque villages and ruins of medieval castles. This was a virtually ideal combination for the inspiration of landscape painters at the end of the nineteenth century. Owing to its unique combination of preserved natural ecosystems and rural settlements the area was declared a Protected Landscape Area (284 km2) in 1991 and the National Geopark (778 km2) was formed in 2010.

Figure 1. The area of interest within the Czech Republic. Sources: © ArcČR, ARCDATA PRAHA, ZÚ, ČSÚ, 2016 (processing by the authors).

The Iron Mountains have special significance for Czech landscape painting. In 1847, the painter Antonín Chittussi was born in Ronov nad Doubravou in the foothills of the Iron Mountains. He had a study trip to France in 1879 (CitationSejček, 2006) where he encountered the Barbizone School of landscape painting which, like the Dutch Hague school, focused on plein-air painting and the depiction of the real landscape and its immediate specific atmosphere (Norman, Citation1977). Upon his return, Chittussi started his impressionistic paintings in the spirit of the Barbizone School. He searched for motifs in the landscape of his birth, the Iron Mountains. Chittussi shifted Czech landscape painting to a new dimension, because at that time the focus was on romantic paintings, which were mostly created in studios and contained a number of stylised and symbolic structures. Chittussi refused to paint the arranged romantic motifs of medieval castles at sunset, and instead chose realistic themes from plein-air. He was followed by his younger colleagues from the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, who were impressed with his landscape paintings from the Iron Mountains. František Kaván (1866–1941) tended towards realism and he was fascinated by Chittussís paintings of the mountain ridges. He travelled to the region with his friend Bohuslav Dvořák (1867–1951) in order to paint, as did Antonín Slavíček (1870–1910) and Oldřich Blažíček (1887–1953), famous Czech impressionists. Another painter from that generation of artists was Jindřich Prucha (1886–1914). He lived in the region of the Iron Mountains, and since his youth had been inspired by Chittussi and later by Antonín Slavíček.

3. Methods

3.1. Selection of landscape paintings

The first step was the selection of paintings by the above-mentioned painters from the end of the nineteenth century. The painters who partly focused on landscape scenery and not only on individual structures (e.g. buildings) or entire residential areas in municipalities were preferred. The art style did not matter in the present study (in this case, it included realism, impressionism, expressionism and fauvism). Reproductions of individual artworks were acquired from regional monographs devoted to the individual painters, from exhibition catalogues, private collections and the internet, where a number of photographs of the artworks can be found due to the expired copyright. The paintings and the painters are listed in .

Table 1. List of analysed landscape paintings.

3.2. Identifying the locations of landscape paintings

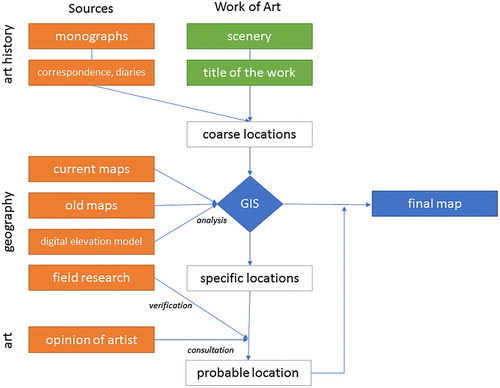

The search for the sites where the painters created their landscape paintings was undertaken in several stages (). The rough specification of the area where the painting might have been produced was the first stage. As pointed out by CitationPrince (1988), this can be achieved with the help of the title of the painting (content place name or other topographic information) or the painting itself, if it contains an identifiable natural or cultural landmark. If this is not the case and the name of the painting is very general or specific, or depicts a landscape without identifiable landmarks, it is necessary to use detailed information from a secondary sources (e.g. CitationSejček, 2006; CitationŠeveček, 1976; CitationZachař, 2011; CitationZemina & Sejček, 2004), or to refer to the painter’s letters, diaries and memoirs; for example, as published in CitationSejček (1988) and CitationOrlíková and Hlaváčková (2004).

