ABSTRACT

The Gunbower Yemurriki Map details important information about Barapa Country and Barapa people for the purpose of education. The Barapa are the Traditional Owners of the lands north and south of the Murray River around Cohuna, Australia and are working with natural resource agencies to identify and map cultural assets on traditional lands, particularly in relation to water resources. The Gunbower Yemurriki Map has been developed through participatory cultural mapping processes to demonstrate the community connection to water and the wider cultural landscape. Yemurriki is the Barapa word for Country. The map developed and presented in this study will be used to educate the local non-indigenous community about Barapa cultural values and to act as a teaching aid for younger Barapa people. The map depicts stories, totems, and places identified within the landscape. All the information included is what the Barapa consider public and educational.

1. Introduction

Cultural mapping is an activity conducted for, with, or by traditional, indigenous, minority and local communities to identify assets that are not widely included in mainstream mapping (CitationBlack, 2000; CitationChapin, Lamb, & Threlkeld, 2005; CitationHerlihy & Knapp, 2003). Cultural mapping can be used to examine the social values of communities (CitationBrown & Raymond, 2007; CitationCorbett & Rambaldi, 2009). It is conducted for a range of reasons including (but not limited to) the identification of natural resources, defining traditional boundaries, religion, and providing cultural learning between generations (CitationBrennan-Horley, Luckman, Gibson, & Willoughby-Smith, 2010; CitationCorbett & Rambaldi, 2009).

Cultural mapping is one way for indigenous communities to promote their political goals regarding land claims and participate in decolonisation through spatial information (CitationBryan, 2009; CitationHarley, 2009; CitationHerlihy & Knapp, 2003). For the purpose of the map developed, decolonisation is the ability to present information that has been approved in a way which is culturally appropriate for the community (CitationDudgeon & Walker, 2015). In this map, decolonisation is supported by the minimal use of non-indigenous spatial data, the consultative development process, and the approved use of Indigenous information. Cultural mapping also facilitates cross-cultural education through sharing indigenous values, history, and perspectives with the broader community (CitationCorbett & Rambaldi, 2009).

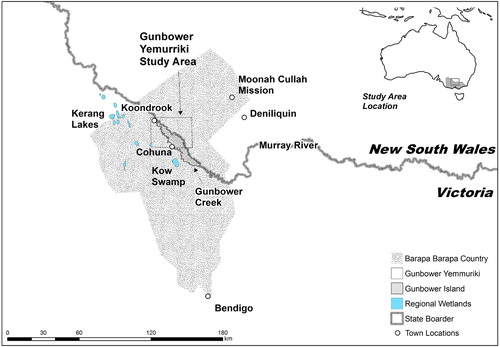

The Barapa are the Traditional Owners of the lands north and south of the Murray River around Cohuna, in south-eastern Australia (). For the Barapa, this map is a way of informing others of their values and on-going presence. The purpose of creating the Gunbower Yemurriki map is three-fold: (1) Educate non-Indigenous people about Barapa cultural values (and any associated benefits for Barapa people which will come from that education), (2) represent the values of Barapa Country on Gunbower Island as well as some associated but spatially distant locations, and (3) act as an educational tool for the younger Barapa people, some of whom have not grown up in the area.

2. The Barapa people and country

Barapa Country straddles the Victorian-New South Wales border in Australia (). In the context of this paper when discussing the landscape, the use of ‘Country’ has a specific meaning for Indigenous people. It denotes their land and is framed in terms of place, and identity. The Barapa people traditionally used the rich, complex and seasonally changing environment of Barapa Country to their favour. The Mile or Mirri (Murray River) was the key focus within the landscape as the flood and dry seasons governed activities and movement through Barapa Country (CitationRhodes, 1996).

There is substantial evidence of on-going Barapa occupation and resource use in the landscape to this day. They built fish traps and larders at the edges of the lagoons and waterways to make the most of the abundant fish stocks (CitationPardoe, 2014; CitationVenn & Quiggin, 2007). Their living areas, like the other river people, were earth mounds situated in the landscape above the normal flood height (CitationRhodes, 1996). Nearby local stone outcrops have been mined for personal tools and the local trade network brought in resources from other communities (CitationRhodes, 1996).

