ABSTRACT

While it is widely known that socio-cultural transformations have a spatial impact on geographical areas, limited attention has been paid to mapping such transformations. This paper aims to explore how historical maps of land-use changes can be excellent tools for this purpose. The Lafkenmapu area in Chile, which has undergone critical socio-cultural transformations over the last five centuries, served as a case study. A total of five historical periods were described and translated into land-use change maps (pre-Hispanic; colonial; post-colonial; state consolidation; present). Non-cartographic (e.g. historical chronicles and publications) and cartographic sources (historical maps, aerial photography and satellite images) were integrated for each period to create a timeline map. Finally, some concluding remarks discuss the added value of the maps as a tool for a better understanding of the impact of socio-cultural transformations on land use and population distribution.

1. Introduction

The footprint of socio-cultural transformations can be seen in the spatial location of land use patterns, being particularly relevant when such transformations occur between human cultures with different worldviews. A good example is how occidental cultures displaced and substituted native populations, their social habits, and their land-use practices (CitationGuevara, 1902; CitationLatcham, 1924). Historical maps can be excellent tools to assist and complement historical studies of socio-cultural transformations, providing spatial representations of land use patterns and facilitating a better understanding of the past. The area known as Lafkenmapu, Chile, is a case in point (CitationEdney, 2019).

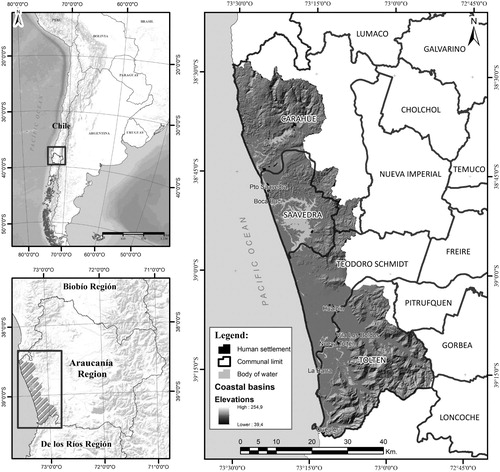

Lafkenmapu is the native name of a coastal area of south-central Chile (approx. 30,000 inhabitants), located between the Itata and Toltén Rivers, the Pacific Ocean, and the Coastal Mountain Range (). Before 1551, the region was occupied exclusively by the Mapuche population, which mainly used the area for agricultural purposes. Lafkenmapu was the last territory under Mapuche control, resisting invasion by the Spanish Empire for 300 years and the Chilean State after independence for a further 80 (CitationBengoa, 2000; CitationPinto, 2003). While previous research and chronicles have examined the history of intercultural changes in the area (CitationDe Ovalle, 1646; CitationDomeyko, 1846; CitationGay, 1854; CitationPhilippi, 1876; CitationPissis, 1875; CitationTreutler, 1866), no attention has been paid to exploring the effects of these cultural changes on land use. Bridging this gap can be valuable to facilitate a better integration of native and occidental views of land-use planning in the present. Moreover, it can provide a conceptual and geographical basis for policy-making processes that reinforce the social inclusiveness of native cultures.

This paper aims to construct a historical map (from the pre-Hispanic period to the present) that shows the effects of land-use changes in the Lafkenmapu zone, originated by intercultural transformations in areas originally occupied by native Mapuche populations. Five historical periods are covered: (i) pre-Hispanic (<1551); (ii) colonial (1551–1886); (iii) post-colonial (1886–1934); (iv) state consolidation (1934–1973); (v) present (>1973). A set of historical sources were combined and translated into the final map, including historical records (e.g. chroniclers and naturalists’ expeditions), academic publications, historical maps, population censuses about land ownership, and aerial photographs for recent periods.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a brief geographical description of the case study. Section 3 details the historical periods used for constructing land-use covers, while Section 4 presents the map design process. Section 5 highlights the results obtained, including the composition of the final map. Finally, Section 6 concludes with some remarks.

