ABSTRACT

The article presents changes in the topography of the Toruń area due to the degradation of dunes by human activity, and a reconstruction of their earlier location and morphology. The reconstruction was made on the basis of historical maps and plans from the end of the eighteenth century, as well as contemporary cartographic materials and digital terrain models (DTM). Analysis of the sources showed that the main period of anthropogenic degradation of dunes in the city was the second half of the twentieth century. The balance of changes in the share of dunes within city limits is estimated to be a decrease of about 26.5% over the study period, and by around 60.2% in the part that is presently urbanised.

1. Introduction

The literature considers the issue of dune degradation by human activity (mainly by urbanisation and tourism) primarily in relation to forms on marine coasts (e.g. CitationCatto, 2002; CitationStancheva et al., 2011; CitationCabrera-Vega et al., 2013; CitationSantana-Corderoa et al., 2016; CitationGarcia-Lozanoa et al., 2018). Dunes in coastal areas occupied by a large part of the world’s population are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic transformations and destruction. These changes also apply – to a lesser extent – to inland dunes mainly located in urban areas (CitationMolewski, 2011).

One example of changes in city topography due to dune degradation caused by human activity is Toruń (Poland). Until almost the middle of the twentieth century, dunes were one of the characteristic features of the city’s cultural landscape. Since then, they have been largely destroyed (levelled) or transformed, mainly as a result of various types of construction works or the exploitation of sands as aggregates (Main Map). The original image of these now-disappeared or transformed dunes is presented by various methods in views, plans and maps of Toruń from the seventeenth century. Most of the dunes preserved until the mid-twentieth century, because in the fortress Toruń in the Prussian partition until the beginning of the last century investments in the suburbs were limited (CitationKwiatkowska, 1969; CitationGiętkowski et al., 2010). As a result, a large part of the area surrounding the medieval city partially retained its natural character until the 1950s.

The research aimed to: reconstruct the location and morphology of the dunes (within the limits of the modern city as designated in 1976) that have been destroyed (levelled) or transformed by human activity; analyse of the historical changes in the share of dunes in the city’s topography; estimate the balance of these changes in relation to the contemporary state; and determine the share of destroyed or transformed sand dunes in areas of various land-use types.

2. Study area

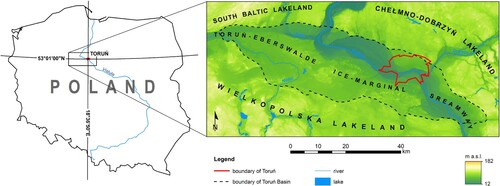

Toruń is located in north-central Poland, in the east of the Toruń Basin (), which is part of the Toruń-Eberswalde Ice-marginal Streamway (CitationKondracki, 1989) formed during the Weichselian glaciation (Main Map). The basin, with an area of approximately 1,750 km2, is occupied by a system of ice-marginal valley and river terraces created at the end of the Pleistocene. The Vistula flood plain is diversified by numerous oxbow lakes, and was shaped in the Holocene, beginning about 11,500 years ago (e.g. CitationMolewski & Weckwerth, 2017). The terrace surfaces are made of loose sand deposits, a lack of compact plant cover and dry climatic conditions prevailed in the ice sheet forefield (a periglacial climate), which favoured the formation of dunes. As a result, the Toruń Basin contains one of Poland’s largest fields of inland dunes (CitationMrózek, 1958). They occupy about 25% of its surface, and locally also occur in the edge of the morainic plateau surrounding the basin. Relict dunes (CitationLancaster, 2009) of the Toruń Basin were formed in several dune-forming phases at the end of the Pleistocene, beginning approximately 13,900 years ago (e.g. CitationNowaczyk, 1986; CitationJankowski, 2007). They stabilised about 10,200 years ago in the Holocene, with climate warming and humidification, as well as with the development of dense forests. Dune processes were re-initiated locally in this area from approximately 5,800 years ago (the Neolithic) due to agricultural development and deforestation. As a result, up until modern times, many aeolian forms have survived in the Toruń Basin, dominated by linear dunes (longitudinal and transverse), irregular shaped dunes and parabolic dunes with a maximum height of about 45 m.