The arrival of Europeans to Barapa Country begun in the 1830's with expeditions from Major Thomas Mitchell, Edward Eyre and Captain Charles Sturt (CitationKenyon, 2015; CitationRhodes, 1996). Others, eager for land followed soon after, and Barapa land was divided up into parcels and sold at minimal rates to the newcomers. Barapa people, like many Indigenous peoples, refused to submit to the settlement, resulting in conflict (CitationWeir, 2007). Partly in response to this conflict large communal properties, known as mission stations, were allocated by various state governments to ‘protect’ and ‘civilise’ Indigenous people (CitationWeir, Ross, Crew, & Crew, 2013).

The rapid European colonisation of the area led to substantial changes in the local environment (CitationRhodes, 1996). Intense extractive forestry focused on the River Red Gum (Eucalyptus cameldulensis) along the Mirri to supply the railways in South Australia with sleepers (CitationMarsden, 1990). The alteration of the river flow via dams and irrigation diversion changed the local hydrology and clearing for farming (both grazing and cropping) and occurred not long after the first European arrivals. Ploughing, logging, and the resulting erosion led to the destruction of physical evidence of Barapa occupation, the exact amount of which is unknown (CitationHumphries, 2007; CitationRhodes, 1996).

Along with the environmental change, there was also forced removal. Many Barapa people were moved to places like Moonacullah Mission, (approximately 100 km to the east) and with the death of Charlie Bradshaw in 1897, incorrectly identified as the ‘last Aborigine of the district’, the local narrative of the Barapa was limited for many years to an academic and archaeological interest (CitationRhodes, 1996). The excavation of burials at Kow Swamp, an ancient low-lying swamp, and the discovery of over 300 stone artefacts across the local farms being examples (CitationMulvaney, 1991; CitationRhodes, 1996; CitationThorne & Macumber, 1972; CitationWhyte, 2016). The reports of early European settlers writing about Barapa ‘villages’ of earth mounds by the waterways were forgotten, as the ‘Primitive Native’ discourse fostered by a colonial agenda took over (CitationBerryman & Frankel, 1984).

Today, Barapa people remain involved with their Country, but they continue to face substantial challenges. Currently, they do not have a unified representational organisation, especially after the Barapa Barapa Nation Aboriginal Corporation (BBNAC) had an application for registration under the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Act turned down in 2011 (CitationDepartment of Premier and Cabinet, 2015). A second application is currently under consideration with three other groups. New South Wales has a different recognition process for Traditional Owners.

The map described in this paper presents the Barapa traditional knowledge for a small section of Country. It also aims at making a contribution to the broader representation and decolonisation agenda of Barapa people through the use of Barapa language.

3. Northern Gunbower Island and environment

North Gunbower Island was chosen as the main focus of the map area for three reasons. The first reason is due to the existing cultural mapping activity by the Barapa in partnership with the North Central Catchment Management Authority (NCCMA) and Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) through the Water for Country and Living Murray programmes. These programmes are providing funds and technical support to engage and employ Barapa people with the purpose of developing a cultural watering plan for Gunbower Island. The projects have provided the participatory spatial data used in the map.

The second reason is due to its importance as ascribed both from an archaeological and ecological perspective (CitationHale & Butcher, 2011; CitationNCCMA, 2015; CitationRhodes, 1996; CitationWeir, 2009). Gunbower is recognised internationally in the Ramsar treaty for migratory bird species (CitationHale & Butcher, 2011). Previous archaeological surveys identified sites such as earth mounds, shell middens, and scar trees across the local landscape, the known extent of which is expanding with the current work (CitationRhodes, 1996). An on-going programme is also targeting pest species such as European Carp (Cyprinus carpio) as part of improving local waterway health (CitationDepartment of Environment and Primary Industries, 2013).