2. A geographical synthesis of Lafkenmapu

The Lafkenmapu extends over mountain ranges, marine erosion platforms, and extensive river-marine plains (CitationPeña-Cortés et al., 2014) (). Agricultural activities are mainly located in platforms and places closer to the plains. The platforms are characterised by agricultural and livestock use, while the fluvial-marine plain is mostly represented by wetlands of high ecological value (CitationPincheira-Ulbrich et al., 2016). There are also stabilized coastal dunes with exotic vegetation (Pinus radiata) (CitationPeña-Cortés et al., 2014).

3. Periods of socio-cultural transformation

Previous research has focused on the study of socio-cultural transformations in the context of the Araucanía (CitationCrow, 2013; CitationDe la Maza, 2014; CitationDi Giminiani, 2012, Citation2015; CitationMarimán et al., 2006; CitationNahuelpan et al., 2012). This body of literature has emphasised those political, symbolic, and technical aspects that contributed to the control of the territory, providing physical footprints in the landscape evolution (CitationEscalona Ulloa, 2019). A total of five historical periods of socio-cultural transformation have been identified for this research, which are detailed in the reminder of this section. The distinction of those historical periods is related to their singularity to originate relevant changes in land use patterns according to agricultural practices, new legislation, etc.

3.1. Pre-Hispanic period (<1551)

Native populations occupied the study area. Both the Pitrén and Vergel cultures dominated the Lafkenmapu. Then, the Mapuche culture became established. The interaction between the Mapuche population and land uses was mainly based on their understanding of nature and land use as sacred. Agricultural practices were focused mainly on subsistence (CitationDe Bybar, 1578; CitationDe Nájera, 1614; CitationDe Ovalle, 1646).

3.2. Colonial period (1551–1886)

Successive Spanish expeditions predominated. The aim was based on building forts and founding new towns (e.g. Angol, Nueva Imperial, and Villarrica). The Mapuche population frequently stopped those Spanish expeditions, and soldiers were mostly expelled around 1600. However, inter-cultural relationships took place between the Mapuche culture and Spanish populations (CitationGuevara, 1902; CitationSaavedra, 1870), originating the incorporation of occidental habits (e.g. agriculture) into the region (CitationManquilef, 1911).

3.3. Post-colonial period (1886–1934)

The formation of the Chilean nation-state introduced some administrative policies in the Lafkenmapu area, coincident with the establishment of the Malleco and Cautín provinces (CitationEspinoza, 1890). This originated substantial socio-cultural transformations, based on implementing extensive agricultural practices (e.g. wheat bowl), building of railway lines, using intensively of mobile sawmills called ‘Locomóviles’ (e.g. around Budi Lake), burning of forest to open up new areas of farmland (e.g. by the ‘El Budi’ colonial company), consolidating the urban system, and dividing administratively the region (CitationCensuses, 1865, Citation1875, Citation1895; CitationMenadier, 2012). Under this context, a severe fragmentation of places traditionally occupied by the Mapuche population took place (CitationComisión Parlamentaria de Colonización, 1912), and the native population was mostly re-located in the coastal strip of Lafkenmapu. The government created a legal land grant instrument -called ‘Merced de Tierras’- for allocating (new) lands to the Mapuche population. The first indigenous communities were then created by the law of ‘Foreign colonisation’ (1874–1896).

3.4. State consolidation period (1934–1973)

The Chilean state became a reality, and Lafkenmapu was incorporated into the administrative consolidation process. A succession of governments created various state agencies such as CORFO (Corporation for the Promotion of Production), CONAF (National Forest Corporation), and IREN (Natural Resources Research Institute) that fostered an extensive agricultural model in Lafkenmapu. The forestry industry emerged strongly in Chile during this period, particularly in the case study (CitationKlubock, 2014). An agrarian reform was also made to modernise agricultural practices (1960s), as well as to reinforce social rights through the expropriation of agricultural lands from landowners (CitationLey, 15020, 1967). Land use cover was also affected by the 1960 earthquake (9.5 Richter scale), which is the biggest earthquake ever known. Nevertheless, the Mapuche population continued mainly with their subsistence-based agricultural practices (CitationPeña-Cortés et al., 2014).