The area of modern Toruń is 115.72 km2, and its surface is at a height of 34–95 m a.s.l. About 34% of that area is occupied by forests (about 40 km2). The original relief of the urbanised part of the city was significantly transformed by anthropogenic processes, which began with its founding in the thirteenth century (e.g. CitationMolewski & Juśkiewicz, 2018). Anthropogenic processes have obliterated or smoothed the terrace edges, and small valleys cutting into their slopes have disappeared. A significant number of dunes have been destroyed or transformed. Nowadays, longitudinal, parabolic and irregular dunes of up to 12 m high predominate. In terms of surface, the predominant anthropogenic relief features were created as settlement-related levelling planes and embankments in built-up areas. Remains of fortifications are characteristic features of Toruń’s anthropogenic landforms.

3. Materials and methods

Reconstruction of degraded dunes, analysis of the historical changes in the share of dunes in the city area and estimation of the balance of these changes in relation to the contemporary state were all done mainly based on: historical plans, maps and views (), contemporary analogue and digital cartographic materials and digital terrain models (DTM). The historical changes in the share of dunes within the city area was also analysed based on information on Toruń’s spatial development contained in the literature.

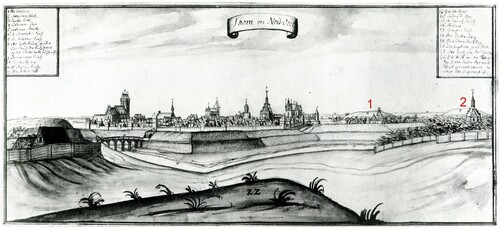

Figure 2. Toruń Panorama from the NE, from Georg Friedrich Steiner’s drawing from the first half of the eighteenth century (CitationBiskup, 1998), showing the non-existent today Baker’s Hill (No. 1) and preserved to this day, partly transformed Front Hare Hill (No. 2).

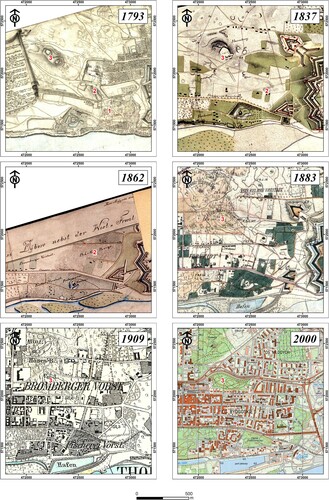

Queries of existing historical cartographic sources revealed the usefulness of plans and maps of Toruń from the end of the eighteenth century, despite the fact that until the second half of the nineteenth century, the relief was only depicted with the imprecise hachure technique (). They allowed the range of the earliest degraded dunes to be determined. The most useful were historical plans and maps from the end of the nineteenth century, where the topography was represented by the contour-line method that, until the beginning of the twentieth century, was sometimes combined with the hachure method. The most accurate and detailed of them is the German 1:25,000 topographic map issued from the late nineteenth century to the 1940s, and known as the Messtischblatt. The spatial analysis also used the oldest available satellite image of the city area from 1965, in digital version, with a resolution of 6×6 m, a modern digital orthophotomap from Toruń from 2016 (resolution 1×1 m) and a digital terrain model of the city landscape (DTM) from 2010 with resolution 5×5 m.

Figure 3. Examples of analysed historical and contemporary plans and maps from 1793–2000 covering part of the western suburbs of the city, showing the destroyed Gold Hill (No. 1) and Baker’s Hill (No. 2) and the partly transformed Front Hare Hill (No. 3) (source: State Archives in Toruń; Faculty of Earth Sciences, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń).

All the historical plans, maps and contemporary analogue topographical maps used were calibrated based on a digital topographic map in the Poland CS92 coordinate system (EPSG: 2180) generated from the Topographic Object Database (BDOT10k) with a level of detail corresponding to a 1:10,000 topographic map.