The third reason is that Gunbower Island is a self-contained geographic area with minimal disturbance. The island lies within the bounds of the Murray River and an anabranch of the river, Gunbower Creek. The Yemurikki map is focused on the northern section of the Gunbower Island due to the land claim from the neighbouring Yorta Yorta people in the southern section (CitationDepartment of Premier and Cabinet, 2015). Even with the locational focus, an important element of the map has been to highlight other places within Barapa Country of cultural importance. The map shows some of the important locations Barapa people travelled to for resources, spiritual links and meetings. Mt Hope and Pyramid Hill, Kow Swamp and Edwards and Koltey Rivers are examples (CitationLayton, 1997; CitationMulvaney, 1991). Important places from the post-European settlement such as Moonacullah and Deniliquin are also represented in images (CitationWeir et al., 2013).

The land tenure of Gunbower Island is a mix of private, public and government land. It has highly modified eucalypt woodland dominated by River Red Gum (Eucalyptus cameldulensis), Grey Box (E. microcarpa) or Black Box (E. largiflorens). The species distribution is dependent upon the local soil, flooding regime and logging history. Close to the river the landscape once underwent regular seasonal flooding resulting in the formation of levy deposits, seasonal swamps and wetlands as well as occasional course realignment (CitationCooling, Lloyd, Rudd, & Hogan, 2002; CitationRhodes, 1996).

There is a complex network of seasonal wetlands, depressions and floodways which channel water across the island landscape (CitationCooling et al., 2002). Prior to controlled flows of environmental water now allocated, Gunbower had been dry for many years, threatening the migratory birds and decreasing the local biodiversity (CitationCooling et al., 2002; CitationMurray–Darling Basin Authority, 2011). The other remnant forests along the river, such as Guttram Swamp, Barmah, and Nyah, face many of the same challenges as Gunbower with ecological health and cultural protection (CitationFinn & Jackson, 2011; CitationPorter, 2006).

4. Cultural mapping method

The Cultural mapping consists of the collection and representation of a variety of elements which are important to a culture (CitationBrennan-Horley et al., 2010). In practice, cultural mapping utilises a wide range of tools and techniques. It can be a highly technical pursuit utilising remote sensing or done with a simple sketch map. There is variation in the level of community input, though the most effective outcomes have high levels of community direction and participation (CitationLeeuw, Cameron, & Greenwood, 2012; CitationPánek, 2015; CitationPoole, 2003; CitationUNESCO, 2009). The Barapa community participated throughout the creation of this map, collecting GPS data, recommending elements of the map representation and developing the groups for the cultural asset types.

4.1. Community collected GPS data

The data from the community is part of an on-going Barapa cultural mapping project entitled Water For Country ( CitationNCCMA, 2015). Since 2013 the Barapa community, with the assistance of North Central Catchment Management Authority (NCCMA) has been mapping the cultural assets in the northern section of Gunbower Forest. The NCCMA is a statutory natural resource body which operates through an Australian federal government framework supporting landowners and other parties in sustainable land management programmes. The Water For Country project has the goal of reducing the decline in health and integrity of the constructed and environmental cultural assets.

Over the last three years, the data collection process has focussed on identifying and assessing the health of, and threats to, Barapa cultural assets. The identified assets include important places and physical evidence of ancestor's habitation, personal values, and connections with Gunbower as well as natural resources such as the plants and animals which inhabit the forest (CitationNCCMA, 2015). The majority of the cultural data is point-based information which has been collected and recorded in a participatory process using tablet-based GIS software.

The purpose of the data collection was to identify the state of cultural assets across Gunbower in an effort to inform future watering plans and to make a case for an allocation of cultural water (CitationNCCMA, 2015). Cultural water is the term used to describe Indigenous communities’ rights to water resources, much like farm and environmental rights (CitationBark et al., 2015). Cultural water is for the economic and environmental benefits of Indigenous communities and Country (CitationBark, Garrick, Robinson, & Jackson, 2012; CitationMooney, 2014). To date, the allocation of cultural water has not been widely implemented in Australia though there are changes to water policy underway.