3.5. The present (1973–2020)

A neoliberal economic model was followed, resulting in: (i) derogation of the 1960s agrarian reform; (ii) land expropriations from the Mapuche population in favour of the private sector; (iii) the development of new human settlements (e.g. Comuna Teodoro Schmidt) (CitationBengoa, 2000; CitationCorrea et al., 2005). The forestry industry was also favoured (Law no. 701), being an intensive activity in the Lafkenmapu. Wetlands were also drained for conversion to agriculture. Other initiatives promoted more intense tourist activity in the region (e.g. tourist routes). In 1994, a national programme to regulate the use of the coast was approved, recognising the ancestral use of this area by the native population, and granting them access to the coast and water bodies.

4. Research design

4.1. Data sources

Two primary data sources were used (): Non-cartographic and cartographic. Non-cartographic sources included historical chronicles by travellers and naturalists, historical reports, and other publications mainly from the Chilean National Library (Santiago, Chile) and the Regional Museum (Araucanía, Chile). Cartographic sources covered historical maps, aerial photography, satellite images for the most recent periods (Landsat and Spot images, aerial photography by the Aerophotogrametric Service [SAF], and maps produced by the Military Geographical Institute). Historical maps were consulted in the Chilean National Library (Santiago, Chile), the Regional Museum (Araucanía, Chile), on-line resources, and other libraries from the local context (e.g. university libraries).

Table 1. Data sources.

4.2. Historical map design

The mapping process was based on integrating the described data sources for each period. Given the spatial detail of the historical information, it was used a scale of 1:50,000 for translating historical information into land-use maps. A similar land use legend was used for the five periods, according to the criteria developed by the National Forestry Corporation (CitationINFOR, 1964).

The specific process of translating historical sources into maps was based on the identification of existing landmarks in historical maps, using them as guides for georeferencing. The itineraries shown in chronicles were reconstructed and digitalised facilitating its spatial interpretation. Then, the land use data were digitalised. The names or toponyms of rivers, mountain ranges, and specific places along the Araucanía coast have been kept constant over the periods studied. For the more recent periods, aerial photography and satellite images were processed and combined with other sources (e.g. Native Vegetation Survey) to obtain land use covers. Others own land-use maps previously elaborated by the research team were also used.

Each historical source was critically reviewed according to three elements: criticism, triangulation, and hermeneutics. The criticism allowed the identification of those information sources that might be incomplete and biased, determining their degree of reliability. The triangulation sought to combine the perceptions of different sources before mapping a given element. That facilitated the identification of contradictions. Finally, hermeneutics aimed at defining the meaning of language and texts used through their relationships with the historical contexts in which they are interpreted (CitationDonnelly & Norton, 2011; CitationKipping et al., 2014).

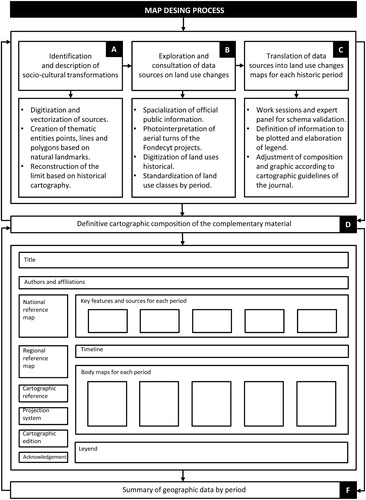

4.3. Final map structure

The map design process was based on a sequential scheme, based on the following phases (): (A) identification and description of socio-cultural transformations periods (Section 2); (B) consultation of data sources on land-use changes; (C) translation of data sources into land use change maps; (D) definitive cartographic composition; (F) layout including a summary of geographic data by period integrated. It is worth mentioning that a panel of three experts – history, heritage, and regional geography – was assembled to validate and refine the final cartographic composition.

5. The impact of socio-cultural transformation on land use changes

This section details the main changes of land use patterns, originated by socio-cultural transformations. summarises the extension of land use covers for each period.

Table 2. Main changes of land use patterns (ha).