Following the rough specification of the area, a more particular specification of the potential sites where the painting might have been painted was established. We used the current base maps of the Czech Republic with scales from 1:10,000 to 1:25,000 as issued by the Czech Office for Surveying, Mapping and Cadastre (ČÚZK) and the 3rd Military Survey (1:25,000), which showed the form of the landscape in the last third of the nineteenth century (1877–1880). The basis was some distinctive landscape features such as buildings, watercourses, forests, mountain ridges, peaks, rocks and the ruins of castles.

The potential sites for the paintings were determined using a GIS tool for analysing the terrain of the Czech Republic (geoportal.cuzk.cz) with the latest DEM of the Czech Republic. The visual fields (or ‘view horizons’) were analysed from individual sites. These fields are the potential areas that the painters could see from the sites (1.5 m above the current terrain was selected as the base height i.e. the rough level of the painters’ eyes). We assumed that the relief had not changed significantly as the landscape is not as urbanised or affected by mining as other regions in the Czech Republic (CitationHendrychová & Kabrna, 2016). Terrain analyses in relation to art have been successfully utilised in research into rock art in Britain (CitationFairen-Jimenez, 2007) and Argentina (CitationMagnin, 2013) as well as in the reconstruction of the visual view of the ancient fort in Chittledroog (CitationNalini & Rajani, 2012). The results were then exported to a shapefile in order to be processed using Esri ArcGIS 10.4.

The final stage in determining where the painters had depicted their scenery was the correction. This involved a comparison of individual sites and view horizons with what is clear from the relief in the paintings, thus enabling the painteŕs position to be located more precisely. The last, though important, part of the work was a consultation and a correction of the resulting sites with an ‘insider’. Academic painter Zdeněk Sejček (born 1926) is a leading Czech expert on the painters of the Iron Mountains (especially A. Chittussi and J. Prucha). He is also a painter and is active in the region. A triangle representing the field of view of each painting was created from the location of the painter and the limit points of the painting’s view horizon. The sites of the selected paintings were also photographed and visited during the terrain research, as in the studies of CitationBos (2015) and CitationLacina and Halas (2015).

3.2.1. An example of identifying the location of a landscape painting

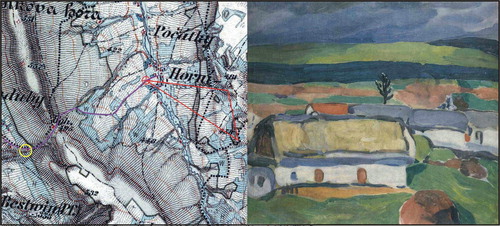

As an example of applying our procedure, as outlined in , we chose a painting by Jindřich Prucha from 1911, entitled ‘Before the Storm’ (alternatively entitled ‘Spring in the Iron Mountains’ – see ). It is an expressionistic or fauvistic painting with a schematic landscape that makes localisation difficult. The alternative title of the painting refers to the Iron Mountains, though not to any particular site. The monograph by CitationSejček (2006) also gives another name ‘Počátky’, which refers to the village where Prucha painted most of his paintings. The painting itself shows a view of the village and the slope on the other side of the valley with a mosaic of fields, meadows and woods. The woods are depicted schematically with the use of green paint. It creates a continuous belt on the slope, above which there are other fields and meadows on the right side of the view horizon, complete with another belt of woods. If we look at a map by the 3rd Military Survey of 1877, we find belts of alternating woods and fields only east of the village Počátky. Thus, the painter's view was eastwards. He had to paint from an elevated place in order to depict the village in the valley as well as the slope on the horizon. The opposite slope in the west above the village seems opportune. It was in this direction that the dirt road led from Pruchas over the ridge of the Iron Mountains to Pruchás home. So it is highly probable that the painting was painted from this road. An analysis of visibility confirmed that it was possible to locate the canvas above the last house of the village by the road leading towards the mountains.

Figure 3. Identification of the location of the painting ‘Before the Storm’ (Jindřich Prucha) on the old map. (Yellow circle = home of the painter, purple line = path through the mountain ridge, red cross = position of painter, red line = view horizon). Sources: 3rd Military Survey © Geoinformatics Laboratory, University of J. E. Purkyne; © Ministry of Environment of the Czech Republic; Photograph © National Gallery in Prague (2017).