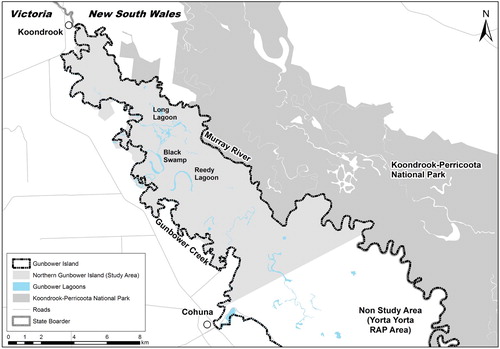

The three years of the project have involved over 30 Barapa people and collected 438 spatial features. Fieldwork usually occurs over a 2 week period in March and target locations are chosen based upon information from Barapa Elders, NCCMA staff, and previous cultural heritage assessments. The main areas of interest to date have been Reedy Lagoon, Long Lagoon and Black Swamp (). The data includes the location of culturally important plants, animal sightings, weed species and archaeological sites. The field data records information on the perceived health and requirements for water.

4.2. Participatory GIS and community defined assets

CitationVenn and Quiggin (2007) compiled a list of different types of cultural assets which occur within the Murray region, an area which includes Barapa Country. It is a reasonably comprehensive list focusing on the cultural heritage aspects of the landscape. For the Gunbower Yemurriki map project, however, the Barapa people built their own classification and list of assets (), identifying not only what is important to their community but also the assets they want to include on the map.

Table 1: List of Barapa asset groups, map colours used and examples

The asset list was developed over two community gatherings. The first gathering had 8 Barapa attendees, while the second had 15 Barapa attendees, with 4 Barapa people attending both events. The second event on Barapa Country was considered more productive by the attendees as it was held at Gunbower. The productivity difference is due in part to the cognitive benefits of being in the environment being discussed (CitationIsaac, Dawoe, & Sieciechowicz, 2009)

The asset group headings chosen by Barapa to map are People, Sites, Water, Fire, Plants, Animals and Threats (). These groups are represented on the map using different colours. The colour scheme was debated by Barapa participants and decided upon through consensus. The colour choices are reflective of standard perceptions of elements (water = blue, fire = red etc.) and an understanding that each asset type had to be distinguishable on the map. The community also decided that not every asset was appropriate to appear on the map. Due to concerns about the secret and sensitive nature of some assets the Barapa chose not to represent places such as burial sites. The potential for harm was seen to be too high.

In addition to the field data collection, the participatory mapping process included the opportunity for Barapa Elders and community to annotate an aerial photo of Gunbower Island and the local region at a series of community meetings. Over the course of this process, approximately 20 Barapa community members spoke, informing the list of important places, areas where they would like to do further investigation, personally important places, valued environmental information and to be able to relate their personal attachment to the broader Barapa Country.

4.3. Other information sources

The Yemurikki map also incorporates non-field sources such as information written by European explorers like CitationBlandowski (1858), environmental reports and flora and fauna assessments, e.g. CitationHale and Butcher (2011), CitationBennetts (2014), and CitationGott (1999). Cultural heritage information was obtained from reports such as the Gunbower Island Archaeological Survey (CitationRhodes, 1996), and the Dictionary of Aboriginal Placenames of Victoria (CitationClark & Heydon, 2002). Other language elements have been informed in part by the Wemba-Wemba dictionary developed by Victorian Council for Aboriginal Languages (VACL), as Wemba and Barapa are linguistically similar (CitationKenyon, 2015; CitationVACL, 2015).

The flow and flooding information of natural and regulated flows used in the map was obtained from a number of sources (CitationCooling et al., 2002; CitationHumphries, 2007; CitationMurray–Darling Basin Authority, 2011). The watercourse information used is an amalgamation of two state watercourse datasets. The main waterways and lagoons have been represented, while modern irrigation channels are not included. It is essential to note that the mapping of the seasonal flood runners is patchy and incomplete. A composite satellite image and LIDAR image have both been used as the base. The Lidar image has been manipulated to show an exaggerated hill shade in an attempt to clearly show changes in topography across the landscape.

5. Map design

In addition to traditional cartographic considerations, cultural maps often present design issues which are not usually faced with other maps. The issues identified with the Yemurriki map fit into three categories; the map purpose, the map content, and the cartographic design. We have sought to overcome the issues through a range of different techniques including a highly participatory process of map development.