5.1. Pre-hispanic – up to 1551

The Lafkenmapu is mainly covered by large expanses of native forest (157,670 ha), highlighting both wetlands (16,710 ha) and water bodies (57,730 ha) with abundant native vegetation and impenetrable forests. The inhabitants of the ‘seashore’ (CitationDe Ovalle, 1646) or ‘Lafkenmapu’ (CitationMolina, 1788) are also established in this place, being popularly known as ‘coastal Indians’ (CitationDe Nájera, 1614). Those native populations were settled mainly around the shores of Budi Lake, an area that covers approximately 58,400 ha. The settlements of the original Mapuche-Lafkenche populations close to the rivers and the lake have been marked with yellow hatching in the final map (Main Map). The large expanses covered with forest, described in contemporary chronicles, presented an abundance of native vegetation, impenetrable forests and the inhabitants of the ‘seashore’ (CitationDe Ovalle, 1646) or ‘Lafkenmapu’ (CitationMolina, 1788) who were known as ‘coastal Indians’ (CitationDe Nájera, 1614).

5.2. Colonial – 1551–1886

The Lafkenmapu is finally incorporated into the Chilean country after maintaining its independence for more than 300 years (Treaty of Quilín in 1641; CitationLeón, 1993; Treaty of Tapihue in 1774; CitationBengoa, 2007). The three shield-shaped symbols on the map highlight the separation of the Araucanía from Chile (Main Map), while the lines on the map represent the border of the ‘old Frontera’. During the nineteenth century, the State of Chile introduced a set of measures to seise Mapuche lands and occupy them with ‘civilised’ people. During this process, the case study was fragmented after the promulgation of the Settlement Law (CitationLey de Radicaciones, 1866) and the Foreign Colonisation Law (1874–1896). The first relevant changes in land use patterns took place during this period due to the need for productive agricultural lands for the immigrant population. That led to burn large areas of the Araucanía coast, generating new agricultural places (25,200 ha) (CitationErrázuriz, 1892). The red, purple, and blued dotted lines show the routes of the various expeditions carried out by naturalists, generally parallel to the coastline and water bodies (CitationDomeyko, 1846; CitationGay, 1854; CitationPhilippi, 1876; CitationTreutler, 1866).

5.3. Post-colonial 1886–1934

Land use patterns experienced severe transformations. This was originated by the installation of new production processes associated with farming and tourism, based on the natural resources of the region (CitationEl Campesino, 1874–1875; CitationMenadier, 2012). In particular, the new area covered by crops had an extension of 35,780 ha that originally was native forest (Main Map). This period saw the first political-administrative division of the case study with the definition of the provinces of Malleco and Cautín (CitationEspinoza, 1890). This was also a period of disputes between the external society (established in the region) and the Mapuche population, who appealed to various national authorities to complain about the constant losses of their land. Then, it was applied the concept of ‘Mercedes de Tierra’ to recognised land properties (1894–1910) for the Mapuche population (CitationPavez, 2008). There were only 6,310 hectares registered for use by the Mapuche population.

5.4. State consolidation 1934–1974

In this period can be seen a greater detail in land cover information (Main Map). That is due to the availability of aerial photography and locally produced cartography. The period is characterised by transformations in land use patterns (CitationIGM, 1944–1945), based on large expanses of land converted to farming (24,240 ha). It is also highlighted the presence of scrubland and wet meadows (70,430 ha) as well as the existence of forestry plantations of exotic species (61,820 ha), resulting from the encouragement of the forestry industry by CORFO and its action plans (CitationCORFO, 1939, Citation1939–1949). All these new land use patterns affect the native forest, which decreased to 50,690 ha in this period.

A necessary process taking place in this period was the implementation of the agrarian reform (CitationLey, 15020, 1962), aimed to change the relationship between landowner and tenant and balance the concentration of lands. The final objective of those changes was to alter the distribution of earnings in the countryside (CitationCorrea et al., 2005; CitationPinto, 2003).

The map also reveals the consolidation process of the State of Chile through regionalisation and the formation of political-administrative units (region, province and comuna). The red patches that indicated the appearance of incipient urban centres in the previous historic period grew and became consolidated (160 ha) (Main Map), connected by an extensive road network. All those urban areas were affected by the earthquake and tsunami on 1960 May 22nd, which led to subsidence of the coastline and an increase in the area of wetlands in what had previously been farmland (CitationPeña-Cortés et al., 2014).

5.5. Present 1974– 2020

A higher land use density is observed, recorded by geographical information systems that allow a more detailed analysis of the case study. This analysis shows strong growth of forestry plantations with exotic species, established inland on the Coastal Range. During this period, the forest plantation area grew from 1,820–46,640 ha (CitationCONAF, 2011), making the demand for wood and its products a critical element of change in the study area, as in the rest of the region (CitationKlubock, 2014). Unfortunately, this expansion process helped to reduce 7.9% of the native forest (12,520 ha).