4. Results

Probably the earliest transformations of dunes outside the walls of the Old Town were associated with the construction of bastion fortifications in the seventeenth century and their subsequent repeated modification. In the eighteenth century, the suburbs of the city were significantly developed (CitationGregorkiewicz, 1983), mainly westwards and northwards, which transformed dunes, displacing them with construction. At the end of the eighteenth century, Toruń was occupied by the Prussian army and turned into a fortress, as a result of which all activities related to the development and building up of the city were subordinated to military functions. The city’s development was artificially stopped by the Prussian authorities’ ban on building residential and industrial facilities outside the outer line of fortifications (CitationGiętkowski et al., 2010). The suburbs developed only along the roads leading out of the city, creating spaces between them (CitationKwiatkowska, 1969). They remained partially undeveloped until the second half of the twentieth century (). From the beginning of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, the construction of a ring-type fortress continued (with varying intensity) (CitationGiętkowski et al., 2010). This transformed the city’s topography, mainly to the east and north-east of the Old Town and on the left bank of the Vistula. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, a ring of outer forts was built, approximately 3.5 km from the fortified old part of the city. Its construction involved the transformation and levelling of some dunes. In addition, in the second half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, the city expanded, with new buildings emerging. At this time, the dunes close to the suburbs immediately to the west of the Old Town were levelled or transformed. In the first half of the twentieth century, some of the dunes in the west of the modern city area were levelled during the construction of a military airport (currently a sports airport), which is an important feature of the Toruń fortress and other military facilities. Moreover, after the First World War and the return of Toruń to Poland, dunes were levelled as industrial facilities were built in the west of the city. The greatest destruction and transformation of dunes occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. This was mainly associated with the construction of many industrial and warehousing facilities starting in the late 1950s, mainly in the north and north-east of the city, and of residential and service buildings, as well as sports and recreation facilities, starting in the late 1960s. The development of the city resulted in the space between the city’s main roads being built up.

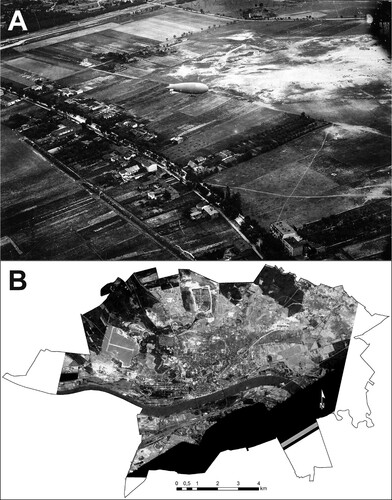

Figure 4. Historical photographs of Toruń: A – part of the Chełmińskie suburb of Toruń of the 1920s, taken from a military observation balloon (source: Regional Museum in Toruń), the picture shows loose eolian sands not covered with vegetation; B – Toruń and surroundings seen through the American reconnaissance satellite Corona 98 (KH-4A 1023) on the 23rd of August 1965 (source: US Geological Survey via Wikigrant number WG 2014-52); the picture shows dunes and eolian sands not covered with vegetation as irregular patches of bright phototones outside the built-up area.

As already mentioned, Toruń’s contemporary borders cover nearly 116 km2. At present, 37% of this area is urbanised (about 43 km2). Sand dunes within the city’s contemporary boundaries originally occupied about 4 km2, i.e. 3.5% of its area. Their original area decreased by about 26.5%, and about 6.1% of their area was transformed anthropogenically. In the modern urbanised part of the city, dunes originally covered about 1.4 km2 (35.3% of the total area of all dunes within the city limits), which constitutes 3.4% of its area. In the modern urbanised part of the city, the area of original dunes has decreased by about 60.2%, and 11.4% has been transformed anthropogenically to varying degrees.