3.3. Analysis of landscape changes

Two paintings by A. Chittussi (both painted in 1887) were selected as case studies to analyse landscape changes. First, according to the traditional geographical approach, we focused on changes in land use. Maps of current and historical land use (based on current maps and the aforementioned 3rd Military Survey maps) were used for the individual view horizons of the paintings. These Military Survey maps are widely used in the study of historical land use (CitationHavlíček et al., 2014; CitationSkaloš et al., 2011; CitationSkaloš, Engstová, Trpáková, Šantrůčková, & Podrázský, 2012). For the next step, we compared landscape paintings with current photographs of the places and recorded the changes.

4. Results and discussion

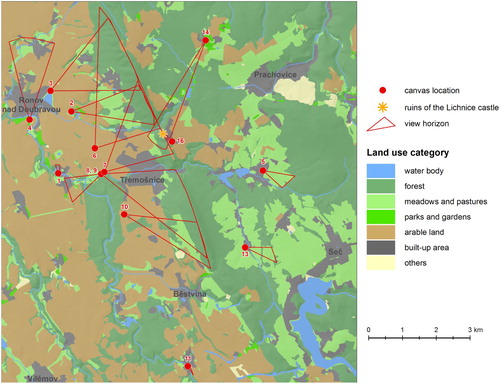

Using our procedure (), we managed to identify the location for 14 out of 16 landscape paintings of the Iron Mountains (). The paintings ‘Goat’s ridges’ and ‘Landscape near Počátky’ were not identified; they refer to the location of the painting topographically but the landscapes lack significant features that would enable a more precise localisation. The analysis of the view horizons displayed on reveals that the ridges of the Iron Mountains were most often depicted, along with the dominant castle of Lichnice. The combination of image sceneries and visibility field analyses based on the DEM proved to be useful in revealing the painters’ locations. Thus, combining GIS and artwork can bring a new dimension to their localisation (CitationBarnett & Guagnin, 2014; CitationFairen-Jimenez, 2007; CitationMagnin, 2013).

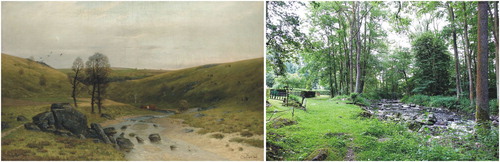

The results of land use analyses of the scenes in the researched paintings (as shown in the Main Map) show that general land use has hardly changed in the Iron Mountains since the end of the nineteenth century. However, this is a map-based analysis where the relief surface is ‘artificially’ classified into several land use categories. Landscape paintings allow us to go beyond this perspective, and in combination with current photographs we can capture even minor changes that are difficult to find in other sources (Nordstrom & Jackson, Citation2001). Comparing the image of A. Chittusi’s ‘Drowned man pond’ with the present situation (see main map, painting B), we find changes in the landscape structure, as in the mid-twentieth century the original mosaic of small fields and meadows held by peasants was converted to large-scale collective openfield agriculture as part of the transition to the Soviet-type system of farming (CitationSkaloš, Molnárová, & Kottová, 2012). The nineteenth century landscape was also more used by people and there were few unused areas. There are many abandoned areas in the current landscape that are not used intensively and in which new wilderness areas develop (CitationLipský, 2010). However, new linear structures such as roads and power lines have entered the landscape and they disturb the original landscape scenery (CitationCoch, Gerhards, & Konold, 2005). The growing areal structures (CitationStachura, Chuman, & Šefrna, 2016) make the landscape less penetrable, less clear. This has a negative impact on the potential search for sites in the terrain and acquiring comparative photo-documentation is complex. Many of the listed paintings were painted in valleys and alluvial plains that were used in hay-making or for grazing at the end of the nineteenth century. Currently, they are overgrown with wild vegetation which increases their ecological value, but means that the scenes in the paintings have been changed ().