Together with national policies, the described land-use transformations promoted an Area of Indigenous Development with the communities of the sector, covering an area of 38,700 ha (Decree-Law 2568, 1979) in limited spaces along the coastline. This increased the vulnerability of the Mapuche population due to the low agricultural value of the lands associated with the Area of Indigenous Development. Finally, the comunas of Carahue, Saavedra, Teodoro Schmidt and Toltén emerged along the coast of the Araucanía Region (470 ha).

6. Conclusions

The use and interpretation of historical maps enable us to recognise the succession of changes and transformations which have occurred in Lafkenmapu, both in terms of the physical geography and of the relation between society and nature, through the conjugation of documentary and cartographic historical sources.

Cartographic representation also allows us to express the construction of the landscape and its successive modifications in space and time, providing an explanation of current reality based on the historical processes in the territory. In this way, we can show changes in land use in the territory of the Mapuche people diagrammatically, and explain how occupation by colonists occurred. In particular, the historical analysis revealed that 92% of existing native forest in the pre-Hispanic period has been modified, while the agricultural lands have experienced an increase of 50% from the post-colonial period to the present. Finally, it is worth mentioning the relevance of the forest plantation in the present, but almost inexistent in the previous historical periods. Thus maps of this type are a useful instrument for policy-making in this case study, especially if we consider the claims raised by the Mapuche people for their original lands.

The methodology used recognises the complexity of integrating different types of source and scales of information. However, this was solved by an exhaustive documentary review, including chronicles, reports, gazettes, censuses, books and scientific articles, enabling us to draw up a detailed narrative of the historical processes in Lafkenmapu.

7. Software

For the generation of historical maps, the ArcGis 10.6 software has been used, generating georeferencing thematic covers (.shp). Such covers were exported in.png format at 300 dpi, being finally edited by the Adobe Photoshop CS5 software.

Main Map.pdf

Download PDF (75.9 MB)Disclosure statement

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albert, F. (1901). Los bosques en el país. Imprenta Moderna.

- Bengoa, J. (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche. Siglos XIX y XX. LOM.

- Bengoa, J. (2007). Documentos adicionales a la Historia de los Antiguos Mapuches del Sur. Catalonia.

- Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. (1869). Croquis de la línea del Malleco i nuevos fuertes de Cautín. Memoria Chilena. http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-86819.html. Accedido en 1/6/2020

- Bologna, N. (1910). Mapa de colonización de la provincia de Cautín, Inspección General de Tierras y Colonización. Archivo Regional de La Araucanía.

- CENSUS. (1865). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- CENSUS. (1875). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- CENSUS. (1895). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- CENSUS. (1907). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- CENSUS. (1920). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- CENSUS. (1930). Censo general de la república de Chile. Imprenta Nacional.

- Cisternas, M. (2002). Cambios de uso del suelo, actividades agropecuarias e intervención ambiental temprana en una localidad fronteriza de La Araucanía (S. XVI- XIX). Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 29, 83–94.

- Cisternas, M., Torres, L., Araneda, A., & Parra, O. (2000). Comparación ambiental mediante registros sedimentarios, entre las condiciones prehispánicas y actuales de un sistema lacustre. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 73(1), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-078X2000000100014

- Comisión Parlamentaria de Colonización. (1912). Informe, Proyectos de Ley, Actas de las Sesiones y Otros Antecedentes. Imprenta y Litografía Universo.

- Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF). (1999). Catastro y evaluación de recursos vegetacionales nativos de Chile.

- Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF). (2009). Catastro de uso del suelo y vegetación. Monitoreo y actualización región de La Araucanía. Periodo 1993–2007.

- Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF). (2011). Catastro de los recursos vegetacionales nativos de Chile: Monitoreo de cambios y actualizaciones período 1997 - 2011.

- Corporación de Fomento a la Producción (CORFO). (1939). Plan de fomento industrial. Imprenta universo.