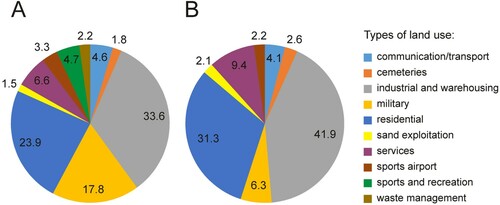

Within the boundaries of Toruń, there are dunes that were destroyed or transformed and that have been reconstructed in areas of various types of land use (). The largest percentage of their total area consist of dunes in industrial and warehousing areas, at approximately 33.6% (41.9% in the urbanised part of the city), in residential areas, at approximately 23.9%, and in service areas, at approximately 6.6% (respectively 31.3% and 9.4% in the urbanised part of the city). In addition, a significant percentage of the area of dunes that have been destroyed or transformed is associated with military areas, at about 17.8% (6.3% in the urbanised part of the city). The remaining reconstructed dunes are located in areas of other land-use types, and their share in the total area of destroyed and transformed dunes is less than 5%, both within the city limits and in its urbanised part.

5. Conclusion

Until almost the mid-twentieth century, dunes were a characteristic features of Toruń’s cultural landscape. In the suburbs directly adjacent to the Old Town – whose development was limited from the end of the eighteenth century by its military character (Torun fortress) – there were numerous dunes that diversified the flat terrace surface. The expansion of the fortress, which lasted until the early twentieth century and was especially intense in the nineteenth century, levelled or transformed some of the dunes. The late-eighteenth-century to mid-twentieth-century development, with varying intensity, of non-military build-up of the city suburbs did not significantly transform the dune relief, except in the west of the city. The largest anthropogenic degradation of dunes began in the late 1950s. It was associated with the spatial and socio-economic development of Toruń, mainly with the creation of new industrial, warehousing and residential areas. The balance of changes in the proportion of dune relief within the modern city’s limits is estimated to have decreased by about 26.5% in the last 200 years, and by about 60.2% in the currently urbanised part.

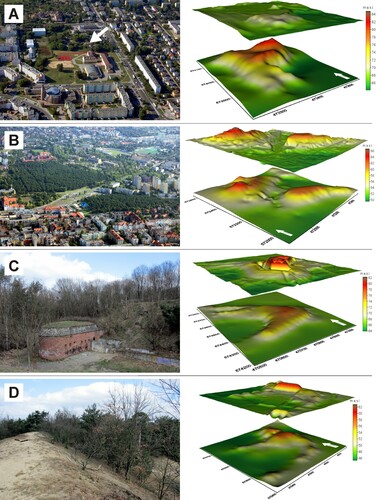

In the contemporary cultural landscape of the urbanised part of Toruń, dunes and remains of dunes are covered with forest that ‘preserves’ them, or they are almost invisible in the surface topography (). The significance of dunes in the topography of Toruń, including those that no longer exist (CitationPraetorius, 1832), is shown in the preservation of their names in the minds of the city’s inhabitants.

Figure 6. Examples of destroyed and transformed dunes and 3D models of the surface shape (lower model – morphology of primary dune; upper model – modern topography): A – the almost completely levelled Cossack Hill (an irregular dune), currently the area is occupied by a school, a gymnasium and a sports field, arrow indicates a preserved, built-on fragment of a dune; B – the afforested Hare Hills (irregular dunes), partly transformed by the construction of streets, a toboggan run and a petrol station; C – nose of parabolic dune destroyed by fort construction; D – the summit of a back-stop (part of the military shooting range) created by transforming a parabolic dune.

Software

ESRI ArcGIS 10.4.1 (with Spatial Analyst and Geostatistical Analyst extensions) and Global Mapper 17 were used for the manipulation and mapping of all spatial data sets. Voxler 3 was used to make 3D models of selected dunes. The Poland CS92 (EPSG:2180) coordinate system was used.

Main_Map.pdf

Download PDF (5.5 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Biskup, M. (1998). Toruń i miasta ziemi chełmińskiej na rysunkach Jerzego Fryderyka Steinera z pierwszej połowy XVIII wieku (tzw. Album Steinera). Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu.