Figure 5. Original and current scenery from Chittussi's painting ‘From the Doubrava Valley’ (1884). Sources: Photograph © National Gallery in Prague (2017).

We can also theorise about how the artistic depiction of the landscape is influenced by the physical world and by the personality of the artist. In this respect, our consultations with Zdeněk Sejček, leading expert on the painters of the Iron Mountains, were essential. The objectively judged or derived sites from where the painters depicted their works gained a wider context. There were many practical factors that we did not realise. First, the painter’s choice of location was to satisfy their artistic side but at the same time the location commonly was a convenient distance from the painter's place of residence as the equipment was difficult to carry for long distances. For this reason, painters typically chose locations close to villages or paved paths. For example, Antonín Slavíček painted several scenes of the hill in front of his rented house in the village of Kameničky. Similiarly, two of František Kaván’s paintings from the Iron Mountains (‘On the Golden brook’ and ‘Golden brook’), were painted at the same location; he just rotated the canvas stand. Second, a very important point was that individual painters inspired each other and visited the same or similar locations as their predecessors. Jindřich Prucha created one of his first paintings ‘Doubrava river at Spačice’ in 1906 based on Chittussís ‘From the Doubrava Valley’, but in a different part of the river valley (perhaps he didńt know the exact location of Chittussi's painting). He returned to this scenery again in 1913.

The content of the paintings and their scenes also may have been influenced by previous painters or the requirements and roles of their donors (CitationConstantine, 2001). We found that some paintings were listed under different names in different sources because painters usually did not name their works. They were only named in galleries or auction houses, which may also be misleading when trying to identify the location of the scenes.

5. Conclusion

We can conclude, in accordance with CitationHawkins (2013), that the connection of geography and art has great potential for collaboration, especially in the fields of environmental and human geography, where we have noticed a large number of references to painters in recent decades (CitationWallach, 1997). It is mainly the landscape plein-air paintings that can provide us with a large amount of useful information about the historical landscape. They enable us to enter landscapes which we only know from historical descriptions or cartographic representations in old or reconstructed maps CitationTuan (1977, p. 123). states, in connection to the comparison with maps: ‘The landscape picture, with its objects organized around a focal point of converging sightlines, is much closer to the human way of looking at the world … ’. That is how we need to treat landscape pictures and we need to consider that every human perceives the world differently and perceptions can be distorted. However, if we want to use landscape paintings to enter a specific landscape at a specific time, it is necessary to know the precise place the landscape was depicted, and this was the main focus of our study. We compiled written resources about the lives of the painters, carried out analyses of a DEM within a GIS, as well as field research and consultations with a regionally-renowned artist for the purpose of correction. We have shown that although some of the depicted scenes cannot be identified due to landscape development, we can determine the location of the sites through the identification of dominant features in paintings and by analysing the georelief. By using a GIS we can determine the sites where the paintings were, in all likelihood, painted.

Software

For the creation of the DEM, an online application ‘Altitude analysis’ was used (http://ags.cuzk.cz/dmr/). The chart and scheme were created using MS Excel 2010. All other operations, including the creation of the Main Map, were carried out using Esri ArcGIS 10.4.

Main map

Download PDF (3.8 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors of the study would like to thank the painter Zdeněk Sejček for consultations and the use of his large private archive. We also thank the National Gallery in Prague for providing us with necessary paintings. The authors would also like to express their thanks to all reviewers for their valuable remarks and recommendations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jindřich Frajer http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0817-3128

Petr Šimáček http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9348-1357

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bainbridge, W. (2017). Titian country: Josiah Gilbert (1814–1893) and the Dolomite Mountains. Journal of Historical Geography, 56, 22–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhg.2016.12.006

- Barnett, T., & Guagnin, M. (2014). Changing places: Rock art and Holocene landscapes in the Wadi al-Ajal, South-West Libya. Journal of African Archaeology, 12, 165–182. doi: 10.3213/2191-5784-10258

- Bos, E. (2015). Landscape painting adding a cultural value to the Dutch countryside. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.culher.2013.12.008