- Corporación de Fomento a la Producción (CORFO). (1939–1949). Esquema de 10 años de labor. Chile. http://repositoriodigital.corfo.cl/handle/11373/1409

- Correa, M., Molina, R., & Yañez, N. (2005). La Reforma Agraria y las Tierras Mapuche. LOM Ediciones.

- Crow, J. (2013). The Mapuche in modern Chile: A cultural history. University Press of Florida.

- De Bybar, G. (1578). Crónica y relación copiosa y verdadera de los reinos de Chile. The newberry Library.

- De la Maza, F. (2014). Between conflict and recognition: The construction of Chilean indigenous policy in the Araucanía region. Critique of Anthropology, 34(3), 346–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X14531836

- De Nájera, G. (1614). Desengaño y reparo de la guerra del Reino de Chile. Imprenta Ercilla.

- De Ovalle, A. (1646). Histórica relación del Reyno de Chile y de las misiones y ministerios que exercita en la Compañía de Jesús. Impreso en Roma por Francisco Caballo.

- Di Giminiani, P. (2012). Tierras ancestrales, disputas contemporáneas: Pertenencia y demandas territoriales en la sociedad Mapuche rural. Ed. Universidad Católica de Chile.

- Di Giminiani, P. (2015). The becoming of ancestral land: Place and property in Mapuche land claims. American Ethnologist, 42(3), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12143

- Domeyko, I. (1846). Araucania y sus habitantes. Imprenta chilena.

- Donnelly, M., & Norton, C. (2011). Doing history. Routledge.

- Edney, M. (2019). Cartography. The ideal and its history. University of Chicago Press.

- El Campesino. (1874–1875). Boletín de la sociedad nacional de agricultura. VI(2), 1874–1875.

- Errázuriz, I. (1892). Tres Razas. Imprenta de la Patria.

- Escalona Ulloa, M. (2019). Paisaje, poder y transformaciones territoriales en La Araucanía, 1846–1992. Una ecología política histórica. Tesis Doctorado en Arquitectura y Estudios Urbanos. P. Universidad Católica de Chile, 277 pp.

- Espinoza, E. (1890). Geografía descriptiva de la República de Chile: Imprenta Gutenberg.

- Gay, C. (1854). Atlas de la historia física y política de Chile. Imprenta E Thunot.

- Guarda, G. (1968). La ciudad chilena del siglo XVIII. Centro Editor de América Latina.

- Guevara, T. (1902). Historia de la civilización de Araucanía. Tomo III, los araucanos y la república. Barcelona.

- Instituto Forestal (INFOR). (1964). Mapa preliminar de tipos forestales provincias de Bío-Bío, Malleco, Arauco, Cautín y Valdivia [material cartográfico], Chile, http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.gob.cl/bnd/631/w3-article-330859.html

- Instituto Geográfico Militar (IGM). (1944–1945). Fotografías del vuelo Trimetrogon. Chile.

- Instituto Geográfico Militar (IGM). (1986). Carta Temuco, escala 1:250,000. Chile.

- Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Naturales (IREN). (1970). Uso potencial de los recursos naturales, Provincia de Cautín, base cartográfica. Chile.

- Kipping, M., Wadhwani, D., & Bucheli, M. (2014). Analyzing and interpreting historical sources: A basic methodology. In M. Bucheli & D. Wadhwani (Eds.), Organizations in time: History, theory, methods (pp. 306–329). Oxford University Press.

- Klubock, T. (2014). La frontera. Forests and ecological conflict in Chile’s frontier territory. Duke University Press.

- Latcham, R. (1924). La organización social y las creencias religiosas de los antiguos araucanos. Imprenta Cervantes.

- León, L. (1993). El parlamento de Tapihue, 1774. Nütram, año IX, 32, 7–53. http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/archivos2/pdfs/MC0000975.pdf

- Ley 15020. (1960). Reforma agraria. 27 de noviembre de 1962. Chile.

- Ley de colonización extranjera. (1874). Sobre colonización extranjera por empresas particulares y prohibitiva de la adquisición de terrenos de indígenas, Santiago.

- Ley de Radicaciones. (1866). Sobre radicación y concesión de títulos de merced a los indígenas.

- Manquilef, M. (1911). Comentarios del pueblo araucano (la faz social). Anales de la Universidad de Chile. Tomo CXXVIII, pp. 1–60.