5.1. Map purpose

The purpose of the cultural map had to be considered during development. What is it for? Who would use it and see it? As a cultural map, it should also provide benefit to the community (CitationChapin et al., 2005). The answer to these questions dictated the information included and how information is presented. First and foremost, this map has to be considered a public document, one designed for communicating outwardly Barapa presence and cultural information; rather than one intended for a private or exploratory use by Barapa (CitationMacEachren, 2004). The external focus has led to the Barapa Elders reviewing the sensitive cultural assets and deciding what was inappropriate public information. Gender and age-specific sites and locations at risk of destruction are two examples of non-public information. That guidance from Barapa Elders and community has been essential in the development process. Identifying what to show and what to remove is an essential part of cultural mapping and collaboration (CitationChapin et al., 2005; CitationGibson, Brennan-Horley, & Warren, 2010; CitationWatson et al., 2013).

5.2. Map content

The second consideration is the map content. The available environmental and cultural heritage data for Gunbower Island and surrounds is limited and both spatially and temporally patchy (CitationCooling et al., 2002; CitationRhodes, 1996). The Barapa field collection of data is focused on targeted areas within Gunbower such as around the larger lagoons and waterways. Therefore the collected data does not reflect the full distribution of the assets in the landscape. Important areas have been delineated by circular features and images of specific assets with informative text have been included.

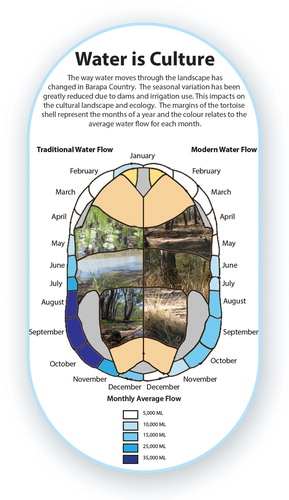

Representing the water is an important part of the map. Uncle Neville Whyman, Barapa Elder, states that for Barapa ‘water is culture’. Therefore showing the historical and the current seasonal flow regime is an important part of the Gunbower story. The water flow data displayed on the map was informed by the report ‘Environmental water requirements and management options in Gunbower Forest, Victoria’ by CitationCooling et al. (2002) and the CitationMurray Darling Basin Authority (2011). It shows the changes in flow rates prior to the commencement of the local environmental watering programme in 2013. Visualising the complex seasonal variability in water coverage in a map space proved to be difficult. Instead of a cartographic representation, the seasonal variation in the current, controlled water flow and the estimated pre-European volumes are shown in an information box (CitationCooling et al., 2002). The variation in water is shown using segments of a tortoise shell (). Each month is represented by one of the outer segments of the shell and the corresponding flow volumes are colour coded. The use of the tortoise was proposed at the Barapa community meeting. The three species of tortoise are important animals spiritually and as a traditional food resource.

The reinstatement of Indigenous languages is seen as an important element in the decolonisation process (CitationHarley, 2009). Where possible Barapa language is used on the map as this is important in both the educational and decolonisation perspectives (CitationHarley, 2009; CitationWeir et al., 2013). The names of many local townships, parishes and property places are Barapa in origin and have been included along with any known translations. The work by CitationClark and Heydon (2002) was the source for many of the toponyms used on the map. As an unwritten language, there has been confusion around the appropriate spelling of some words. The spelling by CitationClark and Heydon (2002) has been used.

The colonisation of Australia broke the landscape up into small land parcels. The Yemurikki map attempts to re-image a pre-colonial landscape as part of a visual decolonisation process. The map does not show tenure boundaries which are often included on conventional maps, such as property, state or council areas for that reason. These types of boundaries are, in terms of understanding Barapa values and cultural mapping, irrelevant and distracting content. The choice was made not to use them because freehold land is not void of cultural value for Barapa people, even if the physical assets have been removed or destroyed. Other Indigenous group boundaries have also been left off the map. Defining traditional boundaries can result in contentious decisions, some of which have legal and statutory implications (CitationCorbett & Rambaldi, 2009; CitationDepartment of Premier and Cabinet, 2015). Respecting the complicated and contentious nature is the reason for not including the modern defined boundaries of other traditional owner organisations on this map.