- Cabrera-Vega, L. L., Cruz-Avero, N., Hernández-Calvento, L., Hernández-Cordero, A. I., & Fernández-Cabrera, E. (2013). Morphological changes in dunes as an indicator of anthropogenic interferences in arid dune fields [Special Issue 65]. In: D.C. Conley, G. Masselink, P.E. Russell, & T.J. O’Hare (Eds.), [Proceedings 12th International Coastal Symposium (Plymouth, England)]. Journal of Coastal Research, 165, 1271–1276. https://doi.org/10.2112/SI65-215.1

- Catto, N. (2002). Anthropogenic pressures on coastal dunes, southwestern Newfoundland. The Canadian Geographer / Le Geographe canadien, 46, 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2002.tb00728.x

- Garcia-Lozanoa, C., Pintóa, J., & Daunis-i-Estadellab, P. (2018). Changes in coastal dune systems on the Catalan shoreline (Spain, NW Mediterranean Sea). Comparing dune landscapes between 1890 and 1960 with their current status. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 208, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2018.05.004

- Giętkowski, M., Karpus, Z., & Rezmer, W. (2010). Twierdza Toruń. Dom Wydawniczy Duet.

- Gregorkiewicz, K. (1983). Toruń. Przestrzenny rozwój miasta. Biblioteczka Toruńska 8, Toruń.

- Jankowski, M. (2007). Chronologia procesów wydmotwórczych w Kotlinie Toruńskiej w świetle badań paleopedologicznych. Przegląd Geograficzny, 79(2), 251–269.

- Kondracki, J. (1989). Geografia regionalna Polski. Wydawnictwo Naukowe, PWN.

- Kwiatkowska, E. (1969). Rozwój przestrzenny Torunia. Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici, Geografia, 6, 187–206.

- Lancaster, N. (2009). Deserts. In O. Slaymaker, T. Spencer, & C. Embleton-Hamann (Eds.), Geomorphology and Global Environmental Change (pp. 276–296). Cambridge University Press.

- Molewski, P. (2011). Przeobrażenia rzeźby terenu i powierzchniowej budowy geologicznej dzielnicy Torunia-Mokre (Przedmieście Mokre) w czasach historycznych. Archaeologia Historica Polona, 19, 189–202.

- Molewski, P., & Juśkiewicz, W. (2018). Reconstruction of selected paleoenvironmental components of medieval Toruń, Poland, and its close suburbs. Journal of Maps, 14(2), 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2018.1486746

- Molewski, P., & Weckwerth, P. (2017). Ukształtowanie powierzchni terenu i geneza rzeźby. In A. Radzimiński (Ed.), Dzieje regionu kujawsko-pomorskiego (pp. 56–67). Województwo Kujawsko-Pomorskie i Towarzystwo Naukowe Organizacji i Kierownictwa.

- Mrózek, W. (1958). Wydmy Kotliny Toruńsko-Bydgoskiej. Wydmy śródlądowe Polski, 2, 7–59.

- Nowaczyk, B. (1986). Wiek wydm, ich cechy granulometryczne i strukturalne a schemat cyrkulacji atmosferycznej w Polsce w późnym vistulianie i holocenie. Seria Geografia, 28.

- Praetorius, K. G. (1832). Topographisch-historisch-statistische Beschreibung der Stadt Thorn und ihres Gebietes, Thorn.

- Santana-Corderoa, A. M., María, L., Monteiro-Quintanab, M. L., & Hernández-Calvento, L. (2016). Reconstruction of the land uses that led to the termination of an aridcoastal dune system: The case of the Guanarteme dune system (Canary Islands, Spain), 1834–2012. Land Use Policy, 55, 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.02.021

- Stancheva, M., Ratas, U., Orviku, K., Palazov, A., Rivis, R., Kont, A., Peychev, V., Tõnisson, H., & Stanchev, H. (2011). Sand dune destruction due to increased human impacts along the Bulgarian Black Sea and Estonian Baltic Sea coasts [ Special Issue]. Journal of Coastal Research, 64, 324–328 [Proceedings of the 11th International Coastal Symposium], Szczecin, Poland.