- Mansoulet, J. (1893). Guía-crónica de la frontera araucana de Chile: años 1892–1893: apuntes históricos, topográficos, geográficos, descriptivos y estadísticos de sus poblaciones, de su comercio, industrias y agricultura: primer año. Barcelona. http://www.libros.uchile.cl/439

- Manuel, J. (1870). Plano de Arauco y Valdivia con la designación de la Antigua i Nueva línea de Frontera contra los Indios. http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-99609.html

- Marimán, J., Canuiqueo, S., Millalén, J., & Levil, R. (2006). Escucha Winka! Cuatro ensayos de historia nacional Mapuche y un epílogo sobre el futuro. LOM Ediciones.

- Menadier, J. (2012). La agricultura y el progreso de Chile (1869–1886). CCHC-PUC-DIBAM.

- Molina, A. (1788). Compendio de la historia geográfica, natural y civil del Reyno de Chile. Impreso en Madrid.

- Nahuelpan, H., Marimán, P., Huinca, H., & Carcamo-Huechante, L. (2012). Ta iñ fijke xipa rakizuameluwün: Historia, colonialismo y resistencia desde el país Mapuche. Ediciones Comunidad de Historia Mapuche.

- Oficina de Planificación Nacional (ODEPLAN). (1973). Diagnóstico de desarrollo regional. Periodos 1970 y 1970–1973. Santiago.

- Pavez, J. (2008). Cartas Mapuches del siglo XIX. Ocho libros.

- Peña-Cortés, F., Limpert, C., Andrade, E., Hauenstein, E., Tapia, J., Bertrán, C., & Vargas-Chacof, L. (2014). Dinámica geomorfológica de la costa de La Araucanía, (Chile). Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 58(58), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022014000200013

- Peña-Cortés, F., Pincheira-Ulbrich, J., Bertrán, C., Tapia, J., Hauenstein, E., Fernández, E., & Rozas, D. (2011). A study of the geographic distribution of swamp forest in the coastal zone of the Araucanía region, Chile. (Chile). Applied Geography, 31(2), 545–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.11.008

- Philippi, F. (1876). Viaje a Toltén I a la laguna de Budi. Revista Chilena. Tomo, V, 161–172.

- Pincheira-Ulbrich, J., Hernández, C. E., Saldaña, A., Peña-Cortés, F., & Aguilera-Benavente, F. (2016). Assessing the completeness of inventories of vascular epiphytes and climbing plants in Chilean swamp forest remnants. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 54(4), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2016.1218899

- Pinto, J. (2003). La formación del Estado y la nación, y el pueblo mapuche. Chile. Dibam.

- Pissis, A. (1875). Geografía física de la República de Chile. Instituto Geográfico de Paris.

- Saavedra, C. (1870). Documentos relativos a la ocupación de Arauco que contienen los trabajos practicados desde 1861 hasta la fecha. Imprenta de la libertad.

- Servicio Aerofotogramétrico de Chile (SAF). (1960). Vuelos aerofogramétricos sector costa de La Araucanía.

- Servicio Aerofotogramétrico de Chile (SAF). (1978). Vuelos aerofogramétricos sector costa de La Araucanía.

- Servicio Aerofotogramétrico de Chile (SAF). (2008). Vuelos aerofogramétricos sector costa de La Araucanía.

- Salazar, G. (2009). Mercaderes, empresarios y capitalistas (Chile. Siglo XIX). Debate.

- SOFO (Sociedad de Fomento Agrícola de Temuco). (1943). Jubileo SOFO (1918–1943). Imprenta san Francisco.

- Tornero, R. (1872). Chile ilustrado. Guía descriptiva del territorio de Chile, de las capitales de provincia, i de los puertos principales. Librería i Ajencia del Mercurio.

- Torrejón, F., & Cisternas, M. (2002). Impacto ambiental temprano en la Araucanía deducido de crónicas españolas y estudios historiográficos. Bosque, 24(3), 45–55. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002003000300005

- Treutler, P. (1866). Andanzas de un alemán en Chile 1851–1863. Editorial del Pacífico.

- Verniory, G. (2001). Diez años en Araucanía (1889–1899). Ediciones Pehuén.