5.3. Cartographic design

Many of the design dilemmas identified are related to the complexity of information, such as the inclusion of intangible knowledge, temporal variations, and scale. The solutions used in the Gunbower Yemurriki map have been developed in partnership. The representation of the changes in water flow is one example of the collaborative process, developing a culturally relevant display that conveys complex information ().

As with any map, the colour and shape of symbols play an important role in information presentation (CitationMacEachren, 2004). When making choices about the map symbology it has been important to consider how to identify important areas without revealing exact on-ground locations of sites. The Barapa community discussed a range of alternative symbols during the initial map planning session. The visual representation of semi-transparent circular features covering important areas was favoured where there were multiple data points. The area symbols also reduce the impact of variable data quality for the individual points.

The use of images to show particular important assets was also suggested at the community meetings. The outline colour of each image acts as a key for the type of asset (). The associated explanatory text was developed as part of the consultation processes.

The choice made to show the remote locations was one of the initial guiding elements for this map. The limitation of scale has been addressed in the map by inserting images of the spatially distant locations in a direction similar to their cardinal direction from Gunbower, rather than fitting everything into a single small-scale map. The dilemma was that full extent of Barapa Country made Gunbower Island too small to be useful and there is on-going contention around cultural boundaries. Inserting the photos and aerial images of other places were identified by Barapa Elders as a useful and informative way to get around the scale dilemma. The purpose of the map is to identify specific places of cultural value where the direction is valuable but representing distance is not.

6. Conclusion

The Gunbower Yemurriki map discussed in this paper has been developed through a collaborative process with the Barapa people. The collaboration has influenced the design and types of assets which appear on the map. The result is a map that contains the locally important Barapa cultural assets, which include stories, animals and places.

The Barapa Community participated in the development of this map because they saw it as an important educational source for non-Barrapa people and also younger Barapa people about their Country. It shows to those people the important values of an area of Barapa Country. This map also gives the viewer an opportunity to see other important Barapa cultural locations and assets such as the plants and animals, important cultural locations. Not including property, local government or state boundaries highlights the pre-existing and continuous nature of Barapa Country. The map is centred on Gunbower Island and highlights the cultural values of water. It shows a range of cultural assets which are linked to the seasonably variable landscape in an effort to highlight the impact of changing water regimes in Barapa Country.

Without the collaboration, this map would not be as impactful to external groups or as valuable to the Barapa Community.

Software

Software used for compiling and designing this map includes Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustrator, and Esri ArcGIS v10.3.

CompressYemurriki2.pdf

Download PDF (107.3 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Barapa Barapa as co-copyright holders to this map and thank the Barapa Barapa Elders and Community for their input and feedback on this map which represents their cultural knowledge and heritage. It has been a privilege to work with the community and Barapa Water for Country Steering Committee. We also thank the North Central Catchment Management Authority, particularly Bambi Lees and Robyn McKay for their time and support in the development of this map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bark, R. H., Barber, M., Jackson, S., Maclean, K., Pollino, C., & Moggridge, B. (2015). Operationalising the ecosystem services approach in water planning: A case study of indigenous cultural values from the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 11(3), 239–249. doi: 10.1080/21513732.2014.983549

- Bark, R. H., Garrick, D. E., Robinson, C. J., & Jackson, S. (2012). Adaptive basin governance and the prospects for meeting Indigenous water claims. Environmental Science & Policy, 19-20, 169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.03.005

- Bennetts, K. (2014). Gunbower forest sentinel wetland and understorey survey autumn 2014. Woolamai: Fire, Flood and Flora.

- Berryman, A., & Frankel, D. (1984). Archaeological investigations of mounds on the Wakool River, near Barham, New South Wales: A preliminary account. Australian Archaeology, 19, 21–30. doi: 10.1080/03122417.1984.12092953

- Black, J. (2000). Maps and politics. Rathbone Place London: University of Chicago Press.