- Coch, T., Gerhards, I., & Konold, W. (2005). Cuts or connections? Overhead power lines running through landscapes. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 14, 139–143. doi: 10.14512/gaia.14.2.15

- Constantine, S. (2001). The Barbizon painters: A guide to their suppliers. Studies in Conservation, 46, 49–67. doi: 10.2307/1506882

- Cosgrove, D. (1985). Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 10, 45–62. doi: 10.2307/622249

- Daniels, S. (1984). Human geography and the art of David Cox. Landscape Research, 9, 14–19. doi: 10.1080/01426398408706118

- Daniels, S. (1988). The political iconography of Woodland in later Georgian England. In S. Daniels, & D. Cosgrove (Eds.), The iconography of landscape (pp. 43–83). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Demek, J., & Mackovčin, P. (Eds.). (2014). Zeměpisný lexikon ČR: Hory a nížiny [Geographical lexicon of the Czech Republic: Mountains and lowlands]. Brno: Mendel University.

- Ewald, K. C. (2001). The neglect of aesthetics in landscape planning in Switzerland. Landscape and Urban Planning, 54, 255–266. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(01)00140-2

- Fairen-Jimenez, S. (2007). British neolithic rock art in its landscape. Journal of Field Archaeology, 32, 283–295. doi: 10.1179/009346907791071584

- Havlíček, M., Pavelková, R., Frajer, J., & Skokanová, H. (2014). The long-term development of water bodies in the context of land use: The case of the Kyjovka and Trkmanka River Basins (Czech Republic). Moravian Geographical Reports, 22, 39–50. doi: 10.1515/mgr-2014-0022

- Hawkins, H. (2013). Geography and art. An expanding field site, the body and practice. Progress in Human Geography, 37, 52–71. doi: 10.1177/0309132512442865

- Hendrychová, M., & Kabrna, M. (2016). An analysis of 200-year-long changes in a landscape affected by large-scale surface coal mining: History, present and future. Applied Geography, 74, 151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2016.07.009

- Kopp, J., Frajer, J., & Pavelková, R. (2015). Driving forces of the development of suburban landscape – a case study of the Sulkov site west of Pilsen. Quaestiones Geographicae, 34, 51–64. doi:10.1515/quageo-2015-0028

- Lacina, J., & Halas, P. (2015). Landscape painting in evaluation of changes in landscape. Journal of Landscape Ecology, 8, 60–68. doi: 10.1515/jlecol-2015-0009

- Lavery, H. J. (2017). Australian landscape art as a contributor to environmental management planning at Berrys Bay (Sydney Harbour). Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 24, 261–275. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2017.1310061

- Lipský, Z. (2010). Present changes in European rural landscapes. In J. Anděl (Eds.), Landscape modelling. Urban and Landscape Perspectives 8 (pp. 13–27). Springer Netherlands. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3052-8_2

- Magnin, L. A. (2013). Where to paint? A comparative GIS analysis as an approach to human decision making. Magallania, 41, 193–210. doi: 10.4067/S0718-22442013000100010

- McGregor, J. (2003). The Victoria Falls 1900–1940: Landscape, tourism and the geographical imagination. Journal of Southern African Studies, 29, 717–737.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1981). Phenomenology of perception. New York: Routledge.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2004). The world of perception. New York: Routledge.

- Minca, C. (2007). Humboldt’s compromise, or forgotten geographies of landscape. Progress in Human Geography, 31(2), 179–193. doi: 10.1177/0309132507075368

- Nalini, N. S., & Rajani, M. B. (2012). Stone fortress of Chitledroog: Visualizing old landscape of Chitradurga by integrating spatial information from multiple sources. Current Science, 103, 381–387.

- Nordstrom, K. F., & Jackson, N. L. (2001). Using paintings for problem-solving and teaching physical geography: Examples from a course in coastal management. Journal of Geography, 100, 141–151. doi: 10.1080/00221340108978441

- Norman, G. (1977). Nineteenth-century painters and painting: A dictionary. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Orlíková, J., & Hlaváčková, M. (2004). Antonín Slavíček (1870–1910). Gallery: Prague.