- Blandowski, W. (1858). Recent discoveries in natural history on the lower Murray. Melbourne.

- Brennan-Horley, C., Luckman, S., Gibson, C., & Willoughby-Smith, J. (2010). GIS, ethnography, and cultural research: Putting maps back into ethnographic mapping. The Information Society, 26(2), 92–103. doi: 10.1080/01972240903562712

- Brown, G., & Raymond, C. (2007). The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Applied Geography, 27, 89–111. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2006.11.002

- Bryan, J. (2009). Where would we be without them? Knowledge, space and power in indigenous politics. Futures, 41(1), 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.005 Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328708001110

- Chapin, M., Lamb, Z., & Threlkeld, B. (2005). Mapping indigenous lands. Annual Review of Anthropology, 34, 619–638. Retrieved from http://www.annualreviews.org.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120429

- Clark, I. D., & Heydon, T. (2002). Dictionary of Aboriginal place names of Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages.

- Cooling, M. P., Lloyd, L. N., Rudd, D. J., & Hogan, R. P. (2002). Environmental water requirements and management options in Gunbower Forest, Victoria. Australasian Journal of Water Resources, 5(1), 75–88. doi: 10.1080/13241583.2002.11465194

- Corbett, J., & Rambaldi, G. (2009). Geographic information technologies, local knowledge, and change. In M. Cope & S. Elwood (Eds.), Qualitative GIS: A mixed methods approach (pp. 75–92). London: Sage Publications.

- Department of Environment and Primary Industries. (2013). Gunbower Forest. Retrieved from http://www.depi.vic.gov.au/water/rivers-estuaries-and-wetlands/wetlands/significant-wetlands/gunbower-forest

- Department of Premier and Cabinet. (2015). Registered Aboriginal Parties. Retrieved from http://www.dpc.vic.gov.au/index.php/aboriginal-affairs/registered-aboriginal-parties

- Dudgeon, P., & Walker, R. (2015). Decolonising Australian psychology: Discourses, strategies, and practice. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 276–297. doi: 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.126

- Finn, M., & Jackson, S. (2011). Protecting Indigenous values in water management: A challenge to conventional environmental flow assessments. Ecosystems, 14(8), 1232–1248. doi: 10.1007/s10021-011-9476-0

- Gibson, C., Brennan-Horley, C., & Warren, A. (2010). Geographic information technologies for cultural research: Cultural mapping and the prospects of colliding epistemologies. Cultural Trends, 19(4), 325–348. doi:10.1080/09548963.2010.515006 Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=82846242&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Gott, B. (1999). Cumbungi, Typha species: A staple Aboriginal food in southern Australia. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 1, 33.

- Hale, J., & Butcher, R. (2011). Ecological character description for the Gunbower Forest Ramsar site. Report to the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water. Population and Communities (DSEWPaC), Canberra.

- Harley, J. B. (2009). Maps, knowledge, and power. In G. Henderson & M. Waterstone (Eds.), Geographic thought-A praxis perspective (p. 20). New York: Routledge.

- Herlihy, P. H., & Knapp, G. (2003). Maps of, by, and for the peoples of Latin America. Human Organization, 62(4), 303–314. doi: 10.17730/humo.62.4.8763apjq8u053p03

- Humphries, P. (2007). Historical Indigenous use of aquatic resources in Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin, and its implications for river management. Ecological Management & Restoration, 8(2), 106–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-8903.2007.00347.x

- Isaac, M. E., Dawoe, E., & Sieciechowicz, K. (2009). Assessing local knowledge use in agroforestry management with cognitive maps. Environmental Management, 43(6), 1321–1329. doi:10.1007/s00267-008-9201-8 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18820966

- Kenyon, C. (2015). An 1830s map: Whose map of the Mid-Murray River is it? Globe, The, 76, 1.

- Layton, R. (1997). Representing and translating people’s place in the landscape of northern Australia. In A. James, J. L. Hockey, A. H. Dawson (Eds.), After writing culture: Epistemology and praxis in contemporary anthropology (Vol. 122, p. 143). London: Routledge.

- Leeuw, S. D., Cameron, E. S., & Greenwood, M. L. (2012). Participatory and community-based research, indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: A critical engagement. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 56(2), 180–194. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/doi/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00434.x/pdf doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00434.x

- MacEachren, A. M. (2004). How maps work: Representation, visualization, and design. New York: Guilford Press.

- Marsden, S. (1990). History through the remains of the past: Discovering South Australia. Historic Environment, 7(3/4), 10.

- Mooney, W. (2014). Working for water justice in the Murray-Darling basin. Chain Reaction, 122, 20.

- Mulvaney, D. J. (1991). Past regained, future lost: The Kow Swamp Pleistocene burials. Antiquity, 65(246), 12–21. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X00079266

- Murray–Darling Basin Authority. (2011). Gunbower forest: Environmental water management plan. Canberra: Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) on behalf of the Commonwealth of Australia 2012.

- NCCMA. (2015). Indigneous partnerships. Retrieved from http://www.nccma.vic.gov.au/Water/Environmental_Water/Gunbower_Forest_and_Gunbower_Creek/Indigenous_Partnerships/index.aspx

- Pánek, J. (2015). ARAMANI–Decision-support tool for selecting optimal participatory mapping method. The Cartographic Journal, 52(2), 107–113. doi: 10.1080/00087041.2015.1119473

- Pardoe, C. (2014). Conflict and territoriality in Aboriginal Australia: Evidence from biology and ethnography. In M. Allan & T. Jones (Eds.), Violence and warfare among hunter gatherers (1st ed., pp. 112–132). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Poole, P. (2003). Indigenous peoples; A report for UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.landcoalition.org/sites/default/files/documents/resources/03_UNESCO_cultural_mapping.pdf

- Porter, L. (2006). Rights or containment? The politics of Aboriginal cultural heritage in Victoria. Australian Geographer, 37(3), 355–374. doi: 10.1080/00049180600954781

- Rhodes, D. (1996). Gunbower island archaeological survey. Melbourne: V. D. o. H. a. C. S. A. A. Division.

- Thorne, A., & Macumber, P. G. (1972). Discoveries of late pleistocene man at Kow Swamp, Australia. Nature, 238, 316–319. doi: 10.1038/238316a0

- UNESCO. (2009). Building critical awareness of cultural mapping: A workshop facilitation guide.

- VACL. (2015). Wemba Wemba [Information about Wemba Wemba]. Retrieved from http://www.vaclang.org.au/languages/wembawemba.html

- Venn, T. J., & Quiggin, J. (2007). Accommodating indigenous cultural heritage values in resource assessment: Cape York Peninsula and the Murray–Darling Basin, Australia. Ecological Economics, 61(2), 334–344. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/John_Quiggin/publication/4842104_Accommodating_indigenous_cultural_heritage_values_in_resource_assessment_Cape_York_Peninsula_and_the_Murray-Darling_Basin_Australia/links/0fcfd5123d7fa682c1000000.pdf doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.03.003

- Watson, A., Carver, S., Matt, R., Waters, T., Gunderson, K., & Davis, B. (2013). Place mapping to protect cultural landscapes on tribal lands. In W. P. Stewart, D. R. Williams, & L. E. Kruger (Eds.), Place-based conservation (pp. 211–222). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Weir, J. (2007). The traditional owner experience along the Murray River. In E. Potter, A. Mackinnon, S. McKenzie, & J. McKay (Eds.), Fresh water: New perspectives on water in Australia (pp. 44–58). Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Press.

- Weir, J. (2009). Murray lower darling rivers indigenous nations. In: J. Weir (Ed.), Murray river country: An ecological dialogue with traditional owners (pp. 91–117). Caulfield, VIC: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Weir, J., Ross, S. L., Crew, D. R., & Crew, J. L. (2013). Cultural water and the Edward/Kolety and Wakool river system. Canberra: AIATSIS.

- Whyte, M. (2016). Barapa Barapa Keeping Place documenting Aboriginal history. ABC Online. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-03-04/barapa-barapa-keeping-place-documenting-aboriginal-history/7220892