- Pestrong, P. (1994). Geosciences and the arts. Journal of Geological Education, 42, 249–257. doi: 10.5408/0022-1368-42.3.249

- Prince, H. (1988). Art and Agrarian change, 1710–1815. In S. Daniels, & D. Cosgrove (Eds.), The iconography of landscape (pp. 43–83). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ray, S. (2017). Hydroaesthetics in the little ice age: Theology, artistic cultures and environmental transformation in early modern Braj, c. 1560–70. South Asia: Journal of South Asia Studies, 40, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1208320

- Rees, J. (1973). Geography and landscape painting: An introduction to a neglected field. Scottish Geographical Magazine, 89, 147–157. doi: 10.1080/00369227308736255

- Rees, R. (1980). Historical links between cartography and art. Geographical Review, 70, 60–78. doi:10.2307/214368

- Rees, J. (1982). Constable, Turner, and views of nature in the 19th century. Geographical Review, 72, 253–269. doi: 10.2307/214526

- Romey, W. D. (2000). Using patterns, icons, abstractions, and metaphors from art in geoscience classes. Journal of Geoscience Education, 48, 295–356. doi: 10.5408/1089-9995-48.3.295

- Sejček, Z. (1988). Jindřich Prucha v dopisech a vzpomínkách [Jindrich Prucha in the letters and memories]. Praha: Odeon.

- Sejček, Z. (2006). Klasikové české krajinomalby v Železných horách [Classic landscape painters in the Iron Mountains]. Společnost přátel Železných hor, Grantis: Heřmanův městec, Ronov nad Doubravou.

- Ševeček, L. (1976). Antonín Chittussi (1847–1891). Gottwaldov: Propagační tvorba Brno.

- Skaloš, J., Engstová, B., Trpáková, I., Šantrůčková, M., & Podrázský, V. (2012). Long-term changes in forest cover 1780–2007 in central Bohemia, Czech Republic. European Journal of Forest Research, 131, 871–884. doi: 10.1007/s10342-011-0560-y

- Skaloš, J., Molnárová, K., & Kottová, P. (2012). Land reforms reflected in the farming landscape in East Bohemia and in Southern Sweden – two faces of modernisation. Applied Geography, 35, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.003

- Skaloš, J., Weber, M., Lipský, Z., Trpáková, I., Šantrůčková, M., Uhlířová, L., & Kukla, P. (2011). Using old military survey maps and orthophotograph maps to analyse long-term land cover changes – case study (Czech Republic). Applied Geography, 31, 426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.10.004

- Smout, C. (1996). Pre-improvement fields in upland Scotland: The case of Loch Tayside. Landscape History, 18, 47–55. doi: 10.1080/01433768.1996.10594483

- Stachura, J., Chuman, T., & Šefrna, L. (2016). Development of soil consumption driven by urbanization and pattern of built-up areas in Prague periphery since the 19th century. Soil & Water Research, 10, 252–261. doi: 10.17221/204/2014-SWR

- Tomášek, M. (2016). Krajiny tvořené slovy. K topologii české literatury 19. století [Landscapes formed by words: On the topology of 19th-century Czech literature]. Dokořán: Ostravská univerzita.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1977). Space and place. The perspective of experience. Minnesota: University of Minnesota.

- Wagner, V. L., & Ruskin, J. (1988). John Ruskin and artistical geology in America. Winterthur Portfolio, 23, 151–167. doi: 10.1086/496374

- Wallach, B. (1997). Painting, art history, and geography. Geographical Review, 87, 92–99. doi: 10.2307/215660

- Whyte, I. D. (2002). Landscape and history since 1500. London: Reaktion Books.

- Zachař, M. (2011). František Kaván/Hvězda Mařákovy školy [František Kaván/the star of the Mařák´s school]. Roudnice nad Labem: Galerie moderního umění v Roudnici nad Labem.

- Zemina, J., & Sejček, Z. (2004). Jindřich Prucha malby a kresby z let 1907–1914 [Jindřich Prucha Paintings and drawings from 1907–1914]. Litoměřice: Severočeská galerie výtvarného umění.